Abstract

Context

Although the prevalence of depression among medical interns substantially exceeds that of the general population, the specific factors responsible are not well understood. Recent reports of a moderating effect of a genetic polymorphism (5-HTTLPR) in the serotonin transporter protein gene on the likelihood that life stress will precipitate depression may help to understand the development of mood symptoms in medical interns.

Objective

To identify psychological, demographic and residency program factors that associate with depression among interns and use medical internship as a model to study the moderating effects of this polymorphism using a prospective, within-subject design that addresses the design limitations of earlier studies.

Design

Prospective cohort study

Setting

13 United States hospitals

Participants

740 interns entering participating residency programs

Main outcome measures

Subjects were assessed for depressive symptoms using the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9), a series of psychological traits and 5-HTTLPR genotype prior to internship and then assessed for depressive symptoms and potential stressors at 3-month intervals during internship.

Results

The PHQ-9 depression score increased from 2.4 prior to internship to a mean of 6.4 during internship (p<0.001). The proportion of participants who met PHQ-9 criteria for depression increased from 3.9% prior to internship to a mean of 25.7% during internship (p<0.001). A series of factors measured prior to internship (female sex, U.S. medical education, difficult early family environment, history of major depression, lower baseline depressive symptom score and higher neuroticism) and during internship (increased work hours, perceived medical errors and stressful life events) were associated with a greater increase in depressive symptoms during internship. In addition, subjects with at least one copy of a less transcribed 5-HTTLPR allele reported a greater increase in depressive symptoms under the stress of internship (p=0.002).

Conclusions

There is a marked increase in depressive symptoms during medical internship. Specific individual, internship and genetic factors are associated with the increase in depressive symptoms.

Keywords: Graduate, Medical, Education, Residency, Serotonin, Transporter

Internship is known to be a time of high stress1,2. New physicians are faced with long work hours, sleep deprivation, loss of autonomy and extreme emotional situations3. A series of cross sectional studies has examined the prevalence of significant depressive symptoms among interns. Although the proportion of interns who screen positive for major depression varied markedly across these studies (7%-49%), most studies found rates of major depression among interns to be higher than the rates found in the general population (4-5%)2,6-16.

Prospective, longitudinal studies are necessary to understand the factors underlying the development of depression among interns. Prospective studies of depression during internship to date have yielded inconsistent findings; some studies reported that factors such as female sex, neuroticism and medical errors were associated with increased depression, but other studies failed to replicate these results14,17-24. A review of these studies concluded that it is difficult to draw firm conclusions because each of the studies had significant limitations25. Most notably, the studies enrolled relatively small samples that were restricted to individual residency programs or institutions, and suffered from high attrition rates and short follow-up periods25. Further many potentially important factors, such as work hours, social support and negative life events, have not been well explored in internship depression. We report here on the largest longitudinal study to date of a sample of interns drawn from multiple institutions and specialties over a 14-month period, which aims to identify factors associated with the development of depression during internship.

Genetic epidemiological studies indicate that in addition to life stressors, genetic factors play a major role in the etiology of depression26. The gene most extensively investigated in depression is SLC6A4, which encodes the serotonin transporter protein. The serotonin transporter is a transmembrane protein located on the presynaptic membrane of serotonergic neurons. It is a major target of many common antidepressant medications such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and tricyclic antidepressants.

Caspi and colleagues27 reported an interaction between a functional promoter polymorphism at this locus (5-HTTLPR) and life stress in the development of depression. They found that among subjects who experienced no life stressors, 5-HTTLPR was not associated with depressive symptoms. As the number of stressful life events reported by subjects increased, however, subjects with at least one copy of the less transcriptionally active (low functioning) 5-HTTLPR short (S) allele reported significantly more depressive symptoms than subjects with two copies of the high functioning 5-HTTLPR long (L) allele. To date, there have been (at least) 37 follow-up studies, with some studies supporting the presence of an interaction and others not.

Two recent meta-analyses have assessed a subset of these studies and concluded that there is no evidence supporting the presence of the interaction28,29. It is important to note, however, that these meta-analyses have important limitations. First, in contrast to traditional genetic association studies, there is marked variation in study design among studies examining this interaction. Both meta-analyses were heavily weighted towards large studies in which stressful events were not well assessed, while discounting studies with more comprehensive assessments of stress that necessarily utilized smaller samples. Further, even the larger of the two meta-analyses was able to include only 14 of the 38 published studies that examined the relationship between 5-HTTLPR, stress and depression. The vast majority of the studies excluded by the meta-analysis reported that the presence of the 5-HTTLPR S allele increased the risk of depression under stress, suggesting that it is premature to draw definitive conclusions about the presence or absence of this interaction from these meta-analyses30-49.

The inconsistency among studies to date may be due in part to methodological limitations of some of these studies50. First, most of the studies assessed stressful life events and depressive symptoms retrospectively and concurrently. For some studies, subjects were asked to recall stressors and putative depressive episodes that occurred many years before the interview51,52. This is problematic because the induction of depressed mood significantly increases the recall of stressful life events53. Further, individuals with a history of depression experience more perceived life events than healthy individuals54. As a result, many of the studies to date do not adequately disentangle the cause and effect relationship between depression and reports of life stress. Additionally, most previous studies assessed a set of life stressors that were highly variable in character and intensity. Combining quantitatively and qualitatively disparate stressors may act to increase the “noise” of a study, reducing the statistical power to detect interaction effects.

Some studies have attempted to avoid the problems of impaired recall and variable stressors by focusing on specific populations that have experienced a substantial, uniform stressor such as stroke or myocardial infarction39-48. However, because these “specific stressor” studies assess subjects only after the onset of the stressor, they cannot determine whether the depression was present before the onset of the stressor or whether the depression played a role in precipitating the stressor. Although one could study this question prospectively, with depression measured in the same subjects before and after the onset of a uniform stressor, it is generally not possible to predict the occurrence of a stressor. Medical internship provides a rare instance in which the onset of a major stressor can be predicted for a defined population. The present study seeks to identify the factors important in the development of depression during medical internship and to utilize internship as a stress model to study subjects before and after the onset of a major stressor and assess the moderating effect of 5-HTTLPR on the development of depression.

