Background: Earlier reports indicate that O-GlcNAcylation might be protective in neurodegenerative disorders.

Results: Suppressing O-GlcNAcylation modulates autophagy to enhance the viability of neuronal cells expressing cytotoxic mutant huntingtin exon 1 protein (mHtt).

Conclusion: O-GlcNAcylation regulates the clearance of mHtt by modulating the fusion of autophagosomes with lysosomes.

Significance: This regulatory mechanism emerges as a novel therapeutic strategy for Huntington disease.

Keywords: Autophagy, Neurodegenerative Diseases, O-GlcNAcylation, Post-translational Modification, Protein Aggregation

Abstract

O-GlcNAcylation is an important post-translational modification of proteins and is known to regulate a number of pathways involved in cellular homeostasis. This involves dynamic and reversible modification of serine/threonine residues of different cellular proteins catalyzed by O-linked N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase and O-linked N-acetylglucosaminidase in an antagonistic manner. We report here that decreasing O-GlcNAcylation enhances the viability of neuronal cells expressing polyglutamine-expanded huntingtin exon 1 protein fragment (mHtt). We further show that O-GlcNAcylation regulates the basal autophagic process and that suppression of O-GlcNAcylation significantly increases autophagic flux by enhancing the fusion of autophagosome with lysosome. This regulation considerably reduces toxic mHtt aggregates in eye imaginal discs and partially restores rhabdomere morphology and vision in a fly model for Huntington disease. This study is significant in unraveling O-GlcNAcylation-dependent regulation of an autophagic process in mediating mHtt toxicity. Therefore, targeting the autophagic process through the suppression of O-GlcNAcylation may prove to be an important therapeutic approach in Huntington disease.

Introduction

O-GlcNAcylation is a glucose-dependent post-translational modification. When glucose enters the cell, ∼5% of it enters into the hexosamine biosynthetic pathway through a series of metabolic transformations and finally gets transformed into uridine 5′-diphospho-N-acetylglucosamine (UDP-GlcNAc) (1). This final product of the hexosamine biosynthetic pathway, among other functions, acts as a substrate of O-linked GlcNAcylation and is utilized by two antagonistic enzymes, O-linked N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase (OGT)6 and O-linked N-acetylglucosaminidase (OGA), which regulate the dynamic modification of different nucleo-cytoplasmic proteins. OGT catalyzes the addition of a single GlcNAc moiety to serine and/or threonine sites of various proteins, although OGA removes the same (2). O-GlcNAcylation has been shown to regulate many vital biological processes such as replication, transcription, translation, stress response, nutrient response, unfolded protein response, and intracellular protein trafficking (3–5). It is also emerging as an important regulatory mechanism in a number of complex diseases, such as diabetes, cancer, cardiovascular diseases, and in aging (5). OGT activity has been reported to be about 10 times more enriched in brain as compared with other tissues like liver, muscle, adipose, and heart (6) and has been shown to glycosylate many proteins linked to neurodegenerative diseases such as amyloid precursor protein, β-amyloid-associated protein (7), microtubule-associated Tau protein (8), synapsin (9), and neurofilament proteins (10). Recently, OGT was reported to play a protective role in Alzheimer disease (11) and is speculated to be protective in other neurodegenerative disorders such as Huntington disease, Parkinson disease, and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis.

Huntington disease is a neurodegenerative disorder characterized by the formation of intracellular aggregates of the mutant huntingtin (mHtt) (12, 13). The normal huntingtin gene codes for the huntingtin protein, which usually has up to 34 glutamine-coding (CAG) repeats (12, 13). The huntingtin protein having up to 34 glutamine repeats represents a normal functional protein, whereas expansion of CAG repeats coding for >40 glutamines as a repeat track results in a dominant mutation, a consequence of which is that the mutant Htt loses its proper folding state, tends to aggregate, and becomes cytotoxic (12, 13). The wild-type huntingtin protein plays important roles in normal functioning of the brain such as vesicular transport, neuronal gene transcription, and BDNF production (14) and may also function as an anti-apoptotic protein (15). The mHtt aggregates interfere with normal synaptic transmission (16), impair axonal transport of mitochondria (17), sequester crucial transcription factors (18), and hamper their functioning.

O-GlcNAcylation is a nutrient-sensitive protein modification. With the emerging understanding of the important roles of O-GlcNAcylation in various neurodegenerative disorders along with reports about glucose-dependent regulation of protein clearance machineries (19, 20) and that of protein aggregation-mediated toxicity (21, 22), we aimed to explore the role of this glucose-dependent post-translational modification in the regulation of mHtt-mediated toxicity and its clearance. We report here that suppression of O-GlcNAcylation increases basal autophagy flux by enhancing autophagosome-lysosome fusion and helps in the clearance of toxic aggregates of mutant huntingtin exon 1-coded protein, thereby increasing survival and suppressing the degenerative phenotypes in cellular and Huntington fly models, respectively.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Reagents and Antibodies

Cell culture media and drugs (azaserine, glucosamine, 3-methyladenine, and bafilomycin A1) were purchased from Sigma. Polyfect transfection reagent was from Qiagen India Pvt. Ltd., India. Antibodies were procured from following sources: anti-LC3 and anti-Myc for immunostaining (Cell Signaling Technology); anti-p62 (Enzo Life Sciences); anti-GFP and anti-Myc for immunoblots (Roche Applied Science); anti-HA as used in experiments done in Neuro2A cells and anti-O-GlcNAc and anti-γ-tubulin (Sigma). Rabbit polyclonal anti-hemagglutinin (used in experiments with Drosophila) was from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, and secondary antibodies were procured from Jackson ImmunoResearch Inc., except anti-rabbit conjugated with Cy3 (Sigma) and Alexa-Fluor 488 were from Molecular Probes.

Expression Constructs

Mammalian expression constructs were obtained from the following sources. The GFP-tagged truncated Huntingtin Q97 expression vector was generously provided by Dr. Lawrence Marsh (University of California at Irvine). Plasmid coding for OGA (Myc-tagged) was a kind gift from Dr. John A. Hannover (NIDDK, National Institutes of Health); the HA-tagged OGT was gifted by Dr. Gerald W. Hart (The Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD); the mRFP-GFP-LC3 construct was gifted by Dr. T. Yoshimori (National Institute for Basic Biology, Okazaki, Japan), and construct coding for the mutant form of α-synuclein as GFP fusion was a gift from Dr. Peter Lansbury (Harvard Medical School).

Cell Culture, Treatment, and Transfection

The experiments were conducted in the murine neuroblastoma cell line Neuro2A under normal glucose conditions (25 mm). Neuro2A cells were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (Sigma) supplemented with 10% (v/v) fetal calf serum, 100 units/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin. The cells were treated with 40 μm azaserine (inhibitor of O-GlcNAcylation), 10 mm glucosamine (inducer of O-GlcNAcylation), 100 nm bafilomycin A1 (inhibitor of the fusion of autophagosomes with lysosomes), and 10 mm 3-methyladenine (3MA; an inhibitor of autophagosome formation). The cells were transiently transfected with expression constructs at around 50% of confluence using PolyFect transfection reagent (Qiagen) as recommended by the manufacturer. Under these conditions, the transfection efficiency was consistent and around 70% as assessed by microscopic observation of the fluorescence positive cells transiently expressing the GFP-tagged protein. In all the experiments, the cells were harvested at 36 h post-transfection, and wherever required, treatment with the pharmacological agents was given for the last 12 h unless stated otherwise.

Fly Stocks and Rearing Condition

All fly stocks were maintained under uncrowded conditions at 24 ± 1 °C. For each experiment, regular or azaserine (250 μg/ml)-supplemented food was prepared from the same batch. Using the w1118;UAS-httex1p Q93/CyO (20) and w1118;GMR-GAL4 (21) fly stocks, appropriate genetic crosses were set to obtain w1118;UAS-httex1p Q93/GMR-GAL4 (GMR-GAL4 > UAS-httex1p) progeny. The GMR-GAL4 driver targets expression of the UAS-httex1pQ93 transgene in developing eye discs (23) and thereby induce retinal neurodegeneration (24). In some cases, Oregon R+ stock was used as wild type. Freshly hatched larvae for a given experiment were derived from a common pool of eggs of the desired genotype and reared in parallel on regular or azaserine-supplemented food.

