Abstract

Atherosclerosis is considered as a chronic disease of arterial wall, with a strong contribution of inflammation. Dendritic cells (DCs) play a crucial role in the initiation of proatherogenic inflammatory response. Mature DCs present self-antigens thereby supporting differentiation of naïve T cells to effector cells that further propagate atherosclerotic inflammation. Regulatory T cells (Tregs) can suppress proinflammatory function of mature DCs. In contrast, immature DCs are able to induce Tregs and prevent differentiation of naïve T cells to proinflammatory effector T cells by initiating apoptosis and anergy in naïve T cells. Indeed, immature DCs showed tolerogenic and anti-inflammatory properties. Thus, DCs play a double role in atherosclerosis: mature DCs are proatherogenic while immature DCs appear to be anti-atherogenic. Tolerogenic and anti-inflammatory capacity of immature DCs can be therefore utilized for the development of new immunotherapeutic strategies against atherosclerosis.

Keywords: atherosclerosis, atherogenesis, inflammation, immune reactions, dendritic cells, arteries

Introduction

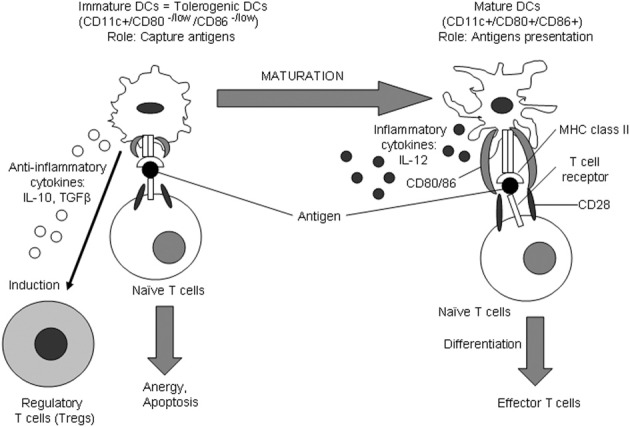

Dendritic cells (DCs) were first described by Steinman and Cohn (1973). DCs are a heterogeneous group of professional antigen-presenting cells (APCs). DCs differentiate from precursors circulating in the bloodstream (Sorg et al., 1999). The precursors can be delivered by blood to the target non-lymphoid organ or tissue, in which they become immature DCs. Immature DCs express on their surface integrin alpha X (CD11c) (Sorg et al., 1999). However, costimulatory molecules CD80/CD86 essential for T cell activation are not or expressed or produced at very low levels (Cocks et al., 1995) (Figure 1). Indeed, immature DCs can capture antigens but are not able to stimulate naïve T cells. From the target tissue, immature DCs in turn migrate to lymphoid organs such as spleen and lymph nodes in which they differentiate into mature DCs. The maturation is accompanied by enhanced expression of costimulatory molecules CD80/86 and CD40, antigen-presenting molecules (MHC class I and II), and adhesion molecules (CD11a, CD50, CD54, CD86). Mature DCs can contact and present antigens to naïve T cells, which in turn differentiate into effector T cells such T helper 1 (Th1) or 2 (Th2) cells. DCs also secrete interleukin (IL)-12, a proinflammatory cytokine that directs differentiation of naïve T cells to effector T cells (Kubin et al., 1994). Some immature DCs exhibit tolerogenic properties through the induction of regulatory T cells (Tregs) and suppression of naïve T cell activation (Steinman et al., 2003).

Figure 1.

Immature and mature DCs. Immature DCs arise from DC precursors that circulate in the blood. From the blood, DC precursors may reach the target tissue where they transform into immature DCs. The major function of immature DCs is the capture of antigens. Immature DCs capturing antigens may then migrate into lymphoid tissues such as the spleen and lymph nodes where they further differentiate becoming mature DCs. Mature DCs are capable to efficiently present captured antigens to naïve T cells. DC maturation is characterized by the up-regulation of expression of molecules responsible for antigen presentation such as MHC class II and CD80/CD86. After antigen recognition, naïve T cells differentiate into effector T cells. Differentiation of naïve T cells to effector cells may occur upon cell-cell contacts between a DC and a naïve T cell and via proinflammatory cytokine IL-12 secreted by mature DCs. Immature DCs lacking sufficient expression of antigen-presenting molecules cause anergy and apoptosis of naïve T cells. Immature DCs possess tolerogenic properties by inducing Tregs through cell-to-cell contact with naïve T cells and through secreting anti-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-10 and TGF-β. Since immature DCs are capable to induce Tregs and inhibit the inflammatory reaction in the atherosclerotic plaque, the development of strategies for the induction of tolerogenic DCs is of great therapeutic promise.

Atherosclerosis is a chronic inflammatory disease, with a pathogenic immune response driven by T lymphocytes (Hansson and Hermansson, 2011). Due to their critical role in effector T cell differentiation from naïve T cells, it is not surprisingly that DCs are found to be the key players in the proinflammatory response at the atherosclerotic plaque. The discovery of the presence of DCs in the intima of normal arteries and atherosclerotic lesions led to a suggestion that DCs might play an important role in the development of atherosclerotic lesions (Bobryshev and Lord, 1995a, b). An entire network of HLA-DR-expressing cells was eventually found to exist in the intimal space of normal human aortas (Bobryshev et al., 2012), suggesting their potential role in the regulation of vascular homeostasis. The architectonics of this network may be different in various aortic segments thereby predicting putative atherosclerosis-prone and atherosclerosis-resistant regions of the visually normal aorta (Bobryshev and Lord, 1995a).

The involvement of DCs in atherogenesis was then proven by experimental findings on two rodent atherosclerosis models such as apolipoprotein (apo) E-null and LDL receptor (LDLR)-null mice (Bobryshev et al., 1999; Paulson et al., 2010). Transfer of oxidized low density lipoprotein (oxLDL)-reactive T cells to ApoE-null severe combined immunodeficiency syndrome (Scid) mice are more effective in plaque presentation compared to the transport of non-specific T cells to an antigen derived from a lesion (Zhou et al., 2006), thereby suggesting on the involvement of those cells in presenting antigens in disease progression. DCs were observed in atherosclerotic lesions of apoE- (Bobryshev et al., 1999, 2001) and LDLR-null mice (Paulson et al., 2010), and these cells were not present in the plaques just accidentally but accumulated and contributed to the intraplaque inflammation and progression of the coronary atheroma (Ludewig et al., 2000; Hjerpe et al., 2010).

Since the identification of DCs in the arterial wall (Bobryshev and Lord, 1995a, b), the functional significance of this cell type has been intensely studied and various issues of the involvement of DCs in atherogenesis have been discussed in a number of reviews (Bobryshev, 2000, 2005, 2010; Cybulsky and Jongstra-Bilen, 2010; Niessner and Weyand, 2010; Koltsova and Ley, 2011; Manthey and Zernecke, 2011; Van Vré et al., 2011; Butcher and Galkina, 2012; Feig and Feig, 2012; Takeda et al., 2012; Alberts-Grill et al., 2013; Cartland and Jessup, 2013; Grassia et al., 2013; Koltsova et al., 2013; Subramanian and Tabas, 2014). It is important to note here that functions of DCs in human arteries are still practically unknown and that the accumulated information about functions of DCs in atherosclerosis is obtained in experimental studies. However, in contrast to the intima of human arteries which contains the nets of DCs (Bobryshev and Lord, 1995a; Bobryshev, 2000), the intima of large arteries in animal models of atherosclerosis consists of the endothelium that is separated from the internal elastic membrane by just a narrow layer of free-of-cell matrix. In humans, the activation of resident vascular DCs occurs in the very earlier stage of atherosclerosis (Bobryshev and Lord, 1995a; Bobryshev, 2000), whereas the accumulation of DCs in the arterial intima in animal models of atherosclerosis occurs as a result of the penetration of DCs or DC precursors from the blood stream, parallel with the development of atherosclerotic lesions (Bobryshev et al., 1999, 2001). Likewise, little is known about the peculiarities of functions of immature DCs vs mature DCs in human atherosclerosis (Bobryshev, 2010).

