Extracellular anions more permeant than Cl− modulate TMEM16B gating to promote channel opening, whereas less permeant anions favor channel closure.

Abstract

At least two members of the TMEM16/anoctamin family, TMEM16A (also known as anoctamin1) and TMEM16B (also known as anoctamin2), encode Ca2+-activated Cl− channels (CaCCs), which are found in various cell types and mediate numerous physiological functions. Here, we used whole-cell and excised inside-out patch-clamp to investigate the relationship between anion permeation and gating, two processes typically viewed as independent, in TMEM16B expressed in HEK 293T cells. The permeability ratio sequence determined by substituting Cl− with other anions (PX/PCl) was SCN− > I− > NO3− > Br− > Cl− > F− > gluconate. When external Cl− was substituted with other anions, TMEM16B activation and deactivation kinetics at 0.5 µM Ca2+ were modified according to the sequence of permeability ratios, with anions more permeant than Cl− slowing both activation and deactivation and anions less permeant than Cl− accelerating them. Moreover, replacement of external Cl− with gluconate, or sucrose, shifted the voltage dependence of steady-state activation (G-V relation) to more positive potentials, whereas substitution of extracellular or intracellular Cl− with SCN− shifted G-V to more negative potentials. Dose–response relationships for Ca2+ in the presence of different extracellular anions indicated that the apparent affinity for Ca2+ at +100 mV increased with increasing permeability ratio. The apparent affinity for Ca2+ in the presence of intracellular SCN− also increased compared with that in Cl−. Our results provide the first evidence that TMEM16B gating is modulated by permeant anions and provide the basis for future studies aimed at identifying the molecular determinants of TMEM16B ion selectivity and gating.

INTRODUCTION

Permeation and gating properties in most ion channels have been traditionally considered to be independent, with the opening and closing of the ion channel (gating) as a separate process from ion entrance and passage in the channel pore (permeation). However, several studies on many ion channels have described interactions between permeation and gating, suggesting that these two processes are not always independent (Hille, 2001).

Ca2+-activated Cl− channels (CaCCs) play important physiological functions, including regulation of cell excitability, fluid secretion, and smooth muscle contraction and block of polyspermy in some oocytes (Frings et al., 2000; Hartzell et al., 2005; Leblanc et al., 2005; Petersen, 2005; Wray et al., 2005; Lalonde et al., 2008; Duran et al., 2010; Berg et al., 2012; Huang et al., 2012a). Evidence that anions modify gating of endogenous CaCCs was reported in several cell types. Indeed, partial replacement of Cl− with other anions caused alterations in CaCC kinetics or conductance in lacrimal gland cells (Evans and Marty, 1986), parotid secretory cells (Ishikawa and Cook, 1993; Perez-Cornejo and Arreola, 2004), portal vein smooth muscle cells (Greenwood and Large, 1999), and Xenopus laevis oocytes (Centinaio et al., 1997; Kuruma and Hartzell, 2000; Qu and Hartzell, 2000). Moreover, Qu and Hartzell (2000) showed that the sensitivity for Ca2+ of CaCCs in Xenopus oocytes depended on the permeant anion, indicating that the permeant anion is able to affect channel gating.

The molecular identity of CaCCs has been controversial for a long time, but there is now a general consensus that at least two members of the TMEM16 (anoctamin) gene family, TMEM16A/anoctamin1 and TMEM16B/anoctamin2, encode for CaCCs (Caputo et al., 2008; Schroeder et al., 2008; Yang et al., 2008; Pifferi et al., 2009; Stephan et al., 2009; Stöhr et al., 2009). TMEM16A is expressed in secretory cells, smooth muscle cells, and several other cell types (Huang et al., 2009, 2012a), including supporting cells in the olfactory and vomeronasal epithelium (Billig et al., 2011; Dauner et al., 2012; Dibattista et al., 2012; Maurya and Menini, 2013) and microvilli of vomeronasal sensory neurons (Dibattista et al., 2012). TMEM16B is expressed at the synaptic terminal of photoreceptors (Stöhr et al., 2009; Billig et al., 2011; Dauner et al., 2013), in hippocampal cells (Huang et al., 2012b), in the cilia of olfactory sensory neurons, and in the microvilli of vomeronasal sensory neurons (Stephan et al., 2009; Hengl et al., 2010; Rasche et al., 2010; Sagheddu et al., 2010; Billig et al., 2011; Dauner et al., 2012; Dibattista et al., 2012; Maurya and Menini, 2013). Studies with knockout mice for TMEM16A or TMEM16B (Rock and Harfe, 2008; Billig et al., 2011) or knockdown of these channels further confirmed a reduction in CaCC activity (Flores et al., 2009; Galietta, 2009; Hartzell et al., 2009; Huang et al., 2012a; Kunzelmann et al., 2012a,b; Pifferi et al., 2012; Sanders et al., 2012; Scudieri et al., 2012).

At present little is known about the structure-function relations for TMEM16A and TMEM16B. Bioinformatic models based on hydropathy analysis indicate that TMEM16 proteins have eight putative transmembrane domains (Caputo et al., 2008; Schroeder et al., 2008; Yang et al., 2008). In TMEM16A, the first putative intracellular loop contains regions that are involved both in the Ca2+ and voltage dependence (Caputo et al., 2008; Ferrera et al., 2009, 2011; Xiao et al., 2011). In TMEM16B, some glutamic acids in the first putative intracellular loop contribute to voltage dependence (Cenedese et al., 2012). A recent study identified splice variants for TMEM16B and found that N-terminal sequences affect Ca2+ sensitivity (Ponissery Saidu et al., 2013).

A region located between transmembrane domains 5 and 6 was proposed to form a reentrant loop exposed to the extracellular membrane side and to be part of the channel pore. Indeed, mutations of some basic amino acids in this region of TMEM16A, such as R621E, altered ion selectivity (Yang et al., 2008), although another study did not confirm the change in ion selectivity with this mutation (Yu et al., 2012). The same group proposed a different topology in which a reentrant loop is exposed to the intracellular membrane side of the membrane, also forming the third intracellular loop. Indeed, mutagenesis of two amino acids in this region, E702 and E705, largely modified Ca2+ sensitivity of TMEM16A (Yu et al., 2012). Experiments with chimeras between TMEM16A and TMEM16B support the finding that the third intracellular loop is important for Ca2+ sensitivity (Scudieri et al., 2013). At present, no mutations significantly altering ion selectivity have been found (Yu et al., 2012).

Recent studies reported that anions modify gating of TMEM16A. Ferrera et al. (2011) showed that membrane conductance increased at all voltages when extracellular Cl− was replaced with I− or SCN−. Xiao et al. (2011) found that voltage-dependent gating of TMEM16A was facilitated by anions with high permeability or by an increase in extracellular Cl−. Here, we investigate how extracellular and intracellular anions affect gating in TMEM16B and show the presence of a strong coupling between permeation and gating.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Heterologous expression

Full-length mouse TMEM16B cDNA in pCMV-Sport6 mammalian expression plasmid was obtained from RZPD (clone identification: IRAVp968H1167D; NCBI Protein accession no. NP_705817.1). This is the retinal isoform with the same start site of the olfactory isoform used in Stephan et al. (2009) and contained exon 14 (Ponissery Saidu et al., 2013; named exon 13 in Stephan et al. [2009]). 2 µg cDNA was transfected into HEK 293T cells using FuGENE-6 or X-tremeGENE 9 (Roche). Cells were cotransfected with 0.2 µg pEGFP-C1 (Takara Bio Inc.) for fluorescent identification of transfected cells.

Electrophysiology

Electrophysiological recordings were performed in the whole-cell or inside-out patch-clamp configurations between 48 and 72 h from transfection, as previously described (Pifferi et al., 2006, 2009; Cenedese et al., 2012). Patch pipettes, made of borosilicate glass (World Precision Instruments, Inc.) with a PP-830 puller (Narishige), had a resistance of ∼3–5 MΩ or 1–2 MΩ, respectively, for whole-cell or inside-out experiments. Currents were recorded with an Axopatch 1D or Axopatch 200B amplifier controlled by Clampex 9 or 10 via a Digidata 1332A or 1440 (Axon Instruments or Molecular Devices). Data were low-pass filtered at 4 or 5 kHz and sampled at 10 kHz. Experiments were performed at room temperature (20–25°C). The bath was grounded via a 1 or 3 M KCl agar salt bridge connected to an Ag/AgCl reference electrode. A modified rapid solution exchanger (Perfusion Fast-Step SF-77B; Warner Instruments Corp.) was used to expose cells or excised membrane patches to different solutions.

In whole-cell recordings, one stimulation protocol consisted of voltage steps of 200-ms duration from a holding potential of 0 mV ranging from −100 to +100 mV (or from −200 to +200 mV), followed by a step to −100 mV. A single-exponential function was fitted to tail currents to extrapolate the tail current value at the beginning of the step to −100 mV. The conductance, G, was calculated as G = It/(Vt − Vrev), where It is the tail current, Vt is the tail voltage, −100 mV, and Vrev is the current reversal potential.

To estimate Vrev, channels were activated by a 200-ms pulse to +100 mV and then rapidly closed by application of hyperpolarizing steps. Single-exponential functions were fitted to tail currents to extrapolate the tail current value at each voltage step. Tail current values were plotted as a function of voltage, and the Vrev was estimated from a linear fit in a ±20-mV interval around Vrev.

In inside-out recordings, currents were recorded after the initial rundown, as described in Pifferi et al. (2009). Moreover, to allow the current to partially inactivate, patches were preexposed to the various Ca2+ concentrations for 500 ms before applying voltage protocols (Pifferi et al., 2009). Stimulation protocols consisted of a 100-mV voltage step of 200-ms duration from a holding potential of 0 mV, followed by a step to −100 mV or by double voltage ramps from −100 to +100 mV and back to −100 mV at 1-mV/ms rate, and the two I-V relations were averaged. The dose–response curves were obtained by exposing the patches for one second to solutions with increasing free Ca2+ concentrations. Leak currents measured in nominally 0 Ca2+ solutions were subtracted.

