Abstract

Background

Community-based participatory research (CBPR) emphasizes collaborative efforts among communities and academics where all members are equitable contributors. Capacity building through training in research methodology is a potentially important outcome for CBPR partnerships.

Objectives

To describe the logistics and lessons learned from building community research capacity for focus group moderation in the context of a CBPR partnership.

Methods

After orientation to CBPR principles, members of a US suburban community underwent twelve hours of interactive learning in focus group moderation by a national focus group expert. An additional eight-hour workshop promoted advanced proficiency and built on identified strengths and weaknesses. Ten focus groups were conducted at an adult education center addressing a health concern previously identified by the center’s largely immigrant and refugee population. Program evaluation was achieved through multiple observations by community and academic-based observers.

Results

Twenty-seven community and academic members were recruited through established relationships for training in focus group moderation, note-taking, and report compilation. Focus group training led to increased trust among community and research partners while empowering individual community members and increasing research capacity for CBPR.

Conclusions

Community members were trained in focus group moderation and successfully applied these skills to a CBPR project addressing a health concern in the community. This approach of equipping community members with skills in a qualitative research method promoted capacity building within a socio-culturally diverse community, while strengthening community-academic partnership. In this setting, capacity building efforts may help to ensure the success and sustainability for continued health interventions through CBPR.

Keywords: Capacity building, community-based participatory research, focus groups, immigrant or ethnic populations, qualitative research

Introduction

Community members from various racial and ethnic groups frequently encounter cultural and structural barriers to optimal health and health care, within the U.S. and internationally. These challenges are typically intensified by the separation between academic health institutions and their surrounding communities1,2. Academic organizations often distance themselves as 'ivory towers,' seeking only data rather than relationships from study participants. Communities’ distrust of academic researchers coupled with socio-cultural differences only perpetuates these barriers1–3.

In recent years, research approaches have increasingly included participatory techniques in an attempt to address socio-cultural obstacles to health. Community-based participatory research (CBPR) offers a means of collaboratively investigating health topics within the context of community1,3–5. CBPR embodies a reciprocal relationship; and ideally, community members act as dual contributors and benefactors throughout the research process. In this way, CBPR promotes sustainable change and can address capacity needs within communities5. More specifically, communities benefit from capacity building of its members in areas such as leadership skills, communication abilities and personal skill sets2,3,6,7. Strengthening organizational development is also essential and can be accomplished through community collaborations, balanced allocation of responsibilities and funding, and intra-community channels of communication6–8.

A barrier to the CBPR approach is that community research capacity is often quite limited, thereby prohibiting community members from full involvement in the research process9,10. Acquisition of research skills enables community participants to apply their new skills and knowledge to other projects and may facilitate subsequent training of others within their communities11–13. Ultimately, capacity building through CBPR is a means of empowering the community; when applied to health issues, it provides a community with the skills and expertise to address and manage such concerns in a sustainable manner.

One research skill that may build community research capacity is focus group moderation. Focus groups are a common means of engaging health topics within diverse populations in CBPR partnerships14. This qualitative research method allows in-depth study of complex topics not amenable to quantitative methods14,15. Led by a skilled moderator, focus groups involve a joint discussion among a small group of individuals in a relaxed environment16–18. Particular insight into personal experience, attitudes and beliefs is gleaned from participants’ interactions with each other16,19,20. Focus groups may additionally delve into socially sensitive topics including those associated with shame or stigmatization21. Finally, since focus groups encourage a non-threatening atmosphere, they can be particularly instrumental in addressing health topics among diverse ethnic groups, including those with low health literacy22–24.

Although CBPR studies frequently imply capacity building, it is typically described as a byproduct and rarely as an initial objective of the partnership5. Moreover, minimal discussion exists on the logistics of how to build capacity. The goal of this project was to foster qualitative research capacity within the context of an established CBPR partnership while investigating specific health needs of a community. In this manuscript, we use a case study format to describe the logistics and lessons learned from building community research capacity through focus group training.

Intervention

Setting

Hawthorne Education Center (HEC) is a constituent of the Rochester Public School District in Rochester, Minnesota, USA. HEC provides education with an emphasis on literacy to Rochester adults. Over time, HEC has evolved into a community center, providing instruction for cultural adjustment, citizenship and even driver’s license training. The Hawthorne community includes approximately 2,500 learners, 60 staff members, and 250 volunteers each year. Adult learners come predominantly from Sub-Saharan Africa (38%), Latin America (21%), Southeast Asia (17%), and Southeast Minnesota (20%); they speak 70 different languages at home. An estimated 85% live at or below the federal poverty level. Less than half (40%) have completed high school; 12% have never before attended school.

