SUMMARY

Pathogens and cellular danger signals activate sensors such as RIG-I and NLRP3 to produce robust immune and inflammatory responses through respective adaptor proteins MAVS and ASC, which harbor essential N-terminal CARD and PYRIN domains, respectively. Here, we show that CARD and PYRIN function as bona fide prions in yeast and their prion forms are inducible by their respective upstream activators. Likewise, a yeast prion domain can functionally replace CARD and PYRIN in mammalian cell signaling. Mutations in MAVS and ASC that disrupt their prion activities in yeast also abrogate their ability to signal in mammalian cells. Furthermore, fibers of recombinant PYRIN can convert ASC into functional polymers capable of activating caspase-1. Remarkably, a conserved fungal NOD-like receptor and prion pair can functionally reconstitute signaling of NLRP3 and ASC PYRINs in mammalian cells. These results indicate that prion-like polymerization is a conserved signal transduction mechanism in innate immunity and inflammation.

INTRODUCTION

The innate immune system is an evolutionarily conserved self-defense mechanism that relies on germline encoded pattern recognition receptors to distinguish “self” from “non-self” signals (Takeuchi and Akira, 2010). While the Toll-like receptors survey the endosomes and extracellular milieu, cyclic GMP-AMP synthase (cGAS) and retinoic acid-induced gene-I (RIG-I)-like receptors (RLRs) detect cytosolic DNA and aberrant RNA, respectively, to trigger a robust innate immune response (Sun et al., 2013; Wu et al., 2013; Yoneyama et al., 2004). RIG-I, upon binding to 5’-triphosphorylated RNA and lysine 63 (K63)-linked polyubiquitin chains, activates the adapter protein MAVS that was recently shown to have biochemical properties of prions (Hou et al., 2011; Zeng et al., 2010). Specifically, after viral infection, MAVS forms detergent-resistant, high molecular weight polymers capable of activating the downstream transcription factors NF-κB and IRF3. Remarkably, active MAVS fibers can catalyze similar biochemical changes in inactive MAVS. These newly converted MAVS molecules gain the ability to activate the downstream signaling cascades.

MAVS is unique as a gain-of-function and beneficial prion. It harbors an N-terminal CARD (MAVSCARD) that serves as its prion domain. Mutations in CARD that abolish MAVS polymerization also prevent virus-induced, RIG-I-dependent IRF3 activation (Liu et al., 2013). CARD belongs to the death domain (DD) superfamily that also includes the DD, DED, and PYRIN subfamilies (Park et al., 2007a). Like CARD, members of the DD superfamily regulate cell signaling through homotypic interactions and the formation of oligomeric complexes.

The inflammasome is another notable DD containing signaling complex, which is activated as a result of cellular infection or damage and is implicated in numerous diseases (Schroder and Tschopp, 2010). ASC is an adapter protein for inflammasome signaling. It is composed of a PYRIN domain (ASCPYD) at the N-terminus and a CARD (ASCCARD) at the C-terminus. ASCPYD interacts with PYRINs of activated upstream proteins such as NLRP3 and AIM2, while ASCCARD then relays the signal downstream by binding to the CARD of pro-caspase-1, leading to caspase-1 activation. Activated caspase-1 then cleaves itself and pro-IL-1β, forming p10 and p17 products, respectively. In response to stimulation, ASC forms high molecular weight oligomers that can be visualized as perinuclear clusters by microscopy (Martinon et al., 2002). However, the molecular composition of the inflammasome and the mechanism of ASC activation remain unclear. Similarly, MAVS and ASC are both death domain containing adaptors that relay signals from multiple upstream sensors to downstream effectors, eventually leading to the secretion of protective cytokines (Figure S1A).

To further understand MAVS prion conversion and to investigate if other DD-containing proteins also possess prion-like properties, we sought to reconstitute the prion properties of MAVSCARD and other DDs in yeast, using the Sup35 based prion assay (Liebman and Chernoff, 2012). Sup35 harbors a low complexity, intrinsically disordered prion domain (NM) and a globular, catalytic domain (Sup35C) that terminates translation. In its prion state, NM forms amyloid like fibers that sequester the Sup35 protein in an insoluble aggregate, resulting in a reduction in translation termination and a corresponding increase in stop codon read-through that is readily visualized phenotypically. The modular nature of the NM and Sup35C domains as well as the availability of phenotypic reporters for Sup35 activity has popularized the Sup35 based yeast prion assay (Alberti et al., 2009; Osherovich et al., 2004).

In this report, we use genetic and biochemical assays to demonstrate that MAVS and ASC form prions in yeast in response to upstream sensors and that their prion conversion is necessary for their immune and inflammatory signaling abilities. We further show that recombinant ASCPYD forms prion-like fibers capable of converting inactive ASC into an active prion form necessary and sufficient for downstream signaling. Finally, we demonstrate that homologous domains of a conserved NOD-like receptor and a bona fide prion from a filamentous fungus can together functionally replace NLRP3 and ASC PYRINs in mammalian inflammasome signaling, suggesting that prion-like polymerization is an evolutionarily conserved mechanism of signal transduction.

RESULTS

MAVSCARD and Sup35NM Functionally Replace Each Other in Yeast and Mammalian Cells

We recently showed that MAVSCARD forms fibers that can convert endogenous MAVS into high molecular weight, SDS-resistant polymers capable of activating IRF3 (Hou et al., 2011). To determine if MAVS has other defining properties of prions, we employed the Sup35 based yeast prion assay. We fused MAVSCARD to Sup35C and constitutively expressed the resulting fusion protein in a yeast strain that lacks endogenous Sup35 and contains a premature stop codon in ADE1, a gene critical for de novo adenine biosynthesis (Figure 1A; Table S1). Through the activity of soluble Sup35C, the nonsense ADE1 mutation blocks the synthesis of functional Ade1, resulting in the accumulation of a red pigment when grown on rich media (¼YPD), and an inability to grow on media lacking adenine (-ade). When Sup35 activity is compromised, as when it forms a prion, the stop codon is read through resulting in the synthesis of full length Ade1, a concomitant loss of the red pigment, and growth on -ade media (Figure S1B).

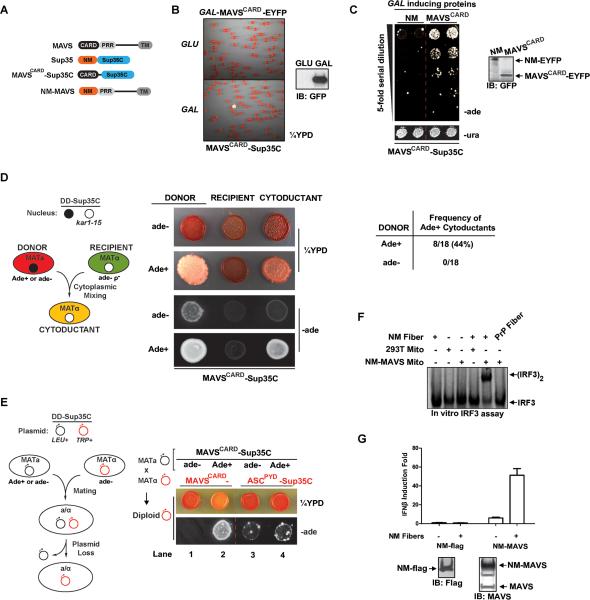

Figure 1. MAVSCARD and Sup35NM Functionally Replace Each Other in Yeast and Mammalian Cells.

(A) Cartoon depictions of MAVS, Sup35, MAVSCARD-Sup35C and NM-MAVS proteins. (B) Cells from a single yeast colony harboring constitutively expressed MAVSCARD-Sup35C and galactose inducible (GAL-)MAVSCARD-EYFP (Ura+) were grown for 48 hr in media containing either galactose (SG-ura) or glucose (SD-ura), followed by plating onto ¼YPD at a density of ~500 cells/plate. In this and subsequent panels, induction of EYFP-tagged protein was monitored by western blotting with a GFP antibody.

(C) Single yeast colonies harboring constitutively expressed MAVSCARD-Sup35C and GAL-NM-EYFP or GAL-MAVSCARD-EYFP (Ura+) were grown in SD-ura for 24 hr to equal density followed by growth in SG-ura for 48 hr. Two colonies of each were plated onto non prion-selective media (SD-ura) and prion-selective, adenine-deficient media (SD-ade) at five-fold serial dilutions. In this and subsequent figures, one dilution on SD-ura is shown as an indicator of equal plating density among the samples. Dotted red line in this and other figures indicates serial dilutions grown non-adjacently on the same plate.

