Abstract

Objective To investigate whether the policy of increasing National Health Service funding to a greater extent in deprived areas in England compared with more affluent areas led to a reduction in geographical inequalities in mortality amenable to healthcare.

Design Longitudinal ecological study.

Setting 324 lower tier local authorities in England, classified by their baseline level of deprivation.

Intervention Differential trends in NHS funds allocated to local areas resulting from the NHS resource allocation policy in England between 2001 and 2011.

Main outcome measure Trends in mortality from causes considered amenable to healthcare in local authority areas in England. Using multivariate regression, we estimated the reduction in mortality that was associated with the allocation of additional NHS resources in these areas.

Results Between 2001 and 2011 the increase in NHS resources to deprived areas accounted for a reduction in the gap between deprived and affluent areas in male mortality amenable to healthcare of 35 deaths per 100 000 population (95% confidence interval 27 to 42) and female mortality of 16 deaths per 100 000 (10 to 21). This explained 85% of the total reduction of absolute inequality in mortality amenable to healthcare during this time. Each additional £10m of resources allocated to deprived areas was associated with a reduction in 4 deaths in males per 100 000 (3.1 to 4.9) and 1.8 deaths in females per 100 000 (1.1 to 2.4). The association between absolute increases in NHS resources and improvements in mortality amenable to healthcare in more affluent areas was not significant.

Conclusion Between 2001 and 2011, the NHS health inequalities policy of increasing the proportion of resources allocated to deprived areas compared with more affluent areas was associated with a reduction in absolute health inequalities from causes amenable to healthcare. Dropping this policy may widen inequalities.

Introduction

Expenditure on the National Health Service in England as a whole has increased each year since its establishment, although this trend accelerated between 1999 and 2011.1 These additional resources led to increased activity in hospitals and primary care, decreased waiting times, improved survival, and improvements in the control of chronic conditions.2 The extent of the increase in expenditure differed across the country, with some areas experiencing greater increases than others.

Many countries experience noticeable inequalities in health between regions, often as a result of differing levels of socioeconomic deprivation.3 One policy approach to deal with these spatial inequalities is to allocate health service resources in ways that take into account these differences in health need.4 In England, central funding for the NHS raised through taxation is allocated to local commissioning organisations that provide or purchase primary, community, and secondary health services on behalf of their resident populations. The level of resources each commissioning organisation receives is determined by a national formula. Since the 1970s several different formulas have been used in an attempt to allocate resources more equitably to the commissioning organisations, based on the level of need in their populations.5 These local commissioning organisations then decide on how these resources are used based on their assessment of the needs of their populations.

In 1999 the UK government introduced a new objective for the allocation of resources in the NHS in England: “to contribute to the reduction in avoidable health inequalities.”6 To better achieve this objective a health inequalities component was introduced into the allocation formula in 2002, which targeted more resources at deprived areas.7 As a consequence, increases in allocations since that time have tended to favour more deprived areas. The local NHS commissioning organisations in these areas were free to use these additional resources to purchase primary or secondary healthcare or public health services, to better meet the needs of their populations and improve the quality of care they received.

This health inequalities approach to resource allocation was part of a wider strategy to reduce inequalities in health in England. In particular this strategy targeted the fifth of local authorities with the worst health and deprivation indicators (the spearhead group). Although the resource allocation policy was not specific to these areas, the spearhead areas did receive a greater increase in NHS resources than non-spearhead areas, because of their level of deprivation. These spearhead areas also received other additional support, including interventions to reduce social exclusion and intensive assistance through the national health inequalities support team.8

The policy of using the resource allocation mechanism to reduce health inequalities is based on the assumption that additional healthcare expenditure translates into improved population health outcomes. This clearly depends on the quality and effectiveness of care delivered and whether it tackles health needs. Although several reviews found little evidence of an association between healthcare expenditure and variations in mortality between countries,9 10 11 some studies that have investigated changes over time within countries where health service access is primarily based on need (rather than ability to pay), have found that increased investment of healthcare resources is associated with improved outcomes.12 13 14 However these studies have largely investigated the average effects of healthcare expenditure at the country or provincial level and have not assessed impacts on health inequalities. A recent study analysing differences in the trend in healthcare expenditure in each of the countries of the United Kingdom (England, Wales, Northern Ireland, and Scotland), found that since 1999 increased expenditure in England compared with the rest of the country was associated with an increase in the rate of decline of mortality amenable to healthcare.15 Our study extends this analysis by analysing the health inequalities impact of a specific policy to allocate additional resources to more deprived areas within England.

Recently, a great deal of debate has been about whether allocation of NHS resources in England should give greater weight to age compared with deprivation as an indicator of health need.16 17 18 19 Age has always been a major component of the resource allocation formula; however, concerns have been raised that the trend in resource allocation, since the introduction of the 1999 health inequalities policy, has not sufficiently taken into account increased demand for healthcare in wealthier areas, which, although they tend to have healthier populations, also tend to have older populations because residents live longer.