We also reared larvae on food supplemented with glucosamine (1, 10, or 25 mg/ml). However, in each case, all the larvae died before reaching third instar stage, and therefore, no further studies on the effect of glucosamine on polyglutamine (polyQ) degeneration in the fly model could be carried out.

Immunostaining

Cells on coverslips were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in 1× PBS for 20 min followed by permeabilization for 5 min in 1× PBS with 0.05% Triton X-100. The expression of Myc-OGA and HA-OGT was checked by probing with anti-Myc or anti-HA antibodies followed by FITC- or TRITC-conjugated secondary antibodies, respectively. Nuclei were counterstained with 10 μm 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI). Images were obtained with a Nikon (Japan) Eclipse 80i fluorescence microscope using a ×10 or ×40 objective lens.

Eye discs from wandering late third instar GMR-GAL4 > UAS-httex1p Q93 larvae reared on normal or azaserine-supplemented food were dissected and immunostained as described previously (25) with anti-HA (1:80 dilution, Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Chromatin was counterstained with DAPI. Immunofluorescence-stained eye discs were examined with a Zeiss LSM 510 meta confocal microscope using appropriate lasers, dichroics, and filters.

Cell Death Assay

For the MTT assay, cells were treated with azaserine or glucosamine for 12 h or transfected for 36 h, and thereafter, cells were incubated with 0.5 mg/ml thiazolyl blue tetrazolium bromide (MTT) (Sigma) and chased for 2 h. After removal of the medium, cells were incubated with DMSO (100%) for 10 min to dissolve formazan crystals. The change in optical density was recorded through spectrophotometer at λ570 nm against background reading at λ650 nm. Alternatively, treated or transfected cells were fixed, permeabilized, and stained with DAPI as mentioned for immunostaining, and the apoptotic nuclei were scored in a blinded fashion as reported earlier (26).

Quantification of LC3-positive Cytoplasmic Puncta

Cells transiently expressing the tandem mRFP-GFP-LC3 construct were fixed, and the fluorescence images of about 50 cells for each set were examined using a Zeiss AxioImager 2 microscope outfitted with an ApoTome accessory. The green, red, and yellow puncta in the captured images were quantified using the co-localization macro in ImageJ software, as described (27).

Immunoblotting

Protein samples were resolved on 6–12% SDS-PAGE as required and transferred to nitrocellulose membrane (MDI, India). Thereafter, the membranes were blocked with either 5% nonfat dry milk powder or 5% BSA in 1× TBST and probed sequentially with the desired primary and secondary antibodies at their recommended dilutions followed by detection with a chemiluminescent detection kit (Supersignal West Pico, Pierce).

Filter Trap Assay

The filter trap assay was carried out essentially as described by Juenemann et al. (28). Briefly, the pellet fraction of the cell lysate was suspended in the benzonase buffer (1 mm MgCl2, 50 mm Tris/HCl, pH 8.0) and treated with an RNase/DNase mixture (50 units each; Fermentas) and incubated for 1 h at 37 °C. The reaction was arrested with the addition of 2× termination buffer (40 mm EDTA, 4% SDS, 100 mm DTT), and 50 μg of the sample was mixed in 2% SDS buffer (2% SDS, 150 mm NaCl, 10 mm Tris/HCl, pH 8.0) and filtered through a 0.2-μm pore size cellulose acetate membrane (GE Healthcare) using a slot blot apparatus (Bio-Rad). The filter membrane was used for immunodetection as described for the immunoblot.

Proteasome Activity Assays

Cells that were either transfected or treated with the indicated drugs (12 h) were harvested in lysis buffer (1× PBS, 0.1% Triton X-100, 0.5% Nonidet P-40), and the cleared lysate was used for the proteasome activity assay using a fluorogenic proteasome substrate (N-succinyl-Leu-Leu-Val-Tyr-7-amido-4-methylcoumarin; Calbiochem). Briefly, 10 μg of protein for each sample was incubated in a reaction buffer, and the generation of fluorescent signal was measured using a spectrofluorometer (PerkinElmer Life Sciences) as recommended by the manufacturer. Reactions in the presence of the proteasomal blocker, MG132, served as control.

Pseudopupil Analysis

Heads of 1-day-old GMR-GAL4 > UAS-httex1p Q93 flies, reared because the first instar larval stage on normal or azaserine-supplemented food, were decapitated, and the arrangement of photoreceptor rhabdomeres in the ommatidia of compound eyes was visualized by the pseudopupil technique (29) using ×63 (NA = 1.4) oil objective on a Nikon E800 microscope, and the images were recorded with a Nikon DXM 1200 digital camera. The total number of flies observed for each group was 50.

Phototaxis Assay

Phototaxis of adult flies was assayed using a Y maze consisting of a Y-shaped glass tube of 12-mm internal diameter and 30-cm length of each arm. Twenty replicates, each with 10 flies, were carried out for each feeding regime and age of flies. Wild-type Oregon R+ flies were used as positive control. The same sets of flies were used for phototaxis assay on days 0, 5, 10, and 15.

Statistical Analysis

Sigma Plot 11.0 software was used for statistical analysis. For cell biology assays, data were analyzed by two-tailed, unpaired Student's t test. For assays involving flies, one-way analysis of variance was performed for comparison between the control and formulation-fed samples. Pooled data are expressed as mean ± S.E. of means of the different replicates of the experiment.

RESULTS

Global Suppression of O-Linked Glycosylation Reduces the Aggregation Propensity and Cytotoxicity of Mutant Huntingtin in a Cellular Model

