Abstract

The Arabidopsis thaliana central cell, the companion cell of the egg, undergoes DNA demethylation before fertilization, but the targeting preferences, mechanism, and biological significance of this process remain unclear. Here, we show that active DNA demethylation mediated by the DEMETER DNA glycosylase accounts for all of the demethylation in the central cell and preferentially targets small, AT-rich, and nucleosome-depleted euchromatic transposable elements. The vegetative cell, the companion cell of sperm, also undergoes DEMETER-dependent demethylation of similar sequences, and lack of DEMETER in vegetative cells causes reduced small RNA–directed DNA methylation of transposons in sperm. Our results demonstrate that demethylation in companion cells reinforces transposon methylation in plant gametes and likely contributes to stable silencing of transposable elements across generations.

Cytosine methylation regulates gene expression and represses transposable elements (TEs) in plants and vertebrates (1). DNA methylation in plants is catalyzed by three families of DNA methyltransferases that can be roughly grouped by the preferred sequence context: CG, CHG, and CHH (H = A, C, or T). The small RNA (sRNA) pathway targets de novo methylation in all sequence contexts and is required for the maintenance of CHH methylation.

Flowering plant sexual reproduction involves two fertilization events (2). The pollen vegetative cell forms a tube that carries two sperm cells to the ovule, where one fuses with the diploid central cell to form the triploid placenta-like endosperm, and the other fertilizes the haploid egg to produce the embryo. Endosperm DNA of Arabidopsis thaliana is modestly, but globally, less methylated than embryo DNA in all contexts (3). The DEMETER (DME) DNA glycosylase that excises 5-methylcytosine is highly expressed in the central cell before fertilization and is at least partially required for the demethylation ob served in endosperm (2, 3), which has been inferred to occur on the maternal chromosomes inherited from the central cell. Passive mechanisms, such as down-regulation of the MET1 DNA methyltransferase, have also been proposed to contribute to demethylation of the maternal endosperm genome (2). The global differences between embryo and endosperm are consistent with passive demethylation and suggest that the process may have little sequence specificity (3, 4). However, DNA methylation of the maternal and paternal endosperm genomes has not been compared except for a few loci, and therefore, it is difficult to make general inferences about the mechanism and specificity of central cell demethylation. Why the central cell should undergo extensive DNA demethylation is also unclear.

To understand the extent, mechanism, and biological significance of active demethylation in the central cell, we used reciprocal crosses between the Col and Ler accessions of Arabidopsis that differ by >400,000 single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) (4) to identify DNA methylation that resides on either the maternal or paternal endosperm genome (5) by shotgun bisulfite sequencing (table S1). The wild-type maternal genome is substantially less methylated than the paternal genome in the CG context (Fig. 1A and figs. S1 and S2), with slight global hypomethylation accompanied by strong local demethylation (Fig. 1B and figs. S3 and S4). The local demethylation is nearly fully reversed in dme mutant endosperm (Fig. 1, A and B, and figs. S2, S4, and S5), which indicates that DME is either the only or by far the major enzyme required for excision of 5-methylcytosine in the central cell and demonstrating that active DNA demethylation of at least 9816 specific sequences spanning 4,443,250 bp (table S2) accounts for the methylation differences between the maternal and paternal endosperm genomes. Global CG methylation of both maternal and paternal genomes is slightly elevated by lack of DME compared with wild type (Fig. 1A and fig. S5), consistent with overexpression of genes that mediate CG methylation in dme endosperm (4).

