Abstract

Background and Objectives:

Aim of this randomly controlled clinical study was to evaluate the role of antibiotics to prevent postoperative complications after routine periodontal surgery and also to determine whether their administration improved the surgical outcome.

Materials and Methods:

Forty-five systemically healthy patients with moderate to severe chronic periodontitis requiring flap surgery were enrolled in the study. They were randomly allocated to Amoxicillin, Doxycycline, and control groups. Surgical procedures were carried out with complete asepsis as per the protocol. Postoperative assessment of patient variables like swelling, pain, temperature, infection, ulceration, necrosis, and trismus was performed at intervals of 24 h, 48 h, 1 week, and 3 months. Changes in clinical parameters such as gingival index, plaque index, probing pocket depth, and clinical attachment level were also recorded.

Results:

There was no incidence of postoperative infection in any of the patients. Patient variables were comparable in all the three groups. Though there was significant improvement in the periodontal parameters in all the groups, no statistically significant result was observed for any group over the others.

Conclusion:

Results of this study showed that when periodontal surgical procedures were performed following strict asepsis, the incidence of clinical infection was not significant among all the three groups, and also that antibiotic administration did not influence the outcome of surgery. Therefore, prophylactic antibiotics for patients who are otherwise healthy administered following routine periodontal surgery to prevent postoperative infection are unnecessary and have no demonstrable additional benefits.

Keywords: Antibiotic, asepsis, complications, periodontal surgery

INTRODUCTION

Periodontitis is a multifactorial disease occurring as a result of complex interrelationship between infectious agents and host factors. Environmental, acquired, and genetic risk factors modify the expression of disease and may therefore affect the onset or progression of periodontitis.[1] The hallmarks of periodontal disease are destruction of connective tissue and bone loss which, if left untreated, may eventually lead to tooth loss.

Moderate to severe cases of chronic periodontitis may warrant periodontal surgical procedures.[2] Of the various factors that affect the outcome of periodontal surgical procedures, the most important aspect is prevention of infection during and following surgery. Sources of infection during surgery in oral cavity include: instruments, hands of surgeon and assistant, air of the operatory, and patient's perioral skin, nostrils, and saliva.[3]

As postoperative infection can have a significant effect on the surgical outcome, preventive measures like strict aseptic protocol, anti-infective measures like proper sterilization, disinfection, barrier techniques, and other measures should be taken. If such measures are taken, there is a very low rate of postoperative infection following periodontal surgery,[4] thereby obviating the need for using antibiotics as a prophylactic measure. However, in actual clinical practice, it has been observed that different types of antimicrobials are routinely prescribed following periodontal surgery.

Few studies support the concept of rapid healing and less discomfort when antibiotics are used.[5,6] On the other hand, many well-conducted studies have not supported the routine use of antibiotics after periodontal surgery and concluded that antibiotics should be used only when there is a medical indication or when the infection has already set in.[2,7,8,9,10,11]

In India, dentists have been known to prescribe antibiotics more than any other medical personnel, which is based totally on empiricism without any protocol or rationale.[12,13] Indiscriminate use of antibiotics carry the risk of development of gastrointestinal tract problem, colonization of resistant or fungal strains, cross-reaction with other drugs, allergies, and increased cost of treatment.[14]

Presently, guidelines for the selection and administration of antibiotics as prophylaxis following surgery are lacking. Hence, this particular study was undertaken to assess the incidence of clinical infection and role of antibiotics in preventing infection in patients undergoing routine periodontal surgery and its influence on the surgical outcome.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

In this randomly controlled clinical trial, 45 patients with moderate to severe chronic periodontitis requiring flap surgery were recruited from the Department of Periodontics. The study protocol was approved by the ethical committee.

Inclusion criteria

Patients aged between 25 and 55 years with moderate to severe chronic periodontitis

Systemically healthy patients fit for periodontal surgery

Patients with good oral hygiene maintenance.

