Abstract

Dental fear is a barrier to receiving dental care, particularly for those patients who also suffer from mental illnesses. The current study examined United States dental professionals’ perceptions of dental fear experienced by patients with mental illness, and frequency of sedation of patients with and without mental illness. Dentists and dental staff members (n = 187) completed a survey about their experiences in treating patients with mental illness. More participants agreed (79.8%) than disagreed (20.2%) that patients with mental illness have more anxiety regarding dental treatment (p < .001) than dental patients without mental illness. Further, significantly more participants reported mentally ill patients’ anxiety is “possibly” or “definitely” a barrier to both receiving (96.8%; p < .001) and providing (76.9%; p < .01) dental treatment. Despite reporting more fear in these patients, there were no significant differences in frequency of sedation procedures between those with and without mental illness, regardless of type of sedation (p’s > .05). This lack of difference in sedation for mentally ill patients suggests hesitancy on the part of dental providers to sedate patients with mental illness and highlights a lack of clinical guidelines for this population in the US. Suggestions are given for the assessment and clinical management of patients with mental illness.

Introduction

Individuals with mental illness typically have worse oral health than individuals without mental illness. Mental illnesses such as mood, anxiety, and psychotic disorders have been linked to increased caries and periodontal disease.1 These patterns remain consistent whether these individuals reside in inpatient2 or community settings.3 Lower income, lack of knowledge of dental needs, and xerogenic side effects of psychotropic medications have all been shown to impact oral health in this population.4 It is critical, then, that individuals with mental illness receive regular dental care in order to lessen the impact of mental illness on their oral health.

Among the many factors that impede access to adequate dental care in this population,4 dental fear frequently is linked to poor oral health outcomes. High dental fear has been linked to lower scores on the SF-36 mental health scale5 and increased numbers of psychiatric diagnoses.6 Pohjola and colleagues7 found that individuals with depressive disorders and generalized anxiety disorder were significantly more likely to have dental fear than those without these psychiatric disorders even when differences in socioeconomic characteristics were taken into consideration.

Treating dentally anxious patients is often linked to increased stress in dental providers8 and combining patients’ fear with other mental health issues can further complicate treatment. Dentists who perceived that psychological problems led to increased dental fear in their patients were more likely to report increased stress in their professional lives.9 Further, dentists express frustration that mentally ill patients frequently miss appointments and do not follow through on treatment recommendations.10 Many dentists surveyed noted that they were not well equipped to identify or treat patients with mental illness, and tended to focus on physical aspects of patients’ dental problems rather than addressing any aspects of patients’ psychological problems.11

The goal of this study was to examine United States (US) dental professionals’ perceptions of dental fear experienced by patients with mental illness, and their patterns of providing different types of sedation to patients with and without mental illness.

Methods

Sampling and Participants

Participants were dentists and dental staff (dental hygienists, dental assistants, and front office/billing personnel) attending the 2011 Pacific Northwest Dental Conference in Seattle, Washington. Study personnel staffed a booth in the conference exhibit hall. Signs at the booth informed individuals of the opportunity to participate in a survey about working with mentally ill patients, and study personnel approached individuals passing by the booth to solicit their participation. All participants currently employed as a dentist or dental staff member working at least in part with adult patients (i.e. not paediatrics) were eligible to take part in the study, regardless of whether they felt their practice regularly treated individuals with mental illness. Upon agreeing to participate, participants were given a clipboard, questionnaire packet and pen, and shown to a nearby seating area where they could complete the survey. If members from the same dental office completed the survey, they were asked to complete the survey independently from one another to ensure individual responses.

Materials

The questionnaire contained 86 questions about dental personnel’s attitudes toward and experiences in working with adult patients with mental illness. For the purpose of this study, mental illness was defined as “any type of emotional difficulties including, but not limited to, mood disorders including depression and bipolar disorder, anxiety disorders, eating disorders, schizophrenia, and substance abuse”. Further, the introduction stated “these conditions may or may not be treated by medications and/or therapy, and may or may not cause limitations in a person’s ability to function”.

Participants were asked what percentage of patients in their dental practice they estimated are currently taking psychotropic medications, as well as what percentage of patients in their practices they estimated are known (e.g. via the patient’s health history) or suspected (e.g. through patients’ behavioural observations or comments) to have a mental illness but are not treated for this mental illness. Participants were then asked how much they agreed with a series of statements about treating patients with mental illness compared to patients without mental illness (e.g. “Patients with mental illness are more anxious about having dental treatment.”). Possible item responses ranged from “strongly disagree” (1) to “strongly agree” (4).

