Abstract

Background

In vitro data and early clinical results suggest that metformin has desirable antineoplastic effects and has a theoretical benefit on castration-resistant prostate cancer (CRPC).

Objective

To determine whether the use of metformin would be associated with improved clinical outcomes and a reduction in the development of CRPC.

Design, setting, and participants

Data from 2901 consecutive patients (157 metformin, 162 diabetic non-metformin, and 2582 nondiabetic) with localized prostate cancer treated with external-beam radiation therapy from 1992 to 2008 were collected from a single institution in the United States.

Intervention

Use of metformin in localized prostate cancer.

Outcome measurements and statistical analysis

Univariate and multivariate regression models utilizing k-sample, Fine and Gray, Cox regression, log-rank, and Kaplan-Meier methods to assess prostate-specific antigen-recurrence-free survival (PSA-RFS), distant metastases-free survival (DMFS), prostate cancer–specific mortality (PCSM), overall survival (OS), and development of CRPC.

Results and limitations

With a median follow-up of 8.7 yr, the 10-yr actuarial rates for metformin, diabetic non-metformin, and nondiabetic patients for PCSM were 2.7%, 21.9%, and 8.2% (log-rank p ≤ 0.001), respectively. Metformin use independently predicted (correcting for PSA, T stage, Gleason score, age, diabetic status, and androgen-deprivation therapy use) improvement in all outcomes compared with the diabetic non-metformin group; PSA-RFS (hazard ratio [HR]: 1.99 [1.24–3.18]; p = 0.004), DMFS (adjusted HR: 3.68 [1.78–7.62]; p < 0.001), and PCSM (HR: 5.15 [1.53–17.35]; p = 0.008). Metformin use was also independently associated with a decrease in the development of CRPC in patients experiencing biochemical failure compared with diabetic non-metformin patients (odds ratio: 14.81 [1.83–119.89]; p = 0.01). The retrospective study design was the primary limitation of the study.

Conclusions

To our knowledge, our results are the first clinical data to indicate that metformin use may improve PSA-RFS, DMFS, PCSM, OS, and reduce the development of CRPC in prostate cancer patients. Further validation of metformin's potential benefits is warranted.

Keywords: Diabetes, Metformin, Prostate cancer, Radiotherapy

1. Introduction

Prostate cancer is the most common noncutaneous malignancy and second leading cause of cancer death among men in the United States [1]. Although the etiology underlying the development of prostate cancer is complex, a recent consensus statement from the American Cancer Society and the American Diabetes Association emphasized a link between diabetes mellitus and prostate cancer [2]. It is known that cancer patients with diabetes, including those with prostate cancer, are at increased risk of long-term all-cause mortality compared with their nondiabetic counterparts [3], and diabetes has been associated with more aggressive disease among prostate cancer patients [4–6]. A postulated underlying mechanism is the elevated level of several anabolic growth factors including high serum insulin levels, androgens, and insulinlike growth factor (IGF)-1 [7–9].

Hyperinsulinemia has deleterious non–cancer-related morbidity but has also been shown to predict for increased prostate cancer mortality [8]. The state of hyperinsulinemia and insulin resistance leads to a decrease in sex hormone-binding globulins, causing an increase in available free unbound androgens that is important in hormone-responsive cancers such as breast and prostate cancer [10]. Complicating the treatment of prostate cancer, treatment with androgen-deprivation therapy (ADT) leads to insulin resistance, which may be involved in the development of castrate-resistant prostate cancer (CRPC) [9].

These findings have led to increasing interest in pharmacologically targeting pathways of metabolism, especially those involved in the development of insulin resistance. Metformin, a biguanide oral antihyperglycemic agent, abrogates hyperinsulinemia in individuals with and without diabetes [11,12], and it may be a promising agent for therapeutic gain in prostate cancer [13]. Supporting this, metformin has been shown to inhibit the proliferation of prostate cancer cell lines in vitro [14,15]. Molecular mechanisms postulated to underlie the antineoplastic effects of metformin include activation of the adenosine monophosphate–activated protein kinase (AMPK) pathway, thereby inhibiting the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) signaling cascade downstream [14–18]. Insufficient AMPK activity permits cell growth, making it an attractive target for anticancer therapy.

A few selected reports have shown that metformin has an impact on overall survival among men with prostate cancer; however, none have included prostate cancer–specific outcomes to demonstrate an oncologic benefit of metformin [19,20]. We hypothesized that the use of metformin in patients with prostate cancer would be associated with improved clinical outcomes. A large cohort of 2901 consecutive men undergoing external-beam radiation therapy (EBRT) for localized prostate cancer was identified, and outcomes of tumor control were compared between patients receiving and not receiving metformin, as well as stratifying by diabetic status in the non-metformin group. Additionally, based on the knowledge that hyperinsulinemia may contribute to the development of CRPC, we investigated the effects of metformin on the development of castration-resistant disease.

2. Methods

2.1. Study design

Institutional review board approval was obtained to conduct this study. We retrospectively identified 3045 consecutive patients with localized prostate cancer treated with definitive EBRT from January 1992 to December 2008 at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center. All patients had biopsy-proven adenocarcinoma with pathology reviewed by a urologic pathologist at our institution. Patients with evidence of lymph node metastasis or distant metastasis by pretreatment computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, and/or bone scan, or prior treatment with pelvic radiation or radical prostatectomy were excluded [21]. The remaining 2901 patients formed the study cohort for analysis. ADT was prescribed at the discretion of the treating physician. Patient data were censored for analysis on January 1, 2012. Salvage therapy after biochemical failure generally consisted of combination ADT and rarely salvage radical prostatectomy.