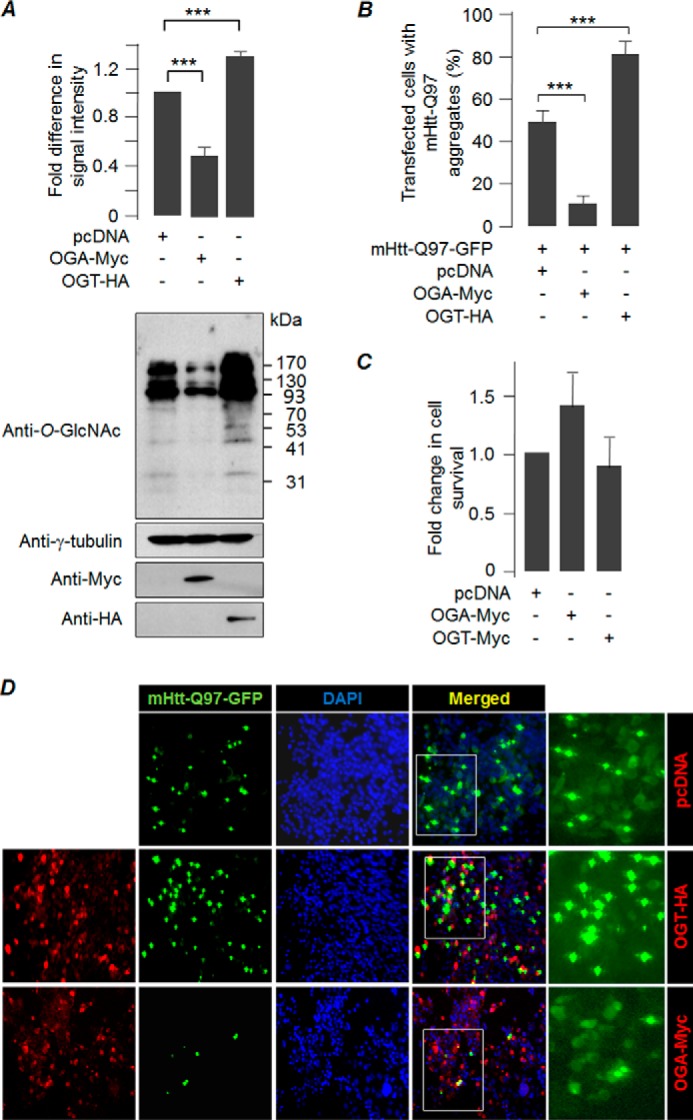

Based on previous findings (21, 22), we were interested in exploring the role of O-GlcNAcylation in suppressing the cytotoxicity caused by aggregate-prone proteins. For this, we used a mammalian expression construct that codes for the OGT or OGA, the two proteins that work antagonistically to regulate the O-linked protein glycosylation. Transient expression of OGT in the murine neuroblastoma cell line Neuro2A resulted in increased global O-GlcNAcylation, although overexpression of OGA led to a reduction in global O-GlcNAcylation (Fig. 1A). To check if O-GlcNAcylation could alter the aggregate-forming propensity of mutant huntingtin, we co-expressed OGA or OGT with an expression construct coding for the amino-terminal huntingtin protein having 97 polyglutamine repeats tagged with green fluorescence protein (mHtt-Q97-GFP) in Neuro2A. Cells that expressed only the mHtt-Q97-GFP served as control (co-transfected with the empty vector pcDNA). As shown in Fig. 1, B and D, co-expression of OGA resulted in a significant reduction in the number of transfected cells showing the mHtt-Q97-GFP-positive aggregates as compared with the control cells that were co-transfected with the empty vector, pcDNA. Conversely, OGT co-expression resulted in a higher proportion of cells with the mHtt-Q97-GFP aggregates (Fig. 1, B and D). Co-expression of OGA or OGT did not affect the transfection efficiency of the mHtt-Q97-GFP coding construct (see the insets, Fig. 1D). Similarly, there was no significant difference in cell survival when OGA or OGT was expressed alone as compared with cells that were transfected with an empty vector (Fig. 1C). To test further whether the reduction in the global O-GlcNAcylation helps the cell to reduce the aggregation of mHtt-Q97-GFP, we evaluated the total and SDS-insoluble forms of mHtt-Q97-GFP by immunoblot and the filter trap assay, respectively (Fig. 2A). Consistent with our observations on mHtt aggregates in situ, co-expression of OGA led to a significant reduction in the level of SDS-insoluble forms of mHtt-Q97-GFP when compared with that in cells co-expressing OGT or only the mHtt-Q97-GFP (pcDNA control; Fig. 2A). Co-expression of OGA or OGT did not show significant change in the total level of mHtt-Q97-GFP in the immunoblots (Fig. 2A). We also found that co-expression of OGA, but not of OGT, resulted in a significant reduction in mHtt-Q97-GFP-mediated cell death, as measured by the MTT assay (Fig. 2B), and also by scoring apoptotic nuclei (Fig. 2D). To check whether the protective effect of OGA was limited to mtHtt-Q97-GFP or whether OGA can ameliorate the toxicity of other disease-associated cytotoxic proteins, we expressed Parkinson disease-associated α-synuclein mutant A30P protein (26) either alone or along with OGA or OGT and measured the cell viability by MTT assays as well as by counting the apoptotic nuclei. As shown in Fig. 2, C and E, OGA, but not OGT, was able to confer protection against the toxicity of the A30P mutant, suggesting that the OGA-mediated protective response could be a generic effect of O-GlcNAcylation and is not specific to mtHtt-Q97-GFP. Taken together, our results suggest a causal role for O-GlcNAcylation in modulating the level of insoluble, aggregated mutant huntingtin and its cytotoxicity.

FIGURE 1.

Suppression of O-GlcNAcylation significantly reduces mHtt-Q97 aggregates. A, Neuro2A cells transfected with an empty vector (pcDNA) or expression construct for OGA-Myc and OGT-HA were evaluated for changes in the global O-glycosylation level by immunoblotting. Expression of OGA and OGT was confirmed by probing with the tag antibodies. Probing with γ-tubulin served as loading control. The bar diagram shown above represent the fold change in the signal intensity of O-glycosylated proteins (normalized to γ-tubulin in the immunoblot) as measured by densitometric analysis (n = 3; ***, p < 0.001). B, bar diagram representing percent transfected cells showing the aggregation of mHtt-Q97-GFP when expressed alone (pcDNA) or with an expression construct coding for OGA-Myc or OGT-HA, as indicated. Note the significant reduction in the transfected cells positive for mHtt-Q97-GFP aggregates when OGA was co-expressed but a significant increase in their frequency when OGT was co-expressed (n = 3; ***, p < 0.001). C, bar diagram showing fold change in survival of cells transiently expressing OGA or OGT as compared with cells transfected with an empty vector (pcDNA), as measured by MTT assay (n = 3). D, representative fluorescence microscopic images (first 4 columns with a ×10 objective) showing aggregation patterns of mHtt-Q97-GFP in Neuro2A cells when expressed alone (pcDNA) and when co-expressed with OGA-Myc or OGT-HA. The intense green signals in the mHtt-Q97-GFP column represent mHtt-Q97 aggregates. The red signal reveals the expression of OGA-Myc or OGT-HA. Nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). Areas boxed in the merged column are enlarged in the last column to more clearly show the GFP-positives cells with or without aggregates.

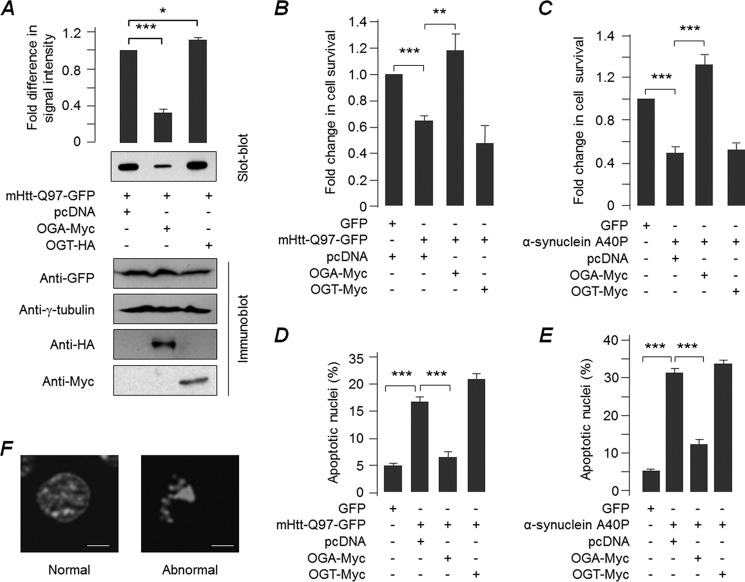

FIGURE 2.

O-GlcNAcylation inhibition reduces mHtt-Q97-mediated cytotoxicity. A, Western blot images of the insoluble, aggregated form of mHtt-Q97-GFP in filter trap assay using a slot-blot apparatus (top) or its total form resolved by immunoblotting (bottom) when expressed with either pcDNA (empty vector control), OGT, or OGA, as indicated in the middle. Expression of OGT and OGA was established by probing them with anti-HA and anti-Myc antibodies, respectively. The bar diagram above shows the fold changes in signal intensities, based on densitometric analysis of the SDS-insoluble and -aggregated form of mHtt-Q97-GFP (normalized to total level detected in the immunoblot; n = 3; ***, p < 0.001; *, p < 0.1). B and C, bar diagrams representing the fold change in the viability of cells expressing mHtt-Q97-GFP (B) or the α-synuclein mutant A40P (C) as measured by an MTT assay. Cells transfected with the indicated constructs were processed for the measurement, and in each set the value obtained for the GFP-transfected cells was considered as 1, and the relative values obtained for indicated combinations were plotted. D and E, bar diagram showing the percentage of cells expressing mHtt-Q97-GFP (D) or the α-synuclein mutant A40P (E) with abnormal (apoptotic) nuclei (as shown in F) as compared with cells that expressed GFP (control) when co-transfected with OGA or OGT coding constructs (in B–E, n = 3; **, p < 0.05; ***, p < 0.005 on Student's t test). F, representative images showing a normal (left) and an abnormal (apoptotic; right) nuclei as judged by DAPI staining (scale, 5 μm).

