Background: Meprin A is a membrane-associated metalloproteinase in proximal tubules that plays an important role in acute kidney injury (AKI).

Results: In ischemia-reperfusion injury, meprin A is shed from the membranes, and ADAM10 was identified as the major sheddase.

Conclusion: ADAM10 is the major sheddase involved in the release of meprin A.

Significance: These studies identify ADAM10 as a potential therapeutic target for AKI.

Keywords: ADAM ADAMTS, Kidney, Metalloprotease, Mouse, Shedding, siRNA, ADAM10, ADAM17, Meprin

Abstract

Meprin A, composed of α and β subunits, is a membrane-bound metalloproteinase in renal proximal tubules. Meprin A plays an important role in tubular epithelial cell injury during acute kidney injury (AKI). The present study demonstrated that during ischemia-reperfusion-induced AKI, meprin A was shed from proximal tubule membranes, as evident from its redistribution toward the basolateral side, proteolytic processing in the membranes, and excretion in the urine. To identify the proteolytic enzyme responsible for shedding of meprin A, we generated stable HEK cell lines expressing meprin β alone and both meprin α and meprin β for the expression of meprin A. Phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate and ionomycin stimulated ectodomain shedding of meprin β and meprin A. Among the inhibitors of various proteases, the broad spectrum inhibitor of the ADAM family of proteases, tumor necrosis factor-α protease inhibitor (TAPI-1), was most effective in preventing constitutive, phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate-, and ionomycin-stimulated shedding of meprin β and meprin A in the medium of both transfectants. The use of differential inhibitors for ADAM10 and ADAM17 indicated that ADAM10 inhibition is sufficient to block shedding. In agreement with these results, small interfering RNA to ADAM10 but not to ADAM9 or ADAM17 inhibited meprin β and meprin A shedding. Furthermore, overexpression of ADAM10 resulted in enhanced shedding of meprin β from both transfectants. Our studies demonstrate that ADAM10 is the major ADAM metalloproteinase responsible for the constitutive and stimulated shedding of meprin β and meprin A. These studies further suggest that inhibiting ADAM 10 activity could be of therapeutic benefit in AKI.

Introduction

Meprins are zinc-dependent metalloproteinases of the “astacin” family that are highly expressed at the brush-border membranes of the kidney and intestines (1). Expression of meprins has also been identified in human skin epithelia (2), leukocytes in the lamina propria of the human inflamed bowel (3, 4), mesenteric lymph nodes (5), colorectal (3, 4) and breast cancer cells (6), and recently in glomeruli of some strains of rat (7). Meprins are oligomeric neutral metalloproteinases composed of two evolutionarily related subunits, α and β, that form homo- or hetero-oligomeric structures (1, 8, 9). Meprin A, composed of α and β, is the major form present in the apical membranes (brush-border) of renal proximal tubules (10–12). In the apical membranes, meprin A is anchored to the membranes through the membrane-spanning domain of the β subunit (1). Both meprin α and β subunits are initially synthesized as membrane-spanning proteins but, during biosynthesis, the additional inserted domain (I-domain) containing the transmembrane domain of an α subunit is proteolytically cleaved in the endoplasmic reticulum. The β subunit with its intact transmembrane domain is anchored to the brush-border membranes as a type 1 integral plasma membrane protein. The mature form of meprin α is retained by the β subunit by disulfide linkages or is released into the extracellular space (1). Meprin β is predicted to have a large extracellular domain with a short cytoplasmic tail (26 amino acids).

The role of meprin A has been studied in experimental models of acute kidney injury (AKI)2 including ischemia-reperfusion (IR) and cisplatin nephrotoxicity. Meprin A-deficient mice were markedly resistant to IR injury, and a selective meprin A inhibitor provided protection from AKI induced by IR injury (13), cisplatin nephrotoxicity (14), and sepsis (15). The normal distribution of meprin A in the proximal tubules is altered in experimental models of cisplatin nephrotoxicity (14) and ischemia-reperfusion (13, 16). A soluble form of meprin A was detected in the urine in an experimental model of cisplatin nephrotoxicity (14). The evidence that meprin A is redistributed and a cleaved form of meprin A is excreted in the urine during cisplatin nephrotoxicity suggests ectodomain shedding of meprin A from the brush-border membranes of proximal tubules. Meprins are able to degrade numerous substrates ranging from basement membrane proteins, such as collagen, laminin, fibronectin, and nidogen (1, 16–19) to pro-cytokines, growth factors, protein kinases, and other bioactive peptides (11, 20–23). Thus, meprin A that is normally restricted to the brush-border membranes of proximal tubules may become detrimental on its release during renal injury due to its enormous ability for protein and peptide degradation. Although altered distribution of meprin A from the apical membranes toward the basolateral side has been described in renal IR injury (13, 16), the shedding of meprin A has not been previously examined in response to IR injury.

In the present study, we have examined whether membrane-associated meprin A is shed during IR-induced AKI. We have also determined that a soluble form of meprin A is produced and released in urine of mice subjected to IR injury. Most importantly, using pharmacological and genetic approaches, we have identified the major protease involved in the shedding of meprin A as well as meprin β.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Reagents

The protease inhibitors aprotinin, DAPT, d-VFK-CMK, MMP-2/MMP-9 inhibitor-I, and tumor necrosis factor-α protease inhibitor (TAPI-1) as well as ionomycin (IM) were purchased from Calbiochem. GM6001 was purchased from Millipore (Billerica, MA). GI254023X and GW280264X were synthesized by GlaxoSmithKline (Stevenage, UK) and characterized for inhibition of recombinant and cell-expressed ADAM10 and ADAM17 as described (24). Cisplatin was purchased from Novaplus (Bedford, OH). Phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA), actinonin, leupeptin, pepstatin A, PMSF, and all other chemicals were from Sigma-Aldrich unless specified otherwise.

Cell Culture

HEK293 cells obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) (Manassas, VA) were grown in DMEM/F12 medium supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum, 100 units/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin (all from Invitrogen) at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2.

Preparation of Murine Primary Renal Tubular Epithelial Cells

Primary cells were prepared from kidneys of 10-week-old male C57BL/6N mice as described previously (25, 26) in the presence of protease inhibitors PMSF (1 mm), leupeptin, and pepstatin A (1 μg/ml each). Cells were suspended in growth medium containing serum-free DMEM/F12 supplemented with transferrin and insulin (both at 5 μg/ml), hydrocortisone (50 nm), penicillin (100 units/ml), and streptomycin (100 μg/ml). The cell suspension derived from both kidneys of each mouse was plated in equal aliquots on 6-cm cell culture dishes followed by treatment with 50 nm PMA, 2.5 μm ionomycin, or vehicle (DMSO) for 30 min prior to the addition of 25 μm TAPI-1, 2 μm GI254023X, or vehicle (DMSO). After 2 h in medium, supernatants were collected and centrifuged at 500 × g for 5 min to remove cells, and the supernatants were centrifuged at 100,000 × g for 30 min to remove cellular debris. Aliquots of equal protein content were analyzed by Western blots for the presence of meprin β.

Animals

Animal protocol for these studies was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and Institutional Safety Committee of Central Arkansas Veterans Healthcare System. C57BL/6N male mice (8–10 weeks old) were purchased from Charles Rivers Laboratories (Wilmington, MA) and housed with free access to water and standard diet according to the standards of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Cisplatin Model for Acute Kidney Injury

Male mice (n = 6) were administered a single dose of cisplatin (20 mg/kg of body weight) intraperitoneally. Control animals were administered saline. Animals were anesthetized, and kidneys were harvested 1, 2, and 3 days after cisplatin administration. Kidneys were fixed in formalin for immunohistochemistry or snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C until used. Blood was collected by retro-orbital bleeding to determine blood urea nitrogen (BUN) and creatinine levels using diagnostic kits from International Bio-Analytical Industries Inc. (Boca Raton, FL).

IR Model for Acute Kidney Injury

Male mice (22–25 g; n = 6) were subjected to 40 min of ischemia by occluding renal pedicles with smooth vascular clamps as described previously (16). Following the ischemic period, clamps were removed, and animals were allowed to recover for 24 h. The control animals underwent surgery without clamping of renal arteries. Kidney tissues were fixed in formalin for immunohistochemistry or stored frozen for later use. BUN and creatinine were determined as mentioned above.

Immunohistochemistry

Deparaffinized kidney sections (8 μm) were immunostained with polyclonal goat anti-meprin β antibody (R&D Systems: AF3300, Minneapolis, MN) and polyclonal rabbit antibody against Na+/K+-ATPase (Santa Cruz Biotechnology: sc-28800, Santa Cruz, CA) at 4 °C overnight. After washing with PBS, sections were incubated with secondary antibodies donkey anti-goat Alexa Fluor 594 or donkey anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 488 (Molecular Probes/Invitrogen), and nuclei were counterstained with VECTASHIELD mounting medium containing DAPI (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). Epi-immunofluorescence was recorded on Olympus microscopes (BX51, IX51, or IX71).

