Abstract

Researchers have examined the predictors of adolescent gang membership, finding significant factors in the neighborhood, family, school, peers, and individual domains. However, little is known about whether risk and protective factors differ in predictive salience at different developmental periods. The present study examines predictors of joining a gang, tests whether these factors have different effects at different ages, and whether they differ by gender using the Seattle Social Development Project (SSDP) sample (n=808). By age 19, 173 participants had joined a gang. Using survival analysis, results showed that unique predictors of gang membership onset included living with a gang member, antisocial neighborhood, and antisocial peer influences in the previous year. No time or gender interactions with predictors were statistically significant.

Keywords: gang membership, risk factors, adolescent development, life course

Homicide, robbery, violence, property crime, and substance abuse result in enormous monetary, social, and personal costs. These and other criminal acts have been consistently linked to gang membership (Battin, Hill, Abbott, Catalano, & Hawkins, 1998; Esbensen, Peterson, Taylor, & Freng, 2009; Gatti, Tremblay, Vitaro, & McDuff, 2005; Howell, 2012; Thornberry, Krohn, Lizotte, Smith, & Tobin, 2003). Thus, it is important to learn why youth join gangs and how to interrupt this process. To date, developmental research on the predictors of joining a gang has been rare. The present study uses longitudinal data to predict gang membership from dynamic social developmental (family, school, peer group, and neighborhood) factors assessed from age 10 through age 18.

Current Research on Predictors of Gang Involvement And Relevant Developmental Theory

Current Research on Predictors of Gang Involvement

Both cross sectional and longitudinal studies have examined the potential causes of gang membership. The cross-sectional studies are informative since they identify potential factors that could be driving the youth’s gang status; however, the design is inherently limited because without temporal ordering it is difficult to distinguish whether the associations identified are causes or consequences of gang membership.

Cross-sectional studies

Cross-sectional studies have identified correlates of gang membership in multiple environmental domains. Individual factors found to be associated with gang membership include delinquency (Esbensen et al., 2009; Stoiber & Good, 1998), frequent alcohol and drug use (Esbensen et al., 2009), and low guilt and neutralization techniques (Esbensen et al., 2009). Family influences include low parental monitoring (McDaniel, 2012), poor parental relationships (Stoiber & Good, 1998), disorganized family structure (Stoiber & Good, 1998), and gang association of family members (Kissner & Pyrooz, 2009). Even when controlling for indicators of low self-control and other salient risk factors, Kissner and Pyrooz (2009) found that gang involvement of parents, older relatives, and siblings all significantly predicted gang membership, highlighting the familial influences of gang involvement. Qualitative researchers have found that gang members often report that their family members, such as siblings, cousins, and uncles, are also gang members, but that membership is rarely deliberately passed down directly from parents to children (Duran, 2013; Moore, 1991). In the school domain, an overall antisocial school environment is correlated with gang membership (Esbensen et al., 2009). Other research suggests that poorly functioning schools with high levels of student and teacher victimization, large student-teacher ratios, poor academic quality, poor school climates, and high rates of social sanctions (e.g., suspensions, expulsions, and referrals to juvenile court) hold a greater percentage of students who form and join gangs (Howell, 2010). Finally, involvement with delinquent peers has also been associated with gang membership when examined cross-sectionally (Esbensen et al., 2009).

Longitudinal studies

Several longitudinal studies, which make a stronger case for causal relationships, have examined the risk factors for gang membership. Risk factors measured in all five environmental domains (individual, family, school, peer group, and neighborhood) have been found to predict joining a gang (Howell & Egley, 2005).

The first longitudinal examination of the predictors of gang membership (Hill, Howell, Hawkins, & Battin Pearson, 1999) used data from the Seattle Social Development Project to explore childhood (age 10–11) risk factors for adolescent gang membership (age 13–18). The Seattle researchers examined 26 potential risk factors for delinquency, violence, and substance abuse collected from prior cross-sectional and longitudinal studies. Twenty-one of these factors across five developmental domains significantly predicted later joining a gang, indicating that the predictors of gang membership are similar to predictors of delinquency, violence and substance use. An examination of effect sizes indicated that all of the factors were of a similar magnitude of impact (mean odds ratio 2.4, range 1.5 to 3.7), with strong predictors being distributed across several domains; for example, the following risk factors increased odds of joining a gang by more than 3 times: Family structure (single parent family, OR=3.0), Low Academic Achievement in the Grades 5 and 6 (3.1), Individual Early Marijuana Initiation (3.7), and Neighborhood Drug Availability (3.6). Moreover, Hill, et al, created a summary score combining significant risk factors across domains and found that this aggregate risk measure increased the odds of gang membership dramatically: for each successive quartile of accumulated, multi-domain risk, the odds of joining a gang approximately doubled, such that those youth with exposure to 7 or more risks in elementary school had more than 13 times greater odds of joining a gang than those exposed to 0 to 1 risk (Hill, Lui, & Hawkins, 2001). Data from this longitudinal panel are used in the current paper to examine the time-varying contribution of social-developmental influences on joining a gang.

Thornberry, Krohn, et al. (2003) examined the bivariate relationships among 40 risk factors (measured in early adolescence) and later gang membership in the longitudinal Rochester Youth Development Study. Like Hill et al. (1999), they found that risk factors in all five environmental domains significantly predicted adolescent gang membership for males; but for females, risk factors in all but the family domain were predictive. Thornberry and colleagues also conducted a multivariate analysis that is discussed below.

Using a measure that included, but was not limited to gangs, Lacourse et al. (2006) sought to identify individual early childhood behavioral profiles that predict “early-onset deviant peer group involvement” (p. 566). In a longitudinal sample of 1037 boys from low socioeconomic areas in Canada, they found that a behavior profile which was classified by low prosociality, hyperactivity and fearlessness was significantly predictive of deviant peer-group involvement. In an ethnically diverse sample of 998 females and males, Dishion, Veronneau, and Myers (2010) examined three predictors (school marginalization, low academic achievement, and problem behavior, all measured at ages 11 and 12) of trajectories of gang membership at age 13–14, and subsequent trajectories of peer deviancy training and violent behavior. Each of these three predictors was significantly associated with subsequent gang membership two years later, which, in turn predicted deviance training, and finally, violence in late adolescence.

While informative, longitudinal studies which use risk factors measured at just one time point to predict joining a gang at a later time do not allow for the examination of developmentally relevant, proximal precursors of adolescent gang membership. A key issue is whether or not risk factors for gang membership vary over the life course—as seen in longitudinal studies of delinquency. Tanner-Smith, Wilson, and Lipsey (in press) examined prospective longitudinal panel studies of delinquency, revealing that risk factors vary in strength from one developmental period to another (e.g., from childhood to early and late adolescence and adulthood, from early adolescence to late adolescence and adulthood, and from late adolescence to adulthood). This comprehensive review finds that the strongest and most robust risk factors for crime during adolescence and early adulthood are those that represent prior delinquent or criminal behavior. Family risk factors measured during childhood are also particularly strong risk factors for later criminal behavior, along with poor school performance. However, the influence of birth family fades after adolescence when the family no longer acts as one of the primary agents of socialization. Similarly, none of the school domain risk factors during early adolescence were strong predictors of later criminal behavior.

