Summary

Using small-angle x-ray and neutron scattering (SAXS/SANS) in combination with analytical centrifugation and light scattering, we have determined the solution properties of PFV IN alone and its synaptic complex with processed U5 viral DNA and related these properties to models derived from available crystal structures. PFV IN is a monomer in solution and SAXS analysis indicates an ensemble of conformations that differ from that observed in the crystallographic DNA-bound state. Scattering data indicate that the PFV intasome adopts a shape in solution that is consistent with the tetrameric assembly inferred from crystallographic symmetry and these properties are largely preserved in the presence of divalent ions and clinical strand transfer inhibitors. Using contrast variation methods, we have reconstructed the solution structure of the PFV intasome complex and have located the distal domains of IN that were unresolved by crystallography. These results provide important insights into the architecture of the retroviral intasome.

Introduction

A central event in the retroviral life cycle is the integration of viral cDNA into the host chromosome (Vogt, 1997; Varmus et al., 1989). Retroviral integrases (IN) mediate this event by recognizing specific attachment sites at the end of long terminal repeat (LTR) regions of the viral genome (U5 and U3) to catalyze two distinct chemical reactions: a 3′ cleavage reaction that exposes the 3′-OH groups of the conserved CA dinucleotide, and a strand transfer step that inserts these 3′ termini of the viral cDNA into the host chromosome via a transesterifcation reaction. These reactions are catalyzed by oligomers of integrase that exist as parts of distinct nucleoprotein intermediates: a stable synaptic complex (SSC), in which two viral DNA ends are associated with a tetramer of IN, a target capture complex (TCC), in which the SSC binds to target DNA, and the strand transfer complex (STC), where the viral DNA ends are subsequently integrated into the target DNA (Li et al., 2006). Inhibitors that target these nucleoprotein complexes in HIV, such as Raltegravir and Eltegravir, are effective in the clinical setting (Arts and Hazuda, 2012).

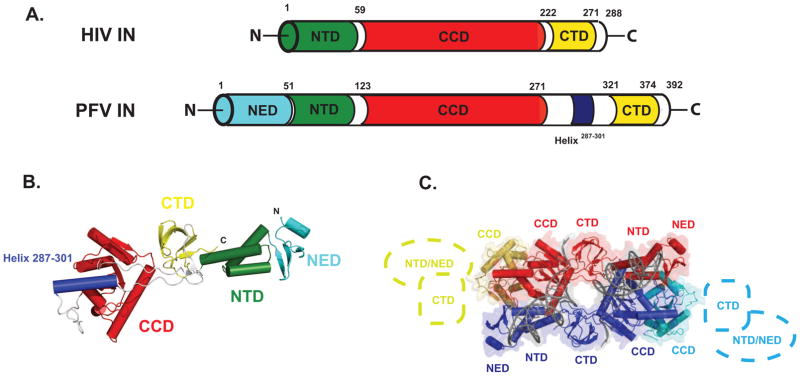

All retroviral INs share three domains: an N-terminal domain (NTD), a catalytic core domain (CCD), and a C-terminal domain (CTD) (Fig. 1A). The NTD contains conserved histidine and cysteine residues that bind Zn2+, and the domain plays a role in oligomerization and the enzyme’s catalytic function. The CCD contains an RNase H-like fold, well-conserved among the retroviral integrases, with conserved D-D-E active site residues common to polynucleotidyl transferases. In contrast, the CTD is poorly conserved among the retroviral integrases, featuring an SH3-like fold that has been implicated in DNA binding and tetramerization (Jenkins et al., 1996). INs from Spumavirus and Gammaretrovirus are further distinguished by the presence of N-terminal extension domains (NEDs) that precede the conserved NTDs (Hare et al., 2010). Many one and two-domain high resolution structures of HIV IN and other related retroviruses, both alone and in complex with the integrase binding domain (IBD) of the host factor LEDGF are now available (for a recent review, see Jaskolski et al., 2009).

Figure 1. Construct of PFV IN used in this study.

A. Comparison of the HIV and PFV IN domain structures. B. PFV IN Active Monomer Structure. C. Intasome structure (PDB 3L2Q), as inferred from crystallographic symmetry. The active DNA-bound monomers are shown in red and blue, respectively. Colored in yellow and cyan are the inactive monomers. Cartoons depict the missing NED/NTD and CTD domains not resolved in the electron density. See also Fig. S1.

Our understanding of the mechanism of retroviral integration advanced with the determination of the crystal structures of prototype foamy virus (PFV) IN in complex with minimal processed viral U5 DNA (Fig. 1B–C and Fig. S1)(Hare et al., 2010; Maertens et al., 2010). These intasome structures provide molecular insights into the sequential steps of retroviral integration and its inhibition, including the first views of the SSC, TCC, and STC intermediate states, all in the presence and absence of divalent ions and clinical inhibitors. However, little is known about the properties of these nucleoprotein assemblies as they exist in solution. In all of the available PFV intasome crystal structures, the same quaternary arrangement is observed via crystallographic symmetry: two integrase subunits comprise the core of the complex, providing all of the protein-protein interactions which hold the tetrameric assembly together, the interactions with viral DNA, and the active sites that mediate integration. The two remaining subunits, in contrast, are not fully resolved, as only the CCD domains are observed at the distal ends of the complex, with the NTD and CTD unobserved in the electron density (Fig. 1C). The roles of these inactive subunits in complex formation and retroviral integration are unknown. Furthermore, it is not known if drug-bound nucleoprotein complexes have quaternary properties that are distinct from their native form; in available PFV structures with inhibitors bound, no large conformational differences have been observed within the crystal lattice. The PFV integrase model system provides an ideal opportunity to directly relate the solution properties of these nucleoprotein assemblies with and without bound inhibitors to the known atomic resolution models of the intermediates involved in retroviral integration.

In this study, we report the solution properties of PFV IN and its complex with processed U5 viral DNA. Using size-exclusion chromatography in-line with multi-angle light scattering (SEC-MALS) and analytical ultracentrifugation, we have established the mass, stochiometry, and hydrodynamic properties of PFV IN and its complex with processed U5 DNA. We have used small-angle x-ray and neutron scattering (SAXS/SANS) analyses of these preparations to investigate the effects of divalent ions and strand transfer inhibitors on overall shape. Contrast variation analysis using SAXS and SANS data together has allowed us to locate previously unobserved domains in the PFV intasome and to directly reconcile the solution conformations of these macromolecules with available crystallographic models. Our studies reveal properties not apparent from available structures that can be directly related to other retroviral integrases, including HIV.

