Abstract

Introduction:

Interstitial pregnancy is a rare and life-threatening condition. Diagnosis and appropriate management are critical in preventing morbidity and death.

Case Description:

Four cases of interstitial pregnancy are presented. Diagnostic laparoscopy followed by laparotomy and cornuostomy with removal of products of conception was performed in 1 case. Laparoscopic cornuostomy and removal of products of conception were performed in the subsequent 3 cases with some modifications of the technique. Subsequent successful reproductive outcomes are also presented.

Discussion:

Progressively conservative surgical measures are being used to treat interstitial pregnancy successfully, with no negative impact on subsequent pregnancies.

Keywords: Cornuostomy, Interstitial ectopic, Laparoscopy

INTRODUCTION

Interstitial pregnancy is a rare and life-threatening condition. Implantations specifically occurring in the interstitial area account for 1% of all ectopic pregnancies after in vitro fertilization (IVF) and have been reported in 1% to 6% of all ectopic pregnancies otherwise.1–3 A distinction should be made from cornual pregnancy. By definition, a cornual pregnancy refers to the implantation and development of a gestational sac in one of the upper and lateral portions of the uterus. Conversely, an interstitial pregnancy is a gestational sac that implants within the proximal, intramural portion of the fallopian tube that is enveloped by the myometrium.4–7 The interstitial portion is approximately 0.7 mm in width and approximately 1 to 2 cm in length. The importance of diagnosing this condition correctly and as early as possible is related to the high mortality rate of 2% to 2.5%. The mortality rate for ectopic pregnancies overall is 0.14%.4

Common predisposing factors are previous ectopic pregnancy, previous ipsilateral salpingectomy, and IVF. Because of its unique location, interstitial pregnancy remains one of the most difficult ectopic pregnancies to diagnose.5 The following ultrasonographic criteria have been proposed for diagnosing such a condition: an empty uterine cavity, a gestational sac located eccentrically and >1 cm from the most lateral wall of the uterine cavity, and a thin (<5 mm) myometrial layer surrounding the gestational sac.8 The “interstitial line sign” that extends from the upper region of the uterine horn to border the intramural portion of the fallopian tube has also been used.9 Three-dimensional ultrasonography scans and magnetic resonance imaging allow for accurate early diagnosis of interstitial pregnancy if suspected on 2-dimensional ultrasonography scans.10,11 Traditionally, treatment of interstitial pregnancy has been surgical and may include hysterectomy or cornual resection by laparotomy or laparoscopy.1 There is no general agreement on the correct surgical technique. Increasingly more conservative approaches are being used such as cornuostomy instead of cornual resection, as well as laparoscopy in place of laparotomy. Many cases of laparoscopic cornuostomy have been described in the literature so far.12–18 An Endoloop (Ethicon Products, Livingston, UK) or encircling method to repair the cornuostomy incision after removal of products of conception has been described in 11 cases by Moon et al.18 After cornuostomy in general and laparoscopic cornuostomy in particular, subsequent pregnancy is of concern because of the weakening of the cornual area, leading to a predisposition for uterine rupture. Moon et al described a favorable reproductive outcome in 11 cases that were treated by laparoscopic cornuostomy and in which delivery by elective cesarean section was performed at term without any complications. Su et al17 reported a uterine rupture at the scar of a prior laparoscopic cornuostomy after vaginal delivery of a full-term healthy neonate.

On the basis of the available literature, more data are needed to determine the best technique of laparoscopic cornuostomy and its subsequent reproductive outcome. We report 4 cases of interstitial ectopic pregnancies managed with increasingly more conservative approaches of cornuostomy and their subsequent reproductive outcome.