Participants were asked about barriers they perceived to mentally ill patients receiving adequate dental care (e.g. “dental anxiety or fear”), and barriers they as dental professionals perceived toward treating mentally ill patients (e.g. “patients’ fear or anxiety during treatment”). Participants identified each statement as not a barrier (1), possibly a barrier (2), or definitely a barrier (3). Frequency of sedation techniques used was also assessed for patients with and without mental illness. Participants were asked, “If sedation is needed, how often do you provide it to adult patients in your practice who are/not known or suspected to be mentally ill?” Sedation types included sedation of any type, nitrous oxide (relative analgesia) only, oral sedation only, nitrous oxide plus oral sedation, and intravenous (IV) sedation. Possible item responses ranged from “never” (1) to “very often” (5). Demographic information was collected regarding participants’ age, gender, race, ethnicity, role in the dental office (dentist, hygienist, assistant, billing staff, front office staff, and other), time employed in the dental field, primary type of practice (general/family, paediatric, other specialty), location of practice (rural, urban, suburban, other), and clinic type (private solo, private with one other partner, private with 3 or more providers, community clinic, or other).

Statistical Analyses

Descriptive analyses were done to examine the demographic characteristics of the sample. Nonparametric tests examined differences in proportions of responses on 3- and 4-point Likert scales. One-way analyses of variance (ANOVA) results showed no significant differences between dental professional type (dentist, hygienist, assistant, or front office/billing) on any of the variables of interest. The results for all four professional groups, therefore, were combined for analysis.

Ethics

The Institutional Review Board at the University of Washington approved the study protocol. Participants were informed that their participation was voluntary and their responses anonymous. The first 80 participants received a $5 USD gift card.

Results

Demographic characteristics

Two hundred individuals participated. Nine questionnaire packets were returned as incomplete and were not included in the final analysis. As the population of interest was professionals working primarily with adult patients, data from the 4 participants self-identified as working in paediatric practice were removed from analysis once it was determined that results did not differ significantly after omission of their data. This resulted in a final sample size of 187 (93.5%).

Table 1 presents the demographic characteristics of the sample. The mean age of the sample was 42.2 years (s.d. = 13.1; range 20–88 years) and 77.5% percent of the sample was female. Most (70.6%) were White/Caucasian, and 96.2% considered themselves to not be Hispanic or Latino/a.

Table 1.

Demographic information on sample of US dentists and dental staff members responding to a survey of care of mentally ill patients in 2011.

| Demographic Variable | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Gender of Dental Professional | |

| Female | 145 (77.5) |

| Male | 42 (22.5) |

| Race of Dental Professional | |

| Hispanic or Latino/a | 7 (3.8) |

| Not Hispanic or Latino/a | 179 (96.2) |

| Ethnicity of Dental Professional | |

| White/Caucasian | 132 (70.6) |

| Asian | 25 (13.4) |

| More Than One Race Reported | 12 (6.4) |

| Don’t know/Not Reported | 12 (6.4) |

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 5 (2.7) |

| Native Hawaiian/Other Pacific Islander | 1 (0.5) |

| Black/African-American | 0 (0) |

| Dental Professional Role | |

| Dentist | 71 (38.0) |

| Dental Hygienist | 65 (34.8) |

| Dental Assistant | 39 (20.9) |

| Billing/Front Office/Other | 12 (6.3) |

| Practice Location | |

| Suburban | 75 (41.9) |

| Urban | 70 (39.1) |

| Rural | 34 (19.0) |

| Type of Practice | |

| General/Family Practice | 160 (85.6) |

| Other Specialty Practice | 27 (14.4) |

| Clinic type | |

| Private - Solo | 105 (58.0) |

| Private – One Other Partner | 30 (16.6) |

| Private – 3 or more Providers | 19 (10.5) |

| Community (non profit) Clinic | 15 (8.3) |

| Other | 12 (6.6) |

Thirty-eight percent of respondents were dentists, 34.8% dental hygienists, 20.9% dental assistants, and 6.3% were front office, billing, or other staff. The average length of time in the dental field was 16.4 years (s.d. = 13.1) and ranged from 0 to 67 years. Over forty percent (41.9%) described their practice as suburban, and 85.6% of practices were described as general/family practice.

