Abstract

Objective

Ecological momentary assessment (EMA) methods have provided a rich assessment of the contextual factors associated with a wide range of behaviors including alcohol use, eating, physical activity, and smoking. Despite this rich database, this information has not been linked to specific locations in space. Such location information, which can now be easily acquired from global positioning system (GPS) tracking devices, could provide unique information regarding the space-time distribution of behaviors and new insights into their determinants. In a proof of concept study, we assessed the acceptability and feasibility of acquiring and combining EMA and GPS data from adult smokers with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).

Methods

Participants were adults with ADHD who were enrolled in a larger EMA study on smoking and psychiatric symptoms. Among those enrolled in the latter study who were approached to participate (N = 11), 10 consented, provided daily EMA entries, and carried a GPS device with them during a 7-day assessment period to assess aspects of their smoking behavior.

Results

The majority of those eligible to participate were willing to carry a GPS device and signed the consent (10 out of 11, 91%). Of the 10 who consented, 7 participants provided EMA entries and carried the GPS device with them daily for at least 70% of the sampling period. Data are presented on the spatial distribution of smoking episodes and ADHD symptoms on a subset of the sample to demonstrate applications of GPS data.

Conclusions

We conclude by discussing how EMA and GPS might be used to study the ecology of smoking and make recommendations for future research and analysis.

Keywords: global positioning system, geographic information system, ecological momentary assessment, nicotine dependence, smoking, ADHD

Cigarette smoking accounts for 400,000 premature deaths in the U.S. and costs $150 billion annually (Centers for Disease Control, 2002; Ezzati & Lopez, 2003). Smoking is twice as likely in persons with a psychiatric disorder (Lasser et al., 2000; McClernon, Calhoun, Hertzberg, Dedert, & Beckham, in press), which makes studying individuals with this comorbidity particularly worthwhile. Great strides have been made in the last 20 years in determining the contextual determinants of smoking and other detrimental behaviors by surveying participants in their environments using ecological momentary assessment (EMA). EMA has enhanced traditional substance use research methods by assessing substance use behavior in the moment. Since substance use is episodic and related to mood and context, EMA is particularly well-suited for assessment in this domain (Shiffman, 2009).

Whereas EMA has provided insights into the contextual determinants of behavior, location in EMA research has often been conceptualized broadly (e.g., at home, at school) without links to actual geographic location. Knowledge of the actual geographic location of substance use behaviors could provide unique insights into their determinants or maintaining variables. In this proof of concept study, we present novel methods for the simultaneous acquisition of EMA and global positioning system (GPS) data to assess smoking behavior in people with a psychiatric diagnosis.

EMA Research

EMA provides real-time information in natural environments and allows for detailed temporal analysis of specific behaviors across contexts (Shiffman et al., 2002). EMA addresses limitations of traditional assessment techniques (e.g., repeated assessment in one's daily environment, thereby enhancing ecological validity) (Csikszentmihalyi & Larson, 1987; deVries, 1992; Ferguson & Shiffman, 2011; Reis & Gable, 2000), allows for time-stamped entries to ensure they are made at the requested times, has lockout capabilities to ensure confidentiality, and disallows respondents from making multiple entries to retrospectively enter data. See Shiffman, Stone, and Hufford (2008) for a review of EMA construct validity when considering smoking.

GPS and Activity Space

Geographic features, both built (e.g., density of fast food restaurants) and social (e.g., socioeconomic status of a neighborhood) have increasingly been considered in relation to a variety of health-related behaviors. For example, geographic aspects of residential settings are associated with higher levels of smoking (e.g., convenience store concentration) (Chuang, Cubbin, Ahn, & Winkleby, 2005). Although geographic features have traditionally been considered static characteristics of a residential area (Feng, Glass, Curriero, Stewart, & Schwartz, 2010; Leal & Chaix, 2011), people regularly engage in daily routines outside of their fixed residential settings (U.S. Census Bureau, 2010). Examination of an individual's daily activity space, which refers to the geometric space a person occupies or travels to over a period of time (Golledge & Stimson, 1997), may provide a more accurate assessment of day-to-day activities and how people allocate their time spatially (Flamm & Kaufmann, 2006; Zenk et al., 2011).

Using GPS to examine the spatial and temporal relationships with cigarette smoking behavior may aid in understanding environmental causal and maintenance factors in real-world conditions. Knowing the specific locations in which smoking or smoking urges occur might provide more detailed information regarding contextual influences on smoking behavior. Moreover, analysis of GPS and smoking data may elucidate meaningful individual differences in how smokers allocate their smoking behavior across time and space.

The Present Study

The goals of the present study were to (a) develop methods for and (b) assess the acceptability and feasibility of collecting and analyzing combined EMA and GPS data in a sample of adult smokers diagnosed with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Given that smoking is about twice as likely in adults with ADHD (see McClernon & Kollins, 2008, for a review), smokers with ADHD were targeted in the current study and served as a prototype sample for application to other groups with nicotine dependence and a psychiatric disorder. Although a recent study has demonstrated that GPS technology is feasible for measuring psychiatric disorder symptoms, participants were predominantly healthy and without clinically significant psychiatric symptoms (Prociow, Wac, & Crowe, 2012).

In this proof of concept analysis, we demonstrate for the first time that EMA and GPS data can be combined to provide novel insights into the spatial distribution of typical daily smoking behavior. While EMA has a longstanding history as a methodological approach to investigate smoking behavior, the incorporation of GPS has yet to be assessed and therefore is the primary focus of this study. To our knowledge, this is one of the first studies to utilize GPS in a sample composed of participants with a psychiatric diagnosis.

