Abstract

Cardiac metastases are rare, but more common than primary cardiac tumours, and metastatic melanoma involves heart or pericardium in greater than 50% of the cases, although cardiac metastasis are rarely diagnosed ante mortem because of the lack of symptoms. A multimodality approach may help to obtain a more timely diagnosis and in some cases a quicker and better diagnosis can enable a surgical resection to prevent cardiac failure or to reduce the tumour before chemotherapy. We present a case of a patient with cardiac metastasis as first evidence of a malignant melanoma: in this case the patient underwent echocardiography, cardiac magnetic resonance and computed tomography. This case underlines the importance of advanced diagnostic techniques, such as cardiac magnetic resonance, not only for the detection of cardiac masses, but also for a better anatomic definition and tissue characterization, to enable a quick and accurate diagnosis which can be followed by appropriate treatment.

Keywords: Cardiovascular magnetic resonance, computed tomography, metastases, melanoma, cardiac tumours

CASE REPORT

A 61-year-old Caucasian male was admitted to the emergency room of our hospital with shortness of breath and fainting, without chest pain; he did not report any other symptoms. The patient had no relevant past medical history; in particular, no previous cardiac diseases were reported. The physical examination was normal. However, a cutaneous lesion was found in sacral region where some years before a nevus had been resected with a histologic diagnosis of blue nevus without any evidence of mitotic activities or necrotic phenomena.

Imaging findings

Chest X-ray and laboratory tests were normal.

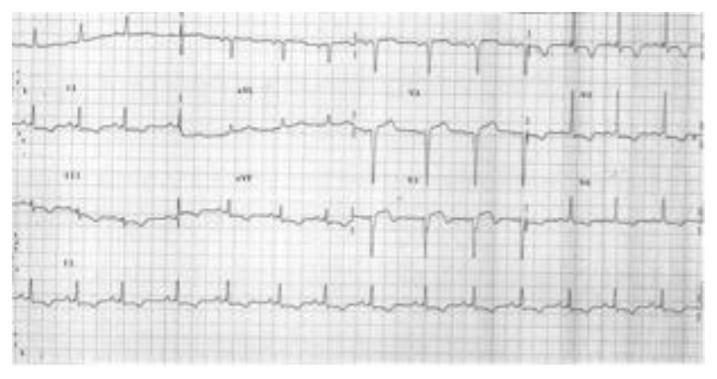

The first electrocardiogram (ECG) showed atrial flutter 2:1. Figure 1 is a following ECG, when the patient was in sinus rhythm, which showed diffused alteration of ventricular repolarization: cardiac hypertrophy and left ventricular (LV) overload were suspected.

Figure 1.

61-year-old male with cardiac metastases of melanoma. ECG shows Q waves in V1 to V3 and diffuse repolarization abnormalities.

Transthoracic and transesophageal echocardiography revealed a normal LV function with what appeared to be a concentric biventricular hypertrophy; interatrial and interventricular septum showed increased thickness and echogenicity and these findings were at first related to hypertrophy. Moreover the echo pointed out the presence of an irregular mass occupying the right atrium (RA), near the superior vena cava (SVC) (fig. 2).

Figure 2.

61 year old male with cardiac metastases of melanoma. Echocardiography, transthoracic cardiac probe, 2–4 MHz, A: 4 chamber transthoracic view, B: parasternal long axis transthoracic view, C: transesophageal echocardiography. The exams show biventricular increased thickness and echogenicity and a rounded mass in the right atrium (arrows).

The patient was referred for cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) in order to assess the suspected myocardial hypertrophy and to characterize the atrial mass. An ECG-gated CMR was performed.

