Abstract

Background

There is a paucity of preference-based (utility) measures of health-related quality of life for patients with ischemic heart disease (IHD); in contrast, the Seattle Angina Questionnaire (SAQ) is a widely used descriptive measure. Our objective was to perform a systematic review of the literature to identify IHD studies reporting SAQ scores in order to apply a mapping algorithm to convert these to preference-based scores for secondary use in economic evaluations.

Methods

Relevant articles were identified in MEDLINE (Ovid), EMBASE (Ovid), Cochrane Library (Wiley), HealthStar (Ovid), and PubMed from inception to 2012. We previously developed and validated a mapping algorithm that converts SAQ descriptive scores to European Quality of Life-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D) utility scores. In the current study, this mapping algorithm was used to estimate EQ-5D utility scores from SAQ scores.

Results

Thirty-six studies met the inclusion criteria. The studies were categorized into three groups, ie, general IHD (n=13), acute coronary syndromes (n=4), and revascularization (n=19). EQ-5D scores for patients with general IHD were in the range of 0.605–0.843 at baseline, and increased to 0.649–0.877 post follow-up. EQ-5D scores for studies of patients with recent acute coronary syndromes increased from 0.706–0.796 at baseline to 0.795–0.942 post follow-up. The revascularization studies had EQ-5D scores in the range of 0.616–0.790 at baseline, and increased to 0.653–0.928 after treatment; studies that focused only on coronary artery bypass grafting increased from 0.643–0.788 at baseline to 0.653–0.928 after grafting, and studies that focused only on percutaneous coronary intervention increased in score from 0.616–0.790 at baseline to 0.668–0.897 after treatment.

Conclusion

In this review, we provide a catalog of estimated health utility scores across a wide range of disease severity and following various interventions in patients with IHD. Our catalog of EQ-5D scores can be used in IHD-related economic evaluations.

Keywords: health-related quality of life, Seattle Angina Questionnaire, utilities, European Quality of Life-5 Dimensions, mapping algorithm, ischemic heart disease

Introduction

Economic evaluations with cost-effectiveness analyses are important in the decision-making process for health resource allocation. Cost-effectiveness analysis involves estimation of the incremental cost of a new intervention as well as its incremental net health benefit, in comparison with a reference. To facilitate the comparison of different interventions, it is important that the health effects be reported in standardized units. Current guidelines recommend that the metric of choice for reporting health benefits in cost-effectiveness analysis is the quality-adjusted life-year.1–5

A variety of techniques have been developed to assess patient quality of life. Available instruments can be generally classified into two major categories, ie, descriptive measurement instruments or preference-based methods. Descriptive measurement instruments are designed to measure quality of life across important aspects of a patient’s health state, such as physical, psychosocial, or functional well-being.6 Such instruments provide a score for each health domain and a quantitative measure that represents a patient’s current health state. In contrast, preference-based or utility instruments, such as the European Quality of Life-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D), add a valuation component to a patient’s reported health state.7 These instruments are designed to reflect both a quantitative description of a patient’s health state and society’s preference for that particular health state. This preference component is the primary distinction between a utility instrument and a descriptive measurement instrument. Preference-based instruments allow for the calculation of quality-adjusted life-years.

In ischemic heart disease (IHD) research, there is an abundance of published literature on the Seattle Angina Questionnaire (SAQ), a descriptive quality of life instrument. The SAQ is a validated descriptive instrument that evaluates quality of life in patients with IHD across five domains, specifically physical limitation, treatment satisfaction, angina frequency, angina stability, and disease perception.8 In contrast, there is a paucity of studies that report utility weights for patients with IHD.3 The absence of available and up-to-date utility weights is a substantial limitation when performing economic analyses in IHD. To address this lack of utility information, we have previously published a mapping algorithm to convert SAQ descriptive scores to utility weights, based on the EQ-5D preference-based utility instrument.9,10

In this study, we extended our previous work by performing a systematic review of the literature to identify all previous studies that used the SAQ to measure health state, and then applied our validated mapping algorithm to create a comprehensive catalog of utility weights across the spectrum of IHD, with the intention that our catalog be used for future economic evaluations in IHD.

Materials and methods

Search strategy

First, we conducted a systematic review of the published literature, conforming to the standards recommended by the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines.11 We used the search terms “Seattle Angina Questionnaire”, “SAQ”, or slight modifications of these terms (see Supplementary material for full search strategy) to identify potentially relevant citations from inception to November 7, 2012 using the following medical literature databases: MEDLINE (Ovid), EMBASE (Ovid), Cochrane Library (Wiley), HealthStar (Ovid), and PubMed. We subsequently performed a citation search in Google Scholar (Google), Web of Science (Thomson Reuters), and Scopus (Elsevier) to identify articles citing the original paper by Spertus et al8 that first examined the validity and reliability of the SAQ. Finally, we searched major clinical trial registries (clinicaltrials.gov and clinicaltrialsregister.eu) from inception to November 7, 2012 for studies that used the SAQ as an outcome measure, using the search terms “Seattle Angina Questionnaire” or “SAQ”.

Upon removal of duplications, two independent reviewers (SF and HCW) screened each reference. We utilized a hierarchal approach, screening citations by title, then abstract, and finally by full text to determine relevance. Reviewers assessed the eligibility of these selected articles according to two prespecified inclusion criteria, ie, that publication was in English and that mean scores and standard errors (or the ability to calculate standard errors from the available data) were reported for all five domains of the SAQ. Although the SAQ has been translated into multiple languages, the original SAQ validation studies were based on the English version; as such, we restricted our algorithm to English articles. All five domains were needed to utilize our mapping algorithm. Exclusion criteria were articles that reported on experimental interventions (eg, transmyocardial laser revascularization, herbal medicine) that are not part of standard therapy. The following information was extracted from eligible studies: baseline characteristics of study participants (age, gender); inclusion and exclusion criteria for each study, interventions (eg, myocardial infarction, revascularization) and follow-up duration; and reported SAQ scores and standard errors.

Data synthesis

We have previously created and published a prediction algorithm using multivariable linear regression modeling, with the utility weight from the EQ-5D being our response variable of interest. Details of the derivation and validation of the mapping algorithm are available elsewhere.9 In brief, all model fitting was done using Bayesian methods. The posterior probability distribution for each of the model parameters was estimated using Markov Chain Monte Carlo simulation methods, with noninformative prior distributions for all model parameters. The data for model development were from 1,992 consecutive patients who underwent coronary angiography in 2004 as part of the Alberta Provincial Project for Outcome Assessment in Coronary Heart Disease database. The final mapping algorithm was a linear regression model, with the dependent variable being the EQ-5D, and a conditional distribution of Yi∼N(μi,σi). The specification of the mean was given by:

with the following parameter estimates:

intercept 0.4388 (0.4015–0.4763), β AF 0.0010 (0.0007–0.0013), β AS −0.0002 (−0.0005 to 0.0000), β DP 0.0023 (0.0020–0.0027), β PL 0.0019 (0.0017–0.0022), β TS 0.0004 (−0.0001 to 0.0008).

Using the posterior distribution for the coefficients of the final linear regression mapping algorithm, we calculated the EQ-5D based on the scores for the five SAQ domains for each included study. To fully incorporate uncertainty in the estimated EQ-5D utilities, we assumed that the inputted SAQ values from each paper had a normal distribution, based on the mean and standard error. We sampled from this distribution to calculate the mean and 95% credible interval of the estimated EQ-5D.

The mapping algorithm and EQ-5D estimates were calculated using WinBUGS version 1.4 (Medical Research Council, London, UK).

