Background: Gemcitabine is used to treat solid tumors. Some mycoplasmas preferentially colonize tumors in patients.

Results: Mycoplasma-encoded cytidine deaminase and pyrimidine nucleoside phosphorylase compromise the cytostatic/antitumor activity of gemcitabine in mycoplasma-infected tumor cell cultures and xenografts in mice.

Conclusion: Tumor-associated mycoplasmas may decrease the therapeutic efficiency of gemcitabine.

Significance: Current treatment of mycoplasma-infected tumors with gemcitabine may be suboptimal.

Keywords: Anticancer Drug, Cancer Therapy, Nucleoside Nucleotide Analogs, Nucleoside Nucleotide Metabolism, Phosphorylase, Mycoplasma hyorhinis, Cytidine Deaminase, Gemcitabine, Mycoplasma, Pyrimidine Nucleoside Phosphorylase

Abstract

The intracellular metabolism and cytostatic activity of the anticancer drug gemcitabine (2′,2′-difluoro-2′-deoxycytidine; dFdC) was severely compromised in Mycoplasma hyorhinis-infected tumor cell cultures. Pronounced deamination of dFdC to its less cytostatic metabolite 2′,2′-difluoro-2′-deoxyuridine was observed, both in cell extracts and spent culture medium (i.e. tumor cell-free but mycoplasma-containing) of mycoplasma-infected tumor cells. This indicates that the decreased antiproliferative activity of dFdC in such cells is attributed to a mycoplasma cytidine deaminase causing rapid drug catabolism. Indeed, the cytostatic activity of gemcitabine could be restored by the co-administration of tetrahydrouridine (a potent cytidine deaminase inhibitor). Additionally, mycoplasma-derived pyrimidine nucleoside phosphorylase (PyNP) activity indirectly potentiated deamination of dFdC: the natural pyrimidine nucleosides uridine, 2′-deoxyuridine and thymidine inhibited mycoplasma-associated dFdC deamination but were efficiently catabolized (removed) by mycoplasma PyNP. The markedly lower anabolism and related cytostatic activity of dFdC in mycoplasma-infected tumor cells was therefore also (partially) restored by a specific TP/PyNP inhibitor (TPI), or by exogenous thymidine. Consequently, no effect on the cytostatic activity of dFdC was observed in tumor cell cultures infected with a PyNP-deficient Mycoplasma pneumoniae strain. Because it has been reported that some commensal mycoplasma species (including M. hyorhinis) preferentially colonize tumor tissue in cancer patients, our findings suggest that the presence of mycoplasmas in the tumor microenvironment could be a limiting factor for the anticancer efficiency of dFdC-based chemotherapy. Accordingly, a significantly decreased antitumor effect of dFdC was observed in mice bearing M. hyorhinis-infected murine mammary FM3A tumors compared with uninfected tumors.

Introduction

Chemically modified purine and pyrimidine nucleosides (nucleoside analogs (NAs))5 represent about 20% of all chemotherapeutics currently used in cancer treatment (1). NAs mimic the natural nucleic acid building blocks and act as antimetabolites interfering with tumor cell nucleoside/nucleotide metabolism and/or DNA/RNA synthesis. Many NAs require activation (usually phosphorylation) by cellular enzymes and their anticancer potential is therefore highly dependent on the enzymatic characteristics of the drug-exposed tumor cells (2). Gemcitabine (2′,2′-difluoro-2′-deoxycytidine, dFdC; Fig. 1) is widely used in the treatment of various carcinomas, including pancreas, lung, breast, and bladder cancer (2). Phosphorylated dFdC metabolites act as inhibitors of ribonucleotide reductase and CTP synthetase, resulting in decreased intracellular dNTP (i.e. dCTP) levels, and the drug functions as a DNA chain terminator when incorporated as its 5′-triphosphate metabolite (dFdCTP) into the DNA (3, 4). First dFdC is phosphorylated to its 5′-monophosphate derivative (dFdCMP) by 2′-deoxycytidine kinase. Subsequent phosphorylation to dFdC-5′-diphosphate (dFdCDP) and dFdCTP occurs through nucleoside monophosphate (UMP/CMP) and diphosphate kinase activity, respectively (5). After cellular uptake, dFdC can be deaminated at the nucleoside level by cytidine deaminase (Cyd deaminase) or at the nucleotide level by 2′-deoxycytidine monophosphate deaminase (dCMP deaminase) to produce the markedly less cytostatic metabolites 2′,2′-difluoro-2′-deoxyuridine (dFdU) and 2′,2′-difluoro-2′-deoxyuridine-5′-monophosphate (dFdUMP), respectively (6). As mentioned previously, phosphorylated dFdC metabolites exhibit several self-potentiating effects including inhibition of ribonucleotide reductase and CTP synthetase by dFdCDP and dFdCTP, respectively (7, 8). This results in decreased CTP and dCTP levels creating a competitive advantage for enzymatic drug activation and incorporation of dFdC in nucleic acids (6). In addition, dFdCTP inhibits dCMP deaminase and thereby efficiently reduces deamination (inactivation) of dFdCMP (9).

FIGURE 1.

Schematic representation of the metabolism and antimetabolic effects of dFdC. Dashed lines represent inhibitory activity. RR, ribonucleotide reductase.

Recent studies indicate that an intact intestinal microbiome is essential for optimal anticancer effects of immune therapy or chemotherapy with platinum, doxorubicin, or cyclophosphamide (10, 11). Moreover, the tumor microenvironment itself can be considered an ecosystem of cancer cells and commensal prokaryotes (and resident or infiltrating non-tumor cells). The association of different bacteria (e.g. Helicobacter pylori, Salmonella typhi, Chlamidophyla pneumoniae, Mycoplasma sp., and others) with tumor tissue in cancer patients has been repeatedly reported (12, 13). A variety of studies have shown a higher infection ratio (∼30 to 50%) of human solid tumors by mycoplasmas (mostly by Mycoplasma hyorhinis) compared with healthy or non-malignant diseased tissues (14–23). Such preferential colonization of tumor tissue by prokaryotes may be attributed to: (i) aberrant vascularization, (ii) an increased nutrient availability (due to necrotic tissue) at the tumor site, and/or (iii) tumor-directed bacterial chemotaxis (13). In addition, Huang et al. (24) demonstrated that the tumor suppressor phosphatase and tensin homolog that is frequently mutated or deleted in various human cancers, is also implicated in the cellular defense against mycoplasmas and mycobacteria, which may therefore increase the susceptibility of tumor cells to a mycoplasma infection.

Mycoplasmas are the smallest autonomously replicating organisms, characterized by a small size, strongly reduced genome, and the lack of a cell wall. Some mycoplasmas (e.g. Mycoplasma pneumoniae and Mycoplasma genitalium) are clearly linked with pathogenesis in humans (25), although mycoplasma-associated disease is mostly observed in immunocompromised individuals such as AIDS patients (26). Many mycoplasma species are considered part of the resident flora of the healthy human body, causing asymptomatic infections (27). Due to their reduced set of genes, most mycoplasmas are unable to synthesize pyrimidine and purine nucleotides de novo and rely on the salvage of nucleotide precursors present in the environment (28, 29). Efficient and unique nucleoside/nucleotide uptake mechanisms have been described in mycoplasmas (30) and they express various salvage enzymes to metabolize the available nucleosides/nucleotides according to their own requirements for DNA/RNA synthesis. These include NPs, deaminases, kinases, and other enzymes (28, 31).

We recently demonstrated a significantly decreased cytostatic and antiviral activity of different 5-halogenated thymidine (dThd), 2′-deoxyuridine (dUrd), and uridine (Urd) analogues in M. hyorhinis-infected cells due to phosphorolysis of the drugs (to inactive derivatives) by M. hyorhinis-encoded pyrimidine nucleoside phosphorylase (PyNP) (32, 33). Therefore we hypothesized that mycoplasmas and their metabolic impact on the tumor microenvironment may be of significance when optimizing cancer chemotherapy and that the administration of mycoplasma-directed antibiotics or specific inhibitors of mycoplasma-encoded enzymes may improve therapeutic outcome (34). Here, we report a severely compromised cytostatic activity of dFdC in mycoplasma-infected tumor cell cultures. We investigated the pharmacological basis for these findings and identified a tandem mechanism of drug inactivation in which two catabolic mycoplasma enzymes act in concert to reduce the biological activity of dFdC in vitro and in vivo.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Chemicals

Nucleosides, nucleobases, NAs, and all inorganic compounds were purchased from Sigma, unless stated differently. Radiolabeled 2′-deoxycytidine ([5-3H]dCyd; radiospecificity: 22 Ci/mmol), 2′-deoxyuridine ([5-3H]dUrd; radiospecificity: 15.9 Ci/mmol), and gemcitabine ([5-3H]dFdC; radiospecificity: 24 Ci/mmol) were obtained from Moravek Biochemicals Inc. (Brea, CA). TPI, 5-chloro-6-(1-[2-iminopyrrolidinyl]methyl)uracil hydrochloride, a potent inhibitor of human thymidine phosphorylase (TP) (35) was kindly provided by Prof. V. Schramm (Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Bronx, NY).