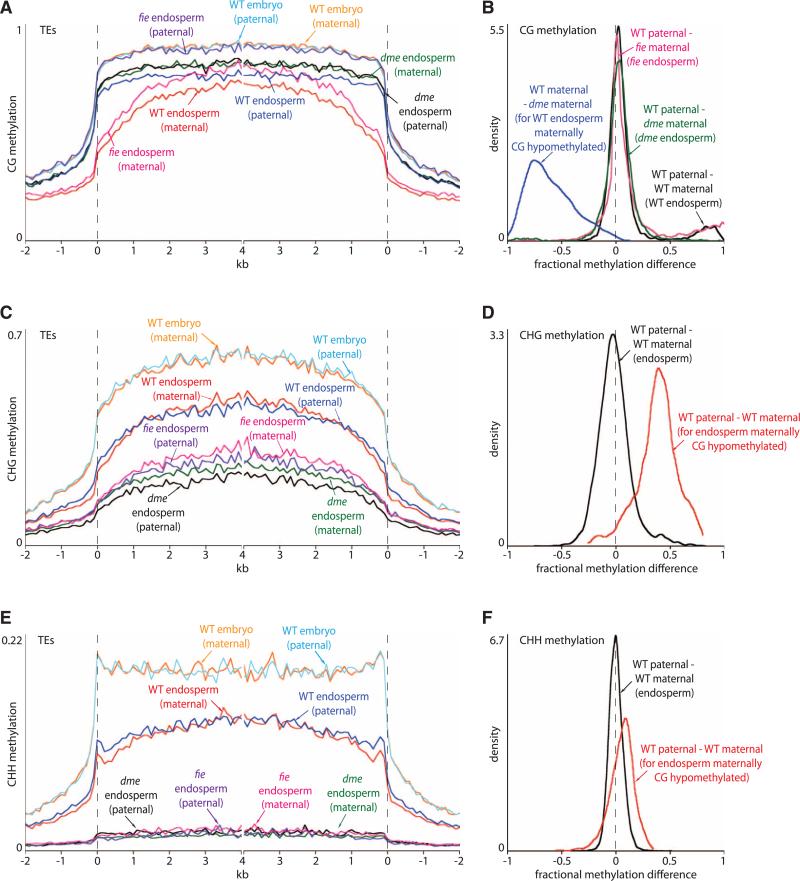

Fig. 1.

Local DME-dependent demethylation of maternal endosperm chromosomes. (A, C, and E) Transposons were aligned at the 5′ and 3′ ends (dashed lines) and average methylation levels for each 100-bp interval are plotted. (B, D, and F) Kernel density plots trace the frequency distribution of endosperm methylation differences for all 50-bp windows with an informative SNP. A shift of the peak with respect to zero represents a global difference; shoulders represent local differences.

Global CHG methylation of the wild-type endosperm maternal genome is similar to that of the paternal genome (Fig. 1, C and D), but loci that are maternally demethylated in the CG context show strong maternal CHG demethylation (Fig. 1D), consistent with the reported in vitro activity of DME on methylation in all sequence contexts (6). A similar but weaker correspondence exists for CHH methylation (Fig. 1, E and F), presumably because sRNA-directed DNA methylation (RdDM) patterns are more variable, and may be partially restored after fertilization. We did not observe major methylation differences between parental genomes in embryo (Fig. 1, A, C, and E; and figs. S1, S2, S4, and S6).

As we showed previously, dme endosperm has greatly reduced CHG methylation and almost no CHH methylation (3), and our present data show that this applies similarly to both parental genomes (Fig. 1, C and E, and fig. S2). As this is the opposite of the outcome expected from a mutation in a demethylating enzyme, we hypothesized an indirect mechanism. DME activity is required for functionality of the Poly-comb repressive complex 2 (PRC2) in endosperm, prompting us to examine methylation in endo-sperm lacking maternal activity of the core PRC2 protein FIE (2). Lack of FIE had an effect similar to that of lack of DME on non-CG methylation (Fig. 1, C and E, and table S1), which indicates that PRC2 promotes non-CG DNA methylation in endosperm. In contrast, local maternal CG demethylation was mostly unaffected by lack of FIE (Fig. 1B and figs. S4 and S5), as would be expected with direct activity of DME. Global CG methylation levels were increased even more than in dme endosperm (Fig. 1A and fig. S5), consistent with strong overexpression of genes that mediate CG methylation in fie endosperm (4).

DME-mediated DNA demethylation in the central cell is required to establish monoallelic (imprinted) expression of a number of genes in the endosperm (2, 4). We examined the location of loci that are significantly less methylated in wild-type endosperm than in dme endosperm (table S2) in relation to imprinted endosperm genes (fig. S4). Maternally and paternally expressed genes are preferentially associated with such differentially methylated regions (DMRs), particularly just upstream of the gene (fig. S7). Maternally expressed genes also exhibit DMRs that span the transcriptional start site (fig. S7), consistent with the strong correlation between methylation of this region and gene silencing (1). Paternally expressed genes are enriched in DMRs within the gene body (fig. S7), which suggests that gene body demethylation can disrupt gene expression, for example, by revealing repressor binding sites, as has been proposed for the DMR downstream of the PHERES1 gene (fig. S4) (2).

