Abstract

A lysine at the 627 position (627K) of PB2 protein of influenza virus has been recognized as a determinant for host adaptation and virulent element for some influenza viruses. While seasonal influenza viruses exclusively contained 627K, the pandemic (H1N1) 2009 possessed a glutamic acid (627E), even after circulation in humans for more than 6 months. To explore the potential role of E627K substitution in PB2 in the pandemic (H1N1) 2009 virus, we compared pathogenicity and growth properties between a recombinant virus containing 627K PB2 gene and the parental A/California/4/2009 strain containing 627E. Our results showed that substitution of 627K in PB2 gene does not confer higher virulence and growth rate for the pandemic (H1N1) 2009 virus in mice and cell culture respectively, suggesting 627K is not required for human adaptation of the pandemic (H1N1) 2009 virus.

Keywords: Influenza virus, pathogenicity, virulence, PB2–627 residue, and temperature-sensitivity

Introduction

After introduction into humans, a swine-origin influenza A H1N1 virus (S-OIV) has rapidly caused global transmission in a couple of months and led to the declaration of the 2009 pandemic by World Health Organization on June 11, 2009. Although the overall clinical symptoms of the disease are mild and similar to those caused by seasonal influenza, there have been severe cases and it has claimed over 5,700 human lives worldwide by the end of October, 2009 (http://www.who.int/csr/don/2009_10_30/en/index.html). Genetic analysis showed the pandemic (H1N1) 2009 virus has undergone very limited genetic mutations up to now (http://www.who.int/csr/don/2009_10_16/en/index.html). The virulence markers which were frequently observed in avian H5N1 virus infection of mammals were absent (Neumann et al., 2009). However, there is still a concern that the pandemic (H1N1) 2009 virus may evolve into a more virulent form as that observed in the “Spanish flu” during the fall of 1918.

Pathogenicity of influenza virus involves polygenic traits. Residue 627 of the polymerase basic protein 2 (PB2) was recognized as one of the most important determinants (Subbarao et al., 1993; Hatta et al., 2001). The E627K substitution was observed to enhance virulence and viral replication in mice and other mammals (Mase et al., 2006; Manzoor et al., 2009; Steel et al, 2009; Le et al., 2009). It was also reported to contribute to the improved replication of H5N1 influenza virus at the lower temperature of 33°C, thus confer virus advantages for efficient growth in the upper respiratory tracts of mammals and transmission (Massin et al, 2001; Hatta et al, 2007; Steel et al, 2009; Van Hoeven et al., 2009). Notably, all previous human influenza viruses established through the three pandemics in 20th century contained 627K in PB2, while most of avian influenza viruses carried glutamic acid (E) instead. Genetic analysis showed that swine influenza viruses had either K or E at this position and current human pandemic (H1N1) 2009 viruses possessed a 627E (Influenza Virus Resource, NCBI, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genomes/FLU/). Whether the substitution of E627K in PB2 gene of the pandemic (H1N1) 2009 virus may occur after prevailing in human for a period of time, and whether such change may alter the virulence of current pandemic H1N1 virus is still unknown.

To investigate the potential pathogenic effect of PB2 E627K substitution in the pandemic (H1N1) 2009 virus, we reconstructed a recombinant virus with a single residue substitution at PB2 627 position from A/California/04/2009 strain and tested its pathogenicity in mice and its growth properties in MDCK cells under different temperatures. Our findings suggested a 627K substitution in PB2 gene does not confer higher virulence or growth properties for the pandemic (H1N1) 2009 virus.

Results

Effects of PB2 E627K substitution on the viral replication and pathogenicity of A/California/04/2009 (H1N1) virus in mice