Exclusion criteria

Patients allergic to Amoxicillin and Doxycycline

Pregnant patients

Smokers

Previous periodontal surgery done in the same area

Antibiotic therapy taken 3 months prior to surgery.

Forty-five patients fulfilling the above-mentioned criteria were allocated into three groups (Amoxicillin, Doxycycline, and control groups). Informed consent was obtained from the patients. Three weeks following phase I therapy, a periodontal evaluation was performed to confirm the suitability of sites for periodontal flap surgery.

The following parameters were measured at baseline and 3 months following surgery:

Plaque index (Silness and Loe)

Gingival index (Loe and Silness)

Probing pocket depth (PPD)

Clinical attachment level (CAL)

Gingival recession (GR)

Tooth mobility.

Patients from both test and control groups with persistent probing depths equal to or more than 5 mm in at least three teeth in a sextant were subjected to periodontal flap surgery in a specially prepared surgical room setup. Antibiotics were started 1 day prior to surgery and continued for 5 days thereafter, wherein Group A patients were administered Amoxicillin 500 mg three times a day and Group B patients were administered Doxycycline 200 mg as a loading dose and 100 mg thereafter. Group C patients were controls without any antibiotic prescription. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (Ibuprofen 400 mg + Paracetamol 333 mg) thrice daily for a minimum of 3 days was prescribed for all the three groups after surgery.

Surgical aseptic protocol and infection control measures

All the periodontal surgical procedures were carried out in a fumigated enclosed surgical room with restricted entry and proper drainage and water supply system in place. Anybody with any source of infection was not allowed to enter the room. All personnel assigned in the operating room practiced standard presurgical procedures which included autoclaved surgical gowns, head caps, masks, and separate in-house footwear.

Dental operatory tools, including dental chair, were cleaned daily with a disinfectant (Bacillol 25). Exposed areas were covered with aluminum foils. Disposable glasses and autoclaved disposable suction tips were used along with distilled water as water source.

High-volume evacuation suctions were used for decreasing the aerosol production. Spittoon and tumbler water lines were flushed for at least 5 min before and after the surgical procedure. All instruments to be used were precleaned, segregated, and packed in autoclavable sealed pouches which had chemical spore testing test strips attached to them and were then autoclaved [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Armamentarium

Operator and assistant performed a presurgical scrub with a germicidal soap using vigorous friction before the surgical procedure. Patient preparation was done with povidone iodine presurgical facial scrub. Pre-procedural mouthrinse with 10 ml of 0.2% chlorhexidine was done. Proper barrier methods were used.

Surgical procedure

Surgical procedure was performed under local anesthesia with 2% lignocaine containing adrenaline (1:200,000). Buccal and lingual (palatal) surgical incisions were made and mucoperiosteal flaps were elevated [Figures 2 and 3].

Figure 2.

Preoperative probing depth (Group B)

Figure 3.

Incision placed

Complete debridement of the surgical site and scaling and root planing were done with ultrasonic device and hand curettes [Figure 4]. Flaps were approximated with 3-0 silk sutures [Figure 5]. Periodontal dressing was placed and postoperative instructions were given [Figure 6]. Application of cold pack was not advised for patients belonging to any of the three groups post-surgically.

Figure 4.

Flap reflection and debridement

Figure 5.

Sutures placed

Figure 6.

Periodontal dressing placed

Postoperative care and evaluation

Test and control group patients were instructed to continue the medication and were asked to abstain from brushing on the surgical site for at least 2 weeks. Use of chlorhexidine gluconate (0.2%) was advised for 1 min twice daily immediately 1 day after the surgery for 1 month. Patients were asked to record the incidence of pain, swelling, and increase in temperature, or any other associated adverse effect after surgery which was graded as mild, moderate, or severe in nature. These were recorded in a tabular chart at two intervals in a day for up to 48 h after surgery.