In 2012, the Advisory Committee on Resource Allocation proposed a new person based formula that removed the health inequalities component. In December 2012, NHS England decided against the implementation of this formula because of concern that, as it would increase the proportion of resources allocated to areas with better health outcomes, it was inconsistent with the organisation’s responsibilities to reduce inequalities in outcomes from NHS care.20 After a fundamental review of allocations policy in 2013, NHS England implemented a new formula, which combines the 2012 person based formula with a measure of “unmet need.” Even with this adjustment, however, the new formula gives less weight to deprived areas than does the current pattern of funding. As a result, planned NHS funding for local areas is set to decrease to a greater extent in more deprived areas compared with more affluent areas.21

Although one commentator has asserted that this health inequalities objective for the allocation of NHS resources, introduced in England in 1999, has had no effect,22 to our knowledge, no empirical investigation supports that assertion. A fundamentally important question to inform this debate is whether this 1999 policy did successfully reduce inequalities in health outcomes. We investigated whether this policy of increasing NHS funding to a greater extent in more deprived areas with the worst health outcomes, led to a reduction in geographical health inequalities in England.

Methods

Setting

We used aggregated data between 2001 and 2011 on 324 lower tier local authorities in England based on 2009 boundaries. We excluded the City of London and the Isles of Scilly because of their small populations.

Data sources

The main outcome variable in our analysis was male and female mortality from causes amenable to healthcare in people aged less than 75 years in each local authority, for 2001 to 2011, which we obtained from the NHS Information Centre indicator portal.23 Amenable mortality is defined as mortality from causes for which there is evidence of preventability given timely, appropriate access to high quality care.9 It includes deaths classified by a set of underlying causes within specific age groups (see supplementary appendix 1 on bmj.com). The concept has been widely used as a tool to track the quality and performance of health systems over time.9 For additional analysis we also obtained data on years of life lost from causes amenable to healthcare, which was only available from 2003; mortality from causes amenable to healthcare excluding ischaemic heart disease; and mortality from causes other than those considered amenable to healthcare (that is, not amenable).

Our main exposure variable was the allocation of NHS funds to the local commissioning organisations (health authorities or primary care trusts) responsible for each local authority population for 2001 to 2011, obtained from the Department of Health.24 25 To provide a consistent time series of allocations and outcomes, we mapped allocations for local commissioning organisations to local authority populations. Where these organisations spanned more than one local authority, we apportioned the total allocation to each local authority based on their population size, using look-up tables provided by the UK Data Archive.26 We adjusted the allocation for each local authority in each year to 2012 prices using the gross domestic product deflator.27 We used these data along with Office for National Statistics (ONS) population estimates to calculate the NHS allocation per head of population for each local authority.

We have previously shown that local authority mortality trends are associated with trends in unemployment and household income.28 To control for these trends in our analysis we obtained data on the unemployment benefit claimant rate and average gross disposable household income for each year in each local authority, from the ONS.29 30

Analysis

We initially investigated the trends in NHS allocation per head of population as well as trends in mortality from causes amenable to healthcare and mortality not amenable to healthcare, within the 20% most deprived and 20% most affluent local authorities We defined these two groups based on the income deprivation component of the indices of multiple deprivation in 2000.31

There has been some debate about whether relative or absolute measures should be used to measure progress in dealing with inequalities, with leading experts arguing that absolute measures are more relevant to inform policy making.32 Others, however, have argued that relative measures should also be used,33 and the Global Commission on the Social Determinants of Health and other guidance recommends that both measures are assessed.34 35 36 37 We therefore calculated the change in resource allocation, change in mortality, and trends in inequalities in both absolute and relative terms. We assessed the change in inequalities due to mortality amenable to healthcare by comparing the absolute and relative differences in mortality between deprived and affluent areas between 2001 and 2011. We further explored the unadjusted association between the average annual change in NHS allocation and mortality amenable to healthcare in each local authority.

Finally, we used linear regression models to estimate the association between change in NHS allocation and changes in mortality after adjusting for confounding factors. As there are potentially unobserved confounders that vary between local authorities, we used a fixed effects approach to remove these differences between local authorities.38 This conservative approach involves including dummy variables for each local authority to assess the association between change in NHS allocations and change in mortality within each local authority. We included an annual trend term to adjust for the national long term trend in mortality. Based on our previous research28 we hypothesised that the effect of additional investment in healthcare may differ depending on the social circumstances of the population. We therefore included an interaction term between deprivation level (fifths of indices of multiple deprivation) and the allocation per head of population, allowing the association between change in NHS allocation and change in mortality to vary by level of deprivation. We used robust clustered standard errors to reflect the fact that populations were not sampled independently and to ensure that standard errors were robust to serial correlation in the data. To control for differences in economic trends between areas we included the annual gross disposable household income and unemployment claimant rate for each local authority in the model. We estimated the models separately using male and female mortality as the outcome (see supplementary appendix 2 for model formulas).

Robustness tests

We subjected our analysis to several tests to assess the robustness of our findings. Using standard regression diagnostics we assessed whether the association between absolute change in NHS funds and absolute change in mortality amenable to healthcare was linear (see supplementary appendix 3). To assess whether our models were sensitive to this assumption of linearity we also estimated models with our variables measured on a log scale, to investigate the association between relative (%) change in NHS resources and the relative (%) change in amenable mortality. We further adjusted this model for separate time trends in each local authority to test whether relative deviations from the linear trend in allocation in each local authority were associated with fluctuations in mortality (see supplementary appendix 4.)