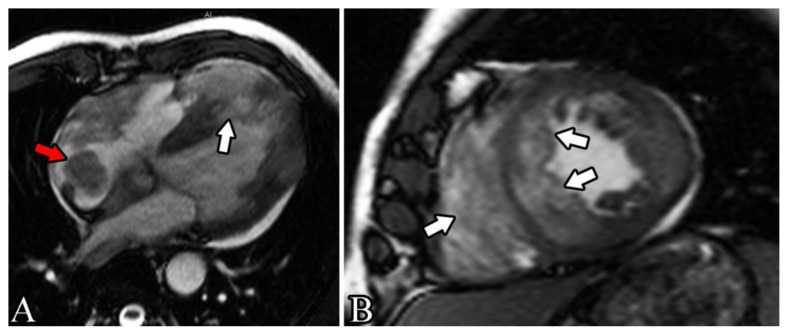

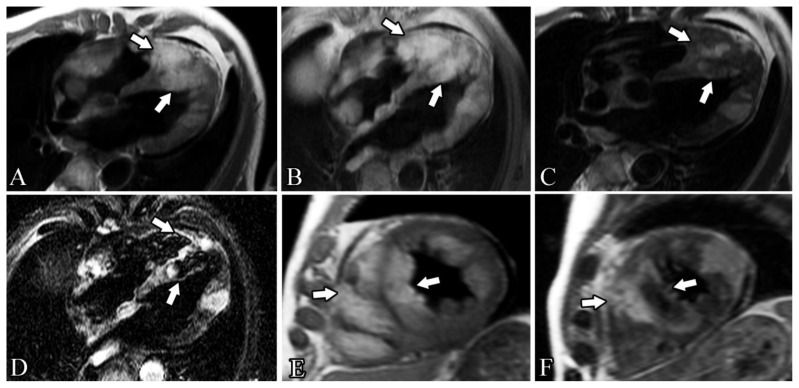

Steady state free procession (SSFP) cine vertical long axis and horizontal short axis demonstrated normal left ventricular contractility. All myocardial walls had an irregular, heterogeneous, thickened appearance, excepted for free left atrium wall; in particular lateral wall, free right ventricular wall and distal interventricular and interatrial septum, were involved by nodular deposits in the myocardial muscle layers with variable penetration into the endocardium and epicardium (fig. 3). The atrial polypoid mass was located in the posterior wall of right atrium, near SVC. The cardiac valves appeared normal. The intramyocardial and right atrial masses showed different intensity, but most of them were hyperintense on both T1 and T2 weighted (T1w and T2w) images (fig. 4). On the late gadolinium enhancement (LGE) sequences, the masses showed a significant contrast uptake (fig. 5). There was a small pericardial effusion, but pericardial layers were disease-free.

Figure 3.

61 year old male with cardiac metastases of melanoma.

Findings: 4 chamber and short axis views cine images show irregular, heterogeneous and thickened appearance of the myocardial wall and several nodular deposits throughout the myocardium, with variable penetration: the biggest lesion has maximum diameters around 45×50 mm, infiltrates the interventricular septum and extends to the right cardiac apex (white arrows).

There is also an atrial polypoid mass in the right atrium (around 19×20 mm)(red arrow), near superior vena cava. The cardiac valves appeared normal.

Technique: cardiac magnetic resonance, 1.5 T MR System (Siemens, Symphony, Germany) with breath-holding technique. A: steady-state free-precession (SSFP) gradient echo (GE) cine image in 4 chamber view before the administration of contrast agent, TE 1.6 ms, TR 48.3 ms. B: steady-state free-precession (SSFP) gradient echo (GE) cine image in short axis view before the administration of contrast agent, TE 1.6 ms, TR 46.8 ms.

Figure 4.

61-year-old male with cardiac metastases of melanoma.

Findings: these various CMR sequences, before the administration of contrast agent, show several intramyocardial masses involving both ventricles and the right atrium and highlight the heterogeneous composition of the masses, even if most of them appear to be hyperintense on both T1 weighted and T2 weighted images. The biggest lesion has maximum diameters around 45×50 mm, infiltrates the interventricular septum and extends to the right cardiac apex (white arrows). The presence of a fat component is confirmed by the loss of signal in the images with fat saturation.

Technique: cardiac magnetic resonance, 1.5 T MR System (Siemens, Symphony, Germany), breath-holding, before the administration of contrast agent.