Methods

Participants

Participants (N = 10) were recruited from a larger study assessing aspects of smoking behavior, affect, and psychiatric symptoms using EMA in a sample of adults with diagnosed ADHD (see Mitchell et al., submitted, for additional details). Participants were recruited for the larger study from the community via advertisements, word of mouth, and referrals from local clinics. Seventeen participants were included in the larger study, although 11 were approached to participate in the current study given the timing in which GPS devices were procured. Therefore, all participants who were eligible to participate were approached for this study. Those eligible for both the present and larger study were aged 18-50 years; met DSM-IV criteria for ADHD; smoked 10 or more cigarettes per day of a brand delivering 0.5mg or more nicotine per cigarette; provided afternoon expired carbon monoxide (CO) concentrations of 10ppm or more; displayed intellectual functioning of 80 or higher as assessed by an IQ screener; and were generally healthy (i.e., no major medical problems). Individuals who met criteria for DSM-IV Axis I disorders other than ADHD or nicotine dependence; had current illicit substance use; were unable to attend all required experimental sessions; or were female and pregnant or planned on becoming pregnant were not eligible for the study. See Table 1 for a summary of the sample demographics.

Table 1. Summary of Participant Characteristics (N = 10).

| M (SD) | n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 28.80 (10.09) | |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 6 (60%) | |

| Female | 4 (40%) | |

| Race | ||

| White | 7 (70%) | |

| Black | 2 (20%) | |

| Native American | 1 (10%) | |

| KBIT | 110.00 (16.77) | |

| FTND | 4.90 (1.45) | |

| CO reading (ppm) | 19.70 (12.07) | |

| Cigarettes per day | 14.80 (4.71) | |

| CAARS Total DSM-IV ADHD Symptoms (raw score) | 34.50 (7.55) |

Note. KBIT = Kaufman Brief Intelligence Test, Second Edition, FTND = Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence, CO reading (ppm) = expired carbon monoxide concentrations (parts per million), CAARS = Conners' Adult ADHD Rating Scale (self-reported raw scores).

Participants who consented to the larger EMA study were invited to participate in the current study. Researchers provided a full description of the study, explaining that it involved carrying a GPS device for seven days while providing daily electronic diary entries. Participants did not receive any incentives for participating in the portion of the study involving the GPS device and were told so during the consent process. After all aspects of the study were discussed, those who demonstrated an understanding of the study and were interested in participating provided written consent. The study was approved and monitored by the Institutional Review Board for Duke University Medical Center.

Materials and Procedures

Screening measures

Following informed consent, demographic information as well as medical, psychiatric, smoking, and substance use histories were collected. Baseline nicotine dependence was assessed with the Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence (FTND) (Heatherton, Kozlowski, Frecker, & Fagerström, 1991), smoking status was verified by expired CO concentrations, and IQ was assessed by the Kaufman Brief Intelligence Test, Second Edition (Kaufman & Kaufman, 2004). The Conners Adult ADHD Rating Scale - Self-Report (CAARS; Conners, Erhardt, & Sparrow, 1999), followed by the Conners Adult Diagnostic Interview for DSM-IV (CAADID) (Epstein, Johnson, & Conners, 2000) was used to assess full ADHD diagnostic criteria, and Axis I disorders were assessed with the computerized Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID; First, Spitzer, Williams, & Gibbon, 2002) with a follow-up clinical interview administered by a PhD-level clinical psychologist.

EMA

Participants attended a one-hour training session in use of the handheld electronic diary. Following training, participants carried an electronic diary with them for the remainder of the day to practice responding to diary prompts and providing entries for each cigarette smoked. Afterwards they returned to the laboratory and received feedback regarding their mastery of the electronic diary. Upon completing this one-day practice period, participants were scheduled to begin a 7-day sampling period in which they carried the diaries with them. Participants provided the following type of EMA ratings: (a) prompted alarm entries to assess behavior when not smoking and (b) self-initiated entries (immediately prior to and following smoking occasions) to assess behavior in the context of smoking. Participants were asked to smoke as they typically do—there were no requests to change any aspects of their smoking behavior. For the purposes of this study we primarily considered self-initiated entries.

Participants initiated electronic diary readings immediately prior to and following every cigarette they smoked (even if they smoked several in a row). We considered urge to smoke immediately prior to and following a smoking episode. Participants responded to “How strong is your urge for a cigarette right now?” on a 1 (“not at all”) to 5 (“extremely”) scale. To reduce participant demands, the diaries were programmed to present full assessments for self-initiated entries approximately five times per day and allowed the remaining assessments to be abbreviated consistent with previous applications of EMA, which included assessment of smoking urge before smoking (Beckham et al., 2008). All full assessment entries were estimated to take 2 to 4 minutes, which also included an assessment of all 18 DSM-IV ADHD symptoms prior to and following smoking (e.g., “To what extent are you currently having difficulty being easily distracted by things going on around you?”). Response options were on a 1 (“not at all”) to 5 (“extremely”) scale. Situational aspects of each reading were assessed as well for full assessment. That is, participants were asked “Where are you?” for each reading and selected one of the following options: Home, Home of Friend/Family, Work, Car/Bus, Bar/Restaurant, Outside, Other location. See Mitchell et al. (submitted) for additional details about EMA assessments for this study. Participants were compensated for completing the larger EMA study ($300) with an additional bonus for not missing more than three alarms per day ($40) and for returning the electronic diary device at the conclusion of the 7-day monitoring period ($30). However, participants did not receive any incentives for participating in the GPS portion of the study and were told so during the consent process.

Daily phone calls were made to each participant to troubleshoot any problems. During the daily phone contacts, study personnel had an EMA device to allow them to look at the same screen as the participant in order to guide them through any EMA technical issues. If this approach was insufficient in solving any EMA problems, the participant was scheduled for an immediate lab visit and compensated an additional $15. This occurred twice in the current study.

