Abstract

Clarifying the identity and enzymatic activities of microorganisms associated with the decomposition of organic materials is expected to contribute to the evaluation and improvement of composting processes. In this study, we examined the cellulolytic and hemicellulolytic abilities of bacteria isolated from sawdust compost (SDC) and coffee residue compost (CRC). Cellulolytic bacteria were isolated using Dubos mineral salt agar containing azurine cross-linked (AZCL) HE-cellulose. Bacterial identification was performed based on the sequence analysis of 16S rRNA genes, and cellulase, xylanase, β-glucanase, mannanase, and protease activities were characterized using insoluble AZCL-linked substrates. Eleven isolates were obtained from SDC and 10 isolates from CRC. DNA analysis indicated that the isolates from SDC and CRC belonged to the genera Streptomyces, Microbispora, and Paenibacillus, and the genera Streptomyces, Microbispora, and Cohnella, respectively. Microbispora was the most dominant genus in both compost types. All isolates, with the exception of two isolates lacking mannanase activity, showed cellulase, xylanase, β-glucanase, and mannanase activities. Based on enzyme activities expressed as the ratio of hydrolysis zone diameter to colony diameter, it was suggested that the species of Microbispora (SDCB8, SDCB9) and Paenibacillus (SDCB10, SDCB11) in SDC and Microbispora (CRCB2, CRCB6) and Cohnella (CRCB9, CRCB10) in CRC contribute to efficient cellulolytic and hemicellulolytic processes during composting.

Keywords: AZCL-substrates, bacteria, cellulolytic activity, compost, hemicellulolytic activity

Cellulose, which represents approximately 1.5×1012 tons of the annual biomass produced through photosynthesis, is the most abundant organic polymer and is considered to be an almost inexhaustible source of raw materials for various products (44). Furthermore, hemicelluloses, which consist of a heterogeneous group of polysaccharides that includes xylans, β-glucans, and mannans, are also important constituents of plant cell walls (5). The cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin contents of organic wastes vary depending on the source (19, 35). For example, coffee residue consists of 35% cellulose, 46% hemicellulose, and 19% lignin (40), whereas sawdust typically contains 40%–50% cellulose, 25%–35% hemicellulose, and 20%–30% lignin (43). Due to their abundance, the recycling of lignocellulosic materials is indispensable for the carbon cycle and requires numerous time-consuming processes, which include mechanical, chemical, thermal, and biological treatments (31). Degradation of lignocellulosic materials in their natural environments proceeds exclusively through biological processes (6). Therefore, investigating the microbial communities inhabiting compost and clarifying their role in the biodegradation of organic components is an important step for improving composting processes.

During composting, numerous types of microorganisms influence the biological degradation of wastes. Although fungi are the main cellulase-producing microorganisms, a few species of bacteria and actinomycetes have also been reported to produce cellulase (44, 58) and are involved throughout the degradation process (51). Cellulolytic and hemicellulolytic bacteria have been isolated from a wide diversity of environments, such as soils, composts, decaying plant wastes, and the feces of ruminant animals (30). Bacteria and actinomycetes play specific roles in the biodegradation of organic materials during composting (14, 33).

The biodegradation of waste materials occurs by the concerted action of various microorganisms which produce a series of enzymes that contribute to the bioconversion process (37). These enzymes include cellulases, hemicellulases, and pectinases, which function synergistically to degrade complex cell-wall molecules (9). Most studies of biodegradation processes have emphasized the role of fungi because of their capability of producing and secreting high amounts of enzymes (30). Several methods based on the use of soluble or insoluble substrates have been applied to determine the cellulolytic and hemicellulolytic activities of microorganisms (47). However, most of these methods are not quantitative or sufficiently sensitive due to the poor correlation between enzyme activity and the resulting hydrolysis zone diameter (30). Thus, to more accurately evaluate cellulolytic and hemicellulolytic microorganisms, an efficient plate-screening method is required.

Recently, a few chromogenic substrates have been used for measuring microbial enzymatic activities. In particular, azurine cross-linked (AZCL) substrates are commercially available and have been successfully applied for the evaluation of enzymatic activities (8, 36). During the degradation of AZCL substrates, colored particles are released and form a blue-colored zone around the colony, with the intensity of the colored zone being based on several parameters, including the substrate and enzyme concentrations, and the catalytic properties of the active enzyme. Using AZCL substrates, a positive and quantitative correlation has been demonstrated between enzyme activity and the diameters of the blue zones (8, 36, 48).

In a previous report, we investigated the cellulolytic and hemicellulolytic abilities of fungi isolated from mature sawdust (SDC) and coffee residue composts (CRC). In this study, we evaluated the cellulolytic and hemicellulolytic abilities of bacteria isolated from SDC and CRC in an attempt to clarify the role of these bacteria in the biodegradation of organic wastes during the composting process.

Materials and Methods

Isolation of cellulose-decomposing bacteria

SDC produced from the residue of medium used to culture mushrooms was obtained from the Agricultural Cooperative Association of Saitama Prefecture, Japan, and CRC was collected from a composting center located in Hiroshima Prefecture, Japan. The two types of compost were produced by composting heaps of the respective starting materials that were turned periodically during a 2- to 3-month period until reaching maturity. The chemical and biological properties of SDC and CRC are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Chemical and biological properties of SDC and CRC

| Compost type | Dry matter (g kg−1) | Total (g kg−1)‡ | C/N ratio | Cellulose degrading bacteria (×108 cfu g−1)‡ | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| C | N | P | ||||

| SDC | 538 | 456 | 15 | 12 | 30.0 | 11.7 |

| CRC | 390 | 448 | 21 | 0.7 | 20.9 | 9.9 |

Values expressed on an oven-dry basis.

SDC: sawdust compost.

CRC: coffee residue compost.

Bacteria were isolated from SDC and CRC using a dilution plate method. Briefly, the primary suspensions were prepared by suspending 10 g of each compost type in 90 mL sterile distilled water, and the resulting suspensions were then shaken at 150 rpm for 30 min at room temperature. Ten-fold serial dilutions were then prepared in sterilized distilled water. One-hundred microliters from the 10−7 dilution of each compost type was spread on Dubos mineral salt agar medium (NaNO3, 0.5 g L−1; K2HPO4, 1 g L−1; MgSO4·7H2O, 0.5 g L−1; FeSO4·7H2O, 0.02 g L−1; KCl, 0.2 g L−1; and agar, 20 g L−1, pH 7.5) (10), which was supplemented with 0.05% (w/v) AZCL HE-Cellulose (Megazyme, Bray, Ireland) as the sole carbon source. Five plates were prepared for each compost type and were incubated at 35°C for 7 days. Colonies of cellulose-degrading bacteria, which were surrounded by a blue halo zone indicating cellulase activity, were developed on the plates. Each representative plate was selected from SDC and CRC, on which 11 and 10 colonies of cellulose-degrading bacteria appeared, respectively. All colonies of cellulose-degrading bacteria were isolated from each plate and transferred to Trypto-Soya Agar plates (TSA; Nissui Pharmaceutical, Tokyo, Japan). A single colony of each isolate was transferred repeatedly on TSA to obtain a pure culture.

