Abstract

Objective To investigate the effectiveness of a school based intervention to increase physical activity, reduce sedentary behaviour, and increase fruit and vegetable consumption in children.

Design Cluster randomised controlled trial.

Setting 60 primary schools in the south west of England.

Participants Primary school children who were in school year 4 (age 8-9 years) at recruitment and baseline assessment, in year 5 during the intervention, and at the end of year 5 (age 9-10) at follow-up assessment.

Intervention The Active for Life Year 5 (AFLY5) intervention consisted of teacher training, provision of lesson and child-parent interactive homework plans, all materials required for lessons and homework, and written materials for school newsletters and parents. The intervention was delivered when children were in school year 5 (age 9-10 years). Schools allocated to control received standard teaching.

Main outcome measures The pre-specified primary outcomes were accelerometer assessed minutes of moderate to vigorous physical activity per day, accelerometer assessed minutes of sedentary behaviour per day, and reported daily consumption of servings of fruit and vegetables.

Results 60 schools with more than 2221 children were recruited; valid data were available for fruit and vegetable consumption for 2121 children, for accelerometer assessed physical activity and sedentary behaviour for 1252 children, and for secondary outcomes for between 1825 and 2212 children for the main analyses. None of the three primary outcomes differed between children in schools allocated to the AFLY5 intervention and those allocated to the control group. The difference in means comparing the intervention group with the control group was –1.35 (95% confidence interval –5.29 to 2.59) minutes per day for moderate to vigorous physical activity, –0.11 (–9.71 to 9.49) minutes per day for sedentary behaviour, and 0.08 (–0.12 to 0.28) servings per day for fruit and vegetable consumption. The intervention was effective for three out of nine of the secondary outcomes after multiple testing was taken into account: self reported time spent in screen viewing at the weekend (–21 (–37 to –4) minutes per day), self reported servings of snacks per day (–0.22 (–0.38 to –0.05)), and servings of high energy drinks per day (–0.26 (–0.43 to –0.10)) were all reduced. Results from a series of sensitivity analyses testing different assumptions about missing data and from per protocol analyses produced similar results.

Conclusion The findings suggest that the AFLY5 school based intervention is not effective at increasing levels of physical activity, decreasing sedentary behaviour, and increasing fruit and vegetable consumption in primary school children. Change in these activities may require more intensive behavioural interventions with children or upstream interventions at the family and societal level, as well as at the school environment level. These findings have relevance for researchers, policy makers, public health practitioners, and doctors who are involved in health promotion, policy making, and commissioning services.

Trial registration Current Controlled Trials ISRCTN50133740.

Introduction

Low levels of physical activity and of fruit and vegetable consumption in childhood track into adulthood.1 2 3 They are associated with adverse health outcomes, including greater adiposity and associated adverse cardiometabolic risk factors, poorer bone mineralisation, behavioural problems, low mood, and poorer academic attainment.4 5 6 7 8 9 10

School based interventions have the potential to reach the vast majority of children, and systematic reviews of school based interventions aimed at increasing physical activity, decreasing sedentary behaviour, and improving fruit and vegetable consumption suggest some beneficial effect.11 12 13 14 15 16 However, they also highlight the generally poor quality of included studies and caution that the pooled results might exaggerate the effectiveness of the interventions.11 12 13 14 15 16

A systematic review that included 44 school based randomised controlled trials found beneficial effects on moderate or vigorous physical activity during school hours, but the authors noted that the benefit might have been exaggerated owing to the outcome assessment being self reported or parent reported and not blind to school allocation in most trials, and also that the marked loss to follow-up in several trials might have biased findings.11 Furthermore, given that the interventions largely included extra compulsory physical activity lessons, the finding of greater time spent in moderate or vigorous physical activity during school hours is not surprising. Evidence from observational epidemiological studies suggests that compulsory physical activity lessons in school are associated with more school based activity but not with more total activity17 18; in the long term, people who attended schools with more compulsory physical activity have similar levels to other people of physical activity, physical fitness, and body mass index as young adults.18 A second systematic review included only studies in which physical activity had been assessed objectively by accelerometers and did not restrict the outcome to activity during school hours; it included school based studies, as well as those of interventions in other settings.12 It reported beneficial effects of interventions, with no evidence that this differed between school based interventions and those in family or other setting. The authors commented that the magnitude of the effect was small and unlikely to be of health benefit,12 although modest shifts in risk factors can produce important public health benefit.

One systematic review identified five randomised controlled trials of school based intervention to reduce sedentary behaviour and reported that all of them were effective.15 Results were not pooled formally, and the outcome in all of the studies was based on self or parental report.15 In a more recent systematic review and meta-analysis, evidence from 34 randomised controlled trials suggested that both school based interventions and those in other settings were effective in reducing time spent in sedentary behaviour and consequently in reducing mean body mass index.16 Only nine of these studies reported that random allocation was adequately concealed, and only eight reported blinding of the outcome assessment; sedentary behaviour was assessed by self or parental report in all studies.16

One recent systematic review of school based interventions to increase fruit and vegetable consumption identified 19 randomised controlled trials,13 and another identified 27 randomised or non-randomised trials.14 The first review, which focused solely on primary school interventions, concluded that computer based interventions were effective on the basis of pooling of two trials, but pooling of other trials did not suggest that interventions were effective.13 The authors noted that most of the studies did not describe the randomisation method and that ascertaining whether allocation was concealed was not possible for most of the 19 trials reviewed. They also noted that most trials did not take account of clustering (non-independence between children from the same school) in their analyses, despite all being cluster randomised trials.13 The second review also focused on children in the primary school age range (5-12 years), but the authors concluded on the basis of pooled results from 21 (out of 27) controlled trials that school based interventions were effective at increasing fruit but not vegetable consumption.14 Again, the authors noted the poor quality of most of the trials.

In this paper, we report the results of the Active for Life Year 5 (AFLY5) school based cluster randomised controlled trial. The intervention aimed to increase time spent in moderate or vigorous physical activity, reduce sedentary behaviour, and increase fruit and vegetable consumption, within a study design that overcame many of the limitations of previous trials in this area.19 Specifically, random allocation was concealed, time spent in moderate or vigorous physical activity and sedentary behaviour was objectively assessed using accelerometers, and the fieldworkers collecting outcome data from children were blind to school allocation.19 This is also one of the largest randomised controlled trials in this area to date, and the cluster nature of the design was taken into account in the sample size calculation and analysis.19 20 The intervention was designed to change children’s behaviours in a non-compulsory way, so measurements were concerned with the whole day, not just during school hours, and we achieved high levels of follow-up in both arms of the study.

Methods

Study design

AFLY5 is a school based, cluster randomised controlled trial. The trial protocol was published in 2011, before any recruitment or data collection, and a more detailed statistical analysis plan was subsequently published before any analysts had access to data. Results presented in this paper have been obtained by following the published study protocol and analysis plan.19 20 The trial was registered before recruitment of schools or data collection (www.controlled-trials.com/ISRCTN50133740).

Eligibility and recruitment

State primary or junior schools with year 4-6 pupils in the Bristol City and North Somerset administrative areas were eligible for inclusion. Between March and July 2011 all state primary and junior schools with children in years 4-6 (age 8-11 years) in the areas covered by Bristol City Council (93 schools) and North Somerset Council (55 schools) were invited to participate. Both of these areas are in the south west of England and include a range of levels of deprivation, as well as urban and rural areas. We excluded special schools (for children whose additional needs cannot be met in a mainstream setting) because they were unlikely to be teaching the standard UK National Curriculum and the children may not have been able to take part in all the measurements. We invited 148 schools to participate, and 63 expressed an interest in taking part; three schools subsequently withdrew their interest. We recruited 60 schools (46 in Bristol and 14 in North Somerset). Participants were children in year 4 (age 8-9 years) at the time of recruitment.