2.2. Study outcomes

In general, patients were followed every 3 mo from the time of completion of treatment for the first year, followed by every 6 mo for the next 5 yr, and yearly thereafter. Outcomes were calculated from the end of radiation therapy. The outcomes measured included prostate-specific antigen recurrence-free survival (PSA-RFS), distant metastasis-free survival (DMFS), prostate cancer–specific mortality (PCSM), and overall survival (OS). PSA recurrence was determined by the Phoenix definition: post-treatment PSA nadir plus 2 ng/ml. PCSM was defined by death clearly associated with prostate cancer.

Three groups were used for analyses: patients using metformin, diabetic patients who were treated with diabetic medications other than metformin, and nondiabetic patients none of whom were taking metformin. Metformin users were patients who were on metformin at the time of their diagnosis of prostate cancer or at any time postradiotherapy. Twenty-nine patients (18%) initiated metformin therapy after radiation therapy had completed. The time range of metformin use was calculated from the time of initial visit to the time of the last record of metformin use. All patients had full information on the duration of metformin use. Diabetic patients were patients who carried the diagnosis at the time of treatment of prostate cancer or developed diabetes at some point after therapy. Forty-four patients (14%) were diagnosed with diabetes after their treatment for prostate cancer. Patients without diabetes were never diagnosed with the disease and had no record of using metformin. Two physicians independently reviewed all cases for accuracy of the diagnosis of diabetes and categorized the type of diabetic medication into the appropriate class (metformin, sulfonureas, thiazolidinediones, dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors, meglitinides, α-glucosidase inhibitors, glucagon-like peptide agonists, and insulin). Body mass index (BMI) was available for 416 men. Pretreatment cardiac status was assessed for all patients based on a history of unstable angina, myocardial infarction, or cardiac intervention including percutaneous cardiac intervention (ie, stent) or coronary artery bypass surgery. Patients were stratified into low-, intermediate-, and high-risk groups based on the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) risk classification v.3.2012. CRPC was defined among patients who had experienced a biochemical failure by the Phoenix definition in the setting of castrate levels of testosterone (≤50 ng/dl) [22].

2.3. Statistical analysis

Categorical variables are listed as frequencies and percentages, and continuous variables are listed as medians with interquartile ranges. To compare baseline characteristics between patients taking metformin, diabetic non-metformin patients, and nondiabetic patients, the chi-square test was used for categorical variables and the Wilcoxon rank-sum test for continuous variables. All statistical tests were two tailed, and p values <0.05 were considered statistically significant. Actuarial survival-time curves for PSA-RFS, DMFS, and OS were calculated using the Kaplan-Meier method, and comparisons were performed using a log-rank test. Univariate hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for these variables were performed using a Cox proportional hazards model, and multivariate analyses to adjust for covariates were performed using a standard Cox regression. Clinically relevant covariates included in the models were age, total Gleason score, T stage, pretreatment PSA, and use of neoadjuvant ADT.

For PCSM, a competing risk analysis was performed. Univariate variables were compared using a k-sample test, and multivariate analysis was performed using a Fine and Gray multivariate analysis. To compare the effect of metformin on CRPC, a simple Fisher exact test was performed solely among patients who experienced biochemical failure. To correct for imbalances between groups, logistical regression modeling was performed. Because all metformin patients were diabetic, and no nondiabetic patients used metformin, tests of interaction were not able to be performed.

3. Results

3.1. Study population

Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics of the study cohort. The median follow-up for the entire cohort was 8.7 yr. The median age of patients was 69 yr (interquartile range [IQR]: 64–73 yr). Of the 2901 eligible patients for analysis, 319 had diabetes, of whom 157 were taking metformin and 162 were not taking metformin. The median duration of metformin use was 58.2 mo (IQR: 38–88 mo), the mean was 63.4 mo, and the median dose of metformin was 500 mg twice daily. Supplementary Table 1 summarizes the salvage therapy used upon development of CRPC including chemotherapy and newer antiandrogen therapy.

Table 1. Patient clinical characteristics.

| All patients | Diabetic | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||||

| Yes | No | ||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| Metformin* | Non-metformin | p value | p value | ||||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | ||||

| Total n | 2901 | 100 | 157 | 5.4 | 162 | 5.6 | 2582 | 89.0 | |||

|

| |||||||||||

| Age, yr | 0.64 | 0.13 | |||||||||

| Median ± IQR | 69 | 64–73 | 68 | 64–70 | 69 | 65-70 | 69 | 64–70 | |||

| >65 | 2022 | 69.7 | 101 | 64.3 | 109 | 67.3 | 1812 | 70.2 | |||

| ≤65 | 879 | 30.3 | 56 | 35.7 | 53 | 32.7 | 770 | 29.8 | |||

|

| |||||||||||

| NCCN risk group | 0.30 | 0.27 | |||||||||

| Low Intermediat | 645 | 22.2 | 28 | 17.8 | 25 | 15.4 | 592 | 22.9 | |||

| e | 1232 | 42.5 | 68 | 43.3 | 60 | 37.0 | 1104 | 42.8 | |||

| High | 1024 | 35.3 | 61 | 38.9 | 77 | 47.5 | 886 | 34.3 | |||

|

| |||||||||||

| T stage† | <0.05 | <0.05 | |||||||||

| T1c–2a | 1836 | 63.3 | 123 | 78.3 | 92 | 56.8 | 1621 | 62.8 | |||

| T2b–c | 637 | 22.0 | 21 | 13.4 | 39 | 24.1 | 577 | 22.3 | |||

| ≥T3a | 428 | 14.8 | 13 | 8.3 | 31 | 19.1 | 384 | 14.9 | |||

|

| |||||||||||

| Gleason score | 0.98 | <0.05 | |||||||||

| ≤6 | 1273 | 43.9 | 49 | 31.2 | 49 | 30.2 | 1175 | 45.5 | |||

| 7 | 1126 | 38.8 | 67 | 42.7 | 71 | 43.8 | 988 | 38.3 | |||

| ≥8 | 502 | 17.3 | 41 | 26.1 | 42 | 25.9 | 419 | 16.2 | |||

|

| |||||||||||

| Pretreatment PSA | 0.57‡ | 0.64‡ | |||||||||

| Median (± IQR) | 8.1 | 5.5–14 | 7.6 | 5.2–13.7 | 8.1 | 5.5–18.0 | 8.1 | 5.5–13.9 | |||