Methods

Participants

1394 interns entering traditional and primary care internal medicine, general surgery, pediatrics, obstetrics/gynecology, and psychiatry residency programs during the 2007-2008 and 2008-2009 academic years were sent an email two months prior to commencing internship and invited to participate in the study. For 123 subjects, our email invitations were returned as undeliverable and we were unable to obtain a valid email address. 58% (740/1271) of the remaining invited subjects agreed to participate in the study. The Institutional Review Board at Yale University and the participating hospitals approved the study. Subjects were given $30 (2007-2008 cohort) or $40 (2008-2009 cohort) gift certificates to participate in the study.

Data Collection

All surveys were conducted through a secure online website designed to maintain confidentiality, with subjects identified only by numbers. No links between the identification number and the subjects' identities were maintained.

Depressive symptoms were measured using the depression module of the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9)55. The PHQ-9 is a self-report component of the PRIME-MD inventory designed to screen for depressive symptoms. For each of the 9 depressive symptoms, interns indicated whether, during the previous 2 weeks, the symptom had bothered them “not at all,” “several days,” “more than half the days,” or “nearly every day.” Each item yields a score of 0 to 3, so that the PHQ-9 total score ranges from 0 to 27. PHQ scores of 10 or greater, 15 or greater and 20 or greater correspond to moderate, moderately severe and severe depression respectively56. A score of 10 or greater on the PHQ-9 has a sensitivity of 93% and a specificity of 88% for the diagnosis of MDD56. Diagnostic validity of the PHQ-9 is comparable to clinician-administered assessments55.

Initial Assessment

Subjects completed a baseline survey 1-2 months prior to commencing internship that asked about general demographic factors (age, sex, ethnicity, marital status), medical education factors (American or foreign medical school, medical specialty), personal factors (baseline PHQ-9 depressive symptoms, self-reported history of depression) and the following psychological measures: 1) Neuroticism (NEO-Five Factor Inventory57) 2) Resilience (Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale58) 3) Perceived Stress (Perceived Stress Scale59) 4) Social Supports (Sarason Social Support Questionnaire60) 5) Early Family Environment (Risky Families Questionnaire61) and 6) Cognitive Styles (modified Sociotropy-Autonomy Scale62).

Within-Internship Assessments

Participants were contacted via email at months 3, 6, 9 and 12 of their internship year and asked to complete the PHQ-9. They were also queried regarding their rotation setting, perceived medical errors, work hours and sleep over the past week and the occurrence of a series of non-internship life stress (serious illness, death or serious illness in close family or friend, financial problems, end of serious relationship, and becoming a victim of crime or domestic violence) during the past three months.

DNA Collection

Subjects choosing to take part in the study were given the option to submit a saliva sample for DNA extraction. We used the Oragene salivary DNA self-collection kit63, which allows for subjects to submit a salivary sample by mail without direct contact with study personnel.

Serotonin Transporter Genotyping

The serotonin transporter 5-HTTLPR variant was genotyped using previously described PCR conditions and primers64. An A→G single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) has been identified within the 5-HTTLPR repeat region (rs25531)65. Functional studies have shown that promoter regions with the 16-repeat variant and the “G” allele (LG) were functionally equivalent to the low functioning 14 repeat variant (S allele). To genotype the additional SNP that occurs in the VNTR repeat region of the SLC6A4 promoter65, we used a restriction enzyme assay described previously66.

Statistical Analysis

All analyses were performed using SPSS 16.0 (Chicago, IL). The point prevalence of depressive symptoms and a positive screen for depression during internship were determined through analysis of PHQ-9 depressive symptom scores at the 3, 6, 9 and 12-month assessments. To investigate whether there was a significant change in depressive symptoms during the internship year, we compared baseline PHQ-9 depressive symptoms and depressive symptoms at the 3, 6, 9 and 12-month assessments through a series of paired t-tests.

Baseline Factors

The association between variables measured at baseline and the development of depressive symptoms during internship was assessed through a two-step process. Using Pearson correlations for continuous measures and chi-square analyses for nominal measures, we identified baseline demographic variables that were associated with the mean change in depressive symptoms from baseline to the quarterly assessments during internship (PHQ-9(change) = mean PHQ-9 depressive symptoms(3-, 6-, 9- and 12-month assessments) – PHQ-9 depressive symptoms(baseline)). Significant variables were subsequently entered into a stepwise linear regression model to identify significant predictors while accounting for collinearity among variables.

Within-Internship Factors

The association between variables measured through recurring assessments during internship (within-internship variables) and change in depressive symptoms were assessed through generalized estimating equation (GEE) analysis to account for correlated repeated measures within subjects. Internship variables (work hours, occurrence of medical errors, hours of sleep, non-internship stressful life events) were incorporated as predictor variables and associated baseline factors were used as covariates. We utilized concurrently measured depressive symptoms as the outcome variable (i.e. 3-month depressive symptoms was indexed to the 3-month within-internship variable, 6-month depressive symptoms indexed to 6-month medical errors etc.).

Next, to gain insight into the direction of causality between associated within-internship factors and depressive symptoms, we assessed whether depressive symptom score prior to internship predicted increased levels of the associated within-internship variables at 3 months. For this analysis, we used a general linear model, with the associated within-internship measure as the dependent variable and baseline depressive symptom score as the independent variable. Baseline factors associated with increased depressive symptoms were included as covariates. Finally, for the variables for which baseline depressive symptom score predicted increased levels of the associated within-internship variables at 3 months, we tested whether the 3-month depressive symptom score was associated with the relevant within-internship factor after controlling for baseline depressive symptoms. Thus, 3-month depressive symptom scores were reintroduced into the general linear model as an independent variable in the analysis.

