Abstract

Objectives. We present regional patterns and trends in all-cause mortality and leading causes of death in American Indians and Alaska Natives (AI/ANs).

Methods. US National Death Index records were linked with Indian Health Service (IHS) registration records to identify AI/AN deaths misclassified as non-AI/AN. We analyzed temporal trends for 1990 to 2009 and comparisons between non-Hispanic AI/AN and non-Hispanic White persons by geographic region for 1999 to 2009. Results focus on IHS Contract Health Service Delivery Area counties in which less race misclassification occurs.

Results. From 1990 to 2009 AI/AN persons did not experience the significant decreases in all-cause mortality seen for Whites. For 1999 to 2009 the all-cause death rate in CHSDA counties for AI/AN persons was 46% more than that for Whites. Death rates for AI/AN persons varied as much as 50% among regions. Except for heart disease and cancer, subsequent ranking of specific causes of death differed considerably between AI/AN and White persons.

Conclusions. AI/AN populations continue to experience much higher death rates than Whites. Patterns of mortality are strongly influenced by the high incidence of diabetes, smoking prevalence, problem drinking, and social determinants. Much of the observed excess mortality can be addressed through known public health interventions.

American Indians and Alaska Natives (AI/ANs) in the United States have long endured a legacy of injustice and discrimination with multiple negative manifestations, including alarming health disparities and inadequate health care. In the early decades of the Indian Health Service (IHS), improvements in the health of AI/AN populations were significant, principally as a result of sanitary water supplies, control of tuberculosis and other infectious diseases, and improved nutrition.1 Starvation is no longer an issue in AI/AN communities; rather, the opposite is true: obesity—a different form of malnutrition—and its attendant chronic diseases. With infant and childhood mortality greatly reduced, more AI/AN people are developing cancer, diabetes, heart disease, and stroke.

In the efforts to better characterize and track the health status of AI/AN populations—a critical step to address health disparities—we see a recurrent theme of inadequate and inaccurate data, most often related to race misclassification that occurs in many health-related databases. Accurate health surveillance data are essential to address health disparities and to plan, implement, and evaluate disease prevention and control activities. Previous reports have indicated less favorable health status of AI/AN people compared with the general population of US Whites.2,3 Among health status indicators, mortality data provide essential information for measuring the health of a population. Patterns of mortality in specific demographic subpopulations, including race and ethnic groups, may reflect differences in socioeconomic status and access to medical care or the prevalence of subpopulation-specific risk factors.4 However, the goal of producing reliable mortality estimates for AI/AN populations has been hampered by the misclassification of race that frequently occurs in vital statistics data.5

We sought to provide an overview of leading causes of death and trends in all-cause mortality for the AI/AN population—particularly those residing in areas served by the IHS—using national mortality data that have been linked to the IHS patient registration data to improve race classification.

METHODS

Detailed methods for generating the analytic mortality files are described elsewhere in this supplement.6 An abbreviated description follows.

Data Sources

Population estimates.

We used county-level population estimates produced by the US Census Bureau as denominators in the rate calculations. To manage multiple-race data collected since 2000, the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS), in collaboration with the US Census Bureau, developed a technique of bridging race categories into single-race annual population estimates.7 The National Cancer Institute makes further refinements regarding race and county geographic codes, makes adjustments for population shifts as a result of Hurricanes Katrina and Rita in 2005, and provides public access to these estimates on the Institute’s Web site.8,9 During preliminary analyses, we discovered that population estimates significantly overestimated AI/AN persons of Hispanic origin.10 Therefore, to avoid underestimating mortality in AI/AN populations, we limited analyses to non-Hispanic AI/AN persons. We chose non-Hispanic Whites as the most homogeneous referent group. For conciseness, the term “non-Hispanic” is omitted henceforth when discussing both groups.

Death records.

Each state compiles death certificate data and sends them to the NCHS, where they are edited for consistency. The NCHS makes this information available to the research community as part of the National Vital Statistics System and includes underlying and multiple cause-of-death fields, state of residence, age, sex, race, and ethnicity.11 NCHS and the Census Bureau use the same bridging algorithm to assign a single race to decedents with multiple races reported on the death certificate.12

The IHS patient registration database was linked to the National Death Index to identify AI/AN decedents who had received health care in IHS or tribal facilities and were misclassified as non-Native.6 After this linkage, IHS AI/AN records identified as those of deceased individuals were linked to the 1990 to 2009 annual National Vital Statistics System mortality files as an additional indicator of AI/AN ancestry. These files were combined with corresponding annual bridged race intercensal population estimates to create an analytic file in SEER*Stat version 8.0.413 (called the AI/AN Mortality Database, or AMD). Race for AI/AN deaths in this article is assigned as reported elsewhere in this supplement.6 In short, the AMD combines race classification by NCHS on the basis of the death certificate and information derived from data linkages between the IHS patient registration database and the National Death Index. For 1990 to 1998, we coded the underlying cause of death according to the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9).14 For 1999 to 2009, we used the International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision (ICD-10).15 Trend analyses spanning ICD-9 and ICD-10 reporting years took into account comparability of cause of death recodes between the 2 revisions.16 To present the leading cause of death in rank order—as established by death counts—we used the method developed by NCHS based on the recode for 113 selected causes of death.16,17

Geographic Coverage and Time Periods

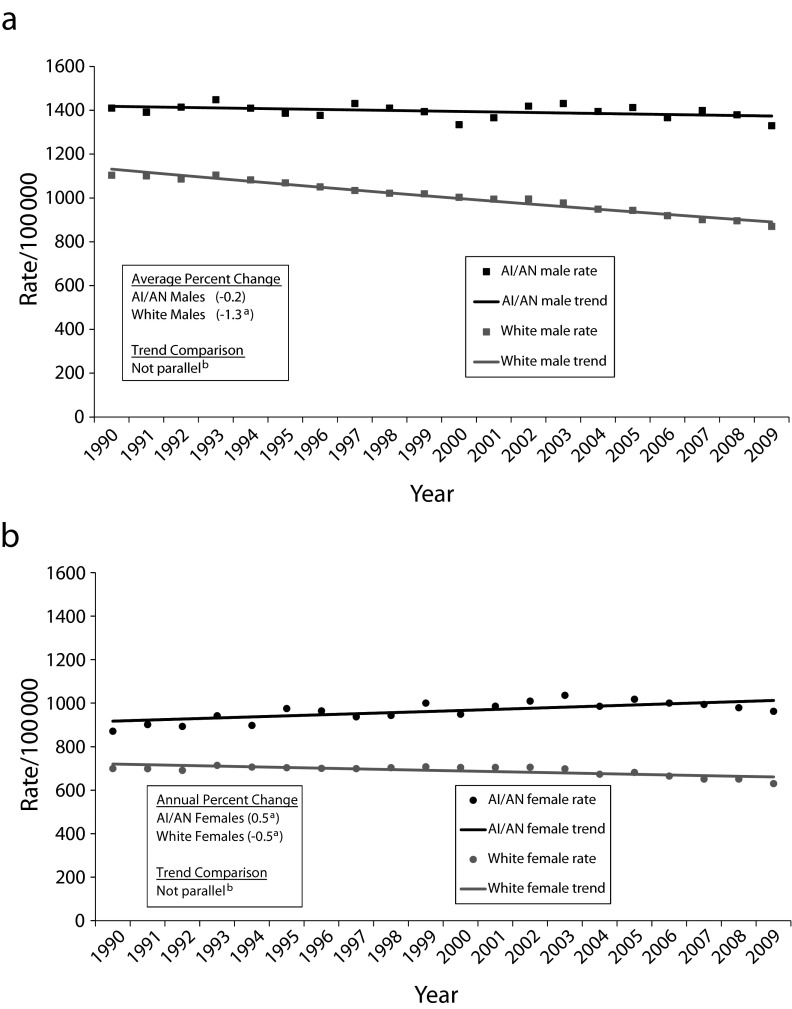

Most analyses in this article are restricted to IHS Contract Health Service Delivery Area (CHSDA) counties, which, in general, contain federally recognized tribal reservations or off-reservation trusts or are adjacent to them.18 Linkage studies have indicated less misclassification of race for AI/AN persons in these counties.5,18 The CHSDA counties also have higher proportions of AI/AN persons in relation to the total population than do non-CHSDA counties, with 64% of the US non-Hispanic AI/AN population residing in the 637 counties designated as CHSDA (these counties represent 20% of the 3141 counties in the United States). Although less geographically representative, analyses restricted to CHSDA counties are presented for death rates in this article for the purpose of offering improved accuracy in interpreting mortality statistics for AI/AN populations. Trend analyses shown in Figure 1 span 1990 to 2009, whereas rates and rate ratios (RRs) presented in the tables are limited to 1999 to 2009 to reflect a more recent time period and consistent cause of death coding in ICD-10.