Cell Cultures

MCF-7 human breast carcinoma cells were kindly provided by Prof. G. J. Peters (Amsterdam, The Netherlands). FM3A cells (subclone F28-7) were originally established from a spontaneous mammary carcinoma in a C3H/He mouse (36, 37). Murine leukemia L1210, human lymphocytic CEM, and human breast cancer MDA-MB-231 cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) (Manassas, VA). Human osteosarcoma cells deficient in cytosolic thymidine kinase (TK) (designated Ost/TK− cells) were kindly provided by Prof. M. Izquierdo (Universidad Autónoma de Madrid, Madrid, Spain). Tumor cell cultures were infected with M. hyorhinis (ATCC 17981) and after two or more passages (to avoid bias by the initial inoculum) successful infection was confirmed using the MycoAlertTM mycoplasma detection kit (Lonza, Basel, Switzerland). Although this assay is only semi-quantitative, a maximal infection was observed 3 to 4 days after subcultivation of the mycoplasma-exposed cells. Chronically infected tumor cell lines are further referred to as Cell line.Hyor. MCF-7 cells were also infected with wild-type or PyNP-deficient M. pneumoniae M129 (ATCC 29342) (38) (both bacterial strains were kindly provided by Dr. Liya Wang (Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, Uppsala, Sweden)) resulting in chronically infected tumor cell cultures further referred to as MCF-7.Pn and MCF-7.Pn/PyNP−, respectively. All tumor cell cultures were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Biochrom AG, Berlin, Germany), 10 mm HEPES, and 1 mm sodium pyruvate (Invitrogen). MCF-7.Pn/PyNP− cultures were also supplemented with gentamycin (80 μg/ml). Cells were grown at 37 °C in a humidified incubator with a gas phase containing 5% CO2.

Cytostatic Activity Assays

The cytostatic activity of dFdC was examined in mycoplasma-infected and uninfected cancer cell lines. When assaying the effect of M. hyorhinis or M. pneumoniae infections, monolayer cells were seeded in 48-well microtiter plates (NuncTM, Roskilde, Denmark) at 10,000 cells/well or in 6-well microtiter plates (Corning Inc., Corning, NY) at 100,000 cells/well, respectively. After 24 h, the cells were exposed to different concentrations of dFdC (Carbosynth, Compton, UK) and allowed to proliferate for 72 h (to ensure sufficient cell proliferation and mycoplasma growth) after which the cells were trypsinized and counted using a Coulter counter (Analis, Suarlée, Belgium). Suspension cells (L1210, L1210.Hyor, FM3A, and FM3A.Hyor) were seeded in 96-well microtiter plates (Nunc) at 60,000 cells/well in the presence of different concentrations of dFdC. The cells were allowed to proliferate for 48 h and then counted using a Coulter counter. The 50% inhibitory concentration (IC50) was defined as the compound concentration required to reduce cell proliferation by 50%.

Stability of Gemcitabine in Spent Culture Medium and Cell Extracts

The stability of [5-3H]dFdC in spent culture medium (mycoplasma-containing but cell-free) or cell extracts of confluent MCF-7 and MCF-7.Hyor tumor cells was evaluated. Tumor cells were seeded in 75-cm2 culture flasks (TTP, Trasadingen, Switzerland). After 5 days, 1 ml of supernatant was withdrawn and cleared by centrifugation at 300 × g for 6 min to remove (debris of) mammalian cells. Subsequently, 20 μl of PBS containing 2 μCi of [5-3H]dFdC was added to 300 μl of the supernatants in the presence or absence of TPI (10 μm) or the Cyd deaminase inhibitor tetrahydrouridine (THU; 1 mm (Calbiochem, Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) and samples were incubated at 37 °C. At different time points (t = 0, 30, and 120 min), 100-μl fractions were withdrawn, and ice-cold MeOH was added to a final concentration of 66% MeOH to terminate the enzymatic reactions. Samples were kept on ice for 10 min and cleared by centrifugation at 16,000 × g for 15 min. The supernatants were withdrawn, evaporated, and the resulting precipitate was resuspended in 65 μl of PBS. Subsequently 50 μl was analyzed on a reverse phase RP-8 column (Merck) using HPLC (Alliance 2690, Waters, Milford, MA). The following gradient was used: from 98% solution A (50 mm NaH2PO4 (Acros Organics, Geel, Belgium); 5 mm heptane sulfonic acid, pH 3.2) and 2% solution B (acetonitrile (BioSolve BV, Valkenswaard, the Netherlands)) to 75% solution A and 25% solution B as follows: 10 min at 98% solution A + 2% solution B; 10-min linear gradient to 90% solution A + 10% solution B; 10-min linear gradient to 80% solution A + 20% solution B; 5-min linear gradient to 75% solution A + 25% solution B; 5-min linear gradient to 98% solution A + 2% solution B followed by a 10-min equilibration at 98% solution A and 2% solution B. Fractions of 1 ml were collected, transferred to 9 ml of OptiPhase HiSafe 3, and radioactivity was counted in a liquid scintillation analyzer. In addition, inhibition of dFdC deamination in the spent culture medium of MCF-7.Hyor cells by natural pyrimidine nucleosides dThd, dUrd, and Urd was studied. Reactions were performed in a final volume of 300 μl containing dFdC (5 μm), [5-3H]dFdC (1μCi), different concentrations of dThd, dUrd, or Urd (100, 20, 4, and 0.8 μm), and 240 μl of tumor cell-free (mycoplasma-containing) spent culture medium. Uracil (100 μm) was included as a negative control. After 60-min incubation 100 μl were withdrawn and dFdC deamination (dFdU formation) was analyzed as described above.

To study the stability of [5-3H]dFdC in cell extracts, MCF-7 and MCF-7.Hyor cells were washed with ice-cold PBS and removed from the culture flask using a cell scraper. Cells were centrifuged at 300 × g for 6 min, resuspended in 250 μl of ice-cold PBS, and proteins were released by sonication. All procedures were performed at 4 °C. Cellular debris was removed by centrifugation (10 min at 16,000 × g) and [5-3H]dFdC (2 μCi in 20 μl) was exposed to 115 μl of supernatant in the presence or absence of THU (1 mm). Samples were incubated at 37 °C and 30-μl fractions were withdrawn at different time points (t = 0, 30, and 120 min). Samples were processed and analyzed by HPLC analysis as described above.

Metabolism Assays

The metabolism of dFdC was compared in mycoplasma-infected and uninfected human breast carcinoma MCF-7 and murine breast carcinoma FM3A cell cultures. MCF-7 cells were seeded at 32,000 cells/cm2 and after 24 h exposed to 0.1 μm dFdC (containing 2 μCi of [5-3H]dFdC) in the presence or absence of THU (1 mm), TPI (10 μm), or dThd (100 or 500 μm). After 24 (THU) or 48 h (TPI and dThd) incubation in the presence of the compounds, cells were harvested, washed twice with serum-free DMEM, and exposed to 66% cold methanol. The precipitated cell mixture was then kept on ice for 10 min and subsequently cleared by centrifugation (15 min; 16,000 × g). The supernatant containing intracellular dFdC and its phosphorylated metabolites was analyzed by HPLC using a Partisphere-SAX anion exchange column (5.6 × 125 mm, Whatman International Ltd., Maidstone, UK). The following gradient was used: 5 min at 100% buffer B (5 mm NH4H2PO4, pH 5); a 15-min linear gradient of 100% buffer B to 100% buffer C (300 mm NH4H2PO4, pH 5); 20 min at 100% buffer C; a 5-min linear gradient to 100% buffer B; equilibration at 100% buffer B for 5 min. Fractions of 2 ml were collected, transferred into 9 ml of OptiPhase HiSafe 3 (PerkinElmer Life Sciences), and radioactivity was counted in a liquid scintillation analyzer (PerkinElmer Life Sciences). To quantify the amount of dFdC-derived radiolabel into nucleic acids, the pellet obtained after MeOH extraction was washed twice with MeOH 66%, resuspended in MeOH 66%, and transferred into 9 ml of OptiPhase HiSafe 3. Radioactivity was measured using a liquid scintillation analyzer. Similarly, the metabolism of dFdC was studied in FM3A cells (seeded at 400,000 cells/ml) after 24 h exposure to 0.1 μm dFdC (containing 2 μCi [5-3H]dFdC) in the presence or absence of TPI (10 μm) or dThd (100 or 500 μm).