Prevalence of mental illness in dental practice

Participants estimated that on average, 31.4% (s.d. = 21.8; range 0–99%) of patients in their practice are taking psychotropic medications currently. Participants also estimated that 14.1% (s.d. = 14.6; range 0–9%) of patients were either known or suspected to have some form of untreated mental illness. Dentists provided significantly lower estimates of patients taking psychotropic medications (24.0%) than did hygienists (35.8%; p < .01). There were no other differences by dental professional type in the estimates of patients taking psychotropic medications or having untreated mental illness.

Dental fear in patients with mental illness

Table 2 shows the percentage of dental professionals who responded “agree” or “strongly agree” to the question, “patients with mental illness are more anxious about having dental treatment”. In addition, Table 2 shows the percentage of participants who indicated that the dental fear of patients with mental illness is “possibly” or “definitely” a barrier to patients seeking dental treatment or dental professionals providing treatment.

Table 2.

Percentages of US dental professionals reporting anxiety of patients with mental illness (MI) as interfering with or acting as a barrier to seeking or providing dental care.

| Item | % |

|---|---|

| Patients with MI are more anxious about having treatment (agree/strongly agree vs. disagree/strongly disagree) | 79.8** |

| Patients’ fear/anxiety as a barrier to providing treatment (possibly/definitely a barrier vs. not a barrier) | 76.9* |

| Patients’ fear/anxiety as a barrier to seeking treatment (possibly/definitely a barrier vs. not a barrier) | 96.8** |

p < .01;

p < .001

Analyses show that significantly more dental professionals agreed (79.8%) than disagreed (20.2%) that patients with mental illness have more anxiety about receiving dental treatment (p < .001) compared to dental patients without mental illness. Further, results showed that significantly more participants reported patients’ anxiety is “possibly” or “definitely” a barrier to patients receiving dental treatment (96.8%; p < .001) or dental professionals providing dental treatment to patients with mental illness (76.9%; p < .01).

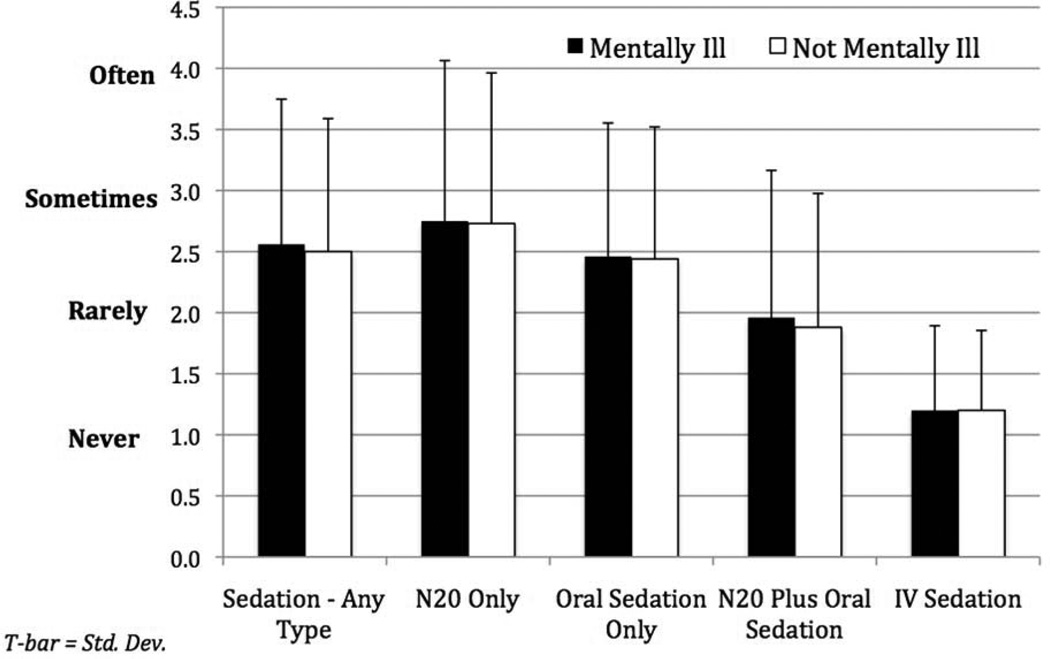

Use of sedation in patients with and without mental illness

Figure 1 illustrates the mean frequency of each type of sedation used between patients with and without mental illness. There were no significant differences between patients with and without mental illness for the use of different types of sedation (p’s > .05). For patients with mental illness, participants indicated that nitrous oxide alone is used significantly more than any other type of sedation (p’s < .05) in their practices. For patients without mental illness, participants reported that nitrous oxide alone is used in their practices significantly more than any other type of sedation (p’s < .01).

