Abstract

Alcohol problems are one of the most well-established risk factors for physical intimate partner violence. Nonetheless most individuals who drink heavily do so without ever aggressing against a partner. Laboratory research identifies hostility as an important moderator of the association between alcohol and general aggression, and correlational research suggests stress and coping may also be important moderators of the alcohol-aggression link. Building on this research, the present study examines hostility, coping, and daily hassles as moderators of the associations between excessive drinking and intimate partner violence across the first four years of marriage in a sample of 634 newly married couples. Excessive drinking was a significant cross-sectional correlate, but did not emerge as a unique longitudinal predictor of intimate partner violence perpetration in this sample. However, alcohol was longitudinally predictive of husband violence among hostile men with high levels of avoidance coping. Findings generally supported the moderation model, particularly for men. These findings implicate hostility, coping, and daily hassles, as well as alcohol, as potentially important targets for partner violence prevention strategies for young married couples.

Keywords: intimate partner violence, alcohol, coping, hostility

In a given year, approximately 12% of married or cohabiting men in the U. S. engage in one or more acts of physical intimate partner violence (IPV) (Straus & Gelles, 1990). Importantly, the prevalence of IPV engaged in by women is comparable to and often exceeds the prevalence male-perpetrated IPV. For example, Caetano, McGrath, Ramisetty-Mikler, and Field (2005) found a prevalence of 10% for male-to-female IPV and 12% for female-to-male IPV in a nationally representative sample. Among younger adults who have been more recently married, the rates are two to three times higher (Schumacher & Leonard, 2005).

Studies of risk factors for IPV perpetration have found that patterns of heavy drinking and alcohol use disorders are among the most robust risk factors for men's IPV (see Leonard, 1993). The relationship between men's drinking and the occurrence, frequency, or severity of IPV has been found in nationally representative samples (e.g., Kantor & Straus, 1987), community samples (e.g., Leonard & Senchak, 1996), substance abuse treatment samples (e.g., Murphy & O'Farrell, 1994), and domestic violence treatment samples (e.g., Stuart et al., 2006). Whereas men's drinking patterns have been strongly linked to IPV perpetration, the literature with respect to women's drinking patterns and IPV perpetration is less clear. Stuart et al. (2006) studied individuals arrested for IPV and found that women's alcohol problems were associated with their frequency of engagement in IPV. Drinking has been found to be associated with women's violent behavior toward their husbands in non-treatment samples (e.g., Schafer, Caetano, and Cunradi, 2004) , although there have also been community studies that have failed to find a relationship between women's drinking and their own IPV behavior controlling for men's drinking (Leonard & Senchak 1996).

Notwithstanding the uncertain nature of the alcohol/aggression relationship for women, it is important to note that most men and women who drink heavily do so without ever aggressing against a romantic partner (Kantor & Straus, 1987). Within alcohol treatment samples, as many as 50% of more of men have not engaged in recent physical partner aggression (Schumacher, Fals-Stewart, & Leonard, 2003), and many men who sometimes aggress after heavy drinking do not do so after all heavy drinking occasions (Fals-Stewart, 2003). For both men and women, available evidence generally indicates that alcohol is neither a necessary nor sufficient cause of IPV. Rather alcohol appears to be associated with IPV only for certain individuals. Unfortunately, only a handful of studies have examined moderators of the alcohol/IPV relationship (and these uniformly focus on men's drinking and male-to-female violence). Lipsey, Wilson, Cohen, and Derzon (1997), speaking to this issue with respect to alcohol and violence more generally referred to the lack of research into moderating factors as “the greatest failure of the research” (p. 280).

Current theoretical approaches to alcohol and violence provide a rationale for assessing several potential moderators. Alcohol Myopia (Steele & Josephs, 1990) and related models (e.g., Pernanen, 1976; Taylor & Leonard, 1983) focus on the cognitively impairing effects of alcohol on processes that, under normal circumstances, might regulate and control aggressive responding (e.g., likelihood of attending to potential inhibitory cues, recall of appropriate normative behavior, recognition of alternate strategies, and evaluation of potential consequences). From this perspective, alcohol weakens cognitive controls and allows for dominant cues and dominant response options to have a stronger influence on behavior. Accordingly, alcohol should have a more pronounced effect on individuals with aggressive perceptual and behavioral propensities, and among individuals, who for dispositional or situational reasons, already have some degree of impaired behavioral regulation and control.

There are a number of experimental studies suggesting that high levels of hostility and anger interact with alcohol to predict aggressive behavior in laboratory aggression paradigms. Bailey and Taylor (1991) found that alcohol facilitated aggressive behavior among men who were moderate to high in hostility, but not among low hostile men. Similar findings are reported for anger (Giancola Saucier & Gussler-Burkhardt, 2003) and antisocial personality disorder (Moeller, Dougherty, Lane, Steinberg & Cherek, 1998). There is also a considerable body of research linking anger and hostility to intimate partner violence (e.g., Norlander & Eckhardt, 2005), and the few studies specifically focused on moderators of the alcohol/IPV relationship provide supportive evidence for a focus on hostility and related constructs. In survey research, Leonard and Blane (1992) found that heavy drinking was associated with marital violence among hostile men, but not among non-hostile men. Jacob, Leonard, and Haber (2001) found that among couples with a husband who had an alcohol use disorder, alcohol increased negativity only among couples in which the husband was also antisocial. At the daily level, Fals-Stewart, Leonard, and Birchler (2005) found that alcohol use on a specific day increased the probability that severe aggression would also occur on that day, and that this effect was the strongest for men with an antisocial personality disorder. Finally, Eckhardt (2007) found that alcohol administration to maritally aggressive men resulted in increased aggressive verbal statements only among men who were also high in anger.

In contrast to the research focused on hostility, research focused on stress and coping as moderators of the alcohol-IPV relationship is less well developed. However, there is a growing literature linking these factors to increased aggressive behavior, and suggesting they may moderate they association between alcohol and aggression. Research has suggested that stressful life events are associated with violent behavior in general (Silver & Teasdale, 2005) and IPV in particular (Cano & Vivian, 2001). Moreover, Margolin, John, and Foo (1998) found that alcohol impairment was predictive of male IPV among the men who had experienced more negative life events, but not among men with fewer negative life events. Research also suggests that individuals who use ineffective coping strategies to manage stressors are more likely to engage in aggressive behavior. For example, in a study of 3,367 individuals with substance abuse problems, McCormick and Smith (1995) found that individuals scoring high on aggression and hostility reported using escape-avoidance, distancing, and confrontational coping styles more regularly than those who were low in aggression and hostility. With respect to IPV, Gryl, Stith, and Bird (1991) found that among male and female college students in serious dating relationships, those in violent relationships reported greater use of confrontation and escape/avoidance as coping strategies. This association has also been demonstrated in adult treatment samples. Snow, Sullivan, Swan, Tate, and Klein (2006) examined coping styles as a predictor of the frequency of physical and psychological abuse among men who were court mandated to a program for domestic violence offenders. In a path analysis, avoidance coping was associated with both physical and psychological abuse, as was the men's problem drinking.

