Abstract

OBJECTIVES

To modify the Prostate Cancer Prevention Trial Risk Calculator (PCPTRC) to predict low- versus high-grade (Gleason grade ≥ 7) prostate cancer and incorporate percent free PSA.

METHODS

Data from 6664 PCPT placebo arm biopsies [5826 individuals] where prostate-specific antigen (PSA) and digital rectal examination (DRE) results were available within one year prior to the biopsy and PSA was ≤ 10 ng/mL were used to develop a nominal logistic regression model to predict the risk of no versus low-grade (Gleason grade < 7) versus high-grade (Gleason grade ≥ 7) cancer. Percent free PSA was incorporated into the model based on likelihood ratio (LR) analysis of a San Antonio Biomarkers of Risk cohort. Models were externally validated on ten Prostate Biopsy Collaborative Group cohorts and one Early Detection Research Network (EDRN) reference set.

RESULTS

5468 (82.1%) of the PCPT biopsies were negative for prostate cancer, 942 (14.1%) detected low-grade and 254 (3.8%) high-grade disease. Significant predictors were (log-base-2) PSA (OR for low-grade versus no cancer: 1.29*, high-grade versus no cancer: 2.02*, high-grade versus low-grade cancer: 1.57*), DRE (0.96, 1.49*, 1.55*, respectively), age (1.02*, 1.05*, 1.03*), African American race (1.13, 2.83*, 2.51*), prior biopsy (0.63*, 0.81, 1.27), and family history (1.31*, 1.25, 0.95), where * indicates p-value < 0.05. The new PCPTRC 2.0 either with or without percent free PSA (also significant by the LR method) validated well externally.

CONCLUSIONS

By differentiating risk of low- versus high-grade disease on biopsy, PCPTRC 2.0 better enables physician-patient counseling concerning whether to proceed to biopsy.

Keywords: Low-grade prostate Cancer, High-grade prostate Cancer, Prostate-specific Antigen, Percent free PSA, Prostate Cancer Prevention Trial, Risk prediction

INTRODUCTION

While the early detection and immediate treatment of high-grade disease remains the primary goal in the fight against prostate cancer, the very high rates of disease-specific survival in patients on active surveillance, the NCCN recommended option for patients diagnosed with low-grade prostate cancer, has called into question whether a diagnosis of low-grade cancer is a benefit or a harm.1,2,3 The practical problem translates to the physician-patient dilemma as to whether to proceed to biopsy in the first place. In order to make an informed decision, it is required that the risk of low- versus high-grade prostate cancer be assessed as accurately as possible based on the most useful clinical parameters, including serum prostate-specific antigen (PSA) and percent free PSA.

In 2006, we developed the online Prostate Cancer Prevention Trial (PCPT) Risk Calculator (PCPTRC) to facilitate the decision to biopsy based on quantitative assessment of risk based on the clinical risk factors PSA, digital rectal exam (DRE), age, African American race, prostate cancer family and prior biopsy history.4 Based on 5519 biopsies from the PCPT placebo arm, many performed as part of a required end-of-study biopsy regardless of PSA value, the PCPTRC aimed to be the most accurate predictor of outcome on prostate biopsy. Later, as new biomarkers, such as percent free PSA, were multiply validated and their independent contribution to the PCPTRC risk factors quantified, we modified the PCPTRC to allow their incorporation.5,6 These markers were not measured on the original PCPT participants but rather assessed in external case control studies. They were incorporated into the PCPTRC by a statistical technique that adjusted PCPTRC risks by likelihood ratios of the markers in the external studies to arrive at updated PCPTRC risks.7

Now, eight years since the PCPTRC first appeared, the purpose of this study is to develop PCPTRC 2.0 in order to most accurately predict the risk of the three biopsy outcomes (negative, low-grade, and high-grade cancer) of contemporary clinical relevance. Data from over 1000 biopsies from the PCPT placebo arm are added to the original 5519 biopsies behind the original PCPTRC in order to gain statistical power in prediction of three outcomes rather than two (cancer versus no cancer) and the previously reported San Antonio Biomarkers of Risk (SABOR) case:control study for percent free PSA is expanded by 63 patients for the same purpose.6 The updated PCPTRC 2.0 is externally validated on ten international biopsy cohorts comprising the Prostate Biopsy Collaborative Group (PBCG) and an Early Detection Research Network (EDRN) reference biopsy set.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Prostate Cancer Prevention Trial (PCPT) participants used to develop PCPTRC 2.0

