Abstract

OBJECTIVES:

To investigate the hypothesis that exposure to alcohol consumption in movies affects the likelihood that low-risk adolescents will start to drink alcohol.

METHODS:

Longitudinal study of 2346 adolescent never drinkers who also reported at baseline intent to not to do so in the next 12 months (mean age 12.9 years, SD = 1.08). Recruitment was carried out in 2009 and 2010 in 112 state-funded schools in Germany, Iceland, Italy, Netherlands, Poland, and Scotland. Exposure to movie alcohol consumption was estimated from 250 top-grossing movies in each country in the years 2004 to 2009. Multilevel mixed-effects Poisson regressions assessed the relationship between baseline exposure to movie alcohol consumption and initiation of trying alcohol, and binge drinking (≥ 5 consecutive drinks) at follow-up.

RESULTS:

Overall, 40% of the sample initiated alcohol use and 6% initiated binge drinking by follow-up. Estimated mean exposure to movie alcohol consumption was 3653 (SD = 2448) occurrences. After age, gender, family affluence, school performance, TV screen time, personality characteristics, and drinking behavior of peers, parents, and siblings were controlled for, exposure to each additional 1000 movie alcohol occurrences was significantly associated with increased relative risk for trying alcohol, incidence rate ratio = 1.05 (95% confidence interval, 1.02–1.08; P = .003), and for binge drinking, incidence rate ratio = 1.13 (95% confidence interval, 1.06–1.20; P < .001).

CONCLUSIONS:

Seeing alcohol depictions in movies is an independent predictor of drinking initiation, particularly for more risky patterns of drinking. This result was shown in a heterogeneous sample of European youths who had a low affinity for drinking alcohol at the time of exposure.

Keywords: alcohol imagery, movies, binge drinking, young people, Europe

What’s Known on This Subject:

Several experimental and observational studies reveal an association between exposure to alcohol consumption in movies and youth drinking, but little is known about the effect of such exposure on drinking onset among low-risk adolescents.

What This Study Adds:

In a longitudinal study, exposure to alcohol consumption in movies was associated with drinking initiation in a sample of adolescents from 6 European countries who had never drunk alcohol and were attitudinally nonsusceptible to future use at the time of exposure.

The causes of alcohol use and misuse in young people are multifactorial and include cultural norms, parental and peer influences, personality traits, alcohol use expectancies, and hereditary factors.1 In the last decade some attention has been given to the question of whether alcohol exposure in the media might also account for variance in young people’s alcohol consumption. The theoretical background for these studies is social learning theory, which suggests that behavior is learned from the environment as people observe and then imitate the actions of influential others.2 Such models include parents, friends, teachers, and characters depicted in the media or advertising. For example, given access to cigarettes and alcohol in a Barbie play scenario, preschool children will enact smoking and alcohol scripts in their play, scripts they have learned from watching their parents.3

Alcohol portrayals are widespread in the mass media. A recent content analysis of popularly viewed television in the United Kingdom found that alcohol imagery occurred in >40% of broadcasts.4 In movies, alcohol use and brand appearances are even more prevalent: Some 86% of movies popular in the United Kingdom5 and 83% of Hollywood blockbusters6 depicted alcohol use. More importantly, results from experimental7–9 and cross-sectional observational studies10–12 have shown a consistent link between exposure to alcohol use in movies and drinking behavior in young people. This association has also been shown in 3 cohorts recruited in New England,13 across the United States,14–17 and in northern Germany.18

One gap in the literature to date is that little is known about the effect of exposure to drinking in movies on drinking among low-risk adolescents, those who have never drunk alcohol and are attitudinally nonsusceptible to future use. Conceptually, this is a very important group, because they can shed more light on the temporal sequence of the exposure–behavior link (it is hard to imagine how they could be drawn to movies with alcohol because of favorable attitudes toward drinking at baseline). Empirically, they are extremely difficult to study, because usually only a small proportion of an early- to mid-adolescent sample belongs to this group, and analyses fail because of a lack of statistical power. One could solve these sample size problems by studying younger age groups (eg, 6- to 10-year-olds). However, the central behavioral outcomes under question are alcohol use and misuse initiation, and this cannot be realistically studied in young children or requires a long follow-up period.

From 2009 to 2011 we conducted a large European study on the effects of movies on smoking and drinking behavior of young people.12,19,20 In this study, 16 551 adolescents from 6 countries (from Germany, Iceland, Italy, Poland, Netherlands, and Scotland) were interviewed at baseline, and >80% of these were followed up 12 months later. The sample size of this study provides a unique opportunity to perform subsample analyses such as the one outlined earlier. In addition, it is one of the few longitudinal studies on alcohol use in movies and only the second ever conducted outside the United States. The 6 European countries involved in the study show variation in both alcohol policies and prevalence of alcohol use in young people.21,22 This variation provides valuable insight into the robustness and consistency of media effects across different cultural contexts.