Inhibition of O-GlcNAcylation Enhances Autophagy

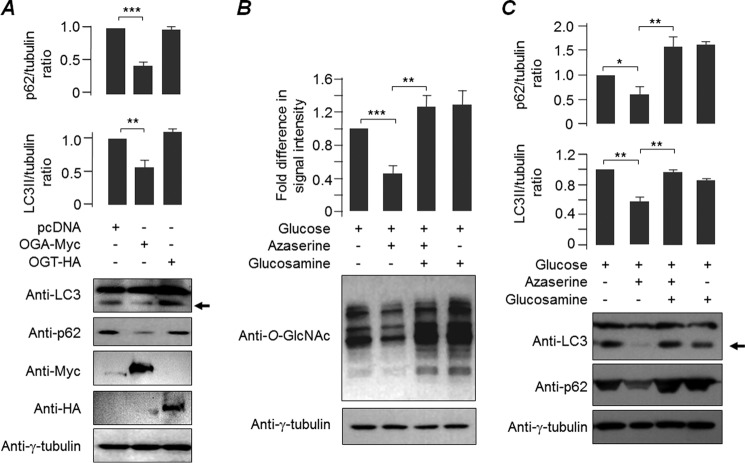

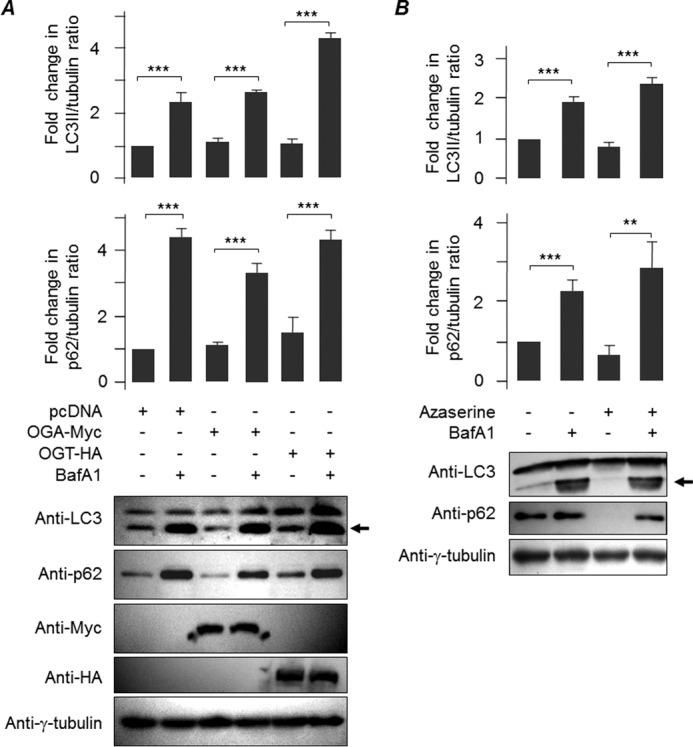

Our next aim was to identify the mechanism by which suppression of O-GlcNAcylation reduces the level of the cytotoxic and insoluble form of mHtt-Q97-GFP. Because the autophagic process is known to clear the aggregated proteins (30, 31), we were interested in testing the impact of O-GlcNAcylation in the basal autophagic process. For this, Neuro2a cells were transfected with the expression construct coding for OGT or OGA or with an empty vector (pcDNA control). At 36 h post-transfection, the cells were harvested, and the levels of two autophagic marker proteins, LC3 and p62, were evaluated. As shown in Fig. 3A, transient overexpression of OGA led to a reduction in the level of both p62 and LC3II, suggesting that suppression of O-GlcNAcylation resulted in an enhanced autophagic flux. To further confirm that the observed effect is indeed because of the changes in global O-GlcNAcylation, we examined the autophagic process after treating the cells with azaserine, which inhibits glutamine fructose-6-phosphate amidotransferase, one of the key enzymes of the hexosamine biosynthesis pathway and thereby inhibits O-GlcNAcylation (32, 33). As shown in Fig. 3B, treatment of Neuro2A cells with azaserine for 12 h resulted in a significant reduction in global O-GlcNAcylation levels. As was observed for OGA expression, azaserine also led to a reduction in the level of the autophagic markers LC3II and p62 (Fig. 3C), confirming that a reduction in the cellular O-GlcNAcylation level correlates with increased levels of basal autophagic flux. To further confirm that the observed effect of azaserine on the autophagic process is indeed through O-GlcNAcylation process, we treated cells both with azaserine and glucosamine and looked at the level of LC3II and p62. Glucosamine is known to rescue the effect of azaserine on the O-GlcNAcylation process; hence, the double treatment should rescue the effect of azaserine on the autophagic process (Fig. 3B). As shown in Fig. 3C, azaserine-glucosamine treatment increased the level of LC3II and p62 as compared with only azaserine treatment, confirming that the level of autophagic induction inversely correlates with the O-GlcNAcylation level.

FIGURE 3.

O-GlcNAcylation modulates autophagy. A, immunoblots (bottom panel) of Neuro2A cells, transiently expressing pcDNA empty vector alone or OGA-Myc or OGT-HA for 36 h, to show levels of the autophagic markers LC3II and p62. Probing with anti-γ-tubulin served as loading control. Note the change in the level of LC3II band (identified by an arrow) in cells that expressed OGA. Co-expression of OGT did not show such an effect. Bar diagrams above show the fold changes in signal intensities of the LC3II and p62 (both normalized to γ-tubulin signal) bands when compared with the control (pcDNA transfected cells). B, Neuro2A cells were grown in a medium with or without azaserine and/or glucosamine for 12 h as indicated, and the changes in the global glycosylation level were evaluated. The bar diagrams above show the fold changes in the glycosylation levels compared with cells that were fed with glucose. C, samples shown in B were tested for the level of autophagy markers LC3 and p62 as indicated. Note the reduction in the intensity of the band for LC3II (identified by an arrow) and p62 in the azaserine-treated cells and their restoration in the azaserine/glucosamine double-treated cells. Bar diagrams above represent the fold changes in the signal intensities for LC3II and p62 (both normalized to γ-tubulin signal) bands compared with the control (glucose-fed cells) (in A–C, n = 3; *, p < 0.5; **, p < 0.05; ***, p < 0.005 on Student's t test).

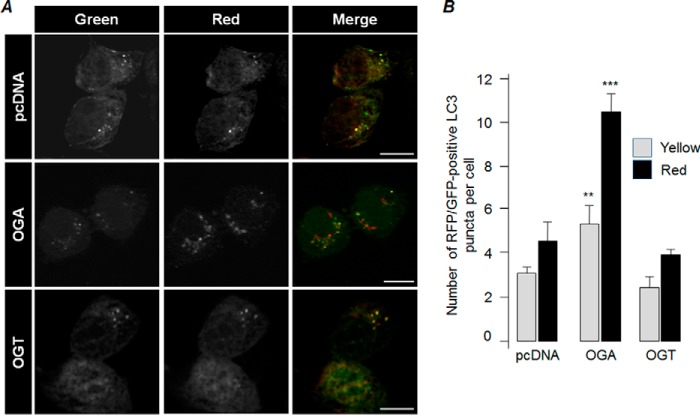

Our next aim was to identify the key step through which the O-GlcNAcylation regulates the autophagic process. The reduction in the level of the autophagy marker LC3II upon depletion of glycosylation may be because the autophagosome formation is inhibited (inhibition of autophagy initiation) or due to the enhanced degradation of LC3II (increased autophagic flux) via lysosome because LC3 itself is an autophagy substrate (34). Our observation that the cellular level of another autophagic substrate, p62, was also at lower levels upon OGA overexpression suggests that the second possibility is more likely. Therefore, we checked whether inhibition of fusion of the autophagosome with the lysosome would rescue the level of LC3II and p62. For this, the cells were transfected with the expression construct coding for OGA or OGT and then were treated with bafilomycin A1 (BafA1), an inhibitor of autophagosome lysosome fusion (34), for 12 h, and then the cellular levels of LC3II and p62 were evaluated. As shown in Fig. 4A, we found that the BafA1-mediated inhibition of the autophagosome-lysosome fusion led to an increase in the level of both LC3II and p62 even in those cells that overexpressed OGA or OGT. Very similar observations were made when the glycosylation was inhibited by azaserine treatment (Fig. 4B). To further confirm that suppression of O-GlcNAcylation indeed increases the autophagy flux, we utilized the tandem mRFP-GFP-LC3 expression construct whose expression product is known to show differences in pH sensitivity and has been widely used to monitor the autophagic process (35). For this, the Neuro2A cells were transiently transfected with the mRFP-GFP-LC3 tandem construct and empty vector (pcDNA), or along with the expression vector coding for OGA or OGT, and scored the co-localization of green and red signals in the cytoplasmic LC3-positive puncta and also the number of green and red puncta. Here, autophagosomes are visible as yellow puncta and autophagolysosomes (post-lysosomal fusion) as red puncta (35). As shown in Fig. 5, co-expression of OGA led to a significant increase in the fraction of red/green-positive LC3 puncta, although no such difference was noted for OGT. Similarly, there was a significant increase in the LC3 puncta that were positive only for red fluorescence (Fig. 5), suggesting that suppression of O-GlcNAcylation did enhance the autophagy flux.