Ionic solutions

The same solutions were used for whole-cell and inside-out recordings, unless otherwise indicated. The standard extracellular solution contained (mM) 140 NaCl, 5 KCl, 2 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, 10 glucose, and 10 HEPES, pH 7.4. The standard intracellular solution contained (mM) 140 CsCl, 10 HEPES, 10 HEDTA (or 5 EGTA), pH 7.2, and no added Ca2+ for the nominally 0 Ca2+ solution, or various amounts of CaCl2, as calculated with the program WinMAXC (C. Patton, Stanford University, Stanford, CA), to obtain free Ca2+ in the range between 0.18 and 100 µM (Patton et al., 2004). The intracellular solution with 1 mM Ca2+ contained (mM) 140 NaCl, 10 HEPES, and 1 CaCl2, pH 7.2.

Cl− in the extracellular solution was substituted with other anions by replacing NaCl on an equimolar basis (unless otherwise indicated) with NaX, where X is the substituted anion. The control extracellular solution (140 mM Cl) used in Fig. 4 contained (mM) 140 NaCl, 2.5 K2SO4, 2 CaSO4, 1 MgSO4, and 10 HEPES, pH 7.4. For the 11 mM Cl− and 1 mM Cl− solutions, NaCl was replaced on an equimolar basis with Na-gluconate or sucrose. The osmolarity was adjusted with sucrose. In the extracellular solutions containing NaF, divalent cations were omitted. When NaF was tested in the presence of 1 mM Ca2+ at the intracellular side of inside-out patches, no current was measured, probably because of the insolubility of CaF2. When the patch pipette contained SCN−, I−, and Br−, a 1 M KCl agar salt bridge was used to connect the Ag/AgCl wire to the recording solutions. Applied voltages were not corrected for liquid junction potentials. All chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, except K2SO4 from Carlo Erba and CaSO4 from J.T.Baker.

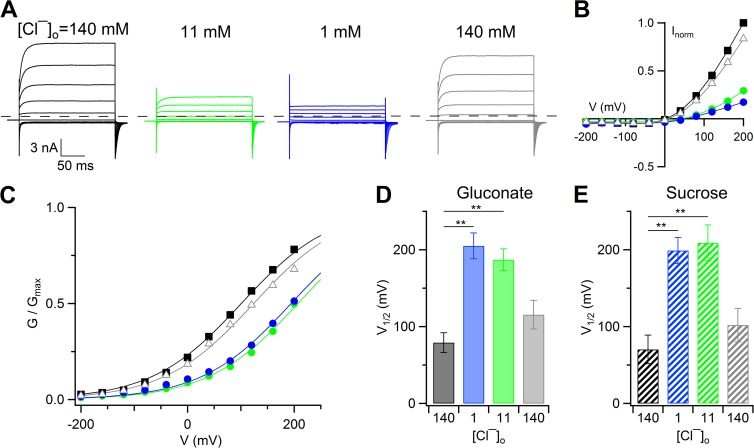

Figure 4.

Changes of voltage dependence in whole cell when extracellular Cl− was substituted with less permeant gluconate or sucrose. (A) Representative whole-cell voltage-clamp recordings at 1.5 µM Ca2+. The same cell was exposed to a solution containing NaCl (black traces), Na-gluconate (green and blue traces), and back to NaCl (gray traces). Voltage steps of 200-ms duration were given from a holding voltage of 0 mV to voltages between −200 and +200 mV in 40-mV steps, followed by a step to −100 mV. (B) Steady-state I-V relations measured at the end of the voltage steps from the cell shown at the left (A) normalized to the control value at +200 mV. Control values are represented by black squares, wash out by gray triangles, and 11 mM and 1 mM Cl−, respectively, by the green and blue circles. (C) Normalized conductances calculated from tail currents at −100 mV after prepulses between −200 and +200 mV plotted versus the prepulse voltage for the experiment shown in A. Symbols as in B. Lines are the fit to the Boltzmann equation (Eq. 1). (D and E) Mean V1/2 values in the presence of gluconate (D; n = 10) or sucrose (E; n = 3) at the indicated [Cl−]o (**, P < 0.01, Tukey’s test after ANOVA for repeated measurements). Error bars indicate SEM.

Data analysis

Data are presented as mean ± SEM, with n indicating the number of cells or patches. Statistical significance was determined using paired or unpaired t tests or ANOVA, as appropriate. When a statistically significant difference was determined with ANOVA, a post hoc Tukey’s test was used to evaluate which data groups showed significant differences. P-values <0.05 were considered significant. Data analysis and figures were made with Igor Pro software (WaveMetrics). For the sake of clarity in the figures, the capacitative transients of some traces were trimmed.

RESULTS

Anion selectivity of TMEM16B

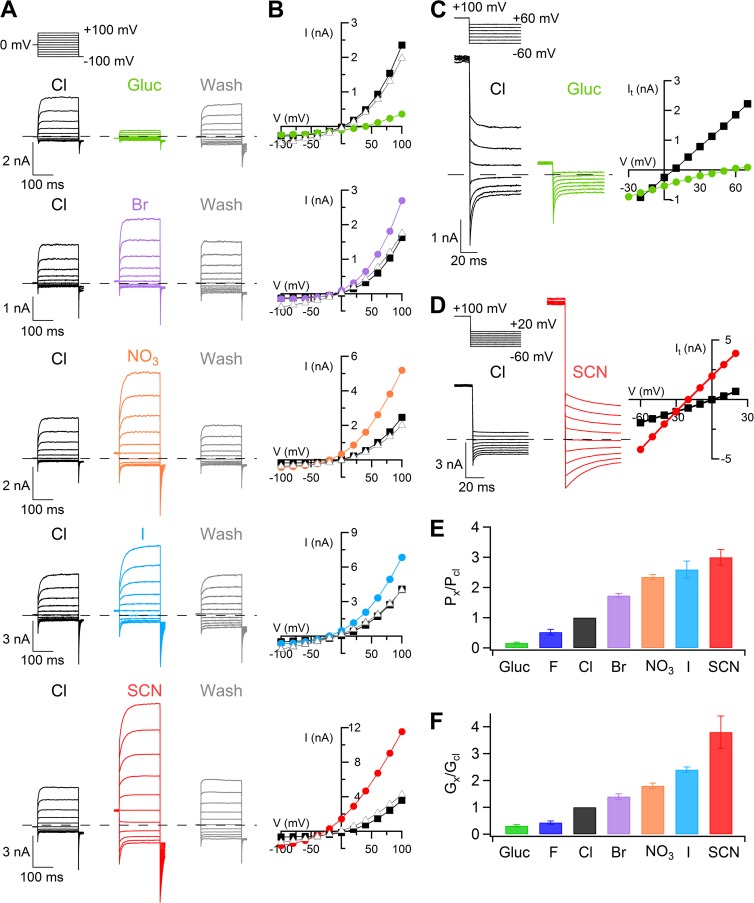

To determine the selectivity of TMEM16B to anions, we measured currents in the presence of various extracellular anions by replacing 140 mM NaCl in the Ringer solution with the Na salt of other anions. Fig. 1 A shows representative whole-cell recordings at 0.5 µM Ca2+ in the presence of Cl−, after replacement of Cl− with the indicated anions, and in Cl− after wash out. Steady-state I-V relations are plotted in Fig. 1 B. To obtain a better estimate of Vrev, we also measured tail currents (Fig. 1, C and D). When Cl− was replaced with gluconate, the outward currents decreased and Vrev shifted to positive values, revealing a lower permeability of gluconate than Cl−. On the contrary, in the presence of SCN−, I−, NO3−, and Br−, the outward currents were larger than those measured in Cl− and Vrev shifted to negative values, indicating a higher permeability of the substituted anions than Cl−. Permeability ratios (PX/PCl) were SCN− (3.0) > I− (2.6) > NO3− (2.3) > Br− (1.7) > Cl− (1.0) > F− (0.5) > gluconate (0.2). Fig. 1 (E and F) shows that the selectivity of TMEM16B estimated both from permeability ratios (PX/PCl) and from chord conductance ratios (GX/GCl) had the same sequence: SCN− > I− > NO3− > Br−> Cl− > F− > gluconate.

Figure 1.

Extracellular anion selectivity in whole-cell recordings. (A) Representative whole-cell voltage-clamp recordings obtained with an intracellular solution containing 0.5 µM Ca2+. Voltage steps of 200-ms duration were given from a holding voltage of 0 mV to voltages between −100 and +100 mV in 20-mV steps followed by a step to −100 mV, as indicated in the top part of the panel. Each cell was exposed to a control solution containing NaCl (black traces) and NaX, where X was the indicated anion, followed by wash out in NaCl (gray traces). (B) Steady-state I-V relations measured at the end of the voltage steps from the cells shown at the left (A) in control (squares), NaX (circles), or after wash out from the NaX solution (triangles). (C and D) Representative recordings from two cells at 0.5 µM Ca2+ obtained with a voltage protocol consisting of a prepulse to +100 mV from a holding voltage of 0 mV, followed by voltage steps between −60 and +70 mV (C) or −60 and +20 mV (D) in 10-mV steps. Only current recordings every 20 mV are shown in C. I-V relations measured from tail currents in Cl− (squares) or in the indicated anion (circles) are shown on the right of each cell. (E) Mean permeability ratios (PX/PCl) calculated with the Goldman-Hodgkin-Katz equation (n = 11–14). (F) Mean chord conductance ratios (GX/GCl) measured in a 40-mV interval around Vrev per each anion (n = 4–14). Error bars indicate SEM.

To obtain a direct comparison of selectivity in whole-cell and inside-out configurations, we also performed experiments in inside-out patches with different anions in the pipette solution, at the extracellular side of the membrane patch. Fig. 2 A shows currents activated at 1.5 µM Ca2+ using voltage ramps from −100 to +100 mV, in the presence of the indicated extracellular anions. PX/PCl ratios were SCN− (18.2) > I− (7.1) > NO3− (4.1) > Br− (2.3) > Cl− (1.0) > F− (0.3) > gluconate (0.1).