Results

PFV IN is monomeric prior to binding DNA

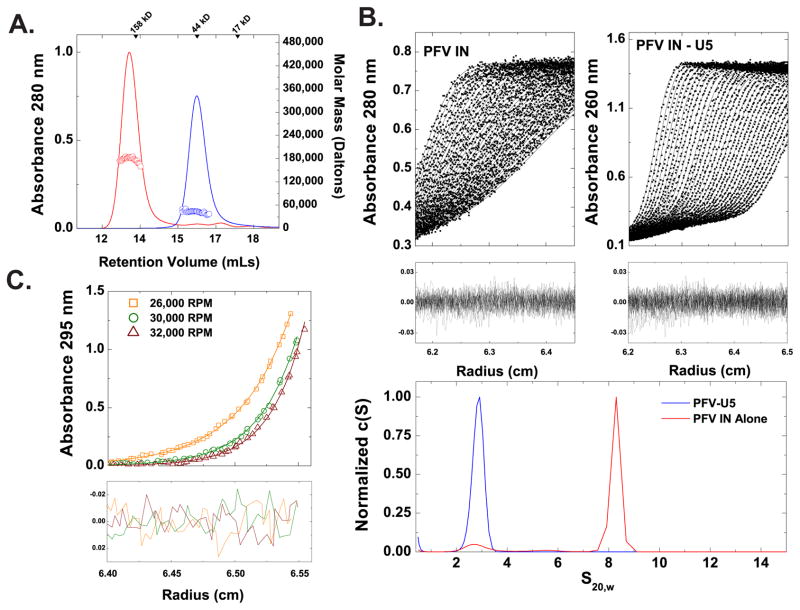

The first studies on the solution behavior of PFV IN alone reported a monomer-dimer equilibrium in solution, with a 20–30 μM Kd by fluorescence methods (Delelis et al., 2008). We examined a range of concentrations of PFV IN using complementary approaches. By size-exclusion chromatography in-line with multi-angle light scattering (SEC-MALS), only monomers are observed at concentrations up to 10 mg/mL (~225 μM) (Fig. 2A), affirming the suitability of these preparations for small-angle scattering analysis (Rambo and Tainer, 2010a). Modeling the Lamm equation to the sedimentation velocity data mirrors these observations, with only a single species observed at 2.9 S20,w and a frictional ratio (f/fo) of 1.4 (Fig. 2B). Combining these sedimentation velocity results with parameters derived from in-line quasi-elastic light scattering allows for a determined mass of 45kD (Siegel and Monty, 1966), consistent with the monomeric size determined from multi-angle light scattering. Using sedimentation equilibrium analysis, the best global fit over a range of concentrations and speeds at 25°C is also for a single-species monomer (Fig. 2C and Table S1).

Figure 2. Hydrodynamic Properties of PFV IN and PFV intasome.

A. SEC-MALS analysis of PFV IN (blue) and PFV intasome (red). The ABS280 elution profile from a Superdex 200 analytical column at 25°C is shown as solid lines. Representative mass profiles determined by light scattering are shown as red (PFV intasome, Mw = 178,800 ± 7,500, n=3) or blue squares (PFV IN, Mw = 43,800 ± 3,200, n=10). B. Sedimentation velocity analysis. Shown in upper two panels are the experimental data collected for PFV IN alone (upper left) and PFV Intasome (upper right), rendered as black points on solid black lines that are the fits to the Lamm equation (RMSDs of 0.007 and 0.008, respectively). Each boundary shown corresponds to a 30-s time interval; data are shown only for the initial boundaries. Residuals, showing the agreement between the absorbance data collected and the theoretical fit, are shown below each panel as a function of the radius of the experimental cell. Shown in the lowest subpanel are the derived c(S) distributions for PFV IN (blue line, S20w = 2.9) and PFV intasome (red line, S20w = 8.5). C. Sedimentation equilibrium analysis of PFV IN. Global fits were performed at three concentrations at three rotor speeds and are best fit to a single-species monomer model; rotor speeds are denoted in the figure legend. Top panels show radial absorbance data (symbols) and single-species model fits (lines); lower panels show residuals from the model fit. A summary of the biophysical parameters derived from these analyses is shown in Table S1.

SAXS analysis of PFV IN

The solution properties of PFV IN were further investigated using small-angle x-ray scattering (SAXS). Representative scattering data are shown in Fig. 3A. Guinier plots are linear for each of the concentrations analyzed, and the parameters derived are consistent with those from GNOM analysis, indicating monodispersity (Table 1 and Table S2). Mass determination by comparing the intensity of scattering extrapolated to zero angle (I(0)) with a protein standard of known concentration and mass also indicated monomers (Table S2). Three different preparations of recombinant PFV were analyzed at four different experimental sources, including both x-ray and neutron scattering (Tables 1, 2, S2 and S3). The radius of gyration (Rg) for the monomer is constant over the range of concentrations tested (Fig. 3B and Table S2), and Kratky plot analyses indicate a folded macromolecule.

Figure 3. SAXS of PFV IN.

A. Representative SAXS data from PFV IN, shown as the recorded intensity as a function of q (A−1), where q=4πsinθ/λ and 2θ is the scattering angle. Error bars represent plus and minus the combined standard uncertainty of the data collection B. In the inset, radius of gyration (Rg) plotted as a function of protein concentration. Experimental sources where data were recorded is noted in the figure legend. C. P(r) analysis of SAXS data recorded for PFV IN at 5 mg/mL (blue line). Shown in red is P(r) function calculated for the active monomer of PFV IN observed within the crystal lattice of PDB 3L2Q. See Fig. S2 for SAXS reconstructions based on this data.

Table 1.

Parameters derived from SAXS for PFV IN and PFV intasome (see also Table S2)

| Sample | Source | Concentration (mg/mL)a | Rg (Å)b | Dmax(Å)b | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PFV IN | ALS SIBYLS (SAXS) | 5 | 37.4 ± 0.1 | 135 | ||

| 4 | 38.5 ± 0.1 | 140 | ||||

| 3 | 36.8 ± 0.1 | 135 | ||||

| 2 | 35.9 ± 0.2 | 140 | ||||

| inf. | 34.9 ± 0.2 | 140 | ||||

| NIST NG-3 (SANS) | 6.2 | 37.4 ± 2.5 | 140 | |||

| PFV - U5 | Cornell G1 (SAXS) | 10 | 50.0 ± 0.1 | 180 | ||

| 5 | 49.8 ± 0.2 | 180 | ||||

| ALS SIBYLS (SAXS) | 3 | 48.0 ± 0.1 | 165 | |||

| 1.5 | 46.2 ± 0.2 | 165 | ||||

| +10 mM MgCl2 | 3 | 50.4 ± 0.2 | 165 | |||

| 1.5 | 46.2 ± 0.2 | 165 | ||||

| +10 mM MgCl2 & 5 mM L-791-833 | 3 | 49.6 ± 0.1 | 165 | |||

| 2 | 50.7 ± 0.2 | 175 | ||||

| 1 | 50.2 ± 0.4 | 175 | ||||

| +10 mM MgCl2 & 5 mM Raltegravir | 3 | 48.6 ± 0.3 | 170 | |||

| 2 | 49.7 ± 0.2 | 175 | ||||

| U5 Alone | 2 | 19.8 ± 0.1 | 70 | |||

| 1 | 19.9 ± 0.1 | 65 |

as determined by I(0) analysis using a known protein standard (protein alone), Bradford assay (protein-DNA complex) or by theoretical extinction coefficient (DNA alone).

as determined using GNOM (Semenyuk and Svergun, 1991). An extended table for parameters derived from SAXS is provided in Table S2.

