Abstract

N-Acylhomoserine lactone (AHL)-degrading enzyme, AiiM, was identified from the potato leaf-associated Microbacterium testaceum StLB037. In this study, we cloned eight aiiM gene homologues from other AHL-degrading Microbacterium strains. The similarity of the chromosomal locus of the aiiM gene is associated with the phylogenetic classification based on 16S rRNA. Degenerate PCR revealed that the aiiM gene was only conserved in AHL-degrading Microbacterium strains, but not in fifteen Microbacterium type strains or two Microbacterium isolates from other plants. These results suggested that the high level of AHL-degrading activity in Microbacterium strains was caused by the aiiM gene encoded on their chromosome.

Keywords: quorum sensing, N-acylhomoserine lactone, quorum quenching, AHL lactonase, Microbacterium sp

Quorum sensing is a population density-dependent regulation mechanism used by bacteria to regulate gene expression. In many Gram-negative bacteria, several types of N-acyl-l-homoserine lactones (AHLs) have been identified to be signal compounds involved in quorum sensing (2, 6). When AHL concentration increases and reaches a threshold due to the accumulation of AHL derived from each bacterial cell, AHL receptor proteins belonging to the LuxR protein family bind AHL and regulate the expression of many genes responsible for bioluminescence, pigment production or antibiotics production (2, 6). In particular, many Gram-negative plant pathogens control the expression of virulence factors by their quorum-sensing systems (13). In general, AHL-negative mutants show defects in their pathogenicity, so it is expected to inhibit the expression of virulence and infection of host cells by disrupting quorum-sensing signals. Many AHL-degrading genes have been cloned and characterized from various bacteria (12). AHL lactonase catalyzes AHL ring opening by hydrolyzing lactones and AHL acylase hydrolyzes the amide bond of AHLs (12). AHL-degrading genes have been utilized to prevent diseases by bacterial plant pathogens. The expression of AHL-lactonase in Pectobacterium carotovorum subsp. carotovorum significantly attenuates pathogenicity on some crops (3). Transgenic plants expressing AHL-lactonase exhibited significantly enhanced resistance to infection by P. carotovorum subsp. carotovorum(4).

In our previous studies, we isolated AHL-producing and -degrading bacteria from the leaf and root surface of potato (7, 10, 11). From the potato leaf, we isolated genus Microbacterium as the major AHL-degrading bacteria (7). We also cloned a novel AHL-degrading gene (aiiM) from M. testaceum StLB037 (8, 14). AiiM has AHL-lactonase activity and belongs to the α/β hydrolase fold family (8, 14). In this study, we investigated the diversity and distribution of the aiiM gene in the various Microbacterium strains.

