Abstract

Mast cells play a key role in modulation of stress-induced cutaneous inflammation. In this study we investigate the impact of repeated exposure to stress on mast cell degranulation, in both hairy and glabrous skin. Adult male Wistar rats were randomly divided into four groups: Stress 1 day (n = 8), Stress 10 days (n = 7), Stress 21 days (n = 6), and Control (n = 8). Rats in the stress groups were subjected to 2 h/day restraint stress. Subsequently, glabrous and hairy skin samples from animals of all groups were collected to assess mast cell degranulation by histochemistry and transmission electron microscopy. The impact of stress on mast cell degranulation was different depending on the type of skin and duration of stress exposure. Short-term stress exposure induced an amplification of mast cell degranulation in hairy skin that was maintained after prolonged exposure to stress. In glabrous skin, even though acute stress exposure had a profound stimulating effect on mast cell degranulation, it diminished progressively with long-term exposure to stress. The results of our study reinforce the view that mast cells are active players in modulating skin responses to stress and contribute to further understanding of pathophysiological mechanisms involved in stress-induced initiation or exacerbation of cutaneous inflammatory processes.

1. Introduction

Inflammatory skin diseases such as psoriasis, atopic dermatitis, seborrheic eczema, acne, prurigo nodularis, lichen planus, chronic urticaria, rosacea, and alopecia areata are common disorders involving increased medical and socioeconomic costs. Moreover, skin inflammation is involved in skin cancer, wound healing, and other major cutaneous pathophysiological processes. Thus, the mechanisms and microscopical changes involved in cutaneous inflammatory processes are topics of major interest in scientific research [1, 2].

One of the main factors that can be involved in the onset or worsening of skin inflammation is psychological stress [3–7] and mechanisms by which stress can cause activation or modulation of skin inflammatory processes are still not completely understood. There are complex interconnections between nervous system and skin, including direct bidirectional communication pathways through peripheral cutaneous nervous system and indirect pathways through endocrine and immune system [8]. Numerous interactions were identified between nervous system and various immune cells such as mast cells, neutrophils, macrophages, and T cells [9, 10] but mast cells appear to be the key element in modulation of stress-induced cutaneous inflammatory processes. Thus, there is a close anatomical association between mast cells and cutaneous nerve fibers [11] and mast cells activation plays an important role in the process of neurogenic inflammation [12]. Cutaneous neurogenic inflammation is a complex process characterized by increased vascular permeability and vasodilation [13–15] induced by neuromediators such as substance P (SP) and calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) that are released from cutaneous nerve endings. These neuromediators can also induce mast cell degranulation with subsequent histamine and proinflammatory cytokines release that can amplify the inflammatory skin process [16]. Previous studies have shown that stress exposure induces a significant increase in dermal mast cells degranulation, in number/density of nerve fibers immunoreactive for SP and contacts between mast cells and these fibers [17, 18]. Stress-induced increase in mast cell degranulation occurs rapidly [19] and is maintained over 7 days after exposure to stress [20]. Stress-induced mast cell degranulation is dependent on corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) but probably also involves the action of SP and neurotensin. Stress does not trigger an explosive mast cell degranulation, specific to anaphylactic reactions, but appears to act in a more subtle manner on mast cells, inducing predominantly intragranular changes [12].

In most previous studies stress exposure was limited to a single exposure and effects on dermal mast cells were investigated immediately after exposure to stress [12, 19] at 2 days [17, 18, 21] or 7 days after stress exposure [20]. Also, previous studies that investigated the effects of stress on cutaneous mast cells were restricted to hairy skin.

In this study we aim to investigate the impact of repeated exposure to stress on mast cell degranulation in both glabrous and hairy skin, thus allowing a dynamic study of stress effects on these important players in cutaneous inflammatory processes.

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Experimental Protocol

The study was conducted on 29 adult male Wistar rats, weighing 250–350 g, that were housed in clean cages, with a maximum of 5 rats per cage, in standard experimental conditions, including light-dark cycle of 12 h/12 h, temperature 22 ± 2°C, and free access to food and water. Experiments were conducted in accordance with European Guidelines on Laboratory Animal Care and were approved by the local ethics committee.

Rats were randomly divided into four groups: Stress 1 day (n = 8), Stress 10 days (n = 7), Stress 21 days (n = 6), and Control (n = 8). We used a restraint stress protocol in which the rats were placed in a well-ventilated restrainer that prevented movement without harming the animal. Rats from Stress 1 day group had a single exposure to restraint stress with duration of 2 hours. Rats from Stress 10 days and 21 days groups were exposed to stress protocol for 2 hours per day for a total of 10 and, respectively, 21 consecutive days. Rats from the Control group were maintained on standard experimental conditions.

After 24 h from the last exposure to stress tissue fragments of both hairy and glabrous skin from all animals were collected in order to assess cutaneous mast cell degranulation by light microscopy. Hairy skin was harvested from the ears and glabrous skin was harvested from the plantar region of posterior limbs. Additional samples of hairy and glabrous skin of approximately 1 mm3 were collected for ultrastructural examination via transmission electron microscopy (TEM). All reagents used for the experiments were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA), unless otherwise specified.

2.2. Preparation of Tissue Samples for Optical Microscopy

Fixation of tissue samples was done with 4% formaldehyde solution in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) 150 mM, pH 7.5, for a duration of 24 ± 1 hours. After dehydration through graded ethanols and clearing in butanol, representative fragments of glabrous and hairy skin were embedded in paraffin in a sectionable vegetal matrix, numbering a maximum of 12 samples per block, according to “tissue microarray” technology, as previously described [22]. The resulting paraffin blocks were sectioned semiserially at 4-5 μm.