Figure 2.

Anion selectivity in inside-out patches. (A) I-V relations in 1.5 µM Ca2+ obtained from a ramp protocol in inside-out membrane patches. In each patch, the pipette solution contained 140 mM NaCl or the Na salt of the indicated anion. Leakage currents measured in 0 Ca2+ were subtracted. (B) Comparison of mean permeability ratios (PX/PCl) calculated with the Goldman-Hodgkin-Katz equation with different anions in the internal (n = 5–6; data for intracellular I−, NO3−, and Br− are from Pifferi et al. [2009]) or external solution (n = 6–12; as experiments shown in A). Error bars indicate SEM. (C and D) Permeability ratios (PX/PCl), obtained from experiments as in A, plotted versus ionic radius (C) or free energy of hydration (D) of the extracellular anion. Ionic radius and free energy of hydration were taken from Table 1 of Smith et al. (1999).

The sequence of PX/PCl in inside-out patches was the same as that measured in whole-cell experiments, although the value of PX/PCl for some anions was significantly higher when measured in inside-out than in whole-cell recordings (see Discussion). Moreover, we compared selectivity when anions were replaced at the extracellular or intracellular side of inside-out patches and showed that for each internal or external anion PX/PCl was not significantly different (Fig. 2 B; data for intracellular I−, NO3−, and Br− are from Pifferi et al. [2009]).

We plotted PX/PCl for extracellular anion substitution versus ionic radius (Fig. 2 C) or free energy of hydration (Fig. 2 D) of the test anion X. These plots show that PX/PCl increases with the ionic radius, with the exception of F− and gluconate. On the other side, PX/PCl increases monotonically as the free energy of hydration decreases, indicating that the facility with which the anion enters the channel is related to its free energy of hydration.

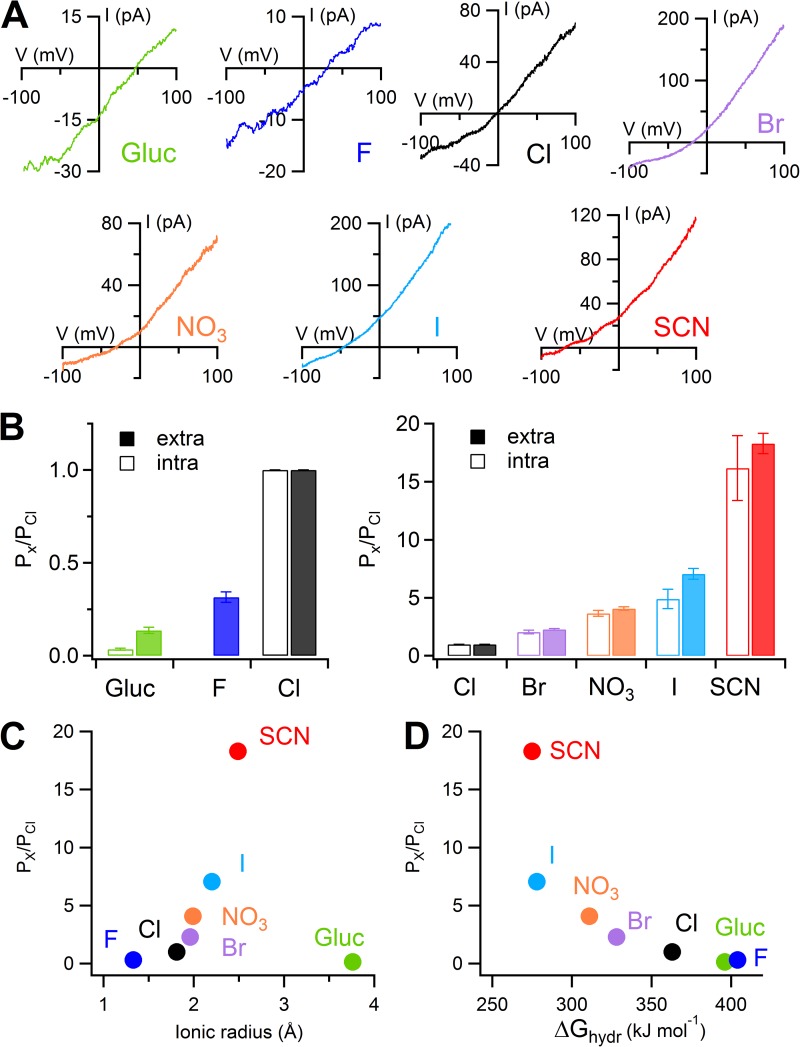

Activation and deactivation kinetics

To characterize activation and deactivation kinetics in the presence of various anions, we analyzed the time-dependent components in response to voltage steps in whole-cell recordings at 0.5 µM Ca2+. We measured the activation kinetics of currents in response to a voltage step to +100 mV from 0-mV holding voltage. The current in Cl− had an instantaneous component, related to the fraction of channels open at 0 mV, followed by a time-dependent component caused by the increase in channel opening at +100 mV. The time-dependent component was fit by a single-exponential function to calculate the time constant of activation, τact. Fig. 3 A shows superimposed normalized currents from the same cell in Cl− or with the indicated extracellular anion. No time-dependent component at +100 mV was observed when Cl− was replaced with gluconate or F− (not depicted). On average, τact at +100 mV in the presence of 0.5 µM Ca2+ was 7.7 ± 0.4 ms in Cl−, whereas it became slower with more permeant anions: 28 ± 3 ms in SCN−, 14.8 ± 1.2 ms in I−, 12.5 ± 1.0 ms in NO3−, and 11.1 ± 1.4 ms in Br−. The mean τact is plotted as a function of PX/PCl in Fig. 3 C, showing that more permeant anions significantly prolonged the time course of activation, increasing the time necessary to respond to a depolarization compared with Cl−.

Figure 3.

Activation and deactivation kinetics in whole cell with various extracellular anions. (A and B) Normalized single traces from whole-cell currents in the presence of extracellular NaCl or the Na salt of the indicated anion in 0.5 µM Ca2+. Voltage protocol similar to Fig. 1 (C and D), with a voltage step to +100 mV (A) from a holding voltage of 0 mV and followed by a step to −60 mV (B). Trace in gluconate in A is not shown because at the test potential there is a negligible time-dependent component. (C) Current activation and deactivation were fitted with a single exponential (fit not depicted for clarity). Mean activation time constants (τact) at +100 mV and deactivation time constants (τdeact) at −60 mV were plotted versus permeability ratios (n = 8–14; *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01, paired t test with Cl−). Error bars indicate SEM.

To examine the deactivation kinetics, we calculated the time constant of current deactivation (τdeact) by fitting with a single exponential function the tail currents obtained by a voltage step to −60 mV after a prepulse at +100 mV. Fig. 3 B shows superimposed normalized currents from the same cells of Fig. 3 A. In the presence of 0.5 µM Ca2+, the mean τdeact at −60 mV was 4.6 ± 0.3 ms in Cl−, whereas it became faster with less permeant anions (2.3 ± 0.5 ms in F− and 1.9 ± 0.2 ms in gluconate) and slower with more permeant anions (23.3 ± 4.8 ms in SCN−, 9.3 ± 1.4 ms in I−, 7.5 ± 0.5 ms in NO3−, and 5.8 ± 0.9 ms in Br−). The mean τdeact is plotted as a function of PX/PCl in Fig. 3 C, showing that the deactivation kinetics prolonged as a function of permeability ratios.

Voltage dependence

To investigate the effect of anions on the voltage dependence of channel activation in whole-cell recordings, we extended voltage steps from −200 to +200 mV to obtain a better estimate of voltage dependence (Fig. 4). The voltage dependence of steady-state activation (G-V relation) was analyzed measuring tail currents at the beginning of a step to −100 mV after the prepulse voltage steps. The conductance was plotted versus membrane voltage and fit by the Boltzmann equation:

| (1) |

where G is the conductance, z is the equivalent gating charge associated with voltage-dependent channel opening, V is the membrane potential, V1/2 is the membrane potential producing half-maximal activation, F is the Faraday constant, R is the gas constant, and T is the absolute temperature. Gmax was evaluated for each cell from a global fit of G-V relations in control, after anion substitutions, and after wash out.

In a first set of experiments, we decreased the extracellular Cl− concentration from 140 to 11 mM or 1 mM by replacing Cl− with equimolar concentrations of the less permeant anion gluconate, in the presence of 1.5 µM Ca2+ (Fig. 4, A and B). Fig. 4 C shows that the decrease of [Cl−]o produced a rightward shift of the G-V relation. From a global fit of G-V relations with the same Gmax and equivalent gating charge (z), V1/2 significantly changed from +79 ± 13 mV in 140 mM Cl− to +187 ± 14 mV in 11 mM [Cl−]o. When Cl− was further decreased to 1 mM, V1/2 was +205 ± 17 mV, which was not significantly different from the V1/2 value in 11 mM. The mean z value was 0.29 ± 0.02 (n = 10). Similar results were obtained when [Cl−]o was reduced by partial substitution with sucrose: V1/2 changed from +70 ± 19 mV in 140 mM Cl− to +209 ± 23 mV in 11 mM Cl− and +199 ± 23 mV in 1 mM Cl−, confirming that the shift was caused by [Cl−]o reduction rather than the presence of gluconate (Fig. 4 D).