Periodontal dressing and sutures were removed 1 week postoperatively and the operated area was evaluated for healing, infection, and any signs of ulceration and necrosis which were tabulated separately in the chart provided [Figure 7].

Figure 7.

1 Week postoperative photograph

In order to avoid bias, all the post-surgical measurements were done by previously calibrated periodontists, who were blinded to the group to which the patient belonged. After the third month, all post-surgical parameters were recorded and evaluated.

Statistical analysis

Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to find the significance of the study parameters between three or more groups of patients. Chi-square/Fisher's exact test was used to find the significance of study parameters on categorical scale between two or more groups.

Statistical software, namely, SAS 9.2, SPSS 15.0, Stata 10.1, MedCalc 9.0.1, Systat 12.0, and R environment ver. 2.11.1 were used for the analysis of the data, and Microsoft Word and Excel were used to generate graphs, tables, etc.

RESULTS

All the patients returned regularly for the maintenance program, without any dropouts. None of the patients belonging to Groups A and B developed any allergy or unfavorable response to the drug, requiring discontinuation.

Age and gender of patients

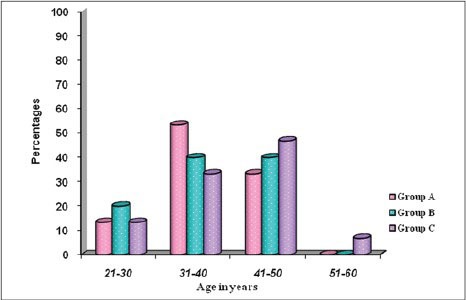

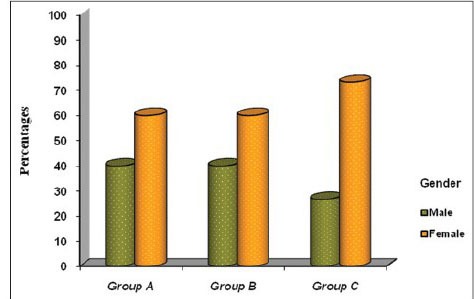

The age of the patients ranged between 21 and 60 years, with a mean age of 38.27 years in Group A, 37.27 years in Group B, and 39.93 years in Group C, thereby demonstrating the age match between the Groups. A total of 16 male patients and 29 female patients participated in the study [Graphs 1 and 2].

Graph 1.

Comparison of age distribution between the patients

Graph 2.

Comparison of gender distribution between the patients

Periodontal variables

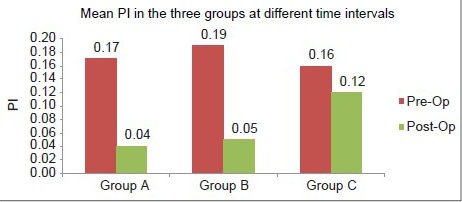

Plaque index

The plaque scores in all the groups were consistently maintained between 0.12 and 0.17 throughout the study. There was no statistically significant difference in the plaque scores between the groups [Graph 3].

Graph 3.

Comparison of mean plaque index between the three groups

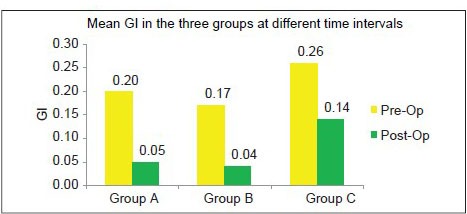

Gingival index

The mean gingival index in all the groups ranged from 0.05 to 0.26 at the end of the study period. Also, no statistically significant intergroup difference was observed [Graph 4].

Graph 4.