The present study builds on this body of research, by examining excessive drinking and IPV in a large ongoing longitudinal study of couples. Based on current theoretical approaches to intoxicated behavior, we hypothesized that the relationship between excessive drinking and IPV would be moderated by aggressive proclivities, poor coping, and stress. This hypothesis was tested with respect to both husband-to-wife IPV and wife-to-husband IPV.

Method

Participants

Participants for this report were involved in a longitudinal study of marriage and alcohol involvement. All participants were at least 18 years old, spoke English, and were literate. Couples were ineligible for the study if they had been previously married. These analyses are based on 634 couples. At the initial assessment, the average age of the men [mean (SD)] was 28.7 (6.3) years and the average age of the women was 26.8 (5.8) years. The majority of the men and women in the sample were European American (husbands: 59%; wives: 62%). About one-third of the sample was African American (husbands: 33%; wives: 31%). The sample also included small percentages (less than 5%) of Hispanic, Asian, and Native American participants. A large proportion of husbands and wives had at least some college education (husbands: 64%; wives: 69%) and most were employed at least part-time (husbands: 89%; wives 75%). Consistent with other studies of newly married couples (e.g. Chadiha, Veroff, & Leber, 1998), many of the couples were parents at the time of marriage (38% of the husbands and 43% of the wives) and were living together prior to marriage (70%). The Institutional Review Board of the State University of New York at Buffalo approved the research protocol.

Procedures

After applying for a marriage license, couples were recruited for a 5-10 minute paid ($10) interview. The interview covered demographic factors (e.g. race, education, age), family and relationship factors (e.g. number of children, length of engagement), and substance use questions (e.g. tobacco use, average alcohol consumption, times intoxicated in the past year). Recruitment occurred over a 3-year period from 1996-1999. For interested individuals who did not have time to complete this interview, a telephone interview was conducted later that day or the next day (N = 62). Less than 8% of individuals approached declined to participate in this brief interview, and a total of 970 eligible couples were interviewed.

Complete details of the recruitment process can be found elsewhere (Homish & Leonard, 2006; Leonard & Mudar, 2003), but briefly, couples who agreed to participate in the longitudinal study were given identical questionnaires to complete at home and asked to return them in separate postage paid envelopes (Wave 1 Assessment). Participants were asked not to discuss their responses with their partners. Each spouse received $40 for his or her participation. Only 7% of eligible couples who completed the brief screening interview refused to participate in the longitudinal study. Those who agreed to participate in the longitudinal study, compared to those who did not, had lower incomes (p < .01) and the women were more likely to have children (p < .01). No other differences were identified. Of the 887 eligible couples who agreed to participate (13 of the original 900 did not marry); data were collected from both spouses for 634 couples (71.4%). The 634 couples are the basis for this report. Couples who returned the questionnaires were more likely to be living together compared to couples who did not return the questionnaires (70% vs. 62%; p < .05) and more likely to be European American. No other sociodemographic differences existed between the couples who responded compared to those who did not. Average past year alcohol consumption did not differ between couples who returned the questionnaires and those who did not. Husbands in non-respondent couples consumed 6 or more drinks or were intoxicated in the past year more often than husbands who completed the questionnaire; however, these differences were small.

At the couples' first, second, and fourth wedding anniversaries (Waves 2, 3 and 4), they were mailed questionnaires similar to those they received at the first assessments. Waves 5 (7th anniversary) and 6 (9th anniversary) are currently being completed. As with the first assessment, participants were asked to complete the questionnaires and return them in the postage paid envelopes. Each spouse received $40 for his or her participation for assessments 2 and 3 and $50 for the fourth assessment. At the fourth assessment, 71.1% (N= 451) of the original sample of husbands completed the questionnaires. Husbands who did not participate in the fourth assessment did not differ from other husbands with regard to husband-to-wife or wife-to-husband aggression, excessive alcohol use (score on the alcohol dependence scale), daily hassles, or hostility. Husbands who completed the fourth assessment were more likely to use avoidance coping at the first assessment [mean (standard deviation) of avoidance coping= 2.1 (.58) compared to 1.9 (.54), respectively, p < .05]. At the fourth assessment, 80.4% (N= 510) of women completed the questionnaire. Wives who did not complete the fourth assessment did not differ from others wives in terms of time 1 husband-to-wife or wife-to-husband aggression, alcohol, daily hassles, or hostility.

Measures: Outcome Variable

Physical aggression

The physical assault subscale of the Conflict Tactics Scale – Revised (CTS-2; Straus, Hamby, Boney-McCoy, & Sugarman, 1996) was used to assess partner physical aggression. Respondents were asked the number of times in the past year that they and their partners engaged in a number of physically aggressive behaviors during a disagreement. To control for the under reporting of violence, a combined score representing the maximum of self-report and partner report of aggression served as the measure of physical aggression for both husbands and wives. Reliability estimates (Cronbach's alpha) for the CTS-2 ranged from 0.86 to 0.94 across husband and wife reports of their own and their partner's aggression over the four waves.

Measures: Predictor Variables

Hostility

Hostility was based on 10 items rated on a 4-point scale ranging from 0 to 3 with a possible total score ranging from 0 to 30. Example items included “I was argumentative with people,” “I had a hard time controlling my temper,” and “I did not feel angry or mad” (reverse coded). Coefficient alphas ranged from 0.82 to 0.87 across the four waves. Hostility was estimated as a lagged, time-varying predictor in the models.

Life stress

Daily stressors or “hassles” were measured using the short form of the Survey of Recent Life Experiences scale (Kohn & MacDonald, 1992). This 41-item measure asks participants to indicate the extent to which each “hassle” characterizes their daily experiences, using a 4-point scale (1 = not at all a part of my life, 4 = very much part of my life). This measure represents an improvement over other “hassles” measures because its items are “decontaminated” (free of reference to feelings of distress). Coefficient alphas ranged from 0.92 to 0.94 across the four waves. Daily hassles were estimated as a lagged, time-varying predictor in the models.

Avoidance coping

Avoidance coping was assessed using the Coping with Stress Scale (CWSS; Rothbard, 1996). The CWSS is a 42-item measure of coping in response to stress. The measure includes nine a-priori subscales, each of which represents a conceptually distinct coping strategy: Task-Oriented Coping, Focusing on Emotions, Positive Reinterpretation, Distraction, Seeking Social Support, Denial, Exercise, Wishful Thinking, and Alcohol Disengagement. Each of the subscales has demonstrated good internal consistency (Rothbard, 1996). For the current study, a measure of avoidance coping was created by averaging participants' responses to the items from three of the subscales; wishful thinking, distraction, and denial. Although Alcohol Disengagement is also an Avoidance Coping strategy, we omitted this scale to avoid conceptual overlap with excessive drinking. Using a scale ranging from 1 (I don't do this at all) to 4 (I do this a lot); participants indicated the extent to which they generally engage in each behavior in response to stressful life events. Cronbach's alpha for husbands and wives ranged from 0.82 to 0.88 across the four assessments. Avoidance coping was estimated as a time-varying predictor in the models.