Results

Study selection

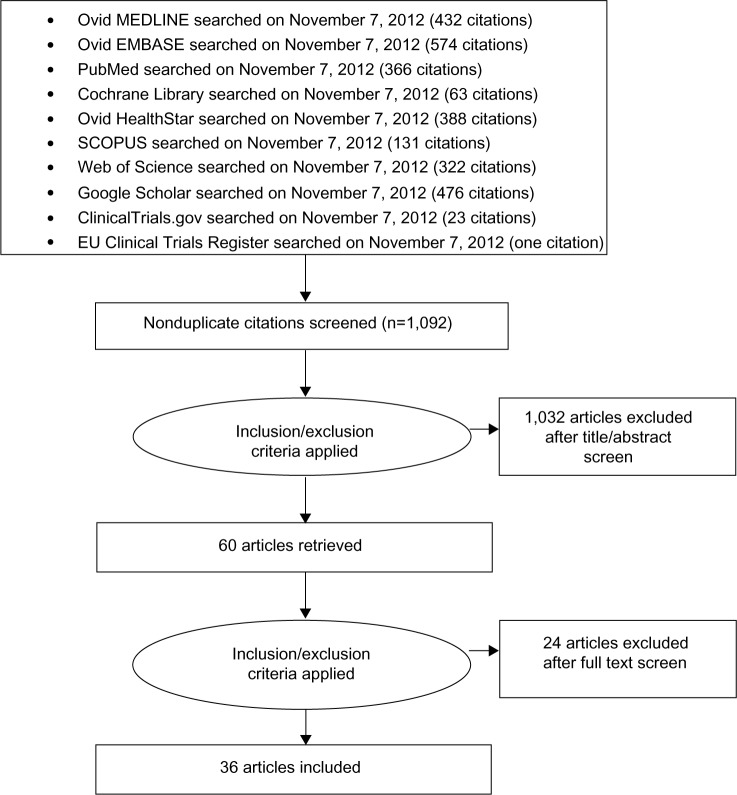

We identified 2,776 citations from various sources using our search criteria. After removing duplications, 1,092 articles were screened to identify articles in English that were potentially relevant and that reported scores and standard errors (or standard deviation and sample size, or confidence intervals, in order to calculate the standard error) for all five domains of the SAQ. Full review was done on 60 articles. We excluded 24 of these articles because they provided SAQ scores following experimental interventions, ie, neurostimulation (six articles), autologous bone marrow transplant (three articles), transmyocardial laser revascularization (six articles), herbal medicine (two articles), fibroblast growth factor (one article), granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (one article), cognitive behavioral therapy (one article), and other (four articles). A total of 36 articles met our eligibility criteria and were included in the final analysis. Figure 1 presents the flow diagram of our review process.

Figure 1.

Process of study selection.

Study characteristics

The 36 studies in our systematic review represent a wide spectrum of patients with IHD. Eight of these studies focused exclusively on patients with stable angina,12–19 and four included patients with a previous myocardial infarction.12,20–22 Four studies specifically assessed SAQ in patients with advanced IHD unsuitable for revascularization.18,23–25 These studies reported SAQ scores in patients with general angina, or specifically with severe or refractory angina. Five studies were restricted to an elderly population,23,26–29 one study was restricted to women with IHD,30 and one study reported SAQ data in diabetic patients with IHD.17 SAQ data were compared among South Asians versus Europeans with IHD in one study,31 while another study reported the SAQs of Caucasians and African Americans with IHD.20 The studies ranged from cross-sectional evaluations with no follow-up to longitudinal studies with follow-up ranging from 7 days to a mean of 6 years and 11 months.

Given our intent to form a catalog such that estimated utility scores can be easily referenced, we categorized the 36 included articles in three groups, as shown in Tables 1–3. Thirteen studies focused on general IHD patients (Table 1), four focused on patients with recent acute coronary syndrome (Table 2), and 19 assessed revascularized patients (Table 3), of which eight included only patients who underwent coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG)23,28,29,32–36 and six included only patients who had percutaneous coronary intervention.19,21,27,37–39

Table 1.

General ischemic heart disease

| Reference | Inclusion/exclusion | Intervention/Subgroup | n | Mean age, years | Gender (% male) | Time point | PL | SAQ

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AS | AF | TS | DP | EQ-5D | ||||||||

| Bainey et al31 | (I) Diagnosed with IHD. | 1. South Asians | 635 | 62.1 | 77.9 | 1 year | 75.0 (0.91) | 77.0 (1.11) | 86.0 (0.91) | 86.0 (0.75) | 71.0 (0.95) | 0.852 (0.84–0.86) |

| 2. Europeans | 18,934 | 63.5 | 74.0 | 1 year | 80.0 (0.44) | 77.0 (0.52) | 88.0 (0.38) | 89.0 (0.30) | 76.0 (0.40) | 0.877 (0.87–0.88) | ||

| Broddadottir et al30 | (I) Women with IHD who consented to participate in the study. | 1. All ages | 437 | 66.4 | 0.0 | Baseline | 56.4 (1.12) | 75.8 (1.45) | 76.7 (1.23) | 85.9 (0.78) | 59.7 (1.13) | 0.781 (0.77–0.79) |

| 2. Age 32–59 years | 133 | 52.3 | 0.0 | Baseline | 57.4 (2.02) | 72.9 (2.66) | 72.1 (2.18) | 82.0 (1.66) | 52.5 (2.06) | 0.760 (0.75–0.78) | ||

| 3. Age 60–74 years | 190 | 68.2 | 0.0 | Baseline | 60.0 (1.70) | 77.7 (2.26) | 79.0 (1.93) | 87.7 (1.10) | 62.8 (1.71) | 0.797 (0.78–0.81) | ||

| 4. Age 75–88 years | 114 | 79.6 | 0.0 | Baseline | 48.8 (2.06) | 76.6 (2.70) | 78.2 (2.28) | 87.8 (1.24) | 63.2 (2.06) | 0.776 (0.76–0.79) | ||

| Leung et al47 | (I) IHD and eligible for cardiac rehabilitation. | 1. All patients | 1,056 | 66.3 | 71.8 | 9 months | 61.7 (0.64) | 75.1 (0.91) | 86.9 (0.67) | 78.7 (0.78) | 67.3 (0.84) | 0.816 (0.81–0.83) |

| 2. No rehabilitation | 725 | 66.9 | 70.1 | 9 months | 59.0 (0.81) | 71.4 (1.14) | 84.8 (0.87) | 76.5 (0.99) | 65.6 (1.01) | 0.805 (0.79–0.82) | ||

| 3. Rehabilitation <6 months | 148 | 63.3 | 71.9 | 9 months | 68.9 (1.19) | 83.1 (2.09) | 90.9 (1.42) | 85.5 (1.56) | 72.4 (2.09) | 0.847 (0.83–0.86) | ||

| 4. Rehabilitation >6 months | 183 | 65.7 | 72.0 | 9 months | 66.7 (1.29) | 83.3 (1.81) | 91.7 (1.02) | 82.0 (1.73) | 69.7 (2.06) | 0.836 (0.82–0.85) | ||

| Ohldin et al20 | (I) Veterans, IHD: self-reported angina, history of myocardial infarction, coronary artery disease, or a coronary artery revascularization procedure on the screening questionnaire. | 1. Caucasians | 6,704 | 66.3 | 98.3 | Baseline | 50.8 (0.32) | 56.2 (0.33) | 76.5 (0.29) | 83.0 (0.25) | 63.0 (0.31) | 0.781 (0.77–0.79) |

| 2. African Americans | 1,281 | 64.0 | 98.6 | Baseline | 51.9 (0.72) | 57.6 (0.85) | 76.0 (0.69) | 77.6 (0.70) | 58.5 (0.77) | 0.769 (0.76–0.78) | ||

| Fathi et al24 | (I) Angina, symptomatic IHD, unsuitable for revascularization. (E) LVEF <30%, could not comply with follow-up, had a condition that precluded the performance of stress testing, and had compromised life expectancy. | 1. Usual therapy of lipids (target LDL <116) | 30 | 63.4 | 80.0 | Baseline | 59.0 (4.74) | 57.0 (6.20) | 64.0 (5.47) | 85.0 (2.73) | 59.0 (4.38) | 0.775 (0.74–0.81) |

| 12 weeks | 58.0 (4.92) | 64.0 (4.74) | 65.0 (5.84) | 82.0 (3.28) | 57.0 (4.56) | 0.767 (0.74–0.80) | ||||||

| 2. A ggressive lipid reduction/target LDL <77 | 30 | 63.9 | 77.0 | Baseline | 67.0 (4.56) | 64.0 (4.92) | 72.0 (5.84) | 92.0 (2.55) | 60.0 (4.92) | 0.802 (0.77–0.83) | ||

| 12 weeks | 73.0 (4.19) | 78.0 (5.29) | 80.0 (4.56) | 91.0 (1.82) | 70.0 (4.01) | 0.842 (0.81–0.87) | ||||||

| Moore et al25 | (I) Refractory angina (rejected for revascularization) and referred to refractory angina clinic. | Refractory angina program | 69 | 62.3 | 81.0 | Baseline | 25.2 (1.49) | 32.8 (2.85) | 26.9 (2.32) | 62.8 (2.80) | 31.3 (2.38) | 0.605 (0.58–0.63) |

| 1 year | 27.7 (1.73) | 43.5 (3.32) | 37.7 (2.78) | 72.0 (2.78) | 42.9 (3.17) | 0.649 (0.63–0.67) | ||||||

| Spertus et al12 | (I) Chronic, stable, symptomatic IHD, documented history of coronary disease (prior MI, coronary revascularization, or history of typical angina pectoris), taking at least 2 regular antiangina medications for control of symptoms. (E) Hospitalizations within 4 months, aortic stenosis, EF <40%, sick sinus syndrome, advanced heart block, or other significant comorbidity limiting life expectancy. |