Partnership

The Rochester Health Community Partnership (RHCP) initially arose out of the health needs of the HEC community. In 2004, the HEC program manager (JAN) approached Mayo Clinic faculty who volunteered at HEC to work together to address the problem of tuberculosis (TB) among its learners. Both community and academic partners agreed to adopt a CBPR approach to broadly address health concerns at HEC, and to focus the initial effort on TB. An early partnership consisting of HEC learners, HEC staff, Mayo Clinic faculty and representatives from the local public health department was established to explore CBPR and its potential application to TB at HEC. Recognizing that collaborative solutions require time, commitment, and co-learning, Mayo Clinic staff (IGS, JAW) and partners from the Hawthorne community (JAN and another staff member) attended the 2006 Summer Service Learning Institute, which was sponsored by Community-Campus Partnerships for Health (http://www.ccph.info/). There, they worked together on principles of open communication, compromise and mutual trust to create a solid foundation for this partnership.

Upon return, operating norms were established (e.g., democratic decision making processes, preparation for meetings, communication plans, etc), and CBPR principles were adopted from existing frameworks during monthly meetings. Additionally, a health needs survey at HEC was performed. RHCP has since grown to include five additional community-based organizations, two additional academic centers and many volunteers. RHCP’s mission encompasses promoting health and well-being among the Rochester population through CBPR, education and civic engagement in order to achieve health equity (www.rochesterhealthy.org). While RHCP was conducting several health projects, community research capacity and external funding were primarily built around the TB project with the goal of establishing and applying the CBPR infrastructure to future health topics. The HEC program manager (JAN) was a co-principal investigator on this federal grant which promoted the development of community research capacity development.

In early discussions, it became evident that a community-based qualitative research infrastructure was needed to explore factors that influence health behaviors related to TB prevention and control, especially among the refugee and immigrant population of HEC. Furthermore, the partnership recognized that it would be important to systematically obtain input from the HEC community through focus groups. A variety of options for conducting focus groups were discussed, but ultimately it was agreed that the infrastructure for focus groups work should come directly from the community. Therefore, a team of community-academic members was assembled to learn focus groups techniques and to build a qualitative research infrastructure for the partnership.

Training in focus groups moderation

Through established community relationships, HEC students and staff and non-HEC community and academic members were recruited for training in focus group moderation (Table 1). Recruitment occurred through direct solicitation by the community-academic research team.

Table 1.

Focus group trainee demographics

| No. (%) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Ethnicity | Workshop 1 | Workshop 2 |

| Non-immigrant, white | 11 (42) | 10 (48) |

| Somali | 9 (35) | 7 (33) |

| Hispanic | 2 (8) | 1 (5) |

| Cambodian | 2 (8) | 1 (5) |

| Sudanese | 1 (4) | - |

| Non-immigrant, black | 1 (4) | 1 (5) |

| Ugandan | - | 1 (5) |

Focus group training was preceded by a four-hour orientation to CBPR organized by the community-academic research team. This session introduced the principles of CBPR with didactics, breakout sessions and team-building exercises. The idea of utilizing focus groups in the context of CBPR and specifics on the research study were also conveyed.

The first phase of focus group training involved a 12-hour participatory workshop on focus group moderation taught by a national focus group expert (see acknowledgments). The workshop introduced the methodology behind focus groups, the role of focus groups in research, the strengths and weaknesses of focus groups as a research method, guidelines to conducting focus groups successfully and the various roles involved in holding focus groups. Logistics of the focus group environment were also discussed: ideal group size, creating a welcoming environment, working with low English literacy individuals, and cultural appropriateness. While training encompassed the roles of focus group moderator, note taker and analyst, emphasis was placed on improving participants’ abilities in moderation. Specifically, they were taught skills of active listening, body language, probes and the art of follow-up questions. The workshop was highly interactive, and included several role-playing sessions where participants practiced their skills. Those leading the workshop evaluated the trainees and provided constructive critiques.

