Abstract

This study used a multi-wave design to examine the short-term longitudinal and bidirectional associations between depressive symptoms and peer relationship qualities among a sample of early to middle adolescents (N=350, 6th–10th graders). Youth completed self-report measures of relationship quality and depressive symptoms at three time points spaced about 5 weeks apart. Results indicated that depressive symptoms predicted increases in negative qualities, and decreases in positive qualities. However, neither positive nor negative relationship qualities predicted increases in depressive symptoms. Findings inform a developmentally based interpersonal model of depression by advancing knowledge on the longitudinal direction of effects between depressive symptoms and relationship quality in adolescence.

Adolescence is marked by an increase in the significance of peer relationships. Peers become increasingly frequent providers of social support and companionship (Furman & Buhrmester, 1992), although parent relationships remain important (Steinberg, 2001). This increase in intimacy and companionship is observed within same-sex friendships as well as other-sex and romantic relationships (Kuttler & La Greca, 2004). The growing importance of peer relationships during adolescence parallels the rise in depression levels. Depression rates increase starting in early adolescence and continue to rise throughout adolescence until they reach rates found among adults (Hankin et al., 1998).

A developmental psychopathology perspective and interpersonal theories of depression emphasize transactional processes between an individual and the social environment. Characteristics and behaviors of depressed individuals elicit problems in their relationships, and in turn, these maladaptive relationships lead to the maintenance and exacerbation of depressive symptoms over time (Cicchetti & Schneider-Rosen, 1984; Joiner & Coyne, 1999). Interpersonal theories, which were originally applied to adult depression, provide a foundation for more developmentally based interpersonal models that highlight the way in which continuous transactions between youth and their social environment over time contribute to increases in depression (Rudolph, Flynn, & Abaied, 2008). The quality of peer relationships is one important aspect of adolescents’ social environment. However, little is known about potential bidirectional, transactional associations between poor relationship quality and depressive symptoms over time among adolescents.

Having close relationships with peers is important for adolescent development, yet a dark side of relationships (e.g., conflict, antagonism, criticism) can co-exist along with positive aspects of close friendships in adolescence (Berndt, 2004). Close friendships can have significant costs when friendship quality is poor, including internalizing problems, loneliness, and depressive symptoms (Nangle, Erdley, Newman, Mason, & Carpenter; 2003; Rubin, Wojslawowicz, Rose-Krasnor, Booth-LaForce, & Burgess, 2006). Several studies show a concurrent association between poor relationship quality with peers and depressive symptoms among youth (e.g., Borelli & Prinstein, 2006; Brendgen, Vitaro, Turgeon & Poulin, 2002; Goodyer, Wright, & Altham, 1990; Oldenberg & Kerns, 1997; Puig-Antich et al., 1993; Windle, 1994). For example, La Greca and Harrison (2005) showed that negative features within best friendships and romantic relationships were associated with adolescent depressive symptoms. However, these studies did not employ longitudinal designs, so they could not investigate the temporal direction of this relation or potential transactional associations.

Theory suggests that poor relationship quality may predict later depression (Sullivan, 1953; Rubin, Bukowski, & Parker, 1998). Low quality relationships may disrupt normal developmental processes, such as identity development, social skills, and emotional functioning (Clark & Dewry, 1985; Ladd & Troop-Gordon, 2003), and lead to poor self-perceptions of social competencies (Cole, Martin, & Powers, 1997) and possibly depression (Rudolph et al., 2008). Despite such developmental theory, few studies have examined whether poor friendship quality leads to later depressive symptoms. Interpersonal stress in peer relationships longitudinally predicts increases in depressive symptoms among adolescents (Hankin, Mermelstein, & Roesch, 2007; Rudolph, 2002; Rudolph, Flynn, Abaied, Groot, & Thompson, 2009). However, interpersonal stressors are broader in scope than measures assessing relationship quality specifically, and the two are not interchangeable.