Preparation of Whole Cell Lysate, Cytosolic, and Membrane Fractions from Mouse Kidney

Kidneys from mice that underwent IR injury were homogenized in 20 mm HEPES, pH 7.2, in the presence of protease inhibitors leupeptin, pepstatin A, and PMSF using a Dounce homogenizer. Crude homogenates were centrifuged at 9000 × g at 4 °C for 20 min to remove cellular debris, and the supernatant was used as total homogenate. This homogenate was centrifuged at 100,000 × g at 4 °C for 1 h. The supernatant representing the cytosolic extract was removed, and the pellet resuspended in HEPES buffer with brief sonication was used as a membrane fraction. Protein concentration was determined by Bradford assay (Bio-Rad), and aliquots were separated on 4–12% NuPAGE gels (Invitrogen) or on 7.5% SDS-PAGE gels. Western blots on PVDF were developed with a polyclonal antibody against meprin β (AF3300: R&D Systems) followed by donkey anti-goat HRP-conjugated antibody (sc-2020: Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Signals were detected using SuperSignal West Pico (Pierce).

Construction of Meprin β Expression Vector

Briefly, prepromeprin β cDNA from the plasmid pKAIA3940 (GenBankTM accession number AY695931) was subcloned into the pENTR/SD/D-TOPO entry vector (Invitrogen). The meprin β expression vector was then prepared by in vitro recombination of the meprin β containing entry vector with a modified destination vector pIRESpuro3GW (21) using LR Clonase (Invitrogen), and the sequence of the final construct pBeta3940-IRESpuro3 clone 4 was verified by DNA sequencing.

Construction of Meprin α Expression Vector

An expression vector containing the full-length human meprin α coding region with an HA epitope inserted in the C-terminal region of the I-domain was used. Briefly the meprin α cDNA present in the plasmid KAIA0754 (GenBank accession number AF478685) was modified by a PCR procedure to insert an HA epitope (YPYDVPDYA) within the I-domain of the meprin α coding region and subcloned into the entry vector pENTR/SD/D-TOPO, which was recombined with destination vector pIREShyg3GW. The fidelity of clone 6, pIREShyg3GM6-meprinα-HA, was verified by DNA sequencing.

Preparation of Stable Transfectants of HEK293 Cells with Human Meprin α, β, and αβ

HEK293 cells were grown in 12-well plates in minimum Eagle's medium plus 10% horse serum supplemented with l-glutamine (Invitrogen) and transfected with 1 μg of plasmid DNA (of above mentioned expression vectors) containing meprin α or β alone or co-transfected with both meprin α and β using 2 μl of Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). Clones expressing meprin α were selected using 150 μg/ml hygromycin B (Calbiochem) and clones expressing meprin β were selected with 2 μg/ml puromycin (Calbiochem), whereas clones of co-transfectants were selected with 50 μg/ml hygromycin B and 1 μg/ml puromycin.

Characterization of Stable Meprin α, β, and αβ Transfectants by RT-PCR

RNA was isolated from several clones of stable meprin α, β, and αβ transfectants with RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). cDNA was prepared with Superscript II RT (Invitrogen), and transcripts were assayed by PCR for the presence of meprin α, β, or both αβ with the following primers (from Integrated DNA Technologies, Coralville, IA): mep1α-s, 5′-GATGATGACCACAATTGGAAAATTG-3′; mep1α-as, 5′-ACCTGTCTGTTTTCTACCGGCCACTC-3′; mep1β-s, 5′-AGAGAGCACAATTTTAACACCTATAGT-3′; mep1β-as, 5′-CTATCGAAATGCATGAAGAAACCAGA-3′; actin-β-s, 5′-GACATCCGCAAAGACCTGTACG-3′; and actin-β-as, 5′-ACTGGGCCATTCTCCTTAGAG-3′. β-Actin was used as a housekeeping gene. PCR products of individual clones were analyzed on 1% agarose gels, and clones testing positive were chosen for further characterization.

Characterization of Stable Meprin α, β, and αβ Transfectants by Western Blot

Cell lysates of stably transfected meprin clones were prepared in 1× cell lysis buffer (Cell Signaling, Beverly, MA) supplemented with leupeptin and pepstatin A (1 μg/ml) and PMSF (1 mm). Lysates were sonicated briefly and spun at 1000 × g for 5 min. Protein concentrations of the supernatants were determined using a BCA protein assay (Pierce), and aliquots were stored frozen until used for Western blot.

To check for meprins released into the medium, cell culture supernatant was collected after transfectants had been grown in serum-free medium for 4 h. Aliquots of the media were concentrated in Amicon Ultra-4 centrifugal filter units (Millipore), protein concentration was determined using a BCA protein assay, and samples containing equal protein amounts were lyophilized. Aliquots were separated on 4–12% NuPAGE gels (Invitrogen) or on 7.5% SDS-PAGE gels. Western blots on PVDF were developed with polyclonal antibodies against the ectodomains of meprin α and meprin β (AF3220 and AF3300: R&D Systems) followed by donkey anti-goat HRP-conjugated antibody (SC-2020: Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Signals were detected using SuperSignal West Pico (Pierce). Densitometry of the Western blots was performed on a ChemiDoc gel imaging system using Quantity One software (Bio-Rad).

Meprin Shedding in the Presence of Pharmacological Inhibitors

Stable transfectants, as well as untransfected HEK293 cells, were seeded at 1 × 105 cells/ml in 6-cm dishes in DMEM/F12 medium supplemented with 10% FBS, grown to 70% confluency, and then shifted to serum-free medium. Cells were pretreated with 30 ng/ml PMA or vehicle for 30 min before adding the individual inhibitors or vehicle and grown for 4 more hours. Medium supernatants (equal volumes) were transferred into fresh tubes and spun at 500 × g at 4 °C for 5 min, the resulting supernatant was spun at 100,000 × g for 30 min, and samples of equal volume were concentrated in Amicon Ultra-4 centrifugal filter units. Protein concentration was determined, and aliquots were lyophilized for Western blot. Whole cell lysates were prepared for Western blot as described above. Analogous experiments were carried out in the presence of IM at a final concentration of 2.5 μm. Western blots were stripped and stained with Ponceau S to visualize residual albumin serving as loading control.

Overexpression of ADAM10 and Meprin A and Meprin β Shedding

Bovine ADAM10-HA in vector pcDNA3 (plasmid construct kindly provided by Dr. Rolf Postina, University of Mainz, Germany) was expressed in NEB5αF′Iq-competent cells (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA). Plasmid DNA (1 μg) of bovine ADAM10-HA/pcDNA3 or empty vector was used to transiently transfect control HEK cells or HEK cells stably transfected with meprin β or both meprin α and β using Lipofectamine 2000 according to the manufacturer's instructions (Invitrogen). Cell medium was exchanged to serum-containing medium the following day. After 48 h of transfection, cells were shifted to serum-free medium for 4 h before harvesting. Medium supernatant and cells were processed as described above to assess shedding of meprin β.

Meprin Shedding in the Presence of siRNA to ADAM9, ADAM10, or ADAM17

The expression of ADAM9, ADAM10, or ADAM17 in meprin-expressing HEK cells, as well as control HEK cells, grown to 40% confluency was knocked down with 20 nm siRNA pools targeting human ADAM9, ADAM10, or ADAM17 (Dharmacon, Lafayette, CO) according to the manufacturer's instructions, whereas 20 nm scrambled siRNA (Invitrogen) served as negative control. Medium was exchanged to serum-containing medium the day after transfection. Forty-eight hours after transfection, cells were shifted to serum-free medium and treated with 30 ng/ml PMA or vehicle for 4 h before harvesting. Medium supernatant and cells were processed as described above to assess shedding of meprin β. In addition, the expression levels of ADAM10 were monitored by Western blot with polyclonal rabbit antibodies to ADAM10 (Millipore: AB19026, Temecula, CA).