Table 2.

Parameters derived from SANS for the PFV Intasome (see also Table S3)

| Source | H2O:D2O | Concentration (mg/mL) | Rg (Å)b | Dmax(Å)b |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NIST NG-3 (SANS) | 0% D2O | 6.7 | 51.6 ± 0.3 | 155 |

| 0% D2O | 3.9 | 49.1 ± 1.6 | 155 | |

| 20% D2O | 7.3 | 53.7 ± 2.5 | 175 | |

| 65% D2O | 8.3 | 52.9 ± 0.6 | 160 | |

| 80% D2O | 7.7 | 53.0 ± 0.3 | 165 | |

| 90% D2O | 7.8 | 51.3 ± 0.3 | 160 | |

| 90% D2O | 3.9 | 49.1 ± 0.6 | 160 | |

| Stuhrmann Relationshipc | std. err. | |||

| Rc (Å) | 50.8 | ± 0.9 | ||

| Protein Rg (Å) | 53.7 | ± 1.5 | ||

| α | 1.2 | ± 158.4 | ||

| β | −473.8 | ± 323.0 | ||

| Parallel Axis Theoremc | ||||

| Protein Rg (Å) | 56.6 | ± 3.4 |

Determined by Bradford protein assay

Determined by GNOM analysis (Semenyuk and Svergun, 1991)

Determined by MuLCH analysis (Whitten et al., 2008)

The hydrodynamic parameters of a PFV monomer calculated from PFV intasome crystal structure coordinates largely agree with the sedimentation coefficient (S20,w) and frictional coefficient (f/fo) determined by sedimentation velocity (Table 3). However, the calculated Stokes radius (Rs) is larger than that observed by gel filtration. SAXS data support a similar conclusion: data extrapolated to infinite dilution indicate that both the Rg and maximum dimension (Dmax) of the IN monomer differ from that predicted from the available crystallographic structure of intact IN (Fig. 3C). These comparisons indicate a difference in monomeric structure in solution between the DNA-bound and unbound forms.

Table 3.

Comparison of calculated properties of structural models with their experimental values

| Rg (Å) | Dmax (Å) | Rs (Å) | S | f/fo | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PFV IN Alone | |||||

| Model Properties | |||||

| Crystallographic Active Subunit | 35.8 | 122 | 40.7 | 2.5 | 1.2 |

| Best Single State Solution | 38.6 | 144 | 42.7 | 2.4 | 1.4 |

| MES Solutions: | |||||

| Model 1 | 38.8 | 140 | 43.9 | 2.3 | 1.3 |

| Model 2 | 37.7 | 126 | 42.4 | 2.4 | 1.2 |

| Model 3 | 63.3 | 205 | 50.9 | 2.0 | 1.5 |

| Model 4 | 34.4 | 126 | 37.3 | 2.7 | 1.2 |

| Inactive Subunit in SAXS/SANS-derived Intasome | 31.3 | 107 | 39.3 | 2.6 | 1.3 |

| Experimental | 34.9 | 140 | 28.7 | 2.9 | 1.4 |

| PFV Intasome | |||||

| Model Properties | |||||

| Starting Extended Model | 62.2 | 267 | 71.4 | 6.8 | 1.4 |

| SAXS/SANS derived Model | 57.2 | 215 | 65.8 | 7.4 | 1.2 |

| Experimental | 50.0 | 180 | 51.6 | 8.5 | 1.6 |

| MONSA Bead Model | 46.4 | 192 | 52.3 | 9.2 | 1.4 |

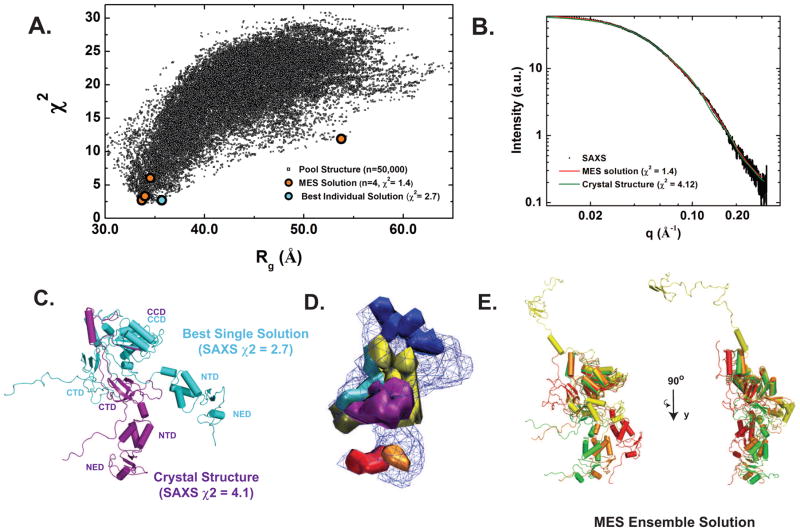

Shape reconstruction algorithms using scattering data allow for direct reconciliation of available atomic structures with their solution properties. However, low resolution models of PFV IN reconstructed from SAXS data failed to produce a consensus solution, as indicated by large normalized spatial discrepancy (NSD) figures and visual disparity between individual reconstructions (Fig. S2). These results indicated that an alternative approach was necessary to reconcile atomic structure with solution properties. To accomplish this, we implemented an atomistic modeling approach (Curtis et al., 2012) which involved sampling many conformations by molecular Monte Carlo and energy minimization and comparing the corresponding theoretical SAXS profiles to the experimental data. To generate a conformational ensemble, the backbone dihedral angles of the linkers connecting NTD and CTD to the CCD and terminal regions were allowed to vary in a manner consistent with their lack of secondary structure, predicted mobility, and disorder predicted by bioinformatics.

From a pool of over 50,000 theoretical structures that ranged in Rg from 34 Å to 65 Å Fig. 4A), the best fit structure (χ2=2.7, Fig. 4C) shows an extended conformation distinct from the starting model. However, solution scattering in this case more likely represents the average of many different conformations (Bernado et al., 2012). An analysis of the range of structures that correspond to the ensemble of best fit structures (where χ2 < 10) is shown as isodensity plots shown in Fig. 4D. Since the physical dimensions of the ensemble covered a much larger region of configurational space than that found for the best fit structures (Fig. S2), our analysis indicates that PFV IN adopts a compact subset of configurations relative to those considered by allowing flexible inter-domain linkers.

Figure 4. Atomistic Modeling of PFV IN.