Comparison of mean gingival index between the three groups

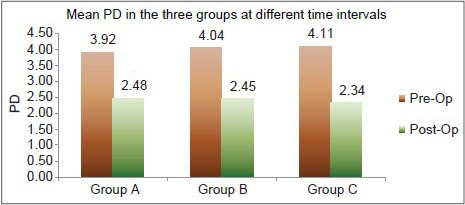

Probing pocket depth

The mean PPD in the Amoxicillin group was 3.92 ± 0.58 mm preoperatively, which reduced to 2.48 ± 0.25 mm postoperatively [Graph 5, Figures 8 and 9], whereas in Doxycycline group, the probing depth reduced from 4.04 ± 0.47 mm preoperatively to 2.45 ± 0.28 mm postoperatively [Graph 5, Figures 10 and 11]. In the control group, the probing depth was 4.11 ± 0.51 mm preoperatively, which reduced to 2.34 ± 0.69 mm postoperatively [Graph 5, Figures 12 and 13]. The reduction in probing depth in all the three groups was statistically highly significant. However, no statistically significant difference in the probing depth reduction could be seen when the results were compared among the three groups.

Graph 5.

Mean probing depths between the three groups

Figure 8.

Preoperative photograph (Group A)

Figure 9.

3 months postoperative photograph (Group A)

Figure 10.

Preoperative photograph (Group B)

Figure 11.

3 months postoperative photograph (Group B)

Figure 12.

Preoperative photograph (Group C)

Figure 13.

3 Months postoperative photograph (Group C)

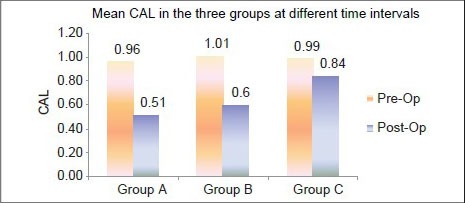

Clinical attachment level

The mean CAL in group A was 0.96 ± 0.18 mm preoperatively, which reduced to 0.51 ± 0.46 mm postoperatively [Graph 6], whereas in Group B, these readings were 1.01 ± 0.19 mm preoperatively and 0.60 ± 0.44 mm postoperatively [Graph 6].

Graph 6.

Mean clinical attachment level between the three groups

In the control group, the mean CAL reduced from 0.99 ± 0.20 mm preoperatively to 0.84 ± 0.15 mm postoperatively [Graph 6]. All these reductions within the groups were statistically significant, but no difference was seen when the results were compared among the three groups.

Patient variables

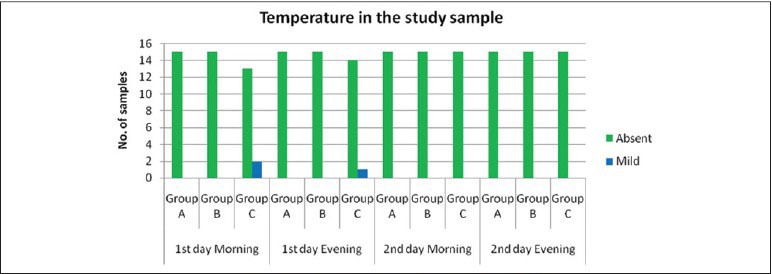

Temperature

There was no statistically significant difference among the different groups [Graph 7].

Graph 7.

Comparison of incidence of temperature between the three groups

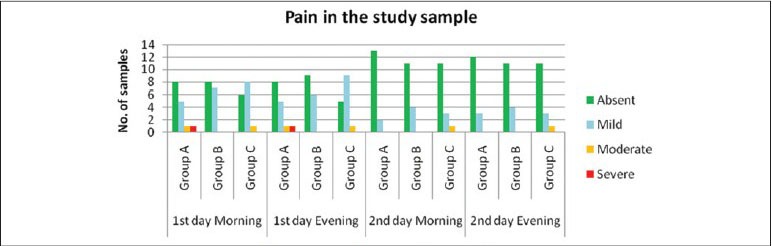

Pain

There was no statistically significant difference in the pain perception among the three groups, 24 h following surgery. Post-surgical evaluation done after 60 h showed that two patients in Group A and two in Group C had mild pain [Graph 8].

Graph 8.

