Abstract

Objectives

To evaluate the neurodevelopmental outcomes of very preterm (<30 weeks) infants who underwent tracheostomy.

Study design

Retrospective cohort study from 16 centers of the NICHD Neonatal Research Network over 10 years (2001-2011). Infants who survived to at least 36 weeks (N=8,683), including 304 infants with tracheostomies, were studied. Primary outcome was death or neurodevelopmental impairment (NDI, a composite of one or more of: developmental delay, neurologic impairment, profound hearing loss, severe visual impairment) at a corrected age of 18-22 months. Outcomes were compared using multiple logistic regression. We assessed impact of timing, by comparing outcomes of infants who underwent tracheostomy before and after 120 days of life.

Results

Tracheostomies were associated with all neonatal morbidities examined, and with most adverse neurodevelopmental outcomes. Death or NDI occurred in 83% of infants with tracheostomies and 40% of those without [odds ratio (OR) adjusted for center 7.0 (95%CI, 5.2-9.5)]. After adjustment for potential confounders, odds of death or NDI remained higher [OR 3.3 (95%CI, 2.4-4.6)], but odds of death alone were lower [OR 0.4 (95%CI, 0.3-0.7)], among infants with tracheostomies. Death or NDI was lower in infants who received their tracheostomies before, rather than after, 120 days of life [adjusted OR 0.5 (95%CI, 0.3-0.9)].

Conclusions

Tracheostomy in preterm infants is associated with adverse developmental outcomes, and cannot mitigate the significant risk associated with many complications of prematurity. These data may inform counseling about tracheostomy in this vulnerable population.

Keywords: newborn, very low birth weight infant, neurodevelopmental impairment, tracheotomy, bronchopulmonary dysplasia, prematurity

Decisions about whether and when to place a tracheostomy in preterm infants who require prolonged ventilation or who have airway abnormalities are challenging. Most tracheostomies in children are performed in infants less than 12 months of age.(1) A few small studies document the incidence of mortality and airway morbidity after tracheostomy in young children.(2-4) Even more limited data are published on longer-term morbidities and neurodevelopmental outcomes.(5-8) The most recent large, single-center cohort study of 165 infants with tracheostomies reported 3-year survival of 91%, but developmental delays in 64%. This study did not detail the timing or content of the developmental evaluations.(8)

Very preterm infants have a high baseline risk for adverse long-term outcomes, and severe lung disease substantially increases this risk.(9, 10) It is unknown whether tracheostomy is independently associated with an increased risk for adverse outcomes in preterm infants. Moreover, optimal timing for tracheostomy is unknown.(11, 12) Such information could help inform clinicians when making decisions with families about the timing of tracheostomy placement, and planning for the care of these children throughout childhood.

We performed a cohort study to evaluate the outcomes of very preterm infants undergoing tracheostomy in the NICHD Neonatal Research Network (NRN) over a 10-year period. Our goals were to report the developmental outcomes of infants with tracheostomies who were evaluated in follow-up at 18-22 months corrected age, in comparison with the rest of the population of very preterm infants; and to evaluate whether timing of tracheostomy is related to outcomes.

Methods

The NRN uses a predefined protocol which prospectively collects medical and developmental follow-up data at 18-22 months corrected age on all infants born with birth weight 401-1000 grams (if born before 1/1/2008) or before 27 weeks gestation (if born on or after 1/1/2008).(13) The same protocol is used to collect follow-up data about children of any gestational age who are enrolled in an NRN clinical trial requiring neurodevelopmental follow-up. In the current analyses we evaluated outcomes of the cohort of infants who were born before 30 weeks of gestation, who survived to at least 36 weeks postmenstrual age and who were eligible for follow-up at one of the 16 centers that participated in the NRN from 2001 to 2011. Institutional Review Boards at each study center approved the collection of data during both the initial hospitalization and neonatal follow-up.

The primary outcome was a composite of two important competing outcomes: death or neurodevelopmental impairment (NDI) at 18-22 months. Standard definitions of NDI were used: NDI consisted of neurologic impairment, developmental delay, or visual or hearing impairment.(14, 15) By expert consensus, the definition of NDI evolved after the Bayley Scales of Infant Development-II were replaced by the Bayley-III.(16-19) For children born before 1/1/2006, cutoffs for NDI were: neurologic impairment – moderate to severe cerebral palsy with Gross Motor Function Classification Scale (GMFCS) level of 2 or higher; developmental delay – Bayley-II Mental or Psychomotor Development Index (MDI or PDI) <70; visual impairment – <20/200 bilaterally; hearing impairment – bilateral amplification for permanent hearing loss.(20) Children born after 1/1/2006 were tested with the Bayley Scales of Infant Development-III. Cutoffs for NDI were: neurologic impairment – moderate to severe cerebral palsy; developmental delay: Bayley-III Cognitive or Motor score <85; visual impairment – limited with correction or blindness in one or both eyes; hearing impairment – permanent hearing loss that does not permit child to understand directions and communicate. An infant was considered to have NDI if one or more of the components of the composite outcome were known to be present, or unaffected if no component was present. If one or more components of NDI were missing and no component could be confirmed as abnormal, the primary outcome was deemed missing. To ensure that differences in primary outcomes could not be ascribed to the temporal change in testing regimens, a separate analysis was performed by time period of neurodevelopmental testing.

Secondary outcomes were the individual components of NDI, relationship between timing of tracheostomy and outcomes, results of the Brief Infant/Toddler Social and Emotional Assessment (BITSEA) scale and, for infants tested with the Bayley III, language scores with receptive and expressive language subscales.(17, 21, 22)

Bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD) was defined as oxygen use at 36 weeks postmenstrual age. Both the presence and the severity of BPD are independently associated with cognitive impairment.(23, 24) Therefore, to measure the severity of BPD, we described “prolonged ventilation” as receipt of mechanical ventilation for more than the 75th percentile (43 days). Brain injury was defined as intraparenchymal hemorrhage [Grade 4 intraventricular hemorrhage (IVH)], IVH with ventricular enlargement (Grade 3 IVH), or cystic periventricular leukomalacia on cranial ultrasound in the first 28 days. Severe retinopathy of prematurity (ROP) was defined as stage 3 or higher or any retinopathy that required treatment. Necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC) was defined as stage II or III, based on the modified Bell's staging criteria.(25) Infants were classified with malformations or syndromes if they were diagnosed with any major malformations, chromosomal abnormalities, or other syndromes with multi-organ involvement at any point during the hospitalization. Our data set allowed determination of “earlier” tracheostomy if infants received a tracheostomy prior to 120 days of life or “later” tracheostomy if they were subsequently coded as having a tracheostomy at the time of follow-up. All other infants were classified in the “no tracheostomy” group.