Serotonin Transporter Polymorphism

Because there are substantial racial/ethnic differences in 5-HTTLPR allele frequencies (S allele frequency: Caucasian–0.44; African–0.11; Chinese– 0.70)64, we performed separate analyses for individual racial/ethnic groups to minimize the chance of false association due to the presence of population stratification67. To explore the effects of 5-HTTLPR and stress on the emergence of depressive symptoms, we performed a GEE analysis with the presence of a 5-HTTLPR low functioning allele (S or LG) as the grouping variable and change in depressive symptoms as the outcome variable. To gain insight into the specific factors that moderate a potential genotype effect on depressive symptoms, we introduced the baseline and within-internship factors that had significant main effects on this outcome measure in the previous analysis and the corresponding genotype × factor interaction terms as predictor variables into the GEE analysis.

Results

Individuals who chose to take part in the study were younger (27.9 years old vs. 28.4 years old; p<0.001) and more likely to be female (54.4% vs. 52.5%; p<0.001) than individuals that chose not to participate (Table 1) (Supplemental Tables 1-4). 88% (651 of 740) of subjects completed at least one follow-up survey with a mean of 69% of subjects responding to each of the four follow-up surveys.

Table 1. Sample Demographic Characteristics.

This table provides Beta and SEM values from a stepwise linear regression for baseline factors and Wald Chi Square values from a generalized estimating equation (GEE) analysis for within-internship factors.

| Variable | No (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | Male | 337 (45.6) |

| Female | 403 (54.4) | |

| Age | ≤25 | 101 (13.6) |

| 26-30 | 533 (72.1) | |

| 31-35 | 84 (11.3) | |

| >35 | 22 (3.0) | |

| Specialty | Internal Medicine | 358 (48.5) |

| General Surgery | 98 (13.3) | |

| OB/Gyn | 42 (5.7) | |

| Pediatrics | 94 (12.7) | |

| Psychiatry | 63 (8.5) | |

| Emergency Medicine | 47 (6.3) | |

| Med/Peds | 19 (2.6) | |

| Family Medicine | 19 (2.6) | |

| Relationship Status | Single | 79 (64.7) |

| Married | 248 (33.5) | |

| Divorced | 13 (1.7) | |

Prevalence of Depressive Symptoms

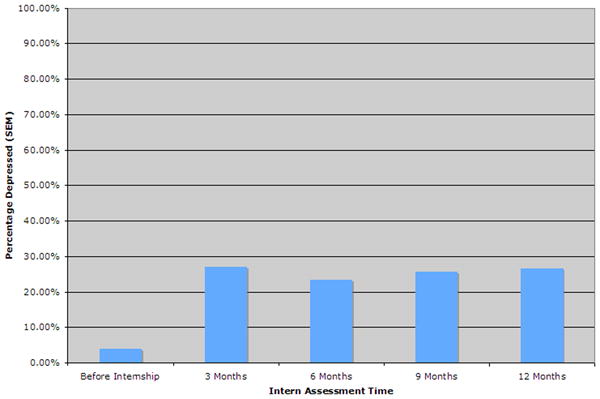

The mean PHQ-9 depressive symptom score reported by subjects increased significantly from baseline (mean±SD) (2.38±2.99) to 3 months (6.70±5.37; p<0.001), 6 months (6.33±4.98; p<0.001), 9 months (6.48±4.98; p<0.001) and 12 months (6.26±5.10; p<0.001) of internship. Using the criteria for major depression developed by Kroenke et al56 (PHQ>10) the percentage of subjects meeting this diagnosis increased from 3.9% at baseline to 27.1%, 23.3%, 25.7% and 26.6% at the 3, 6, 9 and 12-month time points of internship, respectively (Figure 1). 41.8% of subjects met criteria for major depression at one or more quarterly assessments. On sensitivity analysis, assuming that all nonresponders did not experience a depressive episode during internship, the prevalence of a depressive episode during internship would be 19.5% (272/1394). The percentage of subjects meeting criteria for moderately severe depression (PHQ>15) increased from 0.7% at baseline to 6.6%, 6.2%, 7.8% and 7.6% at the 3, 6, 9 and 12-month time points of internship, respectively. Similarly, the percentage of subjects meeting criteria for severe depression (PHQ>20) increased from 0% at baseline to 2.3%, 1.6%, 1.8% and 0.8% at the 3, 6, 9 and 12-month time points of internship, respectively.

Figure 1.

This figure demonstrates the proportion of interns who meet PHQ criteria for depression54 prior to internship and at 3-month intervals through intern year.

To determine whether the increase in overall PHQ-9 score was due to an increase in all depressive symptoms or only a subset, we assessed the change from baseline to mean internship level individually for each of the PHQ-9 symptoms. Subjects reported a significant increase (p<0.001) for all nine items). The increase in mean symptom score ranged from 70% (difficulty sleeping) to 370% (thoughts of death).

Baseline Factors

Among 15 baseline variables tested, nine were significantly correlated with a change in depressive symptoms from the baseline assessment to the mean of the four internship assessments (Female sex: r=0.147, p<0.001; European-American ethnicity: r=0.084, p=0.036; Personal history of depression: r=0.206, p<0.001; Lower baseline depressive symptoms: r=0.126, p=0.002; U.S medical education: r=0.115, p=0.004; Higher neuroticism: r=0.115, p <0.001; Difficult early family environment: r=0.108, p<0.001; Higher perceived stress: r=0.094, p=0.020; Higher sociotropy: r=0.116, p=0.004). When these nine variables were entered into the stepwise linear regression to account for collinearity between variables, six variables remained significant (Neuroticism: β=0.24, p<0.001; Personal history of depression: β=0.17, p<0.001; Lower baseline depressive symptoms: β=0.38, p<0.001; Female sex: β=0.08, p=0.031; U.S. medical education: β=0.10, p=0.005; Difficult early family environment: β=0.08, p=0.035).

Within-Internship Factors

We used a GEE analysis to assess factors during internship that were associated with a change in depressive symptoms while controlling for repeated measurements. Three within-internship variables were associated with an increase in depressive symptoms (Work hours: Wald Chi Square(99)=2.8×1011, p<0.001; Reported medical errors: Wald Chi Square(1)=16.2, p<0.001); Non-internship stressful life events: Wald Chi Square(5)=71.6, p <0.001;. There were no significant gender interactions for any of the associated baseline or within-internship factors (data not shown).