| ≤10 ng/ml | 1739 | 59.9 | 97 | 61.8 | 95 | 58.6 | 1547 | 59.9 | |||

| >10 ng/ml | 1162 | 40.1 | 60 | 38.2 | 67 | 41.4 | 1035 | 40.1 | |||

|

| |||||||||||

| Neoadjuvant ADT | 0.75 | 0.06 | |||||||||

| Yes | 1440 | 49.6 | 89 | 56.7 | 89 | 54.9 | 1262 | 48.9 | |||

| No | 1461 | 50.4 | 68 | 43.3 | 73 | 45.1 | 1320 | 51.1 | |||

|

| |||||||||||

| Pre-RT cardiac disease | 0.09 | 0.91 | |||||||||

| Yes | 468 | 16.1 | 25 | 15.9 | 15 | 9.3 | 428 | 16.6 | |||

| No | 2433 | 83.9 | 132 | 84.1 | 147 | 90.7 | 2154 | 83.4 | |||

|

| |||||||||||

| BMI | 0.38 | <0.05 | |||||||||

| Median (± IQR) | 27.1 | 24.5–30.2 | 30. 4 | 26.3–34.1 | 29. 4 | 27.0–33.3 | 26.8 | 24.4–29.9 | |||

|

| |||||||||||

| Metformin duration, mo | |||||||||||

| Median (± IQR) | 58 | 38–88 | |||||||||

| Mean | 63 | ||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| PSA-RFS | 10-yr actuarial (%) | 65.3 | 67. 3 | 55. 7 | 65.5 | ||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| DMFS | 10-yr actuarial (%) | 85.3 | 89. 7 | 66. 1 | 86.1 | ||||||

| PCSM | 10-yr actuarial (%) | 16.9 | 2.7 | 21. 9 | 8.2 | ||||||

ADT = androgen-deprivation therapy; BMI = body mass index; DMFS = distant metastasis-free survival; IQR = interquartile range; NCCN = National Comprehensive Cancer Network v.3.2012; PCSM = prostate cancer-specific mortality; PSA = prostate-specific antigen; PSA-RFS = prostate-specific antigen-relapse-free survival; RT = radiotherapy.

Note: Percentages may not sum to 100% due to rounding.

Reference group for comparison.

Based on American Joint Committee on Cancer, 7th ed.

Calculated from chi-square of PSA ≤10 ng/ml or >10 ng/ml.

3.2. Metformin and prostate-specific antigen recurrence

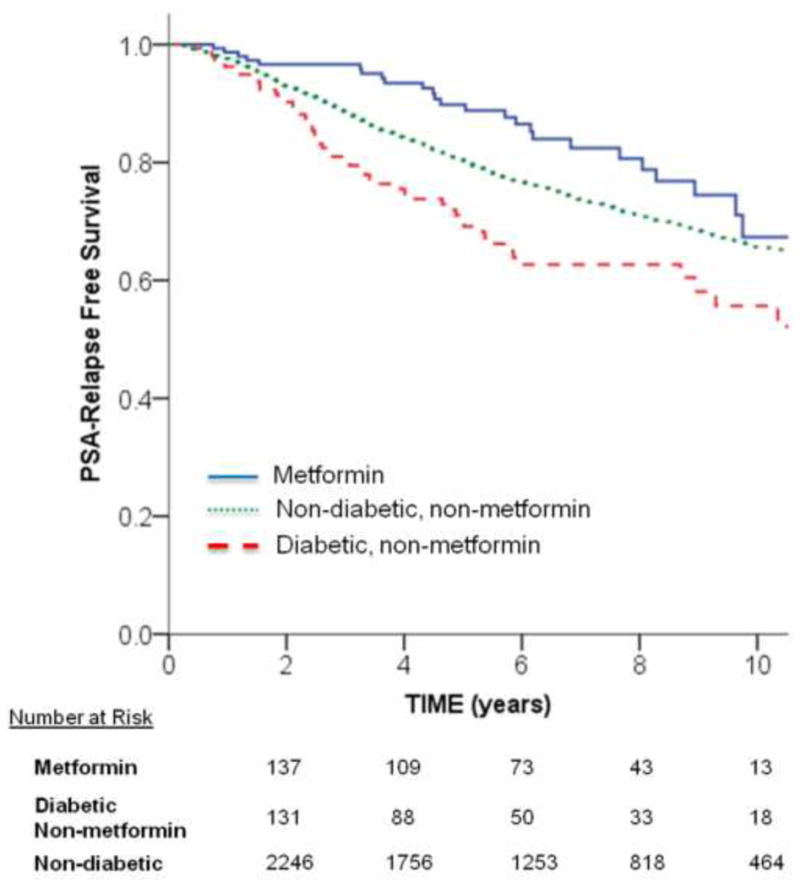

A total of 16.5% (n = 26) of metformin, 32.7% (n = 53) of diabetic non-metformin, and 25.8% (n = 666) of nondiabetic patients developed a PSA recurrence. The 10-yr actuarial PSA-RFS were 67.3%, 55.7%, and 65.5%, respectively (log-rank p < 0.001; Fig. 1). Cox regression analysis with the metformin group as the reference group demonstrated that PSA-RFS was worse in the nondiabetic group (adjusted HR: 1.44; 95% CI, 0.96–2.13; p = 0.07) as well as significantly worsened in the diabetic non-metformin group (adjusted HR: 1.99 [1.24–3.18]; p = 0.004).