At the conclusion of the workshop, participants organized themselves into groups of three members. Each group held practice focus groups within their neighborhoods, work environments, or friend groups. Pre-written scripts were available, or participants could write their own questions on a topic of their choosing. Participants created detailed reports from these practice sessions. The practice focus group reports were circulated among the other workshop participants for feedback. The research team also reviewed these reports to assess thoroughness, depth of solicited information and clarity; recommendations for improvement were provided. This activity was intended to increase focus group facilitators’ comfort with their roles, allow feedback on the overall process, and provide an opportunity for addressing any concerns prior to application of their skills to the TB project at HEC.

Workshop participants who completed practice focus groups then conducted focus groups at HEC. Focus group facilitators performed a total of ten focus groups with HEC students and staff to elucidate their knowledge and perception of TB, its transmission, prevention and management; these results are reported elsewhere25. Scripted focus group questions were designed jointly by the research team and focus group trainees; questions were finalized after review by adult education specialists familiar with the culture and literacy levels at HEC. Focus groups were conducted either in English or participants’ native languages. Professional interpreters were available during focus groups, except for those conducted with native English speakers. Focus group trainees alternately served in the moderator, note-taker and analyst roles. Moderators worked off the script, while adding probes and follow-up questions as appropriate. The note-taker recorded responses and key phrases for each question. The analyst noted themes within the discussion, interactions between group members and noteworthy body language. Six of these ten focus groups were observed by a member of the research team for quality assurance.

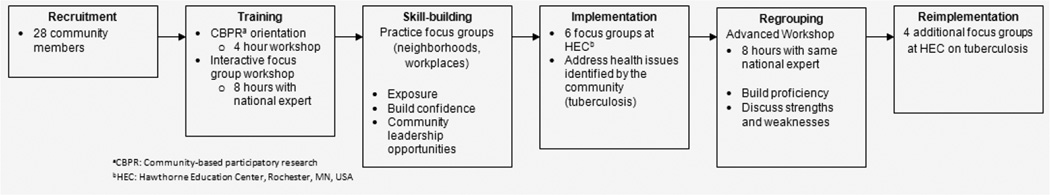

Following the session, facilitators debriefed with each other to reflect on key moments. This time was also used to critique their individual performances. Using an audio transcript generated from the focus groups and notes, each team created a report with key quotes and themes for each of the questions. These were evaluated by the research team for thoroughness, quality and depth of ideas obtained from the focus groups. Following the first six of these focus groups, trainees reconvened for an additional eight-hour workshop with the same focus group expert to address any challenges that arose and to further enhance their skills. Strengths and weaknesses of the previous focus groups were examined. Role playing exercises were designed to mimic these challenges. In the weeks following the second workshop, an additional four focus groups were held using the same format as earlier. The full training timeline is shown in Figure 1. Upon completion of ten total focus groups, focus group facilitators interested in helping with data analysis were assembled as an analysis sub-group. Two facilitators chose to participate. After data analysis, all facilitators had the opportunity to confirm or critique themes extracted from the focus group sessions.

Figure 1.

Timeline - Development of focus group infrastructure

Throughout the focus group training and implementation, community trainees were compensated $150 for workshop attendance and $50 for facilitation of individual focus groups. Additional reimbursement was given to those involved in transcribing audio recordings from the focus group.

Program evaluation methods

Focus group trainee performance as well as training quality and impact in the context of CBPR were evaluated throughout the process by observation. Observers included community and academic RHCP leadership as well as focus group trainees. More than one member of this RHCP leadership team (authors) was present at every phase of training and implementation. The leadership team held regular meetings during which observations were elucidated and reflected in meeting minutes. Trainees’ observations were formally invited in two discussion groups during the focus groups training.

Observation of trainee proficiency focused on perceived execution of focus group moderation skills that were taught and practiced during the training sessions. Further, the quality of data (transcripts) obtained from TB focus groups at HEC was used as a marker of trainee proficiency. Specifically, transcripts were evaluated for how well the content responded to the research questions and for the richness of data. Transcripts that reflected a large amount of data that did not relate to the research questions reflected opportunities for growth of focus group moderation skills through re-direction and facilitation approach. Transcripts that lacked richness of data often revealed missed opportunities to unpack interesting statements by focus group participants. These assessments were made by academic members of the partnership with experience in focus groups moderation (see acknowledgements).

Evaluation of the training program as a whole was based on observations by the RHCP leadership team and focus group trainees. Observations focused on the question of how well the training prepared trainees to competently conduct community-based, culturally diverse focus groups in the context of CBPR.

Quantitative program evaluation components included measurement of attendance and attrition. Finally, indirect measures of success were retrospectively identified on the basis of sustainability, additional programming and peer-reviewed publications.