To gain insight into the direction of the association of within-internship factors and depression, we assessed whether baseline depressive symptoms predicted an increased level of the within-internship factor at the 3-month internship assessment. Baseline depressive symptom score predicted reported medical errors at 3 months (F(21)=2.201 p=0.002), but not work hours (F(21)=1.116 p>0.05) or non-internship stressful life events (F(21) = 1.029 p>0.05) at 3 months. For the reported medical errors analysis, re-introduction of the 3-month depressive symptom score showed it to be a significant predictor of medical errors at 3 months even in the presence of baseline depressive symptoms (F(27)=1.676 p=0.004).

Serotonin Transporter Genotype

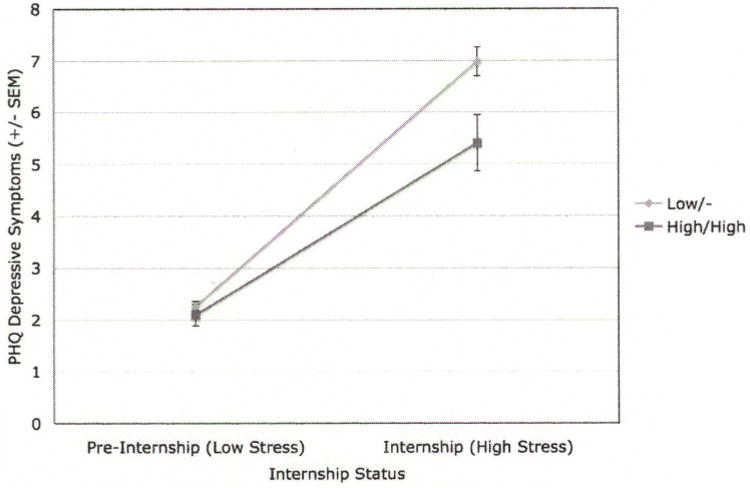

A total of 409/652 (63%) of eligible subjects provided saliva samples. There were no significant differences on sex, age or ethnicity between subjects that provided a sample and those that did not. For both major racial/ethnic groups in our sample (European-American and Asian), allele frequencies were consistent with previous reports and Hardy-Weinberg Equilibrium (data not shown). Among European-Americans, subjects with at least one low functioning 5-HTTLPR (S or LG) allele reported a significantly greater increase in depressive symptoms than subjects with two high functioning 5-HTTLPR (LA) alleles Wald Chi Square(1)=8.2, p=0.004 (Figure 2). The percentage of European-American subjects with at least one low functioning 5-HTTLPR allele who met criteria for depression increased from 2.4% before internship to 42.5% at its highest during internship, while the percentage of European-American subjects with two high functioning 5-HTTLPR alleles who met criteria for depression increased from 5.1% before internship to 36.2% at its highest during internship.

Figure 2.

This figure displays PHQ depression scores for Caucasian subjects stratified by the presence of at least one copy of a 5-HTTLPR low functioning allele. The left side of the figure shows the PHQ depression score prior to the stress of internship. The right side of the figure shows the mean PHQ depression score during internship.

To identify variables that moderate the relationship between 5-HTTLPR and depressive symptoms, we introduced the main effect and interaction terms consisting of genotype and each of the baseline and within-internship variables that were significantly associated with an increase in depressive symptoms into the 5-HTTLPR GEE analysis. Among baseline variable, there was a significant interaction of 5-HTTLPR with neuroticism (Wald Chi Square(19)=30.6 p=0.045) but the interactions of 5-HTTLPR with the other five baseline variables were not significant. Among within-internship variables, there was a significant interaction of 5-HTTLPR with work hours (Wald Chi Square(61)=5757.3, p<0.001) but the interactions of 5-HTTLPR with non-internship stressful life events and reported medical errors were not significant. Among Asian subjects, there was no difference in the change in depressive symptoms between genotype groups (t=1.06; p>0.05).

Comment

In this study, we found that the rate of depression increased dramatically during the internship year, from 3.9% of subjects meeting PHQ-9 criteria for depression before internship to an average of 25.3% of subjects meeting criteria at quarterly assessments during the internship year. The majority of subjects who met criteria for depression were classified as moderately depressed, with few subjects meeting PHQ-9 criteria for moderately severe or severe depression. Because the development of major depression has been linked to higher risk for future depressive episodes and greater long-term morbidity risk68,69, future studies should examine how the rate of depression changes as training physicians progress through their careers beyond internship and the possible effects of depression on the general health of physicians.

Beyond assessing depression prevalence, we also identified a series of factors associated with the development of depressive symptoms during internship. The baseline factors that were associated with the development of depression in this study include some that have been implicated in prior residency studies (female sex, difficult early family environment, neuroticism and a prior history of depression) and other factors not previously identified (U.S. medical education and lower baseline depressive symptoms). It is also interesting to note that a number of factors, such as medical specialty and age, were not associated with the development of depression. With effective interventions to help prevent the onset of depression now available, the predictive factors identified here could allow at-risk interns to take steps before the onset of symptoms to lower their chances of developing depression70.

As with baseline factors, we identified within-internship factors that were previously implicated, as well as novel factors associated with the development of depression. Our finding that medical errors are associated with depression supports the findings of two recent studies71,72. Here we extend the association identified in prior studies by demonstrating that depressive symptoms present before internship predicted reported errors during internship, indicating that depression results in increased medical errors. Controlling for the baseline level of depressive symptoms, a strong correlation between errors and depression persisted, indicating that errors may also cause depression and that the relationship between depression and reported medical errors is bi-directional.

In addition to building on previous work exploring the relationship between medical errors and depression, this is the first study to demonstrate a direct association between the number of hours worked and risk of depression in medical interns. In contrast to our finding with medical errors, we found no evidence that depressive symptom score before internship predicted work hours during internship. These findings suggest that the association between work hours and depression during internship is due to increased work hours leading to increased depressive symptoms during internship. Future studies could explore whether systemic changes designed to improve patient safety, such as additional safeguards against medical errors and further resident work hour restrictions, reduce the development of depression among interns.