Several TEs were reported to be less methylated in the pollen vegetative cell of Arabidopsis compared with sperm (7), and we recently showed that DME is required for demethylation of two genes in the vegetative cell that are demethylated by DME in the central cell (8). These data suggest that DME-mediated DNA demethylation may proceed similarly in the central and vegetative cells. To examine this issue, we compared DNA methylation patterns in sperm and vegetative cell nuclei that were purified by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (8, 9). Most CG sites are heavily and similarly methylated in both cell types, but a subset is specifically demethylated in the vegetative cell (Fig. 2, A and B, and figs. S3, S4, and S8), corresponding to at least 9932 loci spanning 4,068,000 bp (table S2). The demethylated vegetative cell CG sites overlap 45.5% of those demethylated in the maternal endosperm genome and, by extension, in the central cell (Fig. 2B, fig. S4, and table S2).

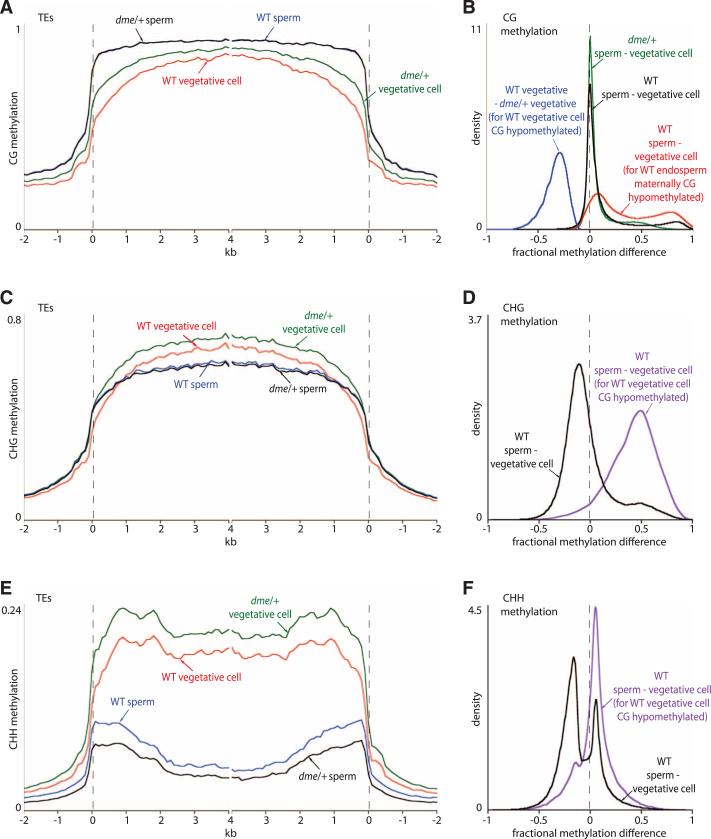

Fig. 2.

Local DME-dependent demethylation in the pollen vegetative cell. (A, C, and E) Average methylation in transposons was plotted as in Fig. 1. (B, D, and F) Kernel density plots, as in Fig. 1, of pollen methylation differences in 50-bp windows.

We examined methylation in pollen from heterozygous dme/+ plants (strong dme alleles cannot be made homozygous), in which half of the pollen lacks dme (8). CG sites that are demethylated in wild-type vegetative cells showed much greater methylation in vegetative cell nuclei isolated from dme/+ pollen (Fig. 2, A and B, and fig. S4), which indicates that DME is required for demethylation in the vegetative cell. CHG methylation is generally higher in the vegetative cell than in the sperm cell (Fig. 2, C and D), but loci demethylated at CG sites in the vegetative cell are also demethylated at CHG sites (Fig. 2D), as they are in endosperm (Fig. 1D). CHH methylation is very high in the vegetative cell and low in sperm (Fig. 2E), consistent with the strong RdDM activity reported in the vegetative cell (9). Nonetheless, vegetative cell CG-demethylated loci tend to show lower CHH methylation in vegetative cells than in sperm (Fig. 2F). Overall, our data strongly support the hypothesis that DNA demethylation in the male and female companion cells proceeds by an active, DME-dependent mechanism.

