Abstract

One of the attractions of molecular imaging using ‘smart’ bioactive contrast agents is the ability to provide non-invasive data on the spatial and temporal changes in the distribution and expression patterns of specific enzymes. The tools developed for that aim could potentially also be developed for functional imaging of enzyme activity itself, through quantitative analysis of the rapid dynamics of enzymatic conversion of these contrast agents. High molecular weight hyaluronan, the natural substrate of hyaluronidase, is a major antiangiogenic constituent of the extracellular matrix. Degradation by hyaluronidase yields low molecular weight fragments, which are proangiogenic. A novel contrast material, HA-GdDTPA-beads, was designed to provide a substrate analog of hyaluronidase in which relaxivity changes are induced by enzymatic degradation. We show here a first-order kinetic analysis of the time-dependent increase in R2 as a result of hyaluronidase activity. The changes in R2 and the measured relaxivity of intact HA-GdDTPA-beads (r2B) and HA-GdDTPA fragments (r2D) were utilized for derivation of the temporal drop in concentration of GdDTPA in HA-GdDTPA-beads as the consequence of the release of HA-GdDTPA fragments. The rate of dissociation of HA-GdDTPA from the beads showed typical bell-shaped temperature dependence between 7 and 36 °C with peak activity at 25 °C. The tools developed here for quantitative dynamic analysis of hyaluronidase activity by MRI would allow the use of activation of HA-GdDTPA-beads for the determination of the role of hyaluronidase in altering the angiogenic microenvironment of tumor micro metastases.

Keywords: hyaluronidase, bioactive contrast material, magnetic resonance imaging, angiogenesis

INTRODUCTION

Hyaluronan (HA), a high molecular weight linear glycosaminoglycan, composed of glucuronic acid and N-acetylglucosamine, is a major component of the extracellular matrix and provides a target for CD44-mediated adhesion of normal and cancer cells (1–3). High molecular weight hyaluronan is antiangiogenic and can prevent angiogenesis even in the presence of elevated expression of VEGF (4). Induction of angiogenesis can be induced through degradation of hyaluronan by hyaluronidase (5), leading to the generation of pro-angiogenic fragments (4). Hyaluronidases, the enzymes responsible for hyaluronan degradation, are broadly distributed. There are several hyaluronidases with different substrate specificities and optimal pH ranges (6–8). The main mammalian hyaluronidases studied are Hyal-1, Hyal-2 and PH-20. Hyal-1, also known as LUCA-1 (LUngCAncer-1), the major hyaluronidase found in the plasma and urine, is composed from two polypeptide chains: a 49 kDa peptide and an additional 8 kDa peptide added by post-translational glycosylation. Hyal-1 has 40% similarity to the sperm hyaluronidase (PH-20), cleaving HA to small tetra- and disaccharides (9).

Hyal-2 is mainly found on membranes and can be anchored to the plasma membrane by a glycosylphosphatidylinositol link or on lysosomes inside the cell, which originate from the cell membrane. Hyal-2 cleaves high molecular weight HA into 20 kDa fragments which are proangiogenic. Over expression of Hyal-2 was observed in breast and endometrial cancer (10,11), but can also accelerate apoptosis (12). Secretion of hyaluronidase by cancer cells can suppress or promote tumor progression, depending on the identity and expression level of the various family members (13–15). Thus, Hyal-1 was reported to show tumor suppressor activity (13), whereas Hyal-2 provides the intermediate HA fragments that induce angiogenesis (8,14,15). The kinetics of hyaluronidase were determined in the past using the turbidimetric method (16). Since then, new and improved methods were generated for measurements on hyaluronidase activity, using fluorescent hyaluronic acid as a substrate (17), viscosimetry (18), ELISA-like assay using biotinylated HA binding peptides (19), a microtiter-based assay (20), the Morgan–Elson reaction (21) and its fluorimetric version (22), chromatography (23) and particle exclusion assay (24). However, none of these methods can be applied in vivo for non-invasive detection. First-order reaction kinetics were found to describe well the rate of hyaluronan degradation by hyaluronidase, as expected for degradation of a large uniform polymer (25). The temperature dependence of hyaluronidase activity varies between species with peak activity as high as 40 °C reported recently for enzyme isolated from camel ticks (26).

