Abstract

The integration of public health practices with federal health care for American Indians and Alaska Natives (AI/ANs) largely derives from three major factors: the sovereign nature of AI/AN tribes, the sociocultural characteristics exhibited by the tribes, and that AI/ANs are distinct populations residing in defined geographic areas. The earliest services consisted of smallpox vaccination to a few AI/AN groups, a purely public health endeavor. Later, emphasis on public health was codified in the Snyder Act of 1921, which provided for, among other things, conservation of the health of AI/AN persons. Attention to the community was greatly expanded with the 1955 transfer of the Indian Health Service from the US Department of the Interior to the Public Health Service and has continued with the assumption of program operations by many tribes themselves. We trace developments in integration of community and public health practices in the provision of federal health care services for AI/AN persons and discuss recent trends.

During the past 150 years, the development of federal health services for American Indians/Alaska Natives (AI/ANs, or Indians) underwent several transformations, each remarkable in the degree to which public health practices were used. Such services were initially minimal and varied, and developed through often vaguely worded treaties and subsequent legislative acts. From these modest beginnings evolved a federal system of health care now administered through the Indian Health Service (IHS). A distinguishing feature of the IHS is the integration of public health practices with clinical services for several hundred AI/AN communities across the country. In this article, we briefly examine the development of public health practices in this national health care system.

POLITICAL AND SOCIal INFLUENCES ON HEALTH CARE

Three major political and social situations significantly influenced the configuration of health services for AI/AN populations. First was the sovereign nature of the tribes.1 This required that implementation of federal programs, including health, be negotiated with each group. Second, substantial variations in the geographic, social, and cultural characteristics of tribes2 called for local flexibility in program design and operation. Third, in spite of many challenges, implementation of public health services was facilitated by the fact that AI/AN communities are distinct populations residing in defined geographic areas. As a result of these several factors, a community emphasis was inherent in AI/AN health programs from the beginning. This community emphasis undoubtedly played a significant role in many tribes ultimately operating their own programs.

INFLUENCE OF DISEASE ON HEALTH SERVICES

Although the political and geocultural considerations we have noted greatly influenced program design, devastating epidemics of infectious diseases3,4 provided the initial impetus for coordinated delivery of health services on a public health scale. Principal among these were smallpox, cholera, trachoma, gastroenteritis, and, later, tuberculosis. Particular concern was directed toward the extent of childhood gastroenteritis, often associated with dramatically high mortality rates. Each epidemic called for particular public health interventions: immunizations, sanitation, safe water, safe food, and case finding and effective therapy. Many of these challenges had to be addressed before the concepts of contagion were fully developed and before the great advances in microbiology had occurred.5–7

EVOLUTION OF INDIAN HEALTH PROGRAMS

The development of health care programs for AI/AN populations may be divided into 3 periods: the US Department of War era (roughly 1800–1849), the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) era (1849–1955), and the Indian Health Service (IHS) era (1955–present).

US Department of War Era (1800–1849)

Federal involvement in Indian affairs was originally administered by the US Department of War and centered on the regulation of trade and maintenance of peace. The health of AI/AN persons was not a consideration except for 1 dramatic condition: smallpox, the major scourge affecting the entire population dating to precolonial times.8 The effects of smallpox were so devastating for AI/AN persons that many citizens lobbied for national attention to the need for community members to receive vaccinations. The result was an 1832 congressional appropriation of $12 000 to provide smallpox vaccinations for AI/AN persons.9,10 This funding permitted several vaccination programs, carried out by contract physicians among tribes of the upper Midwest and the lower Missouri River region and those undergoing removal to the Indian Territory. An additional 1839 appropriation of $5000 extended these efforts, leading to the vaccination of an estimated 38 745 individuals from 1832 to 1841.11

Thus, the beginning of federal health care for AI/AN persons may be taken as the War Department’s smallpox campaign, a public health intervention that appears to have been based on humanitarian concerns on the part of many leading citizens and not solely for the protection of soldiers. The smallpox campaign may be viewed as a stepping stone for the later inclusion of physician services in treaties between the federal government and tribes, which intensified during this period. Language in treaties of the period provides a brief view of the generation of health care services. For example, the 1820 treaty with the Choctaw nation provided that

in order that justice may be done to the poor and distressed of said nation, it shall be the duty of the agent to see that the wants of every deaf, dumb, blind and distressed Indian shall be first supplied out of said annuity, and the balance equally distributed amongst every individual of said nation.12