Once schools had agreed to participate in the study, we sent parents/guardians of children in year 4 a letter and information sheet about the study with an opt-out consent form for their child for each of the measurements. They were given the opportunity to contact the research team to discuss the study and also information about being able to withdraw at any stage. An information sheet for the child was sent with the letter to the parents. The children were given a second copy of this information sheet at the time that measurements were taken, and they were asked to give signed assent to each of the measurements.

Randomisation

Before randomisation, we asked school heads to complete a brief questionnaire about the school. This included three questions that asked them to list all activities the school was engaged in that related to increasing physical activity, decreasing sedentary behaviour, and promoting a healthy diet in pupils. Responses were free text, and on the basis of these responses we classified each school as having either high (one or more initiative) or low (no initiatives) involvement in health promoting initiatives relevant to the outcomes of this trial. Where heads (or teachers that they delegated the task to) reported initiatives that were part of the UK National Curriculum or that they had been awarded “healthy schools” or “healthy schools plus” status, we did not include these as involvement in an initiative, as these are widespread in the south west of England and we were looking for additional initiatives that varied between schools. We also defined schools as being in an area of high, medium, or low deprivation by splitting them into thirds based on their score on the English Index of Multiple Deprivation 2010.21 We grouped schools into six mutually exclusive strata by these two characteristics and randomly allocated them to control or intervention within these strata.19 20 One author (DAL) who was unaware of any characteristics of the schools did the randomisation (identification numbers were used to relate schools to the two stratifying variables, and DAL had no knowledge of which schools these numbers linked to). Randomisation was concealed by using the Bristol Randomised Trials Collaboration’s automated (remote) system. After randomisation, one school refused to undertake the intervention; the head reported that they had hoped they would be randomised to control and did not have the time or capacity to accommodate the intervention. The school did agree to participate in all pupil measurement sweeps. This school is included in its randomised group (intervention) for the main intention to treat analysis and is excluded from the per protocol analysis.

Intervention

The AFLY5 intervention is a school based intervention that aims to increase children’s self efficacy and knowledge, together with motivating parents, to increase children’s levels of physical activity, reduce sedentary behaviour, and increase consumption of fruit and vegetables; a secondary aim is to improve other aspects of healthy activity and diet.19

Rationale

We began work in 2006 to design, pilot, and then fully evaluate a school based intervention to improve levels of activity and diet and other health outcomes in children. Consistent with recommendations of the UK Medical Research Council, and others, for the evaluation of complex interventions, our aim was to develop an intervention that was theory based and built on evidence from appropriate reviews of the literature and then to test its feasibility and complete pilot work before seeking funds for a full scale randomised controlled trial.22 23 Among national and international policy makers and researchers, a strong belief has been held for some decades that simple interventions in schools can change unhealthy behaviours to healthy ones.24 25 We wanted to test this and so sought an intervention that could be delivered in schools with minimal disruption to the main aim of educating children and that would be relatively inexpensive. Lastly, we wanted an intervention that focused on children under the age of 11, because of evidence that persistent overweight/obesity and the association of greater adiposity with future coronary heart disease is established by this age.26 27

Our original literature search identified a cluster randomised controlled trial in 11-12 year olds and a quasi-randomised trial of 8-9 year olds,28 29 both completed by the same group of researchers and of a similar intervention that matched the type of intervention we wanted to develop for use in the United Kingdom. The intervention, based on social cognitive theory and with a particular emphasis on improving children’s self efficacy to make behavioural change,30 31 aimed to reduce childhood obesity and improve health through changes in physical activity, diet, and screen viewing. These studies found beneficial effects, including on overweight/obesity in girls in the older age group; in the study of the younger age group, body mass index was not assessed.

Between 2006 and 2008 we worked with primary school teachers, the local primary care trust (public health commissioners), and the local council (government) in South Gloucestershire, in the south west of England, to determine whether this intervention could be adapted for use in the UK, whether delivering the adapted intervention within the National Curriculum was feasible, and whether a pilot randomised controlled trial provided evidence of promise for the intervention sufficient to justify a full scale trial. This work showed that with minor adaptations the intervention could be delivered within the UK National Curriculum for year 5 (age 9-10) children, and the pilot study suggested that it might be effective.32 We had a limited budget for the pilot and were not able to test the use of accelerometers in it. The process evaluation in the pilot study found that the teachers thought the intervention should be extended to include parents if it was to be maximally effective.32 33 We therefore obtained a further small budget and undertook qualitative work with parents and teachers to develop the intervention in such a way that it involved parents; this showed that child-parent interactive homework would be feasible and acceptable to them.33 We then completed a feasibility study (examining changes in the same children before and after the intervention) of adding child-parent interactive homework to AFLY5 and of collecting accelerometer data.33 34 Results from that work provided further support for going ahead with a full scale randomised controlled trial of the AFLY5 intervention that now includes interactive homework activities as well as lessons. None of the schools or teachers who were involved in the feasibility and pilot work was included in the main trial, which is presented in this paper.

What the intervention involves, including who delivers different aspects of it, where, and how

Full details of the intervention have been published in the trial protocol and pilot study and are available on the study website (www.bristol.ac.uk/social-community-medicine/projects/afl/).19 23 The intervention has five components, as described below.

Training for year 5 classroom teachers and learning support assistants—This was provided by the trial manager, a nutritionist, and a physical education specialist. The training took place over a whole day (8-9 hours) in a location away from any of the schools and where the teachers/learning support assistants and people delivering the training would not be interrupted. Teachers/learning support assistants were given a choice of days to attend the training, and schools were financially compensated for the cost of replacement teachers while their staff attended training. At the training days, the rationale for the intervention was explained, and each lesson and homework activity was discussed and then taught in interactive ways. Time was provided for questions and discussion. Teachers were instructed to deliver 16 lessons, 10 of which had associated homework to be handed out by the teachers. They were told that they could adapt the teaching plans and materials, as they would with other lessons (for example, to suit their own style and the range of abilities in their class), but the aims and knowledge/skills to be imparted should remain the same.

Provision of 16 lesson plans and teaching materials—These included pictures, CDs, and journals for year 5 teachers or learning support assistants to deliver over two out of the three school terms in year 5 (6-7 months). The 16 lessons included nine lessons that were primarily related to how to be more active and less sedentary and why this was important, six related to healthy nutrition and how to achieve this, and one about reducing screen viewing. Each lesson did, however, combine different aspects of healthy behaviour. For example, in the physical activity lessons the children played games based on the food groups (using photographs of food), which reinforced the content of the nutrition lessons. Similarly, in the lesson (and associated homework) for reducing screen viewing (called “Freeze my TV”), children were taught how to replace regular television watching with active play on some days.

Provision of 10 parent-child interactive homework activities—The homework activities were designed to involve parents and other family members in the behavioural change process by reinforcing the messages delivered during lessons. The homework included activities such as “Freeze my TV,” in which a time/programme normally spent watching television would be replaced with physically active play involving the parents and other family members that the child would write a log about; cooking simple healthy food at home; playing “Top Grubs,” a card game based on trumps with pictures of food, such that higher scoring (trumping) foods are the healthier ones; and measuring the sugar content of drinks that the family have at home or include in school/work lunch packs.

