Summary

The NbAlY916/AtAlY4–H2O2–NO pathway mediates multiple Nep1Mo-triggered responses, including stomatal closure, hypersensitive cell death, and defence-related gene expression.

Key words: ALY, disease resistance, hypersensitive response, Nep1, nitric oxide, stomatal closure.

Abstract

Previously, it was found that Nep1Mo (a Nep1-like protein from Magnaporthe oryzae) could trigger a variety of plant responses, including stomatal closure, hypersensitive cell death (HCD), and defence-related gene expression, in Nicotiana benthamiana. In this study, it was found that Nep1Mo-induced cell death could be inhibited by the virus-induced gene silencing of NbALY916 in N. benthamiana. NbALY916-silenced plants showed impaired Nep1Mo-induced stomatal closure, decreased Nep1Mo-induced production of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) and nitric oxide (NO) in guard cells, and reduced Nep1Mo-induced resistance against Phytophthora nicotianae. It also found that the deletion of AtALY4, an orthologue of NbALY916 in Arabidopsis thaliana, impaired Nep1Mo-triggered stomatal closure, HCD, and defence-related gene expression. The compromised stomatal closure observed in the NbALY916-silenced plants and AtALY4 mutants was inhibited by the application of H2O2 and sodium nitroprusside (an NO donor), and both Nep1Mo and H2O2 stimulated guard cell NO synthesis. Conversely, NO-induced stomatal closure was found not to require H2O2 synthesis; and NO treatment did not induce H2O2 production in guard cells. Taken together, these results demonstrate that the NbAlY916/AtAlY4–H2O2–NO pathway mediates multiple Nep1Mo-triggered responses, including stomatal closure, HCD, and defence-related gene expression.

Introduction

Plants have evolved multiple defence mechanisms against phytopathogens, including the hypersensitive response (HR) and stomatal closure (Dangl et al., 1996; Lam et al., 2001; Mur et al., 2008). The HR is considered to be a form of localized hypersensitive cell death (HCD) that results in the formation of necrotic lesions around sites of infection (Hammond-Kosack and Jones, 1996; Greenberg and Yao, 2004). HCD is initiated upon plant–pathogen recognition. In addition to classic gene–gene interactions, the binding of selected pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) and elicitors to the receptors can also trigger the HR, leading to PAMP-triggered immunity (PTI) (Nurnberger et al., 2004; Schwessinger and Zipfel, 2008).

Necrosis and the secretion of ethylene-inducing peptide 1 (Nep1) occurs in taxonomically diverse organisms, including bacteria, fungi, and oomycetes (Gijzen and Nürnberger, 2006). In some cases, microbial Nep1-like proteins (NLPs) are considered to be positive virulence factors that accelerate disease and pathogen growth in host plants through disintegration (Amsellem et al., 2002; Pemberton et al., 2005; Ottmann et al., 2009). However, NLPs trigger cell death and immune responses in many dicotyledonous plants (Pemberton and Salmond, 2004; Gijzen and Nurnberger, 2006; Schwessinger and Zipfel, 2008). It is believed that NLPs may associate with the outer surface of the plasma membrane to trigger the HR (Qutob et al., 2006; Schouten et al., 2008), and global gene expression analyses have revealed overlap between the responses to Nep1 and responses to other elicitors that lead to active ethylene and oxygen production (Bae et al., 2006). It was recently demonstrated that the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) cascade is involved in Nep1Mo (Nep1 from Magnaporthe oryzae)-triggered plant responses, and the MAPK signalling associated with HCD exhibits shared and distinct components with that of stomatal closure (Zhang et al., 2012a ). Bioinformatics and functional genetic screens have been used to identify and characterize genes mediated by such elicitor signalling. However, information on the signalling network is still fragmentary, and many important players involved in Nep1-induced plant immunity remain to be discovered.

High-throughput down-regulated expression screening of a plant cDNA library was previously performed using virus-induced gene silencing (VIGS), and several genes that suppress cell death in Nicotiana benthamiana leaves upon elicitor treatment were identified. The involvement of respiratory burst oxidase homologue (RBOH), vacuolar processing enzyme (VPE), G proteins, and MAPKs in elicitor-triggered plant immunity was demonstrated by Potato virus X (PVX)-based VIGS (Zhang et al., 2010, 2012b ). Here, a cDNA identified in the screen, which encodes an Ally of AML-1 and LEF-1 (ALY) protein that acts as a suppressor of Nep1Mo-mediated immunity in N. benthamiana and Arabidopsis thaliana, is reported. The ALY family is a group of plant RNA-binding proteins. Animals encode only one or two ALY proteins, whereas A. thaliana encodes four ALYs; in comparison, many monocots encode four or more ALYs (Uhrig et al., 2004; Canto et al., 2006). Animal (mouse, Drosophila, and human) and yeast ALY proteins contribute to the export of mRNAs from the nucleus before translation, and join with the exon junction complex of proteins marking mRNAs in the course of splicing (Bruhn et al., 1997; Zhou et al., 2000; Storozhenko et al., 2001). Animal ALY proteins are also known as transcriptional co-activators, and promote the interaction of DNA-binding proteins. However, the function of plant ALYs is unknown.

Here, by employing VIGS, it was found that NbALY916 is involved in the regulation of Nep1Mo-induced stomatal closure, HCD, and pathogen resistance in N. benthamiana. It is also demonstrated that AtALY4, an orthologue of NbALY916 in A. thaliana, plays the same role in Nep1Mo-triggered stomatal closure, HCD, and defence-related gene expression.

Materials and methods

Plant materials, elicitors, and treatment protocol

Nicotiana benthamiana and Arabidopsis were grown in a growth chamber under a 16/8h light/dark cycle at 25 °C. The T-DNA insertion line for AtALY4 used in this study was AtALY4 (CS331800) supplied by the Arabidopsis Resource Center (http://www.arabidopsis.org). The PCR primers (P1, GGGCATCAGGAGTTGAAGTT; P2, GGATCCCATAGATCCCATGA; and LBa1, GCGTGGAC CGCTTGCTGCAACT) were used to check the T-DNA insertions. To prepare Nep1Mo, overnight cultures of Escherichia coli BL21 cells carrying pET32b harbouring the Nep1 Mo gene (GenBank accession no. MGG_08454) were diluted (1:100) in Luria–Bertani medium containing ampicillin (50mg ml–1) and incubated at 37 °C for ~3h. When the OD600 of the culture reached 0.6, Nep1Mo secretion into the culture medium was induced via the addition of 0.4mM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside for 6h. Nep1Mo was expressed as a His-tag fusion protein. Protein purification was performed with Ni-nitrilotriacetic acid resin (QIAGEN, Valencia, CA, USA), and the purified proteins were dialysed against a phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) buffer (pH 7.4) and stored at 20 °C prior to use. Protein concentration was determined using the Bradford reagent (Qutob et al., 2006), and concentrated stock solution (500nM) was prepared.

DNA constructs and seedling infection for virus-induced gene silencing

To amplify a cDNA encompassing the entire open reading frame of NbALY916, the full-length cDNA for NbALY916 was identified with RACE (rapid amplification of cDNA ends) using a SMART RACE amplification kit (BD Bioscience-Clontech, Palo Alto, CA, USA). VIGS for the NbALY916 gene (GenBank accession no. AM167906) in N. benthamiana was performed using PVX, as previously described by Zhang et al. (2009, 2010). The NbALY916 insert was 450bp, which was derived from the 3′ termini of its open reading frame and inserted into the PVX vector in the antisense direction to generate PVX.NbALY916. The construct containing the insert was transformed into Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain GV3101. Bacterial suspensions were applied to the undersides of N. benthamiana leaves using a 1ml needleless syringe. Plants exhibited mild mosaic symptoms 3 weeks after inoculation. The third or fourth leaf above the inoculated leaf, where silencing was most consistently established, was used for further analyses.

Diaminobenzidine (DAB) staining

Following the methods of Thordal-Christensen et al. (1997), leaves were harvested 3h after Nep1Mo treatment and immediately vacuum-infiltrated for 20min with PBS (pH 7.4) containing 0.5% (w/v) DAB. The leaves were placed in light for 10h and then boiled for 20min in 80% ethanol. Quantitative scoring of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) staining in leaves was analysed using Quantity One software (BIO-RAD, Segrate, Italy).

