Abstract

A mixed-method study identified profiles of fathers who mentioned key dimensions of their parenting and linked profile membership to adolescents’ adjustment using data from 337 European American, Mexican American and Mexican immigrant fathers and their early adolescent children. Father narratives about what fathers do well as parents were thematically coded for the presence of five fathering dimensions: emotional quality (how well father and child get along), involvement (amount of time spent together), provisioning (the amount of resources provided), discipline (the amount and success in parental control), and role modeling (teaching life lessons through example). Next, latent class analysis was used to identify three patterns of the likelihood of mentioning certain fathering dimensions: an emotionally-involved group mentioned emotional quality and involvement; an affective-control group mentioned emotional quality, involvement, discipline and role modeling; and an affective-model group mentioned emotional quality and role modeling. Profiles were significantly associated with subsequent adolescents’ reports of adjustment such that adolescents of affective-control fathers reported significantly more externalizing behaviors than adolescents of emotionally-involved fathers.

Keywords: fathering, adolescent adjustment, mixed-methods, Mexican families

The importance of fathers’ roles to adolescent adjustment has increasingly gained interest (Pleck 2010) as higher levels of father involvement have been associated with fewer internalizing and externalizing symptoms (King & Sobolewski, 2006) and better school achievement (King, 2006). Despite growing evidence for the importance of fathers, the theoretical conceptualization of father involvement is still in development (Pleck 2010; Shoppe-Sullivan, McBride & Ho, 2004). Research and theory focused on ethnic minority fathers is more nascent as few studies have focused explicitly on men in ethnic minority families, especially families of Mexican descent (Cabrera & García Coll, 2004; Chuang & Moreno, 2008). Given that individuals of Mexican ancestry make up a large part of the fastest growing ethnic group in the United States (U.S. Census, 2010), special attention should be given to Mexican fathers.

This study aims to extend previous work on the conceptualization of fatherhood by utilizing a mixed-methods approach to describe how European American, Mexican American, and Mexican immigrant men evaluate their own successes and shortcomings as fathers. The first goal of this study, using narrative data, identifies the themes that emerge when men are asked to evaluate their own fathering. We then employ an ecological systems perspective (Bronfenbrenner & Morris, 1998) to address our subsequent goals. Our second goal employs a profile-oriented approach to identify profiles of fathers who differ in their likelihood of mentioning each fathering dimension. The third goal links profile membership to adolescents’ reports of adjustment (i.e., internalizing and externalizing behaviors) while accounting for the context of the family background (fathers’ ethnic/immigrant background, socioeconomic status, family-type, adolescents’ gender). Our mixed-method approach makes it possible for us to understand how Mexican immigrant, Mexican American, and European American fathers conceptualize fatherhood and how such conceptualizations are associated to family background and adolescent adjustment.

Goal 1: Identifying Dimensions of Fathering in European American and Mexican Fathers

In previous generations, views on the value of fathers changed in tandem with the socio-political context (Pleck, 2010). Fathers have been viewed as moral guides (Lamb, 1987), financial providers (Demos, 1982), gender role-models (Pleck, 1987), and nurturing parental figures (Coltrane, 2004; Dollahite & Hawkins, 1998; Parke, 1996). Another prominent focus of father research has attempted to define the components of father involvement (Lamb, Pleck, Charnov, & Levine, 1987; Pleck, 2010). An argument can be made that the father role is comprised of fathers’ accessibility (i.e., presence within the home), engagement (i.e., direct interaction and care-giving), and responsibility (i.e., the concern for direct care and safety of the child). The conceptualization of father involvement, much like the conceptualization of the father role, has changed with the growth of the fathering field and its integration with the larger parenting literature (Baumrind, 1967; Steinberg, Mounts, Lamborn, & Dornbusch, 1991). Re-conceptualizations of father involvement (Palkovitz, 2002; Pleck, 2010) now include (but are not limited to) dimensions of the parent-child affect (e.g., warmth), control (e.g., discipline and monitoring), and indirect care (e.g., arrange for transportation and care providers). Much of these changes have come about through qualitative work where primarily European American fathers have been asked to describe what good fathers do (Palkovitz, 2002) or what it means to be a good father (Morman & Floyd, 2006).

Qualitative and mixed-method research is a useful resource when aiming to understand an under-researched population or family process (Yoshikawa, Weisner, Kalil, & Way, 2008). In the case of Mexican fathers, the literature focused on this population is minimal (Saracho & Spodek, 2008). Much of the work on Latino and Mexican fathers has been conducted in family studies (and not psychology), with a focus on how family dynamics explain child and adolescent outcomes. However, in many cases, samples of European America participants have been used to conceptualize appropriate parent-child dynamics and have, in turn, been used to evaluate fathering among Latinos (Cabrera & García-Coll, 2004). However, as cultural research has shown (Fuligni, 1998; Phinney, Kim-Jo, Osorio, & Vilhjalmsdottir, 2005), parent-child dynamics and expectations can differ across ethnicities and by immigrant background. Similarly, the conceptualization of what it means to be a father may differ for European American and Mexican-origin fathers (Saracho & Spodek, 2008).

Qualitative and quantitative research specifically focused on Mexican fathers has acknowledged that great diversity exists amongst Mexican fathers (Ruiz, Roosa, & Gonzalez, 2002; Saracho & Spodek, 2008), however, research focused on Mexican fathers also provides insights into potentially important fathering dimensions. In qualitative research, Mexican immigrant and Mexican American fathers cite the importance of responsibility, providing for the family, discipline, and modeling hard work and morality (Behnke, Taylor, & Parra-Cardona, 2008; Taylor & Behnke, 2005). Fathers residing in Mexico and Mexican American fathers also mentioned themes of responsibility, involvement, and being caring parental figures (Gutmann, 1996) who engage in a large proportion of time in caretaking and monitoring activities (Coltrane, Parke, & Adams, 2004).

In this study we extend the research on fathers and father involvement by asking European American, Mexican American and Mexican immigrant fathers to describe their fathering successes and shortcomings using open-ended narratives. By asking European American, Mexican American and Mexican immigrant fathers to evaluate their own fathering behavior, it is possible to understand which dimensions of fatherhood are salient to them, and to investigate whether differences emerge in the prevalence of themes between groups. Previous research on fatherhood (Pleck, 2010) provides insights as to possible salient dimensions (i.e., parent-child affect, involvement, control, providing, and role modeling) that may appear within fathers’ narratives.

Goal 2: Identifying Profiles of Fathering Dimensions

Informing our second and third goals, the ecological systems perspective (Bronfenbrenner & Morris, 1998) suggests that development must be understood within the overall context in which an individual resides. That is, it is impossible to understand the individual in isolation from other relationships and from the context that provides meaning to those relationships. Therefore, when aiming to understand father-child relationships, it is important to account for all aspects of the relationship instead of isolating fathering dimensions and associating those dimensions to adolescent adjustment.

Within the parenting literature, certain parenting typologies have been identified in the attempt to account for the overall parenting context (Baumrind, 1967; Darling & Steinberg, 1993; Maccoby & Martin, 1983). Authoritative parents report high levels of warmth (i.e., responsiveness) and high control (i.e., demandingness), authoritarian parents report low warmth and high control, permissive parents report high warmth and low control, and neglectful parents report low warmth and low control. Limited research on parenting styles has been conducted with ethnically diverse samples (e.g., Chao, 2001; Domenech-Rodríguez, Donovick, & Crowly, 2009) and with fathers (Paquette, Bolté, Turcotte, Dubeau, & Bouchard, 2000). Within a study focused on Mexican-origin families, all parenting typologies were present in the sample although families reported a higher frequency of authoritarian parenting style than typically found in European American families (Varela et al., 2004). Within one study on fathers’ parenting styles, Paquette et al. (2000) reported an additional parenting style unique to fathers. “Stimulant parenting” characterized fathers who were warm and actively sought to introduce their children to new learning experiences. Such research highlights the need to further focus on Mexican-origin families and fathers when identifying parenting styles as there may be parenting styles that are unique or more salient to Mexican-origin families and fathers.