Two studies have taken this developmental approach by measuring risk factors for joining a gang at several time points across adolescence. The Denver Youth Study (DYS), a longitudinal study of 1,527 youth residing in high-risk neighborhoods in Denver, Colorado, examined 36 potential predictors across 5 domains and found that significant predictors measured in the two years prior to gang membership onset included truancy, suspension from school, problem use of alcohol and marijuana, arrest, weak attitudes regarding the wrongfulness of delinquent acts, making excuses for undesirable behavior, externalizing behavior, higher rates of delinquency, and association with antisocial peers (Huizinga, Weiher, Espiritu, & Esbensen, 2003). Interestingly, when examining risk factors at each of three time points (again, measured in the two years preceding onset), they found that the same risk factors were predictive of joining a gang at ages 13–14, 15–16, or 17–18. However, the authors did not report tests of changes in predictive influence of these risk factors over time.

In the Pittsburgh Youth Study (PYS), a longitudinal study of 1,517 boys attending public schools in Pittsburgh in 1987, risk factors for joining a gang were also analyzed in a subset of the sample (Lahey, Gordon, Loeber, Stouthamer-Loeber, & Farrington, 1999). This analysis of the PYS data focused on 320 selected high-risk boys, of whom 183 were African American and 137 were White. Of the 95 boys in this subsample who joined a gang, 78 were African American and 17 were White. Lahey and colleagues used survival analysis to predict gang membership onset at each year from age 8 to 19, and found that conduct problems, delinquency and substance use predicted joining a gang in the next period. Subsequent analyses of the subsample of African American youth also examined family structure, household income, parental supervision and neighborhood crime which did not predict membership at either the bivariate or multivariate level. They then tested the interaction between age and various risk factors to determine whether certain risk factors were more salient at different developmental stages. They found that the effects of baseline conduct disorder, family income, delinquent peers, and family supervision varied over time. Specifically, the effects of baseline conduct disorder decreased over time, the effect of antisocial peers increased over time, and the direction of the influence of both family income and parental supervision depended on the young person’s age. Higher family income served as a protective factor later in adolescence, but in early adolescence this factor significantly increased the likelihood of joining a gang. Interestingly, low parental supervision predicted gang membership onset in early adolescence, but actually decreased the risk of gang membership in late adolescence. In a separate study using the same data, Gordon et al. (2004) also found that prior delinquent behavior was significantly associated with joining a gang.

Howell (2012) reports that, to date, the only developmental theory specifically aimed at explaining gang membership is interactional theory (Thornberry, Lizotte, Krohn, Smith, & Porter, 2003). Thornberry, Lizotte, et al. (2003) hypothesized that both early childhood predictors as well as more proximal influences predict gang membership. They suggested that risk factors for gang membership could be found in several interacting domains, including individual, family, peer, school, and neighborhood, and argued that different environmental domains might be more influential at different developmental stages in childhood and adolescence. Thornberry, Krohn, et al. (2003) tested these hypotheses using path analysis in which structural influences, including neighborhood disadvantage, were modeled to affect gang membership through, among other things, social bonding (to school and family) and antisocial peer influences. They found that neither neighborhood disadvantage nor family bonding significantly influenced joining a gang either directly or indirectly in their model, but that school bonding and association with antisocial peers did have significant effects on the odds of gang membership later in adolescence in the expected directions. However, they cautioned that, while temporal ordering was modeled between the predictors and the outcome, some of the predictors (such as social bonding and antisocial peers) were measured simultaneously, making the direction of influence among predictors difficult to establish.

Theoretical Foundations of the Present Study

The present study is guided by three complementary theoretical perspectives, the Social Development Model (Catalano & Hawkins, 1996; Hawkins & Weis, 1985), Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems Theory (Bronfenbrenner, 1979, 1989), and Life Course Theory (Elder, 1985). The Social Development Model (Catalano & Hawkins, 1996; Hawkins & Weis, 1985) specifies hypotheses regarding the relationships among risk and protective factors in the etiology of both prosocial and antisocial behaviors. The social development process involves five sequential constructs: opportunities for involvement in activities and interactions with others, the degree of involvement and interaction, the rewards and costs individuals receive from these involvements and interactions, the social bond that develops between those individuals and the socializing unit, and the set of the beliefs, norms, and values of the social unit. The theory hypothesizes two parallel, but distinct developmental pathways, one reflecting prosocial opportunities, involvement, rewards, bonding and beliefs and the other reflecting antisocial opportunities, involvement, rewards, bonding and beliefs. The model also specifies that an individual’s skills determine whether the experienced involvement (pro- or antisocial) is rewarding or not. In the present study, the social-developmental predictors (as described in the Methods section below) operationalized these theoretically relevant constructs of prosocial and antisocial opportunities, involvements, rewards and costs, bonds, and norms and beliefs.

Like the Social Development Model, Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems theory (Bronfenbrenner, 1979, 1989) emphasizes that family socialization processes operate in a larger context that includes influences from peer, school, and neighborhood contexts. Thus the social-developmental influences described above are assessed in each of these contexts and all four contexts are included in the current analyses. Finally, Life Course Theory (Elder, 1985; Gotlib & Wheaton, 1997; Sampson & Laub, 1992) emphasizes the importance of the timing of developmental influences, and suggests that predictors from the four domains of experience may differentially influence outcomes such as joining a gang at different developmental periods.

Gender considerations

Overall, it is well documented that boys are more likely than girls to join a gang. Indeed, nationwide the majority of gang members are males (National Youth Gang Center, 2010). While the proportion of females involved in gangs has increased in the last few decades (Howell, 2012; Peterson, 2012), the research on whether or not risk and protective factors operate differently for males and females across adolescent development is sparse (Bell, 2009).

Bell (2009) found few differences in the risk factors for gang membership for boys and girls, asserting that environmental influences in the family, school, and peer domains were significantly related to gang membership for both genders. As previously mentioned, Thornberry, Krohn, et al. (2003) found differences between risk factors for males and females only in the family domain. Hill et al. (1999) also examined whether significant predictors of gang membership were moderated by gender, and found substantial similarity among males and females in the risk factors associated with gang participation.

While there is limited research on how risk and protective factors for gang membership differ by gender, studies examining gender differences in risk and protective factors for delinquency in general may be informative. These studies have shown mixed results. Fagan, Van Horn, Hawkins, and Arthur (2007) found that boys not only experienced more risk and fewer protective factors, but also that these factors were more highly associated with serious delinquency for boys than for girls. Similarly, Kroneman, Loeber, and Hipwell (2004) found that the effects of neighborhood disadvantage on delinquency were stronger for boys than for girls. On the other hand, Penney, Lee, and Moretti (2010) found that those risk factors for violent delinquency which have been validated for boys were equally relevant for girls. Whether the strength of certain environmental predictors of joining a gang vary by gender remains an empirical question. It is possible that peers are more influential for boys, while other environmental factors, such as family characteristics, are more salient predictors of joining a gang for girls.

The present study investigates the processes that predict joining a gang in a sample of adolescents surveyed annually from age 10 through age 16 and again at ages 18, 21 and 24. Drawing from developmental theoretical and conceptual frameworks, we address three research questions. First, what are the dynamic predictors of joining a gang in adolescence? Second, do the effects of these predictors vary over time? Third, do the effects of these predictors vary by gender?