Thymidylate Synthase-catalyzed Tritium Release from [5-3H]dUrd and [5-3H]dCyd-exposed Tumor Cells

The de novo synthesis of thymidine 5′-monophosphate (dTMP) was evaluated in intact CEM, CEM.Hyor, L1210, and L1210.Hyor cells by measuring the release of tritium from [5-3H]dUMP (formed in the cells from [5-3H]dUrd or [5-3H]dCyd) in the reaction catalyzed by thymidylate synthase. This method has been described in detail by Balzarini and De Clercq (39). Briefly, 500-μl cell cultures were prepared in DMEM containing ∼3 × 106 cells. After 20, 40, and 60 min incubation of the cells in the presence of 1 μCi of [5-3H]dUrd or [5-3H]dCyd, 100 μl of the cell suspensions were withdrawn and added to a cold suspension of 500 μl of activated charcoal (VWR, Haasrode, Belgium) (100 mg/ml in 5% TCA (Merck Chemicals Ltd.)). After 10 min, the tumor cell suspension was centrifuged at 16,000 × g for 10 min and 400 μl of supernatant was added to 9 ml of OptiPhase Hisafe 3. Radioactivity was counted in a liquid scintillation analyzer.

Tumor Growth Assays in Mice

Female SCID mice (∼8 weeks old; weighing ∼20 g) were inoculated (day 0) in the mammary fat pad with 2 × 106 FM3A cells (in 100 μl of DMEM). Exponentially growing M. hyorhinis (cultured in liquid mycoplasma medium (Mycoplasma Experience Ltd., Reigate, UK)) were pelleted (400 μl of culture; 25 min; 16,000 × g), resuspended in 50 μl of PBS, and injected intratumorally. For the control groups, similarly treated but sterile mycoplasma medium was injected. Successful mycoplasma infection of tumors was confirmed 24 h post-inoculation (experiment carried out in 3 mice). Mycoplasma DNA was detected using PCR as previously described (32). Additionally, to investigate the presence of viable mycoplasmas, resected tumor tissues were cultured in vitro, and mycoplasma infection in the derived tumor cell cultures was confirmed using the MycoAlertTM Mycoplasma Detection Kit.

For both dFdC (Gemzar (Lilly, Brussels, Belgium)) and 5-fluoro-2′-deoxyuridine (5-FdUrd; floxuridine), two separate experiments (n = 20 mice per experiment) were performed with slightly different treatment and mycoplasma infection regimens. To compare the antitumor activities of the compounds against M. hyorhinis-infected and uninfected murine mammary tumors, mice were divided in 4 groups: drug-treated and control mice, inoculated or not with M. hyorhinis. dFdC (50 mg/kg) and 5-FdUrd (50 mg/kg) were administered intraperitoneally in 200 μl of PBS; equal amounts of PBS were injected in the control group. dFdC was administered on days 4, 7, and 10 and M. hyorhinis on days 1, 3, 6, 9, and 11 (experiment 1) after tumor cell injection. Mice were sacrificed and dissected on day 12. Alternatively (experiment 2), one additional dFdC administration was included on day 12, and mice were euthanized and dissected on day 14. For 5-FdUrd (administered on days 4, 6, 8, 10, and 12), M. hyorhinis was administered on days 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, and 12 (experiment 1) or on days 1, 3, 5, 7, 9, and 11 (experiment 2) after tumor cell injection. Mice were sacrificed and dissected on day 14. A two-way linear model was used to compare the tumor weight at the end of the experiment as a function of M. hyorhinis infection and chemotherapeutic efficiency. Because our data originated from two separate experiments, “experiment” was added as a factor in the model. For both dFdC and 5-FdUrd, there was no statistical evidence that the effects of infection and chemotherapy depended on the experiment. Therefore, no interactions with the factor experiment were included in the final model. Tukey adjustments were used for pairwise comparisons. Analyses were performed using the SAS System software version 9.2 for Windows (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

Statistical Analyses

Unless stated differently, statistical analyses were performed using Microsoft Excel 2007 (Microsoft, Redmond, WA). A p value was considered significant if smaller than 0.05. Spearman rank-order correlations were determined using GraphPad Prism 5 (GraphPad Software Inc., La Jolla, CA).

RESULTS

Compromised Cytostatic Activity of Gemcitabine in Mycoplasma-infected Tumor Cell Cultures

A variety of human and murine cancer cell lines were infected with M. hyorhinis (Cell line.Hyor). The cytostatic activity of dFdC was evaluated in both the uninfected and mycoplasma-infected tumor cell cultures. Depending on the nature of the cell line, a M. hyorhinis infection resulted in a ∼10- to ∼60-fold decreased activity of dFdC (Table 1). Pre-treatment of MCF-7.Hyor cell cultures with tetracycline (1 μg/ml, 6 days) efficiently eliminated the mycoplasma infection (undetectable by the MycoAlertTM mycoplasma detection kit (Lonza)) and restored the cytostatic potential of dFdC (IC50 = 0.0060 ± 0.003 μm) to the level observed in uninfected control cells (IC50 = 0.0058 ± 0.0019) (Table 1). This indicated that the mycoplasma infection was responsible for the altered cytostatic activity of dFdC.

TABLE 1.

Cytostatic activity of dFdC as such and in the presence of THU (250 μm) as represented by the IC50 value in different cell lines

Data represent the mean (± S.D.) of at least two independent experiments.

| Cell line | IC50a |

|

|---|---|---|

| dFdC | dFdC + THU (250 μm) | |

| μm | ||

| MCF-7 | 0.0058 ± 0.0019 | 0.0054 ± 0.0015 |

| MCF-7.Hyor | 0.16 ± 0.11 | 0.0080 ± 0.0070 |

| MDA-MB-231 | 0.0046 ± 0.0005 | 0.0043 ± 0.0003 |

| MDA-MB-231.Hyor | 0.28 ± 0.15 | 0.0036 ± 0.0001 |

| FM3A | 0.038 ± 0.006 | 0.024 ± 0.001 |

| FM3A.Hyor | 0.63 ± 0.16 | 0.013 ± 0.002 |

| L1210 | 0.014 ± 0.002 | 0.0077 ± 0.003 |

| L1210.Hyor | 0.32 ± 0.23 | 0.0094 ± 0.001 |

a 50% inhibitory concentration or compound concentration required to inhibit tumor cell proliferation by 50%.

Co-administration of THU (a potent Cyd deaminase inhibitor) also efficiently rescued the antiproliferative effect of dFdC in mycoplasma-infected tumor cell cultures (Table 1) suggesting conversion of the drug by Cyd deaminase to its markedly less cytostatic derivative dFdU. Poor activation of dFdU by human cytosolic and mitochondrial TK compared with natural dThd (data not shown) may, at least partially, explain its low biological, i.e. cytostatic, activity compared with dFdC.

Pronounced Deamination of Gemcitabine in Mycoplasma-infected Tumor Cell Cultures

Because THU was able to restore the decreased cytostatic activity of dFdC in the presence of mycoplasmas, direct drug deamination was investigated by exposing [5-3H]dFdC to the spent culture medium (tumor cell-free supernatant) and tumor cell extracts of confluent MCF-7 and MCF-7.Hyor cell cultures (Fig. 2). No measurable deamination of dFdC could be observed in the supernatant (Fig. 2A) or cell extract (Fig. 2B) of uninfected MCF-7 cells. In contrast, ∼90% [5-3H]dFdC was converted to [5-3H]dFdU when incubated for 2 h in the spent culture medium of MCF-7.Hyor cells (Fig. 2A). It should be noted that tumor cells but not mycoplasmas were removed when preparing the spent culture medium. Deamination of [5-3H]dFdC was successfully inhibited by THU (1 mm) (<10% [5-3H]dFdU formation after 2 h). Surprisingly, [5-3H]dFdC deamination was also (partially) inhibited by the powerful TP/PyNP inhibitor TPI (10 μm) (∼60% [5-3H]dFdU compared with ∼90% [5-3H]dFdU after 2 h in the absence of TPI) (Fig. 2A).

