Abstract

Objective

To assess if it is better to intensively treat all early RA patients with drug combinations or reserve this for those who do not appropriately respond to methotrexate monotherapy and assess if the combination therapy of methotrexate plus etanercept is superior to the combination of methotrexate plus sulfasalazine plus hydroxychloroquine.

Methods

The TEAR study is a 2-year, randomized, double-blind trial. Using a 2×2 factorial design, participants were randomized to one of four treatment arms: immediate combination therapy of methotrexate plus etanercept; or oral triple therapy (methotrexate plus sulfasalazine plus hydroxychloroquine); or initial methotrexate monotherapy with a step-up to one of the combination therapies (all arms included matching placebos). The primary outcome was an observed-group analysis of DAS28-ESR scores from weeks 48 to 102.

Results

At the week 24 step-up period, those receiving immediate combination therapy (etanercept plus methotrexate; or triple therapy) demonstrated greater reduction in DAS28-ESR compared to those on initial methotrexate monotherapy (DAS28-ESR: 3.6 vs. 4.6, p<0.0001), with no differences between regimens of combination therapy. For weeks 48 through 102, participants randomized to step-up arms had a DAS28-ESR clinical response that was not different than those who received initial combination therapy, regardless of the treatment arm (3.2 vs. 3.2, p=0.75). There was no significant difference in DAS28-ESR between participants receiving oral triple therapy versus combination methotrexate plus etanercept (3.1 vs. 3.2, p=0.42). By week 102, there was a small, statistically significant difference in change in radiographic measurements from baseline between methotrexate plus etanercept compared to oral triple therapy (0.64 vs. 1.69, p= 0.047). The absolute difference at week 102 was small.

Conclusions

There were no differences in the mean DAS28-ESR during weeks 48-102 between participants randomized to methotrexate plus etanercept or triple therapy, regardless of whether they received immediate combination treatment or step-up from methotrexate monotherapy. At 24 months, immediate combination treatment with either strategy was more effective than methotrexate monotherapy prior to step-up. Initial use of methotrexate monotherapy with the addition of sulfasalazine plus hydroxychloroquine; or etanercept, if necessary after 6 months, is a reasonable therapeutic strategy for early RA. The combination of etanercept plus methotrexate resulted in a statistically significant, but clinically small, radiographic benefit over oral triple therapy.

INTRODUCTION

The treatment of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) has changed dramatically over the past decade, including 5 FDA-approved biological therapies that block tumor necrosis factor (TNF) (1-7). Disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs) have long been the cornerstone of RA therapy (8, 9), and among traditional, oral DMARDs, methotrexate (MTX) has emerged as the preferred first-line agent (10, 11). There are no blinded data directly comparing an oral DMARD combination [MTX plus sulfasalazine (SSZ) plus hydroxychloroquine (HCQ)] (8, 12) to anti-TNF plus MTX (13, 14) in early RA. Since oral triple therapy DMARDs have major cost advantages over biologic therapy, their comparative efficacy is of interest (15, 16).

The traditional approach for the management of early RA is a “step-up” approach, where initial treatment with MTX is incrementally supplemented with other DMARDs in patients with persistent disease. Early “immediate” treatment with a combination of a biologic and DMARDs reduces the proportion of participants that advance to severe disability (5, 13, 17). However, this approach requires the use of multiple DMARDs in all participants, including those who might have responded to MTX monotherapy (13, 18, 19). It remains to be determined if step-up DMARD therapy can provide similar clinical and radiologic benefits as initial use of combination DMARD therapy.

Designed in 2000 and implemented in 2004, this investigator-initiated study aimed to assess two clinically important questions in early, aggressive RA as measured by a 28-joint disease activity score with an erythrocyte sedimentation rate (DAS28-ESR). First, is immediate, combination therapy (either ETN + MTX or oral triple therapy) more effective than MTX monotherapy with step-up approach? Second, what is the comparative efficacy in early RA of treating with a combination of MTX and an anti-TNF biologic agent (etanercept, ETN) versus oral triple therapy?

METHODS

Research Design and Methods

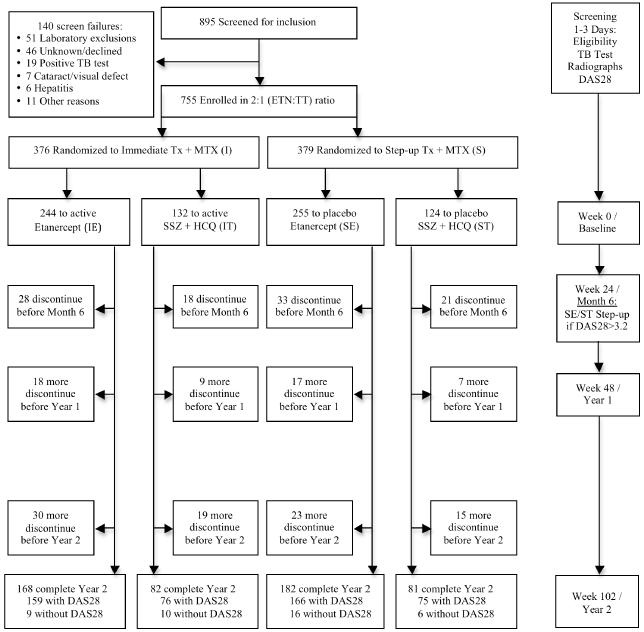

The 2×2 factorial design called for 4 treatment arms: immediate treatment with 1) ETN+MTX; or 2) MTX+SSZ+HCQ (triple therapy); or 3) initial MTX, with step-up treatment adding ETN if DAS28-ESR was ≥ 3.2 at week 24; or 4) initial MTX, with step-up treatment adding SSZ + HCQ if DAS28-ESR was ≥ 3.2 at week 24 (Figure 1). It is important to note that there was no randomization to an MTX monotherapy arm for the full length of the 102-week trial. Randomization to the step-up arms occurred at baseline, and all participants in the two step-up arms were eligible to step-up to active medication if their DAS28-ESR was ≥ 3.2. Those that did not step-up at week 24 were included in their assigned treatment group for analysis regardless of step-up status. Randomization to the step-up arms was performed at baseline for two reasons: 1) to alleviate site and participant burden at week 24 by allowing for the appropriate step-up kits to be available on-site for the week 24 visit and 2) to allow for the utilization of a 2×2 factorial design during analysis. All subjects received placebo complements of non-active therapies. All subjects and site personnel, including the treating rheumatologist, were masked for the length of the trial to treatment assignment and change to active medication at the step-up period. TEAR was registered with clinicaltrials.gov (NCT00259610) and approved by local IRB committees.