2.3. Histochemical Stains to Highlight Mast Cells

Three different types of staining techniques were used to identify mast cells.

Giemsa Staining. Briefly, after dewaxing and rehydration, sections were stained for 60 minutes in Giemsa solution (Bio-Optica, Milan, Italy) in PBS (pH 6.8). Sections were differentiated with 1 : 1000 glacial acetic acid, dehydrated, cleared, and mounted.

Acidified Toluidine Blue Staining [23]. Deparaffinized and rehydrated sections were stained for 5 minutes in 0.02% toluidine blue solution, pH 3.2.

Alcian Blue-Safranin O Staining [24]. Following dewaxing and rehydration, sections were stained for 30 minutes with Alcian blue-Safranin O (0.36% and 0.18%) in 0.1 M acetate buffer solution, pH 1.42.

2.4. Histomorphometric Analysis of Optical Microscopy Images

The resulting slides were examined and photographed in a blinded fashion on an Olympus CKX41 microscope equipped with an SLR Olympus E330 digital camera. At least 5 random high power fields (400x) for every test sample were selected and photographed. The images were acquired in a format of 3136 × 2352 pixels using QuickPhoto 2.3 software and stored in the TIFF format. We performed the histomorphometric analysis of images in a blinded manner, using the image analysis software ImageJ 1.45. In the dermis we evaluated the percentage of degranulated mast cells from the total number of mast cells, in both glabrous and hairy skin. Degranulated mast cells were defined as mast cells with a reduced staining intensity in the cytoplasm and presenting extracellular granules in close proximity [12, 25–27]. A minimum of 5 microscopic fields and a minimum of 10 cells were assessed for each rat and each type of tissue.

2.5. Ultrastructural Cutaneous Aspects Assessed with Electron Microscopy

Fixation of tissue fragments was performed with 4% buffered glutaraldehyde followed by 1% buffered osmic acid. The 1 mm3 fragments were dehydrated in graded alcohols and embedded in Epon. Thin sections of 80 nm, double stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate, were prepared on a LKB ultramicrotome. The study was performed with a JEOL JEM 1011 electron microscope at 80 kV. All skin compartments were examined, with particular focus on mast cells, skin blood vessels, and nerve fibers.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

The normality and homogeneity distribution of data were assessed with Bartlett's test. We used Kruskal-Wallis test followed by 2-tailed multiple comparison test to evaluate differences between experimental groups. For each group, the results were presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). P values <0.05 were considered significant.

3. Results

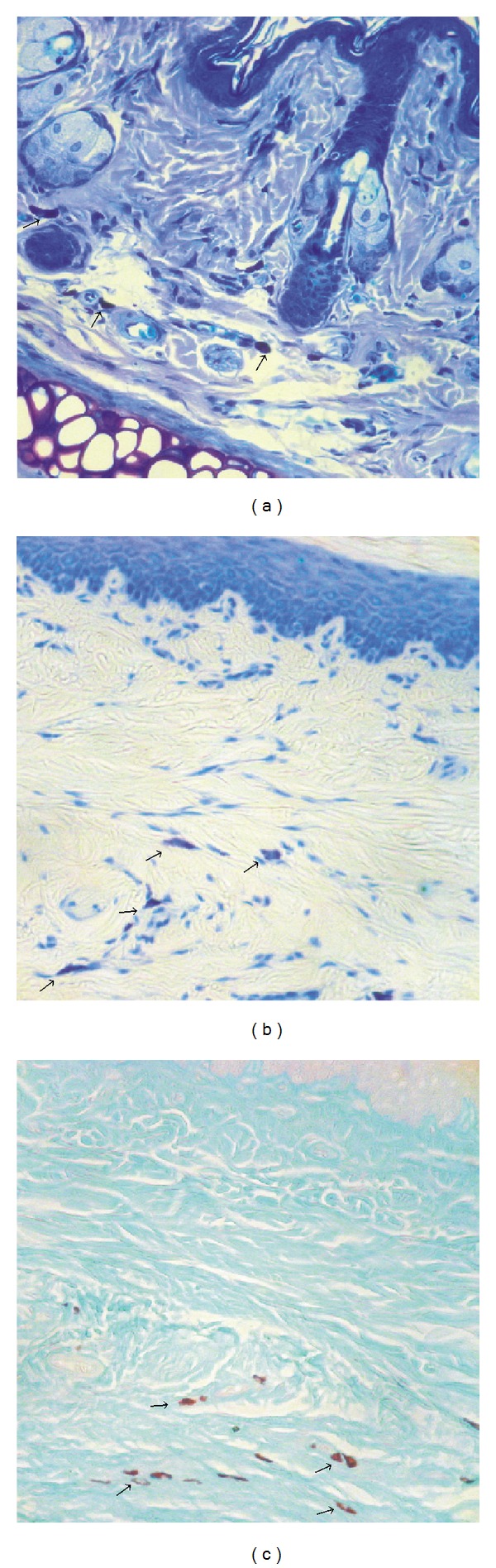

We carried out a preliminary assessment of the tissue slides processed using the three methods mentioned above for histochemical identification of mast cells: Alcian blue-Safranin O staining, acidified toluidine blue staining, and Giemsa staining (Figure 1). The most conclusive data were obtained on histological preparations stained with Alcian blue-Safranin O, and this method was further used to evaluate mast cell degranulation in skin tissue.

Figure 1.

Histochemical aspect of mast cells (→) with (a) Giemsa staining; (b) acidified toluidine blue staining; (c) Alcian blue-Safranin O staining. Magnification 400x.