FIGURE 2.

Deamination of dFdC by mycoplasma enzymes. Deamination of dFdC in the spent culture medium (A) or cell extracts (B) of confluent MCF-7 and MCF-7.Hyor cell cultures, in the presence or absence of THU (1 mm) or TPI (10 μm). The data are the mean of two independent experiments (± S.E.) and were analyzed using a t test.

Pronounced drug deamination was also observed when exposing [5-3H]dFdC to the cell extracts of MCF-7.Hyor cells (∼50% [5-3H]dFdU formation after 2 h) and could be efficiently prevented by THU (1 mm) (<1% [5-3H]dFdU formation after 2 h) (Fig. 2B). These findings strongly indicate a rapid deamination of dFdC in mycoplasma-infected tumor cell cultures.

Stimulation of Gemcitabine Deamination by Mycoplasma PyNP

The surprising inhibitory effect of the TP/PyNP inhibitor TPI on dFdC deamination in mycoplasma-infected tumor cell cultures (Fig. 2A) was further investigated. PyNP does not accept dFdC as a substrate but efficiently catabolizes the natural products of Cyd deaminase-catalyzed reactions, dUrd and Urd (33). Therefore dFdC (5 μm) deamination in the spent culture medium of MCF-7.Hyor cells was studied in the presence of different concentrations of all natural substrates of mycoplasma PyNP (i.e. dThd, dUrd, and Urd). Uracil was included as a negative control (Fig. 3). dFdC deamination was efficiently inhibited by the natural pyrimidine nucleosides (at IC50 ≈ 3 μm) but not by uracil. These findings suggest that mycoplasma PyNP removes the natural end products of mycoplasma Cyd deaminase-catalyzed reactions thereby preventing (feedback) inhibition of the enzyme and thus stimulation of dFdC deamination.

FIGURE 3.

Inhibition of mycoplasma-associated dFdC deamination by natural pyrimidine nucleosides. Percentage inhibition of dFdC deamination (5 μm) by different concentrations of dThd, dUrd, or Urd. Uracil (100 μm) is used as a negative control. The data are the mean of at least two independent experiments (± S.E.). A significant correlation was found between dFdC deamination and concentration of exogenous dThd, dUrd, and Urd. (Spearman correlations for: dThd (r = 0.94; p < 0.001), dUrd (r = 0.92; p < 0.001), and Urd (r = 0.96; p < 0.001).).

To confirm such a potentiating role of dFdC breakdown by mycoplasma PyNP, the effect of PyNP inhibition on the cytostatic activity of dFdC was studied in several mycoplasma-infected (and uninfected) tumor cell cultures. Co-administration of TPI (10 μm) and dFdC indeed rescued the antiproliferative effect of the drug in the mycoplasma-infected tumor cell cultures (partially or completely, depending on the nature of the tumor cell line) (Table 2). This effect was also observed in tumor cell cultures that are known to lack cellular TP (i.e. L1210 and MCF-7) confirming a prominent role for mycoplasma PyNP in the decreased activity of dFdC. In agreement with inhibition of mycoplasma Cyd deaminase by dThd, the cytostatic activity of dFdC could be (partially) restored by addition of dThd to the mycoplasma-infected cell cultures (Table 2). TPI or dThd (administered at concentrations up to 250 μm) did not affect the proliferation capacity of both uninfected and M. hyorhinis-infected FM3A cells. Similarly, TPI (250 μm) did not affect the growth of uninfected and M. hyorhinis-infected MCF-7 cells. The 50% inhibitory concentration of dThd in MCF-7 and MCF-7.Hyor cells was 40 ± 3 and 32 ± 8 μm, respectively. The 50% cytotoxic concentration (CC50) for TPI and dThd was >250 μm in MCF-7 and MCF-7.Hyor cell cultures as determined by a 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-5-(3-carboxymethoxyphenyl)-2-(4-sulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium colorimetric assay.

TABLE 2.

Cytostatic activity of dFdC as such and in the presence of TPI (10 μm) or dThd (20 or 100 μm) as represented by the IC50 value in different cell lines

Data represent the mean (± S.D.) of at least two independent experiments.

| Cell line | IC50a |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| dFdC | dFdC + TPI (10 μm) | dFdC + dThd (20 μm) | dFdC + dThd (100 μm) | |

| μm | ||||

| MCF-7 | 0.0058 ± 0.0019 | 0.0053 ± 0.0015 | 0.0053 ± 0.0015 | NDb |

| MCF-7.Hyor | 0.16 ± 0.11 | 0.0091 ± 0.0058 | 0.0045 ± 0.0007 | ND |

| MDA-MB-231 | 0.0046 ± 0.0005 | 0.0039 ± 0.0018 | 0.0044 ± 0.0004 | 0.0049 ± 0.0008 |

| MDA-MB-231.Hyor | 0.28 ± 0.15 | 0.072 ± 0.085 | 0.14 ± 0.07 | 0.045 ± 0.026 |

| Ost/TK− | 0.0035 ± 0.0017 | 0.0044 ± 0.0003 | 0.0029 ± 0.0018 | 0.0030 ± 0.0017 |

| Ost/TK−.Hyor | 0.049 ± 0.018 | 0.0041 ± 0.0006 | 0.022 ± 0.001 | 0.0043 ± 0.00001 |

| FM3A | 0.038 ± 0.006 | 0.026 ± 0.001 | 0.045 ± 0.005 | 0.038 ± 0.005 |

| FM3A.Hyor | 0.63 ± 0.16 | 0.036 ± 0.001 | 0.18 ± 0.001 | 0.057 ± 0.006 |

| L1210 | 0.014 ± 0.002 | 0.012 ± 0.001 | ND | ND |

| L1210.Hyor | 0.32 ± 0.23 | 0.042 ± 0.001 | ND | ND |

a 50% inhibitory concentration or compound concentration required to inhibit tumor cell proliferation by 50%.

b ND, not determined.

The cytostatic activity of dFdC was also evaluated in human MCF-7 breast carcinoma cells infected with M. pneumoniae (designated MCF-7.Pn cells) and the corresponding PyNP-deficient M. pneumoniae strain (designated MCF-7.Pn/PyNP− cells). A 4.5-fold decreased cytostatic activity of dFdC in MCF-7.Pn cell cultures (IC50 = 0.036 ± 0.019 μm) was observed compared with uninfected MCF-7 cells (IC50 = 0.008 ± 0.002 μm). In contrast, the cytostatic activity of dFdC was fully preserved in MCF-7.Pn/PyNP− cell cultures that lack PyNP activity (IC50 = 0.009 ± 0.001 μm).

Decreased Concentrations of Intracellular Phosphorylated Gemcitabine Metabolites in Mycoplasma-infected Tumor Cell Cultures

Next, we studied the metabolism of radiolabeled [5-3H]dFdC in uninfected and M. hyorhinis-infected breast carcinoma MCF-7 cells (Fig. 4). It should be noted that dFdC and its deaminated counterpart dFdU could not be separated at the nucleoside level by the anion exchange HPLC system used for these experiments. As shown in Fig. 4A, comparable concentrations of intracellular radiolabeled nucleosides (dFdC/(dFdU)) were observed in MCF-7 and MCF-7.Hyor cells. However, the intracellular concentrations of dFdCMP, dFdCDP, and dFdCTP were up to 1,000-fold lower in MCF-7.Hyor compared with MCF-7 cells (Fig. 4A). Ultimately, this resulted in a ∼145-fold reduction of the dFdC-derived radiolabel in the DNA/RNA of MCF-7.Hyor cells (0.064 pmol/106 cells) (white bars) compared with MCF-7 cells (9.3 pmol/106 cells) (black bars). Concomitant administration of THU (1 mm) and dFdC to MCF-7.Hyor cells did not affect the intracellular nucleoside concentrations (dFdC/dFdU) but restored the formation of phosphorylated dFdC metabolites and DNA/RNA drug incorporation to the levels observed in uninfected cells (Fig. 4B, white bars).

FIGURE 4.