Statistical Analyses

We used traditional bivariate tests to compare baseline demographics and neonatal morbidities among infants with and without tracheostomies. We used t-tests for normally distributed continuous data, Poisson models for count data such as number of rehospitalizations, and chi-squared tests for dichotomous data. Odds of death or NDI, based on the presence of a tracheostomy at any time before follow-up, were evaluated with logistic regression. Regression models were first adjusted for center as a fixed effect. The analysis was then repeated with center and several additional pre-specified potential confounding variables. All of these variables were known to be independently correlated with survival or long-term developmental outcome. Variables fell into two groups: (1) baseline factors – birth weight (as a continuous variable), sex, antenatal steroid exposure, race, presence of syndromes or major malformations, and (2) neonatal morbidities (as defined above) – brain injury, sepsis, NEC, severe ROP, surgical ligation of patent ductus arteriosus (PDA), and BPD. To ensure that the above described changes in the definition of NDI did not lead to spurious associations, time period was included in all models.

The same models were used to compare components of the primary outcome, Bayley-III language scores, and other developmental outcomes between the groups and to generate risk-adjusted probabilities. Subgroup analyses were performed to evaluate the effect of changing definitions of NDI on the primary outcome.

Finally, we planned to evaluate the effect of “Earlier” versus “Later” tracheostomy on outcome. Our database does not include procedure dates, but does indicate whether critical events (such as tracheostomy) occurred before or after 120 days of life. Therefore, we compared outcomes of patients who underwent tracheostomy prior to 120 days of life (“Earlier”) with outcomes of those who underwent tracheostomy at any time between 120 days and follow-up (“Later”).

Analyses were performed with SAS version 9.3 and p<0.05 was considered significant. No adjustments were made for multiple comparisons in this exploratory observational study.

Results

Over the study period (2001-2011), 10,128 children were born before 30 weeks gestation, survived to at least 36 weeks postmenstrual age, and were eligible for neonatal follow-up at 18-22 months corrected age in 16 NRN centers. We excluded 1,445 (14%) children because of missing data on the primary outcome, of whom 29 (2.0%) had tracheostomies. The remaining 8,683 children included 304 children (3.5%) with tracheostomies (Table I). Infants who underwent tracheostomy had lower average birth weight and gestational age and were more likely to be male and have a congenital anomaly. Infants with tracheostomies had higher incidence of all in-hospital morbidities than those without tracheostomies (Table I). There was no significant change in incidence of tracheostomy over the 10 years of this study (Wald χ2 p=0.29). The proportion of children undergoing tracheostomy varied significantly across the 16 participating centers from 1% to 10% (Wald χ2 p<0.001), likely reflecting differing referral and practice patterns. The average corrected age at which developmental testing was performed in survivors was the same in the two groups [median 19 months, interquartile range (16-22), p=0.27].

Table 1.

Demographics and medical morbidities in infants with and without tracheostomies

| Tracheostomy | No tracheostomy | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neonatal and Maternal Demographics | |||

| Male | 169/304 (56) | 4031/8379 (48) | 0.010 |

| Gestational age, weeks | 25 [2] | 26 [2] | < 0.001 |

| Birth weight, grams | 717 [201] | 790 [223] | < 0.001 |

| Antenatal steroids | 244/303 (81) | 6984/8345 (84) | 0.144 |

| 1-minute Apgar 0-3 | 127/299 (42) | 3137/8296 (38) | 0.103 |

| 5-minute Apgar 0-3 | 36/300 (12) | 719/8298 (9) | 0.045 |

| Born outside study center | 26/304 (9) | 718/8379 (9) | 0.992 |

| Syndromes and/or major malformations | 18/304 (6) | 198/8379 (2) | < 0.001 |

| Race | |||

| Black | 130/303 (43) | 3644/8371 (44) | |

| White | 121/303 (40) | 3021/8371 (36) | 0.183 |

| Hispanic | 47/303 (16) | 1396/8371 (17) | |

| Other | 5/303 (2) | 310/8371 (4) | |

| Highest level of maternal education | |||

| Less than high school | 83/286 (29) | 2132/8061 (26) | 0.264 |

| High school | 92/286 (32) | 2409/8061 (30) | |

| College | 111/286 (39) | 3520/8061 (44) | |

| Neonatal Morbidities | |||

| Necrotizing enterocolitis | 41/303 (14) | 836/8378 (10) | 0.044 |

| Brain injury | 79/304 (26) | 1304/8360 (16) | < 0.001 |

| Severe retinopathy of prematurity | 133/301 (44) | 1974/8133 (24) | < 0.001 |

| Patent ductus arteriosus ligation | 95/304 (31) | 1377/8377 (16) | < 0.001 |

| Bronchopulmonary dysplasia – oxygen requirement at 36 weeks | 269/304 (88) | 4145/8349 (50) | < 0.001 |

| Sepsis – number of episodes | 1 [2] | 0 [1] | < 0.001 |

Data are displayed as n/N (%) or median [interquartile range].

Denominators may not be equal because of missing data.

Primary Outcome

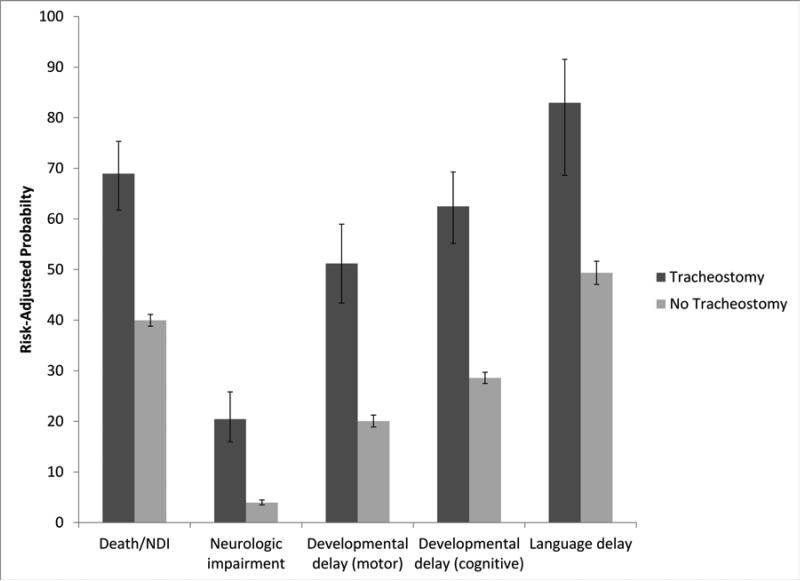

Children with tracheostomies had significantly higher risk of the primary composite outcome of death or NDI and of all of the components of NDI (Table II) than children without tracheostomies. In an attempt to adjust for risk factors other than tracheostomy, we performed pre-specified analyses adjusted for 15 factors. Each of these is known to be associated with both risk for tracheostomy and risk for adverse neurodevelopmental outcomes, as described above. After adjustment, prevalence of the primary outcome of death or NDI, NDI, and the components of NDI remained substantially higher in children with tracheostomies than in those without tracheostomies (Table II). The “fully adjusted” odds ratio (OR) of death or NDI in children with tracheostomies, compared with those without, was 3.3 (95% CI, 2.4-4.6), and the fully adjusted odds ratio of NDI in survivors with tracheostomies, compared to those without, was 4.0 (95% CI, 2.9-5.5). The Figure summarizes graphically the elevated risk-adjusted probabilities of adverse outcomes in children with tracheostomies compared with those without tracheostomies.