We have recently reported the development of a novel MRI contrast material, HA-GdDTPA-beads, for noninvasive imaging of hyaluronidase activity (27). HAGdDTPA-beads were designed to serve as substrate analogs and show alteration of relaxivity in the presence of hyaluronidase, thus acting as a ‘smart’ bioactive contrast agent (27). Contrast agents that are activated by enzymatic activity were reported for near-infrared imaging (28) and for MRI (29,30), mostly for analysis of protease activity, but also for imaging the activity of β-galactosidase (31). MR spectroscopy has been applied extensively for kinetic analysis of enzymatic reactions. Examples include the analysis of phosphate transfer reactions by 31P NMR magnetization transfer (32–34), analysis of glucose and choline metabolism by 13C NMR(35–39) and 19F NMR studies of metabolic conversion of fluorinated substrates (40,41). In vivo molecular imaging analysis of enzymatic activity using substrate-based MRI contrast agents has so far been directed predominantly to spatial delineation of regions of enzymatic activity (31).The aim of this work was to determine the ability to apply kinetic analysis for the quantitative determination of hyaluronidase kinetics in vitro and for the determination of the extent of enzymatic conversion of the contrast material in vivo.

METHODS

Synthesis

The contrast material was synthesized as described (27). Briefly, hyaluronan (50 mg human umbilical cord HA; Sigma Chemical, St. Louis, MO) was dissolved in 2-(N-morpholino)ethanesulfonic acid (MES, 0.1 M, 50 mL, pH 4.75; Sigma). Activation of the carboxyl groups with N-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)-N-ethylcarbodiimide hydro-chloride (EDC, 2.4 mg) was followed by overnight stirring with ethylenediamine (EDA, 2 mg at room temperature). The product was dialyzed against doubly distilled water (DDW) and reacted with diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid dianhydride (cDTPAA, 18.7 mg; Sigma) dissolved in filtered dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO, 55 mL) overnight at room temperature. After a second dialysis, gadolinium(III) chloride (GdCl3, 23.5 mg in DDW; Sigma) was added and stirred for 24 h followed by a third dialysis.. HA-GdDTPA was further bound to avidin–agarose beads (bead size 0.040–0.165 mm; Sigma). Avidin-linked agarose beads (50 μL bead suspension containing approximately 6 × 10 –9 molavidin; Sigma) were mixed with 5-(biotinamido)penty-lamine (BP, 2 μg; Pierce Biotechnology, Rockford, IL, USA) in MES buffer (pH 5.5, 0.1 M) at room temperature in order to allow the biotin in the BP link to the avidin on the agarose beads. The carboxyl groups of HA (25 mg HA-GdDTPA) were activated in MES buffer by EDC (2 mg) and added to the BP-conjugated beads, stirred at room temperature overnight and purified by dialysis against DDW. The gadolinium content of the product was measured by inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS), showing approximately 0.8% Gd bound on the beads.

Cell culture

Human epithelial ovarian carcinoma ES-2 cells (kindly provided by Professor Steffen Hauptmann, Institute of Pathology, Rudolf-Virchow-Haus, Berlin, Germany) were cultured in Dulbecco's minimal essential medium (DMEM), supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS), 100 u/mL penicillin, 0.1 mg/mL streptomycin, 0.06 mg/mL amphotericin and 0.292 mg/mL L-glutamine.

Ovarian carcinoma tumor xenografts

All animal experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. CD-1 female nude mice, 12 weeks old (n = 6), were inoculated with 3 × 106 ES-2 cells. MRI studies were performed 3 weeks after inoculation. The mice were anesthetized with intraperitoneal ketamine (75 mg/kg; Ketaset, Fort Dodge Laboratories, Fort Dodge, IA, USA) and xylazine (XYLM, 3 mg/kg; VMD, Arendonk, Belgium). A vein flow (24GA, BD Neoflon, Becton Dickinson, Helsingborg Sweden) was inserted subcutaneously for local administration of HA-GdDTPA beads (5 mg/mL).

