Abstract

Despite the widespread role of transforming growth factor-β3 (TGFβ3) in wound healing and tissue regeneration, its long-term controlled release has not been demonstrated. Here, we report microencapsulation of TGFβ3 in poly-d-l-lactic-co-glycolic acid (PLGA) microspheres and determine its bioactivity. The release profiles of PLGA-encapsulated TGFβ3 with 50:50 and 75:25 PLA:PGA ratios differed throughout the experimental period. To compare sterilization modalities of microspheres, bFGF was encapsulated in 50:50 PLGA microspheres and subjected to ethylene oxide (EO) gas, radiofrequency glow discharge (RFGD), or ultraviolet (UV) light. The release of bFGF was significantly attenuated by UV light, but not significantly altered by either EO or RFGD. To verify its bioactivity, TGFβ3 (1.35 ng/mL) was control-released to the culture of human mesenchymal stem cells (hMSC) under induced osteogenic differentiation. Alkaline phosphatase staining intensity was markedly reduced 1 week after exposing hMSC-derived osteogenic cells to TGFβ3. This was confirmed by lower alkaline phosphatase activity (2.25 ± 0.57 mU/mL/ng DNA) than controls (TGFβ3-free) at 5.8 ± 0.9 mU/mL/ng DNA (p < 0.05). Control-released TGFβ3 bioactivity was further confirmed by lack of significant differences in alkaline phosphatase upon direct addition of 1.35 ng/mL TGFβ3 to cell culture (p > 0.05). These findings provide baseline data for potential uses of microencapsulated TGFβ3 in wound healing and tissue-engineering applications.

INTRODUCTION

Transforming growth factor-β3 (TGFβ3) is a member of a superfamily of cell mediators and plays fundamental roles in the regulation of cell proliferation and differentiation. In wound healing, TGFβ3 has been demonstrated to attenuate type I collagen synthesis and reduce scar tissue formation.1–3 TGFβ3 has been shown to regulate the ossification of fibrous tissue in cranial sutures in craniosynostosis, a congenital disorder affecting 1 in approximately 2500 live human births and manifesting as skull deformities, blindness, mental retardation, and death.4–6 During development, TGFβ3 regulates the adhesion of epithelial cells and subsequent fusion of the two palatal shelves, the failure of which leads to cleft palate.7,8 During umbilical cord development, TGFβ3 downregulation results in the commonly observed abnormal structure and mechanical properties of pre-eclampsia umbilical cords, a leading cause of maternal and infant death during umbilical cord formation.9 TGFβ3 mediates the proliferation of corneal stromal fibroblasts by activating other endogenous factors, including FGF-2.10 The mechanism of fibrosis after glaucoma surgery is mediated by TGFβ3 and its effects on sub-conjunctival fibroblasts.11

The fundamental roles of TGFβ3 in the development of a wide range of cells and tissues have prompted its recent adoption in tissue repair approaches. Topical application of TGFβ3 in gels ameliorated wound healing in patients at a dose of 2.5 μg/cm2 compared to placebo gels.12 Collagen gels soaked with TGFβ3 delivered to the ossifying cranial suture have been shown to delay premature fusion.13,14 Bioactive TGFβ3 released from PLA microgrooved surfaces inhibits the proliferation of lung epithelial cells for up to 24 hours.15 Previous attempts at controlled release of cytokines include lipid nanoparticles,16 chitosan or gelatin-based particles,17,18 collagen,19,20 ceramics,21,22 and porous glass.23 Although the short-term bioactivity of TGFβ3 has been investigated, exploration of prolonged release via microencapsulation is necessary for widespread needs to regulate cellular activities in the long term during wound healing and tissue regeneration. Microencapsulation using biodegradable polymers offers unique advantages over other delivery methods, such as controlled hydrolytic degradation and injectable dimensions.24

Despite previous meritorious efforts to investigate the therapeutic potential of TGFβ3, its effective use is limited by a number of common shortcomings, such as short half-life, in vivo instability, and relative inaccuracy of the delivery system.24 Long-term delivery via controlled release offers a potential to circumvent previous limitations associated with instantaneous application of TGFβ3, for example, in collagen scaffolds. A common approach of controlled release is by encapsulating peptides and proteins in microspheres.25 Poly-d-l-lactic-co-glycolic acid (PLGA) is degraded by hydrolysis into biocompatible byproducts, including lactic and glycolic acid monomers. Lactic and glycolic acids are eliminated in vivo as CO2 and H2O via the Krebs cycle, eliciting minimal immune response.26,27 PLGA microspheres can be readily fabricated using the double-emulsion solvent-extraction technique, which allows the control of sphere diameter and degradation kinetics, while maintaining the stability and bioactivity of the encapsulated growth factors. The encapsulation and release kinetics of several growth factors, such as BMPs, TGFβ1 and 2, neurotrophic growth factors, VEGF, and IGFs, have been established.25,28–36 However, microencapsulation of TGFβ3 and its release kinetics is unknown. TGFβ3 has been shown to inhibit cranial suture ossification.13 Accordingly, we hypothesize that TGFβ3 regulates osteogenic differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells. The other two mammalian isoforms, TGFβ1 and 2, promote cranial suture fusion and osteogenesis.34,37 TGFβ1 has been shown to enhance the proliferation and osteoblastic differentiation of marrow stromal cells cultured on poly(propylene fumarate) substrates. TGFβ1 and 2 are continuously present during the osseous obliteration of the frontonasal suture of the rat. TGFβ3, in contrast, is associated with the maintenance of the rat coronal suture unossified state.38 In this work, we encapsulated TGFβ3 in PLGA microspheres, determined its release kinetics, and investigated the bioactivity of control-released TGFβ3 on osteogenic differentiation of human mesenchymal stem cells (hMSC). On the practical end, we also studied the effects of several commonly used sterilization methods on the morphology of PLGA microspheres and the release kinetics of encapsulated growth factor. These include ultraviolet light, ethylene oxide gas, and radiofrequency glow discharge, and were designed to aid in the choice of sterilization modality in subsequent in vivo studies using PLGA microspheres encapsulating various growth factors.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Preparation of PLGA microspheres and encapsulation of TGFβ3