GPS

Participants were provided a GPS device to be worn or carried with them at all times during the study. They were also instructed to charge the GPS device every night when they charged the electronic diary. To minimize concerns about forgetting to turn on the device in the morning, participants were asked to keep the GPS device on at all times. Such concerns are particularly relevant for a clinical population characterized by chronic forgetfulness. No incentives were provided for GPS compliance.

Devices

EMA device

EMA questionnaires were designed with Entryware Designer software version 6.3 developed by Techneos Systems, Inc. The electronic diaries were administered on Treo 755P handheld computers. Each EMA entry received a unique time stamp.

GPS device

GPS data were collected using an i-Blue 747A+ data logger developed by TranSystem, Inc. The GPS device was programmed to record location every 15 seconds. GPS data were downloaded using BT747 V2.0.3 software. Accuracy of this device is typically within three meters 95% of the time. In general, signal reception of these devices is improved when outdoors. GPS data accuracy was pilot tested by the authors (i.e., carrying the GPS device for at least a five hour period) to ensure that recorded locations were consistent with actual locations occupied. In addition, for the current study, qualitative EMA assessments of location were recorded as well to consider any inaccurate GPS readings.

GIS Mapping and Analysis

EMA and GPS data were merged, processed, and analyzed using geographical information system (GIS) software (ArcGIS®) and R (R Core Team, 2012), which allow for analysis of spatial and temporal relationships involving environment and behavior (Cromley, 2003; Kistemann, Dangendorf, & Schweikart, 2002; Melnick & Fleming, 1999). EMA-determined time of reported smoking episodes were plotted geographically to the GPS coordinates closest in time (within 15 seconds). GPS data were then merged with EMA data to indicate where participants reported smoking a cigarette.

From the merged EMA and GPS dataset, we calculated summary information on the frequency and location of smoking events. We also calculated the Euclidean distance from home of every recorded location, smoking or otherwise. This was used to explore spatial and temporal variability in each individual's movement and smoking patterns. Since the GPS-recorded locations are spatially explicit, we used the EMA data to assign qualitative labels for location to all smoking events, and we also used the GPS data to differentiate between similar EMA-determined qualitative locations (i.e., when an individual had multiple home or work settings). Finally, given that smokers with ADHD were the sample for this study, we also considered change scores in ADHD symptoms (pre-cigarette ADHD symptoms from post-cigarette ADHD symptoms) as a function of location.

Data Reduction

Spatial distributions of smoking behavior primarily focused on four participants across 72 hour assessment time periods to illustrate how EMA and GPS data can be considered. Consistent with previous application of GPS (Zenk et al., 2011), GPS data was examined within the immediate surrounding area where the study was conducted. Although seven of the 10 participants met our a priori guidelines for total number of daily GPS readings (i.e., >3,200) over at least a three day period, we chose to consider four of them in detail based on the following criteria. First, data from these four participants were informed by reports that movement on those days were typical for each participant (i.e., did not deviate from their typical daily spatial routine). Second, these four participants allowed for a comparison across participants with a similar amount of GPS daily readings (i.e., 3,237 to 5,760 readings per day). Third, the other three participants traveled far outside of the area (e.g., traveled to another state) and indicated that such GPS tracks were uncharacteristic of their typical daily activity space during at least a portion of the assessment period so that analysis of their daily activity patterns was not possible.

Results

GPS Acceptability and Feasibility

In terms of acceptability, among the 11 participants who were offered the GPS tracking portion from the primary study, 1 declined citing concerns about privacy (9% of the sample). Among the 10 people who participated, as indicated above, 70% met our a priori guidelines for total number of daily GPS readings (i.e., >3,200) over at least a three day period.

In terms of overall GPS compliance, 7 of 10 participants carried the GPS device with them daily and provided EMA entries on more than 70% of occasions. However, full daily GPS data for some participants on some days was unavailable for a variety of reasons, including (a) not carrying the GPS device with them for a portion of the day (n = 5 across eight separate days), (b) data collection period not lasting an entire day which resulted in few GPS data points (n = 4; e.g., the participant may have started or ended the EMA portion of the study at mid-day), (c) equipment malfunction (n = 1; i.e., the GPS data logger did not export data points), and (d) GPS data was not downloaded either because participants forgot to charge the GPS device or turned it off or there was a GPS malfunction (n = 5). As a result, GPS data were either not valid or valid on particular days for specific participants. After these considerations were taken into account, a total of seven participants met a priori guidelines for total number of daily GPS readings (i.e., >3,200) over at least a three day period. When we extended this descriptive analysis to examine the total number of participants who met these guidelines across more than three days, the following emerged: at least a four day period (n = 6), a five day period (n = 5), a six day period (n = 5), and a seven day period (n = 4).

EMA and Geographical Assessment of Smoking Behavior

The four participants described below did not differ from the other participants in age, gender, race, CO reading, nicotine dependence severity, or ADHD symptom severity at baseline (see Table 2). A total of three days, including at least two weekdays or two workdays (since some participants worked on weekend days), were included to assess spatial relationships with smoking for each participant. Participants reported smoking a total of 128 cigarettes over the 72-hour observation period, which is approximately 11 cigarettes per day for each participant.