DNA extraction and PCR amplification

Bacterial cells used for DNA extraction were cultivated on TSA medium for approximately 5 days at 35°C. Genomic DNA was extracted by the boiling method. Briefly, a bacterial colony was picked up from the surface of a TSA plate with a 10-μL micropipette tip and suspended in 25 μL sterile water in a PCR tube. The tubes were heated at 94°C for 5 min using a thermal cycler (GeneAmp PCR System 2700; Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA), and the extracted DNA solution was used as a template for PCR amplification. PCR was performed with a pair of universal bacterial primers targeting the 16S rRNA gene; 27F (GAGTTTGATCMTG GCTCAG) and 1492R (TACGGYTACCTTGTTACGACTT) as forward and reverse primers, respectively, according to Lane (28). PCR was performed in a 50-μL volume containing 10 ng genomic DNA, 25 μL 2× PCR Buffer for KOD FX Neo, 10 μL dNTP mix (2 mM each), 1 U KOD FX Neo polymerase (Toyobo, Osaka, Japan), and 1.5 μL (10 μM) of each primer (27F and 1492R). After an initial denaturation step at 94°C for 2 min, target DNA was amplified in 30 cycles. Each cycle consisted of denaturation at 98°C for 10 s, annealing at 51°C for 30 s, and extension at 68°C for 90 s. A final extension was performed at 68°C for 5 min. The PCR products were analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis. After electrophoresis, gels were stained with ethidium bromide and visualized by UV transillumination with the printgraph AE-6932GXCF system (ATTO, Tokyo, Japan). The PCR products were purified using a QIAquick PCR Purification Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Sequencing and data analysis

The 16S rRNA gene sequences of isolated bacteria were determined by direct sequencing of the purified PCR-amplified 16S rDNA fragments. Sequencing was performed using the BigDye Terminator v3.1 Cycle Sequencing Kit (Applied Biosystems) on a 3730xl DNA analyzer (Applied Biosystems). Nearly complete 16S rRNA gene sequences were obtained from each isolate using the following oligonucleotides: 27F, 515F (GTGCCAGCMGCCGCG GTAA) (52), F984 (AACGCGAAGAACCTTAC) (20), and 519R (GWATTACCGCGGCKGCTG) (28).

The obtained 16S rDNA sequences of isolated bacteria were compared with those of other known species deposited in the GenBank database (http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi) using the BLASTN 2.2.24 program (61). A phylogenetic tree based on partial 16S rRNA sequences was constructed using the neighbor-joining method contained within the Clustal X program (50) and MEGA4 software (46).

Enzyme assays

Dubose mineral agar medium containing 0.05% of an AZCL-substrate (AZCL-HE-cellulose, -arabinoxylan, -barly β-glucan, -galactomannan, or -casein) as the sole carbon source was applied to measure cellulase, xylanase, β-glucanase, mannanase, and protease activities, respectively, of isolated bacteria. To evaluate enzyme activities, bacterial isolates were point-inoculated on AZCL substrate-Dubos agar plate surfaces and were incubated for 7 days at 35°C. Enzymatic activity was expressed as the Substrate Hydrolysis Index, which was calculated as the ratio between the average diameter (d) of the hydrolysis zone of substrate (the blue zone around the bacterial colony) and the average diameter of the bacterial colony (D) in millimeters (8).

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers

The nucleotide sequences determined in this study have been deposited in GenBank under nucleotide accession numbers JN617210–JN617230.

Results

Isolation and phylogenetic analysis of bacterial isolates

The two compost types, SDC and CRC, were subjected to the isolation of cellulolytic bacteria, whose cellulolytic and hemicellulolytic activities were subsequently characterized. All colonies of cellulose-degrading bacteria surrounded by a blue halo zone were isolated from each plate of SDC and CRC, selected from 5 replicate plates. The 16S rRNA gene sequence analyses of the 21 bacterial isolates revealed that they were closely related to four genera: Streptomyces, Microbispora, Paenibacillus, and Cohnella. The genera Streptomyces and Microbispora were dominant in both compost types, whereas Paenibacillus was only obtained from SDC and Cohnella was only isolated from CRC (Table 2).

Table 2.

Top BLAST results for bacterial 16S rRNA sequences showing GenBank accession numbers of bacteria isolated from SDC and CRC

| Isolate No. | GenBank accession No. | Top BLAST hit GenBank | Similarity (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| SDCB1 | JN617210 | Streptomyces fumigatiscleroticus NRRL B-3856T (DQ442499) | 99.2 |

| SDCB2 | JN617211 | Streptomyces mexicanus NBRC 100915 (AB249966) | 99.9 |

| SDCB3 | JN617212 | Microbispora sp. 211020 (FJ261972) | 99.7 |

| SDCB4 | JN617213 | Microbispora sp. 211020 (FJ261972) | 99.8 |

| SDCB5 | JN617214 | Microbispora sp. 211020 (FJ261972) | 99.7 |

| SDCB6 | JN617215 | Streptomyces mexicanus NBRC 100915 (AB249966) | 99.9 |

| SDCB7 | JN617216 | Microbispora sp. 211020 (FJ261972) | 99.8 |

| SDCB8 | JN617217 | Microbispora sp. 211020 (FJ261972) | 99.8 |

| SDCB9 | JN617218 | Microbispora sp. 211020 (FJ261972) | 99.8 |

| SDCB10 | JN617219 | Paenibacillus woosongensis YB-45 (AY847463) | 99.7 |

| SDCB11 | JN617220 | Paenibacillus woosongensis YB-45 (AY847463) | 99.7 |

|

| |||

| CRCB1 | JN617221 | Streptomyces fumigatiscleroticus NBRC 12999 (AB184248) | 99.4 |

| CRCB2 | JN617222 | Microbispora sp. 211020 (FJ261972) | 99.8 |

| CRCB3 | JN617223 | Microbispora sp. H886 (AY445642) | 99.6 |

| CRCB4 | JN617224 | Microbispora sp. 211020 (FJ261972) | 99.8 |

| CRCB5 | JN617225 | Microbispora sp. H886 (AY445642) | 99.6 |

| CRCB6 | JN617226 | Microbispora sp. 211020 (FJ261972) | 99.7 |

| CRCB7 | JN617227 | Microbispora sp. 211020 (FJ261972) | 99.8 |

| CRCB8 | JN617228 | Microbispora sp. 211020 (FJ261972) | 99.8 |

| CRCB9 | JN617229 | Cohnella panacarvi (AB271056) | 96.1 |

| CRCB10 | JN617230 | Cohnella panacarvi (AB271056) | 96.2 |

SDCB: bacteria isolated from saw dust compost; CRCB: bacteria isolated from coffee residue compost. Numbers showed the isolate number.

