Abstract

Objectives. We describe the burden of unintentional injury (UI) deaths among American Indian and Alaska Native (AI/AN) populations in the United States.

Methods. National Death Index records for 1990 to 2009 were linked with Indian Health Service registration records to identify AI/AN deaths misclassified as non-AI/AN deaths. Most analyses were restricted to Contract Health Service Delivery Area counties in 6 geographic regions of the United States. We compared age-adjusted death rates for AI/AN persons with those for Whites; Hispanics were excluded.

Results. From 2005 to 2009, the UI death rate for AI/AN people was 2.4 times higher than for Whites. Death rates for the 3 leading causes of UI death—motor vehicle traffic crashes, poisoning, and falls—were 1.4 to 3 times higher among AI/AN persons than among Whites. UI death rates were higher among AI/AN males than among females and highest among AI/AN persons in Alaska, the Northern Plains, and the Southwest.

Conclusions. AI/AN persons had consistently higher UI death rates than did Whites. This disparity in overall rates coupled with recent increases in unintentional poisoning deaths requires that injury prevention be a major priority for improving health and preventing death among AI/AN populations.

Unintentional injuries (UIs) were the leading cause of death for people aged 1 to 44 years and the fifth leading cause of death for infants and all age groups combined in the United States.1 Numerous studies have shown that American Indians and Alaska Natives (AI/ANs) have been disproportionately affected by unintentional injury, the third leading cause of death in this population.1–5 Although UI death rates among the AI/AN population in Indian Health Service (IHS) areas decreased nearly 60% in the last 3 decades of the 20th century, disparities between AI/AN and White populations persisted.3 From 2002 to 2004, the AI/AN unintentional injury death rate was 2.5 times higher than that for Whites.5

The disparity may be even more pronounced because AI/AN race is frequently misreported on death certificates. An evaluation of the quality of reporting of race on death certificates performed by the National Center for Health Statistics indicated that AI/AN race is underreported in national mortality data by approximately 21%.6 Another study that linked state death certificates with IHS patient registration files showed that approximately 9% of AI/AN persons who died from 1996 to 1998 were incorrectly classified.7

We added to the current literature by updating UI death rates among AI/AN people from 2005 to 2009 by IHS Contract Health Service Delivery Areas (CHSDAs), injury mechanism, sex, and age. Furthermore, we provide more accurate rates by race through linkage of death records with IHS registration records and describe UI death trends from 1990 to 2009. Improved quality of surveillance data for UI deaths will better inform public health strategies to reduce and prevent UIs among the AI/AN population.

METHODS

Description of the methods for generating the analytic death files are described in detail elsewhere in this supplement.8

Population Estimates

Bridged single-race population estimates developed by the US Census Bureau and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Center for Health Statistics are included as denominators in the calculation of death rates.8 Bridged single-race data allow for comparability between the pre- and post-2000 racial/ethnic population estimates during this study period. The bridging method takes responses to the 2000 Census’s questions on race and reclassifies them to approximate the responses individuals would hypothetically have given using the old single-race categories.8

During preliminary analyses, it was discovered that the updated bridged intercensal population estimates significantly overestimated AI/AN persons of Hispanic origin. Therefore, to avoid underestimating mortality in AI/AN people, analyses are limited to non-Hispanic AI/AN persons.9 Non-Hispanic Whites were chosen as the most homogeneous referent group. For conciseness, the term “non-Hispanic” is omitted when discussing both groups.

Death Records

Death certificate data were obtained from the National Center for Health Statistics’ National Vital Statistics System mortality file. Bridged, single-race deaths of AI/AN persons were determined for the entire study period, 1990 to 2009, using methods described elsewhere.8 AI/AN race was based on the death certificate and information derived from data linkages between the IHS patient registration database and the National Death Index.

After the linkage of IHS patient registration data with the National Death Index, the state death certificate number and year of death of IHS clients were returned to the National Center for Health Statistics and merged with the National Vital Statistics System mortality file. This linkage with the National Death Index (indicating a positive link to IHS patient registration data) allowed for an additional indicator of AI/AN ancestry in the National Vital Statistics System mortality file. A flag indicating a positive link to IHS was added as an additional indicator of AI/AN ancestry. This file was combined with the population estimates to create an analytic file in SEER*Stat (AI/AN Mortality Database [1999–2009]; National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD). The analytic file was used by collaborators for this supplement and includes all deaths for all races reported to the National Center for Health Statistics from 1990 to 2009.10

We categorized the underlying cause of injury death using the external-cause-of-injury mortality matrix of the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9)11 for deaths from 1990 to 1998 and the International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision (ICD-10)12 for deaths from 1999 to 2009. The ICD-9 external-cause-of-injury codes were modified to be consistent with the ICD-10 classification13 (Table A, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org).

Geographic Coverage

We created most of the tabulations in this article by restricting analyses to the 637 counties designated as IHS CHSDA counties, which in general contain federally recognized tribal lands or are adjacent to tribal lands. CHSDA counties are described in more detail elsewhere.8 Although less geographically representative, analyses restricted to CHSDA counties offer improved accuracy in interpreting death statistics for AI/AN persons. CHSDA counties have a higher proportion of AI/AN individuals than non-CHSDA counties, with approximately 56% of the AI/AN population residing in these designated counties.

We completed analyses for all US regions combined, all IHS regions combined, and by each of the 6 individual IHS regions: Alaska, Pacific Coast, Northern Plains, Southern Plains, Southwest, and the East (Table 1 provides a definition of the regions).8 Identical or similar regional analyses have been used for other health-related publications focusing on AI/AN persons.8 Additionally, we found this approach to be preferable to using smaller jurisdictions, such as the administrative areas defined by IHS, which yielded less stable estimates.8

TABLE 1—

Overall Unintentional Injury Deaths, Rates, and Rate Ratios by Indian Health Service Region and Sex for American Indians/Alaska Natives and Whites: United States, 2005–2009

| CHSDA Counties |

All Counties |

|||||||||

| IHS Region | AI/AN Count | AI/AN Rate | White Count | White Rate | RR (95% CI) | AI/AN Count | AI/AN Rate | White Count | White Rate | RR (95% CI) |

| Northern Plains | ||||||||||

| Total | 1 449 | 118.38 | 17 044 | 39.60 | 2.99* (2.82, 3.17) | 1 797 | 92.48 | 77 340 | 37.65 | 2.46* (2.33, 2.59) |

| Male | 951 | 161.31 | 10 583 | 54.09 | 2.98* (2.76, 3.22) | 1 179 | 125.83 | 47 857 | 51.71 | 2.43* (2.27, 2.61) |

| Female | 498 | 80.22 | 6 461 | 26.26 | 3.06* (2.76, 3.37) | 618 | 62.90 | 29 483 | 24.80 | 2.54* (2.32, 2.76) |

| Alaska | ||||||||||

| Total | 595 | 122.59 | 975 | 44.84 | 2.73* (2.44, 3.06) | 595 | 122.59 | 975 | 44.84 | 2.73* (2.44, 3.06) |

| Male | 408 | 165.85 | 713 | 61.76 | 2.69* (2.34, 3.08) | 408 | 165.85 | 713 | 61.76 | 2.69* (2.34, 3.08) |

| Female | 187 | 78.97 | 262 | 26.29 | 3.00* (2.45, 3.68) | 187 | 78.97 | 262 | 26.29 | 3.00* (2.45, 3.68) |

| Southern Plains | ||||||||||

| Total | 1 512 | 99.61 | 8 742 | 56.07 | 1.78* (1.68, 1.88) | 1 747 | 86.53 | 42 615 | 49.04 | 1.76* (1.68, 1.86) |

| Male | 980 | 133.05 | 5 450 | 74.87 | 1.78* (1.65, 1.91) | 1 128 | 113.81 | 26 479 | 65.68 | 1.73* (1.62, 1.85) |

| Female | 532 | 68.74 | 3 292 | 38.39 | 1.79* (1.63, 1.97) | 619 | 60.55 | 16 136 | 33.40 | 1.81* (1.67, 1.97) |