Table 2.

Primary outcome of death or neurodevelopmental impairment (NDI) in children with and without tracheostomies

| Tracheostomy n=304 | No tracheostomy n=8,379 | OR Adjusted for Center Only (95% CI) | OR Adjusted for Predictors and Centerc (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Death or NDIa | 251/304 (83) | 3378/8379 (40) | 7.0 (5.2, 9.5) | 3.3 (2.4, 4.6) |

| Death after 36 weeks | 25/304 (8) | 566/8379 (7) | 1.2 (0.8, 1.9) | 0.4 (0.3, 0.7) |

| NDIa | 226/279 (81) | 2812/7813 (36) | 7.7 (5.6, 10.4) | 4.0 (2.9, 5.5) |

| Components of NDI | ||||

| Developmental delay (any definition)a,b | 225/267 (84) | 2749/6790 (40) | 8.1 (5.8, 11.3) | 4.2 (2.9, 6.0) |

| Cognitive delaya | 213/278 (77) | 2374/7797 (30) | 7.6 (5.7, 10.1) | 4.2 (3.1, 5.7) |

| Bayley-II MDI <70a | 76% | 31% | ||

| Bayley-III Cognitive <85a | 79% | 28% | ||

| Motor delaya | 159/233 (68) | 1407/6368 (22) | 7.8 (5.8, 10.4) | 4.2 (3.0, 5.8) |

| Bayley-II PDI <70a | 65% | 21% | ||

| Bayley-III Motor <85a | 85% | 29% | ||

| Neurologic impairment (any definition)a | 124/278 (45) | 532/7806 (7) | 10.9 (8.4, 14.2) | 6.3 (4.6, 8.5) |

| GMFCS level 2 or highera | 41% | 6% | ||

| Moderate or severe cerebral palsya | 32% | 6% | ||

| Vision impairmenta | 12/278 (4) | 48/7806 (1) | 6.6 (3.3, 13.0) | 2.7 (1.3, 5.6) |

| Hearing impairmenta | 22/277 (8) | 126/7792 (2) | 4.7 (2.9, 7.6) | 2.5 (1.5, 4.2) |

Data are displayed as n/N (%) or %.

Bivariate comparison p<0.001.

Children born before 1/1/2006 were tested with the Bayley-II, and children born after 1/1/2006 were tested with the Bayley-III. Expected mean score on the Bayley test is 100, with standard deviation of 15 points.

Odds ratio was adjusted for center, birth weight, sex, race, time period, antenatal steroids, BPD, prolonged ventilation, syndromes and/or major malformations, PDA ligation, sepsis, brain injury, NEC, and severe ROP.

Figure. Risk-Adjusted Probabilities of Components of Neurodevelopmental Impairment and Bayley Scales of Infant Development, by Tracheostomy.

Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals for risk-adjusted probabilities. Probabilities were adjusted for center, time period, birth weight, sex, antenatal steroid exposure, race, presence of syndromes or major malformations, brain injury, sepsis, NEC, severe ROP, surgical ligation of PDA, BPD (oxygen dependence at 36 weeks) and prolonged ventilation. Language delay is defined as <85 (ie, >1 standard deviation below the expected mean score of 100, on the language scale of the Bayley Scales of Infant Development-III). Neurologic delay is defined as moderate to severe cerebral palsy with GMFCS level of 2 or higher.

After adjusting only for center, there was no difference between the groups in risk of death between 36 weeks postmenstrual age and 18-22 months (Table II). However, in the fully risk-adjusted analyses, mortality was significantly lower in children with tracheostomies. To explore this unexpected result, post-hoc analysis in the full model, suggested that this difference was completely mediated by the inclusion of BPD and prolonged ventilation. One interpretation is that children with BPD who did not have tracheostomies had an increased risk of death.

Secondary Outcomes

Most other secondary developmental outcomes were significantly worse in the children with tracheostomies (Table III). Although tracheostomy is expected to be associated with delays in expressive language, we observed a similar delay in receptive language skills. Only the “problem score” of the BITSEA was similar in the two groups, indicating that 18-22 month old children with tracheostomies are not at increased risk for social-emotional/behavioral problems. Nonetheless, children with tracheostomies appear to have higher risk for delays in social-emotional competence.

Table 3.

Additional neurodevelopmental outcomes of children with and without tracheostomies

| Tracheostomy n=304 | No tracheostomy n=8,379 | OR Adjusted for Center Only (95% CI) | OR Adjusted for Predictors and Centerd (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cognitivec | ||||

| Bayley-III Cognitive <70a | 41/80 (51) | 182/2260 (8) | 11.7 (7.2, 18.9) | 4.9 (2.8, 8.6) |

| Languagec | ||||

| Bayley-III Language <8a | 58/66 (88) | 1087/2224 (49) | 8.3 (3.9, 17.9) | 5.0 (2.2, 11.2) |

| Expressive <7a | 78% | 36% | ||

| Receptive <7a | 70% | 42% | ||

| Bayley-III Language <70a | 46/66 (70) | 385/2224 (17) | 11.4 (6.5, 19.8) | 6.7 (3.6, 12.2) |

| Expressive <4a | 41% | 8% | ||

| Receptive <4a | 24% | 8% | ||

| Social/Emotional | ||||

| BITSEA Competence ≥25%ilea | 62/175 (35) | 1188/6477 (18) | 2.5 (1.8, 3.5) | 1.8 (1.3, 2.6) |

| BITSEA Problem ≥15%ileb | 64/188 (34) | 2319/6548 (35) | 0.9 (0.6, 1.2) | 0.9 (0.6, 1.2) |

Data are displayed as n (%) or %.

Bivariate comparison p<0.001.

Bivariate comparison p=0.01.

Children born before 1/1/2006 were tested with the Bayley-II, and children born after 1/1/2006 were tested with the Bayley-III. Expected mean score on the Bayley test is 100, with standard deviation of 15 points. Expected mean score for the language subscales of the Bayley-III is 10, with standard deviation of 3 points.