(D) Left: A schematic for the cytoduction experiments. Ade+ or ade- donor strain harboring death domain (DD)-Sup35C fusion (e.g., MAVSCARD-Sup35C) was cytoduced into a ρ− recipient strain expressing the same DD-Sup35C fusion and a kar1 mutation (kar1-15) which prevents nuclear fusion. Haploid cytoductants, containing both parental cytoplasms but only the recipient nucleus, were selected. Middle: Representative single clones of Ade+ or ade- donors, ade-recipients, or resultant cytoductants each expressing MAVSCARD-Sup35C were plated onto ¼YPD and SD-ade. Right: A table showing the frequency of Ade+ cytoductants from Ade+ or ade- MAVSCARD-Sup35C donors.

(E) Left: A schematic for the mating and plasmid shuffle experiments. Ade+ or ade- haploid yeast of mating type a (MATa) expressing DD-Sup35C fusion from a Leu+ plasmid (black circle) were mated with an ade- MATα strain harboring DD-Sup35C on a Trp+ plasmid (red circle), followed by selection for diploids that have lost the original DD-Sup35C Leu+ plasmid. The resultant leu- Trp+ diploids were assessed for the prion phenotype. Right: An ade- or Ade+ MATa strain of MAVSCARD-Sup35C was mated with an ade- MATα strain harboring either MAVSCARD-Sup35C or ASCPYD-Sup35C following the protocol outlined above. Representative single colonies of leu- Trp+ diploids were plated onto ¼YPD and SD-ade. Lanes are numbered as described in the text.

(F) Mitochondrial fractions from parental 293T or those expressing NM-MAVS were incubated with NM or PrP fibers as indicated followed by in vitro IRF3 assay. Dimerization of IRF3 was visualized by autoradiography following native gel electrophoresis.

(G) NM-flag or NM-MAVS was transfected into 293T-IFNβ-luciferase reporter cells. Recombinant NM fibers were added to the culture media 24 hr later and allowed to incubate for additional 24 hr, followed by luciferase reporter assay. Error bar represents standard deviation of triplicates.

See also Figure S1.

The cells expressing MAVSCARD-Sup35C were red on ¼YPD and were unable to grow on -ade media, indicating that the fusion protein was adequately expressed and fully functional. The frequency of prion switching depends on the concentration of the prion protein. Consequently, a defining hallmark of prions is that the prion state can be induced by transient over-expression of the prion protein. To this end, we transformed the MAVSCARD-Sup35C strain with a plasmid driving the expression of MAVSCARD-EYFP from the inducible GAL1 promoter. Following transient expression of MAVSCARD-EYFP in galactose-containing media, we plated the cells to glucose-containing, nonselective media. This treatment produced white and red/white sectored colonies on ¼YPD, indicating a self-perpetuating state that is stable over numerous cell divisions and unlikely to be due to genetic mutations (Figure 1B and S1C). Similarly, when plated to adenine deficient glucose-containing medium (SD-ade), the transient expression of MAVSCARD-EYFP, but not NM-EYFP, produced a high frequency of Ade+ colonies, each derived from a cell that had heritably acquired the ability to synthesize adenine (Figure 1C). We estimated that transient expression of MAVSCARD increased the frequency of Ade+ colonies by ~125 fold.

To determine if the Ade+ phenotype of MAVSCARD-Sup35C yeast is cytoplasmically inherited, we performed a series of cytoduction experiments, in which the cytoplasm but not the nucleus is transferred from one yeast strain (donor) to another (recipient). The recipient contains a kar1 mutation that blocks nuclear fusion. Haploid daughter cells (cytoductants) are subsequently recovered that have lost the donor nucleus but now contain cytoplasm from both parents (Figure 1D). When an Ade+ donor was cytoduced with an ade- recipient (both expressing MAVSCARD-Sup35C), over 40% of the cytoductants were Ade+, indicating that the Ade+ phenotype is inherited cytoplasmically without nuclear contribution (Figure 1D). Cytoduction between two ade- strains uniformly produced ade- cytoductants.

To assess if the Ade+ phenotype is dominant and dependent on MAVSCARD-Sup35C, we performed a series of plasmid shuffle experiments (Figure 1E). First, we mated haploid Ade+ cells of mating type a (MATa) with haploid ade- cells of MATα. The two strains each expressed MAVSCARD-Sup35C from differentially marked plasmids (Leu+ or Trp+). We then assayed Sup35C function in diploids that had lost the original MAVSCARD-Sup35C construct of the Ade+ MATa parent. The resultant leu-, Trp+ diploids retained a pink color and the ability to grow on SD-ade, indicating that the Ade+ phenotype is dominant (Figure 1E, lane 2). As a control, mating between two ade- strains resulted in red cells that did not grow on SD-ade (Figure 1E, lane 1). However, when either Ade+ or ade- MAVSCARD-Sup35C yeast was mated with an adehaploid expressing an unrelated DD-Sup35C fusion (ASCPYD-Sup35C), the resultant diploids that have lost the MAVSCARD-Sup35C plasmid were red with similar background growth on SD-ade, indicating that the Ade+ phenotype requires the continued expression of MAVSCARD-Sup35C. We conclude that MAVSCARD is a bona fide prion protein in yeast and designate its prion state [MAVSCARD+] and its native (prion minus) state [mavscard-], with capitals and brackets denoting genetic dominance and cytoplasmic inheritance, respectively. The [MAVSCARD+] phenotype is similar to that of yeast containing the prion form of WT Sup35, [PSI+] (Figure S1D).

Given that MAVSCARD functionally replaces Sup35NM as a yeast prion, we tested if substituting MAVSCARD with NM (NM-MAVS, Figure 1A) could activate IRF3 in the mammalian system. We have recently described a cell-free system that recapitulates MAVS polymer dependent IRF3 activation, where incubation of MAVSCARD fibers with mitochondria (containing MAVS), along with cytosolic extracts and 35S-IRF3 substrate results in IRF3 dimerization, the hallmark of its activation (Figure S1E). Here, only the incubation of NM fibers with NM-MAVS containing mitochondria resulted in IRF3 dimerization (Figure 1F; Figure S1E). Next, to determine if NM-MAVS could signal in cells, we added NM fibers, which can enter mammalian cells (Ren et al., 2009), to the culture media of 293T-IFNβ-luciferase reporter cells transfected with either NM or NM-MAVS. Luciferase activity assay showed that NM fibers markedly enhanced IFNβ induction in cells expressing NM-MAVS but not in those expressing NM (Figure 1G). Together, these data indicate that NM fibers induce a specific conformational switch in NM-MAVS that is sufficient for downstream IRF3 activation.

MAVSCARD-Sup35C Prion Assay Faithfully Recapitulates RIG-I Dependent MAVS Activation and Reveals Dynamics of MAVSCARD Prion Conversion in Yeast

In mammalian cells, over-expression of the N-terminal tandem CARDs of RIG-I [RIG-I(N)] is sufficient to activate MAVS (Seth et al., 2005). To determine if RIG-I could trigger MAVS prion conversion in yeast, we transiently expressed RIG-I(N) in the MAVSCARD-Sup35C strain. Expression of RIG-I(N) resulted in a high frequency of white colonies on ¼YPD and a ~3000 fold increase in the frequency of Ade+ colonies as compared to expression of NM (Figures 2A and 2B). The much higher frequency of prion conversion induced by RIG-I(N) as compared to MAVSCARD suggests that the physiological upstream sensor is more potent at nucleating MAVSCARD polymerization. Instead of forming self-perpetuating fibers, RIG-I(N) forms a tetramer in the presence of K63 polyubiquitin chains (Jiang et al., 2012). Consistent with RIG-I's role as an upstream prion-nucleating factor rather than a prion itself, transient expression of RIG-I(N) was unable to induce Ade+ colonies in cells harboring RIG-I(N)-Sup35C (Figure S2).

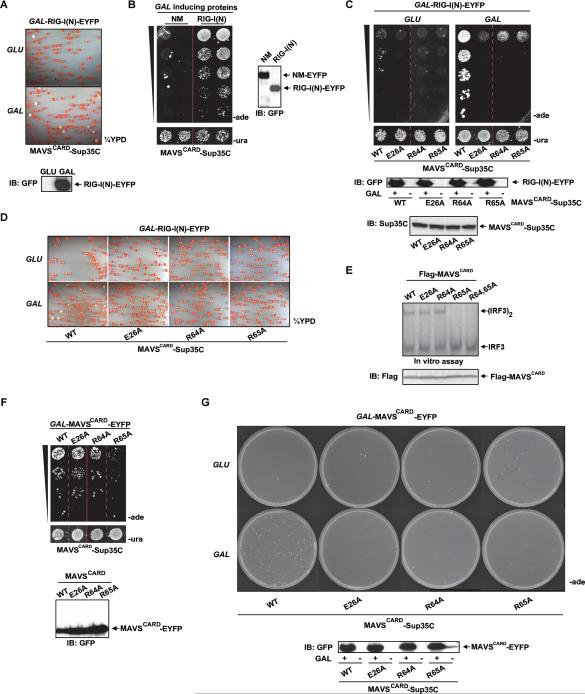

Figure 2. MAVSCARD-Sup35C Prion Assay Faithfully Recapitulates RIG-I Dependent MAVS Activation and Reveals Stepwise Polymerization of MAVSCARD in Yeast.