A. Plot of the Rg values for all 50,000 models obtained by conformational sampling versus their correlation with the experimental SAXS data (as measured by χ2). The values for the best single solution (cyan circles) and the conformational ensemble with the four select conformers (orange circles) are indicated. B. The ensemble fit to the experimental data (black) is shown as a red line on a plot of intensity versus q. The theoretical scattering from the crystallographic conformation of PFV IN is shown as a green line. C. Comparison of the crystallographic configuration of PFV IN (magenta) with its best single state solution (cyan), as derived from conformational analysis. D. Structure Density Plot. Isodensity surface plot showing the conformation space occupied by the best fit structures of the ensemble with χ2 < 10.0 (blue mesh). Further indicated as solid densitites is the allowed variability in subregions of the structure: residues 1-10 (red), 47-51 (orange), 102-125 (yellow), 270-287 (green), 302-321 (blue), 326-346 (cyan), and 375-395 (purple). E The ensemble solution, shown at orthogonal angles and aligned relative to the CCD. The calculated contributions of the ensemble to its scattering are: Model 1 (red), Rg of 38.8 Å (χ2 = 2.72, 27.0% of the contributing scatter), Model 2 (orange), Rg of 37.7 Å (χ2 = 3.31, 41.0%), Model 3 (yellow), Rg of 63.3 Å (χ2 = 11.9, 8.0%), and Model 4 (green), Rg of 34.4 Å (χ2 = 6.03, 22.0%).

We next applied the minimal ensemble search (MES) method to the pool of structures created, which identifies a minimal ensemble of structures required to best describe the experimental data using a genetic algorithm (Pelikan et al., 2009). Using this approach, a minimal ensemble of four selected conformers greatly improved the concordance with the experimental data (x2=1.4) and suggests that PFV IN exists as a relatively compact ensemble where the CTD and NTD are flexibly linked to the CCD (Fig 4). The calculated solution properties of these models, both individually and as an ensemble, are consistent with the solution properties of PFV IN determined by analytical centrifugation, light scattering, and SAXS (Table 3). Combined, these results indicate that IN undergoes a significant conformational change upon binding to DNA, oligomerization, and assembly of the intasome.

Solution Structures of the PFV intasome

We next employed complementary approaches to confirm the stochiometry of the intasome. Using the Siegel and Monty relationship with centrifugation and quasi-elastic light scattering data, we estimated a molecular weight of 195 kD for the complex, in good agreement with the 4:2 IN:DNA stochiometry inferred from crystallography and indicated by biochemical data from different species of IN (Table S1)(Bao et al., 2002; Faure et al., 2005; Li et al., 2006). Further corroborating these results are SEC-MALS analyses using a mass-averaged dn/dc based on this stochiometry, which provides a calculated Mw of ~185 kD at peak value (Fig. 2A). The PFV intasome is discrete and monodisperse in solution, with no evidence of higher order species or partially assembled intermediates (Fig. 2B).

To investigate the molecular shape of this complex in solution, x-ray scattering experiments were carried out on intasome preparations across a range of concentrations (1–10 mg/mL) at two different synchrotron sources (Fig. 5A, Table 1, and Table S2). Scattering data were measured for complexes in the presence and absence of Mg2+ and the clinical inhibitors Raltegravir (Havlir, 2008) and L-731,988 (Espeseth et al., 2000). Because the properties of the PFV intasome were nearly identical in these different solution conditions as evidenced by P(r) analysis of SAXS data (Fig. 5B), we limited our subsequent scattering analyses to the apo form of the intasome.

Figure 5. SAXS of PFV intasome.

A. Representative SAXS data from the PFV intasome, shown as recorded intensity as a function of q. Error bars represent plus and minus the combined standard uncertainty of the data collection. B. P(r) analyses of PFV intasome in different solution conditions, including divalent ion and strand transfer inhibitors. C. Initial extended model of the PFV intasome, representing the complete inventory of the 4:2 protein-DNA assembly. Shaded in boxes are the NTD and CTD domains from the inactive subunits missing from available crystallographic structures that were varied in conformational sampling. D. Plot of Rg values for 50,000 conformations created by introducing torsional degrees of freedom in the linkers connecting NTD and CTD to the CCD in the inactive subunits. A horizontal black line corresponds to the Rg derived from SAXS for the PFV intasome. See also Fig. S3.

For our analysis, we constructed a model of the PFV intasome that includes the missing NTDs and CTDs (Fig. 5C). These domains were generated by applying the local two-fold symmetry operation that relates the active and inactive CCD subunits. Hence, the initial modeled NTD and CTD positions are related by two-fold symmetry to the corresponding domains in the intact subunits (Fig S3). In this extended configuration, the complete intasome model has a maximum dimension of 250 Å and a calculated Rg of 58 Å. In contrast, x-ray scattering data indicates that the intasome has an Rg of ~50 Å and maximum dimension of 180 Å, parameters which are both significantly smaller than that predicted for the extended configuration shown in Fig. 5C. This analysis indicates that the components of the complex are, on average, positioned closer to the center of mass of the particle than suggested by the extended arrangement. To examine the possibility that the inactive subunit NTD and CTD domains are disordered, we generated 50,000 models, which differ in the position of the distal NTD and CTD domains via their flexible NTD-CCD and CCD-CTD linkers and compared their theoretical scattering profiles to the experimental data (Fig. 5D). Unlike the results derived for IN alone by this type of analysis, none of these modeled intasome configurations, either individually or as an ensemble, could capture the spatial properties indicated by scattering. This modeling suggests that an ordered, compact, and discrete configuration can account for the observed solution properties.

