Abstract

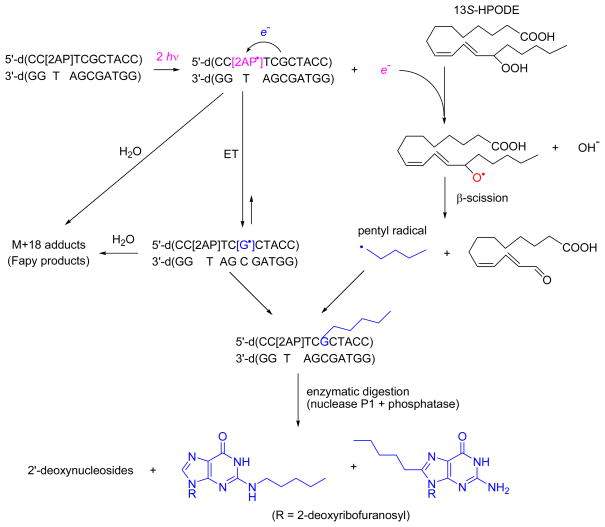

The in vivo metabolism of plasma lipids generates lipid hydroperoxides that, upon one-electron reduction, gives rise to a wide spectrum of genotoxic unsaturated aldehydes and epoxides. These metabolites react with cellular DNA to form a variety of pre-mutagenic DNA lesions. The mechanisms of action of the radical precursors of these genotoxic electrophiles are poorly understood. In this work we investigated the nature of DNA products formed via one-electron reduction of 13S-hydroperoxy-9Z,11E-octadecadienoic acid (13S-HPODE), a typical lipid molecule, and the reactions of the free radicals thus generated with guanine neutral radicals, G(-H)•. A novel approach was devised to generate these intermediates in solution. The two-photon-induced ionization of 2-aminopurine (2AP) within the 2′-deoxyoligonucleotide 5′-d(CC[2AP]TCGCTACC) by intense nanosecond 308 nm excimer laser pulses was employed to simultaneously generate hydrated electrons and radical cations 2AP•+. The latter radicals either in cationic or neutral forms, rapidly oxidize the nearby G base to form G(-H)•. In deoxygenated buffer solutions (pH 7.5), the hydrated electrons rapidly reduce 13S-HPODE and the highly unstable alkoxyl radicals formed undergo a prompt β-scission to pentyl radicals that readily combine with G(-H)•. Two novel guanine products in these oligonucleotides, 8-pentyl- and N2-pentylguanine, were identified. It is shown that the DNA secondary structure significantly affects the ratio of 8-pentyl- and N2-pentylguanine lesions that changes from 0.9 : 1 in single-stranded, to 1 : 0.2 in double-stranded oligonucleotides. The alkylation of guanine by alkyl radicals derived from lipid hydroperoxides might contribute to the genotoxic modification of cellular DNA under hypoxic conditions. Thus, further research is warranted on the detection of pentylguanine lesions and other alkylguanines in vivo.

Keywords: DNA damage, lipid hydroperoxide, one-electron reduction, free radical, alkylation

Introduction

There is extensive evidence that chronic inflammation and infection are associated with malignant cell transformation and the development of many human cancers.[1–3] The overproduction of radicals under conditions of oxidative stress developed in response to inflammation, results in an enhanced generation of secondary reactive oxygen species such as lipid peroxyl radicals, hydroperoxides (ROOH) and organic peroxides from membrane lipids containing polyunsaturated fatty acids.[4, 5] These secondary reactive species can induce permanent genetic instabilities that lead to an increased risk of cancers.[6, 7]

The primary non-radical products of lipid peroxidation are lipid hydroperoxides.[8–10] The one-electron reduction of lipid hydroperoxides is one of the important pathways of their metabolic activation in vivo.[11, 12] The electrophilic alkoxyl radicals formed are strong one-electron oxidants (E7 = 1.55 – 1.65 V vs NHE)[13] that can potentially damage cellular DNA by electron or H-atom abstraction mechanisms.[11, 14] However, bimolecular oxidative reactions of alkoxyl radicals are complicated because of their fast decomposition to form carbon-centered radicals and non-radical products such as aldehydes and epoxides.[15, 16] Although the chemistry of formation and the genotoxic effects of covalent DNA adducts produced by electrophilic aldehydes and epoxides has been studied extensively,[4–6, 10, 14] the fates of the radical species derived from the one-electron reduction of lipid hydroperoxides and their role in the formation of DNA adducts remain poorly understood. Here, we explored the possibility that carbon-centered radicals derived from the one-electron reduction of lipid hydroperoxides can form stable adducts by reactions with guanine neutral radicals generated by independent one-electron oxidation mechanisms.[17] We establish that, in principle, such radical – radical reactions are feasible and that alkyl – guanine radical combination reactions can lead to stable covalently alkylated guanine adducts in the absence of molecular oxygen.