Figure 1.

Disposition of Participants

Participants

At enrollment, entry criteria included disease duration < 3 years from the time of diagnosis; age over 18 years; RA diagnosis by the 1987 ACR criteria (20); active disease (at least 4 swollen and 4 tender joints, using the 28-joint count); positive for rheumatoid factor (RF) or cyclic citrullinated peptide (CCP) antibodies, or if seronegative, have at least 2 erosions by radiographs of hands/wrists/feet; if taking corticosteroids, receiving stable doses at least 2 weeks prior to screening (≤ 10 mg/day of prednisone); and if taking non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, receiving stable doses for at least 1 week. Exclusion criteria were contraindications to study medications; prior use of biologic therapy of any type, at any dosage; corticosteroid injections during the 4 weeks prior; and diagnosis of serious infection, including positive skin test for TB. Prior use of leflunomide, HCQ, and SSZ was allowable for no more than 2 months. Also permitted was a total dose of ≤ 40 mg of MTX.

Study Protocol

All baseline assessments were performed at the screening visit; time between the screening and baseline visits was minimal (< 3 days). Treatment was allocated via a computerized data entry system (DES) in a 2:1 ratio for ETN versus triple therapy in a standard permuted block approach, by site, with block sizes of 6 or 12. The DES masked both participants and investigators at all visits to study medication arm, where medication kits were assigned to participant by utilizing a blinded drug distribution system. Investigators and participants remained masked to treatment assignment until the end of year 2. Matching placebos were utilized throughout the trial, including the step-up period, where all participants were dispensed a step-up kit even if the participant was already on immediate therapy (step-up medication kits contained all active medication) or was not stepping-up to active therapy (step-up medication kits contained all placebo medication). After obtaining informed consent, participants were screened for eligibility by rheumatologists at 44 centers. Following randomization, participants were monitored for 102 weeks. Joint assessment occurred every 6 weeks during the first 48 weeks and every 12 weeks thereafter. Radiographs of hands, wrists, and feet were acquired at baseline, and weeks 48 and 102.

Study Medications

Methotrexate

All participants received oral MTX, escalated to 20 mg/wk, or a lower dose if it resulted in no active tender/painful or swollen joints, by Week 12. Immediate Therapy, SSZ + HCQ (IT): SSZ at 500 mg twice a day, and if tolerated, escalated to 1000 mg twice a day at 6 weeks; plus HCQ 200 mg twice a day. Immediate Therapy, ETN (IE): ETN 50 mg subcutaneously weekly. Step-up Therapy: At the 24-week time point, participants in the 2 step-up arms with DAS28-ESR ≥ 3.2 maintained the same dose of MTX, and placebo was switched to either active ETN (etanercept group, SE) or SSZ plus HCQ (triple therapy group, ST). Participants in the 2 step-up arms with DAS28-ESR < 3.2 maintained the same dose of MTX therapy and placebos. Folic Acid: All participants were given folic acid 1 mg per day.

Corticosteroid Use

Participants taking daily oral corticosteroids at entry tapered their dose if they had an improvement in disease activity prior to Week 24. If the participant’s DAS28-ESR score was less than 3.2, the dose of prednisone could be reduced by 1 mg/month or 2.5 mg/month. Corticosteroid tapering could not be changed within 4 weeks of the 24-week visit. If participants had a disease flare during a reduction in corticosteroid dose, then they resumed their previous baseline dose. A single intra-articular injection of corticosteroids was allowed during the study; the injected joint was considered to be non-evaluable for subsequent study visits.

Toxicity and Event Monitoring

Participants who developed toxicity secondary to MTX had the drug discontinued or dosage decreased at the discretion of the treating physician. If stopping the MTX or reducing its dose for 2 weeks resolved the toxicity, then the dose of MTX was left at a tolerable dose. A similar strategy was used in making dose adjustments for suspected SSZ toxicity. Drug toxicity was assessed at 6-week intervals via laboratory measures and assessment of adverse events.

Study Outcomes

The primary endpoint for the trial was an observed-group analysis of the DAS28-ESR between weeks 48 and 102 (21, 22); with secondary endpoints defined by the ACR criteria for 20% improvement (ACR 20), ACR50, and ACR70; physical disability [modified Health Assessment Questionnaire (mHAQ)]; and joint damage (radiographic assessments) (23). Radiographic progression was evaluated in the hands, wrists and feet. The radiographs were scored according to the van der Heijde modified Sharp method by two independent readers (24). The readers scored all the films grouped per patient but blinded for time sequence and clinical data. The mean score of the two readers was used (Intraclass Correlation 0.96).

Statistical Analysis

Analysis was performed using intention-to-treat (ITT), including participants in the groups to which they were randomized, regardless of compliance to drug during the trial. The primary outcome of the study was analyzed using a two-way, repeated-measures, mixed-model analysis with DAS28-ESR from weeks 48 to 102 (22), to allow for assessment of change over the entire year-2 period. Effects considered were treatment (ETN+MTX; SSZ+HCQ+MTX), timing of treatment (Immediate, Step-up) and the interaction between treatment and timing creating the four treatment groups (IE, IT, SE, ST). If the interaction was not statistically significant at the α = 0.10 level, we planned to remove the interaction term of treatment by timing from the random effects regression models, and assess the differences between treatment groups; The study was not powered for the interaction but for the two main effect comparisons. Weeks 48 to 102 were used to allow sufficient time for those receiving step-up medication at week 24 to achieve maximal efficacy. A participant had to reach week 48 to be included in the primary analysis; however, subsequent analysis for the entire 102-week period is also presented. A priori covariate adjusted models were also considered to reduce error variance and thereby improve precision, rather than to adjust the potential confounding effect of the covariates. Secondary outcomes included assessing treatment differences in: the pattern of DAS28-ESR scores between 0 and 102 weeks; radiographic disease progression between baseline and week 102 (24); ACR20, 50, and 70 between weeks 48 and 102; discontinuation of treatment for lack of efficacy; major clinical response (participants who meet an ACR70 response on 2 consecutive 3-month visits between 48 and 102 weeks); DAS28-ESR< 2.6 criteria between 48 and 102 weeks (22); functional status between 48 and 102 weeks; and health related quality of life between 48 and 102 weeks as assessed by the Short Form Health Survey (SF-12).