RESULTS

Meprin A Is Redistributed and Shed Following Acute Kidney Injury

Meprin A, composed of α and β subunits, is anchored to the apical membranes of proximal tubules via the β subunit. Both α and β meprin subunits are co-localized in the brush-border membranes (27). Double-immunofluorescence staining of control kidney sections with meprin β (red) and Na/K-ATPase (green) antibodies demonstrated that meprin A, which is exclusively localized to brush-border membranes of the proximal tubules in normal kidneys (Fig. 1A), is redistributed in the injured kidney during IR (Fig. 1B) and cisplatin nephrotoxicity (Fig. 1, C and D). In injured kidneys, the positive staining for meprin A was found to be extracellular toward the basolateral plasma membrane after both IR (Fig. 1, A and B) and cisplatin nephrotoxicity (Fig. 1, C and D). Na/K-ATPase showed prominent staining in the basolateral surface of distal tubules and light staining in proximal tubules. We further evaluated meprin A distribution in the total, cytosolic, and membrane fractions prepared from kidneys following IR- and cisplatin-induced AKI by Western blot using meprin α- and β-specific antibodies. In control kidneys, meprin β was present in the membrane fraction and was not detected in the cytosolic fraction (Fig. 2A). The detection of an 80-kDa processed form in the membrane fraction from ischemic kidney suggests that meprin β has been cleaved during injury (Fig. 2A, upper panel). This meprin β was detected as a part of meprin A because we also observed detection of meprin α in these fractions (Fig. 2A, lower panel); however, no processed meprin α was observed in the membrane fraction from ischemic kidneys. We also examined meprin A in the urine from mice subjected to IR injury. As shown in Fig. 2B, a urinary meprin β fragment, which is undetectable in the urine of control mice, increased markedly during the progression of IR-induced AKI. Meprin α not bound to meprin β was detected in the control urine samples (Fig. 2B). The urinary excretion of the meprin β fragment preceded the rise in serum creatinine and BUN. In addition, we have recently reported that a soluble form of meprin A is secreted in the urine during cisplatin-induced AKI (14). Thus, these studies along with the evidence that meprin A is redistributed in the kidney, processed in the membrane fraction, and detected in the urine during AKI provide support that meprin A may be shed from the membranes during renal injury.

FIGURE 1.

Meprin A distribution in kidneys of mice subjected to ischemia-reperfusion or cisplatin injury. A–D, double-immunofluorescence of meprin A (red) and Na/K-ATPase (green) in kidney sections of control mice (A and C) and mice subjected to IR (24 h of reperfusion after 45 min of ischemia) (B) or cisplatin injury (D). Kidney tissue was fixed in phosphate-buffered 4% formalin and paraffin-embedded. Tissue sections (8 μm) were incubated with goat polyclonal anti-meprin-β and rabbit polyclonal anti-Na+/K+-ATPase antibodies overnight. After washing with PBS, slices were incubated with secondary antibodies from Molecular Probes (donkey anti-goat Alexa Fluor 594 (red) and donkey anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 488 (green). Nuclei were stained with DAPI. Epifluorescence pictures were recorded on an Olympus (IX51, IX71, or BX51) microscope.

FIGURE 2.

Shedding of meprin β after IR and cisplatin (CP) injury. A, total homogenates, cytosolic and membrane fractions were prepared from kidneys of control mice and mice subjected to 24 h of IR injury and probed for meprin β by Western blot. ctrl total, control total. B, urine samples (normalized for protein content) from control mice and mice subjected to IR injury (6 and 11 h of reperfusion injury after 30 min of ischemia, as indicated) were probed for meprin β and meprin α by Western blot. Recombinant human promeprin β lacking its membrane anchor purified from HEK293 cells described earlier (21) is shown as a reference control in last lane. The individual lanes as shown were obtained from the same Western blot.

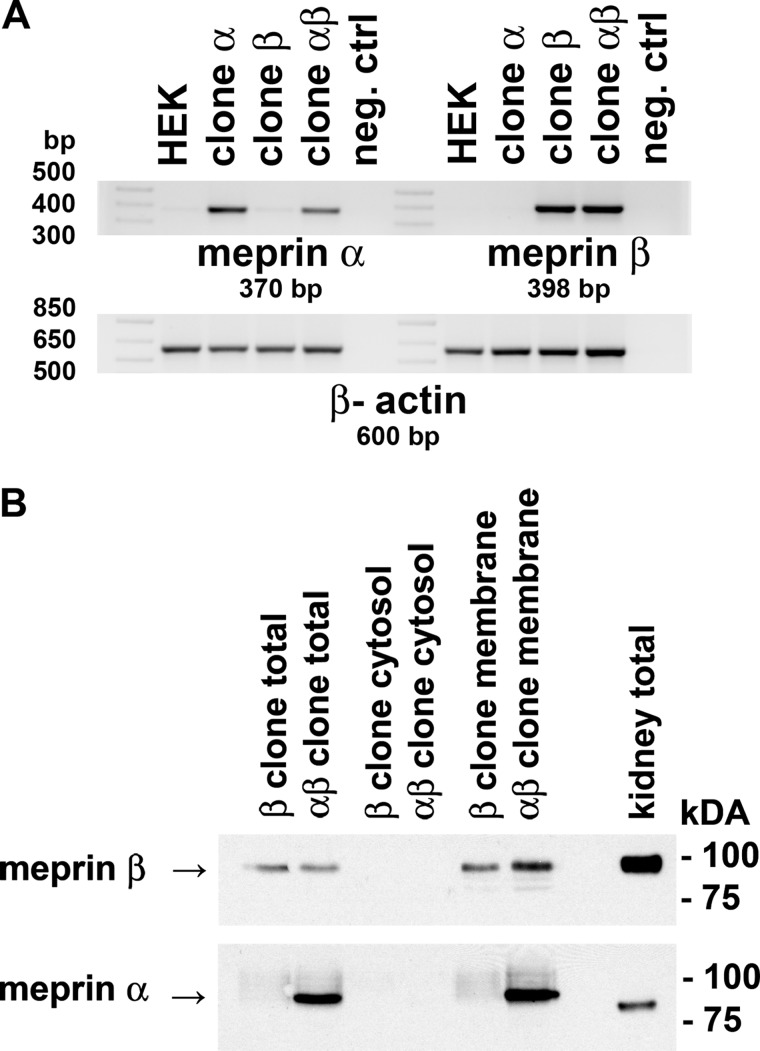

Characterization of Meprin β and Meprin αβ (Meprin A) Stable Cell Lines

Meprin A, composed of α and β subunits, is the major form of meprin present in the apical membranes of renal proximal tubules (10–12) and is anchored in the membranes via the β subunit. To test whether a specific protease is involved in the shedding of meprin A, we generated stable clones of HEK293 cells that express meprin β alone and both α and β, which represents meprin A. Meprin A clones were generated by co-transfection with both meprin α and meprin β expression plasmids. Meprin β- and meprin αβ-expressing (meprin A) clones were first verified by RT-PCR (Fig. 3A). Western blot analysis using meprin β antibodies showed meprin β protein expression in total cell lysates and membranes of HEK293-meprin β transfectants (clone β) as well as in meprin αβ co-transfectants (clone αβ) (Fig. 3B). The negative controls are represented by untransfected HEK293 cells that did not express mRNA for meprin α and meprin β. Meprin α protein was detected in αβ co-transfectants. Meprin β was barely detected in the cytosolic fractions of these transfectants. Meprin β in the transfectants was membrane-associated (Fig. 3B), confirming that meprin β is anchored to the membranes in both meprin β and meprin αβ (meprin A) clones. The meprin β transfectant and meprin αβ co-transfectant were used for the experiments to identify the sheddase involved in the release of meprin β and meprin A, respectively.

FIGURE 3.

Characterization of meprin-expressing HEK293 cell lines. A, RT-PCRs for meprin β mRNA expression in stable meprin β HEK293 transfectants and for both meprin α and meprin β mRNA expression in stable meprin αβ co-transfectants were performed. Negative control lane (neg. ctrl) represents RT-PCR in the absence of the cDNA template. PCR products were separated on a 1% agarose gel stained with ethidium bromide. β-Actin is shown as a loading control. B, total cell lysates, membrane, and cytosolic fractions of HEK cells stably transfected with meprin β alone or co-transfected with meprin α and β expression plasmids were assayed for protein expression of meprin β and meprin α by Western blot. Total lysate of an untreated C57BL/6n mouse kidney is shown for comparison. Aliquots containing equal protein amounts were probed with a meprin β- or meprin α-specific antibody, and signals were detected with ECL reagent.

Effect of Various Classes of Protease Inhibitors in Shedding of Meprin β in Meprin β- and αβ (Meprin A)-expressing Stable Cell Lines

To identify the protease responsible for the shedding of meprin β from the meprin β and meprin αβ transfectants, we first examined the ability of inhibitors of major classes of proteases to impede the release of soluble meprin β into the media. The cleavage or shedding of membrane-associated proteins is usually induced by stimuli such as PMA (28–30). Thus, we tested both constitutive shedding as well as induction of meprin β shedding by phorbol ester in meprin β and meprin A transfectants and then examined the effect of various protease inhibitors on the shedding. In both the meprin β and meprin αβ (meprin A) transfectants, constitutive meprin β shedding was prominent, but shedding was slightly induced by PMA (Fig. 4, A and B). The shedding of meprin β into the media was significantly inhibited by TAPI-1 (Fig. 4A), a broad spectrum inhibitor of the ADAM family of proteases (31). The broad spectrum metalloproteinase (MMP) inhibitor GM6001 and the specific MMP2/9 inhibitor-I had some effect on meprin β shedding but much less than the hydroxamate inhibitor TAPI-1 (Fig. 4A). Both constitutive and PMA-induced shedding of meprin A in the meprin αβ transfectants were significantly inhibited by the hydroxamate inhibitor TAPI-1 (Fig. 4B). The shedding of meprin A was unaffected by the γ-secretase inhibitor DAPT, plasmin inhibitor d-VFK-CMK, or MMP2/9 inhibitor-1. A marked inhibition on shedding was observed with the MMP inhibitor GM6001, but it was less than TAPI-1 (Fig. 4B). These studies suggest that a member of the ADAM family of proteases is involved in the shedding of meprin β and meprin A. We also examined the effect of the calcium ionophore IM that has been shown to induce shedding of membrane proteins. Shedding in response to IM was significantly induced in both meprin β and αβ clones. IM-induced shedding was significantly inhibited by TAPI-1 (Fig. 4, C and D). The shed meprin β was not released in its active form as it still contained the prodomain as detected by a prodomain-specific meprin β antibody (Fig. 4, E and F). We also examined whether the meprin αβ transfectant sheds meprin α in addition to meprin β. As shown in Fig. 4G, meprin α was also detected in the medium along with meprin β in the meprin αβ transfectant.