We devised a photochemical method for simultaneously generating a hydrated electron for the one-electron reduction of lipid hydroperoxides, and an electron acceptor for oxidizing a single, site-specific guanine embedded in an oligonucleotide (Scheme 1). This oligonucleotide contained the target guanine positioned two base pair steps from a 2-aminopurine (2AP) nucleobase analog. The 2AP was selectively ionized by a two-photon absorption mechanism using intense 308 nm excimer laser pulses thus yielding the 2AP•+ radical cations together with a hydrated electron, without photoionizing any of the canonical DNA bases.[18–21] The 2AP•+ radicals rapidly deprotonate to yield the neutral 2AP(-H)• radicals. Both the 2AP•+ and 2AP(-H)• radicals are strong one-electron oxidants that selectively oxidize nearby guanine bases to generate guanine neutral radicals, G(-H)•. The hydrated electrons formed as a result of the photoionization of 2AP, can rapidly reduce lipid hydroperoxides.[22] Here we use 13S-hydroperoxy-9Z,11E-octadecadienoic acid (13S-HPODE), a lipid peroxide that is formed in cellular environments by the enzymatic[23] or free radical oxidation[8, 9] of linoleic acid, the major ω-6 polyunsaturated fatty acid of plasma lipids. Therefore, this photochemical method is ideally suited to explore combination reactions of G(-H)• radicals with radical species produced by the one-electron reduction of lipid hydroperoxides. The end-products of these radical-to-radical reactions were isolated by HPLC and identified by mass spectrometry methods. In deoxygenated solutions, two oligonucleotide adducts containing guanine lesions with masses that were 70 Da greater than the mass of the parent guanine base were isolated. These lesions were identified as 8-pentyl- and N2-pentyl-2′-deoxyguanosines. These results suggest that the metabolic activation of plasma lipids may give rise to potentially genotoxic DNA adducts under hypoxic conditions, and that further research is warranted on the detection of lipid hydroperoxide-related DNA adducts in vivo.

Scheme 1.

Photochemical generation of guanine and pentyl radicals triggered by the two-photon ionization of 2-aminopurine in the presence 13S-HPODE and subsequent formation of alkylguanine and Fapy lesions in double-stranded DNA. Radical species 2AP•+/2AP(-H)• and G•+/G(-H)• are designated as 2AP• and G•, respectively; ET is electron transfer.

Results

Experimental Design

In this work we explored the combination of guanine neutral radicals and carbon-centered radicals derived from one-electron reduction of lipid hydroperoxide by hydrated electrons. In these experiments we used the 5′-d(CC[2AP]TCGCTACC) oligonucleotide sequence with single 2AP and G bases positioned at defined sites separated by a TC dinucleotide step. Our previous laser flash photolysis experiments have shown that intense nanosecond 308 nm laser pulse excitation of this sequence results in the efficient and selective two-photon-induced ionization of 2AP residues with the concomitant formation of 2AP•+ radical cations and hydrated electrons:[18–21]

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

| (4) |

| (5) |

| (6) |

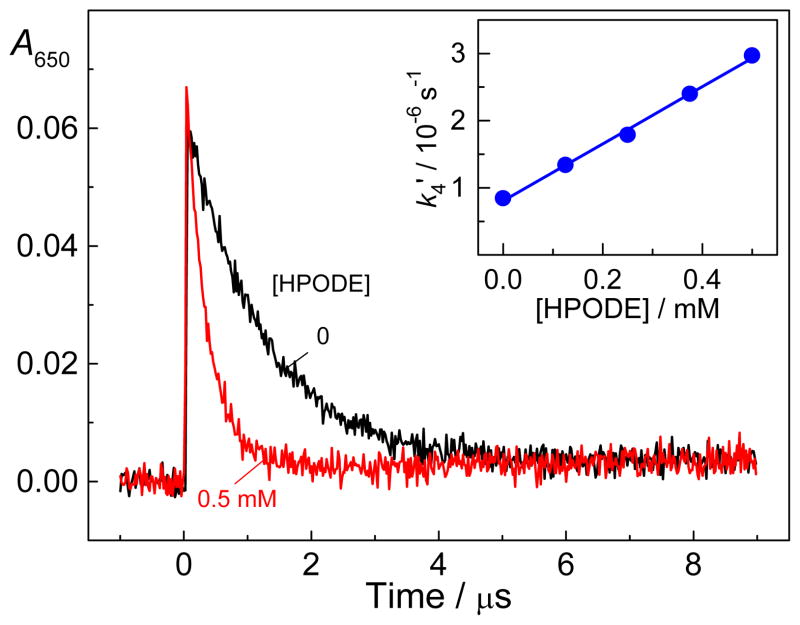

According to these transient absorption measurements, the oxidation of guanine residues by the 2AP•+/2AP(-H)• radicals to form G(-H)• radicals (reaction 3), identified by the characteristic narrow absorption band at 315 nm, is complete within ~100 μs.[19] In the presence of 13S-HPODE, the hydrated electrons are expected to induce one-electron reduction of lipid hydroperoxides (reaction 4).[22] Indeed, in deoxygenated buffer solutions (pH 7.5) the decay of hydrated electrons monitored at 650 nm is markedly accelerated in the presence of 13S-HPODE on a microsecond time scale (Figure 1), and the decay constant, k4′, is linearly proportional to the 13S-HPODE concentration (inset in Figure 1). From the slope of this straight line we obtain the value k4 = (3.3±0.3)×109 M−1s−1 that agrees with the value (~ 6 ×109 M−1 cm−1) obtained for the reduction of 13- and 9-hydroperoxides of linoleic acid in aqueous solutions (pH 8.2) with hydrated electrons generated by pulse radiolysis.[22] Thus, the laser flash photolysis experiments show that one-electron reduction of 13S-HPODE (0.5 mM) by hydrated electrons with formation of alkoxyl radicals (reaction 4), is complete within ~1 μs after the laser flash (Figure 1). The latter radicals are unstable and undergo a rapid β-scission (reaction 5) to form secondary C-centered alkyl radicals (R1•) and aldehydes [R2=O(H)].[24–26] In deoxygenated solutions, the combination reaction of G(-H)• and R1• radicals can generate stable end-products (reaction 6), which is considered in the next Sections.