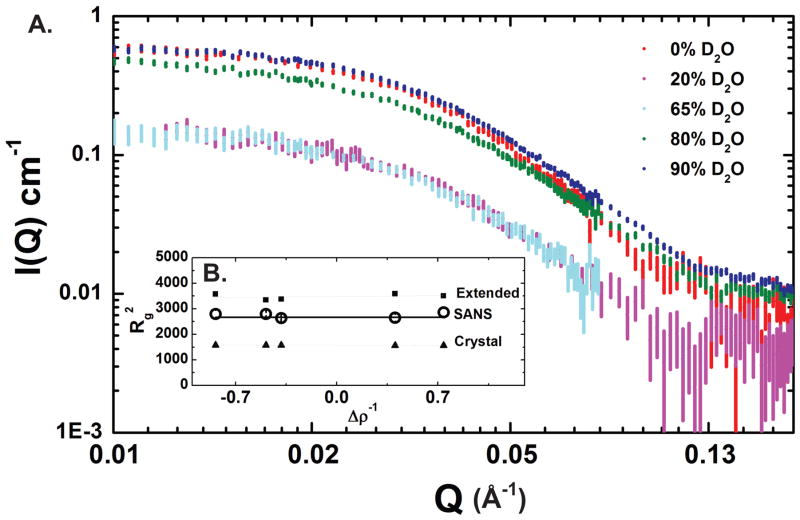

To better ascertain the disposition of the protein and DNA components of this complex, we combined SAXS with small-angle neutron scattering (SANS), which allows for the discrimination of the parts of a composite particle when the H2O:D2O ratios in the solvent are varied (the contrast variation approach)(Stuhrmann, 1974). Neutron scattering data were recorded at five different contrast points, including the 65% D2O match point predicted to coincide with the experimental match point for protein-only (Fig. 6A and Table 2). The dependence of Rg on the contrast of the individual components and their relative positions in the composite particle was determined using the Stuhrmann equation (Stuhrmann, 1974). A plot of this relationship using the five SANS contrast points and SAXS data reveals a linear trend with essentially no slope (within the error of the determination, Fig. 6B); similar results are obtained both with and without the x-ray data point. The slope and linearity of this trend do not support a placement of the DNA component at the periphery of this assembly, which would manifest itself with a hyperbolic or positively-sloped linear line in a plot of between Δρ versus Rg2, as was observed for the nucleosome (Hjelm et al., 1977). Instead, these results are most consistent with a DNA position near the center of mass, consistent with what is seen with the PFV intasome crystal structures. The protein component underlies the maximum inter-atomic distances observed in this complex, consistent with the protein arrangement inferred from available crystal structures. Consistent with this, the Rg values obtained for the 90% H2O and 80% D2O mixtures by neutron scattering, where the protein scattering contribution is the strongest, are the largest of those obtained from the contrast variation series. By both Stuhrmann plot analysis and the parallel axis theorem (Fig. 6B and Table 2), protein-only Rgs of 53.7 Å and 56.6 Å, respectively, were obtained, which also support a placement of the protein component on the periphery of the complex. Further supporting data are presented in Fig. S4.

Figure 6. SANS analysis of the PFV intasome.

A. Small-angle neutron scattering data for the PFV Intasome, shown as intensity as a function of q for five different H2O:D2O ratios (0%, 20%, 65%, 80%, and 90% D2O). Error bars represent plus and minus the combined standard uncertainty of the data collection. Shown in the inset (B) is the corresponding Stuhrmann Plot analysis. Error bars represent the statistical uncertainty of the fitting parameters and are smaller that the data points. The Rg values for the complex are related to contrast by this relationship Rg2 = Rc2 + α/ρ − β/ρ2, where Δρ is the mean contrast for the complex, Rc is the Rg of the complex at infinite contrast, and α and β are scattering density-related coefficients. The term α describes the distribution of scattering densities relative to the center of mass, and the term β relates to the separation of the mass centers of the two components. Experimental data points recorded in this study are shown as open circles; theoretical points for the model shown in Fig. 5C are shown as dark squares and theoretical points for the crystallographic structure of the intasome (with inactive monomer NTD and CTD domains excluded) are shown as dark triangles. See also Fig. S4.

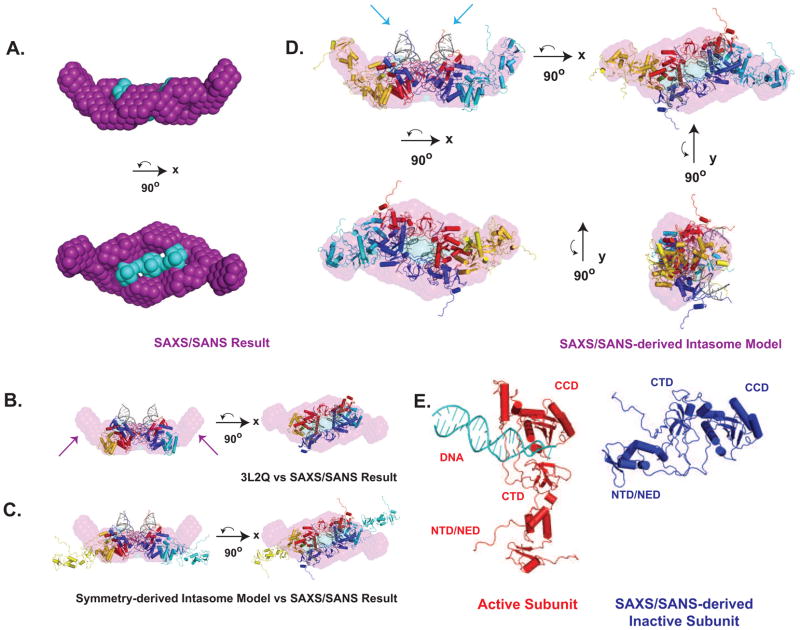

Shape reconstruction of PFV IN by simultaneous fitting of SANS and SAXS data

To establish the relative positions of the protein and DNA components of the intasome independently, shape restoration was performed using a multi-phase bead approach (Svergun, 1999) that simultaneously fit five SANS profiles and one SAXS profile. Based on the established 4:2 protein:DNA stochiometry and the domain organization in available crystal structures, we employed two-fold symmetry constraints in the calculations. The results are shown in Fig. 7A, with galleries of reconstructions and representative data fits to experimental data shown in Fig. S5. Both SANS data alone and SANS in combination with SAXS data yielded similar shapes with similar positions of the protein and DNA components (data not shown). The results of ten independent calculations yielded similar results, with χ2 values ranging from 0.82 to 3.7 for each of the six scattering profiles used (Fig. S5); these ten calculations were combined to yield the final averaged and filtered reconstruction. The resulting bead model is a prolate ellipsoid with dimensions of 180 × 75 × 53 Å, with calculated S and Rs values in good agreement with those determined experimentally (Table 3). The PFV intasome crystal structure was readily docked into this envelope (Fig. 7B), confirming the inferred quaternary arrangement from crystallographic symmetry: the protein component forms a continuous assembly which surrounds the smaller DNA component located at the center of the complex.

Figure 7. Shape Reconstruction and Modeling of the PFV intasome.

A. MONSA bead reconstruction of the PFV Intasome, two-fold symmetric with a sphere radius of 5 Å, shown in orthogonal views. Purple corresponds to the protein component and cyan to the DNA component. B. PFV Intasome crystal structure (3L2Q) modeled into MONSA solution. Purple arrows indicate protein density not accounted for by the crystallographic model. C. Initial extended symmetry-derived model of the complete intasome modeled into the MONSA solution. D. Final SAXS/SANS-derived Intasome model derived, shown in four orthogonal views. Blue arrows indicated the DNA arms which occupy a position discrepant from that indicated by SAXS/SANS. E. Comparison of crystallographic active subunit (red) with SAXS/SANS derived inactive subunit (blue). See also Figs. S5.

The most obvious discrepancy is the presence of additional protein components, present as lobes on the distal ends of the elongated envelope (arrows in Fig. 7B). When our starting model of the intact PFV intasome was placed into the envelope, the NTD and CTD domains missing from the crystal structure model were found to protrude outside of the protein component of the reconstruction, indicating that they adopt conformations that are distinct from those found in the active IN subunit (Fig. 7C). Since the NTD-CCD and CCD-CTD linkers in PFV IN allow for considerable flexibility, the rigid body motions necessary to model these domains into the vacant distal lobes were readily performed (Fig. 7D). The final model captures the gross features of the SAXS data and molecular envelope (Fig S4C, χ2=2.8) and maintains good stereochemistry, with greater than 97% of the residues in allowable regions of the Ramachandran plot.

As anticipated, the configuration of the inactive subunits in the PFV intasome is distinct from that observed with the active subunits, differing in the positioning of NTD and CTDs relative to the CCD (Fig. 7E). It is immediately apparent why these domains were not observed in the crystallographic structures: crystal lattice contacts in the crystal form used to determine the PFV-DNA complex structures would interfere with these configurations due to severe steric clashes (Fig. S1). Presumably, the crystal packing interactions are favored energetically over the inactive subunit NTD and CTD interactions, resulting in their displacement and disorder in the crystal.