A: T1 weighted turbo spin-echo, 4-chamber view, TE 7.1 ms, TR 642 ms.

B: T1 weighted turbo spin echo fat sat (FS), 4-chamber view, TE 7.1 ms, TR 669.4 ms.

C: T2 weighted turbo spin echo, 4-chamber view, TE 71 ms, TR 2033 ms.

D: T2 weighted turbo inversion recovery magnitude (TIRM), 4-chamber view, TE: 69 ms, TR 1167.2 ms.

E: T1 weighted turbo spin-echo, short axis view, TE 7.1 ms, TR 671 ms.

F: T2 weighted turbo spin echo, short axis view, TE 71 ms, TR 2135 ms.

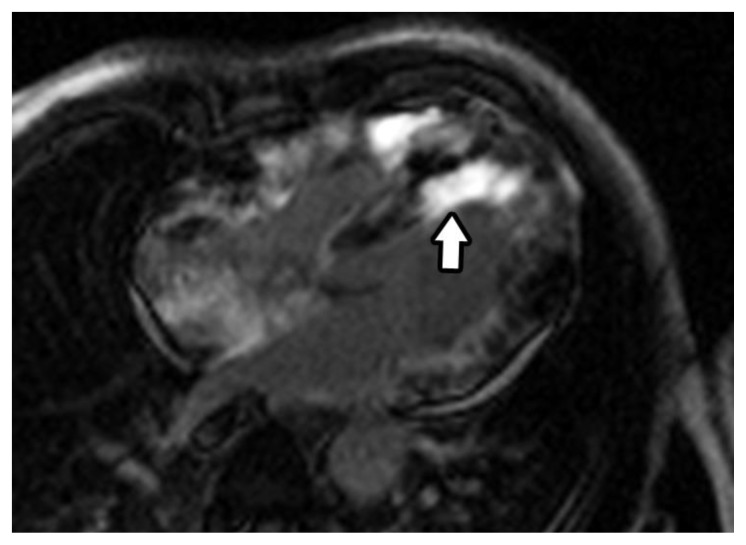

Figure 5.

61 year old male with cardiac metastases of melanoma.

Findings: CMR after the injection of gadolinium clearly shows a inhomogeneous, but diffuse and avid contrast enhancement of almost all the masses previously seen, in particular around the distal part of the interventricular septum (arrow).

Technique: cardiac magnetic resonance, 1.5 T MR System (Siemens, Symphony, Germany), breath-holding, 6 minutes after intravenous injection of 0.15 mmol/kg of Gadolinium contrast agent (gadopentetate dimeglumine, Magnevist), inversion recovery late gadolinium enhancement (LGE) image in 4 chamber view, TE 1.3 ms, TR 500 ms, flip angle 650, IT 255 ms.

In conclusion, the CMR demonstrated the presence of masses in the interatrial septum and in the right atrium and solid tissue infiltrating the ventricular myocardium bilaterally: this tissue showed MRI characteristics of mixed structure.

The multifocal localization correlates more likely with metastases than primary tumour and the myocardial infiltration suggests haematogenous diffusion, so the most likely diagnosis was cardiac metastases or sarcoma.

To study in deep the case and for a likely staging of cancer, a total body computed tomography (CT) was performed. CT confirmed the polymorphism of cardiac masses, both infiltrating and vegetating (fig. 6) and demonstrated cerebral, hepatic and adrenal glands metastases (fig. 7).

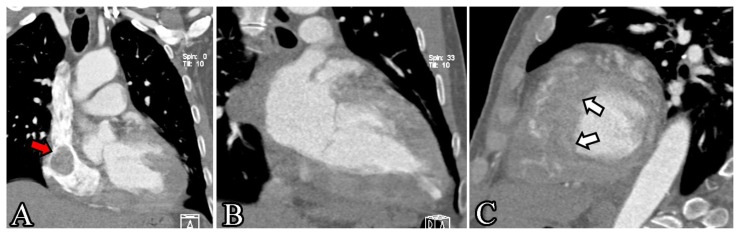

Figure 6.