(A) A single yeast colony harboring constitutively expressed MAVSCARD-Sup35C and GAL-RIG-I(N)-EYFP (Ura+) was grown in SD-ura (top) or SG-ura (bottom) for 48 hr followed by plating onto ¼YPD at a density of 500 cells/plate.

(B) Single yeast colonies harboring MAVSCARD-Sup35C and NM- or RIG-I(N)-EYFP were grown in SD-ura to equal density followed by growth in SG-ura for 48 hr before plating of two independent colonies at five-fold serial dilutions onto SD-ade and SD-ura. The solid red line in this and other figures indicates serial dilutions grown under the same conditions on separate plates in the same experiment.

(C) Similar to (B), except single yeast colonies harbored constitutively expressed WT or mutant MAVSCARD-Sup35C and GAL-RIG-I(N)-EYFP. Expression of MAVSCARD-Sup35C was monitored using a Sup35C antibody.

(D) Similar to (C), except that cells were plated onto ¼YPD at a density of 500 cells/plate.

(E) Mitochondrial fractions from parental 293T cells were incubated at RT with lysates of 293T cells expressing WT or mutant MAVSCARD, followed by in vitro IRF3 assay. Dimerization of IRF3 was visualized by autoradiography following native gel electrophoresis.

(F) Similar to (B), except cells expressed WT or mutant GAL-MAVSCARD-EYFP.

(G) Similar to (C), except cells expressed GAL-MAVSCARD-EYFP and were plated at a density of 50,000 cells per plate.

See also Figure S2.

Recently, we identified a number of conserved MAVSCARD residues that, when mutated to alanine, abolished virus-induced IRF3 activation (Liu et al., 2013). Consistent with their inability to signal in the mammalian system, E26A, R64A, and R65A MAVSCARD-Sup35C were defective in RIG-I(N)-induced prion formation (Figures 2C and 2D). Surprisingly however, when we incubated 293T lysate expressing WT or mutant MAVSCARD with mitochondria from parental 293T cells (Figure S1E, left), only R65A and R64A/R65A MAVSCARD were defective in inducing endogenous MAVS to activate IRF3 in vitro (Figure 2E).

Unlike amorphous protein aggregation, prions polymerize in an ordered process that proceeds through a rate limiting nucleation step followed by rapid, energetically favorable polymerization (Serio et al., 2000). The Sup35 based yeast prion assay can uncouple the effects of prion nucleation, mediated by transient expression of the inducing protein, and polymerization, where prion seeds are perpetuated by the Sup35C fusion protein that is responsible for the phenotypic readout. Consistent with our in vitro assay in Figure 2E, only R65A MAVSCARD failed to induce MAVSCARD-Sup35C prion conversion in yeast (Figures 2F), suggesting that R65A is unable to nucleate WT MAVS prion conversion whereas E26A and R64A have no nucleation defect. However, all three mutants of MAVSCARD-Sup35C were unable to propagate as prions when supplied with prion templates in the form of transiently expressed WT MAVSCARD-EYFP (Figure 2G), suggesting that each of these mutations abrogates MAVS polymerization. These results indicate that MAVS nucleation alone is insufficient to activate the downstream signaling cascades. Rather, MAVS polymerization is required to signal downstream. Thus, as for other prions, MAVSCARD prion formation is a multi-step process comprised of separable nucleation and polymerization steps. Together with our previous report, these results firmly establish MAVS as a bona fide prion and validate the Sup35 based yeast prion assay as an attractive means for identifying and characterizing other prions.

Characterization of ASCPYD as a Prion Domain

To identify other DD superfamily members that may behave as prions, we used the Sup35 system to screen eighteen additional DDs, spanning all four subfamilies (Figure S3A; Table S2). Several of the DD-Sup35C strains exhibited uniform white colors on YPD, indicating a high basal level of stop codon read-through due to insufficient expression or low basal activity of the fusion protein. Of the remaining strains, the one expressing ASCPYD-Sup35C formed predominantly dark red colonies with an appreciable frequency of white colonies (Figure S3B), suggesting that ASCPYD-Sup35C sufficiently rescues WT Sup35 function and also exhibits a strong tendency for prion formation.

To explore the putative prion properties of ASC, we transiently expressed ASCPYD-EYFP in a red ASCPYD-Sup35C isolate. Remarkably, this increased the appearance of Ade+ colonies and both white and white/red sectored colonies on ¼YPD, suggesting that ASCPYD behaves as a functional prion domain in yeast (Figure 3A, S3C, S3D). To determine if ASC prion conversion can be induced by upstream sensors, we investigated the prion conversion of ASCPYD-Sup35C upon transient expression of NLRP3PYD or AIM2, which is known to activate the inflammasome in mammalian cells. Transient NLRP3PYD or AIM2 expression indeed increased the frequency of white and Ade+ colonies (Figure 3B and 3C). Interestingly, the effect from these proteins was much stronger than had been observed for ASCPYD induced prion conversion. Moreover, AIM2 was unable to induce prion formation in ASCCARD-Sup35C strains, consistent with ASC activation through ASCPYD and AIM2PYD interaction (Figure 3D). IFI16 and IFI204 also harbor N-terminal PYRINs; however, they were unable to induce prion switching of ASCPYD (Figure S3E). Similarly, a strain harboring NLRP3PYD-Sup35C was unable to undergo prion conversion following ASCPYD, NLRP3PYD, or AIM2 expression (Figure S3F). Together, these results demonstrate that the physiological upstream signaling proteins of ASCPYD nucleate prion formation more potently than the prion domain itself, but are not prions themselves.

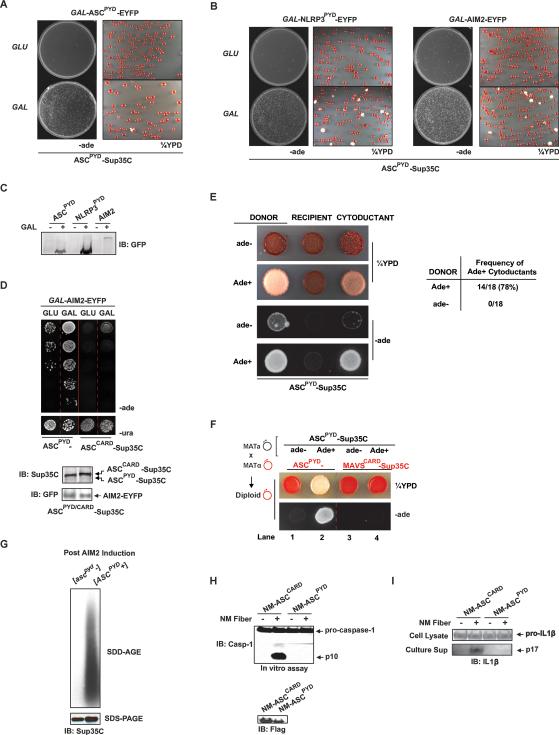

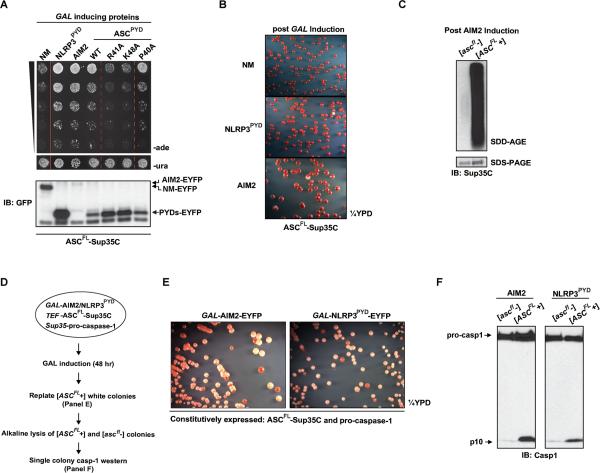

Figure 3. ASCPYD Behaves as a Prion in Yeast and can be Functionally Substituted by the NM Prion Domain in Mammalian Cells.

(A) A single yeast colony harboring constitutively expressed ASCPYD-Sup35C and GAL-ASCPYD-EYFP (Ura+) was grown in SD-ura or SG-ura for two days followed by plating onto SD-ade and ¼YPD at a density of 100,000 and 500 cells/plate, respectively.

(B) Similar to (A), except that NLRP3PYD or AIM2, instead of ASCPYD, was used to induce ASCPYD prion formation.

(C) GAL inducible protein expression in (A) and (B) is monitored by immunoblotting with a GFP antibody.

(D) Single yeast colonies with constitutively expressed ASCPYD-Sup35C or ASCCARD-Sup35C and GAL-AIM2-EYFP were grown in SD-ura or SG-ura for two days followed by plating of five-fold serial dilutions onto SD-ade and SD-ura. One serial dilution on SD-ura is shown.