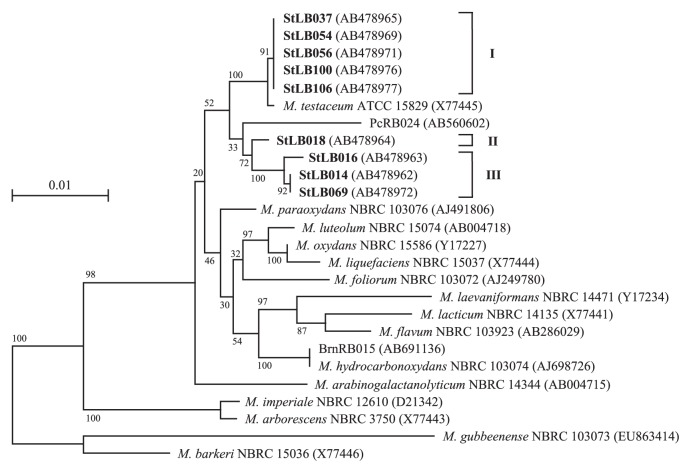

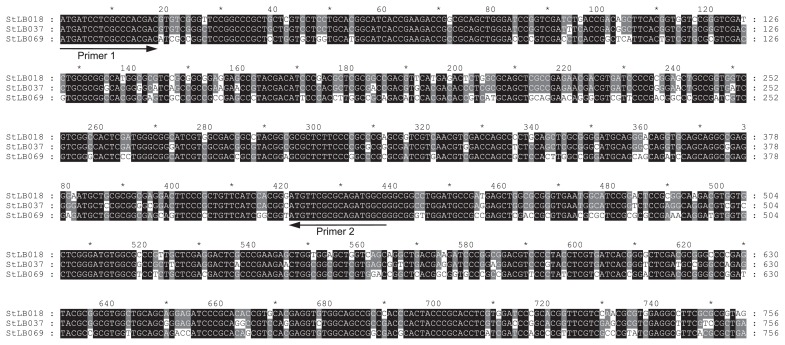

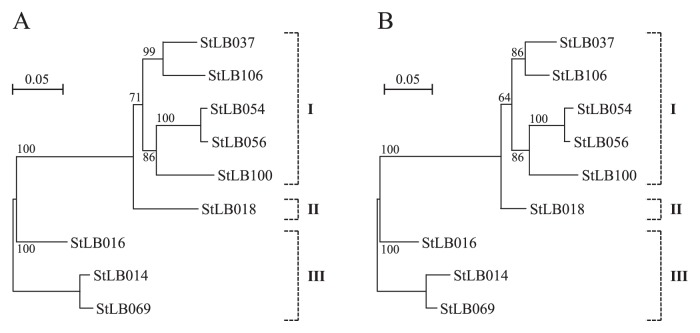

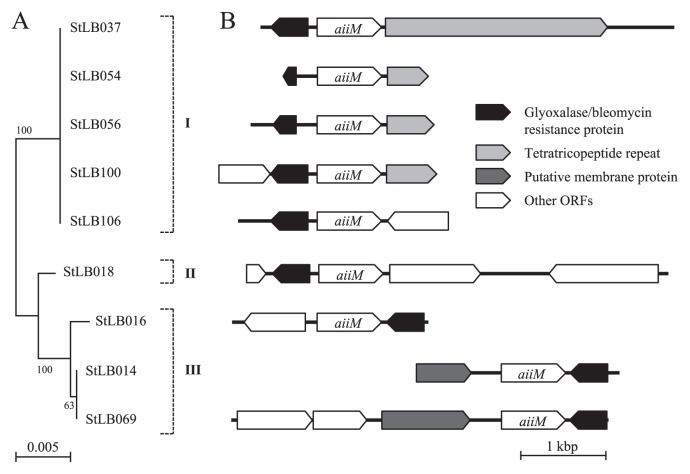

Based on the results of phylogenetic analysis of the 16S rRNA genes, we divided nine potato-associated and AHL-degrading Microbacterium strains into 3 groups (Fig. 1). We previously cloned the aiiM gene from StLB037, which belongs to group I. For cloning novel AHL-degrading genes from other groups, we selected two other strains, StLB018 from group II and StLB069 from group III. For cloning the AHL-degrading gene from StLB018 and StLB069, the E. coli DH5α/pLux28 reporter system was used as described previously (14). As a result, E. coli DH5α harboring pST18-1 clone from StLB018 or pST69-1 clone from StLB069 showed obvious AHL-degrading activity. When the inserted chromosomal fragments were sequenced, it was revealed that both pST18-1 and pST69-1 clones contained aiiM homologous ORFs. The DNA sequence of aiiM from StLB037 exhibited 88 and 77% identity with the aiiM from StLB018 and StLB069, respectively (Fig. 2). To confirm whether other AHL-degrading Microbacterium strains also conserve aiiM homologues, degenerate PCR primers, AiiMDG-F (5′-ATG ATC CTC GCC CAC GAC-3′) and AiiMDG-R (5′-CGC CAT CTG CGC GAA CAT-3′), were designed based on the most conserved nucleic acid sequences of the aiiM genes from StLB018, StLB037, and StLB069 (Fig. 2). As a result of PCR amplification, 438 bp DNA fragments were successfully amplified from all AHL-degrading Microbacterium strains and all PCR fragments contained partial aiiM sequences. To amplify the upstream and downstream regions of the partial aiiM genes from Microbacterium strains, inverse PCR was carried out. As a result of sequencing, complete sequences of all aiiM genes consisted of 756 nucleotides. In addition, E. coli DH5α harboring aiiM genes from all Microbacterium strains showed AHL-degrading activities against various AHLs (data not shown). These results demonstrated that the aiiM gene is widely conserved in AHL-degrading Microbacterium strains and has AHL-degrading activity. The nucleotide sequences of the aiiM gene and amino acid sequences of AiiM showed more than 76% sequence similarity, and the similarity of the sequence of the aiiM gene and AiiM was associated with the phylogenetic classification based on 16S rRNA in Microbacterium strains (Fig. 3). To indentify the chromosomal locus of the aiiM gene in Microbacterium strains, we compared the upstream and downstream regions of aiiM genes (Fig. 4). Glyoxalase/ bleomycin resistance gene homologues were located upstream of the aiiM gene in group I and II strains. On the other hand, this gene homologue was downstream of the aiiM gene in group III strains. In group I strains except for StLB106, tetratricopeptide repeat sequences were located downstream of the aiiM gene, and putative membrane protein genes were upstream of the aiiM gene in group III strains. These results demonstrated that the similarity of the chromosomal locus of the aiiM gene is also associated with the phylogenetic classification based on 16S rRNA in AHL-degrading Microbacterium strains.