The PCPT enrolled healthy men over the age of 55 years with a PSA ≤ 3 ng/mL and a normal DRE to participate in a 7-year double blind randomized trial to assess the effectiveness of finasteride in prostate cancer prevention.7 Participants were to be annually screened with PSA and DRE, and interim biopsies during the trial were to be prompted for PSA > 4 ng/mL and/or an abnormal DRE. At the end of 7 years of follow-up an end-of-study biopsy was requested for all participants regardless of PSA, DRE or whether a prior biopsy had been performed during the study. All PCPT participants provided written informed consent and study procedures were approved by local institutional review boards for each participating study site. Only placebo arm biopsies where PSA and DRE results were available within one year prior to the biopsy and PSA was ≤ 10 ng/mL, were included. In addition, first degree family history of prostate cancer, history of a prior negative biopsy and race (African American versus not) were required for inclusion.

San Antonio Biomarkers of Risk (SABOR) participants used to incorporate percent free PSA into PCTPRC 2.0

SABOR is a Clinical and Epidemiologic Center of the EDRN of the National Cancer Institute. SABOR comprises a 3,930-member multi-ethnic, multi-racial cohort recruited from San Antonio and South Texas from 2000 to 2013 with up to 13 years of follow-up. Subjects are followed approximately annually with PSA and DRE. From this cohort, serum measured within 2.5 years prior to diagnosis for prostate cancer cases and at the study entry visit for either men with a confirmed negative biopsy or not diagnosed with prostate cancer at least five years out (controls). All SABOR participants provided written informed consent and study procedures were approved by the local institutional review board. The cohort used in this studied was an expansion (63 patients) to that previously used to update the original PCPTRC for percent free PSA restricted to participants with PSA < 50 ng/mL.6,8

Prostate Biopsy Collaborative Group (PBCG) to validate the PCPTRC 2.0 without percent free PSA

The PBCG comprises information on pre-biopsy characteristics and biopsy outcomes from 25,772 biopsies (8,503 cancers) from 10 international biopsy cohorts; it has been extensively characterized.9,10 Five cohorts come from countries participating in the European Randomized Study of Prostate Cancer (ERSPC) and represent annual screening of a healthy population similar to the PCPT (Goeteborg Round 1 [n=738], Goeteborg Rounds 2–6 [2–6], Rotterdam Round 1 [2884], Rotterdam Rounds 2–3 [1494], Tarn [293]). The screening cohorts are from the US SABOR [388], the UK PROstate TEsting for Cancer and Treatment (ProtecT) [7302], and European Tyrol [5441] studies. Two cohorts were from US tertiary referral centers at the Cleveland Clinic [3293] and Durham VA [2375]. For ease of presenting results, these cohorts will be referred to as PBCG cohorts 1 – 10 in the order appearing here.

Early Detection Research Network (EDRN) reference set to validate the PCPTRC 2.0 with percent free PSA

The EDRN reference set included biopsies from patients referred to Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, the University of Michigan, and the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio for suspicion of prostate cancer, generally based on PSA or DRE findings; it has been characterized in prior publications.8,11

Statistical methods

In the PCPT, SABOR and EDRN cohorts, patient characteristics of the three outcome groups (no cancer, low-and high-grade cancer) were compared using chi-square and Wilcoxon tests as appropriate.

Nominal logistic regression was used to form the PCPTRC 2.0 model on PCPT cohort to predict the likelihood of three outcomes: no cancer, low-grade (Gleason grade < 7) cancer and high-grade (Gleason grade ≥ 7) cancer on the basis of the risk factors: PSA, DRE, African American race, age, a prior negative biopsy and first-degree family history of prostate cancer. For multivariable modeling, PSA was log-base-2-transformed so that the resulting odds ratio would be interpretable as the change in odds of outcome for a two-fold increase in PSA. All possible combinations of risk factors were considered with the optimal model selected using the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC). The BIC also indicated the nominal logistic model as having superior fit to proportional odds regression. For construction of the original PCPTRC, only one biopsy per participant (the last biopsy on study) was used. For this analysis, all biopsies, including interim biopsies that were negative for prostate cancer, were included, resulting in an increased sample size. Because a prior negative biopsy was included as a covariate in the risk calculator, the dependence between a biopsy outcome and prior outcomes for the same individual was accounted for in the regression. Odds ratio estimates based the original PCPTRC biopsy samples were similar to those obtained here, while overall cancer rates were lower due to enrichment with more negative biopsies; this resulted in improved calibration to external data sets (data not shown).