Provision of written information—Schools could insert information (as they wished) in the school newsletters about the importance of increasing physical activity, reducing sedentary behaviour, and improving diet. The inserts were sent to all intervention schools on three occasions over the period of the intervention. Schools were free to edit these and insert none, all, or some of them.

Written information for parents—This described how to encourage their children to eat healthily and be active. It was delivered to parents via the children attending the schools at the start of the intervention

The intervention took place when the children were in school year 5 (age 9-10 years) after baseline assessment (see below). Our previous feasibility work showed that the AFLY5 intervention was aligned to the UK National Curriculum for Key Stage 2 (which is used for all children aged 7-11 years old).32 Schools randomised to the control group continued standard education provision for the school year, and any involvement in additional health promoting activities, but had no access to the intervention teacher training and no known access to the teaching materials, which have not been published and were not made available by the research team beyond the intervention schools.

Outcome measures

The box lists all the primary and secondary outcome measurements.

AFLY5 primary and secondary outcomes

Primary outcomes

Accelerometer assessed mean time per day spent doing moderate/vigorous physical activity

Accelerometer assessed mean time per day spent in sedentary activity

Self reported (validated questionnaire) servings of fruit and vegetables consumed per day

Secondary outcomes

Self reported (validated questionnaire) mean time spent screen viewing on a typical weekday

Self reported (validated questionnaire) mean time spent screen viewing on a typical weekend day

Self reported (validated questionnaire) servings of snacks consumed per day

Self reported (validated questionnaire) servings of high fat foods consumed per day

Self reported (validated questionnaire) servings of high energy drinks consumed per day

Body mass index determined from weight and height measured in classrooms by two study fieldworkers

Waist circumference measured in classrooms by two study fieldworkers

General overweight/obesity, determined by the International Obesity Task Force thresholds of body mass index for children (taking account of their age and sex)

Central overweight/obesity determined by thresholds of UK age and sex specific reference charts for waist circumference and defined by the International Diabetes Federation

Participant assessments

Baseline assessments (before the intervention) were carried out when the children were in the final term of year 4 or early in the first term of year 5. Outcome assessment was completed immediately after the intervention (end of year 5). Identical protocols and procedures were used at both assessments. They were undertaken by trained fieldworkers who had completed enhanced Criminal Records Bureau/Disclosure and Barring Service checks. The fieldworkers were blinded to the allocation of schools to the arms of the trial.

We used ActiGraph GT3X+ accelerometers to assess physical activity and sedentary time. Accelerometers were distributed at the school visit and collected from the schools six days later to allow five days of data collection (three on weekdays and two on weekend days). The children were asked to wear them during the day (except when bathing, swimming, or participating in contact sports such as karate). As detailed in the published analysis plan, we defined time spent in moderate or vigorous physical activity as any time spent in activities that were at least 2296 counts per minute and time spent in sedentary behaviour as time spent in activities between 0 and 100 counts per minute.20

All anthropometric measurements were completed with children in a private room with two Criminal Records Bureau checked, trained fieldworkers present. Weight was measured without shoes in light clothing to the nearest 0.1 kg by using a Seca digital scale. Height was measured, to the nearest 1 mm, without shoes by using a portable Harpenden stadiometer. Fieldworkers were trained to ensure correct position for height assessment. Waist circumference was measured to the nearest 1 mm at the mid-point between the lower ribs and the pelvic bone with a flexible tape and repeated three times.35 When body mass index and waist circumference were treated as continuous outcome variables, we derived internally standardised z scores (also known as standard deviation scores) by subtracting the mean body mass index/waist circumference for a given sex and age (in 6 months) category from the observed measure and dividing by the standard deviation for the sex and age category. For binary outcomes, we used International Obesity Task Force age (in 6 months) and sex specific thresholds for overweight to define whether a child was overweight/obese on the basis of body mass index.36 For waist circumference, we defined any child above the 90th centile for age and sex specific values derived from UK relevant centiles as having central overweight/obesity,37 as suggested by the International Diabetes Federation.38

We assessed servings of fruit and vegetable consumption and other dietary outcomes by using the “A Day in the Life Questionnaire.”39 40 The method we used for determining servings of different food types from the text responses to this questionnaire, including reliability and validity checks, has been previously published.20 39 We used an established and validated scoring scheme to assess servings of daily fruit and vegetable consumption and other dietary outcomes.39 41 42 We used an abbreviated and updated version of a previously validated screen viewing questionnaire to assess self reported sedentary behaviour43; details of how we derived variables from this questionnaire have been previously reported.20 32

We combined all questionnaires into one document for administration in the classroom. The children completed it in the presence of at least one of the trained fieldworkers and a teacher who answered any queries and assisted the children with reading and writing according to the study protocol. This instructed them to help with reading and spelling specific words and not to suggest answers to any questions.

Sample size calculation

The sample size calculation was based on the intra-cluster correlation coefficients for different outcomes and other information collected during pilot/feasibility work.19 20 32 For each of the three primary outcomes, we determined the number of schools required (assuming 25 pupils per school) to detect at least a 0.25-0.30 standard deviation difference between pupils in intervention and control schools with 80-90% power and a two sided α of 0.05 and allowing for 15% loss to follow-up or missing data.19 For secondary outcomes, we took account of multiple testing and aimed to have at least 80% power at an α of 0.01 for all of these, including to detect a relative minimum difference of 30% in general or central overweight/obesity.19 These calculations showed that we needed to recruit 60 schools with a total of at least 1500 children, with 1275 (after allowing for loss to follow-up/missing data) available for the primary analyses.

Statistical analyses

Full details of the analysis plan have been published.20 We used intention to treat analyses as our main analyses, with missing data at baseline dealt with by including an indicator variable for those with missing data, as suggested by White and others.44 45 46 We also did a series of sensitivity analyses to test the assumptions that we had made regarding the nature of missing baseline and outcome data (see supplementary table A and detailed analysis plan for detailed discussion of these assumptions and the sensitivity analyses20).44 45 We used multilevel regression models to account for the clustering (non-independence) of children within schools.20 All analyses included adjustment for the following baseline variables: age, sex, the baseline measure of the outcome being analysed, and the two pre-randomisation stratifying variables (involvement in other healthy behaviour promoting activities and school level deprivation).

We also did a secondary, per protocol, analysis, in which classes in the intervention arm were included in the analysis only if teachers had taught at least 70% (11/16) of the AFLY5 lessons.20 As our unit of randomisation was schools and all pupils in any class will have been taught the same number of lessons, this means that whole classes (rather than selected children within intervention classes of schools) for which the teacher did not teach at least 70% of lessons were excluded from the per protocol analyses. Some of the intervention schools had more than one year 5 class (the maximum was three classes per school). In the main per protocol analyses presented here, exclusions were made on the basis of classes (that is, if one out of three classes in the same school did not reach the threshold of 70% of lessons taught, only children from that class, and not the whole school, were excluded); repeating the analyses on the basis of whole schools did not materially alter the results (available from authors on request). We assessed the number of lessons taught by reviewing the teacher completed log where possible or by confirming these details with the teacher in person or by telephone. We had information on lessons taught for 29 of the 30 schools allocated to the intervention, including the school noted earlier that refused to do any part of the intervention. For the one school for which we were completely ignorant of how many lessons had been taught, we firstly did analyses assuming that they had taught at least 11 lessons and then repeated them assuming that they had taught fewer than 11. The results were identical for these two alternatives.

