Abstract

Objectives

We examined stereotyping of chronic pain sufferers among women aged 18 – 40 years and determined whether perceived stereotyping affects seeking care for women with chronic vulvar pain.

Design

Cross-sectional study using a community-based survey of vulvodynia asking if “Doctors think that people with chronic pain exaggerate their pain”, and if “People believe that vulvar pain is used as an excuse to avoid having sex”.

Setting and Participants

12,834 women aged 18 – 40 years in metropolitan Minneapolis/St. Paul, Minnesota. Paul, Minnesota.

Outcome Measures

Women were considered to have a history of chronic vulvar pain if they reported vulvar burning lasting more than 3 months or vulvar pain on contact.

Results

4,987 (38.9%) women reported a chronic pain condition; 1,651 had chronic vulvar pain. Women experiencing chronic pain were more likely than those without to perceive stereotyping from both doctors and others; a dose-response with the number of pain conditions existed. Women with chronic vulvar pain were more likely to believe that people think vulvar pain is an excuse to avoid intercourse. Half of the women with chronic vulvar pain did not seek medical care for it; of these, 40.4% perceived stereotyping from doctors. However, it was women who actually sought care (45.1%) who were more likely to feel stigmatized by doctors (adj. relative risk=1.11, 95% CI: 1.01-1.23).

Conclusions

Perceived negative stereotyping among chronic pain sufferers is common, particularly negative perceptions about physicians. In fact, chronic vulvar pain sufferers who felt stigmatized were more likely to have sought care than those who didn't feel stigmatized.

Keywords: Vulvodynia, stigma, stereotype, chronic pain, seeking care

Approximately 10% - 18% of American women have had symptoms consistent with vulvodynia at some point in their lives1-4. Among the estimated 116 million American chronic pain sufferers, women with vulvodynia play a significant role in the chronic pain epidemic due to their high rate of co-morbidity5-8, the subsequent psychosocial impact of this condition9-12, population-level economic costs13, the risk of reproductive consequences14,15, and the young age at which peak incidence of vulvodynia occurs16,17. The goal of medical intervention for vulvodynia is to reduce or eliminate pain, and in fact, remission from vulvar pain is thought to occur for some women18. However, unsuccessful treatment of vulvodynia, leading to prolonged pain, can profoundly affect a woman's sexual functioning19,20. Whereas successful intervention, which is often multidisciplinary, can lead to not only overall pain reduction but also nearly pain-free intercourse21, decreased depression and anxiety22, and improved psychological well-being23.

Medical management of vulvodynia has only been moderately effective so it is unclear to what extent medical care influences resolution of symptoms for women with vulvodynia. 24-29. In addition, examining the role of medical therapy on remission among all women with vulvodynia may far overestimate its true effect because in reality only roughly half of women with vulvar pain seek medical care1,4.

Reasons women choose not to seek medical care for their vulvar pain have not been elucidated. However, some studies have found that women with vulvodynia are apprehensive to speak about their pain with others9, and feelings of isolation and invalidation of their pain are common8. Although no previous studies regarding failure to seek medical care have been conducted among women with vulvodynia, studies of other chronic pain syndromes have identified that stigma, whether perceived, inadvertent, or real, contributes to estrangement from health care providers, particularly physicians30-32.

Sampling from a large administrative healthcare system database that represents young women from the surrounding geographical area, we conducted a study that estimates the prevalence of perceived stereotyping, which may ultimately lead to stigma, regarding vulvar pain sufferers. We then determined whether perceived stigma was associated with the high level of failure to seek care among women with chronic vulvar pain.

METHODS

Study Population and Sample

Data for this study were collected as part of an ongoing study to screen women for the presence of vulvar pain conducted in the metropolitan area of Minneapolis/St. Paul, Minnesota. Participants included randomly-selected women aged 18 to 40 years who had been seen for any reason at any of the Twin Cities Metro area Fairview Health Services Clinics within the previous two years and listed a home address within a 70-mile radius of the University of Minnesota Twin Cities campus.