In vitro MRI kinetic studies of the activation of HA-GdDTPA-beads by hyal

HA-GdDTPA-beads (270 μL 5 mg/mL) were inserted in the NMR tube and were equilibrated in the NMR spectrometer to a selected temperature (the temperature was stabilized and measured both by the NMR temperature control unit and by an external thermo-couple). Hyal (Sigma, Type IV-S from bovine testes, 0.3 mg/mL; 30 μL 10 U) was injected into the NMR tube via a catheter and R2 was measured from the time of injection every 2.40 min for about 15 min. MRI measurements were performed on a 400 MHz (9.4 T) wide-bore Bruker DMX spectrometer, equipped with a microimaging attachment with a 5 mm Helmholtz radiofrequency coil or on a horizontal 4.7 T Biospec (Bruker, Karlsruhe, Germany). For R2 measurements, a multi-echo spin-echo sequence was used to acquire eight consecutive echoes with an inter-echo spacing of 10 ms (TE = 10, 20, 30, 40 50, 60, 70 and 80 ms; TR = 2000 ms; 2 averages, field of view 1 × 1 cm, slice thickness 1 mm, matrix 128 × 128, spectral width 50 000 Hz).

In vivo MRI kinetic studies of HA-GdDTPA-beads activation by hyal

MRI experiments were performed on a horizontal Bruker Biospec 4.7 T spectrometer (Bruker BioSpin, Ettlingen, Germany), using an actively radiofrequency decoupled 1.5 cm surface coil, embedded in a Perspex board and a birdcage transmission coil. Anesthetized mice were placed supine with the graft located above the center of the surface coil. The mice were immobilized using adhesive tape and covered with a paper blanket in order to reduce temperature drop during the measurement. Multi-echo spin-echo images were acquired with TR = 500 ms, TE = 10–80 ms, slice thickness 1 mm and field of view 3.5 × 3.5 cm.

Analysis of the MR data

MRI data was analyzed on a personal computer using Matlab (Math Works, Natick, MA, USA). Images acquired with eight different TE values were used for generation of R2 maps by non-linear least-squares pixel-by-pixel fitting to a single exponent:

| (1) |

where I is the measured signal intensity for each TE and A is the fitted steady-state signal intensity in fully relaxed images.

RESULTS

Derivation of contrast material degradation by hyaluronidase from changes in R2 relaxation

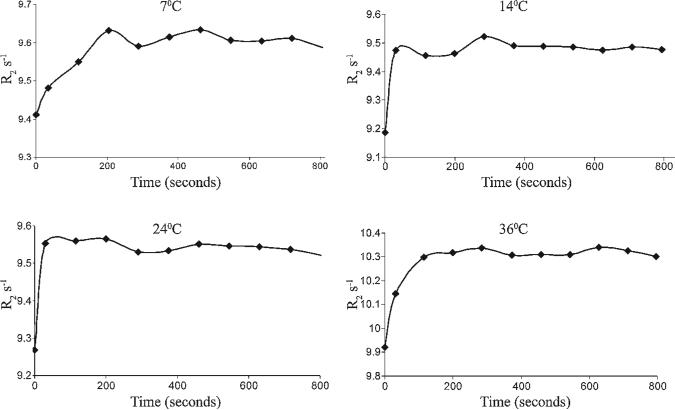

Multi-echo spin echo was applied for analysis of the R2 relaxation rate of water. Addition of hyal to a suspension of HA-GdDTPA-beads resulted in a time-dependent increase in R2 (Fig. 1) The changes in R2 after addition of hyal occur owing to the conversion of the contrast material HA-GdDTPA-beads with low relaxivity (r2B; relaxivity of HA-GdDTPA-beads per Gd) to the high relaxivity degraded HA-GdDTPA fragments (r2D; relaxivity of degraded contrast material per Gd).

Figure 1.

Temperature-dependent dynamics of hyaluronidase-mediated activation of HA-GdDTPA-beads. Bovine testes hyaluronidase was injected into NMR tubes that contained HA-GdDTPA-beads. Temporal changes in R2 were determined from consecutive multi-echo images. Hyaluronidase activity was manifested by elevation in R2. Activation of the contrast material was measured at four temperatures (7, 14, 24 and 36 °C).

The following assumptions were made in order to derive the concentration of GdDTPA in HA-GdDTPA-beads ([GdB,t]) and GdDTPA in the degradation product ([GdD,t]) at each time point.

At the time of addition of hyaluronidase (t = 0), the concentration of GdDTPA in HA-GdDTPA-beads should be equal to the concentration of GdDTPA in a fully degraded product ([GdB,0] = [GdD,SS], where [GdB,0] is the concentration of Gd in HA-GdDTPA-beads at time 0 and [GdD,SS] is the concentration of Gd in degraded fragments at steady state).

