Abstract

We herein present the case of a 77-year-old man who had fever and right hypochondriac pain. He visited his doctor and underwent contrast computed tomography (CT), and he was suspected to have a liver abscess. He received an antibiotic treatment and his symptoms soon disappeared, but the tumor did not get smaller and its density on contrast CT image got stronger. He underwent biopsy and moderately differentiated hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) was found. Extended left hepatic and caudate lobectomy was performed. Histological examination showed moderately differentiated HCC with narrowing and occlusion both in the arteries and portal veins associated with mild chronic inflammation. The mechanisms of spontaneous regression of HCC, such as immunological reactions and tumor hypoxia, have been proposed. In our case, histological examination showed the same findings. However, the mechanism is complex, and therefore further investigations are essential to elucidate it.

Key words: Spontaneous necrosis, Hepatocellular carcinoma, Alcoholic liver disease, Hepatectomy

Introduction

Spontaneous necrosis or regression of malignant tumors has been reported mainly in neuroblastoma, renal cell carcinoma, malignant melanoma, malignant lymphoma and leukemia [1]. It is a rare event occurring with a rate of 1 in 60,000–100,000 tumors [2] and has also been reported in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). In 1972, spontaneous regression of HCC was first described in a 3-year-old girl who had developed biopsy-proven HCC while on chronic androgen-anabolic steroid treatment for aplastic anemia [3]. Since this initial report, several mechanisms have been suggested to explain the etiology of spontaneous regression of HCC, including the administration of herbal remedies [4, 5] or the withdrawal of a possible causative agent such as alcohol [6], tobacco [5] or exogenous androgens [3, 7]. In spite of various opinions, its mechanism is unclear and there have been few reports with evidence based on a scientific basis, such as radiological findings and histological examinations.

Here we report a case of spontaneous massive necrosis of HCC with various histological examinations of narrowing and occlusion in the arteries and portal veins, and review the literature with special reference to its pathological findings.