Odds ratio was adjusted for center, birth weight, sex, race, time period, antenatal steroids, BPD, prolonged ventilation, syndromes and/or major malformations, PDA ligation, sepsis, brain injury, NEC, and severe ROP.

When definitions of NDI changed from Bayley-II to Bayley-III, there was a statistically significant decrease in the proportion of children who were classified as having NDI; 38% (2205/5803) of children tested with the Bayley-II were classified as having NDI compared with 36% (833/2314) of children tested with the Bayley-III (p=0.019). However, despite this difference, the change in definition of NDI did not reduce the highly significant association between tracheostomy and NDI (p<0.001).

Due to the limitations of our data set, the timing of tracheostomy could only be evaluated by whether it occurred before (“Earlier” n=132) or after (“Later” n=172) 120 days of life. In pre-specified analyses, as compared with all children without tracheostomy, fully adjusted odds ratio of death or NDI for children who underwent Earlier tracheostomy was 2.3 (95% CI, 1.5-3.5), whereas it was 4.7 (95% CI, 2.9-7.4) for children who underwent Later tracheostomy. The fully adjusted odds ratio for death or NDI in children who received Earlier tracheostomy, when compared with those who received Later tracheostomy, was 0.5 (95% CI, 0.3-0.9).

Discussion

This retrospective study of prospectively collected data cannot establish causality, but merely suggest plausible associations. However, this cohort is unique in several ways. We evaluated mortality and neurodevelopmental outcomes at 18-22 months corrected age in children who were born at less than 30 weeks gestation and underwent tracheostomy placement. Prior smaller, mostly single center studies of children with tracheostomies did not include comparison groups without tracheostomies. In contrast, our large data set was collected in a standard protocol at 16 sites over a 10-year period and includes comparison with the larger population of preterm infants without tracheostomies.

In our cohort, tracheostomy was associated with a significantly increased risk for the composite primary outcome of death or NDI. Because of the many known risk factors for adverse developmental outcome and survival in preterms, we performed a number of a-priori risk adjustments. Even after adjusting for 17 factors predictive of adverse outcome, children with tracheostomies still had significantly increased odds of adverse developmental outcomes. Although tracheostomy might itself put children at risk for poor outcomes, such a causal relationship is less likely than a non-causal association between tracheostomy and significantly increased risk for poor outcome. It is more likely that we have not fully controlled for confounding by indication, despite a 17 factor adjustment. It is likely that the need for tracheostomy itself defines a risk for adverse outcome that is not wholly captured by the risk factors included. In other words, tracheostomy may be a marker for risk. These limitations of our statistical models do not change the importance of our results. Clinicians considering a tracheostomy for an individual patient could supplement clinical status and history with these data to help parents grasp potential long term outcomes.

Although only a minority of preterm infants ultimately undergo tracheostomy placement, the paucity of relevant literature makes decisions about this procedure very challenging. Reports of complications following pediatric and infant tracheostomy have almost exclusively described indications, mortality, and airway related complications.(26-31) A few older studies reported intellectual disabilities and language delays in children requiring tracheostomies.(5, 6, 32-34) In 1974, children who received tracheostomies early in life were reported to be “withdrawn in character and of poor academic and recreational standard.”(35) Singer reported developmental outcomes at an average of 5 years in a cohort of 130 infants from 2 hospitals who received tracheostomies before 13 months of age during 1972-82.(6) Twenty-nine percent died before follow-up and 45% of survivors were classified with mental retardation or neurological handicap. In a single-center study of 41 infants with tracheostomies, 83% required tube feedings, 97% had abnormal muscle tone, 36% had cerebral palsy, and 24% required hearing aids at a mean age of 27 months.(7) Among those evaluated after 12 months of age, only 16% had average skills and 68% had significant developmental delays. In a questionnaire-based study of functional status in former very preterm infants with tracheostomies, parents reported deterioration over time, especially in the areas of responsiveness, activity, and interpersonal functioning.(36) Finally, a recent single-center series reported that 64% of 165 children with tracheostomies had “some degree of developmental delay,” without defining “delay” or describing when or how these delays were identified.(8) We undertook the current study because these existing series cannot be generalized beyond their centers, have not adjusted for any of the known confounders of neurodevelopmental outcome in this population, and do not contain comparisons with children without this major complication of prematurity. Our results support prior reports of high risk for adverse outcomes in this population, even after consideration of multiple factors that put children at risk for poor long-term outcomes. This study also provides estimates of the prevalence of these outcomes in preterm children with tracheostomies. The 8% mortality that we report is lower than the mortality reported in older studies, which report mortality as high as 59%.(2, 3, 30, 37)

Our results suggest a possible association between Earlier (<120 days) tracheostomy and better neurodevelopmental outcomes. This result supports the work of several authors who have recently suggested that, in older children and adults, tracheostomy placement should be performed as soon as possible.(8, 38, 39) We speculate that while an infant awaits a tracheostomy, the medical focus is often on strategies to enable weaning and limit ventilator-associated lung injury. Following a tracheostomy, the focus may shift to maximizing parent-child interaction and developmental enrichment. Furthermore, there is often opportunity to wean off of sedating medications, which may be associated with increased risk of NDI, after tracheostomy.(40) Importantly, severity of illness, indication for tracheostomy, anesthetic exposure, or other factors could have influenced either the timing of tracheostomy or developmental outcomes, leading to potential for bias. Therefore, prospective confirmation of this temporal relationship is essential before clinicians can confidently counsel parents toward earlier decisions about tracheostomy placement.

Long-term ventilation secondary to BPD is the most common indication for tracheostomy in preterm infants.(5, 11, 12) Both the presence and the severity of BPD strongly influence neurodevelopmental outcomes.(24) Because data for the “physiologic definition” of BPD were not available for the majority of patients in the current study, we instead used oxygen dependence at 36 weeks and prolonged mechanical ventilation as markers of the presence and severity of lung disease.(41, 42) As expected, poor outcomes were strongly correlated with both of these measures. Unexpectedly, the observed differences in the fully adjusted odds of mortality after 36 weeks were strongly associated with death of children with BPD who did not undergo tracheostomy. As discussed above, it remains possible that we have not adequately controlled for the impact of lung disease on long-term outcomes, or that clinicians offered therapy selectively. Nonetheless, because the majority of infants who undergo tracheostomy have severe BPD, our results remain relevant and applicable to these children.