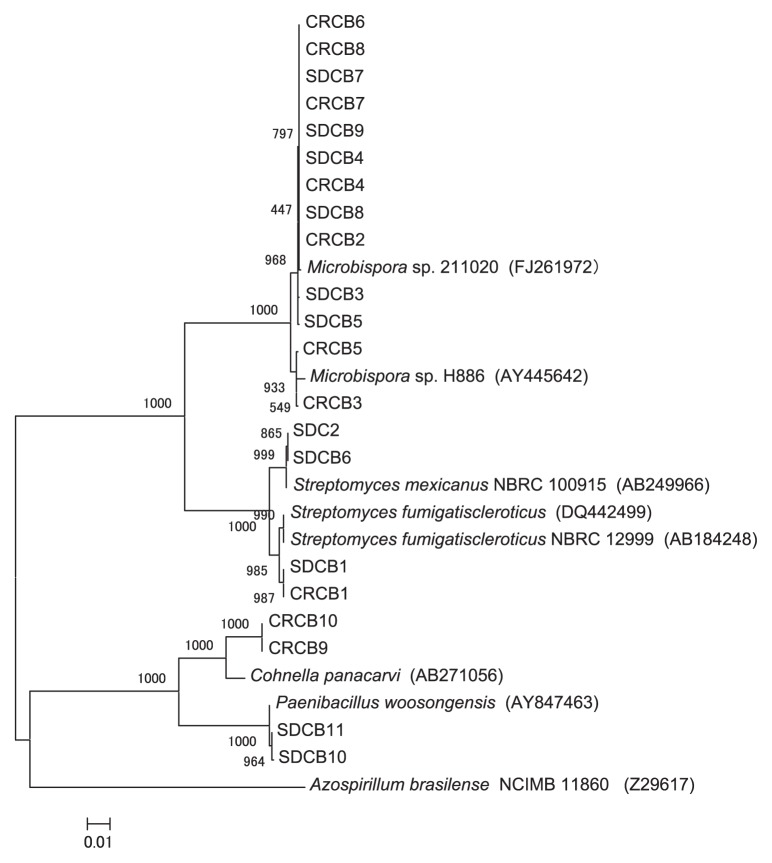

With regard to the SDC bacterial isolates, BLAST search results and the constructed phylogenetic tree based on the 16S rRNA gene sequence data (Fig. 1) showed that three isolates (SDCB1, SDCB2, and SDCB6) were closely related (>99% similarity) to two different species of the genus Streptomyces. Six of the 11 isolates (54.5%) displayed >99% similarity to members of the genus Microbispora, while the remaining two isolates (SDCB10 and SDCB11) matched the genus Paenibacillus, with 99.7% maximum similarity to Paenibacillus woosongensis (Table 2).

Fig. 1.

Neighbor-joining tree showing the relationship between the 16S rRNA gene sequences from bacteria isolated from SDC and CRC. Bootstrap values of neighbor-joining analysis from 1,000 replications are shown on the branches. Scale bar represents the number of changes per nucleotide position (substitution/site).

Concerning the CRC bacterial isolates, BLAST search results and the constructed 16S rRNA phylogenetic tree revealed that one isolate (CRCB1) showed 99.4% similarity to Streptomyces fumigatiscleroticus, while seven isolates displayed ≥99% similarity to the genus Microbispora. Furthermore, two isolates (CRCB9 and CRCB10) exhibited relatively low similarity (96.1% and 96.2%, respectively) to Cohnella panacarvi (Table 2 and Fig. 1).

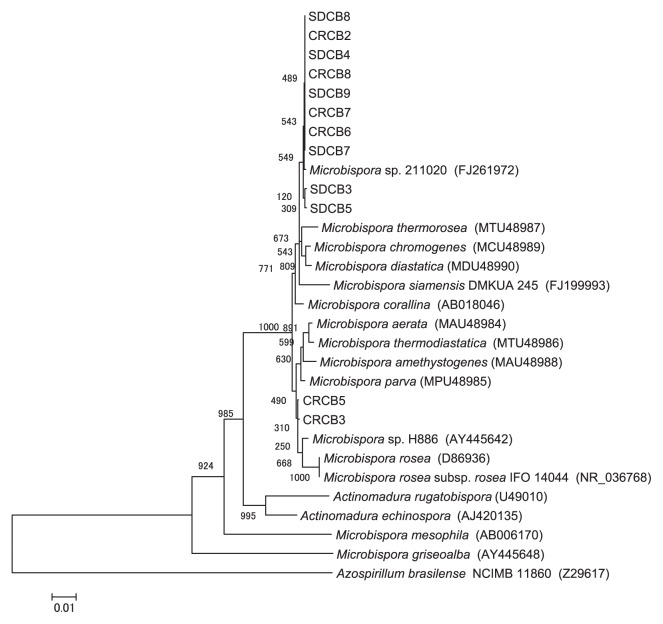

Based on the BLAST results, none of the Microbispora isolates could be identified to the species level due to a lack of high similarity to species within the genus. Thus, the phylogenetic relationship between the 16S rRNA sequences of the Microbispora isolates and those of Microbispora species deposited in the GenBank database were further examined. The constructed phylogenetic tree showed that two isolates (CRCB3 and CRCB5) were closely related to Microbispora rosea subsp. rosea (AY445647), whereas the other Microbispora isolates were not clearly matched to any known species of Microbispora (Fig. 2); however, these Microbispora isolates were contiguous with Microbispora thermorosea (MTU48987), M. chromogenes (MCU48989), and M. diastatica (MDU48990), as illustrated in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Neighbor-joining tree showing the relationship between the 16S rRNA gene sequences from Microbispora sp. isolates and the closest genera and species deposited in the GenBank database. Bootstrap values of neighbor-joining analysis from 1,000 replications are shown on the branches. Scale bar represents the number of changes per nucleotide position (substitution/site).

