Abstract

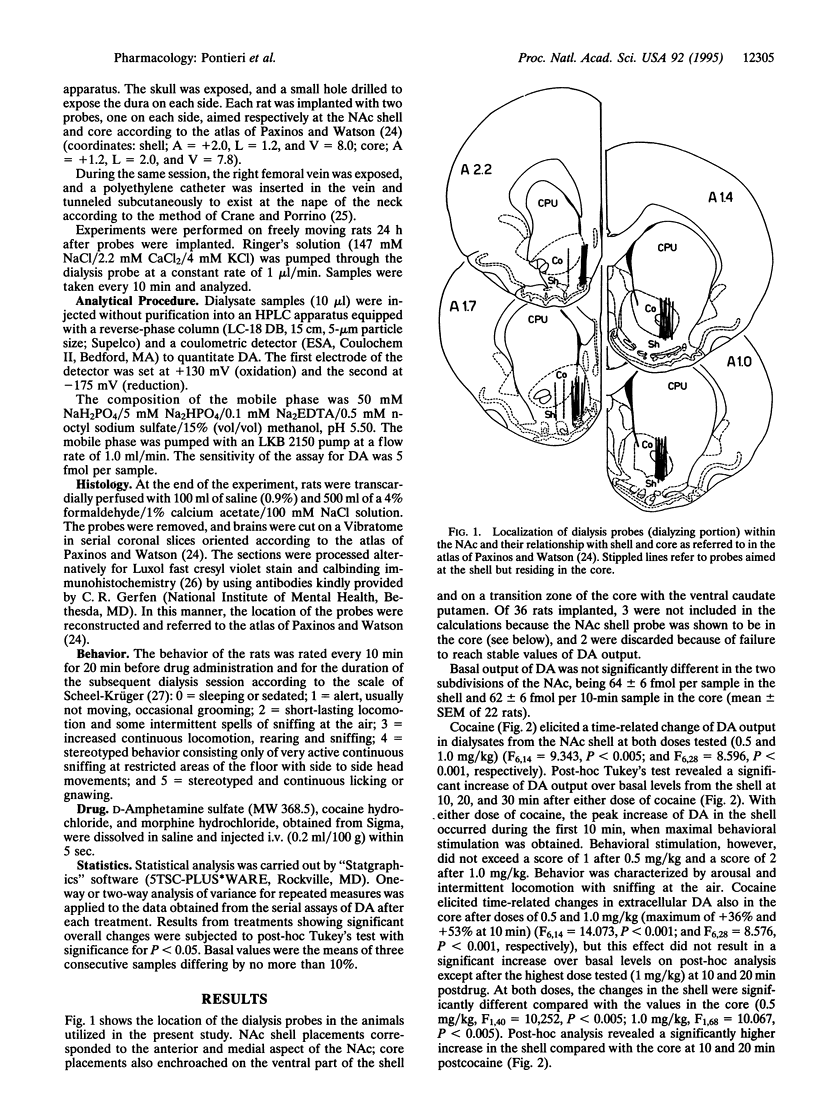

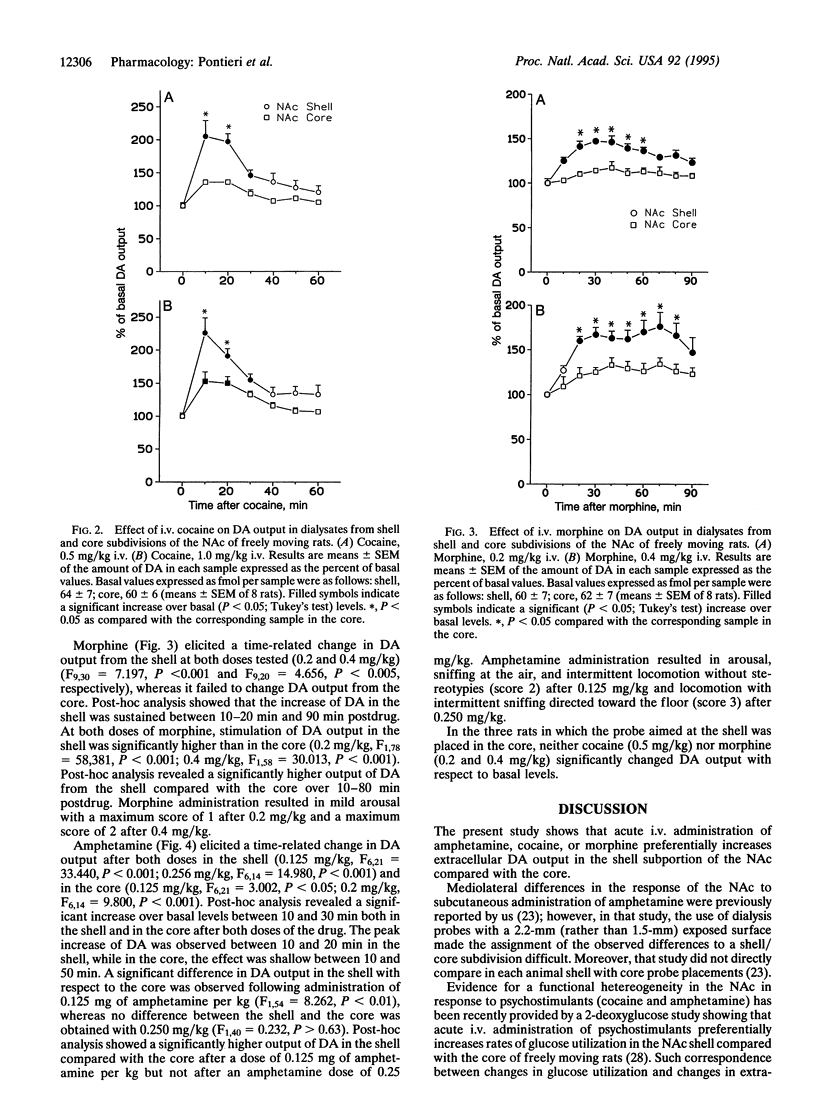

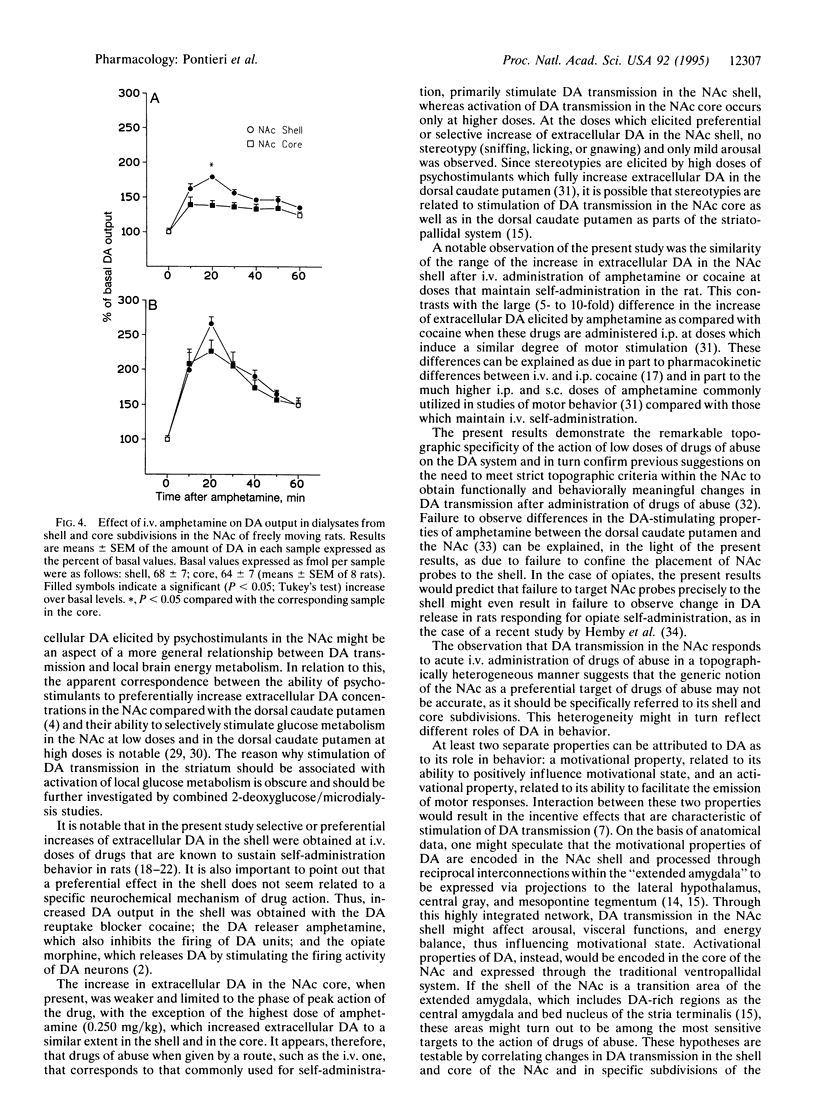

The nucleus accumbens is considered a critical target of the action of drugs of abuse. In this nucleus a "shell" and a "core" have been distinguished on the basis of anatomical and histochemical criteria. The present study investigated the effect in freely moving rats of intravenous cocaine, amphetamine, and morphine on extracellular dopamine concentrations in the nucleus accumbens shell and core by means of microdialysis with vertically implanted concentric probes. Doses selected were in the range of those known to sustain drug self-administration in rats. Morphine, at 0.2 and 0.4 mg/kg, and cocaine, at 0.5 mg/kg, increased extracellular dopamine selectivity in the shell. Higher doses of cocaine (1.0 mg/kg) and the lowest dose of amphetamine tested (0.125 mg/kg) increased extracellular dopamine both in the shell and in the core, but the effect was significantly more pronounced in the shell compared with the core. Only the highest dose of amphetamine (0.250 mg/kg) increased extracellular dopamine in the shell and in the core to a similar extent. The present results provide in vivo neurochemical evidence for a functional compartmentation within the nucleus accumbens and for a preferential effect of psychostimulants and morphine in the shell of the nucleus accumbens at doses known to sustain intravenous drug self-administration.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Alheid G. F., Heimer L. New perspectives in basal forebrain organization of special relevance for neuropsychiatric disorders: the striatopallidal, amygdaloid, and corticopetal components of substantia innominata. Neuroscience. 1988 Oct;27(1):1–39. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(88)90217-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brazell M. P., Mitchell S. N., Joseph M. H., Gray J. A. Acute administration of nicotine increases the in vivo extracellular levels of dopamine, 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetic acid and ascorbic acid preferentially in the nucleus accumbens of the rat: comparison with caudate-putamen. Neuropharmacology. 1990 Dec;29(12):1177–1185. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(90)90042-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crane A. M., Porrino L. J. Adaptation of the quantitative 2-[14C]deoxyglucose method for use in freely moving rats. Brain Res. 1989 Oct 9;499(1):87–92. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(89)91137-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deutch A. Y., Cameron D. S. Pharmacological characterization of dopamine systems in the nucleus accumbens core and shell. Neuroscience. 1992;46(1):49–56. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(92)90007-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Chiara G., Imperato A. Drugs abused by humans preferentially increase synaptic dopamine concentrations in the mesolimbic system of freely moving rats. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1988 Jul;85(14):5274–5278. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.14.5274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Chiara G., North R. A. Neurobiology of opiate abuse. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1992 May;13(5):185–193. doi: 10.1016/0165-6147(92)90062-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Chiara G. On the preferential release of mesolimbic dopamine by amphetamine. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1991 Dec;5(4):243–247. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Chiara G., Tanda G., Frau R., Carboni E. On the preferential release of dopamine in the nucleus accumbens by amphetamine: further evidence obtained by vertically implanted concentric dialysis probes. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1993;112(2-3):398–402. doi: 10.1007/BF02244939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Chiara G. The role of dopamine in drug abuse viewed from the perspective of its role in motivation. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1995 May;38(2):95–137. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(95)01118-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerfen C. R., Baimbridge K. G., Miller J. J. The neostriatal mosaic: compartmental distribution of calcium-binding protein and parvalbumin in the basal ganglia of the rat and monkey. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1985 Dec;82(24):8780–8784. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.24.8780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groenewegen H. J., Russchen F. T. Organization of the efferent projections of the nucleus accumbens to pallidal, hypothalamic, and mesencephalic structures: a tracing and immunohistochemical study in the cat. J Comp Neurol. 1984 Mar 1;223(3):347–367. doi: 10.1002/cne.902230303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heimer L., Zahm D. S., Churchill L., Kalivas P. W., Wohltmann C. Specificity in the projection patterns of accumbal core and shell in the rat. Neuroscience. 