Figure 1.

Effect of 13S-HPODE on the decay kinetics of hydrated electrons derived from the photoionization of the 5′-d(CC[2AP]TCGCTACC) sequence (40 μM) by intense 308 nm laser pulse excitation (60 mJ pulse−1 cm−2) in deoxygenated phosphate buffer solutions (pH 7.5). The inset represents a plot of the first-order rate constants of the decay of hydrated electrons (k4′) as a function of the 13S-HPODE concentration.

End-Products of Radical Combination Reactions

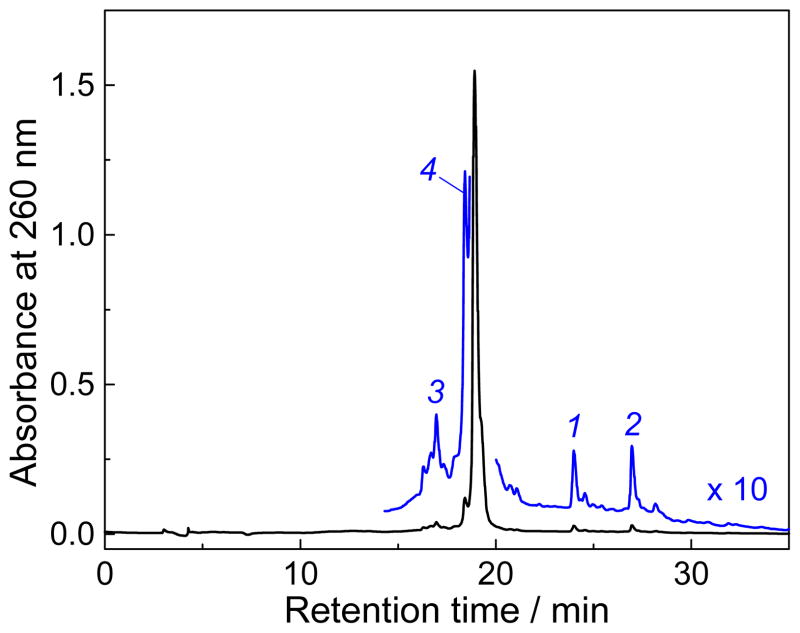

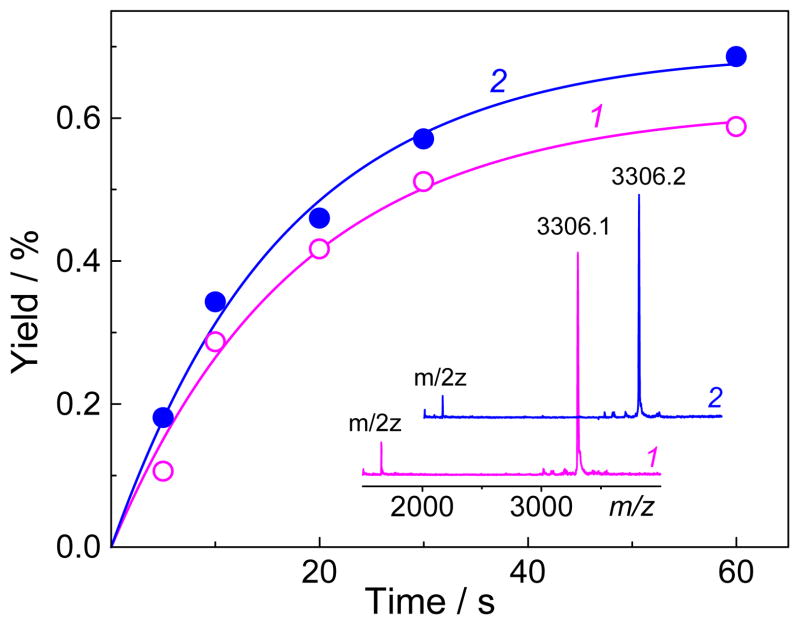

The stable products generated by the two-photon ionization of 5′-d(CC[2AP]TCGCTACC) sequence by intense 308 nm laser pulses in deoxygenated buffer solutions (pH 7.5) containing 0.5 mM 13S-HPODE, were separated by reversed-phase HPLC methods (Figure 2). The unmodified oligonucleotide elutes at 18.9 min and two prominent reaction products 1 and 2 are observed at 24.0 and 27.0 min, respectively. The yields of these products formed rise monotonically with increasing irradiation time (Figure 3). These observations indicate that the adducts 1 and 2 are formed in a ratio of 0.9 : 1 via two parallel reactions. The MALDI-TOF mass spectra of the 24.0 and 27.0 min fractions recorded in the negative mode exhibit the major signals at m/z 3306.1 and 3306.2 (inset in Figure 3), whereas the unmodified sequence exhibits a signal at m/z 3236.3 (data not shown). These oligonucleotide adducts have the same masses (M+70) that within experimental accuracy are greater by 70 Da than the parent oligonucleotide (mass M). The experiments in air-equilibrated solutions showed that the formation of these M+70 adducts is completely suppressed and that the major products are the well-known imidazolone (Iz) lesions[19] detected at m/z = 3227.2 (data not shown).

Figure 2.