A total of 25,754 women were identified as eligible for the study, in which women were mailed a self-administered survey that screened for history, length and current chronic vulvar pain. In addition, basic demographic, reproductive, pain histories, and perceived stigma regarding pain were surveyed. Women were given the option of completing the survey in one of three ways: via the enclosed hard copy survey with a prepaid return envelope, a secure online site, or over the telephone with trained interviewers. The survey response rate was 13,740/25,754 (53.4%). Of these women, 298 were not included into the final dataset because they did not respond to the primary questions on perceived stigma; another 359 did not report on the outcome of vulvar pain or the covariates necessary for the multivariable analysis (age, education, marital status, race or obesity); and a final 249 incompletely answered questions regarding other types of pain necessary for the multiple pain analyses. Thus, our final dataset included 12,834 women. This study was approved by the University of Minnesota Institutional Review Board.

Measures

Chronic vulvar pain consistent with a vulvodynia diagnosis was defined as having experienced burning in the vulvar area or excessive vulvar pain on contact that limited or prevented intercourse. Women were asked “Did you ever experience excessive vulvar pain on contact or touching” and “Did you ever experience burning in your vulvar area that persisted for 3 months or longer?”. Women were categorized as having chronic vulvar pain if they reported feeling excessive pain or burning. This categorization was made regardless of the woman's report of the presence of absence of vulvar itching. Population-based screeners such as this have been used with high specificity to identify women with symptoms characteristic of vulvodynia.33

Due to the fact that most all of the literature to support feelings of perceived stigma and chronic pain have been conducted among individuals with syndromic conditions, our analyses stratified chronic pain conditions into syndromic pain conditions or non-syndromic pain conditions to capture potential differences in response between the two categories. Syndromic pain conditions were defined as: chronic fatigue syndrome, irritable bowel syndrome, interstitial cystitis, and fibromyalgia. Non-syndromic pain conditions were considered to be: endometriosis, migraine headaches, polycystic ovaries, fibroids, and pelvic inflammatory disease.

Women were asked to answer the following two questions on a 5-point Likert scale: 1) Doctors think that people with chronic pain exaggerate their pain (termed “doctor’s opinions”; and 2) People believe that genital pain is used as an excuse to avoid having sex (termed “people’s opinions”). For analysis, results were then dichotomized into agree (defined as reporting “Strongly Agree” or “Agree”) or not (defined as reporting “Neutral”, “Disagree” or “Strongly disagree”). The first question was taken from the Chronic Pain Stigma Scale, while the second was slightly modified from the original Scale question, “People think that chronic pain is used as an excuse to get pain medication”34.

Analysis

Means and proportions were used to describe the distribution of characteristics in this population. We examined three dichotomous outcomes (doctor's opinions, people's opinions, and whether women with chronic vulvar pain symptoms sought medical care for their pain). Separate binomial regression models were fit for each of the three outcomes. Generalized linear models with log link and binomial family allowed estimation of the relative risks. The main exposure in each model was pain type classified into 7 categories (vulvar pain only, vulvar pain plus a pain syndrome, vulvar pain plus non-syndromic pain, syndromic pain only, non-syndromic pain only, syndromic pain plus non-syndromic pain, and all three types of pain), with women with no type of chronic pain as the reference.

In each analysis, we accounted for factors that may confound the association between having chronic vulvar pain and perception of stigma. Women's age (5 categories), educational status (at least college educated or not), marital status (currently married or not), race (White or not), and obesity (current BMI ≥ 30 or not) were identified from previous literature and considered confounders in each model. Analyses were performed using STATA v.12 (College Station, TX).

RESULTS

Our overall sample included 12,834 women, of which 85.7% were White, 59.2% held at least a college degree, 56.9% were married and 55.0% were of normal weight. (Table 1) Nearly 40% of women had some type of chronic pain. 1,651 of the 12,834 (12.86%) women reported a history of chronic vulvar pain. Among these, 7.5% had vulvar pain only, 3.5% for vulvar pain with a non-syndromic pain syndrome, 0.9% for vulvar pain and an additional syndromic pain syndrome, and1.1% had all three types of pain.

Table 1.