| Southwest | ||||||||||

| Total | 2 471 | 115.52 | 18 385 | 50.49 | 2.29* (2.19, 2.39) | 2 582 | 109.97 | 29 047 | 47.02 | 2.34* (2.24, 2.44) |

| Male | 1 767 | 173.89 | 11 276 | 65.58 | 2.65* (2.51, 2.80) | 1 830 | 162.82 | 17 763 | 61.05 | 2.67* (2.53, 2.81) |

| Female | 704 | 64.02 | 7 109 | 35.67 | 1.79* (1.65, 1.95) | 752 | 62.80 | 11 284 | 33.47 | 1.88* (1.73, 2.03) |

| Pacific Coast | ||||||||||

| Total | 1 191 | 92.01 | 32 212 | 41.73 | 2.20* (2.07, 2.34) | 1 454 | 77.75 | 54 669 | 38.42 | 2.02* (1.91, 2.14) |

| Male | 750 | 118.59 | 20 185 | 56.19 | 2.11* (1.95, 2.29) | 920 | 100.38 | 34 616 | 51.97 | 1.93* (1.80, 2.07) |

| Female | 441 | 67.33 | 12 027 | 28.05 | 2.40* (2.17, 2.65) | 534 | 56.48 | 20 053 | 25.52 | 2.21* (2.02, 2.42) |

| East | ||||||||||

| Total | 313 | 61.70 | 32 054 | 42.27 | 1.46* (1.29, 1.64) | 1 081 | 39.04 | 255 591 | 43.54 | 0.90* (0.84, 0.95) |

| Male | 206 | 83.51 | 20 024 | 58.13 | 1.44* (1.23, 1.67) | 739 | 55.05 | 160 587 | 59.86 | 0.92* (0.85, 1.00) |

| Female | 107 | 41.62 | 12 030 | 27.62 | 1.51* (1.23, 1.83) | 342 | 24.48 | 95 004 | 28.45 | 0.86* (0.77, 0.96) |

| Total US | ||||||||||

| Total | 7 531 | 105.01 | 109 412 | 43.70 | 2.40* (2.34, 2.46) | 9 256 | 80.75 | 460 237 | 42.38 | 1.91* (1.86, 1.95) |

| Male | 5 062 | 145.94 | 68 231 | 58.99 | 2.47* (2.40, 2.55) | 6 204 | 111.19 | 288 015 | 57.79 | 1.92* (1.87, 1.98) |

| Female | 2 469 | 67.68 | 41 181 | 29.31 | 2.31* (2.21, 2.41) | 3 052 | 52.66 | 172 222 | 28.04 | 1.88* (1.81, 1.95) |

Note. AI/AN = American Indian/Alaska Native; CHSDA = Contract Health Service Delivery Areas; CI = confidence interval; IHS = Indian Health Service; RR = rate ratio. Analyses are limited to people of non-Hispanic origin. AI/AN race is reported from death certificates or through linkage with the IHS patient registration database. Rates are per 100 000 people and were age adjusted to the 2000 US standard population (11 age groups; Census P25-1130). RRs are calculated in SEER*Stat before rounding of rates and may not equal RRs calculated from rates presented in table. IHS regions are defined as follows: AKa; Northern Plains (IL, IN,a IA,a MI,a MN,a MT,a NE,a ND,a SD,a WI,a WYa); Southern Plains (OK,a KS,a TXa); Southwest (AZ,a CO,a NV,a NM,a UTa); Pacific Coast (CA,a ID,a OR,a WA,a HI); East (AL,a AR, CT,a DE, FL,a GA, KY, LA,a ME,a MD, MA,a MS,a MO, NH, NJ, NY,a NC,a OH, PA,a RI,a SC,a TN, VT, VA, WV, DC). Percentage of regional coverage of AI/AN persons in CHSDA counties to AI/AN persons in all counties: Northern Plains = 64.8%; Alaska = 100%; Southern Plains = 76.3%; Southwest = 91.3%; Pacific Coast = 71.3%; East = 18.2%; and total US = 64.2%.

Source. AI/AN Mortality Database (1990–2009).

Identifies states with ≥ 1 county designated as CHSDA.

*P < .05.

Statistical Methods

Age-adjusted rates, expressed per 100 000 population, were directly adjusted to the 2000 US standard population using SEER*Stat software (version 8.0.4; National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD).14 We calculated standardized rate ratios (RRs) using age-adjusted death rates and White people as the comparison group and RRs and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for age-adjusted rates on the basis of methods described by Tiwari et al. using SEER*Stat 7.0.9.15 Temporal changes in annual age-adjusted death rates, including the annual percentage change for each interval, were assessed with Joinpoint regression techniques16 (version 4.0.1; National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD).

RESULTS

We used UI death rates, RRs, and 95% CIs to demonstrate the region, sex, and age-specific variations for the time period 2005 to 2009. Leading causes of UI deaths analyzed included motor vehicle traffic (MVT) crashes, unintentional poisoning, and fall deaths.

From 2005 to 2009, the UI death rate for AI/AN persons in all US counties was 80.8, 1.9 times higher than the rate of 42.4 for Whites (Table 1; for full rates and CIs, see Table B, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org). This disparity in UI death rates between AI/AN and White populations was even higher in CHSDA counties than in all US counties combined (RR = 2.4). Because there were more appreciable differences in AI/AN rates in CHSDA counties, likely because of improved racial classification, the remainder of the results focus on UI death among residents of CHSDA counties unless otherwise noted.

UI death rates were significantly higher among AI/AN persons than among Whites across all IHS regions; RRs ranged from a low of 1.5 in the East to a high of 3.0 in the Northern Plains. We also found regional variations in UI death rates among the AI/AN population. The rates were highest in Alaska (122.6), followed by the Northern Plains (118.4) and the Southwest (115.5), and UI death rates for AI/AN persons in these regions were higher than death rates for AI/AN persons in the Pacific Coast and East and in the United States as a whole (Table 1, Table B). Rates of UI death among AI/AN males were approximately 2 times higher than among AI/AN females (Table 1, Table B).

Motor Vehicle Traffic

Although MVT death rates decreased for AI/AN and White persons from 1990 to 2009 (Table C, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org), the largest percentage of UI deaths were still attributed to MVT injuries among AI/AN (43.7%) and White persons (28.8%) for 2005 to 2009 (Table 2). The MVT death rate for AI/AN persons (41.8) was more than 3 times the rate for Whites (13.4) from 2005 to 2009. MVT deaths were the leading cause of UI death among AI/AN persons in all IHS regions, except in Alaska, where the rate of unintentional poisoning death was almost twice the rate of MVT crash death. The largest number of MVT crash deaths for AI/AN persons (n = 1213) was in the Southwest, accounting for 36.9% of total MVT deaths for AI/AN persons in CHSDA counties.

TABLE 2—

Leading Causes of Unintentional Injury Deaths by Indian Health Service Region for American Indians/Alaska Natives Compared With Whites for All Ages: Contract Health Service Delivery Area Counties, United States, 2005–2009

| AI/AN |

White |

AAPCa |

|||||

| Cause of Death/IHS Region | Count | Rate (95% CI) | Count | Rate (95% CI) | AI/AN:White RR (95% CI) | AI/AN | White |

| All unintentional injuries | |||||||

| Northern Plains | 1449 | 118.38 (111.75, 125.31) | 17 044 | 39.60 (38.99, 40.21) | 2.99* (2.82, 3.17) | −0.45 | −0.17 |

| Alaska | 595 | 122.59 (112.10, 133.80) | 975 | 44.84 (41.89, 47.95) | 2.73* (2.44, 3.06) | 4.00 | 1.30 |

| Southern Plains | 1512 | 99.61 (94.40, 105.03) | 8742 | 56.07 (54.88, 57.28) | 1.78* (1.68, 1.88) | −0.43 | 2.84 |

| Southwest | 2471 | 115.52 (110.73, 120.47) | 18 385 | 50.49 (49.75, 51.24) | 2.29* (2.19, 2.39) | −2.62 | −1.42 |