Results were presented as all observed data, without imputation for missing values (All Observed), as data from only the participants who completed 102 weeks (Completers), or as a non-responders analysis as indicated. Data is reported as mean ± SD or N (%) for descriptive analyses. We analyzed differences in the pattern of outcomes over time using the repeated-measures, mixed-model approach (25), with Tukey-Kramer adjustment for multiple comparisons with unbalanced treatment arms. This approach allows for use of all observed data without imputation for missing values. Intention-to-treat was maintained for all analyses regardless of data imputation methods utilized.

For function and disability changes from baseline to year 2, cross-sectional differences at specific time-points between treatment groups were assessed using an Analysis of Covariance (ANCOVA) approach, where the difference was assessed after adjustment for covariates assumed a priori to be associated with outcome.

Covariates were utilized to reduce error variance and increase precision: age, sex, race/ethnicity, duration of disease, prior DMARD use, RF status, DAS28-ESR, and body mass index (BMI) at screening. Tests were performed at the 0.05 level (unless noted otherwise) utilizing SAS v9 or JMP v8 (Cary, NC).

Radiographic changes were analyzed using an ANCOVA approach, where the differences between mean progression scores of treatment groups at two years were assessed after adjustment for the baseline radiographic score. In addition, ANCOVA using ranks of the modified Sharp progression scores with baseline ranks as a covariate was also considered, as were repeated-measures, mixed-models for analysis of changes over the two year period.

Chi-square tests were used to assess differences in the proportion of participants meeting ACR Criteria at months 6, 12, and 24 (with dropouts considered failures i.e. non-responder imputation), and for treatment discontinued for lack of efficacy. Lack of efficacy was defined by individual participants who chose “perceived lack of benefit”, as the reason for termination.

Power and Sample Size Estimation

The study was designed to have 80% power to detect a 0.30 unit difference in the DAS28-ESR between treatment arms with 675 participants, pooled across timing arms (step-up versus immediate). Assuming a 10% drop out rate, the target sample size for recruitment was 750. The trial was designed with a 2:1 treatment allocation for ETN vs. triple therapy arms to allow for sufficient power to compare the IE and SE arms with respect to radiographic outcomes.

Study Organization

The Clinical Coordinating Center and Statistical and Data Management Center for the study were located at the University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB). The protocol was developed in 2003; recruitment began in May 2004 and concluded in January 2007 under protocol Amendment 4 with no substantial changes to eligibility criteria. One center with 5 participants was closed for administrative reasons due to failure of protocol adherence at the center level; the site was closed prior to any of the 5 participants reaching the step-up period and not measurable for the primary outcome; these participants were excluded from all analyses. All centers received local IRB or Western IRB approval.

Role of the Funding Source

This investigator-initiated trial utilized a planning grant from NIAMS. After completion of the planning process, Amgen Inc. provided funding, but was not responsible for collection of the data or the data analysis. UAB was solely responsible for all data collection, data management, and statistical analysis, and the decision to publish these results.

RESULTS

Characteristics of Participants and Study Completion

895 participants were screened for the study, and 755 were enrolled and randomized. Characteristics of participants at baseline are summarized in Table 1, with disease status summarized in Table 2. There were no significant differences between the groups in pre-treatment characteristics or baseline disease activity, including prior DMARD and corticosteroid usage.

Table 1.

Demographics and baseline characteristics of randomized population (N = 755)*

| IE | IT | SE | ST | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N, % of total in treatment arm | 244 (32.3) | 132 (17.5) | 255 (33.8) | 124 (16.4) |

| Age, years | 50.7±13.4 | 48.8±12.7 | 48.6±13.0 | 49.3±12.0 |

| Female | 181 (74.2) | 101 (76.5) | 176 (69.0) | 87 (70.2) |

| Race: Caucasian | 188 (77.1) | 107 (81.1) | 200 (78.4) | 106 (85.5) |

| African American | 31 (12.7) | 11 (8.3) | 29 (11.4) | 14 (11.3) |

| Ethnicity: Hispanic/Latino | 26 (10.7) | 17 (12.9) | 32 (12.6) | 10 (8.1) |

| Body Mass Index | 29.3±7.0 | 30.0±8.2 | 30.0±6.7 | 29.2±7.3 |

| Disease duration (months) | 3.5±6.4 | 4.1±7.2 | 2.9±5.6 | 4.5±7.6 |

| RF + | 216 (88.5) | 121 (91.7) | 232 (91.0) | 108 (87.1) |

| RF− and CCP+ | 8 (3.3) | 4(3.0) | 9 (3.5) | 4(3.2) |

| CCP−/not tested with 2 erosions | 20 (8.2) | 7(5.3) | 14 (5.5) | 12 (9.7) |

| Prior DMARD use | 68 (27.9) | 30 (22.7) | 58 (22.8) | 22 (17.7) |

| Etanercept use** | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.4) | 0 |

| Infliximab use** | 1 (0.4) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Anakinra use** | 1 (0.4) | 0 | 1 (0.4) | 0 |

| HCQ use | 5 (2.1) | 3 (2.3) | 4(1.6) | 3 (2.4) |

| SSZ use | 1(0.4) | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.8) |

| MTX use | 60 (24.6) | 27 (20.5) | 52 (20.4) | 18 (14.5) |

| MTX use > 40 mg total** | 3 (1.2) | 1 (0.8) | 3(1.2) | 3(2.4) |

| Taking low-dose corticosteroids at screening: | 105 (43.0) | 58 (43.9) | 111 (43.5) | 41 (33.1) |

| Mean dose, if corticosteroid use at screening (mg prednisone/day) |

3.4±4.3 | 3.4±4.2 | 3.4±4.3 | 2.6±4.1 |

Mean±SD or number of participants (%), no differences across treatment arms, all p>0.05

Protocol Exception/Violation

Table 2.