FIGURE 4.

Effect of various protease inhibitors on meprin β shedding in meprin β and meprin αβ clones in the presence and absence of PMA and IM. A, effect of protease inhibitors on shedding of meprin β in HEK cells stably transfected with meprin β in the presence of PMA. The indicated cells were treated with 50 nm PMA for 30 min prior to the addition of 25 μm TAPI-1, 25 μm DAPT, 10 μm GM6001, 100 nm d-VFK-CMK, or 44 μm MMP2/9-1 inhibitors. Medium supernatants were centrifuged for 30 min at 100,000 × g to remove cellular debris, and aliquots of equal protein content were analyzed by Western blot for the presence of meprin β (proMeprin β lane). Recombinant human promeprin β lacking its membrane anchor purified from HEK293 cells described earlier (21) is shown as a reference (left panel). Albumin detected by Ponceau S stain is shown as a loading control. Western blot band intensities were evaluated by densitometry normalized to those observed in medium supernatant of the corresponding PMA-treated clones (right panel). Error bars represent S.E., n = 4. **, p < 0.01, ***, p < 0.001. B, effect of protease inhibitors on secretion of meprin β in HEK cells stably co-transfected with meprin α and meprin β (meprin A) in the presence of PMA. Cells were treated with inhibitors in the presence and absence of PMA and processed for shedding of meprin β in the medium (left panel). Western blot band intensities were quantified by densitometry (right panel). Error bars represent S.E., n = 4. *, p < 0.05, ***, p < 0.001. C, effect of protease inhibitors on shedding of meprin β in HEK cells stably transfected with meprin β in the presence of IM. The indicated cells were treated with 2.5 μm IM for 30 min prior to the addition of 25 μm TAPI-1, 25 μm DAPT, 10 μm GM6001, 100 nm d-VFK-CMK, or 44 μm MMP2/9-1 inhibitors. Medium supernatants were centrifuged for 30 min at 100,000 × g to remove cellular debris and aliquots of equal protein content analyzed by Western blot for the presence of meprin β. Recombinant human promeprin β (proMeprin β lane) lacking its membrane anchor purified from HEK293 cells described earlier (21) is shown as a reference (left panel). Albumin detected by Ponceau S stain is shown as a loading control. Western blot band intensities were evaluated by densitometry normalized to those observed in medium supernatant of the corresponding IM treated clones (right panel). Error bars represent S.E., n = 4. *, p < 0.05, **, p < 0.01, ****, p < 0.0001. D, effect of protease inhibitors on secretion of meprin β in HEK cells stably co-transfected with meprin α and meprin β (meprin A) in the presence of IM. Cells were treated with inhibitors in the presence and absence of IM and processed for shedding of meprin β in the medium (left panel). Western blot band intensities were quantified by densitometry (right panel). Error bars represent S.E., n = 4. **, p < 0.01. E and F, detection of promeprin β shed from HEK cells. Western blots shown in panels C and D, respectively, were reprobed with a meprin β prodomain-specific antibody. G, detection of meprin β and meprin α shed from HEK cells stably co-transfected with meprin β and meprin α treated with IM or PMA in the presence or absence of TAPI-1.

ADAM Family Members Are Involved in Shedding of Meprin β in Meprin β- and αβ (Meprin A)-expressing Stable Cell Lines

Among the ADAM family members, ADAM9, ADAM10, and ADAM17 are well known to play a role in the shedding of growth factor receptors and other integral membrane proteins (31–33). Thus, we initiated studies to examine whether one of these ADAMs may be involved in the shedding of meprin A. GI254023X and GW280264X are potent ADAM inhibitors that allow discrimination in the activities of the major sheddases ADAM10 and ADAM17 (24). GW280264X is known to be equally effective in inhibiting both ADAM10 and ADAM17, with an IC50 of 11.5 and 8.0 nm for recombinant ADAM10 and ADAM17, respectively (35). GI254023X is more effective for ADAM10 than ADAM17, with an IC50 of 5.3 nm for recombinant ADAM10 and an IC50 of 541 nm for recombinant ADAM17 (36). Based on published work, we used varying concentrations of each inhibitor to assess meprin β shedding in the medium of meprin β and meprin αβ HEK clones. As shown in Fig. 5, A and B, in both meprin β and meprin αβ transfectants, the ADAM10 inhibitor GI254023X was more effective in blocking shedding of meprin β than the ADAM 10/ADAM17 inhibitor GW280264X, consistent with the notion that ADAM10 is the primary protease involved in the shedding of meprin A. Because GI254023X is a moderate inhibitor of ADAM9 with an IC50 of 280 nm (37), the possibility that ADAM9 is also involved cannot be ruled out from this experiment. As shown in Fig. 5C, ADAM9, ADAM10, and ADAM17 are expressed by HEK cells.

FIGURE 5.

Effect of specific inhibitors of the ADAM family of proteases on meprin β shedding in meprin β and meprin αβ clones. A, HEK293 cells stably transfected with meprin β were treated with highly specific inhibitors of ADAM10 and ADAM17 in the presence or absence of PMA (30 ng/ml) for 4 h. The inhibitors used were GI254023X (2 μm) and GW280264X (2 μm). Medium supernatants were centrifuged for 30 min at 100,000 × g to remove cellular debris, and aliquots of equal protein content were analyzed by Western blot for the presence of meprin β (left panel). The individual lanes as shown were obtained from the same Western blot. Recombinant human promeprin β lacking its membrane anchor purified from HEK293 cells described earlier (21) is shown as a reference. Western band intensities were evaluated by densitometry normalized to those observed in medium supernatant of the corresponding untreated clones (right panel). Error bars represent S.E., n = 3. **, p < 0.01, ***, p < 0.001. B, HEK293 cells stably co-transfected with meprin αβ (meprin A) were treated with highly specific inhibitors of ADAM10 and ADAM17 in the presence and absence of PMA (30 ng/ml) for 4 h as described for panel A. Medium supernatants were analyzed by Western blot for the presence of meprin β (left panel). The individual lanes as shown were obtained from the same Western blot. Western band intensities were evaluated by densitometry normalized to those observed in medium supernatant of the corresponding untreated clones (right panel). Error bars represent S.E., n = 3, *, p < 0.05, ****, p < 0.0001. C, untransfected HEK293 cells were tested for the presence of ADAM9, ADAM10, and ADAM17 mRNA by RT-PCR using human ADAM9-, ADAM10-, and ADAM17-specific primers as described under “Experimental Procedures.” neg. control, negative control.

Effect of ADAM9, ADAM10, and ADAM17 siRNA Knockdown on Meprin β and Meprin A Shedding

We next examined the effect of siRNA-mediated down-regulation of ADAM9, ADAM10, or ADAM17 on meprin A and meprin β shedding. As depicted in Fig. 6A, the ADAM10 siRNA was very effective in down-regulating the level of ADAM10 protein, whereas a scrambled siRNA had no appreciable effect. Similar results were obtained with siRNA targeting ADAM17 (Fig. 6B). The ADAM10 siRNA elicited the most significant reduction in meprin β shedding in both meprin β (Fig. 6C) and meprin αβ (Fig. 6D) transfectants, with a more pronounced effect on the shedding of meprin A in the meprin αβ transfectants. In meprin αβ cells, meprin β shedding was reduced to 14% of control (p < 0.001), and with PMA pretreatment, it was reduced to 21% (p < 0.01), whereas in meprin β cells, meprin β shedding was reduced to 30% of control (p < 0.05), and when pretreated with PMA, it was reduced to 82% versus 514% control. Thus, ADAM10 siRNA was most effective in preventing meprin β shedding, and ADAM 9 and ADAM17 siRNAs had little effect on the shedding of meprin β. These studies indicate that among these ADAMs, ADAM10 is the major sheddase involved in the shedding of meprin β and meprin A.