| Pacific Coast | 1191 | 92.01 (86.57, 97.71) | 32 212 | 41.73 (41.27, 42.20) | 2.20* (2.07, 2.34) | 1.28 | 0.10 |

| East | 313 | 61.70 (54.76 69.30) | 32 054 | 42.27 (41.80, 42.75) | 1.46* (1.29, 1.64) | −9.56 | −0.32 |

| Total | 7531 | 105.01 (102.50, 107.57) | 109 412 | 43.70 (43.43, 43.96) | 2.40* (2.34, 2.46) | −0.98 | −0.08 |

| Motor vehicle traffic | |||||||

| Northern Plains | 724 | 54.55 (50.36, 59.01) | 5458 | 13.47 (13.11, 13.83) | 4.05* (3.72, 4.40) | −5.57 | −6.91b |

| Alaska | 93 | 17.42 (13.91, 21.60) | 234 | 10.11 (8.81, 11.55) | 1.72* (1.32, 2.23) | 9.34 | −14.41b |

| Southern Plains | 618 | 36.70 (33.77, 39.84) | 2938 | 19.51 (18.80, 20.24) | 1.88* (1.72, 2.06) | −3.41 | −3.83b |

| Southwest | 1213 | 51.28 (48.32, 54.38) | 4978 | 14.25 (13.85, 14.66) | 3.60* (3.37, 3.84) | −10.83b | −10.86b |

| Pacific Coast | 497 | 35.87 (32.69, 39.29) | 8486 | 11.72 (11.46, 11.97) | 3.06* (2.78, 3.36) | −6.25b | −8.43b |

| East | 143 | 26.58 (22.33, 31.46) | 9389 | 13.39 (13.11, 13.67) | 1.99* (1.67, 2.35) | −11.19 | −6.26 |

| Total | 3288 | 41.83 (40.36, 43.35) | 31 483 | 13.36 (13.21, 13.51) | 3.13* (3.02, 3.25) | −7.25 | −7.51b |

| Poisoning | |||||||

| Northern Plains | 273 | 22.36 (19.69, 25.33) | 2825 | 7.29 (7.02, 7.57) | 3.07* (2.68, 3.49) | 13.44b | 11.40b |

| Alaska | 169 | 33.76 (28.75, 39.44) | 303 | 12.11 (10.76, 13.60) | 2.79* (2.28, 3.40) | 28.40b | 20.03b |

| Southern Plains | 455 | 29.16 (26.51, 32.01) | 2230 | 15.41 (14.77, 16.08) | 1.89* (1.70, 2.10) | 11.79 | 13.19b |

| Southwest | 395 | 17.55 (15.83, 19.42) | 5068 | 15.12 (14.70, 15.55) | 1.16* (1.04, 1.29) | 24.69b | 8.18b |

| Pacific Coast | 370 | 27.05 (24.33, 30.00) | 8951 | 12.29 (12.04, 12.56) | 2.20* (1.97, 2.45) | 7.28 | 8.72b |

| East | 76 | 14.01 (11.02, 17.63) | 8418 | 12.37 (12.11, 12.65) | 1.13 (0.89, 1.43) | 3.58 | 6.86b |

| Total | 1738 | 23.33 (22.23, 24.48) | 27 795 | 12.06 (11.92, 12.21) | 1.93* (1.84, 2.03) | 15.21b | 8.81b |

| Falls | |||||||

| Northern Plains | 115 | 13.46 (10.82, 16.51) | 4468 | 9.01 (8.75, 9.29) | 1.49* (1.20, 1.84) | −0.43 | 3.28b |

| Alaska | 22 | 6.60 (3.93, 10.26) | 89 | 5.54 (4.38, 6.91) | 1.19 (0.68, 1.97) | 19.23 | 1.50 |

| Southern Plains | 103 | 10.15 (8.20, 12.39) | 1230 | 6.83 (6.45, 7.22) | 1.49* (1.19, 1.83) | 0.57 | 7.60b |

| Southwest | 229 | 15.79 (13.69, 18.09) | 4750 | 11.40 (11.07, 11.73) | 1.39* (1.20, 1.59) | 9.80 | 0.67 |

| Pacific Coast | 76 | 9.65 (7.44, 12.24) | 7748 | 8.65 (8.46, 8.85) | 1.12 (0.86, 1.42) | 15.08b | 5.50b |

| East | 21 | 6.39 (3.80, 9.93) | 6336 | 6.77 (6.61, 6.95) | 0.94 (0.56, 1.47) | −26.46b | 5.90b |

| Total | 566 | 11.90 (10.86, 12.99) | 24 621 | 8.36 (8.26, 8.47) | 1.42* (1.30, 1.56) | 5.73b | 4.39b |

| Suffocation | |||||||

| Northern Plains | 62 | 4.26 (3.12, 5.72) | 750 | 1.73 (1.60, 1.86) | 2.47* (1.79, 3.35) | −5.98 | −1.85 |

| Alaska | 35 | 5.77 (3.72, 8.57) | 47 | 2.46 (1.76, 3.34) | 2.34* (1.36, 3.98) | 25.30 | −4.07 |

| Southern Plains | 40 | 2.86 (1.98, 3.99) | 334 | 1.99 (1.78, 2.22) | 1.44 (0.98, 2.05) | −14.92 | −4.34 |

| Southwest | 92 | 5.16 (4.09, 6.41) | 706 | 1.86 (1.73, 2.01) | 2.77* (2.16, 3.49) | −3.22 | 2.57 |

| Pacific Coast | 47 | 3.41 (2.47, 4.61) | 1254 | 1.60 (1.51, 1.70) | 2.13* (1.54, 2.90) | 5.06 | 0.55 |

| East | 10 | 1.84 (0.82, 3.59) | 1952 | 2.35 (2.24, 2.46) | 0.78 (0.35, 1.53) | — | −3.32 |

| Total | 286 | 4.04 (3.54, 4.60) | 5043 | 1.93 (1.87, 1.98) | 2.10* (1.83, 2.39) | −3.88 | −1.54 |

| Drowning | |||||||

| Northern Plains | 44 | 2.98 (2.14, 4.10) | 353 | 0.91 (0.81, 1.01) | 3.29* (2.32, 4.62) | 1.37 | −4.56b |

| Alaska | 66 | 12.60 (9.64, 16.24) | 50 | 2.05 (1.50, 2.75) | 6.14* (4.10, 9.23) | −12.10 | 10.65 |

| Southern Plains | 35 | 2.09 (1.44, 2.95) | 239 | 1.67 (1.46, 1.89) | 1.26 (0.84, 1.82) | −5.19 | 8.40 |

| Southwest | 63 | 2.58 (1.96, 3.34) | 424 | 1.27 (1.15, 1.40) | 2.04* (1.52, 2.70) | 15.84b | −0.14 |

| Pacific Coast | 54 | 3.88 (2.90, 5.12) | 1009 | 1.43 (1.35, 1.53) | 2.71* (2.01, 3.60) | −5.81 | −4.19 |

| East | 13 | 2.47 (1.30, 4.34) | 774 | 1.09 (1.01, 1.17) | 2.27* (1.18, 4.00) | −8.01 | 0.66 |

| Total | 275 | 3.46 (3.05, 3.91) | 2849 | 1.24 (1.19, 1.29) | 2.79* (2.45, 3.17) | −1.72 | −1.01 |

| Fire/burn | |||||||

| Northern Plains | 44 | 3.20 (2.27, 4.43) | 412 | 0.97 (0.88, 1.07) | 3.29* (2.30, 4.64) | −18.04 | −1.00 |

| Alaska | 23 | 4.85 (2.89, 7.63) | 34 | 1.56 (1.05, 2.22) | 3.11* (1.64, 5.73) | −27.33b | −3.86 |

| Southern Plains | 52 | 3.47 (2.56, 4.60) | 293 | 1.79 (1.59, 2.02) | 1.93* (1.39, 2.63) | −22.18 | −0.77 |

| Southwest | 39 | 1.84 (1.27, 2.57) | 291 | 0.76 (0.67, 0.85) | 2.43* (1.65, 3.49) | −29.50b | −11.13 |

| Pacific Coast | 20 | 1.79 (1.04, 2.84) | 579 | 0.72 (0.66, 0.79) | 2.47* (1.43, 3.97) | 6.41 | −10.27 |

| East | c | 0.57 (0.12, 1.80) | 727 | 0.94 (0.87, 1.01) | 0.61 (0.12, 1.92) | — | −3.64 |

| Total | 181 | 2.55 (2.17, 2.98) | 2336 | 0.91 (0.88, 0.95) | 2.79* (2.36, 3.28) | −19.33 | −5.48b |