Baseline and follow-up of clinical characteristics*

| Week 102 Completers (N=476) | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline (N=755) | Baseline | Year 2 | ||||||||||

| IE (244) | IT (132) | SE (255) | ST (124) | IE (159) | IT (76) | SE (166) | ST (75) | IE (159) | IT (76) | SE (166) | ST (75) | |

| mHAQ ** | 1.1±0.4 | 1.0±0.4 | 1.0±0.4 | 1.0±0.4 | 1.1±0.4 | 1.0±0.3 | 1.0±0.4 | 1.0±0.4 | 1.0±0.3 | 1.0±0.3 | 0.9±0.3 | 0.9±0.3 |

| HAQ Pain *** | 5.3±2.6 | 5.3±2.5 | 5.2±2.4 | 5.1±2.5 | 5.4±2.6 | 5.3±2.4 | 5.0±2.5 | 4.9±2.3 | 2.1±2.3 | 2.3±2.3 | 2.3±2.5 | 2.3±2.5 |

| Patient Global | ||||||||||||

| Physician Global |

||||||||||||

| Swollen joints | 12.7±5.8 | 12.1±5.8 | 13.1±6.2 | 13.1±6.1 | 12.7±5.6 | 12.5±5.8 | 12.5±5.9 | 13.1±5.5 | 2.2±3.9 | 2.3±3.3 | 4.4±3.1 | 4.4±2.8 |

| Tender joints | 14.3±6.6 | 14.1±6.8 | 14.2±6.9 | 14.6±7.0 | 13.6±6.4 | 14.1±6.8 | 13.7±6.8 | 13.8±7.0 | 3.3±5.5 | 2.6±4.5 | 3.6±5.8 | 2.6±4.4 |

| ESR | 33.6±26.8 | 33.1±27.0 | 32.4±27.0 | 32.4±25.5 | 37.1±26.9 | 33.7±25.4 | 35.0±28.3 | 32.5±24.9 | 17.2±15.8 | 17.2±15.1 | 17.7±18.6 | 15.5±19.4 |

| DAS28-ESR | 5.8±1.1 | 5.8±1.1 | 5.8±1.1 | 5.8±1.1 | 5.9±1.1 | 5.8±1.1 | 5.8±1.1 | 5.8±1.0 | 3.0±1.4 | 2.9±1.5 | 3.1±1.4 | 2.8±1.3 |

| Radiograph, N | 208 | 115 | 211 | 110 | 141 | 74 | 139 | 63 | 141 | 74 | 139 | 63 |

| Erosions | 3.3±6.5 | 3.3±6.7 | 2.5±3.5 | 3.6±7.5 | 3.2±7.0 | 2.6±3.5 | 2.4±3.4 | 2.6±3.4 | 3.6±7.4 | 3.3±3.9 | 3.0±3.9 | 3.3±4.4 |

| Joint Space Narrowing |

3.5±9.3 | 3.7±8.4 | 1.9±4.3 | 3.6±10.3 | 3.3±9.8 | 2.7±6.0 | 1.6±3.7 | 2.2±4.5 | 3.7±9.8 | 3.9±10.6 | 2.1±4.4 | 2.6±5.0 |

| Total Score | 6.8±14.8 | 6.9±14.2 | 4.4±7.2 | 7.2±17.0 | 6.5±16.1 | 5.4±8.4 | 4.1±6.4 | 4.8±7.0 | 7.0±16.6 | 7.3±13.3 | 4.8±7.2 | 6.2±8.9 |

Mean±SD;

N Complete for mHAQ (modified Health Assessment Questionnaire): All Observed Baseline IE:227, IT:125, SE:237, ST:117; Completers IE:151, IT:73, SE:154, ST:71;

N Complete for HAQ Pain: All Observed Baseline IE: 243, IT:131, SE:255, ST:124; Completers as shown

The drop-out rate was 32.1% with 67.9% of participants completing the 2-year trial, including 168 (68.8%) in the IE group, 82 (62.1%) IT group, 182 (71.4%) SE group, and 81 (65.3%) in the ST group; there was no differential drop across the four treatment arms (p=0.73), the timing of treatment (I vs. S, p=0.61) or the type of medication (ETN+MTX vs. triple therapy, p=0.18). Forty-two percent (n=100) of withdrawals were participant decision; the most common reasons for withdrawal being a perceived lack of efficacy (n=31) or unspecified reason/lost to follow-up (n=29). For participants terminating early, there were no differences across the 4 treatment arms in the DAS28-ESR scores at time of termination, mean days in study, reason for termination, demographics, or proportion that terminated early; therefore the missing observations were assumed to be missing at random in the analysis. DAS28-ESR results for the 596 participants that had at least one measure between years 1 and 2 were included in the primary analysis. However, of the 513 participants who reached two years, only 476 had data sufficient to determine the DAS28-ESR score at week 102.

Compliance was measured by self-report at 10 study visits after baseline: Excellent, patient reports taking medication as directed (takes medications 99% of time); Good (missed two or fewer doses of the oral medication or one dose of the weekly injection); Fair (missed two or fewer doses of the oral medication and two or fewer of the weekly injection); Poor (missed two or more doses of the oral medication and two or more of the weekly injection); or Uncertain. At no point during the trial was there a difference in the compliance to any of the treatment arms by timing of medication (I vs. S, p=0.74) or type of medication (ETN+MTX vs. triple therapy, p=0.76), with 94% of all study visits reporting Good or Excellent compliance.