Comparing neurodevelopmental outcomes in children who were tested with different editions of the Bayley Scales of Infant Development is a recent challenge in neonatal follow-up.(18, 19) We decided a priori to use the existing NRN definitions of NDI, recognizing that the different tests and definitions might capture slightly different outcomes. However, both the proportion of children who were diagnosed with NDI and the association of tracheostomy with NDI were relatively consistent over time. An additional limitation of using the Bayley Scales of Infant Development at 18-22 months is the increased recognition that assessments at this early time point do not predict school age functioning, except perhaps in the most severely affected children.(43-47) Many children classified as mildly-moderately impaired as toddlers demonstrate gains in cognitive performance when re-evaluated at older ages.(43, 44) Unfortunately, data about school-age outcomes are not available for this or any other large cohort of children with tracheostomies.

We acknowledge several additional limitations of this large observational study. Firstly, attrition bias is possible because we are unable to ascertain the primary outcome in 14% of eligible children and attrition was higher among children without tracheostomies. Selection bias may have been introduced either by clinical decisions about which infants received tracheostomies or by the inclusion of only survivors to 36 weeks in the current study. Lastly, we emphasize again that we can only describe an association between the need for tracheostomy and adverse outcomes. The child who ultimately requires tracheostomy placement will have accumulated multiple risk factors for adverse outcome, some of which we were able to include in our analyses and some of which must be considered unmeasured confounders. Thus, the need for tracheostomy must suggest to clinicians that a patient's severity of illness puts that patient at extremely high risk for adverse long-term outcomes.

In conclusion, this is the first large, multicenter study to describe the long-term neurodevelopmental outcomes of preterm infants with tracheostomies with comparison with the general preterm population. Tracheostomy does not mitigate the significant risk for adverse neurodevelopment that is associated with multiple neonatal morbidities, major malformations, or severe BPD. However, if tracheostomy is to be performed, earlier surgery may allow opportunities for enhanced neurodevelopment. Information about the association between tracheostomy placement and outcomes in this population may facilitate a shared decision-making process between parents and clinicians about whether and when to pursue tracheostomy placement.

Acknowledgments

We are indebted to our medical and nursing colleagues and the infants and their parents who took part in this study.

Supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health and the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) for the Neonatal Research Network, including for the Generic Database Study, Candidiasis Study, Cord Clamping Study, Delivery Room CPAP Study, Early Blood Pressure pilot study, PCV-7 Study, Phototherapy Trial, Preemie aEEG pilot study, Preemie iNO Trial, and SUPPORT trial. Data collected at participating sites of the NICHD Neonatal Research Network were transmitted to RTI International, the data coordinating center for the network, which stored, managed and analyzed the data for this study.

Abbreviations

- BITSEA

Brief Infant/Toddler Social and Emotional Assessment

- BPD

bronchopulmonary dysplasia

- NDI

neurodevelopmental impairment

- OR

odds ratio

Appendix

The following investigators, in addition to those listed as authors, are members of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Neonatal Research Network:

NRN Steering Committee Chairs: Alan H. Jobe, MD PhD, University of Cincinnati (2003-2006); Michael S. Caplan, MD, University of Chicago, Pritzker School of Medicine (2006-2011). Alpert Medical School of Brown University and Women & Infants Hospital of Rhode Island (U10 HD27904) – Abbot R. Laptook, MD; William Oh, MD; Robert T. Burke, MD MPH; Bonnie E. Stephens, MD; Yvette Yatchmink, MD; Barbara Alksninis, RNC PNP; Dawn Andrews, RN MS; KristenAngela, RN; Angelita M. Hensman, RN BSN; Teresa M. Leach, MEd CAES; Martha R. Leonard, BA BS; Lucy Noel; Suzy Ventura; Rachel A. Vogt, MD; Victoria E. Watson, MS CAS.

Case Western Reserve University, Rainbow Babies & Children's Hospital (U10 HD21364, M01 RR80) – Michele C. Walsh, MD MS; Avroy A. Fanaroff, MD; Nancy S. Newman, RN; Deanne E. Wilson-Costello, MD; Bonnie S. Siner, RN; Harriet G. Friedman, MA. Children's Mercy Hospital (U10 HD68284) – William E. Truog, MD.

Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center, University Hospital, and Good Samaritan Hospital (U10 HD27853, M01 RR8084, UL1 TR77) – Kurt Schibler, MD; Edward F. Donovan, MD; Kate Bridges, MD; Jean J. Steichen, MD; Kimberly Yolton, PhD; Barbara Alexander, RN; Estelle E. Fischer, MHSA MBA; Cathy Grisby, BSN CCRC; Marcia Worley Mersmann, RN; Holly L. Mincey, RN BSN; JodyHessling, RN; Teresa L. Gratton, PA;Lenora Jackson; Kristin Kirker.

Duke University School of Medicine, University Hospital, University of North Carolina, Alamance Regional Medical Center, and Durham Regional Hospital (U10 HD40492, UL1 RR24128, M01 RR30, UL1 RR25747) – Ronald N. Goldberg, MD; C. Michael Cotten, MD MHS; Ricki F. Goldstein, MD; Matthew M. Laughon, MD MPH; Kathy J. Auten, MSHS; Kimberley A. Fisher, PhD FNP-BC IBCLC; Katherine A. Foy, RN; Kathryn E. Gustafson, PhD; Melody B. Lohmeyer, RN MSN. Emory University, Children's Healthcare of Atlanta, Grady Memorial Hospital, and Emory University Hospital Midtown (U10 HD27851, M01 RR39, UL1 TR454) – David P. Carlton, MD; Ira Adams-Chapman, MD; Ellen C. Hale, RN BS CCRC. Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development–Linda L. Wright, MD; Elizabeth M. McClure, MEd; Stephanie Wilson Archer, MA.

Indiana University, University Hospital, Methodist Hospital, Riley Hospital for Children, and Wishard Health Services (U10 HD27856, M01 RR750, UL1 TR6) – James A. Lemons, MD; Anna M. Dusick, MD; Carolyn Lytle, MD MPH; Lon G. Bohnke, MS; Greg Eaken, PhD; Faithe Hamer, BS; Dianne E. Herron, RN; Lucy C. Miller, RN BSN CCRC; Heike M. Minnich, PsyD HSPP; Leslie Richard, RN; Leslie Dawn Wilson, BSN CCRC.

Nationwide Children's Hospital and the Ohio State University Medical Center (U10 HD68278) – Leif D. Nelin, MD; RTI International (U10 HD36790) – W. Kenneth Poole, PhD; Dennis Wallace, PhD; Jamie E. Newman, PhD MPH; Jeanette O'Donnell Auman, BS; Margaret Cunningham, BS; Betty K. Hastings; Elizabeth M. McClure, MEd; Carolyn M. Petrie Huitema, MS; Kristin M. Zaterka-Baxter, RN BSN.