Microspheres of poly(d-l-lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA, Sigma, St. Louis, MO) of 50:50 and 75:25 PLA/PGA ratios (Sigma) were prepared using double-emulsion technique ([water-in-oil]-in-water).25,39,40 A total of 250 mg PLGA was dissolved into 1 mL dichloromethane, and 2.5 μg of recombinant human TGFβ3 with molecular weight of 25 kDa (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) was diluted in 50 μL of reconstituting solution per manufacturer protocol and added to the PLGA solution, forming a mixture (primary emulsion) that was emulsified for 1 min (water-in-oil). The primary emulsion was then added to 2 mL of 1% polyvinyl alcohol (PVA, 30,000–70,000 MW), followed by 1 min mixing ([water-in-oil]-in-water). Upon adding 100 mL PVA solution, the mixture was stirred for 1 min. A total of 100 mL of 2% isopropanol was added to the final emulsion and continuously stirred for 2 h under chemical hood to remove the solvent. Control microspheres (empty and without TGFβ3) were fabricated using the same procedures, with the exception of using 50 μL distilled water instead of the TGFβ3 solution.41 Empty microspheres containing only water as controls were implemented to subtract the possible effects of degradation byproducts of PLGA alone. PLGA microspheres containing TGFβ3 or distilled water were isolated using filtration (2 μm filter) and washed with distilled water. Microspheres were frozen in liquid nitrogen for 30 min and lyophilized for 48 h. Freeze-dried PLGA microspheres were stored at −20°C prior to use.

Sterilization of PLGA microspheres

In wound healing and regenerative medicine, microspheres must be sterilized prior to in vivo use. In order to determine the efficacy of several commonly used sterilization techniques, basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF) was encapsulated in PLGA microspheres with 50:50 PLA/PGA ratio using the same technique described above. The rationale for using bFGF instead of TGFβ3 was that bFGF is more cost efficient than TGFβ3 and has similar structural properties. Although the solubility properties of bFGF may differ from TGFβ3, resulting in different encapsulation efficiencies and release kinetics, the effects of sterilization on polymer structural changes following sterilization may be comparable. The fabricated bFGF-encapsulating PLGA microspheres were randomly divided into three groups: 1) placed under ultraviolet light (UV) for 30 min (n = 3); 2) exposed to ethylene oxide gas (EO) for 24 h (n = 3); or 3) exposed to radiofrequency glow discharge (RFGD) for 4 min at 100 W (n = 3). Four hours following the three sterilization modalities, scanning electron microscopy (SEM) was used to determine the surface morphology of bFGF-encapsulating PLGA microspheres. In addition, immediately after all three sterilization modalities, 10 mg bFGF-encapsulating PLGA microspheres were separately weighed and immersed in 1 mL of 1% BSA solution in water bath at 60 rpm and 37°C to determine bFGF release kinetics. Supernatants were fully collected on days 7, 14, 21, and 28 after centrifuging at 5000 rpm for 10 min. After each collection, fresh 1 mL of 1% BSA was added to microspheres. Release kinetics was measured using a bFGF enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kit (bFGF ELISA, R&D Systems).

In vitro TGFβ3 release kinetics

After freeze-drying, the actual amount of encapsulated TGFβ3 per mL in units of mg of PLGA microspheres was detected using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kit (TGFβ3 ELISA, R&D Systems) in the hydrophilic extraction of the dissolved PLGA microspheres. TGFβ3-encapsulating PLGA microspheres (10 mg) were dispersed in 1 mL of 1% BSA solution and continuously agitated in water bath at 60 rpm and 37°C (n = 3). The entire amount of supernatants was collected periodically, and the amount of TGFβ3 was quantitatively measured using the TGFβ3 ELISA kit for each sample. The TGFβ3 release rate was expressed as a percentage of the total TGFβ3/mg PLGA microspheres. Entrapment yield was determined by dissolving 10 mg of TGFβ3-encapsulating PLGA microspheres in 1mL of chloroform and adding 1 mL of 1% BSA solution (n = 3). Mixtures were allowed to settle for 6 h, and TGFβ3-rich solution was collected for quantification of amount encapsulated using ELISA. PLGA microspheres encapsulating TGFβ3 were imaged with SEM on day 4 of exposure to aqueous solution to observe surface morphology.

Culture and osteogenic differentiation of human mesenchymal stem cells

Human mesenchymal stem cells (hMSCs) were isolated from the bone marrow of an anonymous healthy donor (All Cells, Berkeley, CA), culture-expanded in 6-well plates at a density of 30,000 cell/well.42,43 Monolayer hMSC cultures were maintained at 37°C, 95% humidity, and 5% CO2, using Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM-c, Sigma) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Atlanta Biologicals, Norcross, GA) and 1% antibiotics and antimycotics (10,000 U/mL penicillin [base], 10,000 μg/mL streptomycin [base], 25 μg/mL amphotericin B) (Atlanta Biologicals). Media were changed every 3 to 4 days. Human MSCs were differentiated into osteogenic cells with osteogenic supplements containing 100 nM dexamethasone, 50 μg/mL ascorbic acid, and 100 mM β-glycerophosphate.42,43 Per our prior experience, MSCs treated with the osteogenic supplements begin to differentiate into osteoblast-like cells that express multiple osteoblast markers.42–44 The early osteogenic potential of hMSC-derived cells was evaluated by alkaline phosphatase (ALP) staining and quantification using enzyme reagent.42,43