CASE DESCRIPTION

Case 1

A 36-year-old woman presented with primary infertility of 2.5 years' duration. The underlying etiology included male factors and tubal factors with a history of Chlamydia infection in the past. She opted for IVF treatment with intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI). The first cycle resulted in a missed abortion. The patient underwent a suction dilatation and curettage. A subsequent cycle with intrauterine insemination after controlled ovarian stimulation resulted in no pregnancy. A second cycle of ICSI resulted in pregnancy. A transvaginal ultrasonography scan 25 days after embryo transfer showed implantation of the gestational sac to the extreme left lateral side of the upper segment of the uterus. A repeat scan 32 days after transfer confirmed the location of the sac to be within the proximal, intramural portion of the fallopian tube; it was enveloped by the myometrium and located eccentrically >1 cm from the most lateral wall of the endometrial cavity. The patient underwent diagnostic laparoscopy, which confirmed the diagnosis of interstitial ectopic pregnancy because the sac was located lateral to the insertion of the round ligament in the uterus. This was followed by laparotomy because the surgeon who performed the surgery felt more comfortable performing cornuostomy by laparotomy as opposed to operative laparoscopy. The uterus was injected with diluted vasopressin (20 U in 100 mL of normal saline solution), and the uterine bulge was incised with a monopolar electrosurgical device (30-W cutting current). The gestational sac was expressed, and the uterine incision was repaired with No. 2-0 Vicryl sutures (Ethicon, Somerville, New Jersey) in a figure-of-8 configuration. The pathology report confirmed products of conception. The patient underwent a third ICSI cycle, and she conceived. There were no complications during the pregnancy. She delivered a live female neonate weighing 5 lb 2 oz at 35 weeks 6 days by cesarean section.

Case 2

A 36-year-old patient, gravida 3, para 3, presented with a history of secondary infertility for 2.5 years' duration. She had 2 normal spontaneous vaginal deliveries and 1 premature delivery with a stillbirth. She conceived after IVF treatment. At 7 weeks' gestation, a transvaginal ultrasonography scan suggested an interstitial pregnancy (Figure 1). The patient had no symptoms except for sporadic vaginal bleeding. Laparoscopy showed a left interstitial ectopic pregnancy measuring approximately 2 to 3 cm in diameter. Diluted vasopressin (20 U in 100 mL of normal saline solution) was injected into the myometrium (Figure 2). Two stay sutures were placed. This was followed by a left linear cornuostomy. A laparoscopic spatula connected to monopolar cautery (30-W cutting current) was used to make an incision along the most bulging portion of the interstitial pregnancy. Hydrodissection was used to remove the gestational sac. Two mattress sutures (No. 2-0 Vicryl) were used to approximate the myometrium. Stay sutures were tied, and the cornuostomy site was reapproximated with No. 2-0 Vicryl in a continuous running manner. The pathology report confirmed products of conception.

Figure 1.

Transvaginal 2-dimensional ultrasonography scan in transverse view showing left interstitial ectopic pregnancy (arrow) in case 2.

Figure 2.

Laparoscopic view of left interstitial ectopic pregnancy after injection of diluted vasopressin in case 2.

The patient subsequently conceived spontaneously. As noted earlier, she had a history of preterm delivery, and during this pregnancy, she presented with spontaneous rupture of membranes at 28 weeks, with fetal breech presentation. She was delivered at this time by a classical cesarean section with no adverse neonatal outcomes.

Case 3

A 30-year-old patient, gravida 1, para 0, with a history of secondary infertility for 1 year's duration due to tubal factors, presented for IVF treatment at our unit. She had a history of right salpingectomy for a previous ruptured ectopic pregnancy and a history of pelvic inflammatory disease resulting in extensive pelvic adhesions and damage to the left fallopian tube. She conceived during her second cycle of IVF treatment. A transvaginal ultrasonography scan showed 3 possibly nonviable gestational sacs at 6 weeks' gestation. A subsequent ultrasonography scan at 8 weeks' gestation showed a possible right interstitial ectopic pregnancy along with 2 collapsed intrauterine sacs. The patient was strongly advised to undergo a diagnostic laparoscopy to confirm the diagnosis and to correct it surgically; however, she refused. At 10 weeks' gestation, she had a repeat ultrasonography scan confirming the diagnosis and consented to undergo surgery. Diagnostic laparoscopy showed a large right interstitial ectopic pregnancy (Figure 3). Laparoscopic cornuostomy was performed. Initially, diluted vasopressin (20 U in 100 mL of normal saline solution) was injected into the myometrium for vasoconstriction. A 2-cm transverse incision was made in the seromuscular layer of the fundal region over the ectopic mass by use of a monopolar spatula (cutting current of 30 W). The gestational sac was visualized, and the incision was extended to allow its delivery, by use of the technique of hydrodissection with gentle traction on the tissue with a toothed forceps and countertraction on the myometrial tissue with atraumatic forceps. The placental tissue was removed in a piecemeal fashion. Laparoscopic scissors were used to trim the edges of the cornuostomy incision. An argon beam coagulator at a 4-L flow rate and 40-W current (Birtcher Medical Systems, Irvine, California) was used to secure homeostasis in the myometrial bed. The edges of the myometrial bed were approximated by a 2–mattress suture technique followed by a continuous running suture (No. 2-0 Vicryl). Homeostasis was secured, and the procedure was terminated.