Table 2. Comparison of Participants Selected for Detailed Description vs. Those Not Selected1.

| Participants selected (n = 4) | Participants not selected (n = 6) | Test statistic | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | |||

| Gender (n, %) | ||||

| Male | 2 (50%) | 4 (67%) | χ2 (1) = 0.28 | .60 |

| Female | 2 (50%) | 2 (33%) | ||

| Race (n, %) | ||||

| White | 3 (75%) | 4 (67%) | χ2 (2) = 0.77 | .68 |

| Black | 1 (25%) | 1 (17%) | ||

| Native American | 0 (0%) | 1 (17%) | ||

| M (SD) | M (SD) | |||

| Age | 34.50 (13.92) | 25.00 (4.86) | t (8) = 1.57 | .15 |

| KBIT | 116.25 (17.75) | 105.83 (16.28) | t (8) = 0.96 | .37 |

| FTND | 5.25 (2.22) | 4.67 (0.82) | t (8) = 0.60 | .56 |

| CO reading (ppm) (SD) | 22.00 (18.76) | 18.17 (6.45) | t (8) = 0.47 | .65 |

| Cigarettes per day (SD) | 15.25 (5.50) | 14.50 (4.64) | t (8) = 0.23 | .82 |

| CAARS Total DSM-IV ADHD Symptoms (SD) | 34.75 (8.96) | 34.33 (7.37) | t (8) = 0.08 | .94 |

Note. GPS = global positioning system ; KBIT = Kaufman Brief Intelligence Test, Second Edition, FTND = Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence, CO reading (ppm) = expired carbon monoxide concentrations (parts per million), CAARS = Conners' Adult ADHD Rating Scale (self-reported raw scores)

Only those whose activities during the 72-hour period of data collection were typical of their routine daily activities were selected for detailed analysis.

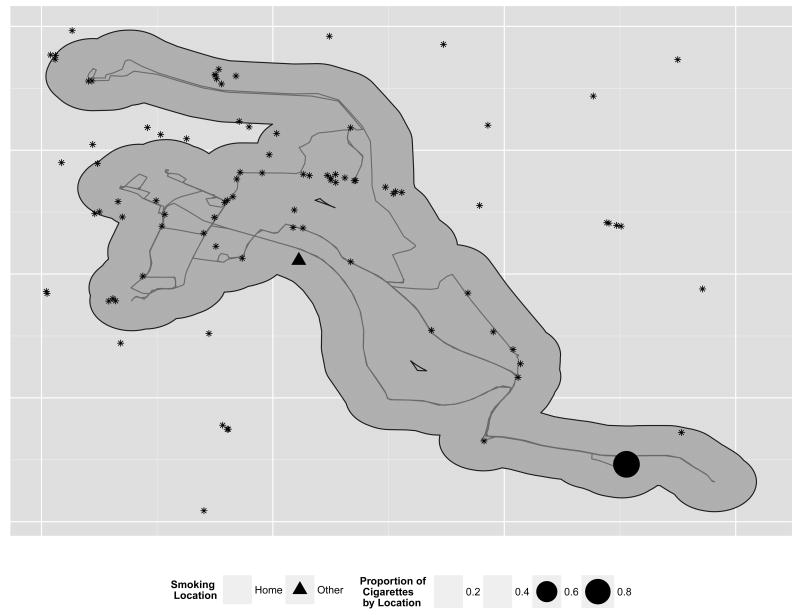

A total of 58,299 GPS data points were acquired across all four participants over the 72-hour observation period. These data points were used to create tracks for each participant, indicating where they traveled over the 72-hour observation period (e.g., see Figure 1 for the track and proportion of cigarettes smoked by location for one participant1). Information on the spatial location (geocoded and ground-truthed) of tobacco retail outlets was available for one county in our area (Rose, Myers, D'Angelo, & Ribisl, in press). Figure 1 superimposes these tobacco outlets and the daily activity path for a single subject who spent the entirety of the 72-hour period in that county. Based on Zenk et al. (2011), a half-mile buffer was calculated for each of the participants GPS data points, and the number of tobacco outlets within that buffer were counted.

Figure 1.

Proportion of cigarettes smoked across different settings. This figure provides spatial data on one subject and shows the distribution of proportion of cigarettes smoked across a three-day period. In addition, tobacco outlets within 0.5 miles are indicated as well.

Visual inspection of GPS plots when participants reported starting to smoke a cigarette for each subject revealed that smoking behavior varied spatially across individual smokers. Table 3 provides an example of the spatial distributions that emerged and the proportion of reported cigarettes smoked at those locations. For instance, Table 3 demonstrates how one participant (#1) smoked primarily at home and to a relatively lesser extent at work, whereas another participant's (#2) smoking episodes varied across different locations. Although participant #2 smoked a higher proportion of cigarettes at home, smoking episodes were also dispersed at two work settings, at the home of a friend or family member, while in a car or bus, and while outside. Overall, smoking was spatially distributed differentially across participants.

Table 3. Proportion of Cigarettes Smoked Based on Location.

| Location | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participant | Car or bus | Home | Home of friend or family | Work | Work 21 | Outside | Other location |

| 1 | 94.2 | 5.8 | |||||

| 2 | 9.1 | 56.8 | 2.4 | 13.6 | 13.6 | 4.5 | |

| 3 | 81.2 | 18.8 | |||||

| 4 | 27.7 | 55.5 | 5.6 | 5.6 | 5.6 | ||

For those who had a second job.