In this article we present results on the longitudinal association between alcohol use in movies and drinking outcomes in adolescents who have never used alcohol in their lives, not even a sip, and indicated at baseline that they would “definitely not” drink alcohol in the next year and “definitely not” drink alcohol offered by friends. As primary outcomes we studied the initiation of ever drinking and binge drinking.

Methods

Design, Procedure, and Study Sample

A school-based longitudinal study was conducted in 6 European countries by research centers in Germany (Kiel), Iceland (Reykjavik), Italy (Turin and Novara), Poland (Poznan), Netherlands (Nijmegen), and Scotland (Glasgow). Study samples were all recruited from state-funded schools, with data collected through self-completion questionnaires overseen by trained research staff. Participants were given assurances about confidentiality and anonymity, and each completed questionnaire was placed in an envelope and sealed in front of participants to reassure them that teachers, peers, or family members would not see them. To permit linking of the baseline and follow-up surveys, identical questionnaire front sheets allowed participants to generate individual 7-character codes (based on prespecified digits or letters from memorable names and dates, including date of birth and mother’s first name). This procedure has been tested in previous studies.23 Ethical approval for the research was gained from the relevant body in each country. Additional approvals (eg, from educational authorities and individual head teachers) were sought as required. Additional details are given elsewhere.12

Pupils were recruited from 865 classes in 114 schools. Baseline surveys (n = 16 551) were conducted between November 2009 and June 2010 (mean age 13.4 years, SD = 1.18), and follow-up surveys were conducted between January and May 2011 (mean between-wave interval = 12 months, range 10–14 months). Of these 16 551 pupils it was possible to match follow-up data for 13 642 pupils (82%) from 843 classes in 112 schools. Following a concept of Pierce et al,24 we measured susceptibility toward future alcohol use by asking pupils at baseline, “Do you think you will drink alcohol one year from now?” and “If one of your best friends were to offer you alcohol, would you drink it?” Response options were “Definitely yes,” “Probably yes,” “Probably not,” and “Definitely not.” Some 2706 pupils had never drunk alcohol in their lives, not even a sip, at baseline and indicated that they would “definitely not” drink alcohol in the next year and would “definitely not” drink alcohol offered by friends. This is the sample for the present analysis of drinking onset. Country-specific overall matching rates and other sample details are given in the Appendix.

Measures

Exposure to Alcohol Use in Movies

Exposure to alcohol consumption in movies was assessed by using a method developed by researchers at Dartmouth Medical School. This method relies on the recall of having seen movies presented to respondents as a list of movie titles.25 First, the research centers in each country compiled a master list of the 250 most commercially successful box office hits in their country, using publicly available data on movie revenues. Each country-specific master list contained the top 50 box office hits for the years 2005 to 2008 and the 25 most successful movies for the years 2004 and 2009. Then, through a process of random selection from the master list, each pupil was presented with a unique list of 50 movies from their country-specific list. To minimize between-subject variation in the composition of the individual lists, the random selection of movies was stratified by year of release and country-specific age rating. Pupils indicated how often (never, once, twice, >2 times) they had seen each movie on their unique list. For the present analysis, answers were dichotomized into “ever seen” and “never seen.”

In a parallel procedure, all included movies were content coded with regard to alcohol use occurrences. Because of a high overlap of box office hits between countries, the complete sample of 1500 movies (6 countries, 250 movies each) contained 655 different movies. Fifty-six percent (n = 368) had already been content coded at the Dartmouth Media Research Laboratory. The remaining 44% (n = 287) were content coded in the 6 European study centers. In this coding process, trained coders reviewed each movie and counted the number of occurrences of on-screen alcohol use. An alcohol occurrence was counted whenever a major or minor character handled or used alcohol in a scene or when alcohol use was shown in the background (eg, extras drinking alcohol in a bar scene). Occurrences were counted each time alcohol use appeared on the screen. Interrater reliability was studied via 2 types of correlations: (1) between the coding results of the European coders and the European trainer on a selected number of training movies and (2) between the European trainer and the Dartmouth coders, based on a blinded European recoding of a random sample of 40 Dartmouth-coded movies. European coder–trainer correlations ranged from r = 0.93 (Iceland) to r = 0.99 (Italy); the European recounts of alcohol occurrences in the random movie selection correlated (r = 0.87) with the Dartmouth counts.

We calculated exposure to alcohol use in movies for all pupils by summing the number of alcohol occurrences in each movie they had seen. To adjust the measure for variation in the country-specific movie lists, individual exposure to movie alcohol use was expressed as a proportion of the total number of possible alcohol occurrences each pupil could have seen on the basis of the movies included in his or her unique list of 50 movies. The final exposure estimate was the proportion of alcohol occurrences the adolescent had seen in his or her unique list multiplied by the number of alcohol occurrences in the 250 movies of that country.