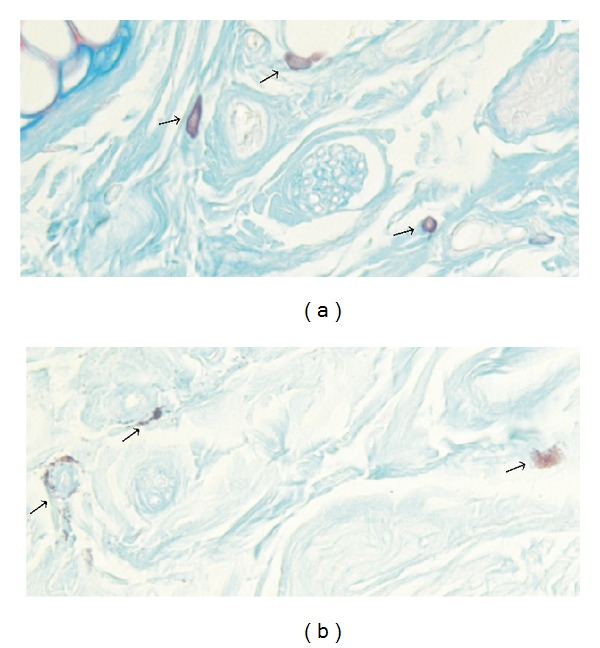

In all examined tissue samples mast cells were present in the dermis of both glabrous and hairy skin. Mast cells were typically located at the dermoepidermal junction and dermis-hypodermis interface. In addition, we identified an important number of mast cells organised near cutaneous nerve structures or blood vessels (Figures 2(a) and 2(b)).

Figure 2.

(a) Normal mast cells (→) localized near vasculonervous structures in hairy skin. Alcian blue-Safranin O staining. 400x magnification; (b) Degranulated mast cells (→) in immediate vicinity of vasculonervous structures in glabrous skin. Alcian blue-Safranin O staining. Magnification 400x.

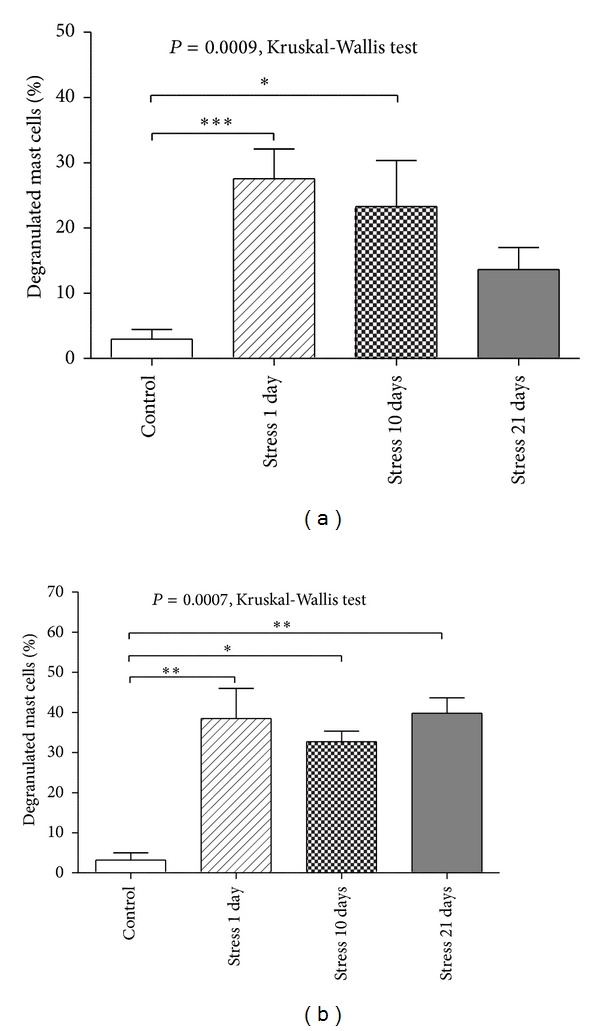

In glabrous skin, stress exposure increased the proportion of degranulated mast cells (P = 0.0009, Kruskal-Wallis test). Initial growth was important, from 2.95 ± 4.31% in the Control group to 27.57 ± 12.80% in the Stress 1 day group (P = 0.00081, two-tailed multiple comparison test). Prolonged exposure to stress was associated with a gradual return to normal values of the proportion of degranulated mast cells. Thus, for rats from Stress 10 days group the percentage of degranulated mast cells was 23.31 ± 18.65%, a value that is still significantly higher than Control group (P = 0.01649, two-tailed multiple comparison test). However, in laboratory animals from Stress 21 days group the percentage of degranulated mast cells was only 13.65 ± 8.16%, a value that is not statistically significant compared to Control group (P = 0.23840, two-tailed multiple comparison test) (see Figure 3(a)).

Figure 3.

Comparative analysis of the proportion of degranulated mast cells. (a) In glabrous skin, brief exposure to stress induced a significant increase in the proportion of degranulated mast cells and prolonged exposure to stress was associated with a gradual return to normal value of degranulated mast cells. (b) In hairy skin, acute exposure to stress induced an amplification of mast cell degranulation process that was maintained after prolonged exposure to stress. Error bars represent the standard error of the mean (SEM). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, two-tailed multiple comparison test.

In hairy skin, stress exposure also induced an increase in mast cells degranulation (P = 0.0007, Kruskal-Wallis test). As with glabrous skin, a single stress exposure led to a significant increase in mast cell degranulation, from 3.20 ± 5.04% in the Control group to 38.46 ± 21.23% in the Stress 1 day group (P = 0.00205, two-tailed multiple comparisons test). However, in contrast to glabrous skin, after prolonged stress exposure the percentage of degranulated mast cells in hairy skin remained high when compared to Control group. Thus, in Stress 10 days group the proportion of degranulated mast cells was 32.70 ± 7.01% (P = 0.02989, two-tailed multiple comparison test) and in Stress 21 days group the percentage of degranulated mast cells was 39.76 ± 9.42% (P = 0.00496, two-tailed multiple comparison test) (see Figure 3(b)).