Similarly, at each time point the total content of GdDTPA is maintained:

| (2) |

The temporal changes in relaxation of water (ΔR2,t = R2,t – R2,w where R2,w is the relaxation of water in the absence of HA-GdDTPA-beads) are thus given by

| (3) |

Thus at time zero ΔR2,0 = r2B[GdB,0], while upon complete degradation of HA-GdDTPA-beads by hyaluronidase ΔR2,SS = r2D[GdD,SS].

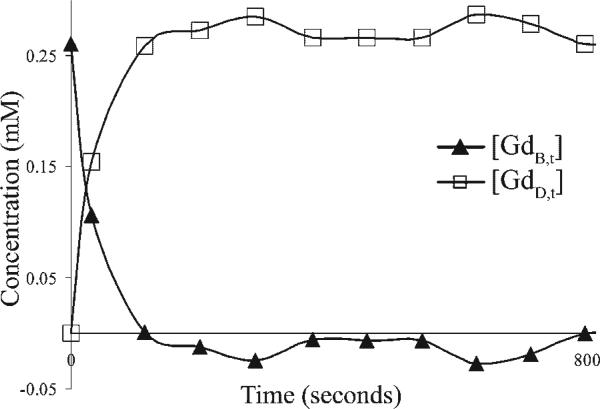

By using experimentally derived values for [GdB,0] = 0.26 mM , R2,w = 1.73s–1mM–1 and r2D = 30s–1,–1 at room temperature (Table 1), it was possible to generate curves of the hyaluronidase-mediated decrease in [GdB,t] and accumulation of [GdD,t] (Fig. 2).

Table 1.

MRI analysis of the temperature dependence of hyaluronidase activity

| Temperature (°C) | r2B (s–1 mm–1)a | r2D (s–1 mm–1)b | K (min–1)c | UMRI (μmol/min)d |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7 | 29.53 | 30.26 | 0.012 | 0.18 |

| 14 | 28.65 | 29.81 | 0.130 | 1.99 |

| 24 | 29.00 | 30.00 | 0.400 | 6.11 |

| 36 | 31.50 | 32.96 | 0.029 | 0.44 |

Relaxivity of GdDTPA in HA-GdDTPA-beads.

Relaxivity of GdDTPA in HA-GdDTPA fragments.

Rate of hyaluronidase-mediated degradation of HA-GdDTPA-beads as determined by MRI.

Units of hyaluronidase activity as determined by MRI.

Figure 2.

Quantitative MRI-based dynamic analysis of enzymatic conversion of HA-GdDTPA-beads. Bovine testes hyaluronidase was injected into NMR tubes that contained HAGdDTPA-beads at 36 °C (as shown in Fig. 1). The concentrations of GdDTPA in intact contrast material, [GdB,t], and in HA-GdDTPA fragments, [GdD,t], were calculated using the difference in specific relaxivity of the two forms assuming complete degradation of the contrast material at steady state.

Dynamic analysis of hyaluronidase-mediated activation of the contrast material

Hyaluronidase-mediated degradation of hyaluronan is a first-order reaction (25). Accordingly, the temporal decrease of GdDTPA in HA-GdDTPA-beads ([GdB,t] was analyzed by fitting to a single exponential decay:

| (4) |

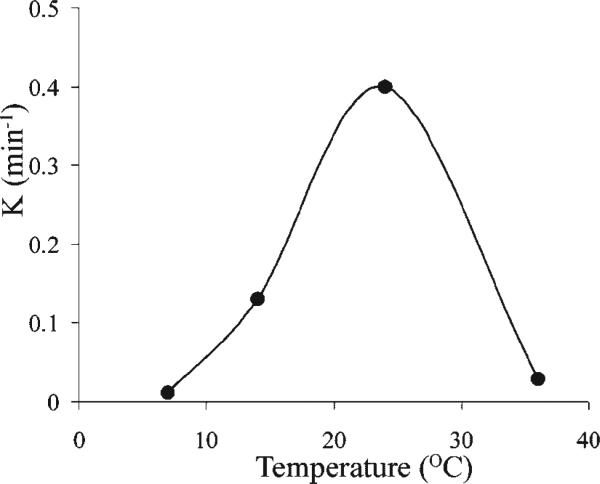

where k is the rate of dissociation of HA-GdDTPA from the beads. As expected, k showed a typical bell-shaped temperature dependence between 7 and 36 °C with peak activity at 25 °C (Fig. 3, Table 1).

Figure 3.