Comparison of incidence of pain between the three groups

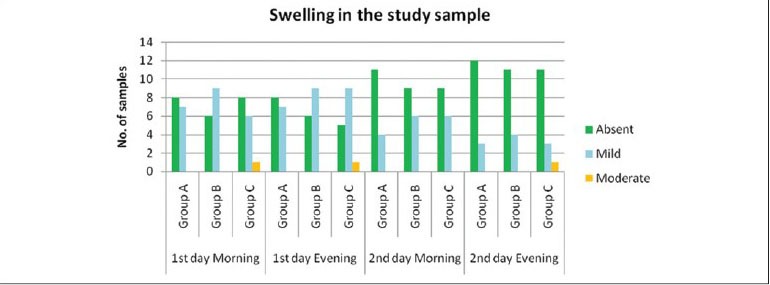

Postoperative swelling

No statistically significant association was observed among the groups at any of the time intervals [Graph 9].

Graph 9.

Comparison of incidence of swelling between the three groups

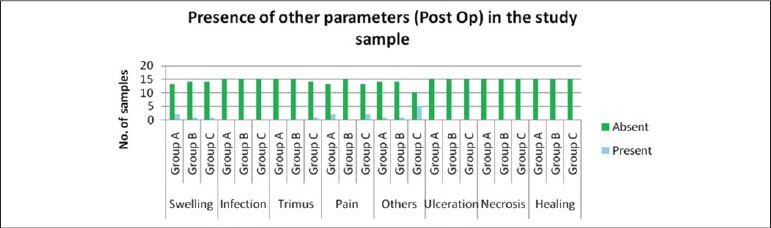

Other parameters

None of the patients in any group showed signs of postoperative infection, and overall healing was satisfactory [Graph 10].

Graph 10.

Comparison of incidence of other parameters between the three group

Other findings

Patients were directed to report any other events such as lassitude, body ache, gastric upset, diarrhea, and headache following surgery.

Overall, there was no statistical significance between the groups in any of the parameters listed above.

DISCUSSION

Oral cavity, which harbors billions of microorganisms as their natural habitat, is also influenced by a multitude of external factors, leading to its susceptibility for infection. Though in actual practice, only a minority of surgical procedures performed in the oral cavity result in any significant post-surgical infection, they could result in needless complications, discomfort to the patient, delay in healing, and can influence the final outcome as well. Hence, majority of the surgeons throughout the world believe in the dictum “to err on the side of safety” and routinely prescribe antimicrobials as prophylaxis to prevent post-surgical infections. Periodontists are no exception to this.

However, there are neither guidelines nor incontrovertible evidence to support this practice; also, there is no uniform system prevailing in different parts of the world to guide periodontists regarding the type of drug, its dosage, duration, etc. Literature support for routine antibiotic prescription is lacking and few studies carried out to address this matter have provided different conclusions. Hence, as of now, prescribing antimicrobial therapy as prophylaxis to prevent infection during routine periodontal surgery can only be called as empirical and is not based on solid evidence.

This study, therefore, envisaged to evaluate the effects of antimicrobial prophylaxis on all the parameters of healing following periodontal surgery as compared to no drug therapy, besides attempting to find out the actual incidence of post-surgical infections. The patients recruited were all systemically healthy, belonged to a comparable age range, and were compliant. Oral hygiene maintenance was periodically reinforced and assessed by clinical parameters from baseline to 1 month prior to the surgery. Patients who did not maintain adequate oral hygiene and who were noncompliant were not included in the study as literature reviews have shown that noncompliant subjects had the highest risk of recurrent periodontitis, even if they had completed the treatment plan. The surgical technique and the type of periodontal defects were also standardized.

Results of the study clearly showed that properly performed periodontal surgery does not result in post-surgical infection or any complications. This was amply substantiated by lack of any undesirable outcome such as persistent excessive pain, severe swelling, abscess formation, ulceration, and necrosis in any of the patients. None of the patients had any noticeable systemic effect following surgery. These results correspond with the reported results of the studies done earlier,[2,7,8,9,10] but literature review has supported the potential beneficial effects of prophylactic antibiotics in patients with systemic involvement.