Accumulated evidence obtained in experimental studies indicates that, depending on the maturation stage, DCs play a double role in atherogenesis: mature DCs display proatherogenic features whereas immature DCs seem to be anti-atherogenic. In this review, we highlight a double role of DCs in atherogenesis. Obviously, further studies are needed in order to translate knowledge obtained in experiments to human atherogenesis.

DC subsets and their role in atherosclerosis

There are several subsets of DCs can be distinguished including conventional (myeloid) DCs (cDCs), plasmacytoid DCs (pDCs), and inflammatory DCs (Shortman and Naik, 2007). Inflammatory DCs cannot be found in the steady state but emerge after inflammatory stimuli. Unlike cDCs, pDCs are weak in antigen presentation (Shortman and Naik, 2007). However, pDCs are potent inducers of the interferon (IFN) type I response against viral and bacterial infections (Villadangos and Young, 2008). Choi et al. (2011) have proposed markers to discriminate DCs subsets in murine atherosclerosis but the function of different subsets remains to be elucidated. Although the presence of both subtypes of DCs is known in humans, the most reliable information about the functions of cDCs and pDCs are obtained in animal studies (Shortman and Naik, 2007; Villadangos and Young, 2008; Busch et al., 2014).

Normally, vascular DCs were proposed to contribute to maintaining tolerance to self-antigens; in proatherosclerotic conditions, activated vascular DCs may present self-antigens to T cells and promote inflammatory response in the plaque (Niessner and Weyand, 2010). Both pDCs and cDCs were found in the shoulder region of carotid artery lesions (Niessner et al., 2006). pDC were detected in human and mouse atherosclerotic lesions (Niessner et al., 2006; Niessner and Weyand, 2010; Daissormont et al., 2011). pDCs were shown to produce large amount of IFNα, a potent regulator of T cells, that might lead to the unstable plaque phenotype (Niessner et al., 2006). In the LDLR-null mice, pDC depletion, in contrast, led to T cell accumulation and promoted atherosclerotic lesion formation (Niessner et al., 2006). However, in a recent study, specific depletion of pDC in aortas and spleen of apoE-deficient mice was associated with significantly reduced atherosclerosis (Macritchie et al., 2012). In another study, the construction of self-response complexes loaded with patient's DNA and anti-microbial peptides enhanced early plaque formation in apoE-null mice (Döring et al., 2012).

pDS and IFNs isolated from the plaque are involved in the maturation of DCs and macrophages (Döring and Zernecke, 2012). Indeed, these findings suggest for a rather proatherogenic role of pDCs (Döring and Zernecke, 2012) that should be further elucidated. Apart from the existence of cDCs and pDCs, lesion DCs may also arise from the blood-derived monocytes that infiltrate the intima (Randolph et al., 1998). Several studies in mice and humans have addressed this issue (Jongstra-Bilen et al., 2006; Dopheide et al., 2012). Choi et al. (2011) observed in murine aorta new subtype of monocyte-derived DCs (CD11chighMHCIIhighCD11b−CD103+). According to Choi et al. (2011), DCs in murine atherosclerosis are primarily presented by two subsets: macrophage-colony stimulating factor (M-CSF)-dependent monocyte-derived DCs (CD14+CD11b+DC−SIGN+), and classical Flt3-Flt3L signaling-dependent cells (CD103+CD11b−). Although there might be a wide spectrum of DCs subsets in the intima of arteries, the functioning of DCs largely depends on the maturation stage (Butcher and Galkina, 2012).

Immature CD1a+S100+lag+CD31−CD83−CD86− DCs were found in the normal aortic intima of young individuals (Millonig et al., 2001). HLA-DR+CD1a+S-100+ DCs were found in the normal human aorta, carotid arteries and in atherosclerotic plaques (Bobryshev and Lord, 1995a; Bobryshev, 2000). DCs are also located in the under-plaque media and in the adventitia around the vasa vasorum in the shoulder regions of the atherosclerotic lesion (Bobryshev and Lord, 1998). Mature CD83 positive DCs were observed in rupture-prone plaque regions in human carotid arteries (Yilmaz et al., 2004). These studies showed that heterogeneity of the DC population seems to increase progressively during the plaque progression.

There are several pathways by which DC numbers can be increased within atherosclerotic plaques. DCs and their precursors could infiltrate plaques migrating from the bloodstream by a chemokine- and adhesion molecule-dependent pathway (Niessner and Weyand, 2010). DCs can migrate to advanced lesions from the adventitia during vasa vasorum-associated neovascularization (Bobryshev and Lord, 1998). The third way is associated with monocytes that penetrate the intima at early atherosclerosis steps in order to differentiate into macrophages or DCs in response to inflammatory stimuli (Randolph et al., 1998). Therefore, inhibition of the activation and recruitment of increasing numbers of activated DCs may be important in preventing lesion formation.

Role of DCs in induction of t-cell mediated proinflammatory response in the atherosclerotic lesion

As mentioned above, immature DCs having CD11c+CD80−/lowCD86−/low phenotype are tolerogenic DCs responsible for capturing antigens. These DCs might play anti-inflammatory role because they may induce apoptosis or anergy in naïve T cells responding to self-antigens (Kushwah and Hu, 2011). By capturing antigens, immature DCs differentiate into mature DCs. Mature CD11c+CD80+CD86+ DCs, in contrast, may play a proinflammatory role by presenting self-antigens to naïve T cells, which then differentiate to effector T cells, and by secreting inflammatory cytokines such as IL-12. During the late stage of monocyte differentiation, oxLDL promote maturating DCs into IL-12-producing cells, which further support inflammatory reaction in the plaque (Perrin-Cocon et al., 2001). Furthermore, in LDLR−/− mice, resident intimal DCs were shown to rapidly accumulate oxLDL and initiate nascent foam cell lesion formation (Paulson et al., 2010). By presenting antigens, mature DCs and macrophages induce adaptive T-cell mediated immune response (Paulson et al., 2010; Choi et al., 2011). However, there is conflicting evidence on the role of oxLDL (and hyperlipidemia) on the maturation and function of DCs (Perrin-Cocon et al., 2001, 2013; Ge et al., 2011; Nickel et al., 2012; Peluso et al., 2012). A recent study by Hermansson et al. (2011) revealed that native LDL can also be recognized by DCs.