FIGURE 6.

Effect of siRNAs to ADAM9, ADAM10, and ADAM17 on meprin β shedding in meprin β and meprin αβ-expressing clones in the absence and presence of PMA or IM. A, ADAM10 expression was knocked down with siRNA pools to human ADAM10 in HEK293 or HEK cells stably transfected with meprin β or co-transfected with meprin β and meprin α. Scrambled siRNA was used as a negative control. Forty-eight hours after transfection, cells were incubated with PMA (30 ng/ml), IM (2.5 μm), or vehicle for 4 h. Cell lysates were analyzed for expression of ADAM10 by Western blot. α-Actinin served as a loading control. B, ADAM17 expression was knocked down with siRNA pools to human ADAM17 in HEK293 or HEK cells stably transfected with meprin β or co-transfected with meprin β and meprin α. Scrambled siRNA was used as a negative control. Forty-eight hours after transfection, cells were incubated with PMA (30 ng/ml), IM (2.5 μm), or vehicle for 4 h. Cell lysates were analyzed for expression of ADAM10 by Western blot; α-actinin served as a loading control. C, ADAM9, ADAM10, or ADAM17 expression was knocked down with siRNA pools to the indicated ADAMs in HEK293 cells stably transfected with meprin β. Scrambled siRNA was used as a negative control. Cells (48 h after transfection) were incubated with PMA (30 ng/ml) or vehicle for 4 h. Medium supernatants were harvested, and aliquots of equal protein amount were analyzed by Western blot for the presence of meprin β (left panels). Albumin detected by Ponceau S stain is shown as a loading control. This panel shows a representative Western blot from three independent experiments. Western band intensities were evaluated by densitometry normalized to those observed in medium supernatant of the corresponding clone treated with scrambled siRNA (right panel). Numbers in the diagrams represent the average band intensities, and bars represent the S.E. obtained from 3 independent experiments. *, p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. D, ADAM9, ADAM10, or ADAM17 expression was knocked down with siRNA pools to the indicated ADAMs in HEK293 cells stably co-transfected with meprin α and β. Cells (48 h after transfection) were incubated with PMA (30 ng/ml) or vehicle for 4 h. Medium supernatants were analyzed by Western blot for the presence of meprin β as described for panel B (left panel). Albumin detected by Ponceau S stain is shown as a loading control. This panel shows a representative Western blot from three independent experiments. Western band intensities were evaluated by densitometry normalized to those observed in medium supernatant of the corresponding clone treated with scrambled siRNA (right panel). Numbers in the diagrams represent the average band intensities, and bars represent the S.E. obtained from 3 independent experiments. **, p < 0.01, ***, p < 0.001.

Overexpression of ADAM10 Increases Meprin Shedding

Meprin β cells and meprin αβ cells were transiently transfected with a bovine ADAM10 expression construct, and meprin β shedding was assayed. Overexpression of ADAM10 was verified by Western blot (Fig. 7A). When overexpressed, ADAM10 increased shedding of meprin β in both meprin β and meprin αβ cells, with more pronounced effects observed in meprin αβ cells (Fig. 7, B and C).

FIGURE 7.

Overexpression of ADAM10 leads to increased shedding of meprin β shedding in meprin β- and meprin αβ-expressing clones. A, HEK293 cells stably transfected with meprin β or co-transfected with meprin β and meprin α were transiently transfected with bovine ADAM10-HA in pcDNA3, empty vector as control, or Lipofectamine 2000 alone (LF only). Cell lysates were prepared 48 h after transfection, and aliquots of equal protein amount were analyzed by Western blot for ADAM10. α-Actinin was used as a loading control. This panel shows a representative Western blot from five independent experiments. B, HEK293 cells stably transfected with meprin β or co-transfected with meprin α and β were transiently transfected with bovine ADAM10-HA in pcDNA3, empty vector as control, or Lipofectamine 2000 alone (LF only). Medium supernatants were harvested 48 h after transfection and analyzed by Western blot for meprin β shedding (left panel). This panel shows a representative Western blot from five independent experiments. Western band intensities were evaluated by densitometry (right panel). Band intensities of clones transfected with empty vector were used as controls for normalization. Numbers in the diagrams represent the average band intensities, and bars represent the S.E. of the mean obtained from 4–5 independent experiments as indicated. **, p < 0.01, ***, p < 0.001.

ADAM10 Inhibition Prevents Meprin A Shedding in Primary Renal Tubular Epithelial Cells

Primary cell cultures of renal tubular epithelial cell were prepared from mouse kidneys as described (25, 26). Both constitutive as well as PMA- and ionomycin-induced shedding of meprin A in the primary renal tubular epithelial cells was markedly prevented by the hydroxamate inhibitor TAPI-1 and the ADAM10-specific inhibitor GI254023X (Fig. 8).

FIGURE 8.

Meprin β shedding in primary renal tubular epithelial cells (RTEC) treated with inhibitors TAPI-1 or GI254023X in the presence or absence of PMA and ionomycin. Primary renal tubular epithelial cells were treated with 50 nm PMA or 2.5 μm ionomycin or vehicle (DMSO) for 30 min prior to the addition of 25 μm TAPI-1, 2 μm GI254023X, or vehicle. After 2 h, medium supernatants were collected and centrifuged at 500 × g for 5 min to remove cells, and the supernatants were centrifuged at 100,000 × g for 30 min to remove cellular debris. Aliquots of equal protein content were analyzed by Western blots for the presence of meprin β. Recombinant human promeprin β lacking its membrane anchor purified from HEK293 cells described earlier (21) is shown as a reference (left panel). Albumin detected by Ponceau S stain is shown as a loading control. Western blot intensities were evaluated by densitometry normalized to those observed in medium supernatants of the corresponding control (right panel). Numbers represent the average of 5 independent experiments. Error bars represent S.E., n = 5. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001.

DISCUSSION

Our studies have demonstrated that meprin A is shed during renal ischemia-reperfusion injury. Double-immunofluorescence staining of control kidney sections with meprin β and Na/K-ATPase also demonstrated that the exclusive localization of meprin A at the apical brush-border membranes of the proximal tubules is altered and redistributed toward the underlying basement membrane of the injured kidney during IR. When meprin β distribution in the total, cytosolic, and membrane fractions prepared from kidneys from control and IR mice was evaluated, processed meprin β was detected in the membrane fraction of kidneys from 24 h of IR, but was not observed in the control kidneys. In addition, meprin β, undetected in the urine of control mice, was found to be markedly increased in the urine during the progression of AKI during renal ischemia-reperfusion injury. Importantly, urinary excretion of meprin β was detected much earlier than the rise in serum creatinine. In this IR-induced AKI model, significant serum creatinine begins to rise after 16 h of reperfusion period. AKI is typically diagnosed by measuring serum creatinine; however, it is well known that creatinine is a delayed indicator during acute changes in kidney function and increases significantly only after substantial kidney injury occurs (38). Detection of urinary excretion of meprin β earlier than the rise in serum creatinine suggests that urinary excretion of meprin β can be further explored as a potential biomarker for AKI. Our previous studies have also detected a soluble form of meprin A in the urine of mice subjected to cisplatin nephrotoxicity (14). Taken together, these studies provided evidence that meprin A is proteolytically shed during AKI.

We have previously demonstrated that meprin A purified from the rat kidney is capable of degrading components of the extracellular matrix including collagen IV, fibronectin, laminin, and nidogen in vitro (16, 17). Consistent with the purified meprin A from rat kidney, recombinant human meprin A and meprin β were shown to degrade extracellular matrix proteins in vitro (18, 19). Meprin A has also been shown to proteolytically process bioactive peptides, cytokines, peptide hormones, and the tight junction proteins E-cadherin and occludin in vitro (11, 22, 23, 39, 40). Meprin B has been shown to cleave pro-interleukin-1β (20, 21), pro-interleukin-18 (41), pro-collagen III (42), amyloid precursor protein (43), tumor growth factor α (TGF-α) (44), tenascin-C (45), E-cadherin (46), epithelial sodium channel (47), and vascular endothelial growth factor A (VEGF-A) (48). The ability of meprin B to degrade extracellular matrix components has been implicated in cell migration of leukocytes of mesenteric lymph nodes (5) and invasion of tumor cells that express meprin (6). Although meprin isoforms display different substrate specificities (23), a clear pathophysiological role of meprin-mediated cleavage has yet to be established. Our recent studies demonstrated that all meprin isoforms (both homo-dimer and hetero-dimer meprin A and meprin B) can produce biologically active interleukin-1β from its inactive proform in vitro and in vivo (20, 21), suggesting that meprins may play an important role in inflammatory processes in addition to their ability to degrade extracellular matrix components. Thus, redistribution and shedding of meprin A into places other than apical membranes during IR injury could be deleterious to the kidneys due to the enormous proteolytic activity of meprin A.