In previous work, parenting typologies were created through intellectual deduction and validated by utilizing arbitrary cutoffs points for parents’ reports of warmth and control; therefore, potential typologies tended to be predetermined by study methodology (Darling & Steinberg, 1993). Presently, more sophisticated methodology (e.g., cluster analysis, latent class analysis) is available to allow sample data to empirically identify typologies and classify participants (Collins & Lanza, 2010). The present study extends previous research on parenting typologies by utilizing qualitative data to identify salient fathering dimension and employing such data to identify potential patterns of fathering. Given previous work on parenting styles, it is expected, however, that parenting styles similar to authoritative (fathers will mention warmth and discipline), authoritarian (fathers will mention discipline but no warmth), permissive (fathers will mention warmth and no discipline) and stimulant (fathers will mention warmth and teaching) parenting may emerge. However, given that additional fathering dimensions will be included in our analysis this section of the study will be exploratory in nature. In addition, the focus on European American, Mexican American, and Mexican immigrant fathers will allow us to explore whether such fathering typologies are culture-specific or generalizable to an ethnically diverse sample of fathers.

Goal 3: Profiles of Fathering Dimensions and Adolescent Adjustment

Researchers of adolescent adjustment have focused much attention on adolescents’ internalizing (e.g., depressive symptoms, anxiety) and externalizing (e.g., aggressive and delinquent behaviors) behaviors. In studies that utilize variable-oriented statistical approaches (i.e., regression, correlation), greater father warmth and firm discipline have been linked with fewer adolescent externalizing behaviors (Jones, Forehand, & Beach, 2000) and lower levels of adolescent depressive symptoms (Greenberger & Chen, 1996; Vaszonyi & Belliston, 2006). Additionally, high levels of father involvement have been associated to fewer adolescent reports of externalizing behaviors (King & Sobolewski, 2006). Among Mexican-origin fathers, greater father warmth and lesser control have been associated with lower reports of adolescent deviant behavior (Ozer, Flores, Tschann, & Pasch, 2011); and father’s work-life stress (i.e., discrimination and financial difficulty; Crouter, Davis, Updegraff, Delgado, & Fortner, 2006) and adolescents increased perceptions of economic hardship (Conger, Conger, Mathews, & Elder, 1999) is related to higher reports of children’s internalizing behaviors. To summarize, parent-child warmth, involvement, discipline, and provisioning tend to be linked to adolescents’ adaptation in internalizing and externalizing behaviors.

However, many studies fail to account for the overall pattern of the father-child relationship. Ecological systems perspectives (Bronfenbrenner & Morris, 1998) suggest that the overall context should be accounted for to understand the contextual niche in which youth reside. As previously mentioned, a small body of research has focused on fathers’ parenting style (Domenech-Rodríguez et al., 2009; Paquette et al., 2000) and even less has linked fathers’ parenting style to adolescents’ adjustment (Bronte-Tinkew, Moore, & Carrano, 2006). In one study, researchers noted adolescents were more likely to report substance abuse and deviant behaviors when fathers were classified as authoritarian as compared to authoritative (Bronte-Tinkew et al., 2006); thus indicating that it may be important to account for fathers’ overall parenting style when exploring fathers’ role in adolescents’ adjustment. Within this study, we explore the associations between profiles of fatherhood and adolescents’ reports of internalizing and externalizing behavior; however, given that research on this topic is in its nascent stages, no hypotheses will be made except to assume that more positive fathering should be linked to better adjustment.

Salient family characteristics

In addition to accounting for the fathers’ overall evaluations of their fathering, it is necessary to account for other salient family characteristics such as fathers’ ethnic/immigrant background, adolescents’ gender, and family type (i.e., intact versus step family). Together, these qualities within families work in conjunction with parenting style to create a unique context in which the father-adolescent relationship gains meaning. Among ethnically diverse families, for example, the positive associations for authoritative parenting and adjustment tend to be smaller for Hispanic youth than European American youth (Steinberg, Darling, & Fletcher, 1995; Steinberg, Dornbusch, & Brown, 1992). Further, in a Mexican adolescent sample (adolescents resided in Mexico), youth reported better adjustment and more feelings of father warmth when fathers were more restrictive of youths’ behavior (Bush, Supple, & Lash, 2004). The links between parenting style and adjustment have also been associated with families’ socioeconomic status (SES) as a stronger association has been noted between father warmth and youth self-esteem in lower SES families than higher SES families (Bámaca, Umaña-Taylor, Shin, & Alfaro, 2005; Ruiz, et al., 2002). When comparing intact and step families, stepfathers have been described as being less engaged in family activities than biological fathers (Giles-Sims & Crosbie-Burnett, 1989) although high warmth and low conflict in father- and stepfather-adolescent relationship have been equally associated with lower adolescent depression (Barber & Lyons, 1994). Also, stepfathers’ parenting style is linked to less adolescent anxiety when stepfathers’ reported a more authoritative style, and adolescents reported the highest anxiety when stepfathers reported a disengaged parenting style (Crosbie-Burnett & Giles-Sims, 1994). Finally, when comparing boys and girls, studies have shown youth were better adjusted when fathers were authoritative than authoritarian but the association was stronger for boys than girls (Bronte-Tinkew et al., 2006). Such research highlights the importance of accounting for family background characteristics when understanding the associations between fathering and adolescent adjustment.

Present Study

The current study uses a mixed-methods approach to address three study goals: (1) to identify what fathering dimensions are salient to European American, Mexican American, and Mexican immigrant fathers, (2) to identify profiles of fathering dimensions, and (3) to link such profiles to adolescent adjustment. First, qualitative data will be used to identify salient dimensions of fathering. Previous fathering research alerts us to some possible salient dimensions such as parent-child affect, involvement, provisioning, discipline, and role modeling (Lamb, 2000; Pleck, 2010) and our data reduction method will explore emergent themes. Second, ecological systems perspectives (Bronfenbrenner & Morris, 1998) suggest that all fathering dimensions should be considered in tandem to understand the overall context of the father-child relationship; therefore, a profile-oriented approach will be used to identify different patterns of mentioning certain fathering dimensions. Third, profiles of fathering dimensions will be linked to adolescents’ reports of internalizing and externalizing behavior while accounting for the moderating roles of fathers’ ethnic/immigrant background, socioeconomic status, adolescents’ gender, and family type (intact vs. step family). The mixed-method multi-ethnic design of this study will allow us to extend previous research by exploring the nuances associated to the conceptualization of fatherhood.

Method

Participants

Participants were 337 fathers-adolescent dyads who provided complete data from a larger sample of 393 families (father, mother, and adolescent) residing in two urban areas in the Southwestern United States. Families were randomly selected for recruitment by school staff based on three eligibility criteria: (1) the target child was attending 7th grade, (2) all family members were of the same ethnicity, either Mexican-origin or European American, and (3) the fathers had to be biological fathers or stepfathers and live in the home for at least 1 year. Selected families were then recruited by our project staff for interview.

Of the 337 families interviewed at Wave 1 for this study, 194 were intact families (fathers were biological, not stepfathers). Of the 143 stepfamilies, stepfathers had resided in the home for an average of 5.65 years (SD= 3.03). Further, 170 fathers were European American families and of the 167 Mexican-origin families, 58 fathers reported they were born in the U.S. (Mexican American) and 109 reported they were born in Mexico (Mexican Immigrant). The Mexican-origin fathers who were born in Mexico had resided in the U.S. for an average length of residency of 16.31 years (SD = 8.20, range: 1 to 37 years). Family annual income ranged from $8k to over $100K, with a mean of $86,610 (SD = $53,926) for European American fathers, $65,478 (SD = 29,977) for Mexican American fathers, and $39,326 (SD = $21,140) for Mexican immigrant fathers. On average, European American fathers completed 14 years of school (SD = 2), Mexican American fathers completed 12 years of school (SD = 2), and Mexican immigrant fathers completed 9 years of school (SD = 4). Family income, F (2, 333) = 41.74, p < .001, and education, F (2, 330) = 89.65, p < .001, differed significantly for the three groups. Although our European American and Mexican families differed from each other, census tract analyses suggested that the fathers in the overall sample were representative of the census tract in which they resided (Schenck, Braver, Wolchik, Saenz, Cookston, & Fabricius, 2009). Overall, there were similar proportions of fathers with daughters in each group (European American 53%, Mexican American 52%, and Mexican immigrant 54%), and the average adolescent age was 12.90 years (SD = .48, range: 11.50 to 14.42). At Wave 2, when the adolescents were in the 10th grade (3 years after Wave 1), 277 of the families in our original sample (82% of our Wave 1 sample) were retained.