FIGURE 1—

Annual age-adjusted all-cause death rates and Joinpoint trend lines for AI/AN and White (a) males and (b) females: Contract Health Service Delivery Area counties, United States, 1990–2009.

Note. AI/AN = American Indian/Alaska Natives. Analyses are limited to persons of non-Hispanic origin. AI/AN race is reported from death certificates or through linkage with the IHS patient registration database.

aThe annual percentage change in rates during 1990–2009 was significant at α = .05.

bThe difference in average annual percentage change between AI/AN and Whites during the past 10 years (2000–2009) was significant at α = .05.

The analyses were completed for all regions combined and by individual IHS region: Northern Plains, Alaska, Southern Plains, Southwest, Pacific Coast, and East.18 Identical or similar regional analyses have been used for other health-related publications focusing on AI/AN populations.19–21

Statistical Methods

All rates, expressed per 100 000 population, were directly age adjusted using SEER*Stat software version 8.0.4 to the 2000 US standard population (Census P25-1130) and using 11 age groups (< 1, 1–4, 5–14, 15–24, 25–34, 35–44, 45–54, 55–64, 65–74, 75–84, and ≥ 85 years) in accordance with a 1998 US Department of Health and Human Services recommendation.22 Readers should avoid comparison of these data with published death rates adjusted using a different standard population.

Using the age-adjusted death rates, we calculated standardized RRs for AI/AN populations using White rates for comparison. We calculated RRs using SEER*Stat and confidence intervals (CIs) for age-adjusted rates and RR on the basis of methods described by Tiwari et al.23 using SEER*Stat version 8.0.4.

We assessed temporal changes in annual age-adjusted death rates, including the annual percentage change for each interval, with joinpoint regression techniques using statistical software developed by the National Cancer Institute (Rockville, MD).24 Statistical significance was set at P < .05. Trend analyses spanned the entire period covered by AMD 1990 to 2009. We also conducted pairwise comparisons to determine the parallelism of trends. Once 2 groups were determined to have parallel or nonparallel trends, we tested the average annual percentage change for the 2 groups, using the past 10 years, to determine whether they were statistically different.

RESULTS

All-cause death rates by geographic region and sex comparing AI/AN with White persons in CHSDA counties only and all counties combined are presented in Table 1. In general, death rates for AI/AN persons were greater in CHSDA counties than in all counties combined, whereas for Whites, death rates changed very little in relation to CHSDA groupings. In subsequent results as well as in the discussion, “death rates” refers to analyses restricted to CHSDA counties only. For all regions combined, AI/AN death rates for both sexes combined were nearly 50% greater than rates in Whites. The highest rates were noted in the Northern Plains and the Southern Plains, whereas the lowest were in the East and the Southwest. Comparisons of all-cause death rates in AI/AN populations with those in Whites ranged from near parity in the East region (RR = 1.04; 95% CI = 1.01, 1.07) to nearly 2 times higher in the Northern Plains region (RR = 1.90; 95% CI = 1.87, 1.93). For AI/AN and White populations, all-cause death rates were substantially lower for women than for men in all regions combined and in individual regions.

TABLE 1—

Death Rates for All Causes, by IHS Region and Sex for American Indians/Alaska Natives Compared With Whites, All Ages: United States, 1999–2009

| CHSDA Counties |

All Counties |

|||||||||

| IHS Region and Sex | AI/AN Count | AI/AN Rate | White Count | White Rate | AI/AN:White RR (95% CI) | AI/AN Count | AI/AN Rate | White Count | White Rate | AI/AN:White RR (95% CI) |

| Northern Plains | ||||||||||

| Total | 23 331 | 1461.8 | 786 392 | 770.6 | 1.90* (1.87, 1.93) | 31 188 | 1242.9 | 3 843 218 | 787.1 | 1.58* (1.56, 1.60) |

| Male | 12 709 | 1748.8 | 386 164 | 927.4 | 1.89* (1.84, 1.93) | 16 812 | 1484.9 | 1 846 384 | 947.8 | 1.57* (1.54, 1.60) |

| Female | 10 622 | 1243.4 | 400 228 | 649.2 | 1.92* (1.88, 1.96) | 14 376 | 1064.5 | 1 996 834 | 666.6 | 1.60* (1.57, 1.63) |

| Alaska | ||||||||||

| Total | 8616 | 1218.6 | 23 621 | 738.2 | 1.65* (1.61, 1.70) | 8616 | 1218.6 | 23 621 | 738.2 | 1.65* (1.61, 1.70) |

| Male | 4771 | 1431.6 | 13 600 | 856.8 | 1.67* (1.61, 1.74) | 4771 | 1431.6 | 13 600 | 856.8 | 1.67* (1.61, 1.74) |

| Female | 3845 | 1041.2 | 10 021 | 627.3 | 1.66* (1.60, 1.73) | 3845 | 1041.2 | 10 021 | 627.3 | 1.66* (1.60, 1.73) |

| Southern Plains | ||||||||||

| Total | 30 421 | 1313.1 | 358 711 | 928.7 | 1.41* (1.40, 1.43) | 35 130 | 1159.6 | 1 758 152 | 859.7 | 1.35* (1.33, 1.36) |

| Male | 15 946 | 1568.7 | 175 778 | 1102.2 | 1.42* (1.40, 1.45) | 18 391 | 1359.5 | 858 447 | 1018.7 | 1.33* (1.31, 1.36) |

| Female | 14 475 | 1116.3 | 182 933 | 790.9 | 1.41* (1.39, 1.44) | 16 739 | 1001.1 | 899 705 | 733.6 | 1.36* (1.34, 1.39) |

| Southwest | ||||||||||

| Total | 33 325 | 1017.8 | 669 622 | 789.7 | 1.29* (1.27, 1.30) | 35 366 | 1000.0 | 1 052 569 | 776.8 | 1.29* (1.27, 1.30) |

| Male | 18 836 | 1251.4 | 347 628 | 926.2 | 1.35* (1.33, 1.37) | 19 916 | 1218.4 | 536 547 | 909.7 | 1.34* (1.32, 1.36) |

| Female | 14 489 | 828.1 | 321 994 | 670.4 | 1.24* (1.21, 1.26) | 15 450 | 821.5 | 516 022 | 664.2 | 1.24* (1.22, 1.26) |

| Pacific Coast | ||||||||||

| Total | 20 779 | 1091.5 | 1 459 406 | 796.0 | 1.37* (1.35, 1.39) | 27 339 | 953.5 | 2 711 044 | 781.0 | 1.22* (1.21, 1.24) |

| Male | 10 875 | 1238.3 | 721 856 | 933.7 | 1.33* (1.30, 1.36) | 14 379 | 1088.3 | 1 327 483 | 916.5 | 1.19* (1.16, 1.21) |