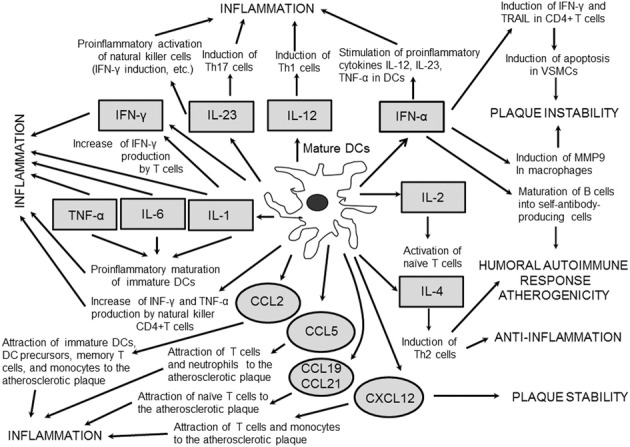

In shoulders of human vulnerable atherosclerotic plaques, CD83+ DCs were identified in the vicinity to CD40L+ T cells (Yilmaz et al., 2006). This population of DCs secrete CC-motif chemokines (CCL)19 and CCL21 capable to enhance recruitment of naive lymphocytes into atherosclerotic vessels (Erbel et al., 2007) (Figure 2). pDCs responded to pathogen-derived motifs and CpG-containing oligodeoxynucleotides by elevated production of IFN α that recruits naïve T cells, which then differentiate into cytotoxic CD4+ effector T cells capable to effectively kill vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs) (Niessner et al., 2006). Therefore, in the atherosclerotic lesion, pDCs are able to sense microbial motifs and accelerate activity of cytotoxic T-lymphocytes thereby providing a link between severe immune-mediated atherosclerotic complications and infections. CD4+ T cells derived from atherosclerotic plaques are capable to recognize oxLDL, heat shock proteins (HSP)60/65, and other antigens from pathogenic microorganisms such as Chlamydia pneumonia, which are supposed to be candidate self-antigens for atherogenesis (Stemme et al., 1995; Benagiano et al., 2005; Mandal et al., 2005). Stephens et al. (2008) showed the ability of a self-peptide Ep1.B derived from human apoE to induce differentiation of monocytes to DCs, thereby suggesting for a putative mechanism of self-antigen-mediated induction of inflammation at early stages of atherosclerosis. Immunochemical staining revealed the presence of C. pneumonia in DCs derived from atherosclerotic plaques thus supporting again a likely role of DCs as a bridge linking the pathogen-induced proinflammatory responses to the induction of atherogenesis (Bobryshev et al., 2004).

Figure 2.

Cytokines and chemokines produced by mature DCs in the atherosclerotic vessels. DC-derived cytokines mostly possess proinflammatory and proatherogenic properties. Chemokines secreted by mature DCs stimulate chemotaxis of a variety of immune cells to attract them to the atherosclerotic lesion.

Crosstalks between DCs and tregs in atherosclerosis

Tregs are involved in the activation, maturation, and function of DCs (Steinman and Banchereau, 2007; Chistiakov et al., 2013). By CTLA-4-dependent inhibition of CD80/CD86 expression in proatherogenic DCs, Tregs are capable to suppress their antigen-presenting activity (Onishi et al., 2008). CTLA-4 is expressed only in stimulated Tregs including forkhead box P3 (Foxp3)+ Tregs. Tregs. CTLA-4 interacts with B7-1 (CD80) and B7-2 (CD86) molecules broadly presented in the surface of DCs and macrophages and conducts an inhibitory signal to DCs decreasing expression of both costimulators (Bour-Jordan et al., 2011). Through binding to CD80/CD86, CTLA-4 could initiate production of indoleamine 2,3-dioxigenase (IDO) in DCs. IDO converts tryptophane to kinurenine that is a potent immunosuppressant capable to induce de novo formation of Tregs from naïve T cells in the local environment (Fallarino et al., 2003).

The second inhibitory pathway by which Tregs interacting with mature DCs can down-regulate antigen presentation is CD80/CD86 trogocytosis, which is a process of intercellular transfer of cell surface proteins and outer membrane fragments (Gu et al., 2012). Trogocytosis is mediated with CD28, CTLA-4, and programmed death ligand 1 (PDL-1) and involves CD80/CD86 removal from the surface of DCs therefore increasing the inhibitory capacity of Tregs. Tregs from the CTLA-4-knockdown mice failed to suppress CD80/CD86 production suggesting for a key role of CTLA-4 in the suppression of CD80/CD86 expression in antigen-presenting mature DCs (Gao et al., 2011). CTLA-4 binding to CD80/CD86 on the surface of DCs has a major role in inducing tolerance (Oderup et al., 2006). Indeed, CTLA-4 may represent a promising target for treatment of atherosclerosis by enhancing the inhibitory activity of Tregs or increasing suppression of effector T cells (Gotsman et al., 2008).

T-cell adhesion molecule lymphocyte-associated antigen 1 (LFA-1) mediates contact between an antigen-presenting DC and a Treg (Onishi et al., 2008). Tregs maintain the CD80/CD86-suppressing capacity even if potent DC-maturating stimuli are present. Thus, Tregs may effectively block proinflammatory signals from antigen-presenting DCs to naive T-lymphocytes via binding to immature DCs followed by CTLA-4/LFA-1-mediated down-regulation of CD80/CD86 production in DCs. Indeed, DCs can influence function of Tregs through their inhibition or stimulation. Proatherosclerotic CCL17+CD11+ DCs capable to down-regulate Tregs have been found (Weber et al., 2011). Also, a population of atheroprotective monocyte-derived CD11highMHChighCD11b−CD103+ DCs which are able to induce Tregs in the lesion was identified (Choi et al., 2011).

Lievens et al. (2013) have constructed an apoE-null mouse harboring a transgene whose expression causes inactivation of tumor factor growth-β receptor II (TGFβRII)-dependent signaling in CD11-positive DCs. Prevention of TGFβ RII signaling mechanism results in shifting of CD11c+CD8− DCs toward the more proinflammatory CD11c+ population, which resulted in enhanced T cell activation and maturation and advanced atherosclerosis. These observations suggest for an anti-atherogenic role of TGFβ signaling that may be responsible for maintaining immunosupressory properties in DCs and preventing their differentiation toward the proinflammatory phenotype.

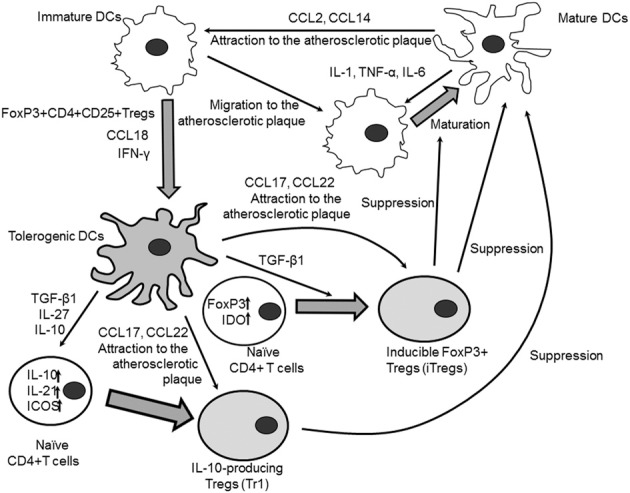

Most tolerogenic DCs are immature and have CD86−CD80−CD40−MHCII− phenotype (Maldonado and von Andrian, 2010). These cells can induce Tregs by direct interaction or through production of cytokines TGF-β and IL-10. IL-10 mediates differentiation of peripheral T-cells to Tregs. Tolerogenic DCs producing IL-10 are implicated in the induction of IL-10-producing type 1 regulatory T cells (Tr1) (Figure 3). Tregs and DCs interact to each other via CCL17 and CCL22, and their receptors, chemokine receptors (CCR) 4 and 8 Iellem et al., 2001; Weber et al., 2011). These receptors are produced on the surface of Tregs and may bind DCs-secreted CCL17 and CCl22. CCL22 induction on tolerogenic CDs results in the recruitment of Tregs in the site of inflammation including the atherosclerotic lesion. The CCR4-deficient mice showed significantly decreased expression of IDO in DCs from mesenteric lymph nodes (Onodera et al., 2009). This finding could suggest for a role of IDO in the regulation of activating effect of CCL22 and CCR4 on Tregs induction. Overall, these observations show that the immunoregulating enzyme IDO has a crucial role in regulating reciprocal DCs-Tregs contacts mediated by B7/CTLA-4 and CCL22/CCR4 in atherogenesis. Therefore, inducing tolerogenic DCs may be important for enhancing protective effects of Trgs against atherosclerosis.

