Significance

This work documents a previously unreported plant-wide signaling system based on the rapid, long-distance transmission of Ca2+ waves. In the root these waves move through the cortical and endodermal cell layers at speeds of up to 400 µm/s, i.e., traversing several cells per second. This Ca2+ wave system correlates with the triggering of molecular responses in distant parts of the plant upon perception of localized (salt) stress. Such propagating Ca2+ waves provide a new mechanism for the rapid integration of activities throughout the plant body.

Keywords: Ca2+ signaling, Yellow Cameleon, Two Pore Channel 1

Abstract

Their sessile lifestyle means that plants have to be exquisitely sensitive to their environment, integrating many signals to appropriate developmental and physiological responses. Stimuli ranging from wounding and pathogen attack to the distribution of water and nutrients in the soil are frequently presented in a localized manner but responses are often elicited throughout the plant. Such systemic signaling is thought to operate through the redistribution of a host of chemical regulators including peptides, RNAs, ions, metabolites, and hormones. However, there are hints of a much more rapid communication network that has been proposed to involve signals ranging from action and system potentials to reactive oxygen species. We now show that plants also possess a rapid stress signaling system based on Ca2+ waves that propagate through the plant at rates of up to ∼400 µm/s. In the case of local salt stress to the Arabidopsis thaliana root, Ca2+ wave propagation is channeled through the cortex and endodermal cell layers and this movement is dependent on the vacuolar ion channel TPC1. We also provide evidence that the Ca2+ wave/TPC1 system likely elicits systemic molecular responses in target organs and may contribute to whole-plant stress tolerance. These results suggest that, although plants do not have a nervous system, they do possess a sensory network that uses ion fluxes moving through defined cell types to rapidly transmit information between distant sites within the organism.

Plants are constantly tailoring their responses to current environmental conditions via a complex array of chemical regulators that integrate developmental and physiological programs across the plant body. Environmental stimuli are often highly localized in nature, but the subsequent plant response is often elicited throughout the entire organism. For example, soil is a highly heterogeneous environment and the root encounters stimuli that are presented in a patchy manner. Thus, factors including dry or waterlogged regions of the soil, variations in the osmotic environment, and stresses such as elevated levels of salt are all likely to be encountered locally by individual root tips, but the information may have to be acted on by the plant as a whole.

In animals, long-range signaling to integrate activities across the organism occurs through rapid ionic/membrane potential-driven signaling through the nervous system in addition to operating via long-distance chemical signaling. Plants have also been proposed to possess a rapid, systemic communication network, potentially mediated through signals ranging from changes in membrane potential/ion fluxes (1–3) and levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS) (4, 5) to altered hydraulics in the vasculature (6). Even so, the molecular mechanisms behind rapid, systemic signaling in plants and whether such signals indeed carry regulatory information remains largely unknown. Suggestions that Ca2+ channels play a role in signals that occlude sieve tube elements (7), or that mediate systemic electrical signaling (2) in response to remote wounding, highlight Ca2+-dependent signaling events as a strong candidate for mediating some of these long-range responses. Similarly, cooling of roots elicits Ca2+ increases in the shoot within minutes (8), suggesting systemic signals can elicit Ca2+-dependent responses at distal sites within the plant. However, despite extensive characterization of Ca2+ signals (reviewed in ref. 9), their roles in a possible plant-wide communication network remain poorly understood. Therefore, to visualize how Ca2+ might act in local and systemic signaling, we generated Arabidopsis plants expressing the highly sensitive, GFP-based, cytoplasmic Ca2+ sensor YCNano-65 (10). We observed that a range of abiotic stresses including H2O2, touch, NaCl, and cold shock triggered Ca2+ increases at the point of application. However, NaCl also elicited a Ca2+ increase that moved away from the point of stress application. Propagation of this Ca2+ increase was associated with subsequent systemic changes in gene expression. We also report that this salt stress-induced long-distance Ca2+ wave is dependent on the activity of the ion channel protein Two Pore Channel 1 (TPC1), which also appears to contribute to whole-plant stress tolerance.

Results

Changes in Cytoplasmic Ca2+ Occur in Response to Abiotic Stress.

Arabidopsis seedlings were grown in a thin layer of gel and a ∼500 µm × 500 µm region of the gel covering the root apex was removed to allow localized application of treatments to the root tip (Materials and Methods). Consistent with previous studies (reviewed in ref. 9), when a range of abiotic stresses including touch, cold, ROS (H2O2), and NaCl were locally applied to the root tip, we detected rapid and transient Ca2+ increases at the site of treatment that showed stimulus-specific spatial/temporal characteristics (Fig. S1 and Movies S1–S4). However, we observed that, among these treatments, NaCl treatment also led to a propagating Ca2+ increase moving away from the point of stress application (Figs. 1 and 2 and Movie S5). Treatment with 200 mM sorbitol (osmotic control for the 100 mM NaCl stress) did not elicit Ca2+ changes under these conditions (Fig. S1E), suggesting such Ca2+ changes were being specifically elicited by the salt stress.

Fig. 1.

Systemic Ca2+ signal in roots in response to local salt stress. (A) Propagation of Ca2+ increase through cortical/endodermal cells of the primary root monitored 5,000 µm shootward of the root tip site of application of 100 mM NaCl. Representative of n = 18. cor, cortex; en, endodermis; ep, epidermis; va, vasculature. (B) Ca2+ wave emanating from lateral root upon application of 100 mM salt stress to the lateral root tip. Time represents seconds after NaCl treatment. (Scale bars: 100 µm.)

Fig. 2.