Efficacy

DAS28-ESR and remission

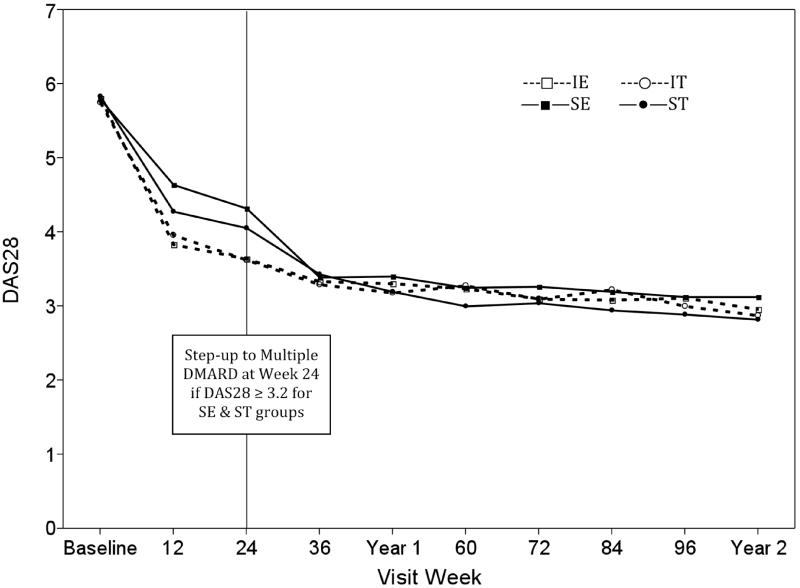

The primary outcome of this study was mean DAS28-ESR from weeks 48 to 102 (Figure 2). At week 24, 28% of the subjects who were initially in the two MTX-only (SE, ST) arms had a DAS28-ESR ≤ 3.2, and thus did not step-up, resulting in 72% of participants stepping up to active ETN or SSZ+HCQ as determined at randomization (by comparison, 41% of the immediate ETN+MTX and 43% immediate triple therapy groups had a DAS28-ESR ≤ 3.2 by week 24). The two Immediate (IE/IT) groups demonstrated a larger reduction in DAS28-ESR score at week 24 compared to the step-up groups (SE/ST): 3.6 in IE/IT vs. 4.2 SE/ST, p<0.0001. However, the SE and ST groups showed improvement in mean DAS28-ESR scores by week 36, and by week 48 all groups had similar mean DAS28-ESR. The analysis of the primary outcome showed no significant difference in DAS28-ESR scores between weeks 48 and 102, across the four treatment arms (p=0.28), by medication received (ETN+MTX vs. triple therapy, p=0.48) or treatment regimen (Immediate vs. Step-up, p=0.55). 56% of all participants achieved DAS28-ESR remission, defined as DAS28-ESR<2.6, at some point during follow-up. There was no differences in the proportion achieving DAS28-ESR remission across the four treatment arms (56.6% IE, 59.1% IT, 52.9% SE, 56.5% ST, p=0.93), nor was there a difference by timing of treatment (I vs. S, p=0.36) or medication received (ETN+MTX vs. triple therapy, p=0.43).

Figure 2.

Observed DAS28-ESR

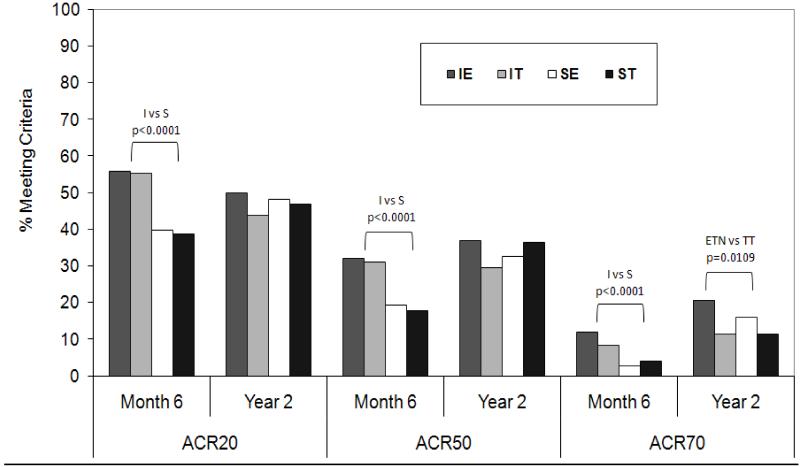

ACR Response and Major Clinical Response

ACR responses were evaluated utilizing a non-responders analysis. If a participant terminated early, they were assumed to not have achieved an ACR response at subsequent visits. The percentage of subjects in each treatment arm with an ACR20, ACR50, or ACR70 response is shown in Figure 3. At Month 6, both IT groups had a higher proportion of participants meeting ACR20, 50 and 70 compared to Step-up groups (all p<0.0001), with no difference observed between treatment received, ETN+MTX or triple therapy. By Year 2, there was no difference in the proportion meeting any of the ACR criteria by timing of treatment (I vs. S); the only significant treatment difference at week 102 was between the ETN and triple therapy groups for ACR70 (18.2% vs. 11.3%, p=0.02).

Figure 3.

Percentage of participants in TEAR achieving ACR20, 50, and 70 criteria at time of step-up at 6 months and at the 2 year conclusion of the study (with drop-outs considered failures i.e. non-responder imputation)*

* I = Immediate; S = Step Up; ETN = Etanercept + MTX; TT = Triple Therapy (SSZ+HCQ+MTX)

Function and Disability

Using data from participants who completed 102 weeks, all treatment groups showed decreases at Years 1 and 2 for the mHAQ and mHAQ Pain scores (Table 2). All groups demonstrated similar improvement at Years 1 and 2, with no statistically significant differences between treatment and timing of treatment. For all available observed mHAQ Pain and mHAQ scores, there were no statistically significant differences in the timing (I vs S) or the treatment regimen (E vs T).

Radiographic Results

The mean (SD) radiographic scores at weeks 0 and 102 are listed in Table 2. There was no difference in the change in week 102 scores from baseline when comparing step-up to immediate combination therapy, regardless of the assigned treatment (I vs S, p=0.74). When the immediate and step-up groups were combined into two groups, ETN + MTX had a smaller increase in radiographic scores compared to those using triple therapy (p=0.047). Radiographic progression was defined as a change > 0.5 from week 0 to week 102. Using this definition, 33.6% of participants showed radiographic progression. The percentages of subjects with non-progression were: 79.4% for IE group, 64.9% IT, 71.1% SE, and 68.3% ST (p=0.33). While there was no difference in the proportion of subjects with non-progression across the four treatment arms (p=0.33) or timing of treatment (74.4% I vs. 72.3% S, p=0.56), a difference was noted in this radiographic outcome for those subjects receiving ETN+MTX compared to oral triple therapy (76.8% vs. 66.4%, p=0.02). There was a single participant with a change in total radiographic score of 78.5. A rank regression analysis was performed to attenuate the effect of this outlier, resulting in a nominal difference between the ETN+MTX versus triple therapy groups (p=0.069).

