Abstract

Children who become overweight by age 2 years have significantly greater risks of long-term health problems, and children in low-income communities, where rates of low adult literacy are highest, are at increased risk of developing obesity. The objective of the Greenlight Intervention Study is to assess the effectiveness of a low-literacy, primary-care intervention on the reduction of early childhood obesity. At 4 primary-care pediatric residency training sites across the US, 865 infant-parent dyads were enrolled at the 2-month well-child checkup and are being followed through the 24-month well-child checkup. Two sites were randomly assigned to the intervention, and the other sites were assigned to an attention-control arm, implementing the American Academy of Pediatrics' The Injury Prevention Program. The intervention consists of an interactive educational toolkit, including low-literacy materials designed for use during well-child visits, and a clinician-centered curriculum for providing low-literacy guidance on obesity prevention. The study is powered to detect a 10% difference in the number of children overweight (BMI > 85%) at 24 months. Other outcome measures include observed physician–parent communication, as well as parent-reported information on child dietary intake, physical activity, and injury-prevention behaviors. The study is designed to inform evidence-based standards for early childhood obesity prevention, and more generally to inform optimal approaches for low-literacy messages and health literacy training in primary preventive care. This article describes the conceptual model, study design, intervention content, and baseline characteristics of the study population.

Keywords: health literacy, obesity prevention, injury prevention, early childhood, primary care, resident education

Obesity prevention is a national public health priority, and early childhood may be a critical period for preventing obesity-related morbidity across the entire life course. More than 1 in 4 preschool children are overweight or obese,1 and these rates are disproportionately higher among children in low income and ethnic-minority communities.2–4 Increased weight gain during infancy has been associated with increased obesity risk during early childhood.5 Children who are overweight during early childhood are at least 5 times more likely than nonobese children to become overweight or obese adolescents.5–9 Overweight adolescents, in turn, are at increased risk for adult obesity and adult-onset, obesity-related illnesses10,11 such as hypertension, type-2 diabetes,12 steatohepatitis,13 and orthopedic problems.14 Addressing obesity during early childhood, however, requires a family-centered approach that engages children’s adult caregivers, especially their parents.15

The US Surgeon General has identified health literacy as “one of the largest contributors to our nation’s epidemic of overweight and obesity.”16,17 At least 1 in 4 parents has basic or below-basic health literacy skills.18 Low literacy and numeracy skills have been independently associated with poor understanding of health information, poor health behaviors, and poor clinical outcomes.19–33 In the context of child growth and nutrition, low parent health literacy is associated with worse knowledge of breastfeeding, problems mixing infant formula correctly, difficulty understanding food labels and portion sizes, difficulty understanding standard growth charts, and higher BMI in children.29,34–40

Although clinical efforts to prevent childhood obesity have had a limited effect on school-aged children,7,41–43 few clinical trials have specifically addressed obesity prevention during the first years of life, and none has examined the effect of an intervention that integrates a literacy-sensitive approach.6 In this report, we describe the Greenlight Intervention Study, a cluster randomized, multisite trial to assess the efficacy of a low literacy, primary care-based intervention to prevent early childhood obesity. Specifically, we describe its conceptual model, study design, intervention components, research methodology, and baseline data.

Study Design

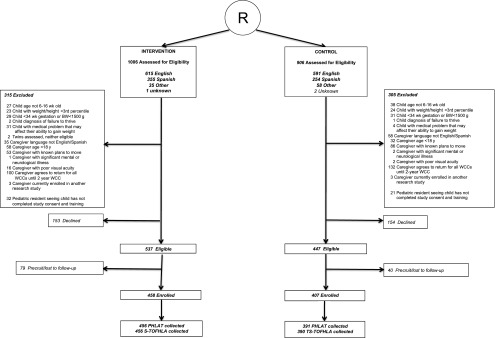

We implemented a cluster randomized controlled trial design to explore 3 primary aims: (1) to assess the impact of the intervention on reducing the prevalence of overweight at age 2 years; (2) to assess the impact of the intervention on the parent health behaviors most likely to prevent child overweight; and (3) to examine the role of parent health literacy as a moderator of both effects. To avoid intrasite contamination, randomization occurred at the site level, stratified by population density, such that the 2 sites serving the higher population-density communities were assigned to different groups. A statistician, blinded to site location, conducted the sites’ random assignment to intervention or active-control status, using a random number generator in Stata 9.0 (College Park, TX). Two sites (New York University and Vanderbilt University) were randomized to the intervention, which applied health literacy principles and focused on obesity prevention, and 2 sites (University of Miami and University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill) to the active-control arm, which did not apply health literacy principles and focused on injury prevention.

At both intervention and control sites, we enrolled caregiver–infant dyads at each child’s 2-month well-child checkup (WCC), with intervention and assessment at each of 5- to 6-interval visits at 4-, 6-, 9-, 12-, and 15- and/or 18-month WCCs, through the study’s completion at the child’s 24-month WCC. The study was approved by the institutional review boards at each of the 4 participating university medical centers, and a data safety monitoring board, including participants from each institution, monitored study progress. The study was registered with the national Clinical Trials Registry (NCT01040897 at clinicaltrials.gov).

Setting

Study principal investigators (PIs) implemented the intervention or active-control at academic-medical-center-based pediatric primary care clinics, where pediatric trainees (residents) provide the majority of pediatric preventive care. PIs chose this setting for several reasons: (1) pediatric resident practice sites provide care for more than one-fifth of the socioeconomically disadvantaged families in the United States,44 who are at highest risk for childhood obesity; (2) resident physicians have been shown to be more sensitive to clinical behavior change than community-based physicians45,46; (3) a majority of pediatric residents become practicing community-based physicians47,48; and (4) academic practice-based research networks, particularly the Continuity Clinic Research Network, provide the potential for rapid dissemination and quality improvement.49 Although we considered alternative intervention settings (eg, primary-care private practices, community health centers; family-medicine practices), none offered more optimal combinations of these attributes. The model was constructed to be easily translatable, however, for implementation in community-based practices. Participating sites were located in diverse areas of the eastern United States, with 2 sites (New York University/Bellevue Hospital and University of Miami/Jackson Memorial Hospital) serving higher population-density communities, and 2 sites (Vanderbilt and University of North Carolina) serving less dense communities.

Study enrollment began in April 2010. All subjects are scheduled to complete their enrollment in the Greenlight Intervention Study by December 2014. All subjects are given the option to enroll in the Greenlight Cohort Study, which will follow parent behaviors, child BMI, and other participant characteristics through age 5 years (2017).

Eligibility

To be eligible for participation, each caregiver–infant dyad satisfied the following inclusion criteria: child presenting for a 2-month WCC with an intervention-trained resident physician between 6 weeks and 16 weeks of age; caregiver’s ability to speak Spanish or English; and no plans to leave the clinic within the upcoming 2 years. Infant exclusion criteria included the following: born before 34 weeks’ gestational age or birth weight <1500 g; weight < third percentile at enrollment (using the World Health Organization growth curves)50; or any chronic medical problem that may affect weight gain patterns (eg, metabolic disease, uncorrected congenital heart disease, renal disease, high-calorie formula; cleft palate; Down syndrome). Caregiver exclusion criteria included the following: <18 years old; serious mental or neurologic illness likely to impair ability to consent or participate; or poor visual acuity (ie, corrected vision worse than 20/50 with Rosenbaum Pocket Screener as assessed at the time of recruitment). Eligible physicians included any pediatric resident who provided preventive care for children in one of the study clinics.