Method

Participants

Data were drawn from the Seattle Social Development Project (SSDP), a longitudinal study consisting of 808 participants who were in grade 5 in 1985 in Seattle Public Schools. There were approximately equal numbers of males (51%) and females (49%), and the racial and ethnic makeup of the sample was 47% European American, 26% African American, 22% Asian American, and 5% Native American. Study participants were sampled from 18 Seattle elementary schools serving students from high-crime neighborhoods, though participants also came from other neighborhoods as a result of mandatory bussing to achieve racial desegregation. The 808 participants whose parents consented to their participation in the longitudinal study were approximately 77% of the 5th graders in participating schools.

A significant portion of participants were from low-income families. The median annual family income in 1985 was approximately $25,000. Forty-six percent of parents reported a maximum family income of less than $20,000 per year in 1985, and 52% of the student sample were eligible for the free or reduced school lunch program in grades 5, 6, or 7.

Procedures

Student survey data were collected in 1985 when participants were, on average, 10 years old (M = 10.3, SD = .52), annually each spring through 1991 when students progressing normally were in 10th grade, and again in the spring of 1993 when participants progressing normally were in 12th grade and were approximately 18 years old. Subsequently, surveys have been administered every three years. In grades 5 and 6, surveys were group-administered questionnaires completed in class. Youth who left study schools were individually interviewed. Starting in 1988, participants were individually interviewed in person. The interviews asked for the youth’s confidential responses to a wide range of questions regarding family, community, school, and peers, as well as their attitudes and experiences with gangs, alcohol, drugs, drug selling, violence, weapon use, delinquency, and victimization. Early in the study the interviews took about one hour and youth received a small incentive (e.g., an audiocassette tape) for their participation; later they received monetary compensation. Retention rates for the sample have remained above 91% since 1989. In addition, adult caretakers (83% of whom were the subject’s mother) were interviewed in the fall of 1985 and annually each spring from 1986 through 1991. All data collection procedures were approved by the University of Washington Human Subjects Review Committee.

Measures

Gang membership

In each survey from 7th through 10th grade, again in 12th grade, and every three years in adulthood participants were asked, “Do you currently belong to a gang?” Participants who endorsed this item were then asked to give the name of the gang, so as to distinguish gangs from informal peer groups. The most commonly named gangs were the Bloods, the Crips, and the Black Gangster Disciples. Gang names were vetted in conjunction with the King County Gang Task Force, and only those with credible names were counted. Additionally, at age 21 and 24 participants were asked if they had ever belonged to a gang and, if so, how old they were when they first joined. There were some inconsistencies in reporting across time. Sensitivity analyses revealed that those who ever reported joining a gang but responded negatively at a different time were not significantly different from those who consistently reported being in a gang on an index of childhood individual risk (F(2,98)=2.07, p < .13), nor on middle school delinquency (F(2,98)=1.98, p < .14). However, all those who ever reported gang membership were significantly different on these measures than those who never reported gang membership (F(3,122)=3.03, p <.03 and F(3,120)=2.77, p < .04, respectively). Therefore, we chose to use an inclusive measure of gang membership. That is, if a participant ever reported having been in a gang, the youth was coded as (1); otherwise (0). From these prospective and retrospective measures we estimated the age at which these individuals first joined a gang.

Time-varying predictors of joining a gang

We used multiple items in the family, school, peer, and neighborhood domains to measure possible environmental risk and protective factors. Composite variables were created by standardizing and averaging relevant items from each domain at each of the seven survey waves (5th–10th grades and again in 12th grade). This allowed for a global assessment of the youth’s social environment at each time point in adolescence. Given that student self-reported information in each environmental domain was consistently available across time points, these surveys were most appropriate for the current analysis. Thus, all items comprising the time-varying predictors of joining a gang came from the student interviews. Descriptions and example of items included in these variables measured at each age are presented below.

Prosocial family environment

This composite variable representing the prosocial family environment consisted of items which captured family management, conflict (reverse coded), involvement, and bonding. Examples of items included: “The rules in my family are clear,” “Our family members get along well with each other,” “On weekdays, how many meals does your family eat together each day?” and “Do you share your thoughts and feelings with your mother?” Across waves there was an average of 23 items and Chronbach’s α ranged from .74 to .80.

Prosocial school environment

The composite variable representing the school environment captured the constructs of school bonding, opportunities, involvement and rewards. Examples of items included: “I like school,” “I have lots of chances to take part in class activities,” “My teacher gives me help learning when I need it,” and “I feel safe at my school.” Across waves there was an average of 25 items and Chronbach’s α ranged from .70 to .77.

Prosocial peer environment

This composite variable captured the extent to which the respondent’s three closest friends provided prosocial influences. Examples of items included: “Does this person [first best friend] try to do well in school,” and “does this person let you know when you have done something well?” Across waves there was an average of five items and Chronbach’s α ranged from .25 to .89.

Antisocial peer environment

This composite variable measured the extent to which the respondent’s three closest friends as well as other peers provided antisocial influences. Items included: “Does this person [first best friend] do things that get them into trouble with the teacher?” and “How many kids do you know personally who in the past year have done something that could have gotten them in trouble with the police?” Across waves there was an average of 12 items and Chronbach’s α ranged from .68 to .89.

Prosocial neighborhood environment

This variable captured neighborhood bonding, opportunities and rewards. Items included: “I like my neighborhood,” “Kids from my neighborhood have a chance to be successful,” and “There are people in my neighborhood who are proud of me when I do well.” Across waves there was an average of seven items and Chronbach’s α ranged from .65 to .79.

Antisocial neighborhood environment

Finally, the composite variable representing antisocial aspects of one’s neighborhood included items such as: “Tell me how much the following describe your neighborhood: Crime? Drug selling? Abandoned buildings?” Across waves there was an average of 10 items and Chronbach’s α ranged from .60 to .86.

Living with a gang member

In addition to the composite environmental variables, a single measure marking whether an individual was living with a gang member at each year was included. At age 21 participants were asked if they had ever lived with a gang member, how old they were when they first started living with this person, and for how long they were in this living arrangement. This measure was included in the model as a time-varying predictor, so that beginning with the first year the participant reported living with a gang member and for the appropriate number of subsequent years, the individual was coded as (1), and (0) otherwise. For example, if a person reported having first lived with a gang member at age 12 and living with that person for three years, the youth was coded as (0) for ages 10 and 11, (1) for ages 12, 13 and 14, and (0) at subsequent ages.

Time-fixed Control variables

Early childhood demographic and individual risk factors known to be associated with gang membership, all measured in grades 5, 6, or 7, were used as time-fixed control variables in the analyses. Race and ethnicity (European American, African American, Asian American, and Native American) and gender were both self-reported in grade 5. Socioeconomic status was a composite variable comprised of three items (standardized and averaged): eligibility for the free or reduced school lunch program (from school records), household income, and parental education. The latter two measures were reported by an adult caregiver. Finally, an index of childhood individual risk, measured in grades 5 and 6, was included. The possible scores on this index ranged from zero to nine, as the index included nine individual risk factors demonstrated in this sample to be associated with gang membership in a cumulative fashion (Hill et al., 1999). Individual items included: externalizing behavior problems, hyperactivity, few conventional beliefs, low neighborhood attachment, low educational aspirations, low school commitment, low school attachment, low educational achievement, and learning disability.