| Female | 9904 | 971.1 | 737 550 | 683.8 | 1.42* (1.39, 1.45) | 12 960 | 842.9 | 1 383 561 | 671.4 | 1.26* (1.23, 1.28) |

| East | ||||||||||

| Total | 6172 | 828.7 | 1 559 313 | 795.7 | 1.04* (1.01, 1.07) | 24 738 | 595.7 | 12 136 547 | 824.8 | 0.72* (0.71, 0.73) |

| Male | 3231 | 939.1 | 750 611 | 957.7 | 0.98 (0.94, 1.02) | 13 095 | 691.7 | 5 872 696 | 988.2 | 0.70* (0.69, 0.71) |

| Female | 2941 | 735.4 | 808 702 | 671.0 | 1.10* (1.06, 1.14) | 11 643 | 518.3 | 6 263 851 | 698.3 | 0.74* (0.73, 0.76) |

| All regions | ||||||||||

| Total | 122 644 | 1165.9 | 4 857 065 | 798.8 | 1.46* (1.45, 1.47) | 162 377 | 964.4 | 21 525 151 | 812.2 | 1.19* (1.18, 1.19) |

| Male | 66 368 | 1381.8 | 2 395 637 | 948.8 | 1.46* (1.44, 1.47) | 87 364 | 1135.2 | 10 455 157 | 969.1 | 1.17* (1.16, 1.18) |

| Female | 56 276 | 991.5 | 2 461 428 | 678.6 | 1.46* (1.45, 1.47) | 75 013 | 827.3 | 11 069 994 | 689.9 | 1.20* (1.19, 1.21) |

Note. AI/AN = American Indians/Alaska Natives; CHSDA = Contract Health Service Delivery Areas; CI = confidence interval IHS = Indian Health Service; RR = rate ratio. All analyses were limited to decedents of non-Hispanic origin. AI/AN race is reported from death certificates or through linkage with the IHS patient registration database. Rates are per 100 000 people and were age adjusted to the 2000 US standard population (11 age groups; Census P25-1130). RRs were calculated in SEER*Stat (version 8.0.4) before rounding of rates and may not equal RRs calculated from rates presented in table. States and years data excluded because Hispanic origin was not collected on the death certificate: LA: 1990; NH: 1990–1992; OK: 1990–1996. IHS regions are defined as follows: Alaskaa; Northern Plains (IL, IN,a IA,a MI,a MN,a MT,a NE,a ND,a SD,a WI,a WYa); Southern Plains (OK,a KS,a TXa); Southwest (AZ,a CO,a NV,a NM,a UTa); Pacific Coast (CA,a ID,a OR,a WA,a HI); East (AL,a AR, CT,a DE, FL,a GA, KY, LA,a ME,a MD, MA,a MS,a MO, NH, NJ, NY,a NC,a OH, PA,a RI,a SC,a TN, VT, VA, WV, DC). Percentage regional coverage of AI/AN persons in CHSDA counties to AI/AN persons in all counties: Northern Plains = 64.8%; Alaska = 100%; Southern Plains = 76.3%; Southwest = 91.3%; Pacific Coast = 71.3%; East = 18.2%; total US = 64.2%.

Source. AI/AN Mortality Supplement Database (1990–2009).

Identifies states with ≥ 1 county designated as CHSDA.

*P < .05.

When examined by age, disparities in all-cause mortality were most evident in younger age groups, particularly ages 25 to 44 years (Table 2). This pattern was apparent across all IHS regions, and it was particularly prominent in the Northern Plains and Alaska, where all-cause death rates for AI/AN persons in this age group were more than 3 times higher than that for Whites.

TABLE 2—

Death Rates for All Causes, by IHS Region and Age for American Indians/Alaska Natives Compared With Whites, Males and Females: CHSDA Counties, United States, 1999–2009