Likelihood ratios comparing the conditional distributions of percent free PSA on the PCPT risk factors in the SABOR cohort were computed as previously described.5,8 Normal linear regression of log-base-2-transformed percent free PSA on the PCPT risk factors was performed separately in the three outcome groups in SABOR. PSA was also transformed to the log-base-2 scale in these regressions. The likelihood ratios formed from SABOR were multiplied by the prior odds of each cancer outcome (low- versus high-grade cancer compared to no cancer, respectively) provided by PCPTRC 2.0 to provide updated risks that depended on percent free PSA in addition to the risk factors included in PCPTRC 2.0.

External validation of PCPTRC 2.0 without incorporation of percent free PSA was assessed for each of the PBCG cohorts by area-underneath-the-receiver-operating-characteristic-curves (AUCs) for distinguishing any two categories of outcome (no versus low-grade cancer, no versus high-grade cancer, and low- versus high-grade cancer). External validation with percent free PSA was similarly assessed on the EDRN cohort. PCPTRC 2.0 risks with and without incorporation of percent free PSA were compared by scatterplots. Comparisons of the AUCS of PCPTRC 2.0 to PSA or between PCPTRC 2.0 with and without incorporation of percent free PSA were performed using nonparametric tests. Statistical significance for all tests was determined at the two-sided .05 level.

RESULTS

PCPTRC 2.0

Of the 6664 PCPT placebo arm biopsies included, 5468 (82.1%) were negative for prostate cancer, 942 (14.1%) indicated low-grade and 254 (3.8%) high-grade disease. There were statistically significant differences between the three groups in all characteristics shown in Table 1 (all p < 0.05). Risk of high-grade disease was associated with older age, African American race, having had at least one prior biopsy in the past, abnormal DRE, a positive family history of prostate cancer, and higher PSA level. The average PSA increased from 1.7, 2.1 to 3.1 ng/mL among non-cancers, low-grade and high-grade cases, respectively. The risk of low-grade prostate cancer oscillated between 10 and 17% at all PSA levels except for the range between 4 and 6 ng/mL, where it jumped to 20% (Table 1). Alternatively the risk of high-grade prostate cancer nearly steadily increased from 1.7% for PSA values less than 0.9 ng/mL to 15% for PSA levels above 6 ng/mL.

Table 1.

Characteristics of PCPT patients at time of biopsy (n, %); all p-values for comparison of the three groups were less than 0.05.

| No Cancer n = 5468 (80.1%) |

Low-grade cancer n = 942 (14.1%) |

High-grade cancer n = 254 (3.8%) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at biopsy | |||