To test the specificity and consistency of our analysis we also estimated models separately using years of life lost from causes amenable to healthcare, mortality from causes amenable to healthcare excluding ischaemic heart disease, and mortality from causes other than those considered amenable to healthcare as our outcomes. We hypothesised that we would find similar sized effects for different measures of mortality amenable to healthcare and no association between NHS resource allocation and mortality from causes not amenable to healthcare. To compare effect sizes across different outcomes we used standardised coefficients. (see supplementary appendix 4). As there were other, non-NHS interventions in spearhead areas during this period that may have influenced mortality, we estimated additional models, controlling for separate trends in mortality amenable to healthcare in spearhead and non-spearhead areas (see supplementary appendix 4).

Results

Trend in NHS resource allocation and inequalities in mortality amenable to healthcare

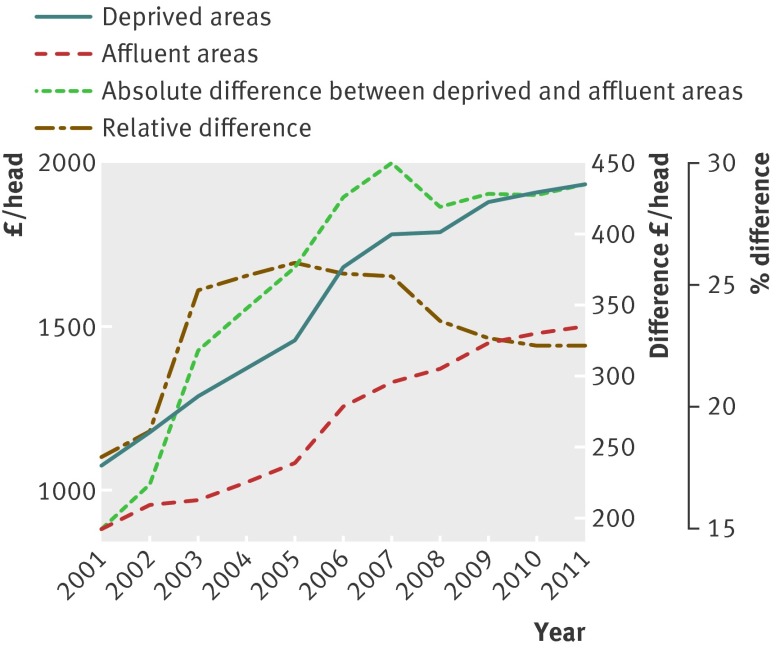

The allocation of NHS resources increased in real terms in the most deprived areas: by £865 (€1053; $1465)/head, from £1074/head in 2001 to £1938/head in 2011, representing an 81% increase. In more affluent areas allocations still increased, but to a lesser extent: by £621/head, from £881/head in 2001 to £1502/head in 2011: an increase of 70% (fig 1). In both areas real terms resources per head increased each year until 2011.

Fig 1 Trend in NHS allocation per head in deprived and affluent areas and difference between the two, indicating how the level of resources allocated to deprived areas compared with affluent areas, has increased over time

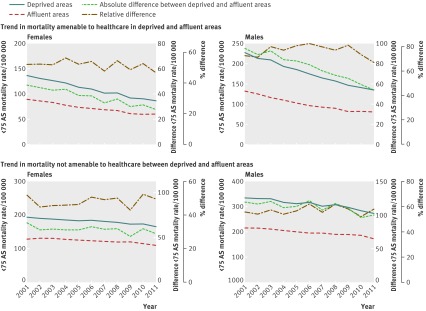

Between 2001 and 2011 mortality rates from causes amenable to healthcare and from causes not amenable to healthcare remained higher in deprived areas than in the more affluent areas. Mortality from causes amenable to healthcare fell in both groups, but this decline in absolute terms was greater in the more deprived areas. Mortality in males from these causes in deprived areas fell by 92 deaths, from 227 to 135 per 100 000 population, a relative decline of 41%, while in more affluent areas it fell by 51 deaths, from 131 to 81 deaths per 100 000, a relative decline of 39%. Mortality in females in deprived areas fell by 50 deaths, from 137 to 87 per 100 000, a relative decline of 37%, while in more affluent areas it fell by 31 deaths, from 90 to 59 deaths per 100 000, a relative decline of 34%. The absolute difference in mortality amenable to healthcare between deprived and affluent areas nearly halved from 95 deaths in males per 100 000 and 47 deaths in females per 100 000 in 2001 to 54 deaths per 100 000 and 28 deaths per 100 000, respectively, in 2011 (fig 2). In relative terms the gap in male mortality amenable to healthcare declined slightly, from being 72% higher in deprived compared with affluent areas in 2001 to being 67% higher in 2011. Female mortality declined from being 52% higher in deprived areas in 2001 to being 47% higher in 2011. The level of inequality in male or female mortality due to causes not amenable to healthcare did not change noticeably in either absolute or relative terms (see fig 2).