Only two studies have tested longitudinal associations between relationship quality and depressive symptoms. One study showed that low positive qualities in same-sex friendships did not predict depressive symptoms 11 months later among 6th to 8th grade boys and girls who exhibited low excessive reassurance seeking; however, low positive qualities interacted with high excessive reassurance seeking to predict depressive symptoms among girls (Prinstein, Borelli, Cheah, Simon, & Aikins, 2005). In the second study, low positive qualities did not predict increases in depressive symptoms, or the onset of a major depressive disorder, two years later (Stice, Ragan, & Randall, 2004). However, this study is limited by a girls only sample, and an examination of only positive, but not negative, peer relationship qualities. No previous study has examined whether both negative and positive relationship qualities as main effects longitudinally predict depressive symptoms among adolescents.

The opposite direction in the transactional association, in which initial depression predicts worsening of relationship quality, is also plausible. Symptoms, behaviors, and characteristics associated with depression may interfere with adaptive interpersonal functioning and over time lead to decreases in the quality of relationships (Gotlib & Hammen, 1992; Rudolph et al., 2008; Windle, 1994). Cross-sectional studies show that depressed youth, compared to nondepressed youth, elicit more negative interactions with peers. For example, observational research shows that social interactions between children with high levels of depressive symptoms and both familiar and unfamiliar peers are characterized by increased conflict and negative affect, and decreased collaboration and mutuality, compared to children with low levels of depressive symptoms (Altmann & Gotlib, 1988; Rudolph, Hammen, & Burge, 1994). Moreover, unfamiliar peers interacting with clinically depressed adolescents perceive these individuals to be less interested in establishing a friendship and to be a less desirable potential friend than nondepressed adolescents (Connolly, Geller, Marton, & Kutcher, 1992).

Few prospective studies have investigated associations between depressive symptoms and later relationship quality among youth. The interpersonal stress generation literature suggests that depressive symptoms may longitudinally predict increases in interpersonal stressors (Daley et al., 1997; Hankin et al., 2007; Rudolph, 2008; Rudolph et al., 2009). However, again stress is not equivalent to measures designed to assess relationship quality specifically. Only three studies have examined prospective associations between depressive symptoms and later relationship quality. One study showed that chronic depressive symptoms among youth from 3rd through 5th grade predicted increases in negative qualities among 6th grade girls but not boys (Rudolph, Ladd, & Dinella, 2007). Prinstein et al. (2005) found that depressive symptoms were associated with self-reported negative qualities 11 months later for both boys and girls in 6th to 8th grade. Last, both clinical depression and depressive symptoms predicted decreases in positive relationship qualities two years later in Stice et al.’s (2004) sample of adolescent girls. Overall, there is support for the longitudinal association between initial depression and later poor relationship quality among adolescents, but little is known about whether this finding applies to both adolescent boys and girls.

In sum, there is a concurrent link between depressive symptoms and peer relationship quality, but few longitudinal studies have examined potential bidirectional and transactional associations. It is unknown whether relationship quality predicts depressive symptoms, depressive symptoms predict relationship quality, or if these associations are concurrent only. The purpose of the current study was to test a developmentally based interpersonal model of depression in which there are transactions between depressed youth and relationship quality over time. This study is the first multi-wave short-term longitudinal investigation of transactional associations between negative and positive relationship qualities and depressive symptoms among both adolescent boys and girls.

Method

Participants and Procedures

Participants were part of a short-term longitudinal study of youth who were recruited from five Chicago area schools. There were 467 students total in the appropriate grades (6th–10th) on the day in which research personnel first visited the schools, and all students were invited to participate. Parents of 390 youth (83.5%) provided active consent; all 390 youth were willing to participate and assented to be in the study. 356 youth (91%) completed the baseline questionnaire. The 34 students who were willing to participate but did not complete the baseline visit were sick or absent from school and were unable to reschedule. For this study, we examined data from 350 youth who provided complete data at baseline. Attrition analyses showed that youth who participated at baseline but not at other time points were not significantly different on demographic characteristics (age, gender, ethnicity, or any initial symptom or relationship quality scores) compared to those participants who were present at all time points. Missing data were imputed using Expectation Maximization (EM) procedures. The age range at baseline was 11–17 (M = 14.5; SD = 1.40); 9% were in 6th grade, 9% in 7th grade, 9% in 8th grade, 27% in 9th grade, and 46% in 10th grade. 57% were female; 53% White, 21% African-American, 13% were Latino, 6% were Asian or Pacific Islander, and 7% bi- or multi-racial. The rationale for studying 6th–10th graders is that this is when depressive symptoms increase and youth begin to place increasing emphasis on peer relationships. Thus, this may be an optimal age window for studying longitudinal relations among relationship quality and depressive symptoms.