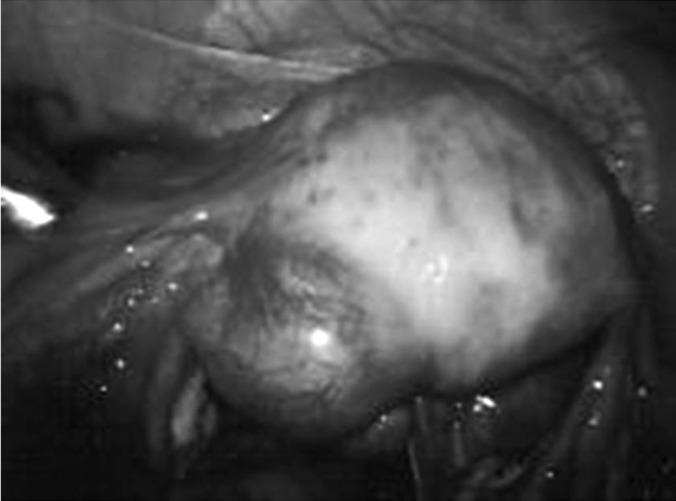

Figure 3.

Laparoscopic view of large right interstitial ectopic pregnancy in case 3.

The patient had an uneventful recovery and was discharged home on the same day. Repeated β human chorionic gonadotropin (β-hCG) values showed a gradual decrease to normal nonpregnant levels. Subsequently, the patient underwent another cycle of IVF treatment, resulting in a twin pregnancy; the neonates were delivered by cesarean section at 36 weeks' gestation.

Case 4

A 30-year-old woman, gravida 1, para 0, with a known incomplete uterine septum was referred to our unit for persistent elevation of β-hCG levels. Twelve weeks earlier, she was assumed to have had a complete miscarriage at 7 weeks' gestation. She presented at that time with bleeding and passage of a large amount of tissue. Follow-up by serial β-hCG measurement showed an initial drop; however, the levels failed to reach zero. The β-hCG level detected 3 months after miscarriage was found to be 29 mIU/mL. A transvaginal ultrasonography scan showed a possible missed abortion with a large gestational sac and yolk sac confined to the right side. One area of concern on ultrasonography was a very thin myometrium at the fundal region. Therefore the possibility of cornual versus interstitial ectopic pregnancy was entertained (Figure 4). A diagnostic laparoscopy was performed and showed a large right interstitial ectopic pregnancy (Figure 5). In a similar manner as described in case 3, laparoscopic cornuostomy with removal of the gestational sac, followed by laparoscopic repair of the cornuostomy incision, was performed (Figure 6). A subsequent hysterosalpingogram (HSG) confirmed a T-shaped appearance of the uterus, a patent left tube, and blockage of the right tube at the interstitial portion. The patient tried to conceive on her own starting 4 months after her surgery. She conceived in the second cycle and delivered by cesarean section at 38 weeks' gestation.

Figure 4.

Transvaginal 2-dimensional ultrasonography scan in transverse view showing a very thin myometrium at the fundal region to the right side (arrow), raising the possibility of a cornual versus interstitial ectopic pregnancy in case 4.

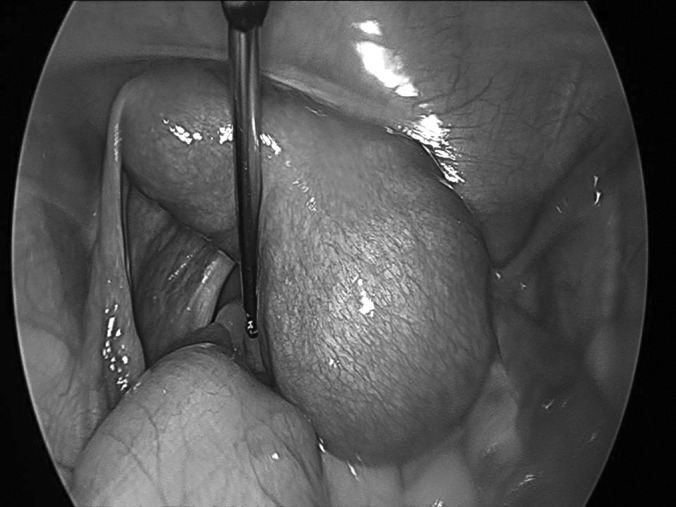

Figure 5.