Demographic and medical characteristics of women enrolled in the Fairview Health System who returned a survey on women's health, 2010 – 2011.

| Total N=12,834 | |

|---|---|

| n (%) | |

| Race | |

| White | 10,994 (85.7) |

| Black | 441 (3.4) |

| Biracial | 613 (4.8) |

| Other | 786 (6.1) |

| Age Categories (y) | |

| 18 – 20 | 649 (5.1) |

| 21 – 25 | 2,090 (16.3) |

| 26 – 30 | 3,577 (27.9) |

| 31 – 35 | 3,678 (28.7) |

| ≥ 36 | 2,840 (22.1) |

| Level of Education | |

| Less than High School | 140 (1.1) |

| High School/GED | 1,056 (8.2) |

| Some College or Technical School | 2,506 (19.5) |

| Associate's Degree | 1,533 (11.9) |

| Bachelor's Degree | 5,079 (39.6) |

| Graduate Degree | 2,520 (19.6) |

| Marital Status | |

| Single, never married | 4,841 (37.7) |

| Married/Partnered | 7,308 (56.9) |

| Separated/Divorced | 672 (5.2) |

| Widowed | 13 (0.1) |

| Weight Status | |

| Underweight, BMI <18.5 | 343 (2.7) |

| Normal, BMI 18.5 – 24.9 | 7,057 (55.0) |

| Overweight, BMI 25 – 29.9 | 2,989 (23.3) |

| Obese, BMI ≥ 30 | 2,445 (19.1) |

| Pain Status | |

| No Pain | 7,847 (61.4) |

| Any Pain | 4,987 (38.6) |

| Non-Syndromic Pain* Only | 2,460 (19.2) |

| Syndromic Pain** Only | 473 (3.7) |

| Syndromic Pain + Non-Syndromic Pain | 376 (2.9) |

| Vulvar Pain Only | 959 (7.5) |

| Vulvar Pain + Non-Syndromic Pain | 443 (3.5) |

| Vulvar Pain + Syndromic Pain | 112 (0.9) |

| All 3 Pain Types | 137 (1.1) |

Non-syndrome pain include: endometriosis, migraine headache, polycystic ovaries, fibroids, pelvic inflammatory disease.

Syndromic pain conditions include: chronic fatigue syndrome, irritable bowel syndrome, interstitial cystitis, fibromyalgia.

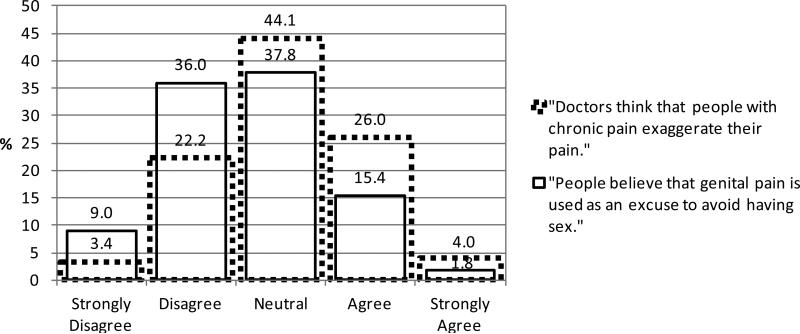

Thirty percent of women in the general population sample agreed (26% agreed plus 4% agreed strongly) with the statement regarding doctors believe pain is exaggerated among chronic pain suffers. (Figure) While 17.2% of the sample agreed that people in general believe that vulvar pain is used as an excuse to avoid having sex. (Figure)

Figure.

Prevalence of opinions regarding a.) doctors and their perceptions about chronic pain sufferers; and b.) people and their perceptions of genital pain being used as an excuse to avoid sex among 12,834 women in the Minneapolis/St. Paul metropolitan area, 2010 – 2012.

Table 2 shows the results of the binary regression models examining responses congruent with the belief that doctors hold stereotypes of individuals with chronic pain (left) and regression models congruent with the belief that people think vulvar pain is used as an excuse to avoid sex (right). In the presence of any type of pain, whether it was syndromic, non-syndromic or vulvar pain, women were significantly more likely to agree with the stigmatizing statements (adj. RR about doctors=1.44, 95% CI: 1.36 – 1.52; adj. RR about other people=1.58, 95% CI: 1.46 – 1.70). Women with chronic vulvar pain alone were 37% more likely (95% CI: 1.25-1.51) than women without any pain to believe that doctors hold this negative stereotype of pain sufferers.