(E) Left: Following cytoduction as depicted in Figure 1D, representative single clones of Ade+ or ade- donors, ade- recipients, and resultant cytoductants each expressing ASCPYD-Sup35C were plated onto ¼YPD or SD-ade. Right: A table showing the frequency of Ade+ cytoductants from Ade+ or ade- donors harboring ASCPYD-Sup35C.

(F) Mating between an ade- or Ade+ MATa strain with an ade- MATα strain each harboring differentially marked DD-Sup35C was carried out as depicted in Figure 1E. Representative resultant diploid leu- Trp+ single colonies were plated onto ¼YPD or SD-ade.

(G) Following induction by AIM2 expression, colonies with soluble or prion form of ASCPYD ([ascpyd-] or [ASCPYD+], respectively) were subjected to SDD-AGE analysis for SDS-resistant polymers and SDS-PAGE for expression levels.

(H) Cell lysates from NM-ASCPYD or NM-ASCCARD transfected 293T cells were incubated with NM fibers and lysates containing pro-caspase-1 followed by western analysis for caspase-1 activation.

(I) NM fibers were added to the culture media of NM-ASCPYD or NM- ASCCARD transfected 293T cells stably expressing pro-caspase-1 and pro-IL1β, followed by immunoblotting analysis of secreted IL1β (p17) and pro-IL1β.

See also Figure S3.

Next, to investigate the mode of inheritance of the Ade+ phenotype, we performed cytoduction experiments as described in Figure 1D with strains harboring ASCPYD-Sup35C. Ade+ but not ade- donor strains produced haploid cytoductants that were Ade+ and white on ¼YPD, indicating that the Ade+ phenotype of ASCPYD-Sup35C is cytoplasmically inherited (Figure 3E). Furthermore, mating between Ade+ and ade- yeast followed by a plasmid shuffle as described in Figure 1E resulted in uniformly Ade+ diploids, and the Ade+ phenotype required the continued presence of the ASCPYD-Sup35C plasmid (Figure 3F, lanes 2 and 4). No Ade+ yeast were observed after crossing two ade- strains (lane 1). These results indicate that the Ade+ phenotype of ASCPYD-Sup35C is dominant, requires the continued expression of ASCPYD-Sup35C, and cannot be transmitted to MAVSCARD. Taken together, we conclude that ASCPYD acquires a prion state in yeast, which we hereafter designate [ASCPYD+]. To confirm that ASCPYD had undergone a conformational switch in the [ASCPYD+] cells, we performed semi-denaturing detergent-agarose gel electrophoresis (SDD-AGE), a technique commonly used to detect SDS-resistant polymers of prion proteins (Halfmann and Lindquist, 2008). We have previously employed the SDD-AGE assay to show that activated MAVS forms high molecular weight polymers (Hou et al., 2011). Similarly, SDD-AGE analysis revealed that [ASCPYD+], but not [ascpyd-] cells, harbor SDS-resistant polymers of ASCPYD-Sup35C, as detected with a Sup35C antibody (Figure 3G).

Next, we tested whether the NM prion domain from Sup35 could functionally replace ASCPYD in activating caspase-1. Together with lysate from 293T cells stably expressing pro-caspase-1 (293T+pro-caspase-1) as the substrate, incubation of recombinant NM fibers with lysate from 293T cells expressing NM-ASCCARD, but not NM-ASCPYD fusion, resulted in caspase-1 activationin vitro (Figure 3H). Moreover, the addition of NM fibers to 293T cells stably expressing procaspase-1, pro-IL-1β, and NM-ASCCARD resulted in the secretion of active IL-1β, p17 (Figure 3I). In contrast, the cells expressing NM-ASCPYD did not activate the inflammasome. Hence, a yeast prion domain can functionally replace ASCPYD in inflammasome signaling. From these results, we conclude that ASC undergoes a prion-like switch to activate downstream signaling.

ASCPYD Mutants That Disrupt Its Prion Activity Are Defective in Inflammatory Signaling

ASCPYD shares the same overall six α-helical bundle structure that is the hallmark of the DD superfamily (Ferrao and Wu, 2012). Structural analysis of ASCPYD and NLRP3PYD revealed a strong dipole moment created by adjacent positively and negatively charged surface patches, suggesting that electrostatic interactions may play a role in PYRIN-PRYIN interaction (Liepinsh et al., 2003). Mutations of a number of conserved, surface exposed ASCPYD residues have been shown to be defective in binding to ASC and NLRP3, without affecting protein folding as observed by NMR (Vajjhala et al., 2012). To investigate the consequence of ASC prion formation on its signaling abilities, we tested mutants at several conserved charged and hydrophobic residues (R41A, D48A, and P40A) in our yeast prion assay and for their ability to generate mature caspase-1 and IL-1β in mammalian cells. In yeast, transient NLRP3PYD expression led to the prion conversion of WT and P40A ASCPYD, but not R41A or D48A ASCPYD (Figure 4A), suggesting ASC R41A and D48A to be defective in inflammasome signaling. In 293T cells, The NLRP3 inflammasome pathway has been reconstituted through the exogenous expression of NLRP3, ASC, and pro-caspase-1, components not normally expressed in 293T cells (Agostini et al., 2004). To test the signal dependent activation of ASC in cells, we transfected ASC WT or mutants in 293T cells stably expressing NLRP3, pro-caspase-1, and pro-IL-1β, and then subjected the cells to a time course of treatment with Nigericin, a chemical known to strongly activate NLRP3. Inflammasome activation was monitored through the cleavage of pro-caspase-1 and the secretion of caspase-1 (p10) and IL-1β (p17) into the culture supernatant. Consistent with NLRP3PYD dependent prion conversion in yeast, we observed caspase-1 activation and secretion of p10 and p17 only in ASC WT or P40A expressing cells, while ASC R41A and D48A were defective (Figure 4B).

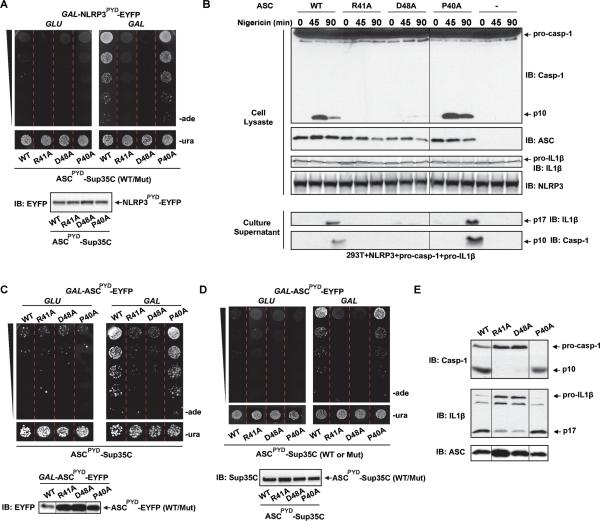

Figure 4. ASC Mutants Defective in Prion Formation Are Defective in Inflammasome Signaling.

(A) Individual yeast colonies constitutively expressing WT or mutant ASCPYD-Sup35C and GAL-NLRP3PYD-EYFP were grown in SD-ura or SG-ura for two days, followed by plating of five-fold serial dilutions onto SD-ura and SD-ade.

(B) Nigericin was added to ASC WT or mutant transfected 293T cells stably expressing NLRP3, pro-caspase-1, and pro-IL-1β, followed by western blot analysis of cell lysates for caspase-1 processing and of culture supernatants for active caspase-1 (p10) and IL-1β (p17) secretion.

(C) Similar to (A), except that WT or mutant ASCPYD, instead of NLRP3PYD, was used to induce ASCPYD prion conversion.

(D) Individual colonies constitutively expressing WT or mutant ASCPYD-Sup35C and WT GAL-ASCPYD-EYFP were treated as in (A).

(E) Lysates of 293T cells expressing WT or mutant ASC were incubated with pro-caspase-1 and pro-IL-1β containing cell extracts, followed by analysis of caspase-1 and IL-1β cleavage by western blotting. Irrelevant lanes were removed for clarity.

To investigate the mechanism of the observed signaling defect, we tested homotypic interactions between the WT and mutant ASCPYDs, which may be different from its interactions with PYRINs of upstream sensors. To this end, we first examined whether the expression of mutant ASCPYD could induce prion switching in WT ASCPYD-Sup35C cells. Conversely, we also tested whether WT ASCPYD could induce prion conversion in cells containing mutant ASCPYD-Sup35C. Interestingly, we found that the mutants behaved similarly in both assays. Namely, ASCPYD R41A and D48A could neither induce prion conversion of WT ASCPYD-Sup35C nor could they be induced to form prions themselves (Figures 4C and 4D). P40A behaved similarly to the WT protein in both assays. These results suggest that as a part of their respective positive and negative patches, R41 and D48 mediate essential interactions necessary for both the nucleation and polymerization of ASC.