Drinking Behavior

Both surveys included identical questions about alcohol use. We asked participants, “Have you ever drunk any alcohol, even just a sip?” (yes/no). Those responding “yes” at follow-up were categorized as having initiated any kind of alcohol use over the follow-up period. The transition from nondrinker to having any experience of binge drinking was assessed through the question, “How often have you had 5 or more drinks of alcohol on one occasion?” Response categories were 0 = never, 1 = once, 2 = 2 to 5 times, or 3 = >5 times. Pupils who reported never were classified as “never binge drinkers” and all others as “ever binge drinkers.”

Covariates

A number of covariates were included (Table 1) that could confound or modify the relationship between exposure to alcohol use in movies and drinking initiation, including sociodemographic (gender, age, family affluence), personal (school performance, TV screen time, sensation seeking and rebelliousness), and social environmental (drinking of peers, parents, and siblings) characteristics.

TABLE 1.

Covariates and Their Assessment

| Variable | Survey Question | Response Categories |

|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographics | ||

| Age | How old are you? | Years |

| Gender | Are you a girl or a boy? | Boy, Girl |

| Family affluence scale | Does your family own a car, van, or truck? | No, Yes: 1, 2, or more |

| Do you have your own bedroom for yourself? | No, Yes | |

| During the past 12 mo, how many times did you travel away on holiday with your family? | Not at all, Once, Twice, More than twice | |

| How many computers does your family own? | None, 1, 2, More than 2 | |

| Personal characteristics | ||

| School performance | How would you describe your grades last year? | Excellent, Good, Average, Below average |

| TV screen time | On a school day, how many hours a day do you usually spend watching TV? | None, Less than 1 h, 1–2 h, 3–4 h, More than 4 h |

| Number of movies seen | Below is a list of movie titles. Please mark if, and how often, you have seen each movie. | Never, Once, Twice, More than twice |

| Sensation seeking or rebelliousness (Cronbach’s α = 0.70) | How often do you do dangerous things for fun? | Not at all, Once in a while, Sometimes, Often, Very often |

| How often do you do exciting things, even if they are dangerous? | ||

| I believe in following rules. (recoded) | Not at all, A bit, Quite well, Very well | |

| I get angry when anybody tells me what to do. | ||

| Social environment | ||

| Peer drinking | How many of your friends drink alcohol? | None, A few, Some, Most, All |

| Mother drinking | How often does your mother or female guardian drink alcohol? | Never, Seldom, Often but not every day, Every day |

| Don’t have (coded “no”) | ||

| Father drinking | How often does your father or male guardian drink alcohol? | Never, Seldom, Often but not every day, Every day |

| Don’t have (coded “no”) | ||

| Sibling drinking | Do any of your brothers or sisters drink alcohol? | Yes, No, Don’t have (coded “no”) |

Statistical Analysis

All data analyses were conducted in 2013 with Stata version 13.0 (Stata Corp, College Station, TX). Baseline differences between successfully followed-up and lost students were analyzed by using χ2 and t tests. Adjusted associations between exposure to alcohol use in movies and drinking initiation were analyzed with multilevel mixed-effects Poisson regressions (uncentered data in all analyses). Poisson regression allows the presentation of incidence rate ratios (IRRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the relationship between movie alcohol use occurrences and initiation of any drinking and of binge drinking. IRRs were calculated in respect of exposure to every 1000 alcohol occurrences. Because the data were clustered at the country, school, and classroom level, random intercepts for all 3 levels were included in the adjusted models. In these models, movie alcohol use and all covariates were entered as fixed effects. Multiple pairwise comparisons after logistic regression were Bonferroni adjusted. Missing data were handled by listwise deletion.

A sensitivity analysis was undertaken to assess for differential country-specific associations between movie alcohol exposure and the 2 alcohol initiation outcomes. Instead of using the country of data assessment as a random effect in the regression model, we included an exposure × country interaction term to test for differential country-specific associations.

Results

Descriptive Statistics at Baseline and Attrition Analysis

Table 2 lists descriptive statistics for all nonsusceptible never drinkers at baseline, for those lost to follow-up, and for the final analyzed sample, allowing comparisons of differences due to attrition. Never drinkers lost to follow-up had higher exposure to alcohol use in movies, were more often recruited from schools in Poland and less often from schools in Italy, were significantly older, rated their school performance more poorly, had higher scores on the sensation seeking and rebelliousness scale, had more friends and siblings who drink alcohol, and more often had fathers who never drink alcohol.

TABLE 2.