Stanford University, California Pacific Medical Center, Dominican Hospital, El Camino Hospital, and Lucile Packard Children's Hospital (U10 HD27880, M01 RR70, UL1 TR93) – Krisa P. Van Meurs, MD; David K. Stevenson, MD; Marian M. Adams, MD; Charles E. Ahlfors, MD; M. Bethany Ball, BS CCRC; Joan M. Baran, PhD; Barbara Bentley, PhD; Lori E. Bond, PhD; Ginger K. Brudos, PhD; Alexis S. Davis, MD MS; Maria Elena DeAnda, PhD; Anne M. DeBattista, RN PNP; Jan T. Epcar, MA; Barry E. Fleisher, MD; Magdy Ismael, MD MPH; Jean G. Kohn, MD MPH; Carol G. Kuelper, PhD; Julie C. Lee-Ancajas, PhD; Andrew W. Palmquist, RN; Melinda S. Proud, RCP; Renee P. Pyle, PhD; DharshiSivakumar, MD; Robert D. Stebbins, MD; Nicholas H. St. John, PhD.

University of Alabama at Birmingham Health System and Children's Hospital of Alabama (U10 HD34216, M01 RR32) – Waldemar A. Carlo, MD; Namasivayam Ambalavanan, MD; Myriam Peralta-Carcelen, MD MPH; Kathleen G. Nelson, MD; Kirstin J. Bailey, PhD; Fred J. Biasini, PhD; Stephanie A. Chopko, PhD; Monica V. Collins, RN BSN MaEd; Shirley S. Cosby, RN BSN; Mary Beth Moses, PT MS PCS; Vivien A. Phillips, RN BSN; Julie Preskitt, MSOT MPH; Richard V. Rector, PhD; Sally Whitley, MA OTR-L FAOTA.

University of California – San Diego Medical Center and Sharp Mary Birch Hospital for Women and Newborns (U10 HD40461) – Neil N. Finer, MD; Maynard R. Rasmussen MD; Yvonne E. Vaucher, MD MPH; Paul R. Wozniak, MD; Kathy Arnell, RNC; Renee Bridge, RN; Clarence Demetrio, RN; Martha G. Fuller, RN MSN; Donna Posin, OTR/L MPA; Wade Rich, BSHS RRT.

University of Miami, Holtz Children's Hospital (U10 HD21397, M01 RR16587) – Charles R. Bauer, MD; Shahnaz Duara, MD; Ruth Everett-Thomas, RN MSN; Amy Mur Worth, RN MS; Mary Allison, RN; Alexis N. Diaz, BA; Elaine O. Mathews, RN; Kasey Hamlin-Smith, PhD; Lisa Jean-Gilles, BA; Maria Calejo, MS; Silvia M. FradeEguaras, BA; Silvia Hiriart-Fajardo, MD; Yamiley C. Gideon, BA; Michelle Berkovits, PhD; Alexandra Stoerger, BA; Andrea Garcia, MA; Helena Pierre, BA.

University of Pennsylvania, Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, Pennsylvania Hospital, and Children's Hospital of Philadelphia (U10 HD68244) – Barbara Schmidt, MD.

University of Rochester Medical Center, Golisano Children's Hospital (U10 HD40521, M01 RR44, UL1 TR42) – Dale L. Phelps, MD; Ronnie Guillet, MD PhD; Gary J. Myers, MD; Linda J. Reubens, RN CCRC, Erica Burnell, RN; Mary Rowan, RN; Cassandra A. Horihan, MS; Julie Babish Johnson, MSW; Diane Hust, MS RN CS; Rosemary L. Jensen; Emily Kushner, MA; Joan Merzbach, LMSW; Kelly Yost, PhD; Lauren Zwetsch, RN MS PNP.

University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center at Dallas, Parkland Health & Hospital System and Children's Medical Center Dallas (U10 HD40689, M01 RR633) – Abbot R. Laptook, MD; Charles R. Rosenfeld, MD; Walid A. Salhab, MD; Luc P. Brion, MD; R. Sue Broyles, MD; Roy J. Heyne, MD; Sally S. Adams, MS RN CPNP; P. Jeannette Burchfield, RN BSN; Cristin Dooley, PhD LSSP; Alicia Guzman; Gaynelle Hensley, RN; Elizabeth Heyne, PsyD PA-C; Jackie F. Hickman, RN; Melissa H. Leps, RN; Linda A. Madden, BSN RN CPNP; Nancy A. Miller, RN; Janet S. Morgan, RN; Susie Madison, RN; Lizette E. Torres, RN; Cathy Twell Boatman, MS CIMI; Diana M. Vasil, RNC-NIC.

University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston Medical School, Children's Memorial Hermann Hospital, and Lyndon Baines Johnson General Hospital/Harris County Hospital District (U10 HD21373) – Kathleen A. Kennedy, MD MPH; Jon E. Tyson, MD MPH; Pamela J. Bradt, MD MPH; Patricia W. Evans, MD; Esther G. Akpa, RN BSN; Nora I. Alaniz, BS; Magda Cedillo Guajardo, RB BSN FAACM; Susan E. Dieterich, PhD; Beverly Foley Harris, RN BSN; Claudia I. Franco, RNC MSN; Charles Green, PhD; Margarita Jiminez, MD MPH; Anna E. Lis, RN BSN; Terri Major-Kincade, MD MPH; Sara C. Martin, RN BSN; Georgia E. McDavid, RN; Brenda H. Morris, MD; Patricia Ann Orekoya, RNBSN; Patti L. Pierce Tate, RCP; M. Layne Poundstone, RN BSN; Stacey Reddoch, BA; Saba Khan Siddiki, MD; Maegan C. Simmons, RN; Laura L. Whitely, MD; Sharon L. Wright, MT.

Wake Forest University Baptist Medical Center, Brenner Children's Hospital, and Forsyth Medical Center (U10 HD40498, M01 RR7122) – T. Michael O'Shea, MD MPH; Robert G. Dillard, MD; Nancy J. Peters, RN CCRP;Korinne Chiu, MA; Deborah Evans Allred, MA LPA; Donald J. Goldstein, PhD; Raquel Halfond, MA; Barbara G. Jackson, RN BSN; Carroll Peterson, MA; Ellen L. Waldrep, MS; Melissa Whalen Morris, MA; Gail Wiley Hounshell, PhD. Wayne State University, Hutzel Women's Hospital, and Children's Hospital of Michigan (U10 HD21385) – Beena G. Sood, MD MS; Athina Pappas, MD; Yvette R. Johnson, MD MPH; Rebecca Bara, RN BSN; Debra Driscoll, RN BSN; Laura Goldston, MA; Mary E. Johnson, RN BSN; Deborah Kennedy, RN BSN; Geraldine Muran, RN BSN; Elizabeth Billian, RN MS; Laura Sumner, RN BSN; Kara Sawaya, RN BSN; Kathleen Weingarden, RN BSN.