Table 2.

Models of the prevalence and adjusted risk ratios and 95% confidence intervals by pain category for endorsement of two questions regarding perceived stereotyping by physicians (left) and people in general (right).

| Believe doctors think people with chronic pain exaggerate their pain | Believe people think vulvar pain is an excuse to avoid sex | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | No | Yes | |||||||||

| N (%) | N (%) | Adj. RR | 95% CI | Adj. RR | 95% CI | N (%) | N (%) | Adj. RR | 95% CI | Adj. RR | 95% CI | |

| Model 1 | ||||||||||||

| No Pain | 5876(74.6) | 1998 (25.4) | 1.0 | REF | -- | -- | 6781 (86.1) | 1093 (13.9) | 1.0 | REF | -- | -- |

| Any Pain | 3100 (62.5) | 1860 (37.5) | 1.44 | 1.36 – 1.52 | -- | -- | 3842 (77.5) | 1116 (22.5) | 1.58 | 1.46 – 1.70 | -- | -- |

| Model 2 | ||||||||||||

| No Pain | 5876 (74.6) | 1998 (25.4) | 1.0 | REF | -- | -- | 6781 (86.1) | 1093 (13.9) | 1.0 | REF | -- | -- |

| Non-Syndromic Pain Only | 1636 (66.5) | 824 (33.5) | 1.28 | 1.19 – 1.37 | 1.0 | REF | 2051 (83.4) | 408 (16.6) | 1.15 | 1.04 – 1.28 | 1.0 | REF |

| Syndromic Pain Only | 310 (65.5) | 163 (34.5) | 1.34 | 1.18 – 1.53 | 1.06 | 0.92 – 1.21 | 390 (82.5) | 83 (17.5) | 1.25 | 1.02 – 1.53 | 1.07 | 0.86 – 1.33 |

| Syndromic + Non-Syndromic Pain | 205 (54.5) | 171 (45.5) | 1.69 | 1.50 – 1.91 | 1.34 | 1.18 – 1.52 | 276 73.6) | 99 (26.4) | 1.80 | 1.51 – 2.16 | 1.57 | 1.30 – 1.90 |

| Vulvar Pain Only | 628 (65.5) | 331 (34.5) | 1.37 | 1.25 – 1.51 | 1.06 | 0.96 – 1.18 | 701 (73.1) | 258 (26.9) | 1.94 | 1.72 – 2.18 | 1.69 | 1.47 – 1.94 |

| Vulvar Pain + Non-Syndromic Pain | 207 (46.7) | 236 (53.3) | 2.04 | 1.85 – 2.24 | 1.59 | 1.44 – 1.76 | 272 (61.4) | 171 (38.6) | 2.69 | 2.36 – 3.06 | 2.34 | 2.02 – 2.71 |

| Vulvar Pain + Pain Syndrome | 56 (50) | 56 (50) | 1.95 | 1.62 – 2.35 | 1.52 | 1.26 – 1.84 | 69 (61.6) | 43 (38.4) | 2.67 | 2.10 – 3.41 | 2.35 | 1.83 – 3.02 |

| All Three | 58 (42.3) | 79 (57.7) | 2.16 | 1.87 – 2.50 | 1.69 | 1.46 – 1.97 | 83 (60.6) | 54 (39.4) | 2.62 | 2.11 – 3.26 | 2.28 | 1.82 – 2.87 |

Models adjusted for age, level of education, race, and obesity status.

*Non-syndrome pain include: endometriosis, migraine headache, polycystic ovaries, fibroids, pelvic inflammatory disease.

**Syndromic pain conditions include: chronic fatigue syndrome, irritable bowel syndrome, interstitial cystitis, fibromyalgia.