Fig. 1.

Neighbor-joining tree of the 16S rRNA gene sequences obtained from AHL-degrading Microbacterium strains. For phyloge-netic analysis with the 16S rRNA gene, fifteen type strains of the genus Microbacterium and two isolates from other plants were used. The potato leaf-associated Microbacterium strains are shown in bold. Nine AHL-degrading isolates from potato plants were classed into three groups, I, II, and III. Scale bar represents 0.01 substitutions per nucleotide position. M. gubbeenense NBRC 103073 and M. barkeri NBRC 15036 were used as the outgroup to root the tree. DDBJ/EMBL/Gen-Bank accession numbers are given in parentheses. Bootstrap values (from 100 replicates) are indicated at the nodes.

Fig. 2.

Multiple alignments of DNA sequences of aiiM genes from the Microbacterium strains, StLB018, StLB037, and StLB069. Sequences were aligned using ClustalW (http://clustalw.ddbj.nig.ac.jp/) and shaded using with the Genedoc program (http://www.psc.edu/biomed/genedoc/). Gray and black shading indicates similar and identical amino acids, respectively. Arrows indicate the primer sites for degenerate PCR.

Fig. 3.

Neighbor-joining trees of the nucleotide sequences of aiiM genes (A) and amino acid sequences of AiiM (B) obtained from nine AHL-degrading Microbacterium strains. Scale bar represents 0.05 substitutions per nucleotide position. Bootstrap values (from 100 replicates) are indicated at the nodes.

Fig. 4.

(A) Neighbor-joining trees of the 16S rRNA gene sequences obtained from AHL-degrading Microbacterium strains. Scale bar represents 0.005 substitutions per nucleotide position. Bootstrap values (from 100 replicates) are indicated at the nodes. (B) Chromosomal locus of aiiM gene in AHL-degrading Microbacterium strains. Size, position, and orientation of the identified ORF in each clone are represented by pentagons. Scale bar=1 kbp.

To examine the presence of AHL-degrading activity in various Microbacterium strains, fifteen type strains and two laboratory stock strains were used for the AHL-degrading assay. Fifteen type strains were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) or NITE Biological Resource Center (NBRC). Strain PcRB024 and BrnRB015 were isolated from the root of rapeseed and scarlet runner bean, respectively. Microbacterium strains were cultivated in tryptic soy broth (TSB; Nippon Becton Dickinson, Tokyo, Japan) containing 10 μM N-hexanoyl-l-homoserine lactone (C6-HSL), N-decanoyl-l-homoserine lactone (C10-HSL), N-(3-oxohexanoyl)-l-homoserine lactone (3OC6-HSL), or N-(3-oxodecanoyl)-l-homoserine lactone (3OC10-HSL) (1). After 6, 12, 24 h, the remaining AHLs were visualized using an AHL-reporter strain, Chromobacterium violaceum CV026 (5) or VIR07 (9). The results of the AHL-degrading assay are shown in Table 1. All nine AHL-degrading strains degraded all the tested AHLs within 6 h. In contrast, all type strains and other plant isolates showed no or very weak degrading activity against C6-HSL and 3-oxo-C6-HSL. To confirm the presence of the aiiM gene, the internal region of the aiiM gene was amplified by degenerate PCR using specific primers designed as above; however, the partial aiiM gene fragments were not amplified from either the chromosome of type strains or other plant isolates (Table 1). These results suggested that the high level of AHL-degrading activity in nine Microbacterium strains was caused by the aiiM gene encoded on their chromosome. Some strains showed high degrading activity against only C10-HSL and 3-oxo-C10-HSL. In a previous study, many AHL acylases showed degrading activity against only AHLs with a long acyl chain (12); therefore, we assumed that the type strains and other plant isolates have putative AHL-acylase.

Table 1.

