Abstract

Population aging is unprecedented, without parallel in human history, and the 21st century will witness even more rapid aging than did the century just past. Improvements in public health and medicine are having a profound effect on population demographics worldwide. By 2017, there will be more people over the age of 65 than under age 5, and by 2050, two billion of the estimated nine billion people on Earth will be older than 60 (http://unfpa.org/ageingreport/). Although we can reasonably expect to live longer today than past generations did, the age-related disease burden we will have to confront has not changed. With the proportion of older people among the global population being now higher than at any time in history and still expanding, maintaining health into old age (or healthspan) has become a new and urgent frontier for modern medicine. Geroscience is a cross-disciplinary field focused on understanding the relationships between the processes of aging and age-related chronic diseases. On October 30–31, 2013, the trans-National Institutes of Health GeroScience Interest Group hosted a Summit to promote collaborations between the aging and chronic disease research communities with the goal of developing innovative strategies to improve healthspan and reduce the burden of chronic disease.

Key Words: Chronic disease, Geroscience.

Dr. Francis Collins (National Institutes of Health) opened the Summit noting that the new field of geroscience reflects two fundamental concepts related to health and disease that have been evolving over the past decade. First, although traditional research efforts focus on specific diseases in isolation (whether cancer, cardiovascular disease, or Alzheimer’s), it is equally important to understand the complex interactions between underlying processes of aging and susceptibility to chronic disease. Second, he noted the need to balance efforts to reduce the effects of chronic disease by also focusing on research to promote healthy aging to improve the health of the world’s aging population. Following Dr. Collins’ address were three keynote talks. Dr. Chris Murray (University of Washington) introduced the Global Burden of Disease 2010 study, a systematic scientific effort by 488 investigators from 303 institutions and 50 countries to quantify the comparative magnitude of health loss for 187 countries from 1990 to 2010. Although death rates vary markedly by country, the prevalence of chronic disabilities is uniformly high with much less variation across countries. Currently, many countries are using the results of the Global Burden of Disease 2010 study to direct social policy programs to accommodate the aging population. Looking toward the future, Dr. Murray projected that follow-up studies will be used to forecasts disease burden by country for the next 15–25 years. Dr. Brian Kennedy (Buck Institute) presented an overview of research findings across divergent experimental models indicating that life expectancy is plastic and that prolongation of life span, using methods such as caloric restriction or treatment with rapamycin, is accompanied by concomitant resistance to onset or severity of chronic disease. The molecular mechanisms of aging can be largely grouped into three overlapping categories, accumulation of damage (to DNA, proteins, and organelles), a reduced ability to repair damage, and antagonistic pleiotropy (in which events that increase fitness at early age exact a toll among the elderly people). In contrast, mechanisms that extend life span are more complex, although multiple studies indicate that reduced insulin and/or insulin-like growth factor signaling, reduced target-of-rapamycin signaling, and mutations that affect the sirtuin pathway extend life span. It is not yet known whether resources that are directed toward growth and reproduction cause early aging or whether they activate stress resistance and repair pathways to promote prolonged life span. Dr. Linda Fried (Columbia University) discussed the interplay between physical frailty and chronic disease in the elderly people. Frailty syndrome is characterized by diminished strength, endurance, and physiologic function. The prevalence of frailty increases with age and is associated with a wide range of chronic diseases. At the molecular level, the emergence of frailty is associated with the impaired ability to respond to a variety of stressors and these impairments could predispose to end organ disease. Frailty and multiple chronic diseases share common risk factors such as low physical activity, loss of muscle mass, smoking, and insufficient nutrition suggesting the existence of cross talk between frailty and diverse disease pathways. Considering that frailty is an emergent property of a dysregulated complex adaptive system, the available data suggest that single target interventions may not be fully effective unless they interface across other interconnected pathways.

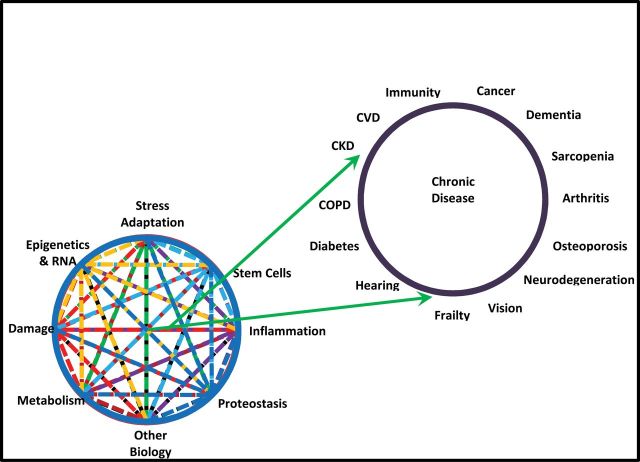

Following the keynote presentations were seven scientific sessions, each focused on a specific mechanism that intersects aging and chronic disease pathways: inflammation, adaptation to stress, epigenetics, metabolism, macromolecular damage, proteostasis, and stem cells and regeneration (Figure 1). Each session was defined by five critical questions for the field. After an introductory overview of the session, five short, concept-driven talks were presented to address each question. The principal goal for the presenters was to identify novel convergences between the mechanisms associated with aging biology and the etiologies of chronic disease and to generate a new vision of collaborative interactions that will advance our understanding of how the molecular, cellular, and systemic degenerative processes of aging affect the etiologies of chronic disease. The companion Opinion Piece articles of this collection were written by the co-chairs for each session and highlight the state of the science and future areas of discovery.

Figure 1.

Advancing health through geroscience. Seven specific aspects of the biology of aging are shown at the bottom left. These interact with each other and ultimately contribute to the chronic diseases whose prevalence increases with aging in the human population (shown in the upper right). The figure suggests that understanding these (and other) aspects of the biology of aging should lead to treatments and interventions that will lessen the burden of chronic disease. The listed aspects of aging biology and the chronic diseases are representative.

These seven topics are by no means encompass all there is to be learned about geroscience, and the collection of Opinion Piece articles is intended to lead to a better appreciation of the multiple levels at which all of these variables that influence aging interact with each other and promote a more “systems level” understanding of the relationship between aging biology and susceptibility to disease. Such a systems approach might in turn allow the identification of critical features where interventions might be most successful.