Analysis

In order to examine the dynamic predictors of joining a gang, event history analysis was used to determine the rate at which youths joined a gang each year, and the independent variables associated with that event. We estimated a complementary log-log model in SAS version 9.1 (Allison, 1995) using both time-fixed control variables and the time-varying predictors specified earlier. Joining a gang was the event of interest and time until the event was marked by the number of survey waves until the event occurred. Predictive variables were measured in a total of seven survey waves in the time that participants were approximately ages 10–18 (in grades 5 through 10 and again in grade 12). As mentioned earlier, gang membership was measured with both prospective and retrospective questions, resulting in ages of joining which ranged from 10 (approximately grade 5) to 19. Those who reported joining a gang at ages 17, 18, or 19 were all coded as joining a gang in the same wave (wave 7) for two reasons. First, survey data were not collected when participants were in the 11th grade, so predictive variables were not measured in that year. Second, few participants reported joining a gang at age 19. Although the interval lengths varied, because they varied in the same manner for all of the participants, this procedure is not likely to produce biased estimates (Allison, 1995). Those individuals who never reported joining a gang were assigned (0) for “gang membership” and a “duration” of (7). This modeling approach was suitable for these data as it appropriately deals with interval censoring and allows inclusion of time-varying predictors (Allison, 1995).

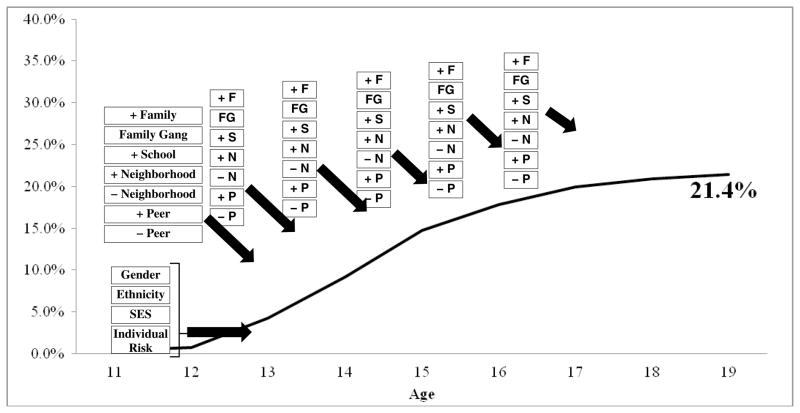

Because the onset of gang membership was measured annually and exact dates of joining a gang were not available, it was impossible to establish temporal ordering of predictors and joining a gang within each time interval (Box-Steffensmeier & Jones, 2004). Therefore, the time-varying environmental predictors were lagged one year, so that predictive factors from the previous year were used to predict joining a gang (see Fig. 1). This strategy also required that those individuals who reported joining a gang in the first wave in grade 5 (n=3) were dropped from the analysis. Including time-varying predictors in this way is an important advantage of using survival analysis as it addresses a common issue in gang research, highlighted by Thornberry, Krohn, et al. (2003): determining whether so-called risk factors are “…antecedent risk factors for gang membership, co-occurring problems, or consequences of being in a gang” (p. 57). Finally, in order to address the second and third research questions, whether the effects of predictors varied over time or by gender, interaction terms were created and included in the model.

Figure 1.

Study Design and Cumulative Gang Membership Onset.

The study employed a longitudinal assessment of the time-varying social developmental predictors of gang membership onset (21.4% by age 19). Predictors were examined using one year lags prior to onset in the following year. Sociodemographic and individual controls measured at age 10–11 were included as time-fixed covariates.

Missing data in the independent variables was addressed using multiple imputation procedures (PROC MI and MIANALYZE) to combine results from 40 imputed dataset as recommended by Graham (2009) to estimate unbiased parameters and standard errors. All of the independent variables, both the time-varying predictors and the time-fixed controls, were used in the multiple imputation model. Only the time-varying predictors had incomplete data. Across all analysis variables, respondents and time points 9.7% of the data were missing.

A subset of the SSDP sample received a preventative intervention in elementary school, consisting of individual, parent, and teacher components (see Hawkins, Catalano, Kosterman, Abbott, & Hill, 1999 for a full description of the intervention). While differences in means between the treatment and control groups have been observed on several outcomes in prior analyses, differences in the relationships between predictors and outcomes are rare. For the present analyses, to ensure that the etiological relationships between predictors and gang onset were consistent across intervention conditions (and thus could be combined into one, full sample) we examined a multiple group model testing whether the relationships between predictors and gang membership were consistent across treatment and control groups. The goodness of fit for models constraining the parameter estimates to be equal across intervention and control groups ranged from .949 to .991 (mean CFI, .976), thus, subsequent analyses were conducted on the full sample.

Results

Demographics, Early Childhood Risk, and Gang Membership

Descriptive analyses of the data show that 21.4% (n=173) of the sample self-reported joining a gang between the ages of 10 and 19 (see Fig. 1). Other studies with high-risk community samples have reported lifetime prevalences of gang membership from 14% in Denver (Huizinga & Schumann, 2001) to 30.9% in Rochester (Thornberry, Lizotte, et al., 2003).

Table 1 shows the bivariate relationships between demographic and early childhood risk factors and gang membership. The prevalence of gang membership was significantly higher among males than females. Nationwide, a disproportionate number of gang members are ethnic minorities (Glesmann, B., & Marchionna, 2009; National Youth Gang Center, 2010). The same disproportionality is reflected in the ethnic diversity in this sample. Almost 42% of the youths who joined a gang were African American (while they represent only about 26% of the sample), followed by Caucasian (29.5% who joined a gang), Asian American (19.7%), and Native American (9.2%). Finally, youth who came from families with low socioeconomic status and youth who scored higher on the individual risk index were significantly more likely to join a gang in adolescence.

Table 1.

Time-Fixed Control Variables and Gang Membership

|

|

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-gang | Gang | |||||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | |

| (n = 635) | (n = 173) | |||||||||

| Demographics | ||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||

| Race/Ethnicity*** | ||||||||||

| African American | 21.3% | 41.6% | ||||||||

| Asian American | 22.5% | 19.7% | ||||||||

| Caucasian American | 52.0% | 29.5% | ||||||||

| Native American | 4.3% | 9.2% | ||||||||

| Gender (Male)*** | 44.3% | 75.7% | ||||||||

|

|

||||||||||

| Childhood Risk | ||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||

| Socioeconomic Status (Standardized Measure)*** | 0.07 | −0.32 | ||||||||

| Individual Risk Index (Possible Total of 9)*** | 1.80 | 2.95 | ||||||||

|

|

||||||||||

p<.05;

p<.01;

p<.001

Main Effects of Time-Varying Predictors

Table 2 shows the values of the time-varying predictors at each data collection year in adolescence, comparing youth who ever joined a gang with those who never joined. Overall, those who joined a gang in adolescence scored higher on risk factors across adolescence and lower on protective factors than those who never joined. Columns 1–3 in both Tables 3 and 4 are identical, and show the zero-order relationships between predictors and gang membership (Column 1), the results from a model with only the time-varying predictors and time (Column 2), and a model with all of the time varying predictors, time, and the time-fixed controls (Column 3). The variable “time” was a measure that ranged from one to seven, representing the seven survey waves. Time was included as a control variable because the rate of gang membership onset was not steady over time. As shown in Column 1 of Table 3, each year the hazard of joining a gang increased by 1.19 times.

Table 2.