Bioactivity of control-released TGFβ3 on osteogenic differentiation of hMSCs

Ethylene oxide gas sterilized 50:50 co-polymer ratio TGFβ3-encapsulating PLGA microspheres (20 mg yielding 1.35 ng/2 mL of medium in 7 days, estimated from release kinetics) (Fig. 4) were placed in transwell inserts (0.4 μm pore size) (Becton Dickinson Labware, Franklin Lakes, NJ).25 The transwell inserts with microspheres were placed in cell culture wells, approximately 0.9 mm above the monolayer culture of undifferentiated hMSCs, exposing the cells to released TGFβ3 without direct contact with PLGA microspheres. At this time, osteogenic-supplemented DMEM was added (n = 3). In the control group, 0 or 1.35 ng/mL TGFβ3 solution without microsphere encapsulation was added along with osteogenic-supplemented medium to monolayer culture of hMSCs (n = 3). Osteogenic-supplemented medium was changed at day 3. Fresh TGFβ3 in solution was added to the control group at medium changes. ALP activity of hMSC-derived osteogenic cells exposed to TGFβ3 in solution (without microsphere encapsulation) was measured after 7 days and compared to the ALP activity of hMSC-derived osteogenic cells exposed to the same-dosed TGFβ3 (1.35 ng/mL) released from PLGA microspheres (n = 3). The TGFβ3 release amount obtained above was estimated from the amount of TGFβ3 released from 20 mg PLGA microspheres over the initial 7 days. Alkaline phosphatase activity was measured using ALP Reagent (Raichem, San Diego, CA) and normalized to DNA content of hMSC-derived osteogenic cells. DNA content was measured using a fluorescent DNA quantification kit (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA).42

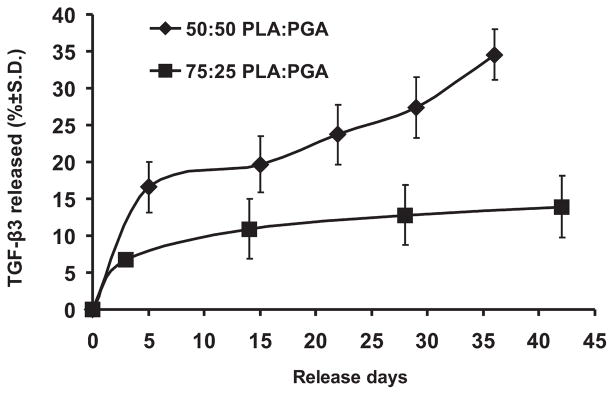

FIG. 4.

Release kinetics of TGFβ3 from PLGA microspheres in 1% BSA solution. TGFβ3 was released in a sustained fashion up to 36 and 42 days from 50:50 or 75:25 co-polymer ratios of PLGA microspheres, respectively, as detected by ELISA. Initial burst-like release was observed for both co-polymer ratios, although the 50:50 PLA/PGA ratio yielded a more rapid release rate than the 75:25 PLA/PGA ratio did.

Statistical analysis

Student’s t tests and ANOVA were used to compare the release rates of bFGF-encapsulating PLGA microspheres after different sterilization modalities, TGFβ3 release rates between 50:50 and 75:25 PLA/PGA ratios, and ALP activity of hMSC-derived osteogenic cells between control group (TGFβ3-free) and two experimental groups (release from PLGA microspheres or directly added to cell culture medium). All statistical analyses were performed with an α level of 0.05 using Minitab 14 software (State College, PA).

RESULTS

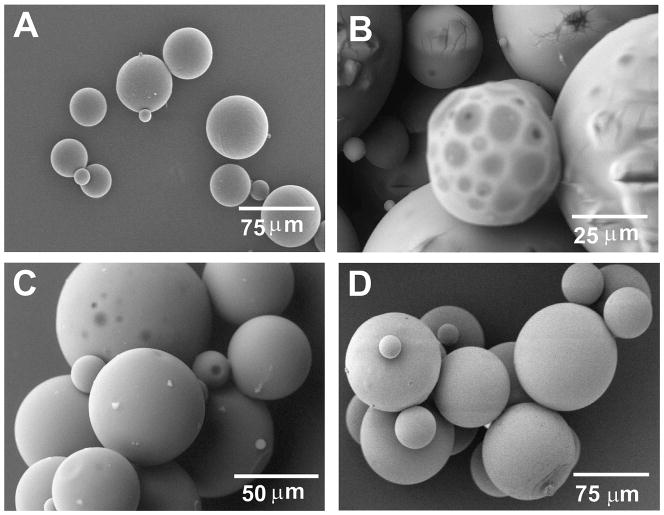

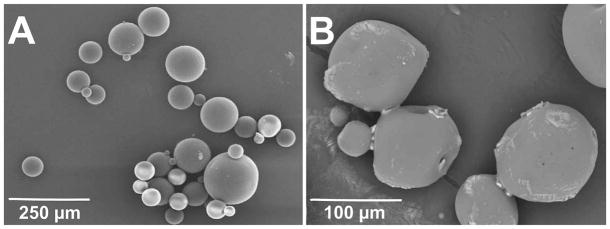

TGFβ3 encapsulated in PLGA microspheres

TGFβ3-encapsulating PLGA microspheres prepared by double-emulsion solvent-extraction technique produced a spherical shape and smooth surface for the two compositions of PLGA (Fig. 1A). The average diameter of TGFβ-encapsulating PLGA microspheres was 108 ± 62 μm (Fig. 1A). Upon emersion in aqueous solution for 4 days, PLGA microspheres apparently began surface degradation (Fig. 1B).

FIG. 1.

Fabrication and degradation of PLGA microspheres. (A) Representative SEM image of microspheres fabricated from poly-d-l-lactic-co-glycolic acid (PLGA) with 50:50 PLA/PGA ratio with encapsulated TGFβ3. The average diameter of TGFβ3-encapsulating PLGA microspheres was 108 ± 62 μm. (B) Representative SEM image of anticipated degradation of TGFβ3-encapsulating PLGA microspheres in PBS solution after 4 days.