| 55 to 59 | 105 (87.5) | 14 (11.7) | 1 (0.8) |

| 60 to 69 | 2930 (83.2) | 471 (13.4) | 121 (3.4) |

| 70 to 79 | 2208 (80.8) | 410 (15.0) | 114 (4.2) |

| 80 to 91 | 225 (77.6) | 47 (16.2) | 18 (6.2) |

| Race | |||

| White | 5221 (82.1) | 908 (14.3) | 232 (3.6) |

| African American | 167 (76.3) | 32 (14.6) | 20 (9.1) |

| Other | 80 (95.2) | 2 (2.4) | 2 (2.4) |

| Prior biopsy | |||

| Never | 4706 (81.7) | 842 (14.6) | 212 (3.7) |

| At least one | 762 (84.3) | 100 (11.1) | 42 (4.6) |

| Digital rectal exam | |||

| Normal | 4644 (82.3) | 804 (14.2) | 199 (3.5) |

| Abnormal | 824 (81.0) | 138 (13.6) | 55 (5.4) |

| Family history | |||

| No | 4605 (82.8) | 753 (13.5) | 204 (3.7) |

| Yes | 863 (78.3) | 189 (17.2) | 50 (4.5) |

| PSA (ng/ml) | |||

| ≤ 0.9 | 2234 (88.2) | 255 (10.1) | 43 (1.7) |

| 1.0 to 1.9 | 1736 (80.2) | 369 (17.1) | 58 (2.7) |

| 2.0 to 2.9 | 684 (81.6) | 116 (13.8) | 39 (4.6) |

| 3.0 to 3.9 | 156 (76.5) | 29 (14.2) | 19 (9.3) |

| 4.0 to 4.9 | 355 (71.0) | 106 (21.2) | 39 (7.8) |

| 5.0 to 5.9 | 157 (68.0) | 44 (19.0) | 30 (13.0) |

| 6.0 to 6.9 | 65 (74.8) | 9 (10.3) | 13 (15.0) |

| 7.0 to 10.0 | 81 (75.0) | 14 (13.0) | 13 (12.0) |

| Biopsy reason | |||

| End-of-study | 3942 (84.2) | 628 (13.4) | 114 (2.4) |

| Interim (or for-cause) | 1526 (77.0) | 314 (15.9) | 140 (7.1) |

The optimal prediction model contained the predictors PSA, DRE, age, African American race, prior biopsy, and family history (Table 2). Separating overall cancer prediction into its low- and high-grade components revealed that prior biopsy and family history were statistically significant only for low-grade and not for high-grade detection, DRE and African American race only for high-grade and not low-grade detection, and PSA and age for both.

Table 2.

Estimated odds ratios for PCPTRC 2.0.

| Predictor | Odds ratio | 95% Confidence interval |

p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low-grade versus no cancer | |||