Excessive drinking

The Alcohol Dependence Scale (ADS; Skinner & Allen, 1982; Skinner & Horn, 1984) was used to assess excessive alcohol use. The ADS is a 25-item measure that encompasses four key aspects of alcohol dependence syndrome: loss of behavioral control (e.g., blackouts, gulping drinks), psychoperceptual withdrawal symptoms (e.g., hallucinations), psychophysical withdrawal symptoms (e.g., hangovers, delirium tremens), and obsessive drinking style (e.g., sneaks drinks, always has a bottle at hand). According to Skinner and Allen (1982), a score of 1-13 represents a low level of alcohol dependence (first quartile), 14-21 an intermediate level (second quartile), 22-30 a substantial level (third quartile), and 31-47 a severe level (fourth quartile). In the current study, Cronbach's alpha for husbands and wives ranged from 0.81 to 0.89 across the four assessments. The ADS score was estimated as a lagged, time-varying predictor in the models.

Demographic factors

At the initial in-person interview, each spouse reported their age, race/ethnicity, income, highest level of education obtained, employment status, if they had children prior to the current marriage, and the number of months cohabitating. These variables were modeled as time invariant covariates in the regression model.

Analysis

Descriptive statistics were assembled to characterize the outcome variables for husbands and wives at each wave. Correlations were used to assess the relation between husband-to-wife and wife-to-husband physical aggression at each wave. To identify predictors of aggression over time, we used Generalized Estimating Equations (GEE) (Zeger & Liang, 1986; Zeger, Liang, & Albert, 1988). GEE models are used to analyze data from longitudinal designs with discrete or continuous outcomes (Homish & Leonard, 2007; Zeger et al., 1988). Because longitudinal datasets contain repeated observations of the same participants over time, the data is often correlated; thus requiring more specialized analytic tools. GEE models can be used to assess the longitudinal relationship between several time-varying and time-invariant predictors and the outcome variable (Twisk, 2004). In addition to appropriately handling correlated data structures, GEE models are also useful for dealing with cases with missing observations. For many other analyses (e.g., repeated measures ANOVA's), participants who do not provide data for each assessment are considered missing; however; GEE modeling allows participants with only information from one assessment to be included in the analyses (Twisk, 2004). The nature of the missing data, however, should be missing at random.

For the current report, two GEE models were analyzed. The outcome for the first model was wife-to-husband aggression and the outcome for the second model was husband-to-wife aggression. All models were analyzed with Stata (Version 8, StataCorp, 2003). Because the outcome variables are a count variable (i.e., how often physical aggression occurred), a Poisson family can be specified within the GEE models. However, Poisson models have somewhat restrictive assumptions that can be easily violated resulting in misleading results (Gardner, Mulvey, & Shaw, 1995). For example, when the observed variance exceeds the predicted mean, overdispersion results, thus violating one of the assumptions for Poisson models (Wu, 2005). In these situations, a negative binomial family is a more appropriate choice (Byers, Allore, Gill, & Peduzzi, 2003; Gardner et al., 1995). The GEE models for the current report were estimated with a Negative Binomial Family and Log Link. In addition, an autoregressive correlation structure with a lag of 1 was specified along with robust standard errors. The robust standard errors are used so that if the nature of the correlation structure is not correctly specified, the standard errors will still be valid (StataCorp, 2003). Risk Ratios are reported for all models. Risk ratios greater than 1 represent an increased risk while risk ratios less than 1 represent decreased risk. Risk ratios equal to 1 reflect no significant increase or decrease in risk. Unlike interactions in regression analyses in which the estimated values of the criterion variable (aggression) can be calculated for specific values of the predictor variables, GEE requires the calculation of risk of aggression based on groups scoring high and low on the predictor variables. The choice of the cut points for these groups is to some degree arbitrary. When possible, we utilized cut points of 1 standard deviation above and below the mean. However, in examining three way interactions, these cut points created empty cells. As a result, we explored the three way interactions by forming groups based on median splits for two of the variables, and by using the 1 SD cutoff for the alcohol variable.

Results

Descriptive statistics were used to characterize the two outcome variables of interest, husband-to-wife aggression and wife-to-husband aggression. At the first assessment, the prevalence of any husband-to-wife aggression was 37.4% and the prevalence of wife-to-husband aggression was 48.1% (Table 1). Across the four assessments, the annual prevalence of any injury gradually decreased from 18% to 10% for wives and from 15% to 9% for husbands. The prevalence of husband-to-wife aggression remained fairly stable until decreasing at the fourth wedding anniversary. Wife-to-husband aggression exhibited gradual declines at each assessment with the largest decrease occurring between the second and fourth anniversaries. Across the 4 assessments, 42% of husbands and 34% of wives did not ever engage in violence. The percentage of husbands who were violent at one, two, three, and all four assessments was 16%, 16%, 14%, and 12%, respectively. The percentage of wives who were violent at one, two, three, and all four assessments was 17%, 17%, 16%, and 17%, respectively. Cross-sectional correlations between the predictors within each wave and intimate partner violence within the same wave are presented in Table 2. Husband-to-wife and wife-to-husband aggression were significantly correlated at all Waves. With the exception of wives' scores on the Alcohol Dependence Scale at Wave 1 and wives' avoidance coping at Wave 3, all of the husband and wife predictors (hostility, daily hassles, avoidance coping, and ADS) were significantly associated with both husband-to-wife as well as wife-to-husband violence at each assessment.

Table 1. Descriptive Statistics (Percent/(N) or Mean/(SD)].

| Wave 1 | Wave 2 | Wave 3 | Wave 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prevalence of husband-to-wife aggression | 37.4% | 38.2% | 37.2% | 25.5% |

| (237) | (222) | (204) | (131) | |

| Prevalence of wife-to-husband aggression | 48.1% | 45.3% | 41.4% | 33.9% |

| (305) | (263) | (227) | (174) | |

| H Hostility | 1.6 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 1.6 |

| (0.5) | (0.5) | (0.5) | (0.5) | |

| W Hostility | 1.7 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 1.6 |

| (0.5) | (0.6) | (0.6) | (0.5) | |

| H Daily Hassles | 1.8 | 1.7 | 1.7 | 1.7 |

| (0.5) | (0.4) | (0.4) | (0.4) | |

| W Daily Hassles | 1.9 | 1.8 | 1.8 | 1.8 |

| (0.4) | (0.4) | (0.4) | (0.5) | |

| H Avoidance Coping | 2.0 | 1.9 | 1.9 | 1.9 |

| (0.6) | (0.6) | (0.6) | (0.6) | |

| W Avoidance Coping | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 1.9 |

| (0.5) | (0.6) | (0.5) | (0.6) | |

| H ADS | 3.3 | 2.9 | 2.3 | 2.5 |

| (4.2) | (4.4) | (3.9) | 4.2) | |

| W ADS | 2.5. | 2.0 | 2.0 | 1.7 |

| (3.4) | (3.3) | (3.3) | (3.6) | |

|

| ||||

| N | 634 | 581 | 548 | 513 |

Table 2. Correlations between predictors within each wave and intimate partner violence within the same wave.