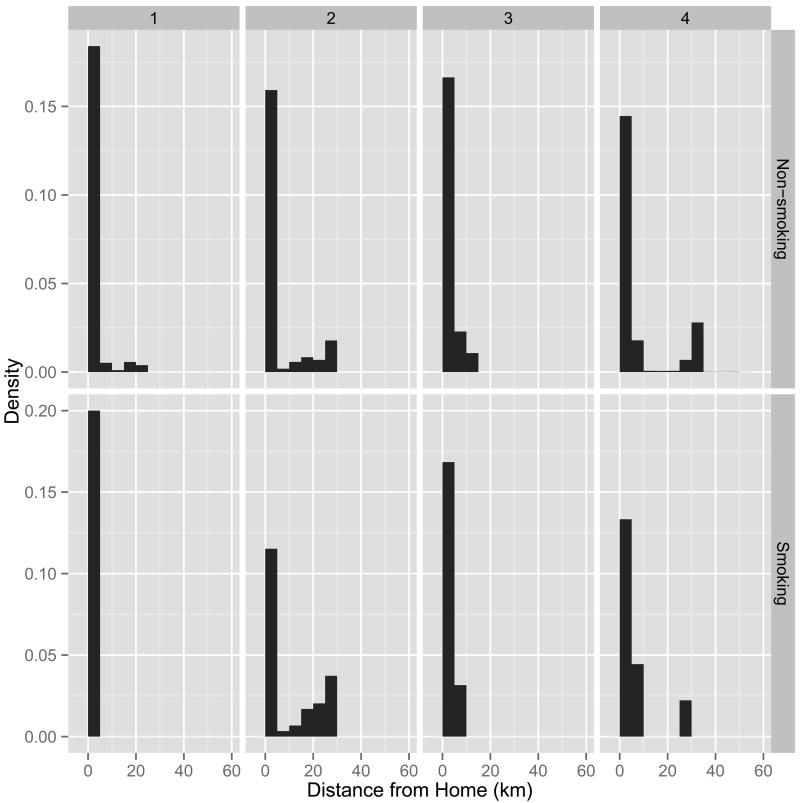

A unique feature of GPS data involves inspection of smoking episodes as a function of distance from home or any other locations. Figure 2 compares the density of locations as a function of distance to home for both non-smoking (top panel) and smoking locations (bottom panel). All individuals spent the majority of their time close to home, and all individuals smoked close to home. However, across individuals there was variation in their locations (both smoking and non-smoking). For example, participant #2 had many locations away from home and was more likely to smoke farther from home, whereas the other three participants did not follow this trend.

Figure 2.

Density of locations, smoking and non-smoking, as a function of distance from home plotted by individual.

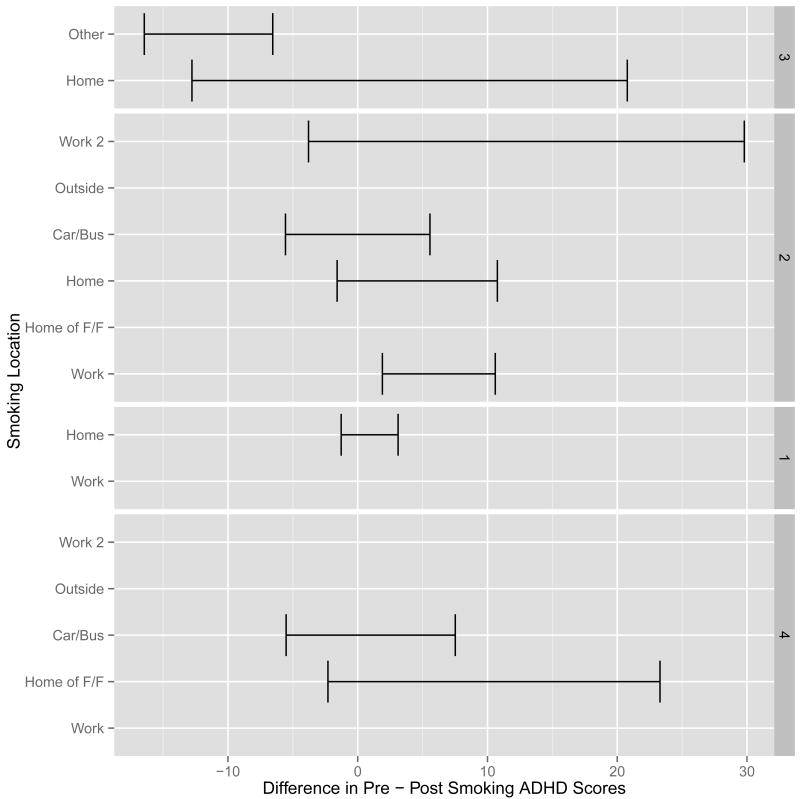

Figure 3 provides a summary of individual participant changes in ADHD symptoms after smoking by location. A higher score indicates a greater improvement in ADHD symptoms after smoking. Improvement in ADHD symptoms after smoking varied across individuals and settings. Most participants reported a greater improvement of ADHD symptoms after smoking at work relative to other settings (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Change in ADHD symptoms (pre-cigarette vs. post-cigarette) across different settings. Standard error bars are included. Any ratings without a standard error bar represent a single ADHD symptom change score in that setting. Home of F/F = Home of Friend or Family. Work 2 = ratings for a second work setting for any participants who held a second job.

Discussion

The current study demonstrates the acceptability, feasibility, and potential of combining EMA with GPS to study cigarette smoking in adults with ADHD. Although EMA has a longstanding history as a methodology to investigate smoking behavior, GPS has yet to be assessed. The current study is the first, to our knowledge, to use GPS to attempt to assess typical daily smoking behavior in a group of adults who are regular smokers and have a psychiatric disorder. Acceptability was high. That is, despite not receiving any incentives for consenting to carry a GPS device and being told that use of the GPS device could be refused without impacting their involvement in the larger EMA study, 91% of those approached to take part in this study participated. In addition, 70% of the sample met a priori guidelines for total number of daily GPS readings (i.e., >3,200) over at least a three-day period. Despite this, some feasibility issues emerged that should be considered for future research, such as forgetting to carry the GPS device for a portion of the day. These are discussed in greater detail below. Further, GIS analysis indicates potential research questions in which combined EMA and GPS assessment can be applied in order to investigate spatial relationships and smoking behavior.