Time-Varying Predictor Values Comparing Gang and Non-Gang Across Adolescence

| Time-Varying Predictors | 5th grade | 6th grade | 7th grade | 8th grade | 9th grade | 10th grade | 12th grade |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Means(SD) and Percentages

|

|||||||

| Prosocial Family Environment | |||||||

| Gang | 0.01 (0.54) | −0.08 (0.60) | −0.09 (0.56)* | −0.11 (0.57)** | −0.10 (0.56)** | −0.17 (0.55)** | −0.21 (0.65)*** |

| Non-Gang | 0.00 (0.48) | 0.02 (0.49) | 0.02 (0.46) | 0.03 (0.45) | 0.03 (0.49) | 0.04 (0.50) | 0.04 (0.62) |

| Lived with a Gang Member | |||||||

| Gang | 9.9%*** | 8.1%*** | 13.0%*** | 14.3%*** | 13.7%*** | 14.3%*** | 13.0%*** |

| Non-Gang | 0.7% | 0.7% | 0.8% | 1.2% | 1.2% | 2.0% | 2.0% |

| School Prosocial Environment | |||||||

| Gang | −0.04 (0.52) | −0.07 (0.53) | −0.03 (0.49) | −0.01 (0.53) | −0.07 (0.54)* | −0.06 (0.56) | −0.13 (0.67)* |

| Non-Gang | 0.00 (0.43) | 0.02 (0.49) | 0.01 (0.43) | 0.00 (0.47) | 0.02 (0.50) | 0.02 (0.42) | 0.03 (0.50) |

| Neighborhood Prosocial Environment | |||||||

| Gang | −0.16 (0.91)* | −0.16 (0.91) | −0.07 (0.65) | −0.03 (0.61) | −0.16 (0.70)** | −0.13 (0.77)* | −0.11 (0.84) |

| Non-Gang | 0.04 (0.74) | 0.04 (0.87) | 0.01 (0.61) | 0.01 (0.59) | 0.04 (0.58) | 0.03 (0.71) | 0.03 (0.71) |

| Neighborhood Antisocial Environment | |||||||

| Gang | 0.24 (0.68)*** | 0.35 (0.69)*** | 0.36 (0.72)*** | 0.36 (0.63)*** | 0.44 (0.62)*** | 0.44 (0.60)*** | 0.43 (0.60)*** |

| Non-Gang | −0.06 (0.58) | −0.10 (0.65) | −0.10 (0.60) | −0.10 (0.48) | −0.11 (0.56) | −0.11 (0.56) | −0.11 (0.59) |

| Peer Prosocial Environment | |||||||

| Gang | −0.15 (0.73)** | −0.18 (0.95)* | −0.02 (0.51) | −0.03 (0.58) | −0.11 (0.77)* | −0.11 (0.78) | −0.16 (0.90)* |

| Non-Gang | 0.03 (0.56) | 0.05 (0.60) | 0.01 (0.47) | 0.00 (0.45) | 0.04 (0.60) | 0.02 (0.65) | 0.05 (0.77) |

| Peer Antisocial Environment | |||||||

| Gang | 0.19 (0.71)** | 0.18 (0.81)** | 0.30 (0.68)*** | 0.27 (0.69)*** | 0.31 (0.71)*** | 0.32 (0.67)*** | 0.35 (0.65)*** |

| Non-Gang | −0.03 (0.58) | −0.04 (0.62) | −0.08 (0.51) | −0.07 (0.54) | −0.08 (0.56) | −0.08 (0.57) | −0.08 (0.54) |

p<.05;

p<.01;

p<.001

Table 3.

Survival Analysis Results With Predictor x Time Interactions (Hazard Ratios)

| Predictors | Zero Order | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | Model 6 | Model 7 | Model 8 | Model 9 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Time-Varying Predictors

| ||||||||||

| Family prosocial env. | 0.70* | 1.15 | 1.23 | 0.93 | 1.22 | 1.23 | 1.23 | 1.24 | 1.23 | 1.24 |

| Lived with a gang member | 7.85*** | 5.81*** | 3.60*** | 3.60*** | 10.27* | 3.58*** | 3.64*** | 3.58*** | 3.59*** | 3.61*** |

| School prosocial env. | 0.64** | 0.77 | 0.81 | 0.81 | 0.82 | 0.61 | 0.81 | 0.80 | 0.81 | 0.80 |

| Neighborhood prosocial env. | 0.84 | 1.14 | 1.15 | 1.15 | 1.15 | 1.16 | 0.93 | 1.17 | 1.16 | 1.16 |

| Neighborhood antisocial env. | 2.83*** | 2.61*** | 2.41*** | 2.41*** | 2.43*** | 2.41*** | 2.46*** | 2.01* | 2.42*** | 2.42*** |

| Peer prosocial env. | 0.95 | 1.27 | 1.26 | 1.26 | 1.26 | 1.26 | 1.27 | 1.26 | 1.16 | 1.26 |

| Peer antisocial env. | 1.97*** | 1.34* | 1.34* | 1.34* | 1.32 | 1.33* | 1.33* | 1.32 | 1.33* | 1.13 |

| Time-Fixed Controls | ||||||||||

| Time (wave) | 1.19*** | 1.23*** | 1.28*** | 1.30*** | 1.31*** | 1.30*** | 1.30*** | 1.27*** | 1.29*** | 1.28*** |

| Gender (Male) | 3.22*** | 3.16*** | 3.18*** | 3.14*** | 3.16*** | 3.13*** | 3.17*** | 3.15*** | 3.15*** | |

| African American (vs. Caucasian) | 2.86*** | 1.88** | 1.87** | 1.87** | 1.86** | 1.87* | 1.86** | 1.87** | 1.88** | |

| Asian American (vs. Caucasian) | 1.43* | 1.63* | 1.62 | 1.62 | 1.62 | 1.64* | 1.64* | 1.63* | 1.65* | |

| Native American (vs. Caucasian) | 2.94*** | 1.95* | 1.98* | 1.96* | 1.97* | 1.99* | 1.93* | 1.96* | 1.95* | |

| High SES | 0.63** | 0.72** | 0.72** | 0.72** | 0.72** | 0.72** | 0.72** | 0.72** | 0.72** | |

| Individual risk index | 1.32* | 1.11* | 1.10* | 1.10* | 1.10* | 1.10* | 1.10* | 1.10* | 1.10* | |

| Interactions With Time | ||||||||||

| Prosocial family env. x time | .99 | |||||||||

| Live w/gang member x time | 8.25 | |||||||||

| School prosocial env. x time | .64 | |||||||||

| Neighborhood prosocial env. x time | .97 | |||||||||

| Neighborhood antisocial env. x time | 2.10 | |||||||||

| Peer prosocial env. x time | 1.19 | |||||||||

| Peer antisocial env. x time | 1.16 | |||||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| −2 Log Likelihooda | 1290.6 | 1204.4 | 1203.9 | 1202.9 | 1204.0 | 1203.6 | 1204.0 | 1204.2 | 1204.0 | |

p<.05;

p<.01;

p<.001

Average of 40 imputed data sets

Table 4.