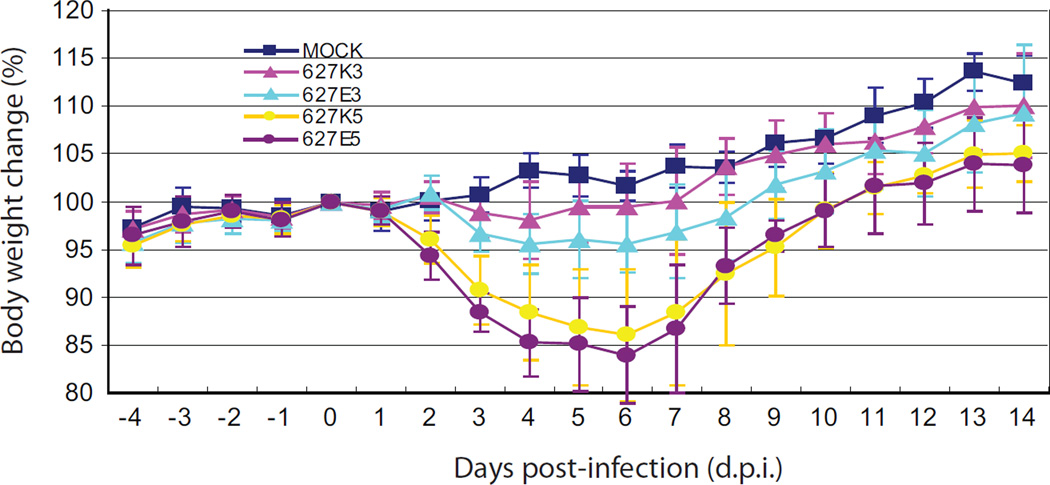

To assess the potential effect of a PB2 E627K substitution on the pandemic (H1N1) 2009 virus, we constructed a recombinant virus by introducing a lysine into the 627 position of PB2 gene in the background of A/California/04/2009 (CA04). The pathogenicity and viral growth properties in the lung tissues were compared between the reconstituted wild-type CA04 627E and its 627K counterpart in infected mice. Groups of 22 mice were inoculated with 103 or 105 PFU of viruses respectively. The clinic signs and body weight change from the infected mice were monitored daily for 14 days. Our results showed that inoculation of CA04-RG-627E or CA04-RG-627K viruses with either 103 or 105 PFU was not lethal to mice. Mice infected with 105 PFU dose of either virus experienced body weight loss starting on 2 d.p.i., and reached the lowest level on 6 d.p.i.. However, there was no significant difference between the CA04-RG-627E and the CA04-RG-627K groups (P>0.05) (Fig. 1). Overt clinic signs were observed on 3–4 d.p.i., when most infected mice in these groups suffered from inactivity, anorexia and ruffled fur. Animals infected with a lower dose of either viruses (103 PFU) shown milder symptoms and less weight loss (P<0.001), compared with those from the higher dose inoculation groups (Fig. 1.). Mice infected with 103 PFU of CA04-RG-627K virus had slightly less weight loss than those infected with the same dose of CA04-RG-627E virus throughout the course of experiment (P<0.001) (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Body weight changes in infected mice. Twenty-two mice per group were intranasally inoculated with PBS (mock), 103 or 105 PFU (each in 25 µl of PBS) of reverse genetics-derived viruses. Body weights were monitored daily for 14 days or prior to the sacrifice of each experimental mouse. Groups of 627K3 and 627K5 represent infection with 103 or 105 PFU of CA04-RG-K virus (containing 627 K) in mice respectively, while groups of 627E3 and 627E5 represent infection with 103 or 105 PFU of CA04-RG-E virus (containing 627 E) respectively. The values are means (±standard deviation) from each group.