ASC activates caspase-1 in vitro when cells expressing both proteins are lysed in a low salt buffer (Martinon et al., 2002). Taking advantage of this ASC-dependent caspase-1 activity assay, we transiently expressed ASC WT, R41A, D48A, and P40A in 293T cells. Lysates from 293T cells expressing ASC and those stably expressing pro-caspase-1 and pro-IL-1β were incubated at 30°C for 45 min. Western blot analysis for active subunits of caspase-1 (p10) and IL-1β (p17) indicated that both ASC WT and P40A robustly activated caspase-1 and IL-1β in vitro, whereas the R41A and D48A mutants that were defective in prion formation in yeast were also defective in activating caspase-1 and IL-1β (Figure 4E). Collectively, these data demonstrate that ASC mutants unable to form self-perpetuating prions in yeast are also incapable of activating the inflammasome, suggesting that prion formation is necessary for ASC activity.

Reconstitution of Inflammasome Signaling in Yeast Reveals Caspase-1 Activation Only in Colonies with ASC Prions

Next, we generated a strain of yeast expressing full-length ASC (ASCFL)-Sup35C in place of endogenous Sup35, and tested for ASCFL prion conversion after transient expression of AIM2, NLRP3PYD, and WT or mutant ASCPYD (Figure S4A). AIM2 and NLRP3PYD induced a >200-fold increase in Ade+ colonies on SD-ade and the appearance of white colonies on ¼YPD (Figures 5A and 5B). Moreover, ASCPYD mutants that were defective in prion formation were also defective in the context of full-length ASC (Figure 5A; S4B). SDD-AGE analysis revealed that ASCFL-Sup35C had acquired SDS-resistant polymers in the Ade+ isolates (designated [ASCFL+]), but not in the ade- isolates ([ascfl-]) (Figure 5C). These results indicate that AIM2 and NLRP3 induced ASCFL to convert to a self-perpetuating prion form.

Figure 5. Reconstitution of Inflammasome Signaling in Yeast Reveals Caspase-1 Activation Only in Colonies Containing ASC Prions.

(A) Single colonies with constitutively expressed ASCFL-Sup35C and GAL inducible NM, NLRP3PYD, AIM2, WT or mutant ASCPYD were grown to similar density in SD-ura, followed by incubation in SG-ura for two days. Five-fold serial dilutions were then plated onto SD-ade and SD-ura.

(B) Similar to (A) except that cells were plated to ¼YPD at 500 cells/plate.

(C) Following induction of Ade+ by AIM2 expression, colonies with soluble or prion form of ASCFL-Sup35C ([ascfl-] or [ASCFL+], respectively) were subjected to SDD-AGE analysis for SDS-resistant aggregates and SDS-PAGE for expression levels.

(D-F) Schematic for the reconstitution of inflammasome signaling in yeast (D). Yeasts expressing AIM2- or NLRP3PYD-EYFP from a GAL inducible promoter (Ura+), ASCFL-Sup35C from the constitutive TEF promoter, and pro-caspase-1 from the constitutive SUP35 promoter were grown in galactose containing media for 2 days. The resultant [ASCFL+] colonies were re-streaked onto ¼YPD (E), from which individual [ascfl-] or [ASCFL+] colonies were lysed and subjected to western analysis for caspase-1 activation (F).

See also Figure S4.

We then applied our phenotypic assay to test if caspase-1 and NLRC4, which harbor N-terminal CARDs but no PYRIN domains, could induce ASC prion conversion. As an important inflammasome sensor for bacterial flagellin and type III secretion systems, NLRC4 can directly activate caspase-1, but this activity is markedly enhanced in the presence of ASC (Broz et al., 2010). When expressed in yeast, a C284A active site mutant caspase-1 was unable to induce ASC (PYRIN, CARD, or full length)-Sup35C yeast to form Ade+ colonies (Figure S4C). However, expression of NLRC4CARD induced ASCFL-Sup35C but not ASCPYD- or ASCCARD-Sup35C prion conversion, and this effect was abolished in yeast harboring ASCFL-Sup35C R41A or D48A polymerization mutants (Figure S4D). These results suggest that NLRC4CARD is able to switch ASCFL into a prion through CARD-CARD interactions, but this conversion is strictly dependent on ASCPYD mediated polymerization. Despite its ability to also interact with ASCCARD, caspase-1 cannot induce ASCFL polymerization.

ASCFL-Sup35C can be used to reconstitute inflammasome signaling in 293T cells, suggesting that the protein retains the inflammasome signaling activity of WT ASC (Figure S4E). Next, to reconstitute caspase-1 activation in yeast, cells harboring ASCFL-Sup35C were transformed with constitutively expressed pro-caspase-1 along with galactose-inducible AIM2 or NLRP3PYD (Figure 5D). Transient expression of either AIM2 or NLRP3PYD led to the appearance of white colonies on ¼YPD similar to those observed in yeast without caspase-1 (data not shown). Further passaging of these white colonies revealed an appreciable rate of switching back to the red phenotype, indicative of a bistable, epigenetically inherited trait (Figure 5E). We then used a colony lysis procedure to assess caspase-1 activation in individual colonies (Kushnirov, 2000). Strikingly, we observed pro-caspase-1 cleavage only in [ASCFL+] but not [ascfl-] colonies, despite their having originated from the same [ASCFL+] colony (Figure 5F). Altogether, these results strongly suggest that ASC prion formation and propagation is necessary and sufficient for downstream signaling.

Recombinant ASCPYD Fibers Convert Inactive ASC into a High Molecular Weight Form Capable of Downstream Signaling

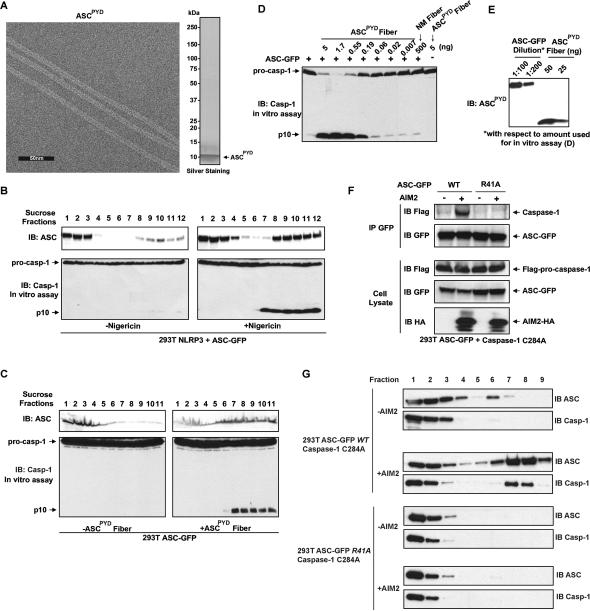

Mammalian PrP and yeast prions typically adopt fibrous structures that perpetuate protein-based forms of inheritance (Toyama and Weissman, 2011). To investigate whether the prion domain of ASC exhibits similar properties, ASCPYD (N1-90) was expressed in E. coli. and purified under native conditions to apparent homogeneity. Negative-stain electron microscopy analysis of the protein revealed that ASCPYD assembled into fibers with an electron poor center, suggestive of symmetry about a central axis (Figure 6A).

Figure 6. Preformed ASCPYD Fibers Convert Inactive ASC into an Active High Molecular Weight Form Capable of Downstream Signaling.

(A) Electron microscopy of negatively stained recombinant ASCPYD protein.

(B) 293T cells stably expressing NLRP3 and ASCFL-GFP were fractionated on a 20-60% sucrose gradient cushion before and after Nigericin treatment. Individual fractions were western blotted with an ASC specific antibody (top) or incubated with pro-caspase1 containing cell extract, followed by western analysis of caspase-1 activation.

(C) Lysate from 293T cells stably expressing ASCFL-GFP were incubated at 30°C for 30 min with or without ASCPYD fibers, followed by the same analysis as in (B).

(D) Lysate from 293T cells stably expressing ASCFL-GFP were incubated at 30°C for 60 min with different amounts of ASCPYD fibers or NM fibers as indicated, along with pro-caspase-1 containing cell extract, followed by western blot analysis for caspase-1 activation.

(E) Dilutions of lysate of 293T cells stably expressing ASCFL-GFP as in (D) was quantitatively compared to different amounts of ASCPYD fibers by western blotting with an antibody specific to ASCPYD.

(F) 293T cells stably expressing flag-caspase-1 C284A and ASC-GFP WT or R41A were transfected with an AIM2 expression plasmid or mock treated. ASC was immunoprecipitated with a GFP antibody and then co-immunoprecipitated flag-caspase-1 was immunoblotted with a flag antibody.

(G) Lysate from (F) was fractionated on a 20-60% sucrose gradient cushion followed by immunoblot analysis of each fraction with indicated antibodies.

See also Figure S5.