Descriptive Statistics at Baseline, and Attrition Analysis, %

| Baseline Nonsusceptible Never-Drinkers (n = 2706) | Lost to Follow-Up (n = 380) | Analyzed Sample (n = 2326) | Lost to Follow-Up Versus Analyzed Sample P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country | ||||

| Germany | 21.7 | 21.8 | 21.6 (n = 503) | <.01 |

| Iceland | 35.4 | 36.8 | 35.2 (n = 819) | |

| Italy | 12.9 | 8.7 | 13.6 (n = 315) | |

| Netherlands | 4.2 | 3.4 | 4.3 (n = 101) | |

| Poland | 15.1 | 20.3 | 14.3 (n = 332) | |

| Scotland | 10.7 | 8.9 | 11.0 (n = 256) | |

| Sociodemographics | ||||

| Age at baseline (y), M (SD) | 12.91 (1.10) | 13.18 (1.15) | 12.86 (1.08) | <.001 |

| Gender | ||||

| Female | 53.9 | 50.0 | 54.6 | .101 |

| Male | 46.1 | 50.0 | 45.5 | |

| Family affluence | ||||

| Low | 9.2 | 11.3 | 8.9 | .198 |

| Medium | 36.6 | 37.9 | 36.3 | |

| High | 54.2 | 50.8 | 54.8 | |

| Personal Characteristics | ||||

| School performance | ||||

| Below average | 4.0 | 3.7 | 6.4 | <.01 |

| Average | 25.5 | 24.8 | 29.6 | |

| Good | 44.7 | 45.1 | 42.3 | |

| Excellent | 25.8 | 26.4 | 21.7 | |

| TV screen time per day (h), M (SD) | 1.92 (0.84) | 1.91 (0.89) | 1.92 (0.83) | .746 |

| Sensation seeking and rebelliousness, M (SD) | 0.81 (0.62) | 0.92 (0.70) | 0.79 (0.60) | <.001 |

| Exposure to alcohol use in movies, M (SD) | 3707 (2472) | 4037 (2590) | 3653 (2448) | .005 |

| Social Environment | ||||

| Peer drinking | ||||

| None | 71.3 | 63.3 | 72.7 | <.01 |

| A few | 17.9 | 22.4 | 17.1 | |

| Some | 8.5 | 11.9 | 7.9 | |

| Most or all | 2.3 | 2.4 | 2.3 | |

| Mother figure drinking | ||||

| Never | 37.0 | 39.3 | 36.6 | .682 |

| Seldom | 55.7 | 52.8 | 56.2 | |

| Often but not every day | 6.6 | 7.2 | 6.5 | |

| Every day | 0.7 | 0.8 | 0.7 | |

| Father figure drinking | ||||

| Never | 26.4 | 31.9 | 25.6 | <.05 |

| Seldom | 57.4 | 51.3 | 58.4 | |

| Often but not every day | 13.8 | 14.9 | 13.6 | |

| Every day | 2.4 | 1.9 | 2.5 | |

| Any sibling drinking | ||||

| No | 81.2 | 76.3 | 82.0 | <.01 |

| Yes | 18.8 | 23.7 | 18.0 | |

Drinking Initiation During the Observation Period

Overall, 40% of the nonsusceptible baseline never drinkers tried alcohol during the 12-months observation period, and about 6% initiated binge drinking (Table 3). Initiation rates varied between the 6 countries, with the lowest rates in Iceland and the highest in Germany and Poland. After Bonferroni adjustment, pairwise country comparisons for alcohol use initiation were significant for Iceland in comparison with all other countries. For binge drinking initiation there were additional differences between Germany versus Italy and Italy versus Poland. No significant difference was found for the rates of binge drinking in Dutch compared with the Icelandic sample.

TABLE 3.

Age- and Gender-Adjusted Incidence Rates (%) for Ever Alcohol Use (Even Just a Sip) and Binge Drinking During the 12-mo Study Period (n = 2326)

| Total | Germany (de) | Iceland (is) | Italy (it) | Netherlands (nl) | Poland (pl) | Scotland (uk) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alcohol use initiation | 40.3 | 46.7is | 29.6de,it,nl,pl,uk | 34.2is | 41.4is | 54.1is | 49.9is |

| Binge drinking initiation | 6.2 | 12.8is,it | 1.0de,it,pl,uk | 4.7de,is,pl | 3.0 | 11.4is,it | 6.2is |

Superscripts indicate significant between-country comparisons after Bonferroni correction.

Exposure to Alcohol Use in Movies

Overall, 86% of the total 655 movies included at least 1 alcohol scene, with a range of 0 to 617 and a mean of 68 (SD = 87) occurrences per movie. On average, participants in the analyzed sample had seen 18 (SD = 9) of the movies on their movie list, which translated to an estimated mean individual exposure to movie alcohol use of 3653 (median = 3233, SD = 2448) occurrences, with a range of 0 to 14 498 occurrences, based on the extrapolation to the respective 250 movies.