We did additional analyses to assess whether the effect of the intervention on accelerometer assessed outcomes differed by week or weekend day and whether the results were affected by implausible values.20

Results

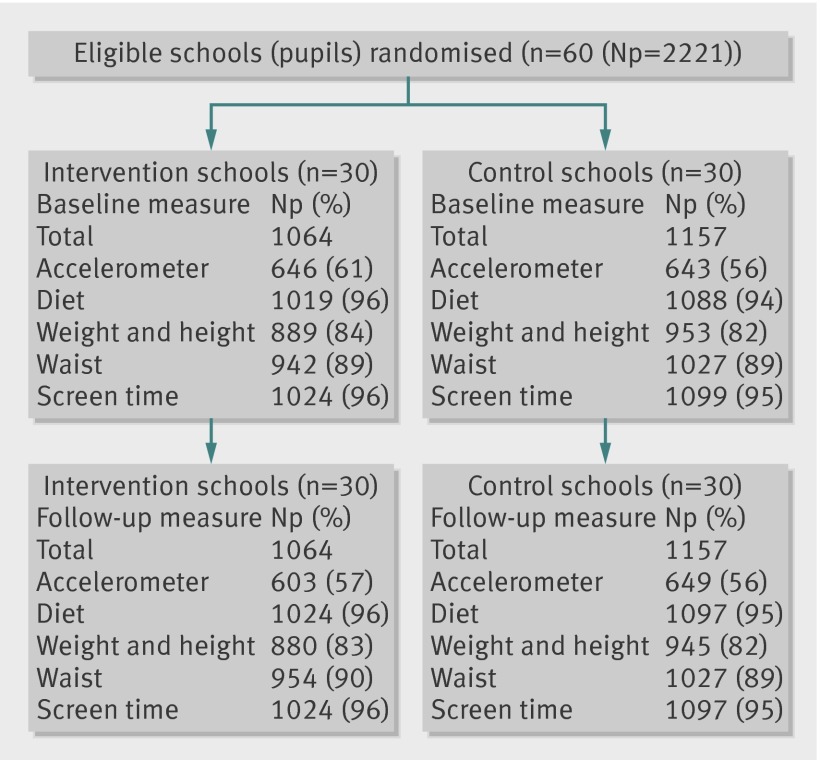

The figure shows the trial profile. The number of pupils in each class/school year was larger than we had anticipated, so for the 60 schools recruited the number of pupils included was greater than the required 1500. Of the 2242 potentially eligible students in the 60 participating schools, 10 left the school before randomisation and baseline data collection and for 11 their parents or carers did not provide consent to participate in any aspect of the study. All other children (n=2221; 1064 in the schools that were randomised to intervention and 1157 in the control schools), irrespective of whether they had all measurements or not, are included in the trial and used as denominators for baseline comparisons between the two randomised groups.

Trial profile. Np=number of participants (school pupils). No schools withdrew from study, so all randomised units are present at baseline and follow-up. Percentages for proportions of children with each measurement at baseline and follow-up are of total number of children who were pupils in randomised schools at baseline. Not all pupils with follow-up measure necessarily had data on same measure at baseline (or vice versa), because of different pupils being absent at both main and catch-up assessments at each time point and because of pupils leaving or moving between schools. In all analyses, those who were randomised were analysed in group (intervention or control) to which they were randomised

These numbers include a small number of participants (n=65) for whom the parent/care giver refused consent for one or more measurement (most commonly weight and occasionally waist circumference). Up to two “catch-up” visits were made to schools to obtain data on any pupils who were absent on the day of data collection for their school, but inevitably some pupils will have been absent on both the main and catch-up visits for their school at either baseline or follow-up. No child refused assent for completing the questionnaires, but for a small number we could not code their dietary data because of being unable to read what was written or identify what the food was where a brand name was used. Small numbers of pupils did not assent to waist or weight measurements, and the proportion of pupils with valid accelerometer data was influenced by the requirement that they had three days of at least eight hours of valid wear time.20 In total, at both baseline and follow-up between 82% and 96% of participants had data on diet outcomes, body mass index, and waist circumference, and approximately 60% had valid accelerometer data (figure). With the exception of valid accelerometer data, the number of children included in the main analyses (1825 to 2121) was greater than the 1275 that our sample size calculations showed were required for the main analyses. For accelerometer based measurements, data were available for 1252 children for the main analyses, 23 (0.02%) fewer than the estimated requirement.20 Proportions with valid data for each measure were similar at both baseline and follow-up and in intervention and control schools (figure).

Baseline characteristics, including for accelerometer return and wear time, were similar in intervention and control schools, with the exception of reported screen viewing time on Saturdays, which was 15 minutes per day greater in participants from the control schools compared with the intervention schools (table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of participants by randomised group. Values are numbers (percentages) unless stated otherwise

| Characteristic | Intervention schools (n=1064 participants) | Control schools (n=1157 participants) |

|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) age, years | 9.5 (0.3) (n=1024) | 9.5 (0.3) (n=1099) |

| Mean (SD) MVPA, minutes | 59 (23) (n=912) | 56 (21) (n=928) |

| Mean (SD) sedentary behaviour, minutes | 422 (72) (n=912) | 416 (68) (n=928) |

| Median (IQR) No of servings per day: | (n=1019) | (n=1088) |

| Fruit and vegetables | 1 (0-2) | 1 (0-2) |

| Snacks | 2 (1-3) | 2 (1-3) |

| High fat foods | 0 (0-1) | 1 (0-1) |

| High energy drinks | 2 (1-3) | 2 (1-3) |

| Mean (SD) body mass index, z score | –0.06 (0.94) (n=889) | 0.05 (1.04) (n=953) |

| Mean (SD) waist circumference, z score | –0.03 (0.97) (n=942) | 0.03 (1.02) (n=1027) |

| Median (IQR) minutes of screen viewing: | (n=1024) | (n=1099) |

| Weekday | 105 (45 to 240) | 105 (45 to 225) |

| Saturday | 90 (30 to 240) | 105 (30 to 240) |

| Wearing accelerometer: | (n=646) | (n=643) |

| Median (IQR) total No of valid days | 4 (3-5) | 4 (3-5) |

| Median (IQR) total No of valid weekdays | 3 (3-3) | 3 (3-3) |

| Mean (SD) total hours valid days, hours/day | 11.9 (1.2) | 11.7 (1.2) |

| Mean (SD) hours on valid weekdays, hours/day | 12.2 (1.3) | 12.0 (1.3) |

| Categorical variables | ||

| Male sex | 544 (51) | 549 (48) |

| General overweight/obesity | 172/889 (19) | 210/953 (22) |

| Central overweight/obesity | 341/942 (36) | 396/1027 (39) |

| Returned accelerometer | 979 (92) | 1025 (89) |

| Wore accelerometer for requested amount of time | 244 (23) | 204 (18) |

| Wore accelerometer for required amount of time | 646 (61) | 643 (56) |

| School involved in other health promoting activities | 800 (75) | 711 (61) |

| School deprivation score: | ||

| Low | 315 (30) | 460 (40) |

| Medium | 368 (35) | 345 (30) |

| High | 381 (36) | 352 (30) |

IQR=interquartile range; MVPA=moderate or vigorous physical activity.