61 year old male with cardiac metastases of melanoma.

Findings: MPR images of contrast enhanced CT of the chest in the arterial phase confirmed the polymorphism of cardiac masses, both infiltrating and vegetating. The areas with greater infiltration are the apex of the right ventricle, the mid-to-distal interventricular septum (white arrows), the posterior wall of the right ventricle and the lateral wall of the left ventricle. Clearly shown is also the atrial mass in the right atrium (red arrow), near superior vena cava.

Technique: chest CT (Somatom Definition 64-slice multidetector CT, Siemens, Germany), without ECG-gating, arterial phase after the intravenous injection of iodine contrast agent (100 ml at 5 ml/sec, Iomeron 400 mg iodine/ml, Bracco), slice thickness of 0.75 mm, 120 kVp, 160 mAs. Multiplanar reconstruction (MPR) images. A: inflow tract projection, B: 2-chamber view, C: short axis view.

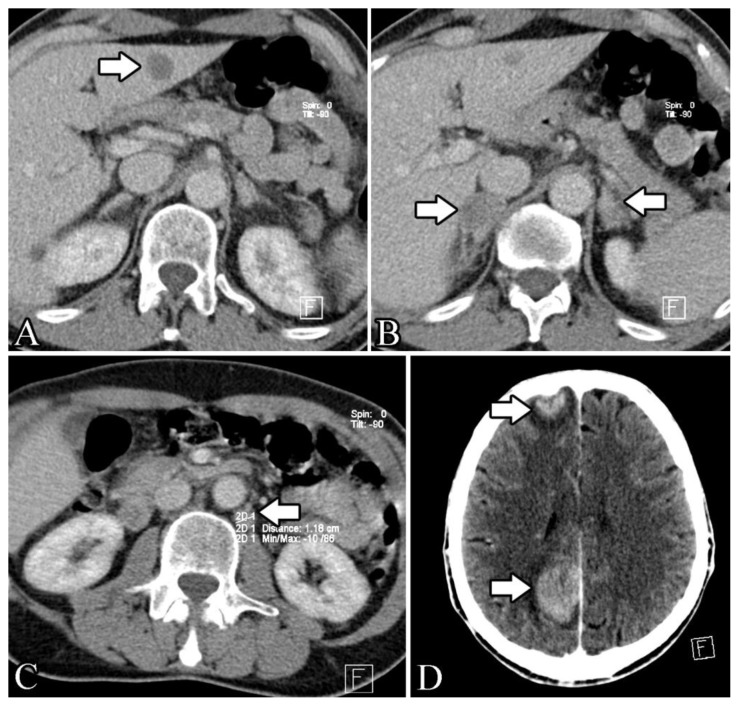

Figure 7.

61 year old male with cardiac metastases of melanoma.

Findings: axial contrast enhanced total body CT in the venous phase highlights a hypodense lesion of hepatic segment III, most likely a metastasis, with maximum diameters of around 15×19 mm (fig. 7a) (arrow). In B is evident the tumefaction of both adrenal glands (around 18×20 mm the left gland, 23×28 mm the right) (arrows) with radiological characteristic of metastasis. Image 7c shows para-aortic (arrow) and para-caval lymph nodes, most likely malign (around 11×13 and 13×15 mm). 2 cerebral focal lesions (arrows) with vivid contrast enhancement (around 25×32 mm the posterior one and 15×18 mm the anterior), highly suggestive for metastasis, are clearly recognizable in D.

Technique: total body CT (Somatom Definition 64-slice multidetector CT, Siemens, Germany) venous phase (70 seconds after the intravenous injection of iodine contrast agent, 300 seconds after the injection for the brain scan, 100 ml at 5 ml/sec, Iomeron 400 mg iodine/ml, Bracco), slice thickness of 5 mm on chest and abdomen, 4 mm on the brain scan, 120 kVp, 98 mAs. A: axial plane of the abdomen. B: axial plane of the abdomen. C: axial plane of the abdomen. D: axial plane of the brain.