Corticosteroid Use

As shown in Table 1, there were no differences at study entry in the steroid usage across treatment groups. In addition, there were no differences seen in the steroid use during the trial (Table S1), either by participants discontinuing after enrollment, using rescue steroids during the trial, or in the frequency or number of intra-articular injections.

Safety and Tolerability

There was no difference in the number of participants experiencing any adverse event (AE) or serious adverse event (SAE), across treatment groups (Table 3, p=0.47). There was no difference in the mean number of events for those participants reporting at least 1 AE or SAE (p=0.13). There was no difference in the number of participants experiencing an SAE, across treatment groups (p=0.94).

Table 3.

Safety Summary by Treatment Group.

| IE (244) | IT (132) | SE (255) | ST (124) | Total (755) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participants with any event (AE or SAE) | 193(79.1) | 101(76.5) | 187(73.3) | 92(74.2) | 573(75.9) |

| With event: Mean (SD) number of events | 3.6 (3.0) | 3.3 (2.4) | 4.1 (3.1) | 3.4 (2.9) | 3.7(2.9) |

| Range of events | 1-22 | 1-11 | 1-18 | 1-13 | 1-22 |

| Participants with a Serious Adverse Event | 35(14.3) | 18(13.6) | 32(12.5) | 16(12.9) | 101(13.4) |

| With SAE: Mean (SD) number of events | 1.3(0.6) | 1.3(0.6) | 1.2(0.4) | 1.3(0.5) | 1.3(0.5) |

| Range of events | 1-3 | 1-3 | 1-2 | 1-2 | 1-3 |

| Deaths* | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 4 |

| Organ Systems of SAE (including deaths)** | 44 | 24 | 38 | 21 | 127 |

| Blood and lymphatic system | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 3(2.4) |

| 16(12.6) | |||||

| Cardiac | 5 | 2 | 4 | 5 | |

| Eye | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1(<1) |

| Gastrointestinal | 2 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 7(5.5) |

| General and administration site | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 3(2.4) |

| Immune system | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1(<1) |

| Infections and infestations*** | 9 | 4 | 7 | 3 | 23(18.1) |

| Injury and poisoning | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 4(3.1) |

| Investigations | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 5(3.9) |

| Metabolism and nutrition | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2(1.6) |

| Musculoskeletal and connective tissue | 1 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 5(3.9) |

| Neoplasms benign and malignant**** | 5 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 7(5.5) |

| Nervous system | 2 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 8(6.3) |

| Pregnancy, puerperium and perinatal | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2(1.6) |

| Psychiatric | 3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 4(3.1) |

| Reproductive system and breast | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 3(2.4) |

| Respiratory, thoracic and mediastinal | 5 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 9(7.1) |

| Surgical and medical procedures | 6 | 5 | 7 | 1 | 19(15.0) |

| Vascular | 0 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 5(3.9) |

Three deaths due to cardiac disorders: general (unattended death), coronary heart failure, ventricular septal defect; one due to respiratory failure.

Multiple events per subject; organ system will not necessarily total the sum of the individuals with events as a participant can report more than one event; percents shown are percent of events within a system out of number of events within treatment group.

Twenty-three serious infections were reported (9 in the IE group, 4 IT, 7 SE, 3 ST): 9 Pneumonia (4 IE, 1IT, 4 SE, 2 ST), 3 cellulitis (all IE), and 2 bronchitis (all IT); all other infections 1 per type (3 IE, 1 IT, 3 SE, 2 ST).

Seven malignant diseases were reported (5 in IE, 1 IT, and 1 ST): 2 breast cancer (1 in IT), 3 lung cancer (1 in ST), 1 prostate cancer, and 2 renal carcinoma. None of the reproductive or breast system disorders were breast cancer related.

DISCUSSION

The TEAR study is the only randomized, double-blind study to compare oral triple DMARD therapy to the combination of ETN plus MTX. The primary outcome revealed no differences between the two treatment approaches. Additionally, 28% of participants had an excellent clinical response to MTX monotherapy and achieved low disease activity by 6 months, consistent with other recently published results (13, 18, 19).

We observed a higher rate of participants not completing the study than we had originally expected. However, this was similar to other long-term (1-2 year) RA studies (13, 18). Most of this dropout occurred within the first year of the study: 33% dropout by week 48, and 37% by week 102. While the mixed-model approach allows for inclusion of all observed values, several alternative statistical approaches [completers, last observation carried forward (LOCF), mean imputation] were used to account for missing data, and all suggested that the missing data from the dropouts did not significantly influence the overall conclusions.

There were no differences in radiographic changes comparing immediate DMARD therapy to the step-up approaches. Radiographic data at week 102 showed a small, statistically significant (p=0.047) difference between the mean progression of joint damage in subjects who received the combination of ETN + MTX compared to triple DMARDs. There are limited data on the significance of erosions and/or joint space narrowing on physical disability. An approach has been published by Smolen et al (26) that estimates the numerical relationship between HAQ and damage where 0.01 HAQ points corresponds to 1 point total Sharp score. Thus, the minimal differences in radiographic progression do not translate into clinically meaningful changes in disability over the 2-year period of observation. The accumulation of erosions past 2 years and its potential impact on disability are not addressed by this study.

There were similar 2-year improvements in outcomes across groups in functional status and pain and relatively little differences among groups in radiographic progression. These data strongly suggest that the cost-effectiveness of less expensive triple therapy may be positive relative to anti-TNF therapy.

We chose a 6-month time point to step up from MTX monotherapy mainly to allow for lag time of drug effects. However, at 12 weeks all four treatment groups seem to have stabilized in terms of DAS-28 response, thus, suggesting that a decision point at 12 weeks is a good guideline for clinical practice.

There are several strengths of the TEAR trial. The double-blind, randomized aspects reduce bias due to contamination between treatment arms for patients who might preferentially drop out if they knew they were not in a biologic arm. The 2-year outcomes, and the ability to change therapy at 6 months based on clinical response within the blinded trial, are pragmatic. This was a trial of early disease (mean disease duration 3.6 months).