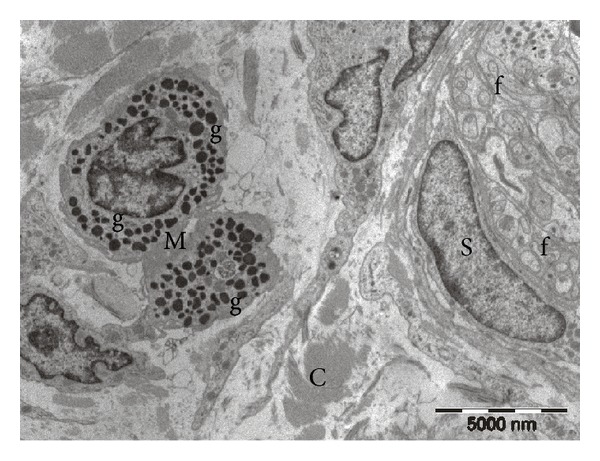

Investigation of glabrous and hairy skin samples by transmission electron microscopy confirmed the presence of mast cells in the dermis, adjacent to nerve fascicles and blood vessels. Often the distance between mast cells and nervous or vascular structures was less than 1–3 μm. In the samples from Control group, both in hairy and glabrous skin, mast cells had a normal appearance, with numerous intracytoplasmic electron-dense granules, uniform appearance, round-oval shape, and multiple cytoplasmic extensions (see Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Electron microscopy image from the rat control group. Two dermal mast cells (M) with uniform electron-dense granules (g), placed near a nerve bundle containing a Schwann cell (S) and unmyelinated nerve fibers (f). Collagen (C) in the surrounding background.

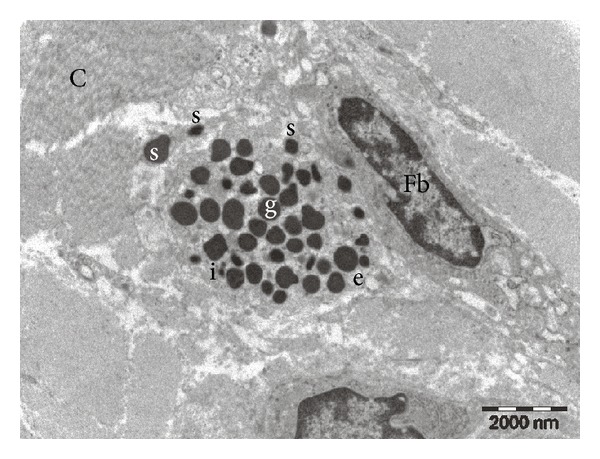

In rats subjected to a single exposure to stress, the electron microscopic appearance of dermal mast cells from both types of skin was changed compared to normal (see Figure 5). Elements specific for mast cell degranulation were observed, such as (i) granules that appear to be released in the extracellular environment, (ii) granules that are about to release their contents into extracellular environment, and (iii) merged intracytoplasmic granules. In addition, mast cells with irregular granules or granules emptied of content were identified, indicating a partial mast cell degranulation process.

Figure 5.

Electron microscopy picture from Stress 1 day rat group. Mast cell with dense granules (g), granules emptied of content (e), granules showing altered electron densities (i), and granules on the verge of releasing the content into the extracellular space (s). Collagen (C) and fibroblast (Fb).

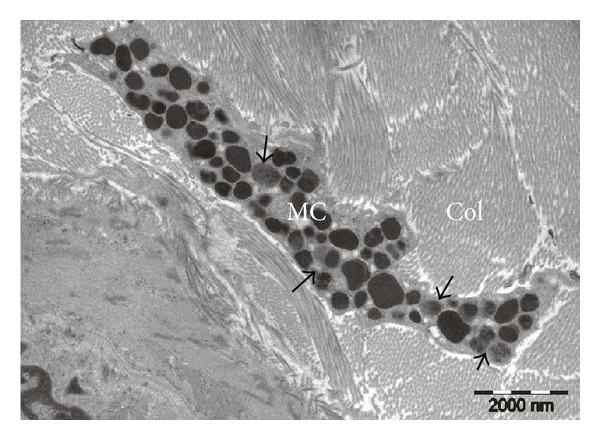

Electron microscopic evaluation of glabrous and hairy skin harvested from rats from Stress 10 days group showed predominantly mast cells with intracytoplasmic granules with low or uneven electron density, suggestive of either activation or partial degranulation. Also, sporadic granules that seemed on the verge of eliminating their content in the extracellular environment were identified. A similar appearance of mast cells was observed in glabrous and hairy skin samples collected from rats belonging to the Stress 21 days group (see Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Electron micrograph from Stress 21 days rat group. A dermal mast cell (MC) with dense granules and granules that show altered electron densities (arrows), indicating a process of mast cell activation. Collagen fibers (Col) in the surrounding background.

4. Discussion

Psychological stress may be involved in the modulation of cutaneous inflammation and its effects may vary depending on the duration and characteristics of the stressor. Thus, chronic stress has an immunosuppressive effect, while acute stress, although it induces a significant decrease in circulating immune cells by redirecting them to the skin, stimulates cell-mediated immunity in cutaneous tissue [28]. In addition, exposure to stress can lead to modulation of skin peptidergic innervation [21] and can induce the release of neuropeptides from peripheral nerve endings, leading to activation of neurogenic inflammation [17, 20], a process that involves mast cells activation [12]. Inflammatory processes of various skin disorders triggered or exacerbated by stress, such as atopic dermatitis and psoriasis, also have mast cell activation as a key mechanism [29–33].