Procedure

At Wave 1 and Wave 2, families participated in a two-hour in-person interview where closed-ended questions asked families about their parent-child relationship, cultural development and psychosocial adjustment; and open-ended questions asked fathers about their evaluations of fathering success. Family members were interviewed separately in their preferred language. At Wave 1 all European American fathers, 98% of Mexican American fathers, and 8% of Mexican immigrant fathers preferred English. All European American adolescents and the majority of Mexican-origin adolescents preferred to be interviewed in English (98% of adolescents with Mexican American fathers, and 85% of adolescents with Mexican immigrant fathers).

Self-evaluations of fathering

To measure self-evaluations of fathering, open-ended relationship narratives were obtained at Wave 1. The fathers were asked to state three things they did best/worst as fathers using the following open-ended question:

“Think about yourself as a Dad. Think about the kind of father you are. Think about the way you act, the things you say and do as a parent. Take a moment to think about yourself and the kind of father that you are to your child. What are the two or three things that you do as a father that you think you do best/worst?”

After the narratives were transcribed and read for accuracy, a coding team of three graduate and twelve undergraduate students were assigned a pilot sample of 25 cases to discuss emerging narrative themes. The final coding scheme was comprised of five fathering dimensions which were derived from the fathering literature (Demos, 1982; Dollahite & Hawkins, 1998; Lamb et al., 1987; Parke, 1996) and themes observed in coding the pilot sample of 25 cases. A final coding scheme was developed which included five dimensions of fathering: 1) emotional quality reflected the emotional tone of the father-adolescent relationship (e.g., love, respect, pride, happiness), 2) involvement reflected the amount of time and energy a father commits to his adolescent (e.g., time shared together, shared activities, availability), 3) provisioning reflected the amount of financial or resource support a father felt he provided his adolescent (e.g., purchases, allowance, father work), 4) discipline reflected the level of control that fathers attempted to have on their children regardless of whether the control techniques were effective and consistent (e.g., limit setting, inductive conversation, demands on child), and 5) role modeling reflected fathers attempts (through their own actions or through communication) to teach values, proper behavior, and morality.

When the coding scheme was finalized, the coding of the narratives followed a 2-part molecular content analysis method. First, a final coding team of twelve undergraduate students unitized, or separated, the narratives into prepositional statements. Statements were separated into distinct units when the father (a) gave examples, (b) offered closely related but distinct statements, (c) stated a focus change, or (d) made references to a time change. Statements were not divided into separate units when they involved (a) lengthy family stories or (b) causal explanations for behavior. For example, the following fictional narrative would be coded into separate units as such:

“/I’m nice to (son)/he thinks of me as a cool dad because I let him go out./Also, I’m fair with him when he’s in trouble./For example, I listen to what he has to say before I punish him.”

Each front slash represents where a new prepositional statements begins; thus “/I’m nice to (son)/,” for example, would be considered a new prepositional statements or a new “codeable unit.”

Second, when all narratives were unitized, each unit was coded for the presence of all five fathering dimensions. For each dimension, a unit was given a code of 1 when a dimension was mentioned and a code of 0 when a dimension was not mentioned. It is important to mention fathers received a code of 1 regardless of whether a father mentioned a fathering dimension as a success or a shortcoming of their parenting as the focus of this study was on the salience (and not success) of fathering dimensions.

Each undergraduate research assistant was assigned a weekly batch of approximately 20 cases for coding. Cases were coded in the language they were received and Spanish narratives were coded by native Spanish-speaking coders who were fluent in English. Next, 20% of cases were compared against a gold standard set of codes developed by the first two authors in order to estimate inter-rater reliability. There was good inter-rater reliability to detect the beginning of a new unit indicated by a kappa of .81. The interrater reliability for detecting fathering dimensions were somewhat lower for our Spanish-speaking participants (Table 1); however, they fall within an acceptable range given that kappa tends to underestimate inter-rater agreement in cases where events occur infrequently (Andrés & Marzo, 2004).

Table 1.

Kappa Estimates and Narrative Examples of All Five Fathering Dimensions

| Dimension | Kappa | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Emotional Quality | Eng: .64 | “I guess I would say that I love him a lot. Sometimes kids can be pains but I love him regardless, no matter what” |

| Spa: .55 | “Uh, well, I think we get along well. Like when, Like when I get off of work, and, uhm, we joke around a lot” | |

| Involvement | Eng: .78 | “I wish I could spend more time with them. I have such a busy schedule, so I try to spend time with them on the weekends but I wish I could be with them more” |

| Spa: .76 | “I try to participate in all of his activities” | |

| Provisioning | Eng: .88 | “I feel that I am able to give her all that she needs, school supplies, a car, clothes, whatever she wants she can have” |

| Spa: .73 | “I sometimes cumplo caprichos (I fulfill their whims), or I (give them) whatever they need” | |

| Discipline | Eng: .61 | “Sometimes, I think the kids think they can walk all over me because I’m really bad about enforcing punishment” |

| Spa: .56 | “I teach him to be obedient, to her mother, to her father, and those who are older than him” | |

| Role modeling | Eng: .66 | “I talk with him and I give him good advice” |

| Spa: .49 | “I need to stop cussing so much in front of them … I don’t want them talking like that so I need to work on that” |

Measures

All measures were forward and back-translated into Spanish for local Mexican dialect (Foster & Martinez, 1995) and all discrepancies were resolved by the research team.

Socioeconomic status (SES)

Fathers’ education level and family income were highly correlated, r = .56, p < .01; therefore, families’ reported household income and fathers’ reported education level were standardized and averaged to create a measure of SES at Wave 1.

Internalizing behaviors

Adolescents’ anxiety was measured using a 7-item measure (e.g., “In the past month you worried about what was going to happen”) adapted from the Revised Children’s Manifest Anxiety Scale (RCMAS; Reynolds & Paget, 1981; Reynolds & Richmond, 1979). The items were “yes” or “no” items, so adolescents simply endorsed a statement or not, with a higher score indicating higher levels of anxiety. Cronbach’s alpha estimates at Wave 1 and 2 were above α = .68 for adolescents with European American fathers, above α = .52 for adolescents with Mexican American fathers, and above α = .57 for adolescents with Mexican immigrant fathers. Adolescents’ depressive symptoms over the past month were measured using a shortened 7-item (e.g., “In the past month, I felt alone;” “In the past month, I looked ugly”) version of the Child Depression Inventory scale (CDI; Kovacs, 1992). For each item, adolescents were given three related statements (e.g., “In the past month… (1) I did not feel alone, (2) I felt alone many times, (3) I felt alone all the time). Items were averaged to create a composite score where a higher score in this scale indicated more depressive symptoms. Cronbach’s alpha estimates at Wave 1 and 2 were above a = .66 for adolescents with European American fathers, above a = .57 for adolescents with Mexican American fathers, and above a = .58 for adolescents with Mexican immigrant fathers. The anxiety and depressive symptoms scales were correlated at r = .56, indicating they merited creation of the composite score. Therefore, at Wave 1 and 2 the anxiety and depression scales were standardized and averaged to create one indicator of internalization behaviors.

Externalizing behaviors

To measure externalizing behaviors at Wave 1 and 2, a modification of the Behavior Problems Index (Peterson and Zill, 1986) was used where eight items from the aggression subscale (e.g., “In the past month you destroyed things belonging to others”) and four items from the delinquency behavior subscale (e.g., “In the past month you lied or cheated”) were summed and averaged. Items were on a 3-point scale (1 = not true, 2 = somewhat true, 3 = very true) so that higher scores indicated more externalizing behaviors. Cronbach’s alpha estimates at Wave 1 and 2 were above α = .72 for adolescents with European American fathers, above α = .78 for adolescents with Mexican American fathers, and above α = .74 for adolescents with Mexican immigrant fathers.