Figure 1.

Mean frequency of sedation type by presence or absence of patients’ mental illness in a sample of USA dental practices in 2011.

Discussion

When compared to US national averages, the dental professionals in our sample estimated treating nearly three times as many patients taking psychotropic medications (31% in this sample versus 11%)12 yet less than half as many patients with untreated mental illness (14% in this sample versus 29%).13 The dentists and dental staff in our sample consistently reported that their patients suffering from mental illness are more anxious about receiving dental treatment than their patients without mental illness, and that patients’ anxiety is a significant barrier both to patients seeking treatment and dental professionals providing treatment. These findings are consistent with prior research suggesting that dentists who feel they are not well trained in treating patients with special health care needs are less likely to provide treatment to such patients.14,15

When faced with a patient population that consistently presents with higher dental fear5–7 and more dental disease,1,4 it could be expected that dental professionals would be more likely to use sedation techniques to treat these individuals. Despite consistent reports that their mentally ill patients have more anxiety about dental treatment than patients without mental illness, dental providers in our sample reported no significant differences in the frequency of sedation used for these two patient groups, regardless of type of sedation.

Using sedative techniques with the same frequency in patients with mental illness despite higher perceived levels of dental fear suggests hesitancy on the part of dental providers to use sedation with mentally ill patients. This hesitancy may stem from a lack of experience or confidence in working with this population,11 or a misconception that use of certain medications may push mentally ill patients “over the edge”, exacerbating their psychiatric symptoms even in the absence of clear medical contraindications. Dentists have indicated a lack of confidence in identifying mental illness in their patients,11 and dental providers faced with unusual patient behaviour may avoid using pharmacological adjuncts in the absence of a formal psychiatric diagnosis for fear of “making the patient worse”.

Individuals with mental illness are considered by the Special Care Dentistry Association (SCDA) to require special treatment accommodations similar to those of other populations with special health care needs.16 Resources are being developed currently to help dental providers better understand and care for adults and children with mental illness.17 Yet, no formal guidelines exist for the use of sedative techniques with individuals with mental illness. Malamed18 strongly emphasizes the importance of assessing patients’ psychiatric conditions prior to using sedative techniques. In addition, Table 3 provides a summary of commonly prescribed psychotropic medications and their interactions with sedative and/or anesthetic drugs.

Table 3.

Common psychotropic medications and their interactions with sedative or aneasthetic drugs.

| Psychotropic Medication/Purpose |

Examples | Interacting Dental Drug18 | Interaction effects18 | Recommendations18 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Anticonvulsants Bipolar Disorder |

Carbamapezine Lamotrigine Valproic acid |

|

|

|

|

Benzodiazepines Anxiety |

Alprazolam Diazepam Midazolam |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

Mono-amine oxidase inhibitors Depression |

Phenelzine Tranylcypromine |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors Depression/anxiety |

Fluoxetine Paroxetine Sertraline Citalopram |

|

|

|

|

Serotonin- norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors Depression/anxiety |

Venlafaxine Mirtazapine Duloxetine |

|

|

|

|

Stimulants Attention disorders |

Methylphenidate |

|

|

|

To ensure good patient care, all dental patients seeking dental treatment under sedation should complete a carefully history of both their physical and psychological and/or psychiatric history, regardless of whether they are currently treated for a mental illness.18 By understanding a patients’ psychological/psychiatric history prior to administering sedative medications, dental providers may help anticipate secondary complications stemming from the patient’s mental illness.

As an example, a patient diagnosed with schizophrenia, paranoid type, may indicate that he is suspicious of the effects of the sedative medications to be used during the procedure. Assuring the patient that you will be in close contact with his physician and/or psychiatrist to ensure that all medications are safe and compatible with his existing medications may be critical in alleviating his concerns. Table 4 presents common psychiatric diagnoses seen in the dental office and considerations for each. As a note, the information presented in Table 4 is not meant to take the place of nor supersede a diagnosis from a trained psychologist, psychiatrist, or other mental health professional that has assessed the patient(s) in question.