At all sites, most children were insured by Medicaid or other public insurance, and most parents self-identified as having ethnic-minority backgrounds. Nearly all participating primary caregivers (>90%) were mothers (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Baseline Characteristics of Children and Caregivers (N = 865)

| Characteristics | Mean (SD) or n (%) | Intervention, N = 459 | Control, N = 406 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Child | |||

| Child age at enrollment, wk | 9.3 (1.8) | 9.1 (1.6)a | 9.5 (1.9)a |

| Child gender, girl | 444 (51) | 245 (53) | 199 (49) |

| Child health insurance coverage | |||

| Medicaid/CHIP/Public | 734 (84) | 412 (90)a | 322 (80)a |

| None | 27 (3) | 11 (2) | 16 (4) |

| Private/Commercial | 97 (11) | 33 (7) | 64 (16) |

| Child birth weight, kg | 3.29 (0.52) | 3.34 (0.48)a | 3.23 (0.56)a |

| Child weight at enrollment, kg | 5.36 (0.75) | 5.39 (0.77) | 5.32 (0.80) |

| Child weight z score at enrollment | 0.31 (1.13) | 0.23 (1.12) | 0.41 (1.14) |

| Parent | |||

| Parent age, y | 27.6 (6.1) | 27.1 (5.7)a | 28.3 (6.4)a |

| Relationship to child | |||

| Mother | 826 (95) | 447 (97)a | 379 (93)a |

| Father | 37 (4) | 10 (2)a | 27 (7)a |

| Grandmother | 2 (1) | 2 (1) | 0 (0) |

| Parent Non-US born | 438 (51) | 254 (56)a | 184 (46)a |

| Parent race/ethnicity | |||

| Hispanic | 431 (50) | 258 (56)a | 173 (43)a |

| White, non-Hispanic | 153 (18) | 85 (19) | 68 (17) |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 253 (27) | 96 (21)a | 139 (34)a |

| Other, non-Hispanic | 44 (5) | 20 (4) | 24 (6) |

| Parent’s primary language, Spanish | 301 (35) | 177 | 124 |

| Parent education, less than high school graduate | 224 (26) | 132 | 92 |

| Parent health literacy, PHLAT score | 58 (27) | 57 (26)a | 60 (27)a |

| Parent health literacy, S-TOFHLA score | 31.3 (7.9) | 31.4 (7.4) | 31.3 (8.4) |

| Parent health literacyb | |||

| Low literacy (inadequate or marginal) | 94 (11) | 50 (11) | 44 (11) |

| Household | |||

| Income (annual)c | |||

| <$10 000 | 264 (31) | 146 (32) | 118 (30) |

| $10 000–$19 999 | 227 (26.2) | 133 (29)a | 95 (24)a |

| $20 000–$39 999 | 202 (23.3) | 118 (26)a | 84 (21)a |

| ≥$40 000 | 132 (15.3) | 56 (12)a | 76 (19)a |

| Do not know | 26 (3.0) | 3 (1)a | 23 (6)a |

| No. of adults in home, >1d | 782 (90.0) | 420 (91)a | 358 (88)a |

| No. of children in home, >1d | 524 (60) | 413 (60) | 354 (60) |

CHIP, Children’s Health Insurance Program; PHLAT, Parent Health Literacy Assessment Test.

Statistically significant difference between intervention and control group (P < .05 by Wilcoxon or Pearson test).

Score of <23 on the Short Test of Functional Health Literacy for Adults (STOFHLA).

TABLE 1.

Core and Secondary Counseling Topics for Greenlight Toolkit

| Topic (Behavioral Message) | Age, mo | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 4 | 6 | 9 | 12 | 15 | 18 | |

| Recognize satiety cues | X | X | — | — | — | — | — |

| Avoid sweet drinks | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Delay introduction of solids | * | X | — | — | — | — | — |

| Choose appropriate solid foods and portion sizes | — | — | X | X | X | X | X |

| Be active with your infant/avoid screen time | X | * | X | X | X | X | X |

| Breastfeed | * | * | * | * | — | — | — |

X denotes 1 of 3 core counseling topics featured on the cover of each age-specific toolkit booklet. Core counseling topics are based on developmental-stage appropriateness, complementary messages at previous and subsequent visits, and the best available evidence (as of December 2009) associating the behavior with reduced child obesity risk. Asterisks denote secondary topics, which are reinforced on inside pages and in supplementary booklets.

—, indicate topics that are not addressed in the age-specific booklet.

Intervention

Based on social cognitive theory (SCT) and health-literacy principles, the Greenlight Intervention targets adult caregivers with behavior-change components administered by pediatric residents at each well-child visit from 2 months to 24 months. The intervention design team included clinicians, scholars, and other professionals from the fields of pediatrics, health literacy and numeracy, health communication, child development and behavioral health, pediatric obesity, injury prevention, linguistic and cultural competence, graphic design, and multisite implementation. The Greenlight Intervention consists of 2 main components: (1) a low-literacy toolkit for parents, including developmentally tailored, tangible tools reinforcing recommended behaviors at each well-child visit; and (2) a health-communication curriculum for child-health providers, including modules on teach-back shared goal-setting techniques.

Conceptual Model

SCT and health-literacy principles informed the conceptual framework for the Greenlight Intervention Study (Fig 1).20,51–55 SCT suggests that a parent (or other adult caregivers) is more likely to adopt a new health behavior in an environment that includes each of 4 features: motivation (direct reinforcement of the behavior), social cues (repeated modeling of the behavior), outcome expectancy (expectation that the new behavior will produce real child benefit); and self-efficacy (confidence in her or his ability to perform the behavior). To optimize parent adoption of specific obesity-prevention behaviors, the intervention includes these 4 SCT features: (1) physicians are trained in motivational-interviewing and shared goal-setting skills to identify and reinforce specific parent behaviors (motivation); (2) at each visit, the physician provides each parent with a written toolkit and other tangible tools that offer visual models of recommended behaviors (social cues); (3) the physician provides information to help the parent make a causal link between the behavior and a healthy child (outcome expectancy); and (4) the physician uses simple messages from the toolkit to support the parent’s confidence in adopting discreet, short-term behaviors (self-efficacy).

FIGURE 1.

Conceptual model, relating parent health literacy to child health outcomes (from Sanders LM, Shaw JS, Guez G, Baur C, Rudd R. Health literacy and child health promotion: implications for research, clinical care and public policy. Pediatrics. 2009;124:S306–S314).