Metabolic activation of dFdC in MCF-7 and MCF-7.Hyor cells in the presence/absence of THU. Concentrations of intracellular dFdC metabolites after 24 h incubation of MCF-7 and MCF-7.Hyor cells in the presence of 0.1 μm dFdC. Panel A, dFdC. Panel B, dFdC + 1 mm THU. The data are the mean of at least two independent experiments (± S.E.). A t test was performed on the log-transformed data (*, p < 0.01).

Restoration of Intracellular Gemcitabine Anabolism in Mycoplasma-infected Tumor Cell Cultures by TPI or dThd

Because, besides THU, TPI and exogenously added dThd also partially restored the cytostatic activity of dFdC, the formation of phosphorylated dFdC metabolites was studied in mycoplasma-infected and control tumor cells in the presence of TPI or a high dose of dThd (Fig. 5). As shown in Fig. 5A, after 48 h, phosphorylated dFdC metabolite levels and incorporated radiolabel were significantly lower (∼100- to 1,000-fold) in MCF-7.Hyor cells (white bars) compared with uninfected MCF-7 cells (black bars). In this experimental set-up the deaminated metabolite dFdUMP could be detected (48 h instead of 24 h incubation) and its concentration was found to be >100-fold lower in MCF-7.Hyor cells compared with MCF-7 cells. Concomitant administration of dFdC and TPI (10 μm) partially restored the phosphorylation of dFdC in mycoplasma-infected cells but did not affect its metabolism in control MCF-7 cells (Fig. 5B). Although the total concentration of phosphorylated dFdC metabolites was still ∼10-fold lower in MCF-7.Hyor cells compared with MCF-7 cells in the presence of TPI, the amount of DNA/RNA-incorporated radiolabel was comparable in both tumor cell cultures (both incorporated ∼3.4 pmol/106 cells) (Fig. 5B). Thymidine partially (100 μm dThd; Fig. 5C) or fully (500 μm dThd; Fig. 5D) restored the phosphorylation of dFdC to its mono-, di-, and triphosphate derivatives in MCF-7.Hyor cells. Drug incorporation into DNA/RNA of MCF-7.Hyor cells was already completely restored by 100 μm dThd (Fig. 5, A and C). A much more modest effect of dThd was observed in uninfected MCF-7 cells, where the accumulation of phosphorylated dFdC derivatives did not change and the incorporation of the radiolabel in methanol-insoluble material was only increased by ∼3- or ∼5-fold (for 100 and 500 μm dThd, respectively). Comparable results were obtained in mycoplasma-infected and uninfected murine FM3A breast carcinoma cells in the presence or absence of TPI and dThd (data not shown).

FIGURE 5.

Metabolic activation of dFdC in MCF-7 and MCF-7.Hyor cells in the presence/absence of TPI or dThd. Concentrations of intracellular dFdC metabolites after 48 h incubation of MCF-7 and MCF-7.Hyor cells in the presence of 0.1 μm dFdC. Panel A, dFdC. Panel B, dFdC + 10 μm TPI. Panel C, dFdC + 100 μm dThd; Panel D, dFdC + 500 μm dThd. The data are the mean of at least two independent experiments (± S.E.). A t test was performed on the log-transformed data (*, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.001).

Natural Pyrimidine Nucleosides Are Catabolized in Mycoplasma-infected Tumor Cells

Our observations indicated that mycoplasma PyNP causes pronounced alterations of host cell pyrimidine nucleoside metabolism/availability and thereby prevents inhibition of mycoplasma Cyd deaminase by natural endogenous dThd, dUrd, and Urd. Earlier we reported efficient PyNP-catalyzed phosphorolysis of dThd in the tumor cell-free supernatant of mycoplasma-infected cell cultures (32). We now studied in detail how PyNP activity affects pyrimidine nucleoside metabolism/availability in mycoplasma-infected tumor cells.

First, the de novo synthesis of dTMP from the exogenously supplied precursors [5-3H]dUrd and [5-3H]dCyd was studied in mycoplasma-infected and uninfected CEM and L1210 cell cultures. As visualized in Fig. 6, intracellular dTMP is formed from dUMP in a reaction catalyzed by thymidylate synthase. In mammalian cells, dUMP can be produced from: (i) dUTP by dUTP diphosphatase activity, (ii) dUDP by the reversible thymidylate kinase-catalyzed reaction or nonspecific phosphatase activity, (iii) dUrd by TK activity, or (iv) dCMP by dCMP deaminase activity. When supplying [5-3H]dUrd or [5-3H]dCyd to tumor cells as thymidylate precursors, intracellular dTMP formation can be monitored by measuring the amount of tritium released upon methylation of [5-3H]dUMP in a reaction catalyzed by thymidylate synthase (Fig. 6) (39). Pronounced time-dependent dTMP formation from exogenously administered [5-3H]dUrd was observed in CEM and L1210 cell cultures, whereas this activity was severely compromised in mycoplasma-infected tumor cell cultures (Fig. 7, A and B). A short preincubation (5 min) of the mycoplasma-infected tumor cells with TPI before administration of [5-3H]dUrd fully restored dTMP formation but did not affect its formation in uninfected cells (Fig. 7, A and B). These findings indicate that dUrd, being an excellent substrate for PyNP-catalyzed phosphorolysis (33), is indeed rapidly catabolized in M. hyorhinis-infected tumor cell cultures resulting in decreased concentrations of [5-3H]dUrd-derived dUMP required for de novo dTMP synthesis. Also, dTMP formation from [5-3H]dCyd was dramatically decreased in CEM.Hyor and L1210.Hyor cells compared with uninfected cell cultures and could be rescued by preincubation of the cells with TPI (Fig. 7, C and D). However, dCyd is not a substrate for PyNP but may be rapidly deaminated to dUrd in mycoplasma-infected tumor cell cultures after which it is catabolized (phosphorolysed) by PyNP. These results confirm pronounced pyrimidine nucleoside phosphorolysis and 2′-deoxycytidine deamination in mycoplasma-infected tumor cell cultures altering the availability of natural nucleosides in the host cells. Our findings also suggest that transport of dFdC is not compromised in mycoplasma-infected tumor cells because dUrd and dCyd uptake by mycoplasma-infected tumor cells per se (in the presence of TPI to block PyNP activity) is not substantially different from uninfected tumor cells.

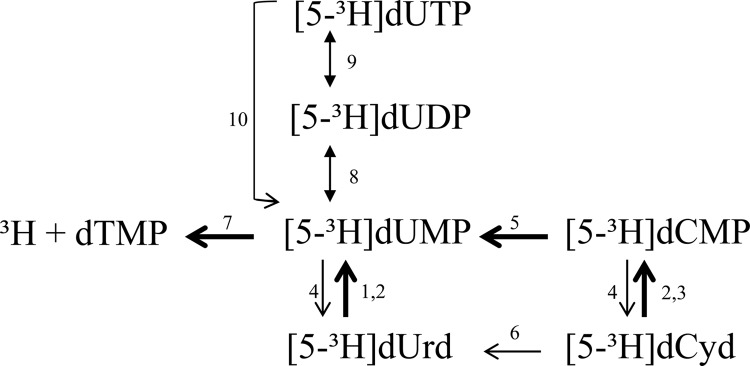

FIGURE 6.

Schematic representation of dTMP biosynthesis from [5-3H]dUrd and [5-3H]dCyd. 1, dThd kinase (cytosolic TK-1); 2, dThd kinase (mitochondrial TK-2); 3, dCyd kinase; 4, 5′-nucleotidase; 5, CMP/dCMP deaminase; 6, Cyd deaminase; 7, thymidylate synthase; 8, dTMP kinase; 9, nucleoside diphosphate kinase; 10, dUTP diphosphatase.

FIGURE 7.

De novo synthesis of dTMP in mycoplasma-infected and uninfected tumor cell cultures. Time-dependent synthesis of dTMP was measured as tritium release from [5-3H]dUrd (A and B) or [5-3H]dCyd (C and D) in the absence or presence of 10 μm TPI in CEM and CEM.Hyor cells (A and C), and L1210 and L1210.Hyor cells (B and D). The data are the mean of two independent experiments (± S.E.). A t test was performed on the log-transformed data.