Sterilization of PLGA microspheres and bFGF release kinetics

Different sterilization methods for PLGA microspheres had different effects on their surface degradation by SEM. PLGA microspheres sterilized with UV light showed marked surface deleterious effects (Fig. 2B) in comparison with non-sterilized PLGA microspheres (Fig. 2A). In contrast, EO gas and RFGD appeared to induce minimal morphological changes on the surface degradation of PLGA microspheres (Fig. 2C and D).

FIG. 2.

Morphological changes of sterilized PLGA microspheres under SEM. (A) Unsterilized PLGA microspheres. (B) Ultraviolet (UV) light-sterilized PLGA microspheres (30 min) showing severe detrimental effect of UV sterilization. (C) Ethylene oxide (EO) gas-sterilized PLGA microspheres for 24 h. (D) Radiofrequency glow discharge (RFGD)-sterilized PLGA microspheres (4 min, 100 W). In contrast to severe surface degradation changes induced by UV light, EO gas and RFGD did not yield marked surface degradation of PLGA microspheres.

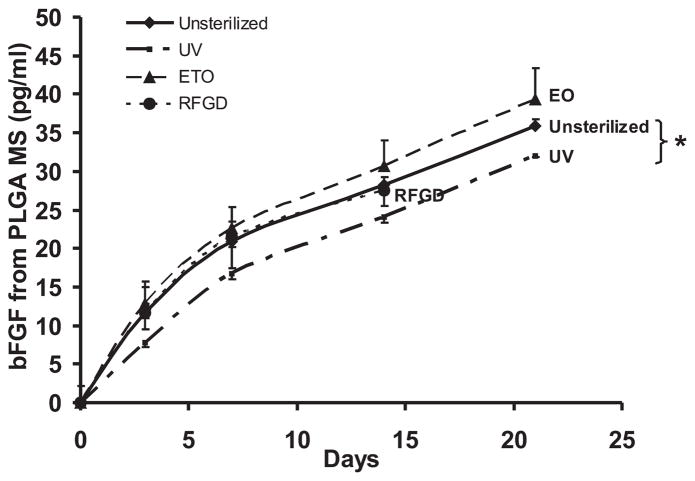

The bFGF release rate was significantly reduced after UV light sterilization in comparison with each of the non-sterilized PLGA microspheres, EO or RFGD sterilization modalities (Fig. 3). This reduction in bFGF release rate upon UV treatment corroborated with the SEM observation of degrading surface structures of PLGA microspheres after UV sterilization (Fig. 2B). No statistically significant difference was found in the bFGF release rates of either EO- or RFGD-sterilized PLGA microsphere from non-sterilized controls (Fig. 3). Accordingly, EO gas was chosen as the sterilization technique for TGFβ3-encapsulated PLGA microspheres in subsequent experiments because of lower cost and less damage to microsphere morphology.

FIG. 3.

Release kinetics of bFGF from PLGA microspheres. UV light significantly altered the release rate of bFGF from PLGA microspheres up to 21 days (n = 3, *p < 0.05). No significant changes in release kinetics were observed after EO gas or RFGD sterilizations. Ethylene oxide seemed to be the most economically efficient and safe sterilization method for cytokine-encapsulating PLGA microspheres.

TGFβ3 release kinetics

TGFβ3 from PLGA microspheres was released up to the tested 36 and 42 days in vitro for both 50:50 and 75:25 co-polymer ratios of PLA/PGA, respectively (Fig. 4). The TGFβ3 entrapment yield was 0.68 ng/mL per mg of 75:25 PLGA microspheres and 0.84 ng/mL per mg of 50:50 PLGA microspheres. A burst-like release was observed for PLGA microspheres with either 50:50 or 75:25 co-polymer ratios during the first week, followed by more gradual increases in release rate for the 75:25 polymer ratio (Fig. 4). More rapid release of TGFβ3 was obtained for the 50:50 co-polymer ratio of PLA/PGA than for the 75:25 PLA/PGA (Fig. 4), likely due to the more rapid degradation rate of 50:50 PLGA. Approximately 8% of the encapsulated TGFβ3 by 75:25 PLGA was released within the first week versus nearly 16% TGFβ3 release from 50:50 PLGA for the same time period. After 35 days, approximately 14 and 34% TGFβ3 were released from 75:25 and 50:50 co-polymer ratios of PLGA, respectively.

Inhibition of osteogenic differentiation of hMSCs

Human MSCs expressed a relatively high average alkaline phosphatase by day 7 culture in osteogenic-supplemented medium in vitro, as evidenced by both ALP staining (red) and quantification using enzyme reagent (Fig. 5A and C). ALP activity of hMSC cells exposed to TGFβ3 (1.35 ng/mL) released from PLGA microspheres by day 7 culture in osteogenic-supplemented medium was significantly inhibited, as evidenced by not only reduced ALP staining (Fig. 5B) but also quantitative amount of ALP (Fig. 5C). The same-dose TGFβ3 (1.35 ng/mL) added directly to culture medium of hMSC (without microencapsulation) also yielded significantly less ALP activity than hMSC without exposure to exogenously delivered TGFβ3 (Fig. 5C). Moreover, the lack of statistically significant differences in ALP reductions between TGFβ3 added to cell culture medium and the same-dosed TGFβ3 released from PLGA microspheres (Fig. 5C) indicated that bioactive TGFβ3 was released from PLGA microspheres after microencapsulation and subsequent EO sterilization.

FIG. 5.