RNA isolation, semi-quantitative transcription–PCR (RT-PCR), and quantitative RT–PCR

The leaf fragments after Nep1Mo inoculation were used for total RNA extraction using the Trizol reagent (TaKaRa, Dalian, China) following the manufacturer’s protocol and then treated with RNase-free DNase (TaKaRa). qRT–PCR was performed on the ABI 7300 Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) and SYBR Premix Ex Taq™(TaKaRa, Dalian, China) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The N. benthamiana genes (NbEF1α and NbActin) and Arabidopsis genes (AtEF1α and AtS16) were used as the internal reference genes to standardize the RNA sample for evaluating relative expression levels. For qRT–PCR assays, three independent biological samples were used, with each repetition having three technical replicates with a gene-specific primer (Supplementary Table S1 available at JXB online)

Stomatal aperture measurements

Stomatal apertures were measured as described by Chen et al. (2004) and Zhang et al. (2009, 2010). Leaves were derived from PVX Nb, NbALY916-silenced plants, Col-0, and AtALY4. Abaxial (lower) epidermises were peeled off and floated in 5mM KCl, 50mM CaCl2, and 10mM MES-TRIS (pH 6.15) in light for 3h to open the stomata fully before experimentation to minimize the effects of other factors in stomatal response, because the mesophyll signals can also significantly influence stomatal behaviour. The epidermal strips then were followed by Nep1Mo (50nM), sodium nitroprusside [SNP; a nitric oxide (NO) donor, 25 mM], and H2O2 (800 μM), respectively, to induce a stomatal response. For cPTIO [2-(4-carboxyphenyl)-4,4,5,5-tetramethylimidazoline-1-oxyl-3-oxide; an NO scavenger] treatment, cPTIO (400 μM) was applied for 1h prior to SNP treatment. The maximum diameter of stomata was measured under an optical microscope. At least 50 apertures in each treatment were obtained and the experiments were repeated three times.

NO measurement in guard cells

NO accumulation was determined using the fluorophore 4,5-diaminofluorescein diacetate (DAF-2DA, Sigma-Aldrich) according to Ali et al. (2007). Epidermal strips were prepared from control and gene-silenced plants, and incubated in 5mM KCl, 50mM CaCl2, and 10mM MES-TRIS (pH 6.15) in the light for 2h, followed by incubation in 20 μM DAF-2DA for 1h in the dark at 30 °C, 65rpm, and finally rinsed three times with 10mM TRIS-HCl (pH 7.4) to wash off excess fluorophore. The dye-loaded tissues were treated with Nep1Mo (50nM), SNP (25mM), and H2O2 (800 μM) for 1h, respectively. And then the fluorescence of guard cells was imaged (excitation wavelength, 470nm; emission wavelength, 515nm; Leica DMR, Germany) and analysed using Quantity One software.

ROS measurement in guard cells

According to the method described by Pei et al. (2000), reactive oxygen species (ROS) measurement in guard cells was detected by using 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescein diacetate (H2DCFDA). Epidermal peels were floated in 5mM KCl, 50mM CaCl2, and 10mM MES-TRIS (pH 6.15) for 2h under light to induce stomatal opening, followed by incubation with 50 μM H2DCFDA for 10min and washing for 20min with incubation buffer. Images of guard cells were obtained 1h after Nep1Mo treatment under a fluorescence microscope (excitation wavelength, 484nm; emission wavelength, 525nm; Leica DMR, Germany). Fluorescence emission from guard cells was analysed using Quantity One software.

Disease resistance assay

One half (right side) of a leaf from PVX Nb and NbALY916-silenced N. benthamiana was infiltrated with either PBS (10nM) orNep1Mo (50nM). Three hours later the leaves were collected and transferred to Petri dishes containing sterile water-saturated filter paper. A 9 mm×9mm hyphal plug of Phytophthora nicotianae was then placed on the surface of the left side of each leaf, which had not been infiltrated with Nep1Mo or PBS. Samples were kept in the dark at 25 °C. Pictures of the lesions were taken at 48h post-inoculation, Leaves then were fixed with 100% ethanol. Resistance evaluation was based on the measurement of the diameter of P. nicotianae lesion size: inhibition=(diameter of control–diameter of elicitor)/diameter of control 100%. Data are means ±SE from three experiments.

Fully expanded Col-0 and AtALY4 mutant leaves collected 3h after Nep1Mo treatment (25 μl) were infiltrated with Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato DC3000 (Pst DC3000) suspension (108 cfu ml–1). Necrotic lesions caused by Pst DC3000 on leaves were observed. Leaves of inoculated plants were harvested and sterilized in 70% ethanol, and homogenized in sterile water. Bacteria were recovered on L-agar medium and induced resistance was defined based on decreases in symptom severity and in planta bacterial numbers (Gerhardt, 1981; Dong et al., 1999).

Results

NbALY916 silencing inhibits cell death in response to Nep1Mo

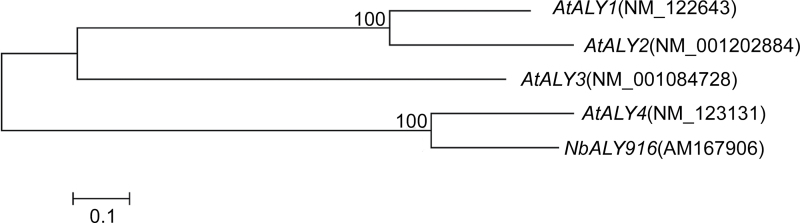

N. benthamiana is the most widely used host for VIGS (Goodin et al., 2008). Purified Nep1Mo inoculated into N. benthamiana leaves can induce cell death (Zhang et al., 2012a). To identify components of the Nep1Mo signalling pathway, a high-throughput in planta down-regulated expression screen of 6000 N. benthamiana cDNAs was performed using a PVX-based VIGS system (Supplementary Fig. S1 at JXB online). Each clone was used to infect two N. benthamiana plants. A common positive control is silencing of the phytoene desaturase (PDS) gene, which results in photobleaching of the silenced regions and is a readily visible phenotype. When photobleaching was apparent, two leaves of candidate plants were infiltrated with Nep1Mo solution. Several cDNAs, including PVX clone #14-4-4, were found to compromise Nep1Mo-triggered cell death upon silencing. Since the silencing of #14-4-4 produced the strongest and most reproducible inhibition of cell death triggered by Nep1Mo, the #14-4-4-silenced line was therefore chosen for further study. The DNA sequence of #14-4-4 showed strong similarity to the C-terminal domain of ALY916 (GenBank accession no. AM167906) from N. benthamiana. To facilitate a more comprehensive comparative analysis of NbALY916, the full-length cDNA for NbALY916 was isolated from N. benthamiana. Three clones of the full-length cDNA, named NbALY916, were sequenced to confirm that the correct gene had been cloned. The predicted protein for NbALY916 is composed of 275 amino acids. The most closely related protein is AtALY4 from A. thaliana (56% amino acid sequence similarity; Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Phylogeny produced from the ALY sequence data of Arabidopsis and N. benthamiana. A bootstrap value of 100 supported the closest relationship between NbALY916 and AtALY4.