Evaluation Results

Attendance and attrition

Twenty-seven trainees attended the initial workshop which focused on moderation skills, while 21 attended the follow-up session. Ethnicities and races of the participants included non-immigrant white, Cambodian, Hispanic, Somali, Sudanese and Ugandan (Table 1). Of the 27 initial participants, 20 were from the community, and the rest were from academic institutions. The overall attrition rate between the two training sessions was 22%. Those discontinuing involvement with the project were all community members; thus community attrition was 30%. Attrition occurred secondary to scheduling, time constraints, conflicting life events and waning interest in the project. Motivation for continued involvement in the project included vested interest in the needs of one’s community as well as monetary compensation.

Proficiency of trainees in focus groups moderation

Community members were equipped with skills in conducting focus groups, and specifically practiced communication, note-taking, transcription and analysis skills. Over the span of multiple focus groups, increasing aptitude in research skills was apparent, particularly in the quality of transcripts produced. Practice and experience, in accordance with the number of focus groups completed, was the single most important predictor of effective focus groups moderation.

Effectiveness of training program in the context of CBPR

Community and academic partners repeatedly observed that focus group training strengthened relationships between HEC and Mayo Clinic, ultimately resulting in joint ownership of both the learning process and outcomes. Community members noted an improved perception of research, and their trust in academic partners grew. This was further demonstrated by their request for continued research involvement at HEC in future projects.

As academic partners shared their research skills with the community, individual capacity of the participating community members was enhanced. They were oriented to core CBPR principles, and subsequently had the opportunity to apply that learning in a dynamic research process. Further, focus group training had a transformative effect on HEC as an institution; focus groups have emerged as a common mechanism for influencing policy change and procedures.

Community members likewise brought their interpersonal skills, language abilities and vast relationships within the community to the partnership. Through the teaching generously offered by the community, researchers gained invaluable insight into specific needs and cultural nuances of the surrounding community. Similarly, researchers learned about existing health barriers in various ethnic groups in the community.

Research capacity of the academic-community partnership also grew. Focus group trainees applied their newly acquired skills within the partnership, thereby creating a dynamic qualitative framework for pursuing other health topics within HEC and the broader community. Allocation of roles within the research team, training of personnel and overcoming initial cultural obstacles all contributed to formation of this qualitative infrastructure.

Indirect measures of training impact

Since this initial training session, two additional groups of community members have been trained in focus groups moderation in the same manner. This training sustainability reflects the success of the original program. Furthermore, the larger Rochester community became aware of community member focus group skills. This provided further leadership opportunities for those trained in focus group methodology, as they were asked to apply their newfound skills in other outlets. For example, one group of trainees independently used focus groups to address the issue of acculturation among middle school students from Somalia. The report generated from this focus group was recognized by the Office of the Superintendent as important to informing school policy. Finally, data generated from this community-based qualitative infrastructure has been recognized in several peer-reviewed publications25–28. This work has laid the foundation for RHCP becoming a productive CBPR partnership with experience in deploying data-driven programming and outcomes assessment among immigrant and refugee populations.

Discussion

Using a case study format, we described the development of a community-based qualitative research infrastructure using focus group training. Participants were trained to achieve a baseline level of competence in focus group skills, particularly moderation. The training process enhanced trust and partnership building among community and academic members.

Having community members instead of academicians facilitate focus groups has unique advantages. Specifically, orientation to qualitative research methodology empowered community members to be equal partners in targeting health needs in their own neighborhoods29. They broached health topics with great cultural sensitivity and insight while demonstrating enhanced interpretation of comments and unspoken cultural nuances within sessions. In focus groups with low English literacy participants, community members dually served in translator and moderator roles, thus enriching the linguistic nuances of the data. According to Williams et al., communication to the community from a community member provides a more compelling argument13. This arrangement likely created a less threatening environment compared to academic-led sessions, thereby prompting greater responsiveness by the HEC community13. These strategies may contribute to reductions in health disparities by minimizing barriers to care, thus increasing health research and the spread of results in marginalized communities29.

Looking into the future, this training project has already established a framework for future assessments and programming through our community-academic partnership. This community-based qualitative infrastructure may be applied to diverse health issues that emerge from community partners now and in the future.

Limitations and lessons learned

There are several challenges and limitations to this approach. Few community members had prior experience in health fields or research. Therefore, significant time was invested in the training and development sessions. This is a time commitment that may be unsustainable for some partnerships.