| AI/AN |

White |

||||

| IHS Region and Age | Count | Rate | Count | Rate | AI/AN:White RR (95% CI) |

| Northern Plains | |||||

| 0–24 y | 2592 | 170.8 | 16 996 | 61.0 | 2.80 (2.69, 2.92) |

| 25–44 y | 3459 | 458.4 | 28 235 | 125.8 | 3.64 (3.51, 3.77) |

| 45–64 y | 7115 | 1385.3 | 119 707 | 520.2 | 2.66 (2.60, 2.73) |

| 65–84 y | 8064 | 6032.6 | 356 653 | 3274.3 | 1.84 (1.80, 1.88) |

| ≥ 85 y | 2101 | 18 584.7 | 264 801 | 15 021.1 | 1.24 (1.18, 1.29) |

| Alaska | |||||

| 0–24 y | 1116 | 192.8 | 1091 | 63.1 | 3.06 (2.81, 3.33) |

| 25–44 y | 1382 | 442.0 | 2160 | 144.3 | 3.06 (2.86, 3.28) |

| 45–64 y | 2253 | 1025.0 | 6822 | 489.4 | 2.09 (2.00, 2.20) |

| 65–84 y | 2937 | 4751.4 | 9789 | 3296.8 | 1.44 (1.38, 1.50) |

| ≥ 85 y | 928 | 17 040.0 | 3759 | 12 810.1 | 1.33 (1.24, 1.43) |

| Southern Plains | |||||

| 0–24 y | 1880 | 112.1 | 8062 | 78.0 | 1.44 (1.37, 1.51) |

| 25–44 y | 3322 | 357.4 | 15 420 | 186.4 | 1.92 (1.85, 1.99) |

| 45–64 y | 8461 | 1179.4 | 64 425 | 736.4 | 1.60 (1.57, 1.64) |

| 65–84 y | 12 050 | 5310.1 | 168 348 | 3869.4 | 1.37 (1.35, 1.40) |

| ≥ 85 y | 4708 | 20 388.0 | 102 456 | 16 309.3 | 1.25 (1.21, 1.29) |

| Southwest | |||||

| 0–24 y | 3425 | 136.0 | 14 190 | 64.5 | 2.11 (2.03, 2.19) |

| 25–44 y | 6221 | 440.1 | 30 684 | 165.3 | 2.66 (2.59, 2.74) |

| 45–64 y | 8920 | 956.8 | 122 589 | 615.3 | 1.56 (1.52, 1.59) |

| 65–84 y | 10 368 | 3697.1 | 320 538 | 3200.0 | 1.16 (1.13, 1.18) |

| ≥ 85 y | 4391 | 13 938.8 | 181 621 | 14 583.9 | 0.96 (0.93, 0.98) |

| Pacific Coast | |||||

| 0–24 y | 1434 | 114.6 | 25 902 | 56.7 | 2.02 (1.92, 2.13) |

| 25–44 y | 2754 | 330.2 | 56 985 | 140.5 | 2.35 (2.26, 2.44) |

| 45–64 y | 6430 | 942.9 | 248 186 | 578.7 | 1.63 (1.59, 1.67) |

| 65–84 y | 7787 | 4571.3 | 665 484 | 3383.5 | 1.35 (1.32, 1.38) |

| ≥ 85 y | 2374 | 15 236.5 | 462 849 | 14 854.0 | 1.03 (0.98, 1.07) |

| East | |||||

| 0–24 y | 431 | 89.9 | 26 451 | 59.2 | 1.52 (1.38, 1.67) |

| 25–44 y | 756 | 238.6 | 59 545 | 145.2 | 1.64 (1.53, 1.77) |

| 45–64 y | 1938 | 769.3 | 245 921 | 582.6 | 1.32 (1.26, 1.38) |

| 65–84 y | 2350 | 3526.3 | 720 164 | 3360.8 | 1.05 (1.01, 1.09) |

| ≥ 85 y | 697 | 10 573.4 | 507 232 | 14 793.5 | 0.71 (0.66, 0.77) |

| Total | |||||

| 0–24 y | 10 878 | 135.5 | 92 692 | 60.8 | 2.23 (2.18, 2.27) |

| 25–44 y | 17 894 | 392.2 | 193 029 | 145.9 | 2.69 (2.65, 2.73) |

| 45–64 y | 35 117 | 1059.0 | 807 650 | 584.3 | 1.81 (1.79, 1.83) |

| 65–84 y | 43 556 | 4634.3 | 2 240 976 | 3362.0 | 1.38 (1.37, 1.39) |

| ≥ 85 y | 15 199 | 16 252.5 | 1 522 718 | 14 913.2 | 1.09 (1.07, 1.11) |

Note. AI/AN = American Indian/Alaska Native; CHSDA = Contract Health Service Delivery Areas; CI = confidence interval; IHS = Indian Health Service; RR = rate ratio. Analyses were limited to people of non-Hispanic origin. AI/AN race is reported from death certificates or through linkage with the IHS patient registration database. Rates are per 100 000 people and were age adjusted to the 2000 US standard population (11 age groups; Census P25-1130). RR were calculated in SEER*Stat (version 8.0.4) before rounding of rates and may not equal rate ratios calculated from rates presented in table. IHS regions are defined as follows: Alaskaa; Northern Plains (IL, IN,a IA,a MI,a MN,a MT,a NE,a ND,a SD,a WI,a WYa); Southern Plains (OK,a KS,a TXa); Southwest (AZ,a CO,a NV,a NM,a UTa); Pacific Coast (CA,a ID,a OR,a WA,a HI); East (AL,a AR, CT,a DE, FL,a GA, KY, LA,a ME,a MD, MA,a MS,a MO, NH, NJ, NY,a NC,a OH, PA,a RI,a SC,a TN, VT, VA, WV, DC). Percent regional coverage of AI/AN persons in CHSDA counties to AI/AN persons in all counties: Northern Plains = 64.8%; Alaska = 100%; Southern Plains = 76.3%; Southwest = 91.3%; Pacific Coast = 71.3%; East = 18.2%; total US = 64.2%.

Source. AI/AN Mortality Database (1990–2009).

Identifies states with ≥ 1 county designated as CHSDA.

*P < .05.

Table 3 ranks the leading causes of death for AI/AN persons by sex and IHS region and all regions combined in CHSDA counties for 1999 to 2009 and compares the death rates with those for Whites residing in the same areas. Key patterns for all regions combined are presented briefly; see Table 3 for region-specific cause-of-death rankings.

TABLE 3—

Death Rates, Ranks, and Rate Ratios of the Top 15 Leading Causes of Death for American Indians/Alaska Natives Compared with Whites by Indian Health Service Region: United States, 1999–2009

| Northern Plains |

Alaska |

Southern Plains |

Southwest |

Pacific Coast |

East |

All United States |

|||||||||||||||

| Cause of Deatha | Rank,a AI/AN (White) | Rate,b AI/AN (White) | AI/AN: White RRc | Rank,a AI/AN (White) | Rate,b AI/AN (White) | AI/AN: White RRc | Rank,a AI/AN (White) | Rate,b AI/AN (White) | AI/AN: White RRc | Rank,a AI/AN (White) | Rate,b AI/AN (White) | AI/AN: White RRc | Rank,a AI/AN (White) | Rate,b AI/AN (White) | AI/AN: White RRc | Rank,a AI/AN (White) | Rate,b AI/AN (White) | AI/AN: White RRc | Rank,a AI/AN (White) | Rate,b AI/AN (White) | AI/AN: White RRc |

| Males | |||||||||||||||||||||

| All causes | 1748.8 (927.4) | 1.89* | 1431.6 (856.8) | 1.67* | 1568.7 (1102.2) | 1.42* | 1251.4 (926.2) | 1.35* | 1238.3 (933.7) | 1.33* | 939.1 (957.7) | 0.98 | 1381.8 (948.8) | 1.46* | |||||||

| Heart disease | 1 (1) | 403.0 (254.4) | 1.58* | 3 (2) | 269.3 (208.9) | 1.29* | 1 (1) | 440.2 (332.2) | 1.33* | 2 (1) | 232.2 (247.3) | 0.94* | 1 (1) | 309.2 (251.8) | 1.23* | 1 (1) | 243.5 (271.2) | 0.90* | 1 (1) | 320.9 (262.5) | 1.22* |

| Cancer | 2 (2) | 338.1 (223.4) | 1.51* | 1 (1) | 298.7 (207.2) | 1.44* | 2 (2) | 319.8 (244.2) | 1.31* | 3 (2) | 163.8 (207.1) | 0.79* | 2 (2) | 233.8 (223.7) | 1.05 | 2 (2) | 192.5 (231.7) | 0.83* | 2 (2) | 248.4 (224.7) | 1.11* |

| Accidents | 3 (4) | 163.9 (52.8) | 3.10* | 2 (3) | 166.5 (66.1) | 2.52* | 3 (4) | 118.5 (68.6) | 1.73* | 1 (4) | 175.8 (62.2) | 2.83* | 3 (4) | 107.4 (53.0) | 2.03* | 3 (4) | 74.5 (53.7) | 1.39* | 3 (4) | 141.3 (55.6) | 2.54* |

| Diabetes mellitus | 4 (6) | 107.9 (25.8) | 4.18* | 9 (7) | 27.2 (25.5) | 1.07 | 4 (6) | 83.6 (27.7) | 3.01* | 5 (8) | 78.3 (20.0) | 3.91* | 6 (6) | 60.8 (25.1) | 2.43* | 4 (6) | 58.8 (22.0) | 2.67* | 4 (6) | 75.5 (23.6) | 3.19* |

| Chronic liver disease | 5 (11) | 67.5 (10.2) | 6.64* | 10 (8) | 14.4 (11.2) | 1.28 | 7 (11) | 39.0 (13.6) | 2.87* | 4 (10) | 65.1 (13.8) | 4.74* | 4 (10) | 46.2 (13.9) | 3.33* | 6 (11) | 30.9 (13.0) | 2.38* | 5 (10) | 50.0 (12.9) | 3.88* |

| Suicide | 6 (7) | 41.6 (21.0) | 1.98* | 4 (4) | 65.4 (27.9) | 2.34* | 8 (8) | 31.5 (25.3) | 1.25* | 6 (6) | 33.9 (31.5) | 1.08* | 8 (8) | 29.0 (24.3) | 1.19* | 9 (8) | 13.0 (18.9) | 0.69* | 6 (7) | 34.7 (23.2) | 1.49* |

| CLRD | 7 (3) | 96.8 (56.7) | 1.71* | 5 (5) | 77.2 (49.9) | 1.55* | 5 (3) | 82.7 (73.2) | 1.13* | 12 (3) | 25.4 (58.1) | 0.44* | 5 (3) | 74.5 (57.7) | 1.29* | 7 (3) | 35.2 (50.8) | 0.69* | 7 (3) | 61.4 (56.4) | 1.09* |

| Stroke | 8 (5) | 66.6 (51.3) | 1.30* | 6 (6) | 77.0 (49.0) | 1.57* | 6 (5) | 70.5 (56.3) | 1.25* | 9 (5) | 43.8 (41.5) | 1.06 | 7 (5) | 61.7 (54.1) | 1.14* | 5 (5) | 52.5 (46.7) | 1.13 | 8 (5) | 59.3 (49.6) | 1.20* |

| Assault (homicide) | 9 (21) | 20.1 (2.0) | 9.79* | 7 (10) | 17.7 (5.2) | 3.44* | 11 (18) | 14.2 (5.6) | 2.53* | 7 (18) | 25.6 (5.7) | 4.51* | 9 (21) | 13.5 (3.6) | 3.72* | 12 (19) | 10.5 (3.7) | 2.81* | 9 (19) | 18.5 (3.8) | 4.85* |