Our data indicate that the number of pain conditions may affect the association, with those having all three types of pain conditions exhibiting more than a two-fold increased risk of believing this about doctors compared to those with no pain (adj. RR=2.16, 95% CI: 1.87-2.50), which was higher than women with only one or two types of pain. (Table 2)

Although there was some evidence to suggest that women with other chronic pain conditions endorsed the notion of stereotyping against those with vulvar pain as it related to sexual intercourse, it was the women with chronic vulvar pain, especially those with additional pain types, who had the highest level of endorsement (adj. RRs=1.69 - 2.28). (Table 2)

50.1% of all of women with chronic vulvar pain reported seeking care for their vulvar pain or burning (Table 3). Among the 1,651 women who reported a history of chronic vulvar pain consistent with vulvodynia regardless of co-morbidity, we assessed the extent to which their choice to seek care for their pain may have been influenced by their perception of doctor's and other people's beliefs regarding their pain. (Table 3) Women who believed doctors held stereotypes against pain sufferers were 11% more likely to have sought care (adj. RR=1.11, 95% CI: 1.01-1.23) relative to those who did not endorse this stereotype. No association was observed between seeking care and endorsing the stereotype that vulvar pain is an excuse to avoid sex.

Table 3.

Among women with a history consistent of vulvodynia, the extent to which their decision to seek or not seek care was associated with their perception of doctor's and other people's beliefs that their pain was either exaggerated or used as an excuse to avoid having sex.

| Sought Care for Vulvar Pain | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Did not seek care N (%) | Sought care for pain N (%) | Adj. RR | 95% CI | |

| All Women | 802 (49.9) | 805 (50.1) | -- | -- |

| Believe Doctors think Women Exaggerate their Pain | ||||

| No | 478 (52.0) | 442 (48.0) | 1.0 | REF |

| Yes | 324 (47.2) | 363 (52.8) | 1.11 | 1.01 – 1.23 |

| Believe Genital Pain is an Excuse to Avoid Sex | ||||

| No | 547 (50.2) | 542 (49.8) | 1.0 | REF |

| Yes | 255 (49.2) | 263 (50.8) | 1.03 | 0.93 – 1.14 |

*Models adjusted for age, education, marital status, race, and obesity status.

DISCUSSION

Our study determined the prevalence of stigmatizing opinions regarding chronic pain among women in the general population. We found that 30% of women in the sample population agree that doctors have an unfavorable perception that individuals with chronic pain exaggerate their pain level. As expected, this opinion was more highly endorsed by individuals who themselves have chronic pain. However unexpectedly, we found that contrary to our original hypothesis, our data does not indicate that it is the fear of physician stereotyping that kept women with chronic vulvar pain from seeking care. In fact, we found that endorsement of physician stereotyping was significantly higher among those women who sought care.

Approximately half of our study sample who experienced chronic vulvar pain sought medical care. This is consistent with two previous studies that found between 48 – 60% of women sought treatment1,4. Given that it has been greater than 10 years since Harlow and Stewart collected their data, it suggests that attempts to increase public awareness for increased screening of this condition have not yet been successful.

We had hypothesized that women with chronic pain who felt that they were being stereotyped for their pain would be less likely to seek medical care. But in fact, we found that it was actually women who felt stigmatized were more likely to have sought care than those who did not feel stigmatized. This was contrary to what we had hypothesized and may be a result of reverse causality. Women who sought care may not have found adequate support from their clinicians; it has been reported that the majority of women with vulvodynia sought care from 3 or more physicians prior to their diagnosis1.

We failed to observe any association between perceived stereotyping from other people and seeking medical care. Several factors could contribute to this finding. First, women may differentiate between stereotyping by the general population and those in the medical profession, perhaps holding more regard to physicians on this topic. Secondly, previous studies have found that women are more likely to speak of their vulvar pain when the level of pain is greater9. If this is true, women may seek care despite public perception simply because their pain and discomfort have been too great to bear any longer without speaking to a physician.

When we compared our findings for women with chronic vulvar pain to other types of chronic pain (other pain syndromes and pain conditions that are associated with less stigma), we found similar results for endorsing these two stereotyping opinions. Expectedly, when investigating the question more specific to vulvodynia, whether vulvar pain was used as an excuse to avoid sex, the magnitude of the association was greater for women with chronic vulvar pain compared to those with other pain conditions.