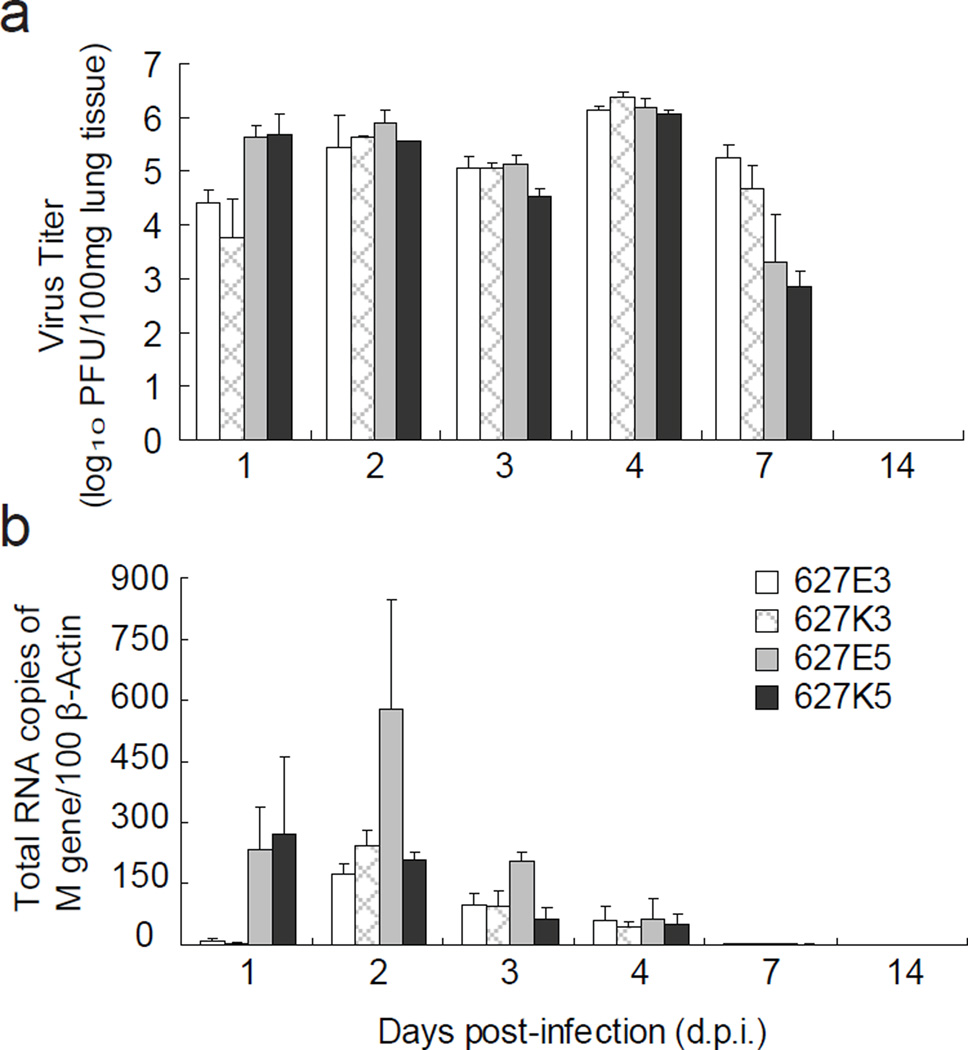

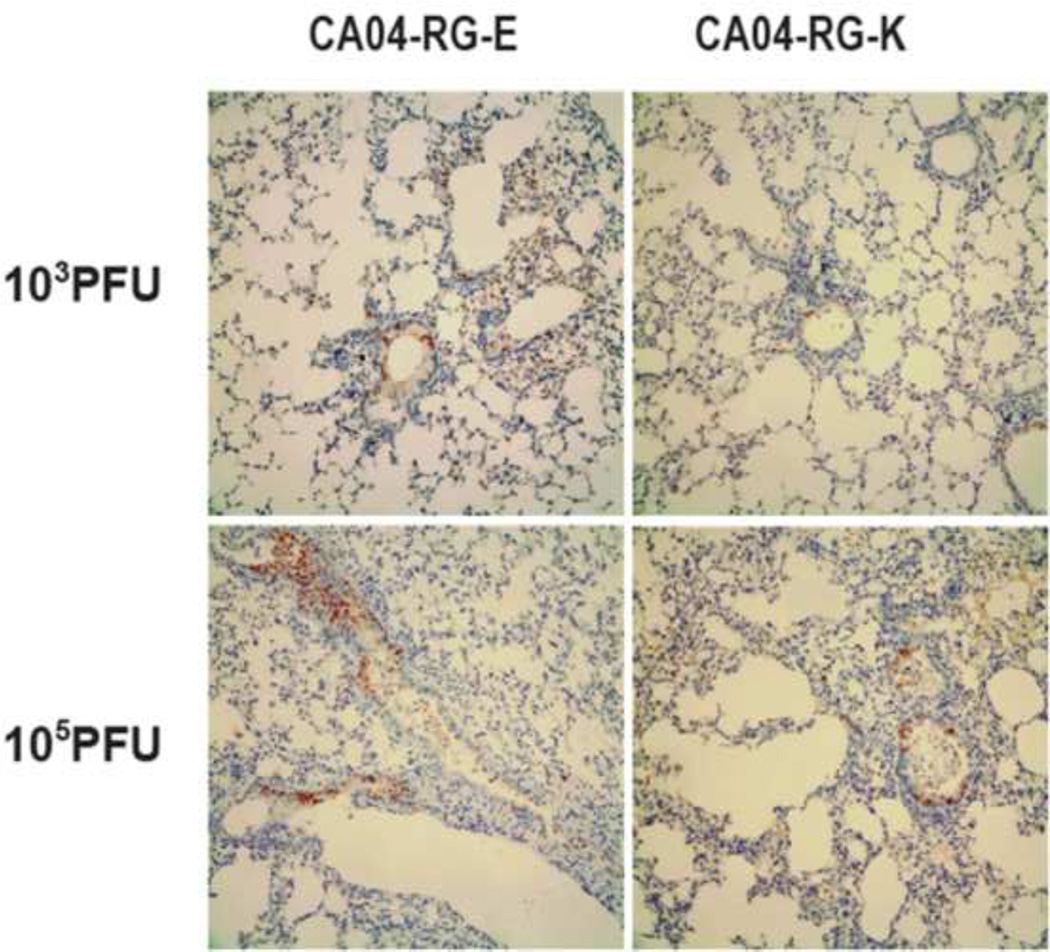

CA04 virus was reported to cause prominent bronchitis, alveolitis and efficient viral replication in the lung tissues of infected mice (Itoh et al., 2009). In this study, we examined virus replication in trachea, lung, intestine and brain tissues of the infected mice. No virus replication was observed beyond pulmonary system of mice infected with either CA04-RG-627E or CA04-RG-627K virus by histochemical staining of viral nucleoprotein (data not shown). Notably, viral replication was observed in mice lungs from the first day post-infection (Fig. 2), implicating the tendency of replication in lower respiratory tract by the pandemic (H1N1) 2009 virus. Consistent with the observation of body weight changes, virus growth in lung tissue was observed during the first four days post-infection (Fig. 2), and lower dose of virus inoculation resulted in less severe lung lesions, with viral antigen (nucleoprotein, NP) mostly detected in the terminal bronchiolar epithelia and desquamated cells in the bronchiolar lumen (Fig. 3). Examination of virus replication activity with quantitative RT-PCR found that virus replication reached the highest level on the first two days post-infection, decreased gradually thereafter; and virus was cleared after 7 days post-infection (Fig. 2b). Although 627K of PB2 gene was reported to associate with increased virus replication, our results found no significant difference in virulence and virus replication in lung tissues of infected mice with the PB2 627K