Survival Analysis Results With Predictor x Gender Interactions (Hazard Ratios)

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||||

| Predictors | Zero Order | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | Model 6 | Model 7 | Model 8 | Model 9 | Model 10 |

| Time-Varying Predictors | |||||||||||

| Family prosocial env. | 0.70* | 1.15 | 1.23 | 1.14 | 1.22 | 1.23 | 1.23 | 1.24 | 1.23 | 1.26 | 1.28 |

| Lived with a gang member | 7.85*** | 5.81*** | 3.60*** | 3.59*** | 4.96** | 3.60*** | 3.57*** | 3.58*** | 3.59*** | 3.58*** | 3.63*** |

| School prosocial env. | 0.64** | 0.77 | 0.81 | 0.80 | 0.80 | 0.52* | 0.81 | 0.81 | 0.81 | 0.82 | 0.80 |

| Neighborhood prosocial env. | 0.84 | 1.14 | 1.15 | 1.15 | 1.16 | 1.14 | 1.10 | 1.16 | 1.15 | 1.14 | 1.15 |

| Neighborhood antisocial env. | 2.83*** | 2.61*** | 2.41*** | 2.42*** | 2.40*** | 2.42*** | 2.41*** | 2.79*** | 2.43*** | 2.42*** | 2.53*** |

| Peer prosocial env. | 0.95 | 1.27 | 1.26 | 1.26 | 1.26 | 1.26 | 1.26 | 1.26 | 0.96 | 1.25 | 1.25 |

| Peer antisocial env. | 1.97*** | 1.34* | 1.34* | 1.33 | 1.33* | 1.32 | 1.33* | 1.33* | 1.33* | 1.86** | 1.31 |

| Time-Fixed Controls | |||||||||||

| Time (wave) | 1.19*** | 1.23*** | 1.28*** | 1.29*** | 1.29*** | 1.29*** | 1.29*** | 1.29*** | 1.29*** | 1.29*** | 0.99 |

| Gender (Male) | 3.22*** | 3.16*** | 3.18*** | 3.27*** | 3.38*** | 3.19*** | 3.44*** | 3.22 | 3.65*** | 0.56 | |

| African American (vs. Caucasian) | 2.86*** | 1.88** | 1.87** | 1.88** | 1.83** | 1.87** | 1.86** | 1.85** | 1.83** | 1.88** | |

| Asian American (vs. Caucasian) | 1.43* | 1.63* | 1.63* | 1.62 | 1.62 | 1.63* | 1.63* | 1.63* | 1.62 | 1.66* | |

| Native American (vs. Caucasian) | 2.94*** | 1.95* | 1.96* | 1.97* | 1.95* | 1.96* | 1.97* | 1.95* | 1.97* | 1.91* | |

| High SES | 0.63** | 0.72** | 0.72** | 0.72** | 0.72** | 0.72** | 0.72** | 0.72** | 0.73** | 0.72** | |

| Individual risk index | 1.32* | 1.11* | 1.10* | 1.10* | 1.10* | 1.10* | 1.10* | 1.10* | 1.10* | 1.10* | |

| Interactions With Gender | |||||||||||

| Prosocial family env. x gender | 1.27 | ||||||||||

| Live w/gang member x gender | 3.32 | ||||||||||

| School prosocial env. x gender | 6.11 | ||||||||||

| Neighborhood prosocial env. x gender | 1.17 | ||||||||||

| Neighborhood antisocial env. x gender | 2.29 | ||||||||||

| Peer prosocial env. x gender | .32 | ||||||||||

| Peer antisocial env. x gender | 1.19 | ||||||||||

| Time x gender | 1.43** | ||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| −2 Log Likelihooda | 1290.6 | 1204.4 | 1204.3 | 1204.0 | 1201.4 | 1204.3 | 1203.8 | 1202.5 | 1200.9 | 1193.4 | |

p<.05;

p<.01;

p<.001

Average of 40 imputed data sets

Table 3 shows the results from models where we added time by predictor interactions, and Table 4 shows the results after adding gender by predictor interactions. Significant effects were observed in each environmental domain (family, school, peer and neighborhood) at the zero-order level (Column 1 of Table 3). As expected, all of the antisocial predictors (family, school, neighborhood and peer) predicted joining a gang. For example, those who lived with a gang member in the previous year had a hazard of joining a gang that was nearly eight times higher than those who did not live with a gang member. Additionally, two protective factors (prosocial family and prosocial school), significantly predicted a lower hazard of joining a gang at the zero-order level.

After controlling for the effects of time and all other time-varying predictors in the model, only living with a gang member, antisocial neighborhood, and antisocial peer environments significantly predicted joining a gang (Column 2 of Table 3). These effects remained significant after controlling for demographics and childhood risk variables (Column 3 of Table 3). Those who lived with a gang member in the previous year had a hazard of joining a gang that was more than 3.5 times higher than those who did not live with a gang member, after controlling for time, the time-fixed controls, and the time varying predictors in the model. For each unit increase in the youth’s antisocial neighborhood environment (one standard deviation), the hazard of joining a gang increased 2.4 times. Finally, for each unit increase in the youth’s antisocial peer environment (one standard deviation), the hazard of joining a gang increased 1.3 times.

Tests of Interaction with Time and Gender

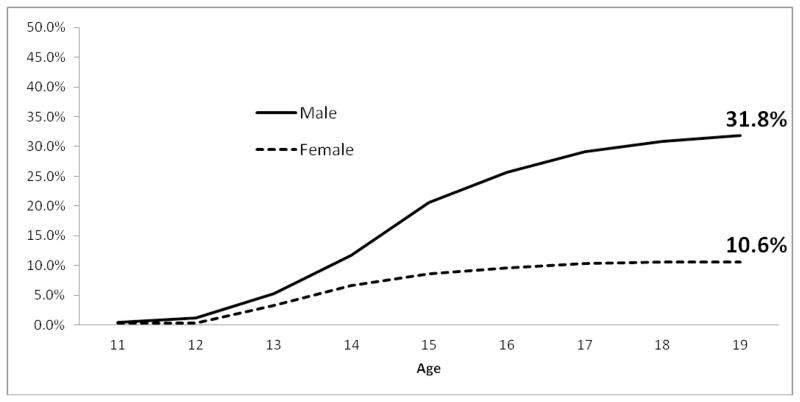

We did not find statistically significant interaction with any of the predicting variables and time, indicating that there was no evidence that the effect of these predictive variables changed over time (Columns 4–10 in Table 3). Also, we did not find significant interactions between the predictor variables and gender, indicating that the effects of the predictors did not vary by gender (Columns 4–10 in Table 4). Tables 3 and 4 show the effects of each interaction when included in the full model containing both time-varying predictors and time-fixed controls. We also tested the effects of each interaction at the zero-order level in separate models (not shown here) and found that none was statistically significant. However, we did find a significant interaction between gender and time, even when controlling for all other variables in the model. Most females who joined a gang did so by age 15. Very few females joined a gang after that age. In contrast, males in the sample continued to join gangs through age 19 (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Cumulative Onset of Gang Membership for Males and Females

Discussion

Three research questions were addressed in this paper. First, we identified three proximal (measured in the previous year) risk factors which uniquely predicted gang membership in the multivariate model. Residing with a gang member, living in a neighborhood with an antisocial environment, and association with antisocial peers in the previous year all contributed uniquely to joining a gang. Prosocial family and prosocial school environments were significantly associated with reduced gang membership in bivariate models, but dropped to non-significance in the multivariate model. This is not to say that these protective factors are unimportant, as predictors in all five developmental domains have been shown in prior research to predict gang membership in several longitudinal studies which examined risk factors in early childhood (Howell & Egley, 2005). However, an ecological understanding of development would suggest that environmental influences do not operate in isolation. Indeed, Thornberry, Krohn, et al. (2003) suggested that the interaction of risk factors in multiple domains produces the greatest risk of gang membership. For example, neighborhood disorganization may influence family functioning, and, in turn poor family functioning may influence the child’s further exposure to antisocial neighborhood influences. Furthermore, it is possible that protective influences, such as positive family and school environments, operate through factors in other domains (e.g., peer and neighborhood), and their direct effects in the present analyses were thus reduced to non-significance in the multivariate model. While this research question was beyond the scope of this paper, research shedding light on the “etiology” among environmental factors across ecological domains would be a valuable line of inquiry for future research.