Our results represent responses from a recent community-based survey of over 12,000 women, and are the first to address the issue of whether perceived pain stereotyping is associated with failure to seek care for women with chronic pain. Our findings are not free of limitations and should be viewed with these in mind. First, our questions on perceived stereotyping have not been previously validated for use with vulvar pain. However, there were only slight modifications of the question to address vulvar pain. Secondly, there was no clinical diagnosis of pain conditions. However, self-report of chronic vulvar pain in a survey has found to have high validity33,35.

In conclusion, a history of chronic vulvar pain in this population of relatively young women was common. Similar to previous reports, half of the women with chronic vulvar pain consistent with a diagnosis of vulvodynia did not seek medical care for their pain. However, our evidence does not suggest that perception of stereotyping from physicians or other people were barriers to seeking care. In fact, we observed that women who sought care were more likely to have a poor perception of physicians’ stereotyping opinions. Our findings suggest that other causes influencing the failure to seek care for chronic vulvar pain should be investigated. In addition, future research should determine the validity of physician stigma and stereotyping of women with chronic vulvar pain in attempts to develop successful interactions between pain suffers and their physicians.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study was supported by NIH/NICHD R01-HD058608 (PI: Harlow). The results of this study were presented in part at the 3rd North American Congress of Epidemiology, Montreal, Canada, June 21 – 24, 2011.