FIGURE 4.

Suppression of O-GlcNAcylation increases autophagy flux. A, Neuro2A cells at 24 h post-transient transfection with an empty vector (pcDNA) or with a construct coding for OGA or OGT were either left untreated or treated with BafA1 for 12 h as indicated, and the levels of autophagy markers LC3 and p62 were evaluated by immunoblotting. Note the increase in the signal intensities of LC3II (arrow) and p62 in all samples treated with BafA1. The blot was probed with anti-Myc and anti-HA antibodies to show the expression of OGA and OGT, respectively; probing with anti-γ-tubulin served as the loading control. B, immunoblot to show levels of LC3II (arrow) and p62 in Neuro2A cells, as in A, untreated or treated with azaserine, alone or in combination with BafA1 as indicated; γ-Tubulin served as the loading control. Bar diagrams above represent the fold changes in the signal intensities for LC3II and p62 (both normalized to γ-tubulin signal) bands compared with the control (n = 3; **, p < 0.05; ***, p < 0.005 on Student's t test).

FIGURE 5.

Suppression of O-GlcNAcylation increases autophagy flux. A, representative images of cells showing LC3-positive puncta in cells that were transiently transfected with mRFP-GFP-LC3 expression construct along with an empty vector (pcDNA) or an expression construct coding for OGA or OGT as indicated. Puncta that are positive both for red and green fluorescence represent autophagosomes, although those positive only for red fluorescence represent autolysosomes (bar, 10 μm). B, bar diagram showing the fraction of puncta positive for both RFP and GFP (yellow) or only the RFP (red) in transiently transfected cells co-expressing mRFP-GFP-LC3 and pcDNA or OGA or OGT, as indicated. n = 3; **, p < 0.5; ***, p < 0.05 on Student's t test).

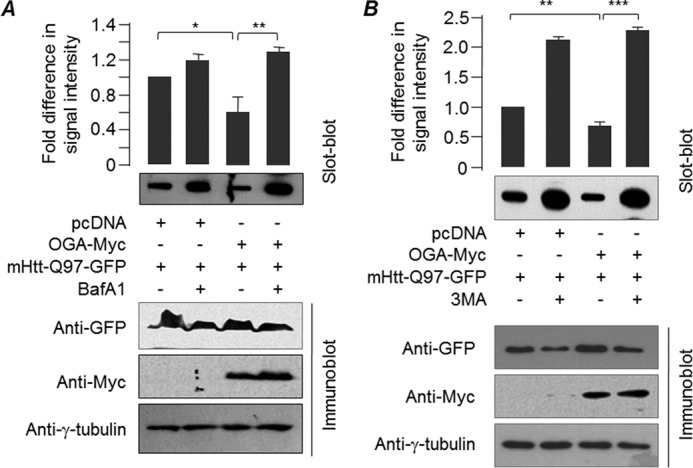

Next, we tested whether the reduction in the level of the insoluble fraction of mutant huntingtin seen in the O-GlcNAcylation-deprived condition is due to an enhanced autophagy flux. As shown in Fig. 6A, BafA1 treatment led to an increase in the level of insoluble fraction of the mutant huntingtin even in the OGA-overexpressing cells, suggesting that decreased O-GlcNAcylation promotes the clearance of the aggregate-prone protein by enhancing autophagosome-lysosome fusion. Finally, to demonstrate that autophagy is the mechanism through which O-GlcNAcase is able to protect cells from huntingtin aggregates, we treated cells that co-express mtHtt-Q97-GFP and OGA with an autophagy inhibitor, 3-MA. As shown in Fig. 6B, 3-MA treatment led to a significant increase in the insoluble form of mtHtt-Q97-GFP even when OGA was co-expressed, suggesting that the protective effect conferred by OGA is indeed through the autophagic process.

FIGURE 6.

Suppression of O-GlcNAcylation increases autophagy flux. Western blots showing changes in the levels of insoluble, aggregated form of mHtt-Q97-GFP (filter trap assay; top) or its total form (immunoblotting; bottom) when expressed with OGA and treated or not treated with BafA1 (A) or 3-MA (B) as indicated. The bar diagrams, shown above, represent fold changes in the signal intensity of the SDS-insoluble, aggregated form of mHtt-Q97-GFP (normalized to total level detected in the immunoblot) as measured by densitometric analysis (n = 3; *, p < 0.1; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001).

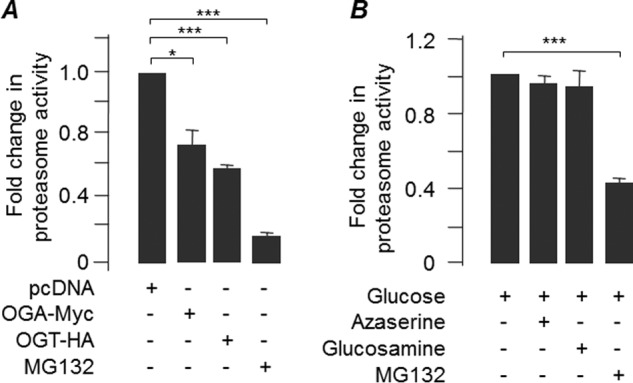

Having shown an indirect correlation between O-GlcNAcylation and autophagic flux, we checked the possible effect of O-GlcNAcylation on proteasomal activity. For this, the cells that transiently expressed OGA or OGT or that were treated with azaserine or glucosamine were assayed for proteasomal activity. As shown in Fig. 7A, transient overexpression of OGT or OGA led to a significant reduction in the proteasomal activity. Treatment of cells with azaserine or glucosamine did not significantly alter the activity (Fig. 7B), suggesting that the O-GlcNAcylation-dependent clearance of mutant huntingtin observed in our model could be primarily through the autophagic process.

FIGURE 7.

Effect of O-GlcNAcylation on proteasomal activity. Bar diagram showing fold change in the proteasomal activity in cells transiently transfected with a construct coding for OGA, OGT, or an empty vector (pcDNA) (A) or with the drug azaserine or glucosamine (B) in the presence or absence proteasomal blocker MG132, as indicated (n = 3; *, p < 0.5; ***, p < 0.05 on Student's t test).

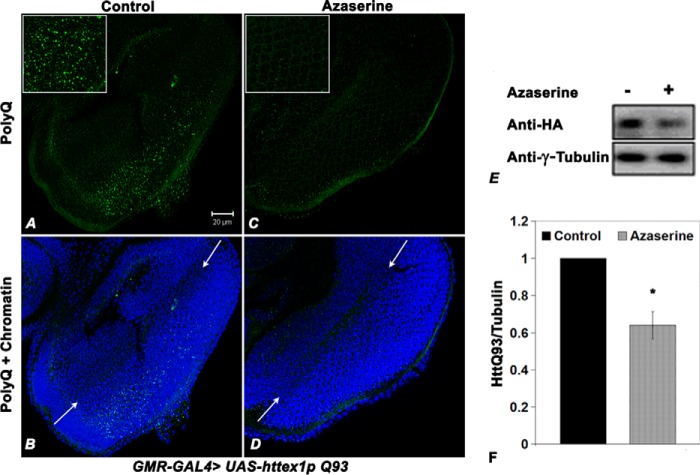

Azaserine Feeding Reduces Mutant Huntingtin Aggregation in the Larval Eye Discs of Drosophila

Having found that azaserine treatment reduces the aggregates of mutant huntingtin in the mammalian cell line, we next tested whether a similar effect could also be seen in vivo, for which we used the fly model of Huntington disease (23). We reared wild-type and GMR-GAL4 > httex1p Q93 larvae from the first instar stage onward on food supplemented with azaserine (250 μg/ml). It is known (36, 37) that GMR-GAL4-driven expression of the mutant huntingtin protein leads to accumulation of polyQ inclusion bodies posterior to the morphogenetic furrow in late third instar larval eye discs (Fig. 8, A and B). We found that azaserine feeding substantially reduced the accumulation of mHtt protein, so in ∼57% of the eye discs (n = 30) from azaserine-fed larvae, the aggregates were nearly absent behind the morphogenetic furrow (Fig. 8, C and D), although in the remaining discs immunostaining was less than that in the eye discs (n = 29) from larvae reared on regular diet (Fig. 6, A and B). Western blotting for detection of polyQ protein levels in the heads of 1-day-old GMR-GAL4 > httex1p Q93 flies further confirmed that azaserine feeding reduced the level of polyQ protein (Fig. 8, E and F).