1. Usual antianginal medications | 49 | 64.6 | NA | Baseline | 54.2 (3.61) | 57.1 (3.41) | 66.9 (3.52) | 83.6 (2.07) | 55.3 (3.14) | 0.760 (0.74–0.78) |

| 2. Long-acting diltiazem ± nitroglycerin patches ± atenolol | 51 | 65.3 | NA | Baseline | 48.9 (3.05) | 50.5 (3.01) | 56.7 (3.87) | 80.6 (2.31) | 48.7 (2.99) | 0.724 (0.70–0.75) | ||

| Beltrame et al13 | (I) Stable angina. Not required to have ongoing angina symptoms. | 2,031 | 71.0 | 64.0 | Baseline | 70.0 (0.62) | 63.0 (0.59) | 84.0 (0.51) | 90.0 (0.31) | 70.0 (0.54) | 0.843 (0.84–0.85) | |

| Makolkin and Osadchiy14 | (I) Stable angina with average of >3 angina attacks/week, 1–2 antianginal agents with hemodynamic action at stable doses at the time of inclusion for ≥3 months. (E) NYHA class ≥II, unstable angina, recent MI or stroke within 6 months, severe arrhythmia or conduction impairment. |

Trimetazidine and conventional therapy | 846 | 58.7 | 61.0 | Baseline | 50.7 (0.70) | 57.6 (0.90) | 33.3 (0.70) | 62.3 (0.70) | 36.7 (0.60) | 0.667 (0.65–0.68) |

| 8 weeks | 61.0 (0.60) | 92.5 (0.70) | 55.6 (0.80) | 77.4 (0.50) | 55.5 (0.70) | 0.751 (0.74–0.76) | ||||||

| Stone et al15 | (I) Age ≥18 years, chronic stable angina and ≥3 episodes of angina/week despite treatment with 10 mg of amlodipine. (E) NYHA class IV CHF, prior MI, unstable angina within 2 months, active acute myocarditis, pericarditis, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, uncontrolled hypertension, history of torsades de pointes, agents to prolong QTc interval, QTc interval ≥500 msec, receiving inhibitors of cytochrome P450-3A4, hepatic disease, creatinine clearance <30 mL/min, chronic illness likely to interfere with protocol compliance, taking any digitalis preparation, perhexiline, trimetazidine, beta-blockers, or calcium channel blockers other than amlodipine, proscribed antianginal medications within 4 weeks before initiation of the study drug, participation in another investigative trial within 30 days before study start. |

1. Placebo + amlodipine | 283 | 61.3 | 73.0 | Baseline | 48.9 (1.02) | 57.2 (1.05) | 40.0 (0.88) | 75.4 (0.83) | 41.5 (1.05) | 0.687 (0.67–0.70) |

| 2. Ranolazine + amlodipine | 281 | 62.0 | 72.0 | Baseline | 49.2 (1.03) | 54.7 (1.07) | 40.6 (0.78) | 74.6 (0.85) | 41.6 (1.02) | 0.688 (0.68–0.70) | ||

| Maxwell et al16 | (I) CCS II and III stable angina and ≥1 mm ST depression during treadmill exercise testing before achieving 14.5 Mets. (E) Unstable angina, MI, major surgery or angioplasty within the past 3 months, symptomatic HF, impaired renal or hepatic function, or any other systemic illness, congenital heart disease, valvular heart disease, atrial fibrillation, uncontrolled hypertension, type 1 diabetes, diseases other than IHD that would interfere with treadmill testing. |

Dietary management (2 L-arginine-enriched nutrient bars/day) | 36 | 65.9 | 77.8 | Baseline | 60.0 (2.33) | 54.0 (2.66) | 64.0 (3.50) | 70.0 (3.16) | 53.0 (3.33) | 0.758 (0.74–0.78) |

| 1. 2 weeks of dietary management | 64.0 (2.50) | 67.0 (3.66) | 67.0 (3.16) | 77.0 (2.50) | 61.0 (2.66) | 0.787 (0.77–0.81) | ||||||

| 2. 2 weeks of placebo | 60.0 (3.50) | 60.0 (3.66) | 66.0 (4.00) | 70.0 (3.83) | 56.0 (3.83) | 0.766 (0.74–0.79) | ||||||

| Deaton et al17 | (I) Stable, symptomatic IHD and coronary anatomy suitable for PCI. | 1. Diabetic | 320 | 62.0 | 84.0 | Baseline | 60.0 (1.48) | 49.0 (1.84) | 64.0 (1.56) | 83.0 (1.17) | 47.0 (1.45) | 0.750 (0.74–0.76) |

| 2. Nondiabetic | 693 | 61.0 | 85.0 | Baseline | 65.0 (1.02) | 51.0 (1.29) | 66.0 (1.02) | 85.0 (0.75) | 49.0 (0.98) | 0.767 (0.76–0.78) | ||

| de Jong-Watt et al54 | (I) Elective, first time coronary angiogram, planned angiography date 3–8 weeks from the time of referral, understand written or spoken English. (E) Previous coronary angiography, CABG surgery, PCI, or other cardiac procedures such as valve surgery, awaiting coronary angiography in hospital. |

Coronary angiogram | 42 | 64.6 | 67.5 | Baseline | 60.0 (4.29) | 46.3 (3.95) | 57.5 (4.67) | 83.1 (2.55) | 47.7 (3.63) | 0.746 (0.72–0.77) |

| 1 week pre-angiography | 57.7 (4.29) | 48.8 (3.99) | 54.3 (4.58) | 79.4 (2.75) | 42.3 (3.36) | 0.724 (0.70–0.75) | ||||||

Note: SAQ values include standard error; EQ-5D values include 95% confidence intervals.

Abbreviations: I, inclusion criteria; E, exclusion criteria; EF, ejection fraction; IHD, ischemic heart disease; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; MI, myocardial infarction; NYHA class, New York Heart Association classification; CHF, congestive heart failure; Mets, metabolic equivalents; HF, heart failure; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; CABG, coronary artery bypass graft; CCS, Canadian Cardiovascular Society; NA, not available; SAQ, Seattle Angina Questionnaire; PL, physical limitation; TS, treatment satisfaction; AF, angina frequency; AS, angina stability; DP, disease perception; EQ-5D, European Quality of Life-5 Dimensions; QTc, corrected QT.

Table 3.

Revascularization

| Reference | Inclusion/Exclusion | Intervention/Subgroup | n | Mean age | Gender (% male) | Time point | PL | AS | AF | TS | DP | EQ-5D |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zhang et al48 | (I) Multivessel IHD, revascularization was clinically indicated and appropriate. (E) Previous revascularization, thoracotomy, intervention for pathology of the valves, great vessels, or aorta. |

1. PCI | 488 | 61.0 | 80.0 | Baseline | 56.6 (1.02) | 47.4 (1.45) | 55.8 (1.26) | 86.7 (0.65) | 39.5 (0.90) | 0.720 (0.71–0.73) |

| 2. CABG | 500 | 62.0 | 78.0 | Baseline | 54.3 (0.98) | 45.0 (1.41) | 53.8 (1.25) | 86.2 (0.67) | 37.0 (0.91) | 0.708 (0.70–0.72) | ||

| Andréll et al18 | (I) Refractory and severe stable angina (CCS class III–IV) despite optimal conventional pharmacological therapy. | 1. Refractory angina | 139 | 70.0 | 73.0 | Baseline | 51.9 (2.16) | 50.3 (2.83) | 48.4 (3.09) | 66.9 (2.65) | 46 (2.63) | 0.710 (0.69–0.73) |

| 1 year | 55.8 (2.39) | 59.4 (3.77) | 60.7 (4.45) | 72.7 (2.76) | 53.4 (3.09) | 0.747 (0.73–0.77) | ||||||

| 2. Stable angina and revascularization | 139 | 72.0 | 73.0 | 1 year | 66 (3.43) | 71.7 (4.60) | 80.9 (4.11) | 78.5 (3.51) | 64.4 (4.21) | 0.813 (0.79–0.84) | ||

| Kim et al49 | (I) Chest pain at rest, documented electrocardiographic or arteriographic evidence of IHD. | 1. Early interventional strategy – maximal medical therapy and early coronary arteriography with possible myocardial revascularization. | 895 | 63.0 | 61.0 | 4 months | 75.4 (0.90) | 70.3 (1.00) | 80.2 (0.90) | 90.1 (0.50) | 72.1 (0.90) | 0.853 (0.84–0.86) |