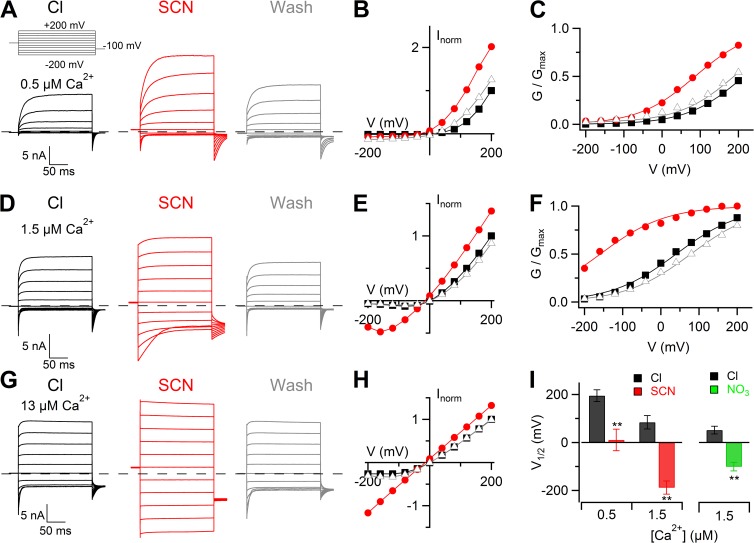

These results show that V1/2 increased when extracellular Cl− was reduced by substitution with gluconate or with sucrose, indicating that fewer channels can be activated by depolarization when the external Cl− concentration is reduced. The opposite trend, consisting of a leftward shift of the G-V relation at a given [Ca2+]i, was observed when Cl− was partially replaced by the more permeant anion SCN− (Fig. 5). Indeed, in the presence of 0.5 µM Ca2+ (Fig. 5, A–C) or 1.5 µM Ca2+ (Fig. 5, D–F), the substitution of Cl− with SCN− produced a leftward shift of the G-V relations. Upon a further increase of Ca2+ concentration to 13 µM (Fig. 5, G and H), the substitution of Cl− with SCN− caused an almost complete activation of the current at all membrane potentials in all of the experiments, preventing the possibility to numerically estimate V1/2, which was shifted to very negative potentials << −200 mV (Fig. 5, G and H).

Figure 5.

Changes of voltage dependence in whole cell when extracellular Cl− was substituted with more permeant anions. (A, D, and G) Representative whole-cell voltage-clamp recordings at the indicated [Ca2+]i. The same cell was exposed to a solution containing NaCl (black traces), NaSCN (red traces), and back to NaCl (gray traces). Voltage steps of 200-ms duration were given from a holding voltage of 0 mV to voltages between −200 and +200 mV in 40-mV steps, followed by a step to −100 mV, as indicated in the top part of A. (B, E, and H) Steady-state I-V relations measured at the end of the voltage steps from the cell shown at the left (A, D, and G, respectively) in control (squares), NaSCN (circles), and after wash out (triangles). (C and F) Normalized conductances calculated from tail currents at −100 mV after prepulses between −200 and +200 mV plotted versus the prepulse voltage. Symbols as in B and E. Lines are the fit to the Boltzmann equation (Eq. 1). (I) Mean V1/2 values at 0.5 µM Ca2+ (n = 4) or 1.5 µM Ca2+ (n = 9 in Cl−, 6 in NO3−) for Cl−, SCN−, or NO3− (**, P < 0.01 paired t test). Error bars indicate SEM.

Data from several cells at 0.5 or 1.5 µM Ca2+ are summarized in Fig. 5 I, in which mean V1/2 values are shown. At 0.5 µM Ca2+, the mean V1/2 significantly changed from +195 ± 19 mV in Cl− to +11 ± 35 mV in SCN− (n = 4). At 1.5 µM Ca2+, the mean V1/2 significantly changed from +84 ± 20 mV in Cl− to −189 ± 20 mV in SCN− (n = 9; in some experiments with SCN− at 1.5 µM Ca2+, in which the current was fully activated and V1/2 could not be evaluated, we considered V1/2 = −250 mV). The mean z value was not significantly different: 0.33 ± 0.04 and 0.26 ± 0.01, respectively, in 0.5 and 1.5 µM Ca2+.

To investigate whether the leftward shift of the G-V relation was specific to SCN− or was present also with other anions more permeant than Cl−, we performed experiments changing the external anion from Cl− to NO3− in the presence of 1.5 µM Ca2+ (representative recordings not depicted). A leftward shift of the G-V relation was observed also with NO3−, and the mean V1/2 significantly changed from +52 ± 16 mV in Cl− to −101 ± 18 mV in NO3− (n = 6), as shown in the right columns of Fig. 5 I. Thus, V1/2 decreased in the presence of SCN− or NO3−, indicating that more channels can be activated by depolarization in the presence of some anions more permeant than Cl−.

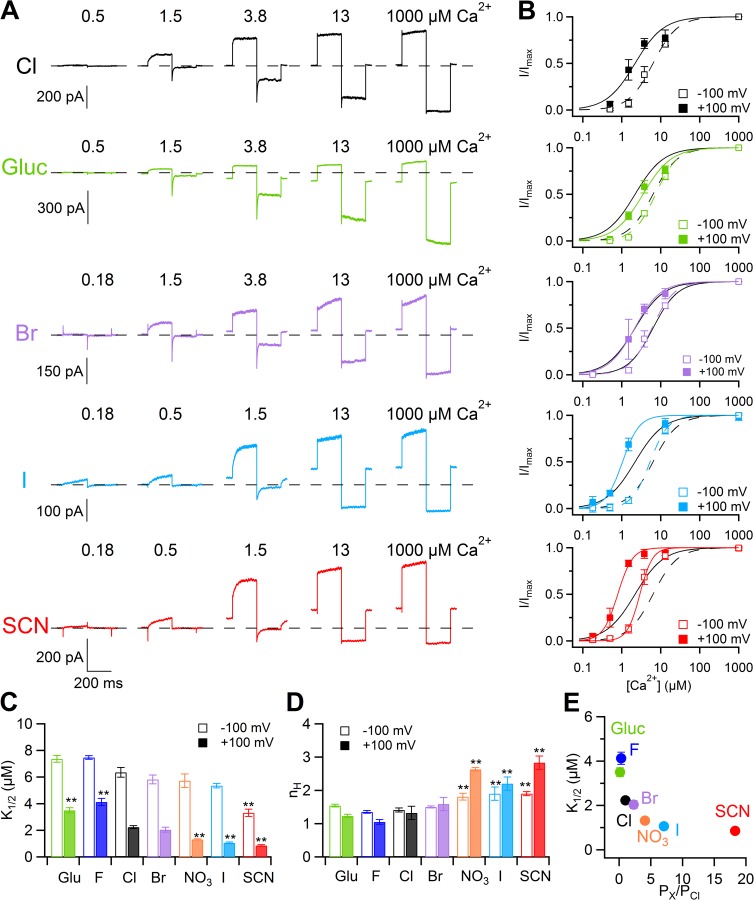

Ca2+ dependence

To investigate whether different anions modify the Ca2+ dependence of TMEM16B activation, we measured dose–response relations. The best technique to measure the Ca2+ dependence of TMEM16B is to use excised inside-out patches because channels can be activated by several [Ca2+]i in the same patch and the leakage current in the absence of Ca2+ can be subtracted from each measurement. However, as we have previously shown, the current induced by TMEM16B presents a rundown in activity in inside-out patches (Pifferi et al., 2009), limiting the number of recordings that can be compared on the same patch. For this reason, we measured currents activated by various [Ca2+]i at only two voltage steps of +100 or −100 mV, as shown in Fig. 6 A. Currents in the presence of each extracellular anion were measured at the end of each voltage step by taking the mean current between 150 and 190 ms, normalized to the maximal current at the same voltage and plotted versus [Ca2+]i (Fig. 6 B). Data were fitted by the Hill equation:

| (2) |

where I is the current, Imax is the maximal current, K1/2 is the half-maximal [Ca2+]i, and nH is the Hill coefficient.

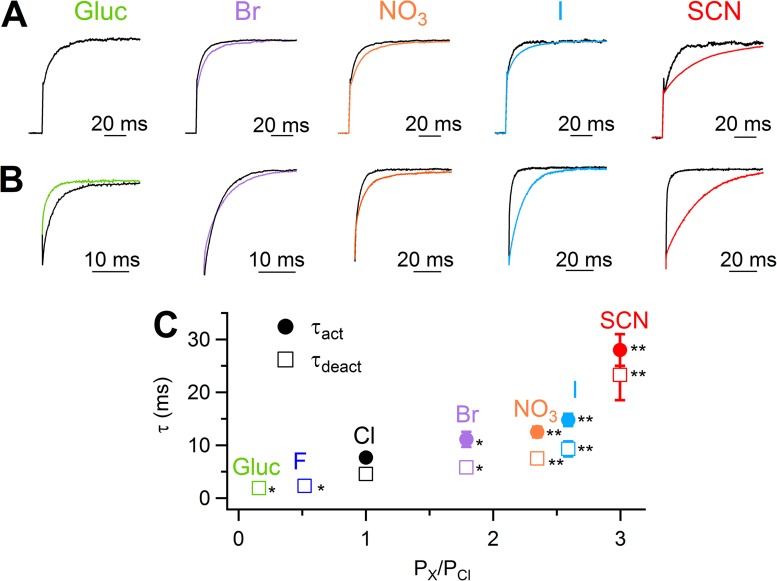

Figure 6.

Ca2+ sensitivity in inside-out patches with various extracellular anions. (A) Each row shows current traces from the same inside-out patch with the indicated anion in the pipette. The cytoplasmic side was exposed to [Ca2+]i ranging from 0.18 to 1 mM. Voltage steps of 200-ms duration were given from a holding voltage of 0 mV to +100 mV, followed by a 200-ms step to −100 mV. Leakage currents measured in 0 Ca2+ were subtracted. (B) Dose–response relations of activation by Ca2+ obtained by normalized currents at −100 or +100 mV, fitted to the Hill equation (Eq. 2). Black lines are the fit to the Hill equation in external Cl−. (C) Comparison of the mean K1/2 values at −100 or +100 mV in the presence of various anions (n = 5–13; **, P < 0.01 comparison with Cl− by Tukey’s test after ANOVA). (D) Comparison of the mean nH values at −100 or +100 mV in the presence of various anions (n = 5–13; **, P < 0.01 comparison with Cl− by Tukey’s test after ANOVA). (E) Mean K1/2 values at +100 mV plotted versus permeability ratios. Error bars indicate SEM.