Management and follow-up

Biopsy of the hepatic lesion confirmed it was a metastatic lesion and the histologic examination of the sacral skin lesion diagnosed a rare melanoma variant, malignant blue nevus. The patient started chemotherapy treatment, but unfortunately died around 1 year after the diagnosis.

DISCUSSION

Aetiology and demographics

Melanoma is a common neoplasm with a propensity to metastasize to the heart. Metastases of the cardiac structures are rare, but 20 to 40 times more common than primary cardiac tumours.

Clinical and imaging findings

Cardiac metastases are typically multifocal and may involve any portion of the heart (epicardium, myocardium and/or pericardium). Tumour cells may reach and involve heart and pericardium by four different pathways:

Haematogenous spread (most of the cases of melanoma) [1].

Retrograde lymphatic extension (in particular lymphoma).

Direct extension (breast and lung cancer).

Melanoma cells usually spread by the haematogenous pathway and infiltrate myocardium and epicardium through the coronary arteries or, less frequently, through the vena cava leading to a multifocal distribution, as in our case report. Valves and endocardium involvement is uncommon, while the right atrium is the most common site [4]. Cardiac metastases are often associated with haematogenous metastases to other organs, as in our case.

Metastatic melanoma involves heart or pericardium in greater than 50% of the cases, although cardiac metastasis are rarely diagnosed ante mortem [5]. Metastatic cardiac melanoma is often clinically silent and signs and symptoms are typically non-specific: dyspnoea, pedal oedema, cough, tachycardia, dysrhythmia and chest pain [6]. Because of the lack of symptoms in most of the cases cardiac metastasis are diagnosed post mortem, but a multimodality approach may help to obtain a more timely diagnosis. In rare cases cardiac metastasis can be the first manifestation of a tumour of unknown primary origin [2].

The first approach is often echocardiography, but the evaluation of the right ventricle and right atrial appendage can be limited. CT and CMR may highlight some important imaging findings.

CT is generally used for total body staging, but some findings can lead to the diagnosis of metastatic melanoma (for example, a haemorrhagic pericardial effusion). Nowadays, ECG-gated cardiac computed tomography angiography (CCTA) could be a valid diagnostic method due a spatial resolution higher than CMR; moreover, the high-resolution three-dimensional images can be produced with a low dose of ionizing radiation.

CMR has some important advantages: the lack of ionizing radiation, which is a substantial difference with CT, and a better contrast resolution that allows a more accurate tissue characterization of the aetiology of cardiac and pericardial masses. Indeed, T1w and T2w sequences and LGE sequences enables a better anatomic definition and tissue characterization, whilst cine gradient echo sequences asses the functional impact. Melanin is a natural paramagnetic substance and causes T1 shortening, so we expect melanoma to be T1 hyperintense and T2 hypointense, but only a small percentage of melanoma metastasis have the classic findings: for example, amelanotic melanoma may be T1 iso- or hypo-intense. Usually the melanoma metastases show a diffuse and avid gadolinium enhancement.

Fluorine-18-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) can be helpful for body staging of melanoma because the metastasis are usually FDG avid and SUV (standardized uptake value) can be an important tool to differentiate the normal cardiac uptake and any abnormalities.

Positron emission tomography-computed tomography (PET/CT) is a combined method that could be useful for the diagnosis, staging and follow up of patient with metastatic melanoma, thanks to its high sensitivity and specificity: in particular, this imaging method could be able to highlight a biologic alteration before any anatomic alteration could be seen, which is relevant for the treatment of these patients.

Treatment and prognosis

Cardiac metastases from malignant melanoma usually occurs in the setting of disseminated disease and are often identified during post mortem examination because they usually occur without clinical manifestations [7], so it is quite uncommon to have ante mortem diagnosis, as in our case, and it is frequently related to symptomatic cardiac involvement, even when primary melanoma is not yet identified and there is no prior history of melanoma. Even if most of the patients are at an advanced disease stage at the time of the diagnosis of the cardiac metastasis, in some cases a quicker and better diagnosis can enable a surgical resection to prevent cardiac failure or to reduce the tumour before chemotherapy.