The most significant difference remaining between the PFV intasome model and the shape reconstruction involves the trajectory of the viral DNA ends (denoted with cyan arrows in Fig. 7D). In PFV IN-U5 crystal structures, the viral DNA arms contribute significantly to crystal lattice formation. The ends of the DNA to be processed are lodged in the active sites of the active subunits, while the opposite ends of the DNA dock into the active sites of inactive subunits from a neighboring asymmetric unit (Fig. S1). Although scattering data clearly support the central location of the DNA component within the composite particle, the reconstruction suggests a slightly different orientation of the DNA compared to that observed in the crystal structure. The solution results suggest that the two viral DNA arms exit the protein core at a more shallow angle with respect to the long axis of the particle ellipsoid (i.e., the DNA is more parallel to the overall intasome particle), and are nested deeper within the protein component. This observation is reminiscent of atomic force microscopy measurements made on HIV SSC complexes, where a more parallel distribution of DNA arm alignments was also observed (Kotova et al., 2010). We chose not to model this aspect of the intasome, since doing so would require a relatively large number of adjustable parameters to accommodate significant changes in protein conformations. Further indication of the modest differences between our final intasome model shown in Fig. 7D and its expected behavior in solution are reflected in the calculated vs. experimental hydrodynamic parameters shown in Table 3.

Discussion

The primary goal of this study has been to determine the solution properties of PFV IN and its minimal complex with processed viral U5 DNA in order to identify aspects of the complex that are not available or that differ from the crystallographic models, including the location of distal domains not resolved in the crystal structure and the solution properties of drug-bound complexes. While small-angle scattering techniques lacks the resolution to visualize structures at high resolution, these approaches can provide rigorous tests for models of quaternary structure and can reconcile structural models of large macromolecular assemblies with their solution properties (Putnam et al., 2007; Rambo and Tainer, 2010b). The use of SANS has the added value of contrast, providing the ability to isolate the protein and DNA components of the composite particle.

A common feature of most retroviral integrases characterized to date is the formation of dimers and tetramers; in different systems, these pre-assembled oligomers have been directly linked to the native assembly of nucleoprotein intermediates and to catalysis (Bao et al., 2002; Deprez et al., 2000; Deprez et al., 2001; Li et al., 2006). In the case of the lentiviruses, the binding of the cellular co-factor LEDGF modulates IN oligomerization (Gupta et al., 2010; Hayouka et al., 2007). In contrast, we show that PFV IN is exclusively monomeric prior to binding processed viral U5 DNA, underscoring another important difference among retroviral integrases. It is currently unknown which, if any, cellular host factors might modulate this process for PFV IN, or if PFV IN plays a role in other aspects of its retroviral life cycle, as seen in HIV IN with uncoating (Briones et al., 2010), assembly (Zhang et al., 2011), and reverse transcription (Nishitsuji et al., 2009; Warren et al., 2009). The assembly of PFV IN monomers to form synaptic complexes may also be important to understanding the steps of intasome assembly in HIV IN, since recent fluorescent and biochemical measurements indicate that HIV IN monomers and dimers play a prominent role in the assembly of the intasome and in concerted strand transfer(Bera et al., 2009; Deprez et al., 2001; Pandey et al., 2011).

Our measurements confirm that the stochiometry and quaternary arrangement of the IN tetramer derived for the PFV intasome from its crystal lattice configuration reflects its gross properties in solution and that these properties are largely preserved in the presence of divalent ions and clinical inhibitors. It is clear from our analysis that two distinct species of IN subunits reside within the intasome: an active pair of subunits mediating tetramerization, DNA binding, and catalysis, and an inactive pair of subunits in a distinct configuration that is not competent for DNA binding. The discrete positions identified here for the NTD and CTD of the inactive subunits raise questions about the possible functional role for this inactive configuration and the apparent redundancy in composition of the intasome. One possibility is that these distal domains ensure the fidelity of synapsis and strand transfer by precluding unwanted DNA interactions that would otherwise disfavor concerted strand transfer.

Another possibility is that the inactive NTDs and CTDs provide stabilizing interactions with the viral DNA or with other proteins within the preintegration complex, interactions that cannot be addressed with the minimal substrates utilized in this study or in the crystallographic models. Indeed, assembly of HIV-1 intasomes requires several hundred base pairs of DNA in addition to the terminal viral DNA sequences (Li et al., 2012). The distal domains might also stabilize the intasome during target capture by interacting with chromatin and/or target DNA. Based on the PFV intasome model described in this study, it seems unlikely that these interactions would be possible without significant conformational changes on the part of the inactive subunits, since the positions of the distal domains are remote from the target DNA binding site indicated by available PFV STC structures (Maertens et al., 2010).

Lastly, these outer domains may function outside of the scope of catalysis to recruit host factors to the pre-integration complex (PIC) and ultimately the site of integration. For example, the cellular double-strand break repair proteins Rad51 (Cosnefroy et al., 2012; Desfarges et al., 2006), Ku (Zheng et al., 2011), and Rad18 (Mulder et al., 2002) have all been reported to interact with IN and may play a role in repairing the gaps in retroviral DNA integration intermediates to complete the creation of provirus (Yoder and Bushman, 2000).

Because of the homology of PFV IN to HIV IN and the conserved biochemical aspects of concerted integration among all of the retroviral integrases, it is expected that the PFV intasome should largely mirror the assembly made by HIV IN with viral DNA. Indeed, an HIV intasome homology model based on the PFV intasome structures has recently been reported (Krishnan et al., 2010). In a similar fashion, a HIV intasome model using the SAXS/SANS-derived PFV intasome presented here as the template can be rendered (Fig. S5). This model recapitulates the overall features of that described by Krishnan et al., and builds upon their findings by providing insight into the possible nature of the distal domains of the inactive monomers in this integration assembly. In contrast, cryo-EM reconstructions of LEDGF-bound IN tetramers with and without DNA (Michel et al., 2009) suggest a quaternary arrangement that is largely different in the configuration of the inactive monomers. Comparative structural and biophysical studies of HIV IN nucleoprotein complexes may yield further insights into these issues.

Experimental Procedures

Expression and Purification of PFV IN and Preparation of Intasomes

The purification of full-length PFV IN (IN 1-392) was carried out as previously described (Valkov et al., 2009). The purified protein was concentrated to 5–12 mg/mL in 50 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.4, 320 mM NaCl, 10 mM DTT, and 20% (v/v) glycerol before flash-freezing in liquid N2 and storage at −80°C. Protein concentration was determined by Bradford assay (Bio-Rad Laboratories).

Preprocessed U5 LTR Oligonucleotides previously described (Hare et al., 2010) were synthesized on a Mermade 4 (Bioautomation) oligonucleotide synthesizer and reverse-phase purified; purity was assessed using PAGE analysis. Complexes were prepared as described previously (Hare et al., 2010).