There are a number of limitations to our findings related to depressive symptoms and internship. First, our finding that the association between depressive symptoms and reported medical errors persisted when controlling for pre-existing depressive symptoms does not definitively prove that errors led to depression. It is possible that some third factor differentially promoted depression in a subset of the sample and also led to an increase in the reported within internship factor in that group of residents. Though no variable that we measured (gender, age, specialty or institution) appeared to account for this effect, it is possible that an unmeasured variable could have caused the effect.

Second, only 58% of invited individuals chose to participate in the study. Although there were only modest differences in age and gender between those who chose to take part in the study and those who did not, our results should be extrapolated with caution.

Third, although multiple studies have demonstrated the validity, sensitivity and specificity of the PHQ-9 inventory, it is important to note that we assessed depression through a self-report inventory rather than a diagnostic interview.

Fourth, we assessed medical errors through self-report rather than through objective measurement leading to the possibility that we did not accurately capture the occurrence of medical errors. For instance, the established tendency of depressed individuals towards enhanced memory of emotionally negative events may have resulted in depressed residents recalling more errors rather than actually committing more errors26. Previous studies however, have demonstrated that resident self-report of errors can act as a reasonable proxy for errors assessed through chart review and that self-report was actually more effective in detecting preventable errors73,74.

Finally, our study was restricted to interns and thus our results may not hold for advanced residents or physicians who have completed their training. In addition, although we did not find significant differences in results among hospitals or specialties, the interns and programs included here may not be representative of the country in general.

Serotonin Transporter, Stress and Depressive Symptoms

In addition to identifying factors associated with the development of depression during internship, we also used internship as a model to explore the relationship between a serotonin transporter promoter polymorphism and stress in the development of depression. We found evidence that this variant moderates the response to stress in European-American subjects, with subjects carrying at least one low functioning 5-HTTLPR allele reporting a 43% greater increase in depressive symptoms than subjects with two low functioning alleles. Consistent with an earlier study exploring the 5-HTTLPR × stress interaction in the context of personality traits, we found that the relationship between 5-HTTLPR and the development of depressive symptoms under stress was moderated by neuroticism34. Further, in exploring the type of stress for which 5-HTTLPR affects sensitivity, we found evidence supporting an interaction of 5-HTTLPR with work hours, but not with medical errors or stressful life events. This finding supports the results of a prior study in which the 5-HTTLPR × stress interaction effect on depressive symptoms was the result of increased sensitivity to common, mild stressors among individuals carrying the low functioning allele, rather than an increased sensitivity to rare and severe life events33. The relationship between 5-HTTLPR, stress and depression has not been well studied in Asian populations. In our sample, there was no evidence that 5-HTTLPR genotype influenced the change in depression score among subjects of Asian ethnicity.

The results of our study support the original study that demonstrated a relationship between 5-HTTLPR, stress and depression risk27 but conflict with the results of some other studies and two recent meta-analyses. It is possible that no actual interaction exists and the results of our study, along with the other studies reporting a significant interaction, are false positives. However, because the approaches used in studies exploring the interaction vary substantially, an alternate explanation for our findings is that a true, but modest gene × environment interaction effect exists, but that certain study design features are necessary to detect the effect75. Our study illustrates a number of features that may be important to maximize the power to detect gene × environment interaction effects. First, we used a stressor that has a substantial direct effect on depression. This is in contrast to many of the negative studies exploring this interaction that assessed a set of life stressors that were highly variable in character and intensity. Second, by utilizing a prospective design, we minimized the biases inherent in the retrospective and concurrent assessment of stress and depressive symptoms present in other studies.

It is interesting to note that eight of the ten previous studies that avoided the problems of impaired recall and variable stressors by utilizing a “specific stressor” approach have reported an association between the 5-HTTLPR S allele and increased depression under stress39-48. Here we extend the results of that “specific stressor” group of studies by assessing the same subjects, before and after the onset of the stressor. This allowed us to avoid the confounding attributable to differences between subjects that are inherent in case-control studies and demonstrate that the association between genotype and depressive symptoms was not present before the onset of the stressor. Last, we maximized the genetic information obtained from the locus of interest by genotyping the functional SNP within the 5-HTTLPR locus and functionally classifying the low functioning LG allele with the low functioning S allele. The functional misclassification of alleles in some previous studies may also have reduced the power to detect interaction effects.

Overall Significance

In summary, we conducted the largest prospective study to date of depression during medical internship. We identified a high level of depressive symptoms among interns and a series of baseline and within-internship factors that associated with increased depressive symptoms in this population. Subsequent studies that more fully explore the consequences of depression among interns both on patients and the physicians-in-training themselves are needed. In this study we also utilized internship to model the relationship between 5-HTTLPR, stress and depression and found that the 5-HTTLPR low functioning allele was associated with a significantly greater increase in depressive symptoms under stress. Our study highlights the striking variation in experimental design among studies of this interaction and the impact on the findings of these different designs. In the future, meta-analyses exploring the relationship between 5-HTTLPR, stress and depression should account for this variation in study design and systematically assess whether heterogeneity of study design predicts with the estimated overall effect.

Supplementary Material

Table 2. Predictors of Increased Depressive Symptoms.

| Baseline Factors | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Factor | Beta | SEM | P value |

| Neuroticism | 0.24 | 0.021 | <0.001 |

| Personal History of Depression | 0.17 | 0.024 | <0.001 |

| Baseline Depressive Symptoms | -0.38 | 0.064 | <0.001 |

| Female Sex | 0.08 | 0.311 | 0.031 |

| US Medical Graduate | 0.10 | 0.412 | 0.005 |

| Difficult Early Family Environment | 0.08 | 0.016 | 0.035 |

| Within-Internship Factors | ||

|---|---|---|

| Factor | Wald Chi Square (df) | P value |

| Mean Work Hours | 2.8 × 10-11 (99) | <0.001 |

| Medical Errors | 16.2 (1) | <0.001 |

| Stressful Life Events | 71.6 (1) | <0.001 |

Table 3. Serotonin Transporter Functional Genotype and Change in Depressive Symptoms During Medical Internship.