Fig 2 Trends in mortality amenable and not amenable to healthcare in deprived and affluent areas and difference between the two, indicating how inequalities have changed over time (mortality calculated as weighted average for groups of local authorities). AS=age standardised

Association between increased allocation of NHS funds and declines in mortality amenable to healthcare

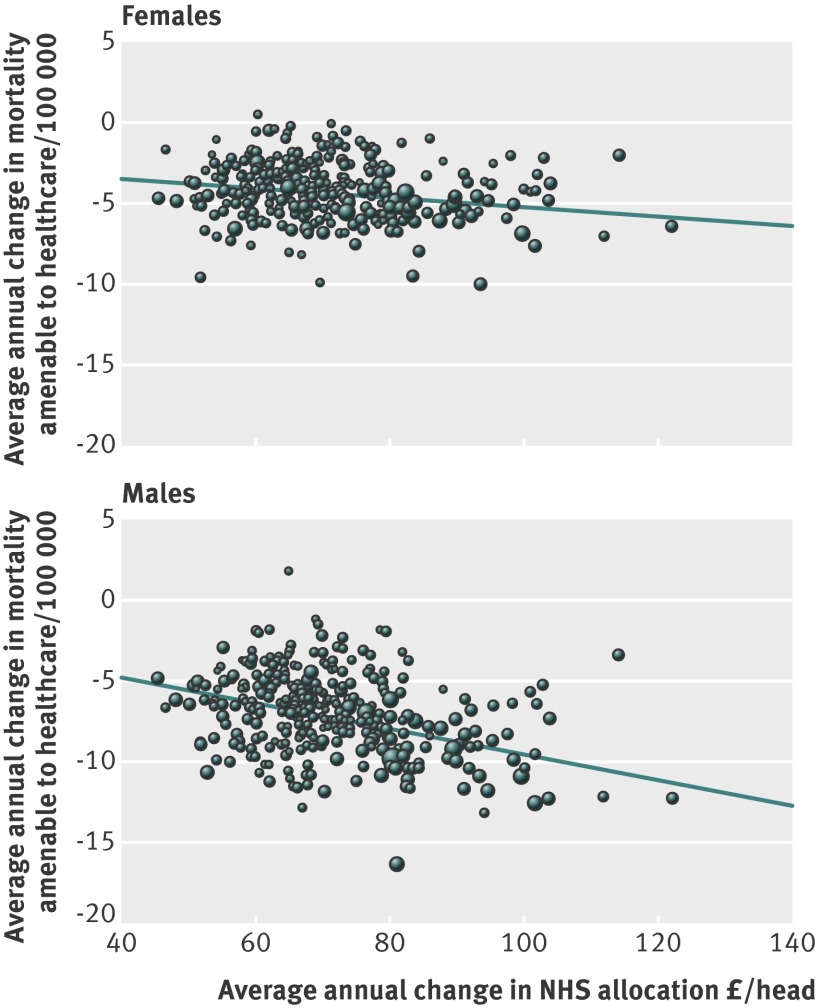

Figure 3 shows the association between the average annual increase in NHS allocation in each local authority area and the average annual decrease in male (r=−0.41, P<0.001) and female mortality (r=−0.24, P<0.001) from causes amenable to healthcare. Those areas that experienced the greatest absolute increase in NHS funds between 2001 and 2011 experienced the greatest absolute decline in both male and female mortality amenable to healthcare.

Fig 3 Association between average annual increase in NHS allocation in each local authority area and decrease in mortality amenable to healthcare between 2001 and 2011

This unadjusted correlation, however, cannot determine the independent association between increased NHS allocation and declines in amenable mortality. Our regression models indicated that absolute increases in the allocation of resources to each area was associated with absolute declines in mortality amenable to healthcare, when controlling for the national trend in mortality and differences in economic trends between areas (table). The size of this effect differed across levels of deprivation, with the greatest effect found in the most deprived areas. In the most deprived 20% of local authorities, each additional £10m of NHS resources was associated with a reduction in four male deaths per 100 000 (95% confidence interval 3.1 to 4.9) and 1.8 female deaths per 100 000 (1.1 to 2.4) from causes amenable to healthcare. In contrast, the association between the absolute increase in NHS resources and absolute improvements in male and female mortality amenable to healthcare in the more affluent parts of the country was not significant (first or second fifths, table).

Reduction in deaths from causes amenable to healthcare, 2001-11, associated with allocation of increased NHS funds.

| Local authority level of deprivation | Decrease in rates of deaths amenable to healthcare per 100 000 population (95% CI) for each £10m of additional NHS funds allocated | |

|---|---|---|

| Males | Females | |

| Most affluent (top fifth) | −0.1 (−1.1 to 0.9) | −0.4 (1.1 to −0.4) |

| Second fifth | 0.4 (−0.6 to 1.4) | −0.01 (−0.7 to 0.7) |

| Third fifth | 1.9 (1 to 2.8) | 0.9 (0.2 to 1.6) |

| Fourth fifth | 2.9 (1.8 to 3.9) | 1.2 (0.5 to 1.9) |

| Most deprived (bottom fifth) | 4.00 (3.1 to 4.9) | 1.8 (1.1 to 2.4) |

| R2 | 0.78 | 0.68 |

95% confidence intervals based on robust standard errors. Model based on equation 1 in supplementary appendix 2. Model adjusted for local authority, annual trend, annual unemployment rate, and annual average household income per head for each local authority.