Reversed-phase HPLC elution profiles of the end products generated by photoionization of the 5′-d(CC[2AP]TCGCTACC) sequence (40 μM) with a 30 s train of 308 nm laser pulses (60 mJ pulse−1 cm−2, 10 pulse s−1) in deoxygenated buffer solutions (pH 7.5) containing 500 μM 13S-HPODE. HPLC elution conditions (detection of products at 260 nm): 5 – 25 % linear gradient of acetonitrile in 50 mM triethylammonium acetate (pH 7) for 60 min at a flow rate of 1 mL min−1. The unmodified sequence 5′-d(CC[2AP]TCGCTACC) elutes at 18.9 min, two M+70 oligonucleotide adducts (1 and 2) elute at 24.0 and 27.0 min, respectively, and adducts containing M+18 lesions (3 and 4) elute at 16.9 and 18.4 min, respectively,

Figure 3.

Time dependent yields of the oligonucleotide adducts (1 and 2). The samples were excited using the same conditions as in Figure 2. The adduct yields were calculated by integration of the HPLC elution patterns. The inset shows the MALDI-TOF negative ion spectra of these adducts purified by a second HPLC cycle.

In order to determine the position of the alkyl groups in the alkylated guanines, the M+70 oligonucleotide adducts were subjected to enzymatic digestion with snake venom phosphodiesterase I (SVPD I) and bovine spleen phosphodiesterase II (SPD II). These two exonucleases digest single-stranded DNA from the 3′- and 5′-ends, respectively. Detailed analysis of the enzymatic digestion patterns and masses of partially digested oligonucleotide fragments by MALDI-TOF/MS methods showed that the enzyme stalling patterns are consistent with the formation of exonuclease-resistant 5′-d(CC[2AP]TCG* and 5′-G*CTACC fragments. These fragments are products of digestion by SVPD I and SPDII, respectively, and were detected at m/z 1822.4 (data not shown). These results indicate that the oligonucleotide adducts 1 and 2 are guanine lesions (G*) with masses that are greater by 70 Da than the mass of the parent G base.

The presence of 13S-HPODE is critical for formation of the M+70 oligonucleotide adducts, because these adducts were not detected in the controlled experiments without this lipid hydroperoxide (data not shown). In contrast, more hydrophilic adducts 3 and 4 that elute before the unmodified sequence, are also observed either in the presence (Figure 2) or in the absence of 13S-HPODE (data not shown). These adducts were collected and purified. The MALDI-TOF mass spectra of these products recorded in the negative mode exhibit the characteristic signal at m/z 3254.2 (the spectrum of the prominent adduct 4 eluted at 18.4 min, as shown in Figure S1, Supporting Information). These adducts have the same mass (M+18) and can be assigned to the oligonucleotides containing the formamidopyrimidine (Fapy) lesions.[27, 28] The 308 nm laser excitation with intense nanosecond laser pulses induce photoionization of 2AP residues followed by electron abstraction from G bases. Thus, formation of both 2,6-diamino-4-hydroxy-5-formamidopyrimidine (FapyG) and 2,6-diamino-5-formamidopyrimidine (Fapy-2AP) lesions is possible via hydration of G•+ and 2AP•+ radical cations (Scheme 1). In the absence of oxygen, hydrated radicals of purine bases are known to form Fapy lesions.[27, 28] In contrast, oxidation of these radicals by weak oxidants (e.g., O2), can produce 8-oxo-7,8-dihydroguanine (8-oxoG), a ubiquitous oxidation product of DNA,[27, 28] and possibly 8-oxo-2AP lesions. The formation of 8-oxoG lesions was tested using enzymatic digestion of the irradiated oligonucleotides followed by the HPLC-amperometric detection of 8-oxoG nucleosides. Note, this lesion is not observable in HPLC elution profiles because the oligonucleotide adduct containing 8-oxoG lesion co-elutes with the unmodified sequence under our experimental conditions. The yields of 8-oxoG lesions in the oligonucleotides irradiated in deoxygenated solutions are extremely small (0.005 – 0.01%) and do not exceed the background levels of 8-oxoG in the controlled non-irradiated samples. Thus, the total yield (~1.3%) of the M+70 adducts (Figure 3) is at least by factor of ~130 greater than the yields of 8-oxoG lesions. These results clearly indicate that under anaerobic conditions, the major end-products involve alkylation and hydration leading to the M+70 and Fapy adducts, respectively (Scheme 1). However, further investigations along these lines were beyond the scope of this work, because formation of the Fapy lesions is not associated with the presence of 13S-HPODE.

Identification of M+70 Lesions by LC-MS/MS

The 70 Da difference in the masses of the parent guanine and the G lesions in the irradiated oligonucleotides supports the conclusion that the alkylation of guanine by pentyl radicals is occurring. To test this hypothesis, we synthesized authentic standards of uniformly 15N-labeled pentyl-2′-deoxyguanosines using an independent route for the generation of guanine and pentyl radicals (Supporting Information). In this method, the combination of dG(-H)• and pentyl radicals derived from the oxidation of dG and dipentyl sulfoxide by photochemically generated SO4• radicals, produces two major alkylation products, identified as the 8-pentyl- and N2-pentyl-2′-deoxyguanosine products (Figures S2 – S5, Supporting Information).

The M-70 oligonucleotide adducts 1 and 2 obtained in a series of photochemical experiments (Figure 2) were combined, desalted, and enzymatically digested by nuclease P1 and calf intestinal phosphatase in the presence of the 15N-labeled pentyl-dG standards. Analysis of the digestion products by LC-MS/MS methods showed that pentyl-dG excised from adduct 1 co-elutes with the 15N-labeled 8-pentyl-dG, and pentyl-dG excised from adduct 2 co-elutes with the 15N-labeled N2-pentyl-dG (Figure S6, Supporting Information).