| 1 year | 76.9 (1.00) | 67.7 (1.00) | 82.4 (0.90) | 91.2 (0.50) | 75.9 (0.90) | 0.868 (0.86–0.88) | ||||||

| 2. Conservative strategy – maximal medical therapy and ischemia – or symptom-provoked angiography and revascularization. | 915 | 62.0 | 64.0 | 4 months | 69.8 (0.90) | 63.9 (1.00) | 72.6 (0.90) | 86.3 (0.50) | 64.4 (0.80) | 0.816 (0.81–0.82) | ||

| 1 year | 73.3 (1.00) | 63.7 (1.00) | 78.0 (0.90) | 88.6 (0.50) | 71.2 (0.90) | 0.845 (0.84–0.85) | ||||||

| Hofer et al50 | (I) Patients with angina symptoms referred for angiographic screening of IHD. Following angiogram treatment decision (CABG, PCI, or medical management) was made as per clinical indication. | 1. All patients | 158 | 64.5 | 67.7 | Baseline | 61.6 (2.99) | 53.9 (2.68) | 45.0 (1.92) | 84.7 (1.35) | 48.9 (2.08) | 0.738 (0.72–0.76) |

| 1 year | 63.7 (2.13) | 68.4 (2.44) | 72.7 (2.18) | 82.5 (0.46) | 64.7 (2.16) | 0.803 (0.79–0.82) | ||||||

| 2. CCS class I | 22 | NA | NA | Baseline | 64.9 (9.45) | 57.1 (11.19) | 40.0 (10.41) | 89.6 (3.85) | 51.9 (9.86) | 0.747 (0.68–0.81) | ||

| 3. CCS class II | 20 | NA | NA | Baseline | 67.9 (6.48) | 46.4 (10.15) | 54.2 (8.51) | 89.5 (3.48) | 53.2 (7.44) | 0.774 (0.73–0.82) | ||

| 4. CCS class III | 62 | NA | NA | Baseline | 61.5 (3.90) | 61.1 (4.71) | 44.9 (4.27) | 85.0 (2.34) | 55.3 (3.77) | 0.751 (0.72–0.78) | ||

| 5. CCS class IV | 54 | NA | NA | Baseline | 60.5 (4.47) | 54.7 (4.66) | 45.1 (3.72) | 84.8 (2.52) | 41.7 (3.61) | 0.719 (0.69–0.75) | ||

| Graham et al26 | (I) IHD. (E) Undergoing investigation for valvular heart disease, without IHD on angiography, no consent for follow-up. |

1. Age <70 years: | ||||||||||

| A. Medical therapy | 3,488 | 59.2 (median) | 68.9 | 1 year | 72.8 (0.18) | 75.3 (0.07) | 84.1 (0.10) | 84.4 (0.05) | 71.1 (0.07) | 0.846 (0.84–0.85) | ||

| 3 years | 73.5 (0.18) | 74.9 (0.07) | 84.6 (0.07) | 84.8 (0.05) | 71.6 (0.07) | 0.849 (0.84–0.86) | ||||||

| B. CABG | 1,697 | 61.6 (median) | 83.9 | 1 year | 74.2 (0.26) | 78.6 (0.10) | 86.2 (0.13) | 86.9 (0.05) | 73.3 (0.10) | 0.856 (0.85–0.86) | ||

| 3 years | 74.7 (0.28) | 78.1 (0.10) | 86.6 (0.13) | 87.1 (0.07) | 74.0 (0.10) | 0.859 (0.85–0.87) | ||||||

| C. PCI | 2,698 | 59.1 (median) | 78.4 | 1 year | 74.9 (0.20) | 76.7 (0.07) | 85.4 (0.10) | 85.5 (0.05) | 72.5 (0.07) | 0.855 (0.85–0.86) | ||

| 3 years | 75.5 (0.18) | 76.2 (0.70) | 85.8 (0.07) | 85.9 (0.05) | 73.0 (0.07) | 0.858 (0.85–0.86) | ||||||

| 2. Age 70–79 years: | ||||||||||||

| A. Medical therapy | 1,302 | 73.9 (median) | 62.7 | 1 year | 62.1 (0.36) | 77.0 (0.15) | 83.0 (0.15) | 86.3 (0.07) | 74.9 (0.15) | 0.833 (0.82–0.84) | ||

| 3 years | 62.2 (0.41) | 76.7 (0.13) | 83.6 (0.15) | 86.6 (0.07) | 75.1 (0.15) | 0.835 (0.83–0.84) | ||||||

| B. CABG | 819 | 73.6 (median) | 77.2 | 1 year | 63.3 (0.46) | 80.5 (0.18) | 85.5 (0.52) | 88.6 (0.10) | 77.3 (0.18) | 0.844 (0.84–0.85) | ||

| 3 years | 62.9 (0.49) | 80.0 (0.18) | 85.9 (0.20) | 88.9 (0.10) | 77.4 (0.18) | 0.844 (0.84–0.85) | ||||||

| C. PCI | 819 | 73.9 (median) | 68.1 | 1 year | 63.2 (0.44) | 78.2 (0.18) | 84.0 (0.20) | 87.1 (0.10) | 75.8 (0.15) | 0.839 (0.83–0.85) | ||

| 3 years | 63.1 (0.46) | 77.8 (0.15) | 84.5 (0.20) | 87.4 (0.10) | 76.0 (0.18) | 0.840 (0.83–0.85) | ||||||

| 3. Age ≥80 years: | ||||||||||||

| A. Medical therapy | 220 | 82.4 (median) | 65.5 | 1 year | 51.9 (1.01) | 75.0 (0.33) | 79.9 (0.41) | 87.9 (0.20) | 73.5 (0.36) | 0.808 (0.80–0.82) | ||

| 3 years | 53.8 (1.27) | 76.8 (0.39) | 81.2 (0.44) | 88.3 (0.23) | 74.2 (0.39) | 0.815 (0.80–0.83) | ||||||

| B. CABG | 82 | 81.8 (median) | 74.4 | 1 year | 53.7 (1.56) | 78.1 (0.54) | 82.2 (0.62) | 89.6 (0.31) | 75.3 (0.54) | 0.818 (0.81–0.83) | ||

| 3 years | 54.2 (1.69) | 80.3 (0.52) | 83.8 (0.62) | 90.1 (0.33) | 76.2 (0.59) | 0.823 (0.81–0.83) | ||||||

| C. PC I | 137 | 82.1 (median) | 56.2 | 1 year | 51.9 (1.06) | 74.7 (0.41) | 79.3 (0.46) | 88.0 (0.23) | 72.9 (0.44) | 0.806 (0.80–0.82) | ||

| 3 years | 53.3 (1.25) | 76.9 (0.41) | 81.0 (0.46) | 88.7 (0.23) | 73.9 (0.44) | 0.813 (0.80–0.82) | ||||||

| Neil et al21 | (I) Age 21–81 years, with stable or unstable angina and a positive functional study for ischemia or undergoing angioplasty after a recent MI with target lesions that were potentially treatable by balloon angioplasty or a stent. | 1. Primary stent | 230 | 61.0 (median) | 75.0 | 6 months | 84.0 (1.51) | 82.0 (1.84) | 90.0 (1.18) | 88.0 (1.18) | 77.0 (1.45) | 0.887 (0.88–0.90) |

| 2. Optimal PTCA/provisional stent | 249 | 60.0 (median) | 72.0 | 6 months | 86.0 (1.33) | 83.0 (1.58) | 90.0 (1.07) | 91.0 (0.82) | 77.0 (1.33) | 0.892 (0.88–0.90) | ||

| de Quadros et al37 | (I) IHD. (E) Unsuccessful procedures (a residual stenosis >30% or TIMI flow 0/1 after stenting, or in-hospital major adverse cardiovascular events (death, MI, or urgent revascularization), severe cardiac disease other than IHD, ejection fraction <40%, severe neurologic disease, neoplasia, pregnancy, periprocedural hemodynamic instability, patient refusal. |