The estimates in the table suggest that the increase in NHS resources in deprived areas accounted for a reduction in the absolute gap between deprived and affluent areas of 35 male deaths per 100 000 (27 to 42) and 16 female deaths per 100 000 (10 to 21, see supplementary appendix 5 for calculations) from causes amenable to healthcare. The total gap in male and female mortality amenable to healthcare between deprived and affluent areas decreased by 41 deaths and 19 deaths per 100 000, respectively. This indicates that much of the reduction in the gap between 2001 and 2011 could be explained by the trends in allocation of NHS resources during this time. As we had found in previous research,28 declines in unemployment and increasing trends in household income were also associated with reductions in mortality (see supplementary appendix 6). As we controlled for these in our regression models, the results indicate that the effect of increased NHS resources was over and above any effect from local economic trends.

Robustness tests

Conditional on the interaction with deprivation, the association between absolute change in NHS allocation and change in mortality amenable to healthcare was approximately linear (test for non-linearity: P=0.16, see regression diagnostic in supplementary appendix 3). This indicates that using a linear model comparing the absolute changes in our variables, as presented in the table, is appropriate. As a further test of whether our model was sensitive to this assumption we investigated the association between the relative increase in resources in an area and the relative decline in mortality by log transforming these variables. We found that each 10% increase in resources was associated with a 1.35% (95% confidence interval 0.61% to 2.1%) reduction in male mortality amenable to healthcare and a 0.85% (0.05% to 1.66%) reduction in female mortality. Evidence of any interaction between level of deprivation and the effect of a relative increase in funds on the relative decrease in mortality was lacking.

We tested the specificity and consistency of our findings using alternative specifications. Using potential years of life lost from causes amenable to healthcare as our outcome we found similar results to those using the under 75 year old mortality rate. Using mortality from causes amenable to healthcare excluding ischaemic heart disease we found similar effect sizes. The association in any of our models between increased NHS allocation and change in mortality from causes not amenable to healthcare was not significant. Controlling for separate trends in spearhead and non-spearhead areas did not substantially change our findings, nor did controlling for separate trends in each local authority (see supplementary appendix 4).

Discussion

Our study has shown that geographical inequalities in mortality from causes amenable to healthcare declined in absolute terms during the 10 year period in which NHS resource allocation policy was used explicitly “to contribute to the reduction of avoidable health inequalities.” However, in relative terms, inequalities remained fairly constant. Most of the observed reduction in absolute health inequality over this period can be explained statistically by this health inequalities policy. Each £1.00 of additional NHS resource allocated to the most deprived areas was associated with greater absolute improvements in mortality amenable to healthcare than each £1.00 of additional NHS resources invested in more affluent areas.

Strengths and limitations of this study

Several strengths in our analysis enhanced its validity. We analysed change over time within local authorities, providing more robust evidence than a simple cross sectional analysis. This enabled us to control for potentially unobserved confounders that vary between local authorities, as well as controlling for observed differences in economic trends. Further controlling for separate time trends in each local authority, we found our results were unchanged, indicating that they were unlikely to be explained by linear trends in unobserved confounders that vary between local authorities. As recommended in guidance for non-experimental studies 39 we used a non-equivalent dependent variable (mortality from causes not amenable to healthcare) to investigate the specificity of our analysis. Such variables are those that should not be influenced by a change in the exposure (that is, NHS allocation), but are likely to be influenced along with the outcome by unobserved confounding factors. Finding that change in NHS allocation was not associated with mortality from causes not amenable to healthcare but was associated with amenable mortality, strengthens the validity of our results.

However several limitations remain. We cannot rule out the possibility that the associations we observed were due to other confounding factors that we were not able to adjust for in our analysis. Other research has indicated that changes in risk factors (for example, smoking) rather than improvements in treatment explain a greater of proportion of the reduction in inequalities in ischaemic heart disease.40 However, when we excluded ischaemic heart disease from our analysis, the associations between increased allocations and reduction in mortality from other amenable causes remained.

During this time other non-NHS policies were implemented to tackle social exclusion in deprived areas. In particular those designated as spearhead areas in the government’s strategy to reduce health inequalities. These policies may have had an impact on health outcomes that could explain some of the narrowing of inequalities observed. However evaluations of some of the most substantial of these policies have not yet shown an impact on mortality,41 42 43 and when we further adjusted for separate effects in spearhead areas we found that additional NHS resources were associated with improved health outcomes independent of any spearhead effect (see supplementary appendix 4).