and 627E viruses derived from the pandemic (H1N1) 2009 virus (P>0.05) (Figs. 2 & 3). It is important to note that while mice infected with 105 PFU of viruses exhibited more body weight loss (Fig. 1), examination of virus titer in lung tissues found there was a significant reduction in virus titer from 105 PFU dose of both 627E and 627K groups on day 7 post infection (Fig. 2a). It remains to be investigated if inoculation with higher dose of virus may induce stronger host immune response, leading to the rapid clearness of virus in the lung.

Fig. 2.

Effects of PB2 E627K substitution on virus replication in lung tissues of infected mice. Twenty-two mice per group were intranasally inoculated with PBS (mock), 103 or 105 PFU (each in 25 µl of PBS) of reverse genetics-derived viruses respectively. On days 1, 2, 3, 4, and 7 post-infection (d.p.i.), three mice from each group were euthanized. Virus titer and viral RNA level in lung homogenate of each mouse were determined by plaque assay (a) and quantitative RT-PCR (b) as described in the materials and methods. The values are means (±standard deviation) of three mice.

Fig. 3.

Histochemical staining of viral nucleoprotein in lung tissues of infected mice (represented by 4 days post-infection). Viral antigen (nucleoprotein, NP) was detected with a mouse anti-NP monoclonal antibody, mainly observed in the terminal bronchiolar epithelia and desquamated cells in the bronchiolar lumen. Original magnification: 200×.

Effects of PB2 E627K substitution on the growth property of CA04 on MDCK cells at different temperatures