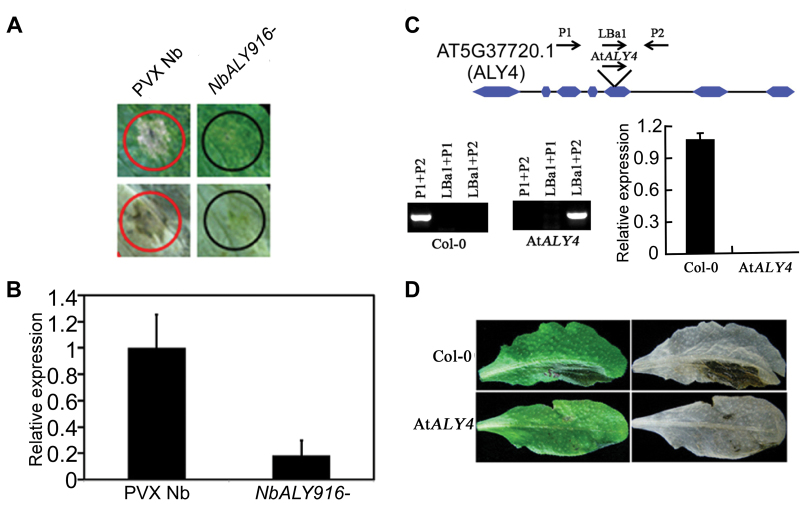

NbALY916 silencing and the mutation of AtALY4 reduces cell death and H2O2 accumulation following Nep1Mo exposure

Reduced expression of NbALY916 resulted in a strong phenotype, inhibiting cell death in N. benthamiana leaves after inoculation with Nep1Mo (Fig. 2A). To confirm the suppression of NbALY916 mRNA in the silenced plants, qRT–PCR was performed. A clear reduction in NbALY916 mRNAs was observed in silenced plants compared with control plants infected by the PVX-VIGS vector alone (Fig. 2B; Supplementary Fig. S2 at JXB online). Thomas et al. (2001) reported that at least 23 nucleotides of perfectly matched sequence are necessary to target a gene for silencing (Thomas et al., 2001). BLAST analysis revealed that NbALY916 showed no significant homology with any expressed sequence tags in the N. benthamiana database (http://compbio.dfci.harvard.edu/tgi/cgi-bin/tgi), and that it shared 100% identity with stretches of only 10 or fewer nucleotides in NbALY617, NbALY1693, and NbALY615 (three homologues of NbALY916 in N. benthamiana). To test whether the VIGS of NbALY916 could affect the expression of the other NbALY genes, their transcriptional level was examined by qRT–PCR using primers that specifically annealed to these gene sequences. The results revealed that the expression of these genes was unaffected in the NbALY916-silenced plants (Supplementary Fig. S3). These results indicate a high degree of target specificity using VIGS. It was also observed that the Nep1Mo-triggered HR was not suppressed in NbALY617-, NbALY1693-, and NbALY615-silenced plants. These data demonstrate that the observed inhibition of cell death was due to the specific silencing of NbALY916.

Fig. 2.

Silencing of NbALY916, the mutation in Arabidopsis AtALY4, and induction of hypersensitivity responses with Nep1Mo (50nM). (A) Leaves (representative of three replicate treatments) from control PVX- and NbALY916-silenced N. benthamiana were infiltrated with Nep1Mo solution simultaneously. The red and black circles indicate cell death and no cell death, respectively. Leaves were removed from plants after 2 d of treatment (upper row) and bleached in ethanol (lower row). (B) First-strand cDNA was generated from total RNA obtained from PVX-only plants or from plants silenced for NbALY916. qRT–PCR was performed with the cDNA and specific primers to the targeted gene, and EF1α as an endogenous control. (C) Schematic representation of T-DNA insertion sites in AtALY4 and genomic structure of the Arabidopsis AtALY4 gene. Exons and introns are represented as a blue box and black lines, respectively; PCR verification of the AtALY4 T-DNA mutant. qRT-PCR analysis of AtALY4 and AtEF1α transcripts in the wild-type (Col-0) and AtALY4 mutant. (D) Cell death phenotype on control and AtALY4 mutant leaves after inoculation with Nep1Mo. Leaves were removed from plants after 2 d of treatment (upper row) and bleached in ethanol (lower row).

As described above, NbALY916 is closely related to an A. thaliana gene, AtALY4. To determine whether mutations in the AtALY4 gene affect Nep1Mo-induced cell death, homozygous lines containing T-DNA insertions in this gene were obtained from the Salk Institute Genomic Analysis Laboratory collection by PCR screen. The T-DNA in the AtALY4 mutant is inserted into the fifth exon of AtALY4. In the allele, wild-type AtALY4 transcripts were did not detected by qRT–PCR (Fig. 2C; Supplementary S2 at JXB online). As expected, Col-0 seedlings showed obvious cell death after treatment with Nep1Mo. Conversely, the AtALY4 mutant showed hyposensitivity to Nep1Mo by displaying no cell death (Fig. 2D).

To test whether the alteration in Nep1Mo-induced cell death was associated with H2O2 accumulation, the H2O2 levels were quantified in vector control and NbALY916-silenced plants. H2O2 production in response to Nep1Mo was much lower in NbALY916-silenced plants (75% reduction over control treatment; Fig. 3A). Light staining was also observed on AtALY4 mutant leaves following Nep1Mo treatment (Fig. 3B). N. benthamiana rbohA and rbohB and A. thaliana rbohD and rbohF, which encode plant NADPH oxidases, are responsible for generating the H2O2 involved in HRs and plant resistance (Torres et al., 2002; Yoshioka et al., 2003; Sagi and Fluhr, 2006). The expression level of rboh genes (NbrbohA and NbrbohB, and AtrbohD and AtrbohF) was decreased significantly in NbALY916-silenced and AtALY4 mutant lines compared with control plants (Fig. 3C, D; Supplementary Fig. S4 at JXB online). These data demonstrate that ALYs regulate H2O2 accumulation in response to Nep1Mo. These results suggest that the compromised cell death observed in NbALY916-silenced plants and the AtALY4 mutant may be associated with a Nep1Mo-induced decrease in H2O2.

Fig. 3.

In situ detection of hydrogen peroxide using DAB staining on leaves of NbALY916-silenced N. benthamiana and the Arabidopsis AtALY4 mutant in response to Nep1Mo. (A) Nicotiana benthamiana leaves silenced for NbALY916 were compared with PVX-only leaves 6h after infiltration of PBS (10mM) or Nep1Mo (50nM). Elicitation with the elicitor was conducted on plants by infiltrating an equivalent elicitor solution of 25 μl. Quantitative scoring of staining in leaves of the control and gene-silenced plants with Nep1Mo treatment. The analysis was repeated for three sets of independently silenced plants in each experiment; the values shown were the means ±SD of duplicate assays. The experiment was repeated twice with similar results. (B) DAB staining of ROS accumulation in the Arabidopsis AtALY4 mutant leaves 6h after inoculation with Nep1Mo. (C) NbrbohA and NbrbohB were analysed by qRT–PCR and normalized to NbEF1α expression. (D) AtrbohD and AtrbohF were analysed by qRT–PCR and normalized to AtEF1α expression. Each measurement is an average of three replicates; Experiments were repeated twice with similar results.

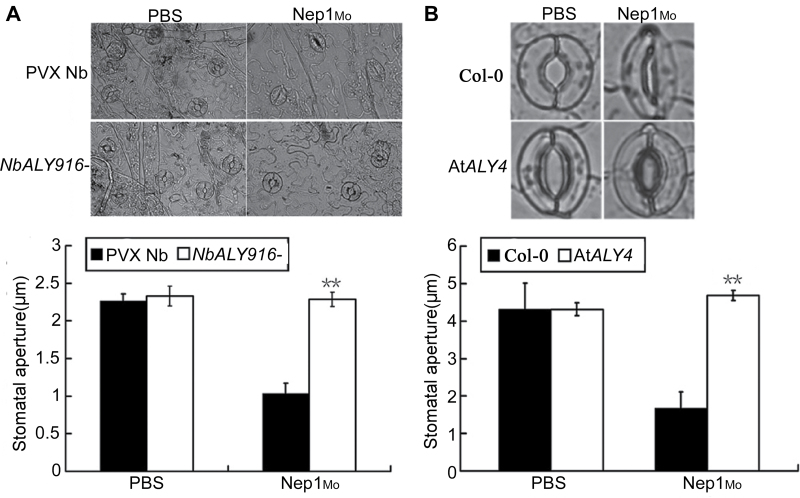

NbALY916 silencing and the mutation of AtALY4 impairs Nep1Mo-activated stomatal closure

Recent studies have shown that stomata play an active role in the innate immune system (Melotto et al., 2006, 2008). It has been reported that elicitors trigger RBOH-, VPE-, and G protein-dependent stomatal closure in N. benthamiana leaves (Zhang et al., 2009, 2010, 2012a), but whether ALY proteins contribute to elicitor-induced stomatal closure remains unclear. The stomatal response of NbALY916-silenced plants exposed to Nep1Mo was examined. It was found that NbALY916-silenced plants failed to close their stomata in response to Nep1Mo, whereas the stomata of control plants showed normal closure responses (Fig. 4A). These results suggest that NbALY916 silencing in plants affects the response to Nep1Mo or affects a general step in stomatal closure that is common to multiple stomatal closure pathways. The AtALY4 mutant was also tested for Nep1Mo-induced stomatal closure. AtALY4 mutant plants were defective in Nep1Mo-induced stomatal closure (Fig. 4B). Nep1Mo-induced stomatal aperture analyses were consequently performed on the NbALY916-silenced plants and AtALY4 mutants. It was found that the NbALY916-silenced plants and AtALY4 mutant plants showed a markedly reduced response to Nep1Mo. Therefore, N. benthamiana NbALY916 and A. thaliana AtALY4 are involved in the Nep1Mo signalling pathways leading to stomatal closure.