PCI | 110 | 62.8 | 68.0 | Baseline | 59.0 (1.71) | 30.0 (2.47) | 56.0 (2.38) | 80.0 (2.09) | 30.0 (2.09) | 0.704 (0.69–0.72) |

| 6 months | 79.0 (1.04) | 81.0 (2.66) | 86.0 (2.09) | 91.0 (1.33) | 64.0 (2.38) | 0.845 (0.83–0.86) | ||||||

| 1 year | 80.0 (1.00) | 90.0 (2.61) | 93.0 (1.30) | 94.0 (0.90) | 83.0 (2.21) | 0.897 (0.88–0.91) | ||||||

| Wong and Chair38 | (I) Chinese, ≥21 years old, no mental disorder, no prior PCI, understand and speak Cantonese, no severe medical illness. | PCI | 65 | 66.0 | 75.4 | Baseline | 67.6 (2.30) | 62.5 (3.62) | 74.2 (3.34) | 75.5 (1.51) | 55.8 (2.93) | 0.790 (0.77–0.81) |

| 1 month | 74.2 (3.24) | 65.5 (2.80) | 91.5 (0.76) | 85.6 (1.91) | 77.1 (2.75) | 0.873 (0.85–0.89) | ||||||

| Weintraub et al39 | (I) >70% stenosis in at least one major epicardial coronary artery with objective evidence of myocardial ischemia or >80% stenosis in at least one coronary artery and classic angina without provocative testing. | 1. PCI + OMT | 1,149 | 61.5 | 85.0 | Baseline | 66.0 (0.81) | 54.0 (1.06) | 68.0 (0.83) | 88.0 (0.48) | 51.0 (0.80) | 0.776 (0.77–0.79) |

| 1 month | 73.0 (0.82) | 81.0 (0.88) | 82.0 (0.77) | 92.0 (0.40) | 68.0 (0.81) | 0.839 (0.83–0.85) | ||||||

| 3 months | 76 (0.82) | 77 (0.95) | 85 (0.75) | 92 (0.41) | 73 (0.75) | 0.869 (0.86–0.87) | ||||||

| 6 months | 77.0 (0.77) | 76.0 (0.94) | 87.0 (0.66) | 92.0 (0.43) | 75.0 (0.73) | 0.869 (0.86–0.88) | ||||||

| 1 year | 75.0 (0.82) | 74.0 (0.92) | 87.0 (0.64) | 92.0 (0.40) | 76.0 (0.71) | 0.868 (0.86–0.88) | ||||||

| 2 years | 74 (0.88) | 73 (0.99) | 89 (0.65) | 92 (0.47) | 77 (0.80) | 0.871 (0.86–0.88) | ||||||

| 3 years | 74.0 (1.00) | 72.0 (1.16) | 89.0 (0.74) | 92.0 (0.49) | 79.0 (0.82) | 0.876 (0.87–0.88) | ||||||

| 2. OMT | 1,138 | 61.8 | 85.0 | Baseline | 66.0 (0.81) | 53.0 (1.02) | 69.0 (0.83) | 86.0 (0.51) | 51.0 (0.80) | 0.777 (0.77–0.79) | ||

| 1 month | 70.0 (0.82) | 73.0 (0.94) | 76.0 (0.80) | 88.0 (0.50) | 62.0 (0.80) | 0.813 (0.81–0.82) | ||||||

| 3 months | 72 (0.79) | 73.0 (0.92) | 80.0 (0.78) | 90.0 (0.47) | 68 (0.78) | 0.836 (0.83–0.84) | ||||||

| 6 months | 72.0 (0.83) | 73.0 (0.97) | 83.0 (0.75) | 90.0 (0.48) | 70.0 (0.75) | 0.844 (0.84–0.85) | ||||||

| 1 year | 73.0 (0.84) | 70.0 (0.98) | 84.0 (0.72) | 90.0 (0.48) | 73.0 (0.76) | 0.854 (0.85–0.86) | ||||||

| 2 years | 72 (0.89) | 69 (1.00) | 86.0 (0.70) | 92.0 (0.48) | 76 (0.81) | 0.862 (0.85–0.87) | ||||||

| 3 years | 74.0 (0.99) | 70.0 (1.16) | 88.0 (0.74) | 92.0 (0.45) | 77.0 (0.82) | 0.870 (0.86–0.88) | ||||||

| Agarwal et al27 | (I) Age ≥80 years, undergoing 1 or 2 vessel PCI. | PCI | 74 | 82.5 | 68.0 | Baseline | 24.4 (3.82) | 50.0 (6.61) | 45.8 (6.51) | 74.3 (3.85) | 38.8 (4.97) | 0.640 (0.61–0.67) |

| 6 months | 42.3 (2.55) | 72.4 (3.54) | 76.5 (3.67) | 83.7 (1.77) | 66.7 (3.04) | 0.769 (0.75–0.79) | ||||||

| 1 year | 41.4 (2.68) | 66.3 (4.01) | 73.5 (4.11) | 83.7 (2.08) | 62.3 (3.30) | 0.756 (0.73–0.78) | ||||||

| Lowe et al19 | (I) Severe stable angina (CCS class III or IV) despite maximum tolerated doses of at least two antianginal drugs, a left-ventricular ejection fraction of ≥30%, and reversible perfusion defects on the thallium stress test. | PCI | 11 | 59.0 (median) | 82.0 | Baseline | 38.0 (3.01) | 42.0 (6.03) | 40.0 (6.93) | 63.0 (6.33) | 21.0 (3.91) | 0.616 (0.59–0.65) |

| Pre-PCI | 37.0 (4.52) | 43.0 (8.74) | 49.0 (6.33) | 76.0 (6.33) | 38.0 (8.14) | 0.668 (0.62–0.71) | ||||||

| Post PCI | 36.0 (4.82) | 60.0 (9.64) | 61.0 (8.74) | 80.0 (6.33) | 45.0 (8.44) | 0.692 (0.64–0.74) | ||||||

| Ascione et al32 | (I) Conventional or off-pump CABG. (E) LVEF <30%, recent MI within 1 month (trial 1 of 2 only), history of supraventricular arrhythmia, previous CABG, renal or respiratory impairment, previous stroke, transient ischemic attack, coagulopathy, coronary disease in the branches of the circumflex artery distal to the first obtuse marginal branch (trial 1 of 2 only). |

1. Conventional CABG | 159 | 61.4 | 81.1 | 2–4 years | 75.2 (2.03) | 69.6 (2.66) | 86.8 (1.83) | 88.1 (1.72) | 74.8 (2.01) | 0.865 (0.85–0.88) |

| 2. Off-pump CABG | 169 | 63.1 | 83.4 | 2–4 years | 74.7 (1.88) | 66.3 (2.81) | 85.1 (1.79) | 88.6 (1.28) | 74.4 (1.79) | 0.862 (0.85–0.88) | ||

| Angelini et al33 | (I) Conventional or off-pump CABG. (E) LVEF <30%, recent MI within 1 month (trial 1 of 2 only), history of supraventricular arrhythmia, previous CABG, renal or respiratory impairment, previous stroke, transient ischemic attack, coagulopathy, coronary disease in the branches of the circumflex artery distal to the first obtuse marginal branch (trial 1 of 2 only). |

1. Conventional CABG | 149 | 60.9 | 86.6 | 6 years, 11 months (mean) | 72.4 (2.21) | 45.6 (3.77) | 88.8 (1.90) | 89.2 (1.96) | 74.0 (2.37) | 0.866 (0.85–0.88) |

| 2. Off-pump CABG | 150 | 62.1 | 84.7 | 6 years, 11 months (mean) | 75.0 (2.18) | 46.5 (3.67) | 89.6 (1.67) | 91.5 (1.55) | 77.0 (2.15) | 0.879 (0.86–0.90) | ||

| Karolak et al34 | (I) Conventional or off-pump CABG. (E) Reoperation, emergency CABG, concomitant major cardiac procedures, and EF <30%. |

1. Conventional CABG | 150 | 63.7 | 80.0 | 1 year | 80.0 (1.06) | 86.0 (1.95) | 91.0 (1.55) | 79.0 (1.46) | 81.0 (1.87) | 0.886 (0.87–0.90) |

| 2. Off-pump CABG | 149 | 62.2 | 81.2 | 1 year | 78.0 (1.88) | 86.0 (1.88) | 92.0 (1.14) | 79.0 (1.63) | 81.0 (1.72) | 0.883 (0.87–0.90) | ||

| Chaudhury et al35 | (I) Admitted to hospital for CABG, consented to participate in the study. | CABG | 30 | 60.0 | 90.0 | Baseline | 71.6 (1.44) | 9.8 (2.31) | 9.9 (1.62) | 37.8 (1.11) | 22.6 (0.89) | 0.653 (0.63–0.68) |

| 1 week | 53.1 (2.66) | 8.3 (2.20) | 5.8 (1.77) | 59.4 (0.76) | 36.1 (0.94) | 0.653 (0.63–0.68) | ||||||

| Wagner et al36 | (I) Veterans: non-emergent first time CABG surgery. (E) Single-vessel bypass with the internal mammary artery, concerns about arm functioning, creatinine level requiring hemodialysis or a level higher than 2.0 mg/dL, cardiogenic shock, allergic reactions to contrast material, robotic surgery, concomitant valve surgery,* concomitant Dor or Maze procedure,** no suitable radial target, participation in other research studies involving an intervention. |