Results

Analyses were organized to answer three research goals. Our first goal was to identify salient dimension of fathering through the use of qualitative data. Our second goal was to identify profiles of fathers who mentioned certain dimensions of fathering. Our third goal was to identify associations between profile membership and adolescents’ adjustment, in particular, adolescents’ reports of internalizing and externalizing behaviors. Descriptive information for all variables is included in Tables 2 and 3.

Table 2.

Correlations, Means, and Standard Deviations (SD) for the Full (n = 337) and European American (n = 170) Sample

| 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | 8. | 9. | 10. | 11. | 12. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Emotional Quality | − | −.05 | .01 | .06 | .08 | .11 | −.01 | .04 | −.04 | −.14 | .05 | .11 |

| 2. Involvement | −.04 | − | .04 | −.05 | −.13 | −.04 | .04 | .11 | .04 | −.05 | −.05 | −.09 |

| 3. Provisioning | .08 | −.03 | − | .05 | .08 | .02 | −.03 | −.02 | .02 | .01 | .08 | −.02 |

| 4. Discipline | .02 | −.01 | .04 | − | .03 | .00 | .10 | −.01 | .09 | .07 | .02 | .14 |

| 5. Role Modeling | −.03 | −.12* | .05 | .12* | − | −.06 | −.13 | .14 | .00 | .00 | −.05 | .08 |

| 6. Adolescents’ Gendera | .03 | .02 | .07 | .02 | −.05 | − | .03 | .03 | .11 | −.10 | .19* | −.16 |

| 7. Family Typeb | −.01 | −.07 | −.10 | .02 | −.10 | .04 | − | −.04 | .16* | .14 | .06 | .13 |

| 8. Socioeconomic Status | .02 | .21*** | −.21*** | −.05 | .09 | .01 | −.02 | − | −.18* | −.23** | −.22** | −.17* |

| 9. Internalizing Behavior W1c | −.02 | .00 | .02 | .01 | .02 | .05 | .12* | −.09 | − | .59*** | .42*** | .40*** |

| 10. Internalizing Behavior W2c | −.10 | −.09 | .05 | .05 | .00 | −.15** | .11* | −.22*** | .54*** | − | .20* | .46*** |

| 11. Externalizing Behavior W1c | .05 | −.02 | .02 | .02 | −.01 | .17** | .11 | −.09 | .41*** | .27*** | − | .44*** |

| 12. Externalizing Behavior W2c | .05 | −.14* | .02 | .06 | .06 | −.13* | .12* | −.09 | .34*** | .49*** | .48*** | − |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Full sample (n = 337) | ||||||||||||

| M | 0.83 | 0.75 | 0.32 | 0.33 | 0.47 | 0.53 | 0.42 | 0.00 | −0.08 | 16.06 | −0.01 | 15.77 |

| (SD) | (0.38) | (0.43) | (0.47) | (0.47) | (0.50) | (0.50) | (0.49) | (0.87) | (1.72) | (3.71) | (0.88) | (3.06) |

| European American (n = 170) | ||||||||||||

| M | 0.84 | 0.85 | 0.24 | 0.29 | 0.43 | 0.53 | 0.43 | 0.47 | −0.18 | 15.39 | −0.07 | 15.48 |

| (SD) | (0.37) | (0.36) | (0.43) | (0.45) | (0.50) | (0.50) | (0.50) | (0.76) | (1.80) | (3.61) | (0.88) | (2.90) |

Note. Correlations for the full sample are located below the diagonal and correlations for the European American sample are located above the diagonal.

Adolescents’ Gender is 0 = sons 1 = daughters.

Family type is 0 = intact 1 = stepfamily.

Adolescents’ reports of their adjustment included their reports of externalizing and internalizing behaviors.

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001, two-tailed

Table 3.

Correlations, Means, and Standard Deviations (SD) for the Mexican American (n = 58) and Mexican Immigrant (n = 109) Sample

| 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | 8. | 9. | 10. | 11. | 12. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Emotional Quality | − | −.02 | .11 | −.08 | −.10 | .04 | −.02 | .07 | .07 | −.07 | .09 | −.01 |

| 2. Involvement | −.11 | − | .01 | .15 | .00 | .07 | −.12 | .09 | −.03 | .01 | .05 | −.07 |

| 3. Provisioning | .19 | −.07 | − | .01 | −.06 | .11 | −.21* | −.19* | .06 | .00 | −.11 | −.05 |

| 4. Discipline | .08 | −.14 | .01 | − | .10 | −.13 | −.10 | −.08 | −.14 | .00 | −.17 | −.04 |

| 5. Role Modeling | −.17 | −.28* | .17 | .37** | − | −.13 | .00 | .21* | .01 | −.04 | −.01 | −.04 |

| 6. Adolescents’ Gendera | −.19 | .06 | .11 | .33** | .14 | − | .13 | −.01 | −.02 | −.26** | .13 | −.18 |

| 7. Family Typeb | .06 | −.23 | .02 | −.03 | −.21 | −.10 | − | −.10 | .00 | −.03 | .15 | .11 |

| 8. Socioeconomic Status | −.18 | .13 | .03 | .12 | .13 | .08 | −.14 | − | .01 | −.03 | .07 | .07 |

| 9. Internalizing Behavior W1c | −.11 | .04 | −.07 | .02 | .05 | .01 | .23 | .11 | − | .53*** | .41*** | .23* |

| 10. Internalizing Behavior W2c | .00 | −.19 | .08 | −.03 | −.01 | −.07 | .26* | −.27* | .43*** | − | .30** | .51*** |

| 11. Externalizing Behavior W1c | .07 | −.04 | .12 | .30* | .07 | .17 | .18 | .13 | .37** | .35** | − | .50*** |

| 12. Externalizing Behavior W2c | .08 | −.28* | .28* | −.03 | .14 | −.02 | .11 | .07 | .32* | .50*** | .53*** | − |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Mexican American | ||||||||||||

| M | 0.78 | 0.67 | 0.22 | 0.38 | 0.53 | 0.52 | 0.52 | −0.04 | 0.09 | 17.07 | 0.16 | 16.54 |

| (SD) | (0.42) | (0.47) | (0.42) | (0.49) | (0.50) | (0.50) | (0.50) | (0.52) | (1.64) | (3.70) | (0.88) | (3.53) |

| Mexican immigrant | ||||||||||||

| M | 0.83 | 0.65 | 0.51 | 0.36 | 0.50 | 0.54 | 0.37 | −0.72 | −0.03 | 16.58 | −0.02 | 15.87 |

| (SD) | (0.37) | (0.48) | (0.50) | (0.48) | (0.50) | (0.50) | (0.48) | (0.68) | (1.64) | (3.70) | (0.88) | (3.01) |

Note. Correlations for the Mexican American sample are located below the diagonal and correlations for the Mexican immigrant sample are located above the diagonal.

Adolescents’ Gender is 0 = sons 1 = daughters.

Family type is 0 = intact 1 = stepfamily.

Adolescents’ reports of their adjustment included their reports of externalizing and internalizing behaviors.

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001, two-tailed

Goal 1: Identifying Dimensions of Fathering Evaluations

Of the participating fathers, 337 fathers provided audible narrative data and were coded for the presence of five dimensions of fathering: 1) emotional quality, 2) involvement, 3) provisioning, 4) discipline and (5) role modeling. Most fathers’ narratives mentioned more than one dimension; therefore, each narrative was coded for the presence of as many dimensions as fit the statement. For example, a 40-year-old European American Father said “I provide for my family and I discipline him well, when he gets out of line, because I want him to be respectful of others and do what’s right.” In this case, the narrative was coded for the presence of provisioning, discipline, and role modeling. In another case, a 58-year-old Mexican immigrant father said:

“I talk with her and am involved in her life, and provide whatever she needs economically, and that’s it. I would like to have the possibility to play with her more, have the capacity to understand her school and to talk with her teachers, in order to give her the impression that school is important.”

In this case, the narrative was coded for the presence of involvement, provisioning and role modeling.