Permission to conduct this investigation was provided by the school districts and their institutional review boards, school principals, the individual classroom teachers, and university institutional review board. Trained research personnel visited classrooms in the schools and briefly described the study to youth. Letters describing the study were sent home to parents. Students who agreed to participate returned active parental consent as well as read and signed their own informed assent form after having the opportunity to ask any questions about the study. Youth completed a battery of questionnaires during class time. They were debriefed at the end of the study. Youth completed questionnaires at three time points with approximately five weeks in between each time point. The assessments in this study took place during a single academic year, and there was no obvious developmental transition (e.g., change of grade) for most youth. Youth were compensated ten dollars for their participation at each wave of the study.

Measures

Children’s Depression Inventory (CDI;Kovacs, 1992). The CDI is a self-report measure that assesses depressive symptoms in children and adolescents using 27 items. The CDI has good reliability and validity in youth (Klein, Dougherty, & Olino, 2005). Internal reliability in this sample was α = .91.

Network of Relationships Inventory (NRI, Furman & Burhmester, 1985). The original NRI is a 30-item self-report measure that assesses relationship quality in children and adolescents. A 13-item short form was used in the present study (Furman & Buhrmester, 2009). Participants responded to all 13 items for several different types of relationships and answered questions about only one person for each relationship type. For this study, only responses for same-sex friend, other-sex friend, and romantic partner were used. The NRI has good reliability and validity, and it has a factor structure of two factors for each relationship: positive and negative relationship quality (Furman, 1996). Internal reliability for this sample was α = .86. The short form has 7 items assessing positive qualities (e.g., “how much do you play around and have fun with this person?”, “how much does this person help you figure out or fix things?”) and 6 items assessing negative qualities (e.g., “how much do you and this person disagree and quarrel?”, “how much do you and this person get upset with or mad at each other?”). We combined scores on the negative relationship quality factor for romantic partner, same-sex friend, and other-sex friend to create one overall peer negative relationship quality score. Likewise, scores assessing positive relationship quality in the three relationships were combined to create an overall peer positive relationship quality score. This resulted in a possible range of scores from 3–15 for each factor.

Results

Descriptive statistics and correlations of the main variables are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Means, Standard Deviations and Correlations Among Primary Variables

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Depressive symptoms T1 | - | ||||||||

| 2. Negative qualities T1 | .34** | - | |||||||

| 3. Positive qualities T1 | −.15** | −.15** | - | ||||||

| 4. Depressive symptoms T2 | .69** | .20** | −.11* | - | |||||

| 5. Negative qualities T2 | .24** | .32** | −.01 | .36** | - | ||||

| 6. Positive qualities T2 | −.19** | −.10 | .41** | −.32** | −.12* | - | |||

| 7. Depressive symptoms T3 | .68** | .21** | −.05 | .71** | .34** | −.16** | - | ||

| 8. Negative qualities T3 | .13* | .16** | −.03 | .13* | .07 | −.12* | −.07 | - | |

| 9. Positive qualities T3 | −.20* | −.06 | .20** | −.21** | .01 | .23** | −.23** | −.21** | |

| Mean | 12.05 | 5.11 | 8.92 | 12.26 | 5.26 | 8.65 | 15.17 | 7.71 | 8.57 |

| SD | 9.19 | 1.03 | 1.59 | 9.28 | .97 | 1.56 | 12.95 | 1.96 | 1.27 |

p ≤ .01.

p ≤ .05.