Case Report

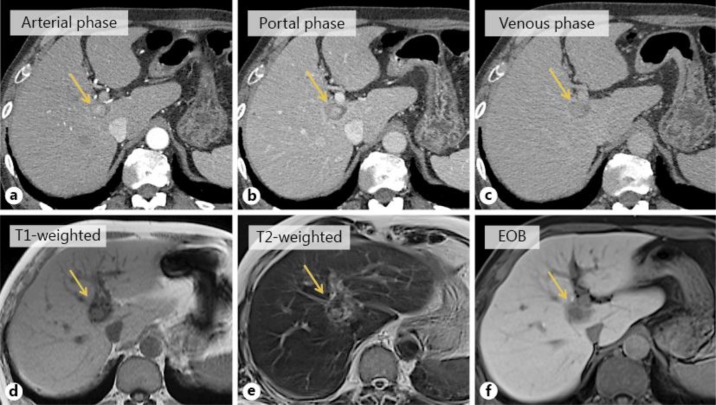

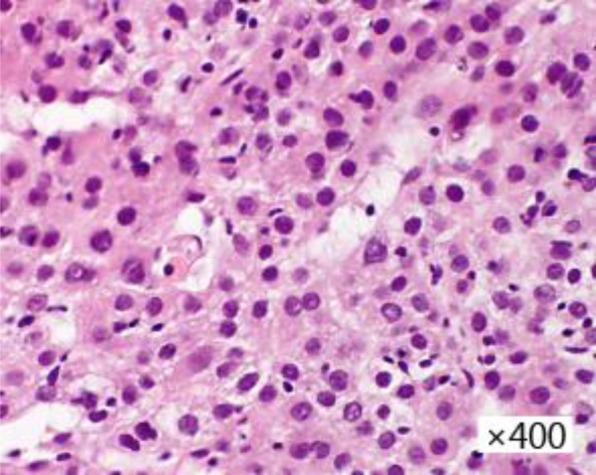

A 77-year-old man, who had alcoholic liver damage, had a fever and right hypochondriac pain. He underwent ultrasonography and contrast computed tomography (CT). Ultrasonography showed a heterogeneous liver mass in the caudate lobe of the liver with a diameter of approximately 3 cm that had a hyper- and a hypoechoic area. Contrast CT showed the tumor to have a ring enhancement area and a high- to low-density round area (fig. 1a–c). These imaging studies indicated a liver abscess, and the patient received an antibiotic treatment, whereupon his symptoms soon improved. One month later, he underwent contrast CT again; the tumor had not shrunk, and moreover its density had become stronger. Therefore, he was suspected to have a liver tumor such as metastatic liver tumor. His gastrointestinal tract was checked by esophagogastroduodenoscopy and colonoscopy, but his doctor could not reveal the primary site. Moreover, his doctor performed positron emission tomography-CT (PET-CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). PET-CT showed no increased fluorodeoxyglucose uptake. The T1-weighted image showed a high-intensity round area in a low-intensity area, the T2-weighted image showed a high-intensity round area in a low-intensity area, and gadoxetic acid-enhanced MRI showed a slightly contrasted low-intensity area in the same segment (fig. 1d–f). Finally, his doctor performed a biopsy of the tumor. Cellular and structural atypia, enlarged hyperchromatic nuclei and two or three layers of trabecular pattern, which indicated moderately differentiated HCC, were found in the specimen (fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

a–c CT findings. Contrast CT showed the tumor to have a ring enhancement area in the caudate lobe of the liver and a high- to low-density round area was shown in the internal part of the tumor. Arrows indicate the tumor. d–f MRI findings. The T1-weighted image showed a high-intensity round area in a low-intensity round area, the T2-weighted image showed a high-intensity round area in a low-intensity round area, and gadoxetic acid-enhanced MRI (EOB) showed a slightly contrasted low-intensity area in the caudate lobe of the liver. Arrows indicate the tumor.

Fig. 2.

Biopsy finding. Cellular and structural atypia, enlarged hyperchromatic nuclei and two or three layers of trabecular pattern, which indicated moderately differentiated HCC, were found in the specimen.

Consequently, the patient was sent to us for surgical treatment. His blood test data before surgical treatment were as follows: white blood cell count 3,470/μl (normal 3,500–9,000/μl), red blood cell count 380 × 104/μl (normal 450–550 × 104/μl), serum hemoglobin concentration 13.1 g/dl (normal 14–18 g/dl), serum platelet count 15 × 104/μl (normal 14–44 × 104/μl), serum aspartate aminotransferase 39 IU/l (normal 13–33 IU/l), serum alanine aminotransferase 24 IU/l (normal 6–30 IU/l), serum alkaline phosphatase 199 IU/l (normal 115–359 IU/l), serum gamma glutamic transpeptidase 304 IU/l (normal 10–47 IU/l), total serum bilirubin 0.9 mg/dl (normal 0.3–1.2 mg/dl), serum albumin 3.7 g/dl (normal 4.0–5.0 g/dl), and serum C-reactive protein 0.03 mg/dl (normal <0.1 mg/dl). The serum concentration of proteins induced by vitamin K antagonism or absence (PIVKA-II) was 19 mAU/ml (normal <40 mAU/ml), and that of alpha-fetoprotein was 5.6 ng/ml (normal <6.2 ng/ml), carcinoembryonic antigen was 8.6 ng/ml (normal <3.2 ng/ml), and carbohydrate antigen 19-9 was 27.5 U/ml (normal <37.0 U/ml). The indocyanine green clearance rate at 15 min was 9.5% (normal <10%). Hepatis B surface antigen and hepatitis C virus antibody were negative. The Child-Pugh classification of his liver belonged to category A.

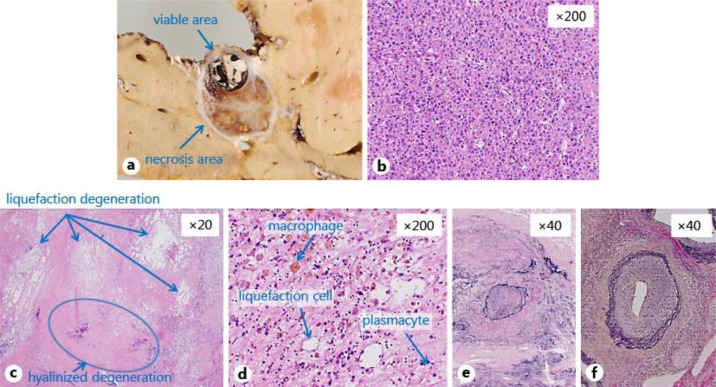

Extended left hepatic and caudate lobectomy was performed 18 days after the biopsy. The tumor consisted of viable and necrosis areas with well-demarcated nodular lesions in the caudate lobe (S1). The viable tumor size was 11 mm in diameter (fig. 3a). Histological examination showed a trabecular and pseudo-glandular structure with enlarged nuclei and hyperchromatins, which indicated moderately differentiated HCC in the viable area (fig. 3b). The necrosis area consisted of sclerotic fibrous stroma and liquefaction, and hyalinized degeneration with hemosiderin-laden macrophages, plasmacytes and fibroblasts was found (fig. 3c, d). Vessel occlusion with organization (fig. 3e), stenotic arteries with wall thickness (fig. 3f) and mild chronic inflammation in fibrously enlarged portal areas were found in the necrotic area. The non-cancerous area of his liver showed mild chronic inflammatory infiltrate in the bridging fibrosis. Mallory-Denk bodies and ballooning were seen in the non-cancerous area.