Literacy and Cultural Sensitivity

Applying principles and evidence from the field of health literacy,20,53–55 the design team reinforced the Greenlight intervention with additional low-literacy features, to ensure that verbal and written messages are most easily understood. PIs conducted iterative focus groups with nonparticipating parents of diverse literacy levels and cultural backgrounds. Targeting a fourth- to sixth-grade suitability level, each toolkit includes limited text density per page, subdivided text, minimal words per sentence, minimal syllables per word, large font size, and maximum white space. Text is reinforced with meaningful and actionable visual images (eg, photographs or diagrams of foods, portion sizes, or physical activities appropriate to each developmental stage). A common traffic-light motif reinforces key messages: Green sections indicating positive health behaviors to adopt; yellow sections indicating behaviors that are to be adopted only with caution; red sections indicating health behaviors to avoid. Individual-page formats were designed with the expectation that most content may be transferrable in the future to mobile-phone and tablet-accessible platforms.

Special efforts were made to include dietary and physical activity content, language, and visual images from diverse traditions and customs. All materials were translated into Spanish by an advisory committee, which was composed of 4 native Spanish-language speakers from 4 nations of origin in Latin America. The committee met iteratively to reach consensus on the most linguistically and culturally appropriate terms, examples, and images to capture the main messages.

Toolkit: Core Booklet and Tangible Tools

At each well-child visit, the physician presents the parent with a developmentally appropriate “core booklet,” and has the option to further reinforce messages with 1 of 6 topic supplements (breastfeeding, formula feeding, infant sleep, television and other screen time, family physical activity, and family nutrition). Parents are encouraged to share this booklet with all adult caregivers in the child’s home. Each core booklet is tailored to the child’s developmental stage and corresponds to 1 of the routine well-child visits between 2 months and 18 months. Each core booklet or supplement measures 8.5 by 5.5 inches (8.5 by 11-inch page, folded in half). Each core booklet contains 12 to 16 pages, and each supplement 4 to 8 pages. To promote shared goal setting at each visit, the back page of each core booklet provides blank lines to allow for tailored goal-setting, as well as a check-box list to help guide families to make specific goals (Figs 2 and 3). To access additional information on the intervention materials, visit http://www.mc.vanderbilt.edu/greenlight. Each core booklet introduces or reinforces 3 parent behaviors thought to be most strongly associated with preventing obesity during early childhood, based on developmental-stage appropriateness, complementary messages at previous and subsequent visits, and the best available evidence in the peer-review literature in December 2009 (Table 3).11,56–72 Each of these behaviors is highlighted on the cover of each core booklet within a green “traffic light” circle.

FIGURE 2.

Sample core booklet (pages 1, 4, 5, and 12 from 12-month booklet).

FIGURE 3.

Sample supplementary booklet (pages 1 and 4 from “Active Time” Supplement, for all ages).

TABLE 3.

Baseline Characteristics of Pediatric Providers (N = 516)

| Total Mean (SD) or n (%) | Intervention, N = 280 | Control, N = 236 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at enrollment, y | 27.7 (2.4) | 27.3 (2.1)a | 28.5 (2.7)a |

| Gender, women | 390 (76) | 213 (76) | 177 (75) |

| Parent status, with children | 58 (11) | 31 (11) | 27 (11) |

| Spanish-language fluency | 91 (18) | 24 (9)a | 67 (28)a |

| Training year, at enrollment | |||

| Year 1 | 389 (75) | 209 (75) | 180 (76) |

| Year 2 | 75 (15) | 43 (15) | 32 (14) |

| Year 3 | 52 (10) | 28 (10) | 24 (10) |

Statistically significant difference between intervention and control group (P < .05 by Wilcoxon or Pearson test).

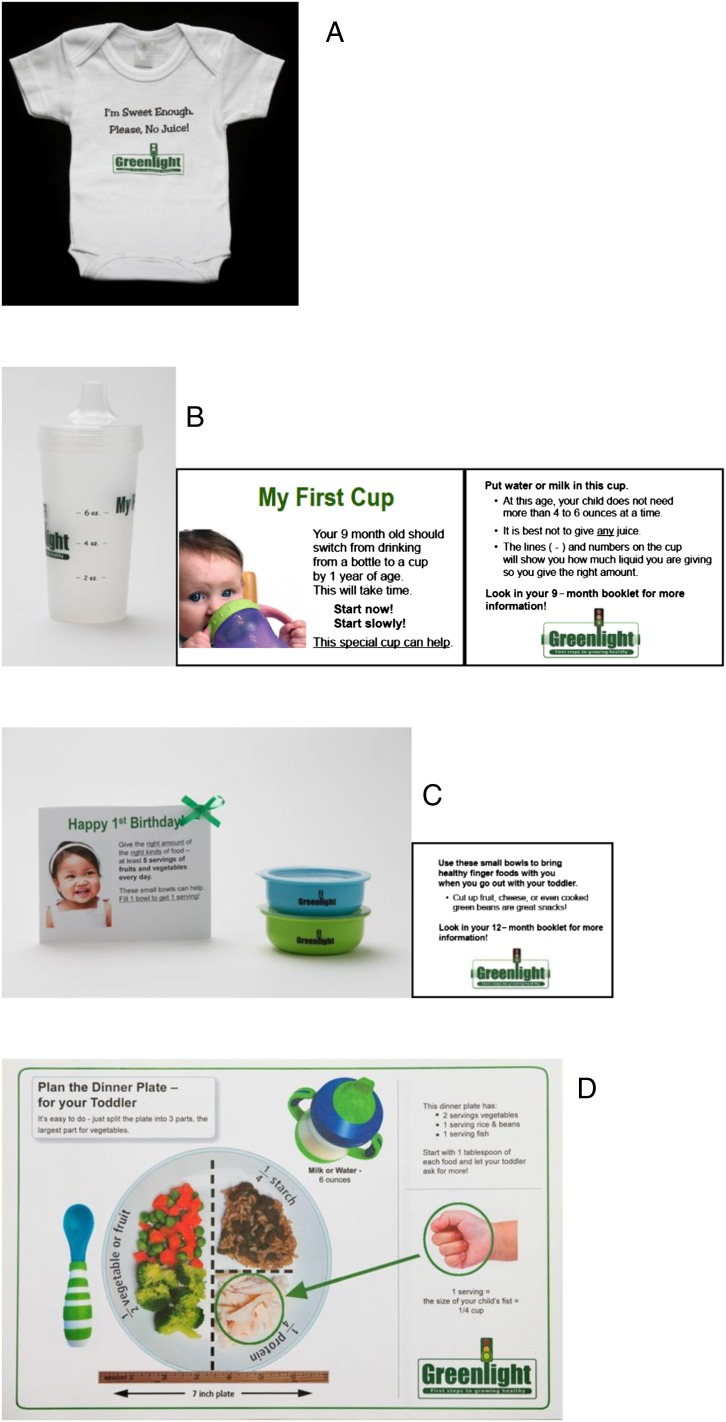

At 4 of the 6 well-child visits during study participation, the parent-child dyad receives a “tangible tool,” which is intended to promote intervention fidelity and to reinforce core messages (Fig 4). Each tangible tool cost <$4, with an estimated annual cost per child of <$8. At the 2-month and 9-month WCC, the tangible tool reinforces a message to limit intake of sweet drinks: at 2 months, an infant onesie that reads “I’m Sweet Enough. Please, No Juice!”; at 9 months, a Bisphenol A-free infant cup (“sippy cup”) with markings to help identify maximum daily juice intake and/or assist in juice dilution. (As part of the 9 month core messages, toolkits encourage parents to fill this and all cups primarily with water or milk, not juice.) At the 12-month and 15-month WCC, the tangible tool reinforces messages about portion size: at 12 months, 2 developmentally appropriate plastic snack bowls; at 15 months, a placemat illustrating a sample dinner plate with appropriate serving sizes for protein, starch, and fruits and vegetables.