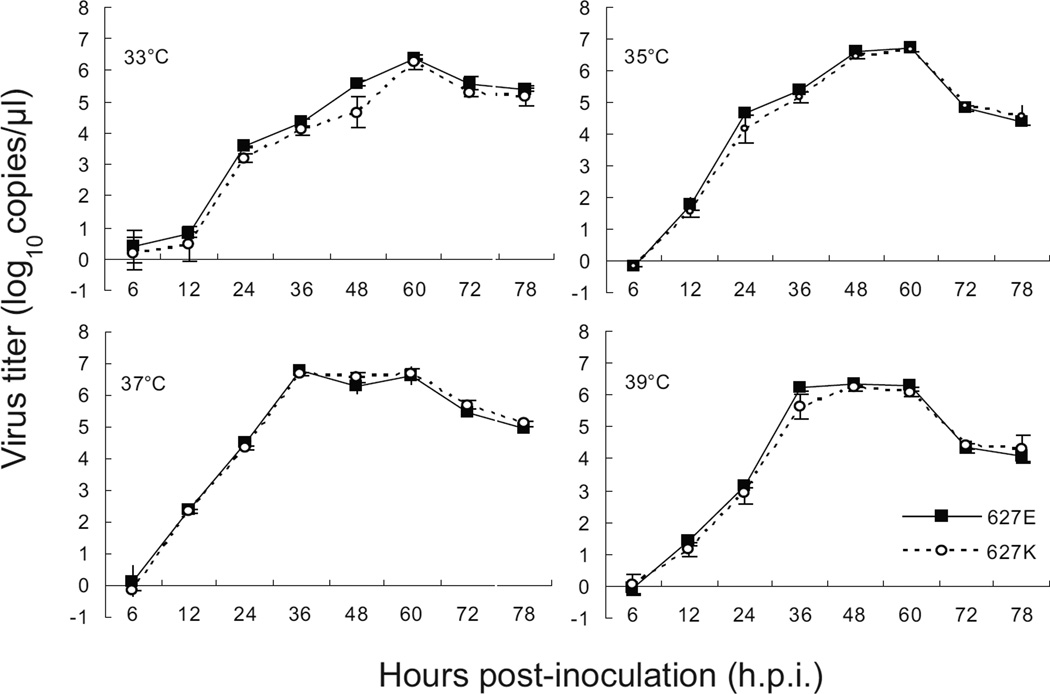

The E627K substitution in PB2 gene of avian H5N1 influenza virus was reported to be responsible for the increased growth efficiency in mammals, especially at lower temperatures of 32–33°C (Massin et al. 2001; Hatta et al., 2007). Our animal experiment showed CA04-RG-627K did not change growth properties of the pandemic (H1N1) 2009 virus in mouse lung tissues, with the body temperature at approx. 37–39°C. We then further characterized the growth kinetics of CA04-RG-627E and CA04-RG-627K viruses at different temperatures in MDCK cells. Both viruses were shown to be sensitive to temperature change and have severe growth delay at 33°C (P<0.01) during the first 48 h.p.i (Fig. 4). No significant difference was observed between these two viruses in replication kinetics at all temperature tested (33–39°C) (P>0.05), suggesting PB2 627K did not confer any advantage over 627E for the growth of pandemic (H1N1) 2009 virus in MDCK cells. Estimation of virus titer in MDCK culture with plaque assay found similar result (Supplementary Fig. S1).

Fig. 4.

Growth properties of reconstituted A/California/04/2009 (H1N1) virus and the PB2 627K variant in MDCK cells at different temperatures. Cells were infected with reverse genetics-derived viruses with a wild-type PB2 627E (CA04-RG-E) or a 627K variant (CA04-RG-K) at a MOI of 0.001. Infected cells were incubated at 33, 35, 37 or 39°C as indicated. Aliquots of the supernatants were collected and titrated by quantitative RT-PCR. The values are means (±SD) of three independent determinations.

Discussion

Increasing evidence strongly suggested that the amino acid at 627 position of the polymerase basic protein 2 (PB2) is associated with host range adaptation (Subbarao et al., 1993; Gabriel et al., 2007; Labadie et al., 2007). Of note, most avian and all equine influenza viruses have a glutamic acid (E), so does the pandemic (H1N1) 2009 virus. By contrast, human influenza viruses established in the last century exclusively contained a lysine (K), while viruses from pigs possessed either E or K in 627 position of PB2 gene (according to sequences released in Influenza Virus Resource, NCBI, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genomes/FLU/ up to Nov 19, 2009).

Studies on viral pathogenecity revealed that a single amino acid substitution of E627K in PB2 would remarkably enhance the virulence of avian H5N1 and equine H7N7 influenza viruses in mammalian species (Hatto et al., 2001; Shinya et al., 2007; Munster et al, 2007). Most strikingly, a single passage in mice was reported to be sufficient for the avian H5N1 virus to acquire the E627K substitution, and all recovered viruses from the brains of dead mice turned out to have a 627K (Mase et al., 2006). In addition to H5 and H7 subtypes, PB2 627K was also found to confer increased transmission and plaque-forming abilities for human H3N2 and pandemic 1918 strain (Van Hoeven et al., 2009; Steel et al, 2009). As such, a lysine at PB2 627 position has been considered as one of the most important determinants of pathogenecity and host range for influenza viruses. Whether current pandemic H1N1 virus may evolve to obtain E627K substitution remains to be seen. However, it would be important to examine if the 627K variant may result in altered virulence in animal models, which would have a significant implication on this undergoing pandemic.

In this study, we demonstrated that the single amino acid substitution of PB2 E627K, in the context of the current influenza pandemic stain, rendered neither increased pathogenecity in mice, nor improved viral replication in MDCK cells under 33–39°C. As the normal temperatures of human distal and proximal airways are approximately within this range, a reasonable predictive implication can be deduced that a lysine at PB2 627 position might not confer improved viral replication and virulence in humans.