| Wave 1 | Wave 2 | Wave 3 | Wave 4 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| H-W IPV | W-H IPV | H-W IPV | W-H IPV | H-W IPV | W-H IPV | H-W IPV | W-H IPV | |

| W-H IPV | .64*** | .58*** | .52*** | .62*** | ||||

| H Hostility | .30*** | .21*** | .26*** | .29*** | .21*** | .28*** | .27*** | .29*** |

| W Hostility | .19*** | .24*** | .26*** | .27*** | .34*** | .33*** | .30*** | .26*** |

| H Daily hassles | .23*** | .22*** | .27*** | .32*** | .20*** | .24*** | .27*** | .28*** |

| W Daily hassles | .21*** | .25*** | .28*** | .35*** | .28*** | .18*** | .29*** | .26*** |

| H Avoidance coping | .17*** | .20*** | .12** | .16*** | .12** | .19*** | .15*** | .21*** |

| W Avoidance coping | .14*** | .15*** | .08* | .12** | .05 | .08+ | .14** | .09* |

| H Alcohol | .12* | .17*** | .29*** | .33*** | .18*** | .22*** | .28*** | .22*** |

| W Alcohol | .04 | .07^ | .11* | .15*** | .13** | .11* | .27*** | .10* |

Note. H = Husband; W = Wife, H-W = Husband-to-Wife, W-H = Wife=to-Husband, IPV = Intimate Partner Violence, Alcohol = Alcohol Dependence Scale Score,

p< .001;

p < .01,

p < .05;

p < .06,

p <.10

Predicting Husband-to-Wife Aggression

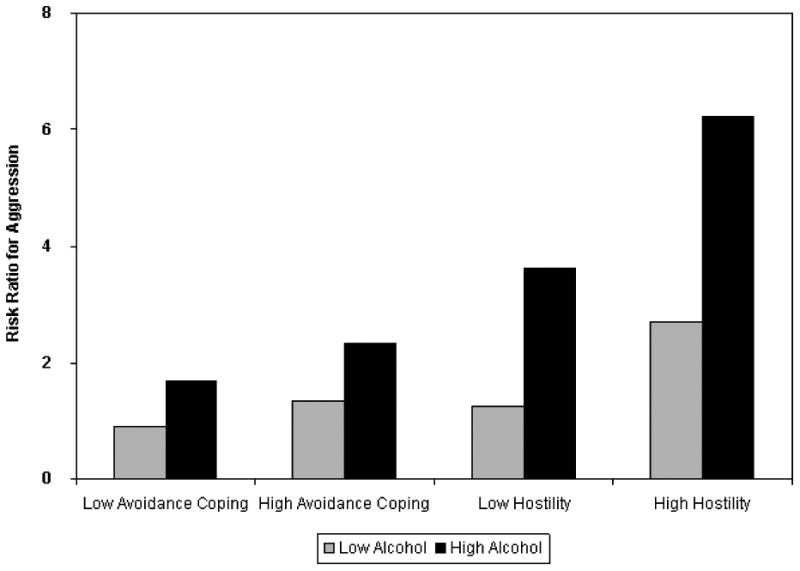

The first GEE model was used to examine individual and partner factors that related to husband-to-wife aggression over the first four years of marriage. In addition to considering the main effects of the individuals' hostility, daily hassles, avoidance coping, and alcohol, interactive effects of these predictors were also modeled. The impact of these individual and partner effects was examined after considering the impact of time and wives' sociodemographic variables. Results from the main effects model are presented first followed by the results from the full model including the two- and three-way interactions (see Table 3). In the main effects model predicting husband-to-wife aggression, the effect of time was significant (Risk Ratio [RR] = 0.85; 95% Confidence Interval [95% CI]: 0.78, 0.93; p < .001). This protective risk ratio for the variable time means that for each year of observation, there is a 15% reduction in the risk for husband-to-wife aggression after considering the effects of the other variables in the model. In terms of individual level risk factors, hostility and avoidance coping were both significant in the main effects model with increases in each related to a greater likelihood of aggression (hostility RR = 1.33; 95% CI: 1.01, 1.77; p < .05; avoidance coping RR = 1.82; 95% CI: 1.27, 2.62; p < .05). One partner risk factor, wives' hostility, was significant in the main effects model (RR = 1.76; 95% CI: 1.31, 2.35; p < .001). In the full model, the two husband main effects become non-significant; however, two predicted significant interactions emerged. Husband's hostility interacted with avoidance coping to predict aggression such that hostility in the presence of avoidance coping was associated with more husband-to-wife aggression (RR=1.32; 95% CI: 1.12, 1.54; p < .01). However, there was also a significant three-way interaction for avoidance coping, hostility, and alcohol (RR=0.95; 95% CI: 0.92, 0.99; p < .05). Because of the strong positive skew of the Alcohol Dependence Scale, one standard deviation below the mean was a value lower than the minimum value of the scale, which was zero. As a result, the low group was defined as those who scored the minimum on the ADS. We formed the high group using a cutoff that was approximately equidistant from the mean as was zero, which was 6 or above. As noted above, groups based on hostility and avoidance coping were formed using a median split to avoid the occurrence of empty or very small cells. According to this interaction, which is depicted in Figure 1, the effect of alcohol was most pronounced among men who were high on both hostility and avoidance coping. In the full model, wives' hostility remained significantly associated with husband-to-wife aggression with greater levels of wives' hostility positively associated with aggression (RR=1.51; 95% CI: 1.19, 1.91; p < .01). Wives' alcohol problems were not, however, significantly predictive of husband's IPV perpetration.

Table 3. Factors predicting husband-to-wife aggression.

| Main Effects Model | Full Model | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||

| Risk Ratio | Standard Error | 95% CI | Risk Ratio | Standard Error | 95% CI | |

|

|

||||||

| Time | 0.85*** | 0.04 | 0.78, 0.93 | 0.90* | 0.04 | 0.82, 0.99 |

| H Covariates | ||||||

| Age | 0.95* | 0.02 | 0.92, 0.99 | 0.96* | 0.02 | 0.92, 0.99 |

| Parent prior to marriage | 1.50 | 0.29 | 0.99, 2.16 | 1.51* | 0.31 | 1.01, 2.25 |

| Months cohabiting prior to marriage | 1.00 | 0.00 | 1.00, 1.01 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 1.00, 1.01 |

| Education | 0.62* | 0.11 | 0.43, 0.89 | 0.75 | 0.15 | 0.51, 1.11 |

| Race/ethnicity | 0.56* | 0.10 | 0.39, 0.81 | 0.57** | 0.11 | 0.39, 0.84 |

| Employment | 1.20 | 0.18 | 0.89, 1.61 | 1.10 | 0.17 | 0.81, 1.50 |

| Partner Factors | ||||||

| Lagged W Hostility | 1.76*** | 0.26 | 1.31, 2.35 | 1.51** | 0.18 | 1.19, 1.91 |