Second, we did not find evidence that the effects of risk and protective factors varied with age. This result helps understand the relevance of developmental theory to adolescent gang membership, and informs where and when prevention and intervention efforts are directed. As discussed earlier, life course developmental theories assert that the effects of certain environmental domains, such as family, are theorized to be more influential earlier in development, while other influences, such as peers, are more salient later in adolescence. We did not find evidence to support these assertions with regards to joining a gang, but found that family influences continue to be important throughout adolescence (in terms of living with a gang member). This may be because, in the present study all participants who ever joined a gang did so by age 19, a period when family influences appear to still be important. Similarly, another behavior for which onset happens fully in adolescence is smoking. In a study of the onset of daily smoking, predictors including family smoking, family monitoring and family bonding continued to influence smoking onset through age 18, while family boding diminished in influence only after age 18. It is possible that the studies showing diminished influence of family environment focused on behaviors such as frequency of violence and crime which continue into adulthood when indeed family of origin influence may diminish (Tanner-Smith et al., in press).

Another possible explanation accounting for the invariant influence of risk factors for the onset of gang membership over time is the possibility that, while youths who join gangs share a similar set of risk factors as those who engage only in delinquency and violence, what distinguishes gang members is that they possess more of these factors and generally experience them in multiple developmental domains during childhood and early adolescence (Hill et al., 1999; Thornberry, Krohn, et al., 2003). These conditions may effectively cut these youths off from conventional pursuits (Papachriston, 2009; Pyrooz, Sweeten, & Piquero, in press), and maintain the stability of predictor influence across time. This chain of events underscores the importance of early prevention and intervention. However, the present results also suggest that preventive interventions even in later adolescence with family (living with a gang member), neighborhood, and peers may continue to be effective in preventing gang membership.

Interestingly, we did find a significant interaction with time and gender. In this sample, females who joined a gang generally did so by the age of 15, while males more often continued to join gangs through age 19. Intervention across family, school, neighborhood and peer domains in late childhood and early adolescence may be especially important for girls who are at risk of joining a gang.

We did not find evidence to support the hypothesis that the environmental risk and protective factors on joining a gang would vary by gender. Each environmental domain appeared to be equally significant in predicting gang membership for both boys and girls. With respect to proximal risk factors, we did not find evidence that interventions for males and females should focus on different environmental domains. Finally, regardless of what interactions were added to the model, Caucasians and those of higher SES were consistently at lower risk for joining a gang. This is consistent with a long history of research on gang membership, showing that it is a more prevalent phenomenon in lower SES and minority communities.

Regarding study limitations, it is important to note that these results were found in a high-risk sample from Seattle, Washington who experienced adolescence in the late 1980s and early 1990s. Howell (2012) cautions, “research has established that the prevalence of risk factors varies among study sites” and that reliance on findings from one longitudinal study could have “unintended consequences of overlooking important factors” (p. 124). Thus, these results should be understood within the growing body of research on gang membership. It also should be noted that these data were self-reported. It is possible that gang membership itself was under- or over-reported in this sample. However, self-report has been widely used and advocated for in research on delinquency and on gangs (Bjerregaard & Smith, 1993; Esbensen & Huizinga, 1993; Hindelang, Hirschi, & Weis, 1981; Klein, 1995; Sampson & Laub, 1992; Savitz, Rosen, & Lalli, 1980; Sullivan, 2006; Thornberry, Krohn, Lizotte, & Chard-Wierschem, 1993) and Esbensen, Peterson, Taylor, and Freng (2010) have concluded that a single-item self-identification definition of gang membership is a highly reliable indicator.

In closing, this paper sought to advance the current body of knowledge by examining and presenting the proximal and dynamic predictors of joining a gang in key environmental domains. Findings suggest that a broad intervention focus addressing family, school, peer and neighborhood environments, with a special emphasis on the influences of gang members in the youth’s family, antisocial neighborhood, and antisocial peers, may be most successful. Further, study findings suggest that similar intervention components may be equally effective for both boys and girls in preventing gang onset, and that early intervention may be particularly beneficial in preventing female gang onset.

Importantly, the finding that predictors of gang onset continued in importance throughout adolescence suggests that intervention efforts need not be lessened as youths mature, but could be equally important across adolescence, especially for boys. This implication for prevention is consistent with that drawn by the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention Study Group on Serious and Violent Juvenile Offenders (Bilchik, 1998), who concluded that it is never too early to begin prevention efforts, and it is never too late to intervene.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the anonymous reviewers as well as the editor of this special issue for their valuable comments on earlier drafts of this manuscript. We would also like to thank the members of the Seattle Social Development Project (SSDP) analysis team for their contributions that greatly strengthened the methodology of this study. Finally, we are most grateful to the participants of SSDP, whose continued participation make this research possible. This project was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA; R01DA003721, R01DA009679, R01DA024411-03-04), grant 21548 from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, and a grant from the National Institute on Mental Health (5 T32 MH20010) “Mental Health Prevention Research Training Program.”

Footnotes

The content of this paper is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the funding agencies.

Contributor Information

Amanda B. Gilman, Social Development Research Group at the University of Washington

Karl G. Hill, Social Development Research Group at the University of Washington

J. David Hawkins, Social Development Research Group at the University of Washington.

James C. Howell, National Gang Center in Tallahassee, Florida

Rick Kosterman, Social Development Research Group at the University of Washington.

References

- Allison PD. Survival analysis using SAS: A practical guide. Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Battin SR, Hill KG, Abbott RD, Catalano RF, Hawkins JD. The contribution of gang membership to delinquency beyond delinquent friends. Criminology. 1998;36(1):93–115. [Google Scholar]

- Bell KE. Gender and gangs: A quantitative comparison. Crime & Delinquency. 2009;55(3):363–387. [Google Scholar]

- Bilchik S. Juvenile Justice Bulletin. Washington, DC: Department of Justice, Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention; 1998. Serious and violent juvenile offenders. [Google Scholar]

- Bjerregaard B, Smith C. Gender differences in gang participation, delinquency, and substance use. Journal of Quantitative Criminology. 1993;9(4):329–355. [Google Scholar]

- Box-Steffensmeier JM, Jones BS. Event history modeling: A guide for social scientists. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U. The ecology of human development: Experiments by nature and design. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U. Ecological systems theory. Annals of Child Development. 1989;6:187–249. [Google Scholar]

- Catalano RF, Hawkins JD. The social development model: A theory of antisocial behavior. In: Hawkins JD, editor. Delinquency and crime: Current theories. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1996. pp. 149–197. [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Veronneau MH, Myers MW. Cascading peer dynamics underlying the progression from problem behavior to violence in early to late adolescence. Development and Psychopathology. 2010;22(3):603–619. doi: 10.1017/S0954579410000313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duran RJ. Gang life in two cities: An insider’s journey. New York: Columbia University Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Elder GH Jr, editor. Life course dynamics: Trajectories and transitions, 1968–1980. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Esbensen FA, Huizinga D. Gangs, drugs, and delinquency in a survey of urban youth. Criminology. 1993;31(4):565–589. [Google Scholar]