FIGURE 8.

Azaserine feeding reduces accumulation of mutant Huntingtin protein in fly model. A–D, confocal projection images (projections of four consecutive optical sections which show the morphogenetic furrow) of eye imaginal discs of late third instar GMR-GAL4 > UAS-httex1p Q93 Drosophila larvae, reared from the first instar stage onward to normal (A and B) or azaserine-supplemented food (C and D), immunostained for HA-tagged mutant Htt (green, A–D, identified as “PolyQ”); nuclei are counterstained with DAPI (blue, B and D). The insets in A and C are higher magnification images of a part of the eye discs in A and C, respectively, to more clearly show the polyQ aggregates, which are very abundant in A but nearly absent in C. Arrows in B and D indicate position of the morphogenetic furrow. Scale bar in A represents 20 μm and applies to A–D. E, immunoblot of total proteins from heads of 1-day-old GMR-GAL4/UAS-htt-ex1p Q93 flies, reared on normal (−) or azaserine-supplemented (+) food because the first instar stage, probed with anti-HA antibody, was used to detect Htt-Q93 protein. F, histograms show mean relative levels of HA-tagged polyQ protein (mean ratios of Htt-Q93 and γ-tubulin densities) determined from triplicate immunoblots as in E; the mean ratio of HttQ93 and γ-tubulin densities in Aza-food was taken as 1. (*, p < 0.001.)

Azaserine Feeding Partially Restores the Rhabdomere Morphology and Suppresses the Progressive Loss of Vision in GMR-GAL4 > UAS-httex1p Q93-expressing Flies

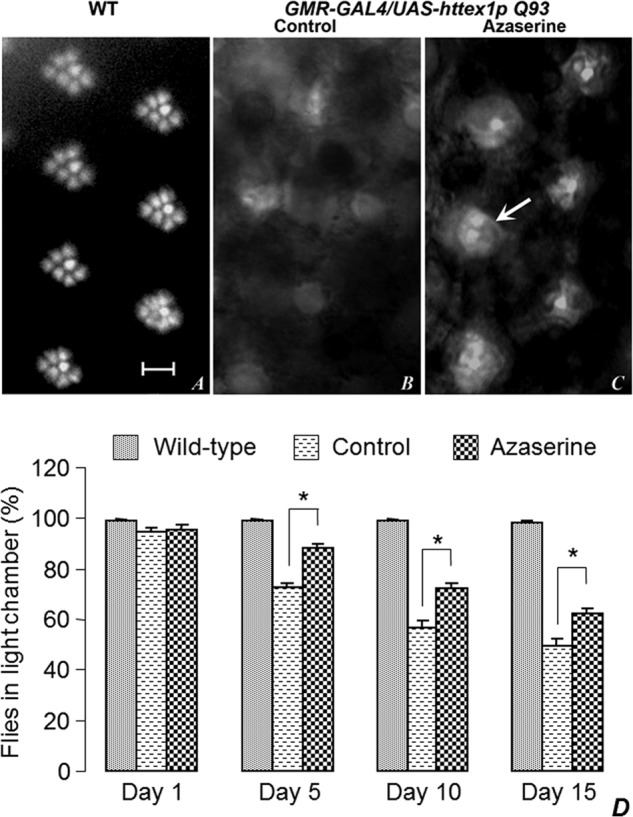

The external eye morphology and vision of freshly eclosed GMR-GAL4 > UAS-httex1p Q93 flies are near normal. However, these flies show a progressive age-dependent degeneration, becoming almost completely blind by 10 days (36–38). As known from earlier studies (36–38), the eye surface of GMR-GAL4 > UAS-httex1p Q93 flies did not show any appreciable change with age in any of the feeding regimes (data not shown). However, as also reported earlier (36, 38), the pseudopupil images of rhabdomeres of 1-day-old GMR-GAL4 > UAS-httex1p Q93-expressing flies fed on a normal diet showed severely degenerated rhabdomeres so that, unlike the stereotyped pattern of rhabdomeres in pseudopupil image of eyes of wild-type flies (Fig. 9A), no distinct rhabdomeres were seen in their eyes (Fig. 8B). Interestingly, GMR-GAL4 > UAS-httex1p Q93 flies reared on the azaserine-supplemented food displayed at least some organized rhabdomere-like structures in ∼60% flies (Fig. 8C).

FIGURE 9.

Azaserine feeding suppresses mHttQ93-induced neurodegeneration in adult Drosophila eyes and reduces the age-dependent loss of vision. A, pseudopupil images of eyes of 1-day-old wild type, or GMR-GAL4 > UAS-httex1p Q93 flies grown on control (B), or on azaserine-containing food (C). Arrow in C indicates the presence of two distinct rhabdomeres in one of the ommatidial units; these are not seen in any ommatidial unit in control flies. Scale bar in A indicates 20 μm and applies to A–C. D, histograms showing phototaxis (percent flies moving to illuminated chamber, y axis) of wild type and GMR-GAL4 > UAS-httex1p Q93 flies reared on control or azaserine-supplemented food on different days (x axis) after emergence. Each value in the bar diagram is the mean of 20 replicates with 10 flies in each set. The * in bar diagrams indicates the p value to be <0.05 when comparing the mean phototaxis of GMR-GAL4 > UAS-httex1p Q93 flies reared on control (Cont) and azaserine (Aza)-supplemented food, respectively, on days 5, 10, and 15.

Expression of UAS httex1p Q93 in eye cells with the GMR-GAL4 driver causes progressive neuronal degeneration of the photoreceptor neurons so that the flies lose their vision as they age (36, 38). To examine whether the azaserine-mediated restoration of the rhabdomeric organization improved the vision of flies, we tested the functionality of vision in 5-, 10-, and 15-day-old flies (wild type and GMR-GAL4 > httex1p Q93) by the phototaxis behavioral assay, which examines the choice of flies to move between illuminated and dark chambers. Although nearly all wild-type flies of different ages moved to the illuminated chamber (positive phototaxis), the GMR-GAL4 > httex1p Q93 flies reared on normal food progressively lost their vision so that the proportion of flies selecting the lighted chamber declined with age (Fig. 9D). By day 10, these flies became nearly blind because they moved randomly between the dark and light chambers (Fig. 9D). Significantly, a greater proportion of GAL4 > httex1p Q93 flies reared on azaserine-supplemented food continued to move to the illuminated chamber even on day 15 (Fig. 9D). Thus, azaserine feeding partially restored the vision in GAL4 > httex1p Q93 flies so that the proportion of flies selecting the illuminated chamber was significantly higher on each day of phototaxis assay than in those grown on normal food (Fig. 9D).

DISCUSSION

Dynamic modification of Ser/Thr residues of proteins by O-linked N-acetylglucosamine (O-GlcNAc) is an important post-translational modification for cellular signaling (1, 3, 39). More than 500 proteins involved in diverse cellular functions, including the transcription, translation, metabolism, and stress response, have been identified to undergo this modification (1, 3, 39). It is significant that about 270 of these proteins are known in the brain tissue alone (40). Therefore, it is not surprising that aberrant O-GlcNAcylation is associated with various disorders, including the neurodegenerative disorders (3–11).