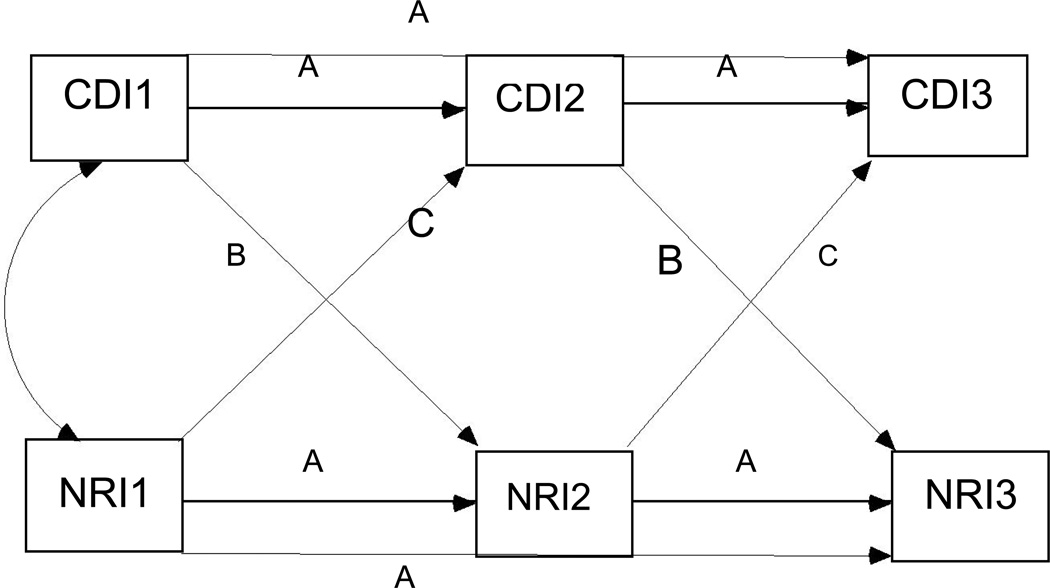

Crossed-lagged effects structural equation models (SEM) using AMOS 16.0 (Arbuckle, 2006) were used to test transactional associations between depressive symptoms and relationship quality over time. Separate models were fitted for negative qualities and positive qualities of relationships. When testing cross-lagged models in SEM, it is best to compare competing models to test several assumptions about the directions of effects (Anderson, 1987). We compared each full cross-lagged model to two other models in a series of steps to determine whether the inclusion of bidirectional cross-lagged effects resulted in a significant improvement in the model above and beyond concurrent associations, construct stability, and unidirectional cross-lagged effects (see Figure 1). First, we fitted a baseline model including only autoregressive effects and stability paths. Errors were allowed to covary for measures occurring at the same time point. Second, we compared a unidirectional model, with paths from CDI to NRI, to the baseline model. Finally, we compared the full bi-directional model, including paths from NRI to CDI, to the unidirectional model. Chi-square difference tests were used to compare competing models. A multigroup comparison approach was used to test whether the best fitting model for each aspect of relationship quality (positive and negative) was moderated by age or gender. A median split was used to create groups to test age as a moderator. For these multigroup analyses, we compared a model in which all paths were freed across groups (the unconstrained model) to the constrained model in which cross-lagged paths were constrained across groups. Chi-square difference tests revealed that neither age nor gender moderated associations for either model. Therefore, the following analyses are presented for the overall sample.

Figure 1.

A: Paths included in the baseline models. B: Paths included in the unidirectional model, in addition to all paths in baseline model. C: Paths included in bidirectional model, in addition to all paths in baseline and unidirectional model.

Table 2 shows fit statistics for these models. To determine whether the autoregressive paths should be constrained or allowed to vary for the negative qualities model, CDI and NRI paths from T1 to T2 and from T2 to T3, were constrained and compared to an unconstrained model. Supporting the assumption that autogressive effects were consistent across waves, the unconstrained and constrained model did not differ, χ2 (2) = 2.41, p = .30. Therefore, autoregressive paths were constrained for the baseline and subsequent models. As Table 2 shows, the unidirectional model fit significantly better than the baseline model, χ2 (2) = 9.19, p = .01. However, the bidirectional model did not significantly fit better than the unidirectional model, χ2 (2) = 4.69, p =.10. Thus, the unidirectional model, with paths from CDI to NRI, was the most parsimonious model. These unidirectional paths from CDI to later NRI were consistent across time as a constrained unidirectional path model did not differ from an unconstrained model, χ2 (1) = .05, p =.82. Table 3 shows the final model with positive and significant constrained unidirectional paths from CDI to NRI.

Table 2.