Overall, 278 (71% of the all fathers) fathers mentioned emotional quality, 253 (65%) mentioned involvement, 108 (28%) mentioned provisioning, 110 (28%) mentioned discipline, 158 (40%) mentioned role modeling. When comparing the frequency a dimension was mentioned by European America, Mexican American, and Mexican immigrant fathers, Chi-square tests indicated no differences in the percentage of fathers who mentioned emotional quality, χ2(2)= 1.33, ns, discipline, χ2(2)= 2.45, ns, or role modeling, χ2(2)= 2.48, ns. Fathers did, however, significantly differ in the likelihood of mentioning involvement, χ2(2)= 16.49, p < .001, such that European American (85%) fathers were more likely to mention involvement than Mexican American (67%) and Mexican immigrant (65%) fathers. Fathers also differed in the likelihood of mentioning provisioning, χ2(2)= 25.77, p < .001, such that Mexican immigrant (51%) fathers were more likely to mention provisioning as compared to Mexican American (23%) and European American (24%) fathers.

Goal 2: Identifying Profiles of Fathering Dimensions

Given that many of the fathers reported multiple dimensions of fathering, it was important to understand how fathers conceptualized their fatherhood role overall. A person-centered approach was used to identify patterns of the likelihood of mentioning dimensions of fathering. A Latent Class Analysis (LCA) approach, a type of mixture modeling for categorical data, uses model based procedures to identify the best number of profiles, the structure of such profiles, and the probability of belonging to a profile for each participant (Collins & Lanza, 2010). Therefore, LCA is an optimal solution for identifying patterns of fathering evaluations.

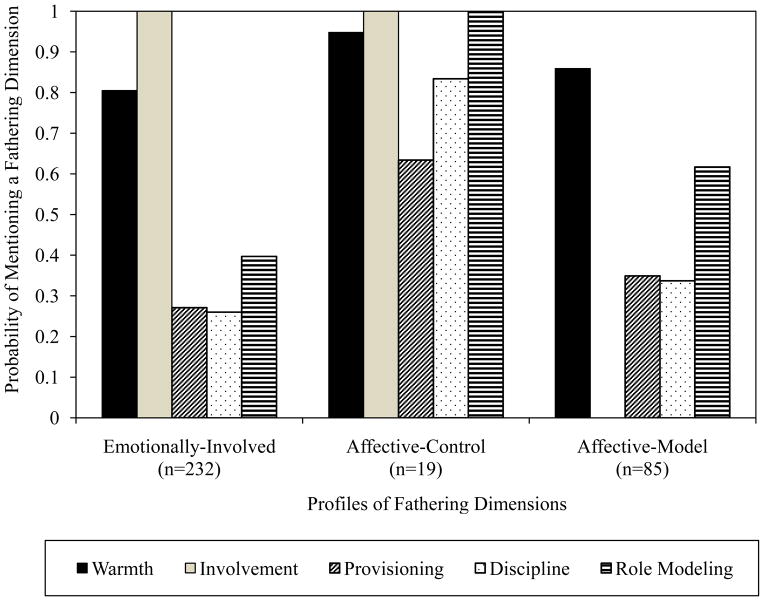

LCA was conducted using Mplus 6.1 (Muthén & Muthén, 2011) with fathers’ evaluations of emotional quality, involvement, provisioning, discipline, and role modeling included to identify patterns of fathering evaluations. Several factors were considered to choose the best profile solution: (1) model fit statistics (i.e., lowest BIC and ABIC estimates; Lo-Mendell-Rubin adjusted LRT nested model test; Table 4), (2) the stability of the profile solution (i.e., multiple start values lead to similar solution), (3) the ability to correctly classify individuals into specific profiles (Entropy score ≥ .80), and (4) the intuitive nature of the profile solution (Nylund, Asparouhov, & Muthén, 2007). Although the BIC and ABIC solution did not improve past the one-profile solution, the Lo-Mendell-Rubin adjusted LRT model test and entropy score lead us to choose the three-profile solution as the best fitting model (Nylund et al., 2007; Figure 1).

Table 4.

Model Fit Estimates for Different Latent Class Analysis Models

| 1 Profile | 2 Profile | 3 Profile | 4 Profile | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BICa | 1991.23 | 2013.83 | 2042.65 | 2070.61 |

| ABICb | 1975.37 | 1978.94 | 1988.72 | 1997.65 |

| G2 | 29.15 | 16.84 | 10.76 | 3.82 |

| Lo-Mendell-Rubind | 10.96 | 5.91 | 6.75 | |

| df | - | 6 | 6 | 6 |

| p-value | - | 0.55 | 0.04 | 0.44 |

| Entropy | - | 0.34 | 0.88 | 0.79 |

Note.

BIC means Bayesian information criterion.

ABIC means adjusted Bayesian information criterion, adjusted for sample size.

G2 refers to the likelihood ratio chi-square estimate.

Lo-Mendell-Rubin Adjusted LRT test is a nested model test, using bootstrapped methodology to replicate a normal distribution, comparing an adjusted LRT model solution with k number of profiles against a model solution with k-1 profiles. A significant p-value indicates the k profile solution improves fit as compared to the k-1 solution.

Figure 1.

Three-Profile Latent Class Analysis Solution for Men’s Self-Evaluations of their Fathering.

We labeled our first profile, the emotionally-involved fathers, as fathers in this profile were highly likely to mention emotional quality (81%) and involvement (100%), but unlikely to mention all other dimensions. The second profile, the affective-control fathers, was comprised of fathers who were highly likely to mention emotional quality (95%), involvement (100%), discipline (83%) and role modeling (100%), and moderately likely to mention provisioning (63%). The fathers in the third profile, the affective-model fathers, were highly likely to mention emotional quality (86%), moderately likely to mention role modeling (62%), and unlikely to mention all other dimensions.

Chi-square tests also indicated that profiles differed in the number of fathers within each profile that mentioned most dimensions. In particular, emotionally-involved and affective-control fathers mentioned involvement significantly more than affective-model fathers, χ2 (3) = 334.00, p < .001. Affective-control fathers mentioned provisioning, χ2 (3) = 45.28, p < .001, and discipline, χ2 (3) = 49.25, p < .001, significantly more than the emotionally-involved and affective-model fathers. In addition, affective-control fathers mentioned role modeling significantly more than all other fathers and the affective-model fathers mentioned role modeling significantly more than the emotionally-involved fathers, χ2 (3) = 27.57, p < .001. Finally, all fathers mentioned emotional quality with equally high likelihood making emotional quality the only fathering dimension where fathers belonging to different profiles did not differ.

Fathers’ ethnic/immigrant background

To ensure our profiles of fathering were representative of all three father groups, we also tested whether fathers of European American, Mexican American, and Mexican Immigrant backgrounds reported similar or distinct profiles. In LCA, the process of conducting multiple-group LCA analysis helps to test whether groups differ on the structure of the profiles, the probability of belonging to certain profiles, or both. To decide on the level of similarity amongst fathers, three models were estimated. First, we estimated an unconstrained multi-group LCA (MLCA) model where European American, Mexican American, and Mexican immigrant fathers were allowed to vary in the structure of the profiles and in their probabilities of belonging into each profile. Second, we computed a semi-constrained MLCA model, where fathers were allowed to differ in the probabilities of belonging to a profile but not in the structure of the profiles. Third, we ran a fully constrained MLCA model where fathers were not allowed to differ in the structure of the profile or the probabilities of belonging to each profile. Nested model tests using the −2 Log-Likelihood estimates of model fit were used to identify the best fitting model (Collins & Lanza, 2010). Nested model tests indicated the unconstrained model did not fit the data better than the semi-constrained model, ΔG2 (30) = 17.19, p = .97, and the semi-constrained model fit better than the fully constrained model, ΔG2 (6) = 22.09, p < .001. Therefore the semi-constrained model was chosen as the best fitting model indicating that fathers from different ethnic/immigrant backgrounds did not show different patterns of mentioning fathering dimension (i.e., they reported similar profile structures), but differed in the frequency in which certain profiles emerged within an ethnic/immigrant group. The semi-unconstrained MLCA model is statistically identical to a LCA model with correlates to predict profile membership (Collins & Lanza, 2010); therefore, instead of using fathers’ ethnicity to create different profiles of parenting for European American, Mexican American, and Mexican immigrant fathers, fathers’ ethnic/immigrant background was included as a correlate to predict profile membership. Results indicated that Mexican Immigrant fathers were less likely to belong to the emotionally-involved profile and more likely to belong to the affective-model profile as compared to European American fathers, b = 25.93, p < .01. No other logistic regressions arose as significant.