Alkylation of Guanine Bases in a DNA Duplex

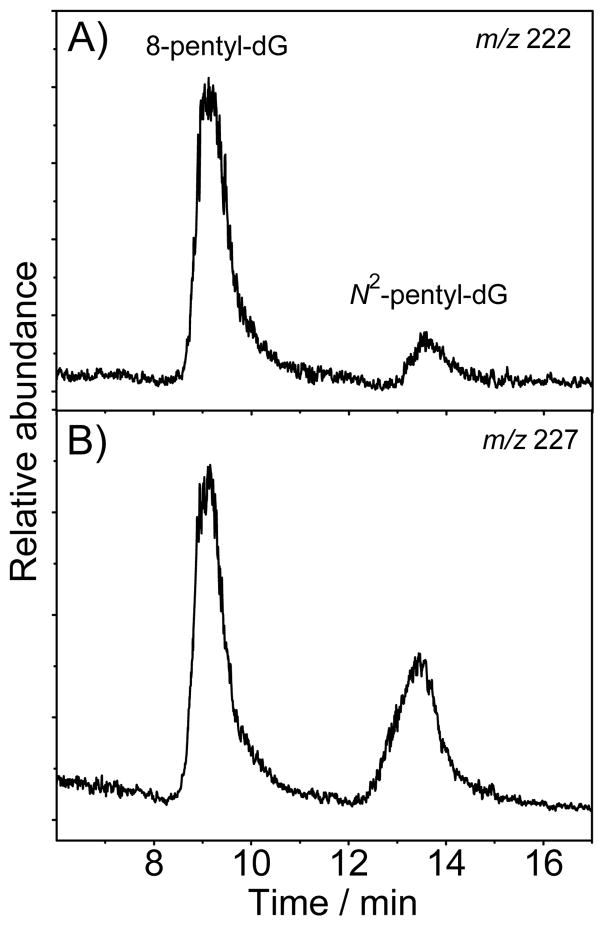

The experiments were performed with the 5′-d(CC[2AP]TCGCTACC) oligonucleotide paired with a fully complementary strand, 5′-d(GGTAGCGATGG) (Scheme 1). In 5 mM phosphate buffer solution (pH 7.5) containing 100 mM NaCl, the duplex obtained by annealing the 2AP-modified strand and its complementary strand with the 2AP residue paired to the T base exhibits a single, well defined cooperative melting curve with a melting point Tm of 50.8±0.7 °C and a hyperchromicity of 25%.[19] The duplexes irradiated by intense 308 nm laser pulses in deoxygenated buffer solutions (pH 7.5) containing 0.5 mM 13S-HPODE were desalted, mixed with the 15N-labeled 8-pentyl-dG and N2-pentyl-dG authentic standards, and digested by nuclease P1 and calf intestinal phosphatase. The digestion products obtained were analyzed by LC-MS methods (Figure 4). The extracted ion chromatograms show that the 8-pentyl-dG and N2-pentyl-dG adducts are indeed formed in double-stranded DNA and that the nucleoside excision products co-elute with the 15N-labeled 8-pentyl-dG and N2-pentyl-dG internal standards. Integration of these chromatograms gives an 8-pentyl-dG/N2-pentyl-dG ratio of 1 : 0.2. Thus, in double-stranded DNA, the efficiency of N2-pentyl-G formation is significantly lower than in the case of single-stranded oligonucleotides.

Figure 4.

LC-MS analysis of the pentyl-2′-deoxyguanosines excised by enzymatic digestion of the d(CC[2AP]TCGCTACC)·5′-d(GGTAGCGATGG) duplexes (40 μM) irradiated by a 30 s train of 308 nm laser pulses (60 mJ pulse−1 cm−2, 10 pulse s−1) in deoxygenated buffer solutions (pH 7.5) containing 500 μM 13S-HPODE. The extracted chromatograms were recordered in the positive mode with specific ion monitoring at m/z 222 and 227. Panel A – 14N-8-pentyl-dG and 14N-N2-pentyl-dG excised from the duplex; Panel B – 15N-8-pentyl-dG and 15N-N2-pentyl-dG internal standards added in a 1 : 0.6 molar ratio.

Discussion

Alkylation of Guanine Triggered by One-Electron Reduction of Lipid Hydroperoxides

In cellular environments, hydroperoxyoctadecadienoic acids (HPODEs) derived from peroxidation of linoleic acid, the major ω-6 polyunsaturated fatty acid present in plasma lipids, are detoxified via a two-electron reduction to the corresponding hydroxyoctadecadienoic acids through the peroxidase activity of cyclooxygenases.[29, 30] In contrast, the one-electron reduction of HPODEs mediated by transition metal ions (e.g., Fe2+) chelated in close proximity to a reactive hydroperoxide generates free radicals and unsaturated aldehydes, which can potentially damage cellular DNA.[31, 32] Detailed spin-trapping studies using a combination of HPLC, EPR and MS methods for the identification of stable radical adducts have shown that alkoxyl radicals can undergo a rapid intramolecular fragmentation via β-scission to form the pentyl radicals and aldehydes as shown in Scheme 1.[25, 26] The rates of intramolecular fragmentation of alkoxyl radicals increase with solvent polarity and, in aqueous solutions, the fragmentation rate constants are typically greater than 106 s−1.[33] For instance, direct pulse radiolysis experiments have shown that the breakdown of tert-butoxyl radicals occurs with the rate constant of 1.4×106 s−1.[34] Thus, we expect that potential bimolecular reactions of the 13S-HPODE alkoxyl radicals with DNA cannot compete with their rapid fragmentation.