Association Between Exposure to Alcohol Use in Movies and Adolescent Drinking Initiation

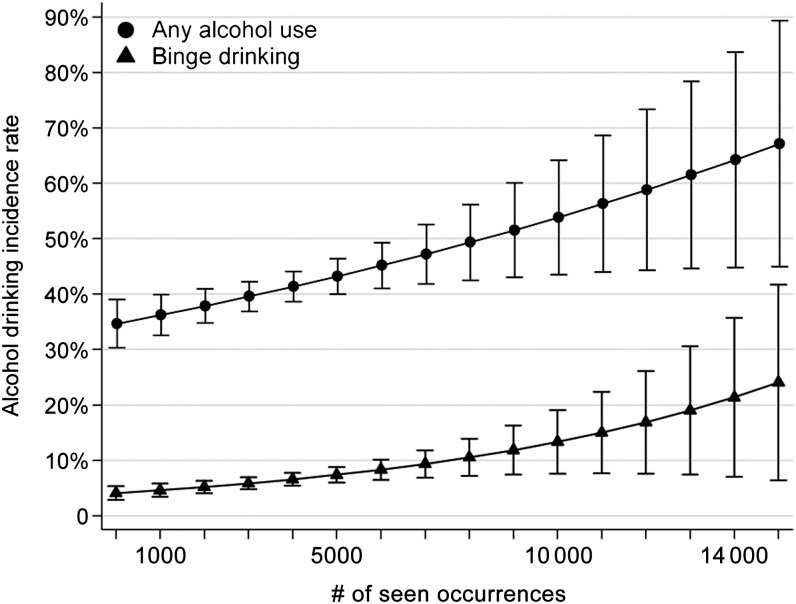

Figure 1 shows the adjusted association between the exposure to movie alcohol consumption and alcohol use initiation of nonsusceptible never drinkers at baseline. After age, gender, family affluence, school performance, TV screen time, personality characteristics, and drinking behaviors of peers, parents, and siblings were controlled for, exposure to movie alcohol use was significantly related to drinking initiation. The adjusted IRR for any alcohol use in the observation period was 1.05 (95% CI, 1.02–1.08; P = .003) for each additional 1000 occurrences of alcohol movie exposure. Figure 1 illustrates that going from lowest to highest exposure raised the incidence of alcohol onset by about 30 percentage points. For binge drinking the adjusted IRR was 1.13 (95% CI, 1.06–1.20; P < .001). Figure 1 illustrates that going from lowest to highest exposure raised the incidence of binge drinking by about 20 percentage points. For alcohol use initiation, the only other significant longitudinal associations were found for drinking of siblings (IRR = 1.25; 95% CI, 1.09–1.52; P = .003) and drinking frequency of the mother (IRR = 1.14; 95% CI, 1.01–1.29; P = .035). Binge drinking initiation was significantly related to school performance (IRR = 0.67; 95% CI, 0.55–0.84; P < .001), family affluence (IRR = 0.77; 95% CI, 0.60–0.99; P = .045), and sensation seeking (IRR = 1.48; 95% CI, 1.15–1.91; P = .003).

FIGURE 1.

Adjusted association between exposure to alcohol use occurrences in movies and adolescents’ drinking initiation. Note: Covariate adjustment for age, gender, family affluence, school performance, TV screen time, sensation seeking and rebelliousness, and alcohol consumption in the social environment (friends, siblings, and parents).

Sensitivity Analysis

None of the exposure × country interaction terms reached significance, indicating either that the reported associations did not differ between countries or that statistical power was not high enough to show such differences.

Discussion

This study demonstrates that movie alcohol exposure is associated with initiation of alcohol use and binge drinking among low-risk European adolescents, independent from other risk factors that model the social environment and personal characteristics. The range of exposure was substantial, such that high alcohol use in movies independently accounted for increases in the incidence of alcohol initiation by 30 percentage points and binge drinking by 20 percentage points.

There are at least 3 contributions of the current study. The first is the longitudinal design, which enables the investigation of the incidence of behavioral transitions, placing the exposure before these transitions. To date only 3 other cohorts have been followed up to explore the effects of exposure to movie depictions of alcohol, 2 from the United States and 1 from Germany. The second contribution is the large and diverse sample that was recruited in 6 European countries. These countries differ in respect of both macro-level contextual environmental factors (eg, alcohol control policies) and prevalence of alcohol use. An association that holds across this source of significant (unmeasured) variance is likely to be robust and extends beyond the multiple individual risk factors controlled for in this study. Third, for the first time we reported the effect of movie alcohol exposure on a subgroup of adolescents who have a very low affinity for alcohol (never users without intention to use alcohol). This limits the argument that seeing specific movies with alcohol is simply a byproduct of other unmeasured personal characteristics that are indicative of alcohol use.