| PSA (log base 2) | 1.29 | 1.22 to 1.37 | < 0.0001 |

| DRE | 0.96 | 0.79 to 1.17 | 0.70 |

| Age | 1.02 | 1.00 to 1.03 | 0.01 |

| African American | 1.13 | 0.77 to 1.67 | 0.54 |

| Prior biopsy | 0.63 | 0.51 to 0.79 | < 0.0001 |

| Family history | 1.31 | 1.10 to 1.57 | 0.003 |

| High-grade versus no cancer | |||

| PSA (log base 2) | 2.02 | 1.80 to 2.27 | < 0.0001 |

| DRE | 1.49 | 1.09 to 2.05 | 0.01 |

| Age | 1.05 | 1.03 to 1.07 | < 0.0001 |

| African American | 2.83 | 1.71 to 4.68 | < 0.0001 |

| Prior biopsy | 0.81 | 0.57 to 1.15 | 0.23 |

| Family history | 1.25 | 0.91 to 1.73 | 0.17 |

| High-grade versus low-grade cancer | |||

| PSA (log base 2) | 1.57 | 1.38 to 1.77 | < 0.0001 |

| DRE | 1.55 | 1.09 to 2.21 | 0.01 |

| Age | 1.03 | 1.01 to 1.06 | 0.01 |

| African American | 2.51 | 1.39 to 4.52 | 0.002 |

| Prior biopsy | 1.27 | 0.85 to 1.90 | 0.24 |

| Family history | 0.95 | 0.67 to 1.36 | 0.79 |

Incorporation of percent free PSA into PCPTRC 2.0

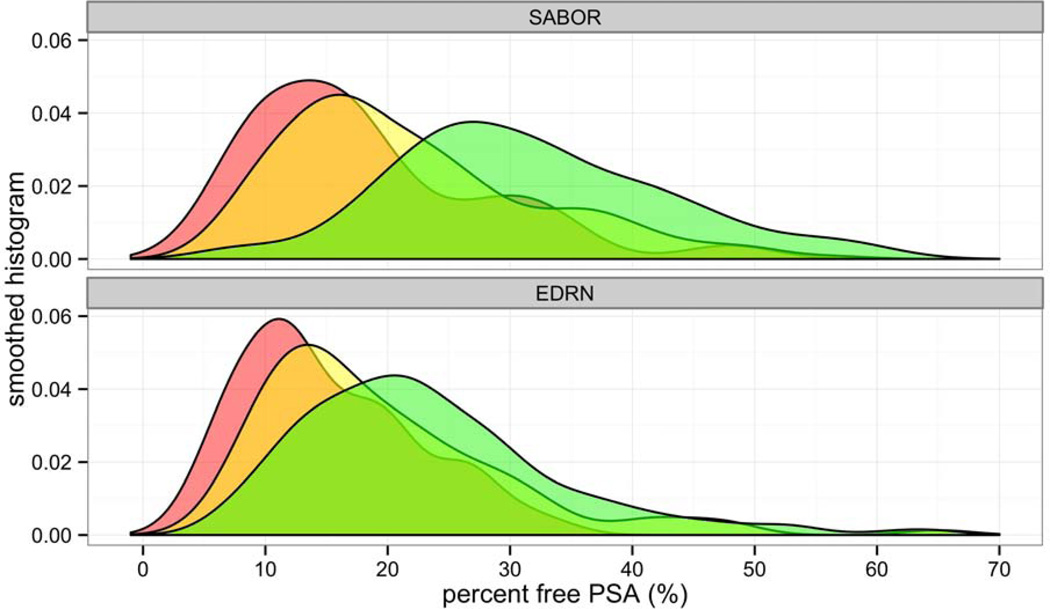

Among the 537 patients included in the SABOR biopsy cohort, 90 (16.8%) were diagnosed with high-grade prostate cancer on biopsy, 197 (36.7%) with low-grade prostate cancer, and 250 (46.6%) with no cancer. DRE findings, family history, PSA, and percent free PSA differed significantly among the three outcome groups (p < 0.05). On average, percent free PSA decreased moving from the non-cancer (mean 32.0, range 6.6 to 73.0) to low-grade (mean 22.3, range 5.6 to 72.0) to high-grade (mean 18.2, range 5.5 to 48.8) cancer groups, but there was quite some overlap between its distribution across the three outcome groups, in particular between the low- and high-grade cancer groups (Figure 1). PSA increased along the three groups with means 1.5 (range 0.1 to 11.1), 3.8 (0.3 to 28.9), and 5.8 (0.5 to 45.9) ng/mL, respectively. PSA, abnormal DRE and positive family history rates were higher in the SABOR cancer groups compared to the PCPT. In the regressions of percent free PSA on PSA in the three outcome groups as needed to form the likelihood ratios, only PSA was statistically significant (all p < 0.0001) with increasing PSA associated with decreasing percent free PSA.

Figure 1.

Smoothed histogram of distribution of percent free PSA in the SABOR development (top) and EDRN validation (bottom) cohorts, for patients diagnosed with high-grade cancer on biopsy (red), low-grade cancer (yellow), and no cancer (green).

Validation of PCPTRC 2.0 without percent free PSA on the PBCG cohorts

As to be expected the AUCs (%) of the PCPTRC 2.0 were highest for discriminating the outcomes of high-grade cancer versus no cancer (88.1, 74.3, 82.4, 74.5, 74.5, 71.3, 62.1, 75.9, 73.0, and 71.6 for PBCG cohorts 1 – 10, respectively, median 74.4, range 62.1 to 88.1). For most of the cohorts the next highest AUCS were found for discriminating high- versus low-grade cancer (77.0, 70.8, 76.2, 72.3, 65.9, 60.8, 61.7, 70.1, 65.3, and 66.5, respectively, median 68.3, range 60.8 to 77.0). Finally, the AUCs for comparing low-grade to no cancer never exceeded 70.0 (55.6, 46.0, 51.8, 50.4, 56.8, 67.6, 56.8, 57.1, 60.5 and 61.4, respectively, median 56.8, range 46.0 to 67.6). Twelve of the 30 AUCs reported above for the PCPTRC 2.0 were not statistically significantly better than the AUC of PSA. In the ProtecT cohort the AUC of PCPTRC 2.0 did not outperform PSA for prediction of any of the cancer outcomes.

Validation of PCPTRC 2.0 with percent free PSA on the EDRN cohort

Among the 466 patients included in the EDRN biopsy cohort, 133 (23.5%) were diagnosed with high-grade prostate cancer on biopsy, 109 (19.3%) with low-grade prostate cancer, and 324 (57.2%) with no cancer. Age, DRE findings, PSA, and percent free PSA differed significantly among the three outcome groups (p < 0.05). On average, percent free PSA decreased moving from the non-cancer (mean 23.4, range 6.4 to 64.8) to low-grade (mean 19.5, range 5.9 to 65.0) to high-grade (mean 15.2, range 3.7 to 34.7) cancer groups, but the overlap in its distribution across the three outcome groups was even greater than that in SABOR (Figure 1).