Table 4.

Common mental health/psychiatric illnesses and dental considerations prior to sedation.

| Mental illness | Symptoms | Recommendations |

|---|---|---|

| Bipolar Disorder | Presence of manic and depressive episodes. Manic Episode – period of 1 week or more where mood is consistently elevated or irritable; may include decreased need for sleep; pressured speech; racing thoughts; increased activity; and distractibility (pp. 357–361).19 Depressive Episode – see Major Depressive Episode/Disorder |

|

| ||

| Generalized Anxiety Disorder | Presence of excessive worry and anxiety for a period of 6 months or more; patient finds it difficult to control the worry; accompanied by physical symptoms such as restlessness, fatigue, and disturbed sleep (pp. 472–476).19 |

|

| ||

| Major Depressive Episode | Period of 2 weeks or more where mood is depressed; interest in all or nearly all usual pleasurable activities is lost; patient reports feeling sad or “down in the dumps;” feelings of hopelessness (pp. 349–356).19 |

|

| ||

| Panic Disorder | Presence of recurrent panic attacks, combined with worry or fear of having additional panic attacks (pp. 433–440).19 Panic Attack – period of intense fear in absence of real danger including cognitive (fear of losing control) and/or physical (shortness of breath, dizziness, trembling, etc.) symptoms (pp. 430–432).19 |

|

| ||

| Schizophrenia or Other Psychotic Disorders |

Delusions – mistaken but unwavering beliefs that usually involve a misinterpretation of perceptions or experiences (pp. 297–302).19 Hallucinations – sensory experiences (hearing voices, seeing visions, etc.) that do not appear grounded in reality (pp. 297–302).19 |

|

| ||

| Social Anxiety Disorder/Social Phobia | Fear of social or performance situations in which the patient may be embarrassed (pp. 450–456).19 |

|

| ||

| ||

The current study included currently practicing dentists and dental staff members primarily from Washington State who were attending a professional dental conference. A broader survey of dental providers across the US could provide more generalizable results. However, dental professionals from across different types of practices (private and community clinics) and in different professional roles participated, providing a picture of the different types of dental providers mentally ill individuals may encounter when accessing dental care. Further, providers were eligible to participate regardless of how many mentally ill patients they regularly treated, providing a range of responses based on actual experiences versus perceived challenges with this patient population.

Individuals with mental illness are at increased risk for poor oral health outcomes, and fear of dental treatment often accompanies these other psychiatric diagnoses, making treatment under sedation a viable option. The current survey results, however, suggest that many US dentists may be hesitant to provide sedation to patients with mental illness. Standardized guidelines for the use of sedative techniques in this population are a critical first step in assuring that this underserved population has access to necessary dental treatment.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Washington State Dental Association for allowing this study to be conducted at the 2011 Pacific Northwest Dental Conference, and the study participants for their time and assistance. This study was funded by the University of Washington School of Dentistry Alumni and NIH/NIDCR Grant 5K23DE019202-03.

Contributor Information

Lisa J. Heaton, Oral Health Sciences, Box 357475, University of Washington School of Dentistry, Seattle WA 98195.

Halee A. Hyatt, Box 357475, University of Washington School of Dentistry, Seattle WA 98195.

Kimberly Hanson Huggins, Affiliate Instructor, Oral Medicine and Oral Health Sciences, Box 356370, University of Washington School of Dentistry, Seattle WA 98195.

Peter Milgrom, Department of Sedation and Special Care, King’s College Dental Institute, London, Professor, Oral Health Sciences, Box 357475, University of Washington, Seattle WA 98195.