| Influenza and pneumonia | 10 (8) | 49.1 (22.4) | 2.19* | 8 (11) | 44.2 (14.2) | 3.10* | 9 (7) | 39.0 (27.6) | 1.42* | 8 (7) | 56.6 (23.4) | 2.41* | 10 (9) | 25.4 (20.2) | 1.26* | 10 (7) | 25.4 (23.2) | 1.09 | 10 (8) | 42.7 (22.4) | 1.90* |

| Kidney disease | 11 (10) | 31.0 (15.4) | 2.01* | 11 (12) | 21.1 (9.6) | 2.19* | 10 (10) | 32.0 (16.6) | 1.93* | 10 (11) | 28.0 (14.0) | 2.01* | 12 (12) | 14.5 (8.7) | 1.66* | 8 (9) | 22.9 (18.0) | 1.27 | 11 (11) | 25.9 (14.0) | 1.85* |

| Septicemia | 12 (14) | 24.1 (7.2) | 3.34* | 12 (16) | 14.9 (5.9) | 2.53* | 12 (12) | 20.4 (11.5) | 1.77* | 11 (12) | 23.4 (10.3) | 2.27* | 15 (17) | 9.1 (5.1) | 1.78* | 11 (12) | 15.8 (13.6) | 1.17 | 12 (13) | 19.1 (9.3) | 2.06* |

| Perinatal conditions | 13 (20) | 5.5 (4.1) | 1.35* | 13 (20) | 4.9 (2.2) | 2.24* | 14 (22) | 4.7 (4.7) | 0.99 | 14 (23) | 3.9 (3.9) | 1.00 | 16 (23) | 4.8 (3.6) | 1.32* | 15 (21) | 3.5 (4.3) | 0.81 | 13 (22) | 4.6 (4.0) | 1.14* |

| Congenital malformations | 14 (18) | 5.7 (4.3) | 1.32* | 14 (15) | 5.3 (3.7) | 1.44 | 17 (21) | 4.9 (4.6) | 1.06 | 13 (22) | 5.2 (3.7) | 1.42* | 18 (22) | 4.0 (3.8) | 1.05 | 14 (22) | 4.0 (3.2) | 1.26 | 14 (21) | 5.0 (3.8) | 1.32* |

| HIV disease | 22 (24) | 3.2 (1.3) | 2.56* | 15 (22) | 4.9 (1.2) | 4.11* | 19 (23) | 5.7 (3.8) | 1.51* | 15 (20) | 5.7 (3.8) | 1.48* | 13 (20) | 7.3 (3.9) | 1.85* | 13 (18) | 6.6 (3.7) | 1.76* | 15 (20) | 5.6 (3.4) | 1.67* |

| Females | |||||||||||||||||||||

| All causes | 1243.4 (649.2) | 1.92* | 1041.2 (627.3) | 1.66* | 1116.3 (790.9) | 1.41* | 828.1 (670.4) | 1.24* | 1238.3 (933.7) | 1.33* | 735.4 (671.0) | 1.10* | 991.5 (678.6) | 1.46* | |||||||

| Cancer | 1 (2) | 246.9 (154.4) | 1.60* | 1 (1) | 232.6 (155.5) | 1.50* | 2 (2) | 221.1 (162.1) | 1.36* | 1 (2) | 125.9 (149.9) | 0.84* | 1 (1) | 309.2 (251.8) | 1.23* | 2 (2) | 141.6 (160.5) | 0.88* | 1 (2) | 185.8 (159.1) | 1.17* |

| Heart disease | 2 (1) | 249.0 (156.7) | 1.59* | 2 (2) | 172.9 (127.9) | 1.35* | 1 (1) | 282.4 (223.0) | 1.27* | 2 (1) | 137.8 (157.3) | 0.88* | 2 (2) | 233.8 (223.7) | 1.05 | 1 (1) | 180.3 (170.8) | 1.06 | 2 (1) | 204.8 (167.2) | 1.22* |

| Accidents | 3 (6) | 81.3 (25.9) | 3.14* | 3 (5) | 72.6 (27.7) | 2.62* | 3 (6) | 61.0 (34.3) | 1.78* | 3 (6) | 68.6 (32.5) | 2.11* | 3 (4) | 107.4 (53.0) | 2.03* | 4 (6) | 39.1 (24.7) | 1.58* | 3 (6) | 65.6 (27.0) | 2.43* |

| Diabetes mellitus | 4 (7) | 99.8 (19.5) | 5.11* | 9 (7) | 18.9 (20.6) | 0.92 | 4 (8) | 75.3 (22.1) | 3.40* | 4 (8) | 72.0 (13.9) | 5.19* | 6 (6) | 60.8 (25.1) | 2.43* | 3 (8) | 57.0 (15.1) | 3.77* | 4 (8) | 69.2 (17.1) | 4.04* |

| Stroke | 7 (3) | 63.9 (48.8) | 1.31* | 4 (3) | 71.2 (48.6) | 1.47* | 5 (3) | 72.4 (59.6) | 1.22* | 7 (4) | 38.0 (44.3) | 0.86* | 4 (10) | 46.2 (13.9) | 3.33* | 5 (3) | 48.3 (44.9) | 1.08 | 5 (3) | 58.9 (49.3) | 1.20* |

| Chronic liver disease | 5 (13) | 52.6 (5.2) | 10.20* | 6 (10) | 27.0 (6.2) | 4.36* | 8 (14) | 22.7 (6.5) | 3.51* | 5 (12) | 39.9 (6.9) | 5.75* | 8 (8) | 29.0 (24.3) | 1.19* | 7 (13) | 21.5 (6.1) | 3.55* | 6 (12) | 34.6 (6.4) | 5.36* |

| CLRD | 6 (4) | 72.9 (38.0) | 1.92* | 5 (4) | 64.1 (40.7) | 1.58* | 6 (4) | 53.0 (52.1) | 1.02 | 10 (3) | 17.5 (48.2) | 0.36* | 5 (3) | 74.5 (57.7) | 1.29* | 6 (4) | 32.1 (39.7) | 0.81* | 7 (4) | 45.4 (43.9) | 1.03 |

| Influenza and pneumonia | 9 (8) | 32.0 (16.6) | 1.92* | 8 (9) | 30.0 (11.3) | 2.66* | 9 (7) | 27.1 (21.4) | 1.27* | 6 (7) | 42.1 (17.7) | 2.38* | 7 (5) | 61.7 (54.1) | 1.14* | 10 (7) | 17.6 (17.5) | 1.01 | 8 (7) | 31.7 (17.2) | 1.84* |

| Kidney disease | 8 (9) | 34.3 (10.2) | 3.37* | 13 (11) | 13.6 (8.7) | 1.57* | 7 (9) | 27.3 (11.6) | 2.35* | 8 (9) | 28.7 (8.9) | 3.23* | 9 (21) | 13.5 (3.6) | 3.72* | 9 (9) | 18.6 (11.5) | 1.62* | 9 (9) | 25.0 (9.2) | 2.72* |

| Septicemia | 11 (11) | 19.4 (6.0) | 3.25* | 12 (13) | 13.9 (4.7) | 2.98* | 10 (10) | 21.2 (10.5) | 2.03* | 9 (10) | 21.5 (8.3) | 2.57* | 10 (9) | 25.4 (20.2) | 1.26* | 8 (10) | 18.4 (10.9) | 1.68* | 10 (10) | 18.6 (7.8) | 2.38* |