- Esbensen FA, Peterson D, Taylor TJ, Freng A. Similarities and differences in risk factors for violent offending and gang membership. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Criminology. 2009;42(3):310–335. [Google Scholar]

- Esbensen FA, Peterson D, Taylor TJ, Freng A. Youth violence: Sex and race differences in offending, victimization, and gang membership. Philadelphia, Pa: Temple University Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Fagan AA, Van Horn ML, Hawkins JD, Arthur MW. Gender similarities and differences in the association between risk and protective factors and self-reported serious delinquency. Prevention Science. 2007;8(2):115–124. doi: 10.1007/s11121-006-0062-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gatti U, Tremblay RE, Vitaro F, McDuff P. Youth gangs, delinquency and drug use: A test of the selection, facilitation, and enhancement hypotheses. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2005;46(11):1178–1190. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2005.00423.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glesmann CBK, Marchionna S. Focus. Oakland, CA: National Council on Crime and Delinquency; 2009. Youth in gangs: Who is at risk? [Google Scholar]

- Gordon RA, Lahey BB, Kawai E, Loeber R, Stouthamer-Loeber M, Farrington DP. Antisocial behavior and youth gang membership: Selection and socialization. Criminology. 2004;42(1):55–87. [Google Scholar]

- Gotlib IH, Wheaton B. Trajectories and turning points over the life course: Concepts and themes. In: Gotlib IH, Wheaton B, editors. Stress and adversity over the life course: Trajectories and turning points. Cambridge, U.K.; New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Graham JW. Missing data analysis: Making it work in the real world. Annual Review of Psychology. 2009;60:549–576. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins JD, Catalano RF, Kosterman R, Abbott R, Hill KG. Preventing adolescent health-risk behaviors by strengthening protection during childhood. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine. 1999;153(3):226–234. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.153.3.226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins JD, Weis JG. The social development model: An integrated approach to delinquency prevention. The Journal of Primary Prevention. 1985;6(2):73–97. doi: 10.1007/BF01325432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill KG, Howell JC, Hawkins JD, Battin Pearson SR. Childhood risk factors for adolescent gang membership: Results from the Seattle Social Development Project. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency. 1999;36(3):300–322. [Google Scholar]

- Hill KG, Lui C, Hawkins JD. Juvenile Justice Bulletin. Washington, DC: Department of Justice, Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention; 2001. Early precursors of gang membership: A study of Seattle youth. [Google Scholar]

- Hindelang MJ, Hirschi T, Weis JG. Measuring delinquency. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Howell JC. Juvenile Justice Bulletin. Washington, DC: Department of Justice, Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention; 2010. Gang prevention: An overview of current research and programs. [Google Scholar]

- Howell JC. Gangs in America’s communities. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Howell JC, Egley A. Moving risk factors into developmental theories of gang membership. Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice. 2005;3(4):334–354. [Google Scholar]

- Huizinga D, Schumann KF. Gang membership in Bremen and Denver: Comparative longitudinal data. In: Klein MW, editor. The eurogang paradox: Street gangs and youth groups in the US and Europe. Dordrecht; Boston: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 2001. pp. 231–246. [Google Scholar]

- Huizinga D, Weiher AW, Espiritu R, Esbensen FA. Delinquency and crime: Some highlights from the Denver Youth Survey. In: Thornberry TP, Krohn MD, editors. Taking stock of delinquency: An overview of findings from contemporary longitudinal studies. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers; 2003. pp. 47–91. [Google Scholar]

- Kissner J, Pyrooz DC. Self-control, differential association, and gang membership: A theoretical and empirical extension of the literature. Journal of Criminal Justice. 2009;37(5):478–487. [Google Scholar]

- Klein M. The American street gang: Its nature, prevalence, and control. New York: Oxford University Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Kroneman L, Loeber R, Hipwell AE. Is Neighborhood context differently related to externalizing problems and delinquency for girls compared with boys? Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2004;7(2):109–122. doi: 10.1023/b:ccfp.0000030288.01347.a2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacourse E, Nagin DS, Vitaro F, Cote S, Arseneault L, Tremblay RE. Prediction of early-onset deviant peer group affiliation: A 12-year longitudinal study. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2006;63(5):562–568. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.5.562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lahey BB, Gordon RA, Loeber R, Stouthamer-Loeber M, Farrington DP. Boys who join gangs: A prospective study of predictors of first gang entry. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1999;27(4):261–276. doi: 10.1023/b:jacp.0000039775.83318.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDaniel DD. Risk and protective factors associated with gang affiliation among high-risk youth: A public health approach. Injury Prevention. 2012;18(4):253–258. doi: 10.1136/injuryprev-2011-040083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore JW. Going down to the barrio: Homeboys and homegirls in change. Philadelphia: Temple University Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- National Youth Gang Center. National Youth Gang Survey Analysis. 2010 from hhtp:// www.nationalgangcenter.gov/Survey-Analysis.

- Papachriston AV. Murder by structure: Dominance relations and the social structure of gang homicide. American Journal of Sociology. 2009;115:74–128. doi: 10.1086/597791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penney SR, Lee Z, Moretti MM. Gender differences in risk factors for violence: An examination of the predictive validity of the structured assessment of violence risk in youth. Aggressive Behavior. 2010;36(6):390–404. doi: 10.1002/ab.20352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson D. Girlfriends, gun-holders, and ghetto-rats? Moving beyond narrow views of girls in gangs. In: Miller S, Leve LD, Kerig PK, editors. Delinquent girls: Contexts, relationships, and adaptation. New York: Springer; 2012. pp. 71–84. [Google Scholar]

- Pyrooz DC, Sweeten G, Piquero AR. Continuity and change in gang membership and gang embeddedness. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency in press. [Google Scholar]

- Sampson RJ, Laub JH. Crime and deviance in the life course. Annual Review of Sociology. 1992;18:63–84. [Google Scholar]

- Savitz L, Rosen L, Lalli M. Delinquency and gang membership as related to victimization. Victimology. 1980;5(2–4):152–160. [Google Scholar]

- Stoiber KC, Good B. Risk and resilience factors linked to problem behavior among urban, culturally diverse adolescents. School Psychology Review. 1998;27(3):380–397. [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan ML. Are “gang” studies dangerous? Youth violence, local context, and the problem of reification. In: Short JF, Hughes LA, editors. Studying youth gangs. Lanham, MD: AltaMira Press; 2006. pp. 15–35. [Google Scholar]

- Tanner-Smith EE, Wilson SJ, Lipsey ML. Risk factors and crime. In: Cullen FT, Wilcox P, editors. The Oxford handbook of criminological theory. Oxford: Oxford University Press; in press. [Google Scholar]

- Thornberry TP, Krohn MD, Lizotte AJ, Chard-Wierschem D. The role of juvenile gangs in facilitating delinquent behavior. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency. 1993;30(1):55–87. [Google Scholar]

- Thornberry TP, Krohn MD, Lizotte AJ, Smith C, Tobin K. Gangs and delinquency in developmental perspective. Cambridge, UK; New York, NY, USA: Cambridge University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Thornberry TP, Lizotte AJ, Krohn MD, Smith C, Porter PK. Causes and consequences of delinquency: Findings from the Rochester Youth Development Study. In: Thornberry TP, Krohn MD, editors. Taking stock of delinquency: An overview of findings from contemporary longitudinal studies. New York, NY: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers; 2003. pp. 11–46. [Google Scholar]