Some additional follow up analysis explored whether the fathering profiles differed in other background characteristics. Fathers within each profile did not differ based on their adolescents’ gender, χ2 (2) = 2.43, ns, or their family-type, χ2 (2) = 5.25, ns. However, fathers in the emotionally-involved profile (M = .10, SD = .88) reported a higher SES than fathers in the affective-model profile (M = −.31, SD = .77).

Goal 3: Profiles of Fathering Dimensions and Adolescent Adjustment

A classify-analyze approach was used to accomplish our third goal, linking each Wave 1 father profile to adolescents’ adjustment at Wave 2. Given that the Entropy score of our LCA solution was .88, indicating profile membership was highly differentiated (Clark & Múthen, 2010), we exported the profile membership information to run a series of regressions predicting adolescents’ reports of internalizing and externalizing behaviors at Wave 2. Predictor variables were Wave 1 adjustment, fathers’ ethnic/immigrant background, family SES, family-type, adolescents’ gender, profile membership, and all 2-way interactions for profile membership (Table 5). Per Cohen, Cohen, West and Aiken (2003), final models only included significant interaction terms.

Table 5.

Regression Analyzes Using Profile Membership to Predicting Adolescents Adjustment

| Adolescent Adjustment - Wave 2 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Internalizing | Externalizing | |||

| β | (SE) | β | (SE) | |

| Intercept | −0.06 | (.44) | 8.94*** | (.82) |

| Adjustment (Wave 1) | 0.21*** | (.03) | 0.41*** | (.05) |

| Mexican American (MA)a | 0.06 | (.14) | 0.38 | (.46) |

| Mexican Immigrant (MI)a | −0.08 | (.14) | 0.07 | (.47) |

| Socioeconomic status (SES) | −0.08 | (.07) | 0.10 | (.23) |

| Family Typeb | −0.01 | (.12) | 0.57 | (.34) |

| Adolescents’ Genderc | 0.20* | (.10) | −0.37 | (.33) |

| Affective-Controld | −0.07 | (.19) | 2.76** | (1.12) |

| Affective-Modeld | −0.20 | (.15) | 0.73† | (.40) |

| MA X Affective-Control | ||||

| MA X Affective-Model | ||||

| MI X Affective-Control | ||||

| MI X Affective-Model | ||||

| SES X Affective-Control | ||||

| SES X Affective-Model | ||||

| Family Type X Affective-Control | ||||

| Family Type X Affective-Model | 0.53* | (.24) | ||

| Gendera X Affective-Control | −2.93* | (1.38) | ||

| Gendera X Affective-Model | ||||

| R2 | 0.21*** | 0.29*** | ||

Note.

For fathers’ ethnic/immigrant background, 1=the ethnic/immigrant group mentioned (e.g. for Mexican American, 1= Mexican American), 0=European American.

Family type is 0 = intact 1 = stepfamily.

Adolescents’ Gender is 0 = sons 1 = daughters.

For fathers’ profile membership, 1=the profile mentioned (e.g. for Affective-Model, 1= Affective-Model), 0= Emotionally-Involved profile.

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001.

Results indicated that there was a significant affective-model profile by family type interaction when predicting adolescents’ internalizing behaviors. Within the affective-model profile, adolescents belonging to stepfamilies (M = .35, SD = .85) reported more internalizing behaviors at Wave 2 than adolescents belonging to intact families (M = −.19, SD = .91), b = .61, p < .01. Such differences did not emerge for adolescents of emotionally-involved and affective-control fathers. For adolescents’ reports of externalizing behaviors, an affective-control profile main effect and affective-control profile by adolescents’ gender interaction emerged as significant. Adolescents of affective-control fathers (M = 15.75, SD = .70) reported more externalizing behaviors than adolescents of emotionally-involved fathers (M = 15.54, SD = .22). Further, the affective-control profile by adolescents’ gender interaction indicated that sons of affective-control fathers (M = 18.17, SD = 2.48) reported more externalizing behaviors than sons of emotionally-involved fathers (M = 16.00, SD = 2.91), b = 2.69, p < .05. Daughters’ reports of externalizing behaviors did not differ.

Discussion

The present study aimed to increase understanding of how European American, Mexican American and Mexican immigrant fathers identify salient dimensions of fathering and how their dimension profiles are associated with adolescent adjustment. By using qualitative data it was possible to understand the dimensions of fatherhood that were salient to the men in our sample. Next, patterns of mentioning certain dimensions were explored to identify profiles of fathers with different conceptualizations of fatherhood and three profiles emerged. These profiles were predictive of adolescents’ adjustment indices three years later. Taken together, it was possible to understand the variations in how Mexican immigrant, Mexican American and European American fathers conceptualized fatherhood and its implications for adolescents’ adjustment.

The first goal, to identify salient dimensions of fatherhood, was informed by previous theoretical and empirical research on fatherhood and father involvement (Lamb, 2000; Pleck, 2010). Our coding team identified five fathering dimensions that have been given attention in fathering research (Demos, 1982; Dollahite & Hawkins, 1998; Lamb et al., 1987; Parke, 1996): emotional quality, involvement, provisioning, discipline, and role modeling. Emotional quality, involvement, and role modeling were the three most salient dimensions overall. However, fathers of different ethnic/immigrant backgrounds indicated they found certain dimensions salient at different rates. European American fathers found involvement a more salient dimension than all other fathers, and Mexican immigrant fathers found provisioning a more salient dimension than all other fathers. It is possible that paternal involvement is most salient to European American fathers because they are most likely to subscribe to current American ideals of the warm and involved father (Coltrane, 2004; Dollahite & Hawkins, 1998). On the other hand, Mexican immigrant fathers may see provisioning as a more salient paternal dimension as they were the lowest SES fathers, thus making monetary provisioning a salient aspect of family life. Interestingly, higher SES fathers were less likely than lower SES fathers to mention providing for their family as an important contribution to their families despite their high incomes. It is possible that fathers high in SES no longer evaluate their parenting in light of providing for the family because they have replaced the emphasis on providing with increased availability to their children.

Ecological systems perspectives (Bronfenbrenner & Morris, 1998) informed our second and third goals, to account for the overall context of the father-child relationship by creating profiles of fathering and relating such profiles to adolescent adjustment. Research focused on patterns of parenting (Baumrind, 1967; Darling & Steinberg, 1993) also informed our second goal as parenting literature has previously highlighted profiles of parental warmth and control (i.e., authoritarian, authoritarian, and permissive parenting). Within this study a latent class analysis approach allowed us to explore whether similar patterns emerged for fathers’ reports of their parenting style. Three profiles of fathering emerged within our study: emotionally-involved, affective-control, and affective-model. Each profile will be described in detail below; however, first it is important to mention that all three profiles emerged for the Mexican immigrant, Mexican American, and European American fathers although fathers differed in their probabilities of belonging to each profile.

Each profile of fathering represented a different pattern of the salience of fathering dimensions. For the emotionally-involved fathers, emotional quality and involvement were the most salient fathering dimensions. Emotionally-involved father reported the highest SES and were more likely to be of European American descent as compared to Mexican immigrant descent but did not differ in any other family demographics (i.e., family-type, adolescents’ gender). The emotionally-involved profile was the largest profile to emerge within our sample and adolescents of emotionally-involved fathers reported the best adjustment three years later. Therefore, this fathering profile may represent a normative pattern of fathering where fathers focus on the current fathering ideals of being warm and involved (Coltrane, 2004; Dollahite & Hawkins, 1998) when their adolescents are showing positive adjustment that require little discipline or role modeling, and the family experiences little financial stress that would make provisioning a salient fathering dimension.