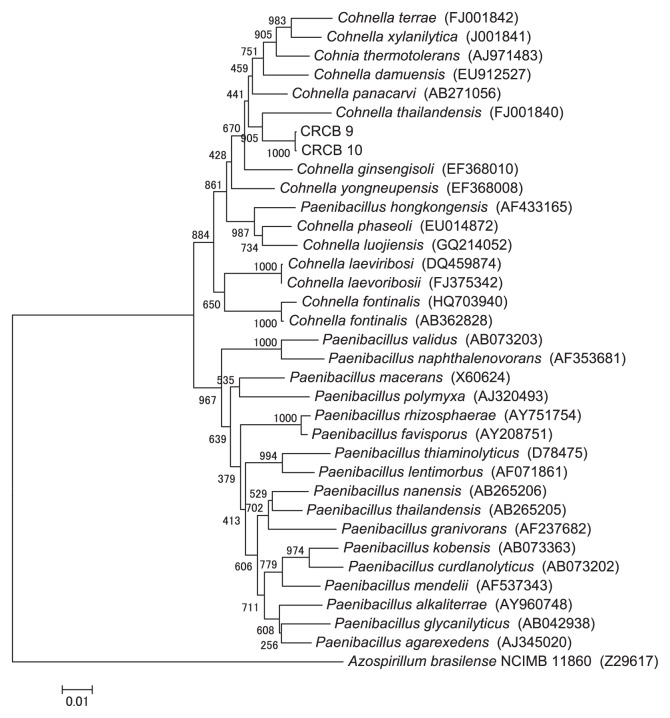

The CRC isolates CRCB9 and CRCB10 displayed comparatively low similarity (96%) to genus Cohnella, although the BLAST search indicated that these isolates also had similarity to Paenibacillus spp. More detailed phylogenetic analysis of the CRCB9 and CRCB10 16S rRNA gene sequences and of species of the genera Cohnella and Paenibacillus showed that both CRCB9 and CRCB10 were closer to the genus Cohnella than the genus Paenibacillus (Fig. 3). The top BLAST result showed that the closest species to CRCB9 and CRCB10 was Cohnella panacarvi (AB271056), while the constructed tree revealed that both isolates were closest to Cohnella thailandensis (FU001840).

Fig. 3.

Neighbor-joining tree showing the relationship between the 16S rRNA gene sequences from Cohnella sp. and the species of the genera Cohnella and Paenibacillus. Bootstrap values of neighbor-joining analysis from 1,000 replications are shown on the branches. Scale bar represents the number of changes per nucleotide position (substitution/site).

Characterization of SDC isolates

The three Streptomyces isolates showed cellulase, xylanase, β-glucanase, mannanase, and protease activities (Table 3). The isolate closest to S. fumigatiscleroticus (SDCB1) showed higher cellulase, β-glucanase, and mannanase activities than Streptomyces mexicanus (SDCB2 and SDCB6); however, the SDCB2 and SDCB6 isolates displayed higher xylanase and protease activities than the SDCB1 isolate.

Table 3.

Enzyme activities of cellulolytic bacteria isolated from SDC and CRC

| Genus | Isolate No. | Hydrolysis index | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| cellulase | xylanase | β-glucanase | mannanase | protease | ||

| Microbispora | SDCB3 | 4.2 ± 0.7 | 15.0 ± 4.0 | 12.9 ± 5.4 | 9.3 ± 1.3 | 11.8 ± 2.5 |

| SDCB4 | 4.9 ± 0.5 | 12.1 ± 4.0 | 8.1 ± 0.7 | 8.2 ± 1.3 | 9.9 ± 1.8 | |

| SDCB5 | 5.2 ± 1.1 | 17.2 ± 7.1 | 11.6 ± 2.7 | 9.8 ± 2.2 | 7.0 ± 2.0 | |

| SDCB7 | 5.1 ± 0.9 | 14.9 ± 4.5 | 11.6 ± 5.0 | 7.5 ± 1.2 | 5.9 ± 0.7 | |

| SDCB8 | 4.0 ± 1.1 | 28.4 ± 5.9 | 14.8 ± 1.9 | 13.4 ± 2.7 | 11.3 ± 1.7 | |

| SDCB9 | 7.7 ± 2.0 | 9.4 ± 0.9 | 10.0 ± 2.6 | 10.5 ± 1.2 | 4.9 ± 2.3 | |

|

| ||||||

| Streptomyces | SDCB1 | 3.9 ± 0.4 | 9.0 ± 0.6 | 9.4 ± 3.4 | 10.6 ± 2.3 | 3.5 ± 0.2 |

| SDCB2 | 2.7 ± 0.3 | 9.8 ± 1.4 | 7.0 ± 0.8 | 7.2 ± 0.6 | 4.4 ± 0.7 | |

| SDCB6 | 3.5 ± 0.7 | 9.7 ± 1.9 | 8.1 ± 2.3 | 7.0 ± 1.5 | 4.4 ± 0.3 | |

|

| ||||||

| Paenibacillus | SDCB10 | 4.1 ± 1.5 | 5.6 ± 1.6 | 23.7 ± 4.3 | 6.8 ± 0.9 | N.D. |

| SDCB11 | 5.0 ± 1.1 | 7.8 ± 1.4 | 16.3 ± 1.4 | 7.3 ± 1.2 | N.D. | |

|

| ||||||

| Microbispora | CRCB2 | 9.1 ± 2.9 | 9.8 ± 2.9 | 11.1 ± 1.6 | N.D. | 9.3 ± 1.4 |

| CRCB3 | 3.3 ± 0.5 | 11.3 ± 1.7 | 14.0 ± 3.7 | 9.1 ± 2.2 | 5.9 ± 1.2 | |

| CRCB4 | 4.4 ± 0.4 | 8.4 ± 1.0 | 8.3 ± 4.3 | 4.6 ± 0.5 | 6.1 ± 0.7 | |

| CRCB5 | 2.7 ± 0.4 | 7.7 ± 0.6 | 10.3 ± 2.5 | 11.5 ± 4.0 | 4.9 ± 1.0 | |

| CRCB6 | 2.5 ± 0.5 | 15.9 ± 2.2 | 14.4 ± 3.4 | 8.1 ± 2.0 | 5.3 ± 1.0 | |

| CRCB7 | 2.3 ± 0.1 | 9.9 ± 0.6 | 10.1 ± 1.5 | 11.2 ± 4.0 | 9.0 ± 2.2 | |

| CRCB8 | 3.9 ± 0.8 | 14.7 ± 0.8 | 10.8 ± 2.6 | 8.3 ± 1.5 | 7.3 ± 0.9 | |

|

| ||||||

| Streptomyces | CRCB1 | 3.1 ± 0.6 | 5.8 ± 1.1 | 4.7 ± 0.3 | N.D. | 2.7 ± 0.1 |

|

| ||||||

| Cohnella | CRCB9 | 6.1 ± 0.9 | 14.4 ± 0.6 | 9.8 ± 0.9 | 14.2 ± 2.8 | N.D. |

| CRCB10 | 6.1 ± 1.2 | 17.3 ± 3.3 | 6.5 ± 0.5 | 9.2 ± 0.3 | N.D. | |

Enzyme activities expressed as the Substrate Hydrolysis Index, which was calculated as the ratio of the average diameter (d) of the blue zone around the bacterial colony to the average diameter of the bacterial colony (D), expressed in millimeters with standard deviation in five enzyme assays using AZCL-HE-cellulose (cellulase), AZCL-arabinoxylan (xylanase), AZCL-barley β-glucan (β-glucanase), AZCL-galactomannan (mannanase) and AZCL-casein (protease). N.D.: not detected.