Figure 3.

Crosstalk between immature and mature DCs. Mature DCs could attract immature DCs and DC precursors to the site of inflammation (i.e., to the atherosclerotic plaque) through secretion of chemokines CCL2 and CCL14. Immature DCs in turn migrate to the plaque where they are activated by the local proinflammatory microenvironment to differentiate preferentially to inflammatory mature antigen-presenting DCs. Local mature DCs could contribute to the proinflammatory DC maturation by secreting inflammatory cytokines IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α. Natural FoxP3+CD4+CD25+ T cells induce conversion of immature DCs to tolerogenic DCs. Chemokine CCL18 produced by immature DCs stimulates tolerogenicity through the induction of IL-10-mediated expression of IDO in DCs. IFN-γ is able to contribute to the formation of tolerogenic DCs by inhibiting expression of Th17-inducing osteoprotegerin and stimulating IL-27 production. IL-27 suppresses production of Th17-polarizing cytokines IL-1β, IL-6, and IL-23 from DCs and activates expression of IL-10, IL-21, and ICOS in naïve CD4+ T cells that drives induction of IL-10 producing Tregs (Tr1). IL-10 produced by tolerogenic DCs induces Tr1 cells through the ILT2/ILT4-mediated signaling mechanism. TGF-β 1 secreted by tolerogenic DCs could induce expression of FoxP3 and IDO in CD4+CD25− naive T cells that promotes their conversion into inducible FoxP3+ Tregs (iTregs). Chemokines CCL17 and CCL22 secreted by tolerogenic CDs attract Tregs to the atherosclerotic lesion where Tregs could suppress immunomodulatory properties of proinflammatory antigen-presenting CDs and prevent differentiation of immature CDs to inflammatory subsets of mature DCs.

Progress toward the clinic

In addition to the above suggestion that the development of strategies for the induction of tolerogenic DCs may be of great therapeutic promise, it is important to noting here that the accumulated evidence has showed that, indeed, DCs might be used for anti-atherosclerosis immunotherapy. The support for this view has come from a number of studies performed on mouse models of atherosclerosis in which the function of DCs was manipulated (Zhou et al., 2006; Hjerpe et al., 2010; Daissormont et al., 2011; de Jager and Kuiper, 2011; Döring et al., 2012; Macritchie et al., 2012). Currently, there is no sufficient evidence to state that cDCs are proatherogenic and that pDCs are atheroprotective. Nevertheless, based on the assumption that cDCs action is rather proatherogenic whereas pDCs might be atheroprotective, the inhibition of cDCs can induce atheroprotective immune reactions (Bobryshev, 2010).

DCs are thought nowadays as a valuable instrument for atherosclerosis immunotherapy (Van Vré et al., 2011; Takeda et al., 2012; Grassia et al., 2013; Van Brussel et al., 2013, 2014). DCs could also induce tolerance against antigens that are innate to the body (Steinman et al., 2003; Palucka and Banchereau, 2012). DCs can be used as natural adjuvants for the induction of antigen-specific T-cell responses (Caminschi et al., 2012; Palucka and Banchereau, 2012; Yamanaka and Kajiwara, 2012). Anti-atherosclerotic immunotherapy with the utilization of DCs may be the same or somewhat different from those approaches that are currently used for cancer immunotherapy (Caminschi et al., 2012; Palucka and Banchereau, 2012; Yamanaka and Kajiwara, 2012). It is essential to stress that remarkable results have been achieved in treatment of cancer patients when DCs loaded with an antigen were used as vaccines for improving the host anti-cancer immune response (Palucka and Banchereau, 2012; Yamanaka and Kajiwara, 2012). One of approaches involves an ex vivo treatment of DCs with an appropriate antigen, followed by further return of the antigen-treated DCs (so called “pulsed” DCs) back to the patient' blood. A similar approach can be evaluated for the use in atherosclerosis immunotherapy (Bobryshev, 2001).

One of the main challenges for developing of effective vaccines for atherosclerosis relates to the selection of a specific antigen to target. Several strategies have been offered; So far, vaccination strategies have been based on targeting of lipid antigens and inflammation-derived antigens (de Jager and Kuiper, 2011). Amongst the used approaches, immunization of hypercholesterolemic animals with oxLDL or specific epitopes of ApoB100 has been reported to inhibit atherosclerosis (Nilsson et al., 2007; van Leeuwen et al., 2009). Perhaps, DCs pulsed with autologous modified LDL or immunogenic components of autologous modified LDL could be used as well for immunization; this would allow avoiding side effects of direct vaccination with oxLDL (Bobryshev, 2010). Apart from pulsation with modified LDL, DCs can be also treated ex vivo through culturing with a total extract of the “own” atherosclerotic lesion, for instance, from subjects who underwent carotid enadarterectomy or other vascular interventions (Bobryshev, 2001). An obvious advantage of such approach, in which a patient is vaccinated with its “own” DCs pulsed by patient's “own” antigens is the specificity: the event of pulsation of DCs would mimic the processes that occur in plaques of the patient. This approach can be considered as an example of “personalized” medicine (Hamburg and Collins, 2010).

Although the idea to use of DCs for vaccination in atherosclerosis is widely discussed (de Jager and Kuiper, 2011; Van Vré et al., 2011; Cheong and Choi, 2012; Döring and Zernecke, 2012; Takeda et al., 2012; Van Brussel et al., 2013, 2014), experimental studies that already utilized DCs for immunotherapy of atherosclerosis are still quite limited (Habets et al., 2010; Hjerpe et al., 2010; van Es et al., 2010; Hermansson et al., 2011; Pierides et al., 2013). Currently, an immunotherapeutic strategy based on the isolation of autologous DCs, subsequent loading with appropriate antigen(s) ex vivo (e.g., immunogenic epitopes of modified LDL or a total plaque extract), and return to the host blood is under development (Habets et al., 2010; Hjerpe et al., 2010; van Es et al., 2010; Hermansson et al., 2011; Pierides et al., 2013) (Table 1). The future of this strategy is consisted in the development of atheroprotective vaccines on the basis of patient's DCs (Van Brussel et al., 2013).

Table 1.

Examples of anti-atherosclerosis immunization of experimental atherosclerosis animal models involving LDL or its related peptides.

| Animals | Immunogenes | Effect on atherosclerosis | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| LDLR-null rabbits | MDA-LDL | 1.5-fold decrease in the extent of aortic lesions | Palinski et al., 1995 |

| NZW rabbits on fat-rich diet | Native LDL or Cu2+-oxidized LDL | Reduction in aortic plaques by 74% (native LDL) and 48% (oxLDL) | Ameli et al., 1996 |

| LDLR-null mice | Native LDL or MDA-LDL | Reduction in aortic sinus plaques by 46.3% (MDA-LDL) and 36.9% (native LDL) | Freigang et al., 1998 |

| ApoE-null mice | MDA-LDL | 2.1-fold decrease in the size of aortic sinus lesions | George et al., 1998 |

| ApoE-null mice | apoB-100 peptides (p143 and p210) | Reduction in aortic atherosclerosis by 60% | Fredrikson et al., 2003 |

| ApoE-null mice | Native LDL | 1.7-fold decrease in the size of aortic sinus lesions | Chyu et al., 2004 |

| ApoE-null mice | apoB-100 peptides (p143 and p210) | Reduction of aortic atherosclerosis by 40% and plaque inflammation by 89% (p210) | Chyu et al., 2005 |

| LDLR-null mice | oxLDL or MDA-LDL | Attenuation of the initiation (30–71%) and progression (45%) of atherogenesis | van Puijvelde et al., 2006 |