In the main intention to treat analysis with adjustment for baseline variables, none of the three primary outcomes differed between children in schools allocated to the AFLY5 intervention and those allocated to control schools (table 2). The intervention was effective for three out of nine of the secondary outcomes after we had taken account of multiple testing in these analyses: self reported time spent on screen viewing at the weekend (Saturday) and self reported consumption of snacks and of high energy drinks were all lower in pupils from intervention schools compared with control schools (table 2). We found no strong evidence that the intervention affected the other secondary outcomes in these analyses, especially after taking into account multiple testing.

Table 2.

Main intention to treat analyses of effect of AFLY5 intervention on primary and secondary outcomes assessed immediately after end of intervention

| Outcomes (primary/secondary) | Control (reference) group | Intervention group | Main comparison between two groups (intervention v control) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Np | Mean (SD) or No (%) | Np | Mean (SD) or No (%) | Np | Difference in means or odds ratio (95% CI)* | P value | |||

| Continuous outcomes (primary)† | |||||||||

| Time spent in MVPA‡ (min/day) | 649 | 56.65 (23.42) | 603 | 55.25 (22.33) | 1252 | –1.35 (–5.29 to 2.59) | 0.50 | ||

| Time spent in sedentary behaviour (min/day) | 649 | 451.84 (65.40) | 603 | 454.08 (66.78) | 1252 | –0.11 (–9.71 to 9.49) | 0.98 | ||

| Servings of fruit and vegetables (No/day) | 1097 | 1.81 (1.55) | 1024 | 1.89 (1.70) | 2121 | 0.08 (–0.12 to 0.28) | 0.42 | ||

| Continuous outcomes (secondary)§ | |||||||||

| Time spent screen viewing (min/day weekday) | 1097 | 145.45 (133.95) | 1024 | 132.52 (125.37) | 2121 | –15.56 (–33.56 to 2.45) | 0.09 | ||

| Time spent screen viewing (min/day Saturday) | 1097 | 175.64 (171.79) | 1024 | 155.33 (154.43) | 2121 | –20.86 (–37.30 to –4.42) | 0.01 | ||

| Body mass index (z score¶) | 945 | 0.05 (1.03) | 880 | –0.05 (0.95) | 1825 | –0.02 (–0.08 to 0.03) | 0.41 | ||

| Waist circumference (z score¶) | 1027 | 0.08 (1.04) | 954 | –0.08 (0.94) | 1981 | –0.12 (–0.23 to –0.01) | 0.03 | ||

| Servings of snacks (No/day) | 1097 | 2.46 (1.59) | 1024 | 2.24 (1.49) | 2121 | –0.22 (–0.38 to –0.05) | 0.01 | ||

| Servings of high fat foods (No/day) | 1097 | 0.88 (0.96) | 1024 | 0.79 (0.97) | 2121 | –0.10 (–0.24 to 0.03) | 0.13 | ||

| Servings of high energy drinks (No/day) | 1097 | 2.45 (1.61) | 1024 | 2.21 (1.44) | 2121 | –0.26 (–0.43 to –0.10) | 0.002 | ||

| Binary outcomes | |||||||||

| Generally overweight/obese | 945 | 198 (21.05%) | 880 | 166 (18.9%) | 1825 | 0.89 (0.61 to 1.31) | 0.56 | ||

| Centrally overweight/obese | 1027 | 510 (49.7%) | 954 | 416 (43.6%) | 1981 | 0.72 (0.50 to 1.04) | 0.08 | ||

MVPA=moderate or vigorous physical activity; Np=number of participants.

In these analyses, participants were included for each outcome if they had a follow-up measurement of that outcome; for missing baseline data, an indicator variable was used,46 which means that for each outcome participants are included even if they do not have a baseline measurement.

*Estimated using multi-level models to account for clustering (non-independence) among children from same school; multi-level multivariable linear regression was used for effects of intervention on continuously measured outcomes and multi-level multivariable logistic regression was used for binary outcomes; baseline/school stratifying variables were age, sex, baseline measure of outcome under consideration, school involvement in other health promoting behaviours, and school area level deprivation.

†P<0.05 indicates statistical significance.

‡Assessed by accelerometer.

§P<0.01 indicates statistical significance after account taken of multiple testing.

¶Internally standardised.

The sensitivity analyses that we did to explore assumptions about missing data produced results that were consistent with the main analyses (supplementary tables B to E). When we looked separately at time spent in moderate or vigorous physical activity and time spent in sedentary behaviour by weekday and weekend, the results were consistent with each other and with the main results (both P>0.2 for difference between the two estimates; supplementary table F).

Table 3 shows the results of the per protocol analyses for primary and secondary outcomes. In these analyses, children from 16 classes in 12 of the 30 intervention schools were excluded because their teacher had delivered fewer than 70% of the lessons. The results of the per protocol analyses were broadly consistent with those of the intention to treat analyses, with no evidence of effect on the three primary outcomes or most of the secondary outcomes. As with the intention to treat analyses, we found evidence of a beneficial effect on self reported screen viewing on Saturdays and consumption of high energy drinks. The point estimate for the reduction in self reported consumption of snacks was similar to that seen in the intention to treat analysis, but the strength of evidence was marginal, particularly after multiple testing was taken into account.

Table 3.

Per protocol analyses of effect of AFLY5 intervention on primary and secondary outcomes assessed immediately after end of intervention

| Outcomes (primary/secondary) | Control (reference) group | Intervention group | Main comparison between two groups (intervention v control) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Np | Mean (SD) or No (%) | Np | Mean (SD) or No (%) | Np | Difference in means or odds ratio (95% CI)* | P value | |||

| Continuous outcomes (primary)† | |||||||||

| Time spent in MVPA‡ (min/day) | 649 | 56.65 (23.42) | 424 | 54.39 (21.55) | 1073 | –2.12 (–6.70 to 2.47) | 0.37 | ||

| Time spent in sedentary behaviour (min/day) | 649 | 451.84 (65.40) | 424 | 453.68 (67.42) | 1073 | 0.44 (–10.32 to 11.21) | 0.94 | ||

| Servings of fruit and vegetables (No/day) | 1097 | 1.81 (1.55) | 722 | 1.99 (1.77) | 1819 | 0.18 (–0.05 to 0.41) | 0.12 | ||

| Continuous outcomes (secondary)§ | |||||||||

| Time spent screen viewing (min/day weekday) | 1097 | 145.45 (133.95) | 722 | 124.20 (118.88) | 1819 | –19.11 (–39.59 to 1.37) | 0.07 | ||

| Time spent screen viewing (min/day Saturday) | 1097 | 175.64 (171.79) | 722 |

146.99 (147.15) | 1819 | –24.61 (–42.06 to –7.17) | 0.006 | ||

| Body mass index (z score¶) | 945 | 0.05 (1.03) | 613 | –0.05 (0.96) | 1558 | –0.01 (–0.07 to 0.05) | 0.82 | ||

| Waist circumference (z score¶) | 1027 | 0.08 (1.04) | 665 | –0.06 (0.94) | 1692 | –0.09 (–0.21 to 0.04) | 0.17 | ||

| Servings of snacks (No/day) | 1097 | 2.46 (1.59) | 722 | 2.29 (1.54) | 1819 | –0.18 (–0.38 to 0.02) | 0.07 | ||

| Servings of high fat foods (No/day) | 1097 | 0.88 (0.96) | 722 | 0.86 (0.99) | 1819 | –0.04 (–0.19 to 0.11) | 0.62 | ||

| Servings of high energy drinks (No/day) | 1097 | 2.45 (1.61) | 722 | 2.18 (1.44) | 1819 | –0.29 (–0.48 to -0.09) | 0.005 | ||

| Binary outcomes | |||||||||

| Generally overweight/obese | 945 | 198 (21.0%) | 613 | 111 (18.1%) | 1558 | 0.96 (0.62 to 1.48) | 0.84 | ||

| Centrally overweight/obese | 1027 | 510 (49.7%) | 665 | 295 (44.4%) | 1692 | 0.87 (0.58 to 1.32) | 0.52 | ||

MVPA=moderate or vigorous physical activity; Np=number of participants.