The 1832 Winnebago treaty was more explicit:

And the United States further agree to make to the said nation of Winnebago Indians, the following allowances, . . . for the services and attendance of a physician at Prairie du Chien, and of one at Fort Winnebago, each, two hundred dollars, per annum.13

Bureau of Indian Affairs Era (1849–1955)

Until the mid-19th century, administration of health services for AI/AN persons was neither systematic nor organized into a single program. With the 1849 transfer of Indian affairs from the US Department of War to the newly established US Department of the Interior, federal attention to AI/AN health care services became more systematic. The BIA era, which lasted approximately a century, may be considered in two phases: (1) the reservation period (1849–1900) and (2) the postallotment period (1900–1955). These phases are not precise, but they are convenient to describe the development of health services for AI/AN populations and the ultimate creation of the present IHS. This era is also noted for greatly increased attention to public health by the entire country, with many applications for AI/AN communities.

Home visits by public health nurses have long been mainstays of American Indian and Alaska Native health care.

The Reservation Period (1849–1900).

This first period of time was marked by three characteristics: (1) treaties placing responsibility for Indian health care with the federal government, (2) establishment of an Office for Health Administration, and (3) insufficient and unevenly distributed services.

Health concerns remained dominated by smallpox and the need for expansion of vaccination programs. As late as 1858, US Army officers and Indian agents requested funds to carry out additional vaccinations. The Commissioner of Indian Affairs responded by contracting with physicians who were then assigned to military posts under the supervision of the commissioner.10,11 These physicians may well be thought of as the original IHS staff.

Although treaty obligations during this period extended federal responsibility beyond smallpox vaccination, other health services were minimal, were spottily distributed, and usually consisted of a single physician with heavy responsibilities but very limited resources. Provision for constructing hospitals was sometimes made, as reflected in the 1855 Rogue River Tribe treaty.14 More systematic management of AI/AN medical services began in 1873 with the establishment of a Division of Education and Medicine.15

The increasing scope of federal health care for AI/AN populations included a striking emphasis on public health measures as reflected in the qualifications required for appointment of BIA physicians:

Treating Indian patients who called at his office and those who remained at camp; giving instruction in hygiene; acting as public health inspector; making regular visits to the Indian schools to treat students and instruct them in basic physiology and hygiene; and making monthly sanitary reports to the Indian Commissioner and quarterly reports of medical property to the agent.15(p319)

Subsequent instructions were more explicit regarding public health responsibilities of agency physicians. For example, an 1889 notice to physicians applying for appointment stated,

The Agency physician is required not only to attend Indians who may call upon him at his office, but also to visit the Indians at their homes and, in addition to prescribing and administering needed medications, to do his utmost to educate and instruct them in proper methods of living and caring for health . . . He should exercise special care in regard for sanitary conditions of the agency and the schools and promptly report to the agent, any condition, either of buildings or grounds, liable to cause sickness, in order that proper steps may be taken to remedy the evil [emphasis added]. . . . The physician is required to make regular visits to the Indian schools, and during such visits he should give short talks to the pupils on the elementary principles of physiology and hygiene, explaining in a plain and simple manner the processes of digestion and the assimilation of food, the circulation of the blood, the functions of the skin, etc., by which they may understand the necessity for proper habits of eating and drinking, for cleanliness, ventilation,

and other hygienic conditions.16(pp12–13)

Although the impact of smallpox commanded public attention and comment, other challenging infections called for different public health approaches. Malaria was a particular concern in many localities. For example, in his August 1877 report, the Wichita Agency physician reported treating 33 individuals for quotidian intermittent fever and 130 individuals for tertian intermittent fever.17 Occasionally, the nature of seasonal outbreaks of malaria and their association with low-lying areas suggested that some intervention might be possible. However, effective intervention had to await identification of the malaria parasite and its mode of transmission. Another example of the importance of communicable diseases was noted in 1881 when 108 males and 115 females were treated for pertussis between the months of August and December.18

Post-Allotment Period (1900–1955).