| Ethnicity | 5-HTTLPR functional genotype | N | Mean | SEM | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| European-American | High/High | 58 | 3.33 | 0.35 | 0.004 |

| High/Low | 141 | 4.69 | 0.35 | ||

| Low/Low | 69 | 4.95 | 0.54 | ||

|

| |||||

| Asian | High/High | 7 | 6.4 | 1.75 | - |

| High/Low | 14 | 2.77 | 0.93 | ||

| Low/Low | 63 | 3.45 | 0.46 | ||

|

| |||||

| Other | High/High | 13 | 5.11 | 1.23 | - |

| High/Low | 25 | 3.15 | 0.75 | ||

| Low/Low | 19 | 6.16 | 1.21 | ||

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a Donaghue Foundation Clinical and Community Grant, an APA SAMHSA Grant and a VA REAP grant. The funding sources played no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

The authors would like to thank Sobia Sarmast and Michelle Streckenbach for technical support and the participating residents and program directors for the time that they invested in this study. We would also like to that the American Medical Association for providing demographic information about participating residency programs. Srijan Sen had full access to all of the data in the study and conducted the statistical analyses. He takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Footnotes

Competing Interests: SS, HS, GC, JG and CG declare that the answers to the questions on your competing interest form are no competing interests and therefore have nothing to declare. HK reports consulting arrangements with Alkermes, Inc., Ortho-McNeil Pharmaceuticals, Elbion Pharmaceuticals, Solvay Pharmaceuticals, and Sanofi-Aventis Pharmaceuticals and research support from Merck and Merck Company, Bristol-Myers Squibb Company and Ortho-McNeil Pharmaceuticals. JK reports consulting arrangements with Abbott Laboratories, Astra-Zeneca, Atlas Venture, Bristol-Meyers Squibb, Cypress Bioscience, Inc., Eli Lilly and Co., Fidelity Biosciences, Forest Laboratories, Glaxo-SmithKline, Houston Pharma, Lohocla Research Corporation, Merz Pharmaceuticals, Organon Pharmaceuticals, Pfizer Pharmaceuticals, Schering Plough Research Institute, Shire Pharmaceuticals, Sumitomo Pharmaceuticals America, Ltd., Takeda Industries, Transcept Pharmaceutical, UCB Pharma, US Micron, Tetragenex Pharmaceuticals (compensation in exercisable warrant options until March 21, 2012; value less than $10K) is co-sponsor on pending patents related to 1) glutamatergic agents for psychiatric disorders (depression, OCD) and antidepressant effects of oral ketamine.

Ethical approval: The study was approved by the institutional review boards of Yale University and participating institutions.