MRI analysis of the temperature dependence of hyaluronidase activity. Hyaluronidase was injected via a catheter into NMR tubes that contained HA-GdDTPA-beads. At each temperature the rate of enzymatic activity [k (min –1)] was calculated from the kinetics of degradation of HA-GdDTPA-beads (as shown in Fig. 2). The bell-shaped temperature dependence showed maximum enzymatic activity at 25 °C.

To calculate approximate enzymatic activity units (UMRI in μmol/min), we need to account for the fact that MRI detects only hyaluronidase-mediated cleavage that releases GdDTPA and thus under-determines enzymatic degradation at a probability that can be estimated by the ratio of GdDTPA to disaccharides (RH/G):

| (5) |

The units of enzyme activity estimated by MRI using HA-GdDTPA-beads for bovine testes hyaluronidase (Sigma; ca 10 units) for RH/G 14:1 between HA disaccharides and Gd, where the Gd content relative to hyaluronan was determined by ICP-MS to be 7.7%, while the content of disaccharides (D) was 1.09 μmol. The experimental UMRI was 6.11 μmol/min at 24 °C, very close, within an order of magnitude, to the activity stated of 10 units μmol/min at 25 °C.

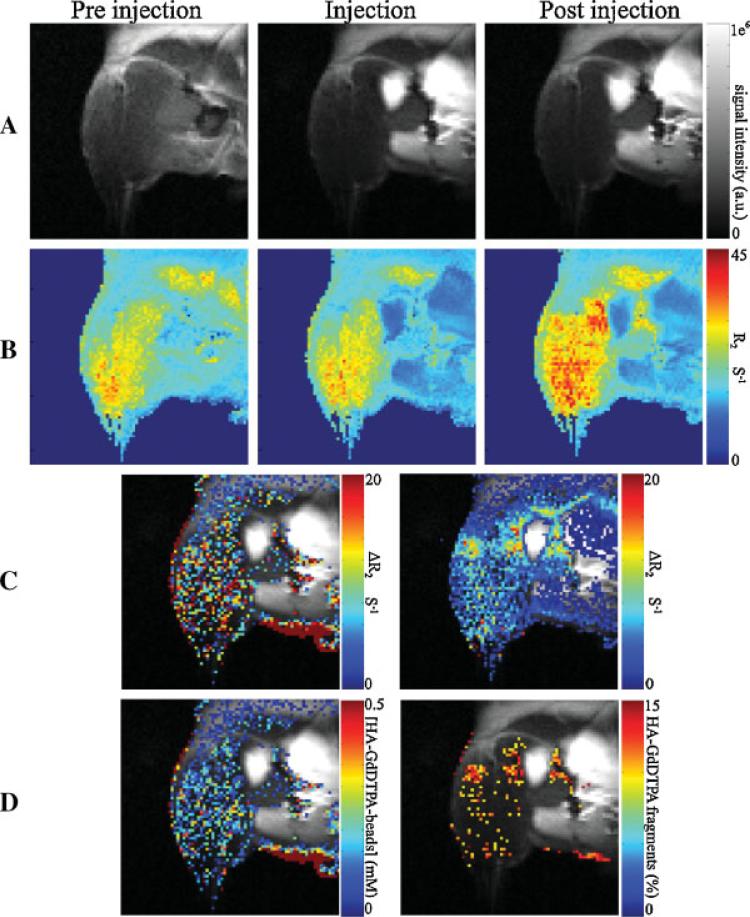

In vivoanalysis of hyaluronidase-mediated degradation of HA-GdDTPA-beads

The distribution of HA-GdDTPA-beads immediately after interstitial administration was determined from the change in R2:

| (6) |

where R2,0 and R2pre are the relaxation rates measured immediately after and before administration of the contrast material respectively and r2B is the relaxivity of intact HA-GdDTPA-beads as determined in vitro (r2B = 31.5 s–1 mM–1, 36 °C; Table 1).

Dynamic analysis of the changes in relaxation showed complete enzymatic activation by the second scan at t = 2.4 min. Using the value for relaxivity for HA-GdDTPA fragments as derived in vitro (r2D = 32.96 s–1mM–1, 36 °C; Table 1) allowed us to determine the fraction of contrast material activated by hyaluronidase (FD = [GdD]/[GdB,0];Figure 4):

| (7) |

This fraction was elevated in the vicinity of ovarian cancer tumors.

Figure 4.