Per protocol analysis defined as teaching at least 70% (11/16) AFLY5 lessons. All participants from intervention classes where teacher taught fewer than 11 (70%) lessons were excluded from these analyses (children from 16 classes (from 12 schools) were excluded).

In these analyses, after removal of schools that did not teach at least 11 out of 16 lessons, participants were included for each outcome if they had a follow-up measurement of that outcome; for missing baseline data, an indicator variable was used,46 which means that for each outcome participants are included even if they do not have a baseline measurement.

*Estimated using multi-level models to account for clustering (non-independence) among children from same school; multi-level multivariable linear regression was used for effects of intervention on continuously measured outcomes and multi-level multivariable logistic regression was used for binary outcomes; baseline/school stratifying variables were age, sex, baseline measure of outcome under consideration, school involvement in other health promoting behaviours, and school area level deprivation.

†P<0.05 indicates statistical significance.

‡Assessed by accelerometer.

§P<0.01 indicates statistical significance after account taken of multiple testing.

¶Internally standardised.

Discussion

In this school based cluster randomised controlled trial, which is one of the largest to date and which takes account of the limitations of previous randomised controlled trials, we found no evidence of effect on our three primary outcomes—accelerometer assessed time spent in moderate or vigorous physical activity, accelerometer assessed time spent in sedentary behaviour, and consumption of fruit and vegetables. After taking account of multiple testing, we found that the intervention was effective in reducing child reported time spent screen viewing at weekends and self reported consumption of snacks and of high energy drinks, but we saw no effect on six other secondary outcomes.

Strengths and limitations of study

The study design was carefully developed to take account of known sources of bias in other randomised controlled trials in this area. A protocol was published before recruitment started, and a detailed analysis plan (to which we have adhered) was written before any access to the study data. We developed an intervention according to guidelines for complex interventions (see rationale for the intervention in the methods section)22 23 and that we have shown was feasible to deliver and promising in our pilot randomised controlled trial.32 Our sample size calculation, which took account of the likely degree of clustering from our pilot and feasibility studies and the number of outcomes that we planned to assess, indicated that we needed a total of 1500 participants from 60 schools to be randomised and 1275 included in the primary analyses.19 20 For all outcomes, except those related to accelerometer data, we achieved considerably higher numbers than this. The number included in the main analyses for accelerometer based data was very slightly (by 0.02%) lower than this at 1252. Sample size calculations are an approximation of the numbers needed, and we doubt that such a small difference will have had a major effect on our conclusions. Furthermore, wear time was similar in children in intervention and control schools; and in sensitivity analyses using different approaches to dealing with missing data and which included 2221 children even for the accelerometer outcomes (supplementary tables D and E), the results were essentially the same as in the main analysis. One school refused to deliver any of the intervention, and others did not deliver all of the lessons. However, our per protocol analysis, which did not differ from the main intention to treat analysis, shows that this does not explain the null results.

Comparisons with other studies

Our study builds on previous randomised controlled trials in this area by overcoming the identified and important weaknesses of those previous studies.11 12 13 14 15 16 It is one of the few randomised controlled trials to have used accelerometers (rather than self or parental report) to assess the effect of an intervention on moderate or vigorous physical activity in children,11 12 and it is the only one that we are aware of to use accelerometers to assess sedentary behaviours.15 16 Previous trials that have used self report for these outcomes have also been criticised for the lack of blinding in relation to the intervention and the likelihood that results might have been exaggerated by children or their parents knowing that they were in the intervention arm of the study. Thus, the lack of effect of the AFLY5 intervention on moderate or vigorous physical activity and sedentary behaviour might reflect a true assessment of school based interventions that fit easily within the main school curriculum and are relatively inexpensive. Previous trials that suggested benefit from such interventions, including the ones that our intervention are based on,26 27 were potentially biased by the use of self or parental report, lack of blinding of outcome assessments, and other limitations.

Meaning of study findings

Several reasons may explain why our intervention, and other similar interventions, has not been effective. Firstly, the intervention itself might be inadequate. As described in the section on the rationale for this study, we began developing it, in line with guidance for complex interventions, in 2006, some five years before the start of the main trial reported here. This time difference reflects the requirements for developing, feasibility testing, and piloting the intervention, as well as then obtaining funds for the full trial. Over these years, the promise shown in earlier feasibility and pilot work may have diminished as other local and national interventions aimed at promoting healthy levels of physical activity and diet are implemented in schools or through other settings or forms aimed at children.

Secondly, and related to our first point, to have an effect on contemporary children more intensive behavioural change interventions, or interventions that target the school environment as well as self efficacy and knowledge in the children, may be necessary. A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials and clinical trials of any intervention aimed at increasing objectively assessed physical activity in children found a small increase in levels of activity in those receiving interventions but described the magnitude of this as being of small to negligible clinical importance.12 Heterogeneity existed between studies, with on average more than half of the variability of time spent in moderate or vigorous physical activity being due to between study differences (I2=52%). However, in detailed subgroup and meta-regression analyses, characteristics of the intervention did not explain this heterogeneity; studies in overweight/obese children showed a greater effect than did those in general populations of children, and some evidence suggested that studies with smaller sample sizes had stronger effects.12 We are aware of only one further trial that has been published since that review. A recent randomised controlled trial conducted in Australia, in which the intervention consisted of altering school playgrounds and adding “loose materials” that promoted creative free play without an emphasis on sport or activity per se, together with work with parents and teachers to address their concerns about children being allowed to play freely, resulted in a small increase in time spent in moderate or vigorous physical activity,47 of a similar magnitude to that seen in the earlier meta-analysis.12 Similarly, for our other primary outcomes—sedentary behaviour and fruit and vegetable consumption—we are not aware of any evidence from well conducted randomised controlled trials that more intensive interventions aimed at individual children produce important effects. Furthermore, our pilot and feasibility work with teachers and parents clearly showed that a more intensive intervention in school or with parents than what was included in AFLY5 would not have been acceptable.32 33 34

Thirdly, in current environments in which car transport is increasingly the norm and access to energy dense cheap food is widespread, a more upstream societal and environmental approach, together with interventions targeted at schools and individual children, may be necessary to increase children’s physical activity and fruit and vegetable consumption.48 Twin based studies suggest that fidgeting (one form of activity that might have health benefits) and enjoyment of physical activity in children is strongly genetically heritable but that objectively assessed time spent in moderate or vigorous physical activity or parental report of time spent in activity is largely determined by shared environment.49 50 In such studies, “environment” would include the school environment and what was taught there, as well as familial and broader social environments, but the difference between enjoyment of physical activity (largely genetic) and actual participation (largely environmental) suggests an important role for supportive physical environments that do not require children to consciously think of the activity as something they are enjoying or not.49 50 51

We found beneficial effects of the intervention on three of the secondary outcomes—self reported weekend screen viewing and consumption of high energy drinks and snacks—even after taking account of multiple testing. These could be the result of reporting bias by the children. However, we made every effort for the intervention to be built into normal school lessons in such a way that it did not alert children to the fact that they were in an intervention school, and the fieldworkers who collected data from the children were all blinded to school allocation. The beneficial effect for screen viewing might have been influenced by the slight imbalance at baseline for this characteristic, but we adjusted for this difference in all analyses. The effect was specific for just these three outcomes and not for other self reported outcomes (screen viewing on weekdays, consumption of fruit and vegetables, and consumption of high fat foods). Children may feel more able to modify these behaviours than others that we have assessed, although we have no direct evidence to support this.