| LDLR-null apoB-transgenic mice | apoB-100 peptides (p45 and p210) | Reduction of aortic atherosclerosis by 66% (p45) and 59% (p210) | Klingenberg et al., 2010 |

| ApoE-null mice | apoB peptide (p210) | Reduction in aortic sinus lesion size by 35% | Fredrikson et al., 2008 |

| ApoE-null mice | DCs pulsed with MDA-LDL | Significant increase in aortic lesion size and inflammation | Hjerpe et al., 2010 |

| LDLR-null mice | DCs pulsed with Cu2+-oxidized LDL | 87% decrease in carotid artery lesion size and increase in plaque stability | Habets et al., 2010 |

| LDLR-null mice | DCs transfected with FoxP3 mRNA | Reduction of Foxp3+ Tregs cells in several organs; increase in initial atherosclerotic lesion formation and in plaque cellularity | van Es et al., 2010 |

| LDLR-null apoB100-transgenic mice | DCs loaded with apoB-100 | 70% reduction in aortic lesions and inflammation | Hermansson et al., 2011 |

| ApoE-null mice | DCs loaded with apoB peptides (p2, p45, and p210) | 50% decrease in plaque development | Pierides et al., 2013 |

apo, apolipoprotein; FoxP3, forkhead box P3; LDL, low density lipoprotein; LDLR, LDL receptor; MDA-LDL, malonaldehyde-modified LDL; NZW, New Zealand White; oxLDL, oxidized LDL; Tregs, regulatory T cells.

Another promising strategy involves studying properties of various immune cells interacting with DCs in order to develop DCs-based vaccines capable to modulate those immune cells in atherosclerosis. For example, van Es et al. (2010) used DCs expressing a FoxP3 transgene, a master regulator in the development and function of Tregs, to induce the anti-FoxP3 immune response in LDLR-null mice. The anti-FoxP3-specific immunity resulted in partial depletion of FoxP3-positive Tregs in several organs, early induction of proatherogenic inflammation and advanced atherosclerotic plaque progression. This observation indeed suggests for the crucial atheroprotective properties of Tregs.

An adoptive transfer of natural killer T (NKT) cells from Vα14Jα18 T-cell receptor transgenic mice caused significant progression in aortic atherosclerosis in recipient immune-deficient RAG-null LDLR-null mice (VanderLaan et al., 2007). Serum derived from the recipient animals then induced activation of Vα14Jα18 T-cell receptor-expressing hybridoma by DCs. This finding shows proatherogenic properties of CD1d-dependent Vα14 subpopulation of NKT cells that were likely to be stimulated by circulating endogenic lipoproteins in the atherosclerosis-prone animals (Rogers et al., 2008). Thus, such an approach may offer a tool for dissecting the contributions of individual subpopulations of particular immune cells to the process of atherogenesis. In the future, developing immune vaccines on the basis of specific subsets of DCs should be helpful for selective depletion of deleterious proatherogenic populations of effector cells such as Th1 and Th17 cells and induction of immunosuppressive anti-inflammatory Tregs (Van Brussel et al., 2013).

Concluding remarks

It is appreciated nowadays that atherosclerosis is a chronic destruction of aortic and arterial walls, with a marked involvement of inflammation (Hansson and Hermansson, 2011; Tuttolomondo et al., 2012). DCs are recognized as key players in the induction of inflammatory response in the atherosclerotic plaque. It has become known that T cell activation occurs after a cell-to-cell-contact between a DC and a naïve T cells and by stimulation of the proinflammatory cytokines secreted by mature DCs. A proinflammatory function of mature DCs may be suppressed by a special subclass of T cells, namely by Tregs. On the other hand, immature DCs possess tolerogenic anti-inflammatory properties by leading naïve T cells to anergy or apoptosis and by inducing Tregs. Thus, depending on the maturation stage, DCs play a double role in atherogenesis: mature DCs display proatherogenic features whereas immature DCs seem to be anti-atherogenic. Since immature DCs are capable to induce Tregs and inhibit the inflammatory reaction in the atherosclerotic lesion, the development of strategies for the induction of tolerogenic DCs may be of great therapeutic promise.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank the Russian Ministry of Education and Science and the School of Medical Sciences, University of New south Wales, Sydney, Australia, for support of our work.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- APCs

antigen-presenting cells

- apo (Apo)

apolipoprotein

- C. pneumonia

Chlamydia pneumonia

- CCL

CC-motif chemokines

- CCR

chemokine receptors

- CD

cluster of differentiation

- cDCs

myeloid DCs

- CTLA-4

cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen-4

- DC

Dendritic cell

- DCs

Dendritic cells

- DNA

deoxyribonucleic acid

- FoxP3

forkhead box P3

- IDO

indoleamine 2,3-dioxigenase

- IL

interleukin

- iTregs

FoxP3+ Tregs

- LDL

low density lipoprotein

- LDLR

LDL receptor

- LFA-1

lymphocyte function-associated antigen 1

- M-CSF

macrophage-colony stimulating factor

- MDA-LDL

malonaldehyde-modified LDL

- MHC

major histocompatibility complex

- NKT cells

natural killer T cells

- NZW

New Zealand White

- oxLDL

oxidized LDL

- pDCs

plasmacytoid DCs

- PDL-1

programmed death ligand 1

- Scid

severe combined immunodeficiency syndrome

- TGFßRII

tumor factor growth-ß receptor II

- Th

T helper

- Tr1

type 1 regulatory T cells

- Tregs

regulatory T cells

- VSMCs

vascular smooth muscle cells.