A common pathological feature of many neurodegenerative diseases, including Alzheimer, Parkinson, and Huntington diseases, is the accumulation/aggregation of one or more proteins in different regions of the brain, which is believed to underlie neurodegeneration (12, 37, 41). These proteotoxic aggregates are cleared by coordinated action of the cellular proteolysis system (ubiquitin-proteasome system and autophagy-lysosomal pathways) and molecular chaperones (12, 30). Although the regulation of UPS by O-GlcNAcylation is fairly well understood, there are contrasting reports about a protective role of O-GlcNAcylation in neurodegeneration. For example, it is shown that although O-GlcNAcylation of ubiquitin-activating enzyme E1 promotes ubiquitination (42) and is thus expected to enhance protein degradation, the same modification in the Rpt2 ATPase subunit of the proteasome inhibits its ATPase activity and suppresses proteasome function (43), which would lead to the accumulation of ubiquitinated proteins. Interestingly, it is shown that elevated O-GlcNAcylation in brain inhibits proteasome function and promotes neuronal apoptosis (44). We find that overexpression of either OGT or OGA led to significant reduction in the proteasome activity in our cellular model, and this corroborates well with a recent report on proteasomal function in Caenorhabditis elegans mutants for OGT or OGA (45). However, we did not find any difference in the proteasome activity when the cells were treated with azaserine or glucosamine for the duration and concentration used, suggesting that the level and/or activity of OGT and OGA, rather than flux through the hexosamine biosynthetic pathway alone, is/are more critical in modulating the activity of the proteasome. In view of these observations, and existing reports that accumulation of protein aggregates blocks proteasome function (46, 47), it appears that proteasome alone might not be sufficient to clear these cytotoxic aggregates. This notion is strengthened with the emerging understanding of the role of autophagy in degradation of such aggregates in cell and animal models (12, 27, 48) and that the identification of novel regulators of autophagy that help in the clearance of toxic protein aggregates is important. Considering the established fact that O-GlcNAcylation acts as a nutrient sensor (3, 49) and the role of nutrients (serum amino acid, glucose) in regulation of the autophagic process (50, 51), we hypothesized that changes in the O-GlcNAcylation level might modulate the autophagic process. Interestingly, we found here that inhibition of O-GlcNAcylation, either by overexpressing OGA or by azaserine treatment, decreased the polyQ aggregation by promoting their clearance via autophagy.

In agreement with the results of our in vitro cell culture model, our studies on the in vivo fly model also revealed that azaserine feeding resulted in the improvement in Drosophila eyes expressing mutant huntingtin at the cellular, phenotypic, and functional levels in the form of reduced aggregation of mHtt, improved rhabdomere organization, and improved vision, respectively. Because glucosamine was highly toxic to larvae even at a very low concentration, we could not examine the effects of elevated levels of O-GlcNAcylation on polyQ toxicity in the fly model. The decrease in proteotoxicity on azaserine feeding might involve either the inhibition of toxic protein synthesis or its enhanced clearance through the degradation machinery of the cell. Several recent findings, including our present in vitro findings, suggest a greater role of enhanced clearance of toxic proteins by azaserine. Thus, the reduced polyQ aggregate load seen in azaserine-fed GAL4 > httex1p Q93 larval eye discs and adult heads is likely to be due to their enhanced clearance, which in turn results in partial restoration of eye structure and function.

Azaserine has already been reported to decrease the level of amyloid deposition in pancreatic islets of the mouse model of diabetes (52), which indicates the possibility of improvement in protein clearance machinery, thereby reducing the accumulation of amyloid deposits. Our observations that inhibition O-GlcNAcylation induces the clearance of protein aggregates by enhancing the autophagic process is in agreement with a recent finding that cardiac O-GlcNAcylation regulates autophagic signaling in the rat model of type II diabetes (53). Interestingly, a recent report, which appeared while this manuscript was in preparation, by Wang et al. (45), in the C. elegans model of human neurodegenerative diseases also indicates that the suppression of O-GlcNAcylation decreases neurodegeneration. Taken together, our in vitro and in vivo findings indicate that inhibition of O-GlcNAcylation stimulates autophagy and thereby reduces the load of proteotoxic huntingtin aggregates and provides protection from neurodegeneration.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Lawrence Marsh (University of California at Irvine) for the mHtt-Q97-GFP expression construct; Dr. T. Yoshimori (National Institute for Basic Biology, Okazaki, Japan) for the mRFP-GFP-LC3 construct; Dr. John A. Hannover (National Institutes of Health) and Dr. Gerald W. Hart (Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine) for the expression constructs coding for OGA and OGT, respectively. We also thank the anonymous reviewers for their suggestions and comments that greatly helped to improve the manuscript.

This work was supported in part by a research grant from the Department of Atomic Energy, Government of India (to S. G.).

- OGT

- O-linked N-acetylglycosyltransferase

- mHtt

- polyglutamine expanded huntingtin exon 1 protein fragment

- OGA

- O-linked N-acetylglucosaminidase

- BafA1

- bafilomycin A1

- polyQ

- polyglutamine

- MTT

- 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide

- TRITC

- tetramethylrhodamine isothiocyanate

- 3-MA

- 3-methyladenine.