In vivo quantitative assessment of hyaluronidase activity in ovarian carcinoma tumors. HA-GdDTPA-beads were administered via a catheter to the hind limb in the vicinity of the ES-2 tumor and R2 measurements were taken at different time points. (A) MRI images of the tumor area in different times: left, before contrast material injection; middle, time of interstitial administration of the HA-GdDTPA-beads; right, 2.4 min after injection. All the images were acquired under identical experimental conditions. (B) Corresponding R2 maps. (C) Calculated differences in R2 overlaid on the grays-scale images: left, difference between the relaxation rate at the time of interstitial administration of the HA-GdDTPA-beads and the relaxation rate before CM administration [ΔR = R (t = 2.4 min) – R (t = 0)]. The tumor can easily be seen as a bright spot in the center of the contrast enhancement area. (D)Left, contrast material concentration map overlaid on the gray-scale image; right, the percentage of activated contrast material. Most of the activation of the contrast material occurred at the rim of the tumor.

DISCUSSION

HA-GdDTPA-beads, a novel ‘smart’ contrast material, functioning as a substrate analog, was applied for quantitative analysis of the activity of hyaluronidase. Attachment of HA-GdDTPA to beads resulted in partial masking of Gd from the surrounding water. Degradation of HA by hyaluronidase exposed Gd to water, leading to increased relaxivity, despite the drop in molecular weight and molecular tumbling time.

We further evaluated the ability to use the dynamics of enzymatic activation of this contrast material for quantitative measurement of the kinetics of hyaluronidase activity. The activity units measured by MRI for bovine testes hyaluronidase were consistent with the cited data for this enzyme. As expected activity showed high sensitivity to temperature with maximum activity at 24 °C. A similar bell-shaped temperature dependence was previously reported for hyaluronidases of other sources, with peak activity varying with the source of the enzyme, the substrate and preparation (26).

Clearly, the major attraction of MRI-based molecular imaging lies in application for in vivo use. The kinetics of enzymatic activation of the contrast material were faster than the temporal resolution of the consecutive images that were acquired in vivo. However, using the known relaxation rates it was possible to derive the fraction of contrast material that was activated by the enzyme. The regions of activated contrast material were, as expected, in the tumor periphery.

It is important to note that the activity measured by MRI analysis of relaxation rate changes induced by hyaluronidase will be underestimated in the presence of competing endogenous tissue HA. Furthermore, the current formulation precludes intravenous systemic administration and destabilization of DTPA along with secondary chelation of Gd by carboxylic groups on HA may reduce the changes in relaxation rates upon hyaluronidase degradation. Improvements in carrier and chelator structure will be necessary for advancing the utilization of hyaluronidase as a target for molecular imaging by MRI.

Hyaluronidase is an important participant in cancer development, as manifested in ovarian and colon cancer. Specifically, hyaluronidase activity was implicated in modulating the angiogenic capacity of the tumor microenvironment (10) and in addition this enzyme was demonstrated to play an important role in regulating the tumor interstitial pressure and thus drug delivery (42,43). Alteration of hyaluronidase activity in tumors has therapeutic potential and thus non-invasive imaging of hyaluronidase activity may be important in the detection and monitoring of tumor progression and therapy.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by research grants from the US National Cancer Institute (RO1 CA75334), by the Israel Science Foundation and by the Mark Family Foundation.

Acknowledgments

Contract/grant sponsor: US National Cancer Institute; contract/grant number: RO1 CA75334.

Contract/grant sponsor: Israel Science Foundation.

Contract/grant sponsor: Mark Family Foundation.