Differential diagnoses

Cardiac metastases are generally hypointense on T1w images and hyperintense on T2w images, while melanoma metastases are generally hyperintense on T1w images due to their high melanin content, but only a small percentage of cases have the classic findings. In our case, most of the lesions were hyperintense on T1w images, although some of them have a very heterogeneous signal in T1w and T2w images.

In our case, the multifocal localization correlates more likely with metastases than primary tumour and the myocardial infiltration suggests haematogenous diffusion.

Finally, in the sequence after the intravenous administration of gadolinium contrast agent, the contrast agent uptake depends on the vascularization of the primary tumour: melanoma is a hyper-vascularized tumour, so we expect to see considerable contrast enhancement in the metastases and this is what we found in our case.

TEACHING POINT

Advanced diagnostic techniques, such as cardiac magnetic resonance, are important for the detection of cardiac masses, but also for a better anatomic definition and tissue characterization, to enable a quick and accurate diagnosis which can be follow by appropriate treatment. Multifocal localization correlates more likely with metastases than primary tumour and the myocardial infiltration suggests haematogenous diffusion; melanoma metastases are generally hyperintense on T1w images, but frequently they have a very heterogeneous signal in T1w and T2w images and a considerable contrast enhancement.

Table 1.

Summary table of general characteristics of melanoma and cardiac metastasis of melanoma.

| Etiology | Environmental and genetic factors for melanoma |

| Incidence |

|

| Gender ratio | No sexual predilection |

| Age predilection | Melanoma incidence rates increase with age |

| Risk factors | Melanoma risk factors:

|

| Signs or symptoms |

|

| ECG findings | Non specific |

| Treatment |

|

| Prognosis | It exhibits an unpredictable clinical behavior so the natural history is difficult to predict |

| Localization |

|

| Findings on MRI imaging |

|

MRI: magnetic resonance imaging, T1w: T1 weighted, T2w: T2 weighted, LGE: late gadolinium enhancement.

Table 2.

Differential Diagnosis table for cardiac metastases of melanoma [3].

| Characteristics | Uni-/multifocal | CT | MRI | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T1w | T2w | CE | ||||

| Cardiac melanoma metastasis | Multifocal cardiac masses +/− pericardial effusion | Multifocal | Body staging | Hyper | Hypo | Diffuse and avid |

| Thrombus | Intracavitary | Uni- or multifocal | Filling defect after CA injection | Hyper (if new), Hypo (if organized) | Hyper (if new), Hypo (if organized) | No |

| Pericarditis | Possible nodularity and thickening of the pericardium | Uni- or multifocal | Enhancement of thickened pericardium | Hypo | Hyper | Yes |

| Fibroma | Homogeneous soft-tissue mass, marginated or infiltrative | Unifocal | Calcifications are common | Iso | Hypo | Usually no |

| Primary malign tumor | Thickening and deformation of the myocardium | Uni- or multifocal | Often low-attenuated mass, irregular or nodular | Variable | Variable | Yes |

| Bronchogenic carcinoma (cardiac involvement) | Frequently by direct extension | Unifocal | Must be suspected when CT or MRI demonstrates obliteration of the superior pulmonary vein | |||

| Breast cancer metastasis | Myocardial and/or pericardial mass | Multifocal | Low attenuation mass | Hypo | Hyper | Yes |

| Lymphoma | No regional predilection | Focal | Irregular thickening of the walls, hypo/iso-attenuated | Iso | Hyper | Yes |

| Osteosarcoma (cardiac involvement) | Metastases contain bone | Focal | Calcific areas of increased opacity | Hypo/iso | Iso/hyper | Yes |

CT: computed tomography, MRI: magnetic resonance imaging, T1w: T1 weighted, T2w: T2 weighted, CE: contrast enhancement, hyper: hyperintense signal, hypo: hypointense signal, iso: isointense signal, CA: contrast agent