FIGURE 4.

A, Tangible tool given at 2 months of age: t-shirt. B, Tangible tool given at 9 months of age: sippy cup. C, Tangible tool given at 12 months of age: portion-size bowls, with birthday card. D, Tangible tool given at 15 to 18 months of age: placemat showing portion sizes.

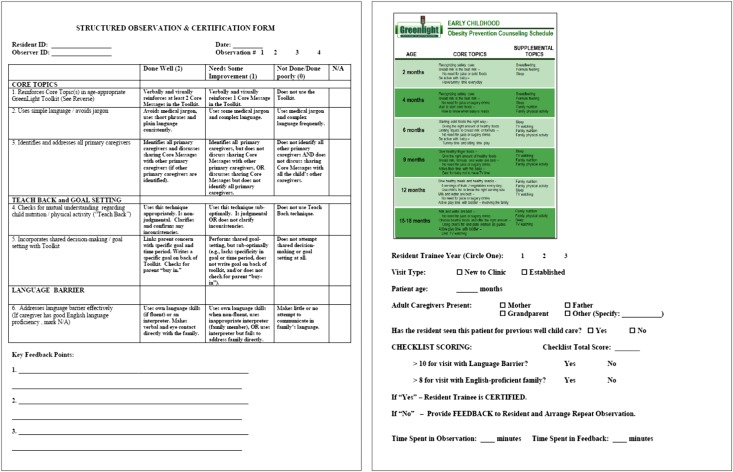

Physician Training Curriculum

Before study participation, each consenting resident physician is required to attend at least 1 hour of formal Greenlight Training and to exceed a threshold score on a Greenlight Certification Checklist (see below). Every 6 months after the initial training, each resident physician attended an additional Greenlight Booster Training, in person or by video-enabled webcast.

Applying the principles of active learning,73,74 the training curriculum used obesity prevention content to teach physician–parent communication skills in 3 domains: (1) clear health communication techniques (eg, plain language, “teach back” technique, and the effective use of printed materials)27,75–79; (2) cultural and linguistic competence (eg, family structure, community resources, and language interpreters),80 and (3) shared goal setting.81 Complementing the toolkit’s content, the physician-training curriculum promotes conversational dialogue with minimal jargon, reference to the toolkit’s pictures, and frequent verbal verification of understanding of information (eg, teach back). In addition to interpersonal communication, the curriculum addressed learner-centered content in each of the 6 competencies espoused by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education: medical knowledge (evidence-based behaviors associated with early childhood risk of obesity), patient care (improving anticipatory guidance into a routine preventive care visit), professionalism (respecting cultural differences in infant feeding practices), systems-based practice (curriculum that acknowledges obesity as a public-health problem), and practice-based knowledge (integration of the Greenlight intervention into daily practice).33,46 The interactive training sessions were facilitated by the PI and physician champions (including attending physicians and residents). Short, “trigger” videos portraying physician–parent encounters were employed to stimulate discussion and to demonstrate effective use of the Greenlight Toolkit. Each resident was also asked to pair off with another resident to role play scenarios with the use of the Greenlight Toolkit.

A trained research coordinator verified each resident’s acquisition of communication skills with the Greenlight Certification Checklist (Fig 5), completed in the examination room during a clinical encounter with a nonstudy-enrolled family. Adapted from the Observed Structured Clinical Examination-standardized observation tool,82 the Kalamazoo Consensus Statement Tool,83,84 and the “Set the stage, Elicit Information, Give information, Understand the patient's perspective, and End the encounter” (SEGUE) framework,85 the checklist includes 10 core items, with 2 additional items for encounters with limited English proficiency families. It assesses resident competencies in each of 3 domains: clear communication, cultural and linguistic competence, and shared goal setting. A threshold score of 8 (with limited English proficiency families, 10) was required for certification. Failure to exceed this threshold on an initial observation prompted brief feedback on areas for improvement and repeated observation at a subsequent clinic session until the threshold score was achieved.

FIGURE 5.

Observation checklist.

Active Control Group

At control sites, families received “usual care” with respect to obesity prevention, but as “active control” sites, they received implementation of The Injury Prevention Program (TIPP). In 1983, TIPP was designed by the American Academy of Pediatrics’ (AAP) Committee on Injury, Violence, and Poison Prevention to help pediatricians identify and address at-risk behaviors, to deliver developmentally appropriate anticipatory guidance, and provide written resources to parents and caregivers.86 For the purposes of this study, the AAP provided permission to use the English and Spanish language TIPP materials as designed and approved by the AAP as of September 1, 2009. For TIPP materials not available in Spanish, the research team’s advisory committed translated and adapted the materials into Spanish language, following the same process as applied to the Greenlight materials. To maintain equipoise in attention with the intervention group, the PIs also designed “TIPP Tangible Tools,” physician training modules in injury prevention, and physician observation checklists that accounted for developmentally appropriate injury prevention counseling. In keeping with active control principles, families and resident physicians at control sites received equal duration and frequency of attention as their counterparts at the intervention sites. Each resident physician at control sites received equal time of exposure to didactic training and examination room certification as their counterparts at intervention sites.

Measures

Trained, bilingual research assistants (RAs) conducted parent interviews in English or Spanish, based on the caregiver’s language of preference. Throughout the study, site PIs conducted periodic review and observation to ensure reliable data collection.

Characteristics of Child, Caregiver/Family, and Physician

A flowsheet of study recruitment is shown in Fig 6, and a summary of the baseline characteristics of the study population is shown in Tables 2 and 3. For each child, we collected the following baseline characteristics: date of birth, gender, race, ethnicity, birth history (including birth weight), medical history, health insurance status, initial feeding status (breast, bottle, both, and predominance of each), and out-of-home childcare. At 12 and 24 months, RAs abstracted additional information from each child’s medical record about child health care use, including preventive care visits, immunization history, and unscheduled acute care visits. After each study visit, the identity of the primary caregiver, the primary language used during the visit, and the pediatric resident providing the service were documented.

FIGURE 6.

Study flow.