For affective-control fathers, the salient dimensions were emotional quality, involvement, discipline and role modeling. Fathers of all family demographics were equally likely to belong to this fathering profile but it was also the smallest profile in this sample; therefore, it is possible that there was not enough statistical power to properly account for variation within this group. However, when exploring adolescents’ adjustment, adolescents (especially boys) of affective-control fathers reported more externalizing behaviors as compared to adolescents of emotionally-involved fathers. Such results suggest that this small group of fathers may feel that discipline and role modeling is necessary, in addition to warmth and involvement, in order to control their adolescent boys’ deviant behaviors and potentially model better behaviors.

For the affective-model fathers, emotional quality and role-modeling were the most salient fathering dimensions. These fathers reported lower SES and were more likely to be Mexican immigrant than European American. When looking at adolescent adjustment, results showed that adolescents’ whose stepfathers belonged to this group reported more internalizing behaviors than adolescent whose biological fathers belong to this group. It is unclear why differences between biological and stepfathers emerged. One possibility, however, may be associated with the absence of the involvement dimension. In previous research children whose stepfathers are disengaged report more anxiety than children whose stepfathers are authoritative or authoritarian (Crosbie-Burnett & Giles-Sims, 1994). Within this study, the affective-model fathers were the only fathers who had a zero likelihood of mentioning involvement. Perhaps, the salience of being involved in the adolescents’ life serves as a protective factor for youth who experienced their parents’ divorce. Accordingly, the stepfamilies and intact families in the emotionally-involved and affective-control profile did not differ in adolescent adjustment. The lack of involvement, however, in the affective-model profile, might increase youth’s anxiety about their place in the family and their stepfathers’ investment in their life leading to the obtained group differences. Future research should link the salience of father involvement to behavioral measure of involvement in order to understand how this fathering dimension is associated to adolescent adjustment.

Strengths and Limitations

The mixed-method, multi-ethnic, multiple-reporter, and longitudinal design of the present study allowed us to provide a more accurate depiction of the variations and effects of the conceptualization of fatherhood. The mixed-method design allowed us to employ a person-centered approach where qualitative data was used so fathers could tell us what fathering dimensions were salient to them, and quantitative analysis was used to create profiles of fathering that were later linked to adolescent adjustment. The multi-ethnic design allowed for the exploration of ethnic/immigrant differences and similarities in these various family processes. The multiple-reporters employed within this study allowed us to provide a more accurate image of how fathering profiles were associated to adolescent adjustment without confounding results with the data of a single reporter of family dynamics. Additionally, the longitudinal design where profiles of fathering were linked to adolescents’ adjustment three years later indicate that the profiles of fathering were strongly related to short term changes in adjustment. Finally, we believe these findings have important implications for clinical work with men and families as the question, “What are a few things that you do well as a father?” is rather innocuous. With training, clinicians could be informed of the themes we observed and discuss with fathers the factors that explain their responses. For example, in our study we found that the fathers of high SES rarely mentioned providing for their families as something they do well despite supporting the family comfortably. Likely, these fathers have come to provide for their families easily and no longer make meaning of their roles through the essential income they offer. Similarly, our lower SES fathers were more likely to mention provisioning and to replace their physical involvement with their children with lofty beliefs that they are good role models for their children. Likely fathers would benefit from knowing what other men say about fathering and evaluating their own fathering in this light.

Although, the present study provides insights into the conceptualization of fatherhood, some limitations must be acknowledged. First, the general parenting literature (Baumrind, 1967; Darling & Steinberg, 1993) was used as a basis for understanding the importance of using a holistic approach to studying parenting; however, our latent profiles only indicate how salient fathering dimensions are to certain father groups, and do not represent actual measures of fathers’ actions. Future research should use these latent profiles as a platform to explore profiles of fathering by using measures of actual fathering behavior and/or at least reports of successful behaviors on the given dimensions. Second, the small sample of Mexican American fathers may have reduced our power to account for group differences that would allow us to understand how Mexican American fathers differed in their conceptualization of fathers as compared to Mexican immigrant and European American fathers. Future studies should attempt to include a larger sample of Mexican American fathers.

Conclusion

Taken together, the present study provides a systematic exploration of how European American and Mexican origin fathers conceptualize their fatherhood role and how such conceptualizations impact their adolescents’ adjustment. Our findings suggest that profiles of fatherhood are generalizable to fathers of different family backgrounds as profile membership was equally likely for step and biological fathers of girls and boys and only differed slightly for Mexican immigrant and European American fathers. In addition, the findings associated with adolescent adjustment provide some suggestions for preventative research as boys whose fathers belonged to the affective-control profile and adolescents’ whose stepfathers belonged to the affective-model profile reported more externalizing and internalizing behavior problems, respectively. Such results highlight how certain profiles of fathering may be associated with more resilience or vulnerability in youth, and provide suggestions for which family styles should be targeted for intervention and prevention work.

Contributor Information

Norma J. Perez-Brena, Email: nperezbr@asu.edu.

Jeffrey T. Cookston, Email: cookston@sfsu.edu.

William V. Fabricius, Email: WILLIAM.FABRICIUS@asu.edu.

Delia Saenz, Email: DELIA.SAENZ@asu.edu.

References

- Andrés A, Marzo P. Delta: A new measure of agreement between two raters. British Journal of Mathematical and Statistical Psychology. 2004;57:1–19. doi: 10.1348/000711004849268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bámaca MY, Umaña-Taylor AJ, Shin N, Alfaro EC. Latino adolescents’ perception of parenting behaviors and self-esteem: Examining the role of neighborhood risk. Family Relations. 2005;54:621–632. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3729.2005.00346.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barber BL, Lyons JM. Family processes and adolescent adjustment in intact and remarried families. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 1994;23:421–436. doi: 10.1007/BF01538037.. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baumrind D. Child care practices anteceding three patterns of preschool behavior. Genetic Psychology Monographs. 1967;75:43–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behnke AO, Taylor BA, Parra-Cardona JR. “I hardly understand English, but...”: Mexican origin fathers describe their commitment as fathers despite the challenges of immigration. Journal of Comparative Family Studies. 2008;39:187–205. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U, Morris PA. The ecology of developmental processes. In: Damon W, Lerner RM, editors. Handbook of child psychology, Vol. 1: Theoretical models of human development. 5. New York, NY: John Wiley and Sons, Inc; 1998. pp. 993–1023. [Google Scholar]

- Bronte-Tinkew J, Moore KA, Carrano J. The father-child relationship, parenting styles, and adolescent risk behaviors in intact families. Journal of Family Issues. 2006;27:850–881. doi: 10.1177/0192513X05285296. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bush KR, Supple AJ, Lash SB. Mexican adolescents’ perceptions of parental behaviors and authority as predictors of their self-esteem and sense of familism. Marriage & Family Review. 2004;36:35–65. doi: 10.1300/J002v36n01_03. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cabrera NJ, García Coll C. Latino fathers: Uncharted territory in need of much exploration. In: Lamb ME, editor. The role of the father in child development. New York, NY: Wiley; 2004. pp. 98–120. [Google Scholar]

- Chao R. Extending research on the consequences of parenting style for Chinese Americans and European Americans. Child Development. 2001;72:1832–1843. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chuang SS, Moreno RP, editors. On new shores: Understanding immigrant fathers in North America. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J, Cohen P, West SG, Aiken LS. Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavior sciences. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Collins LM, Lanza ST. Latent class and latent transition analysis for the social, behavioral, and health sciences. New York, NY: Wiley; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Coltrane S. Fathering. In: Coleman M, Ganong L, editors. Handbook of contemporary families. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2004. pp. 224–243. [Google Scholar]

- Coltrane S, Parke RD, Adams M. Complexity of father involvement in low-income Mexican American families. Family Relations. 2004;53:179–189. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-2445.2004.00008.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Conger RD, Conger KJ, Mathews LS, Elder GH. Pathways to economic influence on adolescent adjustment. Community Psychology. 1999;27:519–541. doi: 10.1023/A:1022133228206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark SL, Muthén B. Relating latent class analysis results to variables not included in the analysis. 2010 Available at: http://statmodel2.com/download/relatinglca.pdf.