Despite numerous training sessions, community members still have limited experience compared to academic or corporate counterparts who routinely conduct focus groups. Therefore, while community focus group facilitators extract richer data in some cases, quality may be suboptimal in other cases. For example, our experience showed that early focus group data suffered from a lack of sufficient follow-up questions to initial participant responses. This affinity for 'active listening,' whereby the focus group moderator is able to seize on important conversation that is highly relevant to the research questions, was the skill most lacking from early focus group moderation. Likely as a result of increased experience and the follow-up skills session, the last four focus groups were of significantly higher quality than the initial six.

Sustaining these projects may be difficult if the time commitment for trainees results in waning interests12. In our experience, important conflicting life events led to the attrition rate of 30% among the community focus group moderators. This reality should be countered with fair financial support and maximal scheduling flexibility on the part of the organizers. Nevertheless, attrition necessitates continual recruitment and training that are both time-consuming and expensive12.

In retrospect, inclusion of a human subjects protection curriculum, covering topics such as institutional review boards and ethical consent, may have enhanced the training of community members as researchers. Instead, consent for focus groups was obtained by separate research staff. Merging these two skills may be synergistic for community members who are actively involved in the broader CBPR partnership.

Lastly, while we used an observation-based program evaluation, this process may have been more robust with additional assessment tools, such as in-depth interviews, focus groups, or surveys of trainees. This would foster a more formal evaluation mechanism to inform changes for future training sessions.

Conclusion

Focus group training within existing or emerging CBPR partnerships offers the opportunity for individual and organizational capacity building. Our experience with a largely immigrant and refugee population at an adult education center in the U.S. describes a framework for building this capacity. The unique benefits of focus group moderation by community members may offer innovative means of more effectively obtaining qualitative data together with underrepresented communities towards the shared goal of improved health.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the HEC community. The authors also acknowledge with gratitude the role of Richard Krueger, PhD, for his role in training the focus group facilitators.

This project is supported by the National Institutes of Health through a Partners in Research grant, R03 AI082703, by the National Institutes of Health Grant R01-HL-73884 and by Clinical and Translational Science Award (CTSA) Grant UL1-RR-024150 (to the Mayo Clinic).