From each participating primary caregiver, we collected the following characteristics: age, gender, race, ethnicity, years of education, household composition, country of birth, English-language proficiency, family income, employment status, sources of health information (including Internet and mobile), health status, food security, BMI (self-reported weight and height), depressive symptoms,87,88 acculturation level, as measured by the Short Acculturation Scale for Hispanics (SASH) and sources of health information.89,90 Caregiver health locus of control was measured with the 20-item Parent Health Beliefs Scale.91,92 Caregiver health literacy and numeracy skills were assessed at baseline with the Short Test of Functional Health Literacy (S-TOFHLA),93,94 and pediatric-specific health literacy skills with the Pediatric Health Literacy Assessment Test.36 Caregiver health numeracy skills were assessed at 6 months with the Wide Range Achievement Test,95 and at 9 months with Newest Vital Sign.96

For each resident physician, we collected the following socio-demographic characteristics at the time of study enrollment: age, gender, level of training, medical school location (inside versus outside the United States), and if the resident physician was a parent.

Outcomes

Child weight Status

The study’s primary outcome is the prevalence of child overweight or obesity at 24 months, defined by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention as BMI ≥ the 85th percentile, adjusting for age and gender.14,97 Weight and length measurements were collected at baseline and at each study visit by trained clinic staff on the basis of Department of Health and Human Services guidelines for accurate anthropomorphic measurement.98 We will also examine weight for length z scores on the basis of World Health Organization guidelines for children 0 to 2, and BMI z scores on the basis of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guidelines for children age 24 months.50,99

Family Health Behaviors

Parent-reported indicators of infant-feeding and physical-activity behaviors cover the following subdomains: (1) child and family activities (eg, sweetened beverages, “tummy time,” television time) and (2) parent self-efficacy, and (3) parent locus of control for specific behaviors. Whenever possible, survey items were derived from previously validated measures of infant feeding behaviors, infant and family physical activity and other early childhood health behaviors. Reports of infant feeding style were derived from the Infant Feeding Style Questionnaire.100 Developmentally appropriate reports of infant physical activity were adapted from the Early Childhood Longitudinal Study.101 When necessary, additional items to assess intervention-targeted behaviors were adapted from existing behavioral scales. This adaptation underwent iterative review by content experts (in the fields of pediatric obesity prevention and injury prevention) and methodological experts (in the fields of survey research, pediatric psychology and epidemiology). We also assessed parent-reported knowledge of obesity prevention recommendations and parent perception of child weight status.

Physician–Parent Communication

The Patient Communication Assessment Tool assessed primary caregiver’s satisfaction and perception of physician communication immediately after each WCC. 44,102 In addition to parent report of physician skills, resident physicians each self-reported the following: (1) competencies in health communication, (2) self-efficacy for anticipatory guidance, (3) knowledge, and (4) satisfaction. Scales to assess these outcomes were adapted from existing measures of satisfaction with and perception of physician–patient communication.103 RAs audiotaped a convenience sample (N = 20 per site) of 12- to 24-month WCC encounters, for later transcription and coding, to examine more thoroughly the content of physician–parent communication.

Analytic Plan

A total minimum sample size of 852 was calculated through a simulation study, powered at a β of over 80% to detect a 10% absolute difference between the intervention and comparison groups in the proportion of children at age 24 months with healthy weight status (>5th percentile and <85th percentile BMI). Intention-to-treat analyses of between-group differences will be performed by using generalized estimating equations, with adjustment for double clustering both at the level of the physician (pediatric resident) and at the level of the clinic, using a robust sandwich estimator to compute right variance-covariance matrix. Secondary analyses will examine between-group differences in the change of BMI z score at 24 months47,97–99 and the change in height/weight percentile over time, adjusted for an a priori defined set of covariates, including baseline height/weight percentile. When missing values exist in the covariates used in the model, we will perform a sensitivity analysis with imputed data sets through multiple imputation method. Our analysis is powered based on a 15:1 estimation of events per variable for a dichotomous outcome, and 15:1 samples per variable for a continuous outcome variable.

Caregiver health literacy will be examined as a primary predictor in most generalized estimating equation analyses. Interaction between health literacy (low versus adequate) and study status (intervention versus control) will be examined to determine if literacy level is a significant effect modifier. Similar analyses will be performed to examine the impact of other caregiver characteristics associated with child health outcomes (eg, ethnicity, educational attainment, family income, English-language proficiency, and acculturation) on the relationship between study status and primary outcomes.

Clinical and Public Health Implications

The IOM report on health literacy called for more experimental evidence to examine the role of health literacy in attenuating clinically significant health disparities that threaten morbidity and mortality.19 Because of its potential to significantly reduce morbidity across the life course, obesity prevention efforts during early childhood provide a unique opportunity to accumulate experimental evidence on the efficacy on low literacy approaches to clinical and preventive care. We anticipate that this study will help to assess the following overarching questions:

Can a parent counseling-based intervention delivered in pediatric primary care increase the adoption of healthy family behaviors and/or reduce the risk of childhood obesity at age 2 years?

What parent behaviors and attitudes during infancy are related to child obesity at age 2 years?

How do parent literacy and numeracy mediate these effects?

We know relatively little about the role of specific family behaviors (eg, breastfeeding, recognizing satiety clues, limiting television exposure) in determining an infant’s likelihood of developing clinically significant obesity. The Greenlight study affords the opportunity to explore these relationships. Furthermore, this study will allow clinicians and researchers to assess the modifiable roles of other social and cultural factors (eg, parent acculturation, parent locus of control, parent–clinician language discordance) in the early adoption of family health behaviors. Finally, as we follow this cohort through age 5 years, we will examine the sustained impact of the intervention into the critical periods of adiposity rebound and school entry.

Despite the large sample size and analytic approach, the sampling frame limits our ability to detect a small treatment effect and to generalize beyond low-income populations in urban and near-urban settings. The group-level differences in child, parent, and pediatric-provider baseline characteristics may introduce additional bias, which will require the use of general-estimating equations to adjust for baseline characteristics and clustering. The intervention period (2 to 24 months) limits our ability to judge the intervention’s effect during the preschool years, when adiposity rebound occurs and when the initial effects of obesity prevention may be more clinically meaningful. We are continuing to follow all study participants through age 5 years, however, to ascertain long-term impact and to monitor for study wash-out effects.

The results of this study may have significant implications for pediatric primary care, for medical training, and for public health practice. If the hypothesized study results were realized and the intervention replicated nationally among all infants, as many as 7 million additional infants may be kept within normal weight through age 2 years. If the hypothesized effect on child weight status is not detected, however, the study will be able to provide valuable information about the natural history of the infant-care behaviors (eg, feeding, physical activity) and about the trial’s impact on more proximate health-related outcomes (eg, doctor–parent interaction, physician behavior, and family health behaviors). Through the control arm, this study affords additional opportunity to assess the efficacy of the AAP’s TIPP program and to describe the natural history of injury-prevention behaviors during early childhood. More generally, study findings may also inform quality standards for primary-care practice and anticipatory guidance, including the Bright Futures Initiative and Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education competency-based standards for postgraduate training. Most importantly, the results of the Greenlight Intervention Study are likely to provide meaningful, evidence-based guidance to the improved delivery of clinical and preventive health care for all children.