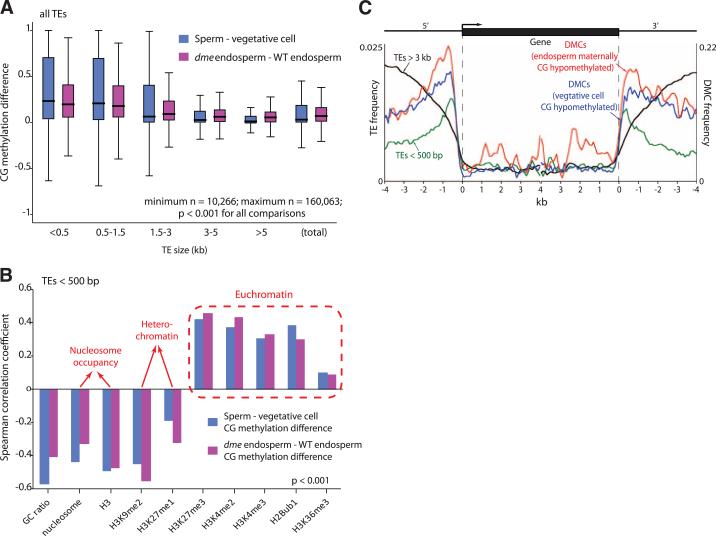

Loci demethylated in companion cells tend to be within smaller AT-rich TEs that are enriched for euchromatin-associated histone modifications (10) and depleted of nucleosomes with heterochromatin-associated modifications (Fig. 3, A and B, and figs. S9 and S10), which suggests that chromatin structure plays an important role in regulating active DNA demethylation (11), consistent with the decondensation of heterochromatin observed in central and vegetative cells (9, 12). TEs longer than 3 kb are rarely demethylated (Fig. 3A and fig. S3), except at the edges (fig. S9), consistent with our published observations in rice (13). The preference for smaller TE demethylation holds for TEs of various types (fig. S10). Demethylation of small TEs accounts for the shapes of the wild-type maternal endo-sperm methylation traces (Fig. 1, A, C, and E) and the wild-type vegetative cell methylation traces (Fig. 2, A and C), which are closer to the paternal and sperm traces, respectively, in the middle (long TEs) than at the points of alignment (mostly small TEs). Small Arabidopsis TEs, like their rice counterparts (13), tend to occur near genes (Fig. 3C), explaining the observation that DME and related glycosylases preferentially demethylate gene-adjacent sequences (Fig. 3C) (2, 14, 15). This phenomenon explains why CHG and CHH methylation is lower in wild-type vegetative cells compared with sperm near genes (fig. S8), even though overall non-CG methylation is higher in vegetative cells than in sperm (Fig. 2, C to F).

Fig. 3.

DME demethylates small, AT-rich euchromatic TEs. (A) Box plots showing absolute fractional demethylation of 50-bp windows within transposons. Each box encloses the middle 50% of the distribution, with the horizontal line marking the median, and vertical lines marking the minimum and maximum values that fall within 1.5 times the height of the box. Differences between size categories are significant (P < 0.001, Kolmogorov-Smirnov test). (B) Significant (P < 0.001, Kolmogorov-Smirnov test) Spearman correlation coefficients between extent of demethylation and chromatin features. (C) Distribution of TEs and significantly differentially methylated cyto-sines (DMCs) (CG context; P < 0.0001, Fisher's exact test) with respect to genes.