References

- Alberts-Grill N., Denning T. L., Rezvan A., Jo H. (2013). The role of the vascular dendritic cell network in atherosclerosis. Am. J. Physiol. Cell. Physiol. 305, C1–C21 10.1152/ajpcell.00017.2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ameli S., Hultgårdh-Nilsson A., Regnström J., Calara F., Yano J., Cercek B., et al. (1996). Effect of immunization with homologous LDL and oxidized LDL on early atherosclerosis in hypercholesterolemic rabbits. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 16, 1074–1079 10.1161/01.ATV.16.8.1074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benagiano M., D'Elios M. M., Amedei A., Azzurri A., van der Zee R., Ciervo A., et al. (2005). Human 60-kDa heat shock protein is a target autoantigen of T cells derived from atherosclerotic plaques. J. Immunol. 174, 6509–6517 10.4049/jimmunol.174.10.6509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bobryshev Y. V. (2000). Dendritic cells and their involvement in atherosclerosis. Curr. Opin. Lipidol. 11, 511–517 10.1097/00041433-200010000-00009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bobryshev Y. V. (2001). Can dendritic cells be exploited for therapeutic intervention in atherosclerosis? Atherosclerosis 154, 511–512 10.1016/S0021-9150(00)00692-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bobryshev Y. V. (2005). Dendritic cells in atherosclerosis: current status of the problem and clinical relevance. Eur. Heart J. 26, 1700–1704 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bobryshev Y. V. (2010). Dendritic cells and their role in atherogenesis. Lab. Invest. 90, 970–984 10.1038/labinvest.2010.94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bobryshev Y. V., Babaev V. R., Lord R. S., Watanabe T. (1999). Ultrastructural identification of cells with dendritic cell appearance in atherosclerotic aorta of apolipoprotein E deficient mice. J. Submicrosc. Cytol. Pathol. 31, 527–531 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bobryshev Y. V., Cao W., Phoon M. C., Tran D., Chow V. T., Lord R. S., et al. (2004). Detection of Chlamydophila pneumoniae in dendritic cells in atherosclerotic lesions. Atherosclerosis 173, 185–195 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2003.12.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bobryshev Y. V., Lord R. S. (1995a). Ultrastructural recognition of cells with dendritic cell morphology in human aortic intima. Contacting interactions of Vascular Dendritic Cells in athero-resistant and athero-prone areas of the normal aorta. Arch. Histol. Cytol. 58, 307–322 10.1679/aohc.58.307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bobryshev Y. V., Lord R. S. (1995b). S-100 positive cells in human arterial intima and in atherosclerotic lesions. Cardiovasc. Res. 29, 689–696 10.1016/0008-6363(96)88642-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bobryshev Y. V., Lord R. S. (1998). Mapping of vascular dendritic cells in atherosclerotic arteries suggests their involvement in local immune-inflammatory reactions. Cardiovasc. Res. 37, 799–810 10.1016/S0008-6363(97)00229-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bobryshev Y. V., Moisenovich M. M., Pustovalova O. L., Agapov I. I., Orekhov A. N. (2012). Widespread distribution of HLA-DR-expressing cells in macroscopically undiseased intima of the human aorta: a possible role in surveillance and maintenance of vascular homeostasis. Immunobiology 217, 558–568 10.1016/j.imbio.2011.03.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bobryshev Y. V., Taksir T., Lord R. S., Freeman M. W. (2001). Evidence that dendritic cells infiltrate atherosclerotic lesions in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. Histol. Histopathol. 16, 801–808 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bour-Jordan H., Esensten J. H., Martinez-Llordella M., Penaranda C., Stumpf M., Bluestone J. A. (2011). Intrinsic and extrinsic control of peripheral T-cell tolerance by costimulatory molecules of the CD28/B7 family. Immunol. Rev. 241, 180–205 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2011.01011.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busch M., Westhofen T. C., Koch M., Lutz M. B., Zernecke A. (2014). Dendritic cell subset distributions in the aorta in healthy and atherosclerotic mice. PLoS ONE 9:e88452 10.1371/journal.pone.0088452 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butcher M. J., Galkina E. V. (2012). Phenotypic and functional heterogeneity of macrophages and dendritic cell subsets in the healthy and atherosclerosis-prone aorta. Front. Physiol. 3:44 10.3389/fphys.2012.00044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caminschi I., Maraskovsky E., Heath W. R. (2012). Targeting dendritic cells in vivo for cancer therapy. Front. Immunol. 3:13 10.3389/fimmu.2012.00013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cartland S. P., Jessup W. (2013). Dendritic cells in atherosclerosis. Curr. Pharm. Des. 19, 5883–5890 10.2174/1381612811319330007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheong C., Choi J. H. (2012). Dendritic cells and regulatory T cells in atherosclerosis. Mol. Cells 34, 341–347 10.1007/s10059-012-0128-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chistiakov D. A., Sobenin I. A., Orekhov A. N. (2013). Regulatory T cells in atherosclerosis and strategies to induce the endogenous atheroprotective immune response. Immunol. Lett. 151, 10–22 10.1016/j.imlet.2013.01.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi J. H., Cheong C., Dandamudi D. B., Park C. G., Rodriguez A., Mehandru S., et al. (2011). Flt3 signaling-dependent dendritic cells protect against atherosclerosis. Immunity 35, 819–831 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.09.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chyu K. Y., Reyes O. S., Zhao X., Yano J., Dimayuga P., Nilsson J., et al. (2004). Timing affects the efficacy of LDL immunization on atherosclerotic lesions in apo E (-/-) mice. Atherosclerosis 176, 27–35 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2004.04.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chyu K. Y., Zhao X., Reyes O. S., Babbidge S. M., Dimayuga P. C., Yano J., et al. (2005). Immunization using an Apo B-100 related epitope reduces atherosclerosis and plaque inflammation in hypercholesterolemic apo E (-/-) mice. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 338, 1982–1989 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.10.141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cocks B. G., Chang C. C., Carballido J. M., Yssel H., de Vries J. E., Aversa G. (1995). A novel receptor involved in T-cell activation. Nature 376, 260–263 10.1038/376260a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cybulsky M. I., Jongstra-Bilen J. (2010). Resident intimal dendritic cells and the initiation of atherosclerosis. Curr. Opin. Lipidol. 21, 397–403 10.1097/MOL.0b013e32833ded96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daissormont I. T., Christ A., Temmerman L., Sampedro Millares S., Seijkens T., Manca M., et al. (2011). Plasmacytoid dendritic cells protect against atherosclerosis by tuning T-cell proliferation and activity. Circ. Res. 109, 1387–1395 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.256529 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Jager S. C., Kuiper J. (2011). Vaccination strategies in atherosclerosis. Thromb. Haemost. 106, 796–803 10.1160/TH11-05-0369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dopheide J. F., Obst V., Doppler C., Radmacher M. C., Scheer M., Radsak M. P., et al. (2012). Phenotypic characterisation of pro-inflammatory monocytes and dendritic cells in peripheral arterial disease. Thromb. Haemost. 108, 1198–1207 10.1160/TH12-05-0327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Döring Y., Manthey H. D., Drechsler M., Lievens D., Megens R. T., Soehnlein O., et al. (2012). Auto-antigenic protein-DNA complexes stimulate plasmacytoid dendritic cells to promote atherosclerosis. Circulation 125, 1673–1683 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.046755 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Döring Y., Zernecke A. (2012). Plasmacytoid dendritic cells in atherosclerosis. Front. Physiol. 3:230 10.3389/fphys.2012.00230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erbel C., Sato K., Meyer F. B., Kopecky S. L., Frye R. L., Goronzy J. J., et al. (2007). Functional profile of activated dendritic cells in unstable atherosclerotic plaque. Basic Res. Cardiol. 102, 123–132 10.1007/s00395-006-0636-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fallarino F., Grohmann U., Hwang K. W., Orabona C., Vacca C., Bianchi R., et al. (2003). Modulation of tryptophan catabolism by regulatory T cells. Nat. Immunol. 4, 1206–1212 10.1038/ni1003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feig J. E., Feig J. L. (2012). Macrophages, dendritic cells, and regression of atherosclerosis. Front. Physiol. 3:286 10.3389/fphys.2012.00286 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredrikson G. N., Björkbacka H., Söderberg I., Ljungcrantz I., Nilsson J. (2008). Treatment with apo B peptide vaccines inhibits atherosclerosis in human apo B-100 transgenic mice without inducing an increase in peptide-specific antibodies. J. Intern. Med. 264, 563–570 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2008.01995.