Fit Indices for Primary Models

| Negative qualities | Positive qualities | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | χ2 | df | CFI | RMSEA | χ2 | df | CFI | RMSEA |

| Baseline model (unconstrained) | 20.20** | 6 | .98 | .08 | 19.87** | 6 | .98 | .08 |

| Baseline model (constrained)1 | 22.61** | 8 | .98 | .07 | 20.19** | 7 | .98 | .07 |

| Unidirectional model (unconstrained) | 13.42* | 6 | .99 | .06 | 6.14 | 5 | 1.00 | .03 |

| Bidirectional model | 8.73 | 4 | .99 | .06 | 3.07 | 3 | 1.00 | .01 |

| Final model – Unidirectional model (constrained)2 | 13.47 | 7 | .99 | .05 | 6.14 | 6 | 1.00 | .01 |

Autoregressive effects for CDI and NRI were set to be equal over time for negative qualities; only CDI autoregressive effects were set to be equal over time for positive qualities.

Unidirectional effects from CDI to NRI were set to be equal over time.

p ≤ .01.

p ≤ .05.

Table 3.

Standardized Path Coefficients for Final Models

| Paths | Negative qualities | Positive qualities |

|---|---|---|

| Autoregressive and Stability Paths | ||

| CDI: time 1 to time 2 | .68***a | .68***a |

| CDI: time 2 to time 3 | .48***a | .48***a |

| CDI: time 1 to time 3 | .35*** | .34*** |

| NRI: time 1 to time 2 | .25***b | .39*** |

| NRI: time 2 to time 3 | .11***b | .13* |

| NRI: time 1 to time 3 | .10* | .14* |

| Unidirectional Cross-Lagged Paths | ||

| CDI time 1 to NRI time 2 | .14**c | −.12***c |

| CDI time 2 to NRI time 3 | .07**c | −.15***c |

Note. Superscripts indicate paths were constrained.

p ≤ .001

p ≤ .01.

p ≤ .05.

We used the same sequence of steps to determine the best model for positive relationship qualities. Table 2 shows fit statistics for primary models. The model in which autoregressive paths were constrained provided a much worse fit to the data than the unconstrained model, χ2 (2) = 14.70, p < .001. However, there was no significant difference between a model in which only CDI autoregressive paths were constrained and an unconstrained model, Χ2 (1) = .32, p =.57, suggesting that CDI autoregressive paths were consistent across waves, whereas positive qualities varied. Thus, only CDI autoregressive paths were constrained for baseline and all subsequent models. Table 2 shows that the unidirectional model fit significantly better than the baseline model, χ2 (2) = 14.05, p <.001. The bidirectional model for positive qualities did not provide a significantly better fit than the unidirectional model, χ2 (2) = 3.07, p =.22, again suggesting that the unidirectional model is the most parsimonious model. The unidirectional paths were consistent across waves as the χ2 for the unconstrained model and a model in which unidirectional paths from CDI to NRI were constrained was identical (χ2 = 6.14). Table 3 shows that the path coefficients from CDI to NRI positive qualities were negative and significant.

Discussion

Adolescence is period of transition and change in interpersonal relationships as youth increasingly spend more time with peers and experiment with different social roles. At the same time, adolescence is when many individuals exhibit increases in depressive symptoms. Understanding more about longitudinal associations and the temporal direction between peer relationships and depressive symptoms can thus inform social developmental theory as well as developmental psychopathology and interpersonal models of depression. The few prior studies investigating relations between adolescent peer relationships and depressive symptoms were generally limited by cross sectional designs (e.g., La Greca & Harrison, 2005), gender specific samples (e.g., girls only; Stice et al., 2004), or imprecise measures of relationship quality (e.g., measures of interpersonal stress; Hankin et al., 2007). As a result, knowledge of longitudinal associations between relationship quality and depressive symptoms during adolescence has been lacking. Results from this study show that depressive symptoms prospectively predict decreases in relationship quality with peers. Specifically, depressive symptoms predicted both increases in negative qualities and decreases in positive qualities over time in this multi-wave prospective design. However, poor relationship quality, whether low positive qualities or high negative qualities, did not predict prospective changes in depressive symptoms. These findings advance knowledge on the longitudinal direction of effects between depressive symptoms and relationship quality.