Amoxicillin and Doxycycline were chosen for the two experimental groups, mainly because most of the dental practitioners prefer Amoxicillin whereas majority of the periodontists prefer Doxycycline for its effect against periodontal pathogens due to convenience of its usage, which thereby improves patient compliance. Metronidazole was not considered, as patient compliance has been found to be poor due to its side effects.[15]

Different patient variables (ulceration or necrosis, signs of delayed healing, adverse systemic effects such as fever, malaise, lassitude, etc.) indicated that there was no difference between any of the groups. These findings are in agreement with those of earlier studies.[2,13,16] The role of antimicrobials in improving periodontal variables following surgery is controversial.[17,18]

Studies in which randomized controlled trials (RCTs) were conducted reported that selective antimicrobial agents when used as adjunctive to periodontal surgical procedures improved the periodontal parameters,[19,20,21] whereas meta-analysis studies reported that adjunctively used systemic antimicrobials did not show statistically significant results.[18,22,23,24] However, in this study, there was no difference in the periodontal parameters such as plaque index, gingival inflammation, pocket depth reduction, or CAL among the different groups.

Hence, this study has clearly demonstrated that routine periodontal surgery when properly performed does not result in post-surgical infection and produces beneficial outcome regardless of whether prophylactic antimicrobials have been prescribed or not.

In this era where antimicrobials are being prescribed without any basis, it often leads to abuse and misuse of them. The development of various resistant strains of microorganisms has frequently resulted in serious unmanageable infections.[25] Hence, the outcome of this study is very significant, particularly in a country like India where there is no antibiotic policy prescribed by the regulatory bodies.

But it should be understood that this study was carried out in a hospital setting with a strong surgical protocol. Whether the same result can be obtained in an ordinary clinical setting, especially in a dental clinic setup, is questionable. Further studies are required to be done in less than ideal settings before it can be unequivocally recommended to discontinue the use of prophylactic antimicrobial drug following periodontal surgical procedure.

CONCLUSION

The results of this study revealed that periodontal surgery done under strict surgical protocol did not result in postoperative infection, irrespective of whether antibiotics were prescribed or not. Hence, it is concluded that prophylactic medication of patients with antibiotics who are otherwise healthy following routinely properly performed periodontal surgery is unnecessary and has no demonstrable additional benefits.