The difference on effects of the PB2 627K residue in pandemic (H1N1) 2009 from this study and previous reports mainly in H5N1 and H7N7 subtypes may be due to the different interactions between PB2 and other viral genes in the different genetic context of these viruses. It was reported that increased virulence in mice caused by the E627K mutation in H5N1 avian influenza virus could be compensated by multiple mutations at other sites of PB2 gene (L89V, G309D, T339K, R477G, I495V and A676T), suggesting that E627K substitution may not be an indispensable determinant for virulence (Li et al., 2009). Genetic analysis revealed that the pandemic (H1N 1) 2009 contained all six “compensating” residues in PB2 gene. In another study, substitutions at 590 and 591 positions in PB2 gene was reported to act as adaptive strategies for the pandemic (H1N1) 2009 virus polymerase to replicate in humans (Mehle & Doudna, 2009). These evidences may partially explain why the pandemic (H1N1) 2009 virus can replicate and transmit efficiently in humans without the function of PB2 627K.

With the pandemic (H1N1) 2009 virus continues to circulate in humans, it is likely that more adaptive mutations will emerge along the course of transmission in humans. Acquisition of possible pathogenic determinants through mutation or gene reassortment with other influenza viruses may generate more virulent variants. Our study, however, suggested that the 627K mutation in PB2 alone, if it occurs, may not raise the risk significantly.

Materials and methods

Viruses and cells

The reference human H1N1 virus, A/California/04/2009 (CA04), was kindly provided by the World Health Organization Collaborating Centers for Reference and Research on Influenza (Atlanta, GA, USA). Madin-Darby canine kidney (MDCK) and human embryonic kidney (HEK) 293T cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) and propagated in Eagle's minimal essential medium (MEM) and Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), respectively. Viral stocks were prepared in MDCK cells. All experiments with live viruses and transfectants were conducted in biosafety level 3 (BSL3) containment laboratories.

Generation of recombinant viruses by reverse genetics

The CA04-derived recombinant viruses were generated as previously reported (Hoffmann et al., 2001). In brief, viral RNA was extracted from CA04 stocks using QIAamp viral RNA minikit (QIAGEN). The cDNAs was synthesized with Uni12 primer using Transcriptor High Fidelity cDNA synthesis Kit (Roche). All eight viral genes of CA04 were amplified using PfuUltra® II Fusion HS DNA Polymerase (Stratagene) and cloned into pHW2000 plasmid. QuikChange® II Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (Stratagene) was used for generation of E627K mutations in PB2 gene. All plasmids we re sequenced to ensure the absence of unwanted mutations.

The rescue of infectious virus from cloned cDNA was conducted as previously described (Hoffmann et al., 2000). Briefly, 293T cells were co-cultured with MDCK cells in opti-modified Eagle's medium (Opti-MEM) (Gibco/Life technologies) supplemented with 1.5% (v/v) of Antibiotic Antimycotic Solution (100×) (Sigma). After overnight incubation, sub-confluent (70%) monolayers were used for co-transfection with eight plasmids (1 µg each plasmid) using TransIT®-LT1 Transfection Reagent (Mirus). 48–72 h after transfection, culture supernatant was inoculated to MDCK cells and then passaged for preparation of viral stocks. Identities of the recombinant viruses were confirmed by sequencing before the animal test. The reverse genetics-derived virus with all wild-type gene segments of CA04 was designated as CA04-RG-E while that with a single E627K substitution in PB2 gene as CA04-RG-K.

Virus growth kinetics in MDCK cell culture

MDCK cells were infected with each virus in triplicate at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 0.001 and incubated at 33, 35, 37 or 39°C. Aliquots of the supernatants were collected at 6, 12, 24, 36, 48, 60, 72 and 78h post-inoculation (h.p.i.) and titrated by real-time RT-PCR and plaque assay on MDCK cells.

Pathogenicity test in mice

Eight- to nine-week-old female BALB/c mice were used in this study. Baseline body weights were established prior to infection. Twenty-two mice per group were intranasally inoculated with 103 or 105 PFU (plaque forming unit) of viruses in 25µl of PBS under lightly anaesthetized by inhalation of 4% isoflurane. For the mock group, 25µl of PBS was used. Body weight, clinical signs of infection, and survival were monitored daily for 14 days and mice with body weight loss greater than 25% of pre-infection values were euthanized humanely. Three mice from each group were sacrificed respectively on days 1, 2, 3, 4, 7 post-infection (d.p.i.). The remainders (7 mice per group) were kept for observation and euthanatized at the end of the experiment (14 d.p.i.).