Under anaerobic conditions, the pentyl radicals derived from the breakdown of 13S-HPODE can combine with G(-H)• radicals to form stable pentylguanine adducts. Here, we employ two-photon ionization of 2AP residues for simultaneously injecting holes into DNA, to produce G(-H)• radicals, and induce the breakdown of 13S-HPODE by reactions with hydrated electrons (Scheme 1). The decay of guanine radicals occurs via two competitive pathways, which include either the addition of pentyl radicals, or hydration. Under anaerobic conditions, the latter pathway leads to the M+18 adducts, which we identified as the formamidopyrimidine adducts.[27, 28] Our previous laser flash photolysis experiments have shown that the oxidation of G by 2AP-radicals is reversible[18] and, although the equilibrium favors G(-H)•radicals, the formation of Fapy-2AP as well as FapyG adducts is possible. The yields of 8-oxoG, a lesion that constitutes an important biomarker of DNA damage[35], are negligible because the formation of these lesions requires the abstraction of a second electron, which is not feasible under hypoxic conditions.[27, 28] In contrast, in the presence of oxygen, the major oxidation products are the imidazolone lesions, while 8-oxoG is formed in minor quantities.[19] Under these conditions, guanine radicals decay via competitive pathways that include (i) combination with superoxide[19] and peroxyl[36] radicals derived from the trapping of hydrated electrons and alkyl radicals by oxygen to form the Iz lesions, and (ii) hydration followed by the oxidation of the resulting intermediate by molecular oxygen to form 8-oxoG lesions.

In double-stranded DNA the relative yield of N2-pentyl-G lesion is probably diminished because the target exocyclic amino group protons are involved in Watson-Crick hydrogen bonding with cytosine in the opposite strand; thus, the 8-pentyl-G lesion becomes the major alkylation end-product (Figure 4). In double-stranded DNA, alkylation of G bases can occur in both 2AP-modified and the complementary strands. The latter contains six guanines, and holes injected by two-photon ionization of 2AP residues can migrate freely along this strand to form G(-H)• radicals,[37–39] which can combine with pentyl radicals. Our experiments with 5′-d(CATG1*CG2TCCTAC)&·;3′-d(TG7TACG6CAG5G4ATG3T) duplexes, where G* is a BPDE-N2-dG adduct (a product of reaction of the diol epoxide anti-BPDE, 7r,8t-dihydroxy-t9,-10-epoxy-7,8,9,10-tetrahydrobenzo[a]pyrene, with the exocyclic amino group of guanine), have shown that cleavage at G sites in the BPDE-modified strand revealed by gel electrophoresis after the standard hot piperidine treatment, is ~ 10 more efficient than that in the complementary strand.[40] In these experiments, the G(-H)• radicals combine with superoxide radicals to form alkali-labile imidazolone lesions detected in both the modified and complementary strands by the MALDI-TOF/MS methods. Oxidative damage was clearly more efficient at the G3 and G7 sites at the termini where the greater solvent exposure of G•+/G(-H)• radicals may induce “hole sinks”. In turn, damage at G4 in 5′-G4G5 was more efficient than at G5 as predicted by the Saito model of the hole transfer in DNA.[41, 42] Thus, according to these results we expect less efficient alkylation of guanine radicals derived from hole transfer from 2AP-modified strand to the complementary strand.

Biological Implications

Enhanced lipid peroxidation is believed to be one of the key factors of malignant cell transformation and the progression of many human cancers, including hepatocellular carcinoma,[43, 44] prostate cancer,[45, 46] pancreatic cancer,[47] renal cell carcinoma,[7] and colon cancer.[6] Lipid hydroperoxides are the primary non-radical products of lipid peroxidation that can generate a variety of genotoxic intermediates such as free radicals, unsaturated aldehydes and epoxides.[4, 5] In this work we found that the one-electron reduction of 13S-HPODE derived from the peroxidation of linoleic acid, one of the major plasma membrane lipids, generates pentyl radicals. Under anaerobic conditions, the latter radicals can combine with guanine radicals to form 8-pentyl- and N2-pentyl-G lesions. The guanine radicals can be produced by one-electron oxidation reactions of guanine bases in DNA. In vivo, a likely oxidant is the carbonate radical anion, a byproduct of the inflammatory response[35, 48] that can selectively oxidize guanine in DNA by electron abstraction mechanism.[49–51] The neutral guanine radicals derived from the deprotonation of the guanine radical cations have a lifetime that approaches seconds in DNA in aqueous environments.[49, 50] Therefore, in principle such radical-radical reactions could occur in vivo under conditions of significant oxidative stress. Analogous alkylation reactions of guanine have been reported. The formation of 8-Me-G lesions mediated by methyl radicals has been detected in the oxidation of calf thymus DNA and methylhydrazine catalyzed by horseradish peroxidase.[52] In turn, in vivo the metabolic activation of carcinogen 1,2-dimethylhydrazine generates a series of the methylguanine lesions including 7-Me-G, O6-Me-G and 8-Me-G detected in the liver and colon DNA of rats.[53–55] EPR studies have shown that in vivo, the model tert-butyl hydroperoxide is metabolized to form methyl radicals.[56] The enhanced levels of the 8-Me-G lesions have been detected in DNA isolated from the liver and stomach of rats treated by tert-butyl hydroperoxide.[56] Alkylation of guanine by alkyl radicals derived from the metabolic activation of plasma lipids might contribute to the genotoxic modification of cellular DNA. Thus, further research is warranted on the detection of pentylguanine lesions and other alkylated guanine products in vivo.