The second period of BIA health care roughly coincided with the advent of the 20th century. A cardinal event was the 1911 congressional appropriation of $40 000 specifically for health care. This date is taken as the date when the Congress began to make appropriations specifically for health care for AI/AN populations. Before this time, modest funding for health services was made from general or education funds.19

During this time, infectious diseases continued to be dominant causes of morbidity and mortality for AI/AN communities, as they did among the general population. Tuberculosis had become a national epidemic, receiving attention similar to that given to smallpox in the previous century. Also by this time, the science of public health practices had become more effective. These advances included case finding, construction of sanitaria (largely for quarantine), and the advent of immunization with Bacille Calmet-Guerin and effective antimicrobial therapy. Similar approaches were applied to another major contagious disease: trachoma. Its epidemic nature among youths led to case finding and quarantine, including establishment of schools for children with the disease. Despite intensive efforts, effective control of trachoma was not possible until the advent of sulfonamide therapy in the mid-1930s.20

Even after the advent of antibiotic therapies, prevention of these communicable diseases was not entirely successful until community efforts were implemented after the 1955 transfer of IHS to the US Department of Health, Education, and Welfare. The public health approaches to trachoma and tuberculosis also brought into play another major advance: collaboration between the BIA, volunteer organizations (e.g., the National Tuberculosis Association), interested individuals, and researchers.

The next cardinal event in AI/AN health care was the 1921 Snyder Act, a law authorizing appropriations and expenditures for the administration of Indian affairs, and for other purposes.21 This act provided specific congressional authorization for health care for AI/AN populations and also laid out the parameters of subsequent federal AI/AN health policy. The effect of the Snyder Act is well known and need not be further remarked on except to note the language authorizing the expenditure of appropriated funds for “relief of distress and conservation of health [emphasis added] of Indians throughout the United States.”21 This language codified the long-standing emphasis on public health principles and anticipated by several decades the general population’s movement toward wellness and health promotion programs.

The extent of environmental deficiencies adversely affecting community health was noted as early as 1912, especially the serious lack of sanitation facilities and safe water.22 The plea for congressional support for health care, especially of the very young, was emphasized in the 1916 Annual Report of the Commissioner of Indian Affairs:

A determined fight has been made for preventive measures against disease on Indian reservations. . . . The greatest problems confronting us are tuberculosis, trachoma, and a high infant mortality. . . . Statistics startle us with the fact that approximately three-fifths of the Indian infants die before the age of 5 years.23(p4–5)

The commissioner proposed a campaign for women and children’s health, which eventually became a prominent hallmark of the IHS. Such advocacy facilitated several innovations, one of which was bringing health education and some services into individual homes. Although not readily quantifiable, the benefits of this unique home health care program can only have had enormous benefits for individuals and communities. These duties were subsequently taken over and expanded by public health nurses, another program integrated into overall clinical care (Figure 1).

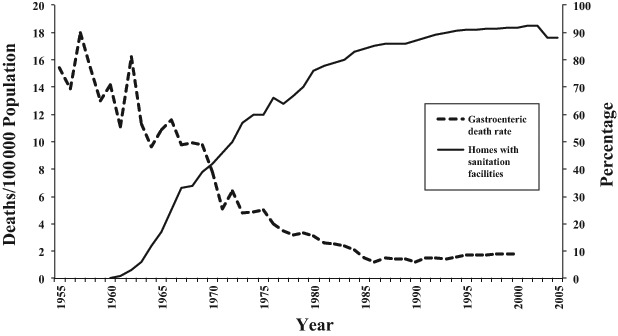

FIGURE 1—

Inverse relationship between sanitation facility construction and reductions in infant mortality.

The post-allotment era was also characterized by a number of important community health surveys. The 1927 water and sewage survey carried out with the assistance of the US Public Health Service Sanitary Engineering Corps resulted in construction of water systems for New Mexico Pueblo Tribes and California Rancherias. This modest effort laid the foundation for sweeping sanitation efforts implemented later. One of the best-known surveys is the Meriam Report of 1928,24 which described inadequate and crowded dwellings, lack of safe and potable water, and inadequate facilities for waste disposal. The Mountin and Townsend survey of 1936,25 however, called attention to major gains in certain BIA prevention programs and to the fact that such services not infrequently exceeded those available to the rest of the country. These surveys led to a number of improvements such as construction of outside privies and wells to provide safe water. They also provided increased attention to childhood immunizations, often producing higher rates of immunization for AI/AN students than for their non-AI/AN schoolmates.

Part of the genius of the Indian Health Service is the incorporation of provision of safe water with clinical services.