Laparoscopic picture of large right interstitial ectopic pregnancy in case 4.

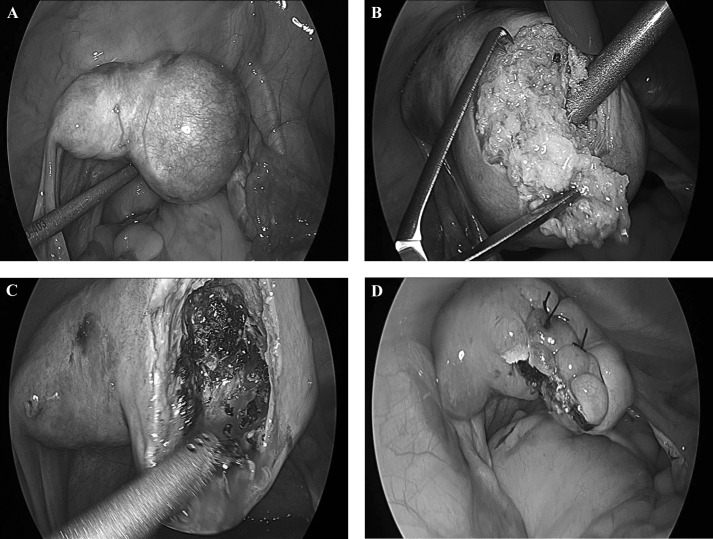

Figure 6.

Laparoscopic pictures showing steps of laparoscopic cornuostomy of large right interstitial ectopic pregnancy in case 4. (A) Appearance of myometrium (blanched) and right interstitial ectopic pregnancy after diluted vasopressin injection. (B) Removal of placenta tissue using technique of hydrodissection with gentle traction on tissue with toothed forceps and countertraction on myometrial tissue with atraumatic forceps. The placental tissue was removed in a piecemeal fashion. (C) Good hemostasis of cornuostomy bed. (D) Image obtained after repair of the cornuostomy incision with a few mattress sutures (No. 2-0 Vicryl) and a baseball running suture for the edges (No. 3-0 V-lock suture Covidien, Mansfield, MA).

DISCUSSION

The traditional treatment of interstitial pregnancy has been cornual resection or hysterectomy in cases with severely damaged uteri.19 Ruptured interstitial pregnancy may present with hypovolemic shock, necessitating emergency laparotomy and cornual resection or hysterectomy.20 However, in patients who are hemodynamically stable, conservative measures may be attempted, including laparoscopy or medical management.21 There are case reports of successful laparoscopic resection of cornual pregnancies.17,22,23 Laparoscopic resection may be assisted by direct injection of vasoconstrictive agents such as diluted vasopressin.4,17 In a report by Tulandi and Al-Jaroudi,24 the management of 32 cases of interstitial pregnancy was discussed. Eight women were treated with methotrexate either systemically (n=4), locally under ultrasonographic guidance (n=2), or under laparoscopic guidance (n=2). Eleven patients were treated by laparoscopy and 13 by laparotomy. Systemic methotrexate treatment failed in 3 patients, and they subsequently required surgery. Persistently elevated serum β-hCG levels were found in 1 patient after laparoscopic cornual excision, and she was successfully treated with methotrexate. Subsequent pregnancy was achieved in 10 patients. No uterine rupture was encountered during pregnancy or labor.24

There is no general consensus on the best surgical procedure for interstitial ectopic pregnancy. Increasingly more conservative approaches are being used, such as cornuostomy instead of cornual resection, as well as laparoscopy in place of laparotomy. Several cases of laparoscopic cornuostomy have been described in the literature so far.12–18 Many techniques have been described to reduce blood loss during cornual resection or cornuostomy. Moon et al18 described using Endoloop in 15 patients or an encircling method in 3 patients before the cornuostomy incision for removal of products of conception. They concluded that these methods are simple, safe, effective, and nearly bloodless. Other authors described direct injection of diluted vasopressin in the myometrium near the interstitial ectopic pregnancy as an alternative technique to control blood loss during cornuostomy.4,18