Mycoplasma Infection Reduces the Antitumor Activity of Gemcitabine in SCID Mice

Next, we evaluated the effect of dFdC (50 mg/kg) on M. hyorhinis-infected and uninfected murine mammary tumors in SCID mice. Floxuridine (50 mg/kg) is rapidly catabolized (inactivated) by the mycoplasma PyNP and was used as a control drug. Murine FM3A carcinoma cells were inoculated in the mammary fat pad of SCID mice, and exponentially growing M. hyorhinis cells were injected intratumorally before intraperitoneal drug administration. Because tumors grew internally than externally, tumor growth could not be monitored accurately over time and therefore chemotherapeutic treatment efficiency was evaluated by measuring the tumor weight at the end of the experiment. Administration of dFdC and 5-FdUrd significantly inhibited the growth of uninfected tumors by ∼65% (Fig. 8, A and B). In contrast, treatment of M. hyorhinis-infected tumors only resulted in a non-significant 27 (for dFdC) and 10% (for 5-FdUrd) inhibition of tumor growth. Statistical analysis showed a significant difference between the antitumor effects of both anticancer drugs in uninfected versus mycoplasma-infected tumors. Thus, the observed compromised cytostatic activity of dFdC (and 5-FdUrd) in mycoplasma-infected tumor cell cultures may indeed be relevant for the clinical treatment of tumors if infected by mycoplasmas.

FIGURE 8.

Effect of mycoplasma infection on the antitumor activity of dFdC and 5-FdUrd. In vivo antitumor activity of dFdC (panel A) and 5-FdUrd (panel B) against uninfected and M. hyorhinis-infected mammary FM3A tumors in SCID mice as represented by the tumor weight at the end of the experiment. The data represent the mean ± S.E. The interaction between infection and chemotherapy is significant for dFdC (p = 0.025) and 5-FdUrd (p = 0.0004).

DISCUSSION

The cytostatic activity of the anticancer drug gemcitabine was consistently decreased in various human and murine tumor cell cultures after infection with M. hyorhinis but could be restored by elimination of the mycoplasmas with tetracycline or specific suppression of mycoplasma-encoded catabolic enzymes. Metabolism studies revealed markedly decreased intracellular concentrations of 5′-phosphorylated [5-3H]dFdC metabolites and incorporated [5-3H]dFdC-derived radiolabel in the DNA/RNA of mycoplasma-infected human MCF-7 and murine FM3A breast carcinoma cells compared with uninfected cells. Because the antitumor effect of dFdC is mainly due to: (i) ribonucleotide reductase inhibition by its diphosphorylated metabolite and (ii) DNA incorporation (1), these findings explain the observed decreased cytostatic activity of the drug in the presence of mycoplasmas.

The anabolism and subsequent cytostatic activity of dFdC in mycoplasma-infected cell cultures could be restored by THU (a Cyd deaminase inhibitor), indicating direct drug inactivation by mycoplasma Cyd deaminase producing dFdU, a metabolite that is poorly cytostatic in mammalian cells (6). Previous research also demonstrated a decreased activity of dCyd analogues such as gemcitabine and cytarabine (araC; an antitumor drug that is also subject to deamination) in Cyd deaminase-overexpressing human tumor cells (40, 41) and progenitor cells (42). The activity of such antitumor molecules could be counteracted by co-administration of THU (40). More recently, decreased chemosensitivity of pancreatic adenocarcinoma to gemcitabine was attributed to macrophage-induced up-regulation of Cyd deaminase (43, 44) indicating the high relevance of Cyd deaminase expression in the tumor microenvironment. We confirmed pronounced mycoplasma-associated conversion of dFdC to dFdU when exposing the radiolabeled drug to the spent culture medium (containing free-living mycoplasmas) or tumor cell extracts (containing enzymes of adherent/intracellular mycoplasmas) of mycoplasma-infected but not uninfected MCF-7 cells. Cyd deaminase activity has been described before in mycoplasma extracts (45) and a cytidine deaminase gene was annotated in the genome of several mycoplasmas, including M. hyorhinis (46).

Previous research from our laboratory revealed a severely decreased cytostatic/antiviral activity of different therapeutic pyrimidine nucleoside analogues (including floxuridine and 5-trifluorothymidine) in M. hyorhinis-infected tumor cell cultures due to the expression of a highly active mycoplasma-encoded PyNP (32, 33). This enzyme catalyzes the phosphorolysis of the natural nucleosides dThd, dUrd, and Urd, and several of their therapeutic derivatives. The cytostatic activity of such drugs could be rescued by addition of the potent PyNP inhibitor TPI or high dose dThd (a competitive substrate for mycoplasma PyNP) (33). Surprisingly, the metabolism and subsequent cytostatic activity of dFdC in mycoplasma-infected tumor cells could now also be (partially) restored by TPI or exogenous dThd, even in tumor cell lines that lack measurable endogenous TP expression (i.e. L1210 and MCF-7 (our observations and Ref. 47). In line with these findings, the antiproliferative activity of dFdC was compromised in tumor cell cultures when infection was established with wild-type M. pneumoniae but not with a PyNP-deficient M. pneumoniae strain. Because cytosine-based nucleosides, including dFdC, are not susceptible to direct NP-catalyzed phosphorolysis (48), we wanted to study the biochemical basis of these results. Mycoplasma-associated dFdC deamination was markedly inhibited by Urd, dUrd, or dThd, indicating that PyNP activity prevents feedback inhibition of mycoplasma Cyd deaminase by removal of its natural inhibitors. Previously, mycoplasma infection was shown to decrease [3H]dThd incorporation in the nucleic acids of cultured cells (49–51), and pronounced dThd phosphorolysis was observed in the spent culture medium of M. hyorhinis-infected cells (32). Also the synthesis of dTMP from dUMP using both dUrd and dCyd as a dUMP source was severely compromised in M. hyorhinis-infected cells but could be normalized by the addition of TPI. Direct phosphorolysis of dUrd, an excellent substrate for PyNP (33), producing uracil and 2-deoxyribose-1-phosphate, is most likely responsible for the observed decreased dUMP and subsequent dTMP formation from exogenously added dUrd. dCyd is not a substrate for PyNP-catalyzed phosphorolysis (33) but was rapidly converted to dUrd by Cyd deaminase (as observed for dFdC), which may then be further degraded by mycoplasma PyNP to uracil. Thus, two catabolic mycoplasma-encoded enzymes (i.e. Cyd deaminase and PyNP) seem to act in concert to suppress dFdC anabolism (phosphorylation). In fact, dFdC is efficiently deaminated by mycoplasma-encoded Cyd deaminase in a reaction that is further potentiated by PyNP-catalyzed removal of the naturally inhibiting nucleosides (i.e. dThd, dUrd, and Urd). Such concerted action of two mycoplasma enzymes may cause the dramatic suppression of dFdC anabolism and related cytostatic potential.

In an attempt to evaluate the clinical relevance of our in vitro results, we implemented a mouse model to compare the antitumor activity of dFdC against mycoplasma-infected and uninfected murine mammary FM3A tumors in SCID mice. It proved to be particularly challenging to obtain persistent mycoplasma infection in mice at the tumor site. Previous research showed that intraperitoneal passage in mice eliminates different mycoplasmas from contaminated tumor cell cultures (52) and more recently, passage in SCID mice was suggested as a method to remove mycoplasmas from infected Chlamydia cultures (53). It is unclear why many mycoplasmas do not persist in SCID mice. Residual antibacterial protection by macrophages, natural killer cells, or polymorphonuclear granulocytes, as well as the typical narrow host spectrum of mycoplasmas have been put forward as possible explanations (53). In our in vivo model, M. hyorhinis was administered intratumorally before each drug administration. Both dFdC and 5-FdUrd efficiently inhibited the growth of uninfected tumors, whereas the treatment of mycoplasma-exposed tumors was significantly compromised. Although still preliminary, these results convincingly indicate a decreased sensitivity of M. hyorhinis-exposed tumors to a dFdC- (or 5-FdUrd-) based treatment. A retrospective analysis on the correlation between mycoplasmas and the therapeutic outcome of dFdC treatment would be of interest. However, to the best of our knowledge no such data are currently available. Recent studies reported that antibiotic administration prior to, or during, immune therapy and platinum- or doxorubicin-based chemotherapy of cancer may negatively affect therapeutic outcome (10, 11). In contrast, our results indicate that co-administration of antibiotics (targeting mycoplasmas) with certain NAs (both pyrimidine- and purine-based (54)) may in fact improve therapeutic efficacy. These findings argue for a better understanding and careful consideration of the commensal microbiota when optimizing cancer therapy.