There are limitations to the study, which must be taken into account. Loss to follow-up affects the generalizability of results, especially if there is selective attrition, which was the case in the current study: Adolescents at higher risk of drinking were more likely to be lost to follow-up. The fact that lost students had a higher exposure to alcohol depictions in movies might lead to an underestimation of the true association. Although we captured a large number of covariates and studied a very restricted sample, it is still possible that the results may be biased by unmeasured confounding on the individual level. Additional tests are needed to tap into unmeasured confounding on the side of the predictor. In addition, because alcohol use is often presented together with other adult movie contents such as violence, profanity, tobacco, and sex, the reported associations may not be specific, a feature one would expect if a risk factor is causal.

Implications for Prevention

This study provides evidence of a robust longitudinal association between seeing drinking scenes in movies and drinking initiation in a sample of low-risk early adolescents recruited in 6 European countries. Generally, prevention measures can be classified into structural and behavioral measures. One structural preventive measure applying this concept would be to incorporate movie alcohol use into the movie rating systems, which would lower the “dose” of exposure. Such a proposal is currently debated for on-screen smoking26 but should also be applied for alcohol use in movies. When it comes to more behavior-oriented preventive measures, health care practitioners, teachers, and other professionals could stress the importance of prudent media management for parents of young children. Parents might help prevent movies and other media from influencing their children’s susceptibility to alcohol use via two different methods27: First, they could reduce exposure to movies that show alcohol use. This could be done by reducing the overall movie and media use of children, which has also other health benefits.28 It has been shown that children who report less parental restrictions on watching movies designed for older adolescents have a higher risk of engaging in binge drinking.29 Second, parents could talk to their children regularly about what they are seeing or hearing in media related to alcohol use, or they could view movies together with their children. They can discuss false or misleading information from alcohol imagery on screen (in movies but also through alcohol advertisements). This strategy can be subsumed under the heading “media literacy education,” but this research field is just emerging.30

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the work of Stefan Hrafn Jonsson, Solveig Karlsdottir, Fabrizio Faggiano, and Evelien Poelen of the Smoking in Movies Europe study group. We thank Abita Bhaskar, Daria Buscemi, Lars Grabbe, Roberto Gullino, Leonie Hendriksen, Maksymilian Kulza, Martin Law, Dan Nassau, Balvinder Rakhra, Monika Senczuk-Przybylowska, and Tiziano Soldani for coding the movies. And we are also very thankful to all pupils and staff in participating schools and the survey field forces in each country.

Glossary

- CI

confidence interval

- IRR

incidence rate ratio

APPENDIX.

Study Sample Details

| Germany | Iceland | Italy | Poland | The Netherlands | Scotland | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Setting | Public schools, 4 school types: Gymnasium Gemeinschaftsschule, Regionalschule, Hauptschule | Public schools | Public schools, second class of secondary school and first class of high school | Public schools, 1 school type (Gymnasium) | Public schools, 4 different school types: VMBO, HAVO, Atheneum, Gymnasium | Mainstream (state-funded) schools |

| Locations | Schleswig-Holstein, Germany | Schools from each region (north, south, east, west) of Iceland in addition to the capital area (Reykjavík) | Piedmont region, Italy | Wielkopolska region | Gelderland, Limburg, Brabant | Central belt of Scotland |

| District of Kiel, Flensburg, Schleswig-Flensburg, and Rendsburg-Eckernförde | Schools with head office in Turin and Novara provinces | |||||

| Time of baseline assessment | November–December 2009 | January–February 2010 | March–June 2010 | April–June 2010 | December 2009–June 2010 | January–March 2010 |

| Time of follow-up assessment | February–March 2011 | January–February 2011 | March–May 2011 | January–April 2011 | February–May 2011 | January–February 2011 |

| Eligibility criteria for schools | Location | Number of participating pupils >100 | Location in Turin and Novara provinces | Location in Wielkopolska region | No special pedagogic education center | Location in either Midlothian or East Dumbartonshire |

| Number of classes >8 | No special pedagogic education center | No current participation in other studies of the BSI, Radboud University | No special education | |||

| No special pedagogic education center | No private education | |||||

| No other studies of IFT-Nord | ||||||

| No. of schools potentially eligible | 104 | Not known | 578 | 253 | Not known | 14 |

| No. of schools invited | 60 | 23 | 31 | 253 | 43 | 7 |

| Invitation criteria for schools | Random | Convenience sampling | Convenience sampling | All eligible schools | Random | Selected based on proportion of free school meals |