Wave-like propagation of Ca2+ increase through the root. (A) Time to significant increase in FRET/CFP signal (Ca2+ increase) monitored at 0–5,000 µm from the site of local application of 100 mM NaCl to the root tip of WT (n = 23) and tpc1-2 (n = 16). Significant increase was defined as the timing where ratio values increased to >2 SD above the mean of pretreatment values. Results are mean ± SD of n > 5 (dashed line). Solid line, linear regression, R2 > 0.99 for all genotypes. (B) Cortical and endodermal localization of Ca2+ increase monitored 1,000 µm from site of local NaCl application to root tip in both the genotypes in A. Representative of n > 5. (C) Ca2+ wave dynamics monitored shootward of the salt-stimulated root tip of WT and tpc1-2 mutants. Ratiometric data of the YCNano-65 Ca2+-dependent FRET/CFP signal was extracted from sequential regions of interest (4 µm × 51.2 µm covering the cortex and endodermis) along the root at 1,000 µm from the local application of 100 mM NaCl. Analysis was repeated on images taken every 0.5 s (WT) and 4 s (tpc1-2) and data from five roots averaged and pseudocolor coded. ROI, region of interest.

Salt Stress Induces a Long-Distance Systemic Wave of Increased Ca2+.

Local application of salt stress to the root tip induced an increase in Ca2+ that propagated shootward from the site of NaCl stimulation (Figs. 1 and 2). This salt stress-induced elevation in Ca2+ was largely constrained to the cortical and endodermal cell layers (Fig. 1 A and B). Thus, changes were not seen in the epidermal cells even though this tissue is known to generate stimulus-evoked Ca2+ elevations (e.g., ref. 11). In addition, when a lateral root tip was stimulated, a Ca2+ wave also moved through the cortex/endodermis, traveling to the main root and then bidirectionally rootward and shootward (Fig. 1B and Movie S6). This Ca2+ increase eventually traversed to the aerial part of the plant, moving through the hypocotyl (Fig. S2 and Movie S7). Quantitative analysis of the timing of Ca2+ increase in various regions along the root (Fig. 2A) coupled with kymograph-based measurements of rates of Ca2+ increase (Fig. 2C) indicated that the wave front of these Ca2+ changes moved at a steady 395.7 ± 27.8 µm/s (±SD) (Fig. 2 A and C), taking ∼1 min to traverse the entire length of the root system and ∼2 min to spread across the entire length of the Arabidopsis seedlings used in this study.

Root Tip Salt Stress Triggers Systemic Molecular Responses in Shoot Tissue.

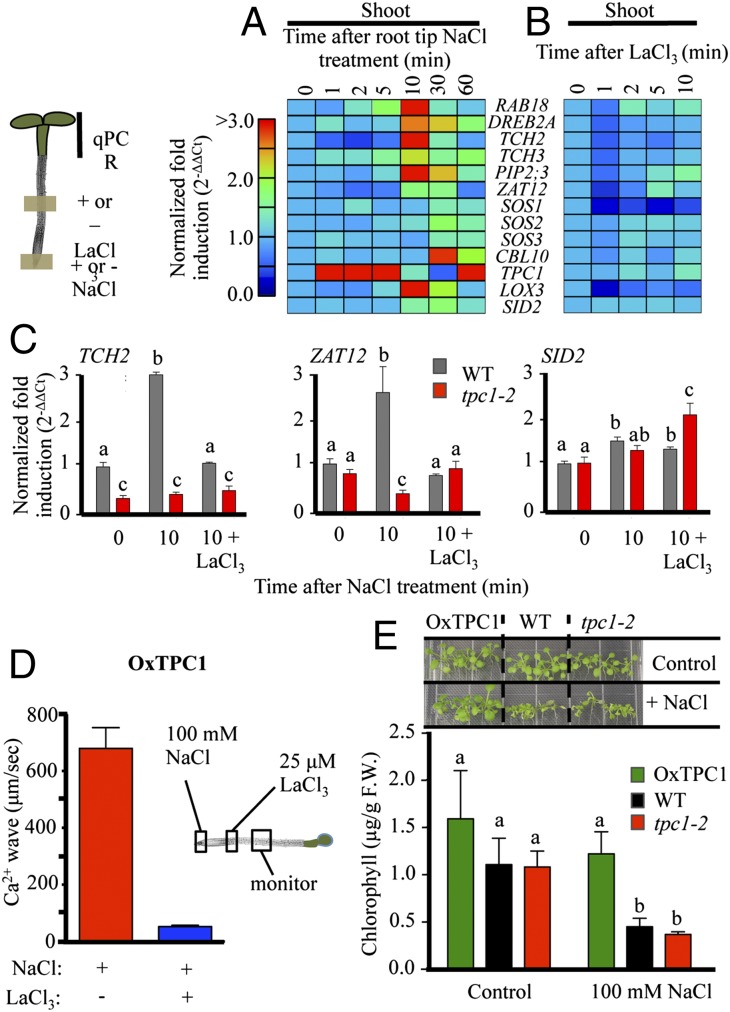

We next used a battery of molecular markers (Table 1) and quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) analysis to ask whether the long-distance Ca2+ increase we observed in response to this root-applied NaCl stress was accompanied by a systemic shoot response (Fig. 3A). As expected, increased transcript levels of stress-related genes such as RAB18, DREB2A, TCH2, and ZAT12, and the salt stress response genes SOS1 and CBL10 (12) were detectable in the directly salt-stressed root tissues within 1–2 min of treatment (Fig. 3 and Fig. S3A). These rapidly induced genes showed subsequent oscillations in levels, sharing a fall at 10 min and subsequent increase over the 60 min of analysis (Fig. S3A). However, local salt treatment of the root tip also led to an increase in transcript abundance of a number of stress markers in the distant aerial parts of the plant. For example, by 10 min RAB18, DREB2A, TCH2, TCH3, PIP2;3, ZAT12, LOX3, and SID2 levels were significantly increased in the shoot (P < 0.05, t test; Fig. 3A and Fig. S3B). These genes generally showed a peak in transcript level at 10 min that had begun to fall by 30–60 min. Induction of markers such as SOS1, SOS2/CIPK4, SOS3/CBL4, and CBL10 was significant only after 30 min. The vacuolar channel TPC1 was notable in showing a rapid, transient transcript accumulation within 1 min in the shoot (Fig. S3C). In contrast, NaCl treatment led to an equally rapid but sustained decrease in TPC1 transcript levels in the salt-stressed roots.