| Lagged W ADS | 1.02 | 0.02 | 0.98, 1.05 | 1.02 | 0.02 | 0.99, 1.06 |

| Individual Factors | ||||||

| Lagged H Hostility | 1.33* | 0.19 | 1.01, 1.77 | 1.18 | 0.14 | 0.94, 1.48 |

| Lagged H Daily Hassles | 1.15 | 0.29 | 0.70, 1.89 | 1.16 | 0.27 | 0.74, 1.81 |

| Lagged H Coping | 1.82** | 0.34 | 1.27, 2.62 | 0.64 | 0.16 | 0.39, 1.06 |

| Lagged H ADS | 0.98 | 0.02 | 0.95, 1.02 | 0.98 | 0.01 | 0.96, 1.01 |

| Interaction Effects | ||||||

| H Coping × daily hassles | 1.08 | 0.14 | 0.84, 1.39 | |||

| H ADS × daily hassles | 0.99 | 0.04 | 0.91, 1.07 | |||

| H Coping × hostility | 1.32** | 0.011 | 1.12, 1.54 | |||

| H ADS × hostility | 1.03 | 0.02 | 0.99, 1.07 | |||

| H ADS × coping | 1.05 | 0.05 | 0.97, 1.15 | |||

| H ADS × H coping × hostility | 0.95* | 0.02 | 0.92, 0.99 | |||

| H Daily hassles × ADS × hostility | 1.03 | 0.02 | 0.99, 1.07 | |||

Note: H = Husband; W = Wife; ADS = Alcohol Dependence Scale. Italicized variables are lagged, time varying predictors.

p< .001;

p< .01;

p< .05

Figure 1. Husband Risk of Aggression as a Function of Hostility, Avoidance Coping, and Alcohol.

Predicting Wife-to-Husband Aggression

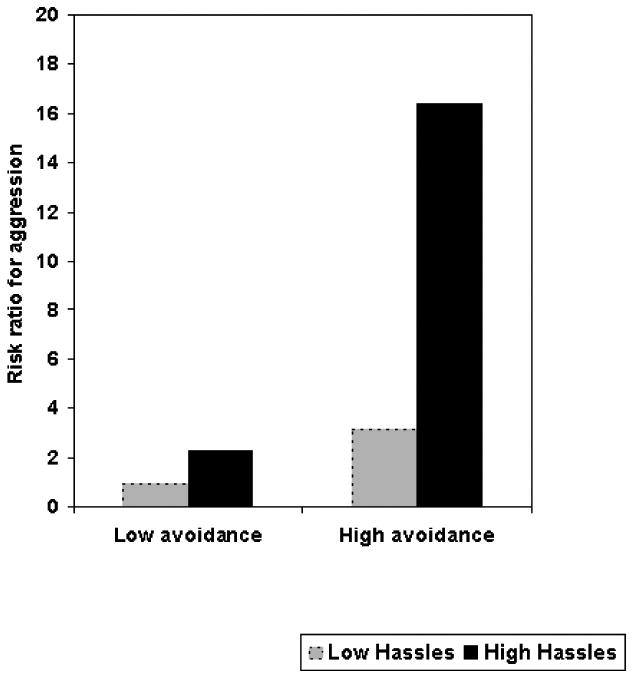

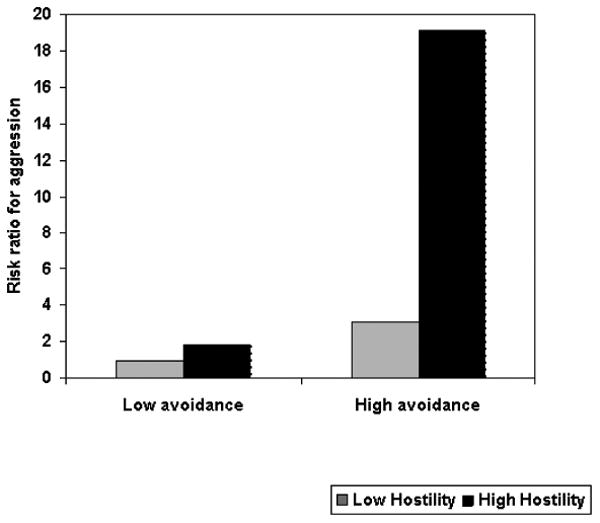

A second, parallel GEE model was used to examine the main and interactive effects of wife hostility, daily hassles, avoidance coping, and alcohol, controlling for time, wife sociodemographic variables, and partner effects on wife-to-husband aggression. The main effects model and the full model are presented in Table 4. Two individual risk factors were significant in the main effects model. There were significant positive associations between wives' daily hassles and wives' aggression (RR = 1.61; 95% CI: 1.11, 2.33; p < .05; Table 4), and wives' avoidance coping and wives' aggression (RR=1.53; 95% CI: 1.10, 2.13; p < .05). With regard to partner effects, husbands' hostility and ADS scores were positively associated with wives' aggression (hostility: RR=1.31; 95% CI: 0.99, 1.75; p < .06; ADS: RR= 1.05; 95% CI: 1.02, 1.08, p<.05). In the full model, there was a significant protective effect of time (RR=0.88; 95% CI: 0.78, .99; p < .05) with each year of observation resulting in a 12% reduction in risk for wife-to-husband aggression after controlling for the other variables in the model. Two significant two-way interactions emerged in the full model. The first interaction was between wives' avoidance coping and daily hassles and the second was between wives' avoidance coping and hostility. For the first interaction, daily hassles, in the presence of higher levels of avoidance coping, were significantly associated with a greater risk for wife-to-husband aggression (RR=1.31; 95% CI: 1.11, 1.55; p < .01. As can be seen in Figure 2, daily hassles were more strongly predictive of wife aggression among wives with high avoidance coping. Similarly, hostility in the presence of higher levels of avoidance coping was associated with increased risk for aggression (RR=1.29; 95% CI: 1.09, 1.51; p < .01). Similar to the previous interaction, the risk ratios were calculated for wives scoring one standard deviation above and below the mean for hostility and avoidance coping. This interaction, displayed in Figure 3, indicates that hostility was predictive of aggression among women high in avoidance coping. There was a marginal three-way interaction between avoidance coping, alcohol, and hostility that was similar to the interaction that emerged for husband aggression. Husbands' alcohol problems (as assessed by the score on the ADS) remained positively associated with an increased risk for wife-to-husband aggression (RR=1.05; 95% CI: 1.03, 1.08; p < .001) in the full model.