These reports also anticipated another fundamental concept: greater participation of individuals and communities in their own programs, a concept not adopted by the general population for several decades. Such a movement had been heralded by an important demonstration on the Navajo Reservation. In the early 1950s, the Cornell University Many Farms Project,26 an outgrowth of tuberculosis therapy studies, showed the value of employing local Indigenous community workers in health programs. Concomitant with the Many Farms project, the BIA began modest efforts at employing local AI/AN health aides.10 These different developments later became embodied in the IHS as the Community Health Representative program.

Even with these advances, overall expansion of health programs remained slow and incremental, primarily the result of serious underfunding by Congress. Competing non–health care programs, insufficient resources, continued unsatisfactory sanitation facilities, and lack of safe water for AI/AN communities, combined with stubbornly persistent high rates of tuberculosis and other communicable diseases, led to suggestions to place jurisdiction over AI/AN health in an agency other than the US Department of the Interior. These recommendations took place during a period of heightened interest in assimilation of AI/AN persons into the general population, and some advocates recommended moving administration of AI/AN health services from the federal arena to the respective states. However, the latter having opposed this, in 1954 the Congress passed the Indian Health Transfer Act, a law to transfer the maintenance and operation of hospital and health facilities, among other purposes,27 and the following year the administration of AI/AN health care was transferred from the BIA to the newly organized IHS in the US Department of Health, Education, and Welfare.28

Indian Health Service Era (1955–Present)

Among the most important events influencing Indian health services was the 1955 transfer of federal responsibility from the US Department of the Interior to the US Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, where the IHS eventually became one of nine agencies of the US Public Health Service. The effect of the transfer was immediate; Congress doubled the appropriations for the IHS from $18 million to $36 million. Another fortunate result of the transfer was the appointment of Dr. James Ray Shaw as director. He is quoted as often remarking on a Chinese proverb: “Tell me, I’ll forget; show me, I may remember, but involve me and I’ll understand.” He also stated that his top goals were to do things with people, not to them, and to control tuberculosis. On the basis of Shaw’s philosophy, the IHS began training programs for staff in what would now be considered cross-cultural medicine and also “taught the joint practice of public health and medical care [emphasis added].”7(p139) One of the first initiatives of the new director was to secure passage of the 1959 Sanitation Facilities Construction Act,29 which restored authority for construction of sanitation facilities that had not been included in the Transfer Act. Furthermore, the law greatly fostered community involvement by requiring that the Public Health Service “consult with and encourage the participation of Indians in the development of sanitation projects,”30(p2) which stimulated the provision of safe water and waste disposal, programs vital to the improvements in rates of infant and childhood mortality from gastroenteritis. The importance of safe water was recognized by the IHS, as demonstrated by the choice of a water pump as its icon.

This period is also marked by the virtual control of most infectious diseases, resulting in the relatively greater prominence of both behavioral and chronic degenerative disease risks as public health concerns. As previously noted, a major success of the IHS was the reduction of gastroenteritis deaths, primarily of infants and children, a result of the integration of sanitation programs with improved clinical care including antimicrobials and fluid and electrolyte management.

During this era, the proliferation of tribal and community advisory health boards helped emphasize the health of communities as well as of individuals.31 Collaborations among the IHS, tribes, other federal agencies such as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the National Institutes of Health, and voluntary health organizations such as the American Heart Association, and many others followed the examples begun with trachoma and tuberculosis. A recent example of local collaboration is the Central Navajo Public Health Consortium, championed by an IHS pediatrician at the Chinle Service Unit.

Building on the momentum to increase tribal involvement were the 1975 Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act32 and the 1976 Indian Health Care Improvement Act.33 Each of these fostered the movement toward greater community involvement, local initiatives, and assumption of program management by tribes themselves.

RECENT TRENDS

Although AI/AN health remains a federal responsibility, after the 1970s legislation and subsequent amendments, authority for health programs in many cases shifted to local tribal management. Tribes operating their own systems are referred to as the Compact Tribes, reflecting the instrument used in their assumption of program operation. The remaining tribes, designated the Direct Services Tribes, choose to receive services directly from the federal government. A third component of the overall IHS program is the urban program serving the increasing population of AI/AN individuals residing in metropolitan areas. As a result of these developments, IHS programs are now often referred to as IHS (I)/Tribal (T) and Urban (U), or simply I/T/U programs (http://www.ihs.gov). As of October 1, 2011, the IHS directly operated 68 service units (the local administrative entity), and the tribes operated 94; the IHS operated 29 hospitals, and the tribes operated 16.34 Experience suggests that preventive services remain high priorities after this change in the organization of AI/AN health services.