All six Microbispora isolates displayed activities in the five enzyme assays; however, the ability of the Microbispora isolates to degrade the various substrates varied among the different isolates. Notably, the Microbispora isolates showed high cellulase, xylanase, mannanase, and protease activities; isolate SDCB9 showed the highest cellulase activity, SDCB8 had the highest xylanase and mannanase activities, and SDCB3 exhibited the highest protease activity among the SDC isolates.

The two Paenibacillus isolates exhibited cellulase, xylanase, β-glucanase, and mannanase activities, but protease activity was not detected. The highest β-glucanase activity among the SDC isolates was displayed by the Paenibacillus isolates, particularly SDCB10. In addition, the Paenibacillus isolates exhibited relatively high cellulase and mannanase activities.

Characterization of CRC isolates

Streptomyces isolate CRCB1, which was phylogenetically close to S. fumigatiscleroticus, showed relatively low cellulase activity and the lowest xylanase, β-glucanase, and protease activities among the CRC isolates.

The Microbispora isolates, with the exception of CRCB2, showed degradative activity towards all of the AZCL substrates used for the enzyme assays. Although the CRCB2 isolate did not have the ability to degrade AZCL-galactomannan, it exhibited the highest cellulase activity. The CRCB6 isolate showed the highest xylanase and β-glucanase activities, while CRCB5 and CRCB2 exhibited the highest mannanase and protease activities, respectively, among the Microbispora isolates from CRC.

The two isolates closest to Cohnella sp. (CRCB9 and CRCB10) displayed the highest mannanase and xylanase activities among the CRC isolates, and relatively high cellulase activity among all compost isolates, although protease activity was not detected.

Discussion

In the present study, we investigated the cellulolytic and hemicellulolytic activities of bacteria isolated from SDC and CRC in an effort to elucidate their microbial capability to degrade lignocellulosic materials. In both SDC and CRC, Streptomyces spp. and Microbispora spp. were the dominant isolates. Our enzymatic analysis revealed that Microbispora sp. isolate SDCB8 displayed high xylanase and mannanase activities, and SDCB9 and SDC11 indicated the highest cellulase and β-glucanase activities, respectively, in SDC, while CRCB2, CRCB6, CRCB9, and CRCB10 showed the highest cellulase, β-glucanase, mannanase, and xylanase activities, respectively, in CRC.

The isolated genera from SDC consisted of Streptomyces (3 isolates), Microbispora (6 isolates), and Paenibacillus (2 isolates), while Streptomyces (1 isolate), Microbispora (7 isolates), and Cohnella (2 isolates) were isolated from CRC. The 16S rRNA phylogenetic analysis revealed that of the four Streptomyces isolates, one was a close relative of S. fumigatiscleroticus, which was present in both compost types, while a second SDC isolate was a close relative of S. mexicanus (Table 1 and Fig. 1). Our findings are consistent with those of Kleyn and Wetzler (27), who isolated several species of Streptomyces from spent mushroom compost. Adhikary et al.(1) also found that Streptomyces spp. were predominant at all stages of the composting of mushroom components, paddy straw, sugar cane bagasse, and water-hyacinth.

Although our analysis showed that many isolates from both compost types belonged to the genus Microbispora (54.6% and 70.0% of SDC and CRC isolates, respectively), El-Tarabily and Sivasithamparam (13) reported that the genus Microbispora represented only 0.18% of total actinomycetes isolated from soil. Although Waldron et al.(56) isolated Microbispora from several soil samples, streams, pools, and compost samples, there are no other reports of Microbispora inhabiting compost. The high population of Microbispora-related isolates identified in both compost types examined here suggests that these strains are well adapted to composting conditions.

Two SDC isolates were identified as members of the genus Paenibacillus and displayed 99.7% 16S rRNA sequence similarity to P. woosongensis. Paenibacillus spp. have also been isolated from municipal urban waste compost (54), poultry litter compost (53), cow feces (55), and spent mushroom compost (57). We also found that two CRC isolates showed similarity (approx. 96%) to Cohnella sp. The low similarity of these isolates to known species of the genus Cohnella suggests that they may represent new species. The classification of these isolates by other taxonomic methods, such as biochemical analysis, fatty acids analysis, DNA base composition, and DNA-DNA hybridization, is required to confirm this speculation; however, our present finding are supported by Rastogi et al.(38), who reported that Cohnella is one of the dominant cellulolytic bacterial genera isolated from compost samples.

The microbial enzymatic activities clearly varied among both the isolated genera and between related isolates. El-Refai et al.(12) also observed variations in bacterial and fungal enzyme activities among species of the same genus and even between different strains of the same species. Béra-Maillet et al.(3) revealed that cellulase and hemicellulase activities differed among strains of the genus Fibrobacter.

Among SDC bacteria isolates, the three Streptomyces isolates (SDCB1, SDCB3, and SDCB6) hydrolyzed AZCL-cellulose, -arabinoxylan, -β-glucan, -galactomannan, and -casein. Several species of Streptomyces are known to produce cellulase enzymes (9), and a number of Streptomyces strains have been reported to produce cellulase and xylanase (8). Grabski and Jeffries (17) demonstrated that Streptomyces sp. possess xylanase, and Théberge et al.(49) isolated and characterized endoglucanase from the culture filtrate of Streptomyces sp. Takahashi et al.(45) found that galactomannan was hydrolyzed by a purified extracellular mannanase from Streptomyces sp. Kansoh and Nagieb (23) reported that xylanase and mannanase were produced by Streptomyces sp. cultivated in a medium containing xylan from either sugar cane bagasse or galactomannan. Additionally, a strain of Streptomyces was shown to overproduce the extracellular protease against the substrate azocasein (16). Based on our present findings and those of previous studies, the isolates closest to Streptomyces may be important contributors to the degradation of the different components of organic materials during the composting process.