| No. of schools that agreed (baseline) | 21 | 20 | 26 | 35 | 5 | 7 |

| No. of schools that agreed (follow-up) | 21 | 20 | 26 | 33 | 5 | 7 |

| Eligibility criteria for pupils | Active (“opt-in”) parental consent | Passive (“opt-out”) parental consent | Active or passive parental consent | Active (“opt-in”) parental consent | Passive parental consent | Passive (“opt-out”) parental consent |

| Presence on the day of assessment or, if absent, willing to complete a questionnaire and return by post | Pupil’s presence on the day of assessment | Willingness to participate or, if absent, willing to complete a questionnaire and return by post | Presence on the day of assessment | Presence on the day of assessment | Presence on the day of assessment or, if absent, willing to complete a questionnaire and return by post | |

| Willing to participate | Willing to participate | Willing to participate | Willing to participate | Willing to participate | ||

| No. of pupils examined for eligibility | 3544 | 2798 | 2953 | 5078 | 1706 | 3189 |

| No. confirmed eligible | 2754 | 2664 | 2668 | 4105 | 1423 | 2937 |

| Reasons for nonparticipation | No parental consent (n = 515), absence (n = 264), refusal (n = 11) | No parental consent (n = 19), absence (n = 102), refusal (n = 13) | No parental consent (n = 100), absence (n = 175), refusal (n = 10) | No parental consent (n = 396), absence (n = 527), refusal (n = 50) | No parental consent (n = 18), absence (n = 265), refusal (n = 0) | No parental consent (n = 11), absence (n = 226), refusal (n = 15) |

| No. participating at baseline | 2754 | 2664 | 2668 | 4105 | 1423 | 2937 |

| No. analyzed at baseline | 2754 | 2664 | 2668 | 4105 | 1423 | 2937 |

| Response rate at baseline (%) | 78 | 95 | 90 | 81 | 83 | 92 |

| Mean age at baseline (y) | 12.7 | 13.1 | 13.6 | 14.2 | 13.8 | 13.0 |

| No. participated at follow-up | 2645 | 2594 | 2404 | 3698 | 1676 | 3012 |

| No. matched | 2336 | 2168 | 2272 | 3148 | 1215 | 2503 |

| Reasons for nonmatch | Absence at baseline | Absence at baseline | Absence at baseline | Absence at baseline | Absence at baseline | Absence at baseline |

| Absence at follow-up | Absence at follow-up | Absence at follow-up | Absence at follow-up | Absence at follow-up | Absence at follow-up | |

| Incorrect code | Incorrect code | Incorrect code | Incorrect code | Incorrect code | Incorrect code | |

| No. of baseline pupils lost to follow-up | 388 | 496 | 396 | 957 | 208 | 434 |

| Matching rate (%) | 84.8 | 81.4 | 85.2 | 76.7 | 84.4 | 80.0 |

BSI, Behavioral Science Institute.

Footnotes

Dr Hanewinkel designed the study, contributed to data acquisition in Germany, carried out the statistical analysis, and drafted the article; Dr Sargent designed the study, contributed to data acquisition (alcohol occurrences in movies), and revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content; Dr Hunt contributed to data acquisition in Scotland and revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content; Dr Sweeting contributed to data acquisition in Scotland and revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content; Dr Engels contributed to data acquisition in the Netherlands and revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content; Dr Scholte contributed to data acquisition in The Netherlands and revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content; Ms Mathis contributed to data acquisition in Italy and revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content; Dr Florek contributed to data acquisition in Poland and revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content; Dr Morgenstern designed the study, contributed to data acquisition in Germany, carried out the statistical analysis, and revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content; and all authors agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work were appropriately investigated and resolved and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE: The authors have indicated they have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

FUNDING: The study was supported by the European Commission and the Ministry of Health of the Federal Republic of Germany. The coding of the US movies was supported by the National Institutes of Health (AA015591/AA/NIAAA NIH HHS/United States). The Scottish fieldwork was supported by additional funds from the UK Medical Research Council (MC_US_A540_0041). Funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