| Alzheimer’s disease | 12 (5) | 24.3 (27.8) | 0.87 | 11 (6) | 19.7 (27.6) | 0.71* | 11 (5) | 25.0 (25.4) | 0.98 | 13 (5) | 12.5 (30.3) | 0.41* | 12 (12) | 14.5 (8.7) | 1.66* | 11 (5) | 12.0 (22.5) | 0.53* | 11 (5) | 20.7 (28.4) | 0.73* |

| Suicide | 10 (18) | 11.9 (4.6) | 2.62* | 7 (8) | 19.3 (6.7) | 2.88* | 12 (16) | 6.9 (6.3) | 1.08 | 11 (11) | 6.8 (8.6) | 0.79* | 15 (17) | 9.1 (5.1) | 1.78* | 12 (18) | 4.1 (4.8) | 0.85 | 12 (16) | 8.7 (5.9) | 1.48* |

| Assault (homicide) | 15 (24) | 6.6 (1.4) | 4.59* | 10 (16) | 10.3 (2.4) | 4.28* | 17 (21) | 4.8 (2.7) | 1.74* | 12 (21) | 6.9 (2.4) | 2.82* | 16 (23) | 4.8 (3.6) | 1.32* | 17 (22) | 3.0 (1.8) | 1.66 | 13 (22) | 6.0 (1.9) | 3.24* |

| Congenital malformations | 13 (19) | 5.6 (3.8) | 1.46* | 14 (15) | 6.0 (2.9) | 2.08* | 16 (19) | 4.2 (4.4) | 0.96 | 14 (19) | 4.4 (3.1) | 1.41* | 18 (22) | 4.0 (3.8) | 1.05 | 16 (19) | 3.0 (3.0) | 0.97 | 14 (19) | 4.5 (3.4) | 1.30* |

| Hypertension | 16 (10) | 8.6 (6.2) | 1.38* | 20 (17) | 5.0 (3.8) | 1.31 | 13 (12) | 9.3 (6.4) | 1.45* | 15 (13) | 8.4 (5.7) | 1.47* | 13 (20) | 7.3 (3.9) | 1.85* | 14 (11) | 5.5 (6.1) | 0.91 | 15 (11) | 8.4 (6.6) | 1.28* |

Note. AI/AN = American Indian and Alaska Native; CHSDA = Contract Health Service Delivery Area; RR = rate ratio. All analyses were limited to people of non-Hispanic origin. Rank is based on total counts of deaths. Rates are per 100 000 people and were age adjusted to the 2000 US standard population (11 age groups; Census P25-1130). RR were calculated in SEER*Stat (version 8.0.4) before rounding of rates and may not equal RRs calculated from rates presented in table. IHS regions are defined as follows: Alaskab; Northern Plains (IL, IN,b IA,b MI,b MN,b MT,b NE,b ND,b SD,b WI,b WYb); Southern Plains (OK,b KS,b TXb); Southwest (AZ,b CO,b NV,b NM,b UTb); Pacific Coast (CA,b ID, b OR,b WA,b HI); East (AL,b AR, CT,b DE, FL,b GA, KY, LA,b ME,b MD, MA,b MS,b MO, NH, NJ, NY,b NC,b OH, PA,b RI,b SC,b TN, VT, VA, WV, DC). Percentage regional coverage of AI/AN persons in CHSDA counties to AI/AN persons in all counties: Northern Plains = 64.8%; Alaska = 100%; Southern Plains = 76.3%; Southwest = 91.3%; Pacific Coast = 71.3%; East = 18.2%; total US = 64.2%.

Source. AI/AN Mortality Supplement Database (1990–2009).

Descriptors for select 113 cause of death recodes have been shortened for greater clarity in the table: Heart disease = diseases of the heart; Cancer = malignant neoplasms; Accidents = unintentional injuries; Chronic liver disease = chronic liver disease and cirrhosis; Suicide = intentional self-harm; CLRD = chronic lower respiratory diseases; Stroke = cerebrovascular disease; Kidney disease = nephritis, nephrotic syndrome, and nephrosis; Perinatal conditions = certain conditions originating in the perinatal period; Congenital malformations = congenital malformations, deformations, and chromosomal abnormalities; Hypertension = essential hypertension and hypertensive renal disease.

Identifies states with ≥ 1 county designated as CHSDA.

*P < .05.

For AI/AN men, the leading 2 causes of death were diseases of the heart and cancer—ranked similarly in Whites. Though modestly elevated for AI/AN persons compared with Whites (22% and 11% greater, respectively) in relative terms, in absolute terms these differences are substantial and exceed the death rates for many other causes of death. The next 3 leading causes of death in AI/AN males—unintentional injury, diabetes, and chronic liver disease—were not similarly ranked in Whites (4th, 6th, and 10th, respectively) and the rates were several times higher in AI/AN persons compared with Whites. Of the remaining 10 leading causes of death in AI/AN males, we noted discrepancies in ranking for several causes of death, and RRs were significantly higher for all listed leading causes of death. Of particular note is homicide (9th in AI/ANs and 19th in Whites; RR = 4.85; 95% CI = 4.58, 5.13).

For AI/AN females, cancer was the leading cause of death followed by heart disease, the converse of White females. As in males, both causes of death were modestly elevated in AI/AN relative to White females (17% and 22%, respectively), a substantial difference in absolute terms. The 3rd through the 6th leading causes in AI/AN females—unintentional injuries, diabetes, stroke, and chronic liver disease—were ranked differently in Whites (6th, 8th, 3rd and 12th, respectively), with notable rate disparities for unintentional injury (RR = 2.43; 95% CI = 2.36, 2.51), diabetes (RR = 4.04; 95% CI = 3.91, 4.18), and chronic liver disease (RR = 5.36; 95% CI = 5.14, 5.60). Of the remaining leading causes of death in AI/AN females, only 1—chronic lower respiratory diseases—was not elevated in comparison with White females. Homicide was more than 3 times higher and kidney disease and septicemia were more than 2 times higher in AI/AN versus White females.

Figure 1 summarizes trends in all-cause mortality in CHSDA counties from 1990 to 2009 for all regions combined for AI/AN and White males and females. All-cause death rates remained stable for AI/AN males, whereas for White males, death rates declined 1.3% per year. A pairwise comparison determined that the 2 trends are not parallel, with a significant difference between the average annual percentage change for AI/AN and White males. AI/AN females experienced an increase of 0.5% per year, whereas the rate for White females decreased by a similar annual percentage. We found that these all-cause mortality trends for AI/AN and White females were also nonparallel.

DISCUSSION

Key findings in this article provide information that may be useful to the public health, health care, and health policy communities serving AI/AN populations. First, AI/AN all-cause death rates are substantially greater than those for Whites, most notably in the Northern Plains and the Southern Plains. Second, the most prominent disparities for all-cause death rates are concentrated in the younger age groups. Third, the significant decrease in all-cause death rates experienced over the past 2 decades by the White population was not shared by the AI/AN population. Finally, the leading specific cause-of-death and age-at-death disparities indicate potential areas of intervention that can improve the mortality disparities in this population.

Despite these findings, it is important to acknowledge the substantial progress made over the past century by targeting resources toward AI/AN communities and by placing great emphasis on public health interventions, such as immunization, sanitation, and maternal and child health programs, as integral parts of the IHS.1 Nonetheless, these data paint an unfavorable and disturbing picture of the mortality disparity in the AI/AN population, affecting particularly the younger age groups. After dramatically improving AI/AN mortality for much of the 20th century, the situation changed in the 1980s,23 and death rates have either stagnated or worsened since 1990, as reported here. Kunitz25 suggested that this reversal of trend is a result of the increasing burden of diabetes and lung cancer as well as inadequate funding for IHS and tribal health programs. A few common factors are likely responsible for most of these death rate disparities.