Fig. 4.

Stomatal aperture measurements show that Nep1Mo-induced stomatal closure is reduced in NbALY916-silenced N. benthamiana and the Arabidopsis AtALY4 mutant. Stomatal aperture of N. benthamiana (A) and Arabidopsis (B) was measured 3h after incubation in PBS (10mM) and Nep1Mo (50nM). Values represent means ±SE from three independent experiments; n=50 apertures per experiment. Data were compared using the Student’s t-test at the 95% significance level.

NbALY916 silencing and the mutation of AtALY4 decreases Nep1Mo-mediated NO production in guard cells

NO functions as a signal in plant disease resistance (Delledonne et al., 1998; Desikan et al., 2002). It was previously shown that NO plays a critical role in Nep1Mo-induced stomatal closure (Zhang et al., 2012b ). The NbALY916-silenced plants and AtALY4 mutants were insensitive to Nep1Mo-induced stomatal closure (Fig. 4). To determine further the cellular role of ALYs in the regulation of stomatal closure, NO production was compared in NbALY916-silenced and control plants using the NO-specific fluorescent dye DAF-2DA. Without Nep1Mo treatment, the guard cells of the control and NbALY916-silenced plants exhibited similar basal staining for NO. The treatment of epidermal strips with Nep1Mo induced a rapid increase in NO levels, as indicated by the change in fluorescence intensity compared with control (PBS) treatment. An ~90% increase in NO occurred in the guard cells of control plants following Nep1Mo treatment. However, no increase in NO was observed in the guard cells of NbALY916-silenced plants after Nep1Mo treatment (Fig. 5A). Similarly, a decrease in Nep1Mo-induced NO was observed in the AtALY4 mutant (Fig. 5B). The expression levels of nitrate reductase (N. benthamiana NR, A. thaliana NIA) also decreased sharply in the NbALY916-silenced and AtALY4 mutant lines compared with control plants (Fig. 5C, D; Supplementary Fig. S4 at JXB online). This suggests that NR may be the main resource of NO production in Nep1Mo signalling. Taken together, these results indicate that ALY proteins are required for Nep1Mo-mediated NO production in guard cells.

Fig. 5.

Effects of silencing of NbALY916 and mutation in Arabidopsis AtALY4 on NO burst in guard cells in response to Nep1Mo. (A) In all cases, the NO-sensitive dye DAF-2DA was loaded into cells of the epidermal peels, and fluorescence was measured after addition of PBS (10mM) and Nep1Mo (50nM). Quantitative analysis of in vivo NO generation monitored using DAF-2DA fluorescence as shown in A. (B) The epidermal peels of the AtALY4 mutant stained with DAF-2DA upon Nep1Mo treatment and quantification of NO accumulation shown in B. For each treatment, fluorescence and bright-field images were shown. Results from several experiments were compiled in this figure. Experiments were repeated at least three times, and representative images are shown in A. Green indicates the NO burst. Results were presented as the mean (n ≥3) fluorescence intensity per pixel. (C) NbNR was analysed by qRT–PCR and normalized to NbEF1α expression. (D) AtNIA was analysed by qRT–PCR and normalized to AtEF1α expression. Each measurement is an average of three replicates; experiments were repeated twice with similar results.

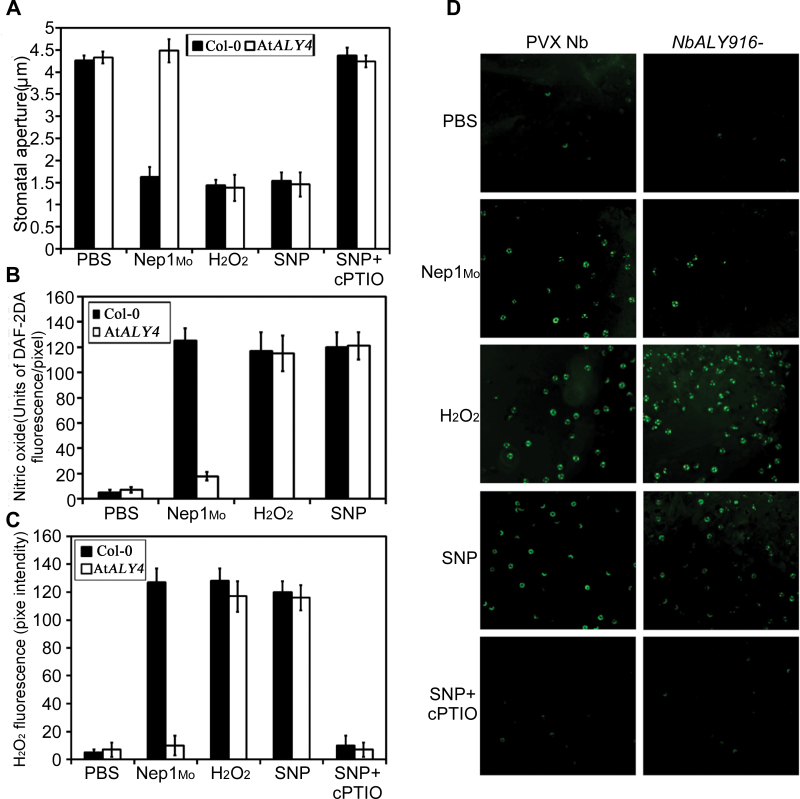

NO acts downstream of ALY and H2O2

In addition to NO, H2O2 is also involved in elicitor-induced stomatal closure (Srivastava et al., 2009). To investigate the possible interaction between ALY, H2O2, and NO in Nep1Mo-induced stomatal closure, the effects of an NO scavenger (cPTIO) on Nep1Mo-, H2O2-, and NO-induced stomatal closure were assessed in NbALY916-silenced plants or AtALY4 mutant lines. Nep1Mo-induced stomatal closure was greatly reduced in the presence of cPTIO, in agreement with previous reports (Zhang et al., 2012b ). Here, cPTIO inhibition of SNP-induced stomatal closure was observed, similar to the inhibition of Nep1Mo-induced stomatal closure (P<0.001), indicating a requirement for NO in Nep1Mo-induced stomatal closure and that NO does not require H2O2 generation to initiate stomatal closure.

The role of NO in H2O2-induced stomatal closure was further examined by monitoring NO synthesis in response to applied H2O2. Epidermal fragments were loaded with DAF-2DA to test for changes in NO-induced fluorescence. A significant increase in NO-induced guard cell fluorescence was observed in H2O2-treated epidermal fragments compared with control tissue (P<0.001), demonstrating H2O2-mediated NO production in guard cells (Fig. 6B). Importantly, SNP-induced NO synthesis was abolished by co-incubation with cPTIO, correlating these data with those from the stomatal bioassays (P<0.001; Fig. 6A). Moreover, NO-induced fluorescence was not significantly different between Nep1Mo- and H2O2-treated epidermal fragments (P>0.05).

Fig. 6.

NO generation is required for H2O2-induced stomatal closure. (A) Wild-type Arabidopsis and AtALY4 mutant leaves were treated with Nep1Mo, H2O2, or SNP in the absence or presence of 2-phenyl-4,4,5,5-tetremethylimidazolinone-1-oxyl 3-oxide (cPTIO). Stomatal apertures were measured 3h after treatment. The data are displayed as estimated means and associated 95% confidence intervals (CIs). (B) Epidermal fragments were incubated with DAF2-DA in MES-KCl buffer. NO synthesis was monitored in controls and 3h after treatment with Nep1Mo, H2O2, or SNP, in the absence or presence of cPTIO. Data are displayed as estimated mean pixel intensities and associated 95% CIs. (C) Quantitative analysis of in vivo H2O2 generation monitored using H2DCF fluorescence as shown in D. (D) Epidermal fragments were incubated with (H2DCFDA) in MES-KCl buffer. Hydrogen peroxide synthesis was monitored in controls and 3h after treatment with Nep1Mo, H2O2, or SNP, in the absence or in the presence of cPTIO.