Fig. 1.

Unadjusted Kaplan-Meier curves for prostate-specific antigen (PSA) relapse-free survival among metformin, diabetic non-metformin, and nondiabetic groups. The univariate unadjusted p value for comparing groups was statistically significant: metformin versus diabetic non-metformin, p < 0.001; metformin versus nondiabetic, p = 0.04; and diabetic non-metformin versus nondiabetic, p = 0.002.

3.3. Metformin and distant metastases

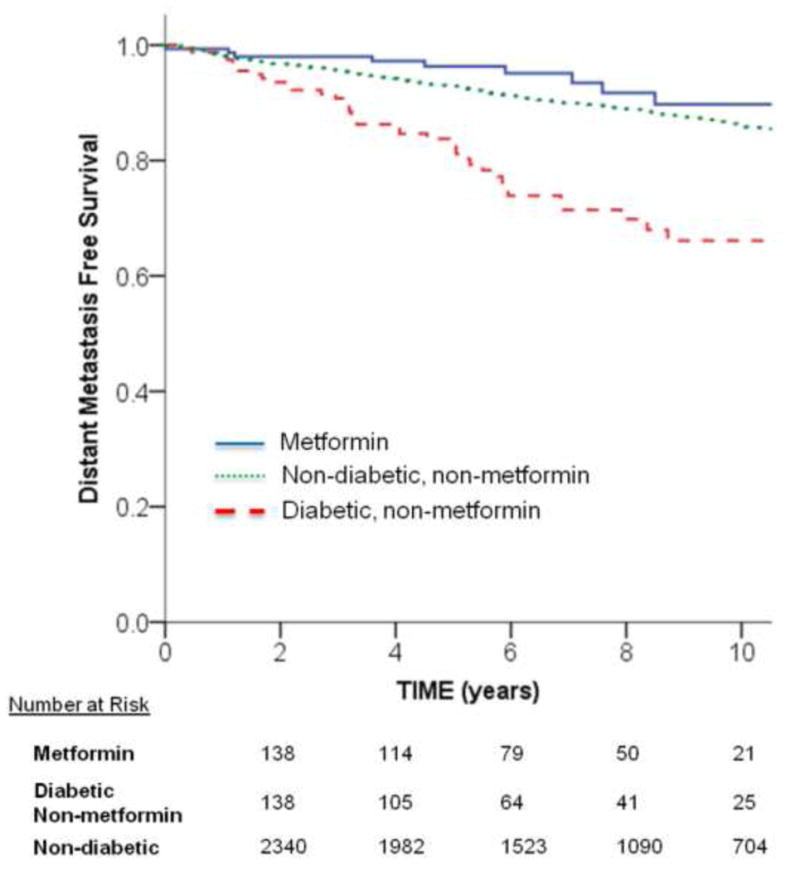

A total of 5.7% (n = 9) of metformin, 24.1% (n = 39) diabetic non-metformin, and 11.5% (n = 298) of nondiabetic patients developed a distant metastasis. The 10-yr actuarial DMFS was 89.7%, 66.1%, and 86.1%, respectively (log-rank p < 0.001; Fig. 2). Cox regression analysis with the metformin group as the reference group demonstrated that DMFS was nonsignificantly worsened in the nondiabetic group (adjusted HR: 1.75 [0.90–3.41]; p = 0.10) and significantly worsened in the diabetic non-metformin group (adjusted HR: 3.68 [1.78–7.62]; p < 0.001) (Supplementary Table 2).

Fig. 2.

Unadjusted Kaplan-Meier curves for distant metastasis-free survival among metformin, diabetic non-metformin, and nondiabetic groups. The univariate unadjusted p value for comparing groups was statistically significant: metformin versus diabetic non-metformin, p < 0.001; metformin versus nondiabetic, p = 0.11; and diabetic non-metformin versus nondiabetic, p < 0.001.