There are limitations with using mortality from causes amenable to healthcare as our primary outcome. Firstly, it is not possible to entirely disentangle the factors other than healthcare, such as socioeconomic conditions, that influence this outcome.44 However, our results were not changed when we adjusted for socioeconomic trends. Secondly, as this outcome only includes deaths up to the age of 75, it will not reflect reductions in mortality over age 75 or improvements in quality of life. Therefore our analysis may underestimate the full impact of resource increases, particularly for older age groups.45

Although there are limitations with using mortality amenable to healthcare as our primary outcome, it could be considered appropriate in this context as it has been selected by the government as an indicator of NHS performance, allowing performance of the NHS to be judged against its own objectives.15

Finally, our analysis assumes that contemporary inputs in term of additional resources are associated with contemporary outcomes and we did not seek to take lagged effects into account. This problem is unlikely to have a major effect on our results as our main exposure and outcome variables followed approximately linear trends over time, although these trends varied between areas.46

Implications for policy

Our results have important implications for current policy. At a time when there is important political debate about whether a resource allocation policy introduced in 1999 to reduce health inequalities should be discontinued,47 48 our analysis provides evidence that this policy contributed to a reduction in absolute differences in health between areas and led to relative inequalities remaining constant during a period when they could have widened.

There has been a great deal of debate about whether progress on health inequalities should be assessed in absolute or relative terms.35 49 Several leading experts in health inequalities have also concluded that absolute measures are of primary importance to policy makers, particularly for identifying major problems that need to be tackled.32 50 Absolute measures reflect the gain in terms of deaths prevented from a reduction in health inequalities for a given level of investment. When the overall level of mortality is falling, it is likely that relative inequalities will increase.51 In this context a declining rate difference (absolute measure) should be considered as evidence of progress, even when the rate ratio (relative measure) remains constant.51

Our study shows that increases in resources allocated to each area between 2001 and 2011 were associated with a reduction in mortality amenable to healthcare. This was true regardless of whether absolute or relative measures were used in the analysis. Our estimates predict that the greater increase in resources allocated to deprived areas compared with affluent areas will have narrowed inequalities during this time. We observe a noticeable decline in absolute inequalities in mortality, while relative inequalities remained fairly constant. In relative terms the resources allocated to deprived areas only increased by 10% more than those allocated to affluent areas. Our analysis indicates that we would only expect this to contribute to a small reduction in relative inequalities of 0.9% for female mortality and 1.35% for male mortality, which is consistent with what we observed.

Our findings therefore suggest that the resource allocation policy contributed to this reduction in absolute inequalities and may have helped relative inequalities remain constant rather than widen. If the resources available to deprived areas had increased at an even greater rate, our findings suggest that this could have led to a reduction in relative inequalities as well as to absolute inequalities.

It has been argued that in deprived communities a higher proportion of poor health is not amenable to healthcare and therefore increasing health service investment in more deprived areas may not be efficient if the goal is to improve the health of the poorest.22 Contrary to this argument, our analysis suggests that health service investment in poorer communities results in greater absolute benefits in terms of increased survival than investment in more affluent areas. We observed a greater health gain in deprived areas per additional £1.00 invested compared with more affluent areas, indicating that increasing NHS investment in deprived areas may be an efficient strategy to improve population health.

The new person based resource allocation formula, developed by Dixon et al52 and proposed by Advisory Committee on Resource Allocation, defines need largely in terms of past health service utilisation rather than as “a capacity to benefit.”53 Our results suggest that a better starting position may be to determine the pattern of resource allocation that will maximise benefits in terms of both improving average outcomes and reducing inequalities in outcomes. A 2013 report by the Kings Fund suggested that it may be time to use resource allocation as a tool to deliver wider policy objectives.54 Reducing avoidable health inequalities had been a policy objective for the past decade and our study offers evidence that this policy was successful. Under the Health and Social Care Act of 2012, NHS England remains tasked with reducing inequalities in healthcare outcomes. Our research suggests that continuing with a resource allocation policy that prioritises deprived areas should help the NHS achieve this goal in relation to mortality amenable to healthcare.

With the introduction of the 2012 Health and Social Care Act in England, responsibility for public health has moved from the NHS to local government. The secretary of state for health at the time said that council funding for public health should be spent on tackling poverty related health need, whereas the allocation of NHS resources to local commissioning organisations should reflect “what is likely to give rise to a demand for NHS services.”47 This downplaying of the role of the NHS in reducing inequalities in health outcomes, seems to be based on the premise that the NHS does not play an important role in reducing health inequalities. Our analysis, however, indicates that the health service in England may have made an important contribution to reducing geographical health inequalities over the past decade through the 1999 resource allocation policy.

Conclusions

The policy of allocating greater NHS resources to more deprived areas led to a reduction in absolute health inequalities in mortality amenable to healthcare. Investment of NHS resources in more deprived areas was associated with a greater improvement in outcomes than investment in more affluent areas. Our study suggests that any change in resource allocation policy that reduces the proportion of funding allocated to deprived areas may reverse this trend and widen geographical inequalities in mortality from these causes.