Mean K1/2 values at +100 mV were lower for anions more permeant than Cl− but increased for less permeant anions (Fig. 6, B, C, and E). At −100 mV, the mean K1/2 value for SCN− was smaller than the value in Cl−, whereas there was no significant difference for values between the other anions and Cl− (Fig. 6 C). Moreover, we observed a significant increase for Hill coefficient values (nH) both at −100 and +100 mV for NO3−, I−, and SCN− compared with Cl− (Fig. 6 D). These results indicate that, at +100 mV, a lower [Ca2+]i is sufficient to activate 50% of the maximal current in the presence of external anions more permeant than Cl−, whereas a higher [Ca2+]i is required for less permeant anions.

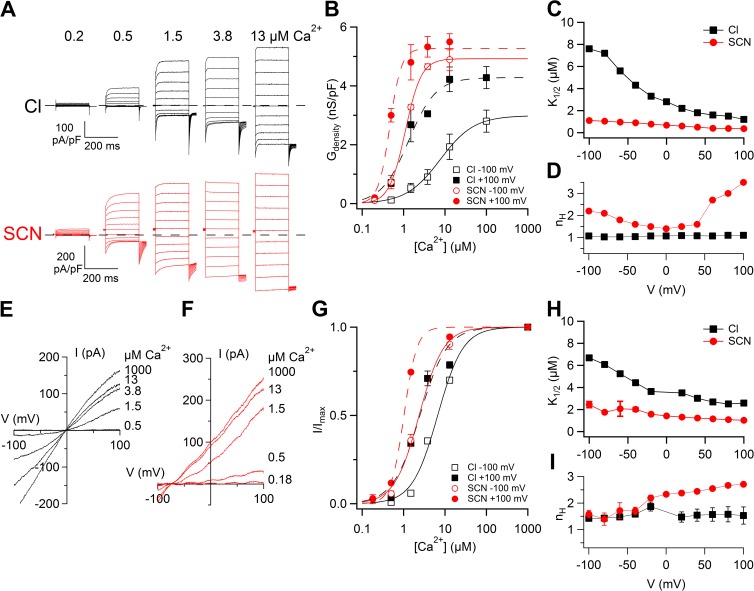

To further investigate how external SCN− modifies the Ca2+ dependence of TMEM16B compared with Cl−, we measured dose–response relations in whole-cell recordings at different voltages and compared the results with values measured with voltage ramps in inside-out patches (Fig. 7). The whole-cell configuration has the advantage of allowing the comparison of recordings with different extracellular anions in the same cell but has the disadvantage that different [Ca2+]i values have to be tested on different cells. To compare currents from different cells, current densities were calculated by dividing current amplitudes by the cell capacitance. Fig. 7 A shows whole-cell currents at various [Ca2+]i in external Cl− or SCN−. In each cell, at a given [Ca2+]i, both inward and outward currents in SCN− significantly increased with respect to those in Cl−. Dose–response relations in whole-cell were analyzed by measuring tail currents at the beginning of the step to −100 mV after prepulses ranging from −100 to +100 mV in steps of 20 mV. Mean conductance densities in the presence of external Cl− or SCN− were calculated, plotted versus [Ca2+]i, and fit at each voltage by the Hill equation:

| (3) |

where G is the conductance density, Gmax is the maximal conductance density, K1/2 is the half-maximal [Ca2+]i, and nH is the Hill coefficient.

Figure 7.

Comparison of Ca2+ sensitivity in whole-cell and inside-out patches. (A) Whole-cell recordings obtained with various [Ca2+]i in extracellular Cl− or SCN−. The same cells were recorded in Cl− or SCN− for each [Ca2+]i. Voltage protocol as in Fig. 1 A. (B) Comparison of dose–responses in Cl− or SCN− at −100 and +100 mV in whole cell obtained from conductance density calculated from tail currents plotted versus [Ca2+]i (n = 3–5). Lines are the fit to the Hill equation (Eq. 3). (C and D) Mean K1/2 and nH values from whole-cell recordings plotted versus voltage. (E and F) Currents in an inside-out patch activated by voltage ramps at the indicated [Ca2+]i in symmetrical Cl− (E) or in extracellular SCN− (F). Leakage currents measured in 0 Ca2+ were subtracted. (G) Comparison of dose–responses in Cl− or SCN− obtained by normalized currents at −100 or +100 mV, fitted to the Hill equation (Eq. 2). (H and I) Mean K1/2 and nH values from inside-out patch recordings plotted versus voltage (n = 6–7). Error bars indicate SEM.

The comparison between dose–response relations at +100 and −100 mV in external Cl− and SCN− is illustrated in Fig. 7 B. At +100 mV, K1/2 was 1.2 µM in Cl− and decreased to 0.4 µM in SCN−. Fig. 7 C shows that K1/2 slightly decreased as a function of voltage from 7.6 µM at −100 mV to 1.2 µM at +100 mV in Cl− and from 1.1 µM at −100 mV to 0.4 µM at +100 mV in SCN−. The Hill coefficient in Cl− was not voltage dependent, with a value of 1.1 at both −100 and +100 mV, whereas in SCN− nH was 2.2 at −100 mV and 3.5 at +100 mV (Fig. 7 D). Similar results were obtained from experiments in the inside-out configuration. Currents at various [Ca2+]i were activated with voltage ramps with Cl− (Fig. 7 E) or SCN− (Fig. 7 F) in the patch pipette.

Normalized dose–response relations were fit with the Hill equation (Eq. 2 and Fig. 7 G). Fig. 7 (H and I) shows that K1/2 and nH values at different voltages were similar in inside-out and in whole-cell configurations, further confirming that external SCN− increased the apparent Ca2+ affinity at all voltages compared with Cl− and increased nH at some positive voltages.

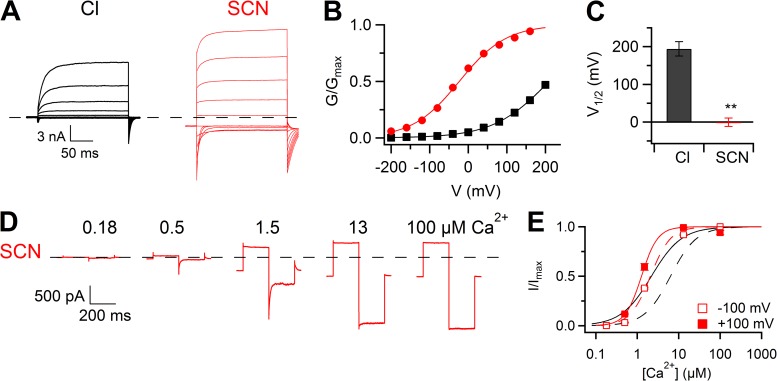

To determine whether SCN− modifies channel gating also from the intracellular side, we measured the voltage dependence of activation in whole-cell recordings in the presence of SCN− instead of Cl− at 0.5 µM Ca2+ (Fig. 8 A). G-V relations showed that V1/2 was −0.4 ± 11 mV in intracellular SCN− (n = 11; z = 0.33 ± 0.01), whereas it was +195 ± 19 mV in intracellular Cl− (Fig. 8, B and C; for Cl− data from Fig. 5 I).

Figure 8.

Effect of intracellular SCN−. (A) Whole-cell recordings at 0.5 µM Ca2+ with a standard intracellular solution containing Cl− (same traces of Fig. 5 A) or SCN−. Voltage steps as in Fig. 5. (B) Normalized conductances calculated from tail currents at −100 mV after prepulses between −200 and +200 mV plotted versus the prepulse voltage for the experiments shown in A. Lines are the fit to the Boltzmann equation (Eq. 1). (C) Mean V1/2 values in the presence of Cl− (n = 4; same data of Fig. 5 I) or SCN− (n = 11; **, P < 0.01 unpaired t test). Error bars indicate SEM. (D) Traces from an inside-out patch with SCN− at the intracellular side. [Ca2+]i ranged from 0.18 to 100 µM. Voltage steps of 200-ms duration were given from a holding voltage of 0 to +100 mV, followed by a 200-ms step to −100 mV. Leakage currents measured in 0 Ca2+ were subtracted. (E) Dose–response relations of activation by Ca2+ obtained by normalized currents at −100 or +100 mV (n = 11), fitted to the Hill equation (Eq. 2). Black lines are the fit to the Hill equation in symmetrical Cl− solutions.

Moreover, we measured dose–response relations for Ca2+ in inside-out patches in the presence of SCN− in the bathing solution (Fig. 8 D). The comparison between dose–response relations at +100 and −100 mV in intracellular Cl− and SCN− is illustrated in Fig. 8 E. At +100 mV, K1/2 was 2.2 ± 0.1 µM in Cl− and decreased to 0.85 ± 0.06 µM in SCN−; at −100 mV, K1/2 was 6.4 ± 0.4 µM in Cl− and 3.3 ± 0.3 µM in SCN−. The Hill coefficient in Cl− was not voltage dependent, with a value of 1.41 ± 0.06 at −100 mV and 1.4 ± 0.3 at +100 mV, whereas in SCN− nH was 1.90 ± 0.06 at −100 mV and 2.2 ± 0.2 at +100 mV. These results show that not only extracellular, but also intracellular SCN− affects gating of TMEM16B by producing a leftward shift of the voltage dependence and an increase of the apparent affinity for Ca2+.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we have provided evidence that, in the TMEM16B channel, permeant anions modulate the kinetics of current activation and deactivation, as well as the voltage and apparent Ca2+ sensitivity. Indeed, extracellular anions more permeant than Cl− prolonged both τact and τdeact at low Ca2+, shifted V1/2 toward more negative values, and decreased K1/2, favoring the channel’s opening. In contrast, extracellular anions less permeant than Cl− shortened τdeact, shifted V1/2 toward more positive values, and increased K1/2, contributing to channel closure. Moreover, a decrease of extracellular Cl− by replacement with sucrose also shortened τdeact (not depicted) and shifted V1/2 toward more positive values, favoring the closed state of the channel. Overall, these results indicate that the most permeant anions and Cl− itself favor the open state of TMEM16B. Furthermore, we investigated the effect of replacing Cl− with SCN− at the intracellular side of the channel and found similar gating modifications as from the extracellular side.