Table 4. Factors predicting wife-to-husband aggression.

| Main Effects Model | Full Model | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||

| Risk Ratio | Standard Error | 95% CI | Risk Ratio | Standard Error | 95% CI | |

|

|

||||||

| Time | 0.91 | 0.06 | 0.80, 1.04 | 0.88* | 0.06 | 0.78, 0.99 |

| W Covariates | ||||||

| Age | 0.96* | 0.02 | 0.92, 0.99 | 0.95* | 0.02 | 0.92, 0.99 |

| Parent prior to marriage | 1.33 | 0.26 | 0.92, 1.95 | 1.11 | 0.21 | 0.75, 1.63 |

| Months cohabiting prior to marriage | 1.00 | 0.00 | 1.00, 1.01 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 1.00, 1.01 |

| Education | 0.56* | 0.122 | 0.36, 0.86 | 0.63* | 0.13 | 0.42, 0.94 |

| Race/ethnicity | 0.70* | 0.12 | 0.50, 0.98 | 0.71̂ | 0.13 | 0.49, 1.00 |

| Employment | 1.23 | 0.14 | 0.99, 1.53 | 1.21 | 0.14 | 0.98, 1.51 |

| Partner Effects | ||||||

| Lagged H Hostility | 1.31÷ | 0.19 | 0.99, 1.75 | 1.17 | 0.15 | 0.91, 1.50 |

| Lagged H ADS | 1.05** | 0.01 | 1.02, 1.08 | 1.05*** | 0.01 | 1.03, 1.08 |

| Individual Factors | ||||||

| Lagged W Hostility | 1.29 | 0.21 | 0.94, 1.76 | 1.16 | 0.19 | 0.83, 1.61 |

| Lagged W Daily Hassles | 1.61* | 0.31 | 1.11, 2.33 | 1.36 | 0.29 | 0.89, 2.10 |

| Lagged W Coping | 1.53* | 0.26 | 1.10, 2.13 | 0.41*** | 0.09 | 0.27, 0.62 |

| Lagged W ADS | 0.97 | 0.02 | 0.94, 1.10 | 0.97 | 0.02 | 0.94, 1.01 |

| Interaction Effects | ||||||

| W Coping × daily hassles | 1.31** | 0.11 | 1.11, 1.55 | |||

| W ADS × daily hassles | 0.97 | 0.02 | 0.93, 1.03 | |||

| W Coping × hostility | 1.29** | 0.10 | 1.09, 1.51 | |||

| W ADS × hostility | 1.03 | 0.03 | 0.97, 1.10 | |||

| W ADS × coping | 1.02 | 0.02 | 0.98, 1.05 | |||

| W ADS × W coping × hostility | 0.97̂ | 0.01 | 0.95, 1.01 | |||

| Daily hassles × ADS × hostility | 1.02 | 0.02 | 0.98, 1.04 | |||

Note: H = Husband; W = Wife; ADS = Alcohol Dependence Scale. Italicized variables are lagged, time varying predictors.

p< .001;

p< .01;

p< .05;

I< .07

Figure 2. Wife Risk of Aggression as a Function of Daily Hassles and Avoidance Coping.

Figure 3. Wife Risk of Aggression as a Function of Hostility and Avoidance Coping.

Discussion

Excessive alcohol use and alcohol use disorders are among the most robust risk factors for male-to-female IPV in the literature (Schumacher et al., 2001). It is also clear in the literature however, that heavy drinking is neither a necessary nor sufficient precipitant of such aggression. Less research has examined the relationship between alcohol use and female-to-male IPV, but available evidence suggests problem drinking may not enhance risk for IPV perpetration to the same degree for women that it does for men. Although the experimental literature on alcohol use as a risk factor for aggression has long suggested that hostility and closely related constructs may moderate the relationship between problem drinking and IPV, these moderators have not been well-studied outside the laboratory setting. Similarly, although there is suggestion in correlational literature that stress and coping may moderate that association between alcohol and IPV, these potential moderators have received limited research attention.

The findings of this study build on prior research which indicates the association between alcohol use and violence by men may be moderated by aggressive propensities and coping deficiencies. Consistent with our hypotheses, in the final model, there was a significant two-way interaction between hostility and avoidance coping in the longitudinal prediction of male-to-female IPV over the first four years of marriage. Examination of this interaction revealed that greater hostility and greater reliance on avoidance coping strategies were associated with increased risk for IPV perpetration. Also consistent with our hypotheses, there was a three-way interaction among excessive alcohol consumption (as indexed by the Alcohol Dependence Scale), hostility, and avoidance coping Specifically, men with higher scores on the ADS were at greatest risk for IPV perpetration across the first four years of marriage if they were high in both avoidant coping and hostility. Contrary to our hypotheses, daily hassles, which we used as an index of stressful life events, were not a significant predictor of men's IPV perpetration.

In addition to being consistent with other findings in the correlational literature implicating coping deficits as a potential moderator of the association between alcohol use and aggression, the findings with regard to avoidance coping are also consistent with a growing body of experimental research which implicates deficits in self-regulation as important moderators of this association. In particular, executive cognitive function has been identified as an important moderator of the association between intoxication and aggression in laboratory paradigms, with those low in executive cognitive function displaying heightened aggression, and those high in executive cognitive function inhibiting aggression even while intoxicated (e.g., Giancola, 2004). Similarly, research suggests that the relationship between daily drinking and negative alcohol consequences, including aggression, is stronger among those low in self regulation (Neal & Carey, 2007). It is possible that non-adaptive responses to stressors may also be understood as increasing the likelihood of failures in self-regulation.

Although not examined as moderators, we also examined wives' hostility and ADS scores as predictors of men's IPV perpetration. In the final model, wife hostility was a significant predictor of men's partner violence perpetration. Although we cannot offer a definitive interpretation, the finding that wife hostility predicted violence perpetration but daily hassles did not, may suggest that for men wife hostility is experienced as a greater stressor and greater challenge to coping abilities than daily hassles. Wife ADS score was not a significant longitudinal predictor of men's IPV perpetration. As noted previously, a prior literature review identified 3 studies that found and 2 studies that failed to find an association between women's drinking or alcohol problems and victimization by a male partner (Schumacher, Feldbau-Kohn, Slep, & Heyman, 2001). Research with a sufficient number of heavy-drinking women is needed to examine this issue in a more statistically powerful manner.

With the exception of a few important differences, similar findings emerged with regard to prediction of female-to-male IPV. Significant avoidant coping × daily hassles and hostility interactions emerged, such that avoidant coping in the presence of either elevated hostility or daily hassles predicted women's violence perpetration. This may suggest that daily hassles are experienced as more stressful and present more of a challenge to coping abilities for wives than for husbands. Although only significant at the trend level (p = .07), the same excessive alcohol consumption × hostility × avoidant coping interaction detected for men also emerged for women. Taken together the findings for husbands' and wives' IPV suggest that within a community sample of couples in the early years of marriage, the longitudinal association between either partner's own alcohol consumption and their later IPV perpetration is moderated by dispositional variables. Importantly, for women, not only was partner hostility predictive of wives' violence perpetration, but men's excessive alcohol consumption was also predictive of wives' violence perpetration. Although it cannot be determined from this data whether alcohol was an immediate precipitant of violent conflicts, the finding is consistent with data suggesting that among couples in which the male partner has an alcohol problem, men's drinking is a frequent topic of conflict (Murphy, Winters, O'Farrell, Fals-Stewart, & Murphy, 2005).

Implications

IPV has long been identified as an important public health issue, because of its potential for serious mental and physical health consequences for victims (Coker et al., 2002). Although the consequences are more pronounced for female than male victims of IPV, there is evidence that perpetration of IPV in early marriage, increases women's risk for later victimization by their partners (Schumacher & Leonard, 2005). In addition to the health consequences associated with IPV, it has also been identified as a predictor of marital dissolution (Zlotnick, Johnson & Kohn, 2006). Identifying modifiable risk factors for IPV is important, in that these risk factors may become targets of secondary and tertiary prevention efforts.