Acknowledgments

The development and implementation of the Greenlight Intervention were made possible by the following members of the Greenlight Study Team: New York University School of Medicine/Bellevue Hospital Center: Alan Mendelsohn, Benard Dreyer, Linda van Schaick, Mary Jo Messito, Cynthia Osman, Steve Paik, Maria Cerra, Evelyn Cruzatte, Dana Kaplan, Omar Baker, Maureen Egan, and Leena Shiwbaren; Stanford University: Mairead Mahoney, Kasiemobi Udo-okoye, Pablo Uribe, Nathan Shaw, and Chinyelu Nwobu; University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill: Joanne Finkle (now at Duke University), Asheley Skinner, Tamera Coyne-Beasley, Michael Steiner, Sophie Ravanbakht, Brenda Calderon, Elizabeth Throop (now at Valley City State University), Carol Runyan (now at University of Colorado, Denver), and Mariana Garrettson; University of Miami/Jackson Memorial Medical Center: Anna Maria Patino-Fernandez, Alan Delamater, Lourdes Forster, Randi Sperling, Stephanie White, Lucila Bloise, and Daniela Quesada; Vanderbilt University: Shari Barkin, Sunil Kripilani, Ayumi Shintani, Sventlana Eden, Marina Margolin, Barron Paterson, and Seth Scholer. We also acknowledge support from the AAP for use of TIPP materials.

Glossary

- AAP

American Academy of Pediatrics

- PI

principal investigator

- RA

research assistant

- SCT

social cognitive theory

- S-TOFHLA

Short Test of Functional Health Literacy

- TIPP

The Injury Prevention Program

- WCC

well-child checkup

Footnotes

Dr Sanders conceptualized and designed the study and measures, supervised data collection and entry at the Miami University site, and drafted the original manuscript; Dr Perrin designed the study and measures, supervised data collection and entry at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill site, helped draft parts of the original manuscript, and reviewed and revised the original manuscript; Dr Yin designed the study and measures, supervised data collection and entry at the New York University site, helped draft parts of the original manuscript, and reviewed and revised the original manuscript; Dr Rothman conceptualized and designed the study and measures, supervised data collection at the Vanderbilt site, helped draft parts of the original manuscript, and reviewed and revised the original manuscript; and all authors approved the final manuscript as submitted.

This trial has been registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov (identifier NCT01040897).

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE: The authors have indicated they have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

FUNDING: All phases of this study were supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Development (grant R01 HD049794), with supplemental funding from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and Office of Behavioral and Social Science Research (grants R01HD059794-04S1 and R01HD059794-04S2). Parts of the study were supported by the National Institutes of Health’s National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences through its Clinical and Translational Science Awards Program, grants 1UL1RR029893, UL1TR000445, and UL1RR025747, as well as the National Institutes of Health DK56350 to fund the Nutrition Obesity Research Center at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill. Dr Yin is supported by a grant under the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Physician Faculty Scholars Program and the Health Resources and Services Administration (12-191-1077 Academic Administrative Units in Primary Care) and by funding from the KiDS of the New York University Langone Foundation. National Institutes of Health (NIH).

POTENTIAL CONFLICT OF INTEREST: The authors have indicated they have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Barlow SE. Expert Committee. Expert committee recommendations regarding the prevention, assessment, and treatment of child and adolescent overweight and obesity: summary report. Pediatrics. 2007;120(suppl 4):S164–S192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Flegal KM. Prevalence of obesity and trends in body mass index among US children and adolescents, 1999-2010. JAMA. 2012;307(5):483–490 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sherry B, Mei Z, Scanlon KS, Mokdad AH, Grummer-Strawn LM. Trends in state-specific prevalence of overweight and underweight in 2- through 4-year-old children from low-income families from 1989 through 2000. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2004;158(12):1116–1124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Suminski RR, Poston WS, Jackson AS, Foreyt JP. Early identification of Mexican American children who are at risk for becoming obese. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1999;23(8):823–829 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Taveras EM, Rifas-Shiman SL, Belfort MB, Kleinman KP, Oken E, Gillman MW. Weight status in the first 6 months of life and obesity at 3 years of age. Pediatrics. 2009;123(4):1177–1183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ciampa PJ, Kumar D, Barkin SL, et al. Interventions aimed at decreasing obesity in children younger than 2 years: a systematic review. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2010;164(12):1098–1104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nader PR, O’Brien M, Houts R, et al. National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Early Child Care Research Network . Identifying risk for obesity in early childhood. Pediatrics. 2006;118(3). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/118/3/e594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dennison BA, Edmunds LS, Stratton HH, Pruzek RM. Rapid infant weight gain predicts childhood overweight. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2006;14(3):491–499 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leunissen RW, Kerkhof GF, Stijnen T, Hokken-Koelega A. Timing and tempo of first-year rapid growth in relation to cardiovascular and metabolic risk profile in early adulthood. JAMA. 2009;301(21):2234–2242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dietz WH, Robinson TN. Clinical practice. Overweight children and adolescents. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(20):2100–2109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Freedman DS, Mei Z, Srinivasan SR, Berenson GS, Dietz WH. Cardiovascular risk factors and excess adiposity among overweight children and adolescents: the Bogalusa Heart Study. J Pediatr. 2007;150(1):12–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goran MI, Lane C, Toledo-Corral C, Weigensberg MJ. Persistence of pre-diabetes in overweight and obese Hispanic children: association with progressive insulin resistance, poor beta-cell function, and increasing visceral fat. Diabetes. 2008;57(11):3007–3012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Molleston JP, White F, Teckman J, Fitzgerald JF. Obese children with steatohepatitis can develop cirrhosis in childhood. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97(9):2460–2462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barlow SE, Dietz WH. Obesity evaluation and treatment: Expert Committee recommendations. The Maternal and Child Health Bureau, Health Resources and Services Administration and the Department of Health and Human Services. Pediatrics. 1998;102(3). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/102/3/e29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Golan M. Parents as agents of change in childhood obesity—from research to practice. Int J Pediatr Obes. 2006;1(2):66–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Carmona RH. Improving Americans’ health literacy. J Am Diet Assoc. 2005;105(9):1345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Carmona RH. Health Literacy in America: The Role of Health Care Professionals. Prepared remarks given at the American Medical Association House of Delegates Meeting. June 14, 2003