Anion selectivity

The sequence of permeability ratios measured in whole-cell recordings when extracellular Cl− was replaced with other anions was SCN− (3.0) > I− (2.6) > NO3− (2.3) > Br− (1.7) > Cl− (1.0) > F− (0.5) > gluconate (0.2). Moreover, the sequence of relative chord conductance followed the same order. Both sequences are in agreement, for the corresponding anions, with measurements obtained by Adomaviciene et al. (2013; see their Fig. 4) on TMEM16B and TMEM16A.

The order of anions in the sequence was the same when measurements were obtained both from whole-cell and inside-out patches. However, permeability ratios in inside-out patches were SCN− (18.2) > I− (7.1) > NO3− (4.1) > Br− (2.3) > Cl− (1.0) > F− (0.3) > gluconate (0.1), showing larger differences among anions than in whole-cell recordings. Indeed, we measured a difference in Vrev when anions were exchanged in the whole-cell or inside-out configurations. For example, when external Cl− was replaced with SCN−, the mean Vrev in whole cell was −27 ± 2 mV, whereas in the same ionic conditions with SCN− in the pipette, Vrev in inside out was −70 ± 1 mV. We measured a less negative Vrev in whole-cell than in inside-out recordings also with the other anions more permeant than Cl−. This difference may be the result of several reasons, including the loss of some intracellular factor after patch excision, such as calmodulin, and/or ion accumulation effects caused by restricted ion diffusion altering the ion concentration gradient. If SCN− or other anions entering the cell accumulated at the intracellular side of the membrane, the concentration gradient between the intracellular and extracellular side would decrease, producing a less negative Vrev value. The differences we observed are consistent with anion accumulation at the intracellular surface membrane in whole cell, whereas the continuous flow of solutions containing Cl− in inside-out membrane patches is likely to prevent or reduce the possibility of anion accumulation at the intracellular side of the membrane. In addition, we cannot exclude a difference induced by effects after patch excision. Jung et al. (2013) reported that the anion selectivity of TMEM16A is dynamically regulated by the Ca2+–calmodulin complex, whereas the effect of Ca2+–calmodulin on selectivity of TMEM16B has not been investigated yet. In any case, despite the difference in some values of permeability ratios, we obtained the same sequence for anion permeability ratios measured with different patch-clamp configurations, confirming that the permeability ratio sequence for TMEM16B follows the Hofmeister sequence or lyotropic sequence, in which anions with lower dehydration energy (lyotropos) have higher permeability compared with anions with higher dehydration energy (Wright and Diamond, 1977; Zhang and Cremer, 2006). As previously pointed out, “the relationship between anion permeability and anion energy of hydration supports the notion that anion dehydration is the limiting step in permeation” (Dawson et al., 1999; Linsdell et al., 2000).

Activation and deactivation kinetics

We found that anions more permeant than Cl− slowed both the activation and deactivation time constants at 0.5 µM Ca2+. τact at +100 mV was 7.7 ± 0.4 ms in Cl− and almost doubled to 14.8 ± 1.2 ms in I−. τdeact at −60 mV was 4.6 ± 0.3 ms in Cl− and also increased twice to 9.3 ± 1.4 ms in I−. For anions less permeant than Cl−, currents activated by depolarizing voltage steps lost any time dependence; although the τdeact values were shortened in gluconate, τdeact at −60 mV decreased to 1.9 ± 0.2 ms.

These results can be compared with the limited number of previous studies investigating the effects of permeant anions on endogenous CaCCs. Although some differences in permeability sequences were reported in different cells, in each case there was a correlation between changes in kinetics and permeability ratios.

Evans and Marty (1986) reported the following sequence of permeability ratios for CaCCs in isolated cells from lacrimal glands when Cl− was replaced with some extracellular anions: I− (2.71) > NO3− (2.39) > Br− (1.59) > Cl− (1) > F− (0.18) > isethionate (0.11) = methanesulfonate (0.11) > glutamate (0.05). The same authors investigated current kinetics at 0.5 µM Ca2+ and showed that replacement of extracellular Cl− with the two most permeant anions in these cells, I− or NO3−, led to significant alterations of both τact at +20 mV and τdeact at −60 mV. The value of τact in Cl− was 241 ± 53 ms and was shortened 0.91 and 0.83 times in I− and NO3−, respectively. The value of τdeact was 170 ± 45 ms in Cl− and increased 1.54 and 1.38 times in I− and NO3−, respectively. Other anions such as Br−, isethionate, methanesulfonate, or glutamate did not significantly modify current kinetics, indicating that “the more permeant the anion, the greater was its effect on channel kinetics” (Evans and Marty, 1986).

Greenwood and Large (1999) studied the effects of extracellular anions on the deactivation kinetics of CaCCs in smooth muscle cells isolated from rabbit portal vein with the perforated patch-clamp technique. The sequence of permeability ratios was: SCN− > I− > Br− > Cl− >> isethionate. The same authors reported that τdeact was prolonged by the external anions SCN−, I−, and Br−, which were more permeant than Cl−, whereas it was accelerated by the less permeant anion isethionate. Indeed, τdeact was 97 ± 7 ms in Cl−, 278 ± 19 ms in SCN−, 157 ± 37 ms in I−, and 67 ± 5 ms in isethionate, showing a strong correlation between permeability ratios and changes in kinetics of deactivation, suggesting that gating is linked to permeability.

In another study, Perez-Cornejo and Arreola (2004) obtained whole-cell recordings from acinar cells dissociated from rat parotid gland and measured the following permeability ratios: SCN− (4.3) > I− > (2.6) > NO3− (2.0) > Br− (1.6) > Cl− (1) > F− (0.3) > aspartate (0.1) > glutamate (0.05). Kinetics of current activation and deactivation were measured in the presence of 250 nM Ca2+. Activation kinetics increased about fourfold in SCN− and about twofold in NO3−. Deactivation kinetics increased about threefold in SCN− and about twofold in NO3−, whereas it decreased in F−. As in previous studies, the effects on kinetics largely followed the order of the permeability sequence, with anions with permeability ratios > 1 producing larger effects. Also in this case, SCN− efficacy was much larger than what was observed with the other more permeant anions, an effect consistent with the high permeability of SCN−.

Although results from CaCCs on different cells are heterogeneous, all share the same property that τact and τdeact were affected by extracellular permeant anions according with their permeability ratios, similarly to our results. τdeact was prolonged or shortened by anions more or less permeant than Cl−, respectively. One important difference from our results is that we found that τact for the TMEM16B current was prolonged by anions more permeant than Cl−, whereas in the previous work on endogenous CaCCs, τact was shortened (Evans and Marty, 1986; Perez-Cornejo and Arreola, 2004). This difference may be the result of the difference in channel proteins, as TMEM16A is most likely the CaCC expressed in lacrimal glands and in parotid acinar cells and/or by the [Ca2+]i. Indeed, we measured τact at 0.5 µM Ca2+, a concentration at which the TMEM16B current induced by depolarization has a clear time-dependent component, whereas as [Ca2+]i increases the time-dependent component decreases, and most current has an instantaneous change to the new level (Fig. 7 A). Thus, differences in τact may be explained by different Ca2+ dependencies of the time-dependent component among CaCCs.

Voltage and Ca2+ dependence of activation

We measured the voltage-dependent activation of TMEM16B at low Ca2+ concentrations, showing that the substitution of both intra- and extracellular Cl− with the more permeant SCN− caused a leftward shift of the G-V relation. Also the Cl− itself is affecting TMEM16B voltage dependence because its substitution with sucrose caused a shift of V1/2 to more positive values. Furthermore, dose–response relations for Ca2+ showed that the sensitivity for Ca2+ depends on the permeant anion and that K1/2 at +100 mV decreases as a function of permeability ratios.

Also, these results can be compared with the small number of previous studies which have investigated the effect of permeant anions on endogenous CaCCs. Ishikawa and Cook (1993) recorded in whole cell from sheep parotid secretory cells and measured the following permeability ratios: SCN− (1.80) > I− (1.09) > Cl− (1) > NO3− (0.92) > Br− (0.75). These authors analyzed current amplitudes and showed that both outward and inward currents increased when Cl− was replaced with SCN−, remained similar in I−, and decreased both with NO3− and Br−. Thus, the conductance changes followed the order of the permeability sequence. Perez-Cornejo and Arreola (2004) measured G-V relations in the presence of anions more permeant than Cl−, fit the normalized conductance with the Boltzmann equation, and reported that G-V relations were shifted toward more negative voltages with respect to the value in Cl−. The shift was larger for anions with higher permeability ratios. Anions with permeability ratios < 1 were not tested. Qu and Hartzell (2000) compared dose–response for Ca2+ in inside-out patches from Xenopus oocytes, in the presence of Cl− or SCN− at the intracellular side. By fitting the data with the Hill equation, they found that at 0 mV, the Ca2+ concentration producing 50% of the maximal current was 279 nM in Cl−, whereas it decreased about twofold, 131 nM, in SCN−, indicating that a lower [Ca2+]i is sufficient to open the channels in the presence of the more permeant anion SCN− compared with Cl−. These results show that anions more permeant than Cl− favor channel opening, whereas less permeant anions favor channel closure, in agreement with our results.