Identification and characterization of the AHL-degrading bacteria isolated in this study

| Strainsa | Related species | AHL-degrading activityb | aiiM genec | Source | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| C6-HSL | 3OC6-HSL | C10-HSL | 3OC10-HSL | ||||

| StLB014 | Microbacterium sp. | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | + | potato |

| StLB016 | Microbacterium sp. | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | + | potato |

| StLB018 | Microbacterium sp. | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | + | potato |

| StLB037 | Microbacterium testaceum | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | + | potato |

| StLB054 | Microbacterium testaceum | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | + | potato |

| StLB056 | Microbacterium testaceum | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | + | potato |

| StLB069 | Microbacterium sp. | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | + | potato |

| StLB100 | Microbacterium testaceum | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | + | potato |

| StLB106 | Microbacterium testaceum | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | + | potato |

| PcRB024 | Microbacterium sp. | − | + | +++ | ++ | NA | scarlet runner bean |

| BrnRB015 | Microbacterium hydrocarbonoxydans | − | + | − | + | NA | rapeseed |

| ATCC 15829T | Microbacterium testaceum | − | + | − | + | NA | Chinese paddy |

| NBRC 103076T | Microbacterium paraoxydans | − | + | ++ | ++ | NA | blood from a child |

| NBRC 15586T | Microbacterium oxydans | − | + | ++ | ++ | NA | air |

| NBRC 14344T | Microbacterium arabinogalactanolyticum | − | + | +++ | +++ | NA | soil |

| NBRC 103074T | Microbacterium hydrocarbonoxydans | − | + | ++ | ++ | NA | soil |

| NBRC 103923T | Microbacterium flavum | − | − | + | ++ | NA | ascidian |

| NBRC 15074T | Microbacterium luteolum | − | + | ++ | ++ | NA | soil |

| NBRC 103072T | Microbacterium foliorum | − | + | + | ++ | NA | phyllosphere of grasses |

| NBRC 103073T | Microbacterium gubbeenense | − | − | − | − | NA | smear-ripened cheese |

| NBRC 14135T | Microbacterium lacticum | − | − | + | + | NA | unknown |

| NBRC 15037T | Microbacterium liquefaciens | − | + | + | + | NA | milk |

| NBRC 12610T | Microbacterium imperiale | − | + | + | + | NA | imperial moth |

| NBRC 15036T | Microbacterium barkeri | − | − | − | − | NA | sewage |

| NBRC 14471T | Microbacterium laevaniformans | − | − | − | − | NA | activated sludge |

| NBRC 3750T | Microbacterium arborescens | − | + | + | − | NA | unknown |

T, type strain.

−, no degrading activity observed; +, low degrading activity (completely degraded 10 μm AHL within 24 h); ++, intermediate degrading activity (completely degraded 10 μm AHL within 12 h); +++, high degrading activity (completely degraded 10 μm AHL within 6 h).

NA, not amplified.

Many classes of AHL-degrading enzymes have been identified from a wide range of resources, including Gram-positive and -negative bacteria, fungi, plants, animals, humans, and others (12). Although most of these enzymes degrade AHLs in two ways, as AHL-lactonases or AHL-acylases, they showed no significant sequencing identity among different classes (12). Correspondingly, the amino acid sequences of AiiM from AHL-degrading Microbacterium strains showed close similarity, but less similarity to a different class of known AHL lactonases (14). M. testaceum ATCC 15829 and Microbacterium sp. PcRB024 showed a close phylogenetic relationship with the nine AHL-degrading Microbacterium strains (Fig. 1), but these two strains did not have significant AHL-degrading activity or conserve the aiiM gene in their genomes. These results suggested that the aiiM gene was not generally conserved among the genus Microbacterium, but was spread among Microbacterium strains in a specific ecosystem. However, the transposon insertion site was not found in each sequence around the aiiM gene (data not shown); therefore, it was assumed that the aiiM gene homologue did not spread to other Microbacterium strains by horizontal transmission of the transposon.

In summary, the aiiM gene was found in the nine AHL-degrading Microbacterium strains but not in any other tested strains by PCR procedures. At this time, the biological and ecological significance of AHL-degrading bacteria and enzymes has not been elucidated. AHL might not be a true substrate for the reported AHL-degrading enzymes; therefore, AHL-degrading Microbacterium strains might not exist for the inhibition of quorum sensing in nature. On the other hand, co-inoculation of AHL-degrading strains, StLB018 and StLB037, with P. carotovorum subsp. carotovorum decreased symptom development in potato soft rot (7). AHL-degrading activity in Microbacterium strains might be useful for protecting plants from bacterial infection as symbiotic participants. Microbacterium strains are known as endophytic bacteria that reside within plant hosts without causing disease symptoms (15). Also, Microbacterium strains, which have no AHL-degrading activity, coexisted with AHL-degrading Microbacterium strains on the potato leaf (data not shown). To use potato leaf-associated Microbacterium strains as biocontrol agents, it might be important to check for the presence of the aiiM gene by PCR using our degenerate primers.