REFERENCES

- 1.Harlow BL, Stewart EG. A population-based assessment of chronic unexplained vulvar pain: have we underestimated the prevalence of vulvodynia? J Am Med Womens Assoc. 2003;58:82–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arnold LD, Bachmann GA, Rosen R, Rhoads GG. Assessment of vulvodynia symptoms in a sample of US women: a prevalence survey with a nested case control study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;196:128, e1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2006.07.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bachmann GA, Rosen R, Pinn VW, et al. Vulvodynia: a state-of-the-art consensus on definitions, diagnosis and management. J Reprod Med. 2006;51:447–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reed BD, Harlow SD, Sen A, et al. Prevalence and demographic characteristics of vulvodynia in a population-based sample. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;206:170, e1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2011.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arnold LD, Bachmann GA, Rosen R, Kelly S, Rhoads GG. Vulvodynia: characteristics and associations with comorbidities and quality of life. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;107:617–24. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000199951.26822.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rodriguez MA, Afari N, Buchwald DS. Evidence for overlap between urological and nonurological unexplained clinical conditions. J Urol. 2009;182:2123–31. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2009.07.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reed BD, Harlow SD, Sen A, Edwards RM, Chen D, Haefner HK. Relationship between vulvodynia and chronic comorbid pain conditions. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;120:145–51. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31825957cf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nguyen RH, Ecklund AM, Maclehose RF, Veasley C, Harlow BL. Co-morbid pain conditions and feelings of invalidation and isolation among women with vulvodynia. Psychol Health Med. 2012;17:589–98. doi: 10.1080/13548506.2011.647703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nguyen RH, MacLehose RF, Veasley C, Turner RM, Harlow BL, Horvath KJ. Comfort in discussing vulvar pain in social relationships among women with vulvodynia. J Reprod Med. 2012;57:109–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reed BD, Haefner HK, Punch MR, Roth RS, Gorenflo DW, Gillespie BW. Psychosocial and sexual functioning in women with vulvodynia and chronic pelvic pain. A comparative evaluation. J Reprod Med. 2000;45:624–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jelovsek JE, Walters MD, Barber MD. Psychosocial impact of chronic vulvovagina conditions. J Reprod Med. 2008;53:75–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ayling K, Ussher JM. “If sex hurts, am I still a woman?” the subjective experience of vulvodynia in hetero-sexual women. Arch Sex Behav. 2008;37:294–304. doi: 10.1007/s10508-007-9204-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xie Y, Shi L, Xiong X, Wu E, Veasley C, Dade C. Economic burden and quality of life of vulvodynia in the United States. Curr Med Res Opin. 2012;28:601–8. doi: 10.1185/03007995.2012.666963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reed BD, Haefner HK, Cantor L. Vulvar dysesthesia (vulvodynia). A follow-up study. J Reprod Med. 2003;48:409–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nguyen RH, Stewart EG, Harlow BL. A population-based study of pregnancy and delivery characteristics among women with vulvodynia. Pain Therapy. 2012:1. doi: 10.1007/s40122-012-0002-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Clare CA, Yeh J. Vulvodynia in adolescence: childhood vulvar pain syndromes. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2011;24:110–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2010.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reed BD, Cantor LE. Vulvodynia in preadolescent girls. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2008;12:257–61. doi: 10.1097/LGT.0b013e318168e73d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reed BD, Haefner HK, Edwards L. A survey on diagnosis and treatment of vulvodynia among vulvodynia researchers and members of the International Society for the Study of Vulvovaginal Disease. J Reprod Med. 2008;53:921–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gardella B, Porru D, Nappi RE, Dacco MD, Chiesa A, Spinillo A. Interstitial cystitis is associated with vulvodynia and sexual dysfunction--a case-control study. J Sex Med. 2011;8:1726–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2011.02251.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Smith KB, Pukall CF. A systematic review of relationship adjustment and sexual satisfaction among women with provoked vestibulodynia. J Sex Res. 2011;48:166–91. doi: 10.1080/00224499.2011.555016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Farajun Y, Zarfati D, Abramov L, Livoff A, Bornstein J. Enoxaparin treatment for vulvodynia: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;120:565–72. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3182657de6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brotto LA, Sadownik L, Thomson S. Impact of educational seminars on women with provoked vestibulodynia. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2010;32:132–8. doi: 10.1016/S1701-2163(16)34427-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sadownik LA, Seal BN, Brotto LA. Provoked vestibulodynia-women's experience of participating in a multidisciplinary vulvodynia program. J Sex Med. 2012;9:1086–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2011.02641.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tribo MJ, Andion O, Ros S, et al. Clinical characteristics and psychopathological profile of patients with vulvodynia: an observational and descriptive study. Dermatology. 2008;216:24–30. doi: 10.1159/000109354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Petersen CD, Giraldi A, Lundvall L, Kristensen E. Botulinum toxin type A-a novel treatment for provoked vestibulodynia? Results from a randomized, placebo controlled, double blinded study. J Sex Med. 2009;6:2523–37. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2009.01378.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Foster DC, Kotok MB, Huang LS, et al. Oral desipramine and topical lidocaine for vulvodynia: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116:583–93. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181e9e0ab. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Andrews JC. Vulvodynia interventions--systematic review and evidence grading. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2011;66:299–315. doi: 10.1097/OGX.0b013e3182277fb7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nguyen RH. Sexual medicine: When good isn't good enough-treatment for vulvodynia. Nat Rev Urol. 2012 doi: 10.1038/nrurol.2012.145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brown CS, Wan J, Bachmann G, Rosen R. Self-management, amitriptyline, and amitripyline plus triamcinolone in the management of vulvodynia. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2009;18:163–9. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2007.0676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cohen M, Quintner J, Buchanan D, Nielsen M, Guy L. Stigmatization of patients with chronic pain: the extinction of empathy. Pain Med. 2011;12:1637–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2011.01264.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Marbach JJ, Lennon MC, Link BG, Dohrenwend BP. Losing face: sources of stigma as perceived by chronic facial pain patients. J Behav Med. 1990;13:583–604. doi: 10.1007/BF00844736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Drossman DA, Chang L, Schneck S, Blackman C, Norton WF, Norton NJ. A focus group assessment of patient perspectives on irritable bowel syndrome and illness severity. Dig Dis Sci. 2009;54:1532–41. doi: 10.1007/s10620-009-0792-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Harlow BL, Vazquez G, MacLehose RF, Erickson DJ, Oakes JM, Duval SJ. Self-reported vulvar pain characteristics and their association with clinically confirmed vestibulodynia. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2009;18:1333–40. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2008.1032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Reed P. Chronic pain stigma: Development of the Chronic Pain Stigma Scale. San Francisco, CA: Alliant International University, San Francisco. 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Reed BD, Haefner HK, Harlow SD, Gorenflo DW, Sen A. Reliability and validity of self- reported symptoms for predicting vulvodynia. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108:906–13. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000237102.70485.5d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]