Experimental Section

Materials

All chemicals (analytical grade) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Fine Chemicals. The uniformly 15N-labeled dG (15N > 98%) was obtained from Cambridge Isotope Laboratories (Andover, MA), and 13S-HPODE was purchased from Cayman Chemicals (Ann Arbor, MI). Deuteration of dG at the C8 position was achieved by heating solutions of dG in D2O as described by Perrier et al.[57] The site of deuteration was confirmed by LC-MS/MS analysis. The oligonucleotides were synthesized by standard automated phosphoramidite chemistry techniques. Phophoramidites and other chemicals required for oligonucleotide synthesis were obtained from Glen Research (Sterling, VA). The crude oligonucleotides were purified by reversed-phase HPLC, detritylated in 80% acetic acid according to standard protocols, and desalted using reversed-phase HPLC. The composition of the oligonucleotides was confirmed by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry.

Laser Flash Photolysis

The transient absorption spectra and kinetics of free radical reactions were monitored directly using a fully-computerized kinetic spectrometer system (~7 ns response time) described elsewhere.[19] Briefly, 308 nm nanosecond XeCl excimer laser pulses were used to photolyse the 5′-d(CC[2AP]TCGCTACC) oligonucleotide (40 μM) in 0.25 mL phosphate buffer solutions (5 mM, pH 7.5) containing 500 μM 13S-HPODE. Before laser excitation, the sample solutions were thoroughly purged with argon to remove oxygen. The transient absorbance was probed along a 1 cm optical path by a light beam from a 75 W xenon arc lamp with its light beam oriented perpendicular to the laser beam. The signal was recorded by a Tektronix TDS 5052 oscilloscope operating in its high resolution mode that typically allows for suitable signal/noise ratios after each single laser shot.

The second order rate constants were typically determined by least squares fits of the appropriate kinetic equations to the transient absorption profiles obtained in five different experiments with five different samples.

Separation by Reversed-Phase HPLC

The photochemical reaction products were separated using an Agilent 1200 Series LC system (quaternary LC pump with degasser, thermostated column compartments, and diode array detector). Typically, the reversed-phase HPLC separations of the irradiated oligonucleotides were performed on an analytical (250 × 4.6 mm i.d.) Polaris C18A column (Varian, Walnut Creek, CA) employing a 5 – 25% linear gradient of acetonitrile in 50 mM triethylammonium acetate in water (pH 7) for 60 min at a flow rate of 1 mL min−1. The purified oligonucleotide adducts were desalted by reversed-phase HPLC using the following mobile phases: 5 mM sodium phosphate (pH 7.5) (10 min), deionized water (10 min), and 50% methanol in water (15 min), concentrated under vacuum and subjected to MALDI-TOF/MS analysis.

Synthesis of the 15N-Labeled Pentyl-2′-deoxyguanosine Authentic Standards

The authentic standards of uniformly 15N-labeled 8-pentyl- and N2-pentyl-2′-deoxyguanosines were synthesized using the photochemical method described in the Supporting Information. Briefly, the samples of 15N-labeled dG (0.1 μmole) and dipentyl sulfoxide (0.1 μmole) in 0.5 mL deoxygenated phosphate buffer solutions (pH 7.5) containing 10 mM Na2S2O8 were irradiated for 15 s by a 300 – 340 nm light (~ 100 mW cm−2) of a Xe arc lamp. The pentyl-2′-deoxyguanosines were separated by reversed-phase HPLC methods. In typical separations on an analytical (150 × 4.6 mm i.d.) Zorbax SB-C18 column (Agilent, Bridgeport, NJ) and employing a 1 – 40% linear gradient of methanol in 20 mM ammonium acetate in water (pH 7) for 60 min at a flow rate of 1 mL min−1, the unmodified dG elutes at 7.1 min, the 8-pentyl-dG product at 30.6 min and the N2-pentyl-dG product at 32.3 min. The integrity and composition of the pentyl-dG products thus obtained were confirmed by analysis of LC-MS/MS (Figures S3 – S5) and UV-absorption spectra (Figure S2).

Enzymatic Digestion of Oligonucleotide Adducts

The solutions of the M+70 adducts (~6 μmole) prepared by laser pulse irradiation of the 5′-d(CC[2AP]TCGCTACC) sequence in deoxygenated phosphate buffer solutions (pH 7.5) containing 13S-HPODE, were mixed with aliquots (1 μmole) of the 15N-labeled pentyl-dG internal standards and evaporated to dryness. The samples dissolved in 50 μL of 1 M sodium acetate solutions containing 45 mM ZnCl2 were incubated overnight with 2 units of nuclease P1 and 2 units of calf intestinal phosphatase at 37 °C. Following enzyme removal by centrifugal filtration, the pentyl-dG products were first separated from the nucleoside mixture by HPLC and subjected to LC-MS/MS analysis using an Agilent 1100 Series capillary LC/MSD Ion Trap XCT or an Agilent 1100 Series LC/VSD mono-quadrupole mass spectrometer equipped with electrospray ion sources.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Jean Cadet for insightful discussions. This work was supported by the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (5 R01 ES 011589-07). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences or the National Institutes of Health. Components of this work were conducted in the Shared Instrumentation Facility at NYU that was constructed with support from Research Facilities Improvement (C06 RR-16572) from the National Center for Research Resources, National Institutes of Health. The acquisition of the ion trap was supported by the National Science Foundation (CHE-0234863).