The important role of mast cells in stress-induced activation of skin inflammation is suggested by their strategic location near cutaneous nerve structures and blood vessels and their complex interconnections with nerve fibers, immune cells, and keratinocytes [11, 34, 35].

Despite this, there are only a limited number of studies that investigated the effect of chronic stress on skin mast cells. One experimental study in rats showed that there is no statistically significant difference between control and chronic stressed groups regarding paw oedema induced by a mast cell degranulator compound [36]. Another study in patients with psoriasis showed that in noninvolved hairy skin of the arms and on the back chronic stress is associated with an increased number of inflammatory cells expressing neurokinin 1 receptor, most of them being mast cells [37].

The effect of acute stress on mast cell degranulation has been investigated in murine hairy skin. Previous studies, limited to a single stress exposure, highlighted a significant increase in dermal mast cells degranulation shortly after exposure to stress [12, 19] and lasting for over one week [20].

Our research assessed the impact of repeated stress exposure on mast cell degranulation in hairy and glabrous skin, moving a step forward from previous studies. We used a restraint stress model commonly used in scientific research, which induces a moderate intensity stress, largely psychological [38, 39]. Restraint stress has been used to study the effects of both acute [28, 40] and chronic stress [40, 41]. To study the acute stress, animals may be exposed to restraint stress in a single experimental session with duration between 60 minutes [40] and 2 hours [28]. For chronic stress induction, the duration of restraint may also vary from repeated exposure of 60 minutes per day for 10 consecutive days [40] to prolonged exposure, of 6 hours per day for 21 consecutive days [41]. Thus, our experimental group with a single experimental session of 2 hours may be classified as acute stress while the results achieved after a total of 10 and, respectively, 21 consecutive days of stress exposure are investigating the effects of chronic stress.

In our study acute stress induced a significant increase in the proportion of degranulated mast cells in both hairy and glabrous skin, confirming the results of previous research.

However, the effects of chronic stress were different in the two types of skin investigated. In glabrous skin chronic stress was associated with a slow return towards normal values of mast cells degranulation. In contrast, in hairy skin, the percentage of degranulated mast cells remained high even after 21 days of stress exposure. Another feature revealed in the chronic stress groups was the phenomenon of partial degranulation (mast cell activation), as described in previous studies [42, 43], in which the content of granules is only partially released in the extracellular environment.

The distinct impact of chronic stress on mast cells from glabrous and hairy skin may be explained by the different pattern of innervation [44–46] regarding both the myelinated nerve fibers [47] and the unmyelinated nociceptive nerve fibers [48]. Moreover, different functional features of Aδ and C nerve fibers innervating the human glabrous and hairy skin have been previously reported [49]. Unmyelinated type C and thin myelinated type Aδ nerve fibers are rich in various neuropeptides, such as SP and CGRP, and, together with mast cells, are key players in cutaneous neurogenic inflammation [50–52].

As already mentioned, there is a close connection between cutaneous nerve fibers and mast cells from both the morphological and the functional perspective. Thus, mast cells can be activated by neuropeptides, such as SP [53–55], neurotensin [12, 56], nerve growth factor (NGF) [57, 58], and pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide (PACAP) [59] released from skin nerve endings.

The effect of stress on skin mast cells appears to be mediated by the release of neuropeptides from cutaneous nerve endings. Stress induces a release of NGF and neurotensin [60, 61] and increases SP-positive nerve fibers and their contacts with mast cells in skin [17, 18, 21].

Another key player in stress-induced mast cell activation is CRH [12]. Under stress, CRH is secreted from hypothalamus and can also be released in the skin by activated nerve endings and local immune cells [62–65]. CRH activates skin mast cells in murine [66] and human skin [67] and also induces the development of mast cells from precursors in the human hair follicle mesenchyme [68].

The complexity of the relationships between nerve fibers and mast cells is further evidenced by research showing that mast cells may contain SP [69], NGF [70], and CRH [71]. Moreover, substances released by mast cells, such as histamine, serotonin, and proinflammatory cytokines, may have a modulatory action on nerve fibers function and neuropeptides effects [50, 72, 73].

5. Conclusions

The impact of stress on mast cell degranulation seems to be different, depending on the type of skin, glabrous or hairy, as well as on the duration of stress exposure. In the hairy skin acute stress induces an increased mast cell degranulation that persists even after prolonged exposure to stress, while in glabrous skin a short-term stress exposure has a strong stimulating effect of mast cell degranulation that subsides in intensity as exposure to stress persists. Thus, our findings could provide an explanation for the varying impact of stress on different dermatological diseases depending on the location of skin lesions or on the duration of exposure to stress [74, 75].

Our study contributes to the further understanding of the mechanisms involved in the initiation or exacerbation of cutaneous pathophysiological processes by stress. This is an area of active interest for the international scientific community that currently invests many efforts in developing more active and more specific pharmacological agents targeting the association of stress with inflammatory dermatological disorders.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by Grant PN-II-RU-TE-2011-3-0249 from the National University Research Council, Romania. Authors wish to thank Professor Leon Zagrean from the Center for Excellence in Neuroscience, “Carol Davila” University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Bucharest, and Professor Bogdan Amuzescu from the Department of Biophysics & Physiology, Faculty of Biology, University of Bucharest, for their support during the course of this work and Mrs. Elena Poenaru for statistical analysis.

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests regarding the publication of this paper.