The results showing that depressive symptoms were associated with poor relationship quality over time was a robust finding that was observed at all time points as well as for both negative and positive relationship qualities. Furthermore, this finding held for both boys and girls, as well as for both early and middle adolescents. These results are consistent with prior research and theory proposing that characteristics and behaviors associated with depression disrupt interpersonal functioning (Gotlib & Hammen, 1992; Joiner & Coyne 1999; Rudolph et al., 2008). The findings specifically suggest that depressive symptoms interfere with the formation of high quality peer relationships, such that dysphoric adolescents’ relationships have fewer positive aspects (e.g., intimacy, support) and more negative aspects (e.g., conflict and antagonism). Rudolph et al. (2007) found that depressive symptoms predicted poor relationship quality for girls, but not boys, among 3rd to 6th graders. It is possible that among older adolescents, depressive symptoms are just as disruptive for establishing good quality relationships for boys and girls because peers grow in importance for both genders during adolescence (Buhrmester, 1990).

Findings from this study also consistently indicated that poor relationship quality alone did not predict increases in depressive symptoms. Two other studies have also shown that a lack of positive qualities is not associated with increases in depressive symptoms among adolescents (Prinstein et al., 2005; Stice et al., 2004). This study is the first to also suggest that negative qualities do not predict depressive symptoms. However, poor relationship qualities can predict increases in depressive symptoms when moderated by other risk factors. For example, Prinstein and colleagues (2005) showed that low positive qualities interacted with excessive reassurance seeking to predict increases in depressive symptoms. Given the consistent lack of support for the main effect of poor relationship quality predicting future depressive symptoms, greater traction in understanding ontogeny of adolescent depression is likely with future research focusing on risk factors moderating the association between relationship quality and later depression as well as the mechanisms through which relationship quality may amplify the effects of these vulnerabilities.

Despite several strengths (e.g., multi-wave design, examination of both positive and negative relationship qualities), future research is needed to address limitations. First, self-report methods assessed depressive symptoms and relationship quality, and the mono-method, mono-informant design can inflate associations. Future studies should investigate hypotheses with peer-reports of relationship quality and observational methods. Second, the CDI was originally developed to assess depressive symptoms in youth and is the most commonly used measure of youth depression (Klein et al., 2005). However, it correlates moderately with general anxiety symptoms and may be a better measure of broad negative affect, rather than depressive symptoms per se (Klein et al., 2005). Broad negative affect underlies both depression and anxiety (Clark & Watson, 1991). An informative question for future research is to determine whether depressive symptoms as opposed to broad negative affect (e.g., irritability, poor concentration, etc.) are particularly and specifically harmful to relationship quality. Third, we only examined broad factors of positive and negative relationship qualities using a short form of the NRI. It would be interesting to examine whether associations vary with different scales on these factors, such as conflict, criticism, intimacy, support, etc. Relatedly, the NRI used in this study measured quality of peer relationships (same-sex, opposite-sex, romantic), did not assess how much youth valued each type of relationship or whether adolescents were currently in romantic relationships or platonic friendships. Fourth, future research should explore different time prospective follow-up intervals as it is unknown what the optimal time is for studying longitudinal associations between relationship quality and depressive symptoms. Short time frames, such as used in this study, may be ideal to capture effects and reduce recall problems or memory bias, but it is possible that poor relationship quality only predicts depressive symptoms over longer periods of time. Finally, effect sizes were relatively small, although this may be reasonable given that we controlled for stability in both depressive symptoms and relationship quality over time. Still, larger effects may be observed if these limitations are improved.

Implications for Research, Policy, and Practice

These findings have potential clinical implications for the assessment, prevention, and treatment of depression among adolescents. Mental health professionals should be aware that behaviors, characteristics, and symptoms associated with depressive symptoms can interfere with the formation of high quality peer relationships. Use of empirically supported interventions, such as manualized cognitive-behavioral treatments for youth that include a social skills component (e.g., Stark, 1990), or treatments that exclusively target interpersonal issues such as Interpersonal Psychotherapy (IPT; Mufson, Dorta, Moreau, & Weissman, 2004), may be particularly effective when treating adolescent depression. This study also showed how depressive symptoms were associated with the quality of a combination of several different types of peer relationships (same-sex friendships, other-sex friendships, and romantic relationships), which suggests that it will be important to not only consider the role of interpersonal functioning in platonic friendships, but also in romantic relationships. Finally, clinical interventions for adolescent depression will benefit from future research that thoroughly explores mediating mechanisms that can account for the associations between depressive symptoms and later decreases in relationship quality. For example, depressive symptoms, such as anhedonia, irritability, and negative affect, might lead to social withdrawal, or generate more stress in relationships, which in turn may lead to decreases in relationship quality over time. In conclusion, findings from this study are an important step towards understanding and alleviating the effects of depression during the adolescent period.