The IHS budget for fiscal year 2012 was $5 385 744 000. Of this, $147 023 000 was identified specifically for preventive health services, including public health nursing, health education, community health representative program, and the Alaska immunization program. However, the total public health efforts extend far beyond these budget items. For example, an additional $79 582 000 was for construction of sanitation facilities and an additional $199 413 000 for facilities and environmental health support. It is not possible to estimate the extent of public health practices that are carried out through the funding provided through the IHS Clinical Services Account, the fiscal year 2012 total of which was $3 083 867 000.34

CONCLUSIONS

The history of Indian health care services discloses how prominently public health concepts and practices shaped the present configuration of the IHS, with its continued emphasis on prevention and public health. Indeed, one may with some justification describe the IHS as a program of public health supported by individual clinical care, hearkening to the 1936 Mountin and Townsend report that stipulated that “the entire service should be thought of as preventive in character and the Indian be made an active participant [emphasis added]”.25(p40) It is perhaps too simplistic to assert that the smallpox vaccination program was responsible for the ultimate emphasis on public health principles in the formation of Indian health services. However, it is of some interest that the initial efforts to provide federal health care for AI/AN populations were purely public health in nature. Over the years, many special preventive programs have been added, such as health education, environmental health programs, and facility construction. A major key in IHS successes has surely been the integration of these disparate programs into a single overall health agency. An additional important aspect of this success has been the ability to carry out these activities in a decentralized fashion in conjunction with hundreds of sovereign nations across the United States. The many successful adaptations to unique geographic, social, cultural, and political distinctions among widely dispersed and varied tribes and communities have been remarkable.

Successes have been achieved in a wide array of medical conditions, as reflected in reduced mortality rates.35,36 A review of historical trends indicates that these successes derived from extension and elaboration of basic public health practices and programs that took shape beginning with the earliest federal efforts to conserve the health of Indian people. In some instances, inclusion of these concepts in specific health legislation predated similar emphases among the general population by several decades.

Despite these successes, overall mortality rates for AI/AN populations during recent decades have not continued to fall. Important conditions such as injuries, behavioral problems, and chronic diseases are now leading causes of death and premature mortality rather than infectious diseases. The challenges posed by these conditions are more intractable than those of communicable diseases and less amenable to purely public health intervention such as construction of safe water facilities. Greater active involvement of individuals themselves will be necessary to reduce morbidity- and mortality-associated behavior and personality and mental disturbances.37,38

The IHS remains a useful model in which to examine the operation of a nationally integrated health program truly implementing community-oriented primary care with a focus on public health principles and practices. A prominent part of the successes of the IHS has been its insistence on a philosophy of placing the greatest possible authority at the local level. There is no reason to expect less emphasis on public health principles in the future. The IHS Strategic Plan 2006–201139 lists three strategic goals: (1) build and sustain healthy communities; (2) provide accessible, quality health care; and (3) foster collaboration and innovation across the Indian Health Network. The first of these includes the statement

To achieve this goal, the Indian health system will mobilize and involve AI/AN communities to promote wellness and healing, develop public health infrastructure with Tribes to sustain and support AI/AN communities, assist AI/AN communities in identifying and resolving community problems by improving access to data and information, and strengthening emergency preparedness management in AI/AN communities.39(pv)

Thus, the strategy of the IHS continues the long-standing attention to public health and the local community in the provision of health services for AI/AN persons.

Acknowledgments

Ronald Ferguson, Director, Division of Sanitation Facilities Construction, Indian Health Service, kindly provided data from the Indian Health Service. Fawn Yeh kindly assisted with the preparation of illustrations.

References

- 1. Cherokee Nation v. Georgia, 30 US 1 (1831).

- 2.Driver HE. Indians of North America. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press; 1969. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dobyns HE. Their Numbers Became Thinned. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Crosby AW. Virgin soil epidemics as a factor in the aboriginal depopulation in America. William Mary Q. 1976;33:289–299. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ravenel MP. The American Public Health Association—past, present, future. In: Ravenel MP, editor. A Half Century of Public Health. Lynn, MA: Nicholas Press; 1921. p. 13 ff. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wain H. A History of Preventive Medicine. Springfield, IL: Charles C Thomas; 1970. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mullan F. Plagues and Politics—The Story of the United States Public Health Service. New York, NY: Basic Books, Inc; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fenn EA. Pox Americana—The Great Smallpox Epidemic of 1775-82. New York, NY: Hill & Wang; 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bennett EF. Federal Indian Law. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office; 1958. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Rife JP, Dellapenna AJJ. Curing and Caring—A History of the Indian Health Service. Landover, MD: PHS Commissioned Officers Foundation for the Advancement of Public Health; 2009.

- 11.Pearson JD. Lewis Cass and the politics of disease: the Indian Vaccination Act of 1832. Wicazo Sa Review. 2003;18(2):9–35. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Treaty with the Choctaw Nation, Stat 210 Proclamation. October 18, 1820; Article VIII.

- 13. Treaty with the Winnebago Tribe, 7 Stat 370 Proclamation. February 13, 1833; Article V.

- 14. Treaty with the Rogue River Tribe, 10 Stat 1119 Proclamation. April 7, 1855; Article II.

- 15.Allen VR. Agency physicians to the Southern Plains Indians, 1868-1900. Bull Hist Med. 1975;49(3):318–330. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.US Office of Indian Affairs. Fifty-Eighth Annual Report of the Commissioner of Indian Affairs to the Secretary of the Interior 1889. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office; 1895. pp. 12–13. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Report of Agency Physician, KC Agency Physicians. August 1877. Box 1, File 3. Located at: Oklahoma Historical Society, Oklahoma City.

- 18.Grinnell F. Bromide of ammonium in whooping cough. Medical News (Phila.) 1882;40:294. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Indian Health Service. Compilation of Authorities, Treaties, Federal Statutes and Substantive Legislation. Rockville, MD: US Department of Health Education and Welfare, Indian Health Service, Division of Program Formulation; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Loe F. Sulfanilamide treatment of trachoma: preliminary report. J Am Med Assoc. 1938;111(15):1371–1372. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Snyder Act, HR 303, 42 stat 208 (November 2, 1921).

- 22.US Public Health Service. Contagious and Infectious Diseases Among the Indian. Washington, DC: US Public Health Service; 1913. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Annual Report of the Commissioner of Indian Affairs 1916. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office; 1916. pp. 4–5. [Google Scholar]

- 24.24. Institute for Government Research. The Problem of Indian Administration. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press; 1928. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mountin JW, Townsend JG. Observations on Indian Health Problems and Facilities. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office; 1936. Public Health Service Bulletin No. 223. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Adair J, Deuschle K, Barnett C. The People’s Health—Anthropology and Medicine in a Navajo Community (Revised and Expanded) Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Indian Health Transfer Act, Pub L No. 83–568, 68 stat 674 (1954).

- 28.Johnson E, Rhoades ER. The history and organization of Indian Health Services and Systems. In: Rhoades ER, editor. American Indian Health—Innovations in Health Care, Promotion and Policy. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press; 2000. p. 75. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Indian Sanitation Facilities Act, Pub L No. 86–121, 73 stat 267 (1959).

- 30.Indian Health Service. Public Law 86-121—July 31, 1959: 50th Anniversary. Rockville, MD: Office of Environmental Health and Engineering; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Todd JG. The Indian Health Service—a comprehensive health care program. J Environ Health. 1982;45(3):112–117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act, Pub L No. 93–638, 88 Stat. 2203. (1975).

- 33. Indian Health Care Improvement Act, Pub L No. 94-437, 90 Stat. 1400 (1976).

- 34.Indian Health Service. Fiscal Year 2013: Indian Health Service: Justification of Estimates for Appropriations Committees. Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rhoades ER, D’Angelo AJ, Hurlburt WB. The Indian Health Service record of achievement. Public Health Rep. 1987;102(4):356–360. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sequist TD, Cullen T, Acton KJ. Indian Health Service innovations have helped reduce health disparities affecting American Indian and Alaska Native people. Health Aff (Millwood) 2011;30(10):1965–1973. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rhoades ER, Hammond J, Welty TK, Handler AO, Amler RW. The Indian burden of illness and future health interventions. Public Health Rep. 1987;102(4):361–368. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Manson SM. New Directions in Prevention Among American Indian and Alaska Native Communities. Portland, OR: National Institute of Mental Health; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Indian Health Service. Strategic Plan 2006-2011. Rockville, MD: Office of Public Health Support, Division of Planning, Evaluation and Research; undated.