TMEM16A and TMEM16B

After the discovery that TMEM16A and TMEM16B are CaCCs, some studies reported the effect of some permeant anion on TMEM16A, whereas this is the first study on TMEM16B. Xiao et al. (2011) obtained whole-cell recordings from HEK293 cell expressing the TMEM16A(ac) isoform and showed that replacement of extracellular Cl− with NO3− or SCN− shifted G-V relations to more negative voltages. Moreover, replacement of increasing concentrations of extracellular Cl− with gluconate or sucrose shifted the G-V relations toward increasingly more positive voltages. τact and τdeact were not reported. These results are in agreement with our data.

Ferrera et al. (2011) reported that whole-cell recordings from Fischer rat thyroid cells stably expressing the TMEM16A(abc) showed an increase or decrease in conductance when extracellular Cl− was replaced with more or less permeant anions, respectively. Indeed, the conductance increased about twofold in I− and SCN−, whereas it decreased by ∼50% in gluconate. Interestingly, the same authors showed that the isoform TMEM16A(0) had some differences in selectivity compared with TMEM16A(abc). PI/PCl increased from 3.6 for TMEM16A(abc) to 4.7 for TMEM16A(0), and PSCN/PCl increased from 3.4 for TMEM16A(abc) to 5.6 for TMEM16A(0). Furthermore, the membrane conductance in I− and SCN− increased about sixfold compared with Cl for TMEM16A(0), to be compared with a twofold increase in TMEM16A(abc). τact and τdeact were not reported. It is likely that a comparison of the regions of the two isoforms may help to shed light on the molecular mechanism at the basis of the effect of permeant anion on gating.

How are permeant anions modifying gating in these channels? Greenwood and Large (1999) first suggested that the slower deactivation measured with more permeant anions could be explained if the more permeant anion favors the channel open state, for example by increasing the mean open time, possibly with a mechanism similar to the “foot in the door,” originally observed in potassium channels (Armstrong, 1971) and afterward confirmed in various other ion channels, where the most permeant ions stabilized the open conformation (Yellen, 1997). Our results could be explained by this mechanism, as the most permeant anions also produce an increase in the apparent open probability.

Overall, we found that permeant anions affected the voltage dependence and the apparent Ca2+ affinity but not the voltage sensitivity, as measured by the equivalent gating charge z. However, it is likely that permeant anions play a more complex role in addition to an increase in open probability. We observed that the substitution of Cl− with SCN− both at the extracellular and intracellular side produced a shift of the G-V relation toward more negative values, an increase of the apparent Ca2+ affinity, but also a reduction in the voltage dependence of the apparent Ca2+ affinity (Fig. 7, C and H), and an increase of the Hill coefficient at positive voltages. These results could suggest that more permeant ions can bind with higher affinity than Cl− to an allosteric binding site (inside or outside the pore) that may control the gate of the channel.

Interestingly, the effect of permeant anions on gating is not novel for Cl− channels because it is well known that anion occupancy of the pore is strictly coupled to fast gating in CLC Cl− channels. For these channels, the movement of the permeating anion in the pore contributes to the voltage dependence of the channel opening (Pusch et al., 1995; Chen and Miller, 1996; Pusch, 1996). However, the ion selectivity sequence for CLC Cl− channels, Cl− > Br− > I−, is very different from that for TMEM16B, and there is no evidence for sequence conservation patterns among CLC and TMEM16 families (Duran et al., 2010), indicating that the molecular mechanisms underlying the effect of permeant anions on gating may be rather different.

Recent work showed that the TMEM16A channel can be gated by direct binding of Ca2+ to the TMEM16A protein, rather than by binding to an accessory Ca2+-binding protein or through phosphorylation (Yu et al., 2012, 2014; Terashima et al., 2013). Moreover, mutation of two glutamic acids, E702 and E705, greatly modified the Ca2+ sensitivity of the channel and contributed to the revision of the topology of the channel (Yu et al., 2012), a topology which received further support by results obtained with chimeric proteins between TMEM16A and TMEM16B (Scudieri et al., 2013). Yu et al. (2012) also obtained data consistent with amino acids 625 to 630 contributing to an outer vestibule at the extracellular side of the membrane and with amino acids beyond 635 located deep in the putative pore. To determine whether these amino acids are part of the permeation pathway and modify ion selectivity, Yu et al. (2012) measured the permeability and conductance ratios between I− and Cl− after replacement of several amino acids between 625 and 639 with cysteine, but did not find any significant alteration in ion selectivity. Thus, at present, determinants of ion selectivity are still unknown. Future work will have to determine which regions of the protein contribute to the permeation pathway, which amino acids are critical for ion selectivity, and how permeant anions modify gating at the molecular level. Moreover, as TMEM16A and TMEM16B have several important differences and none of the chimeras recently produced had properties reproducing those of TMEM16B (Scudieri et al., 2013), it is likely that the molecular determinants of modifications of gating by permeant anions in the two channels may have some differences.

Acknowledgments

We thank Sara Migliarini (University of Pisa, Pisa, Italy) for the help with molecular biology and all members of the laboratory for discussions.

This study was supported by a grant from the Italian Ministry of Education, Universities, and Research (MIUR). S. Pifferi is a recipient of a European Union Marie Curie Reintegration Grant (OLF-STOM no. 334404).

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Lawrence G. Palmer served as editor.

Footnotes

Abbreviation used in this paper:

- CaCC

- Ca2+-activated Cl− channel

References

- Adomaviciene A., Smith K.J., Garnett H., Tammaro P. 2013. Putative pore-loops of TMEM16/anoctamin channels affect channel density in cell membranes. J. Physiol. 591:3487–3505 10.1113/jphysiol.2013.251660 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong C.M. 1971. Interaction of tetraethylammonium ion derivatives with the potassium channels of giant axons. J. Gen. Physiol. 58:413–437 10.1085/jgp.58.4.413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg J., Yang H., Jan L.Y. 2012. Ca2+-activated Cl− channels at a glance. J. Cell Sci. 125:1367–1371 10.1242/jcs.093260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Billig G.M., Pál B., Fidzinski P., Jentsch T.J. 2011. Ca2+-activated Cl− currents are dispensable for olfaction. Nat. Neurosci. 14:763–769 10.1038/nn.2821 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caputo A., Caci E., Ferrera L., Pedemonte N., Barsanti C., Sondo E., Pfeffer U., Ravazzolo R., Zegarra-Moran O., Galietta L.J.V. 2008. TMEM16A, a membrane protein associated with calcium-dependent chloride channel activity. Science. 322:590–594 10.1126/science.1163518 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cenedese V., Betto G., Celsi F., Cherian O.L., Pifferi S., Menini A. 2012. The voltage dependence of the TMEM16B/anoctamin2 calcium-activated chloride channel is modified by mutations in the first putative intracellular loop. J. Gen. Physiol. 139:285–294 10.1085/jgp.201110764 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centinaio E., Bossi E., Peres A. 1997. Properties of the Ca2+-activated Cl− current of Xenopus oocytes. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 53:604–610 10.1007/s000180050079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen T.Y., Miller C. 1996. Nonequilibrium gating and voltage dependence of the ClC-0 Cl- channel. J. Gen. Physiol. 108:237–250 10.1085/jgp.108.4.237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dauner K., Lissmann J., Jeridi S., Frings S., Möhrlen F. 2012. Expression patterns of anoctamin 1 and anoctamin 2 chloride channels in the mammalian nose. Cell Tissue Res. 347:327–341 10.1007/s00441-012-1324-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dauner K., Möbus C., Frings S., Möhrlen F. 2013. Targeted expression of anoctamin calcium-activated chloride channels in rod photoreceptor terminals of the rodent retina. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 54:3126–3136 10.1167/iovs.13-11711 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson D.C., Smith S.S., Mansoura M.K. 1999. CFTR: mechanism of anion conduction. Physiol. Rev. 79:S47–S75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dibattista M., Amjad A., Maurya D.K., Sagheddu C., Montani G., Tirindelli R., Menini A. 2012. Calcium-activated chloride channels in the apical region of mouse vomeronasal sensory neurons. J. Gen. Physiol. 140:3–15 10.1085/jgp.201210780 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duran C., Thompson C.H., Xiao Q., Hartzell H.C. 2010. Chloride channels: often enigmatic, rarely predictable. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 72:95–121 10.1146/annurev-physiol-021909-135811 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans M.G., Marty A. 1986. Calcium-dependent chloride currents in isolated cells from rat lacrimal glands. J. Physiol. 378:437–460 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrera L., Caputo A., Ubby I., Bussani E., Zegarra-Moran O., Ravazzolo R., Pagani F., Galietta L.J.V. 2009. Regulation of TMEM16A chloride channel properties by alternative splicing. J. Biol. Chem. 284:33360–33368 10.1074/jbc.M109.046607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrera L., Scudieri P., Sondo E., Caputo A., Caci E., Zegarra-Moran O., Ravazzolo R., Galietta L.J.V. 2011. A minimal isoform of the TMEM16A protein associated with chloride channel activity. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1808:2214–2223 10.1016/j.bbamem.2011.05.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flores C.A., Cid L.P., Sepúlveda F.V., Niemeyer M.I. 2009. TMEM16 proteins: the long awaited calcium-activated chloride channels? Braz. J. Med. Biol. Res. 42:993–1001 10.1590/S0100-879X2009005000028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frings S., Reuter D., Kleene S.J. 2000. Neuronal Ca2+-activated Cl− channels—homing in on an elusive channel species. Prog. Neurobiol. 60:247–289 10.1016/S0301-0082(99)00027-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galietta L.J.V. 2009. The TMEM16 protein family: a new class of chloride channels? Biophys. J. 97:3047–3053 10.1016/j.bpj.2009.09.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenwood I.A., Large W.A. 1999. Modulation of the decay of Ca2+-activated Cl− currents in rabbit portal vein smooth muscle cells by external anions. J. Physiol. 516:365–376 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.0365v.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartzell C., Putzier I., Arreola J. 2005. Calcium-activated chloride channels. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 67:719–758 10.1146/annurev.physiol.67.032003.154341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartzell H.C., Yu K., Xiao Q., Chien L.-T., Qu Z. 2009. Anoctamin/TMEM16 family members are Ca2+-activated Cl− channels. J. Physiol. 587:2127–2139 10.1113/jphysiol.2008.163709 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hengl T., Kaneko H., Dauner K., Vocke K., Frings S., Möhrlen F. 2010. Molecular components of signal amplification in olfactory sensory cilia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 107:6052–6057 10.1073/pnas.0909032107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hille B. 2001. Ion Channel of Excitable Membranes. Third edition Sinauer Associates, Inc, Sunderland, MA: 814 pp [Google Scholar]