Consistent with prior research (e.g., Kantor & Straus, 1987), men's excessive alcohol use was cross-sectionally correlated with both husbands' and wives' intimate partner perpetration at baseline. Moreover, at the later waves, the cross-sectional correlation between men's excessive alcohol use and IPV perpetration was moderately strong, ranging from .18 at Wave 3 to .29 at Wave 2. In contrast, wives excessive drinking was not a significant correlate of violence by either partner at baseline and only weakly correlated thereafter, with most correlations being less than .15. Perhaps one of the most interesting and important overall findings of this study is that a partner's own excessive alcohol use was a significant longitudinal predictor of IPV perpetration only for those with high hostility and high avoidance coping. For individuals without these characteristics, we did not observe a longitudinal effect of heavy drinking. Although these findings must be interpreted within the context of time lags, these findings raise some important questions about how extensively alcohol use per se should be viewed as a modifiable risk factor to target for IPV prevention efforts. Wives' excessive drinking was also not predictive of their own IPV victimization whereas husband's excessive drinking was predictive of wives' perpetration.

Collectively, our findings suggest that reducing alcohol use among individuals (particularly men) with high hostility and avoidance coping, individuals who might be similar to those who seek treatment for alcohol use disorders could reduce risk for future IPV. However, this may not hold true for non-treatment seeking individuals at lower levels of alcohol problem severity. As husbands' heavy drinking is a cross-sectional correlate and longitudinal predictor of wives' IPV these findings also suggest that men's heavy drinking may be an important target to reduce wife IPV. The findings also support prevention approaches such as the one proposed by Holtzworth-Munroe et al. (1995), which teach couples with deficient coping and aggressive propensities to manage conflict and their own emotions in ways that prevent escalations to physical aggression. In addition, our results support Holtzworth-Munroe et al.'s recommendation that to be most effective these programs must identify at risk couples prior to marriage. In the current study, over 1/3 of men and almost 1/2 of women in the sample had perpetrated IPV in the year prior to marriage.

Limitations

The findings of this study expand on previous experimental and longitudinal research on the association between alcohol and IPV in important ways. There are, however, some limitations to the current study. First, the current study focused on newly married couples involved in their first marriages. It is unclear whether these findings would emerge in a study, which included couples who had been married for a longer duration, couples for whom this was a second or subsequent marriage for one or both partners, and couples who date seriously or cohabit for a lengthy period of time, but do not marry. Second, although the sample is diverse with regard to ethnicity and socioeconomic status, and the retention rates across the four waves of the study were good, a large number of couples who were initially recruited into the study did not return Wave 1 questionnaires. Differences between those who entered the study and those who did not were minimal, although husbands in non-respondent couples were slightly more likely to reporting past year heavy drinking or intoxication than husbands in respondent couples. Third, the assessment strategy for the current study, asking participants to complete assessments at home and mail them to researchers, is used somewhat less commonly in partner violence research than in-person or phone survey assessment methods. While participants may prefer the privacy this method affords (e.g., MacMilan et al., 2006), different assessment methods reduce the comparability of findings across studies.

Future Directions

Much of what we know about the association problem drinking and IPV is based on clinical samples. Although the relationship between alcohol use and IPV is fairly well established in clinical samples, findings of the present study suggest that the relationship may be moderated by hostility and coping deficits. Future research must continue to examine whether and which moderators identified in laboratory and correlational research on alcohol consumption and non-partner aggression are relevant to our understanding of IPV. Findings of the present study also suggest that hostility, stressors, and coping deficits both dispositional and situational must be further studied to inform prevention approaches for non-treatment seeking couples at risk for IPV. Event-level measurement and analyses may particularly useful in helping to explicate the nature of the interactions among these factors in the potentiation of IPV.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism awarded to Kenneth E. Leonard (R01-AA09922). The findings of this research were presented at the 26th Annual Scientific Meeting of the Research Society on Alcoholism, June 21 – June 26, 2003, in Fort Lauderdale FL.

Contributor Information

Julie A. Schumacher, Department of Psychiatry and Human Behavior, University of Mississippi Medical Center

Gregory G. Homish, Department of Health Behavior, School of Public Health and Health Professions, University at Buffalo, State University of New York

Kenneth E. Leonard, Research Institute on Addictions and Department of Psychiatry, School of Medicine, University at Buffalo, State University of New York

Brian M. Quigley, Research Institute on Addictions, University at Buffalo, State University of New York

Jill N. Kearns-Bodkin, University at Buffalo, State University of New York, and Erie Community College, City Campus

References

- Bailey DS, Taylor SP. Effects of alcohol and aggressive disposition on human physical aggression. Journal of Research in Personality. 1991;25:334–342. [Google Scholar]

- Byers AL, Allore H, Gill TM, Peduzzi PN. Application of negative binomial modeling for discrete outcomes: A case study in aging research. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2003;56(6):559–564. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(03)00028-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caetano R, McGrath C, Ramisetty-Mikler S, Field CA. Drinking, Alcohol Problems and the Five-Year Recurrence and Incidence of Male to Female and Female to Male Partner Violence. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2005;29:98–106. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000150015.84381.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cano A, Vivian D. Life stressors and husband-to-wife violence. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2001;6:459–480. [Google Scholar]

- Chadiha LA, Veroff J, Leber D. Newlywed's narrative themes: Meaning in the first year of marriage for African American and white couples. Journal of Comparative Family Studies. 1998;29(1):115–130. [Google Scholar]

- Coker AL, Davis KE, Arias I, Desai S, Sanderson M, Brandt HM, Smith PH. Physical and Mental Health Effects of Intimate Partner Violence for Men and Women. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2002;23:260–268. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(02)00514-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckhardt CI. Effects of alcohol intoxication on anger experience and expression among partner assaultive men. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2007;75:61–71. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.1.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fals-Stewart W. The occurrence of partner violence on days of alcohol consumption: A longitudinal diary study. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2003;71:41–52. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.71.1.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fals-Stewart W, Leonard KE, Birchler GR. The occurrence of male-to-female intimate partner violence on days of men's drinking: The moderating effects of antisocial personality disorder. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2005;73:239–248. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.2.239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner W, Mulvey EP, Shaw EC. Regression analyses of counts and rates: Poisson, overdispersed poisson, and negative binomial models. Psychological Bulletin. 1995;118(3):392–404. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.118.3.392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giancola PR. Executive Functioning and Alcohol-Related Aggression. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2004;113:541–555. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.113.4.541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giancola PR, Saucier DA, Gussler-Burkhardt NL. The effects of affective, behavioral, and cognitive components of trait anger on the alcohol-aggression relation. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2003;27:1944–1954. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000102414.19057.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gryl FE, Stith SM, Bird GW. Close dating relationships among college students: Differences by use of violence and by gender. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 1991;8:243–264. [Google Scholar]