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredrikson G. N., Söderberg I., Lindholm M., Dimayuga P., Chyu K. Y., Shah P. K., et al. (2003). Inhibition of atherosclerosis in apoE-null mice by immunization with apoB-100 peptide sequences. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 23, 879–884 10.1161/01.ATV.0000067937.93716.DB [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freigang S., Hörkkö S., Miller E., Witztum J. L., Palinski W. (1998). Immunization of LDL receptor-deficient mice with homologous malondialdehyde-modified and native LDL reduces progression of atherosclerosis by mechanisms other than induction of high titers of antibodies to oxidative neoepitopes. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 18, 1972–1982 10.1161/01.ATV.18.12.1972 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao J. F., McIntyre M. S., Juvet S. C., Diao J., Li X., Vanama R. B., et al. (2011). Regulation of antigen-expressing dendritic cells by double negative regulatory T cells. Eur. J. Immunol. 41, 2699–2708 10.1002/eji.201141428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge J., Yan H., Li S., Nie W., Dong K., Zhang L., et al. (2011). Changes in proteomics profile during maturation of marrow-derived dendritic cells treated with oxidized low-density lipoprotein. Proteomics 11, 1893–1902 10.1002/pmic.201000658 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George J., Afek A., Gilburd B., Levkovitz H., Shaish A., Goldberg I., et al. (1998). Hyperimmunization of apo-E-deficient mice with homologous malondialdehyde low-density lipoprotein suppresses early atherogenesis. Atherosclerosis 138, 147–152 10.1016/S0021-9150(98)00015-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotsman I., Sharpe A. H., Lichtman A. H. (2008). T-cell costimulation and coinhibition in atherosclerosis. Circ. Res. 103, 1220–1231 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.182428 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grassia G., Macritchie N., Platt A. M., Brewer J. M., Garside P., Maffia P. (2013). Plasmacytoid dendritic cells: Biomarkers or potential therapeutic targets in atherosclerosis? Pharmacol. Ther. 137, 172–182 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2012.10.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu P., Gao J. F., D'Souza C. A., Kowalczyk A., Chou K. Y., Zhang L. (2012). Trogocytosis of CD80 and CD86 by induced regulatory T cells. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 9, 136–146 10.1038/cmi.2011.62 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Habets K. L., van Puijvelde G. H., van Duivenvoorde L. M., van Wanrooij E. J., de Vos P., Tervaert J. W., et al. (2010). Vaccination using oxidized low-density lipoprotein-pulsed dendritic cells reduces atherosclerosis in LDL receptor-deficient mice. Cardiovasc. Res. 85, 622–630 10.1093/cvr/cvp338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamburg M. A., Collins F. S. (2010). The path to personalized medicine. N. Engl. J. Med. 363, 301–304 10.1056/NEJMp1006304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansson G. K., Hermansson A. (2011). The immune system in atherosclerosis. Nat. Immunol. 12, 204–212 10.1038/ni.2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermansson A., Johansson D. K., Ketelhuth D. F., Andersson J., Zhou X., Hansson G. K. (2011). Immunotherapy with tolerogenic apolipoprotein B-100-loaded dendritic cells attenuates atherosclerosis in hypercholesterolemic mice. Circulation 123, 1083–1091 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.973222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hjerpe C., Johansson D., Hermansson A., Hansson G. K., Zhou X. (2010). Dendritic cells pulsed with malondialdehyde modified low density lipoprotein aggravate atherosclerosis in Apoe(-/-) mice. Atherosclerosis 209, 436–441 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2009.10.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iellem A., Mariani M., Lang R., Recalde H., Panina-Bordignon P., Sinigaglia F., et al. (2001). Unique chemotactic response profile and specific expression of chemokine receptors CCR4 and CCR8 by CD4(+)CD25(+) regulatory T cells. J. Exp. Med. 194, 847–853 10.1084/jem.194.6.847 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jongstra-Bilen J., Haidari M., Zhu S. N., Chen M., Guha D., Cybulsky M. I. (2006). Low-grade chronic inflammation in regions of the normal mouse arterial intima predisposed to atherosclerosis. J. Exp. Med. 203, 2073–2083 10.1084/jem.20060245 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klingenberg R., Lebens M., Hermansson A., Fredrikson G. N., Strodthoff D., Rudling M., et al. (2010). Intranasal immunization with an apolipoprotein B-100 fusion protein induces antigen-specific regulatory T cells and reduces atherosclerosis. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 30, 946–952 10.1161/ATVBAHA.109.202671 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koltsova E. K., Hedrick C. C., Ley K. (2013). Myeloid cells in atherosclerosis: a delicate balance of anti-inflammatory and proinflammatory mechanisms. Curr. Opin. Lipidol. 24, 371–380 10.1097/MOL.0b013e328363d298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koltsova E. K., Ley K. (2011). How dendritic cells shape atherosclerosis. Trends Immunol. 32, 540–547 10.1016/j.it.2011.07.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubin M., Kamoun M., Trinchieri G. (1994). Interleukin 12 synergizes with B7/CD28 interaction in inducing efficient proliferation and cytokine production of human T cells. J. Exp. Med. 180, 211–222 10.1084/jem.180.1.211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kushwah R., Hu J. (2011). Role of dendritic cells in the induction of regulatory T cells. Cell. Biosci. 1, 20 10.1186/2045-3701-1-20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lievens D., Habets K. L., Robertson A. K., Laouar Y., Winkels H., Rademakers T., et al. (2013). Abrogated transforming growth factor beta receptor II (TGFβ RII) signalling in dendritic cells promotes immune reactivity of T cells resulting in enhanced atherosclerosis. Eur. Heart. J. 34, 3717–3727 10.1093/eurheartj/ehs106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludewig B., Freigang S., Jäggi M., Kurrer M. O., Pei Y. C., Vlk L., et al. (2000). Linking immune-mediated arterial inflammation and cholesterol-induced atherosclerosis in a transgenic mouse model. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97, 12752–12757 10.1073/pnas.220427097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macritchie N., Grassia G., Sabir S. R., Maddaluno M., Welsh P., Sattar N., et al. (2012). Plasmacytoid dendritic cells play a key role in promoting atherosclerosis in apolipoprotein e-deficient mice. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 32, 2569–2579 10.1161/ATVBAHA.112.251314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maldonado R. A., von Andrian U. H. (2010). How tolerogenic dendritic cells induce regulatory T cells. Adv. Immunol. 108, 111–165 10.1016/B978-0-12-380995-7.00004-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandal K., Jahangiri M., Xu Q. (2005). Autoimmune mechanisms of atherosclerosis. Handb. Exp. Pharmacol. 170, 723–743 10.1007/3-540-27661-0_27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manthey H. D., Zernecke A. (2011). Dendritic cells in atherosclerosis: functions in immune regulation and beyond. Thromb. Haemost. 106, 772–778 10.1160/TH11-05-0296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millonig G., Niederegger H., Rabl W., Hochleitner B. W., Hoefer D., Romani N., et al. (2001). Network of vascular-associated dendritic cells in intima of healthy young individuals. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 21, 503–508 10.1161/01.ATV.21.4.503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nickel T., Pfeiler S., Summo C., Kopp R., Meimarakis G., Sicic Z., et al. (2012). oxLDL downregulates the dendritic cell homing factors CCR7 and CCL21. Mediators Inflamm. 2012:320953 10.1155/2012/320953 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niessner A., Sato K., Chaikof E. L., Colmegna I., Goronzy J. J., Weyand C. M. (2006). Pathogen-sensing plasmacytoid dendritic cells stimulate cytotoxic T-cell function in the atherosclerotic plaque through interferon-alpha. Circulation 114, 2482–2489 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.642801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niessner A., Weyand C. M. (2010). Dendritic cells in atherosclerotic disease. Clin. Immunol. 134, 25–32 10.1016/j.clim.2009.05.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilsson J., Nordin Fredrikson G., Schiopu A., Shah P. K., Jansson B., Carlsson R. (2007). Oxidized LDL antibodies in treatment and risk assessment of atherosclerosis and associated cardiovascular disease. Curr. Pharm. Des. 13, 1021–1030 10.2174/138161207780487557 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oderup C., Cederbom L., Makowska A., Cilio C. M., Ivars F. (2006). Cytotoxic T lymphocyte antigen-4-dependent down-modulation of costimulatory molecules on dendritic cells in CD4+ CD25+ regulatory T-cell-mediated suppression. Immunology 118, 240–249 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2006.02362.