Prior to biophysical analyses including small-angle scattering, protein alone or intasome complexes were purified on a Superdex 200 column (GE Healthcare), concentrated with a 10kD Amicon Ultra concentrator (Millipore), and dialyzed using a 6–8kD cutoff D-tube dialyzer (Novagen). All measurements in this study were performed in 20 mM HEPES, ph 7.4, 320 mM NaCl, 10 μM ZnOAc2, and 1–10 mM dithiothreitol (DTT).

Size-Exclusion Chromatography & Multi-angle Light Scattering (SEC-MALS)

Absolute molecular weights of PFV IN were determined using MALS (Wyatt Corporation) coupled with a Superdex 200 10/300 GL column (GE Healthcare). This analysis and Stokes radius (Rs) determination were performed as previously described (Gupta et al., 2010). For determination of absolute molecular weight of PFV intasome, a mass-averaged dn/dc of 0.182 ml/g was used to account for the DNA component.

Analytical Ultracentrifugation

Sedimentation equilibrium (SE) and sedimentation velocity (SV) experiments were performed at 4°C and 25°C, respectively, with an XL-A analytical ultracentrifuge (Beckman Coulter) and a TiAn60 rotor with charcoal-filled epon centerpieces and quartz windows. For SE analysis, radial absorption scan data at 295 nm for three protein concentrations were measured at 16 hr and 18 hr for each of three different rotor speeds (28,000, 30,000, and 32,000 rpm). Data were analyzed using the programs SEDFIT (Schuck, 2000) and SEDPHAT (Vistica et al., 2004). An estimated error for the determined mass was determined from a 1,000-iteration Monte Carlo simulation, as implemented in SEDPHAT. For SV analysis complete absorbance profiles at 280 nm were collected every 30 seconds at 45,000 rpm, followed by data analysis using the program SEDFIT. For all analyses, a standard value of 0.73 cm3/g was used for partial specific volume (vbar) of PFV IN and 0.59 cm3/g for DNA. SEDNTERP (Laue et al., 1992) was used to calculate values for buffer viscosity (η, 0.01 poise) and the density of the buffer (ρ, 1.0079 g/cm3).

Small-Angle Scattering and Molecular Modeling

X-ray scattering data were measured at three different sources: beam line G1 at Cornell University High Energy Synchrotron Source (CHESS, Ithaca, NY, USA), beam line 18-ID at Argonne National Laboratory (APS BioCAT, Argonne, IL, USA), and beam line 12.3.1 at the Advanced Light Source (ALS SIBYLS, Berkeley, CA, USA). Neutron scattering data were collected on the NG3 30 m SANS instrument at the National Institute for Standards and Technology (NIST, Gaithersburg, MD, USA.). Specific details of the experimental set-up and procedures specific to each location, and to the molecular modeling methods employed, are provided in the supplemental methods.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Gregory Hura, Jane Tanamachi, Kevin Dyer, and Michael Hammel (ALS), Liang Guo (APS), and Richard Gillilan (CHESS) for their technical support with data collection. The ALS SIBYLS beamline is supported by the DOE under Contract No. DE-AC02-05CH11231. Use of the APS was supported by DOE Contract No. DE-AC02-06CH11357. BioCAT is a NIH-supported Research Center RR-08630. CHESS is supported by NSF award DMR-0936384, and the MacCHESS resource is supported by NIH/NCRR award RR-01646. The neutron scattering studies utilized facilities supported, in part, by the NSF under agreement no. DMR-0454672. G.V. is an Investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Arts EJ, Hazuda DJ. HIV-1 antiretroviral drug therapy. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Medicine. 2012:1–23. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a007161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bao KK, Wang H, Miller JK, Erie DA, Skalka AM, Wong I. Functional oligomeric state of avian sarcoma virus integrase. J Biol Chem. 2002;278:1323–1327. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C200550200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bera S, Pandey KK, Vora AC, Grandgenett DP. Molecular Interactions between HIV-1 integrase and the two viral DNA ends within the synaptic complex that mediates concerted integration. J Mol Biol. 2009;389:183–198. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernado P, Svergun DI. Structural analysis of intrinsically disordered proteins by small-angle X-ray scattering. Mol Biosyst. 2012;8(1):151–67. doi: 10.1039/c1mb05275f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briones MS, Dobard CW, Chow SA. The Role of Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1 Integrase in the Uncoating of the Viral Core. J Virol. 2010;84(10):5181–5190. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02382-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cosnefroy O, Tocco A, Lesbats P, Thierry S, Calmels C, Wiktorowicz T, Reigadas S, Kwon Y, De Cian A, Desfarges S, et al. Stimulation of the human RAD51 nucleofilament restricts HIV-1 integration in vitro and in infected cells. J Virol. 2012;86:513–526. doi: 10.1128/JVI.05425-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis JE, Raghunandan S, Nanda H, Krueger S. SASSIE: A program to study intrinsically disordered biological molecules and macromolecular ensembles using experimental scattering restraints. Computer Physics Communications. 2012;183(2):382–389. [Google Scholar]

- Delelis O, Carayon K, Guiot E, Leh H, Tauc P, Brochon J, Mouscadet J, Deprez E. Insight into the integrase-DNA recognition mechanism. A specific DNA-binding mode revealed by an enzymatically labeled integrase. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:27838–27849. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M803257200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deprez E, Tauc P, Leh H, Mouscadet JF, Auclair C, Brochon JC. Oligomeric states of the HIV-1 integrase as measured by time-resolved fluorescence anisotropy. Biochemistry. 2000;39:9275–9284. doi: 10.1021/bi000397j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deprez E, Tauc P, Leh H, Mouscadet JF, Auclair C, Hawkins ME, Brochon JC. DNA binding induces dissociation of the multimeric form of HIV-1 integrase: a time-resolved fluorescence anisotropy study. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:10090–10095. doi: 10.1073/pnas.181024498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desfarges S, San Filippo J, Fournier M, Calmels C, Caumont-Sarcos A, Litvak S, Sung P, Parissi V. Chromosomal integration of LTR-flanked DNA in yeast expressing HIV-1 integrase: down regulation by RAD51. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:6215–6224. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espeseth AS, Felock P, Wolfe A, Witmer M, Grobler J, Anthony N, Egbertson M, Melamed JY, Young S, Hamill T, et al. HIV-1 integrase inhibitors that compete with the target DNA substrate define a unique strand transfer conformation for integrase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:11244–11249. doi: 10.1073/pnas.200139397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faure A, Calmels C, Desjobert C, Castroviejo M, Caumont-Sarcos A, Tarrago-Litvak L, Litvak S, Parissi V. HIV-1 integrase crosslinked oligomers are active in vitro. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:977–986. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta K, Diamond T, Hwang Y, Bushman F, Van Duyne GD. Structural properties of HIV integrase-Lens epithelium-derived growth factor oligomers. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:20303–20315. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.114413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hare S, Gupta SS, Valkov E, Engelman A, Cherepanov P. Retroviral intasome assembly and inhibition of DNA strand transfer. Nature. 2010;464:232–236. doi: 10.1038/nature08784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Havlir DV. HIV integrase inhibitors--out of the pipeline and into the clinic. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:416–418. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe0804289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayouka Z, Rosenbluh J, Levin A, Loya S, Lebendiker M, Veprintsev D, Kotler M, Hizi A, Loyter A, Friedler A. Inhibiting HIV-1 integrase by shifting its oligomerization equilibrium. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:8316–8321. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700781104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hjelm RP, Kneale GG, Sauau P, Baldwin JP, Bradbury EM, Ibel K. Small angle neutron scattering studies of chromatin subunits in solution. Cell. 1977;10:139–151. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(77)90148-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaskolski M, Alexandratos JN, Bujacz G, Wlodawer A. Piecing together the structure of retroviral integrase, an important target in AIDS therapy. FEBS J. 2009;276:2926–2946. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2009.07009.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins TM, Engelman A, Ghirlando R, Craigie R. A soluble active mutant of HIV-1 integrase: involvement of both the core and carboxyl-terminal domains in multimerization. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:7712–7718. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.13.7712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotova S, Li M, Dimitriadis EK, Craigie R. Nucleoprotein intermediates in HIV-1 DNA integration visualized by atomic force microscopy. J Mol Biol. 2010;399:491–500. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2010.04.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnan L, Li X, Naraharisetty HL, Hare S, Cherepanov P, Engelman A. Structure-based modeling of the functional HIV-1 intasome and its inhibition. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:15910–15915. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1002346107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laue TM, Shah B, Ridgeway TM, Pelletier SL, Harding SE, Rowe AJ, Horton JC. In: In Analytical Ultracentrifugation in Biochemistry and Polymer Science. Harding SE, Rowe AJ, Horton JC, editors. Cambridge, U.K: Royal Society of Chemistry; 1992. pp. 90–125. [Google Scholar]