What is already known on this topic

The new health inequalities resource allocation policy, introduced in 1999 for the National Health Service in England, led to a greater increase, over the next decade, in NHS funding allocated to deprived areas compared with affluent areas

This was the first time anywhere in the world that health service resource allocation policy had been used to try and reduce inequalities in health outcomes

It is not known whether this policy was successful in contributing to a reduction of health inequalities

What this study adds

Between 2001 and 2011, the policy of increasing NHS funding at a greater rate in deprived areas than in more affluent areas was associated with a reduction in absolute health inequalities from causes amenable to healthcare, while relative inequalities remained constant

The association between additional NHS funds and reduced mortality was stronger in deprived areas than more affluent areas

Each £1.00 (€1.22; $1.70) of additional NHS resource invested in the most deprived areas was associated with greater improvements in mortality amenable to healthcare than each £1.00 of additional NHS resources invested in more affluent areas; this led to a narrowing of the gap between deprived and affluent areas in this health outcome

Contributors: BB is the lead author and guarantor. He planned the study, conducted the analysis, and led the drafting and revising of the manuscript. MMW and CB contributed to data interpretation, drafting of the manuscript, and revisions. All authors agreed the submitted version of the manuscript.

Funding: BB is supported by a National Institute for Health Research doctoral research fellowship (DRF-2009-02-12). The National Institute for Health Research had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. MMW is supported by the DEMETRIQ project, which is funded from the Commission of the European Communities seventh framework programme under grant agreement No 278511. The study does not necessarily reflect the commission’s views and in no way anticipates the commission’s future policy in this area.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf and declare: no support from any organisation for the submitted work; no financial relationships with any organisations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous three years; CB is a member of the Labour party, however, the authors have no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Ethical approval: Not required.

Data sharing: The statistical code and dataset available from the corresponding author (benbarr@liverpool.ac.uk).

Transparency: The lead author affirms that the manuscript is an honest, accurate, and transparent account of the study being reported; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted; and that any discrepancies from the study as planned have been explained.

Cite this as: BMJ 2014;348:g3231

Web Extra. Extra material supplied by the author

Supplementary information

References

- 1.Thompson G. NHS expenditure in England. Library of the House of Commons, 2009.

- 2.Bojke C, Castelli A, Grasic K, Street A. NHS productivity from 2004/5 to 2010/11. Centre for Health Economics, University of York, 2013.

- 3.Richardson E, Pearce J, Mitchell R, Shortt N, Tunstall H. Have regional inequalities in life expectancy widened within the European Union between 1991 and 2008? Eur J Public Health 2013, published online 27 Jun. 10.1093/eurpub/ckt084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gilson L, Doherty J, Loewenson R, Francis V. Knowledge network on health systems. WHO Commission on the Social Determinants of Health, 2007.

- 5.Diderichsen F, Varde E, Whitehead M. Resource allocation to health authorities: the quest for an equitable formula in Britain and Sweden. BMJ 1997;315:875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Department of Health. The NHS plan: a plan for investment : a plan for reform. Stationery Office, 2000.

- 7.Department of Health. Resource allocation: weighted capitation formula, 6th edn. DoH, 2008.

- 8.National Audit Office. Tackling inequalities in life expectancy in areas with the worst health and deprivation. Stationery Office, 2010

- 9.Nolte E, McKee M. Variations in amenable mortality. Trends in 16 high-income nations. Health Policy 2011;103:47-52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mackenbach JP, Bouvier-Colle MH, Jougla E. ‘Avoidable’ mortality and health services: a review of aggregate data studies. J Epidemiol Community Health 1990;44:106-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kunst A, Looman C, Mackenbach J. Medical care and regional mortality differences within the countries of the European Community. Eur J Popul 1988;4:223-45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Crémieux P-Y, Ouellette P, Pilon C. Health care spending as determinants of health outcomes. Health Econ 1999;8:627-39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nixon J, Ulmann P. The relationship between health care expenditure and health outcomes: evidence and caveats for a causal link. Eur J Health Econ 2006;7:7-18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Martin S, Rice N, Smith PC. Does health care spending improve health outcomes? Evidence from English programme budgeting data. J Health Econ 2008;27:826-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Desai M, Nolte E, Karanikolos M, Khoshaba B, McKee M. Measuring NHS performance 1990-2009 using amenable mortality: interpret with care. J Roy Soc Med 2011;104:370-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Asthana S. Lansley is right to say that age trumps poverty. Health Serv J 2012. www.hsj.co.uk/opinion/columnists/lansley-is-right-to-say-that-age-trumps-poverty/5044697.article. [PubMed]

- 17.Asthana S. Tensions between healthcare equity and health equity must be debated. BMJ 2012;344:e4133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bambra CL. Clear winners and losers are created by age only NHS resource allocation. BMJ 2012;344:e3593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bambra CL, Copeland A. Deprived areas will lose out with proposed new capitation formula. BMJ 2013;347:f6146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.NHS England. Fundamental review of allocations policy—annex D: terms of reference. NHS England, 2013.

- 21.Barr B, Taylor-Robinson D. Poor areas lose out most in new NHS budget allocation. BMJ 2014;348:g160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hawkes N. Allocation of NHS resources: are some patients more equal than others? BMJ 2012;344:e3362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.The NHS IC Indicator Portal. 2013. https://indicators.ic.nhs.uk/webview/.