There are limitations to the TEAR trial. There are clinical situations where MTX is not the ideal choice for initial DMARD therapy. Additionally, the TEAR study was performed in patients with a more severe phenotype (CCP and/or RF positive or erosive disease). Thus, the results may not be generalizable to patients with less active disease, those who are autoantibody-negative, and/or in patients with longer disease duration.

In conclusion, the TEAR trial – a blinded, placebo-controlled investigator-initiated study involving participants with early active RA – demonstrated that the treatment strategies of oral triple DMARD compared to ETN plus MTX result in comparable clinical outcomes and small radiographic differences after 2 years of therapy. Initial MTX monotherapy, with step-up to combination therapy, if necessary after 6 months, may be cost-effective with only a slight delay in attaining the same 48 to 102 week outcomes as immediate combination therapies.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Sources of support: This was an investigator-initiated trial with Amgen providing the support for the trial through a grant to the University of Alabama at Birmingham. Drugs and placebos were provided by their respective manufacturers.

Funding/Support: The financial support for the trial was from Amgen, and medications were provided by Amgen (etanercept and placebo), Barr Pharmaceuticals (methotrexate), and Pharmacia (sulfasalazine and placebo). An NIH planning grant (PI: Moreland; 1 R34 AR055122) from NIAMS supported the initial phases of the TEAR study.

Role of the Sponsor: The funding organizations had no role in the design and conduct of the study, in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data, or in the preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: Dr. Moreland, Dr. O’Dell, Dr. St.Clair, Dr. Curtis, Dr. Bathon, Dr. Bridges, Dr. Paulus, Dr. Cofield, and Dr. van der Heijde had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Study concept and design: Moreland, O’Dell, St.Clair, Bathon, Bridges, Paulus, Cofield, van der Heijde, Howard

Acquisition of data: Moreland, O’Dell, St.Clair, Zhang, Bathon, Bridges, Paulus, Cofield, van der Heijde, Howard

Analysis and interpretation of data: Moreland, O’Dell, St.Clair, Curtis, Bathon, Bridges, Paulus, McVie, Cofield, van der Heijde, Howard

Drafting of the manuscript: Moreland, O’Dell, St.Clair, McVie, Cofield

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Moreland, O’Dell, St.Clair, Zhang, Curtis, Bathon, Bridges, Paulus, Cofield, van der Heijde, Howard

Statistical analysis: Curtis, McVie, Cofield, Howard

Obtained funding: Moreland, O’Dell, Bridges, Cofield

Administrative, technical, or material support: Moreland, O’Dell, Zhang, Bathon, Bridges, Paulus, Cofield

Study supervision: Moreland, O’Dell, Paulus, Cofield

Radiographic analysis: van der Heijde

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: All authors have completed and submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Dr. Bathon reports receipt of compensation from Crescendo Biosciences (2008-2009; for consulting work) and from Roche (2009-2010; for consulting work). Dr. Curtis reports receipt of compensation from Roche/Genentech, UCB, Centocor, CORRONA, Amgen, Pfizer, BMS, Crescendo, and Abbott (2008-2011; for consulting work) and from UCB and Genetech (2008-2011; for lectures). Additionally, Dr. Curtis reports grants and/or pending grants from Roche/Genentech, UCB, Centocor, CORRONA, Amgen, Pfizer, BMS, Crescendo, and Abbott (2008-2011). Dr. Zhang reports receipt of compensation from Amgen (2008-2011; for consulting work). Dr. Cofield reports receipt of compensation from Teva Neuroscience and the American Shoulder and Elbow Society (2008-2011; for consultancy work) and from Centocor Ortho Biotech Services L.L.C. (2008-2011; for DSMB activities). Dr. van der Heijde reports receipt of compensation from Abbott, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bristol Meyers Squibb, Centocor, Chugai, Eli-Lilly, Glaxo Smith Klein, Merck, Novartis, Otsuka, Pfizer, Roche, Sanofi-Aventis, Schering-Plough, UCB, and Wyeth (2008-2011; for consulting work) and from UCB (2008-2011; for lectures and development of educational presentations). None of the compensation reported by these investigators was related to the work in this manuscript. Other authors reported no potential conflicts.

Additional Contributions: We thank the Data Safety Monitoring Board (Michael Weinblatt, MD of Brigham and Women’s Hospital; David Wofsy, MD of UCSF; Mark Genovese, MD of Stanford University; and Barbara Tilley, PhD of Medical University of South Carolina) and the external medical safety monitor, Gene Ball, MD from Birmingham, AL. DSMB members were compensated for their time and travels. We appreciate the support of all of the clinical investigators, their staff, and all of the patient participants. Investigators, their staff, and the patient participants were compensated for their efforts. Editing assistance was provided by Douglas W. Chew of the University of Pittsburgh.