References

- 1.Neagu M, Constantin C, Tanase C. Immune-related biomarkers for diagnosis/prognosis and therapy monitoring of cutaneous melanoma. Expert Review of Molecular Diagnostics. 2010;10(7):897–919. doi: 10.1586/erm.10.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ardigò M, Longo C, Cristaudo A, Berardesca E, Pellacani G. Evaluation of allergic vesicular reaction to patch test using in vivo confocal microscopy. Skin Research and Technology. 2012;18(1):61–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0846.2011.00531.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Koo J, Lebwohl A. Psychodermatology: the mind and skin connection. The American Family Physician. 2001;64(11):1873–1878. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arck P, Paus R. From the brain-skin connection: the neuroendocrine-immune misalliance of stress and itch. NeuroImmunoModulation. 2007;13(5-6):347–356. doi: 10.1159/000104863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tausk F, Elenkov I, Moynihan J. Psychoneuroimmunology. Dermatologic Therapy. 2008;21(1):22–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1529-8019.2008.00166.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Căruntu C, Ghiţă MA, Căruntuand A, Boda D. The role of stress in the multifactorial etiopathogenesis of acne. Romanian Medical Journal. 2011;58(2):98–101. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Căruntu C, Grigore C, Căruntu A, Diaconeasa A, Boda D. The role of stress in skin diseases. Medicina Internă: Internal Medicine. 2011;8(3):73–84. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brazzini B, Ghersetich I, Hercogova J, Lotti T. The neuro-immuno-cutaneous-endocrine network: relationship between mind and skin. Dermatologic Therapy. 2003;16(2):123–131. doi: 10.1046/j.1529-8019.2003.01621.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ferjan I, Lipnik-Štangelj M. Chronic pain treatment: the influence of tricyclic antidepressants on serotonin release and uptake in mast cells. Mediators of Inflammation. 2013;2013:7 pages. doi: 10.1155/2013/340473.340473 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ton BH, Chen Q, Gaina G, et al. Activation profile of dorsal root ganglia Iba-1 (+) macrophages varies with the type of lesion in rats. Acta Histochemica. 2013;115(8):840–850. doi: 10.1016/j.acthis.2013.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schmelz M, Petersen LJ. Neurogenic inflammation in human and rodent skin. News in Physiological Sciences. 2001;16(1):33–37. doi: 10.1152/physiologyonline.2001.16.1.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Singh LK, Pang X, Alexacos N, Letourneau R, Theoharides TC. Acute immobilization stress triggers skin mast cell degranulation via corticotropin releasing hormone, neurotensin, and substance P: a link to neurogenic skin disorders. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity. 1999;13(3):225–239. doi: 10.1006/brbi.1998.0541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jancsó N, Jancsó-Gábor A, Szolcsányi J. Direct evidence for neurogenic inflammation and its prevention by denervation and by pretreatment with capsaicin. British Journal of Pharmacology. 1967;31(1):138–151. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1967.tb01984.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chapman LF. Mechanisms of the flare reaction in human skin. Journal of Investigative Dermatology. 1977;69(1):88–97. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12497896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Căruntuand C, Boda D. Evaluation through in vivo reflectance confocal microscopy of the cutaneous neurogenic inflammatory reaction induced by capsaicin in human subjects. Journal of Biomedical Optics. 2012;17(8):7 pages. doi: 10.1117/1.JBO.17.8.085003.085003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bíró T, Maurer M, Modarres S, et al. Characterization of functional vanilloid receptors expressed by mast cells. Blood. 1998;91(4):1332–1340. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Arck PC, Handjiski B, Peters EMJ, et al. Stress inhibits hair growth in mice by induction of premature catagen development and deleterious perifollicular inflammatory events via neuropeptide substance P-dependent pathways. The American Journal of Pathology. 2003;162(3):803–814. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63877-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pavlovic S, Daniltchenko M, Tobin DJ, et al. Further exploring the brain-skin connection: stress worsens dermatitis via substance P-dependent neurogenic inflammation in mice. Journal of Investigative Dermatology. 2008;128(2):434–446. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5701079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kawana S, Liang Z, Nagano M, Suzuki H. Role of substance P in stress-derived degranulation of dermal mast cells in mice. Journal of Dermatological Science. 2006;42(1):47–54. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2005.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Arck PC, Handjiski B, Hagen E, Joachim R, Klapp BF, Paus R. Indications for a “brain-hair follicle axis (BHA)”: inhibition of keratinocyte proliferation and up-regulation of keratinocyte apoptosis in telogen hair follicles by stress and substance P. The FASEB Journal. 2001;15(13):2536–2538. doi: 10.1096/fj.00-0699fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Peters EMJ, Kuhlmei A, Tobin DJ, Müller-Röver S, Klapp BF, Arck PC. Stress exposure modulates peptidergic innervation and degranulates mast cells in murine skin. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity. 2005;19(3):252–262. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2004.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Musat-Marcu S, Gunter HE, Jugdutt BI, Docherty JC. Inhibition of apoptosis after ischemia-reperfusion in rat myocardium by cycloheximide. Journal of Molecular and Cellular Cardiology. 1999;31(5):1073–1082. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.1999.0939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Churukian CJ, Schenk EA. A toluidine blue method for demonstrating mast cells. Journal of Histotechnology. 1981;4(2):85–86. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Csaba G. Mechanism of the formation of mast-cell granules. II: cell-free model. Acta Biologica Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae. 1969;20(2):205–210. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kiernan JA. The involvement of mast cells in vasodilatation due to axon reflexes in injured skin. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Physiology and Cognate Medical Sciences. 1972;57(3):311–317. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.1972.sp002164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Spanos C, Pang X, Ligris K, et al. Stress-induced bladder mast cell activation: implications for interstitial cystitis. Journal of Urology. 1997;157(2):669–672. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Theoharides TC, Spanos C, Pang X, et al. Stress-induced intracranial mast cell degranulation: a corticotropin-releasing hormone-mediated effect. Endocrinology. 1995;136(12):5745–5750. doi: 10.1210/endo.136.12.7588332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dhabhar FS, Mcewen BS. Enhancing versus suppressive effects of stress hormones on skin immune function. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1999;96(3):1059–1064. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.3.1059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Katsarou-Katsari A, Filippou A, Theoharides TC. Effect of stress and other psychological factors on the pathophysiology and treatment of dermatoses. International Journal of Immunopathology and Pharmacology. 1999;12(1):7–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Church MK, Clough GF. Human skin mast cells: in vitro and in vivo studies. Annals of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology. 1999;83(5):471–475. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)62853-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Järvikallio A, Harvima IT, Naukkarinen A. Mast cells, nerves and neuropeptides in atopic dermatitis and nummular eczema. Archives of Dermatological Research. 2003;295(1):2–7. doi: 10.1007/s00403-002-0378-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Harvima IT, Nilsson G, Naukkarinen A. Role of mast cells and sensory nerves in skin inflammation. Giornale Italiano di Dermatologia e Venereologia. 2010;145(2):195–204. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Harvima IT, Nilsson G, Suttle M-M, Naukkarinen A. Is there a role for mast cells in psoriasis? Archives of Dermatological Research. 2008;300(9):461–478. doi: 10.1007/s00403-008-0874-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gomes AC, Gomes-Filho JE, Oliveira SHP. Mineral trioxide aggregate stimulates macrophages and mast cells to release neutrophil chemotactic factors: role of IL-1β, MIP-2 and LTB4. Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, Oral Pathology, Oral Radiology and Endodontology. 2010;109(3):e135–e142. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2009.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Suárez AL, Feramisco JD, Koo J, Steinhoff M. Psychoneuroimmunology of psychological stress and atopic dermatitis: pathophysiologic and therapeutic updates. Acta Dermato-Venereologica. 2012;92(1):7–15. doi: 10.2340/00015555-1188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Datti F, Datti M, Antunes E, Teixeira NA. Influence of chronic unpredictable stress on the allergic responses in rats. Physiology and Behavior. 2002;77(1):79–83. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(02)00811-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Remröd C, Lonne-Rahm S, Nordlind K. Study of substance P and its receptor neurokinin-1 in psoriasis and their relation to chronic stress and pruritus. Archives of Dermatological Research. 2007;299(2):85–91. doi: 10.1007/s00403-007-0745-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Berkenbosch F, Wolvers DAW, Derijk R. Neuroendocrine and immunological mechanisms in stress-induced immunomodulation. Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. 1991;40(4–6):639–647. doi: 10.1016/0960-0760(91)90286-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Glavin GB, Paré WP, Sandbak T, Bakke H-K, Murison R. Restraint stress in biomedical research: an update. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 1994;18(2):223–249. doi: 10.1016/0149-7634(94)90027-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.McDougall SJ, Paull JRA, Widdop RE, Lawrence AJ. Restraint stress: differential cardiovascular responses in Wistar-Kyoto and spontaneously hypertensive rats. Hypertension. 2000;35(1):126–129. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.35.1.126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Reagan LP, Rosell DR, Wood GE, et al. Chronic restraint stress up-regulates GLT-1 mRNA and protein expression in the rat hippocampus: reversal by tianeptine. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2004;101(7):2179–2184. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307294101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Crivellato E, Nico B, Mallardi F, Beltrami CA, Ribatti D. Piecemeal degranulation as a general secretory mechanism? Anatomical Record A: Discoveries in Molecular, Cellular, and Evolutionary Biology. 2003;274(1):778–784. doi: 10.1002/ar.a.10095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yang CQ, Wei YY, Zhong CJ, Duan LP. Essential role of mast cells in the visceral hyperalgesia induced by T. spiralis infection and stress in rats. Mediators of Inflammation. 2012;2012:8 pages. doi: 10.1155/2012/294070.294070 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.McGlone F, Vallbo AB, Olausson H, Loken L, Wessberg J. Discriminative touch and emotional touch. Canadian Journal of Experimental Psychology. 2007;61(3):173–183. doi: 10.1037/cjep2007019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Löken LS, Evert M, Wessberg J. Pleasantness of touch in human glabrous and hairy skin: order effects on affective ratings. Brain Research. 2011;1417:9–15. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2011.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ackerley R, Saar K, McGlone F, Backlund Wasling H. Quantifying the sensory and emotional perception of touch: differences between glabrous and hairy skin. Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience. 2014;8, artcile 34:12 pages. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2014.00034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nolano M, Provitera V, Crisci C, et al. Quantification of myelinated endings and mechanoreceptors in human digital skin. Annals of Neurology. 2003;54(2):197–205. doi: 10.1002/ana.10615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Davis KD. Cold-induced pain and prickle in the glabrous and hairy skin. Pain. 1998;75(1):47–57. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(97)00203-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Granovsky Y, Matre D, Sokolik A, Lorenz J, Casey KL. Thermoreceptive innervation of human glabrous and hairy skin: a contact heat evoked potential analysis. Pain. 2005;115(3):238–247. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2005.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Roosterman D, Goerge T, Schneider SW, Bunnett NW, Steinhoff M. Neuronal control of skin function: the skin as a neuroimmunoendocrine organ. Physiological Reviews. 2006;86(4):1309–1379. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00026.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Steinhoff M, Ständer S, Seeliger S, Ansel JC, Schmelz M, Luger T. Modern aspects of cutaneous neurogenic inflammation. Archives of Dermatology. 2003;139(11):1479–1488. doi: 10.1001/archderm.139.11.1479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Janig W, Lisney SJW. Small diameter myelinated afferents produce vasodilatation but not plasma extravasation in rat skin. Journal of Physiology. 