Table 1.

qPCR markers for abiotic stress used in this study

| Gene | Stress/signal/role |

| RAB18 | ABA (38) |

| DREB2A | Drought/cold (39) |

| TCH2, TCH3 | Mechanical (40, 41) |

| PIP2;3 | Water stress (42) |

| Zat12 | ROS (5) |

| SOS1, SOS2(CIPK24), SOS3 (CBL4), CBL10 | Salt (43–45) |

| TPC1 | Ion transport (14, 18) |

| LOX3 | JA/wounding (46) |

| SID2 | Salicylate (47) |

JA, jasmonate.

Fig. 3.

Gene expression changes and seedling survival in response to root tip salt stress. (A) qPCR analysis of transcript abundance in systemic shoots responding to 100 mM NaCl application to the root tip. (B) Local application of 25 µM LaCl3 does not itself elicit large shoot transcriptional changes. (C) Induction of TCH2 and ZAT12 (but not SID2) in shoots in response to root tip-applied NaCl is blocked by 25 µM LaCl3 locally applied between root and shoot, and is disrupted in tpc1-2. Mean ± SEM; n > 4 from three separate experiments. Each gene is normalized to its own 0-min value. (D) Systemic transmission rate of Ca2+ waves in OxTPC1 and effect of La3+ treatment on blocking on Ca2+ wave propagation rate (±SEM; n ≥ 6 independent experiments). Rates were calculated as in Fig. 2A. (E) Effect of salt stress in WT, tpc1-2, and TPC1 overexpression (OxTPC1) seedlings. Ten-day-old seedlings were transplanted to 100 mM NaCl plates and grown for an additional 7 d. Representative of three independent experiments. Chlorophyll content was monitored as an index of plant vitality. Results represent mean ± SEM; n = 3 independent experiments. “a,” “b,” and “c” denote significance (P < 0.05, t test). Bars sharing the same letter are not significantly different.

Direct salt movement, either within the growth medium or within the plant, was too slow to explain the induction of such systemic responses in the aerial plant parts. Thus, fluorescein (a small molecule dye) took >2 min to diffuse only 300 µm through the matrix of the growth medium (Fig. S4 A and B), and there was no detectable increase in Na content of shoots, measured via inductively coupled plasma (ICP) analysis, after >10 min of local root NaCl treatment (Fig. S4C). Therefore, the propagation of the Ca2+ wave and induction of systemic molecular responses are unlikely to reflect direct response to salt that had moved from the site of application either through the gel or within the plant.

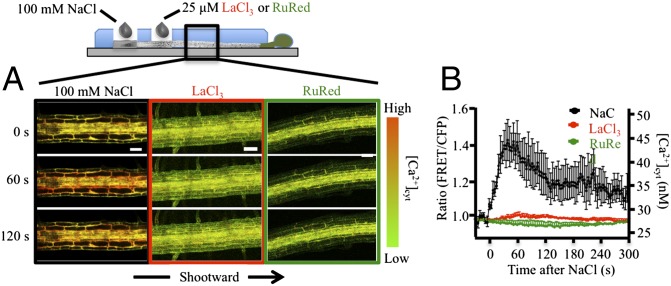

To test whether the transcriptional changes elicited by local salt stress of the root required the Ca2+ wave, we asked whether pharmacological inhibitors that blocked transmission of the Ca2+ wave also blocked distal transcriptional responses. Local application of LaCl3 (putative plasma-membrane Ca2+-channel blocker) or Ruthenium Red (RuRed) (putatively targeting internal Ca2+ release) between the sites of stress application and Ca2+ signal detection (Fig. 4A) inhibited transmission of the Ca2+ signal past this point (Fig. 4). However, if the NaCl stress was applied shootward of the LaCl3 treatment, the propagation of the Ca2+ wave still moved shootward at 397.5 ± 42.1 μm/s (±SEM) (P < 0.05, t test) from the point of NaCl application (Fig. S5). This result indicates that the position of the LaCl3, rather than simply its presence in the root system, appeared to be a key factor in blocking the progression of the Ca2+ wave.

Fig. 4.

Effect of Ca2+ channel blockers on salt-induced Ca2+ waves. (A) Propagation of NaCl-induced Ca2+ waves in roots with and without 3.5-min pretreatment with 25 µM LaCl3 or RuRed. (Scale bars: 100 µm.) (B) Quantitative analysis of time course of Ca2+ changes in response to local 100 mM NaCl treatment with and without 25 µM LaCl3 or RuRed (B). Results represent mean ± SEM of n ≥ 4 (RuRed and LaCl3) or n = 17 (WT) monitored 1,000 µm from the site of root tip NaCl application.

The increase in transcript abundance of genes such as TCH2 and ZAT12 (Fig. 3C) or TCH3, PIP2;3, LOX3, and TPC1 (Fig. S6) seen at 10 min in the shoot in response to root tip NaCl stress was suppressed by the local LaCl3 treatment applied shootward of the site of NaCl application. In contrast, induction of RAB18 and DREB2A (Fig. S6) or SDI2 (Fig. 3C) was left unaffected. These observations are consistent with a requirement for the Ca2+ wave in the triggering of at least part of the systemic molecular regulation seen in response to local root salt stress.

The effect of La3+ application on its own is an important control for these experiments. Although we observed that LaCl3 alone could alter transcript levels of some genes (Fig. 3B and Fig. S7), this treatment did not significantly affect the levels of the molecular markers at the 10-min time point used for these experiments (Fig. 3B and Fig. S7). A prolonged suppression of LOX3 and SOS1 transcript levels were a notable exception, and so responses of these markers in La3+ inhibitor experiments must be made with caution (Fig. S7).

Long-Distance Ca2+ Signaling Is Dependent on the Vacuolar TWO PORE CHANNEL 1.

In animals, Ca2+ waves are often supported by processes involving calcium-induced calcium release (CICR) (13). The slow vacuolar (SV) channel is a large-conductance, voltage-dependent ion channel (reviewed in ref. 14) that is permeable to Ca2+ (15) and has been proposed to mediate plant CICR (15–17), although this idea remains controversial (14). The Arabidopsis SV channel is encoded by a single gene, TWO PORE CHANNEL 1 (TPC1) (18). In Arabidopsis, loss-of-function mutants of TPC1 show disrupted stomatal signaling and abscisic acid (ABA) regulation of germination (18) and the gain-of-function fou2 mutant exhibits developmental effects thought to be linked to aberrant defense signaling (19). We therefore tested the hypothesis that the SV channel might play a role in sustaining the salt-induced Ca2+ wave using tpc1 mutants. Previous work measuring Ca2+ changes in a TPC1 knockout expressing the luminescent Ca2+ indicator aequorin indicated no clear disruption of a range of stress-induced Ca2+ changes (20). Consistent with this report, we found that salt stress-induced Ca2+ elevations were not grossly altered in tpc1-2 (a protein null) (18) when monitored at the direct site of stress application, although they did exhibit a slightly delayed onset (Fig. S1 D and E, and Movie S8). However, the speed of transmission of the Ca2+ wave in tpc1-2 was significantly reduced to 15.5 ± 1.9 µm/s (±SD) (P < 0.05, t test; Fig. 2).

TWO PORE CHANNEL 1 Mutants Affect Transcript Levels of Stress-Related Genes.

qPCR analysis of our panel of stress markers showed that, in response to root tip NaCl treatment, shoot induction of genes such as TCH2 and ZAT12 was significantly attenuated in the tpc1-2 mutant (Fig. 3C and Fig. S8), a pattern confirmed in the knockdown lines tpc1-1 (36% reduction in TPC1 transcript; Fig. S8) and tpc1-4 (21% reduction in TPC1 transcript; Fig. S8). Interestingly, La3+ treatment had a complex interaction with NaCl induction of TCH2 in these backgrounds, leading to a partial recovery of transcript levels. This observation suggests that feedback between vacuolar and plasma membrane Ca2+ fluxes is likely an important element in the transcriptional response of at least TCH2 to salt stress.

qPCR analysis also indicated that TPC1 is the most rapidly systemically up-regulated gene we tested, with 10-fold increase in transcript abundance in the shoot within 1–2 min of root salt stress (P < 0.05, t test; Fig. 3A and Fig. S3C). This observation raises the possibility of a self-reinforcing signaling system with Ca2+ wave-related rapid induction of TPC1 amplifying and extending subsequent Ca2+ responses. Consistent with such ideas, markers that were suppressed in tpc1 mutants such as ZAT12 and TCH2 (Fig. 3C and Fig. S8) were constitutively increased above WT in a TPC1 overexpression line (Fig. S9A). This up-regulation of transcript levels was suppressed by La3+ treatment (Fig. S9B), suggesting altered control of Ca2+ homeostasis may link TPC1 levels to transcriptional regulation. Consistent with these ideas, the speed of propagation of the Ca2+ wave in the TPC1 overexpression line was 679 ± 73 µm/s, 1.7-fold faster than WT but was still sensitive to inhibition by LaCl3 (Fig. 3D).

TWO PORE CHANNEL 1 Expression Level Affects Whole-Plant Salt Sensitivity.

The overexpression line TPC1 10.21 (18), which showed 73- to 130-fold increase in transcript level (Fig. S9C), was more resistant to NaCl stress based on seedling growth and chlorophyll levels after growth on 100 mM NaCl for 7 d (Fig. 3E). Thus, the up-regulation of systemic molecular changes and faster Ca2+ wave signaling observed in the TPC1 transgenic lines correlate with alterations in whole-plant salt stress resistance.

Discussion

In plants, environmental stimuli including wounding or heat stress have been proposed to elicit long-distance signaling involving mechanisms such as plasma membrane depolarization and self-propagating increases of ROS (1–5, 21, 22). Our results suggest Ca2+-dependent signaling also plays a role in this process of systemic signaling in response to salt stress. Thus, local salt stress of the root tip leads to the spreading of a Ca2+ wave that propagates preferentially through cortical and endodermal cells to distal shoot tissues (Figs. 1 and 2). This Ca2+ wave moves with a velocity of ∼400 µm/s (Fig. 2A), i.e., traversing several cells per second. Local treatment with LaCl3 that blocked the transmission of the Ca2+ wave (Fig. 4) also inhibited subsequent systemic molecular responses (Fig. 3C and Fig. S6). Thus, these patterns of transmission and response are consistent with a model in which the rapidly propagating Ca2+ wave serves as a long-distance signal that triggers systemic responses to local salt stress of the root system. It is important to note that such La3+ treatment itself could inhibit transcription of some genes (Fig. S7). This observation implies that a basal level of La3+-sensitive (likely Ca2+-dependent) signaling between root and shoot may be required to sustain nonstimulated levels of some genes. In addition, although such blocking of the Ca2+ wave could inhibit systemic induction of stress markers such as TCH2, ZAT12 (Fig. 3C), TCH3, and PIP2;3 (Fig. S6) in response to localized salt stress treatment, a similar treatment could not block up-regulation of RAB18 and DREB2A (Fig. S6). These observations suggest additional systemic signals are likely operating in parallel to the Ca2+ wave.

Role of the Vacuolar Ion Channel TPC1 in Propagation of the Ca2+ Wave.

We found that the rate of propagation of the systemic Ca2+ wave was reduced from 395.7 ± 27.8 µm/s in WT to 15.5 ± 1.9 µm/s in the loss-of-function tpc1-2 mutant (Fig. 2), representing a ∼25-fold reduction in speed. TPC1 encodes the vacuolar SV ion channel that is sensitive to cytosolic Ca2+ levels and to those in the lumen of the vacuole (23), suggesting feedback regulation of this channel by alterations in cytosolic and vacuolar Ca2+ levels could play a role in Ca2+ wave propagation. However, it remains unclear whether TPC1 acts itself as a vacuolar Ca2+ release channel that sustains the Ca2+ wave (14). Thus, TPC1 could be operating more indirectly, through, e.g., altering tonoplast potential and so gating an independent vacuolar Ca2+ conductance. However, effects of tpc1 mutants on both reducing Ca2+ changes and inhibiting the induction of systemic molecular responses such as increase in TCH2 and ZAT12 transcript abundance (Fig. 3C and Fig. S8) are very similar to those of blocking Ca2+ changes with La3+. These observations are consistent with TPC1 actively maintaining the propagation of the Ca2+ wave through an effect on Ca2+ fluxes. In support of these ideas, the TPC1 overexpression line showed Ca2+ wave propagation rates that were 1.7-fold faster than WT (Fig. 3D). The overexpression line also exhibited constitutive elevation of marker genes such as TCH2 and ZAT12 that appear normally dependent for up-regulation on the Ca2+ wave elicited by local salt stress. This constitutive induction was inhibited by the channel blocker La3+ (Fig. S9B), suggesting a link between transcriptional changes modulated by TPC1 and Ca2+-mediated events. Taken together, these results support a model in which local NaCl stress elicits a long-distance Ca2+ wave-mediated signaling system that triggers systemic molecular responses. Furthermore, comparison of WT, tpc1-2, and plants overexpressing TPC1 grown on 100 mM NaCl-containing plates indicated that, by 7 d, the overexpression line was significantly more resistant to this level of salt stress as inferred from plant size and chlorophyll content (Fig. 3E). These observations suggest that the Ca2+ wave system mediated by TPC1 may also be contributing to the whole-plant resistance to salt stress. However, it is important to note that, due to the extended time of salt stress needed to elicit this visible phenotype, the link between Ca2+ wave signaling and this whole-plant physiological response must remain tentative.

qPCR analysis (Fig. 3A and Fig. S3C) indicated that TPC1 was the most rapidly up-regulated gene we tested in the shoot, showing up to 10-fold increase in transcript abundance within 1–2 min of root salt stress. We also observed rapid changes in transcript abundance for some other genes in qPCR analyses, such as rapid down-regulation of TCH2 (Fig. S3). The timescale of these alterations suggest either extremely fast changes in transcription or rapid alterations in mRNA stability/turnover elicited by the salt stress signal.

In addition to such rapid alterations in transcript level, posttranscriptional regulation is also likely playing a role in modulating the extent of Ca2+ wave propagation through TPC1. This idea is because this channel is ubiquitously expressed across tissue types, yet the root Ca2+ wave is restricted to the cortex and endodermal cell layers (Fig. 1). Although it remains to be discovered whether the action of TPC1 and transmission of the Ca2+ wave is related to other proposed systemic signaling systems such as membrane depolarization (2) or ROS-dependent events (5), TPC1 has been proposed to be posttranslationally regulated by ROS (24). This observation raises the possibility of a point of interaction between the ROS and Ca2+-dependent systemic signaling systems. Transmission of systemic ROS responses is thought to be Ca2+-independent (5), suggesting a model where Ca2+ changes could lie downstream of ROS. However, the relationship between ROS and Ca2+ is complex with Ca2+ triggering ROS production (25) and ROS eliciting Ca2+ increases (25, 26). Thus, the relationship of TPC1, Ca2+ wave, and ROS is an important area for future study.

TPC1 is found in all land plants (14) and the function of this channel appears to be conserved at least between monocots to dicots (27). This ubiquity of TPC1 suggests a possibly widespread and general function of this channel in plant biology, hinting at the potentially widespread nature of Ca2+ wave signaling in plants.

Materials and Methods

Plant Growth and Transformation.

Seeds of Arabidopsis thaliana ecotype Columbia 0 and the mutants used in this study (tpc1-1, tpc1-2, tpc1-4, OxTPC1/TPC1 10.21) were surface sterilized and germinated on half-strength Epstein’s medium containing 10 mM sucrose and 0.5% (wt/vol) phytagel (Sigma-Aldrich), pH 5.7, as described previously (28). Plants were grown under a long-day (LD) cycle of 16 h light/8 h dark at 22 °C. Ten-day-old seedlings were transplanted to SunshineRedi-earth soil (Sun Gro Horticulture) and were grown under cool white fluorescent lights (75–88 µE⋅m−2⋅s−1) at 22 °C under the LD light cycle. Plant transformation was carried out essentially as in ref. 29 using midlogarithmic cultures (A600 = 0.6) of Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain GV3101 harboring the binary vector YCNano-65/pEarleyGage100 that encoded YCNano-65 (see below for details of this vector), resuspended in half strength Epstein’s medium containing 5% (wt/vol) sucrose and 0.05% (vol/vol) Silwet-L77 (Lehle Seeds). Transformed plants were covered with a clear plastic cover overnight. A second transformation on the same plants was carried out 1 wk later. Plants were then grown under LD conditions until seed set and harvest. Selection of transformants expressing YCNano-65 was made using an epifluorescence dissecting microscope (Nikon SMZ1500 Stereoscope) using a GFP filter set (excitation, 450–490 nm; dichroic mirror, 495 nm; emission, 500–550 nm). Multiple independent lines were selected, selfed, and the T2 or greater generation used for subsequent imaging. All results were confirmed on multiple independent lines. All YCNano-65–expressing lines used showed equivalent growth and development to their untransformed counterparts. tpc1-1, tpc1-2, tpc1-4, and OxTPC1 were kindly provided by Edgar Peiter (Martin-Luther-Universität Halle-Wittenberg, Halle, Germany) and Dale Sanders (John Innes Centre, Norwich, UK).

Abiotic Stress and Inhibitor Treatment.

Arabidopsis seedlings expressing the YCNano-65 FRET sensor were grown on a thin layer of gel (∼2 mm thick) containing half-strength Epstein’s medium supplemented with 0.5% (wt/vol) phytagel (Sigma-Aldrich) and 10 mM sucrose, under LD conditions at 22 °C for 6 d. A small window (∼500 µm × 500 µm) was removed from the gel at the tip of the root to expose the apical ∼50 µm of the root to allow precise application of 100 mM NaCl (salt stress), 100 µM H2O2 (ROS stress), chilled medium at 4 °C (cold stress), or 200 mM d-sorbitol (control equivalent to the osmotic stress from 100 mM NaCl). Touch stress was applied using contact with a glass micropipette as previously described (30). For inhibitor treatments, a small window (∼500 µm × 500 µm) was also made in the gel in the middle region of the root, shootward of the root tip window. Ten microliters of 25 µM LaCl3 (putative plasma membrane channel blocker) or RuRed (putative antagonist of internal sites of Ca2+ release) were added either in the root tip gel window or to the middle gel window (see diagram in Fig. 4A) 30 min before salt treatment of the root tip as indicated for each experiment. Arabidopsis seedlings pretreated with pharmaceutical inhibitors were kept in a humid Petri dish until confocal imaging.

Confocal Image Analysis of in Vivo Ca2+ Changes.

Stable transgenic lines expressing YCNano-65 under the control of CaMV35S promoter were grown under sterile conditions in a thin layer (∼2 mm) of half-strength Epstein’s medium containing 0.5% (wt/vol) phytagel and 10 mM sucrose on a no. 1.5 cover glass (24 × 50 mm; Fisher Scientific) for 6 d under LD conditions at 22 °C. Ratio confocal imaging of Ca2+ changes was then performed with an LSM510 Meta laser-scanning confocal microscope (Carl Zeiss) using a Plan-Neofluar 10×/0.3 or 20×/0.75 Plan-Apochromat objective as described previously (31). The YCNano-65 Ca2+ sensor was excited with the 458-nm line of an argon laser and CFP (462–505 nm) and cpVenus (FRET, 526–537 nm) emission detected using a 458-nm primary dichroic mirror and the microscope system’s Meta detector. Ca2+ levels were determined from the ratio of the Ca2+-dependent FRET signal to the CFP signal normalized to the FRET-to-CFP ratio from before stress treatment. Quantitative analysis of Ca2+ dynamics (from the ratiometric Ca2+-FRET signal) was performed using iVision-Mac (version 4.0.16) image-processing software (BioVision Technologies) with a custom script for the calculation of the ratiometric FRET signal from region of interests (ROIs). Briefly, quantitative analysis of YCNano-65 data (e.g., Fig. 2) was calculated from the ROIs (4 µm long × 51.2 µm wide, with 1,280 pixels of data) scanned along the root, generating 116 sequential data points covering a total of 464 µm of root length per image. The extracted quantitative ratio numerical data from the sequential confocal images were displayed as a pseudocolor-coded matrix using MultiExperiment Viewer MeV software (version 10.2; ref. 32).

Ratio values were converted to absolute [Ca2+]cyt (in nanomolar concentration) using the equation  (33), where R is the experimentally monitored FRET/CFP ratio, n is the Hill coefficient (1.6), and the Kd for Ca2+ is 64.8 nM (10). The ratio from Ca2+-saturated reporter (Rmax, 5.33 ± 1.43) was determined by incubating samples with 50% (vol/vol) ethanol and the minimum ratio (Rmin, 0.40 ± 0.04) by incubation with 10 mM EGTA according to ref. 31. The values derived from this in vivo calibration should be taken as approximations due to difficulties inherent in obtaining a robust Rmax and Rmin value and uncertainty in the precise Kd of YCNano-65 in the plant cytoplasmic environment.

(33), where R is the experimentally monitored FRET/CFP ratio, n is the Hill coefficient (1.6), and the Kd for Ca2+ is 64.8 nM (10). The ratio from Ca2+-saturated reporter (Rmax, 5.33 ± 1.43) was determined by incubating samples with 50% (vol/vol) ethanol and the minimum ratio (Rmin, 0.40 ± 0.04) by incubation with 10 mM EGTA according to ref. 31. The values derived from this in vivo calibration should be taken as approximations due to difficulties inherent in obtaining a robust Rmax and Rmin value and uncertainty in the precise Kd of YCNano-65 in the plant cytoplasmic environment.

Monitoring Diffusion Through the Gel.

To test for the rate of small-molecule diffusion through the growth medium gel, 50 µM fluorescein was added to a window at the tip of the root as for NaCl local treatment. Fluorescein movement was then monitored with the LSM510 using a 20×/0.75 Plan-Apochromat objective. Fluorescein signal was excited with the 488-nm line of the argon laser and emission collected using an HFT 488/543/633 dichroic beam splitter and 500- to 530-nm emission filter. Images were acquired every 4 s for 270 s.

Cloning of the YCNano-65 FRET Sensor.

For the 35S:YCNano-65 Ca2+ FRET sensor construct, the YCNano-65 FRET cassette fragment from YCNano-65/pcDNA3.1 plasmid (a kind gift from Takeharu Nagai, Osaka University, Osaka) (10) was isolated by digesting with EcoRI and cloned into the EcoRI site of the pENTR11 gateway entry vector (Invitrogen). The resulting YCNano-65/pENTR11 construct was introduced into the plant binary vector pEarleyGate100 (34) by Gateway cloning using LR Clonase II (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. pEarlyGate 100 has a CaMV35S promoter to drive constitutive expression in plant. The resulting YCNano-65/pEarleyGate100 construct was verified by HindIII endonuclease digestion patterns and DNA sequencing and transformed into Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain GV3101 using electroporation.

Salt Treatment, Total RNA Isolation, and qPCR Analysis.

For qPCR analysis, the root tip region of 10-d-old seedlings of WT Col_0, tpc1-1, tpc1-2, tpc1-4, OxTPC1 was covered with an ∼5-mm strip of KimWipe wetted with growth medium and acclimated for at least 1 h. Approximately 20 µL of medium with or without 100 mM NaCl or 25 µM LaCl3 was then added to the KimWipe strip to achieve precise local application as described for each experiment. For the LaCl3 blockade experiments described for Fig. 3, the 25 µM LaCl3 was added to a similar KimWipe strip covering the midregion of the root 30 min before salt stress was applied at the root tip. Root and shoot samples were harvested and stored at −80 °C. Total RNA was then isolated from tissue samples (50–200 mg) using the RNeasy Plant Mini Kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Residual genomic DNA was removed by RNase-free DNase I treatment using the TURBO DNase kit (Ambion) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Total RNA (1–2 µg) was reverse transcribed into first-strand cDNA in a 40-µL reaction (25–50 ng of total RNA per µL) with the SuperScriptIII first-strand synthesis system for reverse transcription-PCR (Invitrogen). qPCR analysis was performed using a Stratagene Mx3000P QPCR System, and analysis was performed with the MxPro qPCR software (Stratagene). The Arabidopsis UBQ10 gene was used as an internal reference for standardization as described previously (35). cDNA proportional to 10 ng of starting total RNA was combined with 200 nM of each primer and 7.5 µL of 2× EvaGreen qPCR master mixed with ROX passive reference dye (Biotium) in a final volume of 15 µL. qPCRs were performed in a 96-well optical PCR plate (ABgene) using the following parameters: 1 cycle of 15 min at 95 °C, and 40 cycles of 20 s at 95 °C, 15 s at 58 °C, and 15 s at 65 °C, and 1 cycle of dissociation from 58 to 95 °C with 0.5° increments. Quantitation of expression of the marker genes was calculated using the comparative threshold cycle (Ct) method as described previously (36). The qPCR primers used are described in Table S1.

Quantification of Sodium Accumulation.

Plants were treated with 100 mM NaCl applied to the root tip as described above and then dissected into root and shoot tissue (∼50 mg). The root tissues were rinsed in deionized water to remove contaminating NaCl from the medium, and then each sample (root and shoot) was digested in 0.6 mL of nitric acid in a glass test tube at 120 °C for 2 h followed by further digestion in 0.4 mL of 60% (vol/vol) HClO4 at 150–180 °C for an additional 2 h or until total sample volume became ≤0.5 mL. The resulting tissue samples were cooled to room temperature and diluted in 5 mL of Nanopure water, and sodium concentration was determined using a Perkin-Elmer Optima 2000DV inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectrometer (ICP-OES) according to the manufacturer’s instruction. Results of Na level in parts per million (in milligrams per liter) was calculated and converted to milligrams per kilogram fresh weight (F.W) using the following equation:

Chlorophyll Content Assay.

Aerial parts of these seedlings (30–100 mg F.W) were harvested for chlorophyll determination as described previously (37) with slight modification. Briefly, tissue samples in 0.5 mL of 80% (vol/vol) acetone were homogenized using a GENO/GRINDER 2000 (SPEX SamplePrep, LLC) at 1,200 strokes per min for 10 min. The resulting lysates were centrifuged at 4 °C, 1,690 × g for 15 min. The clear supernatant was collected, and chlorophyll content was determined by measuring the absorbance at 652 nm and applying the following equation:

|

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank S. Swanson and H. Maeda for critical reading of the manuscript and R. McClain for ICP-OES access. This work was supported by National Science Foundation Grants NSF IOS-11213800 and MCB-1329723, and National Aeronautics and Space Administration Grants NNX09AK80G and NNX12AK79G. Imaging was performed at the Newcomb Imaging Center, University of Wisconsin–Madison.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission. D.S. is a guest editor invited by the Editorial Board.

See Commentary on page 6126.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1319955111/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Felle HH, Zimmermann MR. Systemic signalling in barley through action potentials. Planta. 2007;226(1):203–214. doi: 10.1007/s00425-006-0458-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mousavi SA, Chauvin A, Pascaud F, Kellenberger S, Farmer EE. GLUTAMATE RECEPTOR-LIKE genes mediate leaf-to-leaf wound signalling. Nature. 2013;500(7463):422–426. doi: 10.1038/nature12478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zimmermann MR, Maischak H, Mithöfer A, Boland W, Felle HH. System potentials, a novel electrical long-distance apoplastic signal in plants, induced by wounding. Plant Physiol. 2009;149(3):1593–1600. doi: 10.1104/pp.108.133884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Capone R, Tiwari BS, Levine A. Rapid transmission of oxidative and nitrosative stress signals from roots to shoots in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2004;42(5):425–428. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2004.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Miller G, et al. The plant NADPH oxidase RBOHD mediates rapid systemic signaling in response to diverse stimuli. Sci Signal. 2009;2(84):ra45. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2000448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Christmann A, Weiler EW, Steudle E, Grill E. A hydraulic signal in root-to-shoot signalling of water shortage. Plant J. 2007;52(1):167–174. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2007.03234.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Furch AC, et al. Sieve element Ca2+ channels as relay stations between remote stimuli and sieve tube occlusion in Vicia faba. Plant Cell. 2009;21(7):2118–2132. doi: 10.1105/tpc.108.063107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Campbell AK, Trewavas AJ, Knight MR. Calcium imaging shows differential sensitivity to cooling and communication in luminous transgenic plants. Cell Calcium. 1996;19(3):211–218. doi: 10.1016/s0143-4160(96)90022-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McAinsh MR, Pittman JK. Shaping the calcium signature. New Phytol. 2009;181(2):275–294. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2008.02682.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Horikawa K, et al. Spontaneous network activity visualized by ultrasensitive Ca2+ indicators, yellow Cameleon-Nano. Nat Methods. 2010;7(9):729–732. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Monshausen GB, Miller ND, Murphy AS, Gilroy S. Dynamics of auxin-dependent Ca2+ and pH signaling in root growth revealed by integrating high-resolution imaging with automated computer vision-based analysis. Plant J. 2011;65(2):309–318. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2010.04423.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Munns R, Tester M. Mechanisms of salinity tolerance. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2008;59:651–681. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.59.032607.092911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jaffe LF. Fast calcium waves. Cell Calcium. 2010;48(2-3):102–113. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2010.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hedrich R, Marten I. TPC1-SV channels gain shape. Mol Plant. 2011;4(3):428–441. doi: 10.1093/mp/ssr017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ward JM, Schroeder JI. Calcium-activated K+ channels and calcium-induced calcium release by slow vacuolar ion channels in guard cell vacuoles implicated in the control of stomatal closure. Plant Cell. 1994;6(5):669–683. doi: 10.1105/tpc.6.5.669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bewell MA, Maathuis FJ, Allen GJ, Sanders D. Calcium-induced calcium release mediated by a voltage-activated cation channel in vacuolar vesicles from red beet. FEBS Lett. 1999;458(1):41–44. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)01109-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang YJ, et al. Functional analysis of a putative Ca2+ channel gene TaTPC1 from wheat. J Exp Bot. 2005;56(422):3051–3060. doi: 10.1093/jxb/eri302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Peiter E, et al. The vacuolar Ca2+-activated channel TPC1 regulates germination and stomatal movement. Nature. 2005;434(7031):404–408. doi: 10.1038/nature03381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bonaventure G, et al. A gain-of-function allele of TPC1 activates oxylipin biogenesis after leaf wounding in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2007;49(5):889–898. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2006.03002.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ranf S, et al. Loss of the vacuolar cation channel, AtTPC1, does not impair Ca2+ signals induced by abiotic and biotic stresses. Plant J. 2008;53(2):287–299. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2007.03342.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jia W, Zhang J. Stomatal movements and long-distance signaling in plants. Plant Signal Behav. 2008;3(10):772–777. doi: 10.4161/psb.3.10.6294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Suzuki N, et al. Temporal-spatial interaction between reactive oxygen species and abscisic acid regulates rapid systemic acclimation in plants. Plant Cell. 2013;25(9):3553–3569. doi: 10.1105/tpc.113.114595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dadacz-Narloch B, et al. A novel calcium binding site in the slow vacuolar cation channel TPC1 senses luminal calcium levels. Plant Cell. 2011;23(7):2696–2707. doi: 10.1105/tpc.111.086751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pottosin I, Wherrett T, Shabala S. SV channels dominate the vacuolar Ca2+ release during intracellular signaling. FEBS Lett. 2009;583(5):921–926. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2009.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Takeda S, et al. Local positive feedback regulation determines cell shape in root hair cells. Science. 2008;319(5867):1241–1244. doi: 10.1126/science.1152505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Foreman J, et al. Reactive oxygen species produced by NADPH oxidase regulate plant cell growth. Nature. 2003;422(6930):442–446. doi: 10.1038/nature01485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dadacz-Narloch B, et al. On the cellular site of two-pore channel TPC1 action in the Poaceae. New Phytol. 2013;200(3):663–674. doi: 10.1111/nph.12402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wymer CL, Bibikova TN, Gilroy S. Cytoplasmic free calcium distributions during the development of root hairs of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 1997;12(2):427–439. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1997.12020427.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Clough SJ, Bent AF. Floral dip: A simplified method for Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 1998;16(6):735–743. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1998.00343.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Monshausen GB, Bibikova TN, Weisenseel MH, Gilroy S. Ca2+ regulates reactive oxygen species production and pH during mechanosensing in Arabidopsis roots. Plant Cell. 2009;21(8):2341–2356. doi: 10.1105/tpc.109.068395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Monshausen GB, Messerli MA, Gilroy S. Imaging of the Yellow Cameleon 3.6 indicator reveals that elevations in cytosolic Ca2+ follow oscillating increases in growth in root hairs of Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2008;147(4):1690–1698. doi: 10.1104/pp.108.123638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Saeed AI, et al. TM4: A free, open-source system for microarray data management and analysis. Biotechniques. 2003;34(2):374–378. doi: 10.2144/03342mt01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Miyawaki A, et al. Fluorescent indicators for Ca2+ based on green fluorescent proteins and calmodulin. Nature. 1997;388(6645):882–887. doi: 10.1038/42264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Earley KW, et al. Gateway-compatible vectors for plant functional genomics and proteomics. Plant J. 2006;45(4):616–629. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2005.02617.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Czechowski T, Bari RP, Stitt M, Scheible WR, Udvardi MK. Real-time RT-PCR profiling of over 1400 Arabidopsis transcription factors: Unprecedented sensitivity reveals novel root- and shoot-specific genes. Plant J. 2004;38(2):366–379. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2004.02051.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Choi WG, Roberts DM. Arabidopsis NIP2;1, a major intrinsic protein transporter of lactic acid induced by anoxic stress. J Biol Chem. 2007;282(33):24209–24218. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M700982200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Arnon DI. Copper enzymes in isolated chloroplasts. Polyphenoloxidase in Beta vulgaris. Plant Physiol. 1949;24(1):1–15. doi: 10.1104/pp.24.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hallouin M, et al. Plasmalemma abscisic acid perception leads to RAB18 expression via phospholipase D activation in Arabidopsis suspension cells. Plant Physiol. 2002;130(1):265–272. doi: 10.1104/pp.004168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sakuma Y, et al. Functional analysis of an Arabidopsis transcription factor, DREB2A, involved in drought-responsive gene expression. Plant Cell. 2006;18(5):1292–1309. doi: 10.1105/tpc.105.035881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sistrunk ML, Antosiewicz DM, Purugganan MM, Braam J. Arabidopsis TCH3 encodes a novel Ca2+ binding protein and shows environmentally induced and tissue-specific regulation. Plant Cell. 1994;6(11):1553–1565. doi: 10.1105/tpc.6.11.1553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wright AJ, Knight H, Knight MR. Mechanically stimulated TCH3 gene expression in Arabidopsis involves protein phosphorylation and EIN6 downstream of calcium. Plant Physiol. 2002;128(4):1402–1409. doi: 10.1104/pp.010660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Alexandersson E, et al. Whole gene family expression and drought stress regulation of aquaporins. Plant Mol Biol. 2005;59(3):469–484. doi: 10.1007/s11103-005-0352-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ishitani M, et al. SOS3 function in plant salt tolerance requires N-myristoylation and calcium binding. Plant Cell. 2000;12(9):1667–1678. doi: 10.1105/tpc.12.9.1667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Quan R, et al. SCABP8/CBL10, a putative calcium sensor, interacts with the protein kinase SOS2 to protect Arabidopsis shoots from salt stress. Plant Cell. 2007;19(4):1415–1431. doi: 10.1105/tpc.106.042291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shi H, Ishitani M, Kim C, Zhu JK. The Arabidopsis thaliana salt tolerance gene SOS1 encodes a putative Na+/H+ antiporter. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97(12):6896–6901. doi: 10.1073/pnas.120170197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chung HS, et al. Regulation and function of Arabidopsis JASMONATE ZIM-domain genes in response to wounding and herbivory. Plant Physiol. 2008;146(3):952–964. doi: 10.1104/pp.107.115691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wildermuth MC, Dewdney J, Wu G, Ausubel FM. Isochorismate synthase is required to synthesize salicylic acid for plant defence. Nature. 2001;414(6863):562–565. doi: 10.1038/35107108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.