Further studies need to be conducted in different clinical settings before recommending changes in the antibiotic policy for surgical procedures.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Page RC, Offenbacher S, Schroeder HE, Seymour GJ, Kornman KS. Advances in pathogenesis of periodontitis: Summary of developments, clinical implications and future directions. Periodontal. 1997;14:216–48. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.1997.tb00199.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Powell CA, Mealy BL, Deas DE, McDonnel HT, Moritz AJ. Post surgical infections: Prevalence associated with various periodontal surgical procedures. J Periodontol. 2005;76:329–333. doi: 10.1902/jop.2005.76.3.329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Van Steenberge D, Yoshida K, Papaioannou W, Bollen CM, Reybrouck G, Quirynen M, et al. Complete nose coverage to prevent airborne contamination via nostrils is unnecessary. Clin Oral Implant Res. 1997;8:512–6. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0501.1997.080610.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Abu-Ta’a M, Quirynen M, Teughels W, Steenberghe D. Asepsis during periodontal surgery involving oral implants and the usefulness of perioperative antibiotics: A prospective, randomized, controlled clinical trial. J Clin Periodontol. 2008;35:58–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2007.01162.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aurido AA. The efficacy of antibiotics after periodontal surgery: A controlled study with Lincomycin and Placebo in 68 patients. J Periodontol. 1969;40:150–4. doi: 10.1902/jop.1969.40.3.150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kidd EA, Wade AB. Penicillin control of swelling and pain after periodontal osseous surgery. J Clin Periodontol. 1974;1:52–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1974.tb01239.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Scopp IW, Fletcher PD, Wynman BS, Epstein SR, Fine A. Tetracycline: Double blind clinical study to evaluate the effectiveness in periodontal surgery. J Periodontol. 1977;48:484–6. doi: 10.1902/jop.1977.48.8.484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pack PD, Haber J. The incidence of clinical infection after periodontal surgery. J Periodontol. 1983;54:441–3. doi: 10.1902/jop.1983.54.7.441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chechi L, Trombelli L, Nonato M. Postoperative infections and tetracycline prophylaxis in periodontal surgery: A retrospective study. Quintessence Int. 1992;23:191–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mahmood MM, Dolby AE. The value of systemically administered Metronidazole in the modified Widman flap procedure. J Periodontol. 1987;58:147–51. doi: 10.1902/jop.1987.58.3.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tseng CC, Huang CC, Tseng WH. Incidence of clinical infection after periodontal surgery: A prospective study. J Formos Med Assoc. 1993;92:152–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gutienez JL, Bagan JV, Bascones A, Llamas R, Llena J, Morales A, et al. Consensus document on the use of antibiotic prophylaxis in dental surgery and procedures. Med Oral Pathol Oral Cir Bucal. 2006;11:E188–205. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Arab HR, Sargolazaie N, Moientaghavi A, Ghanbari H, Abdollahi Z. Antibiotics to prevent complications following periodontal surgery. Intl J Pharmacol. 2006;2:205–8. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lawler B, Sambrook PJ, Goss AN. Antibiotic prophylaxis for dentoalveolar surgery: Is it indicated? Aust Dent J. 2005;50(Suppl 2):554–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1834-7819.2005.tb00387.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rossi S, editor. Adelaide: Australian Medicines Handbook; 2006. Australian Medicines Handbook 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pendrill K, Reddy J. The use of prophylactic penicillin in periodontal surgery. 1980;51:44–8. doi: 10.1902/jop.1980.51.1.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ciancio SG. Systemic medications. Clinical significance in periodontics. J Periodontol. 2002;29:17–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Haffajee AD, Socransky SS, Gunsolley JC. Systematic anti-infective periodontal therapy. A systematic review. Ann Periodontol. 2003;8:115–81. doi: 10.1902/annals.2003.8.1.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lindhe J, Lijenberg B. Treatment of localized juvenile periodontitis. J Clin Periodontol. 1984;11:399–410. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1984.tb01338.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kleinfelder JW, Mueller RF, Lange DE. Fluroquinalones in the treatment of Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans associated periodontitis. J Periodontol. 2000;71:202–8. doi: 10.1902/jop.2000.71.2.202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dastoor SF, Travan S, Neiva RF, Rayburn LA, Giannobile WV, Wang HL, et al. Effects of adjunctive systemic azithromycin with periodontal surgery in the treatment of chronic periodontitis in smokers: A pilot study. J Periodontol. 2007;78:1887–96. doi: 10.1902/jop.2007.070072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kunihira DM, Caine FA, Palcanis KG, Best AM, Ranney RR. A clinical trial of phenoxymethyl penicillin for adjunctive treatment of juvenile periodontitis. J Periodontol. 1985;56:352–8. doi: 10.1902/jop.1985.56.6.352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Haffajee AD, Dilbart S, Kent RL, Socransky SS. Clinical and microbiological changes associated with the use of 4 adjunctive systemically administered agents in the treatment of periodontal infections. J Clin Periodontol. 1995;22:618–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1995.tb00815.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Palmer RM, Watts TL, Wilson RF. A double- blind trial of tetracycline in the management of early onset periodontitis. J Clin Periodontol. 1996;23:670–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1996.tb00592.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tacconelli E, De Angelis G, Cataldo MA, Pozzi E, Cauda R. Does antibiotic exposure increase the risk of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) isolation? A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2008;61:26–38. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkm416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]