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onishi Y., Fehervari Z., Yamaguchi T., Sakaguchi S. (2008). Foxp3+ natural regulatory T cells preferentially form aggregates on dendritic cells in vitro and actively inhibit their maturation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 10113–10118 10.1073/pnas.0711106105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onodera T., Jang M. H., Guo Z., Yamasaki M., Hirata T., Bai Z., et al. (2009). Constitutive expression of IDO by dendritic cells of mesenteric lymph nodes: functional involvement of the CTLA-4/B7 and CCL22/CCR4 interactions. J. Immunol. 183, 5608–5614 10.4049/jimmunol.0804116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palinski W., Miller E., Witztum J. L. (1995). Immunization of low density lipoprotein (LDL) receptor-deficient rabbits with homologous malondialdehyde-modified LDL reduces atherogenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 92, 821–825 10.1073/pnas.92.3.821 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palucka K., Banchereau J. (2012). Cancer immunotherapy via dendritic cells. Nat. Rev. Cancer 12, 265–277 10.1038/nrc3258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paulson K. E., Zhu S. N., Chen M., Nurmohamed S., Jongstra-Bilen J., Cybulsky M. I. (2010). Resident intimal dendritic cells accumulate lipid and contribute to the initiation of atherosclerosis. Circ. Res. 106, 383–390 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.210781 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peluso I., Morabito G., Urban L., Ioannone F., Serafini M. (2012). Oxidative stress in atherosclerosis development: the central role of LDL and oxidative burst. Endocr. Metab. Immune Disord. Drug. Targets 12, 351–360 10.2174/187153012803832602 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrin-Cocon L., Coutant F., Agaugué S., Deforges S., André P., Lotteau V. (2001). Oxidized low-density lipoprotein promotes mature dendritic cell transition from differentiating monocyte. J. Immunol. 167, 3785–3791 10.4049/jimmunol.167.7.3785 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrin-Cocon L., Diaz O., André P., Lotteau V. (2013). Modified lipoproteins provide lipids that modulate dendritic cell immune function. Biochimie 95, 103–108 10.1016/j.biochi.2012.08.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierides C., Bermudez-Fajardo A., Fredrikson G. N., Nilsson J., Oviedo-Orta E. (2013). Immune responses elicited by apoB-100-derived peptides in mice. Immunol. Res. 56, 96–108 10.1007/s12026-013-8383-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Randolph G. J., Beaulieu S., Lebecque S., Steinman R. M., Muller W. A. (1998). Differentiation of monocytes into dendritic cells in a model of transendothelial trafficking. Science 282, 480–483 10.1126/science.282.5388.480 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers L., Burchat S., Gage J., Hasu M., Thabet M., Willcox L., et al. (2008). Deficiency of invariant V alpha 14 natural killer T cells decreases atherosclerosis in LDL receptor null mice. Cardiovasc. Res. 78, 167–174 10.1093/cvr/cvn005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shortman K., Naik S. H. (2007). Steady-state and inflammatory dendritic-cell development. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 7, 19–30 10.1038/nri1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorg R. V., Kögler G., Wernet P. (1999). Identification of cord blood dendritic cells as an immature CD11c- population. Blood 93, 2302–2307 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinman R. M., Banchereau J. (2007). Taking dendritic cells into medicine. Nature 449, 419–426 10.1038/nature06175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinman R. M., Cohn Z. A. (1973). Identification of a novel cell type in peripheral lymphoid organs of mice. I. Morphology, quantitation, tissue distribution. J. Exp. Med. 137, 1142–1162 10.1084/jem.137.5.1142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinman R. M., Hawiger D., Nussenzweig M. C. (2003). Tolerogenic dendritic cells. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 21, 685–711 10.1146/annurev.immunol.21.120601.141040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stemme S., Faber B., Holm J., Wiklund O., Witztum J. L., Hansson G. K. (1995). T lymphocytes from human atherosclerotic plaques recognize oxidized low density lipoprotein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 92, 3893–3897 10.1073/pnas.92.9.3893 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephens T. A., Nikoopour E., Rider B. J., Leon-Ponte M., Chau T. A., Mikolajczak S., et al. (2008). Dendritic cell differentiation induced by a self-peptide derived from apolipoprotein E. J. Immunol. 181, 6859–6871 10.4049/jimmunol.181.10.6859 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subramanian M., Tabas I. (2014). Dendritic cells in atherosclerosis. Semin. Immunopathol. 36, 93–102 10.1007/s00281-013-0400-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeda M., Yamashita T., Sasaki N., Hirata K. I. (2012). Dendritic cells in atherogenesis: possible novel targets for prevention of Atherosclerosis. J. Atheroscler. Thromb. 19, 953–961 10.5551/jat.14134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuttolomondo A., Di Raimondo D., Pecoraro R., Arnao V., Pinto A., Licata G. (2012). Atherosclerosis as an inflammatory disease. Curr. Pharm. Des. 18, 4266–4288 10.2174/138161212802481237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Brussel I., Lee W. P., Rombouts M., Nuyts A. H., Heylen M., De Winter B. Y., et al. (2014). Tolerogenic dendritic cell vaccines to treat autoimmune diseases: can the unattainable dream turn into reality? Autoimmun. Rev. 13, 138–150 10.1016/j.autrev.2013.09.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Brussel I., Schrijvers D. M., Van Vré E. A., Bult H. (2013). Potential use of dendritic cells for anti-atherosclerotic therapy. Curr. Pharm. Des. 19, 5873–5882 10.2174/1381612811319330006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VanderLaan P. A., Reardon C. A., Sagiv Y., Blachowicz L., Lukens J., Nissenbaum M., et al. (2007). Characterization of the natural killer T-cell response in an adoptive transfer model of atherosclerosis. Am. J. Pathol. 170, 1100–1107 10.2353/ajpath.2007.060188 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Es T., van Puijvelde G. H., Foks A. C., Habets K. L., Bot I., Gilboa E., et al. (2010). Vaccination against Foxp3(+) regulatory T cells aggravates atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis 209, 74–80 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2009.08.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Leeuwen M., Damoiseaux J., Duijvestijn A., Tervaert J. W. (2009). The therapeutic potential of targeting B cells and anti-oxLDL antibodies in atherosclerosis. Autoimmun. Rev. 9, 53–57 10.1016/j.autrev.2009.03.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Puijvelde G. H., Hauer A. D., de Vos P., van den Heuvel R., van Herwijnen M. J., van der Zee R., et al. (2006). Induction of oral tolerance to oxidized low-density lipoprotein ameliorates atherosclerosis. Circulation 114, 1968–1976 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.615609 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Vré E. A., Van Brussel I., Bosmans J. M., Vrints C. J., Bult H. (2011). Dendritic cells in human atherosclerosis: from circulation to atherosclerotic plaques. Mediators Inflamm. 2011, 941396 10.1155/2011/941396 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villadangos J. A., Young L. (2008). Antigen-presentation properties of plasmacytoid dendritic cells. Immunity 29, 352–361 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.09.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber C., Meiler S., Döring Y., Koch M., Drechsler M., Megens R. T., et al. (2011). CCL17-expressing dendritic cells drive atherosclerosis by restraining regulatory T cell homeostasis in mice. J. Clin. Invest. 121, 2898–2910 10.1172/JCI44925 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamanaka R., Kajiwara K. (2012). Dendritic cell vaccines. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 746, 187–200 10.1007/978-1-4614-3146-6_15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yilmaz A., Lochno M., Traeg F., Cicha I., Reiss C., Stumpf C., et al. (2004). Emergence of dendritic cells in rupture-prone regions of vulnerable carotid plaques. Atherosclerosis 176, 101–110 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2004.04.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yilmaz A., Weber J., Cicha I., Stumpf C., Klein M., Raithel D., et al. (2006). Decrease in circulating myeloid dendritic cell precursors in coronary artery disease. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 48, 70–80 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.01.078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou X., Robertson A. K., Hjerpe C., Hansson G. K. (2006). Adoptive transfer of CD4+ T cells reactive to modified low-density lipoprotein aggravates atherosclerosis. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 26, 864–870 10.1161/01.ATV.0000206122.61591.ff [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]