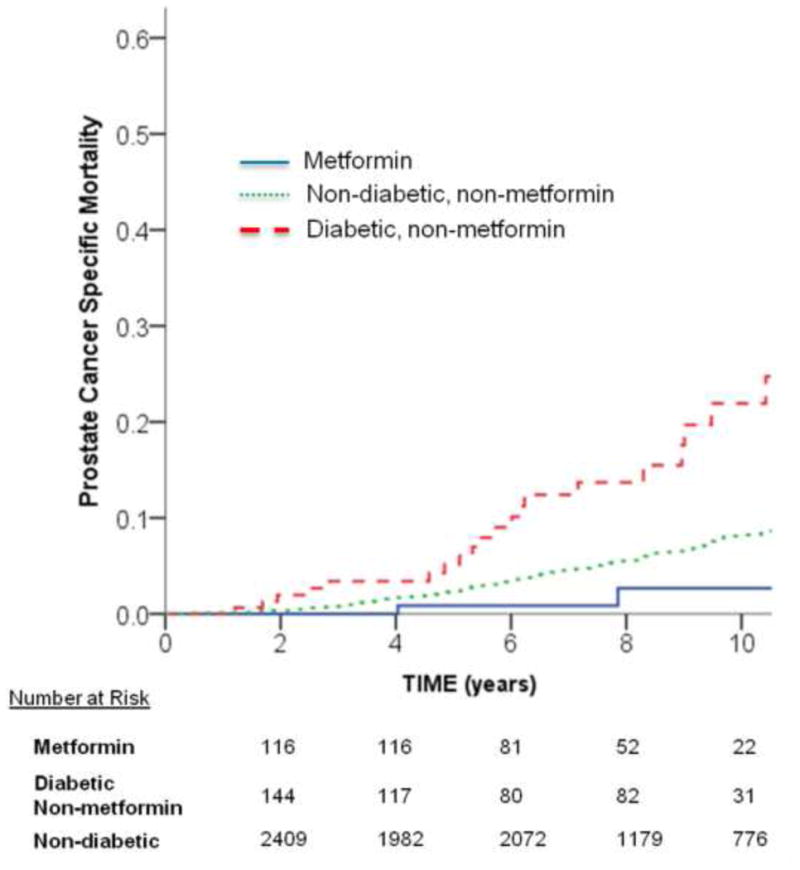

3.4. Metformin and prostate cancer–specific mortality and overall survival

A total of 1.9% (n = 3) of metformin, 13.0% (n = 21) diabetic non-metformin, and 6.8% (n = 175) of nondiabetic patients died from prostate cancer. The 10-yr PCSM using competing risk analysis was 2.7%, 21.9%, and 8.2%, respectively (log-rank p < 0.001; Fig. 3). Using Fine and Gray regression with the metformin group as the reference group demonstrated that PCSM trended for significant detriment in the nondiabetic group (adjusted HR: 2.68 [0.85–8.44]; p = 0.09) and was associated with a significant detriment compared with the diabetic non-metformin group (adjusted HR: 5.15 [1.53–17.35]; p = 0.008) (Table 2).

Fig. 3.

Unadjusted cumulative incidence function curves for prostate cancer–specific mortality among metformin, diabetic non-metformin, and nondiabetic groups. The univariate unadjusted p value for comparing groups was statistically significant: metformin versus diabetic non-metformin, p = 0.001; metformin versus nondiabetic, p = 0.09; and diabetic non-metformin versus nondiabetic, p < 0.001.

Table 2. Univariate and multivariate competing risk analysis for prostate cancer–specific mortality*.

| UVA | MVA | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | p value | AHR | 95% CI | p value | |

| Metformin use | ||||||

| Metformin | 1.00 | Referent | – | 1.00 | Referent | - |

| Non-metformin diabetic | 6.21 | 1.85–20.8 | 0.003 | 5.15 | 1.53-17.35 | 0.008 |

| Nondiabetic | 2.58 | 0.82–8.09 | 0.1 | 2.68 | 0.85–8.44 | 0.091 |

| Age | 0.99 | 0.74–1.34 | 0.96 | 0.93 | 0.69–1.25 | 0.63 |

| Total Gleason score | ||||||

| ≤6 | 1.00 | Referent | – | 1.00 | – | |

| 7 | 2.46 | 1.71–3.56 | <0.001 | 2.03 | 1.40–2.95 | <0.001 |

| ≥8 | 5.21 | 3.60–7.54 | <0.001 | 3.55 | 2.39–5.27 | <0.001 |

| T stage | ||||||

| T1c-2a | 1.00 | Referent | – | 1.00 | – | |

| Tb-c | 1.89 | 1.30–2.74 | 0.001 | 1.54 | 1.06–2.25 | 0.03 |

| ≥T3a | 5.27 | 3.77–7.36 | <0.001 | 3.46 | 2.42–4.95 | <0.001 |

| PSA | 1.74 | 1.31–2.32 | <0.001 | 1.22 | 0.91–1.64 | 0.18 |

| Neoadjuvant ADT use | 1.62 | 1.22–2.15 | 0.001 | 1.00 | 0.74–1.36 | 0.98 |

| BMI† | 1.01 | 0.99–1.02 | 0.54 | |||

| Pre-tx cardiac disease | 0.67 | 0.42–1.08 | 0.11 | |||

ADT = androgen-deprivation therapy; AHR = adjusted hazard ratio; BMI = body mass index; CI = confidence interval; HR = hazard ratio; MVA = multivariate; NCCN = National Comprehensive Cancer Network; PSA = prostate-specific antigen; tx = therapy; UVA = univariate.

NCCN risk group was included on the univariate model but not the multivariate model due to the components that make the risk group individually significant (PSA, T stage, Gleason score) and were each included in the multivariate model.

Base of 453 patients.

A subgroup analysis was performed by the NCCN risk group. The 10-yr actuarial cumulative incidence rates of PCSM for low-, intermediate-, and high-risk groups for metformin/diabetic non-metformin/nondiabetic patients were 0.0%, 0.0%, and 1.0% (log-rank p = 0.77), 7.4%, 9.4%, and 4.9% (p = 0.62), and 10.0%, 32.6%, and 17.1% (p = 0.001), respectively. OS was analyzed to ensure metformin was not leading to an unexpected increase in non–cancer-related deaths. The 10-yr actuarial OS rates were 81.6%, 55.4%, and 71.8% for the metformin, diabetic non-metformin, and nondiabetic groups, respectively (log-rank p < 0.001). Cox regression analysis with the metformin group as the reference group demonstrated that OS was nonsignificantly worsened in the nondiabetic group (adjusted HR: 1.38 [0.9–2.11]; p = 0.14) and significantly worsened in the diabetic non-metformin group (adjusted HR: 2.25 [1.38–3.661]; p = 0.001).