The data in Fig. 6A indicate that H2O2 is not required for NO-induced stomatal closure. However, He et al. (2013) reported that in Vicia faba guard cells, exogenous NO, applied in the form of the NO donor SNP, did induce H2O2 production. Consequently, the effects of SNP on H2O2 generation in A. thaliana guard cells were analysed using the fluorescent probe H2DCFDA (Fig. 6C). SNP did induce guard cell H2DCF fluorescence, as did Nep1Mo treatment, which has been previously shown to mediate H2O2 production (Pei et al., 2000; Desikan et al., 2002). However, H2DCFDA is not specific for H2O2 and it also reacts with NO (Hempel et al., 1999). To determine whether the effects of SNP treatment on H2DCF fluorescence were merely attributable to the reaction of NO with H2DCF, a number of experimental treatments were performed (Fig. 6D). Most importantly, treatment with cPTIO greatly reduced H2DCF fluorescence in response to SNP. The reaction with cPTIO is specific to NO and not H2O2; therefore, these data indicate that the fluorescence observed in the SNP-treated guard cells was due to exogenously applied NO and not H2O2, and NO does not induce H2O2 production in N. benthamiana or A. thaliana. Together, these data demonstrate unequivocally that NO functioned downstream of H2O2 and was involved in ALY-mediated stomatal closure triggered by Nep1Mo.

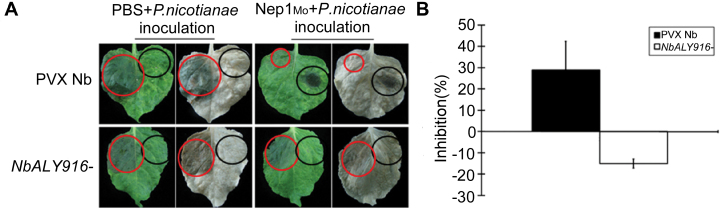

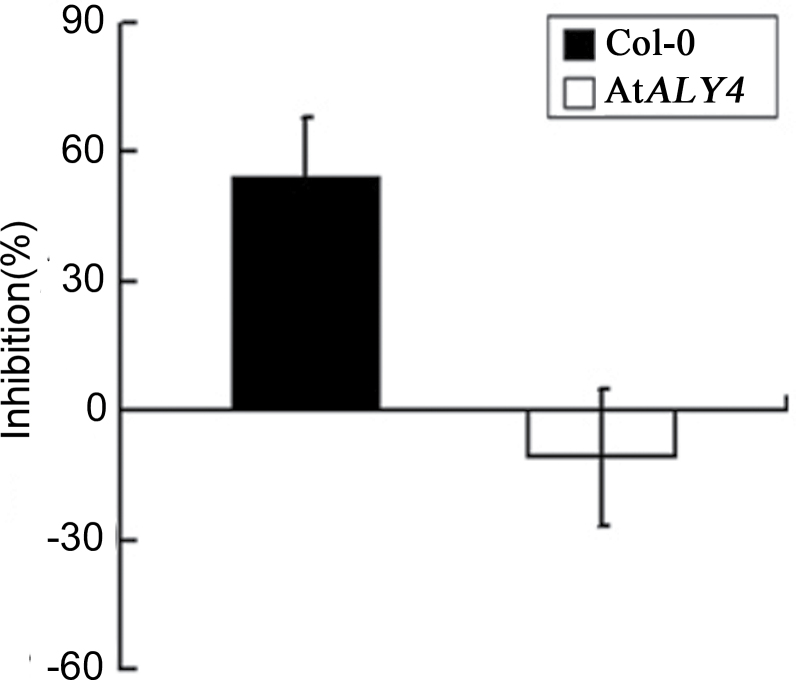

NbALY916 participates in the Nep1Mo-triggered resistance of N. benthamiana to P. nicotianae

Elicitors can induce systemic resistance in plants (Garcia-Brugger et al., 2006; Yang et al., 2009). Here it was tested whether the silencing of NbALY916 had effects on Nep1Mo-triggered disease resistance against P. nicotianae. All of the NbALY916-silenced leaves were infiltrated with Nep1Mo at one spot, and 4h later the leaf surfaces opposite the Nep1Mo-infiltrated sides were inoculated with 2 mm×2mm mycelial plugs of P. nicotianae. Systemic resistance was assessed 48h after P. nicotianae inoculation by comparing and measuring the sizes of the lesions. Typical water-soaked Phytophthora lesions appeared within 24h post-inoculation (hpi). Expanding disease lesions around the inoculated spots were observed in the silenced plants at 48 hpi. However, Nep1Mo treatment significantly inhibited the expansion of lesions in PVX control-inoculated leaves of N. benthamiana (Fig. 7). These findings indicate that NbALY916 is required for Nep1Mo-induced disease resistance to P. nicotianae.

Fig. 7.

NbALY916-silenced plants display enhanced sensitivity to P. nicotianae. (A) For the control and gene-silenced plants, fully expanded leaves collected 4h after Nep1Mo treatment (10 μl, black circle) were inoculated with a 2 mm×2mm hyphal plug on the left leaf surfaces opposite the Nep1Mo-infiltrated sides. Then, the leaves were placed in Petri dishes containing filter paper saturated with sterilized distilled water and kept under a 16h day/8h night regime at 25 °C. Pictures of the lesions were taken at 48h post-inoculation and the lesion diameter (red circle) was measured. (B) Resistance evaluation based on diameter of lesion spots. Inhibition rate=(diameter of necrosis with PBS treatment–diameter of necrosis with Nep1Mo treatment)/diameter of control. Data are means ±SE from eight experiments.

AtALY4 is involved in Nep1Mo-triggered resistance towards Pst DC3000

To determine whether AtALY4 has an effect on Pst DC3000-induced disease symptoms upon Nep1Mo treatment in A. thaliana, leaves from AtALY4 mutant plants and Col-0 were infiltrated with Nep1Mo at one spot, then wild-type and AtALY4 mutant plants were infiltrated (108 cfu ml–1) with Pst DC3000 using a syringe. As expected, Col-0 showed water-soaked necrotic lesions accompanied by chlorosis, while the AtALY4 mutant plants exhibited accelerated necrotic lesions without visible chlorosis upon PBS treatment. Interestingly, when the growth of Pst DC3000 was monitored at 0, 1, 2, and 4 d post-infiltration, the bacterial population on the AtALY4 mutant was significantly increased compared with that on the inoculated control plants in response to Nep1Mo (Fig. 8). These results suggest that AtALY4 significantly contributed to Nep1Mo-induced plant resistance against Pst DC3000 in A. thaliana, at least for the length of time that bacterial growth was monitored.

Fig. 8.

Nep1Mo induced a significant increase in number and size of Pst DC3000 lesions on AtALY4 mutant lines. Resistance evaluation based on diameter of Pst DC3000 lesion spots.

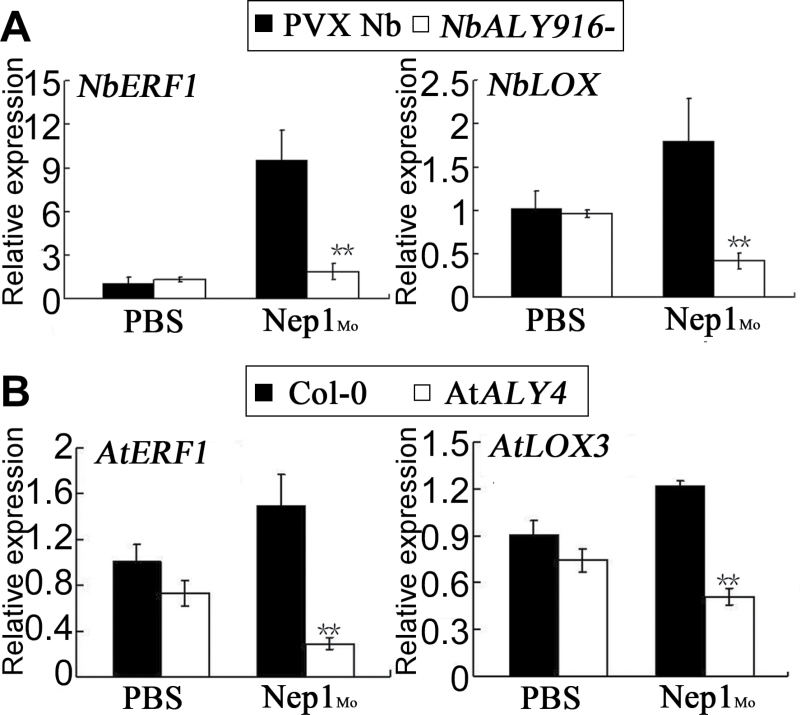

NbALY916-silenced and AtALY4 mutant plants show altered defence-related gene expression