In terms of feasibility, the majority of the sample (i.e., 7 of 10 participants) provided EMA entries and carried the GPS device with them during the entire day over at least 70% of the time. Future studies implementing combined EMA and GPS assessment may want to consider issues that emerged in the current study that may have attenuated compliance with use of GPS. In particular, the following issues emerged: (a) not carrying the GPS device for a portion of the day, (b) data collection period not lasting an entire day, (c) equipment malfunction (i.e., the GPS data logger did not export data points), and (d) GPS data were not downloaded either because of participants forgetting to charge the GPS device, the device was turned off by the participant, or GPS malfunction. To minimize the likelihood of GPS data loss due to these factors and to yield more valid data points, future studies should consider incorporating GPS into EMA via smartphone technology. In the current study, GPS devices were separate and carried independently from EMA devices. In addition, the current study did not provide incentives for GPS compliance (e.g., plugging in the device overnight) or provide materials to assist in carrying the device (e.g., using a wrist worn GPS device), which may also improve compliance in future studies. Also, the sample was composed of adults with ADHD who were not undergoing any active treatment. Given that ADHD is characterized by symptoms such as chronic forgetfulness, difficulty keeping track of things, and disorganization, compliance was likely attenuated as a function of sample type as well.

Future Directions

The main goal of this study was to demonstrate the acceptability and feasibility of linking smoking behavior and EMA with spatial data recorded from GPS. This link provides a foundation for future modeling studies. That is, one potential of combining GPS technology to assess substance use behavior is to create models that may predict substance use as spatial data provide an additional contextual layer to assess behavior. A next step will be to link smoking behavior with spatially explicit covariates extracted from GIS. With such a dataset, we can explore and potentially quantify the links between internal covariates derived from EMA (e.g., self-reported urge to smoke), external covariates derived from GPS/GIS (e.g., proximity to tobacco outlets), and smoking behavior. Movement ecologists have long used such approaches to infer animal behavior as influenced by the environment (Schick et al., 2008). However, unlike some movement ecology studies in which some behaviors of interest cannot be directly observed (e.g., foraging), we have the distinct advantage of self-reported instances of behavior and can now search for explanatory variables.

Additional environmental aspects may also be important variables to consider in relation to various smoking behavior stages (e.g., initiation, maintenance, and cessation) in future research incorporating GPS. Such aspects could include the density of smoking outlets and the proximity of tobacco retailers since residential proximity to tobacco outlets influences smoking cessation (Halonen et al., 2013; Reitzel et al., 2011). Future studies can extend such findings and apply GPS technology to assess whether proximity to tobacco outlets along an individual's daily geographic activity space also plays a role in cessation rates. Additional geocoded factors (e.g., mean socioeconomic status of the surrounding area or bar proximity) may also be included in such applications.

Quantifying these relationships at the individual level may provide information for more personalized and potentially effective intervention. For example, incorporating GPS technology with EMA may be beneficial in identifying idiographic “hot spots” for smoking and craving for those undergoing a smoking cessation attempt. Indeed, physical location is important for clinicians working with individuals attempting to quit smoking. For instance, the environment in which primary drug reinforcement has occurred can trigger drug craving when that context is encountered. According to the renewal effect (Conklin & Tiffany, 2002), extinguishing a response in one context does not generalize to another. Therefore, knowing the specific location in which smoking or smoking urges occur, when combined with information about the local environment, might provide more detailed information regarding the contextual influences on smoking behavior. These can then be used as a component of exposure therapies. Evidence-based interventions delivered via technology-based platforms (e.g., web or mobile phone) can provide immediate access to therapeutic support with high treatment fidelity to substance use samples (Marsch & Dallery, 2012). Such substance use interventions have been shown to enhance traditional treatment techniques (Kiluk, Nich, Babuscio, & Carroll, 2010) or are comparable as a standalone intervention (Bickel, Christensen, & Marsch, 2011). GPS methods can also be applied to additional forms of substance use (e.g., McTavish, Chih, Shah, & Gustafson, 2012).

Clinical applications of GPS technology with EMA data at the group level should be considered in future research as well. For instance, if certain locations that individuals occupy in their daily living space are associated with urges to smoke at a group level, future studies could examine how effective public policy interventions (e.g., strategic placement of public health messages) are at deterring smoking or impacting urges to smoke.

Some issues unique to a spatially explicit analysis deserve further consideration including confidentiality, having multiple qualitatively similar locations, participants diverging from “typical” daily patterns, and how GPS can provide an additional level of detail that compliments EMA data.

First, the maintenance of participant confidentiality should be considered with any analysis of high resolution spatial data (Rytkonen, 2004). There are a number of methods that may be applied to reduce such risk (Armstrong, Rushton, & Zimmerman, 1999). In the current study, longitudinal and latitudinal coordinates were standardized to preserve anonymity.

Second, one challenge that emerged in the current data set was defining geographic locations for work. For example, for one participant, physical work location varied daily based on the nature of the job (i.e., distributing advertising materials outside). Additional concerns might emerge for participants who regularly travel for work. Smoking patterns may be more variable than for those who have a fixed work location.

The third consideration involves the utility of spatial data for an individual outside of their typical daily activity space. In the current study, three of 10 participants traveled outside of their typical activity space during a portion of the study. Removal of these types of GPS data points is consistent with past applications of spatial analysis (Zenk et al., 2011); however, it is unclear how such daily activity space divergence is associated with smoking behavior. For instance, does the number or proximity of tobacco retailers influence typical daily smoking behavior when individuals are not in their typical activity space? Further, such questions would require data on tobacco outlet density and proximity for any geographic area a participant visits. Although analysis of such data and determining its utility for constructing predictive models of smoking was outside the scope of the current study, such issues are relevant for future studies.

Finally, the inclusion of GPS data in addition to the EMA data provides a level of detail that should be considered and included in future research. Although physical location can be considered in EMA analysis without GPS data (e.g., having participants indicate where they are when they engage in substance use), certain data can be unique to GPS methods and should be applied to models to address substance use behaviors. For instance, spatially explicit covariates like distance from home or tobacco outlets can only be included when GPS data are used. These covariates can be used to inform models predicting smoking behavior. In addition, the inclusion of GPS allowed us to refine and classify the work locations for individuals with multiple locations. This is important because it allowed us to visualize the relative difference of smoking as a function of these different environments, such as smoking to regulate psychiatric symptoms (Figure 3).