Microbispora isolates showed the highest cellulase activity (SDCB9), xylanase and mannanase activities (SDCB8), and protease activity (SDCB3) in SDC. Waldron et al.(56) demonstrated that Microbispora produces thermally stable extracellular cellulase in good yield, while the poor xylanase activity of Microbispora sp. isolated from cattle manure was reported by Holtz et al.(21). Here, all Microbispora isolates were able to degrade AZCL-β-glucan as a substrate for β-glucanase activity. In accordance with our results, Bartley et al.(2) detected and purified β-glucanase produced by Microbispora sp. Although our Microbispora sp. isolates showed high mannanase activity, to our knowledge, no previous reports have identified mannanase production by Microbispora sp. Furthermore, the Microbispora isolates showed higher protease activity than the other genera isolated from SDC, a finding that contrasts with that of Nawani et al.(34), who found that Microbispora sp. displayed very low protease activity. This discrepancy may be due to variations in the enzyme profiles of microbial isolates among different species of the same genus, as well as among different isolates of the same species.

Isolates SDCB10 and SDCB11 were closely related to P. woosongensis and showed cellulase, xylanase, mannanase, and the highest β-glucanase activities, although protease activity was not detected. Rivas et al.(39) also found that cellulases, xylanases, and β-galactosidase were actively produced by a Paenibacillus sp. isolated from the phyllosphere of Phoenix dactylifera, but caseinase was not produced. In addition, Shi et al.(41) reported the production of a novel bifunctional xylanase by Paenibacillus sp. with xylanase and glucanase activities, and Fu et al.(15) demonstrated the mannanase activity of Paenibacillus sp. Thus, isolates closest to Paenibacillus sp. may play a significant role in the degradation of cellulose, xylans, and mannans of SDC during the composting process.

With regard to the bacteria isolated from CRC, one isolate (CRCB1) showed 99.4% similarity to S. fumigatiscleroticus and possessed cellulase, xylanase, β-glucanase, and protease activities, but no detectable mannanase activity. Grabski and Jeffries (17) also demonstrated the production of cellulase and xylanase by S. fumigatiscleroticus. Malviya et al.(32) reported that a number of Streptomyces isolates produce cellulases and proteases, while Hong et al.(22) revealed that β-glucanase is produced by Streptomyces sp. Although Streptomyces isolates closely related to S. fumigatiscleroticus (SDCB1) from SDC revealed mannanase activity, CRCB1 (S. fumigatiscleroticus) could not degrade galactomannan. This finding may indicate that the enzyme profile of microorganisms is not only genus and species-specific, but also isolate-specific. This speculation is supported by the result of our previous study, in which we also found that the enzyme profiles of cellulolytic and hemicellulolytic fungi were isolate-specific (11).

As found in SDC, Microbispora sp. was the predominant genus detected in CRC. All Microbispora isolates displayed activities in all five of the enzyme assays with the exception of CRCB2, which showed the highest cellulase activity, but did not exhibit mannanase activity. Although cellulase (56), xylanase (21), β-glucanase (2), and protease activities (34) have been identified among Microbispora sp., there are no reports of mannanase activity by members of this genus, as described above. Although no previous studies concerning the role of Microbispora sp. in composting processes were found, the results of the present study suggest that this genus may play an important role in the biodegradation of organic material.

The isolates closely related to C. panacarvi (CRCB9 and CRCB10) displayed cellulase, xylanase, β-glucanase, and mannanase activities. Notably, CRCB9 and CRCB10 exhibited the highest mannanase and xylanase activities, respectively among the ten CRC isolates. Rastogi et al.(38) found that a Cohnella sp. was able to degrade cellulose, carboxymethyl cellulose (CMC), and sawdust. Xylanolytic activity of the genus Cohnella was also reported for several species, including C. panacarvi sp. (60), C. damensis sp. (59), and C. thailandensis sp. (26). In agreement with our results, Cho et al.(7) demonstrated that Cohnella sp. isolates were negative for protease activity; however, no previous reports concerning the β-glucanase and mannanase activities of any members of the genus Cohnella were found. CRCB9 and CRCB10 isolates may contribute to the effective degradation of xylans and mannans, and may also be important for the degradation of cellulose during the composting of CRC.

In this study, aerobic cellulolytic bacteria were isolated and their enzyme activities evaluated. Some anaerobic bacteria, such as Clostridium spp. are known to degrade cellulose and hemicellulose. Sizova et al.(42) isolated cellulose- and xylan-degrading anaerobic bacteria, Clostridium spp., from biocompost made from wood chips, horse manure, and food waste. Haruta et al.(18) constructed a microbial community with high cellulolytic ability by composting materials consisting of rice straw, sugar cane dregs, chicken and cattle feces, while Kato et al.(24) isolated a novel anaerobic bacterium, Clostridium straminisolvens, as a cellulolytic bacterium from their microbial community. Their study under aerobic conditions using a mixed culture composed of five bacteria strains, C. straminisolvens, Clostridium sp., Pseudoxanthomonas sp., Brevibacillus sp., Bordetella sp., which were isolated from their microbial community, demonstrated synergistic relationships between an anaerobic cellulolytic bacterium (C. straminisolvens) and aerobic bacteria such as Pseudoxanthomonas sp. and Brevibacillus sp. It was suggested that aerobes serve to create anaerobic conditions through their respiration activities, while anaerobic cellulolytic bacteria supply substrates such as acetate and glucose for aerobes (25). Anaerobic Clostridia bacteria were also detected in rice straw-composting materials and in aerated cattle manure composting piles by PCR-DGGE (4, 29). The coexistence of various types of bacteria including cellulolytic and hemicellulolytic anaerobes could be associated with composting processes. Isolation of both cellulose-degrading aerobic and anaerobic bacteria from composts and evaluation of their cellulolytic and hemicellulolytic enzyme activities, however, have not been reported.

In conclusion, all SDC and CRC isolates among the four identified genera likely cooperated in the degradation of celluloses, hemicelluloses, and proteins based on the observed enzyme profiles. Although no previous investigations have reported the role of Microbispora in the degradation of organic materials during composting, the present study suggests the importance of this genus in the composting process. The Microbispora isolates identified here may play a major role in the degradation process in both examined compost types. Our findings indicate that Microbispora (SDCB8 and SDCB9) and Paenibacillus isolates (SDCB10 and SDCB11) may contribute to effective biodegradation in SDC, whereas Microbispora (CRCB2 and CRCB6) and Cohnella isolates (CRCB9 and CRCB10) could be important for the enhancement of cellulose and hemicellulose bioconversion during the composting of CRC. To our knowledge, the present study is the first report to describe the production of mannanase enzymes by Microbispora sp. and to identify β-glucanase and mannanase activities within the genus Cohnella. This study examined only aerobic cellulose-degrading bacteria and their enzyme activities. Further study should be conducted to evaluate the contribution of anaerobic cellulose-degrading bacteria during composting.

Acknowledgements

We are extremely grateful to the Egyptian government for providing financial assistance to the first author.