Fig. 3.

Macroscopic and pathological finding of the resected specimen. a The tumor consisted of viable and necrosis areas with well-demarcated nodular lesions at the caudate lobe (S1). The viable tumor size was 11 mm in diameter. b Histological examination showed a trabecular and pseudo-glandular structure with enlarged nuclei and hyperchromatins, which indicated moderately differentiated HCC in the viable area. c, d The necrosis area consisted of sclerotic fibrous stroma and liquefaction (arrows), and hyalinized degeneration (arrow) with hemosiderin-laden macrophages, plasmacytes and fibroblasts was found. e, f Vessel occlusion with organization (e), stenotic arteries with wall thickness (f) and mild chronic inflammation in fibrously enlarged portal areas were found in the necrotic area.

The patient's postoperative course was uneventful. He is presently doing well and has no sign of any recurrent tumor 7 months after the operation.

Discussion

Spontaneous regression among patients with HCC was reported to happen in 0.4% [8]. Up to date, many spontaneous regressions of HCC have been described and various mechanisms have been proposed.

First, it has been proposed that immunological reactions may bring about the tumor regression [9]. For example, biopsy [9] and fever [10] might trigger immunological reactions and bring about tumor regression. Several reports documented the presence of elevated cytokine levels, suggesting a systemic inflammatory response. Abiru et al. [11] noted elevated IL-18 in three patients with regression of HCC. IL-18 has been shown to induce interferon gamma production by T cells and natural killer cells, thus potentially producing enhanced cytotoxic activity targeted at cancer cells. Jozuka et al. [12] proposed a similar mechanism after detecting elevated levels of natural killer cell activity, IL-2, IL-6, IL-12 and interferon gamma throughout the course of the patient's spontaneous regression.

Second, the current analysis revealed multiple patients in whom regression appeared to be associated with tumor hypoxia [9]. Several occurrences were related to occlusion of either the hepatic artery or the portal vein, which probably led to a direct ischemic insult. Other patients experienced profound systemic hypoperfusion, such as sustained hypotension associated with a massive variceal bleed. Tumor hypoxia as a mechanism is intuitively appealing in that it mirrors established treatment modalities for HCC. For example, both hepatic artery embolization and the agent sorafenib can be considered to rely upon the induction of tumor hypoxia for their effect [13].

Most cases of spontaneous regression of HCC were diagnosed by radiological findings. On the other hand, histological examination was performed only in 24 cases (summarized in table 1). Almost all reports only mentioned the tissue type of HCC, and few reports mentioned detailed histological examination. For example, 11 reports showed the findings of inflammatory cell infiltration, 3 reports arterial thrombosis, 2 reports portal vein thrombosis and 1 report hepatic venous thrombosis.

Table 1.

Previous reports of spontaneous regression of HCC with histological examination

| First author | Year | Age | Sex | Staining method | Histological finding | Proposed mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Andreola [17] | 1987 | 75 | M | HE, PAS, Masson's trichrome, Weigert, immunostaining | complete necrosis, venous thrombosis | venous thrombosis |

| Mochizuki [18] | 1991 | 61 | M | unknown | partial necrosis | radiation for another cancer |

| Imaoka [19] | 1994 | 65 | M | HE | partial necrosis, arterial thrombosis | arterial thrombosis |

| Ozeki [20] | 1996 | 69 | F | unknown | complete necrosis | herbal medicine |

| Markovic [21] | 1996 | 62 | M | unknown | complete necrosis | biological effects by cytokines |

| Stoelben [10] | 1998 | 56 | M | HE | partial necrosis | biological effects triggered by infection |

| Stoelben [10] | 1998 | 74 | M | HE | partial necrosis | biological effects triggered by infection |

| Izuishi [22] | 2000 | 50 | M | HE, reticulin silver | complete necrosis | ischemia or immune response |