3.5. Metformin and castration resistance

Of the 26 metformin, 53 diabetic non-metformin, and 666 nondiabetic patients who developed a biochemical failure, 25, 53, and 559 were evaluable for the development of CRPC. A total of 1 (4%), 23 (43%), and 148 (26%) patients went on to develop CRPC (comparisons between all groups p < 0.001) (Supplementary Fig. 1). Using logistical regression to determine associations with CRPC and correct for imbalances (Table 3) with metformin as the reference group, the diabetic non-metformin patients had significantly greater rates of development of CRPC (adjusted odds ratio [OR]: 14.81 [1.83–119.89]; p = 0.01), and nondiabetic patients also had significantly higher rates of development of CRPC (adjusted OR: 8.88 [1.17–67.38]; p = 0.04).

Table 3. Cox-regression multivariate analysis for the development of castrate-resistant prostate cancer.

| MVA | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | p value | |

| Metformin use | |||

| Metformin | 1.00 | Referent | – |

| Non-metformin diabetic | 14.81 | 1.83–119.89 | 0.01 |

| Nondiabetic | 8.88 | 1.17–67.38 | 0.04 |

| Age | 0.68 | 0.45–1.04 | 0.08 |

| Total Gleason score | |||

| ≤6 | 1.00 | Referent | 0.005 |

| 7 | 1.60 | 0.92–2.77 | 0.10 |

| ≥8 | 2.71 | 1.48–4.95 | 0.001 |

| T stage | |||

| T1c-2a | 1.00 | Referent | 0.07 |

| Tb-c | 1.50 | 0.91–2.47 | 0.11 |

| ≥T3a | 1.75 | 1.06–2.90 | 0.03 |

| PSA | 1.42 | 0.92–2.29 | 0.11 |

| Neoadjuvant ADT use | 1.24 | 0.79–1.96 | 0.35 |

ADT = androgen-deprivation therapy; CI = confidence interval; MVA = multivariate analysis; OR = odds ratio; PSA = prostate-specific antigen.

3.6. Duration of metformin and outcomes

An exploratory analysis was performed to determine the effect of metformin duration on outcomes. Based on a Cox proportional hazard univariate analysis using metformin use as a continuous variable, duration of metformin use was not associated with PSA-RFS (p = 0.30), DMFS (p = 0.86), and PCSM (p = 0.31).

3.7. Other diabetic medications and prostate cancer–specific mortality

Among diabetic patients, patients who used metformin had a greater use of thiazolidinediones (29% vs 11%; p < 0.001) and a trend for greater use of sulfonureas (59% vs 47%; p = 0.06) and dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors (57% vs 19%; p = 0.08) (Supplementary Table 3). To ensure these medications did not confound metformin's impact, a Cox regression analysis was performed. None of the other diabetic medications (sulfonureas, thiazolidinediones, dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors, meglitinides, α-glucosidase inhibitors, glucagon-like peptide agonists, and insulin) showed a significant impact on PSA-RFS, DMFS, PCSM, or OS.

4. Discussion

Our results indicate that metformin use is associated with a significant clinical benefit in patients with prostate cancer undergoing definitive radiotherapy. In multivariate models correcting for imbalances in clinical variables, metformin decreased the risk of PSA recurrence, distant metastasis, and PCSM compared with diabetic non-metformin patients. To our knowledge, this is the first clinical evidence that metformin may improve cancer-specific survival outcomes in prostate cancer. Furthermore, metformin strongly decreased the clinically defined transformation from androgen-sensitive prostate cancer to CRPC.

There has been increasing clinical evidence that metformin may be beneficial in the treatment of cancer patients. Population-based studies suggest a decreased incidence of cancer in diabetic patients taking metformin [11,23] as well as improved survival with metformin use [12,20,24,25]. One retrospective report from the MD Anderson Cancer Center demonstrated an overall survival benefit for prostate cancer patients treated with metformin compared with diabetic controls [20]. However, the survival benefit may have been due to improvements in non-cancer-related mortality because prostate cancer-specific outcomes were not reported. In our analysis, patients treated with radiation therapy with metformin had lower rates of distant metastasis, PCSM, in addition to overall mortality, providing insight into the oncologic benefits of metformin use.

The mechanism of action whereby metformin may target cancer cells continues to be elucidated. Preclinical investigations demonstrate that metformin is capable of inhibiting the growth of numerous cancer cell lines including prostate cancer [7–9,26,27]. This inhibitory effect may be mediated via metformin's modulation of several oncogenic signaling pathways [10,28,29]. For example, metformin activates AMPK, resulting in a rapid reduction in protein synthesis and cell growth. Additionally, AMPK is an important inhibitor of the mTOR signaling cascade, which regulates cell growth, cell cycle progression, and angiogenesis [16]. Of note, metformin appears to induce mTOR inhibition through AMPK-independent mechanisms as well [15,30]. The activation of AMPK causes a reduction in insulin, IGF-1, and androgens, all potent mediators of tumorigenesis and cell growth. Intriguingly, there are data to suggest metformin may specifically target cancer stem cells, which are hypothesized to be resistant to conventional therapies and be a major reason for recurrence following radiation or chemotherapy [31].