Alkaline phosphatase (ALP) activity of human mesenchymal stem cells (hMSCs) cultured with osteogenic-supplemented medium for 7 days. (A) ALP staining (red) upon exposure to TGFβ3-free PLGA microspheres. (B) ALP staining (red) upon exposure to TGFβ3 released from PLGA microspheres. Red stain was limited to isolated regions, as shown by white arrowhead. (C) ALP activity of hMSCs cultured in osteogenic-supplemented medium quantified by ALP reagent. Significant decrease in staining was observed for hMSCs cultured in osteogenic-supplemented medium in PLGA microsphere-delivered TGFβ3, suggesting that TGFβ3 at 1.35 ng/mL inhibits early osteogenic differentiation of hMSCs in vitro (n = 3, p < 0.05). magnification × 10 (Color images available online at <www.liebertpub.com/ten>.)

Previous work has shown that TGFβ3 induces chondrogenic differentiation of MSCs at a much greater concentration (10 ng/mL) than in the present study (1.35 ng/mL).42 To rule out chondrogenesis by the present TGFβ3 dose of up to 1.35 ng/mL, we found negative safranin-O staining of hMSC monolayer cultured with TGFβ3-loaded PLGA microspheres (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

The present findings of sustained release of TGFβ3 in PLGA microspheres may be useful in wound healing and tissue regeneration models. Long-term delivery of TGFβ3 via controlled release approach may regulate cell recruitment, proliferation, and differentiation.45 TGFβ3 acts on cell metabolism via the Smad pathways to target gene transcription.46 The type I and II dimeric TGFβ receptors capture TGFβ3 at cell surface and activate a cascade of Smad events, relaying the signal to the cell nucleus.47,48 Sustained release enables prolonged delivery of cytokines in contrast to diffusion, inactivation, and loss of bioactivity associated with injection or soaking cytokines in biomaterials.25,28–31 The presently identified TGFβ3 sustained release profiles from PLGA microspheres using 50:50 and 75:25 PLA/PGA ratios suggest that the release rates of TGFβ3 from PLGA microspheres can be readily tailored to specific degradation needs by modifying the PLA/PGA ratio. The methyl group in PLA is responsible for its hydrophobic and slow degradation. PGA is crystalline and increases degradation times.49 Therefore, different ratios of PGA and PLA are likely necessary for various applications in wound healing and tissue engineering to accommodate specific growth factor release rates. The present study, despite its novelty in showing sustained release of TGFβ3 and its inhibitory effects on osteogenic differentiation of hMSCs, did not explore additional variables in PLGA microsphere fabrication capable of altering the release kinetics. This profile was expected as previously shown release of TGFβ1 followed a similar curve.25 Although the initial burst release was lower than expected, the preparation of PLGA microspheres did not include techniques to prevent the burst. The encapsulation of TGFβ3 in PLGA microspheres is a novel approach, and relatively lower initial burst release may be attributed to specific growth factor-polymer interactions. The TGFβ3 release rates from PLGA microspheres appear to be consistent with previous demonstration of hydrolysis of PLGA microspheres in aqueous environment and subsequent release of other encapsulated growth factors.26,27,50 Short-term release of TGFβ from bio-polymer surfaces presents the potential for immediate delivery.15 The present delivery system for TGFβ3 via PLGA microspheres provides a mechanism for sustained long-term release.

The application of PLGA microspheres in drug delivery and regenerative medicine requires adequate preparation methods, including appropriate sterilization techniques. The optimal sterilization technique should maintain the bioactivity and the predefined release kinetics of the encapsulated growth factors. The present demonstration that UV light induced surface damage of bFGF-encapsulated PLGA microspheres and reduced the rate of growth factor release significantly more than both EO gas and RFGD, if sustained by additional work, such as sterilization-caused growth factor degradation studies, appears to caution the use of UV light for PLGA microsphere sterilization. The reduced release rate may be attributed to polymer surface and/or bulk degradation during sterilization and consequent decreases in the amount of bFGF. Also, direct growth factor degradation due to light, as previously postulated, may explain the decreases in bFGF release rate from UV-sterilized PLGA microspheres.51,52 Nonetheless, surface degradation is observed subsequent to incubation in aqueous environment, suggestive of hydrolysis of the polymer structure.

Neither EO gas nor RFGD significantly alters the release kinetics of bFGF from PLGA microspheres. Although sterilization using gamma irradiation is well documented,53,54 the equipment for gamma-irradiation sterilization may not be widely available in most laboratories. Accordingly, ethylene oxide appears to be the logical choice for the sterilization of growth factor-encapsulating PLGA microspheres.

The bioactivity of TGFβ3 released from PLGA microspheres is verified by a lack of statistically significant differences in ALP activity of osteogenic cells derived from hMSCs between microsphere-released TGFβ3 and the same-dose TGFβ3 added directly to cell culture. The small discrepancy observed between ALP activity levels in the two TGFβ3 delivery methods could be accounted for by the potentially different rates of TGFβ3 binding to cell surface receptors. In the non-encapsulated TGFβ3 group, the entire experimental TGFβ3 dose was added initially, whereas the full dose of TGFβ3 from PLGA microspheres was released in a sustained fashion throughout the experiment.

The inhibitory effects of TGFβ3 on osteogenic differentiation of hMSCs are potentially useful in several tissue-engineering models. For example, undesirable ectopic bone formation occurs in approximately 28% of tissue-engineered rabbit tendon repairs from mesenchymal stem cells.55 Sustained release of TGFβ3 from PLGA microspheres, as demonstrated here, may help reduce the incidence of ectopic bone formation. Unintended osteogenic differentiation of MSCs may occur in articular cartilage tissue engineering and can potentially be dealt with by the delivery of TGFβ3 in microspheres. At higher doses, TGFβ3 or TGFβ1 (typically 10 ng/mL) induces chondrogenic differentiation of MSCs.42,43

Another tissue-engineering model for sustained release of TGFβ3 is to inhibit osteoblast activity and to prevent premature ossification of cranial sutures, a pathological condition leading to craniosynostosis manifesting as skull deformities, seizure, and blindness.4–6 Recent report of tissue-engineered cranial sutures, if applied to a craniosynostosis model, may suffer the same fate of premature ossification as pathologically synostosed cranial sutures.56,57 Previous attempts to deliver TGFβ3 to synostosing cranial sutures have demonstrated that TGFβ3 delays their premature ossification.13,14 However, previous approaches of TGFβ3 delivery may be further improved by a sustained release approach that enables more prolonged action and precise control of the encapsulated growth factor. The present data demonstrate that early osteogenic differentiation of hMSCs in vitro can be inhibited by TGFβ3 in both encapsulated and non-encapsulated forms. Due to the mesenchymal tissue nature of patent cranial sutures, MSCs likely play a pivotal role in premature suture ossification.58 Studies are under way to examine long-term inhibition of sutural osteogenesis using sustained delivery systems in vivo.