Note. AI/AN = American Indian/Alaska Native; AAPC = average annual percentage change; CHSDA = Contract Health Service Delivery Areas; CI = confidence interval; IHS = Indian Health Service; RR = rate ratio. Analyses are limited to persons of non-Hispanic origin. Dash indicates AAPC could not be calculated. AI/AN race is reported from death certificates or through linkage with the IHS patient registration database. Rates are per 100 000 people and were age adjusted to the 2000 US standard population (11 age groups; Census P25-1130). RRs were calculated in SEER*Stat before rounding of rates and may not equal RRs calculated from rates presented in table. IHS regions are defined as follows: AKd; Northern Plains (IL, IN,d IA,d MI,d MN,d MT,d NE,d ND,d SD,d WI,d WYd); Southern Plains (OK,d KS,d TXd); Southwest (AZ,d CO,d NV,d NM,d UTd); Pacific Coast (CA,d ID,d OR,d WA,d HI); East (AL,d AR, CT,d DE, FL,d GA, KY, LA,d ME,d MD, MA,d MS,d MO, NH, NJ, NY,d NC,d OH, PA,d RI,d SC,d TN, VT, VA, WV, DC). Percentage regional coverage of AI/AN persons in CHSDA counties to AI/AN persons in all counties: Northern Plains = 64.8%; Alaska = 100%; Southern Plains = 76.3%; Southwest = 91.3%; Pacific Coast = 71.3%; East = 18.2%; and total US = 64.2%.

Source. AI/AN Mortality Database (1990–2009).

Calculated in Joinpoint.

Significantly different from zero at α = 0.05.

Counts < 10 are suppressed; if no cases reported, then rates and RRs could not be calculated.

Identifies states with ≥ 1 county designated as CHSDA.

*P < .05.

MVT death rates were 2 times higher in AI/AN males than in AI/AN females (Table 3). Rates of MVT death among AI/AN persons were the highest in adults aged 25 to 34 years (67.6), followed by adolescents and young adults aged 15 to 24 years (65.9). MVT death rates in AI/AN persons decreased in each subsequent age group from 25 to 34 years through 65 to 74 years. Rates among older AI/AN adults were higher than rates among AI/AN children aged 0 to 14 years. The greatest disparity between AI/AN and White people was among infants aged younger than 1 year (RR = 8.3). AI/AN children aged 1 to 4 years (RR = 4.8) and adults aged 25 to 34 years (RR = 4.1) also had death rates substantially higher than those of Whites of the same age. AI/AN MVT pedestrian death rates increased gradually with age from 15 to 24 years to a peak rate of 11.1 among people 45 to 54 years (Table 3). We found significant disparities in MVT pedestrian deaths by age group between AI/AN and White people, with an RR of 5.1 for children aged 1 to 4 years and RRs for adolescents and adults aged 15 to 74 years ranging from 7.8 in people aged 25 to 34 years to 2.6 in people aged 65 to 74 years.

TABLE 3—

Unintentional Injury Deaths and Death Rates by Injury Mechanism, Sex, and Age Group for American Indians/Alaska Natives and Whites: Contract Health Service Delivery Area Counties, United States, 2005–2009

| AI/AN |

White |

||||

| Injury Mechanism/Demographic Category | Count | Rate (95% CI) | Count | Rate (95% CI) | AI/AN:White RR (95% CI) |

| Total unintentional injuries | |||||

| Total | 7531 | 105.01 (102.50, 107.57) | 109 412 | 43.70 (43.43, 43.96) | 2.40* (2.34, 2.46) |

| Male | 5062 | 145.94 (141.55, 150.44) | 68 231 | 58.99 (58.54, 59.44) | 2.47* (2.40, 2.55) |

| Female | 2469 | 67.68 (64.92, 70.54) | 41 181 | 29.31 (29.01, 29.60) | 2.31* (2.21, 2.41) |

| 0 y | 122 | 78.29 (65.01, 93.48) | 646 | 26.24 (24.26, 28.34) | 2.98* (2.44, 3.63) |

| 1–4 y | 162 | 28.35 (24.15, 33.06) | 926 | 9.32 (8.73, 9.95) | 3.04* (2.56, 3.60) |

| 5–14 y | 203 | 14.02 (12.16, 16.09) | 1374 | 5.20 (4.92, 5.48) | 2.70* (2.32, 3.13) |

| 15–24 y | 1479 | 99.54 (94.53, 104.75) | 11 113 | 37.26 (36.57, 37.96) | 2.67* (2.53, 2.82) |

| 25–34 y | 1414 | 132.46 (125.64, 139.55) | 10 907 | 40.72 (39.96, 41.50) | 3.25* (3.08, 3.44) |

| 35–44 y | 1406 | 134.14 (127.22, 141.34) | 13 873 | 44.97 (44.22, 45.72) | 2.98* (2.82, 3.15) |

| 45–54 y | 1280 | 125.32 (118.54, 132.37) | 18 809 | 52.56 (51.81, 53.32) | 2.38* (2.25, 2.52) |

| 55–64 y | 616 | 92.55 (85.39, 100.16) | 11 785 | 39.75 (39.04, 40.48) | 2.33* (2.14, 2.52) |

| 65–74 y | 363 | 103.72 (93.33, 114.96) | 8379 | 45.57 (44.60, 46.55) | 2.28* (2.04, 2.53) |

| 75–84 y | 307 | 196.08 (174.76, 219.29) | 13 913 | 111.87 (110.02, 113.75) | 1.75* (1.56, 1.96) |

| ≥ 85 y | 179 | 395.39 (339.59, 457.74) | 17 687 | 353.51 (348.32, 358.76) | 1.12 (0.96, 1.30) |

| Motor vehicle traffic, total | |||||

| Total | 3288 | 41.83 (40.36, 43.35) | 31 483 | 13.36 (13.21, 13.51) | 3.13* (3.02, 3.25) |

| Male | 2149 | 56.35 (53.85, 58.94) | 21 899 | 18.99 (18.74, 19.25) | 2.97* (2.83, 3.11) |

| Female | 1139 | 28.29 (26.62, 30.04) | 9584 | 7.91 (7.75, 8.07) | 3.58* (3.35, 3.81) |

| 0 y | 23 | 14.76 (9.36, 22.15) | 44 | 1.79 (1.30, 2.40) | 8.26* (4.76, 13.98) |

| 1–4 y | 57 | 9.97 (7.55, 12.92) | 205 | 2.06 (1.79, 2.37) | 4.83* (3.54, 6.51) |

| 5–14 y | 98 | 6.77 (5.50, 8.25) | 676 | 2.56 (2.37, 2.76) | 2.65* (2.12, 3.28) |

| 15–24 y | 979 | 65.89 (61.83, 70.15) | 6723 | 22.54 (22.01, 23.09) | 2.92* (2.73, 3.13) |

| 25–34 y | 722 | 67.63 (62.79, 72.75) | 4411 | 16.47 (15.99, 16.96) | 4.11* (3.79, 4.44) |

| 35–44 y | 563 | 53.71 (49.37, 58.34) | 4302 | 13.94 (13.53, 14.37) | 3.85* (3.52, 4.21) |

| 45–54 y | 435 | 42.59 (38.68, 46.78) | 5222 | 14.59 (14.20, 14.99) | 2.92* (2.64, 3.22) |

| 55–64 y | 222 | 33.35 (29.11, 38.04) | 3802 | 12.83 (12.42, 13.24) | 2.60* (2.26, 2.98) |

| 65–74 y | 110 | 31.43 (25.83, 37.88) | 2497 | 13.58 (13.05, 14.12) | 2.31* (1.89, 2.80) |