POTENTIAL CONFLICT OF INTEREST: The authors have indicated they have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Chartier KG, Hesselbrock MN, Hesselbrock VM. Development and vulnerability factors in adolescent alcohol use. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2010;19(3):493–504 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bandura A. Social Foundations of Thought and Action: A Social Cognitive Theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall; 1986 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dalton MA, Bernhardt AM, Gibson JJ, et al. Use of cigarettes and alcohol by preschoolers while role-playing as adults: “Honey, have some smokes.” Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2005;159(9):854–859 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lyons A, McNeill A, Britton J. Alcohol imagery on popularly viewed television in the UK. J Public Health (Oxf). 2013; PMID: 23929886 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lyons A, McNeill A, Gilmore I, Britton J. Alcohol imagery and branding, and age classification of films popular in the UK. Int J Epidemiol. 2011;40(5):1411–1419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dal Cin S, Worth KA, Dalton MA, Sargent JD. Youth exposure to alcohol use and brand appearances in popular contemporary movies. Addiction. 2008;103(12):1925–1932 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Engels RC, Hermans R, van Baaren RB, Hollenstein T, Bot SM. Alcohol portrayal on television affects actual drinking behaviour. Alcohol Alcohol. 2009;44(3):244–249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Koordeman R, Anschutz DJ, van Baaren RB, Engels RC. Effects of alcohol portrayals in movies on actual alcohol consumption: an observational experimental study. Addiction. 2011;106(3):547–554 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Koordeman R, Kuntsche E, Anschutz DJ, van Baaren RB, Engels RC. Do we act upon what we see? Direct effects of alcohol cues in movies on young adults’ alcohol drinking. Alcohol Alcohol. 2011;46(4):393–398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hanewinkel R, Tanski SE, Sargent JD. Exposure to alcohol use in motion pictures and teen drinking in Germany. Int J Epidemiol. 2007;36(5):1068–1077 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hunt K, Sweeting H, Sargent J, Lewars H, Young R, West P. Is there an association between seeing incidents of alcohol or drug use in films and young Scottish adults’ own alcohol or drug use? A cross sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hanewinkel R, Sargent JD, Poelen EA, et al. Alcohol consumption in movies and adolescent binge drinking in 6 European countries. Pediatrics. 2012;129(4):709–720 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sargent JD, Wills TA, Stoolmiller M, Gibson J, Gibbons FX. Alcohol use in motion pictures and its relation with early-onset teen drinking. J Stud Alcohol. 2006;67(1):54–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.O’Hara RE, Gibbons FX, Li Z, Gerrard M, Sargent JD. Specificity of early movie effects on adolescent sexual behavior and alcohol use. Soc Sci Med. 2013;96:200–207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stoolmiller M, Wills TA, McClure AC, et al. Comparing media and family predictors of alcohol use: a cohort study of US adolescents. BMJ Open. 2012;2:e000543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wills TA, Sargent JD, Gibbons FX, Gerrard M, Stoolmiller M. Movie exposure to alcohol cues and adolescent alcohol problems: a longitudinal analysis in a national sample. Psychol Addict Behav. 2009;23(1):23–35 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dal Cin S, Worth KA, Gerrard M, et al. Watching and drinking: expectancies, prototypes, and friends’ alcohol use mediate the effect of exposure to alcohol use in movies on adolescent drinking. Health Psychol. 2009;28(4):473–483 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hanewinkel R, Sargent JD. Longitudinal study of exposure to entertainment media and alcohol use among German adolescents. Pediatrics. 2009;123(3):989–995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Morgenstern M, Poelen EAP, Scholte RH, et al. Smoking in movies and adolescent smoking: cross-cultural study in six European countries. Thorax. 2011;66(10):875–883 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Morgenstern M, Sargent JD, Engels RC, et al. Smoking in movies and adolescent smoking initiation: longitudinal study in six European countries. Am J Prev Med. 2013;44(4):339–344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brand DA, Saisana M, Rynn LA, Pennoni F, Lowenfels AB. Comparative analysis of alcohol control policies in 30 countries. PLoS Med. 2007;4(4):e151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hibell B, Guttormson U, Ahlström S, et al. The 2007 ESPAD Report: Substance Use Among Students in 35 European Countries. Stockholm, Sweden: The European School Survey Project on Alcohol and Other Drugs; 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Galanti MR, Siliquini R, Cuomo L, Melero JC, Panella M, Faggiano F, EU-DAP Study Group . Testing anonymous link procedures for follow-up of adolescents in a school-based trial: the EU-DAP pilot study. Prev Med. 2007;44(2):174–177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pierce JP, Choi WS, Gilpin EA, Farkas AJ, Merritt RK. Validation of susceptibility as a predictor of which adolescents take up smoking in the United States. Health Psychol. 1996;15(5):355–361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sargent JD, Worth KA, Beach M, Gerrard M, Heatherton TF. Population-based assessment of exposure to risk behaviors in motion pictures. Commun Methods Meas. 2008;2(1–2):134–151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lyons A, Britton J. Protecting young people from smoking imagery in films: whose responsibility? Thorax. 2011;66(10):844–846 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moreno MA, Furtner F, Rivara FP. Media influence on adolescent alcohol use. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2011;165(7):680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moreno MA, Furtner F, Rivara FP. Reducing screen time for children. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2011;165(11):1056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hanewinkel R, Morgenstern M, Tanski SE, Sargent JD. Longitudinal study of parental movie restriction on teen smoking and drinking in Germany. Addiction. 2008;103(10):1722–1730 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bergsma LJ, Carney ME. Effectiveness of health-promoting media literacy education: a systematic review. Health Educ Res. 2008;23(3):522–542 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]