Social Determinants

Social determinants of health—defined by the World Health Organization26 as “the circumstances in which people are born, grow up, live, work and age, and the systems put in place to deal with illness”—are often the most difficult to address. They also offer the potential for greatest impact.27 On average, AI/AN persons are more likely than Whites to be poor, be unemployed, and have a lower level of educational attainment.28,29 Many live in rural areas where employment is often seasonal and dangerous, such as wildland firefighting and commercial fishing.30 These factors all contribute to a high incidence of deaths resulting from unintentional injury.31 These social factors combined with the cultural devastation most tribes experienced in the past 150 years resulted in understandably high homicide and suicide rates.32 Abuse of alcohol and other drugs compounds the problem of injury, both intentional and unintentional, and contributes to high rates of death from chronic liver disease.33–35 Approaches to improving social determinants usually focus on economic development and education and seek to support a culture of empowerment and self-efficacy. Community participation is particularly important to address prominent issues such as health disparities and could be more widely implemented in AI/AN populations. Involving the community utilizes inherent strengths and assets and increases the likelihood that changes can be sustained. Successful approaches include community-based participatory research, community-oriented primary care, and the development of peer educator systems.

Obesity, Inactivity, and the Metabolic Syndrome

A combination of genetics, diet, and physical inactivity seems to predispose AI/AN individuals to obesity and diabetes and the metabolic syndrome,36–38 which in turn drive the increased incidence of death from heart disease, stroke, chronic renal failure, and serious infections.39 Elsewhere in this supplement, Cobb et al.29 report on the generally elevated prevalence of these risk factors, as well as self-report of history of diabetes in AI/AN persons compared with Whites, and Cho et al.40 describe the impact of high diabetes prevalence on mortality.

Tobacco and Alcohol Use

Extremely high smoking prevalence among AI/AN persons in most of the country29 further complicates the vascular effects of the metabolic syndrome and contributes to increased rates of cardiovascular disease.41–43 Tobacco use also drives the high rate of death from lung cancer and a long list of other cancers,44–46 and it is the single most important cause of preventable mortality among AI/AN populations. Cultural factors, such as the role of tobacco in traditional beliefs and ceremonies, make tobacco control a challenging issue. However, substantial progress has been made in reducing tobacco use in the United States by implementing system, environmental, and policy changes known to decrease initiation of tobacco use and increase successful cessation.47 This has resulted in overall reductions in lung cancer mortality.48 To achieve similar results, tribal governments should consider adopting similar approaches, taking into account the complex social and environmental determinants of tobacco use that may be unique to AI/AN populations. Occupational exposure to secondhand smoke is a particularly compelling area given the limited implementation of smoke-free environments in casinos and gaming parlors.49

As reported elsewhere in this supplement, mortality attributable to alcohol is substantially elevated in AI/AN communities relative to Whites and plays a key role in elevated death rates for multiple chronic conditions as well as injury and exposure.35 Strategies to reduce or eliminate consumption of alcohol are critical to addressing its enormous personal and societal toll. For those unable or unwilling to avoid problem drinking, measures to make the environment less dangerous, such as improved lighting of roadways and protective custody programs, should be promoted.

Access to Care

AI/AN people continue to have difficulty getting high-quality, timely health care.50,51 Rural living and limited prehospital care prolong the time to treatment, increasing death rates from accidents and acute illness.52 Insufficient funding for IHS leads to delays and deficiencies in preventive services, primary treatment, and specialist care.50 Access-to-care issues likely contribute to the observed disparities between AI/AN and White persons in cancer survival,45 heart disease mortality,42 and diabetes mortality.40

Recent developments offer some cause for optimism. The Indian Health Care Improvement Act was permanently reauthorized in 2010, which will help modernize the IHS and improve reimbursement from third-party payers.53 After the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act in 1988, revenues from tribal gaming increased considerably. Wolf et al.54 studied the effect of gaming on income and health status of gaming tribes, providing evidence of a positive effect of gaming on income and on several indicators of AI/AN health, health-related behaviors, and access to health care.

Limitations

Several limitations should be considered when interpreting the results presented in this article. First, although linkage with the IHS patient registration database improves the classification of race for AI/AN decedents, the issue is not completely resolved because AI/AN people who are not members of the federally recognized tribes are not eligible for IHS services and not represented in the IHS database. Additionally, some decedents may have been eligible for but never used IHS services, and therefore were not included in the IHS registration database. Second, substantial variation exists between federally recognized tribes in the proportion of Native ancestry required for tribal membership and therefore for eligibility for IHS services. Whether and how this discrepancy in tribal membership requirements may influence some of our findings is unclear, although our findings are consistent with prior reports. Third, the findings from CHSDA counties highlighted in this supplement do not represent all AI/AN populations in the United States or in individual IHS regions.6 In particular, the East region includes only 15.4% of the total AI/AN population for that region. Furthermore, the analyses based on CHSDA designation exclude many AI/AN decedents in urban areas that are not part of a CHSDA county. AI/AN residents of urban areas differ from all AI/AN persons in poverty level, health care access, and other factors that may influence mortality trends.55 Finally, although the exclusion of Hispanic AI/ANs from the analyses reduces overall AI/AN deaths by less than 5%, it may disproportionately exclude some tribal members who have Hispanic surnames and may be coded as Hispanic at death in states along the US–Mexico border and in other areas in the Southwest, Pacific Coast, and Southern Plains.

Conclusions

This article contains the best available data on deaths among AI/AN persons between 1990 and 2009. Using much more accurate racial ascertainment in death records, we have shown that the disparity in death rates between AI/AN and non-Hispanic White populations in the United States remains large for most causes of death. A concerted, robust public health effort by federal, tribal, state, and local public health agencies, coupled with attention to social and economic disparities, may help narrow the gap.

Acknowledgments

We thank Steve Scoppa of IMS and Ashwini Soman of the CDC’s Division of Cancer Prevention and Control for their valuable assistance creating analytic files and data tables.

Human Participant Protection

The CDC and the IHS determined this project to constitute public health practice and not research; therefore, no formal institutional review board approvals were required.

References

- 1.Rhoades ER, Rhoades DA. The public health foundation of health services for American Indians and Alaska Natives. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(6 suppl 3):S278–S285. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Denny CH, Holtzman D, Cobb N. Surveillance for health behaviors of American Indians and Alaska Natives: findings from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, 1997–2000. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2003;52:1–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Indian Health Service. Trends in Indian Health, 2002-2003 Edition. Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Murphy SL, Xu J, Kochanek KD. Deaths: final data for 2010. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2013;61(4) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arias E, Schauman WS, Eschbach K, Sorlie PD. The validity of race and Hispanic origin reporting on death certificates in the United States. Vital Health Stat 2. 2008;2(148) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Espey DK, Jim MA, Richards T, Begay C, Haverkamp D, Roberts D. Methods for improving the quality and completeness of mortality data for American Indians and Alaska Natives. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(6 suppl 3):S286–S294. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ingram DD, Parker JD, Schenker N et al. United States Census 2000 population with bridged race categories. Vital Health Stat 2. 2003;2(135):1–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.National Vital Statistics System. US Census populations with bridged race categories. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/bridged_race.htm. Accessed February 15, 2013.

- 9.National Cancer Institute Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program. Adjusted populations for the counties/parishes affected by Hurricanes Katrina and Rita. Available at: http://seer.cancer.gov/popdata/hurricane_adj.html. Accessed February 15, 2013.

- 10.Edwards BK, Noone AM, Mariotto AB et al. Annual Report to the Nation on the status of cancer, 1975–2010, featuring prevalence of comorbidity and impact on survival among persons with lung, colorectal, breast, or prostate cancer. Cancer. 2013 doi: 10.1002/cncr.28509. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Division of Vital Statistics. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2012. National Vital Statistics System. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss.htm. Accessed December 15, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Division of Vital Statistics. NCHS Procedures for Multiple-Race and Hispanic Origin Data: Collection Coding, Editing, and Transmitting. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 13. SEER*Stat [computer program]. Version 8.0.4. 2013. Available at: http://seer.cancer.gov/seerstat. Accessed May 30, 2013.