| 75–84 y | 68 | 43.43 (33.73, 55.06) | 2428 | 19.52 (18.75, 20.32) | 2.22* (1.72, 2.83) |

| ≥ 85 y | 11 | 24.30 (12.13, 43.48) | 1173 | 23.44 (22.12, 24.83) | 1.04 (0.52, 1.86) |

| Motor vehicle traffic, occupant | |||||

| Total | 1240 | 15.49 (14.60, 16.42) | 11 161 | 4.75 (4.66, 4.84) | 3.26* (3.06, 3.47) |

| Male | 774 | 19.99 (18.51, 21.57) | 7402 | 6.46 (6.31, 6.61) | 3.09* (2.86, 3.35) |

| Female | 466 | 11.34 (10.30, 12.46) | 3759 | 3.11 (3.01, 3.22) | 3.64* (3.29, 4.02) |

| 0 y | 15 | 9.63 (5.39, 15.88) | 22 | 0.89 (0.56, 1.35) | 10.77* (5.20, 21.73) |

| 1–4 y | 15 | 2.62 (1.47, 4.33) | 74 | 0.75 (0.59, 0.94) | 3.52* (1.88, 6.19) |

| 5–14 y | 35 | 2.42 (1.68, 3.36) | 243 | 0.92 (0.81, 1.04) | 2.63* (1.79, 3.76) |

| 15–24 y | 435 | 29.28 (26.59, 32.16) | 2673 | 8.96 (8.63, 9.31) | 3.27* (2.94, 3.62) |

| 25–34 y | 267 | 25.01 (22.10, 28.20) | 1568 | 5.85 (5.57, 6.15) | 4.27* (3.74, 4.87) |

| 35–44 y | 189 | 18.03 (15.55, 20.79) | 1419 | 4.60 (4.36, 4.85) | 3.92* (3.35, 4.57) |

| 45–54 y | 131 | 12.83 (10.72, 15.22) | 1607 | 4.49 (4.27, 4.72) | 2.86* (2.37, 3.41) |

| 55–64 y | 81 | 12.17 (9.66, 15.13) | 1242 | 4.19 (3.96, 4.43) | 2.90* (2.29, 3.64) |

| 65–74 y | 41 | 11.72 (8.41, 15.89) | 896 | 4.87 (4.56, 5.20) | 2.40* (1.71, 3.29) |

| 75–84 y | 27 | 17.25 (11.36, 25.09) | 944 | 7.59 (7.11, 8.09) | 2.27* (1.49, 3.33) |

| ≥ 85 y | a | 8.84 (2.41, 22.62) | 473 | 9.45 (8.62, 10.35) | 0.93 (0.25, 2.41) |

| Motor vehicle traffic, pedestrian | |||||

| Total | 520 | 6.80 (6.21, 7.43) | 3096 | 1.28 (1.23, 1.32) | 5.32* (4.83, 5.86) |

| Male | 396 | 10.69 (9.63, 11.85) | 2159 | 1.84 (1.76, 1.92) | 5.81* (5.19, 6.50) |

| Female | 124 | 3.17 (2.63, 3.80) | 937 | 0.75 (0.70, 0.80) | 4.24* (3.47, 5.15) |

| 0 y | a | a | a | a | a |

| 1–4 y | 15 | 2.62 (1.47, 4.33) | 51 | 0.51 (0.38, 0.68) | 5.11* (2.67, 9.23) |

| 5–14 y | a | 0.55 (0.24, 1.09) | 104 | 0.39 (0.32, 0.48) | 1.41 (0.59, 2.87) |

| 15–24 y | 107 | 7.20 (5.90, 8.70) | 367 | 1.23 (1.11, 1.36) | 5.85* (4.67, 7.28) |

| 25–34 y | 100 | 9.37 (7.62, 11.39) | 323 | 1.21 (1.08, 1.34) | 7.77* (6.14, 9.75) |

| 35–44 y | 110 | 10.49 (8.63, 12.65) | 440 | 1.43 (1.30, 1.57) | 7.36* (5.92, 9.09) |

| 45–54 y | 113 | 11.06 (9.12, 13.30) | 611 | 1.71 (1.57, 1.85) | 6.48* (5.25, 7.93) |

| 55–64 y | 43 | 6.46 (4.68, 8.70) | 446 | 1.50 (1.37, 1.65) | 4.29* (3.06, 5.88) |

| 65–74 y | 15 | 4.29 (2.40, 7.07) | 307 | 1.67 (1.49, 1.87) | 2.57* (1.42, 4.30) |

| 75–84 y | a | 5.11 (2.21, 10.07) | 309 | 2.48 (2.22, 2.78) | 2.06 (0.88, 4.10) |

| ≥ 85 y | a | 2.21 (0.06, 12.31) | 138 | 2.76 (2.32, 3.26) | 0.80 (0.02, 4.54) |

| Poisoning | |||||

| Total | 1738 | 23.33 (22.23, 24.48) | 27 795 | 12.06 (11.92, 12.21) | 1.93* (1.84, 2.03) |

| Male | 1120 | 30.65 (28.84, 32.56) | 17 528 | 15.42 (15.19, 15.66) | 1.99* (1.87, 2.11) |

| Female | 618 | 16.40 (15.12, 17.77) | 10 267 | 8.65 (8.48, 8.83) | 1.90* (1.74, 2.06) |

| 0 y | a | 1.28 (0.16, 4.64) | 12 | 0.49 (0.25, 0.85) | 2.63 (0.29, 11.83) |

| 1–4 y | a | 1.05 (0.39, 2.29) | 10 | 0.10 (0.05, 0.19) | 10.43* (3.11, 31.66) |

| 5–14 y | a | 0.55 (0.24, 1.09) | 51 | 0.19 (0.14, 0.25) | 2.87* (1.17, 6.08) |

| 15–24 y | 217 | 14.60 (12.73, 16.68) | 2666 | 8.94 (8.60, 9.29) | 1.63* (1.42, 1.88) |

| 25–34 y | 393 | 36.82 (33.26, 40.64) | 4756 | 17.76 (17.26, 18.27) | 2.07* (1.87, 2.30) |

| 35–44 y | 467 | 44.55 (40.60, 48.79) | 6846 | 22.19 (21.67, 22.72) | 2.01* (1.82, 2.21) |

| 45–54 y | 469 | 45.92 (41.85, 50.27) | 8898 | 24.86 (24.35, 25.39) | 1.85* (1.68, 2.03) |

| 55–64 y | 129 | 19.38 (16.18, 23.03) | 3300 | 11.13 (10.76, 11.52) | 1.74* (1.45, 2.08) |

| 65–74 y | 34 | 9.72 (6.73, 13.58) | 678 | 3.69 (3.41, 3.98) | 2.63* (1.81, 3.72) |

| 75–84 y | 10 | 6.39 (3.06, 11.75) | 359 | 2.89 (2.60, 3.20) | 2.21* (1.05, 4.12) |

| ≥ 85 y | a | 6.63 (1.37, 19.37) | 219 | 4.38 (3.82, 5.00) | 1.51 (0.31, 4.48) |

| Fall | |||||

| Total | 566 | 11.90 (10.86, 12.99) | 24 621 | 8.36 (8.26, 8.47) | 1.42* (1.30, 1.56) |

| Male | 350 | 16.14 (14.25, 18.19) | 12 282 | 10.43 (10.24, 10.62) | 1.55* (1.36, 1.75) |

| Female | 216 | 8.59 (7.44, 9.85) | 12 339 | 6.76 (6.64, 6.88) | 1.27* (1.10, 1.46) |

| 0 y | a | 1.28 (0.16, 4.64) | 16 | 0.65 (0.37, 1.06) | 1.97 (0.22, 8.40) |

| 1–4 y | a | 0.70 (0.19, 1.79) | 22 | 0.22 (0.14, 0.34) | 3.16 (0.79, 9.30) |

| 5–14 y | a | 0.28 (0.08, 0.71) | 45 | 0.17 (0.12, 0.23) | 1.62 (0.42, 4.45) |

| 15–24 y | 19 | 1.28 (0.77, 2.00) | 200 | 0.67 (0.58, 0.77) | 1.91* (1.12, 3.06) |