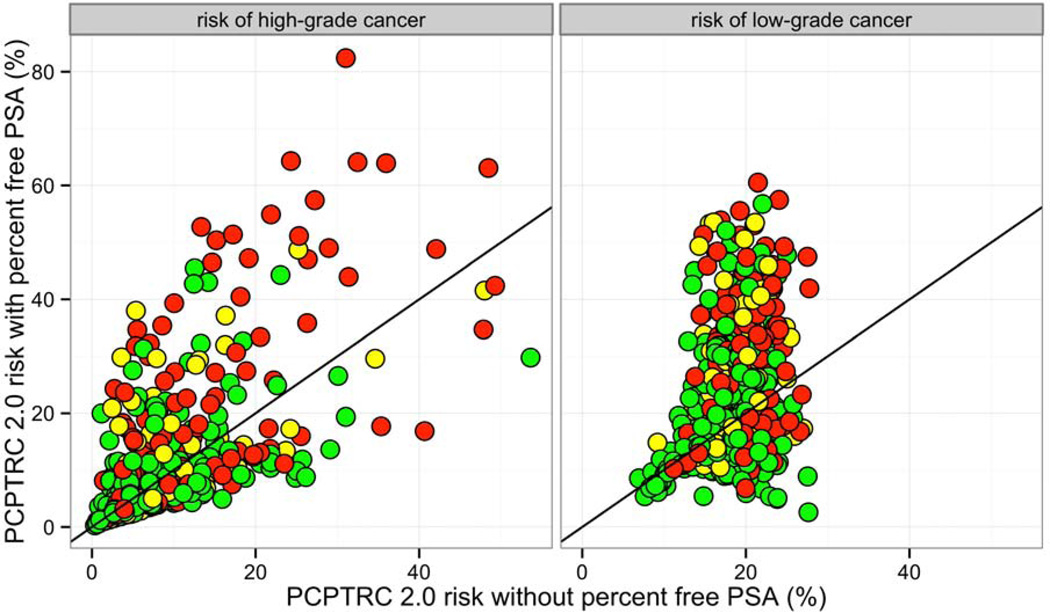

Comparison of risk predictions for high- and low-grade cancer from PCTPRC 2.0 versus PCPRTC 2.0 with percent free PSA included on the EDRN data set are shown in Figure 2. Inclusion of percent free PSA into the calculator generally led to higher risk estimates, including for patients not diagnosed with prostate cancer. Inclusion of percent free PSA significantly improved prediction for high-grade prostate cancer versus no cancer (79.8 versus 72.5, p = 0.0005), but did not for high-grade prostate cancer versus low-grade cancer (68.5 versus 66.9, p = 0.60), and low-grade prostate cancer versus no cancer (65.0, 59.4, p = 0.11).

Figure 2.

Comparison of PCPTRC 2.0 predicted risks with and without inclusion of percent free PSA for patients diagnosed with high-grade cancer on biopsy (red), low-grade cancer (yellow), and no cancer (green).

COMMENT

We and others have demonstrated the benefit of the use of a composite tool to assess a man’s risk of prostate cancer in lieu of using current measures in a dichotomous fashion.4 For example, a PSA of 3.8 ng/mL in a 55 year old Caucasian man with a prior negative biopsy and no family history of prostate cancer has an 11% risk of low-grade prostate cancer and a 3% risk of high-grade cancer. On the other hand, the same PSA in a very healthy 73 year old African American man with a family history of prostate cancer and no prior biopsy, has risks of 22% for both outcomes. Clearly, PSA alone should not be used to determine cancer risk or, more importantly, risk of high grade cancer. Similarly, a 55 year old Caucasian man with a prostate nodule who has no other risk factors and is subsequently found to have a PSA of 0.4, has risks of low-grade cancer of 8% and only a <1% risk of high-grade disease.

A limitation of this study was that percent free PSA was not measured in serum from the same participants whose biopsies were used to form the PCPTRC 2.0, but rather in an external cohort (SABOR). This necessitated a mathematical merging of patient information from two cohorts (PCPT and SABOR) to form the upgraded risk model. As new biomarkers are typically only measured on more recent case control studies, and sera from past large studies are not readily or financially accessible, our method presented the most viable option. Yet there are differences between the two cohorts, including that the PCPT cohort was collected several years earlier under a 6-core biopsy sampling scheme. The traditional prostate cancer risk factors, including PSA and DRE, were measured on the SABOR and EDRN cohorts, allowing for the incorporation of the independent information of the new markers to the standard risk factors in training the new prediction model and testing it, respectively. However, as we have previously shown ourselves, the operating characteristics of biomarkers can vary to a large extent across different patient and hospital populations [10]. Additional validation studies of the upgraded PCPTRC 2.0 are needed to fully realize the spectrum of additive value provided by percent free PSA.