In our 4-case series, we wish to emphasize the evolution and the effectiveness of conservative management in the treatment of interstitial ectopic pregnancy and to describe the subsequent reproductive outcome. In the first case the patient underwent diagnostic laparoscopy followed by laparotomy and cornuostomy. In the second case we tried a more conservative approach to manage the interstitial ectopic pregnancy laparoscopically. Diluted vasopressin was injected into the myometrium. Two stay sutures were placed, followed by a left linear cornuostomy and removal of the ectopic gestational sac. We observed that there was no need for the stay sutures because there was no bleeding after vasoconstriction was achieved with diluted vasopressin. In the third and fourth cases a further modification of our laparoscopic technique was implemented, in which diluted vasopressin was injected into the myometrium for vasoconstriction and no stay sutures were used. In our series 3 cases of large interstitial pregnancy were managed conservatively by laparoscopic cornuostomy.

Future fertility is possible in patients with a history of interstitial pregnancy. There is a concern regarding uterine rupture because of the weakened myometrial scar. This concern exists for both interstitial pregnancies treated surgically and those treated with chemotherapeutic measures.24 Uterine rupture at the site of prior laparoscopic cornuostomy after vaginal delivery of a full-term healthy neonate has been reported.17 We describe reproductive outcomes in 4 patients who underwent cornuostomy for interstitial ectopic pregnancy. All patients delivered by cesarean section without any evidence of dehiscence in the cornuostomy scar. Similarly, Moon et al18 reported on 11 patients who were delivered at term by elective cesarean section without any complications after laparoscopic cornuostomy. On the basis of the limited data in the literature, consideration should be given to cesarean section delivery after laparoscopic cornuostomy.

Medical treatment with methotrexate has been associated with a failure rate ranging from 9% to 65%.4,22,24,25 The best medical treatment regimen for interstitial pregnancy remains unknown.24

There are reports of other novel attempts of conservative management of interstitial ectopic pregnancy. In a case of an interstitial pregnancy at 12 weeks' gestation for which systemic methotrexate failed, Chen et al26 reported success with an intra-amniotic injection of etoposide, a topoisomerase II inhibitor used in the treatment of gestational trophoblastic disease and other gynecologic cancers, including germ cell tumor. Similarly, there is a report of an interstitial pregnancy for which a 2-dose protocol of systemic methotrexate failed and that was treated successfully with selective uterine artery embolization.28

In addition, Katz et al19 (in 2 patients) and Meyer and Mitchell28 (in 1 patient) reported successful hysteroscopy-guided evacuation of interstitial pregnancies under laparoscopic visualization and ultrasonographic guidance, respectively. Zhang et al29 have also reported 3 cases of large interstitial pregnancies that were successfully treated with transcervical curettage under laparoscopic guidance. Diagnostic hysteroscopy was performed in all 3 patients before proceeding with transcervical curettage under laparoscopic guidance. These authors stressed that such procedures can only be performed when the interstitial ectopic pregnancy is situated in the proximal portion of the interstitium, preferably with a dilated proximal tubal ostium in a patient who is hemodynamically stable, by a very experienced endoscopic surgeon.19,28,29

Laparoscopic cornuostomy after local injection of diluted Pitressin appears to be a safe and effective treatment modality for interstitial ectopic pregnancy. This conservative surgical measure appears to have no negative impact on the outcome of subsequent pregnancies.

Contributor Information

Hussein Warda, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Hurley Medical Center, Flint, MI, USA..

Mamta M. Mamik, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Mount Sinai School of Medicine, New York, NY, USA..

Mohammad Ashraf, Division of Reproductive Endocrinology and Infertility, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Hurley Medical Center, Flint, MI, USA.; IVF Michigan, PC, Rochester Hills, MI, USA.

Mostafa I. Abuzeid, Division of Reproductive Endocrinology and Infertility, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Hurley Medical Center, Flint, MI, USA.; IVF Michigan, PC, Rochester Hills, MI, USA.