REFERENCES

- 1. Love D. C., Hanover J. A. (2005) The hexosamine signaling pathway: deciphering the “O-GlcNAc code”. Sci. STKE 2005, re13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Vocadlo D. J. (2012) O-GlcNAc processing enzymes: catalytic mechanisms, substrate specificity, and enzyme regulation. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 16, 488–497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Butkinaree C., Park K., Hart G. W. (2010) O-Linked β-N-acetylglucosamine (O-GlcNAc): extensive crosstalk with phosphorylation to regulate signaling and transcription in response to nutrients and stress. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1800, 96–106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Chatham J. C., Marchase R. B. (2010) Protein O-GlcNAcylation: a critical regulator of the cellular response to stress. Curr. Signal. Transduct. Ther. 5, 49–59 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bond M. R., Hanover J. A. (2013) O-GlcNAc cycling: a link between metabolism and chronic disease. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 33, 205–229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Okuyama R., Marshall S. (2003) UDP-N-acetylglucosaminyl transferase (OGT) in brain tissue: temperature sensitivity and subcellular distribution of cytosolic and nuclear enzyme. J. Neurochem. 86, 1271–1280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Griffith L. S., Schmitz B. (1995) O-Linked N-acetylglucosamine is upregulated in Alzheimer brains. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 213, 424–431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Arnold C. S., Johnson G. V., Cole R. N., Dong D. L., Lee M., Hart G. W. (1996) The microtubule-associated protein Tau is extensively modified with O-linked N-acetylglucosamine. J. Biol. Chem. 271, 28741–28744 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cole R. N., Hart G. W. (1999) Glycosylation sites flank phosphorylation sites on synapsin I: O-linked N-acetylglucosamine residues are localized within domains mediating synapsin I interactions. J. Neurochem. 73, 418–428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Dong D. L., Xu Z. S., Hart G. W., Cleveland D. W. (1996) Cytoplasmic O-GlcNAc modification of the head domain and the KSP repeat motif of the neurofilament protein neurofilament-H. J. Biol. Chem. 271, 20845–20852 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Liu F., Shi J., Tanimukai H., Gu J., Gu J., Grundke-Iqbal I., Iqbal K., Gong C. X. (2009) Reduced O-GlcNAcylation links lower brain glucose metabolism and tau pathology in Alzheimer's disease. Brain 132, 1820–1832 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Mittal S., Ganesh S. (2010) Protein quality control mechanisms and neurodegenerative disorders: Checks, balances and deadlocks. Neurosci. Res. 68, 159–166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Zheng Z., Diamond M. I. (2012) Huntington disease and the huntingtin protein. Prog. Mol. Biol. Transl. Sci. 107, 189–214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Cattaneo E., Zuccato C., Tartari M. (2005) Normal huntingtin function: an alternative approach to Huntington disease. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 6, 919–930 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ho L. W., Brown R., Maxwell M., Wyttenbach A., Rubinsztein D. C. (2001) Wild type huntingtin reduces the cellular toxicity of mutant Huntingtin in mammalian cell models of Huntington disease. J. Med. Genet. 38, 450–452 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Rozas J. L., Gómez-Sánchez L., Tomás-Zapico C., Lucas J. J., Fernández-Chacón R. (2011) Increased neurotransmitter release at the neuromuscular junction in a mouse model of polyglutamine disease. J. Neurosci. 31, 1106–1113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Shirendeb U., Reddy A. P., Manczak M., Calkins M. J., Mao P., Tagle D. A., Reddy P. H. (2011) Abnormal mitochondrial dynamics, mitochondrial loss and mutant huntingtin oligomers in Huntington disease: implications for selective neuronal damage. Hum. Mol. Genet. 20, 1438–1455 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Nucifora F. C., Jr., Sasaki M., Peters M. F., Huang H., Cooper J. K., Yamada M., Takahashi H., Tsuji S., Troncoso J., Dawson V. L., Dawson T. M., Ross C. A. (2001) Interference by huntingtin and atrophin-1 with cbp-mediated transcription leading to cellular toxicity. Science 291, 2423–2428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ravikumar B., Stewart A., Kita H., Kato K., Duden R., Rubinsztein D. C. (2003) Raised intracellular glucose concentrations reduce aggregation and cell death caused by mutant huntingtin exon 1 by decreasing mTOR phosphorylation and inducing autophagy. Hum. Mol. Genet. 12, 985–994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Puri R., Jain N., Ganesh S. (2011) Increased glucose concentration results in reduced proteasomal activity and the formation of glycogen positive aggresomal structures. FEBS J. 278, 3688–3698 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kaniuk N. A., Kiraly M., Bates H., Vranic M., Volchuk A., Brumell J. H. (2007) Ubiquitinated-protein aggregates form in pancreatic beta-cells during diabetes-induced oxidative stress and are regulated by autophagy. Diabetes 56, 930–939 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Cohen E., Dillin A. (2008) The insulin paradox: aging, proteotoxicity and neurodegeneration. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 9, 759–767 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Steffan J. S., Bodai L., Pallos J., Poelman M., McCampbell A., Apostol B. L., Kazantsev A., Schmidt E., Zhu Y. Z., Greenwald M., Kurokawa R., Housman D. E., Jackson G. R., Marsh J. L., Thompson L. M. (2001) Histone deacetylase inhibitors arrest polyglutamine-dependent neurodegeneration in Drosophila. Nature 413, 739–743 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Freeman M. (1996) Reiterative use of the EGF receptor triggers differentiation of all cell types in the Drosophila eye. Cell 87, 651–660 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Dwivedi V., Anandan E. M., Mony R. S., Muraleedharan T. S., Valiathan M. S., Mutsuddi M., Lakhotia S. C. (2012) In vivo effects of traditional Ayurvedic formulations in Drosophila melanogaster model relate with therapeutic applications. PLoS One 7, e37113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Garyali P., Siwach P., Singh P. K., Puri R., Mittal S., Sengupta S., Parihar R., Ganesh S. (2009) The malin-laforin complex suppresses the cellular toxicity of misfolded proteins by promoting their degradation through the ubiquitin-proteasome system. Hum. Mol. Genet. 18, 688–700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Pampliega O., Orhon I., Patel B., Sridhar S., Díaz-Carretero A., Beau I., Codogno P., Satir B. H., Satir P., Cuervo A. M. (2013) Functional interaction between autophagy and ciliogenesis. Nature 502, 194–200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Juenemann K., Schipper-Krom S., Wiemhoefer A., Kloss A., Sanz Sanz A., Reits E. A. (2013) Expanded polyglutamine-containing N-terminal huntingtin fragments are entirely degraded by mammalian proteasomes. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 27068–27084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Franceschini N., Kirschfeld K. (1971) Pseudopupil phenomena in the compound eye of Drosophila. Kybernetik 9, 159–182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ravikumar B., Sarkar S., Rubinsztein D. C. (2008) Clearance of mutant aggregate-prone proteins by autophagy. Methods Mol. Biol. 445, 195–211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Matsumoto G., Wada K., Okuno M., Kurosawa M., Nukina N. (2011) Serine 403 phosphorylation of p62/SQSTM1 regulates selective autophagic clearance of ubiquitinated proteins. Mol. Cell 44, 279–289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Jensen R. V., Zachara N. E., Nielsen P. H., Kimose H. H., Kristiansen S. B., Bøtker H. E. (2013) Impact of O-GlcNAc on cardioprotection by remote ischaemic preconditioning in non-diabetic and diabetic patients. Cardiovasc. Res. 97, 369–378 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Rajapakse A. G., Ming X. F., Carvas J. M., Yang Z. (2009) The hexosamine biosynthesis inhibitor azaserine prevents endothelial inflammation and dysfunction under hyperglycemic condition through antioxidant effects. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 296, H815–H822 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Mizushima N., Yoshimori T., Levine B. (2010) Methods in mammalian autophagy research. Cell 140, 313–326 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kimura S., Noda T., Yoshimori T. (2007) Dissection of the autophagosome maturation process by a novel reporter protein, tandem fluorescent-tagged LC3. Autophagy 3, 452–460 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Mallik M., Lakhotia S. C. (2009) RNAi for the large non-coding hsrω transcripts suppresses polyglutamine pathogenesis in Drosophila models. RNA Biol. 6, 464–478 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Mallik M., Lakhotia S. C. (2010) Modifiers and mechanisms of multi-system polyglutamine neurodegenerative disorders: lessons from fly models. J. Genet. 89, 497–526 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Jackson G. R., Salecker I., Dong X., Yao X., Arnheim N., Faber P. W., MacDonald M. E., Zipursky S. L. (1998) Polyglutamine-expanded human huntingtin transgenes induce degeneration of Drosophila photoreceptor neurons. Neuron 21, 633–642 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Akimoto Y., Hart G. W., Hirano H., Kawakami H. (2005) O-GlcNAc modification of nucleocytoplasmic proteins and diabetes. Med. Mol. Morphol. 38, 84–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Alfaro J. F., Gong C. X., Monroe M. E., Aldrich J. T., Clauss T. R., Purvine S. O., Wang Z., Camp D. G., 2nd, Shabanowitz J., Stanley P., Hart G. W., Hunt D. F., Yang F., Smith R. D. (2012) Tandem mass spectrometry identifies many mouse brain O-GlcNAcylated proteins including EGF domain-specific O-GlcNAc transferase targets. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 7280–7285 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Jadhav S., Zilka N., Novak M. (2013) Protein truncation as a common denominator of human neurodegenerative foldopathies. Mol. Neurobiol. 48, 516–532 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Guinez C., Mir A. M., Dehennaut V., Cacan R., Harduin-Lepers A., Michalski J. C., Lefebvre T. (2008) Protein ubiquitination is modulated by O-GlcNAc glycosylation. FASEB J. 22, 2901–2911 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Zhang F., Su K., Yang X., Bowe D. B., Paterson A. J., Kudlow J. E. (2003) O-GlcNAc modification is an endogenous inhibitor of the proteasome. Cell 115, 715–725 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Liu K., Paterson A. J., Zhang F., McAndrew J., Fukuchi K., Wyss J. M., Peng L., Hu Y., Kudlow J. E. (2004) Accumulation of protein O-GlcNAc modification inhibits proteasomes in the brain and coincides with neuronal apoptosis in brain areas with high O-GlcNAc metabolism. J. Neurochem. 89, 1044–1055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Wang P., Lazarus B. D., Forsythe M. E., Love D. C., Krause M. W., Hanover J. A. (2012) O-GlcNAc cycling mutants modulate proteotoxicity in Caenorhabditis elegans models of human neurodegenerative diseases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 17669–17674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Bence N. F., Sampat R. M., Kopito R. R. (2001) Impairment of the ubiquitin-proteasome system by protein aggregation. Science 292, 1552–1555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Holmberg C. I., Staniszewski K. E., Mensah K. N., Matouschek A., Morimoto R. I. (2004) Inefficient degradation of truncated polyglutamine proteins by the proteasome. EMBO J. 23, 4307–4318 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Williams A., Jahreiss L., Sarkar S., Saiki S., Menzies F. M., Ravikumar B., Rubinsztein D. C. (2006) Aggregate-prone proteins are cleared from the cytosol by autophagy: therapeutic implications. Curr. Top. Dev. Biol. 76, 89–101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Wells L., Vosseller K., Hart G. W. (2003) A role for N-acetylglucosamine as a nutrient sensor and mediator of insulin resistance. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 60, 222–228 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Mizushima N. (2007) Autophagy: process and function. Genes Dev. 21, 2861–2873 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Chang Y. Y., Juhász G., Goraksha-Hicks P., Arsham A. M., Mallin D. R., Muller L. K., Neufeld T. P. (2009) Nutrient-dependent regulation of autophagy through the target of rapamycin pathway. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 37, 232–236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Hull R. L., Zraika S., Udayasankar J., Kisilevsky R., Szarek W. A., Wight T. N., Kahn S. E. (2007) Inhibition of glycosaminoglycan synthesis and protein glycosylation with WAS-406 and azaserine result in reduced islet amyloid formation in vitro. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 293, C1586–C1593 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Marsh S. A., Powell P. C., Dell'italia L. J., Chatham J. C. (2013) Cardiac O-GlcNAcylation blunts autophagic signaling in the diabetic heart. Life Sci. 92, 648–656 1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]