Viral titration from the mouse organs

Tissues for viral titrations were removed and kept at −80°C until homogenized in 9 fold volume of cold PBS and clarified by centrifugation. Virus titers of homogenates were determined by plaque assays in MDCK cells and by real-time PCR.

Pathological examination

Fresh excised tissues of the trachea, lungs, intestines and brains from the mice were preserved in 10% phosphate-buffered formalin. After 24 hours’ fixation, tissues were dehydrated, embedded in paraffin, and cut into 5-µm-thick sections. For sections from each tissue sample, standard histochemistry staining procedure with Hematoxylin and Eosin (Sigma) (H&E) as w ell as immunohistochemistry (IHC) assay with a mouse anti-NP monoclonal antibody (provided by the National Institute of Diagnostics and Vaccine Development for Infectious Diseases, Xiamen University) was performed in parallel. Goat anti-mouse IgG - biotin conjugate secondary antibody was purchased from Calbiochem. Specific viral antigen was visualized by 3,3’-diaminobenzidaine tetrahydrochloride staining as brown. Nine discrete, non-overlapping fields of view with a magnification of 400× were observed for each section and the number of positive viral antigen was calculated.

Real-time RT-PCR

Viral RNA was extracted from CA04 stocks using QIAamp viral RNA minikit (QIAGEN) and cDNAs were synthesized with Uni12 or random primers using Transcriptor High Fidelity cDNA synthesis Kit (Roche). Copy numbers of the influenza M segment were determined on a LightCycler® 480 Real-Time PCR System (Roche) with LightCycler® FastStart DNA MasterPLUS SYBR Green I Kit (Roche) and normalized by the expression of β-Actin gene. Primers used for the analysis of M gene were M-146F (GACCRATCCTGTCACCTCTGAC) and M-251R (AGGGCATTYTGGACAAAKCGTCTA), while those for β-Actin gene were Act-1132F (TGGATCAGCAAGCAGGAGTATG) and Act1188R (GCATTTGCGGTGGACGAT).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed by Mean Analysis with PASW Statistics 18 (SPSS Inc., Chicago IL). The probability of a significant difference was computed using ANOVA (analysis of variance). Results were considered significant at P<0.05.

Supplementary Material

Fig. S1. Growth properties of reconstituted A/California/04/2009 (H1N1) virus and the PB2 627K variant in MDCK cells at different temperatures. Cells were infected with reverse genetics-derived viruses with a wild-type PB2 627E (CA04-RG-E) or a 627K variant (CA04-RG-K) at a MOI of 0.001. Infected cells were incubated at 33, 35, 37 or 39°C as indicated. Aliquots of the supernatants were collected and titrated by plaque assays on MDCK cells. The values are means (±SD) of three independent determinations.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge our colleagues from IIII and SKLEID for their excellent technical assistance. This study was supported by Li Ka Shing Foundation, the Area of Excellence Scheme of the University Grants Committee of the Hong Kong SAR grant AoE/M-12/06), the Research Grant Council of Hong Kong SAR (HKU 7488/05M and 7500/06M), and the National Institutes of Health (NIH, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases contract HSN266200700005C).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:XXXXX.