Our findings have implications for researchers, policy makers, public health practitioners, and doctors. They suggest that a theory based and well developed school level intervention, which is acceptable to teachers and parents, and which can be delivered to all children and does not disrupt normal lessons, does not increase children’s levels of physical activity or fruit and vegetable consumption and does not decrease sedentary behaviour. The rapidly changing environment and cultures related to behaviours such as these highlight an inherent difficulty in the time required to develop, pilot, and then obtain funding for large scale randomised controlled trials, which may mean that by the time the trial starts the intervention is dated. They also suggest that more intensive interventions at the level of individual children, but also at family, school, and societal levels, are likely to be required to ensure that children can adopt healthy lifestyles.

Unanswered questions and future research

Questions of how to reduce the time from initial development of a complex public health intervention to evaluating it in a full scale randomised controlled trial, without compromising the quality of the development of the intervention or study design, need to be considered by government, funders, and the research community. Policy makers need to recognise that, although schools are a means of targeting the vast majority of children, relatively simple interventions at the level of the school are unlikely to be effective. Consideration of more intensive school based interventions will need to take account of the cost, not just financial but also in terms of possible disruptions to learning, and ways of making these acceptable to parents, teachers, and children. Researchers, policy makers, clinicians, public health practitioners, and other stakeholders also need to consider how best to undertake timely development and evaluations of interventions that have a broader and more upstream approach.48 51

What is already known on this topic

School based interventions to encourage healthy lifestyles have the potential to reach the vast majority of children

Several systematic reviews of randomised controlled trials have found some evidence of the effectiveness of these interventions with respect to increasing physical activity, reducing sedentary behaviour, and increasing fruit and vegetable consumption

However, these reviews have noted the poor quality of many of the trials and cautioned that the results may exaggerate the truth

What this study adds

This large cluster randomised controlled trial found no evidence that a school based intervention was effective in increasing physical activity or decreasing sedentary behaviour when both were assessed using accelerometers

The intervention also had no effect on child reported fruit and vegetable consumption

More intense behavioural interventions with school children or more upstream societal, family, and school environmental and cultural change may be required

We thank all the students and teaching staff who took part in the Active for Life Year 5 study. We thank all of the AFLY5 staff, including fieldworkers, administrative staff, computing and data management staff, and the trainers who provided teacher training. We thank Hugh Annett (retired director of public health, NHS Bristol and Bristol City Council), Annie Hudson (former strategic director for children, young people and skills, Bristol City Council), and Stella Smith (strategic director for children, young people and skills, North Somerset City Council) for their support of AFLY5. We also thank the chair and members of the Trial Steering Committee for their advice and support. The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and not necessarily anyone in this acknowledgment list

Contributors: RRK and LDH contributed equally to this work. DAL, RRK, RJ, RC, TJP, CRC, JM, and SMN were involved in the design of the study and in seeking funding for it. DAL, RRK, and SW were responsible for the conduct of the study. DAL, RRK, and LDH wrote the first draft of the paper, and DAL coordinated contributions from other co-authors. DAL wrote the analysis plan used for this paper, and LDH completed all analyses. SW managed the AFLY5 data collection with input from DAL, RKK, RJ, and other members of the study team. All authors made critical comments on drafts of the paper. DAL is the guarantor.

Funding: The AFLY5 RCT is funded by the UK National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Public Health Research Programme (09/3005/04), which also paid the salary of SW. DAL and LDH work in a unit that receives funds from the UK Medical Research Council (MRC) (MC_UU_12013/5). RRK and RC work in Centre for the Development and Evaluation of Complex Interventions for Public Health Improvement (DECIPHer), which receives funding from the British Heart Foundation, Cancer Research UK, the Economic and Social Research Council (RES-590-28-0005), the MRC, the Welsh Assembly Government, and the Wellcome Trust (WT087640MA), under the auspices of the UK Clinical Research Collaboration. LDH is supported by a UK MRC population health scientist fellowship (G1002375). None of the funders had involvement in the Trial Steering Committee, data analysis, data interpretation, data collection, or writing of the paper. The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and not necessarily of the funding bodies listed here.

Completing interests: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf (available on request from the corresponding author) and declare: support from research funders in accordance with the funding statement included in this manuscript; no financial relationships with any organisations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous three years; no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work, other than that RC is director of DECIPHer Impact, a not for profit company that is wholly owned by the Universities of Bristol and Cardiff and whose purpose is to licence and support the implementation of evidenced based health promotion interventions.

Ethical approval: Ethical approval was obtained from the University of Bristol Faculty of Medicine and Dentistry Committee for Ethics (reference number 101115).

Transparency declaration: DAL affirms that the manuscript is an honest, accurate, and transparent account of the study being reported; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted; and that any discrepancies from the study as planned have been explained.

Data sharing: Data from the AFLY5 study are openly not available to external collaborators until the NIHR (funders) monograph has been completed and accepted. However, we do encourage anyone who would like to collaborate with us to contact the corresponding author. From late 2015 we would be happy for external collaborators to access these data according to data transfer agreements that will have been developed by then. Information regarding this access will be made available on the study website from early 2015 (www.bristol.ac.uk/social-community-medicine/projects/afl/).