Limitations

Limitations of findings from the current study should be noted. A primary issue that will limit ability to explore the full potential of combined EMA and GPS data is compliance with device use. For the current study, to demonstrate the utility of combined EMA and GPS data, three days of data were considered. Issues involving adherence, however, were common among our sample, including remembering to charge the device and forgetting to keep the device with them. Although these limitations may at least partially be attributable to specific characteristics of the sample from the current study, they should be considered in future studies examining substance use behavior. In particular, providing incentives for compliance may improve such behaviors. Notably, incentives for GPS compliance were not provided for the current study. In addition, we were unable to assess in some cases if participants were not compliant with use of the GPS device (e.g., forgetting to plug it in before going to bed) or if the equipment malfunctioned. Finally, although accuracy of GPS coordinates for the current study was pilot tested and could be compared against qualitative EMA entries about location, future studies should consider the accuracy of these coordinates. For instance, accuracy could depend on signal strength affected by being outside or in a building. Additional indices of accuracy provided by GPS devices would be beneficial in future research. Relatedly, use of Bluetooth technology may be beneficial in fine-grained spatial analysis.

Conclusions

The current study demonstrates that combining EMA and GPS data is both acceptable and feasible to assess typical daily smoking behavior adults with ADHD. To our knowledge, this is the first study to assess such aspects of smoking behavior or involve individuals with clinically significant psychiatric symptoms using GPS technology. Incorporating such spatial data with EMA methods has the potential to improve predictive models and has clear clinical implications. We include a number of recommendations for future studies that incorporate GPS data, which can be applicable to smoking in particular (e.g., examining various stages of smoking behavior) and maladaptive behaviors in general. In summary, careful inclusion of GPS data can enhance our understanding of smoking behavior and potentially contribute to more effective treatment efforts.

Acknowledgments

We thank Amy Brightwood, Joseph English, and Becca Bayham for assistance with data collection.

Findings from this study have been presented at the annual meeting for the Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco, Boston, MA, March 13-16, 2013, the annual meeting for the Society of Behavioral Medicine, San Francisco, CA, March 20-23, 2013, and the inaugural mHealth Conference at Duke University, Durham, NC, April 15, 2013.

Funding: This work was supported by the National Institute of Drug Abuse (NIDA R03 DA029694 to J.T.M., K23 DA032577 to J.T.M., K24 DA02344 to S.H.K., K24 DA016388 to J.C.B. and R21 DA034471 to F.J.M.). R.S.S was supported by a LEADERS award from the Scottish Universities Life Sciences Alliance (SULSA).

Footnotes

A similar visual analysis was conducted for smoking urges and is available upon request from the first author.

Disclosures: Drs. Mitchell, Schick, Beckham, and McClernon, Mr. Hallyburton, and Ms. Dennis report no commercial relationships with financial interests with regard to this paper. Dr. Kollins has received research support and/or consulting fees from the following: Addrenex/Shionogi, Akili Interactive, NIH/NIDA, Otsuka, Pfizer, Purdue Canada, Rhodes, Shire, Sunovion and Supernus.