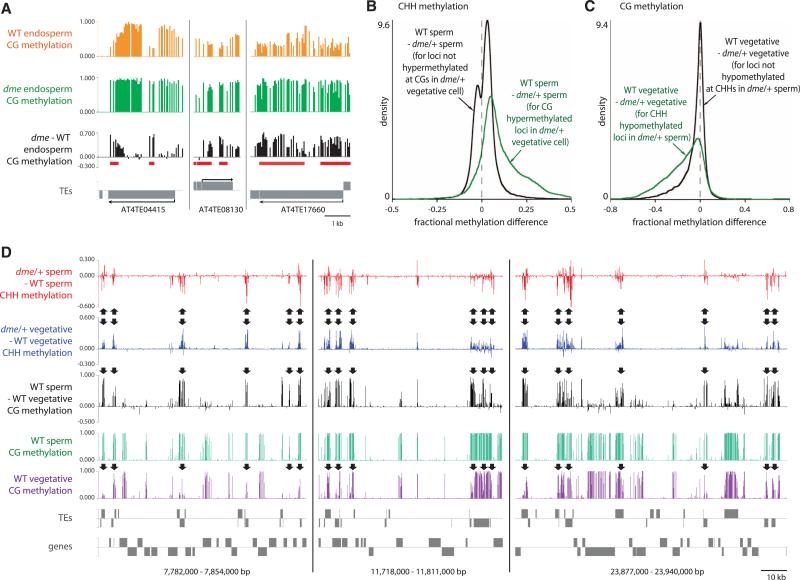

The abundance of DME targets in gene-poor heterochromatin (fig. S11) and the overlap among DME targets in the central and vegetative cells (table S2), despite their different functions and developmental fates, suggest that establishment of genomic imprinting is not the basal function of DME. DNA demethylation and activation of TEs in the vegetative cell was proposed to generate sRNAs that would reinforce silencing of complementary TEs in sperm (7). If such TEs are demethylated in the central cell, their maternal copies should remain active in endosperm. Indeed, we identified 11 TEs demethylated by DMA that are specifically maternally expressed in wild-type, but not dme, endosperm (Fig. 4A and table S4) (4). We also tested whether sRNAs can travel from the central cell to the egg by expressing a microRNA in the central cell that targets cleavage of green fluorescent protein (GFP) RNA expressed from a transgene in the egg, analogous to an experiment performed earlier in pollen (7). The central cell-expressed microRNA substantially reduced GFP fluorescence in the egg (fig. S12 and table S5), which suggests that central cell sRNAs can travel into and function in the egg.

Fig. 4.

Demethylation activates TEs in companion cells and reinforces methylation in sperm. (A) DME-dependent demethylation of TEs that are maternally expressed in wild-type, but not dme, endosperm (table S4). DMRs (table S2) are underlined. (B) Kernel density plots of the CHH methylation differences between sperm cells from wild-type and dme/+ plants. (C) Kernel density plots of the CG methylation differences between vegetative cells from wild-type and dme/+ plants. (D) Snapshots of CG and CHH methylation in pollen on chromosome 1. Arrows point out loci with decreased CHH methylation in sperm and increased CG methylation in vegetative cells from dme/+ pollen.

If silencing induced by companion cell sRNAs occurs at the transcriptional level, lack of DME in the companion cell would be expected to reduce RdDM of DME target sequences in gametes. Indeed, overall CHH methylation of TEs is decreased in dme/+ sperm compared with wild-type sperm (Fig. 2E), and CG sites demethylated by DME in vegetative cells show preferential CHH hypomethylation in dme/+ sperm (Fig. 4, B and D). Conversely, loci that exhibit decreased CHH methylation in dme/+ sperm show increased CG methylation in dme/+ vegetative cells (Fig. 4, C and D). Thus, DME activity in the vegetative cell is required for full methylation of a subset of sperm TEs, which indicates that demethylation in companion cells generates a mobile signal—probably sRNA—that immunizes the gametes against TE activation. This conclusion is supported by the specific CHH hypermethylation of small, endosperm-demethylated TEs observed in the rice embryo (13).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank S. Harmer for assistance with the analysis of histone modifications, the BioOptics team at the Vienna Biocenter Campus for sorting sperm and vegetative cell nuclei, K. Slotkin for the LAT52p-amiRNA=GFP plasmid, and G. Drews for the DD45p-GFP transgenic line. This work was partially funded by an NIH grant (GM69415) to R.L.F., NSF grants (MCB-0918821 and IOS-1025890) to R.L.F. and D.Z., a Young Investigator Grant from the Arnold and Mabel Beckman Foundation to D.Z., an Austrian Science Fund (FWF) grant P21389-B03 to H.T., a Ruth L. Kirschstein NIH Predoctoral Fellowship (GM093633) to C.A.I., a Fulbright Scholarship to J.A.R., a fellowship from the Jane Coffin Childs Memorial Fund to A.Z., and a Robert and Colleen Haas Scholarship to D.R. Sequencing data are deposited in GEO (GSE38935).

Footnotes

Supplementary Materials

www.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/337/6100/1360/DC1 Materials and Methods Supplementary Text Figs. S1 to S12 Tables S1 to S5 References (16–28)

References

- 1.Law JA, Jacobsen SE. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2010;11:204. doi: 10.1038/nrg2719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bauer MJ, Fischer RL. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2011;14:162. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2011.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hsieh T-F, et al. Science. 2009;324:1451. doi: 10.1126/science.1172417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hsieh T-F, et al. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2011;108:1755. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Materials and methods are available as supplementary materials on Science Online.

- 6.Gehring M, et al. Cell. 2006;124:495. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.12.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Slotkin RK, et al. Cell. 2009;136:461. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.12.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schoft VK, et al. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2011;108:8042. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schoft VK, et al. EMBO Rep. 2009;10:1015. doi: 10.1038/embor.2009.152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Roudier F, et al. EMBO J. 2011;30:1928. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Qian W, et al. Science. 2012;336:1445. doi: 10.1126/science.1219416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pillot M, et al. Plant Cell. 2010;22:307. doi: 10.1105/tpc.109.071647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zemach A, et al. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2010;107:18729. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1009695107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lister R, et al. Cell. 2008;133:523. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.03.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Penterman J, et al. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2007;104:6752. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701861104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.