Differences in the accumulation of H2O2 and NO were detected between the NbALY916-silenced plants and control plants. Distinct levels existed in the AtALY4 mutant and wild type as well, suggesting that the NbALY916-silenced plants and AtALY4 mutant exhibit altered defence-related gene expression. To address this possibility, the kinetics of the expression of selected genes following Nep1Mo infiltration were examined by qRT–PCR not only in NbALY916-silenced and PVX control plants, but also in AtALY4 mutant and wild-type plants (Fig. 9; Supplementary Fig. S4 at JXB online). The jasmonic acid signalling gene LOX encodes a lipoxygenase (Delker et al., 2006), while ERF1 is involved in ethylene signalling (Yang et al., 1997; Alonso et al., 1999; Ding et al., 2002). The expression of these genes showed no significant difference in NbALY916-silenced plants and control plants treated with PBS. After treatment with Nep1Mo, the expression levels of ERF1 and LOX3 were up-regulated by 9- and 1.8-fold compared witho their previous expression levels, respectively. However, the Nep1Mo-mediated expression of ERF1 and LOX3 was down-regulated by 7- and 5-fold, respectively, in the NbALY916-silenced plants compared with control plants. Such suppression of the Nep1Mo-mediated expression of ERF1 and LOX3 was also detected in the AtALY4 mutant compared with the wild type. These results reveal that the silencing of NbALY916 in N. benthamiana and the mutation of AtALY4 both influence the expression of defence-related genes.

Fig. 9.

Expression analysis of ERF and LOX in response to Nep1Mo (50nM). (A) At 6h after treatment with or without Nep1Mo (50nM), leaf samples were harvested from the inoculation site on the lower and the upper leaves; N. benthamiana EF1α expression is used to normalize the expression value in each sample, and relative expression values were determined against buffer or PVX-infected plants using the comparative Ct method (2–ΔΔCt). (B) Transcript levels of ERF and LOX in the wild-type and the Arabidopsis AtALY4 mutant 6h after inoculation with Nep1Mo. Bars represent the mean (three biological replicates) ±SD.

Discussion

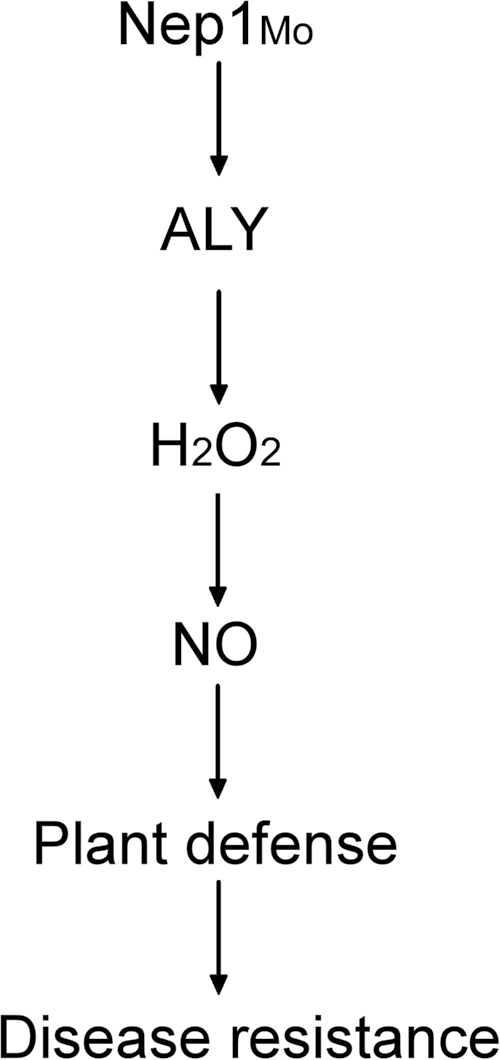

The observation that Nep1Mo can induce cell death in N. benthamiana and the ability to conduct VIGS in N. benthamiana provided an excellent strategy for identifying plant genes that play a role in Nep1Mo signalling. Here, it was found that a loss of the N. benthamiana gene NbALY916 and its orthologue (AtALY4) in A. thaliana resulted in the inhibition of Nep1Mo-mediated cell death and stomatal closure. The inoculation of NbALY916-silenced N. benthamiana with P. nicotianae induced accelerated necrotic lesions upon Nep1Mo treatment. Similar to NbALY916-silenced N. benthamiana, inoculation with Pst DC3000 of the AtALY4 mutant line induced accelerated necrotic lesions in response to Nep1Mo. Moreover, it was found that NO acts downstream of ALY and H2O2 to participate in Nep1Mo signalling. Based on the phenotypes observed, a model was developed that involves ALY, H2O2, and NO in Nep1Mo-mediated immunity (Fig. 10).

Fig. 10.

Speculative model of new signalling components in the Nep1Mo-activated signalling pathway. Virus-induced gene silencing of NbALY916 and mutation of Arabidopsis AtALY4 placed ALY downstream of the Nep1Mo recognition event. NO acts downstream of ALY and H2O2 in guard cells to contribute to Nep1Mo-induced resistance.

NbALY916 silencing and the mutation of AtALY4 suppresses Nep1Mo-triggered HR and stomatal closure

ALY proteins, which belong to a highly conserved polypeptide nuclear localization signal protein family, exist in plants, yeast, Drosophila, nematodes, and mammals. A previous study found that ALY proteins play an important role in the activation of transcription, pre-mRNA splicing, and mRNA export in mammals (Zhou et al., 2000; Gatfield and Izaurralde, 2002). However, no subsequent reports were found regarding the function of ALY proteins in plants. Unlike previous strategies, VIGS was employed to investigate the role of NbALY916 in Nep1Mo-mediated HR. The results indicate that the silencing of NbALY916 and mutation of its orthologue in A. thaliana, AtALY4, compromised Nep1Mo-mediated HR, confirming a positive role for ALYs in cell death regulation. ALY-mediated cell death caused by Nep1Mo was associated with the rapid generation of H2O2, displaying a similarity to pathogen-induced HRs. Most importantly, an ALY loss-of-function study demonstrated that ALY is involved in the regulation of HRs caused by the M. oryzae elicitor Nep1Mo. These results indicate that ALYs may be a convergence point for Nep1Mo signal transduction pathways.

The present results show that the silencing of NbALY916 and mutation of AtALY4 compromised Nep1Mo-induced stomatal closure and was accompanied by less NO accumulation in guard cells (Fig. 4 and 5), which suggests that ALYs control Nep1Mo-mediated stomatal closure. NO is a key mediator of abscisic acid (ABA)-induced stomatal closure in peas (Neill et al., 2002), V. faba (Garcia-Mata and Lamattina, 2002, 2003), and A. thaliana (Bright et al., 2006). These data indicate that ALY proteins mediate Nep1Mo-triggered stomatal closure via NO signalling. An increasing number of studies in plants have confirmed the importance of stomata in plant immunity, and stomatal closure has been observed as a result of PTI. The results showed that Nep1Mo-induced resistance against P. nicotianae was also compromised in NbALY916-silenced plants (Fig. 7). This suggests that NbALY916 is involved in the regulation of plant immunity, controlling stomatal apertures and inhibiting the entry of pathogens into plant leaves during infection.