References

- Gabriel G, Abram M, Keiner B, Wagner R, Klenk HD, Stech J. Differential polymerase activity in avian and mammalian cells determines host range of influenza virus. J Virol. 2007;81:9601–9604. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00666-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatta M, Gao P, Halfmann P, Kawaoka Y. Molecular basis for high virulence of Hong Kong H5N1 influenza A viruses. Science. 2001;293:1840–1842. doi: 10.1126/science.1062882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatta M, Hatta Y, Kim JH, Watanabe S, Shinya K, Nguyen T, Lien PS, Le QM, Kawaoka Y. Growth of H5N1 influenza A viruses in the upper respiratory tracts of mice. PLoS Pathog. 2007;3:1374–1379. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0030133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann E, Neumann G, Kawaoka Y, Hobom G, Webster RG. A DNA transfection system for generation of influenza A virus from eight plasmids. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:6108–6113. doi: 10.1073/pnas.100133697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann E, Stech J, Guan Y, Webster RG, Perez DR. Universal primer set for the full-length amplification of all influenza A viruses. Arch Virol. 2001;146:2275–2289. doi: 10.1007/s007050170002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itoh Y, Shinya K, Kiso M, Watanabe T, Sakoda Y, Hatta M, Muramoto Y, Tamura D, Sakai-Tagawa Y, Noda T, Sakabe S, Imai M, Hatta Y, Watanabe S, Li C, Yamada S, Fujii K, Murakami S, Imai H, Kakugawa S, Ito M, Takano R, Iwatsuki-Horimoto K, Shimojima M, Horimoto T, Goto H, Takahashi K, Makino A, Ishigaki H, Nakayama M, Okamatsu M, Takahashi K, Warshauer D, Shult PA, Saito R, Suzuki H, Furuta Y, Yamashita M, Mitamura K, Nakano K, Nakamura M, Brockman-Schneider R, Mitamura H, Yamazaki M, Sugaya N, Suresh M, Ozawa M, Neumann G, Gern J, Kida H, Ogasawara K, Kawaoka Y. In vitro and in vivo characterization of new swine-origin H1N1 influenza viruses. Nature. 2009;460:1021–1025. doi: 10.1038/nature08260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labadie K, Dos Santos Afonso E, Rameix-Welti MA, van der Werf S, Naffakh N. Host- range determinants on the PB2 protein of influenza A viruses control the interaction between the viral polymerase and nucleoprotein in human cells. Virology. 2007;362:271–282. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2006.12.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le QM, Sakai-Tagawa Y, Ozawa M, Ito M, Kawaoka Y. Selection of H5N1 influenza virus PB2 during replication in humans. J Virol. 2009;83:5278–5281. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00063-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Ishaq M, Prudence M, Xi X, Hu T, Liu Q, Guo D. Single mutation at the amino acid position 627 of PB2 that leads to increased virulence of an H5N1 avian influenza virus during adaptation in mice can be compensated by multiple mutations at other sites of PB2. Virus Res. 2009;144:123–129. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2009.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manzoor R, Sakoda Y, Nomura N, Tsuda Y, Ozaki H, Okamatsu M, Kida H. PB2 protein of a highly pathogenic avian influenza virus strain A/chicken/Yamaguchi/7/2004 (H5N1) determines its replication potential in pigs. J Virol. 2009;83:1572–1578. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01879-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mase M, Tanimura N, Imada T, Okamatsu M, Tsukamoto K, Yamaguchi S. Recent H5N1 avian influenza A virus increases rapidly in virulence to mice after a single passage in mice. J Gen Virol. 2006;87:3655–3659. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.81843-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massin P, van der Werf S, Naffakh N. Residue 627 of PB2 is a determinant of cold sensitivity in RNA replication of avian influenza viruses. J Virol. 2001;75:5398–5404. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.11.5398-5404.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehle A, Doudna JA. Adaptive strategies of the influenza virus polymerase for replication in humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:21312–21316. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0911915106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munster VJ, de Wit E, van Riel D, Beyer WE, Rimmelzwaan GF, Osterhaus AD, Kuiken T, Fouchier RA. The molecular basis of the pathogenicity of the Dutch highly pathogenic human influenza A H7N7 viruses. J Infect Dis. 2007;196:258–265. doi: 10.1086/518792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neumann G, Noda T, Kawaoka Y. Emergence and pandemic potential of swine-origin H1N1 influenza virus. Nature. 2009;459:931–939. doi: 10.1038/nature08157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinya K, Watanabe S, Ito T, Kasai N, Kawaoka Y. Adaptation of an H7N7 equine influenza A virus in mice. J Gen Virol. 2007;88:547–553. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.82411-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steel J, Lowen AC, Mubareka S, Palese P. Transmission of influenza virus in a mammalian host is increased by PB2 amino acids 627K or 627E/701N. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000252. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subbarao EK, London W, Murphy BR. A single amino acid in the PB2 gene of influenza A virus is a determinant of host range. J Virol. 1993;67:1761–1764. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.4.1761-1764.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Hoeven N, Pappas C, Belser JA, Maines TR, Zeng H, García-Sastre A, Sasisekharan R, Katz JM, Tumpey TM. Human HA and polymerase subunit PB2 proteins confer transmission of an avian influenza virus through the air. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:3366–3371. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0813172106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Fig. S1. Growth properties of reconstituted A/California/04/2009 (H1N1) virus and the PB2 627K variant in MDCK cells at different temperatures. Cells were infected with reverse genetics-derived viruses with a wild-type PB2 627E (CA04-RG-E) or a 627K variant (CA04-RG-K) at a MOI of 0.001. Infected cells were incubated at 33, 35, 37 or 39°C as indicated. Aliquots of the supernatants were collected and titrated by plaque assays on MDCK cells. The values are means (±SD) of three independent determinations.