The defining property of prions is an ability to convert native species of the protein into a polymerized, infectious form (Prusiner, 1998). To determine if ASCPYD fibers can induce a similar conversion of native ASC protein, we first sought conditions that would separate polymerized and native forms of ASC. Using a sucrose density gradient, we fractionated lysate from 293T cells stably expressing NLRP3 and ASCFL-GFP before and after Nigericin treatment. Nigericin treatment resulted in the formation of large ASC particles that sedimented to the bottom of a 20%-60% sucrose gradient (Figure 6B, top). When incubated with lysate from 293T cells stably expressing pro-caspase-1, only the high molecular weight (MW) fractions were capable of activating caspase-1, suggesting that the active form of ASC consists of large ASC particles (Figure 6B, bottom). We then incubated a sub-stoichiometric amount of ASCPYD fibers with ASCFL-GFP (~1:10,000 molar ratio) and observed a notable shift of ASC from a low MW to a high MW form that also sedimented to the bottom of the sucrose gradient (Figure 6C, top). An in vitro assay revealed that only the high MW fractions were capable of activating caspase-1 (Figure 6C, bottom). These results indicate that ASCPYD fibers converted native ASC into an active, self-perpetuating, and high molecular weight polymer similar to the one induced by activated NLRP3 in vivo.

To further demonstrate the infectious properties of ASCPYD fibers, we incubated sub-stoichiometric amounts of ASCPYD fibers with lysate from 293T cells expressing ASCFL-GFP, which is not active by itself, at 30°C for 60 min. All reactions were supplemented with lysate from 293T cells stably expressing pro-caspase-1 as the substrate. Western blot analysis revealed that only the combination of ASCPYD fibers with ASCFL-GFP, but not either one alone, resulted in caspase-1 activation (Figure 6D and 6E). Titration experiments showed that incubation of less than 0.2 ng of ASCPYD fibers with ~5 μg of ASCFL-GFP led to detectable cleavage of pro-caspase-1. In contrast, incubation of 500 ng of NM fibers with ~5 μg ASCFL-GFP failed to activate caspase-1. Taken together, these results suggest that a catalytic and self-perpetuating polymerization of ASC governs inflammasome activation.

To examine the consequence of ASC polymerization on downstream signaling, we probed the interaction between ASC and pro-caspase-1 following AIM2 transfection. In lysate from 293T cells stably expressing flag-caspase-1 C284A and ASC-GFP WT or R41A, GFP immunoprecipitation revealed that only ASC-GFP WT but not R41A was able to interact with pro-caspase-1 in an AIM2 dependent manner (Figure 6F). Furthermore, sucrose gradient analysis indicated that following AIM2 stimulation, only ASC-GFP WT, but not R41A, formed high molecular weight particles, which recruited pro-caspase-1, suggesting ASC polymerization is necessary for pro-caspase-1 recruitment (Figure 6G).

A Conserved Fungal Pattern Recognition Receptor and Death Inducing Prion Functionally Replace NLRP3PYD and ASCPYD in Inflammasome Signaling

In addition to Sup35, there are a number of other well characterized fungal prions, of which HET-s from the filamentous fungus Podospora anserina shares notable similarities with MAVS and ASC. Unlike yeast prions, the prion form of HET-s functions strictly in a gain-of-function manner that induces cell death. Also unlike other yeast prions, it does not require Hsp104 and the prion fibers fail to stain with the amyloid-binding dye Thioflavin T (ThT) (Saupe, 2011). Similarly, MAVS and ASC also switch into gain-of-function prions which propagate independently of Hsp104 in yeast (Figure S5A). The recombinant fibers of their prion domains also do not stain with ThT, suggesting they are not prototypical β-amyloids (Figure S5B).

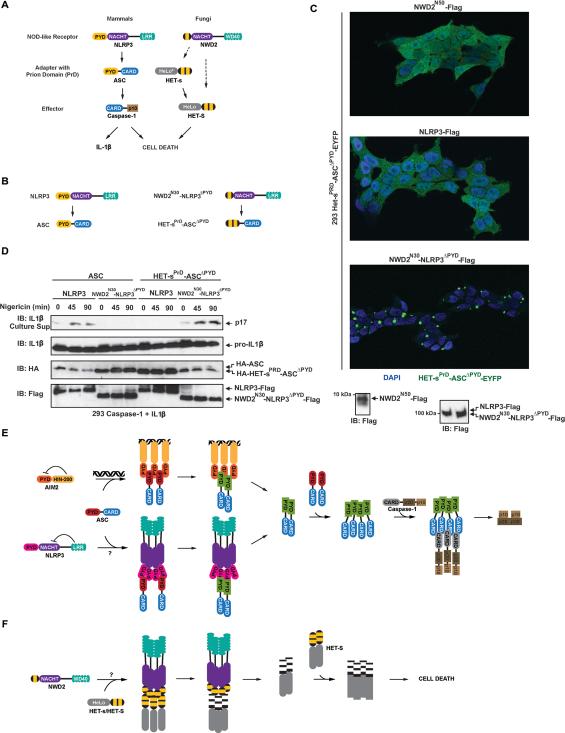

In filamentous fungi, spontaneous cell fusion leads to cell death only if one partner expresses HET-S, and the other harbors the prion form of HET-s ([HET-s]), an allelic variant of HET-S that shares the same prion domain. Specifically, upon cell fusion, [HET-s] templates prion conversion of HET-S, which leads to a conformational change in the HET-S HeLo domain that converts it into a pore-forming toxin (Seuring et al., 2012). However, in the presence of soluble (non-prion) HET-s, HET-S does not cause cell death. The hypothesis that HET-s/S serves host defense functions is supported by a recent bioinformatics analysis which discovered that NWD2, encoded by a gene adjacent to the HET-s/S locus, closely resembles mammalian NOD-like receptors (NLR) such as NLRP3, and may function as a signaling partner of HET-s/S (Daskalov et al., 2012). Similar to NOD-like receptors, NWD2 harbors a C-terminal WD40 repeat, a middle NACHT (or nucleotide-binding oligomerization) domain, and an N-terminal domain predicted to homologous to the Het-s/S prion domain. Overall, the fungal NWD2 and HET-s pair is strikingly similar to mammalian NLRP3 and ASC, both in terms of organization and function (Figure 7A). To determine if NWD2 can induce HET-s polymerization, and if the NWD2/HET-s pair is a possible fungal counterpart to NLRP3 and ASC, we tested if the NWD2 N-terminal domain (NWD2N30) and HET-s prion domain (HET-sPrD) can reconstitute inflammasome signaling (Figure 7B; Table S3). After replacing ASCPYD with HET-sPrD, we stably expressed the fusion protein with a C-terminal EYFP tag in 293T cells. We observed that HET-sPrD-ASCΔPYD-EYFP was distributed diffusely throughout the cell. The localization pattern did not change with the co-expression of NWD2N50 (to facilitate western blot analysis) or NLRP3 (Figure 7C). However, co-expression of NWD2N30-NLRP3ΔPYD (NLRP3PYD replaced by NWD2N30) resulted in a striking redistribution of HET-sPrD-ASCΔPYD-EYFP to form a single perinuclear focus in almost every cell, reminiscent of the previously described ASC foci (Figure 7C). These results suggest that NWD2N30 is necessary but not sufficient for HET-sPrD-ASCΔPYD prion conversion, and suggest that the NACHT domain of NWD2 is required for its oligomerization and downstream signaling, similar to the current model for NLRP3 activation. Next, we generated cell lines stably expressing NLRP3 or NWD2N30-NLRP3ΔPYD along with pro-capase-1 and pro-IL1β and transfected either WT ASC or HET-sPrD-ASCΔPYD into the two cell lines. Nigericin treatment revealed that mature IL1β (p17) was only secreted in cells expressing WT NLRP3 and ASC or NWD2N30-NLRP3ΔPYD and HET-sPrD-ASCΔPYD, indicating that each receptor specifically interacts with its cognate prion (Figure 7D). Together, these results suggest that fungi possess a programmed cell death pathway that is mechanistically similar to those in mammals (Figure 7E; 7F). Furthermore, the regulated conversion of prion domain containing proteins (Het-s/S and ASC) into their prion forms by pattern recognition receptors (e.g., NWD2 and NLRP3) is a signal transduction mechanism conserved from fungi to mammals.

Figure 7. Conserved Fungal Pattern Recognition Receptor and Death Inducing Prion Functionally Replace NLRP3PYD and ASCPYD in Inflammasome Signaling.

(A) Cartoon representations of the mammalian NLRP3 inflammasome signaling and fungal NWD2 signaling pathways. Dotted arrow indicates an unconfirmed potential signaling interaction. The predicted HET-sPrD fold of NWD2 N-terminal domain is indicated using a yellow stripe, whereas HET-sPrD harbors two such motifs in tandem. Asterisk indicates inactive HeLo domain.

(B) Cartoon representations of fusion proteins between NWD2/HET-s and NLRP3/ASC.