References

- 1.Adhikary RK, Barua P, Bordoloi DN. Influence of microbial pretreatment on degradation of mushroom nutrient substrate. Int Biodeterior Biodegrad. 1992;30:233–241. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bartley TD, Murphy-Holland K, Eveleigh DE. A method for the detection and differentiation of cellulase components in polyacrylamide gels. Anal Biochem. 1984;140:157–161. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(84)90147-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Béra-Maillet C, Ribot Y, Forano E. Fiber-degrading systems of different strains of the genus Fibrobacter. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2004;70:2172–2179. doi: 10.1128/AEM.70.4.2172-2179.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cahyani VR, Matsuya K, Asakawa S, Kimura M. Succession and phylogenetic composition of bacterial communities responsible for the composting process of rice straw estimated by PCR-DGGE analysis. Soil Sci Plant Nutr. 2003;49:619–630. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen H, Li X.-L, Ljungdahl LG. Sequencing of a 1,3-1,4-β-D-glucanase (lichenase) from the anaerobic fungus Orpinomyces strain PC-2: Properties of the enzyme expressed in Escherichia coli and evidence that the gene has a bacterial origin. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:6028–6034. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.19.6028-6034.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chidthaisong A, Conrad R. Pattern of non-methanogenic and methanogenic degradation of cellulose in anoxic rice field soil. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 2000;31:87–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2000.tb00674.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cho E.-A, Lee J.-S, Lee KC, Jung H.-C, Pan J.-G, Pyun Y.-R. Cohnella laeviribosi sp. nov., isolated from a volcanic pond. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2007;57:2902–2907. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.64844-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coman G, Cotarlet M, Bahrim G, Stougaard P. Increasing the efficiency of screening Streptomycetes able to produce glucanases by using insoluble chromogenic substrates. Roum. Biotechnol. Lett. 2008;13(6) supplement:20–25. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Doi RH. Cellulases of mesophilic microorganisms: Cellulosome and noncellulosome producers. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2008;1125:267–279. doi: 10.1196/annals.1419.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dubos RJ. The decomposition of cellulose by aerobic bacteria. J Bacteriol. 1928;15:223–234. doi: 10.1128/jb.15.4.223-234.1928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eida MF, Nagaoka T, Wasaki J, Kouno K. Evaluation of cellulolytic and hemicellulolytic abilities of fungi isolated from coffee residue and sawdust composts. Microbes Environ. 2011;26:220–227. doi: 10.1264/jsme2.me10210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.El-Refai A.-M.H, Atalla MM, E1-Safty HA. Microbial formation of cellulase and proteins from some cellulosic residues. Agric Wastes. 1984;11:105–113. [Google Scholar]

- 13.El-Tarabily KA, Sivasithamparam K. Non-streptomycete actinomycetes as biocontrol agents of soil-borne fungal plant pathogens and as plant growth promoters. Soil Biol Biochem. 2006;38:1505–1520. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Faure D, Deschamps AM. The effect of bacterial inoculation on the initiation of composting of grape pulps. Bioresour Technol. 1991;37:235–238. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fu X, Huang X, Liu P, Lin L, Wu G, Li C, Feng C, Hong Y. Cloning and characterization of a novel mannanase from Paenibacillus sp. BME-14. J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2010;20:518–524. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gibb GD, Ordaz DE, Strohl WR. Overproduction of extracellular protease activity by Streptomyces C5-A13 in fed-batch fermentation. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 1989;31:119–124. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grabski AC, Jeffries TW. Production, purification, and characterization of β-(1–4)-endoxylanase of Streptomyces roseiscleroticus. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1991;57:987–992. doi: 10.1128/aem.57.4.987-992.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Haruta S, Cui Z, Huang Z, Li M, Ishii M, Igarashi Y. Construction of a stable microbial community with high cellulose-degradation ability. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2002;59:529–534. doi: 10.1007/s00253-002-1026-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Heck JX, Hertz PF, Ayub MAZ. Cellulase and xylanase production by isolated Amazon Bacillus strains using soybean industrial residue based solid-state cultivation. Braz J Microbiol. 2002;33:213–218. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Heuer H, Krsek M, Baker P, Smalla K, Wellington EMH. Analysis of actinomycete communities by specific amplification of genes encoding 16S rRNA and gel-electrophoretic separation in denaturing gradients. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:3233–3241. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.8.3233-3241.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Holtz C, Kaspari H, Klemme J.-H. Production and properties of xylanases from thermophilic actinomycetes. Antonie van Leeuwenhoek. 1991;59:1–7. doi: 10.1007/BF00582112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hong T.-Y, Cheng C.-W, Huang J.-W, Meng M. Isolation and biochemical characterization of an endo-1,3-β-glucanase from Streptomyces sioyaensis containing a C-terminal family 6 carbohydrate-binding module that binds to 1,3-β-glucan. Microbiology. 2002;148:1151–1159. doi: 10.1099/00221287-148-4-1151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kansoh AL, Nagieb ZA. Xylanase and Mannanase enzymes from Streptomyces galbus NR and their use in biobleaching of softwood kraft pulp. Antonie van Leeuwenhoek. 2004;85:103–114. doi: 10.1023/B:ANTO.0000020281.73208.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kato S, Haruta S, Cui ZJ, Ishii M, Yokota A, Igarashi Y. Clostridium straminisolvens sp. nov., a moderately thermophilic, aerotolerant and cellulolytic bacterium isolated from a cellulose-degrading bacterial community. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2004;54:2043–2047. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.63148-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kato S, Haruta S, Cui ZJ, Ishii M, Igarashi Y. Stable coexistence of five bacterial strains as a cellulose-degrading community. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2005;71:7099–7106. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.11.7099-7106.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Khianngam S, Tanasupawat S, Akaracharanya A, Kim KK, Lee KC, Lee J-S. Cohnella thailandensis sp. nov., a xylanolytic bacterium from Thai soil. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2010;60:2284–2287. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.015859-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kleyn JG, Wetzler TF. The microbiology of spent mushroom compost and its dust. Can J Microbiol. 1981;27:748–753. doi: 10.1139/m81-116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lane DJ. 16S/23S rRNA sequencing. In: Stackebrandt E, Goodfellow M, editors. Nucleic Acid Techniques in Bacterial Systematics. John Wiley and Sons; New York: 1991. pp. 115–175. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Maeda K, Hanajima D, Morioka R, Osada T. Characterization and spatial distribution of bacterial communities within passively aerated cattle manure composting piles. Bioresour Technol. 2010;101:9631–9637. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2010.07.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Maki M, Leung KT, Qin W. The prospects of cellulase-producing bacteria for the bioconversion of lignocellulosic biomass. Int J Biol Sci. 2009;5:500–516. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.5.500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Malherbe S, Cloete TE. Lignocellulose biodegradation: Fundamentals and applications. Rev Environ Sci Biotechnol. 2002;1:105–114. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Malviya N, Yadav AK, Yandigeri MS, Arora DK. Diversity of culturable Streptomycetes from wheat cropping system of fertile regions of Indo-Gangetic Plains, India. World J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2011;27:1593–1602. [Google Scholar]