1. Saphenous vein CABG | 367 | 62.0 | 99.0 | Baseline | 71.9 (0.99) | 37.9 (1.12) | 65.1 (1.15) | 91.2 (0.54) | 50.4 (1.02) | 0.788 (0.78–0.80) |

| 1 year | 86.1 (0.82) | 51.8 (0.64) | 92.5 (0.65) | 94.1 (0.54) | 83.3 (0.84) | 0.918 (0.91–0.93) | ||||||

| 2. Radial artery CABG | 366 | 61.0 | 99.0 | Baseline | 69.5 (1.05) | 37.0 (1.08) | 64.7 (1.16) | 92.0 (0.51) | 50.1 (1.07) | 0.783 (0.77–0.80) | ||

| 1 year | 83.3 (0.95) | 52.7 (0.67) | 91.7 (0.70) | 93.8 (0.57) | 83.6 (0.86) | 0.912 (0.90–0.92) | ||||||

| MacDonald et al28 | (I) Age ≥75 years, candidates for CABG. | CABG | 100 | 78.8 | 66.0 | Baseline | 40.2 (2.12) | 51.8 (3.41) | 53.8 (2.97) | 92.5 (1.49) | 40.3 (1.81) | 0.689 (0.67–0.71) |

| 3 months | 63.8 (2.44) | 92.7 (1.69) | 93.4 (1.45) | 93.3 (1.39) | 82.3 (2.05) | 0.863 (0.85–0.88) | ||||||

| Gelsomino et al23 | (I) Age ≥70 years, undergoing cardiac surgical procedures. | 1. Age ≥80 years | 1,142 | 83.0 | 49.0 | Baseline | 42.0 (4.42) | 32.0 (7.03) | 42.0 (8.59) | 52.0 (4.16) | 29.0 (3.12) | 0.643 (0.61–0.68) |

| 5 years, 9 months (median) | 77.0 (7.55) | 67.0 (6.51) | 79.0 (6.25) | 76.0 (5.20) | 76.0 (3.64) | 0.859 (0.82–0.90) | ||||||

| 2. Age 70–79 years | 1,213 | 72.0 | 68.9 | Baseline | 44.0 (5.72) | 35.0 (7.03) | 39.0 (7.03) | 51.0 (4.16) | 34.0 (3.12) | 0.655 (0.62–0.69) | ||

| 5 years, 9 months (median) | 83.0 (9.63) | 94.0 (4.42) | 92.0 (5.46) | 88.0 (5.98) | 93.0 (4.68) | 0.918 (0.87–0.96) | ||||||

| Fruitman et al29 | (I) Age ≥80 years, accepted for cardiac surgical procedures at a peer review conference. (E) Preoperative neurological diseases. |

CABG | 127 | 83.0 | 49.6 | 1 year, 4 months (mean) | 86.8 (2.84) | 94.4 (1.86) | 92.3 (2.14) | 89.3 (1.92) | 91.9 (1.84) | 0.928 (0.91–0.95) |

Notes: SAQ values include standard error, EQ-5D values include 95% confidence intervals.

Valve surgery is aortic or mitral valve replacement/repair.

Dor or Maze is for treatment of atrial fibrillation.

Abbreviations: I, inclusion criteria; E, exclusion criteria; IHD, ischemic heart disease; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; MI, myocardial infarction; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; CABG, coronary artery bypass graft; CCS, Canadian Cardiovascular Society; PTCA, percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty; TIMI, Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction; OMT, optimal medical therapy; SAQ, Seattle Angina Questionnaire; PL, physical limitation; TS, treatment satisfaction; AF, angina frequency; AS, angina stability; DP, disease perception; EQ-5D, European Quality of Life-5 Dimensions.

Table 2.

Acute coronary syndrome, MI, and acute chest pain

| Reference | Inclusion/exclusion | Intervention/Subgroup | n | Mean age, years | Gender (% male) | Time point | PL | AS | AF | TS | DP | EQ-5D |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arnold et al51 | (I) Myocardial ischemia at rest for ≥10 minutes presenting within the previous 48 hours, and elevated biomarkers of myocardial necrosis, ST depression of at least 0.1 mV, diabetes mellitus or a TIMI risk score of ≥3. (E) Persistent ST segment elevation, successful revascularization before randomization, and ECG abnormalities that interfere with interpretation of ischemia. |

1. Prior history of angina | 3,565 | 66.0 (median) | 62.6 | |||||||

| A. Ranolazine | Baseline | 54.5 (0.57) | 30.8 (0.70) | 52.1 (0.63) | 77.5 (0.43) | 37.7 (0.45) | 0.708 (0.70–0.72) | |||||

| B. Placebo | Baseline | 54.1 (0.57) | 30.6 (0.72) | 51.2 (0.65) | 77.5 (0.44) | 37.5 (0.47) | 0.706 (0.69–0.72) | |||||

| 2. No prior history of angina | 2,995 | 62.0 (median) | 68.0 | |||||||||

| A. Ranolazine | Baseline | 73.0 (0.65) | 39.2 (0.70) | 76.4 (0.64) | 85.9 (0.40) | 47.6 (0.54) | 0.793 (0.78–0.80) | |||||

| B. Placebo | Baseline | 73.5 (0.65) | 40.2 (0.74) | 76.7 (0.62) | 86.5 (0.41) | 48.4 (0.54) | 0.796 (0.79–0.81) | |||||

| Arnold et al52 | (I) ≥18 years, symptoms of myocardial ischemia at rest lasting at least 10 minutes and present within the previous 48 hours, and had at least one of: elevated biomarkers of myocardial necrosis, ST depression of ≥0.1 mV, diabetes mellitus or a TIMI risk score of ≥3. (E) Persistent ST segment elevation, revascularization before randomization, and ECG abnormalities that would interfere with interpretation of Holter monitoring for ischemia. |

Rose Dyspnea Scale: 0 | 972 | 59.5 | 75.3 | 1 month | 97.6 (0.31) | 54.7 (0.50) | 95.4 (0.40) | 92.5 (0.37) | 83.0 (0.54) | 0.942 (0.93–0.95) |

| Rose Dyspnea Scale: 1 | 318 | 59.7 | 67.3 | 1 month | 93.1 (0.84) | 56.9 (1.03) | 92.7 (0.82) | 90.0 (0.71) | 76.8 (1.11) | 0.914 (0.90–0.93) | ||

| Rose Dyspnea Scale: 2 | 205 | 60.9 | 61.5 | 1 month | 89.1 (1.36) | 55.6 (1.45) | 88.0 (1.32) | 90.8 (0.87) | 71.0 (1.57) | 0.889 (0.88–0.90) | ||

| Rose Dyspnea Scale: 3 | 170 | 60.7 | 57.6 | 1 month | 80.0 (1.85) | 57.9 (1.77) | 86.0 (1.53) | 86.9 (1.18) | 65.8 (2.06) | 0.855 (0.84–0.87) | ||

| Rose Dyspnea Scale: 4 | 170 | 60.6 | 64.1 | 1 month | 60.5 (2.35) | 56.1 (1.83) | 81.1 (1.90) | 85.7 (1.18) | 58.4 (2.23) | 0.795 (0.78–0.81) | ||

| Pettersen et al22 | (I) Discharge diagnosis of acute MI. | 408 | 65.5 | 71.0 | 2–3 years | 73.0 (1.23) | 68.0 (1.29) | 86.0 (1.10) | 81.0 (1.09) | 72.0 (1.15) | 0.851 (0.84–0.86) | |

| Asadi-Lari et al53 | (I) Admitted to acute cardiac unit with chest pain. | 242 | 69.7 | 59.0 | ||||||||

| 1. Women | Baseline | 49.3 (2.79) | 48.1 (1.92) | 73.9 (3.00) | 84.2 (2.11) | 57.7 (2.70) | 0.765 (0.75–0.79) | |||||

| 2. Men | Baseline | 55.1 (2.45) | 53.2 (1.61) | 75.6 (2.34) | 87.6 (1.46) | 63.1 (2.13) | 0.791 (0.77–0.81) |

Notes: SAQ values include standard error; EQ-5D values include 95% confidence intervals.