Contemporary clinical practice prescribes 12 rather than the 6 cores primarily used in the PCPT, therefore raising the question as to whether a calculator built on the PCPT is outdated. An increase in the number of cores confers an increased chance of detection of prostate cancer and high-grade disease on biopsy. Using limited information on a small sample of PCPT participants that did actually receive more than 6 cores, we previously showed a statistically significantly increased, but weak, association with the detection of overall prostate cancer (odds of detection increased 1.06 per core obtained) and high-grade disease (odds of detection increased 1.16 per core) [12]. The inclusion of cores in the original PCPT Risk Calculator only barely improved the AUC and calibration in an independent validation set [12]. We therefore believe that the accuracy of PCPTRC 2.0, built on an expanded cohort from that used for the original PCPTRC, is maintained for contemporary biopsy populations. Validation across the 10 international cohorts in this study confirmed this observation. The last six of the 10 international cohorts used either primarily 10- or higher biopsy cores or mixed 6- and higher-cores [9]. Yet there was no remarkable difference between the AUCs for detection of either low- or high-grade disease among the primarily 6-core cohorts and those that used more cores. A similar observation was observed for calibration plots (data not shown). These cohorts span a time range from the early 1990s to the early 2000s. As clinical and diagnostic practice continues to improve and trends in PSA screening change, the need for periodic external validation of PCPTRC 2.0 remains. For this reason the calculator is available online.

CONCLUSIONS

Given the hazards of prostate biopsy (unnecessary cost, infection, risk of diagnosis of an inconsequential prostate cancer), it is imperative that the clinician be fully aware of the three important outcomes: no cancer, low-grade cancer, and high-grade cancer. It is likely that only the finding of a high-grade cancer and its subsequent treatment, often using multiple modalities, will provide a net-benefit to the patient. As accurate a prediction of these outcomes as possible is essential to focusing prostate cancer screening to reduce the collateral detriments of prostate cancer screening.

The online Prostate Cancer Prevention Trial (PCPT) risk calculator became available to practicing clinicians in 2006 and has been an important and widely used tool to counsel men about the risk of biopsy detectable prostate cancer. The calculator incorporates patient age, ethnicity, family history, rectal exam and prior prostate biopsy in the risk estimate. It is important to remember the details of the construct of the risk calculator to appreciate its limitations. The PCPT enrolled healthy men under 55 years of age with a PSA under 3 ng/ml. Men were followed yearly and underwent a biopsy if or when the PSA was over 4 or their exam was abnormal (for-cause biopsies). At the end of the 7 year study, an end of study biopsy was requested of all participants regardless of PSA, DRE or prior biopsy. Sextant biopsies were usually performed for both for-cause and end of study biopsies.

This current manuscript summarizes a significant update to the PCPT risk calculator. It reports the likelihood of three outcomes of prostate biopsy: negative, low-grade, or high-grade prostate cancer (Gleason >/= 7). Data from over 1,000 additional placebo arm PCPT biopsies are added to the PCPTRC 2.0. In addition, free/total PSA information from 537 patients in the SABOR cohort was used to incorporate free/total PSA into the model. Since free/total PSA was not available on the men in the PCPT, they were incorporated into the PCPTRC by a statistical technique that adjusted PCPTRC risks by likelihood ratios of the markers in SABOR to arrive at updated PCPTRC risks. The models (PCPTRC 2.0 with and without free PSA) were then externally validated on ten Prostate Biopsy Collaborative Group cohorts and one Early Detection Research Network reference set. The new risk calculator performed well in the validation cohorts. Inclusion of percent free PSA significantly improved prediction for high-grade prostate cancer versus no cancer, likely the most important discrimination.

The authors address the main limitation of the study, that the SABOR cohort is quite different and higher risk than PCPT. The SABOR negative/low-grade PCa/highgrade PCa were 46.6%/36.7%/16.8% vs. 82.1%/14.1%/3.8% in the PCPT. Because many of the factors affecting outcome (PSA, family history, ethnicity and DRE) are present in both cohorts, the incorporation of the effect of the new marker (free PSA) can be made between the cohorts. However, additional external validation will be required to increase confidence in the precision of the new model.

The authors also discussed the translation of sextant to modern biopsy schemes. As they have shown in other studies, increasing biopsy number does increase the likelihood of detection of both low- and high-grade cancer [1]. Also, the incorporation of prostate volume, or PSA density, definitely improves the discrimination of high-grade disease from a negative or low-grade result [1].