1991;41(1):89–125. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(91)90202-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heimer L., de Olmos J., Alheid G. F., Záborszky L. "Perestroika" in the basal forebrain: opening the border between neurology and psychiatry. Prog Brain Res. 1991;87:109–165. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6123(08)63050-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemby S. E., Martin T. J., Co C., Dworkin S. I., Smith J. E. The effects of intravenous heroin administration on extracellular nucleus accumbens dopamine concentrations as determined by in vivo microdialysis. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1995 May;273(2):591–598. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koob G. F. Drugs of abuse: anatomy, pharmacology and function of reward pathways. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1992 May;13(5):177–184. doi: 10.1016/0165-6147(92)90060-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuczenski R., Segal D. S., Aizenstein M. L. Amphetamine, cocaine, and fencamfamine: relationship between locomotor and stereotypy response profiles and caudate and accumbens dopamine dynamics. J Neurosci. 1991 Sep;11(9):2703–2712. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.11-09-02703.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuczenski R., Segal D. S. Differential effects of amphetamine and dopamine uptake blockers (cocaine, nomifensine) on caudate and accumbens dialysate dopamine and 3-methoxytyramine. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1992 Sep;262(3):1085–1094. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pickens R., Harris W. C. Self-administration of d-amphetamine by rats. Psychopharmacologia. 1968;12(2):158–163. doi: 10.1007/BF00401545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pickens R., Thompson T. Cocaine-reinforced behavior in rats: effects of reinforcement magnitude and fixed-ratio size. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1968 May;161(1):122–129. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pontieri F. E., Colangelo V., La Riccia M., Pozzilli C., Passarelli F., Orzi F. Psychostimulant drugs increase glucose utilization in the shell of the rat nucleus accumbens. Neuroreport. 1994 Dec 20;5(18):2561–2564. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199412000-00039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porrino L. J., Domer F. R., Crane A. M., Sokoloff L. Selective alterations in cerebral metabolism within the mesocorticolimbic dopaminergic system produced by acute cocaine administration in rats. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1988 May;1(2):109–118. doi: 10.1016/0893-133x(88)90002-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porrino L. J. Functional consequences of acute cocaine treatment depend on route of administration. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1993;112(2-3):343–351. doi: 10.1007/BF02244931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porrino L. J., Lucignani G., Dow-Edwards D., Sokoloff L. Correlation of dose-dependent effects of acute amphetamine administration on behavior and local cerebral metabolism in rats. Brain Res. 1984 Jul 30;307(1-2):311–320. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(84)90485-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson T. E., Camp D. M. Does amphetamine preferentially increase the extracellular concentration of dopamine in the mesolimbic system of freely moving rats? Neuropsychopharmacology. 1990 Jun;3(3):163–173. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salamone J. D. Complex motor and sensorimotor functions of striatal and accumbens dopamine: involvement in instrumental behavior processes. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1992;107(2-3):160–174. doi: 10.1007/BF02245133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheel-Krüger J. Comparative studies of various amphetamine analogues demonstrating different interactions with the metabolism of the catecholamines in the brain. Eur J Pharmacol. 1971;14(1):47–59. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(71)90121-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voorn P., Gerfen C. R., Groenewegen H. J. Compartmental organization of the ventral striatum of the rat: immunohistochemical distribution of enkephalin, substance P, dopamine, and calcium-binding protein. J Comp Neurol. 1989 Nov 8;289(2):189–201. doi: 10.1002/cne.902890202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weeks J. R., Collins R. J. Changes in morphine self-administration in rats induced by prostaglandin E1 and naloxone. Prostaglandins. 1976 Jul;12(1):11–19. doi: 10.1016/s0090-6980(76)80003-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wise R. A., Bozarth M. A. A psychomotor stimulant theory of addiction. Psychol Rev. 1987 Oct;94(4):469–492. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]