In conclusion, we showed that a mycoplasma infection severely compromises the cytostatic activity of dFdC by direct mycoplasma-related deamination of the drug at the nucleoside level. Furthermore, dFdC deamination is stimulated by selective PyNP-catalyzed removal (phosphorolysis) of natural pyrimidine nucleosides that act as Cyd deaminase inhibitors (Fig. 1). In vivo experiments confirmed that mycoplasma infection reduced the antitumor activity of dFdC. Therefore, combination therapy of dFdC with mycoplasma-targeting antibiotics or with targeted inhibitors of mycoplasma-encoded (catabolic) enzymes (e.g. the PyNP-inhibitor TPI and/or the cytidine deaminase inhibitor THU) may optimize cancer treatment efficacy. Both inhibitors have already been used in clinical studies: co-administration of 350 mg/m2 of THU and 200 mg/m2 of araC to leukemia patients resulted in serum araC levels and antitumor response rates comparable with those achieved with a high dose (≥1 g/m2) of araC (55), and TPI is an active ingredient of TAS-102 (a co-formulation with 5-trifluorothymidine) for treatment of metastatic colorectal tumors (56). It would therefore be feasible to study the potential of such molecules to improve dFdC-based treatment efficiency in clinical trials.

Acknowledgments

We thank Eef Meyen, Kristien Minner, Lizette van Berckelaer, and Ria Van Berwaer for excellent technical assistance. We are grateful to Dr. Vern Schramm for kindly providing TPI and Dr. Liya Wang for providing M. pneumoniae and M. pneumoniae.PyNP−.

This work was supported in part by “Fonds voor Wetenschappelijk Onderzoek (FWO) Vlaanderen” Krediet number G.0486.08 and KU Leuven Grant GOA 10/014.

- NA

- nucleoside analog

- 5-FdUrd

- floxuridine

- Cyd

- cytidine

- dCyd

- 2′-deoxycytidine

- dFdC

- gemcitabine

- dFdCDP

- gemcitabine-5′-diphosphate

- dFdCMP

- gemcitabine-5′-monophosphate

- dFdCTP

- gemcitabine-5′-triphosphate

- dFdU

- 2′,2′-difluoro-2′-deoxyuridine

- dFdUMP

- 2′,2′-difluoro-2′-deoxyuridine-5′-monophosphate

- dThd

- thymidine

- dUrd

- 2′-deoxyuridine

- NP

- nucleoside phosphorylase

- PyNP

- pyrimidine nucleoside phosphorylase

- THU

- tetrahydrouridine

- TK

- thymidine kinase

- TP

- thymidine phosphorylase

- TPI

- thymidine phosphorylase inhibitor

- SCID

- severe combined immunodeficiency

- araC

- cytarabine.

REFERENCES

- 1. Parker W. B. (2009) Enzymology of purine and pyrimidine antimetabolites used in the treatment of cancer. Chem. Rev. 109, 2880–2893 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Galmarini C. M., Mackey J. R., Dumontet C. (2002) Nucleoside analogues and nucleobases in cancer treatment. Lancet. Oncol. 3, 415–424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Huang P., Chubb S., Hertel L. W., Grindey G. B., Plunkett W. (1991) Action of 2′,2′-difluorodeoxycytidine on DNA synthesis. Cancer Res. 51, 6110–6117 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ross D. D., Cuddy D. P. (1994) Molecular effects of 2′,2′-difluorodeoxycytidine (Gemcitabine) on DNA replication in intact HL-60 cells. Biochem. Pharmacol. 48, 1619–1630 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Heinemann V., Hertel L. W., Grindey G. B., Plunkett W. (1988) Comparison of the cellular pharmacokinetics and toxicity of 2′,2′-difluorodeoxycytidine and 1-β-d-arabinofuranosylcytosine. Cancer Res. 48, 4024–4031 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bergman A. M., Peters G. J. (2006) Gemcitabine, mechanism of action and resistance. In Deoxynucleoside analogues in cancer therapy (Peters G. J., ed) pp. 225–251, Humana Press Inc., Totowa, NJ [Google Scholar]

- 7. Heinemann V., Xu Y. Z., Chubb S., Sen A., Hertel L. W., Grindey G. B., Plunkett W. (1990) Inhibition of ribonucleotide reduction in CCRF-CEM cells by 2′,2′-difluorodeoxycytidine. Mol. Pharmacol. 38, 567–572 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Heinemann V., Schulz L., Issels R. D., Plunkett W. (1995) Gemcitabine: a modulator of intracellular nucleotide and deoxynucleotide metabolism. Semin. Oncol. 22, 11–18 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Xu Y. Z., Plunkett W. (1992) Modulation of deoxycytidylate deaminase in intact human leukemia cells: action of 2′,2′-difluorodeoxycytidine. Biochem. Pharmacol. 44, 1819–1827 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Iida N., Dzutsev A., Stewart C. A., Smith L., Bouladoux N., Weingarten R. A., Molina D. A., Salcedo R., Back T., Cramer S., Dai R. M., Kiu H., Cardone M., Naik S., Patri A. K., Wang E., Marincola F. M., Frank K. M., Belkaid Y., Trinchieri G., Goldszmid R. S. (2013) Commensal bacteria control cancer response to therapy by modulating the tumor microenvironment. Science 342, 967–970 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Viaud S., Saccheri F., Mignot G., Yamazaki T., Daillère R., Hannani D., Enot D. P., Pfirschke C., Engblom C., Pittet M. J., Schlitzer A., Ginhoux F., Apetoh L., Chachaty E., Woerther P. L., Eberl G., Bérard M., Ecobichon C., Clermont D., Bizet C., Gaboriau-Routhiau V., Cerf-Bensussan N., Opolon P., Yessaad N., Vivier E., Ryffel B., Elson C. O., Doré J., Kroemer G., Lepage P., Boneca I. G., Ghiringhelli F., Zitvogel L. (2013) The intestinal microbiota modulates the anticancer immune effects of cyclophosphamide. Science 342, 971–976 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Mager D. L. (2006) Bacteria and cancer: cause, coincidence or cure? A review. J. Transl. Med. 4, 14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Cummins J., Tangney M. (2013) Bacteria and tumours: causative agents or opportunistic inhabitants? Infect. Agent. Cancer 8, 11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Chan P. J., Seraj I. M., Kalugdan T. H., King A. (1996) Prevalence of mycoplasma conserved DNA in malignant ovarian cancer detected using sensitive PCR-ELISA. Gynecol. Oncol. 63, 258–260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kidder M., Chan P. J., Seraj I. M., Patton W. C., King A. (1998) Assessment of archived paraffin-embedded cervical condyloma tissues for mycoplasma-conserved DNA using sensitive PCR-ELISA. Gynecol. Oncol. 71, 254–257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Huang S., Li J. Y., Wu J., Meng L., Shou C. C. (2001) Mycoplasma infections and different human carcinomas. World J. Gastroenterol. 7, 266–269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Pehlivan M., Itirli G., Onay H., Bulut H., Koyuncuoglu M., Pehlivan S. (2004) Does Mycoplasma sp. play role in small cell lung cancer? Lung Cancer 45, 129–130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Pehlivan M., Pehlivan S., Onay H., Koyuncuoglu M., Kirkali Z. (2005) Can mycoplasma-mediated oncogenesis be responsible for formation of conventional renal cell carcinoma? Urology 65, 411–414 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Yang H., Qu L., Ma H., Chen L., Liu W., Liu C., Meng L., Wu J., Shou C. (2010) Mycoplasma hyorhinis infection in gastric carcinoma and its effects on the malignant phenotypes of gastric cancer cells. BMC Gastroenterol. 10, 132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Apostolou P., Tsantsaridou A., Papasotiriou I., Toloudi M., Chatziioannou M., Giamouzis G. (2011) Bacterial and fungal microflora in surgically removed lung cancer samples. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 6, 137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Urbanek C., Goodison S., Chang M., Porvasnik S., Sakamoto N., Li C. Z., Boehlein S. K., Rosser C. J. (2011) Detection of antibodies directed at M. hyorhinis p37 in the serum of men with newly diagnosed prostate cancer. BMC Cancer 11, 233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Barykova Y. A., Logunov D. Y., Shmarov M. M., Vinarov A. Z., Fiev D. N., Vinarova N. A., Rakovskaya I. V., Baker P. S., Shyshynova I., Stephenson A. J., Klein E. A., Naroditsky B. S., Gintsburg A. L., Gudkov A. V. (2011) Association of Mycoplasma hominis infection with prostate cancer. Oncotarget 2, 289–297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Erturhan S. M., Bayrak O., Pehlivan S., Ozgul H., Seckiner I., Sever T., Karakök M. (2013) Can mycoplasma contribute to formation of prostate cancer? Int. Urol. Nephrol. 45, 33–38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Huang G., Redelman-Sidi G., Rosen N., Glickman M. S., Jiang X. (2012) Inhibition of mycobacterial infection by the tumor suppressor PTEN. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 23196–23202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Waites K. B., Talkington D. F. (2004) Mycoplasma pneumoniae and its role as a human pathogen. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 17, 697–728, table of contents [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Razin S., Yogev D., Naot Y. (1998) Molecular biology and pathogenicity of mycoplasmas. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 62, 1094–1156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Krause D. C., Taylor-Robinson D. (1992) Mycoplasmas which infect humans. In: Mycoplasmas, molecular biology and pathogenesis (Maniloff J., McElhaney R. N., Finch L. R., Baseman J. B., eds) pp. 417–744, American Society for Microbiology, Washington, D.C [Google Scholar]