In these studies, we have identified the major protease involved in the shedding of meprin A. Using pharmacological and genetic approaches, we have demonstrated that ADAM10 is the key ADAM metalloproteinase responsible for the constitutive and PMA- as well as IM-induced shedding of meprin A (HEK-meprin αβ transfectant) and meprin β (HEK-meprin β transfectant). A specific inhibitor of ADAM10 and siRNA silencing of ADAM10 markedly prevented the release of meprin β and meprin A, whereas overexpression of ADAM10 led to an increase in the shedding of meprin β and meprin A. The involvement of ADAMs in the shedding of meprin A suggests that ADAM10 may play an important role in the pathophysiology of AKI. Ectodomain cleavage of the β subunit of meprin A would result in the release of the αβ hetero-dimer during injury (Fig. 9). The term ADAM (a disintegrin and metalloprotease) signifies disintegrin-like and metalloproteinase-like, two distinct properties of these enzymes that are involved in cell adhesion as well as metalloproteinase activities. The ADAM family of proteases is composed of multidomain type I transmembrane proteases of the metzincin family (49–51) that play important roles in the proteolysis of cell surface proteins including receptors, cytokines, and adhesion molecules. Among the 38 members known so far, ADAM8, ADAM9, ADAM10, ADAM12, ADAM15, ADAM17, ADAM28, and ADAM33 have been identified to possess proteolytic activity. They cleave transmembrane cell surface proteins within the extracellular domains, resulting in the shedding of the ectodomain. ADAM10 and ADAM17 are the best characterized ADAMs that are involved in the ectodomain shedding of integral membrane proteins. ADAM10 has been identified to release the extracellular domains of key transmembrane proteins including cell adhesion molecules, cadherins and nectin-1, chemokines, Alzheimer disease-associated amyloid precursor protein (APP), ephrins, Notch receptors, IL-6R, anti-aging protein Klotho, FasL, CD44, and EGF (34, 52, 53). Thus, shedding of key proteins by ADAM10 may play important roles in chemotaxis, inflammation, cell-cell adhesion, and induction of apoptosis (54). In transfected COS-1 cells, PMA-induced ectodomain shedding of human meprin β has been previously reported (55, 56). The authors reported that TAPI-1 was capable of inhibiting the release of human meprin β. They further showed that tumor necrosis factor-α-converting enzyme (TACE)-deficient fibroblasts, when transfected with human meprin β, did not shed meprin β in response to PMA. Based on these results, tumor necrosis factor-α-converting enzyme or ADAM 17 was suggested to be involved in the PMA-induced shedding of human meprin β. In these studies, however, the specific role of ADAM10 in meprin β shedding was not identified. In addition, ADAMs responsible for meprin αβ (meprin A) shedding as well as for the constitutive shedding of meprin β were not identified.

FIGURE 9.

Illustration of meprin A ectodomain shedding with putative cleavage sites by ADAM10. The picture represents meprin A in the hetero-tetrameric form β2α2. The two β subunits provide the membrane anchor, and the α subunits are covalently linked to the β subunits by disulfide bridges. Putative cleavage sites by ADAM10 are located at the junction of the AM and the EGF-like domain. The panel on the right shows the individual domains of a meprin β subunit.

ADAM17 is involved in the shedding of membrane proteins including TNF-α and its receptor TNFRI, IL-6R, L-selectin, and ligands of the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), adhesion molecules, APP, colony-stimulating factor 1, and growth factors (34, 52, 57, 58). Although ADAM10 along with ADAM9 and ADAM17 have been characterized as α-secretases based on the cleavage of APP within the Aβ domain (59), it is ADAM10 that is the physiologically relevant and the constitutive α-secretase in primary neurons (60, 61) that are affected in Alzheimer disease. ADAM10 is highly expressed in most mammalian cell types and thus is known as MADM (mammalian disintegrin-metalloprotease). Using epidermis-specific Adam10 conditional knock-out mice, ADAM10 was identified as the processing enzyme for Notch in the epidermis in vivo and the crucial sheddase necessary to mediate epidermis-specific Notch signaling (62). It is generally observed that induced ectodomain shedding is mediated by ADAM17 and constitutive shedding is mediated by ADAM10 (34, 57, 63). However, both constitutive and stimulated shedding of human IL-6R (63) and nectin −1 (64) by ADAM10 have also been observed.

Currently, there is limited information available on the role of ADAM10 in the shedding of membrane-anchored proteins in AKI. ADAM10 is highly expressed in the proximal tubules of the kidney (65) and therefore may play an important role in shedding of meprin A and other transmembrane proteins during AKI. ADAM10 was recently shown to mediate shedding of APLP2, a member of the amyloid precursor protein family in opossum kidney proximal tubule cells (65). Inhibition of ADAM10 activity attenuated the IFN-γ-induced release of soluble proinflammatory chemokine CXCL16 in distal tubular cells (66). Although CXCL16 and ADAM10 were found to be co-localized in distal tubules in normal and transplanted kidney (66), the role of ADAM10 in the release of CXCL16 in vivo is yet to be established. The role of ADAM10 in the shedding of meprin A during AKI is crucial in view of the role of meprins in the pathogenesis of ischemia-reperfusion- and cisplatin-induced AKI in mice and rats. Meprin A shedding in response to AKI would be important due to its enormous potential role in protein and peptide degradation. Meprin β-deficient mice were markedly protected from ischemia-reperfusion injury (13). The meprin inhibitor actinonin provided marked protection against rat renal ischemia-reperfusion injury as well as hypoxia-reoxygenation injury in kidney slices (67). Actinonin preserved renal morphology and lowered BUN and serum creatinine levels both after and before the onset of renal sepsis induced by cecal ligation puncture (15). In addition, in this mouse model of sepsis, actinonin also prevented the fall in renal capillary perfusion even when administered after the onset of sepsis injury (15). In response to LPS-induced sepsis, meprin A-deficient mice displayed improved renal function and decreased nitric oxide, IL-1β, and TNF-α levels (68), suggesting that meprin A exacerbated renal injury in response to LPS. Recently, meprin was shown to exacerbate ischemia-reperfusion-induced renal injury in male rats. Pre-ischemic treatment with actinonin (10 or 30 mg/kg, intravenous) dose-dependently attenuated ischemia-reperfusion-induced renal injury in male rats, but failed to improve the renal injury in female rats (69). Previous studies demonstrated that, in response to IR injury and cisplatin nephrotoxicity, mouse strains expressing low levels of meprin A exhibited significantly less tubular necrosis and lower serum creatinine and BUN values when compared with normal C57BL/6 mice (14, 70). Moreover, active meprin A purified from rat kidney was found to be cytotoxic in renal tubular epithelial cells in culture (67), further suggesting a detrimental role of meprins during renal injury.

In summary, our studies have demonstrated that meprin A anchored to the apical membranes of proximal tubules is shed in response to IR injury. The IR-induced shedding of meprin A was evident from the altered distribution, proteolytic processing in the membrane fraction, and excretion in the urine. Both PMA-stimulated and IM-stimulated ectodomain shedding of meprin β in HEK cell lines expressing meprin β alone and meprin α and meprin β combined for the expression of meprin A. Using pharmacological and genetic approaches, the major proteolytic enzyme responsible for the shedding of meprin A as well as meprin β was identified as ADAM10. Thus, a part of the effects of meprin A in renal injury may be attributed to the release of meprin A by ADAM10. Inhibiting ADAM10 activity, therefore, could be of therapeutic benefit in AKI. Future studies will examine whether a specific inhibitor of ADAM10 provides protection from AKI.

Acknowledgments

We thank Judith Bond, Ph.D., for generously providing polyclonal antibody to meprin α during the course of this study. We thank Dr. Rolf Postina for kindly providing the bovine ADAM10-HA/pcDNA3 construct. We also thank Cindy Reid for assistance with formatting and critical proofreading of the manuscript.

Addendum

While this paper was under review, another study reported that ADAM10 is involved in meprin β shedding (71).

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant R01 DK081690. This work was also supported by Veterans Affairs Merit Awards BX000538 and BX000828 (to G. P. K. and R. K. H., respectively).

- AKI

- acute kidney injury

- ADAM

- a disintegrin and metalloproteinase

- IR

- ischemia-reperfusion

- PMA

- phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate

- IM

- ionomycin

- TAPI-1

- TNF-α protease inhibitor-1

- DAPT

- N-[N-(3,5-difluorophenacetyl)-l-alanyl]-S-phenylglycine t-butyl ester

- ECM

- extracellular matrix

- MMP

- metalloproteinase

- APP

- amyloid precursor protein

- IL-6R

- IL-6 receptor

- CMK

- chloromethyl ketone

- DMSO

- dimethyl sulfoxide

- BUN

- blood urea nitrogen.