- 14.International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 15.International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Anderson RN, Minino AM, Hoyert DL, Rosenberg HM. Comparability of cause of death between ICD-9 and ICD-10: preliminary estimates. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2001;49(2):1–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Heron M. Deaths: Leading causes for 2009. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2012;61(7):1–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Espey DK, Jim MA, Cobb N et al. Leading causes of death and all-cause mortality in American Indians and Alaska Natives. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(6 suppl 3):S303–S311. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Denny CH, Taylor TL. American Indian and Alaska Native health behavior: findings from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, 1992–1995. Ethn Dis. 1999;9(3):403–409. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wiggins CL, Espey DK, Wingo PA et al. Cancer among American Indians and Alaska Natives in the United States, 1999–2004. Cancer. 2008;113(5 suppl):1142–1152. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Espey D, Paisano R, Cobb N. Regional patterns and trends in cancer mortality among American Indians and Alaska Natives, 1990–2001. Cancer. 2005;103(5):1045–1053. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Anderson R, Rosenberg H. Report of the second workshop on age adjustment. Vital Health Stat 4. 1998;4(30):37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tiwari RC, Clegg LX, Zou Z. Efficient interval estimation for age-adjusted cancer rates. Stat Methods Med Res. 2006;15(6):547–569. doi: 10.1177/0962280206070621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim HJ, Fay MP, Feuer EJ, Midthune DN. Permutation tests for joinpoint regression with applications to cancer rates. Stat Med. 2000;19(3):335–351. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(20000215)19:3<335::aid-sim336>3.0.co;2-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kunitz SJ. Ethics in public health research: changing patterns of mortality among American Indians. Am J Public Health. 2008;98(3):404–411. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.114538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Commission on Social Determinants of Health. Closing the Gap in a Generation: Health Equity Through Action on the Social Determinants of Health. Final Report of the Commission on Social Determinants of Health. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Galea S, Tracy M, Hoggatt KJ, Dimaggio C, Karpati A. Estimated deaths attributable to social factors in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2011;101(8):1456–1465. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2010.300086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kunitz SJ, Veazie M, Henderson J. Historical trends and regional differences in all-cause and amenable mortality among American Indians and Alaska Natives since 1950. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(6 suppl 3):S268–S277. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cobb N, Espey D, King J. Health behaviors and risk factors among American Indians and Alaska Natives, 2000–2010. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(6 suppl 3):S481–S489. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.301879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lincoln JM, Lucas DL. Occupational fatalities in the United States commercial fishing industry, 2000–2009. J Agromedicine. 2010;15(4):343–350. doi: 10.1080/1059924X.2010.509700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Murphy TM, Pokhrel P, Worthington A, Billie H, Sewell M, Bill N. Unintentional injury mortality among American Indians and Alaska Natives in the United States, 1990–2009. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(6 suppl 3):S470–S480. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Herne MA, Bartholomew ML, Weahkee RL. Suicide mortality among American Indians and Alaska Natives, 1999–2009. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(6 suppl 3):S336–S342. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.301929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Suryaprasad A, Byrd KK, Redd JT, Perdue DG, Manos MM, McMahon BJ. Mortality caused by chronic liver disease among American Indians and Alaska Natives in the United States, 1999–2009. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(6 suppl 3):S350–S358. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Alcohol-attributable deaths and years of potential life lost among American Indians and Alaska Natives—United States, 2001–2005. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2008;57(34):938–941. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Landen M, Roeber J, Naimi T, Nielsen L, Sewell M. Alcohol-attributable mortality among American Indians and Alaska Natives in the United States, 1999–2009. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(6 suppl 3):S343–S349. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schumacher C, Ferucci ED, Lanier AP et al. Metabolic syndrome: prevalence among American Indian and Alaska Native people living in the southwestern United States and in Alaska. Metab Syndr Relat Disord. 2008;6(4):267–273. doi: 10.1089/met.2008.0021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sinclair KA, Bogart A, Buchwald D, Henderson JA. The prevalence of metabolic syndrome and associated risk factors in Northern Plains and Southwest American Indians. Diabetes Care. 2011;34(1):118–120. doi: 10.2337/dc10-0221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wiedman D. Native American embodiment of the chronicities of modernity: reservation food, diabetes, and the metabolic syndrome among the Kiowa, Comanche, and Apache. Med Anthropol Q. 2012;26(4):595–612. doi: 10.1111/maq.12009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Russell M, de Simone G, Resnick HE, Howard BV. The metabolic syndrome in American Indians: the Strong Heart Study. J Cardiometab Syndr. 2007;2(4):283–287. doi: 10.1111/j.1559-4564.2007.07457.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cho P, Geiss LS, Rios-Burrows N, Roberts DL, Bullock AK, Toedt ME. Diabetes-related mortality among American Indians and Alaska Natives, 1999–2009. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(6 suppl 3):S496–S503. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.301968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schieb LJ, Ayala C, Valderrama AL, Veazie MA. Trends and disparities in stroke mortality by region for American Indians and Alaska Natives. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(6 suppl 3):S359–S367. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Veazie M, Ayala C, Schieb L, Dai S, Henderson J, Cho P. Trends and disparities in heart disease mortality among American Indians and Alaska Natives, 1990–2009. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(6 suppl 3):S359–S367. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Galloway JM. Cardiovascular health among American Indians and Alaska Natives: successes, challenges, and potentials. Am J Prev Med. 2005;29(5 suppl 1):11–17. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2005.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Plescia M, Henley SJ, Pate A, Underwood JM, Rhodes K. Lung cancer deaths among American Indians and Alaska Natives, 1999–2009. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(6 suppl 3):S388–S397. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Singh SD, Ryerson AB, Wu M, Kaur JS. Ovarian and uterine cancer incidence and mortality in American Indian and Alaska Native women, United States, 1999–2009. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(6 suppl 3):S423–S431. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health. The Health Consequences of Smoking: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Quitting smoking among adults—United States, 2001–2010. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2011;60(44):1513–1519. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jemal A, Thun MJ, Ries LA et al. Annual report to the nation on the status of cancer, 1975–2005, featuring trends in lung cancer, tobacco use, and tobacco control. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100(23):1672–1694. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.American Cancer Society Cancer Action Network. Secondhand Smoke and Casinos. Atlanta, GA: American Cancer Society; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Warne D, Frizzell LB. American Indian health policy: historical trends and contemporary issues. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(6 suppl 3):S263–S267. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Roubideaux Y, Dixon M. Promises to Keep: Public Health Policy for American Indians and Alaska Natives in the 21st Century. Washington, DC: American Public Health Association; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Williams JM, Ehrlich PF, Prescott JE. Emergency medical care in rural America. Ann Emerg Med. 2001;38(3):323–327. doi: 10.1067/mem.2001.115217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.US Department of Health and Human Services. Indian Health Care Improvement Act Made Permanent. 2010. Available at: http://www.hhs.gov/news/press/2010pres/03/20100326a.html. Accessed June 21, 2013.

- 54.Wolfe B, Jakubowski J, Haveman R, Courey M. The income and health effects of tribal casino gaming on American Indians. Demography. 2012;49(2):499–524. doi: 10.1007/s13524-012-0098-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Urban Indian Health Institute, Seattle Indian Health Board. Reported Health and Health-influencing Behaviors Among Urban American Indians and Alaska Natives: An Analysis of Data Collected by the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. Seattle, WA: Urban Indian Health Institute; 2008. [Google Scholar]