- Crosbie-Burnett M, Giles-Sims J. Adolescent adjustment and step-parenting styles. Family Relations: Special Issue on Family Processes and Child Outcomes. 1994;43:394–399. doi: 10.2307/585370. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Crouter AC, Davis KD, Updegraff K, Delgado M, Fortner M. Mexican American fathers’ occupational conditions: Links to family members’ psychological adjustment. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2006;68:843–858. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2006.00299.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darling N, Steinberg L. Parenting style as context: An integrative model. Psychological Bulletin. 1993;113:487–496. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.113.3.487. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Demos J. The changing faces of fatherhood: A new exploration in family history. In: Cath S, Gurwitt A, Ross JM, editors. Father and child: Developmental and clinical perspectives. Boston, MA: Little, Brown; 1982. pp. 425–445. [Google Scholar]

- Dollahite DC, Hawkins AJ. A conceptual ethic of generative fathering. Journal of Men’s Studies. 1998;7:109–132. doi: 10.3149/jms.0701.190. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Domenech-Rodríguez MM, Donovick M, Crowly S. Parenting styles in a cultural context: Observations of “protective parenting” in first-generation Latino. Family Processes. 2009;48:195–210. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2009.01277.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster SL, Martinez CR. Ethnicity: Conceptual and methodological issues in child clinical research. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 1995;24:214–226. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp2402_9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fuligni AJ. Authority, autonomy, and parent-adolescent conflict and cohesion: A study of adolescents from Mexican, Chinese, Filipino, and European backgrounds. Developmental Psychology. 1998;34:782–792. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.34.4.782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giles-Sims J, Crosbie-Burnett M. Adolescent power in stepfather families: An application of normative-resource theory. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1989;51:1065–1078. [Google Scholar]

- Greenberger E, Chen C. Perceived family relationships and depressed mood in early and late adolescence: A comparison of European and Asian American. Developmental Psychology. 1996;32:707–716. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.32.4.707. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gutmann MC. The meanings of macho: Being a man in Mexico City. Berkeley, Ca: University of California Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Jones DJ, Forehand R, Beach SH. Maternal and paternal parenting during adolescence: Forecasting early adult psychosocial adjustment. Adolescence. 2000;35:513– 530. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King V. Antecedents and consequences of adolescents’ relationship with stepfathers and nonresident fathers. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2006;68:910–928. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2006.00304.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King V, Sobolewski JM. Nonresident fathers’ contribution to adolescents’ well-being. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2006;68:537–557. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2006.00274.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs M. Children’s depression inventory. New York, NY: Multi-Health Systems; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Lamb ME, editor. The role of the father in child development. 3. New York, NY: Wiley; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Lamb ME. The history of research on father involvement. Marriage & Family Review. 2000;29:23–42. doi: 10.1300/J002v29n02_03. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lamb ME, Pleck J, Charnov E, Levine J. A biosocial perspective on paternal behavior and involvement. In: Lancaster J, Altmann J, Rossi A, Sherrod L, editors. Parenting across the life span: Biosocial dimensions. New York, NY: Aldine de Gruyter; 1987. pp. 111–142. [Google Scholar]

- Maccoby EE, Martin JA. Socialization in the context of the family: Parent–child interaction. In: Mussen PH, Hetherington EM, editors. Handbook of child psychology: Vol. 4. Socialization, personality, and social development. 4. New York: Wiley; 1983. pp. 1–101. [Google Scholar]

- Morman MT, Floyd K. Good fathering: Father and son perceptions of what it means to be a good father. Fathering. 2006;4:113–136. doi: 10.3149/fth.0402.113. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus version 6.1 [Computer program] Los Angeles: Muthén & Muthén; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Nylund KL, Asparouhov T, Muthén B. Deciding on the number of classes in latent class analysis and growth mixture modeling: A Monte Carlo simulation study. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal. 2007;14:535–569. doi: 10.1080/10705510701575396. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ozer EJ, Flores E, Tschann JM, Pasch LA. Parenting style, depressive symptoms, and substance use in Mexican-American adolescents. Youth and Society. 2011 doi: 10.1177/0044118X11418539. published online September 2011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Palkovitz R. Involved fathering and child development: Advancing our understanding of good fathering. In: Tamis-LeMonda CS, Cabrera N, editors. Handbook of father involvement: Multidisciplinary perspectives. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2002. pp. 119–140. [Google Scholar]

- Paquette D, Bolté C, Turcotte G, Dubeau D, Bouchard C. A new typology of fathering: defining and associated variables. Infant and Child Development. 2000;9:213–230. doi: 10.1002/1522-7219. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Parke RD. Fatherhood. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Peterson JL, Zill N. Marital disruption, parent-child relationship, and behavior problems in children. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1986;48:295–307. doi: 10.2307/352397. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Phinney JS, Kim-Jo T, Osorio S, Vilhjalmsdottir P. Autonomy and relatedness in adolescent-parent disagreements: Ethnic and developmental factors. Journal of Adolescent Research. 2005;20:8–39. doi: 10.1177/0743558404271237. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pleck JH. American fathering in historical perspective. In: Kimmel MS, editor. Changing men: New direction in research on men and masculinity. Beverly Hills, Ca: Sage; 1987. pp. 83–97. [Google Scholar]

- Pleck J. Paternal involvement: Revised conceptualization and theoretical linkages with child outcomes. In: Lamb ME, editor. The role of the father in child development. New York, NY: John Wiley and Sons; 2010. pp. 58–93. [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds CR, Paget KD. The factor analysis of the Revised Children’s Manifest Anxiety Scale for Blacks, Whites, males, and females with a national normative sample. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1981;49:352–359. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.49.3.352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds CR, Richmond BO. Factor structure and construct validity of “What I Think and Feel”: The Revised Children’s Manifest Anxiety Scale. Journal of Personality Assessment. 1979;43:281–283. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa4303_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz SY, Roosa MW, Gonzalez NA. Predictors of self-esteem for Mexican American and European American youths: A reexamination of the influence of parenting. Journal of Family Psychology. 2002;16:70–80. doi: 10.1037//0893-3200.16.1.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saracho ON, Spodek B. Challenging the stereotypes of Mexican American fathers. Journal of Early Childhood Education. 2008;35:223–231. doi: 10.1007/s10643-007-0199-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schenck CE, Braver SL, Wolchik SA, Saenz D, Cookston JT, Fabricius WV. Relations between mattering to step- and non-residential fathers and adolescent mental health. Fathering. 2009;7:70–90. doi: 10.3149/fth.0701.70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoppe-Sullivan S, McBride BA, Ho M. Unidimensional versus multidimensional perspectives on father involvement. Fathering. 2004;2:147–164. doi: 10.3149/fth.0202.147. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg L, Darling N, Fletcher AC. Authoritative parenting and adolescent adjustment: An ecological journey. In: Moen P, Elder GH Jr, Luscher K, editors. Examining lives in context: Perspectives on the ecology of human development. Washington, DC: American Psychological; 1995. pp. 423–466. [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg L, Dornbusch SM, Brown BB. Ethnic differences in adolescent achievement: An ecological perspective. American Psychologist. 1992;47:723–729. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.47.6.723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg L, Mounts NS, Lamborn SD, Dornbusch SM. Authoritative parenting and adolescent adjustment across varied ecological niches. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 1991;1:19–36. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor B, Behnke A. Fathering across the border: Latino fathers in Mexico and the U.S. Fathering. 2005;3:1–24. doi: 10.3149/fth.0302.99. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Varela RE, Vernberg EM, Sanchez-Sosa JJ, Riveros A, Mitchell M, Mashunkashey J. Parenting style of Mexican, Mexican American, and Caucasian-Non-Hispanic families: Social context and cultural influences. Journal of Family Psychology. 2004;18:651–657. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.18.4.651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vazsonyi AT, Belliston LM. The cultural and developmental significance of parenting processes in adolescent anxiety and depression symptoms. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2006;35:491–505. doi: 10.1007/s10964-006-9064-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau. 2008 American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates. US Census Bureau News. 2010 Retrieved May 6, 2010, from http://www.census.gov/Press-Release/www/releases/pdf/cb10ff-08_cincodemayo.pdf.

- Yoshikawa H, Weisner TS, Kalil A, Way N. Mixing Qualitative and Quantitative Research in Developmental Science: Uses and Methodological Choices. Developmental Psychology. 2008;44(2):344–354. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.44.2.344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]