Yale University, Yale-New Haven Children's Hospital, and Bridgeport Hospital (U10 HD27871, M01 RR125, M01 RR6022, UL1 TR142) – Richard A. Ehrenkranz, MD; Christine Butler, MD; Harris Jacobs, MD; Patricia Cervone, RN; Nancy Close, PhD; Patricia Gettner, RN; Walter Gilliam, PhD; Sheila Greisman, RN; Monica Konstantino, RN BSN; JoAnn Poulsen, RN; Elaine Romano, MSN; Janet Taft, RN BSN; Joanne Williams, RN BSN.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Contributor Information

Sara B. DeMauro, The Children's Hospital of Philadelphia and The University of Pennsylvania; DeMauro@email.chop.edu.

Jo Ann D'Agostino, The Children's Hospital of Philadelphia; dagostino@email.chop.edu.

Carla Bann, Research Triangle Institute; cmb@rti.org.

Judy Bernbaum, The Children's Hospital of Philadelphia and The University of Pennsylvania; Bernbaum@email.chop.edu.

Marsha Gerdes, The Children's Hospital of Philadelphia and The University of Pennsylvania; Gerdes@email.chop.edu.

Edward F. Bell, University of Iowa; edward-bell@uiowa.edu.

Waldemar A. Carlo, University of Alabama; wcarlo@peds.uab.edu.

Carl D'Angio, The University of Rochester; Carl_Dangio@URMC.Rochester.edu.

Abhik Das, Research Triangle Institute; adas@rti.org.

Rosemary Higgins, Eunice Kennedy Shriver NICHD Neonatal Research Network; higginsr@mail.nih.gov.

Susan R. Hintz, Stanford University School of Medicine; srhintz@stanford.edu.

Abbot R. Laptook, Brown University; alaptook@wihri.org.

Girija Natarajan, Wayne State University School of Medicine; gnatara@med.wayne.edu.

Leif Nelin, The Ohio State University and Nationwide Children's Hospital; leif.nelin@nationwidechildrens.org.

Brenda B. Poindexter, Indiana University; bpoindex@iupui.edu.

Pablo J. Sanchez, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center; Pablo.Sanchez@UTSouthwestern.edu.

Seetha Shankaran, Wayne State University School of Medicine; sshankar@med.wayne.edu.

Barbara J. Stoll, Emory University School of Medicine and Children's Healthcare of Atlanta; Barbara.Stoll@oz.ped.emory.edu.

William Truog, Children's Mercy Hospital; wtruog@cmh.edu.

Krisa P. Van Meurs, Stanford University; vanmeurs@stanford.edu.

Betty Vohr, Brown University; BVohr@wihri.org.

Michele C. Walsh, Rainbow Babies & Children's Hospital, Case Western Reserve University; michele.walsh@cwru.edu.

Haresh Kirpalani, The Children's Hospital of Philadelphia and The University of Pennsylvania; Kirpalanih@email.chop.edu.