(C) Confocal microscopy images of 293T cells stably expressing HET-sPrD-ASCΔPYD-EYFP and transfected NWD2N50, NLRP3, or NWD2N30-NLRP3ΔPYD as indicated on the top of each image. (D) 293T cells stably expressing NLRP3 or NWD2N30-NLRP3ΔPYD along with pro-caspase-1 and pro-IL1β were transfected with either WT ASC or HET-sPrD-ASCΔPYD. Following Nigericin treatment, secretion of mature IL1β and expression of indicated proteins were analyzed by western blotting.

(E) Model for ASC-dependent inflammasome signaling. See text.

(F) Model for NWD2 mediated HET-S activation. See text.

See also Figure S6.

DISCUSSION

In this report, we provide biochemical and genetic evidence demonstrating that MAVS and ASC exhibit hallmarks of prions in cells and in vitro, and prion conversion was inducible by their respective upstream signaling proteins (Figure 7E and Figure S6). Based on previously published results and those presented here, we propose the following model for ASC mediated inflammasome signaling: (1) Stimulation of NLRP3 or AIM2 induces a conformational change that results in the oligomerization or close apposition of their individual PYRIN domains. (2) These oligomers, through PYRIN-PYRIN interactions, then recruit multiple ASC proteins resulting in prion nucleation, which is otherwise prevented from occurring spontaneously due to a high-energy barrier. (3) ASC prions then rapidly template other ASC molecules resulting in the formation of large polymers. (4) Through CARD-CARD interactions, the ASC polymers recruit multiple caspase-1 molecules, bringing them into close proximity to induce their auto-cleavage and activation (Figure 7E).

The mechanism of NWD2 mediated HET-s/S activation in fungi likely resembles that of NLRP3 mediated ASC and caspase-1 activation in mammals (Figure 7F). Following binding of its WD40 repeats to a putative ligand, NWD2 oligomerization through its NACHT domain induces its N-terminal region to form a β-solenoid fold, which in turn templates HET-S into a prion form that converts the HeLo domain into a pore-forming toxin. Alternatively, in cells expressing the allelic variant HET-s, NWD2 activation induces stable prion formation because HET-s contains an inactive HeLo domain, resulting in a decoupling of prion formation from cell death. Nevertheless, when [HET-s] cells fuse with cells expressing HET-S, the prion then templates HET-S into the toxic form, leading to death of the fused cell.

Prion-like Polymerization Is a Sensitive and Robust Mechanism of Cell Signaling

A self-perpetuating mechanism of signal amplification ensures an ultrasensitive response. This mechanism is in line with our previous estimate that as few as 20 viral RNA molecules can activate the RIG-I antiviral signaling cascade (Zeng et al., 2010). Our finding of the prion-like polymerization of ASC provides a mechanism of sensitive inflammatory and cell death response to certain thresholds of noxious agents. The existence of other NLR and prion protein pairs across the fungal kingdom suggests an evolutionary conserved mechanism of signal transduction (Daskalov et al., 2012). In addition, recent studies have indicated that proteins in necrosis signaling and NF-κB activation also form large oligomers or even fibers (Li et al., 2012; Qiao et al., 2013; Sun et al., 2004).

The properties of MAVS and ASC distinguish them from non-prion polymer-forming proteins. The soluble forms of prion proteins are energetically less stable than their corresponding polymeric forms, and are separated from these forms merely by the high energy of nucleation. Once nucleation has been achieved (i.e. through RIG-I or NLRP3 activation), energetically downhill and thus irreversible polymerization ensues. The prion states subsequently perpetuate independently of the nucleating factors. Hence, a population is characterized by a bi-modal distribution of cells that each contains either the native or prion form of the protein. In contrast, polymerization of non-prion proteins is dynamic and reversible, and the distribution between soluble and polymeric forms is typically regulated by changes in their relative stabilities. The polymerization of actin and tubulin, for example, are each regulated by nucleotide (ATP and GTP, respectively) binding and hydrolysis. Here, the soluble and polymerized forms of a protein are uniformly distributed within an individual cell and a population.

Likewise, not all proteins that form oligomers are capable of forming self-perpetuating polymers. For example, in Toll-like receptor signaling, the adapter MyD88 forms a finite but ordered helical structure known as the Myddosome that includes the protein kinases IRAK4 and IRAK2 (Lin et al., 2010). For caspase-2 activation, upstream proteins PIDD and RAIDD also form a fixed complex named the Piddosome that is composed of seven RAIDD DDs and five PIDD DDs, which then recruit and activate caspase-2 (Park et al., 2007b). The structural and biophysical differences that cause some DD superfamily members to form open-ended polymers and others to form limited oligomers remain to be elucidated.

Unique Features of MAVS and ASC as Prion-like Proteins

Since the “prion hypothesis” was first proposed more than two decades ago, we have come to understand prions not only as causative agents of debilitating diseases, but also as potentially adaptive mechanisms for phenotypic diversification and information storage (Holmes et al., 2013; Prusiner, 1982; Si et al., 2010; True and Lindquist, 2000). However, prior to the discovery of MAVS as a prion, beneficial prions were not known to exist in mammals, where the first prion was discovered.

Here we show that MAVS and ASC are two mammalian proteins capable of switching into functional prions, which differ from previously described prions in several important aspects. First, the prion domains of both proteins are neither intrinsically disordered nor rich in Q and N amino acids. Rather, they adopt well-folded six α-helical bundle structures (Liepinsh et al., 2003; Potter et al., 2008). Secondly, while most prions display loss-of-function phenotypes, the prion forms of MAVS and ASC signal in a gain-of-function manner. Mutations that abolish their prion activities also abrogate their biological functions. Thirdly, nearly all previously described prion proteins stochastically acquire their prion forms. In contrast, the nucleation of MAVS and ASC prions is tightly regulated, contingent on heterotypic interactions with upstream protein sensors. Lastly, other mammalian prion-like proteins described to date reside in post-mitotic or rarely dividing neurons or myocytes. Remarkably, the kinetics of MAVS and ASC prion propagation is sufficient to sustain the prion state in rapidly dividing yeast cells. Despite these unusual features, MAVSCARD and ASCPYD exhibit the cardinal hallmarks of prions, including irreversible conversion to stable filamentous structures, cytoplasmic multigenerational inheritance, and most importantly, an ability to template naïve molecules of the same protein into self-perpetuating conformations. For both MAVS and ASC, the tight regulation of nucleation followed by efficient polymerization produces a highly sensitive and robust ‘digital’ response to harmful insults. It is likely that signal transduction through prion-like switches is also deployed in other biological pathways.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Yeast Prion Assays

Strains constitutively expressing the indicated DD-Sup35C fusions were transformed with plasmids encoding DD-, RIG-I(N)-, NLRP3PYD-, AIM2-, or NLRC4CARD-EYFP fusions driven from a GAL1 promoter. Selected individual colonies (usually in triplicates or quadruplicates) were then grown to confluency in SD-ura media, followed by washing 3 times in water to remove residual glucose. Cells were then resuspended in either SD-ura (no induction) or SG-ura (induction) for two days before being plated as indicated. After growth at 30°C for 2-3 days, ¼YPD plates were moved to 4°C overnight and photographed the following day. SD-ade and SD-ura plates were photographed after 3-6 days of incubation at 30°C.

In vitro ASC Activity Assay

293T cells transfected with indicated pcDNA3-ASC WT or mutant plasmids were lysed in buffer D (see Supplemental Procedures for buffer compositions) and centrifuged at 20,000g for 15 min. ~50μg of the supernatant (S20) was mixed with 20μg of lysate from 293T cells stably expressing pro-caspase-1 and pro-IL-1β in buffer D and incubated at 30°C for the indicated time. Indicated amounts of ASCPYD or NM fibers were incubated with ~50μg of lysate (S20) from 293T cells stably expressing ASC-GFP and 20μg of S20 from 293T cells stably expressing procaspase-1 in buffer D in a final volume of 11μl at 30°C for 60 min.

Inflammasome Reconstitution Assay in Cells

Approximately 18 hr after transfection of 200ng of ASC WT or mutant into 293T cells stably expressing flag-NLRP3, pro-caspase-1, and pro-IL-1β-flag in a 12-well plate, 10μM Nigericin was added to culture media for 45 or 90 min. The culture supernatant was concentrated using a 5kD filter followed by SDS-PAGE analysis. Cells were lysed in buffer E followed by centrifugation at 500g. The supernatant was subjected to SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting analysis.

Supplementary Material

Article highlight.