References:

- 1. Rock JA, Thompson JD, eds. Telinde's Operative Gynecology. 8th ed Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven; 1997:505–520 [Google Scholar]

- 2. Fernandez H, De Zeigler D, Bourget P, Feltain P, Frydman R. The place of methotrexate in the management of interstitial pregnancy. Hum Reprod. 1991;6:302–306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bouyer J, Coste H, Fernandez H, Pouly JL, Job-Spira N. Sites of ectopic pregnancy: a 10 year population-based study of 1800 cases. Hum Reprod. 2002;17(12):3224–3230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lau S, Tulandi T. Conservative medical and surgical management of interstitial ectopic pregnancy. Fertil Steril. 1999;72:207–215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Malinowski A, Bates SK. Semantics and pitfalls in the diagnosis of cornual/interstitial pregnancy. Fertil Steril. 2006;86(6):1764.e11–1764.e14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. de Boer CN, van Dongen PWJ, Willemsen WNP, Klapwijk CWDA. Ultrasound diagnosis of interstitial pregnancy. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1992;47:164–166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kun W, Tung W. On the lookout for rarity—interstitial/cornual pregnancy. Emerg Med J. 2001;8:147–150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Timor-Tritsch IE, Monteagudo A, Materna C, Veit CR. Sonographic evolution of cornual pregnancies treated without surgery. Obstet Gynecol. 1992;79:1044–1049 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ackerman TE, Levi CS, Dashefsky SM, Holt SC, Lindsay DJ. Interstitial line: sonographic finding in interstitial ectopic pregnancy. Radiology. 1993;189:83–87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Filhastre M, Dechaud H, Lesnik A, Taourel P. Interstitial pregnancy: role of MRI. Eur Radiol. 2005;15(1):93–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Araujo Junior E, Zanforlin Filho SM, Pires CR, et al. Three-dimensional transvaginal sonographic diagnosis of early and asymptomatic interstitial pregnancy. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2007;275(3):207–210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Katz Z, Lurie S. Laparoscopic cornuostomy in the treatment of interstitial pregnancy with subsequent hysterosalpingography. Br J Obstet Gynecol. 1997;104:955–956 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Matsuzaki S, Fukaya T, Murakami T, Yajima A. Laparoscopic cornuostomy for interstitial pregnancy. A case report. J Reprod Med. 1999;44(11):981–982 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Sagiv R, Golan A, Arbel-Alon S, Glezerman M. Three conservative approaches to treatment of interstitial pregnancy. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 2001;8(1):154–158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Pasic RP, Hammons G, Gardner JS, Hainer M. Laparoscopic treatment of cornual heterotopic pregnancy. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 2002;9(3):372–375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Chan LY, Yuen PM. Successful treatment of ruptured interstitial pregnancy with laparoscopic surgery. A report of 2 cases. J Reprod Med. 2003;48(7):569–571 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Su CF, Tsai HJ, Chen GD, Shih YT, Lee MS. Uterine rupture at scar of prior laparoscopic cornuostomy after vaginal delivery of a full-term healthy infant. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2008;34(4 Pt 2):688–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Moon HS, Choi YJ, Park YH, Kim SG. New simple endoscopic operations for interstitial pregnancies. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;182:114–121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Katz DL, Barrett JP, Sanfilippo JS, Badway DM. Combined hysteroscopy and laparoscopy in the treatment of interstitial pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;188:1113–1114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Brewer H, Gefroh S, Bork M, Munkarah A, Hawkins R, Redman M. Asymptomatic rupture of a cornual ectopic in the third trimester. J Reprod Med. 2005;50(9):715–718 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bernstein HB, Thrall MM, Clark WB. Expectant management of intramural ectopic pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2001;97:826–827 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Tulandi T, Vilos G, Gomel V. Laparoscopic treatment of interstitial pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 1995;85(3):465–467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Grobman WA, Milad MP. Conservative management of a large cornual ectopic pregnancy. Hum Reprod. 1998;13(7):2002–2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Tulandi T, Al-Jaroudi D. Interstitial pregnancy: results generated from the Society of Reproductive Surgeons' Registry. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;103(1):47–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Tawfiq A, Agameya AF, Claman P. Predictors of treatment failure for ectopic pregnancy treated with single dose methotrexate. Fertil Steril. 2000;74:877–880 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Chen CL, Wang PH, Chiu LM, Yang ML, Hung JH. Successful conservative treatment for advanced interstitial pregnancy. J Reprod Med. 2002;47(5):424–426 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Deruelle P, Lucot E, Lions C, Yann R. Management of interstitial pregnancy using selective uterine artery embolization. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;106(5):1165–1167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Meyer WR, Mitchell D. Hysteroscopic removal of an interstitial ectopic gestation. A case report. J Reprod Med. 1989;34:928–929 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Zhang X, Xinchang L, Fan H. Interstitial pregnancy and transcervical curettage. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;104(5):1193–1195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]