NO acts downstream of ALY-mediated H2O2 generation in response to Nep1Mo

The requirement for NO and H2O2 in elicitor-mediated stomatal closure has been shown previously (Zhang et al., 2009). However, NO and H2O2 synthesis were thought to occur in parallel, until Lum et al. (2002) demonstrated that exogenous H2O2 induced the rapid production of NO in Phaseolus aureus guard cells. A report provided pharmacological evidence indicating that endogenous H2O2-mediated NO generation plays an important role in UV-B-induced stomatal closure in V. faba (He et al., 2013). In the present study, NO synthesis in response to H2O2 in N. benthamiana and A. thaliana guard cells was demonstrated. Importantly, this process was correlated with Nep1Mo-induced stomatal closure. Using a pharmacological approach, it has been shown that NO synthesis is required for H2O2-induced stomatal closure. In contrast to the findings of He et al. (2013), the data in the present study demonstrate that NO does not induce H2O2 synthesis as required for stomatal closure. Moreover, the data show unequivocally that NO does not induce H2O2 synthesis in guard cells. Rather, the H2DCF fluorescence monitored in the presence of SNP was actually attributable to the reaction of the dye with NO, not H2O2. However, He et al. (2013) did report that SNP induced H2DCF fluorescence and stomatal closure, so it is possible that guard cell responses differ between N. benthamiana, A. thaliana, and V. faba.

Further evaluation of this response and the potential source of NO induced by exogenous H2O2 revealed that NO production and stomatal closure could both be attributed to NR activity. The expression level of NR in NbALY916-silenced plants and AtALY4 mutants in Nep1Mo-induced NO synthesis and stomatal closure was significant and indicates a role for NR activity in these responses (Fig. 5C, D). Previous studies have reported that H2O2-induced NO generation in the guard cells of V. faba was related to NR activity. The analysis of NR–NO activity provides unequivocal evidence that A. thaliana NR has the capacity to generate NO from nitrite (Bright et al., 2006). Guard cells of the double mutant nia1, nia2 do not generate NO in response to H2O2, indicating that NR is responsible for the production of NO in guard cells in response to exogenous H2O2. Importantly, it has been demonstrated that nia1, nia2 plants do generate H2O2 in response to ABA, providing further evidence that NR acts downstream of ABA-mediated H2O2 generation to produce NO and to induce stomatal closure. It has been suggested that NR-mediated NO generation may act downstream of ALY-mediated H2O2 generation in Nep1Mo signalling.

NbALY916 silencing and the mutation of AtALY4 suppresses Nep1Mo-induced pathogen resistance

NbALY916-silenced plants and AtALY4 mutants exhibited increased susceptibility to pathogen invasion. The data presented suggest that ALYs function as a positive regulator of broad spectrum resistance during pathogen invasion. The silencing of NbALY916 in N. benthamiana conferred decreased resistance to P. nicotianae after Nep1Mo treatment. Moreover, upon Nep1Mo application, NbALY916-silenced N. benthamiana showed a decrease in LOX and ERF expression compared with control plants, suggesting that NbALY916 is critically involved in Nep1Mo-triggered defence responses. AtALY4 plants homozygous for the T-DNA insertion were susceptible to infection by Pst DC3000 upon Nep1Mo treatment. As expected, decreased LOX and ERF expression was observed in the AtALY4 mutant relative to wild-type plants during Pst infection. Interestingly, this suggests that AtALY4 functions in the A. thaliana defence response to Pst infection in a manner similar to that of N. benthamiana upon P. nicotianae infection. The decreased level of salicylic acid (SA)-responsive (LOX) and ethylene-responsive (ERF) gene expression in N. benthamiana and A. thaliana supports the notion that ALYs are involved in SA and ethylene-mediated signalling pathways during pathogen infection. Analyses of NbALY916-silenced and AtALY4 mutant plants revealed that plant disease resistance is conferred by ALY gene expression during pathogen infection.

In conclusion, a VIGS-based forward genetic screen was developed for the identification of new targets involved in Nep1Mo signalling. Although the original intention of the study was to identify genes involved in Nep1Mo-induced HR, a gene, NbALY916, that when silenced inhibited cell death and stomatal closure upon Nep1Mo application was identified. Although the precise role of NbALY916 in the Nep1Mo signalling pathway is debatable and requires confirmation, the results present a new role for ALYs in P. nicotianae and bacterial disease development.

Supplementary data

Supplementary data are available at JXB online.

Fig. S1 Screening of Nicotiana benthamiana gene coding hypersensitive cell death induced by Nep1Mo by virus-induced gene silencing.

Fig. S2 Expression analysis of NbALY916 and AtALY4 in NbALY916-silenced plants and the AtALY4 mutant by qRT–PCR.

Fig. S3 Local induction of hypersensitivity responses on PVX-, PVX.NbALY615-, PVX.NbALY617-, and PVX.NbALY1693-infected N. benthamiana leaves in response to Nep1Mo.

Fig. S4 Expression analysis of genes associated with redox control in NbALY916-silenced plants and the AtALY4 mutant by qRT–PCR.

Table S1. Gene-specific primers for qRT–PCR.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by the National Science Foundation for Distinguished Young Scholars of China (grant no. 31325022) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 31071645 and 30871605). We thank David Baulcombe (Sainsbury Laboratory, John Innes Centre, Norwich, UK) for the gift of PVX vector and Agrobacterium strains, and Xueping Zhou (College of Agriculture and Biotechnology, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou, China) for the gift of N. benthamiana seeds.

References

- Ali R, Ma W, Lemtiri-Chlieh F, Tsaltas D, Leng Q, von Bodman S, Berkowitz GA. 2007. Death don’t have no mercy and neither does calcium: Arabidopsis CYCLIC NUCLEOTIDE GATED CHANNEL2 and innate immunity. The Plant Cell 19, 1081–1095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alonso JM, Hirayama T, Roman G, Nourizadeh S, Ecker JR. 1999. EIN2, a bifunctional transducer of ethylene and stress responses in Arabidopsis. Science 284, 2148–2152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amsellem Z, Cohen BA, Gressel J. 2002. Engineering hypervirulence in a mycoherbicidal fungus for efficient weed control. Nature Biotechnology 20, 1035–1039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bae H, Kim MS, Sicher RC, Bae HJ, Bailey BA. 2006. Necrosis- and ethylene-inducing peptide from Fusarium oxysporum induces a complex cascade of transcripts associated with signal transduction and cell death in arabidopsis. Plant Physiology 141, 1056–1067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bright J, Desikan R, Hancock JT, Weir IS, Neill SJ. 2006. ABA-induced NO generation and stomatal closure in Arabidopsis are dependent on H2O2 synthesis. The Plant Journal 45, 113–122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruhn L, Munnerlyn A, Grosschedl R. 1997. ALY, a context-dependent coactivator of LEF-1 and AML-1, is required for TCRalpha enhancer function. Genes and Development 11, 640–653 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canto T, Uhrig JF, Swanson M, Wright KM, MacFarlane SA. 2006. Translocation of Tomato bushy stunt virus P19 protein into the nucleus by ALY proteins compromises its silencing suppressor activity. Journal of Virology 80, 9064–9072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen YL, Huang RF, Xiao YM, Lu P, Chen J, Wang XC. 2004. Extracellular calmodulin-induced stomatal closure is mediated by heterotrimeric G protein and H2O2. Plant Physiology 136, 4096–4103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dangl JL, Dietrich RA, Richberg MH. 1996. Death don’t have no mercy: cell death programs in plant–microbe interactions. The Plant Cell 8, 1793–1807 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delker C, Stenzel I, Hause B, Miersch O, Feussner I, Wasternack C. 2006. Jasmonate biosynthesis in Arabidopsis thaliana—enzymes, products, regulation. Plant Biology 8, 297–306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delledonne M, Xia Y, Dixon RA, Lamb C. 1998. Nitric oxide functions as a signal in plant disease resistance. Nature 394, 585–588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desikan R, Griffiths R, Hancock J, Neill S. 2002. A new role for an old enzyme: nitrate reductase-mediated nitric oxide generation is required for abscisic acid-induced stomatal closure in Arabidopsis thaliana . Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA 99, 16314–16318 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding CK, Wang CY, Gross KC, Smith DL. 2002. Jasmonate and salicylate induce the expression of pathogenesis-related-protein genes and increase resistance to chilling injury in tomato fruit. Planta 214, 895–901 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong HS, Delaney TP, Bauer DW, Beer SV. 1999. Harpin induces disease resistance in Arabidopsis through the systemic acquired resistance pathway mediated by salicylic acid and the NIM1 gene. The Plant Journal 20, 207–215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Brugger A, Lamotte O, Vandelle E, Bourque S, Lecourieux D, Poinssot B, Wendehenne D, Pugin A. 2006. Early signaling events induced by elicitors of plant defenses. Molecular Plant-Microbe Interactions 19, 711–724 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Mata C, Lamattina L. 2002. Nitric oxide and abscisic acid cross talk in guard cells. Plant Physiology 128, 790–792 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Mata C, Lamattina L. 2003. Abscisic acid, nitric oxide and stomatal closure—is nitrate reductase one of the missing links? Trends in Plant Science 8, 20–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gatfield D, Izaurralde E. 2002. REF1/Aly and the additional exon junction complex proteins are dispensable for nuclear mRNA export. Journal of Cell Biology 159, 579–588 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerhardt P. 1981. Manual of methods for general bacteriology. Washington, DC: American Society for Microbiology [Google Scholar]