Major benefits of metformin include that it is inexpensive, administered orally, and has an extremely favorable toxicity profile. Mild gastrointestinal upset is the most common side effect, and serious toxicity, such as lactic acidosis, is exceptionally rare [32]. Metformin is also safe in nondiabetic patients and approved for conditions other than diabetes including polycystic ovary syndrome [33]. Targeting metabolic pathways in prostate cancer with metformin is particularly appealing given that one of the mainstays of therapy, ADT, is associated with an increased risk of diabetes, insulin resistance, and the metabolic syndrome [34]. Furthermore, in vitro data have shown that metformin in combination with ADT is more effective in inhibiting prostate cancer colony formation rates than either therapy alone [35]. Thus metformin may increase cancer cytotoxicity while simultaneously mitigating toxicity from other therapies. We did perform a subgroup analysis based on an NCCN risk group and found the greatest benefit to be in the high-risk group. Because high-risk patients are most likely to be on ADT and most likely to develop CRPC, the reduction in the development of castrate-resistant disease with metformin may partially explain why the high-risk group experienced the greatest benefit in PCSM. Multiple prospective trials investigating the efficacy of metformin in cancer are underway, with at least 40 such studies currently registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov. It will take years for these trials not only to accrue, but mature to report on long-term survival outcomes, hence the importance of our findings. For now, we hope the results from retrospective series including metformin's beneficial impact on pathologic complete response rate in breast cancer, associated improved survival in pancreatic cancer, and the results presented here will help guide both preclinical and future clinical trials.

Several limitations of this study need to be noted. Most significantly, given its retrospective nature and the fact that metformin was not a randomized variable, bias from unmeasured confounding variables is possible. Comorbidities including BMI and the severity and duration of diabetes were difficult to assess accurately and are not reported. BMI data were only available for 453 patients and therefore not included in the analyses. However, it has been shown that obesity is independently associated with prostate cancer–specific outcomes. Insulin levels were not measured to provide mechanistic insights into our hypothesis. Due to the limited number of metformin patients and events that occurred, the methodology of our analyses did not incorporate exposure or time-dependent use of metformin or diabetes. Despite these weaknesses, this is the first study to our knowledge to report significant improvement in prostate cancer–specific outcomes with the use of metformin.

5. Conclusions

In our retrospective study, diabetic patients with prostate cancer who use metformin have an improvement in cancer-specific outcomes. Metformin users trended for a small but significant improvement compared with nondiabetic patients in these outcomes, which raises the question of what effect metformin may have on nondiabetic patients, especially in the setting of ADT. It appears that part of the clinical effect of the improvement in PCSM is related to the reduction in the development of CRPC. These results add to a growing body of literature suggesting the antineoplastic activity of metformin and may have a future role in the treatment of prostate cancer. These results need to be validated in a prospective manner.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Fig. 1 – Comparison of the development of castrate-resistant prostate cancer among patients who experience a prostate-specific antigen failure among the metformin, diabetic non-metformin, and nondiabetic groups. A simple Fischer exact test was performed showing p < 0.001 between all groups.

Take-home message.

Among 2901 localized prostate cancer patients, metformin reduces the development of castrate-resistant disease compared with diabetic non-metformin users and nondiabetic controls. Metformin appears to reduce the development of biochemical failure, distant metastasis, prostate cancer-specific mortality, and death.

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support and role of the sponsor: None.

Acknowledgment statement: The authors acknowledge Eve Ferman for her help in editing the paper.

Footnotes

This study in part was accepted for an oral presentation at the annual American Society for Radiation Oncology (ASTRO) conference in Boston, Massachusetts, on October 28, 2012.

Author contributions: Michael J. Zelefsky had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Study concept and design: Spratt, C. Zhang, Zelefsky.

Acquisition of data: Spratt, Zumsteg, Pei, C. Zhang.

Analysis and interpretation of data: Spratt, Zumsteg, Pei, Z. Zhang, Zelefsky.

Drafting of the manuscript: Spratt, Zumsteg, Pei, Z. Zhang, Zelefsky.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Spratt, Zumsteg, Pei, Z. Zhang, Zelefsky.

Statistical analysis: Spratt, Zumsteg, Pei, Z. Zhang.

Obtaining funding: None.

Administrative, technical, or material support: Zelefsky.

Supervision: Zelefsky.

Other (specify): None.