- Holtzworth-Munroe A, Markman H, O'Leary KD, Neidig P, Leber D, Heyman RE, Hulbert D, Smutzler N. The need for marital violence prevention efforts: A behavioral-cognitive secondary prevention program for engaged and newly married couples. Applied & Preventive Psychology. 1995;4:77–88. [Google Scholar]

- Homish GG, Leonard KE. Relational processes and alcohol use: The role of one's spouse. In: Brozner EY, editor. New research on alcohol abuse and alcoholism. Hauppauge: Nova Science; 2006. pp. 19–33. [Google Scholar]

- Homish GG, Leonard KE. The Drinking partnership and marital satisfaction: The longitudinal influence of discrepant drinking. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2007;75:43–51. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.1.43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacob T, Leonard KE, Haber JR. Family interactions of alcoholics as related to alcoholism type and drinking condition. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2001;25:835–843. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kantor GK, Straus MA. The drunken bum theory of wife beating. Social Problems. 1987;34:214–230. [Google Scholar]

- Kohn PM, McDonald JM. The Survey of Recent Life Experiences: A decontaminated hassles scale for adults. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 1992;15:221–226. doi: 10.1007/BF00848327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonard KE. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Research Monograph 24: Alcohol and Interpersonal Violence: Fostering Multidisciplinary Perspectives. Rockville, MD: National Institutes of Health; 1993. Drinking patterns and intoxication in marital violence: Review, critique, and future directions for research; pp. 253–280. NIH Publication 93-3496. [Google Scholar]

- Leonard KE, Blane HT. Alcohol and marital aggression in a national sample of young men. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 1992;7:19–30. [Google Scholar]

- Leonard KE, Mudar P. Peer and partner drinking and the transition to marriage: A longitudinal examination of selection and influence processes. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2003;17(2):115–125. doi: 10.1037/0893-164x.17.2.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonard KE, Senchak M. Prospective prediction of husband marital aggression within newlywed couples. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1996;105:369–380. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.105.3.369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipsey MW, Wilson DB, Cohen MA, Derzon JH. Is there a causal relationship between alcohol use and violence? A synthesis of evidence. In: Galanter M, editor. Recent developments in alcoholism, Volume 13: Alcoholism and violence. New York: Plenum; 1997. pp. 245–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margolin G, John RS, Foo L. Interactive and unique risk factors for husbands' emotional and physical abuse of their wives. Journal of Family Violence. 1998;13:315–344. [Google Scholar]

- MacMilan HL, Wathen CN, Jamieson E, Boyle M, McNutt LA, Worster A, Lent B, Webb M for the McMaster Violence Against Women Research Group. Approaches to screening for intimate partner violence in health care settings. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2006;296:530–536. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.5.530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCormick RA, Smith M. Aggression and hostility in substance abusers: The relationship to abuse patterns, coping style, and relapse, triggers. Addictive Behaviors. 1995;20:555–562. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(95)00015-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moeller FG, Dougherty DM, Lane SD, Steinberg JL, Cherek DR. Antisocial personality disorder and alcohol-induced aggression. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 1998;22:1898–1902. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy CM, O'Farrell TJ. Factors associated with marital aggression in male alcoholics. Journal of Family Psychology. 1994;8:321–335. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy CM, Winters J, O'Farrell TJ, Fals-Stewart W, Murphy M. Alcohol Consumption and Intimate Partner Violence by Alcoholic Men: Comparing Violent and Nonviolent Conflicts. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2005;19:35–42. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.19.1.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neal DJ, Carey KB. Association between alcohol intoxication and alcohol-related problems: An event-level analysis. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2007;21:194–204. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.21.2.194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norlander B, Eckhardt C. Anger, hostility, and male perpetrators of intimate partner violence: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review. 2005;25:119–152. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2004.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pernanen K. Alcohol and crimes of violence. In: Kissin B, Begleiter H, editors. The biology of alcoholism: Vol 4 Social aspects of alcoholism. New York: Plenum Press; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Rothbard JC. Unpublished doctoral dissertation. State University of New York at Buffalo; 1996. Attachment-based working models and personal adjustment: The medicational effects of coping with stress. [Google Scholar]

- Schafer J, Caetano R, Cunradi CB. A path model of risk factors for intimate partner violence among couples in the United States. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2004;19:127–142. doi: 10.1177/0886260503260244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schumacher JA, Fals-Stewart W, Leonard KE. Domestic violence treatment referrals for men seeking alcohol treatment. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2003;24:279–283. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(03)00034-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schumacher JA, Feldbau-Kohn S, Slep AMS, Heyman RE. Risk factors for male-to-female partner physical abuse. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2001;6:281–352. [Google Scholar]

- Schumacher JA, Leonard KE. Husbands' and wives' marital adjustment, verbal aggression, and physical aggression as longitudinal predictors of physical aggression in early marriage. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2005;73:28–37. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.1.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silver E, Teasdale B. Mental disorder and violence: An examination of stressful life events and impaired social support. Social Problems. 2005;52:62–78. [Google Scholar]

- Skinner HA, Allen BA. Alcohol dependence syndrome: Measurement and validation. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1982;91:199–209. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.91.3.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skinner HA, Horn JL. Alcohol dependence scale: Users guide. Toronto: Addiction Research Institute; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Snow DL, Sullivan TP, Swan SC, Tate DC, Klein I. The role of coping and problem drinking in men's abuse of female partners: Test of a path model. Violence and Victims. 2006;21:267–285. doi: 10.1891/vivi.21.3.267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- StataCorp. Stata statistical software (Version 8) College Station: StataCorp LP; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Steele CM, Josephs RA. Alcohol myopia: Its prized and dangerous effects. American Psychologist. 1990;45:921–933. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.45.8.921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA, Gelles RJ. Physical violence in American families. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA, Hamby SL, Boney-McCoy S, Sugarman DB. The revised Conflict Tactics Scale (CTS2): Development and preliminary psychometric data. Journal of Family Issues. 1996;17:283–316. [Google Scholar]

- Stuart GL, Meehan JC, Moore TM, Morean M, Hellmuth J, Follansbee K. Examining a conceptual framework of intimate partner violence in men and women arrested for domestic violence. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2006;67:102–112. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2006.67.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor SP, Leonard KE. Alcohol and human physical aggression. In: Geen RG, Donnerstein EI, editors. Aggression: Theoretical and empirical reviews. New York: Academic Press; 1983. pp. 77–101. [Google Scholar]

- Twisk JW. Longitudinal data analysis. A comparison between generalized estimating equations and random coefficient analysis. European Journal of Epidemiology. 2004;19:769–776. doi: 10.1023/b:ejep.0000036572.00663.f2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Z. Generalized linear models in family studies. Journal of Marriage & the Family. 2005;67:1029–1047. [Google Scholar]

- Zeger SL, Liang KY. Longitudinal data analysis for discrete and continuous outcomes. Biometrics. 1986;42:121–130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeger SL, Liang KY, Albert PS. Models for longitudinal data: A generalized estimating equation approach. Biometrics. 1988;44:1049–1060. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zlotnick C, Johnson DM, Kohn R. Intimate partner violence and long-term psychosocial functioning in a national sample of American women. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2006;21:262–275. doi: 10.1177/0886260505282564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]