- Gijzen M, Nurnberger T. 2006. Nep1-like proteins from plant pathogens: recruitment and diversification of the NPP1 domain across taxa. Phytochemistry 67, 1800–1807 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodin M, Chakrabarty R, Yelton S. 2008. Membrane and protein dynamics in virus-infected plant cells. Methods in Molecular Biology 451, 377–393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg JT, Yao N. 2004. The role and regulation of programmed cell death in plant–pathogen interactions. Cellular Microbiology 6, 201–211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HammondKosack KE, Jones JDG. 1996. Resistance gene-dependent plant defense responses. The Plant Cell 8, 1773–1791 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He JM, Ma XG, Zhang Y, Sun TF, Xu FF, Chen YP, Liu X, Yue M. 2013. Role and interrelationship of Gα protein, hydrogen peroxide, and nitric oxide in ultraviolet B-induced stomatal closure in Arabidopsis leaves. Plant Physiology 161, 1570–1583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hempel SL, Buettner GR, O’Malley YQ, Wessels DA, Flaherty DM. 1999. Dihydrofluorescein diacetate is superior for detecting intracellular oxidants: comparison with 2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate, 5(and 6)-carboxy-2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate, and dihydrorhodamine 123. Free Radical Biology and Medicine 27, 146–159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam E, Kato N, Lawton M. 2001. Programmed cell death, mitochondria and the plant hypersensitive response. Nature 411, 848–853 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lum HK, Butt YK, Lo SC. 2002. Hydrogen peroxide induces a rapid production of nitric oxide in mung bean (Phaseolus aureus). Nitric Oxide 6, 205–213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melotto M, Underwood W, He SY. 2008. Role of stomata in plant innate immunity and foliar bacterial diseases. Annual Review of Phytopathology 46, 101–122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melotto M, Underwood W, Koczan J, Nomura K, He SY. 2006. Plant stomata function in innate immunity against bacterial invasion. Cell 126, 969–980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mur LAJ, Kenton P, Lloyd AJ, Ougham H, Prats E. 2008. The hypersensitive response; the centenary is upon us but how much do we know? Journal of Experimental Botany 59, 501–520 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neill SJ, Desikan R, Clarke A, Hancock JT. 2002. Nitric oxide is a novel component of abscisic acid signaling in stomatal guard cells. Plant Physiololy 128, 13–16 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nurnberger T, Brunner F, Kemmerling B, Piater L. 2004. Innate immunity in plants and animals: striking similarities and obvious differences. Immunological Reviews 198, 249–266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ottmann C, Luberacki B, Kufner I, et al. 2009. A common toxin fold mediates microbial attack and plant defense. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA 106, 10359–10364 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pei ZM, Murata Y, Benning G, Thomine S, Klusener B, Allen GJ, Grill E, Schroeder JI. 2000. Calcium channels activated by hydrogen peroxide mediate abscisic acid signalling in guard cells. Nature 406, 731–734 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pemberton CL, Salmond GPC. 2004. The Nep1-like proteins—a growing family of microbial elicitors of plant necrosis. Molecular Plant Pathology 5, 353–359 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pemberton CL, Whitehead NA, Sebalhia M, et al. 2005. Novel quorum-sensing-control led genes in Erwinia carotovora subsp carotovora: identification of a fungal elicitor homologue in a soft-rotting bacterium. Molecular Plant-Microbe Interactions 18, 343–353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qutob D, Kemmerling B, Brunner F, et al. 2006. Phytotoxicity and innate immune responses induced by Nep1-like proteins. Plant Cell 18, 3721–3744 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sagi M, Fluhr R. 2006. Production of reactive oxygen species by plant NADPH oxidases. Plant Physiology 141, 336–340 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schouten A, van Baarlen P, van Kan JAL. 2008. Phytotoxic Nep1-like proteins from the necrotrophic fungus Botrytis cinerea associate with membranes and the nucleus of plant cells. New Phytologist 177, 493–505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwessinger B, Zipfel C. 2008. News from the frontline: recent insights into PAMP-triggered immunity in plants. Current Opinion in Plant Biology 11, 389–395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava N, Gonugunta VK, Puli MR, Raghavendra AS. 2009. Nitric oxide production occurs downstream of reactive oxygen species in guard cells during stomatal closure induced by chitosan in abaxial epidermis of Pisum sativum. Planta 229, 757–765 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storozhenko S, Inze D, Van Montagu M, Kushnir S. 2001. Arabidopsis coactivator ALY-like proteins, DIP1 and DIP2, interact physically with the DNA-binding domain of the Zn-finger poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase. Journal of Experimental Botany 52, 1375–1380 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ThordalChristensen H, Zhang ZG, Wei YD, Collinge DB. 1997. Subcellular localization of H2O2 in plants. H2O2 accumulation in papillae and hypersensitive response during the barley–powdery mildew interaction. The Plant Journal 11, 1187–1194 [Google Scholar]

- Thomas CL, Jones L, Baulcombe DC, Maule AJ. 2001. Size constraints for targeting post-transcriptional gene silencing and for RNA-directed methylation in Nicotiana benthamiana using a potato virus X vector. The Plant Journal 25, 417–425 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres MA, Dangl JL, Jones JD. 2002. Arabidopsis gp91phox homologues AtrbohD and AtrbohF are required for accumulation of reactive oxygen intermediates in the plant defense response. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA 99, 517–522 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uhrig JF, Canto T, Marshall D, MacFarlane SA. 2004. Relocalization of nuclear ALY proteins to the cytoplasm by the tomato bushy stunt virus P19 pathogenicity protein. Plant Physiology 135, 2411–2423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshioka H, Numata N, Nakajima K, Katou S, Kawakita K, Rowland O, Jones JD, Doke N. 2003. Nicotiana benthamiana gp91phox homologs NbrbohA and NbrbohB participate in H2O2 accumulation and resistance to Phytophthora infestans. The Plant Cell 15, 706–718 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y, Zhang H, Li G, Li W, Wang X, Song F. 2009. Ectopic expression of MgSM1, a Cerato-platanin family protein from Magnaporthe grisea, confers broad-spectrum disease resistance in Arabidopsis. Plant Biotechnology Journal 7, 763–777 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang YO, Shah J, Klessig DF. 1997. Signal perception and transduction in defense responses. Genes and Development 11, 1621–1639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang HJ, Li DQ, Wang MF, Liu JW, Teng WJ, Cheng BP, Dong SM, Zheng XB, Zhang ZG. 2012a. Nicotiana benthamiana MAPK cascade and WRKY transcription factor participate in Nep1Mo-triggered plant responses. Molecular Plant-Microbe Interactions 25, 1639–1653 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang HJ, Dong SM, Wang MF, Wang W, Song WW, Dou XY, Zheng XB, Zhang ZG. 2010. The role of vacuolar processing enzyme (VPE) from Nicotiana benthamiana in the elicitor-triggered hypersensitive response and stomatal closure. Journal of Experimental Botany 61, 3799–3812 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang HJ, Fang Q, Zhang ZG, Wang YC, Zheng XB. 2009. The role of respiratory burst oxidase homologues in elicitor-induced stomatal closure and hypersensitive response in Nicotiana benthamiana. Journal of Experimental Botany 60, 3109–3122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang HJ, Wang MF, Wang W, Li DQ, Huang Q, Wang YC, Zheng XB, Zhang ZG. 2012b. Silencing of G proteins uncovers diversified plant responses when challenged by three elicitors in Nicotiana benthamiana. Plant, Cell and Environment 35, 72–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou ZL, Luo M, Straesser K, Katahira J, Hurt E, Reed R. 2000. The protein Aly links pre-messenger-RNA splicing to nuclear export in metazoans. Nature 407, 401–405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.