Financial disclosures: Michael J. Zelefsky certifies that all conflicts of interest, including specific financial interests and relationships and affiliations relevant to the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript (eg, employment/ affiliation, grants or funding, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, royalties, or patents filed, received, or pending), are the following: None.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Center MM, Jemal A, Lortet-Tieulent J, et al. International variation in prostate cancer incidence and mortality rates. Eur Urol. 2012;61:1079–92. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2012.02.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Giovannucci E, Harlan DM, Archer MC, et al. Diabetes and cancer: a consensus report. Diabetes Care. 2010;33:1674–85. doi: 10.2337/dc10-0666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barone BB, Yeh HC, Snyder CF, et al. Long-term all-cause mortality in cancer patients with preexisting diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2008;300:2754–64. doi: 10.1001/jama.2008.824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mitin T, Chen MH, Zhang Y, et al. Diabetes mellitus, race and the odds of high grade prostate cancer in men treated with radiation therapy. J Urol. 2011;186:2233–7. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2011.07.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kang J, Chen MH, Zhang Y, et al. Type of diabetes mellitus and the odds of Gleason score 8 to 10 prostate cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2012;82:e463–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2011.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abdollah F, Briganti A, Suardi N, et al. Does diabetes mellitus increase the risk of high-grade prostate cancer in patients undergoing radical prostatectomy? Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2011;14:74–8. doi: 10.1038/pcan.2010.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Waters KM, Henderson BE, Stram DO, Wan P, Kolonel LN, Haiman CA. Association of diabetes with prostate cancer risk in the multiethnic cohort. Am J Epidemiol. 2009;169:937–45. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwp003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ma J, Li H, Giovannucci E, et al. Prediagnostic body-mass index, plasma C-peptide concentration, and prostate cancer-specific mortality in men with prostate cancer: a long-term survival analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2008;9:1039–47. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70235-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aggarwal RR, Ryan CJ, Chan JM. Insulin-like growth factor pathway: a link between androgen deprivation therapy (ADT), insulin resistance, and disease progression in patients with prostate cancer? Urol Oncol. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2011.05.001. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jalving M, Gietema JA, Lefrandt JD, et al. Metformin: taking away the candy for cancer? Eur J Cancer. 2010;46:2369–80. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2010.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Murtola TJ, Tammela TL, Lahtela J, Auvinen A. Antidiabetic medication and prostate cancer risk: a population-based case-control study. Am J Epidemiol. 2008;168:925–31. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwn190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sadeghi N, Abbruzzese JL, Yeung SC, Hassan M, Li D. Metformin use is associated with better survival of diabetic patients with pancreatic cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18:2905–12. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-2994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Clements A, Gao B, Yeap SH, Wong MK, Ali SS, Gurney H. Metformin in prostate cancer: two for the price of one. Ann Oncol. 2011;22:2556–60. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdr037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ben Sahra I, Laurent K, Loubat A, et al. The antidiabetic drug metformin exerts an antitumoral effect in vitro and in vivo through a decrease of cyclin D1 level. Oncogene. 2008;27:3576–86. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1211024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ben Sahra I, Laurent K, Giuliano S, et al. Targeting cancer cell metabolism: the combination of metformin and 2-deoxyglucose induces p53-dependent apoptosis in prostate cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2010;70:2465–75. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-2782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zakikhani M, Dowling R, Fantus IG, Sonenberg N, Pollak M. Metformin is an AMP kinase-dependent growth inhibitor for breast cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2006;66:10269–73. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rozengurt E, Sinnett-Smith J, Kisfalvi K. Crosstalk between insulin/insulin-like growth factor-1 receptors and G protein-coupled receptor signaling systems: a novel target for the antidiabetic drug metformin in pancreatic cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:2505–11. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-2229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kato K, Gong J, Iwama H, et al. The antidiabetic drug metformin inhibits gastric cancer cell proliferation in vitro and in vivo. Mol Cancer Ther. 2012;11:549–60. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-11-0594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Currie CJ, Poole CD, Jenkins-Jones S, Gale EA, Johnson JA, Morgan CL. Mortality after incident cancer in people with and without type 2 diabetes: impact of metformin on survival. Diabetes Care. 2012;35:299–304. doi: 10.2337/dc11-1313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.He XX, Tu SM, Lee MH, Yeung SC. Thiazolidinediones and metformin associated with improved survival of diabetic prostate cancer patients. Ann Oncol. 2011;22:2640–5. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdr020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Spratt DE, Pei X, Yamada J, Kollmeier MA, Cox B, Zelefsky MJ. Long-term survival and toxicity in patients treated with high-dose intensity modulated radiation therapy for localized prostate cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2012.05.023. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bubley GJ, Carducci M, Dahut W, et al. Eligibility and response guidelines for phase II clinical trials in androgen-independent prostate cancer: recommendations from the Prostate-Specific Antigen Working Group. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:3461–7. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.11.3461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wright JL, Stanford JL. Metformin use and prostate cancer in Caucasian men: results from a population-based case-control study. Cancer Causes Control. 2009;20:1617–22. doi: 10.1007/s10552-009-9407-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Garrett CR, Hassabo HM, Bhadkamkar NA, et al. Survival advantage observed with the use of metformin in patients with type II diabetes and colorectal cancer. Br J Cancer. 2012;106:1374–8. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2012.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.He X, Esteva FJ, Ensor J, Hortobagyi GN, Lee MH, Yeung SC. Metformin and thiazolidinediones are associated with improved breast cancer-specific survival of diabetic women with HER2+ breast cancer. Ann Oncol. 2012;23:1771–80. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdr534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.D'Amico AV, Braccioforte MH, Moran BJ, Chen MH. Causes of death in men with prevalent diabetes and newly diagnosed high- versus favorable-risk prostate cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2010;77:1329–37. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2009.06.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Abdollah F, Briganti A, Suardi N, et al. Does diabetes mellitus increase the risk of high-grade prostate cancer in patients undergoing radical prostatectomy? Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2011;14:74–8. doi: 10.1038/pcan.2010.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shaw RJ, Lamia KA, Vasquez D, et al. The kinase LKB1 mediates glucose homeostasis in liver and therapeutic effects of metformin. Science. 2005;310:1642–6. doi: 10.1126/science.1120781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Inoki K, Zhu T, Guan KL. TSC2 mediates cellular energy response to control cell growth and survival. Cell. 2003;115:577–90. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00929-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kalender A, Selvaraj A, Kim SY, et al. Metformin, independent of AMPK, inhibits mTORC1 in a rag GTPase-dependent manner. Cell Metab. 2010;11:390–401. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2010.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hirsch HA, Iliopoulos D, Tsichlis PN, Struhl K. Metformin selectively targets cancer stem cells, and acts together with chemotherapy to block tumor growth and prolong remission. Cancer Res. 2009;69:7507–11. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-2994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bailey CJ, Turner RC. Metformin. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:574–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199602293340906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nestler JE. Metformin for the treatment of the polycystic ovary syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:47–54. doi: 10.1056/NEJMct0707092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Keating NL, O'Malley AJ, Smith MR. Diabetes and cardiovascular disease during androgen deprivation therapy for prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:4448–56. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.2497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Colquhoun AJ, Venier NA, Vandersluis AD, et al. Metformin enhances the antiproliferative and apoptotic effect of bicalutamide in prostate cancer. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2012;15:346–52. doi: 10.1038/pcan.2012.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Fig. 1 – Comparison of the development of castrate-resistant prostate cancer among patients who experience a prostate-specific antigen failure among the metformin, diabetic non-metformin, and nondiabetic groups. A simple Fischer exact test was performed showing p < 0.001 between all groups.