REFERENCES

- 1.Schiffenbauer YS, Meir G, Maoz M, Even-Ram SC, Bar-Shavit R, Neeman M. Gonadotropin stimulation of MLS human epithelial ovarian carcinoma cells augments cell adhesion mediated by CD44 and by alpha(v)-integrin. Gynecol. Oncol. 2002;84:296–302. doi: 10.1006/gyno.2001.6512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cohen M, Joester D, Geiger B, Addadi L. Spatial and temporal sequence of events in cell adhesion: from molecular recognition to focal adhesion assembly. ChemBiochem. 2004;5:1393–1399. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200400162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zimmerman E, Geiger B, Addadi L. Initial stages of cell-matrix adhesion can be mediated and modulated by cell-surface hyaluronan. Biophys J. 2002;82:1848–1857. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(02)75535-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tempel C, Gilead A, Neeman M. Hyaluronic acid as an anti-angiogenic shield in the preovulatory rat follicle. Biol. Reprod. 2000;63:134–140. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod63.1.134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.West DC, Hampson IN, Arnold F, Kumar S. Angiogenesis induced by degradation products of hyaluronic acid. Science. 1985;228:1324–1326. doi: 10.1126/science.2408340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kreil G. Hyaluronidases – a group of neglected enzymes. Protein Sci. 1995;4:1666–1669. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560040902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Csoka TB, Frost GI, Stern R. Hyaluronidases in tissue invasion. Invasion Metastasis. 1997;17:297–311. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Csoka AB, Frost GI, Stern R. The six hyaluronidase-like genes in the human and mouse genomes. Matrix Biol. 2001;20:499–508. doi: 10.1016/s0945-053x(01)00172-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Afify AM, Stern M, Guntenhoner M, Stern R. Purification and characterization of human serum hyaluronidase. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1993;305:434–441. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1993.1443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Paiva P, Van Damme MP, Tellbach M, Jones RL, Jobling T, Salamonsen LA. Expression patterns of hyaluronan, hyaluronan synthases and hyaluronidases indicate a role for hyaluronan in the progression of endometrial cancer. Gynecol. Oncol. 2005;98:193–202. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2005.02.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Udabage L, Brownlee GR, Nilsson SK, Brown TJ. The over-expression of HAS2, Hyal-2 and CD44 is implicated in the invasiveness of breast cancer. Exp. Cell Res. 2005;310:205–217. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2005.07.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chang NS. Transforming growth factor-beta1 blocks the enhancement of tumor necrosis factor cytotoxicity by hyaluronidase Hyal-2 in L929 fibroblasts. BMC Cell Biol. 2002;3:8. doi: 10.1186/1471-2121-3-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lin G, Stern R. Plasma hyaluronidase (Hyal-1) promotes tumor cell cycling. Cancer Lett. 2001;163:95–101. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3835(00)00669-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stern R. Hyaluronan metabolism: a major paradox in cancer biology. Pathol. Biol. (Paris) 2005;53:372–382. doi: 10.1016/j.patbio.2004.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tamakoshi K, Kikkawa F, Maeda O, Suganuma N, Yamagata S, Yamagata T, Tomoda Y. Hyaluronidase activity in gynaecological cancer tissues with different metastatic forms. Br. J. Cancer. 1997;75:1807–1811. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1997.308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Faber V. Streptococcal hyaluronidase; review and the turbidimetric method for its determination. Acta Pathol. Microbiol. Scand. 1952;31:345–354. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nagata H, Kojima R, Sakurai K, Sakai S, Kodera Y, Nishimura H, Inada Y, Matsushima A. Molecular-weight-based hyaluronidase assay using fluorescent hyaluronic acid as a substrate. Anal. Biochem. 2004;330:356–358. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2004.03.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vercruysse KP, Lauwers AR, Demeester JM. Absolute and empirical determination of the enzymatic activity and kinetic investigation of the action of hyaluronidase on hyaluronan using viscosimetry. Biochem. J. 1995;306(Pt 1):153–160. doi: 10.1042/bj3060153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stern M, Stern R. An ELISA-like assay for hyaluronidase and hyaluronidase inhibitors. Matrix. 1992;12:397–403. doi: 10.1016/s0934-8832(11)80036-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Frost GI, Stern R. A microtiter-based assay for hyaluronidase activity not requiring specialized reagents. Anal. Biochem. 1997;251:263–269. doi: 10.1006/abio.1997.2262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vercruysse KP, Lauwers AR, Demeester JM. Kinetic investigation of the action of hyaluronidase on hyaluronan using the Morgan–Elson and neocuproine assays. Biochem. J. 1995;310(Pt 1):55–59. doi: 10.1042/bj3100055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Takahashi T, Ikegami-Kawai M, Okuda R, Suzuki K. A fluori-metric Morgan–Elson assay method for hyaluronidase activity. Anal. Biochem. 2003;322:257–263. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2003.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cramer JA, Bailey LC. A reversed-phase ion-pair high-performance liquid chromatography method for bovine testicular hyaluronidase digests using postcolumn derivatization with 2-cyanoacetamide and ultraviolet detection. Anal. Biochem. 