| 25–34 y | 27 | 2.53 (1.67, 3.68) | 237 | 0.88 (0.78, 1.01) | 2.86* (1.84, 4.27) |

| 35–44 y | 58 | 5.53 (4.20, 7.15) | 418 | 1.35 (1.23, 1.49) | 4.08* (3.05, 5.39) |

| 45–54 y | 76 | 7.44 (5.86, 9.31) | 1142 | 3.19 (3.01, 3.38) | 2.33* (1.82, 2.94) |

| 55–64 y | 72 | 10.82 (8.46, 13.62) | 1654 | 5.58 (5.31, 5.85) | 1.94* (1.51, 2.46) |

| 65–74 y | 85 | 24.29 (19.40, 30.03) | 2571 | 13.98 (13.45, 14.53) | 1.74* (1.38, 2.16) |

| 75–84 y | 120 | 76.64 (63.55, 91.65) | 7203 | 57.92 (56.59, 59.27) | 1.32* (1.10, 1.58) |

| ≥ 85 y | 99 | 218.68 (177.73, 266.23) | 11 113 | 222.12 (218.01, 226.29) | 0.98 (0.80, 1.20) |

Note. AI/AN = American Indian/Alaska Native; CI = confidence interval; CHSDA = Contract Health Service Delivery Areas; IHS = Indian Health Service; RR = rate ratio. Analyses are limited to people of non-Hispanic origin. AI/AN race is reported from death certificates or through linkage with the IHS patient registration database. Total, male, and female rates are per 100 000 people and were age adjusted to the 2000 US standard population (11 age groups; Census P25-1130). Age-specific rates are crude rates. RRs were calculated in SEER*Stat before rounding of rates and may not equal RRs calculated from rates presented in table. IHS regions are defined as follows: AKb; Northern Plains (IL, IN,b IA,b MI,b MN,b MT,b NE,b ND,b SD,b WI,b WYb); Southern Plains (OK,b KS,b TXb); Southwest (AZ,b CO,b NV,b NM,b UTb); Pacific Coast (CA,b ID,b OR,b WA,b HI); East (AL,b AR, CT,b DE, FL,b GA, KY, LA,b ME,b MD, MA,b MS,b MO, NH, NJ, NY,b NC,b OH, PA,b RI,b SC,b TN, VT, VA, WV, DC). Percentage regional coverage of AI/AN persons in CHSDA counties to AI/AN persons in all counties: Northern Plains = 64.8%; Alaska = 100%; Southern Plains = 76.3%; Southwest = 91.3%; Pacific Coast = 71.3%; East = 18.2%; and total US = 64.2%.

Source. AI/AN Mortality Database (1990–2009).

Counts < 10 are suppressed; if no cases were reported, then rates and RRs could not be calculated. Suppressed counts are included in overall totals.

Identifies state with ≥ 1 county designated as CHSDA.

*P < .05.

Unintentional Poisonings

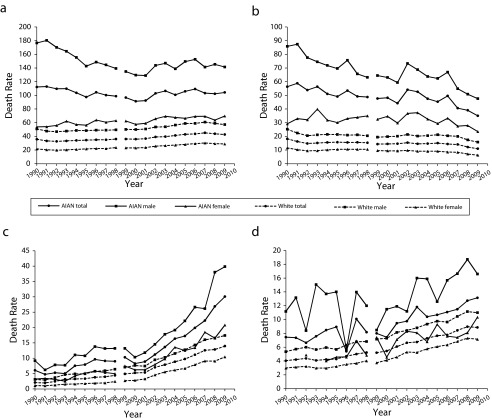

Death rates resulting from unintentional poisoning, which includes accidental overdose of drugs, rose dramatically in both AI/AN and White populations from 1990 to 2009 (Figure 1, Table C). From 2005 to 2009, poisoning death rates were approximately 2 times higher among AI/AN persons (23.3) than among Whites (12.1; Table 2). Poisoning death rates among AI/AN persons were higher than rates among Whites in all IHS regions except the East; the greatest disparity was in the Northern Plains (RR = 3.1). Alaska had the highest poisoning death rate (33.8) for the AI/AN population, followed by the Southern Plains (29.2) and the Pacific Coast (27.1).

FIGURE 1—

Unintentional injury death rates for AI/ANs and Whites by (a) unintentional injuries, (b) motor vehicle traffic injury, (c) unintentional poisoning, and (d) falls: Contract Health Service Delivery Area counties, United States, 1990–2009.

Note. AI/AN = American Indian/Alaska Native. Analyses are limited to people of non-Hispanic origin. AI/AN race is reported from death certificates or through linkage with the Indian Health Service patient registration database. Rates are per 100 000 people and were age adjusted to the 2000 US standard population (11 age groups; Census P25-1130).

Source. AI/AN Mortality Database (1990–2009); the following states and years of data are excluded because Hispanic origin was not collected on the death certificate: LA, 1990; NH, 1990–1992; OK, 1990–1996.

From 2000 to 2009, death rates resulting from unintentional poisoning increased significantly, 14.9% per year among the total AI/AN population and 15.6% per year among AI/AN males (Table C). The highest poisoning death rates among AI/AN persons were in the 35 to 44 and 45 to 54 age groups (Table 3). Poisoning death rates were significantly higher among AI/AN persons than among Whites for those aged 1 to 84 years. The greatest disparity was among children aged 1 to 4 years, in which the death rate for AI/AN persons was 10.4 times the rate for Whites; however, the AI/AN rate was based on small numbers and should be interpreted with caution. Among other age groups, significant RRs ranged from 2.9 in children aged 5 to 14 years (the AI/AN rate in these groups was also based on small numbers) to 1.6 in people aged 15 to 24 years.

Unintentional Falls

Unintentional fall death rates also increased significantly for AI/ANs and Whites from 1990 to 2009 (Figure 1, Table C). The disparity in fall death rates between AI/AN and White persons was smaller than that for other causes of injury from 2005 to 2009 (Table 2). The unintentional fall death rate among AI/AN people (11.9) was 1.4 times higher than that among Whites (8.4). Fall death rates among AI/AN people were highest in the Southwest (15.8) and Northern Plains (13.5), and the greatest disparities between AI/AN and White persons were in the Northern and Southern Plains (RR = 1.5; Table 2).

From 2005 to 2009, the fall death rate among AI/AN males was almost twice that among AI/AN females (Table 3). People aged 75 years and older in AI/AN and White populations had the highest fall death rates. Yet, disparities in fall deaths existed among people aged 75 to 84 years (RR = 1.3) and 65 to 74 years (RR = 1.7). The greatest disparities in fall deaths between the 2 populations was among adults aged 35 to 44 years (RR = 4.1), with RRs for the adjacent age groups (25–34 years and 45–54 years) only slightly lower.

DISCUSSION

Our results reveal that UIs remain a significant public health problem in AI/AN and White populations. Although data reveal similar trends for both populations, with decreases in MVT death rates and increases poisoning and fall death rates, AI/AN people continue to have significantly higher rates of UI death overall and by specific causes than Whites (Figure 1 and Table 2). Furthermore, the rate disparities between AI/AN and White persons in both CHDSA and all US counties combined demonstrate that the AI/AN population is disproportionately affected by injury compared with the White population (Table 1, Table B). The significant disparity in injury fatalities between AI/AN and White populations may be caused by inequalities in socioeconomic status, access to health services, and social and environmental conditions that persist in AI/AN communities and are underlying determinants of mortality.17,18

Motor Vehicle Traffic

Our findings are consistent with other studies that have shown that the US AI/AN population has the highest MVT death rate of any racial/ethnic group. MVT deaths were the leading cause of unintentional death among AI/AN persons in all IHS regions, except in Alaska, where roads are few and snow machines, boats, and airplanes are used for transportation in many AI/AN population areas.