I think it is somewhat hazardous to imply that the only important outcome of an ultrasound guided prostate biopsy is the detection of high-grade disease. In the era of molecular risk stratification and active surveillance, is there a risk of missing low-grade cancers determined on first biopsy that could ultimately be under grade and risk assessed, particularly in younger men?

If we can successfully de-link the diagnosis and risk stratification of newly diagnosed men from treatment, there may be benefits for the detection of low-grade prostate cancer in some men. We know that men initially diagnosed with low risk prostate cancer who undergo surgery have an approximately 25–30% risk of higher-grade disease and a 8–15% risk of higher stage disease [2], and about 25–30% of men on active surveillance undergo treatment for various reasons within the first three years [3]. So the initial diagnosis of low-grade disease potentially might be beneficial for some younger and healthier men.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

Supported in part by funds provided by U01CA86402, U24CA115102, UM1 CA182883-01, CA37429, 5P30 CA054174-19, the Prostate Cancer Foundation, the Sidney Kimmel Center for Prostate and Urologic Cancers, P50-CA92629, and P30-CA008748.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aizer AA, Paly JJ, Zietman AL, et al. Models of care and NCCN guideline adherence in very-low-risk prostate cancer. Assessing prostate cancer risk: results from the Prostate Cancer Prevention Trial. In: Thompson IM, Ankerst DP, Chi C, et al., editors. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. Vol. 11. 2013. pp. 1364–1372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Klotz L, Zhang L, Lam A, et al. Clinical results of long-term follow-up of a large, active surveillance cohort with localized prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:126–131. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.24.2180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wilt TJ, Brawer MK, Jones KM, et al. Radical prostatectomy versus observation for localized prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:203–213. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1113162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thompson IM, Ankerst DP, Chi C, et al. Assessing prostate cancer risk: results from the Prostate Cancer Prevention Trial. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98:529–534. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ankerst DP, Groskopf J, Day JR, et al. Predicting prostate cancer risk through incorporation of prostate cancer gene 3. J Urol. 2008;180:1303–1308. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2008.06.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liang Y, Ankerst DP, Ketchum NS, et al. Prospective evaluation of operating characteristics of prostate cancer detection biomarkers. J Urol. 2011;185:104–110. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2010.08.088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thompson IM, Goodman PJ, Tangen CM, et al. The influence of finasteride on the development of prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:215–224. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ankerst DP, Koniarski T, Liang Y, et al. Updating risk prediction tools: a case study in prostate cancer. Biom J. 2012;54:127–142. doi: 10.1002/bimj.201100062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vickers AJ, Cronin AM, Roobol MJ, et al. The relationship between prostate-specific antigen and prostate cancer risk: the Prostate Biopsy Collaborative Group. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:4374–4381. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-1328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ankerst DP, Boeck A, Freedland SJ, et al. Evaluating the PCPT Risk Calculator in ten international biopsy cohorts: results from the prostate biopsy collaborative group. World Journal of Urology. 2012;30:181–187. doi: 10.1007/s00345-011-0818-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sokoll LJ, Sanda MG, Feng Z, et al. A prospective, multicenter National Cancer Institute Early Detection Research Network study of [−2]proPSA: improving prostate cancer detection and correlating with cancer aggressiveness. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2010;19:1193–1200. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-10-0007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ankerst DP, Till C, Boeck A, et al. The impact of prostate volume, number of biopsy cores and American Urological Association symptom score on the sensitivity of cancer detection using the Prostate Cancer Prevention Trial Risk Calculator. J Urol. 2013;190:70–76. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2012.12.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

REFERENCES

- 1.Ankerst DP, Till C, Boeck A, et al. The impact of prostate volume, number of biopsy cores and American Urological Association symptom score on the sensitivity of 16 cancer detection using the Prostate Cancer Prevention Trial Risk Calculator. J Urol. 2013;190:70–76. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2012.12.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kane CJ, Im R, Amling CL, Presti JC, Jr, Aronson WJ, Terris MK, Freedland SJ SEARCH Database Study Group. Outcomes after radical prostatectomy among men who are candidates for active surveillance: results from the SEARCH database. Urology. 2010;76(3):695–700. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2009.12.073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dall'Era MA, Konety BR, Cowan JE, Shinohara K, Stauf F, Cooperberg MR, Meng MV, Kane CJ, Perez N, Master VA, Carroll PR. Active surveillance for the management of prostate cancer in a contemporary cohort. Cancer. 2008;112(12):2664–2670. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]