References

- 1.Duffy TP. Glory days. What price glory? Pharos Alpha Omega Alpha Honor Med Soc. 2005 Autumn;68(4):22–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Butterfield PS. The stress of residency. A review of the literature. Arch Intern Med. 1988 Jun;148(6):1428–1435. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shanafelt T, Habermann T. Medical residents' emotional well-being. JAMA. 2002 Oct 16;288(15):1846–1847. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.15.1846. author reply 1847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cryan JF, Mombereau C. In search of a depressed mouse: utility of models for studying depression-related behavior in genetically modified mice. Mol Psychiatry. 2004 Apr;9(4):326–357. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kendler KS, Hettema JM, Butera F, Gardner CO, Prescott CA. Life event dimensions of loss, humiliation, entrapment, and danger in the prediction of onsets of major depression and generalized anxiety. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003 Aug;60(8):789–796. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.8.789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kash KM, Holland JC, Breitbart W, et al. Stress and burnout in oncology. Oncology (Williston Park) 2000 Nov;14(11):1621–1633. discussion 1633-1624, 1636-1627. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Murphy JM, Laird NM, Monson RR, Sobol AM, Leighton AH. A 40-year perspective on the prevalence of depression: the Stirling County Study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2000 Mar;57(3):209–215. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.57.3.209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hsu K, Marshall V. Prevalence of depression and distress in a large sample of Canadian residents, interns, and fellows. Am J Psychiatry. 1987 Dec;144(12):1561–1566. doi: 10.1176/ajp.144.12.1561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bellini LM, Baime M, Shea JA. Variation of mood and empathy during internship. JAMA. 2002 Jun 19;287(23):3143–3146. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.23.3143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schneider SE, Phillips WM. Depression and anxiety in medical, surgical, and pediatric interns. Psychol Rep. 1993 Jun;72(3 Pt 2):1145–1146. doi: 10.2466/pr0.1993.72.3c.1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kirsling RA, Kochar MS, Chan CH. An evaluation of mood states among first-year residents. Psychol Rep. 1989 Oct;65(2):355–366. doi: 10.2466/pr0.1989.65.2.355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Archer LR, Keever RR, Gordon RA, Archer RP. The relationship between residents' characteristics, their stress experiences, and their psychosocial adjustment at one medical school. Acad Med. 1991 May;66(5):301–303. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199105000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hendrie HC, Clair DK, Brittain HM, Fadul PE. A study of anxiety/depressive symptoms of medical students, house staff, and their spouses/partners. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1990 Mar;178(3):204–207. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199003000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reuben DB. Depressive symptoms in medical house officers. Effects of level of training and work rotation. Arch Intern Med. 1985 Feb;145(2):286–288. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shanafelt TD, Bradley KA, Wipf JE, Back AL. Burnout and self-reported patient care in an internal medicine residency program. Ann Intern Med. 2002 Mar 5;136(5):358–367. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-136-5-200203050-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Michels PJ, Probst JC, Godenick MT, Palesch Y. Anxiety and anger among family practice residents: a South Carolina family practice research consortium study. Acad Med. 2003 Jan;78(1):69–79. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200301000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Clark DC, Salazar-Grueso E, Grabler P, Fawcett J. Predictors of depression during the first 6 months of internship. Am J Psychiatry. 1984 Sep;141(9):1095–1098. doi: 10.1176/ajp.141.9.1095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Girard DE, Elliot DL, Hickam DH, et al. The internship--a prospective investigation of emotions and attitudes. West J Med. 1986 Jan;144(1):93–98. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Firth-Cozens J. Emotional distress in junior house officers. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1987 Aug 29;295(6597):533–536. doi: 10.1136/bmj.295.6597.533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Baldwin PJ, Dodd M, Wrate RM. Young doctors' health--II. Health and health behaviour. Soc Sci Med. 1997 Jul;45(1):41–44. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(96)00307-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Williams S, Dale J, Glucksman E, Wellesley A. Senior house officers' work related stressors, psychological distress, and confidence in performing clinical tasks in accident and emergency: a questionnaire study. BMJ. 1997 Mar 8;314(7082):713–718. doi: 10.1136/bmj.314.7082.713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hainer BL, Palesch Y. Symptoms of depression in residents: a South Carolina Family Practice Research Consortium study. Acad Med Dec. 1998;73(12):1305–1310. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199812000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tyssen R, Vaglum P, Gronvold NT, Ekeberg O. The impact of job stress and working conditions on mental health problems among junior house officers. A nationwide Norwegian prospective cohort study. Med Educ. 2000 May;34(5):374–384. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2923.2000.00540.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tyssen R, Vaglum P, Gronvold NT, Ekeberg O. Factors in medical school that predict postgraduate mental health problems in need of treatment. A nationwide and longitudinal study. Med Educ Feb. 2001;35(2):110–120. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2923.2001.00770.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tyssen R, Vaglum P. Mental health problems among young doctors: an updated review of prospective studies. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2002 May-Jun;10(3):154–165. doi: 10.1080/10673220216218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kendler KS, Neale MC, Kessler RC, Heath AC, Eaves LJ. A longitudinal twin study of personality and major depression in women. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1993;50(11):853–862. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1993.01820230023002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Caspi A, Sugden K, Moffitt TE, et al. Influence of life stress on depression: moderation by a polymorphism in the 5-HTT gene. Science. 2003 Jul 18;301(5631):386–389. doi: 10.1126/science.1083968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Munafo MR, Durrant C, Lewis G, Flint J. Gene × Environment Interactions at the Serotonin Transporter Locus. Biol Psychiatry. 2008 Aug 6; doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Risch N, Herrell R, Lehner T, et al. Interaction between the serotonin transporter gene (5-HTTLPR), stressful life events, and risk of depression: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2009 Jun 17;301(23):2462–2471. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Scheid JM, Holzman CB, Jones N, et al. Depressive symptoms in mid-pregnancy, lifetime stressors and the 5-HTTLPR genotype. Genes Brain Behav. 2007 Jul;6(5):453–464. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2006.00272.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kaufman J, Yang BZ, Douglas-Palumberi H, et al. Social supports and serotonin transporter gene moderate depression in maltreated children. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004 Dec 7;101(49):17316–17321. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404376101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kaufman J, Yang BZ, Douglas-Palumberi H, et al. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor-5-HTTLPR gene interactions and environmental modifiers of depression in children. Biol Psychiatry. 2006 Apr 15;59(8):673–680. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kendler KS, Kuhn JW, Vittum J, Prescott CA, Riley B. The interaction of stressful life events and a serotonin transporter polymorphism in the prediction of episodes of major depression: a replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005 May;62(5):529–535. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.5.529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jacobs N, Kenis G, Peeters F, Derom C, Vlietinck R, van Os J. Stress-related negative affectivity and genetically altered serotonin transporter function: evidence of synergism in shaping risk of depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006 Sep;63(9):989–996. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.9.989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sjoberg RL, Nilsson KW, Nordquist N, et al. Development of depression: sex and the interaction between environment and a promoter polymorphism of the serotonin transporter gene. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2006 Aug;9(4):443–449. doi: 10.1017/S1461145705005936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cicchetti D, Rogosch FA, Sturge-Apple ML. Interactions of child maltreatment and serotonin transporter and monoamine oxidase A polymorphisms: depressive symptomatology among adolescents from low socioeconomic status backgrounds. Dev Psychopathol. 2007 Fall;19(4):1161–1180. doi: 10.1017/S0954579407000600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Aguilera M, Arias B, Wichers M, et al. Early adversity and 5-HTT/BDNF genes: new evidence of gene-environment interactions on depressive symptoms in a general population. Psychol Med. 2009 Feb 12;:1–8. doi: 10.1017/S0033291709005248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stein MB, Schork NJ, Gelernter J. Gene-by-environment (serotonin transporter and childhood maltreatment) interaction for anxiety sensitivity, an intermediate phenotype for anxiety disorders. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008 Jan;33(2):312–319. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kim JM, Stewart R, Kim SW, Yang SJ, Shin IS, Yoon JS. Modification by two genes of associations between general somatic health and incident depressive syndrome in older people. Psychosom Med. 2009 Apr;71(3):286–291. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181990fff. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kohen R, Cain KC, Mitchell PH, et al. Association of serotonin transporter gene polymorphisms with poststroke depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008 Nov;65(11):1296–1302. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.65.11.1296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lenze EJ, Munin MC, Ferrell RE, et al. Association of the serotonin transporter gene-linked polymorphic region (5-HTTLPR) genotype with depression in elderly persons after hip fracture. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2005 May;13(5):428–432. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajgp.13.5.428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nakatani D, Sato H, Sakata Y, et al. Influence of serotonin transporter gene polymorphism on depressive symptoms and new cardiac events after acute myocardial infarction. Am Heart J. 2005 Oct;150(4):652–658. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2005.03.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Otte C, McCaffery J, Ali S, Whooley MA. Association of a serotonin transporter polymorphism (5-HTTLPR) with depression, perceived stress, and norepinephrine in patients with coronary disease: the Heart and Soul Study. Am J Psychiatry. 2007 Sep;164(9):1379–1384. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.06101617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ramasubbu R, Tobias R, Buchan AM, Bech-Hansen NT. Serotonin transporter gene promoter region polymorphism associated with poststroke major depression. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2006 Winter;18(1):96–99. doi: 10.1176/jnp.18.1.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mossner R, Riederer P. Allelic variation of a functional promoter polymorphism of the serotonin transporter and depression in Parkinson's disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2007 Feb;13(1):62. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2006.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Phillips-Bute B, Mathew JP, Blumenthal JA, et al. Relationship of genetic variability and depressive symptoms to adverse events after coronary artery bypass graft surgery. Psychosom Med. 2008 Nov;70(9):953–959. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e318187aee6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.McCaffery JM, Bleil M, Pogue-Geile MF, Ferrell RE, Manuck SB. Allelic variation in the serotonin transporter gene-linked polymorphic region (5-HTTLPR) and cardiovascular reactivity in young adult male and female twins of European-American descent. Psychosom Med. 2003 Sep-Oct;65(5):721–728. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000088585.67365.1d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lotrich FE, Ferrell RE, Rabinovitz M, Pollock BG. Risk for depression during interferon-alpha treatment is affected by the serotonin transporter polymorphism. Biol Psychiatry. 2009 Feb 15;65(4):344–348. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Araya R, Hu X, Heron J, et al. Effects of stressful life events, maternal depression and 5-HTTLPR genotype on emotional symptoms in pre-adolescent children. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2009 Jul 5;150B(5):670–682. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Uher R, McGuffin P. The moderation by the serotonin transporter gene of environmental adversity in the aetiology of mental illness: review and methodological analysis. Mol Psychiatry. 2008 Feb;13(2):131–146. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4002067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Surtees PG, Wainwright NW, Willis-Owen SA, Luben R, Day NE, Flint J. Social adversity, the serotonin transporter (5-HTTLPR) polymorphism and major depressive disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2006 Feb 1;59(3):224–229. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gillespie NA, Whitfield JB, Williams B, Heath AC, Martin NG. The relationship between stressful life events, the serotonin transporter (5-HTTLPR) genotype and major depression. Psychol Med. 2005 Jan;35(1):101–111. doi: 10.1017/s0033291704002727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cohen LH, Towbes LC, Flocco R. Effects of induced mood on self-reported life events and perceived and received social support. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1988 Oct;55(4):669–674. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.55.4.669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kessler RC, Magee WJ. Childhood adversities and adult depression: basic patterns of association in a US national survey. Psychol Med. 1993 Aug;23(3):679–690. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700025460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB. Validation and utility of a self-report version of PRIME-MD: the PHQ primary care study. Primary Care Evaluation of Mental Disorders. Patient Health Questionnaire. JAMA. 1999 Nov 10;282(18):1737–1744. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.18.1737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001 Sep;16(9):606–613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Costa PT, Jr, McCrae RR. Stability and change in personality assessment: the revised NEO Personality Inventory in the year 2000. J Pers Assess. 1997;68(1):86–94. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa6801_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Connor KM, Davidson JR. Development of a new resilience scale: the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC) Depress Anxiety. 2003;18(2):76–82. doi: 10.1002/da.10113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav. 1983 Dec;24(4):385–396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sarason IG, Sarason BR, Potter EH, 3rd, Antoni MH. Life events, social support, and illness. Psychosom Med. 1985 Mar-Apr;47(2):156–163. doi: 10.1097/00006842-198503000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Taylor SE, Way BM, Welch WT, Hilmert CJ, Lehman BJ, Eisenberger NI. Early family environment, current adversity, the serotonin transporter promoter polymorphism, and depressive symptomatology. Biol Psychiatry. 2006 Oct 1;60(7):671–676. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Clark DA, Steer RA, Beck AT, Ross L. Psychometric characteristics of revised Sociotropy and Autonomy Scales in college students. Behav Res Ther. 1995 Mar;33(3):325–334. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(94)00074-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rogers NL, Cole SA, Lan HC, Crossa A, Demerath EW. New saliva DNA collection method compared to buccal cell collection techniques for epidemiological studies. Am J Hum Biol. 2007 May-Jun;19(3):319–326. doi: 10.1002/ajhb.20586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Gelernter J, Cubells JF, Kidd JR, Pakstis AJ, Kidd KK. Population studies of polymorphisms of the serotonin transporter protein gene. Am J Med Genet. 1999;88(1):61–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hu XZ, Lipsky RH, Zhu G, et al. Serotonin transporter promoter gain-of-function genotypes are linked to obsessive-compulsive disorder. Am J Hum Genet. 2006 May;78(5):815–826. doi: 10.1086/503850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Stein MB, Seedat S, Gelernter J. Serotonin transporter gene promoter polymorphism predicts SSRI response in generalized social anxiety disorder. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2006 Jul;187(1):68–72. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0349-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hamer D, Sirota L. Beware the chopsticks gene. Mol Psychiatry. 2000;5(1):11–13. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4000662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Clarke DM, Currie KC. Depression, anxiety and their relationship with chronic diseases: a review of the epidemiology, risk and treatment evidence. Med J Aust. 2009 Apr 6;190(7):S54–60. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2009.tb02471.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Glassman AH, Shapiro PA. Depression and the course of coronary artery disease. Am J Psychiatry. 1998 Jan;155(1):4–11. doi: 10.1176/ajp.155.1.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Paykel ES. Cognitive therapy in relapse prevention in depression. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2007 Feb;10(1):131–136. doi: 10.1017/S1461145706006912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Fahrenkopf AM, Sectish TC, Barger LK, et al. Rates of medication errors among depressed and burnt out residents: prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2008 Mar 1;336(7642):488–491. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39469.763218.BE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.West CP, Huschka MM, Novotny PJ, et al. Association of perceived medical errors with resident distress and empathy: a prospective longitudinal study. JAMA. 2006 Sep 6;296(9):1071–1078. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.9.1071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.O'Neil AC, Petersen LA, Cook EF, Bates DW, Lee TH, Brennan TA. Physician reporting compared with medical-record review to identify adverse medical events. Ann Intern Med. 1993 Sep 1;119(5):370–376. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-119-5-199309010-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Weingart SN, Callanan LD, Ship AN, Aronson MD. A physician-based voluntary reporting system for adverse events and medical errors. J Gen Intern Med. 2001 Dec;16(12):809–814. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2001.10231.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Moffitt TE, Caspi A, Rutter M. Strategy for investigating interactions between measured genes and measured environments. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005 May;62(5):473–481. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.5.473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.