- Huang F., Rock J.R., Harfe B.D., Cheng T., Huang X., Jan Y.N., Jan L.Y. 2009. Studies on expression and function of the TMEM16A calcium-activated chloride channel. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 106:21413–21418 10.1073/pnas.0911935106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang F., Wong X., Jan L.Y. 2012a. International Union of Basic and Clinical Pharmacology. LXXXV: calcium-activated chloride channels. Pharmacol. Rev. 64:1–15 10.1124/pr.111.005009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang W.C., Xiao S., Huang F., Harfe B.D., Jan Y.N., Jan L.Y. 2012b. Calcium-activated chloride channels (CaCCs) regulate action potential and synaptic response in hippocampal neurons. Neuron. 74:179–192 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.01.033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishikawa T., Cook D.I. 1993. A Ca2+-activated Cl− current in sheep parotid secretory cells. J. Membr. Biol. 135:261–271 10.1007/BF00211098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung J., Nam J.H., Park H.W., Oh U., Yoon J.H., Lee M.G. 2013. Dynamic modulation of ANO1/TMEM16A HCO3− permeability by Ca2+/calmodulin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 110:360–365 10.1073/pnas.1211594110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunzelmann K., Schreiber R., Kmit A., Jantarajit W., Martins J.R., Faria D., Kongsuphol P., Ousingsawat J., Tian Y. 2012a. Expression and function of epithelial anoctamins. Exp. Physiol. 97:184–192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunzelmann K., Tian Y., Martins J.R., Faria D., Kongsuphol P., Ousingsawat J., Wolf L., Schreiber R. 2012b. Airway epithelial cells—Functional links between CFTR and anoctamin dependent Cl− secretion. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 44:1897–1900 10.1016/j.biocel.2012.06.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuruma A., Hartzell H.C. 2000. Bimodal control of a Ca2+-activated Cl− channel by different Ca2+ signals. J. Gen. Physiol. 115:59–80 10.1085/jgp.115.1.59 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lalonde M.R., Kelly M.E., Barnes S. 2008. Calcium-activated chloride channels in the retina. Channels (Austin). 2:252–260 10.4161/chan.2.4.6704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leblanc N., Ledoux J., Saleh S., Sanguinetti A., Angermann J., O’Driscoll K., Britton F., Perrino B.A., Greenwood I.A. 2005. Regulation of calcium-activated chloride channels in smooth muscle cells: a complex picture is emerging. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 83:541–556 10.1139/y05-040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linsdell P., Evagelidis A., Hanrahan J.W. 2000. Molecular determinants of anion selectivity in the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator chloride channel pore. Biophys. J. 78:2973–2982 10.1016/S0006-3495(00)76836-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maurya D.K., Menini A. 2013. Developmental expression of the calcium-activated chloride channels TMEM16A and TMEM16B in the mouse olfactory epithelium. Dev. Neurobiol. In press [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton C., Thompson S., Epel D. 2004. Some precautions in using chelators to buffer metals in biological solutions. Cell Calcium. 35:427–431 10.1016/j.ceca.2003.10.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Cornejo P., Arreola J. 2004. Regulation of Ca2+-activated chloride channels by cAMP and CFTR in parotid acinar cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 316:612–617 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.02.097 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen O.H. 2005. Ca2+ signalling and Ca2+-activated ion channels in exocrine acinar cells. Cell Calcium. 38:171–200 10.1016/j.ceca.2005.06.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pifferi S., Pascarella G., Boccaccio A., Mazzatenta A., Gustincich S., Menini A., Zucchelli S. 2006. Bestrophin-2 is a candidate calcium-activated chloride channel involved in olfactory transduction. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 103:12929–12934 10.1073/pnas.0604505103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pifferi S., Dibattista M., Menini A. 2009. TMEM16B induces chloride currents activated by calcium in mammalian cells. Pflugers Arch. 458:1023–1038 10.1007/s00424-009-0684-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pifferi S., Cenedese V., Menini A. 2012. Anoctamin 2/TMEM16B: a calcium-activated chloride channel in olfactory transduction. Exp. Physiol. 97:193–199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ponissery Saidu S., Stephan A.B., Talaga A.K., Zhao H., Reisert J. 2013. Channel properties of the splicing isoforms of the olfactory calcium-activated chloride channel Anoctamin 2. J. Gen. Physiol. 141:691–703 10.1085/jgp.201210937 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pusch M. 1996. Knocking on channel’s door. The permeating chloride ion acts as the gating charge in ClC-0. J. Gen. Physiol. 108:233–236 10.1085/jgp.108.4.233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pusch M., Ludewig U., Rehfeldt A., Jentsch T.J. 1995. Gating of the voltage-dependent chloride channel CIC-0 by the permeant anion. Nature. 373:527–531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qu Z., Hartzell H.C. 2000. Anion permeation in Ca2+-activated Cl− channels. J. Gen. Physiol. 116:825–844 10.1085/jgp.116.6.825 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasche S., Toetter B., Adler J., Tschapek A., Doerner J.F., Kurtenbach S., Hatt H., Meyer H., Warscheid B., Neuhaus E.M. 2010. Tmem16b is specifically expressed in the cilia of olfactory sensory neurons. Chem. Senses. 35:239–245 10.1093/chemse/bjq007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rock J.R., Harfe B.D. 2008. Expression of TMEM16 paralogs during murine embryogenesis. Dev. Dyn. 237:2566–2574 10.1002/dvdy.21676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sagheddu C., Boccaccio A., Dibattista M., Montani G., Tirindelli R., Menini A. 2010. Calcium concentration jumps reveal dynamic ion selectivity of calcium-activated chloride currents in mouse olfactory sensory neurons and TMEM16b-transfected HEK 293T cells. J. Physiol. 588:4189–4204 10.1113/jphysiol.2010.194407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders K.M., Zhu M.H., Britton F., Koh S.D., Ward S.M. 2012. Anoctamins and gastrointestinal smooth muscle excitability. Exp. Physiol. 97:200–206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroeder B.C., Cheng T., Jan Y.N., Jan L.Y. 2008. Expression cloning of TMEM16A as a calcium-activated chloride channel subunit. Cell. 134:1019–1029 10.1016/j.cell.2008.09.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scudieri P., Sondo E., Ferrera L., Galietta L.J.V. 2012. The anoctamin family: TMEM16A and TMEM16B as calcium-activated chloride channels. Exp. Physiol. 97:177–183 10.1113/expphysiol.2011.058198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scudieri P., Sondo E., Caci E., Ravazzolo R., Galietta L.J. 2013. TMEM16A-TMEM16B chimaeras to investigate the structure-function relationship of calcium-activated chloride channels. Biochem. J. 452:443–455 10.1042/BJ20130348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith S.S., Steinle E.D., Meyerhoff M.E., Dawson D.C. 1999. Cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator. Physical basis for lyotropic anion selectivity patterns. J. Gen. Physiol. 114:799–818 10.1085/jgp.114.6.799 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephan A.B., Shum E.Y., Hirsh S., Cygnar K.D., Reisert J., Zhao H. 2009. ANO2 is the cilial calcium-activated chloride channel that may mediate olfactory amplification. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 106:11776–11781 10.1073/pnas.0903304106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stöhr H., Heisig J.B., Benz P.M., Schöberl S., Milenkovic V.M., Strauss O., Aartsen W.M., Wijnholds J., Weber B.H., Schulz H.L. 2009. TMEM16B, a novel protein with calcium-dependent chloride channel activity, associates with a presynaptic protein complex in photoreceptor terminals. J. Neurosci. 29:6809–6818 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5546-08.2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terashima H., Picollo A., Accardi A. 2013. Purified TMEM16A is sufficient to form Ca2+-activated Cl− channels. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 110:19354–19359 10.1073/pnas.1312014110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wray S., Burdyga T., Noble K. 2005. Calcium signalling in smooth muscle. Cell Calcium. 38:397–407 10.1016/j.ceca.2005.06.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright E.M., Diamond J.M. 1977. Anion selectivity in biological systems. Physiol. Rev. 57:109–156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao Q., Yu K., Perez-Cornejo P., Cui Y., Arreola J., Hartzell H.C. 2011. Voltage- and calcium-dependent gating of TMEM16A/Ano1 chloride channels are physically coupled by the first intracellular loop. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 108:8891–8896 10.1073/pnas.1102147108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y.D., Cho H., Koo J.Y., Tak M.H., Cho Y., Shim W.-S., Park S.P., Lee J., Lee B., Kim B.-M., et al. 2008. TMEM16A confers receptor-activated calcium-dependent chloride conductance. Nature. 455:1210–1215 10.1038/nature07313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yellen G. 1997. Single channel seeks permeant ion for brief but intimate relationship. J. Gen. Physiol. 110:83–85 10.1085/jgp.110.2.83 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu K., Duran C., Qu Z., Cui Y.Y., Hartzell H.C. 2012. Explaining calcium-dependent gating of anoctamin-1 chloride channels requires a revised topology. Circ. Res. 110:990–999 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.112.264440 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu K., Zhu J., Qu Z., Cui Y.Y., Hartzell H.C. 2014. Activation of the Ano1 (TMEM16A) chloride channel by calcium is not mediated by calmodulin. J. Gen. Physiol. 143:253–267 10.1085/jgp.201311047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y., Cremer P.S. 2006. Interactions between macromolecules and ions: The Hofmeister series. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 10:658–663 10.1016/j.cbpa.2006.09.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]