- 18.Kutner M, Greenberg E, Jin Y, Paulsen C. Literacy in Everyday Life Results From the 2003 National Assessment of Adult Literacy. NCES 2007-480. US Department of Education. Washington, DC: National Center for Education Statistics; 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nielsen-Bohlman L, Panzer AM, Kindig DA, eds. Health Literacy: A Prescription to End Confusion. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2004 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dewalt DA, Berkman ND, Sheridan S, Lohr KN, Pignone MP. Literacy and health outcomes: a systematic review of the literature. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19(12):1228–1239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Health literacy: report of the Council on Scientific Affairs. Ad Hoc Committee on Health Literacy for the Council on Scientific Affairs, American Medical Association. JAMA. 1999;281(6):552–557 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Arnold CL, Davis TC, Frempong JO, et al. Assessment of newborn screening parent education materials. Pediatrics. 2006;117(5 pt 2):S320–S325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Baker DW, Parker RM, Williams MV, et al. The health care experience of patients with low literacy. Arch Fam Med. 1996;5(6):329–334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Berkman ND, Dewalt DA, Pignone MP, et al. Literacy and health outcomes. Evid Rep Technol Assess (Summ). 2004; (87):1–8 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Davis TC, Bocchini JA, Jr, Fredrickson D, et al. Parent comprehension of polio vaccine information pamphlets. Pediatrics. 1996;97(6 pt 1):804–810 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Davis TC, Mayeaux EJ, Fredrickson D, Bocchini JA, Jr, Jackson RH, Murphy PW. Reading ability of parents compared with reading level of pediatric patient education materials. Pediatrics. 1994;93(3):460–468 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mayeaux EJ, Jr, Murphy PW, Arnold C, Davis TC, Jackson RH, Sentell T. Improving patient education for patients with low literacy skills. Am Fam Physician. 1996;53(1):205–211 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Montori VM, Rothman RL. Weakness in numbers. The challenge of numeracy in health care. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20(11):1071–1072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pignone M, DeWalt DA, Sheridan S, Berkman N, Lohr KN. Interventions to improve health outcomes for patients with low literacy. A systematic review. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20(2):185–192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rothman R, Malone R, Bryant B, Horlen C, DeWalt D, Pignone M. The relationship between literacy and glycemic control in a diabetes disease-management program. Diabetes Educ. 2004;30(2):263–273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rothman RL, DeWalt DA, Malone R, et al. Influence of patient literacy on the effectiveness of a primary care-based diabetes disease management program. JAMA. 2004;292(14):1711–1716 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rothman RL, Malone R, Bryant B, et al. The Spoken Knowledge in Low Literacy in Diabetes scale: a diabetes knowledge scale for vulnerable patients. Diabetes Educ. 2005;31(2):215–224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schillinger D, Piette J, Grumbach K, et al. Closing the loop: physician communication with diabetic patients who have low health literacy. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163(1):83–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Huizinga MM, Beech BM, Cavanaugh KL, Elasy TA, Rothman RL. Low numeracy skills are associated with higher BMI. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2008;16(8):1966–1968 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Huizinga MM, Carlisle AJ, Cavanaugh KL, et al. Literacy, numeracy, and portion-size estimation skills. Am J Prev Med. 2009;36(4):324–328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kumar D, Sanders L, Perrin EM, et al. Parental understanding of infant health information: health literacy, numeracy, and the Parental Health Literacy Activities Test (PHLAT). Acad Pediatr. 2010;10(5):309–316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Houts PS, Doak CC, Doak LG, Loscalzo MJ. The role of pictures in improving health communication: a review of research on attention, comprehension, recall, and adherence. Patient Educ Couns. 2006;61(2):173–190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rothman RL, Housam R, Weiss H, et al. Patient understanding of food labels: the role of literacy and numeracy. Am J Prev Med. 2006;31(5):391–398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Oettinger MD, Finkle JP, Esserman D, et al. Color-coding improves parental understanding of body mass index charting. Acad Pediatr. 2009;9(5):330–338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yin HS, Dreyer BP, Vivar KL, MacFarland S, van Schaick L, Mendelsohn AL. Perceived barriers to care and attitudes towards shared decision-making among low socioeconomic status parents: role of health literacy. Acad Pediatr. 2012;12(2):117–124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.American Dietetic Association (ADA) . Position of the American Dietetic Association: individual-, family-, school-, and community-based interventions for pediatric overweight. J Am Diet Assoc. 2006;106(6):925–945 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bluford DA, Sherry B, Scanlon KS. Interventions to prevent or treat obesity in preschool children: a review of evaluated programs. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2007;15(6):1356–1372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Summerbell CD. The identification of effective programs to prevent and treat overweight preschool children. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2007;15(6):1341–1342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Krugman SD, Racine A, Dabrow S, et al. Continuity Research Network . Measuring primary care of children in pediatric resident continuity practices: a Continuity Research Network study. Pediatrics. 2007;120(2). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/120/2/e262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Eisenberg JM. Sociologic influences on decision-making by clinicians. Ann Intern Med. 1979;90(6):957–964 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kripalani S, Weiss BD. Teaching about health literacy and clear communication. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(8):888–890 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cull WL, Yudkowsky BK, Shipman SA, Pan RJ, American Academy of Pediatrics . Pediatric training and job market trends: results from the American Academy of Pediatrics third-year resident survey, 1997–2002. Pediatrics. 2003;112(4):787–792 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Frintner MP, Cull WL. Pediatric training and career intentions, 2003-2009. Pediatrics. 2012;129(3):522–528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Serwint JR, Thoma KA, Dabrow SM, et al. CORNET Investigators . Comparing patients seen in pediatric resident continuity clinics and national ambulatory medical care survey practices: a study from the continuity research network. Pediatrics. 2006;118(3). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/118/3/e849 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.WHO Multicentre Growth Reference Study Group . WHO Child Growth Standards based on length/height, weight and age. Acta Paediatr Suppl. 2006;450:76–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bandura A. Social Foundations of Thought and Action: A Social Cognitive Theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall; 1986 [Google Scholar]

- 52.Choudhry NK, Fletcher RH, Soumerai SB. Systematic review: the relationship between clinical experience and quality of health care. Ann Intern Med. 2005;142(4):260–273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Davis TC, Fredrickson DD, Bocchini C, et al. Improving vaccine risk/benefit communication with an immunization education package: a pilot study. Ambul Pediatr. 2002;2(3):193–200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Doak CC, Doak LG, Root JH. Teaching patients with low literacy skills, 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: J.B. Lippincott; 1996 [Google Scholar]