REFERENCES

- 1.Moreland LW, Baumgartner SW, Schiff MH, Tindall EA, Fleischmann RM, Weaver AL, et al. Treatment of rheumatoid arthritis with a recombinant human tumor necrosis factor receptor (p75)-Fc fusion protein. N Engl J Med. 1997;337(3):141–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199707173370301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lipsky PE, van der Heijde DM, St Clair EW, Furst DE, Breedveld FC, Kalden JR, et al. Infliximab and methotrexate in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Anti-Tumor Necrosis Factor Trial in Rheumatoid Arthritis with Concomitant Therapy Study Group. N Engl J Med. 2000;343(22):1594–602. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200011303432202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Breedveld FC, Weisman MH, Kavanaugh AF, Cohen SB, Pavelka K, van Vollenhoven R, et al. The PREMIER study: A multicenter, randomized, double-blind clinical trial of combination therapy with adalimumab plus methotrexate versus methotrexate alone or adalimumab alone in patients with early, aggressive rheumatoid arthritis who had not had previous methotrexate treatment. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54(1):26–37. doi: 10.1002/art.21519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Emery P, Breedveld FC, Hall S, Durez P, Chang DJ, Robertson D, et al. Comparison of methotrexate monotherapy with a combination of methotrexate and etanercept in active, early, moderate to severe rheumatoid arthritis (COMET): a randomised, double-blind, parallel treatment trial. Lancet. 2008;372(9636):375–82. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61000-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smolen JS, Van Der Heijde DM, St Clair EW, Emery P, Bathon JM, Keystone E, et al. Predictors of joint damage in patients with early rheumatoid arthritis treated with high-dose methotrexate with or without concomitant infliximab: results from the ASPIRE trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54(3):702–10. doi: 10.1002/art.21678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Emery P, Fleischmann RM, Moreland LW, Hsia EC, Strusberg I, Durez P, et al. Golimumab, a human anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha monoclonal antibody, injected subcutaneously every four weeks in methotrexate-naive patients with active rheumatoid arthritis: twenty-four-week results of a phase III, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of golimumab before methotrexate as first-line therapy for early-onset rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;60(8):2272–83. doi: 10.1002/art.24638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weinblatt M, Fleischmann R, Emery P, Goel N, Bingham C, Pope J, et al. Efficacy and Safety of Certolizumab Pegol in a Clinically Representative Population of Patients (Pts) with Active Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA): Results of the REALISTIC Phase IIIb Randomized Controlled Study. ARTHRITIS & RHEUMATISM. 2010;63(10 (supplement)):S752–S3. [Google Scholar]

- 8.O’Dell JR, Haire CE, Erikson N, Drymalski W, Palmer W, Eckhoff PJ, et al. Treatment of rheumatoid arthritis with methotrexate alone, sulfasalazine and hydroxychloroquine, or a combination of all three medications. N Engl J Med. 1996;334(20):1287–91. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199605163342002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boers M, Verhoeven AC, Markusse HM, van de Laar MA, Westhovens R, van Denderen JC, et al. Randomised comparison of combined step-down prednisolone, methotrexate and sulphasalazine with sulphasalazine alone in early rheumatoid arthritis. Lancet. 1997;350(9074):309–18. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)01300-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Saag KG, Teng GG, Patkar NM, Anuntiyo J, Finney C, Curtis JR, et al. American College of Rheumatology 2008 recommendations for the use of nonbiologic and biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis & Rheumatism. 2008;59(6):762–84. doi: 10.1002/art.23721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smolen JS, Landewe R, Breedveld FC, Dougados M, Emery P, Gaujoux-Viala C, et al. EULAR recommendations for the management of rheumatoid arthritis with synthetic and biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69(6):964–75. doi: 10.1136/ard.2009.126532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mottonen T, Hannonen P, Leirisalo-Repo M, Nissila M, Kautiainen H, Korpela M, et al. FIN-RACo trial group Comparison of combination therapy with single-drug therapy in early rheumatoid arthritis: a randomised trial. Lancet. 1999;353(9164):1568–73. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(98)08513-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Klareskog L, van der Heijde D, de Jager JP, Gough A, Kalden J, Malaise M, et al. Therapeutic effect of the combination of etanercept and methotrexate compared with each treatment alone in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: double-blind randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2004;363(9410):675–81. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)15640-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nurmohamed MT, Dijkmans BA. Are biologics more effective than classical disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs? Arthritis Res Ther. 2008;10(5):118. doi: 10.1186/ar2491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.van der Velde G, Pham B, Machado M, Ieraci L, Witteman W, Bombardier C, et al. Cost-effectiveness of biologic response modifiers compared to disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs for rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2011;63(1):65–78. doi: 10.1002/acr.20338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schoels M, Wong J, Scott DL, Zink A, Richards P, Landewe R, et al. Economic aspects of treatment options in rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic literature review informing the EULAR recommendations for the management of rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69(6):995–1003. doi: 10.1136/ard.2009.126714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.van der Heijde D, Klareskog L, Rodriguez-Valverde V, Codreanu C, Bolosiu H, Melo-Gomes J, et al. Comparison of etanercept and methotrexate, alone and combined, in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis: two-year clinical and radiographic results from the TEMPO study, a double-blind, randomized trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54(4):1063–74. doi: 10.1002/art.21655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.van Vollenhoven RF, Ernestam S, Geborek P, Petersson IF, Coster L, Waltbrand E, et al. Addition of infliximab compared with addition of sulfasalazine and hydroxychloroquine to methotrexate in patients with early rheumatoid arthritis (Swefot trial): 1-year results of a randomised trial. Lancet. 2009;374(9688):459–66. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60944-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bathon JM, Martin RW, Fleischmann RM, Tesser JR, Schiff MH, Keystone EC, et al. A comparison of etanercept and methotrexate in patients with early rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2000;343(22):1586–93. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200011303432201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Arnett FC, Edworthy SM, Bloch DA, McShane DJ, Fries JF, Cooper NS, et al. The American Rheumatism Association 1987 revised criteria for the classification of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis & Rheumatism. 1988;31(3):315–24. doi: 10.1002/art.1780310302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.van der Heijde D, Klareskog L, Boers M, Landewe R, Codreanu C, Bolosiu HD, et al. Comparison of different definitions to classify remission and sustained remission: 1 year TEMPO results. Ann Rheum Dis. 2005;64(11):1582–7. doi: 10.1136/ard.2004.034371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aletaha D, Landewe R, Karonitsch T, Bathon J, Boers M, Bombardier C, et al. Reporting disease activity in clinical trials of patients with rheumatoid arthritis: EULAR/ACR collaborative recommendations. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;59(10):1371–7. doi: 10.1002/art.24123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.van der Heijde D. How to read radiographs according to the Sharp/van der Heijde method. J Rheumatol. 1999;26(3):743–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.van der Heijde D, Klareskog L, Landewe R, Bruyn GA, Cantagrel A, Durez P, et al. Disease remission and sustained halting of radiographic progression with combination etanercept and methotrexate in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56(12):3928–39. doi: 10.1002/art.23141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Laird NM, Ware JH. Random-effects models for longitudinal data. Biometrics. 1982;38(4):963–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Smolen JS, Aletaha D, Grisar JC, Stamm TA, Sharp JT. Estimation of a numerical value for joint damage-related physical disability in rheumatoid arthritis clinical trials. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69(6):1058–64. doi: 10.1136/ard.2009.114652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.