References

- 1.Kisely S, Quek LH, Pais J, Lalloo R, Johnson NW, Lawrence D. Advanced dental disease in people with severe mental illness: systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry. 2011;199:187–193. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.110.081695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ponizovsky AM, Zusman SP, Dekel D, Masarwa AE, Ramon T, Natapov L, Yoffe R, Weizman A, Grinshpoon A. Effect of implementing dental services in Israeli psychiatric hospitals on the oral and dental health of inpatients. Psychiatr Serv. 2009;60(6):799–803. doi: 10.1176/ps.2009.60.6.799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arnaiz A, Zumárraga M, Díez-Altuna I, Uriarte JJ, Moro J, Pérez-Ansorena MA. Oral health and the symptoms of schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 2011;188(1):24–28. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2010.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Matevosyan NR. Oral health of adults with serious mental illnesses: a review. Community Ment Health J. 2010;46(6):553–562. doi: 10.1007/s10597-009-9280-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hägglin C, Hakeberg M, Ahlqwist M, Sullivan M, Berggren U. Factors associated with dental anxiety and attendance in middle-aged and elderly women. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2000;28(6):451–460. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0528.2000.028006451.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kaakko T, Coldwell SE, Getz T, Milgrom P, Roy-Byrne PP, Ramsay DS. Psychiatric diagnoses among self-referred dental injection phobics. J Anxiety Disord. 2000;14(3):299–312. doi: 10.1016/s0887-6185(00)00024-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pohjola V, Mattila AK, Joukamaa M, Lahti S. Anxiety and depressive disorders and dental fear among adults in Finland. Eur J Oral Sci. 2011;119(1):55–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.2010.00795.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hill KB, Hainsworth JM, Burke FJ, Fairbrother KJ. Evaluation of dentists' perceived needs regarding treatment of the anxious patient. Br Dent J. 2008;204(8):E13. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.2008.318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moore R, Brødsgaard I. Dentists' perceived stress and its relation to perceptions about anxious patients. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2001;29(1):73–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wieland B, Lau G, Seifert D, Siskind D. A partnership evaluation: public mental health and dental services. Australas Psychiatry. 2010;18(6):506–511. doi: 10.3109/10398562.2010.498512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lloyd-Williams F, Dowrick C, Hillon D, Humphris G, Moulding G, Ireland R. A preliminary communication on whether general dental practitioners have a role in identifying dental patients with mental health problems. Br Dent J. 2001;191(11):625–629. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4801252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Paulose-Ram R, Safran MA, Jonas BS, Gu Q, Orwig D. Trends in psychotropic medication use among U.S. adults. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2007;16(5):560–570. doi: 10.1002/pds.1367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bijl RV, de Graaf R, Hiripi E, Kessler RC, Kohn R, Offord DR, Ustun TB, Vicente B, Vollebergh WA, Walters EE, Wittchen HU. The prevalence of treated and untreated mental disorders in five countries. Health Aff (Millwood) 2003;22(3):122–133. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.22.3.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dao LP, Zwetchkenbaum S, Inglehart MR. General dentists and special needs patients: does dental education matter? J Dent Educ. 2005;69(10):1107–1115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vainio L, Krause M, Inglehart MR. Patients with special needs: dental students' educational experiences, attitudes, and behavior. J Dent Educ. 2011;75(1):13–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Special Care Dentistry Association. SCDA Definitions, Policies and Guidelines. [September 5, 2011]; Accessed at http://www.scdaonline.org/displaycommon.cfm?an=1&subarticlenbr=148 on.

- 17.University of Washington. Special Needs Fact Sheets for Providers and Caregivers. [September 5, 2011]; Accessed at http://www.dental.washington.edu/departments/omed/decod/special_needs_facts.php on.

- 18.Malamed SF. Sedation: A guide to patient management. St. Louis: Mosby Elsevier; 2010. pp. 37–44. [Google Scholar]

- 19.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Fourth Edition, Text Revision. Arlington: American Psychiatric Association; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Friedlander AH, Friedlander IK, Marder SR. Bipolar I disorder: psychopathology, medical management and dental implications. J Am Dent Assoc. 2002;133(9):1209–1217. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2002.0362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Milgrom P, Weinstein P, Heaton LJ. Treating fearful dental patients: A patient management handbook. 3rd Edition. Seattle: Dental Behavioral Resources; 2009. pp. 137–139. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Friedlander AH, Mahler ME. Major depressive disorder. Psychopathology, medical management and dental implications. J Am Dent Assoc. 2001;132(5):629–638. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2001.0240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Friedlander AH, Marder SR, Sung EC, Child JS. Panic disorder: psychopathology, medical management and dental implications. J Am Dent Assoc. 2004 Jun;135(6):771–778. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2004.0306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Friedlander AH, Marder SR. The psychopathology, medical management and dental implications of schizophrenia. J Am Dent Assoc. 2002;133(5):603–610. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2002.0236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]