The present study has a number of caveats. Only two PLA/PGA ratios were investigated, and notably without measurements of the degradation rates of PLGA polymers, considering that degradation rates of PLGA microspheres have been previously investigated.25,27 As the release profile was significantly attenuated after the first week, other variables in PLGA microsphere fabrication, such as polymer concentration, should be included in future studies to achieve controlled release of TGFβ3. In addition, only commonly used parameters associated with UV, EO, and RFGD, such as sterilization time, were tested, without consideration of other time and intensity parameters of each sterilization modality. Therefore, the present conclusion of damage of PLGA microspheres by UV light, but not by EO gas and RFGD, may only apply to the presently tested parameters. Additionally, this study was not designed to include the analysis of bFGF degradation due to sterilization, nor does it demonstrate bulk degradation of PLGA microspheres. The sterilization modalities could potentially degrade encapsulated bFGF and then alter its release kinetics. Future studies should include bulk degradation evaluation due to sterilization.

The present study only considered exogenously delivered TGFβ3 and was not designed to investigate the effects of exogenously delivered TGFβ3 on autocrine production of TGFβ3 by marrow-derived MSCs. It is important to recognize that host tissue responses in vivo to implanted biomaterials may generate differences in local pH and environment, possibly by changing the degradation of PLGA microspheres and affecting the parameters shown in the present results.25 Nonetheless, microspheres encapsulating various growth factors implanted in vivo have shown bioactive sustained release.28,30,39,59 Within the constraints of the present experimental design, our findings may provide baseline data for potential uses of microencapsulated TGFβ3 in wound healing and tissue-engineering applications.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Aurora Lopez for general technical assistance and Dr. Gwendolen Reilly for thoughtful suggestions on several experimental techniques. We thank three anonymous reviewers whose insightful comments helped improve our manuscript. J. Guardado’s work on PLGA microsphere sterilization was supported by Summer Research Opportunity Program. This research was supported by NIH Grants DE13964, DE15391, and EB02332 given to J.J. Mao.

Footnotes

This paper was presented in part at the 51st annual meeting of the Orthopaedic Research Society, Washington, D.C., February, 2005.