References

- Altmann EO, Gotlib IH. The social behavior of depressed children: An observational study. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1988;16:29–44. doi: 10.1007/BF00910498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson JG. Structural equation models in the social and behavioral sciences: Model building. Child Development. 1987;58:49–64. [Google Scholar]

- Arbuckle JL. AMOS 16.0 user’s guide. Chicago: SPSS; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Berndt TJ. Children’s friendships: Shifts over a half century in perspective on their development and their effects. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly. 2004;50:206–223. [Google Scholar]

- Borelli JL, Prinstein MJ. Reciprocal, longitudinal associations among adolescents’ negative feedback seeking, depressive symptoms, and peer relations. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2006;34:159–169. doi: 10.1007/s10802-005-9010-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brendgen M, Vitaro F, Turgeon L, Poulin F. Accessing aggressive and depressed children’s social relations with classmates and friends: A matter of perspective. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2002;30:609–624. doi: 10.1023/a:1020863730902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buhrmester D. Intimacy of friendship, interpersonal competence, and adjustment during preadolescence and adolescence. Child Development. 1990;61:1101–1111. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D, Schneider-Rosen K. Toward a transactional model of childhood depression. New Directions for Child Development. 1984;26:5–27. [Google Scholar]

- Clark ML, Drewry DL. Similarity and reciprocity in the friendships of elementary school children. Child Study Journal. 1985;15:251–264. [Google Scholar]

- Clark LA, Watson D. Tripartite model of anxiety and depression: Psychometric evidence and taxonomic implications. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1991;100:316–336. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.100.3.316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole DA, Martin JM, Powers B. A competency-based model of child depression: A longitudinal study of peer, parent, teacher, and self-evaluations. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1997;38:505–514. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1997.tb01537.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connolly J, Geller S, Marton P, Kutcher S. Peer responses to social interaction with depressed adolescents. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 1992;21:365–370. [Google Scholar]

- Coyne JC. Toward an interactional description of depression. Psychiatry: Journal for the Study of Interpersonal Processes. 1976;39:28–40. doi: 10.1080/00332747.1976.11023874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daley SE, Hammen C, Burge D, Davila J, Paley B, Lindberg N, et al. Predictors of the generation of episodic stress: A longitudinal study of late adolescent women. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1997;106:251–259. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.106.2.251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furman W. The measurement of friendship perceptions: Conceptual and methodological issues. In: Bukowski WM, Newcomb AF, Hartup WW, editors. The company they keep: Friendship in childhood and adolescence. New York: Cambridge; 1996. pp. 41–65. [Google Scholar]

- Furman W, Buhrmester D. Children’s perceptions of the personal relationships in their social networks. Developmental Psychology. 1985;21:1016–1024. [Google Scholar]