REFERENCES

- 1. Sterchi E. E., Stöcker W., Bond J. S. (2008) Meprins, membrane-bound and secreted astacin metalloproteinases. Mol. Aspects Med. 29, 309–328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Becker-Pauly C., Höwel M., Walker T., Vlad A., Aufenvenne K., Oji V., Lottaz D., Sterchi E. E., Debela M., Magdolen V., Traupe H., Stöcker W. (2007) The α and β subunits of the metalloprotease meprin are expressed in separate layers of human epidermis, revealing different functions in keratinocyte proliferation and differentiation. J. Invest. Dermatol. 127, 1115–1125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lottaz D., Hahn D., Müller S., Müller C., Sterchi E. E. (1999) Secretion of human meprin from intestinal epithelial cells depends on differential expression of the α and β subunits. Eur. J. Biochem. 259, 496–504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lottaz D., Maurer C. A., Hahn D., Büchler M. W., Sterchi E. E. (1999) Nonpolarized secretion of human meprin α in colorectal cancer generates an increased proteolytic potential in the stroma. Cancer Res. 59, 1127–1133 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Crisman J. M., Zhang B., Norman L. P., Bond J. S. (2004) Deletion of the mouse meprin β metalloprotease gene diminishes the ability of leukocytes to disseminate through extracellular matrix. J. Immunol. 172, 4510–4519 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Matters G. L., Manni A., Bond J. S. (2005) Inhibitors of polyamine biosynthesis decrease the expression of the metalloproteases meprin α and MMP-7 in hormone-independent human breast cancer cells. Clin. Exp. Metastasis 22, 331–339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Oneda B., Lods N., Lottaz D., Becker-Pauly C., Stöcker W., Pippin J., Huguenin M., Ambort D., Marti H. P., Sterchi E. E. (2008) Metalloprotease meprin β in rat kidney: glomerular localization and differential expression in glomerulonephritis. PLoS One 3, e2278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bertenshaw G. P., Norcum M. T., Bond J. S. (2003) Structure of homo- and hetero-oligomeric meprin metalloproteases: dimers, tetramers, and high molecular mass multimers. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 2522–2532 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Sterchi E. E. (2008) Special issue: metzincin metalloproteinases. Mol. Aspects Med. 29, 255–257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kumar J. M., Bond J. S. (2001) Developmental expression of meprin metalloprotease subunits in ICR and C3H/He mouse kidney and intestine in the embryo, postnatally and after weaning. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1518, 106–114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bond J. S., Matters G. L., Banerjee S., Dusheck R. E. (2005) Meprin metalloprotease expression and regulation in kidney, intestine, urinary tract infections and cancer. FEBS Lett. 579, 3317–3322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Craig S. S., Reckelhoff J. F., Bond J. S. (1987) Distribution of meprin in kidneys from mice with high- and low-meprin activity. Am. J. Physiol. 253, C535–540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bylander J., Li Q., Ramesh G., Zhang B., Reeves W. B., Bond J. S. (2008) Targeted disruption of the meprin metalloproteinase β gene protects against renal ischemia-reperfusion injury in mice. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 294, F480–490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Herzog C., Seth R., Shah S. V., Kaushal G. P. (2007) Role of meprin A in renal tubular epithelial cell injury. Kidney Int. 71, 1009–1018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wang Z., Herzog C., Kaushal G. P., Gokden N., Mayeux P. R. (2011) Actinonin, a meprin A inhibitor, protects the renal microcirculation during sepsis. Shock 35, 141–147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Walker P. D., Kaushal G. P., Shah S. V. (1998) Meprin A, the major matrix degrading enzyme in renal tubules, produces a novel nidogen fragment in vitro and in vivo. Kidney Int. 53, 1673–1680 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kaushal G. P., Walker P. D., Shah S. V. (1994) An old enzyme with a new function: purification and characterization of a distinct matrix-degrading metalloproteinase in rat kidney cortex and its identification as meprin. J. Cell Biol. 126, 1319–1327 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Köhler D., Kruse M., Stöcker W., Sterchi E. E. (2000) Heterologously overexpressed, affinity purified human meprin α is functionally active and cleaves components of the basement membrane in vitro. FEBS Lett. 465, 2–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kruse M. N., Becker C., Lottaz D., Köhler D., Yiallouros I., Krell H. W., Sterchi E. E., Stöcker W. (2004) Human meprin α and β homo-oligomers: cleavage of basement membrane proteins and sensitivity to metalloprotease inhibitors. Biochem. J. 378, 383–389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Herzog C., Haun R. S., Kaushal V., Mayeux P. R., Shah S. V., Kaushal G. P. (2009) Meprin A and meprin α generate biologically functional IL-1β from pro-IL-1β. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 379, 904–908 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Herzog C., Kaushal G. P., Haun R. S. (2005) Generation of biologically active interleukin-1 β by meprin B. Cytokine 31, 394–403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Sterchi E. E., Naim H. Y., Lentze M. J., Hauri H. P., Fransen J. A. (1988) N-Benzoyl-l-tyrosyl-p-aminobenzoic acid hydrolase: a metalloendopeptidase of the human intestinal microvillus membrane which degrades biologically active peptides. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 265, 105–118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bertenshaw G. P., Turk B. E., Hubbard S. J., Matters G. L., Bylander J. E., Crisman J. M., Cantley L. C., Bond J. S. (2001) Marked differences between metalloproteases meprin A and B in substrate and peptide bond specificity. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 13248–13255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ludwig A., Hundhausen C., Lambert M. H., Broadway N., Andrews R. C., Bickett D. M., Leesnitzer M. A., Becherer J. D. (2005) Metalloproteinase inhibitors for the disintegrin-like metalloproteinases ADAM10 and ADAM17 that differentially block constitutive and phorbol ester-inducible shedding of cell surface molecules. Comb. Chem. High Throughput Screen. 8, 161–171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Seth R., Yang C., Kaushal V., Shah S. V., Kaushal G. P. (2005) p53-dependent caspase-2 activation in mitochondrial release of apoptosis-inducing factor and its role in renal tubular epithelial cell injury. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 31230–31239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Bergin E., Levine J. S., Koh J. S., Lieberthal W. (2000) Mouse proximal tubular cell-cell adhesion inhibits apoptosis by a cadherin-dependent mechanism. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 278, F758–F768 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kaushal G. P., Haun R. S., Herzog C., Shah S. V. (2013) Meprin A metalloproteinase and its role in acute kidney injury. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 304, F1150-F1158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Endres K., Anders A., Kojro E., Gilbert S., Fahrenholz F., Postina R. (2003) Tumor necrosis factor-α converting enzyme is processed by proprotein-convertases to its mature form which is degraded upon phorbol ester stimulation. Eur. J. Biochem. 270, 2386–2393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Gasbarri A., Del Prete F., Girnita L., Martegani M. P., Natali P. G., Bartolazzi A. (2003) CD44s adhesive function spontaneous and PMA-inducible CD44 cleavage are regulated at post-translational level in cells of melanocytic lineage. Melanoma Res. 13, 325–337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Fitzgerald M. L., Wang Z., Park P. W., Murphy G., Bernfield M. (2000) Shedding of syndecan-1 and -4 ectodomains is regulated by multiple signaling pathways and mediated by a TIMP-3-sensitive metalloproteinase. J. Cell Biol. 148, 811–824 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Garton K. J., Gough P. J., Raines E. W. (2006) Emerging roles for ectodomain shedding in the regulation of inflammatory responses. J. Leukoc. Biol. 79, 1105–1116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Huovila A. P., Turner A. J., Pelto-Huikko M., Kärkkäinen I., Ortiz R. M. (2005) Shedding light on ADAM metalloproteinases. Trends Biochem. Sci. 30, 413–422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Deuss M., Reiss K., Hartmann D. (2008) Part-time α-secretases: the functional biology of ADAM 9, 10 and 17. Curr. Alzheimer. Res. 5, 187–201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Saftig P., Reiss K. (2011) The “A Disintegrin And Metalloproteases” ADAM10 and ADAM17: novel drug targets with therapeutic potential? Eur. J. Cell Biol. 90, 527–535 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Hundhausen C., Misztela D., Berkhout T. A., Broadway N., Saftig P., Reiss K., Hartmann D., Fahrenholz F., Postina R., Matthews V., Kallen K. J., Rose-John S., Ludwig A. (2003) The disintegrin-like metalloproteinase ADAM10 is involved in constitutive cleavage of CX3CL1 (fractalkine) and regulates CX3CL1-mediated cell-cell adhesion. Blood 102, 1186–1195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Scholz F., Schulte A., Adamski F., Hundhausen C., Mittag J., Schwarz A., Kruse M. L., Proksch E., Ludwig A. (2007) Constitutive expression and regulated release of the transmembrane chemokine CXCL16 in human and murine skin. J. Invest. Dermatol. 