The nucleotide sequences of the aiiM gene from Microbacterium sp. StLB014, StLB016, StLB018, StLB054, StLB056, StLB069, StLB100 and StLB106 have been deposited in DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank databases under accession nos. AB668537–AB668544, respectively.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Grants-in-Aid from the Bio-oriented Technology Research Advancement Institution (BRAIN), Japan.

References

- 1.Chhabra SR, Harty C, Hooi DS, Daykin M, Williams P, Telford G, Pritchard DI, Bycroft BW. Synthetic analogues of the bacterial signal (quorum sensing) molecule N-(3-oxododecanoyl)-l-homoserine lactone as immune modulators. J Med Chem. 2003;46:97–104. doi: 10.1021/jm020909n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.de Kievit TR, Iglewski BH. Bacterial quorum sensing in pathogenic relationships. Infect Immun. 2000;68:4839–4849. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.9.4839-4849.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dong YH, Xu JL, Li XZ, Zhang LH. AiiA, an enzyme that inactivates the acylhomoserine lactone quorum-sensing signal and attenuates the virulence of Erwinia carotovora. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:3526–3531. doi: 10.1073/pnas.060023897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dong YH, Wang LH, Xu JL, Zhang HB, Zhang XF, Zhang LH. Quenching quorum-sensing-dependent bacterial infection by an N-acyl homoserine lactonase. Nature. 2001;411:813–817. doi: 10.1038/35081101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McClean KH, Winson MK, Fish L, et al. Quorum sensing and Chromobacterium violaceum: exploitation of violacein production and inhibition for the detection of N-acylhomoserine lactones. Microbiology. 1997;143:3703–3711. doi: 10.1099/00221287-143-12-3703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miller MB, Bassler BL. Quorum sensing in bacteria. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2001;55:165–199. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.55.1.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morohoshi T, Someya N, Ikeda T. Novel N-acylhomoserine lactone-degrading bacteria isolated from the leaf surface of Solanum tuberosum and their quorum-quenching properties. Biosci Biotech Biochem. 2009;73:2124–2127. doi: 10.1271/bbb.90283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morohoshi T, Wang WZ, Someya N, Ikeda T. Genome sequence of Microbacterium testaceum StLB037, an N-acylhomoserine lactone-degrading bacterium isolated from the potato leaves. J Bacteriol. 2011;193:2072–2073. doi: 10.1128/JB.00180-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morohoshi T, Kato M, Fukamachi K, Kato N, Ikeda T. N-Acylhomoserine lactone regulates violacein production in Chromobacterium violaceum type strain ATCC12472. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2008;279:124–130. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2007.01016.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rashid R, Morohoshi T, Someya N, Ikeda T. Degradation of N-acylhomoserine lactone quorum sensing signal molecules by potato root surface-associated Chryseobacterium strains. Microbes Environ. 2011;26:144–148. doi: 10.1264/jsme2.me10207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Someya N, Morohoshi T, Okano N, Otsu E, Usuki K, Sayama M, Sekiguchi H, Ikeda T, Ishida S. Distribution of N-acylhomoserine lactone-producing fluorescent pseudomonads in the phyllosphere and rhizosphere of potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) Microbes Environ. 2009;24:305–314. doi: 10.1264/jsme2.me09155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Uroz S, Dessaux Y, Oger P. Quorum sensing and quorum quenching: the yin and yang of bacterial communication. Chembiochem. 2009;10:205–216. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200800521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.von Bodman SB, Bauer WD, Coplin EL. Quorum sensing in plant-pathogenic bacteria. Annu Rev Phytopathol. 2003;41:455–482. doi: 10.1146/annurev.phyto.41.052002.095652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang WZ, Morohoshi T, Ikenoya M, Someya N, Ikeda T. AiiM, a novel class of N-acylhomoserine lactonase from the leaf-associated bacterium Microbacterium testaceum. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2010;76:2524–2530. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02738-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zinniel DK, Lambrecht P, Harris NB, Feng Z, Kuczmarski D, Higley P, Ishimaru CA, Arunakumari A, Barletta RG, Vidaver AK. Isolation and characterization of endophytic colonizing bacteria from agronomic crops and prairie plants. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2002;68:2198–2208. doi: 10.1128/AEM.68.5.2198-2208.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]