- Furman W, Buhrmester D. Age and sex differences in perceptions of networks of personal relationships. Child Development. 1992;63:103–115. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1992.tb03599.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furman W, Buhrmester D. Network of Relationships Questionnaire Manual. 2009. Unpublished manual, University of Denver, Colorado. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodyer I, Wright C, Altham P. The friendships and recent life events of anxious and depressed school-age children. British Journal of Psychiatry. 1990;156:689–698. doi: 10.1192/bjp.156.5.689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotlib IH, Hammen CL. Psychological aspects of depression: Toward a cognitive-interpersonal integration. Oxford, England: John Wiley & Sons; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Hankin BL, Abramson LY, Moffitt TE, McGee R, Silva PA, Angell KE. Development of depression from preadolescence to young adulthood: Emerging gender differences in a 10-year longitudinal study. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1998;107:128–140. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.107.1.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hankin BL, Mermelstein R, Roesch L. Sex differences in adolescent depression: Stress exposure and reactivity models. Child Development. 2007;78:278–295. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.00997.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joiner T, Coyne JC. The interactional nature of depression: Advances in interpersonal approaches. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Klein DN, Dougherty LR, Olino T. Toward guidelines for evidence based assessment of depression in children and adolescents. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2005;34:412–432. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3403_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs M. Children’s Depression Inventory (CDI) manual. New York: Multi-Health Systems; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Kuttler AF, La Greca AM. Linkages among adolescent girls’ romantic relationships, best friendships, and peer networks. Journal of Adolescence. 2004;27:395–414. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2004.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ladd GW, Troop-Gordon W. The role of chronic peer difficulties in the development of children’s psychological adjustment problems. Child Development. 2003;74:1344–1367. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- La Greca AM, Harrison HM. Adolescent peer relations, friendships, and romantic relationships: Do they predict social anxiety and depression. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2005;34:49–61. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3401_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mufson L, Dorta KP, Moreau D, Weissman MM. Interpersonal psychotherapy for depressed adolescents. New York: Guilford; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Nangle DW, Erdley CA, Newman JE, Mason CA, Carpenter EM. Popularity, friendship quantity, and friendship quality: Interactive influences on childrens’ loneliness and depression. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2003;32:546–555. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3204_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oldenberg CM, Kerns KA. Associations between peer relationships and depressive symptoms: Testing moderator effects of gender and age. Journal of Early Adolescence. 1997;17:319–337. [Google Scholar]

- Prinstein MJ, Borelli JL, Cheah CSL, Simon VA, Aikins JW. Adolescent girls’ interpersonal vulnerability to depressive symptoms: A longitidunal examination of reassurance-seeking and peer relationships. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2005;114:676–688. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.114.4.676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puig-Antich J, Kaufman J, Ryan ND, Williamson DE, Dahl RE, Lukens E, et al. The psychosocial functioning and family environment of depressed adolescents. Journal of American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1993;32:244–253. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199303000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin KH, Bukowski W, Parker JG, Damon W, Eisenberg N. Handbook of child psychopathology(5th ed.): Vol.3. social, emotional, and personality development. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons; 1998. pp. 619–700. [Google Scholar]

- Rubin KH, Wojslawowicz JC, Rose-Krasnor L, Booth-Laforce C, Burgess KB. The best friendships of shy/withdrawn children: Prevalence, stability, and relationship quality. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2006;34:143–157. doi: 10.1007/s10802-005-9017-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudolph KD, Hammen C, Burge D. Interpersonal functioning and depressive symptoms in childhood: Addressing the issues of specificity and comorbidity. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1994;22:355–371. doi: 10.1007/BF02168079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudolph KD. Gender differences in emotional responses to interpersonal stress during adolescence. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2002;30:3–13. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(01)00383-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudolph KD. Developmental influences on interpersonal stress generation in depressed youth. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2008;117:673–679. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.117.3.673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudolph KD, Flynn M, Abaied JL. A developmental perspective on interpersonal theories of youth depression. In: Abela JRZ, Hankin BL, editors. Handbook of depression in children and Aaolescents. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Rudolph KD, Flynn M, Abaied JL, Groot A, Thompson R. Why is past depression the best predictor of future depression? Stress generation as mechanism of depression continuity girls. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2009;38:473–485. doi: 10.1080/15374410902976296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudolph KD, Ladd G, Dinella L. Gender differences in the interpersonal consequences of early-onset depressive symptoms. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly. 2007;53:461–488. [Google Scholar]

- Stark KD. Childhood Depression: School-based Intervention. New York: Guilford; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg L. We know some things: Parent-adolescent relationships in retrospect and prospect. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2001;11:1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Stice E, Ragan J, Randall P. Prospective relations between social support and depression: Differential direction of effects for parent and peer support. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2004;113:155–159. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.113.1.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan HS. The interpersonal theory of psychiatry. New York: Norton; 1953. ok. [Google Scholar]

- Windle M. A study of friendship characteristics and problem behaviors among middle adolescents. Child Development. 1994;65:1764–1717. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1994.tb00847.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]