References

- 1.Hosokawa R, Nonaka K, Morifuji M, Shum L, Ohishi M. TGF-beta 3 decreases type I collagen and scarring after labioplasty. J Dent Res. 2003;82:558. doi: 10.1177/154405910308200714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Levine JH, Moses HL, Gold LI, Nanney LB. Spatial and temporal patterns of immunoreactive transforming growth factor beta 1, beta 2, and beta 3 during excisional wound repair. Am J Pathol. 1993;143:368. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kohama K, Nonaka K, Hosokawa R, Shum L, Ohishi M. TGF-beta-3 promotes scarless repair of cleft lip in mouse fetuses. J Dent Res. 2002;81:688. doi: 10.1177/154405910208101007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cohen MM., Jr Craniofacial disorders caused by mutations in homeobox genes MSX1 and MSX2. J Craniofac Genet Dev Biol. 2000;20:19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Opperman LA, Galanis V, Williams AR, Adab K. Transforming growth factor-beta3 (Tgf-beta3) down-regulates Tgf-beta3 receptor type I (Tbetar-I) during rescue of cranial sutures from osseous obliteration. Orthod Craniofac Res. 2002;5:5. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0544.2002.01179.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Greenwald JA, Mehrara BJ, Spector JA, Warren SM, Crisera FE, Fagenholz PJ, Bouletreau PJ, Longaker MT. Regional differentiation of cranial suture-associated dura mater in vivo and in vitro: implications for suture fusion and patency. J Bone Miner Res. 2000;15:2413. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2000.15.12.2413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Richman JM, Kollar EJ. Tooth induction and temporal patterning in palatal epithelium of fetal mice. Am J Anat. 1986;175:493. doi: 10.1002/aja.1001750408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gato A, Martinez ML, Tudela C, Alonso I, Moro JA, Formoso MA, Ferguson MW, Martinez-Alvarez C. TGF-beta(3)-induced chondroitin sulphate proteoglycan mediates palatal shelf adhesion. Dev Biol. 2002;250:393. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Copland IB, Adamson SL, Post M, Lye SJ, Caniggia I. TGF-beta 3 expression during umbilical cord development and its alteration in pre-eclampsia. Placenta. 2002;23:311. doi: 10.1053/plac.2001.0778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kay EP, Lee MS, Seong GJ, Lee YG. TGF-beta 3 stimulate cell proliferation via an autocrine production of FGF-2 in corneal stromal fibroblasts. Curr Eye Res. 1998;17:286. doi: 10.1076/ceyr.17.3.286.5212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kay EP, Lee HK, Park KS, Lee SC. Indirect mitogenic effect of transforming growth factor-beta on cell proliferation of subconjunctival fibroblasts. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1998;39:481. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hirshberg J, Coleman J, Marchant B, Rees RS. TGF-beta3 in the treatment of pressure ulcers: a preliminary report. Adv Skin Wound Care. 2001;14:91. doi: 10.1097/00129334-200103000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Opperman LA, Moursi AM, Sayne JR, Wintergerst AM. Transforming growth factor-beta 3(Tgf-beta3) in a collagen gel delays fusion of the rat posterior inter-frontal suture in vivo. Anat Rec. 2002;267:120. doi: 10.1002/ar.10094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chong SL, Mitchell R, Moursi AM, Winnard P, Losken HW, Bradley J, Ozerdem OR, Azari K, Acarturk O, Opperman LA, Siegel MI, Mooney MP. Rescue of coronal suture fusion using transforming growth factor-beta 3 (Tgf-beta 3) in rabbits with delayed-onset craniosynostosis. Anat Rec Discov Mol Cell Evol Biol. 2003;274:962. doi: 10.1002/ar.a.10113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Parker JA, Brunner G, Walboomers XF, Von den Hoff JW, Maltha JC, Jansen JA. Release of bioactive transforming growth factor beta(3) from microtextured polymer surfaces in vitro and in vivo. Tissue Eng. 2002;8:853. doi: 10.1089/10763270260424213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Garcia-Fuentes M, Alonso MJ, Torres D. Design and characterization of a new drug nanocarrier made from solid-liquid lipid mixtures. J Colloid Interface Sci. 2005;15:590. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2004.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Prabaharan M, Mano JF. Chitosan-based particles as controlled drug delivery systems. Drug Deliv. 2005;12:41. doi: 10.1080/10717540590889781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Muvaffak A, Gurhan I, Hasirci N. Prolonged cytotoxic effect of colchicine released from biodegradable microspheres. J Biomed Mater Res Appl Biomater. 2004;15:295. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.30092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ksander GA, Ogawa Y, Chu GH, McMullin H, Rosenblatt JS, McPherson JM. Exogenous transforming growth factor-beta 2 enhances connective tissue formation and wound strength in guinea pig dermal wounds healing by secondary intent. Ann Surg. 1990;211:288. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pandit A, Ashar R, Feldman D. The effect of TGF-beta delivered through a collagen scaffold on wound healing. J Invest Surg. 1999;12:89. doi: 10.1080/089419399272647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Midy V, Rey C, Bres E, Dard M. Basic fibroblast growth factor adsorption and release properties of calcium phosphate. J Biomed Mater Res. 1998;5:405. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4636(19980905)41:3<405::aid-jbm10>3.0.co;2-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gombotz WR, Pankey SC, Bouchard LS, Phan DH, Puolakkainen PA. Stimulation of bone healing by transforming growth factor-beta 1 released from polymeric or ceramic implants. J Appl Biomater. 1994;5:141. doi: 10.1002/jab.770050207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nicoll SB, Radin S, Santos EM, Tuan RS, Ducheyne P. In vitro release kinetics of biologically active transforming growth factor-beta 1 from a novel porous glass carrier. Biomaterials. 1997;18:853. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(97)00008-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Holland TA, Mikos AG. Advances in drug delivery for articular cartilage. J Cont Release. 2003;86:1. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(02)00373-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lu L, Yaszemski MJ, Mikos AG. TGF-beta1 release from biodegradable polymer microparticles: its effects on marrow stromal osteoblast function. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2001;83:S82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ding AG, Schwendeman SP. Determination of water-soluble acid distribution in poly(lactide-co-glycolide) J Pharm Sci. 2004;93:322. doi: 10.1002/jps.10524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cohen S, Yoshioka T, Lucarelli M, Hwang LH, Langer R. Controlled delivery systems for proteins based on poly(lactic/glycolic acid) microspheres. Pharm Res. 1991;8:713. doi: 10.1023/a:1015841715384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Woo BH, Fink BF, Page R, Schrier JA, Jo YW, Jiang G, DeLuca M, Vasconez HC, DeLuca PP. Enhancement of bone growth by sustained delivery of recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2 in a polymeric matrix. Pharm Res. 2001;18:1747. doi: 10.1023/a:1013382832091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Oldham JB, Lu L, Zhu X, Porter BD, Hefferan TE, Larson DR, Currier BL, Mikos AG, Yaszemski MJ. Biological activity of rhBMP-2 released from PLGA microspheres, J. Biomech Eng. 2000;122:289. doi: 10.1115/1.429662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Carrascosa C, Torres-Aleman I, Lopez-Lopez C, Carro E, Espejo L, Torrado S, Torrado JJ. Microspheres containing insulin-like growth factor I for treatment of chronic neurodegeneration. Biomaterials. 2004;25:707. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(03)00562-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jiang W, Gupta RK, Deshpande MC, Schwendeman SP. Biodegradable poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) microparticles for injectable delivery of vaccine antigens. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2005;57:391. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2004.