We describe a case of a brainstem glioma (BSG) occurred in an adult patient with neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1) and evaluated by Flourine-18-Fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography/computed tomography (18F-FDG-PET/CT). A 32-year-old male patient with NF1 underwent brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) for the onset of diplopia, facial paresis and cerebellar signs and symptoms. MRI showed a brainstem lesion compatible with BSG. Biopsy was not performed. 18F-FDG-PET/CT demonstrated intense 18F-FDG uptake in the brainstem lesion, suggesting an aggressive neoplasm. The patient was referred to radiotherapy but he developed rapid disease progression. In this case, 18F-FDG-PET/CT provided useful information about this rare NF1-associated tumor (Figs. 1 and 2).

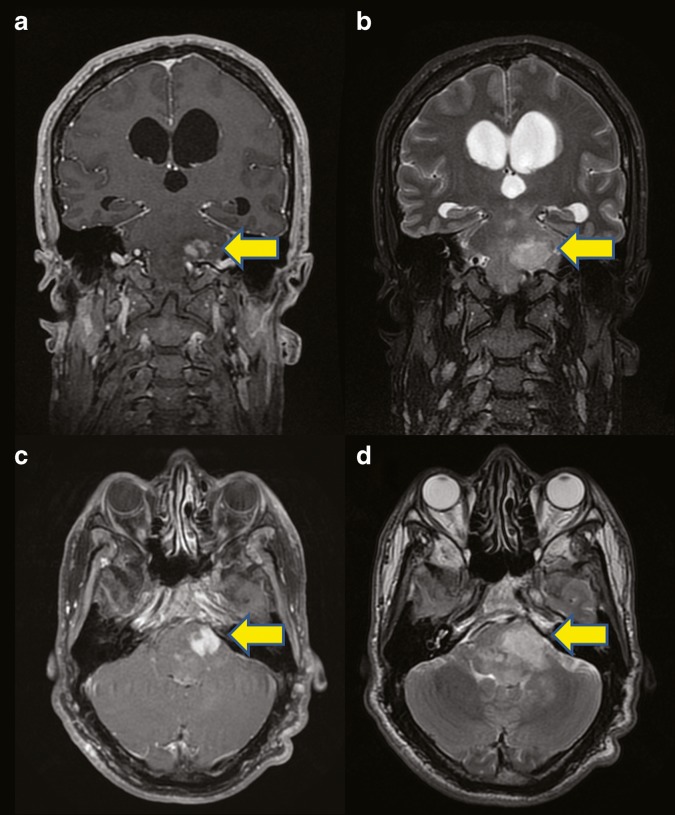

Fig. 1.

We report the case of a 32-year-old male patient with neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1) affected by a brainstem glioma (BSG). The patient underwent brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) for the onset of diplopia, facial paresis and cerebellar signs and symptoms. Coronal (a, b) and axial (c, d) enhanced T1-weighted (a, c) and T2-weighted (b, d) MR images showed the presence of a pontine-based infiltrative lesion (arrows), which presented inhomogenous signal intensity on both T1-weighted and T2-weighted images for the coexistence of isointense and hyperintense areas. These MRI findings were suggestive of a BSG

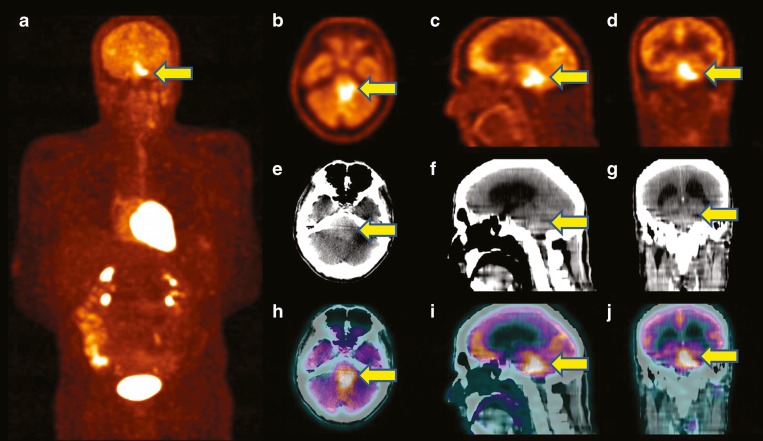

Fig. 2.