Abbreviations: I, inclusion criteria; E, exclusion criteria; TIMI, Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction; ECG, electrocardiogram; SAQ, Seattle Angina Questionnaire; PL, physical limitation; TS, treatment satisfaction; AF, angina frequency; AS, angina stability; DP, disease perception; EQ-5D, European Quality of Life-5 Dimensions.

Predicted EQ-5D

The SAQ scores from the original publications and the calculated EQ-5D scores are shown in Tables 1–3. The estimated baseline EQ-5D scores for the general IHD patients were in the range of 0.605–0.843, increasing to 0.649–0.877 post follow-up (Table 1). The baseline range was 0.706–0.796 for the studies focused on patients with a recent acute coronary syndrome, increasing to 0.795–0.942 post follow-up (Table 2). The revascularization studies had EQ-5D scores in the range of 0.616–0.790 at baseline, increasing to 0.653–0.928 after treatment (Table 3). Studies that included only CABG as the revascularization modality had an EQ-5D score range that increased from 0.643–0.788 at baseline to 0.653–0.928 after CABG; the studies that focused only on percutaneous coronary intervention had scores that increased from 0.616–0.790 at baseline to 0.668–0.897 after treatment.

Discussion

In this report, we have provided a comprehensive catalog of predicted EQ-5D utility scores for patients with IHD. We first performed a systematic review of the literature to identify studies that reported SAQ scores and then applied our previously validated mapping algorithm to convert SAQ scores to EQ-5D scores. The studies included in our systematic review represent a broad spectrum of IHD patients and assessed quality of life at baseline and/or following a broad range of nonpharmacologic, medical, or surgical interventions.

Patient-reported health status has gained an increasingly important role in the decision-making process for health resource allocation.40 Patient health status independently predicts mortality, cardiovascular events, hospitalizations, and costs of care in cardiovascular illnesses.41–43 Current methodologic guidelines emphasize the importance of preference-based measures in comparative effectiveness studies of health technologies. For example, the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence suggests that EQ-5D is the preferred method in quantifying the health outcome of various interventions.44 However, in many circumstances, preference-based instruments have not been included in cardiovascular studies. In the absence of such information, mapping techniques such as that applied in the current study can be used to estimate utility weights from available descriptive quality of life data.45

Dyer et al recently published a summary of available EQ-5D scores from the entire spectrum of cardiovascular diseases,46 and were able to identify 18 studies in IHD. They observed significant heterogeneity in the reported EQ-5D scores across these studies, in the range of 0.45–0.88. We believe our study is an important addition to this early work, by providing utility scores on additional studies in IHD, covering a wide spectrum of revascularization modalities and patient populations. Similar to the previous work by Dyer et al, we found heterogeneity between studies. This heterogeneity in utility weights between studies underscores the importance of a catalog such as ours. When researchers are developing economic models, it is essential that the utility weights inputted are reflective of the population being studied. Our catalog provides detailed information on the population being evaluated, as well as interventions, which will provide researchers with the information needed such that they can utilize the most appropriate utility weights when developing economic models.

Our mapping algorithm was designed to estimate EQ-5D scores using the scores and standard errors in all five domains of the SAQ.9 An important limitation is that we had to exclude studies that did not publish scores on all five domains of the SAQ. However, our final catalog included estimated EQ-5D scores across a wide range of baseline patient demographics, disease severity, and various treatment interventions. A weakness of our systematic review is that we failed to capture studies that did not use the name of the SAQ scale in the text of the paper and failed to cite the source of the questionnaire.

In conclusion, in the current era of budgetary constraints, cost-effectiveness analysis has become increasingly important in decision-making for health resource allocation. In the absence of directly measured individual patient preference-based data, our catalog of estimated EQ-5D scores can be useful in IHD-related economic evaluations.

Supplementary material

The following method describes the search strategy used to collect the references analyzed in this study. This strategy had three primary facets, outlined below.

Identification of materials in the primary databases of medical literature that referenced the Seattle Angina Questionnaire. These databases were MEDLINE (Ovid), EMBASE (Elsevier), OVID HealthStar, MEDLINE (PubMed), and the Cochrane Library (Wiley).

Use of the citation mapping tools Google Scholar (Google), Scopus (Elsevier), and Web of Science (Thomson Reuters), to find all available references to the paper in which Seattle Angina Questionnaire was first described by John Spertus et al in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology in 1995. The search strategy was to locate the original article by Spertus et al and export the references that the tool identified as having cited that article.

Use of the major clinical trial registries to determine the studies that used the SAQ as an outcome measure. These registries have simple search functions, and so our search terms were “Seattle Angina Questionnaire” or “SAQ”. The strategy then underwent peer review by a librarian experienced in the creation and review of systematic search strategies.

Search strategy

The following search strategy was applied to MEDLINE (Ovid), HealthStar (Ovid), and EMBASE (Ovid). It was adapted for use in PubMed by updating the syntax to match that offered in the PubMed search tool. When searching the Cochrane Library, only the words “Seattle Angina Questionnaire” were used. Databases were searched from inception until 2013.

(Development and evaluation of the Seattle Angina Questionnaire: a new functional status measure for coronary artery disease).m_titl.

seattle angina questionnaire.mp.

seattle angina questionnaire.tw.

(seattle adj3 angina).af.

(angina adj3 questionnaire).af.

saq.mp.

or/1–6.

spertus ja.au.

and 8.

Acknowledgments

HCW is supported by a Distinguished Clinical Scientist Award from the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada.

Footnotes

Author contributions

HCW was involved in the conception, design, acquisition, analysis and interpretation of the data, and critically revised the manuscript. SFZ was involved in the conception and design, acquisition of data, and interpretation of the data, and drafted the manuscript. WW was involved in conception of the study, performed the systematic search, and revised the manuscript critically. MCB was involved in the acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, and revised the manuscript critically. All authors approved the final manuscript for publication and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclosure

The authors report no competing interests in this work.