Risk factors for MVT death in AI/AN communities include low restraint use and alcohol use. In 2002, the average seat belt use rate on reservations was 55.4%, compared with 75% in the United States overall. Additionally, seat belt use rates differed considerably by tribe, with reported rates ranging from 9% to 85%. Reservations with primary seat belt laws had the highest use rates, followed by reservations with secondary seat belt laws; reservations with no seat belt laws had the lowest use rates.19

The AI/AN population also had the highest percentage of unrestrained passenger vehicle occupants killed among all racial/ethnic groups.20 Child safety seat use rates for AI/AN communities varied greatly; however, rates were generally much lower than national rates.21 In 1 study of 3 Northwest tribes, child safety seat use rates ranged from 12% to 21% for children from birth to age 4 years, attributable to the absence of enforcement of restraint laws (i.e., not issuing citations for violators and not conducting occupant protection campaigns).22

Several studies have shown that the AI/AN population has a relatively high prevalence of alcohol-impaired driving and the highest alcohol-related MVT death rate among racial/ethnic populations.23,24 From 2005 to 2009, the alcohol-attributable MVT death RR was 2.4, highlighting the need to further implement proven environmental strategies that reduce alcohol consumption in AI/AN communities.25

Evidence-based interventions for reducing MVT occupant deaths that increase restraint use and decrease impaired driving have been shown to work in AI/AN communities.26,27 Several AI/AN programs have demonstrated that interventions can be successful when they combine multiple methods and use partnerships to change policy, the environment, and individual behavior. The IHS Ride Safe program had measurable increases in child safety seat use through parent education and child safety seat distribution.28 In another example, the Northern Ute Tribe experienced an increase in seat belt use from 22% to 42% and a 67% decrease in fatal crashes in 2 years.29 The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Tribal Motor Vehicle Injury Prevention Program funded AI/AN programs to tailor, implement, and evaluate evidence-based interventions to reduce motor vehicle–related injury and death in their communities. The programs were successful at increasing seat belt use, increasing child safety seat use, and decreasing alcohol-impaired driving.30 For instance, the San Carlos Apache Tribal Motor Vehicle Injury Prevention Program addressed driver alcohol use by increased sobriety checkpoints, a public information campaign, and efforts to implement a 0.08 blood alcohol concentration limit for drivers on the reservation.28 The San Carlos Apache Tribe saw a 33% decrease in arrests for driving under the influence, a 20% reduction in crashes with injuries and fatalities, and a 33% reduction in nighttime crashes from 2004 to 2006.28 Similarly, the Ho Chunk Nation achieved an increase in seat belt use from 50.5% to 62.7% and an increase in child safety seat use from 26.4% to 78.4% in 5 years.31

Unintentional Poisonings

In the United States for all races combined, poisoning deaths from drug overdose have been rising steadily over the past 2 decades, with nearly 9 of 10 poisoning deaths caused by drugs.32 From 2002 to 2008, non-Hispanic White and AI/AN persons had the highest drug overdose death rates compared with other racial/ethnic groups.33 In 2008, 20 044 overdose deaths were attributed to prescription drugs.34 For deaths involving opioid pain relievers, the rate among AI/AN persons (6.2) was 3 times higher than the rates for Blacks (1.9) and Hispanic Whites (2.1).34 National Survey on Drug Use and Health data for 2003 to 2011 showed that AI/AN persons were more likely to require and receive treatment of a substance use problem than were people from other racial/ethnic groups.35 The significant disparity in poisoning death rates between AI/AN persons and other populations might be caused by a variety of socioeconomic inequalities between the groups. Poverty, unemployment, education, and access to health care and differences in medication dispensing policies between the regions might have contributed to the varying death rates.36

Prevention efforts must weigh the benefits of reducing misuse and abuse with the legitimate need for pain medication. Prevention options include implementing a controlled substances prescription monitoring program, which protects legitimate access to treatment while reducing misuse and abuse; offering drug drop-off services; and increasing enforcement efforts against improper prescribing. One evidence-based approach, the Project Lazarus model,37 used a comprehensive, community-based approach to prevent prescription drug overdoses in various White communities. Components of the model include community activation, data monitoring, prevention through education, use of rescue medication, and program evaluation. This approach could be explored for its usefulness in addressing these problems in AI/AN communities.38

Unintentional Falls

Falls have been shown to be the leading cause of injury deaths and the most common cause of nonfatal injuries and hospital admissions for trauma among older adults 65 years and older in the United States.39 Falls are particularly serious for AI/AN adults of this age group, who experience more comorbidity and chronic illnesses (such as diabetes and heart disease) than does the general population, increasing their risk of dying from a fall.40 Falls among AI/AN persons were the leading cause of traumatic brain injury hospitalizations for people 45 years and older.41 Fall-related traumatic brain injury death rates were higher for AI/AN persons than for Whites among those aged 45 to 74 years.42

Studies of AI/AN older adult falls have focused on a variety of important risk factors, including medication-related risk factors. One article specifically explored potentially inappropriate medications and found that their use was high among AI/AN older adults, particularly for the 65 to 74 years age group.43 Polypharmacy, the concurrent use of multiple medications, has been associated with a higher risk of falls.44 In 2009, 73% of 113 330 AI/AN persons 50 years and older received at least 1 prescription at IHS health care facilities and Tribal and Urban Indian Health Centers. Forty-three percent received 4 or more prescriptions, 24% received 7 or more prescriptions, and 13% received 10 or more.44

Studies have found that multifactorial or multicomponent interventions to prevent falls by older people are effective in reducing falls.45 The American Geriatrics Society has recommended medication reduction for older adults taking 4 or more medications.45 In addition, it has recommended exercise that includes strength and balance, gait, and coordination training; environmental adaptation to reduce fall risk factors in the home and in daily activities; and interventions such as vision improvement and chronic disease management.

Limitations

Although linkage with the IHS patient database allows for improvement in AI/AN classification, the IHS database may not be complete for several reasons. Specifically, not all AI/AN individuals are members of federally recognized tribes, some AI/AN persons do not meet requirements for blood quantum, and not all AI/AN people may use IHS services. Federally recognized tribes vary substantially in the proportion of Native ancestry required for tribal membership and therefore for eligibility for IHS services. Whether and how this discrepancy in tribal membership requirements may influence some of our findings is unclear, although our findings are consistent with prior reports. Furthermore, limiting the analyses to the non-Hispanic AI/AN population excludes some individuals. Although the exclusion of such persons reduces the overall count of AI/AN deaths by less than 5%, it may disproportionately affect some states.

Finally, although describing UI death using AI/AN persons living in CHSDA counties improves the issue of racial misclassification, it excludes AI/AN populations in specific regions and urban areas, which have increasing numbers of AI/AN persons relocating from the reservations. The generalizability of the findings are also affected by the varying percentage of regional coverage of AI/AN persons in CHSDA counties to AI/AN persons in all counties, with a low of 18.2% in the East to a high of 100% in Alaska, in which all counties are CHSDA counties.

Conclusions

High rates of UI death, especially the alarming increase in unintentional poisoning deaths, suggest that injury prevention remains a major priority for improving the health of and preventing death among the AI/AN population. Addressing injuries continues to be a complex undertaking for the 566 federally recognized tribes, with varied cultures, infrastructures, and environments. Although there continue to be barriers, including poverty, alcohol use, and complexity of tribal structures and jurisdictions, various interventions with rigorously demonstrated effectiveness in non-AI/AN communities have been shown to work for AI/AN populations when tailored to meet the needs of these communities. Additional research, including analytic studies that adjust for these complex factors, is needed to target findings to regional prevention and policy initiatives. Reliable data and community engagement with programs tailored to specific, local settings and problems are essential to successful, sustainable injury prevention interventions.

Acknowledgments

We thank Melissa Jim and David Espey for their contributions and assistance with this study.

Human Participant Protection

Institutional review board approval was not needed because the research was not conducted on human participants.

References

- 1.National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. Injury prevention and control: Data and statistics (WISQARS) Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/ncipc/wisqars. Accessed April 30, 2013.