The biopsy of the lesion was not performed and the patient underwent 18F-FDG-PET/CT for the metabolic characterization of this brainstem lesion. Before 18F-FDG injection, the patient had fasted for at least 6 h; at the time of the radiopharmaceutical injection, the patient presented glucose blood levels corresponding to 99 mg/dL. Images were acquired 1 h after intravenous injection of 280 MBq of 18F-FDG according to the body mass index. The unenhanced CT scan was performed from the vertex to the inguinal region with a voltage of 120 keV and tube current of 30 mA. This scan was used for the anatomic localization and the attenuation correction of PET data. PET scan was acquired in 3D mode (multiple bed positions, 3 min for each bed position). Iterative reconstruction and CT-based attenuation correction were used. Whole-body maximum intensity projection (MIP) 18F-FDG-PET image (a) showed an area of intense 18F-FDG uptake in the brainstem (arrow). 18F-FDG-PET (b–d), unenhanced CT (e–g) and fused PET/CT images (h–j), in axial (b, e, h), sagittal (c, f, i) and coronal (d, g, j) projection showed increased radiopharmaceutical uptake corresponding to the known brainstem lesion, with a maximal standardized uptake value of 10.7, suggesting the presence of an aggressive neoplasm

Subsequently, the patient was referred to radiotherapy, but he developed rapid disease progression and died 3 months later. NF-1 is an autosomal dominant disorder characterized by multiple café-au-lait spots, axillary and inguinal freckling, multiple cutaneous neurofibromas, and iris Lisch nodules [1]. NF-1 is also characterized by low-grade tumors of the central and peripheral nervous system. There is also an increased risk of developing malignant tumors such as malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors or central nervous system high-grade gliomas [1, 2]. NF1-associated BSGs are less common than NF1-associated optic gliomas (OGs) and seem to represent a particular entity which tend, as a whole, to have a more favorable prognosis and a more indolent course than BSGs in patients without NF1 [3–5]; nevertheless, some NF1-associted BSG may rapidly progress [4]. 18F-FDG-PET/CT has demonstrated to provide useful information to the surveillance of OGs in children with NF1, particularly to identify progressive, symptomatic tumors [6–8]. To the best of our knowledge, there are no data about the usefulness of 18F-FDG-PET/CT in adult patients with NF1-associated BSG. In our case, 18F-FDG-PET/CT has been useful in evaluating this rare NF1-associated tumor.

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of interest

None.

Funding

None.

References

- 1.Jett K, Friedman JM. Clinical and genetic aspects of neurofibromatosis 1. Genet Med. 2010;12:1–11. doi: 10.1097/GIM.0b013e3181bf15e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Albers AC, Gutmann DH. Gliomas in patients with neurofibromatosis type 1. Expert Rev Neurother. 2009;9:535–9. doi: 10.1586/ern.09.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Salmaggi A, Fariselli L, Milanesi I, et al. Natural history and management of brainstem gliomas in adults. A retrospective Italian study. J Neurol. 2008;255:171–7. doi: 10.1007/s00415-008-0589-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Laigle-Donadey F, Doz F, Delattre JY. Brainstem gliomas in children and adults. Curr Opin Oncol. 2008;20:662–7. doi: 10.1097/CCO.0b013e32831186e0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ullrich NJ, Raja AI, Irons MB, et al. Brainstem lesions in neurofibromatosis type 1. Neurosurgery. 2007;61:762–6. doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000298904.63635.2D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moharir M, London K, Howman-Giles R, et al. Utility of positron emission tomography for tumour surveillance in children with neurofibromatosis type 1. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2010;37:1309–17. doi: 10.1007/s00259-010-1386-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Roselli F, Pisciotta NM, Aniello MS, et al. Brain F-18 Fluorocholine PET/CT for the assessment of optic pathway glioma in neurofibromatosis-1. Clin Nucl Med. 2010;35:838–9. doi: 10.1097/RLU.0b013e3181ef0b45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Treglia G, Taralli S, Bertagna F, et al. Usefulness of whole-body fluorine-18-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography in patients with neurofibromatosis type 1: a systematic review. Radiol Res Pract. 2012;2012:431029. doi: 10.1155/2012/431029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]