- Li M, Ivanov V, Mizuuchi M, Mizuuchi K, Craigie R. DNA requirements for assembly and stability of HIV-1 intasomes. Protein Sci. 2012;21:249–257. doi: 10.1002/pro.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li M, Mizuuchi M, Burke TRJ, Craigie R. Retroviral DNA integration: reaction pathway and critical intermediates. EMBO J. 2006;25:1295–1304. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maertens GN, Hare S, Cherepanov P. The mechanism of retroviral integration from x-ray structures of its key intermediates. Nature. 2010;468:326–329. doi: 10.1038/nature09517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michel F, Crucifix C, Granger F, Eiler S, Mouscadet JF, Korolev S, Agapkina J, Ziganshin R, Gottikh M, Nazabal A, et al. Structural basis for HIV-1 DNA integration in the human genome, role of the LEDGF/p75 cofactor. EMBO J. 2009;28:980–991. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulder LC, Chakrabarti LA, Muesing MA. Interaction of HIV-1 integrase with DNA repair protein hRad18. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:27489–27493. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M203061200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishitsuji H, Hayashi T, Takahashi T, Miyano M, Kannagi M, Masuda T. Augmentation of reverse transcription by integrase through an interaction with host factor, SIP1/Gemin2 is critical for HIV-1 infection. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e7825. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandey KK, Bera S, Grandgenett DP. The HIV-1 integrase monomer induces a specific interaction with LTR DNA for concerted integration. Biochemistry. 2011;50(45):9788–9796. doi: 10.1021/bi201247f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelikan M, Hura GL, Hammel M. Structure and flexibility within proteins as identified through small-angle X-ray scattering. Gen Physiol Biophys. 2009;28:174–189. doi: 10.4149/gpb_2009_02_174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Putnam CD, Hammel M, Hura GL, Tainer JA. X-ray solution scattering (SAXS) combined with crystallography and computation: defining macromolecular structures, conformations, and assemblies in solution. Q Rev Biophys. 2007;40(3):191–285. doi: 10.1017/S0033583507004635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rambo RP, Tainer JA. Improving small-angle x-ray scattering data for structural analyses of the RNA world. RNA. 2010;16(3):638–46. doi: 10.1261/rna.1946310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rambo RP, Tainer JA. Bridging the solution divide: comprehensive structural analyses of dynamic RNA, DNA, and protein assemblies by small-angle x-ray scattering. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2010;20(1):128–37. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2009.12.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuck P. Size-distribution analysis of macromolecules by sedimentation velocity ultracentrifugation and Lamm equation modeling. Biophys J. 2000;78:1606–1619. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(00)76713-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semenyuk AV, Svergun DI. GNOM - A program package for small-angle scattering data-processing. J App Cryst. 1991;24:537–540. [Google Scholar]

- Siegel L, Monty K. Determination of molecular weights and frictional ratios of proteins in impure systems by use of gel filtration and density gradient centrifugation. Application to crude preparations of sulfite and hydroxylamine reductases. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1966;112(2):346–362. doi: 10.1016/0926-6585(66)90333-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuhrmann HB. Neutron small-angle scattering of biological macromolecules in solution. J Appl Cryst. 1974;7:173. [Google Scholar]

- Svergun DI. Restoring low resolution structure of biological macromolecules from solution scattering using simulated annealing. Biophys J. 1999;77:2896–2896. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(99)77443-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valkov E, Gupta SS, Hare S, Helander A, Roversi P, McClure M, Cherepanov P. Functional and structural characterization of the integrase from the prototype foamy virus. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:243–255. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varmus HE, Brown PO, Berg DE, Howe M. In: Mobile DNA. Berg DE, Howe MM, editors. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1989. pp. 53–108. [Google Scholar]

- Vistica J, Dam J, Balbo A, Yikilmaz E, Mariuzza RA, Rouault TA, Schuck P. Sedimentation equilibrium analysis of protein interactions with global implicit mass conservation constraints and systematic noise decomposition. Anal Biochem. 2004;326:234–256. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2003.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogt VM. In: Retroviruses. Coffin JM, Hughes SH, Varmus HE, editors. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1997. pp. 263–334. [Google Scholar]

- Warren K, Warrilow D, Meredith L, Harrich D. Reverse transcriptase and cellular factors: regulators of HIV-1 reverse transcription. Viruses. 2009;1:873–894. doi: 10.3390/v1030873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitten AE, Cai SZ, Trewhella J. MULCh: modules for the analysis of small-angle neutron contrast variation data from biomolecular assemblies. J Appl Cryst. 2008;41:222–226. [Google Scholar]

- Yoder KE, Bushman FD. Repair of gaps in retroviral DNA integration intermediates. J Virol. 2000;74:11191–11200. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.23.11191-11200.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang F, Zang T, Wilson SJ, Johnson MC, Bieniasz PD. Clathrin facilitates the morphogenesis of retrovirus particles. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7:e1002119. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng Y, Ao Z, Wang B, Jayappa KD, Yao X. Host protein Ku70 binds and protects HIV-1 integrase from proteasomal degradation and is required for HIV replication. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:17722–17735. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.184739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.