References

- 1.Lewis CW, Carron JD, Perkins JA, Sie KC, Feudtner C. Tracheotomy in pediatric patients: a national perspective. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2003;129:523–9. doi: 10.1001/archotol.129.5.523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Edwards JD, Kun SS, Keens TG. Outcomes and causes of death in children on home mechanical ventilation via tracheostomy: an institutional and literature review. J Pediatr. 2010;157:955–9. e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2010.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Graf JM, Montagnino BA, Hueckel R, McPherson ML. Pediatric tracheostomies: a recent experience from one academic center. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2008;9:96–100. doi: 10.1097/01.PCC.0000298641.84257.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kremer B, Botos-Kremer AI, Eckel HE, Schlondorff G. Indications, complications, and surgical techniques for pediatric tracheostomies--an update. J Pediatr Surg. 2002;37:1556–62. doi: 10.1053/jpsu.2002.36184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sisk EA, Kim TB, Schumacher R, Dechert R, Driver L, Ramsey AM, et al. Tracheotomy in very low birth weight neonates: indications and outcomes. Laryngoscope. 2006;116:928–33. doi: 10.1097/01.MLG.0000214897.08822.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Singer LT, Kercsmar C, Legris G, Orlowski JP, Hill BP, Doershuk C. Developmental sequelae of long-term infant tracheostomy. Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology. 1989;31:224–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.1989.tb03982.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.D'Agostino J, Gerdes M, Wade K, Calvert D, Bernbaum J. Medical and Neurodevelopmental Outcome of Infants Discharged with Tracheostomies.. 2008 meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies; Hawaii. 2008; Abstract 6125.4. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Overman AE, Liu M, Kurachek SC, Shreve MR, Maynard RC, Mammel MC, et al. Tracheostomy for Infants Requiring Prolonged Mechanical Ventilation: 10 Years' Experience. Pediatrics. 2013;131:e1491–6. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-1943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schmidt B, Asztalos EV, Roberts RS, Robertson CM, Sauve RS, Whitfield MF. Impact of bronchopulmonary dysplasia, brain injury, and severe retinopathy on the outcome of extremely low-birth-weight infants at 18 months: results from the trial of indomethacin prophylaxis in preterms. JAMA. 2003;289:1124–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.9.1124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Singer L, Yamashita T, Lilien L, Collin M, Baley J. A longitudinal study of developmental outcome of infants with bronchopulmonary dysplasia and very low birth weight. Pediatrics. 1997;100:987–93. doi: 10.1542/peds.100.6.987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pereira KD, MacGregor AR, McDuffie CM, Mitchell RB. Tracheostomy in preterm infants: current trends. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2003;129:1268–71. doi: 10.1001/archotol.129.12.1268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pereira KD, MacGregor AR, Mitchell RB. Complications of neonatal tracheostomy: a 5-year review. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2004;131:810–3. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2004.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stoll BJ, Hansen NI, Bell EF, Shankaran S, Laptook AR, Walsh MC, et al. Neonatal outcomes of extremely preterm infants from the NICHD Neonatal Research Network. Pediatrics. 2010;126:443–56. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-2959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hintz SR, Kendrick DE, Vohr BR, Poole WK, Higgins RD. Changes in neurodevelopmental outcomes at 18 to 22 months' corrected age among infants of less than 25 weeks' gestational age born in 1993-1999. Pediatrics. 2005;115:1645–51. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-2215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schmidt B, Roberts RS, Davis P, Doyle LW, Barrington KJ, Ohlsson A, et al. Long-term effects of caffeine therapy for apnea of prematurity. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:1893–902. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa073679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bayley N. Bayley Scales of Infant Development. 2nd edition Psychological Corp.; San Antonio, TX: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bayley N. Bayley Scales of Infant and Toddler Development. Psychological Corp.; San Antonio, TX: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vohr BR, Stephens BE, Higgins RD, Bann CM, Hintz SR, Das A, et al. Are outcomes of extremely preterm infants improving? Impact of Bayley assessment on outcomes. J Pediatr. 2012;161:222–8. e3. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2012.01.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Anderson PJ, De Luca CR, Hutchinson E, Roberts G, Doyle LW. Underestimation of developmental delay by the new Bayley-III Scale. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2010;164:352–6. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2010.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Palisano R, Rosenbaum P, Walter S, Russell D, Wood E, Galuppi B. Development and reliability of a system to classify gross motor function in children with cerebral palsy. Dev Med Child Neurol. 1997;39:214–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.1997.tb07414.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Briggs-Gowan MJ, Carter AS, Irwin JR, Wachtel K, Cicchetti DV. The Brief Infant-Toddler Social and Emotional Assessment: screening for social-emotional problems and delays in competence. J Pediatr Psychol. 2004;29:143–55. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsh017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Karabekiroglu K, Briggs-Gowan MJ, Carter AS, Rodopman-Arman A, Akbas S. The clinical validity and reliability of the Brief Infant-Toddler Social and Emotional Assessment (BITSEA). Infant Behav Dev. 2010;33:503–9. doi: 10.1016/j.infbeh.2010.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Natarajan G, Pappas A, Shankaran S, Kendrick DE, Das A, Higgins RD, et al. Outcomes of extremely low birth weight infants with bronchopulmonary dysplasia: Impact of the physiologic definition. Early Hum Dev. 2012;88:509–15. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2011.12.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Walsh MC, Morris BH, Wrage LA, Vohr BR, Poole WK, Tyson JE, et al. Extremely low birthweight neonates with protracted ventilation: mortality and 18-month neurodevelopmental outcomes. J Pediatr. 2005;146:798–804. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2005.01.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bell MJ, Ternberg JL, Feigin RD, Keating JP, Marshall R, Barton L, et al. Neonatal necrotizing enterocolitis. Therapeutic decisions based upon clinical staging. Ann Surg. 1978;187:1–7. doi: 10.1097/00000658-197801000-00001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Parrilla C, Scarano E, Guidi ML, Galli J, Paludetti G. Current trends in paediatric tracheostomies. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2007;71:1563–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2007.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Corbett HJ, Mann KS, Mitra I, Jesudason EC, Losty PD, Clarke RW. Tracheostomy--a 10-year experience from a UK pediatric surgical center. J Pediatr Surg. 2007;42:1251–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2007.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Alladi A, Rao S, Das K, Charles AR, D'Cruz AJ. Pediatric tracheostomy: a 13-year experience. Pediatr Surg Int. 2004;20:695–8. doi: 10.1007/s00383-004-1277-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tantinikorn W, Alper CM, Bluestone CD, Casselbrant ML. Outcome in pediatric tracheotomy. Am J Otolaryngol. 2003;24:131–7. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0709(03)00009-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zenk J, Fyrmpas G, Zimmermann T, Koch M, Constantinidis J, Iro H. Tracheostomy in young patients: indications and long-term outcome. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2009;266:705–11. doi: 10.1007/s00405-008-0796-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mandy G, Malkar M, Welty SE, Brown R, Shepherd E, Gardner W, et al. Tracheostomy placement in infants with bronchopulmonary dysplasia: Safety and outcomes. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2013;48:245–9. doi: 10.1002/ppul.22572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ross G. Language functioning and speech development of six children receiving tracheotomy in infancy. Journal of Communication Disorders. 1982;15:95–111. doi: 10.1016/0021-9924(82)90024-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Simon BM, Fowler SM, Handler SD. Communication development in young children with long-term tracheostomies: preliminary report. International Journal of Pediatric Otorhinolaryngology. 1983;6:37–50. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5876(83)80102-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jiang D, Morrison GAJ. The influence of long-term tracheostomy on speech and language development in children. International Journal of Pediatric Otorhinolaryngology. 2003;67S1:S217–S20. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2003.08.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Freeland AP, Wright JL, Ardran GM. Developmental influences of infant tracheostomy. J Laryngol Otol. 1974;88:927–36. doi: 10.1017/s0022215100079585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rane S, Shankaran S, Natarajan G. Parental perception of functional status following tracheostomy in infancy: a single center study. J Pediatr. 2013;163:860–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2013.03.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ilce Z, Celayir S, Tekand GT, Murat NS, Erdogan E, Yeker D. Tracheostomy in childhood: 20 years experience from a pediatric surgery clinic. Pediatr Int. 2002;44:306–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1442-200x.2002.01554.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mok Q. Tracheostomies in paediatric intensive care: evolving indications and changing expectations. Archives of Disease in Childhood. 2012;97:858–9. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2012-302454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Scales DC, Thiruchelvam D, Kiss A, Redelmeier DA. The effect of tracheostomy timing during critical illness on long-term survival. Crit Care Med. 2008;36:2547–57. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31818444a5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Davidson A, Soriano S. Does anaesthesia harm the developing brain--evidence or speculation? Paediatr Anaesth. 2004;14:199–200. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9592.2003.01140.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Walsh MC, Wilson-Costello D, Zadell A, Newman N, Fanaroff A. Safety, reliability, and validity of a physiologic definition of bronchopulmonary dysplasia. J Perinatol. 2003;23:451–6. doi: 10.1038/sj.jp.7210963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Walsh MC, Yao Q, Gettner P, Hale E, Collins M, Hensman A, et al. Impact of a physiologic definition on bronchopulmonary dysplasia rates. Pediatrics. 2004;114:1305–11. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-0204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hack M, Taylor HG, Drotar D, Schluchter M, Cartar L, Wilson-Costello D, et al. Poor predictive validity of the Bayley Scales of Infant Development for cognitive function of extremely low birth weight children at school age. Pediatrics. 2005;116:333–41. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-0173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schmidt B, Anderson PJ, Doyle LW, Dewey D, Grunau RE, Asztalos EV, et al. Survival without disability to age 5 years after neonatal caffeine therapy for apnea of prematurity. JAMA. 2012;307:275–82. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.2024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Msall ME. Neurodevelopmental surveillance in the first 2 years after extremely preterm birth: evidence, challenges, and guidelines. Early Hum Dev. 2006;82:157–66. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2005.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Koller H, Lawson K, Rose SA, Wallace I, McCarton C. Patterns of cognitive development in very low birth weight children during the first six years of life. Pediatrics. 1997;99:383–9. doi: 10.1542/peds.99.3.383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Aylward GP. Neurodevelopmental outcomes of infants born prematurely. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2005;26:427–40. doi: 10.1097/00004703-200512000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]