- 33.McCarthy AJ, Williams ST. Actinomycetes as agents of biodegradation in the environment: a review. Gene. 1992;115:189–192. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(92)90558-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nawani NN, Prakash D, Kapadnis BP. Extraction, purification and characterization of an antioxidant from marine waste using protease and chitinase cocktail. World J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2010;26:1509–1517. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pauly M, Keegstra K. Cell-wall carbohydrates and their modification as a resource for biofuels. Plant J. 2008;54:559–568. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2008.03463.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pedersen M, Hollensted M, Lange L, Andersen B. Screening for cellulose and hemicellulose degrading enzymes from the fungal genus Ulocladium. Int Biodeterior Biodegrad. 2009;63:484–489. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pérez J, Muñoz-Dorado J, de la Rubia T, Martínez J. Biodegradation and biological treatments of cellulose, hemicellulose and lignin: an overview. Int Microbiol. 2002;5:53–63. doi: 10.1007/s10123-002-0062-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rastogi G, Bhalla A, Adhikari A, Bischoff KM, Hughes SR, Christopher LP, Sani RK. Characterization of thermostable cellulases produced by Bacillus and Geobacillus strains. Bioresour Technol. 2010;101:8798–8806. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2010.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rivas R, García-Fraile P, Mateos PF, Martínez-Molina E, Velázquez E. Paenibacillus cellulosilyticus sp. nov., a cellulolytic and xylanolytic bacterium isolated from the bract phyllosphere of Phoenix dactylifera. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2006;56:2777–2781. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.64480-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sánchez C. Lignocellulosic residues: Biodegradation and bioconversion by fungi. Biotechnol Adv. 2009;27:185–194. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2008.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shi P, Tian J, Yuan T, et al. Paenibacillus sp. strain E18 bifunctional xylanase—glucanase with a single catalytic domain. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2010;76:3620–3624. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00345-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sizova MV, Izquierdo JA, Panikov NS, Lynd LR. Cellulose-and xylan-degrading thermophilic anaerobic bacteria from biocompost. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2011;77:2282–2291. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01219-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sınağ A, Gülbay S, Uskan B, Güllü M. Comparative studies of intermediates produced from hydrothermal treatments of sawdust and cellulose. J. Supercrit Fluids. 2009;50:121–127. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sukumaran RK, Singhania RR, Pandey A. Microbial cellulases—Production, applications and challenges. J Sci Ind Res. 2005;64:832–844. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Takahashi R, Kusakabe I, Kusama S, Sakurai Y, Murakami K, Maekawa A, Suzuki T. Structures of glucomanno-oligosaccharides from the hydrolytic products of konjac glucomannan produced by a β-mannanase from Streptomyces sp. Agric Biol Chem. 1984;48:2943–2950. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tamura K, Dudley J, Nei M, Kumar S. MEGA4: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis (MEGA) software version 4.0. Mol Biol Evol. 2007;24:1596–1599. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msm092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Teather RM, Wood PJ. Use of Congo red-polysaccharide interactions in enumeration and characterization of cellulolytic bacteria from the bovine rumen. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1982;43:777–780. doi: 10.1128/aem.43.4.777-780.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ten LN, Im W.-T, Kim M.-K, Kang MS, Lee S.-T. Development of a plate technique for screening of polysaccharide-degrading microorganisms by using a mixture of insoluble chromogenic substrates. J. Microbiol Methods. 2004;56:375–382. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2003.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Théberge M, Lacaze P, Shareck F, Morosoli R, Kluepfel D. Purification and characterization of an endoglucanase from Streptomyces lividans 66 and DNA sequence of the gene. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1992;58:815–820. doi: 10.1128/aem.58.3.815-820.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Thompson JD, Gibson TJ, Plewniak F, Jeanmougin F, Higgins DG. The Clustal_X windows interface: flexible strategies for multiple sequence alignment aided by quality analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;24:4876–4882. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.24.4876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tuomela M, Vikman M, Hatakka A, Itävaara M. Biodegradation of lignin in a compost environment: a review. Bioresour Technol. 2000;72:169–183. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Turner S, Pryer KM, Miao VPW, Palmer JD. Investigating deep phylogenetic relationships among cyanobacteria and plastids by small subunit rRNA sequence analysis. J Eukaryot Microbiol. 1999;46:327–338. doi: 10.1111/j.1550-7408.1999.tb04612.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Vaz-Moreira I, Faria C, Nobre MF, Schumann P, Nunes OC, Manaia CM. Paenibacillus humicus, sp. nov., isolated from poultry litter compost. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2007;57:2267–2271. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.65124-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Vaz-Moreira I, Figueira V, Lopes AR, Pukall R, Spröer C, Schumann P, Nunes OC, Manaia CM. Paenibacillus residui sp. nov., isolated from urban waste compost. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2010;60:2415–2419. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.014290-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Velázquez E, de Miguel T, Poza M, Rivas R, Rosselló-Mora R, Villa TG. Paenibacillus favisporus sp. nov., a xylanolytic bacterium isolated from cow faeces. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2004;54:59–64. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.02709-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Waldron CR, Becker-Vallone CA, Eveleigh DE. Isolation and characterization of a cellulolytic actinomycetes Microbispora bispora. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 1986;24:477–486. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Watabe M, Rao JR, Xu J, Millar BC, Ward RF, Moore JE. Identification of novel eubacteria from spent mushroom compost (SMC) waste by DNA sequence typing: ecological considerations of disposal on agricultural land. Waste Manage. 2004;24:81–86. doi: 10.1016/j.wasman.2003.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wen Z, Liao W, Chen S. Production of cellulase/β-glucosidase by the mixed fungi culture Trichoderma reesei and Aspergillus phoenicis on dairy manure. Process Biochem. 2005;40:3087–3094. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Xuesong L, Wang Z, Dai J, Zhang L, Fang C. Cohnella damensis sp. nov., a motile xylanolytic bacteria isolated from a low altitude area in Tibet. J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2010;20:410–414. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yoon M.-H, Ten LN, Im W-T. Cohnella panacarvi sp. nov., a xylanolytic bacterium isolated from ginseng cultivating soil. J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2007;17:913–918. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zhang Z, Schwartz S, Wagner L, Miller W. A greedy algorithm for aligning DNA sequences. J Comput Biol. 2000;7:203–214. doi: 10.1089/10665270050081478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]