1989;415:477–486. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1989.sp017732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fewtrell CMS, Foreman JC, Jordan CC. The effects of substance P on histamine and 5-hydroxytryptamine release in the rat. Journal of Physiology. 1982;330:393–411. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1982.sp014347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Matsuda H, Kawakita K, Kiso Y, Nakano T, Kitamura Y. Substance P induces granulocyte infiltration through degranulation of mast cells. Journal of Immunology. 1989;142(3):927–931. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Li W-W, Guo T-Z, Liang D-Y, Sun Y, Kingery WS, Clark JD. Substance P signaling controls mast cell activation, degranulation, and nociceptive sensitization in a rat fracture model of complex regional pain syndrome. Anesthesiology. 2012;116(4):882–895. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e31824bb303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Carraway R, Cochrane DE, Lansman JB. Neurotensin stimulates exocytotic histamine secretion from rat mast cells and elevates plasma histamine levels. Journal of Physiology. 1982;323:403–414. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1982.sp014080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bienenstock J, Tomioka M, Matsuda H. The role of mast cells in inflammatory processes: evidence for nerve/mast cell interactions. International Archives of Allergy and Applied Immunology. 1987;82(3-4):238–243. doi: 10.1159/000234197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tal M, Liberman R. Local injection of nerve growth factor (NGF) triggers degranulation of mast cells in rat paw. Neuroscience Letters. 1997;221(2-3):129–132. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(96)13318-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ødum L, Petersen LJ, Skov PS, Ebskov LB. Pituitary adenylate cyclase activating polypeptide (PACAP) is localized in human dermal neurons and causes histamine release from skin mast cells. Inflammation Research. 1998;47(12):488–492. doi: 10.1007/s000110050363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.de Simone R, Alleva E, Tirassa P, Aloe L. Nerve growth factor released into the bloodstream following intraspecific fighting induces mast cell degranulation in adult male mice. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity. 1990;4(1):74–81. doi: 10.1016/0889-1591(90)90008-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Alysandratos KD, Asadi S, Angelidou A, et al. Neurotensin and CRH interactions augment human mast cell activation. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(11):9 pages. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0048934.e48934 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Karalis K, Muglia LJ, Bae D, Hilderbrand H, Majzoub JA. CRH and the immune system. Journal of Neuroimmunology. 1997;72(2):131–136. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(96)00178-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lytinas M, Kempuraj D, Huang M, Boucher W, Esposito P, Theoharides TC. Acute stress results in skin corticotropin-releasing hormone secretion, mast cell activation and vascular permeability, an effect mimicked by intradermal corticotropin-releasing hormone and inhibited by histamine-1 receptor antagonists. International Archives of Allergy and Immunology. 2003;130(3):224–231. doi: 10.1159/000069516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Theoharides TC, Alysandratos K-D, Angelidou A, et al. Mast cells and inflammation. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta: Molecular Basis of Disease. 2012;1822(1):21–33. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2010.12.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.van Diest SA, Stanisor OI, Boeckxstaens GE, de Jonge WJ, van den Wijngaard RM. Relevance of mast cell-nerve interactions in intestinal nociception. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta: Molecular Basis of Disease. 2012;1822(1):74–84. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2011.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Theoharides TC, Singh LK, Boucher W, et al. Corticotropin-releasing hormone induces skin mast cell degranulation and increased vascular permeability, a possible explanation for its proinflammatory effects. Endocrinology. 1998;139(1):403–413. doi: 10.1210/endo.139.1.5660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Crompton R, Clifton VL, Bisits AT, Read MA, Smith R, Wright IMR. Corticotropin-releasing hormone causes vasodilation in human skin via mast cell-dependent pathways. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2003;88(11):5427–5432. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-030377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ito N, Sugawara K, Bodó E, et al. Corticotropin-releasing hormone stimulates the in situ generation of mast cells from precursors in the human hair follicle mesenchyme. Journal of Investigative Dermatology. 2010;130(4):995–1004. doi: 10.1038/jid.2009.387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Toyoda M, Makino T, Kagoura M, Morohashi M. Immunolocalization of substance P in human skin mast cells. Archives of Dermatological Research. 2000;292(8):418–421. doi: 10.1007/s004030000149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Xiang Z, Nilsson G. IgE receptor-mediated release of nerve growth factor by mast cells. Clinical and Experimental Allergy. 2000;30(10):1379–1386. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2222.2000.00906.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kempuraj D, Papadopoulou NG, Lytinas M, et al. Corticotropin-releasing Hormone and its structurally related urocortin are synthesized and secreted by human mast cells. Endocrinology. 2004;145(1):43–48. doi: 10.1210/en.2003-0805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Theoharides TC, Donelan JM, Papadopoulou N, Cao J, Kempuraj D, Conti P. Mast cells as targets of corticotropin-releasing factor and related peptides. Trends in Pharmacological Sciences. 2004;25(11):563–568. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2004.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Asadi S, Alysandratos K-D, Angelidou A, et al. Substance P (SP) induces expression of functional corticotropin-releasing hormone receptor-1 (CRHR-1) in human mast cells. Journal of Investigative Dermatology. 2012;132(2):324–329. doi: 10.1038/jid.2011.334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Heller MM, Lee ES, Koo JY. Stress as an influencing factor in psoriasis. Skin Therapy Letter. 2011;16(5):1–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Niemeier V, Nippesen M, Kupfer J, Schill W-B, Gieler U. Psychological factors associated with hand dermatoses: which subgroup needs additional psychological care? British Journal of Dermatology. 2002;146(6):1031–1037. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2002.04716.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]