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Vital signs: unintentional injury deaths among persons aged 0-19 years—United States, 2000-2009. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2012;61(15):270–276. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hu G, Baker SP. Trends in unintentional injury deaths, US, 1999–2005: age, gender, and racial/ethnic differences. Am J Prev Med. 2009;37(3):188–194. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Fatal injuries among children by race and ethnicity—United States, 1999–2002. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2007;56(No. SS05):1–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.US Department of Health and Human Services, Indian Health Service. Indian Health Focus: Injuries. 2002–2003 ed. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rosenberg HM, Maurer JD, Sorlie PD et al. Quality of death rates by race and Hispanic origin: a summary of current research, 1999. Vital Health Stat 2. 1999;(128):1–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harwell TS, Hansen D, Moore KR, Jeanotte D, Gohdes D, Helgerson SD. Accuracy of race coding on American Indian death certificates, Montana, 1996–1998. Public Health Rep. 2002;117(1):44–49. doi: 10.1093/phr/117.1.44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Espey DK, Jim MA, Richards T, Begay C, Haverkamp D, Roberts D. Methods for improving the quality and completeness of mortality data for American Indians and Alaska Natives. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(6 suppl 3):S286–S294. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Edwards BK, Noone AM, Mariotto AB et al. Annual report to the nation on the status of cancer, 1975–2010, featuring prevalence of comorbidity and impact on survival among persons with lung, colorectal, breast, or prostate cancer. Cancer. 2013 doi: 10.1002/cncr.28509. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program. Rockville, MD: National Cancer Institute, DCCPS, Surveillance Research Program, Surveillance Systems Branch; 2013. SEER*Stat Database: Death—All COD, aggregated with state, total US (1969–2010) Available at: http://www.seer.cancer.gov. Accessed March 31, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 11.International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 12.International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miniño AM, Anderson RN, Fingerhut LA, Boudreault MA, Warner M. Deaths: injuries, 2002. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2006;54(10):1–124. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute; SEER*Stat [computer program]. Version 8.0.4. Available at: http://seer.cancer.gov/seerstat. Accessed April 24, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tiwari RC, Clegg LX, Zou Z. Efficient interval estimation for age-adjusted cancer rates. Stat Methods Med Res. 2006;15(6):547–569. doi: 10.1177/0962280206070621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Clegg LX, Hankey BF, Tiwari R, Feuer EJ, Edwards BK. Estimating average annual per cent change in trend analysis. Stat Med. 2009;28(29):3670–3682. doi: 10.1002/sim.3733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wallace LJD, Sleet DA, James SP. Injuries and the ten leading causes of death for Native Americans in the US: opportunities for prevention. IHS Primary Care Provider. 1997;22(9):140–145. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Piland NF, Berger LR. The economic burden of injuries involving American Indians and Alaska Natives: a critical need for prevention. IHS Primary Care Provider. 2007;32(9):269–280. [Google Scholar]

- 19.US Department of Transportation, National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. Safety Belt Use Estimate for Native American Tribal Reservations. Washington, DC: US Department of Transportation; 2005. DOT HS 809 921. [Google Scholar]

- 20.US Department of Transportation, National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. Fatal Motor Vehicle Crashes on Indian Reservations 1975–2002. Washington, DC: US Department of Transportation; 2004. DOT HS 809 727. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Letourneau RJ, Crump CE, Bowling JM, Kuklinski DM, Allen CW. Ride Safe: a child passenger safety program for American Indian and Alaska Native children. Matern Child Health J. 2008;12(1 suppl 1):55–63. doi: 10.1007/s10995-008-0332-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Smith ML, Berger LR. Assessing community child passenger safety efforts in three Northwest tribes. Inj Prev. 2002;8(4):289–292. doi: 10.1136/ip.8.4.289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Voas RB, Tippets AS, Fisher DA. Ethnicity and Alcohol Related Fatalities: 1990 to 1994. Landover, MD: Pacific Institute for Research and Evaluation; 2000. Report no. DOT HS 809 068. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Alcohol-attributable deaths and years of potential life lost among American Indians and Alaska Natives—United States, 2001–2005. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2008;57(34):938–941. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Landen M, Roeber J, Naimi T, Nielsen L, Sewell M. Alcohol-attributable mortality among American Indians and Alaska Natives in the United States, 1999–2009. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(6 suppl 3):S343–S349. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Evans CA, Jr, Fielding JE, Brownson RC et al. Motor-vehicle occupant injury: strategies for increasing use of child safety seats, increasing use of safety belts, and reducing alcohol-impaired driving. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2001;50(RR-7):1–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pollack KM, Frattaroli S, Young JL, Dana-Sacco G, Gielen AC. Motor vehicle deaths among American Indian and Alaska Native populations. Epidemiol Rev. 2012;34(1):73–88. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxr019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reede C, Piontkowski S, Tsatoke G. Using evidence-based strategies to reduce motor vehicle injuries on the San Carlos Apache Reservation. IHS Primary Care Provider. 2007;32(7):209–212. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Billie H, LaFramboise J, Tabbee B. Ute Indian Tribe enforcement-based injury prevention. IHS Primary Care Provider. 2007;32(9):281–283. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Injuries among American Indians/Alaska Natives (AI/AN): CDC activities. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/Motorvehiclesafety/native/research.html. Accessed April 30, 2013.

- 31.Letourneau RJ, Crump CE, Thunder N et al. Increasing occupant restraint use among Ho-Chunk Nation members; tailoring evidence-based strategies to local context. IHS Primary Care Provider. 2009;34(7):212–218. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Paulozzi LJ. Prescription drug overdoses: a review. J Safety Res. 2012;43(4):283–289. doi: 10.1016/j.jsr.2012.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Warner M, Chen LH, Makuc DM, Anderson RN, Miniño AM. Drug Poisoning Deaths in the United States, 1980–2008. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics; 2011. NCHS Data Brief No. 81. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Vital signs: overdoses of prescription opioid pain relievers—United States, 1999–2008. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60(43):1487–1492. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. The NSDUH Report: Need for and Receipt of Substance Use Treatment Among American Indians or Alaska Natives. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2012. Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Castor ML, Smyser MS, Taualii MM, Park AN, Lawson SA, Forquera RA. A nationwide population-based study identifying health disparities between American Indians/Alaska Natives and the general populations living in select urban counties. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(8):1478–1484. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.053942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Project Lazarus. Available at: http://projectlazarus.org/about-lazarus/project-lazarus-model. Accessed May 15, 2013.

- 38.Muazzam S, Swahn MH, Alamgir H, Nasrullah M. Differences in poisoning mortality in the United States, 2003–2007: epidemiology of poisoning deaths classified as unintentional, suicide or homicide. West J Emerg Med. 2012;13(3):230–238. doi: 10.5811/westjem.2012.3.11762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hornbrook MC, Stevens VJ, Wingfield DJ, Hollis JF, Greenlick MR, Ory MG. Preventing falls among community-dwelling older persons: results from a randomized trial. Gerontologist. 1994;34(1):16–23. doi: 10.1093/geront/34.1.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dixon M, Roubideaux Y. Promises to Keep: Public Health Policy for American Indians and Alaska Natives in the 21st Century. 1st ed. Washington, DC: American Public Health Association; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Adekoya N, Wallace LJD. Traumatic brain injury among American Indians/Alaska Natives—United States, 1992–1996. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2002;51(14):303–305. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Coronado VG, Xu L, Basavaraju SV et al. Surveillance for traumatic brain injury–related deaths—United States, 1997–2007. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2011;60(5):1–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Garret Sims J, Berger L, Krestel C, Finke B, Correa O. Potentially inappropriate medications (PIMs) and falls risk in older American Indians and Alaska Native adults: a pilot study. IHS Primary Care Provider. 2011;36(7):147–153. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ballentine NH. Polypharmacy in the elderly: maximizing benefit, minimizing harm. Crit Care Nurs Q. 2008;31(1):40–45. doi: 10.1097/01.CNQ.0000306395.86905.8b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Panel on Prevention of Falls in Older Persons. American Geriatrics Society and British Geriatrics Society. Summary of the updated American Geriatrics Society/British Geriatrics Society clinical practice guideline for prevention of falls in older persons. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59(1):148–157. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.03234.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]