References

- 1.National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence . Guide to the Methods of Technology Appraisal. London, UK: National Institute for Clinical Excellence; 2004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health . Guidelines for the Economic Evaluation of Health Technologies: Canada. 3rd ed. Ottawa, ON, Canada: Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Longworth L, Buxton M, Sculpher M, Smith D. Estimating utility data from clinical indicators for patients with stable angina. Eur J Health Econ. 2005;6(4):347–353. doi: 10.1007/s10198-005-0309-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organization . Making Choices in Health: WHO Guide to Cost-Effectiveness Analysis. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Drummond MF, Sculpher MJ, Torrance GW, O’Brien BJ, Stoddart GL. Methods for the Economic Evaluation of Health Care Programmes. 3rd ed. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Llewellyn-Thomas HA. Health state descriptions. Purposes, issues, a proposal. Med Care. 1996;34(Suppl 12):DS109–DS118. doi: 10.1097/00001648-199601001-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dolan P. Modeling valuations for EuroQol health states. Med Care. 1997;35(11):1095–1108. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199711000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Spertus JA, Winder JA, Dewhurst TA, et al. Development and evaluation of the Seattle Angina Questionnaire: a new functional status measure for coronary artery disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1995;25(2):333–341. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(94)00397-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wijeysundera HC, Tomlinson G, Norris CM, Ghali WA, Ko DT, Krahn MD. Predicting EQ-5D utility scores from the Seattle Angina Questionnaire in coronary artery disease: a mapping algorithm using a Bayesian framework. Med Decis Making. 2011;31(3):481–493. doi: 10.1177/0272989X10386800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brooks R. EuroQol: the current state of play. Health Policy. 1996;37(1):53–72. doi: 10.1016/0168-8510(96)00822-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(4):264–269. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Spertus JA, Dewhurst T, Dougherty CM, Nichol P. Testing the effectiveness of converting patients to long-acting antianginal medications: the Quality of Life in Angina Research Trial (QUART) Am Heart J. 2001;141(4):550–558. doi: 10.1067/mhj.2001.112781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Beltrame JF, Weekes AJ, Morgan C, Tavella R, Spertus JA. The prevalence of weekly angina among patients with chronic stable angina in primary care practices: the Coronary Artery Disease in General Practice (CADENCE) Study. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(16):1491–1499. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Makolkin VI, Osadchiy KK. Trimetazidine modified release in the treatment of stable angina: TRIUMPH studyTRImetazidine MR in patients with stable angina: unique metabolic PatH. Clin Drug Investig. 2004;24(12):731–738. doi: 10.2165/00044011-200424120-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stone PH, Gratsiansky NA, Blokhin A, Huang IZ, Meng L, ERICA Investigators Antianginal efficacy of ranolazine when added to treatment with amlodipine: the ERICA (Efficacy of Ranolazine in Chronic Angina) trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;48(3):566–575. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.05.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maxwell AJ, Zapien MP, Pearce GL, MacCallum G, Stone PH. Randomized trial of a medical food for the dietary management of chronic, stable angina. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;39(1):37–45. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(01)01708-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Deaton C, Kimble LP, Veledar E, et al. The synergistic effect of heart disease and diabetes on self-management, symptoms, and health status. Heart Lung. 2006;35(5):315–323. doi: 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2006.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Andrell P, Ekre O, Grip L, et al. Fatality, morbidity and quality of life in patients with refractory angina pectoris. Int J Cardiol. 2011;147(3):377–382. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2009.09.538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lowe HC, Oesterle SN, He KL, MacNeill BD, Burkhoff D. Outcomes following percutaneous coronary intervention in patients previously considered “without option”: a subgroup analysis of the PACIFIC trial. J Interv Cardiol. 2004;17(2):87–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8183.2004.00325.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ohldin A, Young B, Derleth A, et al. Ethnic differences in satisfaction and quality of life in veterans with ischemic heart disease. J Natl Med Assoc. 2004;96(6):799–808. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Neil N, Ramsey SD, Cohen DJ, et al. Resource utilization, cost, and health status impacts of coronary stent versus “optimal” percutaneous coronary angioplasty: results from the OPUS-I trial. J Interv Cardiol. 2002;15(4):249–255. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8183.2002.tb01099.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pettersen KI, Reikvam A, Stavem K. Reliability and validity of the Norwegian translation of the Seattle Angina Questionnaire following myocardial infarction. Qual Life Res. 2005;14(3):883–889. doi: 10.1007/s11136-004-0802-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gelsomino S, Lorusso R, Livi U, et al. Cost and cost-effectiveness of cardiac surgery in elderly patients. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2011;142(5):1062–1073. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fathi R, Haluska B, Short L, Marwick TH. A randomized trial of aggressive lipid reduction for improvement of myocardial ischemia, symptom status, and vascular function in patients with coronary artery disease not amenable to intervention. Am J Med. 2003;114(6):445–453. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(03)00052-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moore RK, Groves D, Bateson S, et al. Health related quality of life of patients with refractory angina before and one year after enrolment onto a refractory angina program. Eur J Pain. 2005;9(3):305–310. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2004.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Graham MM, Norris CM, Galbraith PD, Knudtson ML, Ghali WA, APPROACH Investigators Quality of life after coronary revascularization in the elderly. Eur Heart J. 2006;27(14):1690–1698. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehl038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Agarwal S, Schechter C, Zaman A. Assessment of functional status and quality of life after percutaneous coronary revascularisation in octogenarians. Age Ageing. 2009;38(6):748–751. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afp174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.MacDonald P, Stadnyk K, Cossett J, Klassen G, Johnstone D, Rockwood K. Outcomes of coronary artery bypass surgery in elderly people. Can J Cardiol. 1998;14(10):1215–1222. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fruitman DS, MacDougall CE, Ross DB. Cardiac surgery in octogenarians: can elderly patients benefit? Quality of life after cardiac surgery. Ann Thorac Surg. 1999;68(6):2129–2135. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(99)00818-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Broddadottir H, Jensen L, Norris C, Graham M. Health-related quality of life in women with coronary artery disease. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2009;8(1):18–25. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcnurse.2008.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bainey KR, Norris CM, Gupta M, et al. Altered health status and quality of life in South Asians with coronary artery disease. Am Heart J. 2011;162(3):501–506. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2011.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ascione R, Reeves BC, Taylor FC, Seehra HK, Angelini GD. Beating heart against cardioplegic arrest studies (BHACAS 1 and 2): quality of life at mid-term follow-up in two randomised controlled trials. Eur Heart J. 2004;25(9):765–770. doi: 10.1016/j.ehj.2003.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Angelini GD, Culliford L, Smith DK, et al. Effects of on- and off-pump coronary artery surgery on graft patency, survival, and health-related quality of life: long-term follow-up of 2 randomized controlled trials. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2009;137(2):295–303. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2008.09.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Karolak W, Hirsch G, Buth K, Legare JF. Medium-term outcomes of coronary artery bypass graft surgery on pump versus off pump: results from a randomized controlled trial. Am Heart J. 2007;153(4):689–695. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2007.01.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chaudhury S, Sharma S, Pawar AA, et al. Psychological correlates of outcome after coronary artery bypass graft. Med J Armed Forces India. 2006;62(3):220–223. doi: 10.1016/S0377-1237(06)80004-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wagner TH, Sethi G, Holman W, et al. Costs and quality of life associated with radial artery and saphenous vein cardiac bypass surgery: results from a Veterans Affairs multisite trial. Am J Surg. 2011;202(5):532–535. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2011.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.de Quadros AS, Lima TC, Rodrigues AP, et al. Quality of life and health status after percutaneous coronary intervention in stable angina patients: results from the real-world practice. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2011;77(7):954–960. doi: 10.1002/ccd.22746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wong MS, Chair SY. Changes in health-related quality of life following percutaneous coronary intervention: a longitudinal study. Int J Nurs Stud. 2007;44(8):1334–1342. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2006.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Weintraub WS, Spertus JA, Kolm P, et al. Effect of PCI on quality of life in patients with stable coronary disease. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(7):677–687. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa072771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rumsfeld JS, Alexander KP, Goff DC, Jr, et al. Cardiovascular health: the importance of measuring patient-reported health status: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2013;127(22):2233–2249. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e3182949a2e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mommersteeg PM, Denollet J, Spertus JA, Pedersen SS. Health status as a risk factor in cardiovascular disease: a systematic review of current evidence. Am Heart J. 2009;157(2):208–218. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2008.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Heidenreich PA, Spertus JA, Jones PG, et al. Health status identifies heart failure outpatients at risk for hospitalization or death. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;47(4):752–756. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chan PS, Soto G, Jones PG, et al. Patient health status and costs in heart failure: insights from the eplerenone post-acute myocardial infarction heart failure efficacy and survival study (EPHESUS) Circulation. 2009;119(3):398–407. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.820472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence . Briefing Paper for Methods Review Workshop on Key Issues in Utility Measurement. London, UK: National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Brazier JE, Yang Y, Tsuchiya A, Rowen DL. A review of studies mapping (or cross walking) non-preference based measures of health to generic preference-based measures. Eur J Health Econ. 2010;11(2):215–225. doi: 10.1007/s10198-009-0168-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dyer MT, Goldsmith KA, Sharples LS, Buxton MJ. A review of health utilities using the EQ-5D in studies of cardiovascular disease. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2010;8:13. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-8-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Leung YW, Grewal K, Gravely-Witte S, Suskin N, Stewart DE, Grace SL. Quality of life following participation in cardiac rehabilitation programs of longer or shorter than 6 months: does duration matter? Population Health Management. 2011;14(4):181–188. doi: 10.1089/pop.2010.0048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhang Z, Mahoney EM, Stables RH, et al. Disease-specific health status after stent-assisted percutaneous coronary intervention and coronary artery bypass surgery: one-year results from the Stent or Surgery trial. Circulation. 2003;108(14):1694–1700. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000087600.83707.FD. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kim J, Henderson RA, Pocock SJ, et al. Health-related quality of life after interventional or conservative strategy in patients with unstable angina or non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: one-year results of the third Randomized Intervention Trial of unstable Angina (RITA-3) J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;45(2):221–228. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.10.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hofer S, Benzer W, Schussler G, von Steinbuchel N, Oldridge NB. Health-related quality of life in patients with coronary artery disease treated for angina: validity and reliability of German translations of two specific questionnaires. Qual Life Res. 2003;12(2):199–212. doi: 10.1023/a:1022272620947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Arnold SV, Morrow DA, Wang K, et al. MERLIN-TIMI 36 Investigators Effects of ranolazine on disease-specific health status and quality of life among patients with acute coronary syndromes: results from the MERLIN-TIMI 36 randomized trial. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2008;1(2):107–115. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.108.798009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Arnold SV, Spertus JA, Jones PG, Xiao L, Cohen DJ. The impact of dyspnea on health-related quality of life in patients with coronary artery disease: results from the PREMIER registry. Am Heart J. 2009;157(6):1042–1049.e1041. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2009.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Asadi-Lari M, Packham C, Gray D. Gender difference in health-related needs and quality of life in patients with acute chest pain. Br J Cardiol. 2005;12(6):459–464. [Google Scholar]

- 54.de Jong-Watt WJ, Arthur HM. Anxiety and health-related quality of life in patients awaiting elective coronary angiography. Heart & Lung. 2004;33(4):237–248. doi: 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2004.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]