| Uenishi [23] | 2000 | 65 | M | HE | partial coagulative necrosis surrounded by inflammatory cells, portal vein thrombosis | portal vein thrombosis |

| Matsuo [24] | 2001 | 72 | M | HE, reticulin silver | complete necrosis, severe inflammatory cell infiltration | tumor hypoxia or immune response |

| Morimoto [25] | 2002 | 73 | M | unknown | complete necrosis, arterial thrombosis | arterial thrombosis |

| Iiai [26] | 2003 | 69 | M | HE | complete necrosis | portal vein tumor thrombosis, discontinuation of smoking |

| Li [27] | 2003 | 53 | M | unknown | complete necrosis, growth of the connective tissue with lymphocyte | biological effects by cytokines |

| Blondon [28] | 2004 | 64 | M | unknown | partial necrosis | immune response, intraperitoneal spread of tumor |

| Blondon [28] | 2004 | 70 | F | unknown | partial necrosis | immune response, intraperitoneal spread of tumor, tamoxifen |

| Ohta [29] | 2005 | 74 | M | HE, reticulin silver | complete coagulative necrosis, inflammatory cell infiltration, arterial thickening and thrombosis | immune response, tumor hypoxia (arterial sclerosis) |

| Ohtani [30] | 2005 | 69 | M | HE | complete necrosis, inflammatory cell infiltration | tumor hypoxia (a thick capsule) |

| Yano [31] | 2005 | 71 | F | HE, Weigert | partial coagulative necrosis, inflammatory cell infiltration | tumor hypoxia |

| Meza-Junco [32] | 2007 | 56 | F | HE | complete necrosis | tumor hypoxia (a thick capsule) |

| Arakawa [33] | 2008 | 78 | F | HE | complete necrosis, inflammatory cell infiltration | portal vein tumor thrombosis, immune response |

| Park [34] | 2009 | 57 | M | HE, streptavidin-biotin complex | partial necrosis, severe inflammatory cell infiltration | infiltrating lymphocyte |

| Hsu [35] | 2009 | 66 | M | HE | partial coagulative necrosis, tumor thrombosis of the right posterior branch of the portal vein | tumor hypoxia, immune response, silymarin |

| Storey [36] | 2011 | 52 | M | HE | complete necrosis, inflammatory cell infiltration | abstinence from alcohol |

| Sasaki [37] | 2013 | 79 | M | HE, immunological staining using a monoclonal antibody against CD68 | partial necrosis | unclear |

| This report | 2014 | 77 | M | HE | partial necrosis, inflammatory cell infiltration, narrowing and occlusion in the arteries and portal veins | tumor hypoxia, fever, biopsy |

HE = Hematoxylin and eosin staining; PAS = periodic acid-Schiff stain.

In our case, the patient had a fever and biopsy. Histological examination showed various findings of inflammatory cell infiltration in the specimen, narrowing and occlusion in the arteries and portal veins, and liquefaction and hyalinized degeneration of the tumor. This seems to be the first report of spontaneous necrosis of HCC having all of these various histological findings together. It was suggested that fever and biopsy were the triggers of the necrosis, and these suspected triggers would bring about the narrowing and occlusion in the arteries and portal veins. Inflammatory cell infiltration was also found, but it was not so dominant. Therefore, we suspected that inflammatory cell infiltration was not the cause, but the result of the degeneration of this case.

On the other hand, it is possible to think that the fever and right hypochondriac pain were not the cause, but the result of the spontaneous necrosis of HCC. Thickening of the vessel wall intima caused tumor hypoxia, which in turn caused the degeneration of HCC, and the patient felt a fever and right hypochondriac pain at that moment. Considering that thickening of the vessel wall intima and portal vein thrombosis were confined to the tumor area, cytokines produced in the tumor cells may relate to thickening of the vessel wall intima and thrombus formation. For example, tumor growth factor beta accelerates thickening of the vessel wall intima [14] and promotes production of plasminogen activator inhibitor-1, which leads to thrombus formation [15, 16].

According to previous reports, including ours, it is sure that the mechanism of the spontaneous regression of HCC, just as that of other tumor regression, is complex. Therefore further findings, particularly concerning the progress of the immunological status during tumor regression and detailed histological examinations, will be essential to elucidate the mechanism of spontaneous regression of HCC.