References

- Armstrong MP, Rushton G, Zimmerman DL. Geographically masking health data to preserve confidentiality. Statistics in Medicine. 1999;18(5):497–525. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(19990315)18:5<497::aid-sim45>3.0.co;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beckham JC, Wiley MT, Miller SC, Dennis MF, Wilson SM, McClernon FJ, Calhoun PS. Ad lib smoking in post-traumatic stress disorder: An electronic diary study. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2008;10(7):1149–1157. doi: 10.1080/14622200802123302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bickel WK, Christensen DR, Marsch LA. A review of computer-based interventions used in the assessment, treatment, and research of drug addiction. Substance Use & Misuse. 2011;46(1):4–9. doi: 10.3109/10826084.2011.521066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control. Annual smoking-attributable mortality, years of potential life lost, and economic costs--United States, 1995-1999. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR) 2002;51(14):300–303. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chuang YC, Cubbin C, Ahn D, Winkleby MA. Effects of neighbourhood socioeconomic status and convenience store concentration on individual level smoking. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 2005;59(7):568–573. doi: 10.1136/jech.2004.029041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conklin CA, Tiffany ST. Applying extinction research and theory to cue-exposure addiction treatments. Addiction. 2002;97(2):155–167. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2002.00014.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conners CK, Erhardt D, Sparrow E. Conners' Adult ADHD Rating Scales (CAARS) technical manual. North Tonawanda, NY: Multi-Health Systems, Inc.; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Cromley EK. GIS and disease. Annual Review of Public Health. 2003;24:7–24. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.24.012902.141019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Csikszentmihalyi M, Larson R. Validity and reliability of the experience-sampling method. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 1987;175(9):526–536. doi: 10.1097/00005053-198709000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- deVries M. The experience of psychopathology: Investigating mental disorders in their natural settings. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Epstein JN, Johnson D, Conners CK. Conners' Adult ADHD Diagnostic Interview for DSM-IV. North Tonawanda, NY: Multi-Health Systems, Inc.; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Ezzati M, Lopez AD. Estimates of global mortality attributable to smoking in 2000. Lancet. 2003;362(9387):847–852. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14338-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng J, Glass TA, Curriero FC, Stewart WF, Schwartz BS. The built environment and obesity: A systematic review of the epidemiologic evidence. Health & Place. 2010;16(2):175–190. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2009.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson SG, Shiffman S. Using the methods of ecological momentary assessment in substance dependence research--smoking cessation as a case study. Substance Use & Misuse. 2011;46(1):87–95. doi: 10.3109/10826084.2011.521399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Gibbon M. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR (SCID-I) - research version. New York, NY: Biometrics Research; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Flamm M, Kaufmann V. The concept of personal network of usual activity places as a tool for analysing human activity spaces: A quantitative exploration; Paper presented at the 6th Swiss Transport Research Conference; Monte Veritá, Switzerland. 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Golledge RG, Stimson RJ. Spatial behavior: A geographic perspective. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Halonen JI, Kivimaki M, Kouvonen A, Pentti J, Kawachi I, Subramanian SV, Vahtera J. Proximity to a tobacco store and smoking cessation: A cohort study. Tobacco Control. 2013 doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2012-050726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heatherton TF, Kozlowski LT, Frecker RC, Fagerström KO. The Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence: A revision of the Fagerström Tolerance Questionnaire. British Journal of Addiction. 1991;86(9):1119–1127. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1991.tb01879.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman A, Kaufman N. Kaufman Brief Intelligence Test. 2nd. Circle Pines, MN: AGP publishing; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Kiluk BD, Nich C, Babuscio T, Carroll KM. Quality versus quantity: Acquisition of coping skills following computerized cognitive-behavioral therapy for substance use disorders. Addiction. 2010;105(12):2120–2127. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03076.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kistemann T, Dangendorf F, Schweikart J. New perspectives on the use of Geographical Information Systems (GIS) in environmental health sciences. International Journal of Hygiene and Environmental Health. 2002;205(3):169–181. doi: 10.1078/1438-4639-00145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lasser K, Boyd JW, Woolhandler S, Himmelstein DU, McCormick D, Bor DH. Smoking and mental illness: A population-based prevalence study. JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association. 2000;284(20):2606–2610. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.20.2606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leal C, Chaix B. The influence of geographic life environments on cardiometabolic risk factors: A systematic review, a methodological assessment and a research agenda. Obesity Reviews. 2011;12(3):217–230. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2010.00726.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsch LA, Dallery J. Advances in the psychosocial treatment of addiction: The role of technology in the delivery of evidence-based psychosocial treatment. The Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 2012;35(2):481–493. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2012.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClernon FJ, Calhoun PS, Hertzberg JS, Dedert EA, Beckham JC. Associations between smoking and psychiatric comorbidity in U.S. Iraq- and Afghanistan-era veterans. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2013 doi: 10.1037/a0032014. Advance online publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClernon FJ, Kollins SH. ADHD and smoking: From genes to brain to behavior. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2008;1141:131–147. doi: 10.1196/annals.1441.016. doi:NYAS1141016.10.1196/annals.1441.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McTavish FM, Chih MY, Shah D, Gustafson DH. How patients recovering from alcoholism use a smartphone intervention. Journal of Dual Diagnosis. 2012;8(4):294–304. doi: 10.1080/15504263.2012.723312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melnick AL, Fleming DW. Modern geographic information systems--promise and pitfalls. Journal of Public Health Management and Practice. 1999;5(2):viii–x. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell JT, Dennis MF, English JS, Dennis PA, Brightwood AG, Beckham JC, Kollins SH. Antecedents and consequences of smoking in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disroder using ecological momentary assessment methodology submitted. [Google Scholar]

- Prociow P, Wac K, Crowe J. Mobile psychiatry: Towards improving the care for bipolar disorder. International Journal of Mental Health Systems. 2012;6(1):5. doi: 10.1186/1752-4458-6-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. 2012 from http://www.R-project.org/

- Reis HT, Gable SL. Event-sampling and other methods for studying everyday experience. In: Reis HT, Judd CM, editors. Handbook of research methods in social and personality psychology. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press; 2000. pp. 190–221. [Google Scholar]

- Reitzel LR, Cromley EK, Li Y, Cao Y, Dela Mater R, Mazas CA, Wetter DW. The effect of tobacco outlet density and proximity on smoking cessation. American Journal of Public Health. 2011;101(2):315–320. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2010.191676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez D, Carlos HA, Adachi-Mejia AM, Berke EM, Sargent JD. Predictors of tobacco outlet density nationwide: A geographic analysis. Tobacco Control. 2012 doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2011-050120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose SW, Myers AE, D'Angelo H, Ribisl KM. Retailer adherence to Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act, North Carolina, 2011. Preventing Chronic Disease. 2013;10:e47. doi: 10.5888/pcd10.120184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rytkonen MJ. Not all maps are equal: GIS and spatial analysis in epidemiology. International Journal of Circumpolar Health. 2004;63(1):9–24. doi: 10.3402/ijch.v63i1.17642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schick RS, Loarie SR, Colchero F, Best BD, Boustany A, Conde DA, Clark JS. Understanding movement data and movement processes: Current and emerging directions. Ecology Letters. 2008;11(12):1338–1350. doi: 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2008.01249.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman S. Ecological momentary assessment (EMA) in studies of substance use. Psychological Assessment. 2009;21(4):486–497. doi: 10.1037/a0017074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman S, Gwaltney CJ, Balabanis MH, Liu KS, Paty JA, Kassel JD, Gnys M. Immediate antecedents of cigarette smoking: An analysis from ecological momentary assessment. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2002;111(4):531–545. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.111.4.531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman S, Stone AA, Hufford MR. Ecological momentary assessment. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2008;4:1–32. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.3.022806.091415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United States Census Bureau. [Accessed November 2, 2013];2010 American community survey. 2010 < http://factfinder2.census.gov/faces/tableservices/jsf/pages/productview.xhtml?pid=ACS_10_1YR_S0801&prodType=table>.

- Zenk SN, Schulz AJ, Matthews SA, Odoms-Young A, Wilbur J, Wegrzyn L, Stokes C. Activity space environment and dietary and physical activity behaviors: A pilot study. Health & Place. 2011;17(5):1150–1161. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2011.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]