MAVS and ASC exhibit hallmarks of prions in yeast and mammalian cells

The prion forms of MAVS and ASC activate downstream signaling

Mutations that impair MAVS and ASC prion formation abolish their functions

Signaling through prion-like polymerization is conserved from fungi to mammals

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are grateful to Daniel Holmes and Sorna Kamara for technical assistance. We thank Hao Wu for FAS plasmid, Susan Lindquist for NM plasmid, and Susan Liebman for kar1 deficient yeast strain used for cytoduction. This work was supported by grants from the NIH (AI-093967 and GM-63692) and the Welch Foundation (I-1389) to Z.J.C, and the NIH Director's Early Independence Award (DP5-OD009152) to R.H. X.C was supported by an International Student Fellowship from Howard Hughes Medical Institute (HHMI). Z.J.C. is an HHMI investigator.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

SUPPLEMENTAL DATA

Supplemental Data include Experimental Procedures, 6 figures and 3 tables and can be found with this article online at http://www.cell.com.

REFERENCES

- Agostini L, Martinon F, Burns K, McDermott MF, Hawkins PN, Tschopp J. NALP3 forms an IL-1beta-processing inflammasome with increased activity in Muckle-Wells autoinflammatory disorder. Immunity. 2004;20:319–325. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(04)00046-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alberti S, Halfmann R, King O, Kapila A, Lindquist S. A systematic survey identifies prions and illuminates sequence features of prionogenic proteins. Cell. 2009;137:146–158. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.02.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broz P, Newton K, Lamkanfi M, Mariathasan S, Dixit VM, Monack DM. Redundant roles for inflammasome receptors NLRP3 and NLRC4 in host defense against Salmonella. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2010;207:1745–1755. doi: 10.1084/jem.20100257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daskalov A, Paoletti M, Ness F, Saupe SJ. Genomic clustering and homology between HET-S and the NWD2 STAND protein in various fungal genomes. PloS one. 2012;7:e34854. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0034854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrao R, Wu H. Helical assembly in the death domain (DD) superfamily. Current opinion in structural biology. 2012;22:241–247. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2012.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halfmann R, Lindquist S. Screening for amyloid aggregation by Semi-Denaturing Detergent-Agarose Gel Electrophoresis. Journal of visualized experiments : JoVE. 2008 doi: 10.3791/838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes DL, Lancaster AK, Lindquist S, Halfmann R. Heritable remodeling of yeast multicellularity by an environmentally responsive prion. Cell. 2013;153:153–165. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.02.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou F, Sun L, Zheng H, Skaug B, Jiang QX, Chen ZJ. MAVS forms functional prion-like aggregates to activate and propagate antiviral innate immune response. Cell. 2011;146:448–461. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.06.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang X, Kinch LN, Brautigam CA, Chen X, Du F, Grishin NV, Chen ZJ. Ubiquitin-induced oligomerization of the RNA sensors RIG-I and MDA5 activates antiviral innate immune response. Immunity. 2012;36:959–973. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.03.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kushnirov VV. Rapid and reliable protein extraction from yeast. Yeast. 2000;16:857–860. doi: 10.1002/1097-0061(20000630)16:9<857::AID-YEA561>3.0.CO;2-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, McQuade T, Siemer AB, Napetschnig J, Moriwaki K, Hsiao YS, Damko E, Moquin D, Walz T, McDermott A, et al. The RIP1/RIP3 necrosome forms a functional amyloid signaling complex required for programmed necrosis. Cell. 2012;150:339–350. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.06.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liebman SW, Chernoff YO. Prions in yeast. Genetics. 2012;191:1041–1072. doi: 10.1534/genetics.111.137760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liepinsh E, Barbals R, Dahl E, Sharipo A, Staub E, Otting G. The death-domain fold of the ASC PYRIN domain, presenting a basis for PYRIN/PYRIN recognition. Journal of molecular biology. 2003;332:1155–1163. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2003.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin SC, Lo YC, Wu H. Helical assembly in the MyD88-IRAK4-IRAK2 complex in TLR/IL-1R signalling. Nature. 2010;465:885–890. doi: 10.1038/nature09121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu S, Chen J, Cai X, Wu J, Chen X, Wu YT, Sun L, Chen ZJ. MAVS recruits multiple ubiquitin E3 ligases to activate antiviral signaling cascades. eLife. 2013;2:e00785. doi: 10.7554/eLife.00785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinon F, Burns K, Tschopp J. The inflammasome: a molecular platform triggering activation of inflammatory caspases and processing of proIL-beta. Molecular cell. 2002;10:417–426. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00599-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osherovich LZ, Cox BS, Tuite MF, Weissman JS. Dissection and design of yeast prions. PLoS biology. 2004;2:E86. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0020086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park HH, Lo YC, Lin SC, Wang L, Yang JK, Wu H. The death domain superfamily in intracellular signaling of apoptosis and inflammation. Annual review of immunology. 2007a;25:561–586. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.25.022106.141656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park HH, Logette E, Raunser S, Cuenin S, Walz T, Tschopp J, Wu H. Death domain assembly mechanism revealed by crystal structure of the oligomeric PIDDosome core complex. Cell. 2007b;128:533–546. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.01.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potter JA, Randall RE, Taylor GL. Crystal structure of human IPS-1/MAVS/VISA/Cardif caspase activation recruitment domain. BMC structural biology. 2008;8:11. doi: 10.1186/1472-6807-8-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prusiner SB. Novel proteinaceous infectious particles cause scrapie. Science. 1982;216:136–144. doi: 10.1126/science.6801762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prusiner SB. Prions. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1998;95:13363–13383. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.23.13363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiao Q, Yang C, Zheng C, Fontan L, David L, Yu X, Bracken C, Rosen M, Melnick A, Egelman EH, et al. Structural architecture of the CARMA1/Bcl10/MALT1 signalosome: nucleation-induced filamentous assembly. Mol Cell. 2013;51:766–779. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.08.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren PH, Lauckner JE, Kachirskaia I, Heuser JE, Melki R, Kopito RR. Cytoplasmic penetration and persistent infection of mammalian cells by polyglutamine aggregates. Nature cell biology. 2009;11:219–225. doi: 10.1038/ncb1830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saupe SJ. The [Het-s] prion of Podospora anserina and its role in heterokaryon incompatibility. Seminars in cell & developmental biology. 2011;22:460–468. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2011.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroder K, Tschopp J. The inflammasomes. Cell. 2010;140:821–832. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serio TR, Cashikar AG, Kowal AS, Sawicki GJ, Moslehi JJ, Serpell L, Arnsdorf MF, Lindquist SL. Nucleated conformational conversion and the replication of conformational information by a prion determinant. Science. 2000;289:1317–1321. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5483.1317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seth RB, Sun L, Ea CK, Chen ZJ. Identification and characterization of MAVS, a mitochondrial antiviral signaling protein that activates NF-kappaB and IRF 3. Cell. 2005;122:669–682. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seuring C, Greenwald J, Wasmer C, Wepf R, Saupe SJ, Meier BH, Riek R. The mechanism of toxicity in HET-S/HET-s prion incompatibility. PLoS biology. 2012;10:e1001451. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Si K, Choi YB, White-Grindley E, Majumdar A, Kandel ER. Aplysia CPEB can form prion-like multimers in sensory neurons that contribute to long-term facilitation. Cell. 2010;140:421–435. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun L, Deng L, Ea CK, Xia ZP, Chen ZJ. The TRAF6 ubiquitin ligase and TAK1 kinase mediate IKK activation by BCL10 and MALT1 in T lymphocytes. Mol Cell. 2004;14:289–301. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(04)00236-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun L, Wu J, Du F, Chen X, Chen ZJ. Cyclic GMP-AMP synthase is a cytosolic DNA sensor that activates the type I interferon pathway. Science. 2013;339:786–791. doi: 10.1126/science.1232458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeuchi O, Akira S. Pattern recognition receptors and inflammation. Cell. 2010;140:805–820. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toyama BH, Weissman JS. Amyloid structure: conformational diversity and consequences. Annual review of biochemistry. 2011;80:557–585. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-090908-120656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- True HL, Lindquist SL. A yeast prion provides a mechanism for genetic variation and phenotypic diversity. Nature. 2000;407:477–483. doi: 10.1038/35035005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vajjhala PR, Mirams RE, Hill JM. Multiple binding sites on the pyrin domain of ASC protein allow self-association and interaction with NLRP3 protein. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2012;287:41732–41743. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.381228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu J, Sun L, Chen X, Du F, Shi H, Chen C, Chen ZJ. Cyclic GMP-AMP is an endogenous second messenger in innate immune signaling by cytosolic DNA. Science. 2013;339:826–830. doi: 10.1126/science.1229963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoneyama M, Kikuchi M, Natsukawa T, Shinobu N, Imaizumi T, Miyagishi M, Taira K, Akira S, Fujita T. The RNA helicase RIG-I has an essential function in double-stranded RNA-induced innate antiviral responses. Nature immunology. 2004;5:730–737. doi: 10.1038/ni1087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng W, Sun L, Jiang X, Chen X, Hou F, Adhikari A, Xu M, Chen ZJ. Reconstitution of the RIG-I pathway reveals a signaling role of unanchored polyubiquitin chains in innate immunity. Cell. 2010;141:315–330. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.03.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.