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cleland JL, Duenas ET, Park A, Daugherty A, Kahn J, Kowalski J, Cuthbertson A. Development of poly-(D,L-lactide—coglycolide) microsphere formulations containing recombinant human vascular endothelial growth factor to promote local angiogenesis. J Control Release. 2001;72:13. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(01)00258-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kojima K, Ignotz RA, Kushibiki T, Tinsley KW, Tabata Y, Vacanti CA. Tissue-engineered trachea from sheep marrow stromal cells with transforming growth factor beta2 released from biodegradable microspheres in a nude rat recipient. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2004;128:147. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2004.02.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Peter SJ, Lu L, Kim DJ, Stamatas GN, Miller MJ, Yaszemski MJ, Mikos AG. Effects of transforming growth factor beta1 released from biodegradable polymer microparticles on marrow stromal osteoblasts cultured on poly(propylene fumarate) substrates. J Biomed Mater Res. 2000;5:452. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4636(20000605)50:3<452::aid-jbm20>3.0.co;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Aubert-Pouessel A, Venier-Julienne MC, Clavreul A, Sergent M, Jollivet C, Montero-Menei CN, Garcion E, Bibby DC, Menei P, Benoit JP. In vitro study of GDNF release from biodegradable PLGA microspheres. J Control Release. 2004;95:463. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2003.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mittal S, Cohen A, Maysinger D. In vitro effects of brain derived neurotrophic factor released from microspheres. Neuroreport. 1994;5:2577. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199412000-00043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Opperman LA, Nolen AA, Ogle RC. TGF-beta 1, TGF-beta 2, and TGF-beta 3 exhibit distinct patterns of expression during cranial suture formation and obliteration in vivo and in vitro. J Bone Miner Res. 1997;12:301. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.1997.12.3.301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Poisson E, Sciote JJ, Koepsel R, Cooper GM, Opperman LA, Mooney MP. Transforming growth factor-beta isoform expression in the perisutural tissues of craniosynostotic rabbits. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 2004;41:392. doi: 10.1597/02-140.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wei G, Pettway GJ, McCauley LK, Ma PX. The release profiles and bioactivity of parathyroid hormone from poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) microspheres. Biomaterials. 2004;25:345. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(03)00528-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ruan G, Feng SS, Li QT. Effects of material hydrophobicity on physical properties of polymeric microspheres formed by double emulsion process. J Control Release. 2002;84:151. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(02)00292-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cleek RL, Rege AA, Denner LA, Eskin SG, Mikos AG. Inhibition of smooth muscle cell growth in vitro by an antisense oligodeoxynucleotide released from poly(DL-lactic-co-glycolic acid) microparticles. J Biomed Mater Res. 1997;35:525. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4636(19970615)35:4<525::aid-jbm12>3.0.co;2-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Alhadlaq A, Elisseeff JH, Hong L, Williams CG, Caplan AI, Sharma B, Kopher RA, Tomkoria S, Lennon DP, Lopez A, Mao JJ. Adult stem cell driven genesis of human-shaped articular condyle. Ann Biomed Eng. 2004;32:911. doi: 10.1023/b:abme.0000032454.53116.ee. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Alhadlaq A, Mao JJ. Mesenchymal stem cells: isolation and therapeutics. Stem Cells Dev. 2004;13:436. doi: 10.1089/scd.2004.13.436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Alhadlaq A, Mao JJ. Tissue-engineered neogenesis of human-shaped mandibular condyle from rat mesenchymal stem cells. J Dent Res. 2003;82:951. doi: 10.1177/154405910308201203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ferguson MW, O’Kane S. Scar-free healing: from embryonic mechanisms to adult therapeutic intervention. Philos Trans R Soc Lond Biol Sci. 2004;359:839. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2004.1475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chin GS, Liu W, Peled Z, Lee TY, Steinbrech DS, Hsu M, Longaker MT. Differential expression of transforming growth factor-beta receptors I and II and activation of Smad 3 in keloid fibroblasts. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2001;108:423. doi: 10.1097/00006534-200108000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schiller M, Javelaud D, Mauviel A. TGF-beta-induced SMAD signaling and gene regulation: consequences for extracellular matrix remodeling and wound healing. J Dermatol Sci. 2004;35:83. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2003.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Verrecchia F, Mauviel A. Transforming growth factor-beta signaling through the Smad pathway: role in extracellular matrix gene expression and regulation. J Invest Dermatol. 2002;118:211. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2002.01641.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ratner BD, Schoen FJ, Hoffman AS, Lemons JE. Biomaterials Science: An Introduction to Materials in Medicine. New York: Academic Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Elisseeff J, McIntosh W, Fu K, Blunk BT, Langer R. Controlled-release of IGF-I and TGF-beta1 in a photopolymerizing hydrogel for cartilage tissue engineering. J Orthop Res. 2001;19:1098. doi: 10.1016/S0736-0266(01)00054-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Baroli B, Shastri VP, Langer R. A method to protect sensitive molecules from a light-induced polymerizing environment. J Pharm Sci. 2003;92:1186. doi: 10.1002/jps.10378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lewis KJ, Irwin WJ, Akhtar S. Development of a sustained-release biodegradable polymer delivery system for site-specific delivery of oligonucleotides: characterization of P(LA-GA) copolymer microspheres in vitro. J Drug Target. 1998;5:291. doi: 10.3109/10611869808995882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Martinez-Sancho C, Herrero-Vanrell R, Negro S. Study of gamma-irradiation effects on aciclovir poly(D,L-lactic-co-glycolic) acid microspheres for intravitreal administration. J Control Release. 2004;99:41. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2004.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Carrascosa C, Espejo L, Torrado S, Torrado JJ. Effect of gamma-sterilization process on PLGA microspheres loaded with insulin-like growth factor-I (IGF-I) J Biomater Appl. 2003;18:95. doi: 10.1177/088532803038026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Harris MT, Butler DL, Boivin GP, Florer JB, Schantz EJ, Wenstrup RJ. Mesenchymal stem cells used for rabbit tendon repair can form ectopic bone and express alkaline phosphatase activity in constructs. J Orthop Res. 2004;22:998. doi: 10.1016/j.orthres.2004.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mao JJ. Mechanobiology of craniofacial sutures. J Dent Res. 2002;81:810. doi: 10.1177/154405910208101203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hong L, Mao JJ. Tissue-engineered rabbit cranial suture from autologous fibroblasts and BMP2. J Dent Res. 2004;83:751. doi: 10.1177/154405910408301003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mao JJ, Nah HD. Growth and development: hereditary and mechanical modulations. Am J Orthod Dentofac Orthop. 2004;125:676. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2003.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kojima K, Ignotz RA, Kushibiki T, Tinsley KW, Tabata Y, Vacanti CA. Tissue-engineered trachea from sheep marrow stromal cells with transforming growth factor beta2 released from biodegradable microspheres in a nude rat recipient. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2004;128:147. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2004.02.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]