ABBREVIATIONS

- CCTA

cardiac computed tomography angiography

- CMR

cardiac magnetic resonance

- CT

computed tomography

- ECG

electrocardiogram

- FDG-PET

fluorine-18-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography

- LGE

late gadolinium enhancement

- LV

left ventricle

- PET/CT

positron emission tomography-computed tomography

- RA

right atrium

- SSFP

steady state free procession

- SVC

superior vena cava

- T1w

T1 weighted

- T2w

T2 weighted

REFERENCES

- 1.Young JM, Goldman IR. Tumor metastasis to the heart. Circulation. 1954;9(2):220–9. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.9.2.220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Savoia P, Fierro MT, Zaccagna A, Berengo MG. Metastatic melanoma of the heart. J surg Oncol. 2000;75(3):203–7. doi: 10.1002/1096-9098(200011)75:3<203::aid-jso9>3.0.co;2-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chiles C, Woodard PK, Gutierrez FR, Link KM. Metastatic involvement of the heart and pericardium: CT and MR imaging. Radiographics. 2001;21(2):439–449. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.21.2.g01mr15439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wood A, Markovic SN, Best PJ, Erickson LA. Metastatic malignant melanoma manifesting as an intracardiac mass. Cardiovasc Pathol. 2010;19(3):153–7. doi: 10.1016/j.carpath.2008.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grebenc ML, de Christenson R, Burke AP, Green CE, Galvin JR. Primary cardiac and pericardial neoplasms. Radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiographics. 2000;20(4):1073–103. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.20.4.g00jl081073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gulati G, Sharma S, Kothari SS, Juneja R, Saxena A, Talwar KK. Comparison of echo and MRI in the imaging evaluation of intracardiac masses. Cardiovasc intervent radiol. 2004;27(50):459–469. doi: 10.1007/s00270-004-0123-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Auer J, Schmid J, Berent R, Niedermair M. Cardiac metastasis of malignant melanoma mimicking acute coronary syndrome. Eur Heart J. 2012 Mar;33(5):676. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehr289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sparrow P, Kurian J, Jones TR, Sivananthan MU. MR Imaging of cardiac tumors. Radiographics. 2005;25(5):1255–1276. doi: 10.1148/rg.255045721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tesolin M, Lapierre C, Oligny L, Bigras JL, Champagne M. Cardiac metastases from melanoma. RadioGraphics. 2005;25(1):249–253. doi: 10.1148/rg.251045059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Luna A, Ribes R, Caro P, Vida J, Erasmus JJ. Evaluation of cardiac tumors with magnetic resonance imaging. Eur Radiol. 2005;15(7):1446–1455. doi: 10.1007/s00330-004-2603-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Allen BC, Mohammed TL, Tan CD, Miller DV, Williamson EE, Kirsch JS. Metastatic Melanoma to the Heart. Curr Probl Diagn Radiol. 2012;41(5):159–164. doi: 10.1067/j.cpradiol.2011.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Glancy DL, Roberts WC. The heart in malignant melanoma. A study of 70 autopsy cases. Am J Cardiol. 1968 Apr;21(4):555–71. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(68)90289-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grebenc ML, Rosado de Christenson ML, Burke A, Green CE, Galvin JR. Primary cardiac and pericardial neoplasms. Radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiographics. 2000;20(4):1073–103. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.20.4.g00jl081073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chiles C, Woodard PK, Gutierrez FR, Link KM. Metastatic Involvement of the Heart and Pericardium: CT and MR Imaging. Radiographics. 2001;21(2):439–449. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.21.2.g01mr15439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fishman LK, Kublman JE, Schuchter LM, Miller JA, III, Magici D. MD, CT of Malignant Melanoma in the Chest, Abdomen, and Musculoskeletal System. RadloGraphics. 1990;10(4):603–620. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.10.4.2198632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sparrow PJ, Kurian JB, Jones TR, Sivananthan MU. MR Imaging of Cardiac Tumors. RadioGraphics. 2005;25(5):1255–1276. doi: 10.1148/rg.255045721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]