Cite this as: BMJ 2014;348:g3256

Web Extra. Extra material supplied by the author

References

- 1.Lock K, Pomerleau J, Causer L, Altmann DR, McKee M. The global burden of disease attributable to low consumption of fruit and vegetables: implications for the global strategy on diet. Bull World Health Organ 2005;83:100-8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Maynard M, Gunnell D, Emmett P, Frankel S, Davey Smith G. Fruit, vegetables, and antioxidants in childhood and risk of adult cancer: the Boyd Orr cohort. J Epidemiol Community Health 2003;57:218-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ness AR, Maynard M, Frankel S, Smith GD, Frobisher C, Leary SD, et al. Diet in childhood and adult cardiovascular and all cause mortality: the Boyd Orr cohort. Heart 2005;91:894-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boreham C, Riddoch C. The physical activity, fitness and health of children. J Sports Sci 2001;19:915-29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Janssen I, Leblanc AG. Systematic review of the health benefits of physical activity and fitness in school-aged children and youth. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2010;7:40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ness AR, Leary SD, Mattocks C, Blair SN, Reilly JJ, Wells J, et al. Objectively measured physical activity and fat mass in a large cohort of children. PLoS Med 2007;4:e97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ekelund U, Luan J, Sherar LB, Esliger DW, Griew P, Cooper A, et al. Moderate to vigorous physical activity and sedentary time and cardiometabolic risk factors in children and adolescents. JAMA 2012;307:704-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Telama R. Tracking of physical activity from childhood to adulthood: a review. Obesity Facts 2009;2:187-95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maynard M, Gunnell D, Ness AR, Abraham L, Bates CJ, Blane D. What influences diet in early old age? Prospective and cross-sectional analyses of the Boyd Orr cohort. Eur J Public Health 2006;16:316-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Janz KF, Burns TL, Levy SM, for the Iowa Bone Development Study. Tracking of activity and sedentary behaviors in childhood: the Iowa Bone Development Study. Am J Prev Med 2005;29:171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dobbins M, Husson H, DeCorby K, LaRocca RL. School-based physical activity programs for promoting physical activity and fitness in children and adolescents aged 6 to 18. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013;2:CD007651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Metcalf B, Henley W, Wilkin T. Effectiveness of intervention on physical activity of children: systematic review and meta-analysis of controlled trials with objectively measured outcomes (EarlyBird 54). BMJ 2012;345:e5888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Delgado-Noguera M, Tort S, Martinez-Zapata MJ, Bonfill X. Primary school interventions to promote fruit and vegetable consumption: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Prev Med 2011;53:3-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Evans CE, Christian MS, Cleghorn CL, Greenwood DC, Cade JE. Systematic review and meta-analysis of school-based interventions to improve daily fruit and vegetable intake in children aged 5 to 12 y. Am J Clin Nutr 2012;96:889-901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.DeMattia L, Lemont L, Meurer L. Do interventions to limit sedentary behaviours change behaviour and reduce childhood obesity? A critical review of the literature. Obes Rev 2007;8:69-81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Van Grieken A, Ezendam NP, Paulis WD, van der Wouden JC, Raat H. Primary prevention of overweight in children and adolescents: a meta-analysis of the effectiveness of interventions aiming to decrease sedentary behaviour. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2012;9:61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mallam KM, Metcalf BS, Kirkby J, Voss LD, Wilkin TJ. Contribution of timetabled physical education to total physical activity in primary school children: cross sectional study. BMJ 2003;327:592-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cleland V, Dwyer T, Blizzard L, Venn A. The provision of compulsory school physical activity: associations with physical activity, fitness and overweight in childhood and twenty years later. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2008;5:14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lawlor DA, Jago R, Noble SM, Chittleborough CR, Campbell R, Mytton J, et al. The Active for Life Year 5 (AFLY5) school based cluster randomised controlled trial: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials 2011;12:181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lawlor DA, Peters TJ, Howe LD, Noble SM, Kipping RR, Jago R. The Active for Life Year 5 (AFLY5) school-based cluster randomised controlled trial protocol detailed statistical analysis plan. Trials 2013;14:234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Department for Communities and Local Government. The English Indices of Deprivation 2010. Stationery Office, 2011.

- 22.Medical Research Council. Developing and evaulating complex interventions: new guidance. MRC, 2008.

- 23.Baranowski T, Cerin E, Baranowski E. Steps in the design, development and formative evaluation of obesity prevention-related behaviour change trials. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2009;6:6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Promoting physical activity for children and young people. NICE public health guidance 17. NICE, 2009.

- 25.US Health Policy Gateway. Physical activity and fitness. http://ushealthpolicygateway.com/payer-trade-groups/health-promotion-disease-prevention/physical-activity-and-fitness/.

- 26.Wardle J, Henning Broderson N, Cole TJ, Jarvis MJ, Boniface DR. Development of adiposity in adolescence: five year longitudinal study of an ethnically and socioeconomically diverse sample of young people in Britain. BMJ 2006;332:1130-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Baker JL, Olsen LW, Sorensen TI. Childhood body-mass index and the risk of coronary heart disease in adulthood. N Engl J Med 2007;357:2329-37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gortmaker SL, Peterson K, Wiecha J, Sobol AM, Dixit S, Fox MK, et al. Reducing obesity via a school-based interdisciplinary intervention among youth: Planet Health. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 1999;153:409-18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gortmaker SL, Cheung LW, Peterson KE, Chomitz G, Cradle JH, Dart H, et al. Impact of a school-based interdisciplinary intervention on diet and physical activity among urban primary school children: eat well and keep moving. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 1999;153:975-83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bandura A. Social foundations of thought and action: a social cognitive theory. Prentice Hall, 1986.

- 31.Bandura A. Self-efficacy: the exercise of control. Freeman, 1997.

- 32.Kipping RR, Payne C, Lawlor DA. Randomised controlled trial adapting US school obesity prevention to England. Arch Dis Child 2008;93:469-73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kipping RR. Preventing childhood obesity [PhD thesis]. University of Bristol, 2010.

- 34.Kipping RR, Jago R, Lawlor DA. Developing parent involvement in a school-based child obesity prevention intervention: a qualitative study and process evaluation. J Public Health (Oxf) 2012;34:236-44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Johnson ST, Kuk JL, Mackenzie KA, Huang TT, Rosychuk RJ, Ball GD. Metabolic risk varies according to waist circumference measurement site in overweight boys and girls. J Pediatr 2010;156:247-52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cole TJ, Bellizzi MC, Flegal KM, Dietz WH. Establishing a standard definition for child overweight and obesity worldwide: international survey. BMJ 2000;320:1240-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McCarthy HD, Jarrett KV, Crawley HF. The development of waist circumference percentiles in British children aged 5.0-16.9 y. Eur J Clin Nutr 2001;55:902-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zimmet P, Alberti G, Kaufman F, Tajima N, Silink M, Arslanian S, et al. The metabolic syndrome in children and adolescents. Lancet 2007;369:2059-61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kipping RR, Jago R, Lawlor DA. Diet outcomes of a pilot school-based randomised controlled obesity prevention study with 9-10 year olds in England. Prev Med 2010;51:56-62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Edmunds LD, Ziebland S. Development and validation of the Day in the Life Questionnaire (DILQ) as a measure of fruit and vegetable questionnaire for 7-9 year olds. Health Educ Res 2002;17:211-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Moore GF, Tapper K, Murphy S, Clark R, Lynch R, Moore L. Validation of a self-completion measure of breakfast foods, snacks and fruits and vegetables consumed by 9- to 11-year-old schoolchildren. Eur J Clin Nutr 2007;6:420-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Campbell KJ, Crawford DA, Salmon J, Carver A, Garnett SP, Baur LA. Associations between the home food environment and obesity-promoting eating behaviors in adolescence. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2007;15:719-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Robinson TN. Reducing children’s television viewing to prevent obesity: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 1999;282:1561-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.White IR, Carpenter J, Horton NJ. Including all individuals is not enough: lessons for intention-to-treat analysis. Clin Trials 2012;9:396-407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.White IR, Horton NJ, Carpenter J, Pocock SJ. Strategy for intention to treat analysis in randomised trials with missing outcome data. BMJ 2011;342:d40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.White IR, Thompson SG. Adjusting for partially missing baseline measurements in randomized trials. Stat Med 2005;24:993-1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Engelen L, Bundy AC, Naughton G, Simpson JM, Bauman A, Ragen J, et al. Increasing physical activity in young primary school children—it’s child’s play: a cluster randomised controlled trial. Prev Med 2013;56:319-25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lawlor DA, Pearce N. The Vienna declaration on nutrition and non-communicable diseases. BMJ 2013;347:f4417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fisher A, van Jaarsveld CH, Llewellyn CH, Wardle J. Environmental influences on children’s physical activity: quantitative estimates using a twin design. PloS One 2011;5:e10110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Huppertz C, Bertel M, van Beijsterveldt CE, Boomsma DI, Hudziak JJ, de Geus EJ. The impact of shared environmental factors on exercise behaviour from age 7 to 12. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2012;44:2025-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hammer M, Fisher A. Are interventions to promote physical activity in children a waste of time? No, finding an intervention that works is essential. BMJ 2012;345:e6320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.