127, 1444–1455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Moss M. L., Rasmussen F. H., Nudelman R., Dempsey P. J., Williams J. (2010) Fluorescent substrates useful as high-throughput screening tools for ADAM9. Comb Chem High Throughput Screen 13, 358–365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Thadhani R., Pascual M., Bonventre J. V. (1996) Acute renal failure. N. Engl. J. Med. 334, 1448–1460 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Yamaguchi T., Fukase M., Sugimoto T., Kido H., Chihara K. (1994) Purification of meprin from human kidney and its role in parathyroid hormone degradation. Biol. Chem. Hoppe Seyler. 375, 821–824 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Bao J., Yura R. E., Matters G. L., Bradley S. G., Shi P., Tian F., Bond J. S. (2013) Meprin A impairs epithelial barrier function, enhances monocyte migration, and cleaves the tight junction protein occludin. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 305, F714–F726 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Banerjee S., Bond J. S. (2008) Prointerleukin-18 is activated by meprin β in vitro and in vivo in intestinal inflammation. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 31371–31377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Kronenberg D., Bruns B. C., Moali C., Vadon-Le Goff S., Sterchi E. E., Traupe H., Böhm M., Hulmes D. J., Stöcker W., Becker-Pauly C. (2010) Processing of procollagen III by meprins: new players in extracellular matrix assembly? J. Invest. Dermatol. 130, 2727–2735 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Jefferson T., Čauševič M., auf dem Keller U., Schilling O., Isbert S., Geyer R., Maier W., Tschickardt S., Jumpertz T., Weggen S., Bond J. S., Overall C. M., Pietrzik C. U., Becker-Pauly C. (2011) Metalloprotease meprin β generates nontoxic N-terminal amyloid precursor protein fragments in vivo. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 27741–27750 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Bergin D. A., Greene C. M., Sterchi E. E., Kenna C., Geraghty P., Belaaouaj A., Taggart C. C., O'Neill S. J., McElvaney N. G. (2008) Activation of the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) by a novel metalloprotease pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 31736–31744 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Ambort D., Brellier F., Becker-Pauly C., Stöcker W., Andrejevic-Blant S., Chiquet M., Sterchi E. E. (2010) Specific processing of tenascin-C by the metalloprotease meprin β neutralizes its inhibition of cell spreading. Matrix Biol. 29, 31–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Huguenin M., Müller E. J., Trachsel-Rösmann S., Oneda B., Ambort D., Sterchi E. E., Lottaz D. (2008) The metalloprotease meprin β processes E-cadherin and weakens intercellular adhesion. PLoS One 3, e2153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Garcia-Caballero A., Ishmael S. S., Dang Y., Gillie D., Bond J. S., Milgram S. L., Stutts M. J. (2011) (2010) Activation of the epithelial sodium channel by the metalloprotease meprin β subunit. Channels (Austin) 5, 14–22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Schütte A, Hedrich J, Stöcker W, Becker-Pauly C. (2010) Let it flow: morpholino knockdown in zebrafish embryos reveals a pro-angiogenic effect of the metalloprotease meprin α2. PLoS One 5, e8835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Edwards D. R., Handsley M. M., Pennington C. J. (2008) The ADAM metalloproteinases. Mol. Aspects Med. 29, 258–289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Klein T., Bischoff R. (2011) Active metalloproteases of the A Disintegrin and Metalloprotease (ADAM) family: biological function and structure. J. Proteome Res. 10, 17–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Murphy G. (2008) The ADAMs: signalling scissors in the tumour microenvironment. Nat. Rev. Cancer 8, 929–941 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Pruessmeyer J., Ludwig A. (2009) The good, the bad and the ugly substrates for ADAM10 and ADAM17 in brain pathology, inflammation and cancer. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 20, 164–174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Gibb D. R., Saleem S. J., Chaimowitz N. S., Mathews J., Conrad D. H. (2011) The emergence of ADAM10 as a regulator of lymphocyte development and autoimmunity. Mol. Immunol. 48, 1319–1327 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Crawford H. C., Dempsey P. J., Brown G., Adam L., Moss M. L. (2009) ADAM10 as a therapeutic target for cancer and inflammation. Curr. Pharm. Des. 15, 2288–2299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Hahn D., Pischitzis A., Roesmann S., Hansen M. K., Leuenberger B., Luginbuehl U., Sterchi E. E. (2003) Phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate-induced ectodomain shedding and phosphorylation of the human meprinβ metalloprotease. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 42829–42839 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Pischitzis A., Hahn D., Leuenberger B., Sterchi E. E. (1999) N-Benzoyl-l-tyrosyl-p-aminobenzoic acid hydrolase β (human meprin β): a 13-amino-acid sequence is required for proteolytic processing and subsequent secretion. Eur. J. Biochem. 261, 421–429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Le Gall S. M., Bobé P., Reiss K., Horiuchi K., Niu X. D., Lundell D., Gibb D. R., Conrad D., Saftig P., Blobel C. P. (2009) ADAMs 10 and 17 represent differentially regulated components of a general shedding machinery for membrane proteins such as transforming growth factor α, L-selectin, and tumor necrosis factor α. Mol. Biol. Cell 20, 1785–1794 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Blobel C. P. (2005) ADAMs: key components in EGFR signalling and development. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 6, 32–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Lichtenthaler S. F. (2011) α-Secretase in Alzheimer's disease: molecular identity, regulation and therapeutic potential. J. Neurochem. 116, 10–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Kuhn P. H., Wang H., Dislich B., Colombo A., Zeitschel U., Ellwart J. W., Kremmer E., Rossner S., Lichtenthaler S. F. (2010) ADAM10 is the physiologically relevant, constitutive α-secretase of the amyloid precursor protein in primary neurons. EMBO J. 29, 3020–3032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Jorissen E., Prox J., Bernreuther C., Weber S., Schwanbeck R., Serneels L., Snellinx A., Craessaerts K., Thathiah A., Tesseur I., Bartsch U., Weskamp G., Blobel C. P., Glatzel M., De Strooper B., Saftig P. (2010) The disintegrin/metalloproteinase ADAM10 is essential for the establishment of the brain cortex. J. Neurosci. 30, 4833–4844 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Weber S., Niessen M. T., Prox J., Lüllmann-Rauch R., Schmitz A., Schwanbeck R., Blobel C. P., Jorissen E., de Strooper B., Niessen C. M., Saftig P. (2011) The disintegrin/metalloproteinase Adam10 is essential for epidermal integrity and Notch-mediated signaling. Development 138, 495–505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Matthews V., Schuster B., Schütze S., Bussmeyer I., Ludwig A., Hundhausen C., Sadowski T., Saftig P., Hartmann D., Kallen K. J., Rose-John S. (2003) Cellular cholesterol depletion triggers shedding of the human interleukin-6 receptor by ADAM10 and ADAM17 (TACE). J. Biol. Chem. 278, 38829–38839 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Kim J., Lilliehook C., Dudak A., Prox J., Saftig P., Federoff H. J., Lim S. T. (2010) Activity-dependent α-cleavage of nectin-1 is mediated by a disintegrin and metalloprotease 10 (ADAM10). J. Biol. Chem. 285, 22919–22926 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Cong R., Li Y., Biemesderfer D. (2011) A disintegrin and metalloprotease 10 activity sheds the ectodomain of the amyloid precursor-like protein 2 and regulates protein expression in proximal tubule cells. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 300, C1366–1374 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Schramme A., Abdel-Bakky M. S., Gutwein P., Obermüller N., Baer P. C., Hauser I. A., Ludwig A., Gauer S., Schäfer L., Sobkowiak E., Altevogt P., Koziolek M., Kiss E., Gröne H. J., Tikkanen R., Goren I., Radeke H., Pfeilschifter J. (2008) Characterization of CXCL16 and ADAM10 in the normal and transplanted kidney. Kidney Int. 74, 328–338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Carmago S., Shah S. V., Walker P. D. (2002) Meprin, a brush-border enzyme, plays an important role in hypoxic/ischemic acute renal tubular injury in rats. Kidney Int. 61, 959–966 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Yura R. E., Bradley S. G., Ramesh G., Reeves W. B., Bond J. S. (2009) Meprin A metalloproteases enhance renal damage and bladder inflammation after LPS challenge. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 296, F135–144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Takayama J., Takaoka M., Yamamoto S., Nohara A., Ohkita M., Matsumura Y. (2008) Actinonin, a meprin inhibitor, protects ischemic acute kidney injury in male but not in female rats. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 581, 157–163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Trachtman H., Valderrama E., Dietrich J. M., Bond J. S. (1995) The role of meprin A in the pathogenesis of acute renal failure. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 208, 498–505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Jefferson T., Auf dem Keller U., Bellac C., Metz V. V., Broder C., Hedrich J., Ohler A., Maier W., Magdolen V., Sterchi E., Bond J. S., Jayakumar A., Traupe H., Chalaris A., Rose-John S., Pietrzik C. U., Postina R., Overall C. M., Becker-Pauly C. (2013) The substrate degradadome of meprin metalloproteases reveals an unexpected proteolytic link between meprin β and ADAM10. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 70, 309–333 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]