References

- 1.Horowitz CR, Robinson M, Seifer S. Community-based participatory research from the margin to the mainstream: are researchers prepared? Circulation. 2009;119(19):2633–2642. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.729863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jones L, Wells K. Strategies for academic and clinician engagement in community-participatory partnered research. JAMA. 2007;297(4):407–410. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.4.407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shalowitz MU, Isacco A, Barquin N, Clark-Kauffman E, Delger P, Nelson D, Quinn A, Wagenaar KA. Community-based participatory research: a review of the literature with strategies for community engagement. Journal of Development and Behavioral Pediatrics. 2009;30(4):350–361. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0b013e3181b0ef14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Israel BA, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, Becker AB. Review of community-based research: assessing partnership approaches to improve public health. Annual Review of Public Health. 1998;19:173–202. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.19.1.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Viswanathan M, Ammerman A, Eng E, Garlehner G, Lohr KN, Griffith D, Rhodes S, Samuel-Hodge C, Maty S, Lux L, Webb L, Sutton SF, Swinson T, Jackman A, Whitener L. Community-based participatory research: assessing the evidence. Evidence Report Technology Assessment (Summary) 2004;(99):1–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Potter C, Brough R. Systemic capacity building: a hierarchy of needs. Health Policy and Planning. 2004;19(5):336–345. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czh038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gilbert KL, Quinn SC, Ford AF, Thomas SB. The urban context: a place to eliminate health disparities and build organizational capacity. Journal of Prevention and Intervention in the Community. 2011;39(1):77–92. doi: 10.1080/10852352.2011.530168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Metzler MM, Higgins DL, Beeker CG, Freudenberg N, Lantz PM, Senturia KD, Eisinger AA, Viruell-Fuentes EA, Gheisar B, Palermo AG, Softley D. Addressing urban health in Detroit, New York City, and Seattle through community-based participatory research partnerships. American Journal of Public Health. 2003;93(5):803–811. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.5.803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Segrott J, McIvor M, Green B. Challenges and strategies in developing nursing research capacity: a review of the literature. International Journal of Nursing Studies. 2006;43(5):637–651. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2005.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bailey J, Veitch C, Crossland L, Preston R. Developing research capacity building for Aboriginal & Torres Strait Islander health workers in health service settings. Rural Remote Health. 2006;6(4):556. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Horowitz CR, Arniella A, James S, Bickell NA. Using community-based participatory research to reduce health disparities in East and Central Harlem. Mount Sinai Journal of Medicine. 2004;71(6):368–374. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Israel BA, Krieger J, Vlahov D, Ciske S, Foley M, Fortin P, Guzman JR, Lichtenstein R, McGranaghan R, Palermo AG, Tang G. Challenges and facilitating factors in sustaining community-based participatory research partnerships: lessons learned from the Detroit, New York City and Seattle Urban Research Centers. Journal of Urban Health. 2006;83(6):1022–1040. doi: 10.1007/s11524-006-9110-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Williams KJ, Gail Bray P, Shapiro-Mendoza CK, Reisz I, Peranteau J. Modeling the principles of community-based participatory research in a community health assessment conducted by a health foundation. Health Promotion Practice. 2009;10(1):67–75. doi: 10.1177/1524839906294419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Powell RA, Single HM. Focus groups. International Journal for Quality in Health Care. 1996;8(5):499–504. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/8.5.499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huston P, Rowan M. Qualitative studies. Their role in medical research. Canadian Family Physician. 1998;44:2453–2458. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Krueger Richard A, Anne CM. Focus groups. A practical guide for applied research. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kitzinger J. Qualitative research. Introducing focus groups. British Medical Journal. 1995;311(7000):299–302. doi: 10.1136/bmj.311.7000.299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Halcomb EJ, Gholizadeh L, DiGiacomo M, Phillips J, Davidson PM. Literature review: considerations in undertaking focus group research with culturally and linguistically diverse groups. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2007;16(6):1000–1011. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2006.01760.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sim J. Collecting and analysing qualitative data: issues raised by the focus group. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 1998;28(2):345–352. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1998.00692.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wong LP. Focus group discussion: a tool for health and medical research. Singapore Medical Journal. 2008;49(3):256–260. quiz 261. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goss GL. Focus group interviews: a methodology for socially sensitive research. Clinical Excellence for Nurse Practitioners. 1998;2(1):30–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Clark MJ, Cary S, Diemert G, Ceballos R, Sifuentes M, Atteberry I, Vue F, Trieu S. Involving communities in community assessment. Public Health Nursing. 2003;20(6):456–463. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1446.2003.20606.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Flaskerud JH, Lesser J, Dixon E, Anderson N, Conde F, Kim S, Koniak-Griffin D, Strehlow A, Tullmann D, Verzemnieks I. Health disparities among vulnerable populations: evolution of knowledge over five decades in Nursing Research publications. Nursing Research. 2002;51(2):74–85. doi: 10.1097/00006199-200203000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Huer MB, Saenz TI. Challenges and strategies for conducting survey and focus group research with culturally diverse groups. American Journal of Speech Language Pathology. 2003;12(2):209–220. doi: 10.1044/1058-0360(2003/067). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wieland ML, Weis JA, Yawn BP, Sullivan SM, Millington KL, Smith CM, Bertram S, Nigon JA, Sia IG. Perceptions of Tuberculosis Among Immigrants and Refugees at an Adult Education Center: A Community-Based Participatory Research Approach. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health. 2010:1–9. doi: 10.1007/s10903-010-9391-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wieland ML, Weis JA, Olney MW, Aleman M, Sullivan S, Millington K, O'Hara C, Nigon JA, Sia IG. Screening for Tuberculosis at an Adult Education Center: Results of a Community-Based Participatory Process. American Journal of Public Health. 2011;101(7):1264. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2010.300024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wieland MLNJ, Palmer T, O'Hara C, Weis JA, Nigon JA, Sia IG. Evaluation of a Tuberculosis Education Video among Immigrants and Refugees at an Adult Education Center: A Community-Based Participatory Approach. Journal of Health Communication. 2011 doi: 10.1080/10810730.2012.727952. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wieland MLWJ, Palmer T, Goodson M, Loth S, Omer F, Abbenyi A, Krucker K, Edens K, Sia IG. Physical activity and nutrition among immigrant and refugee women: a community-based participatory research approach. Women's Health Issues. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2011.10.002. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wallerstein NB, Duran B. Using community-based participatory research to address health disparities. Health Promotion Practice. 2006;7(3):312–323. doi: 10.1177/1524839906289376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]