1991;196:183–191. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(91)90137-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Evanko SP, Angello JC, Wight TN. Formation of hyaluronan- and versican-rich pericellular matrix is required for proliferation and migration of vascular smooth muscle cells. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 1999;19:1004–1013. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.19.4.1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bachtold JG, Gebhardt LP. The determination of hyaluronidase activity as derived from its reaction kinetics. J. Biol. Chem. 1952;19:635–639. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mohamed SA. Hyaluronidase isoforms from developing embryos of the camel tick Hyalomma dromedarii. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. B Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2005;142:164–171. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpc.2005.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shiftan L, Israely T, Cohen M, Frydman V, Dafni H, Stern R, Neeman M. Magnetic resonance imaging visualization of hyaluronidase in ovarian carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2005;65:10316–10323. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mahmood U, Tung CH, Bogdanov A, Jr, Weissleder R. Near-infrared optical imaging of protease activity for tumor detection. Radiology. 1999;213:866–870. doi: 10.1148/radiology.213.3.r99dc14866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Perez JM, Josephson L, O'Loughlin T, Hogemann D, Weissleder R. Magnetic relaxation switches capable of sensing molecular interactions. Nat. Biotechnol. 2002;20:816–820. doi: 10.1038/nbt720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhao M, Josephson L, Tang Y, Weissleder R. Magnetic sensors for protease assays. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2003;42:1375–1378. doi: 10.1002/anie.200390352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Louie AY, Huber MM, Ahrens ET, Rothbacher U, Moats R, Jacobs RE, Fraser SE, Meade TJ. In vivo visualization of gene expression using magnetic resonance imaging. Nat. Biotechnol. 2000;18:321–325. doi: 10.1038/73780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Koretsky AP, Wang S, Klein MP, James TL, Weiner MW. 31P NMR saturation transfer measurements of phosphorus exchange reactions in rat heart and kidney in situ. Biochemistry. 1986;25:77–84. doi: 10.1021/bi00349a012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Koretsky AP, Basus VJ, James TL, Klein MP, Weiner MW. Detection of exchange reactions involving small metabolite pools using NMR magnetization transfer techniques: relevance to sub-cellular compartmentation of creatine kinase. Magn. Reson. Med. 1985;2:586–594. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910020610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Neeman M, Rushkin E, Kaye AM, Degani H. 31P-NMR studies of phosphate transfer rates in T47D human breast cancer cells. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1987;930:179–192. doi: 10.1016/0167-4889(87)90030-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Neeman M, Degani H. Metabolic studies of estrogen- and tamoxifen-treated human breast cancer cells by nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Cancer Res. 1989;49:589–594. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Neeman M, Degani H. Early estrogen-induced metabolic changes and their inhibition by actinomycin D and cycloheximide in human breast cancer cells: 31P and 13C NMR studies. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1989;86:5585–5589. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.14.5585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ronen SM, Degani H. The application of 13C NMR to the characterization of phospholipid metabolism in cells. Magn. Reson. Med. 1992;25:384–389. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910250219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ronen SM, Rushkin E, Degani H. Lipid metabolism in large T47D human breast cancer spheroids: 31P- and 13C-NMR studies of choline and ethanolamine uptake. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1992;1138:203–212. doi: 10.1016/0925-4439(92)90039-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ronen SM, Rushkin E, Degani H. Lipid metabolism in T47D human breast cancer cells: 31P and 13C-NMR studies of choline and ethanolamine uptake. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1991;1095:5–16. doi: 10.1016/0167-4889(91)90038-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vialaneix JP, Chouini N, Malet-Martino MC, Martino R, Michel G, Lepargneur JP. Noninvasive and quantitative 19F nuclear magnetic resonance study of flucytosine metabolism in Candida strains. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1986;30:756–762. doi: 10.1128/aac.30.5.756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sijens PE, Huang YM, Baldwin NJ, Ng TC. 19F magnetic resonance spectroscopy studies of the metabolism of 5-fluorouracil in murine RIF-1 tumors and liver. Cancer Res. 1991;51:1384–1390. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Eikenes L, Tari M, Tufto I, Bruland OS, de Lange Davies C. Hyaluronidase induces a transcapillary pressure gradient and improves the distribution and uptake of liposomal doxorubicin (Caelyx) in human osteosarcoma xenografts. Br. J. Cancer. 2005;93:81–88. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Brekken C, de Lange Davies C. Hyaluronidase reduces the inter-stitial fluid pressure in solid tumours in a non-linear concentration-dependent manner. Cancer Lett. 1998;131:65–70. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3835(98)00202-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]