Disclosure Statement

The authors have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Papac RJ. Spontaneous regression of cancer. Cancer Treat Rev. 1996;22:395–423. doi: 10.1016/s0305-7372(96)90023-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cole WH. Efforts to explain spontaneous regression of cancer. J Surg Oncol. 1981;17:201–209. doi: 10.1002/jso.2930170302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Johnson FL, Lerner KG, Siegel M, Feagler JR, Majerus PW, Hartmann JR, Thomas ED. Association of androgenic-anabolic steroid therapy with development of hepatocellular carcinoma. Lancet. 1972;2:1273–1276. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(72)92649-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chien RN, Chen TJ, Liaw YF. Spontaneous regression of hepatocellular carcinoma. Am J Gastroenterol. 1992;87:903–905. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kato H, Nakamura M, Muramatsu M, Orito E, Ueda R, Mizokami M. Spontaneous regression of hepatocellular carcinoma: two case reports and a literature review. Hepatol Res. 2004;29:180–190. doi: 10.1016/j.hepres.2004.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gottfried EB, Steller R, Paronetto F, Lieber CS. Spontaneous regression of hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology. 1982;82:770–774. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McCaughan GW, Bilous MJ, Gallagher ND. Long-term survival with tumor regression in androgen-induced liver tumors. Cancer. 1985;56:2622–2626. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19851201)56:11<2622::aid-cncr2820561115>3.0.co;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Oquiñena S, Guillen-Grima F, Iñarrairaegui M, Zozaya JM, Sangro B. Spontaneous regression of hepatocellular carcinoma: a systematic review. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;21:254–257. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e328324b6a2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huz JI, Melis M, Sarpel U. Spontaneous regression of HCC is most often associated with tumor hypoxia or systemic inflammatory response. HPB (Oxford) 2012;14:500–505. doi: 10.1111/j.1477-2574.2012.00478.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stoelben E, Koch M, Hanke S, Lossnitzer A, Gaertner HJ, Schentke KU, Bunk A, Saeger HD. Spontaneous regression of hepatocellular carcinoma confirmed by surgical specimen: report of two cases and review of the literature. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 1998;383:447–452. doi: 10.1007/s004230050158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abiru S, Kato Y, Hamasaki K, Nakao K, Nakata K, Eguchi K. Spontaneous regression of hepatocellular carcinoma associated with elevated levels of interleukin 18. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:774–775. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.05580.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jozuka H, Jozuka E, Suzuki M, Takeuchi S, Takatsu Y. Psycho-neuro-immunological treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma with major depression – a single case report. Curr Med Res Opin. 2003;19:59–63. doi: 10.1185/030079902125001362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xie B, Wang DH, Spechler SJ. Sorafenib for treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma: a systematic review. Dig Dis Sci. 2012;57:1122–1129. doi: 10.1007/s10620-012-2136-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kanzaki T, Shiina R, Saito Y, Oohashi H, Morisaki N. Role of latent TGF-beta 1 binding protein in vascular remodeling. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998;246:26–30. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.8559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pedroja BS, Kang LE, Imas AO, Carmeliet P, Bernstein AM. Plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 regulates integrin alphavbeta3 expression and autocrine transforming growth factor beta signaling. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:20708–20717. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.018804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Christ G, Hufnagl P, Kaun C, Mundigler G, Laufer G, Huber K, Wojta J, Binder BR. Antifibrinolytic properties of the vascular wall. Dependence on the history of smooth muscle cell doublings in vitro and in vivo. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1997;17:723–730. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.17.4.723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Andreola S, Audisio RA, Mazzaferro V, Doci R, Milella M. Spontaneous massive necrosis of a hepatocellular carcinoma. Tumori. 1987;73:203–207. doi: 10.1177/030089168707300220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mochizuki T, Takehara Y, Nishimura T, Takahashi M, Kaneko M. Regression of hepatocellular carcinoma. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1991;156:868–869. doi: 10.2214/ajr.156.4.1848389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Imaoka S, Sasaki Y, Masutani S, Ishikawa O, Furukawa H, Kabuto T, Kameyama M, Ishiguro S, Hasegawa Y, Koyama H, et al. Necrosis of hepatocellular carcinoma caused by spontaneously arising arterial thrombus. Hepatogastroenterology. 1994;41:359–362. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ozeki Y, Matsubara N, Tateyama K, Kokubo M, Shimoji H, Katayama M. Spontaneous complete necrosis of hepatocellular carcinoma. Am J Gastroenterol. 1996;91:391–392. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Markovic S, Ferlan-Marolt V, Hlebanja Z. Spontaneous regression of hepatocellular carcinoma. Am J Gastroenterol. 1996;91:392–393. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Izuishi K, Ryu M, Hasebe T, Kinoshita T, Konishi M, Inoue K. Spontaneous total necrosis of hepatocellular carcinoma: report of a case. Hepatogastroenterology. 2000;47:1122–1124. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Uenishi T, Hirohashi K, Tanaka H, Ikebe T, Kinoshita H. Spontaneous regression of a large hepatocellular carcinoma with portal vein tumor thrombi: report of a case. Surg Today. 2000;30:82–85. doi: 10.1007/PL00010054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Matsuo R, Ogata H, Tsuji H, Kitazono T, Shimada M, Taguchi K, Fujishima M. Spontaneous regression of hepatocellular carcinoma – a case report. Hepatogastroenterology. 2001;48:1740–1742. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Morimoto Y, Tanaka Y, Itoh T, Yamamoto S, Mizuno H, Fushimi H. Spontaneous necrosis of hepatocellular carcinoma: a case report. Dig Surg. 2002;19:413–418. doi: 10.1159/000065822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Iiai T, Sato Y, Nabatame N, Yamamoto S, Makino S, Hatakeyama K. Spontaneous complete regression of hepatocellular carcinoma with portal vein tumor thrombus. Hepatogastroenterology. 2003;50:1628–1630. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li AJ, Wu MC, Cong WM, Shen F, Yi B. Spontaneous complete necrosis of hepatocellular carcinoma: a case report. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2003;2:152–154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Blondon H, Fritsch L, Cherqui D. Two cases of spontaneous regression of multicentric hepatocellular carcinoma after intraperitoneal rupture: possible role of immune mechanisms. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;16:1355–1359. doi: 10.1097/00042737-200412000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ohta H, Sakamoto Y, Ojima H, Yamada Y, Hibi T, Takahashi Y, Sano T, Shimada K, Kosuge T. Spontaneous regression of hepatocellular carcinoma with complete necrosis: case report. Abdom Imaging. 2005;30:734–737. doi: 10.1007/s00261-005-0313-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ohtani H, Yamazaki O, Matsuyama M, Horii K, Shimizu S, Oka H, Nebiki H, Kioka K, Kurai O, Kawasaki Y, Manabe T, Murata K, Matsuo R, Inoue T. Spontaneous regression of hepatocellular carcinoma: report of a case. Surg Today. 2005;35:1081–1086. doi: 10.1007/s00595-005-3066-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yano Y, Yamashita F, Kuwaki K, Fukumori K, Kato O, Kiyomatsu K, Sakai T, Yamamoto H, Yamasaki F, Ando E, Sata M. Partial spontaneous regression of hepatocellular carcinoma: a case with high concentrations of serum lens culinaris agglutinin-reactive alpha fetoprotein. Kurume Med J. 2005;52:97–103. doi: 10.2739/kurumemedj.52.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Meza-Junco J, Montaño-Loza AJ, Martinez-Benítez B, Cabrera-Aleksandrova T. Spontaneous partial regression of hepatocellular carcinoma in a cirrhotic patient. Ann Hepatol. 2007;6:66–69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Arakawa Y, Mori H, Ikegami T, Hanaoka J, Kanamoto M, Kanemura H, Morine Y, Imura S, Shimada M. Hepatocellular carcinoma with spontaneous regression: report of the rare case. Hepatogastroenterology. 2008;55:1770–1772. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Park HS, Jang KY, Kim YK, Cho BH, Moon WS. Hepatocellular carcinoma with massive lymphoid infiltration: a regressing phenomenon? Pathol Res Pract. 2009;205:648–652. doi: 10.1016/j.prp.2009.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hsu CY, Sun PL, Chang HC, Perng DS, Chen YS. Spontaneous regression of advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: a case report. Cases Journal. 2009;2:6251. doi: 10.4076/1757-1626-2-6251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Storey RE, Huerta AL, Khan A, Laber DA. Spontaneous complete regression of hepatocellular carcinoma. Med Oncol. 2011;28:948–950. doi: 10.1007/s12032-010-9562-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sasaki T, Fukumori D, Yamamoto K, Yamamoto F, Igimi H, Yamashita Y. Management considerations for purported spontaneous regression of hepatocellular carcinoma: a case report. Case Rep Gastroenterol. 2013;7:147–152. doi: 10.1159/000350501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]