- 24.Department of Health. Exposition books. 2013. http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/+/www.dh.gov.uk/en/Managingyourorganisation/Financeandplanning/Allocations/DH_091850.

- 25.Department of Health. Exposition book 2011-2012. 2013. www.gov.uk/government/publications/exposition-book-2011-2012.

- 26.Mimas UDS. GeoConvert, UK Data Service. 2013. http://geoconvert.mimas.ac.uk/index.htm.

- 27.Gov.UK. How to use the GDP deflator series, practical examples. 2013. www.gov.uk/government/publications/how-to-use-the-gdp-deflator-series-practical-examples.

- 28.Barr B, Taylor-Robinson D, Whitehead M. Impact on Health Inequalities of Rising Prosperity in England 1998-2007, and Implications for Performance Incentives: Longitudinal Ecological Study. BMJ 2012;345: e7831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Office for National Statistics. NOMIS—official labour market statistics. 2013. www.nomisweb.co.uk/.

- 30.Office for National Statistics. Regional accounts methodology guide. ONS, 2010.

- 31.Department of the Environment, Transport and the Regions (DETR). Indices of deprivation 2000. DETR, 2000. www.housing.detr.gov.uk.

- 32.Acheson D, Barker D, Chambers, J, Graham H, Marmot M, Whitehead M. Independent inquiry into inequalities in health: report. Stationery Office, 1998.

- 33.Low A. Importance of relative measures in policy on health inequalities. BMJ 2006;332:967-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mackenbach J, Kunst E. Measuring the magnitude of socio-economic inequalities in health: an overview of available measures illustrated with two examples from Europe. Soc Sci Med 1997;44:757-71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.King NB, Harper S, Young ME. Use of relative and absolute effect measures in reporting health inequalities: structured review. BMJ 2012;345:e5774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kunst AE, Bos V, Mackenbach J. Monitoring socio-economic inequalities in health in the European Union: guidelines and illustrations. Erasmus University, 2001.

- 37.Vågerö D, Erikson R. Socioeconomic inequalities in morbidity and mortality in western Europe. Lancet 1997;350:516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rabe-Hesketh S, Skrondal A. Multilevel and longitudinal modeling using Stata. 2nd edn. Stata Press, 2008.

- 39.Shadish WR, Cook TD, Campbell DT. Experimental and quasi-experimental designs for generalized causal inference. Houghton Mifflin, 2002.

- 40.Bajekal M, Scholes S, O’Flaherty M, Raine R, Norman P, Capewell S. Unequal trends in coronary heart disease mortality by socioeconomic circumstances, England 1982-2006: an analytical study. PLoS One 2013;8:e59608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Melhuish E, Belsky J, Leyland AH, Barnes J. Effects of fully-established Sure Start local programmes on 3-year-old children and their families living in England: a quasi-experimental observational study. Lancet 2008;372:1641-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Belsky J. Effects of Sure Start local programmes on children and families: early findings from a quasi-experimental, cross sectional study. BMJ 2006;332:1476-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stafford M, Nazroo J, Popay J, Whitehead M. Tackling inequalities in health: evaluating the New Deal for Communities initiative. J Epidemiol Community Health 2008;62:298-304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gibbons DC, Bindman AB, Soljak MA, Millett C, Majeed A. Defining primary care sensitive conditions: a necessity for effective primary care delivery? J Roy Soc Med 2012;105:422-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nolte E, McKee CM. Measuring the health of nations: updating an earlier analysis. Health Aff (Millwood) 2008;27:58-71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gravelle HSE, Backhouse ME. International cross-section analysis of the determination of mortality. Soc Sci Med 1987;25:427-41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.David Williams. Lansley: CCG allocations should be based on age, not poverty. Health Serv J 2012. www.hsj.co.uk/news/finance/lansley-ccg-allocations-should-be-based-on-age-not-poverty/5044219.article.

- 48.Wiggins K. Labour to force vote on CCG allocations. Health Serv J 2013. www.hsj.co.uk/news/labour-to-force-vote-on-ccg-allocations/5064399.article.

- 49.Houweling TA, Kunst AE, Huisman M, Mackenbach J. Using relative and absolute measures for monitoring health inequalities: experiences from cross-national analyses on maternal and child health. Int J Equity Health 2007;6:15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rose G, Khaw K, Marmot M. Rose’s strategy of preventive medicine: the complete original text. Oxford University Press, 2008.

- 51.Harper S, King NB, Meersman SC, Reichman ME, Breen N, Lynch J. Implicit value judgments in the measurement of health inequalities. Milbank Q 2010;88:4-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dixon J, Smith P, Gravelle H, Martin S, Bardsley N, Rice N, et al. A person based formula for allocating commissioning funds to general practices in England: development of a statistical model. BMJ 2011;343:d6608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mooney G, Houston S. An alternative approach to resource allocation: weighted capacity to benefit Plus MESH infrastructure. Appl Health Econ Health Policy 2004;3:29-33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Buck D, Dixon A. Improving the allocation of health resources in England. Kings Fund, 2013.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary information