Abstract

Actinobacteria associated with 3 marine sponges, Cinachyra sp., Petrosia sp., and Ulosa sp., were investigated. Analyses of 16S rRNA gene clone libraries revealed that actinobacterial diversity varied greatly and that Ulosa sp. was most diverse, while Cinachyra sp. was least diverse. Culture-based approaches failed to isolate actinobacteria from Petrosia sp. or Ulosa sp., but strains belonging to 10 different genera and 3 novel species were isolated from Cinachyra sp.

Keywords: actinobacteria, marine sponge, Cinachyra, Petrosia, Ulosa

Actinobacteria isolated from terrestrial habitats are known to be the preeminent source of bioactive compounds. Recently, marine actinobacteria, especially those isolated from marine sponges, also have been identified as a rich source of bioactive metabolites (8, 17, 19). Although actinobacteria have been isolated from different marine habitats such as marine sediments, seawater, and marine invertebrates, marine sponges are of special interest, and many bioactive compounds isolated from marine sponges are already in clinical or preclinical trials (23). Bacteria associated with sponges are assumed to produce these compounds, as reported in the studies by Stierle et al.(28), Elyakov et al.(6), and Bewley et al.(4). This assumption is based on the following observations: (a) the correlation between the compounds produced by sponges and sponge taxonomy is weak; (b) distantly related sponges produce identical compounds; and (c) many compounds produced by sponges, such as peloruside A or laulimalide, are polyketides, which are a class of compounds produced by bacteria. Therefore, the study of microbial communities, especially actinobacteria, that are associated with different marine sponges is important in the search for novel compounds. Sponges can be divided into 2 groups based on the density of associated microorganisms (9): Sponges with a dense tissue matrix have low rates of water flowing through their bodies and therefore trap more bacteria; these sponges are referred to as high-microbial-abundance (HMA) sponges. In contrast, sponges with a more porous body matrix have higher rates of water flowing through their bodies and retain fewer bacteria in the mesophyl; these sponges are referred to as low-microbial-abundance (LMA) sponges. HMA sponges have been shown to harbor sponge-specific groups of bacteria, and LMA sponges have been shown to host few sponge-specific groups of bacteria (10, 31).

We recently isolated several actinobacteria from marine sponge samples (15, 17) collected mainly from Ishigaki Island, Okinawa Prefecture, Japan. These actinobacteria include phylogenetically new members of Streptomyces(16), a genus well known for the production of secondary metabolites. Many strains of this genus require salt for growth, indicating their marine origin. When screened for the production of bioactive metabolites, these strains have been found to produce new bioactive metabolites (13, 17, 30).

Petrosia sp. (Demospongiae, Petrosiidae), a common Mediterranean sponge, produces several bioactive polyacetylenes including acetylenic strongylodiols (20, 21, 35) and the steroid IPL-576,092, which is an antiasthmatic compound under clinical study (23). Ulosa sp. produces ulosantoin, which has insecticidal activity (32), and Cinachyra sp. produces the cytotoxic compound cinachyrolide A (7); however, to the best of our knowledge, the microbial communities associated with these sponges have not yet been studied. Only one report on the epibiotic bacteria of Petrosia sp. is available (5), and Vacelet and Donadey (31) found the cyanobacterium Aphanocapsa feldmanni in Petrosia sp., in specialized cells called bacteriocytes. Here, we describe actinobacteria associated with these 3 sponges using culture-dependent and -independent approaches.

Cinachyra sp., Petrosia sp., and Ulosa sp. were collected by scuba divers off the coast of Ishigaki Island, Okinawa Prefecture, Japan. DNAs were prepared using a Qiagen tissue kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA), and actinobacteria-specific primers S-C-Act-235-a-S-20 and S-C-Act-878-a-A-19, as described by Stach et al.(26), were used for 16S rRNA gene amplification. PCR products were cloned using a TOPO TA cloning kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and sequenced with M13 primers in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. Sequence anomalies were verified using Pintail (1) and Bellerophon (http://comp-bio.anu.edu.au/bellerophon/bellerophon.pl, 11), available on the Green-genes website. Phylogenetic neighbors were searched using the BLAST program against the sequences available in the DNA Database of Japan (DDBJ). A total of 93, 63, and 81 clones from Cinachyra sp., Petrosia sp., and Ulosa sp., respectively, were sequenced. We used 98.5% of 16S rRNA gene sequence similarity as the cutoff value (27) for an operational taxonomic unit and the Fastgroup II online program (36) for analysis. The sequences from Ulosa sp. were dereplicated into 58 operational taxonomic units (OTUs), those from Petrosia sp. were dereplicated into 48 OTUs, and those from Cinachyra sp. were dereplicated into only 5 OTUs (Table 1). Rarefaction curves were also calculated using the Fastgroup II online program. The curves showed that actinobacterial diversity is comparable in Petrosia sp. and Ulosa sp. but is very low in Cinachyra sp. (data not shown). Based on the Shannon–Wiener index [H′= −∑Si=1 (pilnpi)] and Simpson’s diversity index {D=∑ [ni (ni−1)/N(N−1)]} (12), actinobacterial diversity associated with these sponges was found to be distributed in the following order: Ulosa sp. > Petrosia sp. > Cinachyra sp. (Table 1).

Table 1.

Actinobacterial diversity associated with three sponge samples collected from Ishigaki Island, Okinawa Prefecture, Japan. Genera detected in the sponge actinobacteria clone library were determined by BLAST and RDP classifier (Wang et al., 2007*) analysis and biodiversity estimates

| Genera | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||

| Ulosa sp. | Petrosia sp. | Cinachyra sp. | |

| Family | |||

| Acidimicrobiaceae | Ilumatobacter | Acidimicrobium | Ilumatobacter* |

| Ferrimicrobium* | Ferrimicrobium* | Ferrimicrobium | |

| Ferrithrix* | Acidimicrobium | ||

| Acidothermaceae | Acidothermus* | ||

| Actinomycetaceae | Actinomyces* | Actinomyces | |

| Beutenbergiaceae | Salana* | ||

| Bogoriellaceae | Georgenia | ||

| Corynebacteriaceae | Corynebacterium* | ||

| Iamiaceae | Iamia* | Iamia* | Iamia* |

| Micrococcaceae | Arthrobacter | ||

| Micrococcus* | |||

| Rothia | |||

| Nesterenkonia | |||

| Mycobacteriaceae | Mycobacterium | ||

| Propionibacteriaceae | Propionibacterium | Propionibacterium | |

| Solirubrobacteraceae | Solirubrobacter | ||

| Streptomycetaceae | Streptomyces* | Streptomyces | |

| Thermomonosporaceae | Thermomonospora | ||

| “Williamsiaceae” | Williamsia | ||

| Unclassified | Microthrix | Microthrix | |

| Diversity estimates | |||

| Total number of clones | 81 | 63 | 93 |

| No of clones after dereplication (OTUs) | 58 | 48 | 5 |

| Total number of genera detected | 17 | 10 | 4 |

| OTUs/Clone | 0.71 | 0.76 | 0.05 |

| Shannon–Wiener index (nats) | 3.8863 | 3.6059 | 0.75 |

| Simpson’s diversity index (1/D) | 11.66 | 9.58 | 0.006 |

Although actinobacteria-specific primers were used for 16S rRNA gene amplification, sequences belonging to other bacterial phyla were also recovered in these 16S rRNA gene libraries. In the Ulosa sp. library, 75 of 81 sequences were members of the phylum Actinobacteria, and the remaining clones were assigned to the phyla Proteobacteria, Gemmatimonadetes, and Planctomycetes. In the Petrosia sp. library, in addition to actinobacteria, sequences belonging to Nitrospira and Gemmatimonadetes were detected. No sequences other than Actinobacteria were detected in the Cinachyra sp. library. Comparison with the DDBJ also showed that the sequences from Ulosa sp. were the most diverse among the 3 sponges, sharing 17 different genera of actinobacteria as their closest neighbors. Because of low sequence similarity, assignment to the correct phylogenetic position became difficult. The RDP classifier program (34) assigned these sequences into 8 different genera (Table 1), and the remaining sequences were grouped as unclassified. Sequences sharing 10 different genera as their closest neighbors were detected in the actinobacteria library prepared from Petrosia sp., and members of only 4 genera were detected in the Cinachyra sp. library. Members of the family Acidimicrobiaceae, commonly found in association with sponges (22), were detected in all 3 sponge samples. In fact, sequences belonging to this family were dominant in Cinachyra sp. and Petrosia sp. Sequences assigned to the genus Iamia, a genus in the family Iamiaceae, was also detected in all 3 sponge samples. This family is also closely related to the family Acidimicrobiaceae and is a member of the same suborder, Acidimicrobineae.

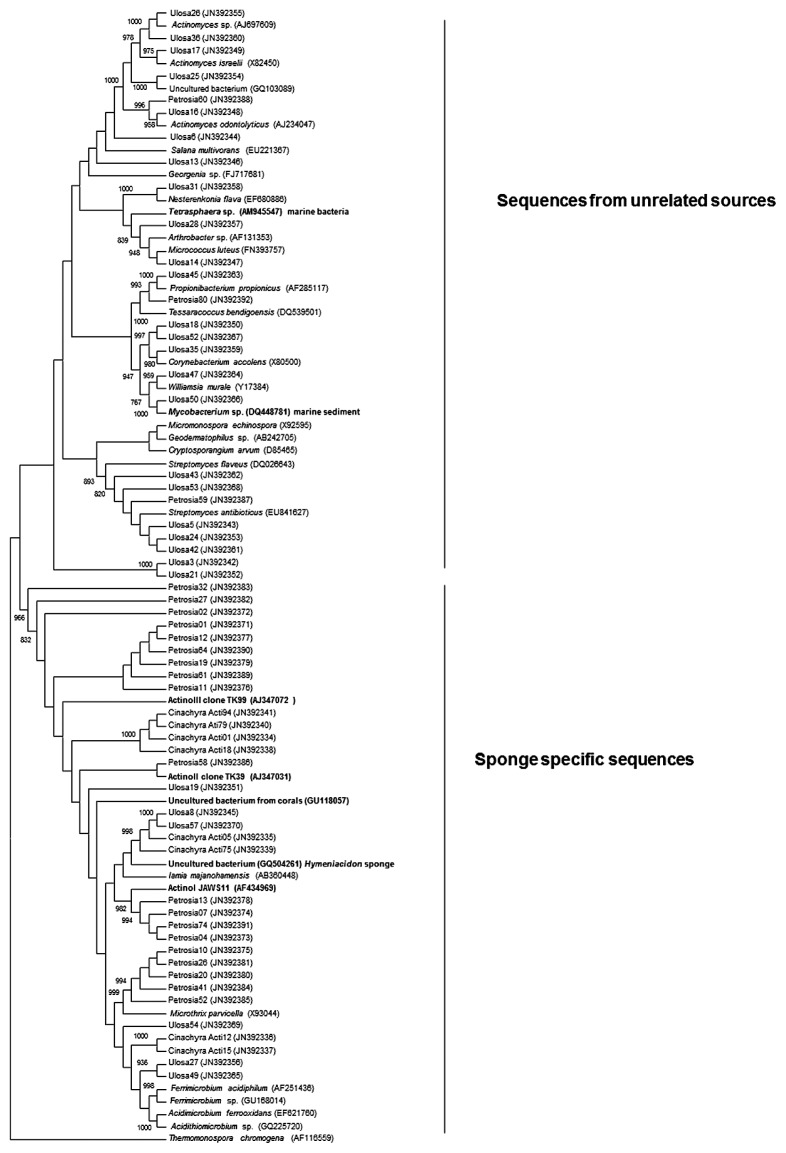

MEGA (29) was used to calculate neighbor-joining and maximum parsimony trees. A phylogenetic tree based on 29, 22, and 8 representative sequences from Ulosa sp., Petrosia sp., and Cinachyra sp., respectively, is shown in Fig. 1. The tree can be divided into 2 clades, one of which is dominated by the sequences generally isolated from marine sponges. Most of the sequences obtained from Cinachyra sp. and Petrosia sp., along with the sponge-specific actinobacterial sequences described by Hentschel et al.(9), were grouped in this clade. Some sequences from Petrosia sp. form a stable branch, with a bootstrap value of 98%, with sponge-specific actinobacteria (9). Sequences in this clade belong to Acidimicrobiaceae and related families. Very few sequences from Ulosa sp. are grouped in this clade. The reasons for the lack of sponge-specific actinobacteria reported so far in Ulosa sp. are not known; Ulosa sp. may be an LMA sponge, the type generally considered to lack sponge-specific microbial communities. The second clade contains sequences from diverse actinobacterial families and mainly from Ulosa sp. Only 3 sequences from Petrosia sp. are grouped in this clade. Also, many sequences in these libraries, especially those from Cinachyra sp. and Petrosia sp., share very low sequence similarities with the sequences in DNA databanks (data not shown). This analysis clearly showed the presence of several novel actinobacteria in these sponge samples. Although strains belonging to 17 different genera were detected in Ulosa sp., 2 major groups represented the genera Streptomyces and Actinomyces and constituted 14% and 7%, respectively, of total clones. In Petrosia sp., the most dominant clones, which represented 50% of total clones, shared only 89–91% similarity with Acidithiomicrobium sp. (GQ225721). In Cinachyra sp., the most dominant clones, which constituted 70% of total clones, exhibited maximum similarity (89–92%) with Ferrimicrobium sp. (EU199234), which was thus its closest phylogenetic neighbor. Differences among the actinobacterial communities in the sponges studied seems not to depend on ambient seawater as all the sponge samples were collected from the same geographical location yet they harbored different microbial communities. This finding also indicates that the actinobacterial communities associated with sponges vary from sponge to sponge and may be sponge-specific.

Fig. 1.

Phylogenetic dendrogram of representative actinobacteria clones from Ulosa sp., Petrosia sp., and Cinachyra sp. Related sequences were downloaded from the DNA Databank of Japan (DDBJ). The tree was calculated with a neighbor-joining algorithm and bootstrapped using 1000 replicates. Only those bootstrap values that exceeded 75% are shown.

We isolated actinobacteria from the sponges using 4 different culture media: starch-casein-nitrate agar (18), Gause 1 agar (2), manila clam (Ruditapes philippinarum) extract agar, and jewfish (Argyrosomus argentatus) extract agar (17). Jewfish and manila clam extract agars were used to provide complex (undefined) nutrients for bacterial growth. Isolated strains were maintained on ISP-2 medium [ISP-2M, ISP2; International Streptomyces project (25)] prepared in 50% seawater. Actinobacteria-like colonies with a powdery consistency were selected and spread on fresh ISP-2M until the cultures were pure. Interestingly, almost no actinobacterial colonies and only a few bacterial colonies appeared on the plates from Petrosia sp. and Ulosa sp. Based on colony morphology, only 13 strains were selected for further purification and 16S rRNA gene sequence analysis. Only 1 strain (PetSC-01) isolated from starch-casein-nitrate agar was closely related to Micromonospora sp. strain YIM 75717 (FJ911539), the only member of the phylum Actinobacteria isolated (Table 2). As observed in colony morphology, most strains were members of the phylum Proteobacteria. Notably, most of the strains isolated from Petrosia sp. and Ulosa sp. (9 of 13) exhibited maximum similarities with strains of marine origin. A list of strains isolated and their closest neighbors is provided in Table 2.

Table 2.

Antimicrobial activity of the acetone extracts of the sponges against different strains

| No. | Test strain | Ulosa sp. | Petrosia sp. |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Escherichia coli W-3876 | 2.0 | 0 |

| 2 | Micrococcus luteus ATCC 9341 | 2.5 | 1.0 |

| 3 | Candida albicans NBRC 1594 | 1.0 | 0 |

| 4 | Streptomyces alanosinicus NBRC 13493 | 2.0 | 0 |

| 5 | Streptomyces ambofaciens ATCC 23877 | 1.5 | 0 |

| 6 | Streptomyces capoamus NBRC 13411 | 2.3 | 0 |

| 7 | Streptomyces corchorusii NBRC 13032 | 1.5 | 0 |

| 8 | Streptomyces cyaneus NBRC 13346 | 1.9 | 0 |

| 9 | Streptomyces ferralitis SFOp68 | 1.9 | 0 |

| 10 | Streptomyces glauciniger NBRC 100913 | 1.5 | 0 |

| 11 | Streptomyces glomeratus LMG 19903 | 0 | 0 |

| 12 | Streptomyces lanatus NBRC 12787 | 2.1 | 0 |

| 13 | Streptomyces longwoodensis LMG 20096 | 1.9 | 0 |

| 14 | Streptomyces mirabilis NBRC 13450 | 1.9 | 0 |

| 15 | Streptomyces niveus NBRC 12804 | 1.5 | 1.0 |

| 16 | Streptomyces olivoverticillatus NBRC 15273 | 1.4 | 0 |

| 17 | Streptomyces paucisporeus NBRC 102072 | 2.3 | 0.9 |

| 18 | Streptomyces psammoticus NBRC 13971 | 1.3 | 0 |

| 19 | Streptomyces recifensis NBRC 12813 | 0 | 0 |

| 20 | Streptomyces sanglieri NBRC 100784 | 2.0 | 0 |

| 21 | Streptomyces speibonae NBRC 101001 | 1.9 | 0 |

| 22 | Streptomyces yanglinensis NBRC 102071 | 1.8 | 0 |

Zones of inhibition are given in cm.

The failure to isolate any actinobacterial strain from Petrosia sp. and Ulosa sp. is interesting and may be because of the production of antimicrobial compounds by these 2 sponges. Therefore, we tested the antimicrobial activity of acetone extracts from these sponges against Escherichia coli W-3876, Micrococcus luteus ATCC 9341, Candida albicans NBRC 1594, and multiple Streptomyces strains (Table 2). Paper discs (6 mm in diameter) containing the acetone extracts from the sponges were placed on plates pre-seeded with the test organisms. The extract from Ulosa sp. exhibited strong antimicrobial activities against almost all of the test organisms. The extract from Petrosia sp. exhibited activity against M. luteus and a few strains of Streptomyces, possibly because of the low concentration of antimicrobial compounds produced by this sponge and/or insufficient extraction by acetone. Interestingly, all of the strains isolated from Petrosia sp. and Ulosa sp. were resistant or tolerant to the compounds produced by the respective sponges (data not shown). The extracts from Petrosia sp. and Ulosa sp. were analyzed for antibiotics by liquid chromatography–high-resolution mass spectrometry. Ulosa sp. was found to produce papuamine and its stereoisomer haliclonadiamine, pentacyclic alkaloids with antifungal and antibacterial activities. These compounds have been reported to be produced by the marine sponge Haliclona sp. (3, 33). Petrosia sp. produced some polyacetylene compounds with cytotoxic and antimicrobial activities, as described previously in the Introduction. These compounds may have killed microorganisms in the sponges, and the 16S rRNA gene sequences recovered may have originated from the dead cells. The possibility that these antimicrobial compounds are produced by bacteria associated with the sponges cannot be ruled out; therefore, the successful isolation of such actinobacteria from these sponges will be important in future studies. Petrosia sp. has been classified as an HMA sponge. Vacelet and Donadey (31) observed the presence of many bacterial morphotypes in Petrosia ficiformis; however, because these bacteria reside inside bacteriocytes and are possibly in symbiosis with sponge cells, isolation can be difficult. The clone sequences also show the dominance of Acidimicrobiaceae, which are notoriously difficult to culture.

Because Cinachyra sp. is dominated by members of the family Acidimicrobiaceae, the above-mentioned arguments may also apply to this sponge. In contrast, several actinobacterial colonies on all of the tested media appeared from Cinachyra sp. Based on colony morphology, 41 strains were isolated, and their partial 16S rRNA gene sequences were determined. Strains representing 10 different genera (Actinomadura, Microbispora, Micromonospora, Nocardia, Nocardiopsis, Nonomuraea, Rhodococcus, Sphaerospo-rangium, Streptomyces, and Streptosporangium) were isolated (data not shown). The most dominant genus was Streptomyces (51%), followed by Rhodococcus (12%) and Micromonospora (9%). These genera are also dominant among the actinobacteria isolated from other marine sponges (17, 37). The isolation medium is also an important factor; we isolated only 43 strains from Cinachyra sp. and found that the most diverse actinobacteria (6 different genera) were isolated from the manila clam extract agar designed in our previous study on Haliclona sp. (17). To the best of our knowledge, diverse actinobacteria from a single sponge have not been reported previously. Although members of 9 different genera were isolated from this sponge, an important finding is that none of the actinobacteria isolated were detected in the clone library including Streptomyces, which constitutes 51% of the isolated strains. This finding may be due to the bias of the PCR primers used. In our earlier studies on Haliclona sp. (17), we were unable to amplify any Streptomyces sequences using the set of primers used in this study (26); however, several Streptomyces sequences were amplified from the same DNA template when Streptomyces-specific primers (24) were used. Many of these clones even shared high similarity with the strains isolated from Haliclona sp. (17). Our results showed that Cinachyra sp. is a good source of actinobacteria and that these strains may be a prolific source of novel compounds, especially members of the genus Streptomyces. The results of our metabolite search of Streptomyces isolated from Cinahyra sp. identified the novel isoprenoids JBIR-46, JBIR-47, and JBIR-48 (14).

The 16S rRNA gene clone library analysis of these sponges suggested that actinobacterial communities associated with the studied sponges vary greatly despite sharing the same geographical location. Cinachyra sp. and Petrosia sp. are dominated by sponge-specific actinobacteria described by Hentschel et al.(9), but Ulosa sp. lacks such groups. These results suggest that Ulosa sp. is an LMA sponge, which lacks sponge-specific bacteria, and that Cinachyra sp. and Petrosia sp. are HMA sponges, which harbor sponge-specific actinobacteria. This theory is supported further by the isolation of diverse actinobacteria from Cinachyra sp. We speculated that the reason for our failure to isolate actinobacteria from Ulosa sp. and Petrosia sp. was the production of antimicrobial compounds; however, the presence of previously unreported novel actinobacteria in these sponges is evident from 16S rRNA gene clone libraries, and further attempts at isolation would be highly desirable. These actinobacteria may be a good source of novel bioactive compounds.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by the New Energy and Industrial Technology Development Organization of Japan (NEDO). The authors thank Mr. Akihiko Kanamoto, OP Bio Factory Co., Ltd., for assistance in collecting and identifying the marine sponges.

References

- 1.Ashelford KE, Chuzhanova NA, Fry JC, Jones AJ, Weightman AJ. At least 1 in 20 16S rRNA sequence records currently held in public repositories is estimated to contain substantial anomalies. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2005;71:7724–7736. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.12.7724-7736.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Atlas RM, Parks LC. In: Handbook of Microbiological Media. Atlas RM, editor. CRC Press; Boca Raton, Florida: 2000. p. 33431. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baker BJ, Scheuer PJ, Shoolery JN. Papuamine, and antifungal pentacyclic alkaloid from a marine sponge, Haliclona sp. J Am Chem Soc. 1988;110:965–966. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bewley CA, Holland ND, Faulkner DJ. Two classes of metabolites from Theonella swinhoei are localized in distinct populations of bacterial symbionts. Experientia. 1996;52:716–722. doi: 10.1007/BF01925581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chelossi E, Milanese M, Milano A, Pronzato R, Riccardi G. Characterisation and antimicrobial activity of epibiotic bacteria from Petrosia ficiformis(Porifera, Demospongiae) J Exp Mar Biol Ecol. 2004;309:21–33. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Elyakov GB, Kuznetsova T, Mikhailov VV, Maltsev II, Voinov VG, Fedoreyev SA. Brominated diphenyl ethers from marine bacterium associated with the sponge Dysidea sp. Experientia. 1991;47:632–633. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fusetani N, Shinoda K, Matsunaga S. Bioactive marine metabolites. 48. Cinachyrolide A: a potent cytotoxic macrolide possessing two spiro ketals from marine sponge Cinachyra sp. J Am Chem Soc. 1993;115:3977–3981. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Garson MJ. The biosynthesis of sponge secondary metabolites: why it is important. In: Van Soest RWM, Van Kempen TMG, Braekman JC, editors. Sponges in Time and Space. Balkema; Rotterdam: 1994. pp. 427–440. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hentschel U, Hopke J, Horn M, Friedrich AB, Wagner M, Hacker J, Moore BS. Molecular evidence for a uniform microbial community in sponges from different oceans. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2002;68:4431–4440. doi: 10.1128/AEM.68.9.4431-4440.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hentschel U, Usher KM, Taylor MW. Marine sponges as microbial fermenters. FEMS Microbial Ecol. 2006;55:167–177. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2005.00046.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hill TC, Walsh KA, Harris JA, Moffet BF. Using ecological diversity measures with bacterial communities. FEMS Microbial Ecol. 2003;43:1–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2003.tb01040.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huber T, Faulkner G, Hugenholtz P. Bellerophon: a program to detect chimeric sequences in multiple sequence alignments. Bioinformatics. 2004;20:2317–2319. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Izumikawa M, Khan ST, Komaki H, Takagi M, Shin-ya K. JBIR-31, a new teleocidin analogue, produced by a salt requiring Streptomyces sp. NBRC 105896 isolated from a marine sponge. J Antibiot. 2010;63:33–36. doi: 10.1038/ja.2009.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Izumikawa M, Khan ST, Komaki H, Takagi M, Shin-ya K. Sponge-derived Streptomyces producing isoprenoids via mevalonate pathway. J Nat Prod. 2010;73:208–212. doi: 10.1021/np900747t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Khan ST, Izumikawa M, Motohashi K, Mukai A, Takagi M, Shin-ya K. Distribution of the 3-hydroxyl-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A reductase gene and isoprenoid production in marine-derived Actinobacteria. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2010;304:89–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2009.01886.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Khan ST, Tamura T, Takagi M, Shin-ya K. Streptomyces tateyamaensis sp. nov., Streptomyces marinus sp. nov. and Streptomyces haliclonae sp. nov., three novel species of Streptomyces isolated from marine sponge Haliclona sp. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2010;60:2775–2779. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.019869-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Khan ST, Hisayuki K, Motohashi K, Kozone I, Mukai A, Takagi M, Shin-ya K. Streptomyces associated with Haliclona sp.; biosynthetic genes for secondary metabolites and products. Environ Microbiol. 2011;13:391–403. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2010.02337.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Küster E, Williams ST. Selection of media for isolation of Streptomycetes. Nature. 1964;202:928–929. doi: 10.1038/202928a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee YK, Lee JH, Lee HK. Microbial symbiosis in marine sponges. J Microbiol. 2001;39:254–264. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lim YJ, Lee CO, Hong J, Kim DK, Im KS, Jung JH. Cytotoxic polyacetylenic alcohols from the marine sponge Petrosia species. J Nat Prod. 2001;64:1565–1567. doi: 10.1021/np010247p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Loya S, Rudi A, Kashman Y, Hizi A. Mode of inhibition of HIV-1 reverse transcriptase by polyacetylenetriol, a novel member of RNA- and DNA-directed DNA polymerases. Biochem J. 2002;362:685–692. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3620685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Montalvo NF, Mohamed NM, Enticknap JJ, Hill RT. Novel actinobacteria from marine sponges. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek. 2005;87:29–36. doi: 10.1007/s10482-004-6536-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Newman DJ, Cragg GM. Marine natural products and related compounds in clinical and advanced preclinical trials. J Nat Prod. 2004;67:1216–1238. doi: 10.1021/np040031y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rintala H, Nevalainen A, Rönkä E, Suutari M. PCR primers targeting the 16S rRNA gene for the specific detection of Streptomycetes. Mol. Cell Probes. 2001;15:337–347. doi: 10.1006/mcpr.2001.0379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shirling EB, Gottlieb D. Methods for characterization of Streptomyces species. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1966;16:313–340. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stach JE, Maldonado LA, Ward AC, Goodfellow M, Bull AT. New primers for the class Actinobacteria: application to marine and terrestrial environments. Environ Microbiol. 2003;5:828–841. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-2920.2003.00483.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stackebrandt E, Ebers J. Taxonomic parameters revisited: tarnished gold standards. Microbiol Today. 2006;8:6–9. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stierle AC, II, Cardellina JH, Singleton FL. A marine Micrococcus produces metabolites ascribed to the sponge Tedania ignis. Experientia. 1988;44:1021. doi: 10.1007/BF01939910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tamura K, Dudley J, Nei M, Kumar S. MEGA4: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis (MEGA) software version 4.0. Mol Biol Evol. 2007;24:1596–1599. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msm092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ueda JY, Khan ST, Takagi M, Shin-ya K. JBIR-58, a new salicylamide derivative, isolated from a marine sponge-derived Streptomyces sp. SpD081030ME-02. J Antibiot. 2010;63:267–269. doi: 10.1038/ja.2010.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vacelet J, Donadey C. Electron microscope study of the association between some sponges and bacteria. J Exp Mar Biol Ecol. 1977;30:301–314. [Google Scholar]

- 32.VanWagenen BC, Larsen R, Cardellina JH, II, Randazzo D, Lidert ZC, Swithenbank C. Ulosantoin, a potent insecticide from the sponge Ulosa ruetzleri. J Org Chem. 1993;58:335–337. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Volk CA, Lippert H, Lichte E, Köck M. Two new haliclamines from the arctic sponge Haliclona viscosa. Eur J Org Chem. 2004;14:3154–3158. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang QGM, Garrity J, Tiedje M, Cole JR. Naïve Bayesian Classifier for Rapid Assignment of rRNA Sequences into the New Bacterial Taxonomy. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2007;73:5261–5267. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00062-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Watanabe K, Tsuda Y, Hamada M, Omori M, Mori G, Iguchi K, Naoki H, Fujita T, Van RW, Soest Acetylenic strongylodiols from a Petrosia (Strongylophora) Okinawan Marine Sponge. J Nat Prod. 2005;68:1001–1005. doi: 10.1021/np040233u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yu Y, Breitbart M, McNairnie P, Rohwer F. FastGroupII: A web-based bioinformatics platform for analyses of large 16S rDNA libraries. BMC Bioinform. 2006;7:57. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-7-57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang H, Lee YK, Zhang W, Lee HK. Culturable actinobacteria from the marine sponge Hymeniacidon perleve: isolation and phylogenetic diversity by 16S rRNA gene-RFLP analysis. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek. 2006;90:159–169. doi: 10.1007/s10482-006-9070-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]