- 55.Edwards A, Elwyn G, Mulley A. Explaining risks: turning numerical data into meaningful pictures. BMJ. 2002;324(7341):827–830 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Davis TC, Gazmararian J, Kennen EM. Approaches to improving health literacy: lessons from the field. J Health Commun. 2006;11(6):551–554 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Anzman SL, Rollins BY, Birch LL. Parental influence on children’s early eating environments and obesity risk: implications for prevention. Int J Obes (Lond). 2010;34(7):1116–1124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Johnson SL, Birch LL. Parents’ and children’s adiposity and eating style. Pediatrics. 1994;94(5):653–661 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Reilly JJ, Armstrong J, Dorosty AR, et al. Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children Study Team . Early life risk factors for obesity in childhood: cohort study. BMJ. 2005;330(7504):1357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Robinson TN. Reducing children’s television viewing to prevent obesity: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 1999;282(16):1561–1567 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wardle J, Sanderson S, Guthrie CA, Rapoport L, Plomin R. Parental feeding style and the inter-generational transmission of obesity risk. Obes Res. 2002;10(6):453–462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lindsay AC, Sussner KM, Kim J, Gortmaker S. The role of parents in preventing childhood obesity. Future Child. 2006;16(1):169–186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Baker JL, Michaelsen KF, Rasmussen KM, Sørensen TI. Maternal prepregnant body mass index, duration of breastfeeding, and timing of complementary food introduction are associated with infant weight gain. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;80(6):1579–1588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bonuck KA, Huang V, Fletcher J. Inappropriate bottle use: an early risk for overweight? Literature review and pilot data for a bottle-weaning trial. Matern Child Nutr. 2010;6(1):38–52 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bonuck KA, Kahn R. Prolonged bottle use and its association with iron deficiency anemia and overweight: a preliminary study. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2002;41(8):603–607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Dennison BA, Erb TA, Jenkins PL. Television viewing and television in bedroom associated with overweight risk among low-income preschool children. Pediatrics. 2002;109(6):1028–1035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Fisher JO, Arreola A, Birch LL, Rolls BJ. Portion size effects on daily energy intake in low-income Hispanic and African American children and their mothers. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;86(6):1709–1716 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Fox MK, Devaney B, Reidy K, Razafindrakoto C, Ziegler P. Relationship between portion size and energy intake among infants and toddlers: evidence of self-regulation. J Am Diet Assoc. 2006;106(1 suppl 1):S77–S83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Janz KF, Levy SM, Burns TL, Torner JC, Willing MC, Warren JJ. Fatness, physical activity, and television viewing in children during the adiposity rebound period: the Iowa Bone Development Study. Prev Med. 2002;35(6):563–571 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wardle J, Carnell S, Haworth CM, Farooqi IS, O’Rahilly S, Plomin R. Obesity associated genetic variation in FTO is associated with diminished satiety. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93(9):3640–3643 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Welsh JA, Cogswell ME, Rogers S, Rockett H, Mei Z, Grummer-Strawn LM. Overweight among low-income preschool children associated with the consumption of sweet drinks: Missouri, 1999-2002. Pediatrics. 2005;115(2). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/115/2/e223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Faith MS, Dennison BA, Edmunds LS, Stratton HH. Fruit juice intake predicts increased adiposity gain in children from low-income families: weight status-by-environment interaction. Pediatrics. 2006;118(5):2066–2075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.DeWalt DA, Wallace AS, Seligman HK, et al. Behavior change using low-literacy educational materials and brief counseling among vulnerable patients with diabetes. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;22(1):145 [Google Scholar]

- 74.Knowles MS. The Adult Learner: A Neglected Species, 4th ed. Houston, TX: Gulf Publishing Company; 1990 [Google Scholar]

- 75.Williams MV, Davis T, Parker RM, Weiss BD. The role of health literacy in patient-physician communication. Fam Med. 2002;34(5):383–389 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Whitlock EP, Orleans CT, Pender N, Allan J. Evaluating primary care behavioral counseling interventions: an evidence-based approach. Am J Prev Med. 2002;22(4):267–284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Towle A, Godolphin W. Framework for teaching and learning informed shared decision making. BMJ. 1999;319(7212):766–771 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Flowers L. Teach-back improves informed consent. OR Manager. 2006;22(3):25–26 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Mellins RB, Evans D, Clark N, Zimmerman B, Wiesemann S. Developing and communicating a long-term treatment plan for asthma. Am Fam Physician. 2000;61(8):2419–2428, 2433–2434 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Beach MC, Price EG, Gary TL, et al. Cultural competence: a systematic review of health care provider educational interventions. Med Care. 2005;43(4):356–373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Elder JP, Ayala GX, Harris S. Theories and intervention approaches to health-behavior change in primary care. Am J Prev Med. 1999;17(4):275–284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Carraccio C, Englander R. The objective structured clinical examination: a step in the direction of competency-based evaluation. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2000;154(7):736–741 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Makoul G. Essential elements of communication in medical encounters: the Kalamazoo consensus statement. Acad Med. 2001;76(4):390–393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Duffy FD, Gordon GH, Whelan G, et al. Participants in the American Academy on Physician and Patient’s Conference on Education and Evaluation of Competence in Communication and Interpersonal Skills . Assessing competence in communication and interpersonal skills: the Kalamazoo II report. Acad Med. 2004;79(6):495–507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Makoul G. The SEGUE Framework for teaching and assessing communication skills. Patient Educ Couns. 2001;45(1):23–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Krassner L. TIPP usage. Pediatrics. 1984;74(5 pt 2):976–980 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Radloff LS. The CES-D Scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas. 1977;1(3):385–401 [Google Scholar]

- 88.Vázquez FL, Blanco V, López M. An adaptation of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale for use in non-psychiatric Spanish populations. Psychiatry Res. 2007;149(1–3):247–252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Nord M, Hopwood H. Recent advances provide improved tools for measuring children’s food security. J Nutr. 2007;137(3):533–536 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Harrison GG, Stormer A, Herman DR, Winham DM. Development of a Spanish-language version of the U.S. household food security survey module. J Nutr. 2003;133(4):1192–1197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Tinsley BJ, Holtgrave DR. Maternal health locus of control beliefs, utilization of childhood preventive health services, and infant health. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 1989;10(5):236–241 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Pachte LM, Sheehan J, Cloutier MM. Factor and subscale structure of a parental health locus of control instrument (parental health beliefs scales) for use in a mainland United States Puerto Rican community. Soc Sci Med. 2000;50(5):715–721 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Parker RM, Baker DW, Williams MV, Nurss JR. The test of functional health literacy in adults: a new instrument for measuring patients’ literacy skills. J Gen Intern Med. 1995;10(10):537–541 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Baker DW, Williams MV, Parker RM, Gazmararian JA, Nurss J. Development of a brief test to measure functional health literacy. Patient Educ Couns. 1999;38(1):33–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Wilkinson G. WRAT-3: Wide Range Achievement Test, Administration Manual. Wilmington, DE: Wide Range, Inc.; 1993 [Google Scholar]

- 96.Weiss BD, Mays MZ, Martz W, et al. Quick assessment of literacy in primary care: the newest vital sign. Ann Fam Med. 2005;3(6):514–522 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics 2000 CDC Growth Charts for the United States. DHHS Publication. Hyattsville, MD: Public Health Service; 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 98.Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Growth chart training. Department of Health and Human Services; 2008. Available at: http://depts.washington.edu/growth/module5/text/page4a.htm. Accessed October 13, 2013

- 99.Ogden CL, Kuczmarski RJ, Flegal KM, et al. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2000 growth charts for the United States: improvements to the 1977 National Center for Health Statistics version. Pediatrics. 2002;109(1):45–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Thompson AL, Mendez MA, Borja JB, Adair LS, Zimmer CR, Bentley ME. Development and validation of the Infant Feeding Style Questionnaire. Appetite. 2009;53(2):210–221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Institute of Education Sciences. Early Child Longitudinal Program. National Center for Education Statistics. Available at: http://nces.ed.gov/ecls/kindergarten.asp. Accessed October 13, 2013

- 102.Makoul G, Krupat E, Chang CH. Measuring patient views of physician communication skills: development and testing of the Communication Assessment Tool. Patient Educ Couns. 2007;67(3):333–342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Serwint JR, Continuity Clinic Special Interest Group, Ambulatory Pediatric Association . Multisite survey of pediatric residents’ continuity experiences: their perceptions of the clinical and educational opportunities. Pediatrics. 2001;107(5). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/107/5/e78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]