- 28. Finch L. R., Mitchell A. (1992) Sources of nucleotides. In: Mycoplasmas, molecular biology and pathogenesis (Maniloff J., McElhaney R. N., Finch L. R., Baseman J. B., eds) pp. 211–230, American Society for Microbiology, Washington, D.C [Google Scholar]

- 29. Pollack J. D., Williams M. V., McElhaney R. N. (1997) The comparative metabolism of the mollicutes (mycoplasmas): the utility for taxonomic classification and the relationship of putative gene annotation and phylogeny to enzymatic function in the smallest free-living cells. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 23, 269–354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Neale G. A., Mitchell A., Finch L. R. (1984) Uptake and utilization of deoxynucleoside 5′-monophosphates by Mycoplasma mycoides subsp. mycoides. J. Bacteriol. 158, 943–947 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Tham T. N., Ferris S., Kovacic R., Montagnier L., Blanchard A. (1993) Identification of Mycoplasma pirum genes involved in the salvage pathways for nucleosides. J. Bacteriol. 175, 5281–5285 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Bronckaers A., Balzarini J., Liekens S. (2008) The cytostatic activity of pyrimidine nucleosides is strongly modulated by Mycoplasma hyorhinis infection: implications for cancer therapy. Biochem. Pharmacol. 76, 188–197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Vande Voorde J., Gago F., Vrancken K., Liekens S., Balzarini J. (2012) Characterization of pyrimidine nucleoside phosphorylase of Mycoplasma hyorhinis: implications for the clinical efficacy of nucleoside analogues. Biochem. J. 445, 113–123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Liekens S., Bronckaers A., Balzarini J. (2009) Improvement of purine and pyrimidine antimetabolite-based anticancer treatment by selective suppression of mycoplasma-encoded catabolic enzymes. Lancet Oncol. 10, 628–635 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Fukushima M., Suzuki N., Emura T., Yano S., Kazuno H., Tada Y., Yamada Y., Asao T. (2000) Structure and activity of specific inhibitors of thymidine phosphorylase to potentiate the function of antitumor 2′-deoxyribonucleosides. Biochem. Pharmacol. 59, 1227–1236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Nakano N. (1966) Establishment of cell lines in vitro from a mammary ascites tumor of mouse and biological properties of the established lines in a serum containing medium. Tohoku J. Exp. Med. 88, 69–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Ayusawa D., Koyama H., Iwata K., Seno T. (1980) Single-step selection of mouse FM3A cell mutants defective in thymidylate synthetase. Somatic Cell Genet. 6, 261–270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Wang L., Schmidl S., Stülke J. (2014) Mycoplasma pneumoniae thymidine phosphorylase. Nucleosides Nucleotides Nucleic Acids, in press [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Balzarini J., De Clercq E. (1984) Strategies for the measurement of the inhibitory effects of thymidine analogs on the activity of thymidylate synthase in intact murine leukemia L1210 cells. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 785, 36–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Neff T., Blau C. A. (1996) Forced expression of cytidine deaminase confers resistance to cytosine arabinoside and gemcitabine. Exp. Hematol. 24, 1340–1346 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Yoshida T., Endo Y., Obata T., Kosugi Y., Sakamoto K., Sasaki T. (2010) Influence of cytidine deaminase on antitumor activity of 2′-deoxycytidine analogs in vitro and in vivo. Drug Metab. Dispos. 38, 1814–1819 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Bardenheuer W., Lehmberg K., Rattmann I., Brueckner A., Schneider A., Sorg U. R., Seeber S., Moritz T., Flasshove M. (2005) Resistance to cytarabine and gemcitabine and in vitro selection of transduced cells after retroviral expression of cytidine deaminase in human hematopoietic progenitor cells. Leukemia 19, 2281–2288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Amit M., Gil Z. (2013) Macrophages increase the resistance of pancreatic adenocarcinoma cells to gemcitabine by up-regulating cytidine deaminase. Oncoimmunology 2, e27231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Weizman N., Krelin Y., Shabtay-Orbach A., Amit M., Binenbaum Y., Wong R. J., Gil Z. (2013) Macrophages mediate gemcitabine resistance of pancreatic adenocarcinoma by up-regulating cytidine deaminase. Oncogene 10.1038/onc.2013.357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. McElwain M. C., Chandler D. K. F., Barile M. F., Young T. F., Tryon V. V., Davis J. W., Jr., Petzel J. P., Chang C. J., Williams M. V., Pollack J. D. (1988) Purine and pyrimidine metabolism in Mollicutes species. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 38, 417–423 [Google Scholar]

- 46. Goodison S., Urquidi V., Kumar D., Reyes L., Rosser C. J. (2013) Complete genome sequence of Mycoplasma hyorhinis strain SK76. Genome Announc. 1, 1–2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Patterson A. V., Zhang H., Moghaddam A., Bicknell R., Talbot D. C., Stratford I. J., Harris A. L. (1995) Increased sensitivity to the prodrug 5′-deoxy-5-fluorouridine and modulation of 5-fluoro-2′-deoxyuridine sensitivity in MCF-7 cells transfected with thymidine phosphorylase. Br. J. Cancer 72, 669–675 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Mini E., Nobili S., Caciagli B., Landini I., Mazzei T. (2006) Cellular pharmacology of gemcitabine. Ann. Oncol. 17, v7-v12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Jakway J. P., Shevach E. M. (1984) Mycoplasma contamination: a hazard of screening hybridoma supernatants for inhibition of [3H]thymidine incorporation. J. Immunol. Methods 67, 337–345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Sinigaglia F., Talmadge K. W. (1985) Inhibition of [3H]thymidine incorporation by Mycoplasma arginini-infected cells due to enzymatic cleavage of the nucleoside. Eur. J. Immunol. 15, 692–696 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Merkenschlager M., Kardamakis D., Rawle F. C., Spurr N., Beverley P. C. (1988) Rate of incorporation of radiolabelled nucleosides does not necessarily reflect the metabolic state of cells in culture: effects of latent mycoplasma contamination. Immunology 63, 125–131 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Hirschberg L., Bölske G., Holme T. (1989) Elimination of mycoplasmas from mouse myeloma cells by intraperitoneal passage in mice and by antibiotic treatment. Hybridoma 8, 249–257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Essig A., Heinemann M., Schweitzer R., Simnacher U., Marre R. (2000) Decontamination of a mycoplasma-infected Chlamydia pneumoniae strain by pulmonary passage in SCID mice. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 290, 289–292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Vande Voorde J., Liekens S., Balzarini J. (2013) Mycoplasma hyorhinis-encoded purine nucleoside phosphorylase: kinetic properties and its effect on the cytostatic potential of purine-based anticancer drugs. Mol. Pharmacol. 84, 865–875 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Kreis W., Budman D. R., Chan K., Allen S. L., Schulman P., Lichtman S., Weiselberg L., Schuster M., Freeman J., Akerman S. (1991) Therapy of refractory/relapsed acute leukemia with cytosine arabinoside plus tetrahydrouridine (an inhibitor of cytidine deaminase): a pilot study. Leukemia 5, 991–998 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Yoshino T., Mizunuma N., Yamazaki K., Nishina T., Komatsu Y., Baba H., Tsuji A., Yamaguchi K., Muro K., Sugimoto N., Tsuji Y., Moriwaki T., Esaki T., Hamada C., Tanase T., Ohtsu A. (2012) TAS-102 monotherapy for pretreated metastatic colorectal cancer: a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 13, 993–1001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]