Footnotes

Supporting information for this article is available on the WWW under http://www.wiley-vch.de/home/chemistry/ or from the author.

RERERENCES

- 1.Balkwill F, Mantovani A. Lancet. 2001;357:539–545. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04046-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Coussens LM, Werb Z. Nature. 2002;420:860–867. doi: 10.1038/nature01322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bartsch H, Nair J. Cancer Detect Prev. 2004;28:385–391. doi: 10.1016/j.cdp.2004.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee SH, Blair IA. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2001;11:148–155. doi: 10.1016/s1050-1738(01)00094-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marnett LJ. Toxicology. 2002;181–182:219–222. doi: 10.1016/s0300-483x(02)00448-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bartsch H, Nair J, Owen RW. Biol Chem. 2002;383:915–921. doi: 10.1515/BC.2002.098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gago-Dominguez M, Castelao JE, Yuan JM, Ross RK, Yu MC. Cancer Causes Control. 2002;13:287–293. doi: 10.1023/a:1015044518505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Porter NA, Caldwell SE, Mills KA. Lipids. 1995;30:277–290. doi: 10.1007/BF02536034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schneider C, Porter NA, Brash AR. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:15539–15543. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R800001200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blair IA. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:15545–15549. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R700051200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gardner HW. Free Radic Biol Med. 1989;7:65–86. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(89)90102-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dix TA, Aikens J. Chem Res Toxicol. 1993;6:2–18. doi: 10.1021/tx00031a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Koppenol WH. FEBS Lett. 1990;264:165–167. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(90)80239-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marnett LJ. Carcinogenesis. 2000;21:361–370. doi: 10.1093/carcin/21.3.361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Labeque R, Marnett LJ. J Am Chem Soc. 1988;109:2828–2829. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wilcox AL, Marnett LJ. Chem Res Toxicol. 1993;6:413–416. doi: 10.1021/tx00034a003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Steenken S, Jovanovic SV. J Am Chem Soc. 1997;119:617–618. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shafirovich V, Dourandin A, Huang W, Luneva NP, Geacintov NE. J Phys Chem B. 1999;103:10924–10933. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Misiaszek R, Crean C, Joffe A, Geacintov NE, Shafirovich V. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:32106–32115. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M313904200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Misiaszek R, Uvaydov Y, Crean C, Geacintov NE, Shafirovich V. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:6293–6300. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M412253200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Misiaszek R, Crean C, Geacintov NE, Shafirovich V. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:2191–2200. doi: 10.1021/ja044390r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bors W, Tait D, Michel C, Saran M, Erben-Russ M. Israel J Chem. 1984;24:17–24. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kamitani H, Geller M, Eling T. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:21569–21577. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.34.21569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Garssen GJ, Vliegenthart JF, Boldingh J. Biochem J. 1971;122:327–332. doi: 10.1042/bj1220327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chamulitrat W, Mason RP. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1990;282:65–69. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(90)90087-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Iimura S, Iwahashi H. J Biochem. 2006;139:671–676. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvj082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cadet J, Douki T, Ravanat JL. Acc Chem Res. 2008;41:1075–1083. doi: 10.1021/ar700245e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Steenken S. Chem Rev. 1989;89:503–520. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Laneuville O, Breuer DK, Xu N, Huang ZH, Gage DA, Watson JT, Lagarde M, DeWitt DL, Smith WL. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:19330–19336. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.33.19330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hamberg M. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1998;349:376–380. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1997.0443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Girotti AW. J Lipid Res. 1998;39:1529–1542. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee SH, Oe T, Blair IA. Science. 2001;292:2083–2086. doi: 10.1126/science.1059501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Weber M, Fischer H. J Am Chem Soc. 1999;121:7381–7388. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Erben-Russ M, Michel C, Bors W, MS J Phys Chem. 1987;91:2362–2365. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cadet J, Douki T, Ravanat JL. Nat Chem Biol. 2006;2:348–349. doi: 10.1038/nchembio0706-348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Crean C, Geacintov NE, Shafirovich V. Chem Res Toxicol. 2008;21:358–373. doi: 10.1021/tx700281e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nunez ME, Hall DB, Barton JK. Chem Biol. 1999;6:85–97. doi: 10.1016/S1074-5521(99)80005-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schuster GB. Acc Chem Res. 2000;33:253–260. doi: 10.1021/ar980059z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Giese B. Acc Chem Res. 2000;33:631–636. doi: 10.1021/ar990040b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yun BH, Lee YA, Kim SK, Kuzmin V, Kolbanovskiy A, Dedon PC, Geacintov NE, Shafirovich V. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:9321–9332. doi: 10.1021/ja066954s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sugiyama H, Saito I. J Am Chem Soc. 1996;118:7063–7068. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Saito I, Nakamura T, Nakatani K, Yoshioka Y, Yamaguchi K, Sugiyama H. J Am Chem Soc. 1998;120:12686–12687. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Caldwell SH, Crespo DM, Kang HS, Al-Osaimi AM. Gastroenterology. 2004;127:S97–103. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Marrero JA. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2005;21:308–312. doi: 10.1097/01.mog.0000159817.55661.ca. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nelson WG, De Marzo AM, DeWeese TL, Isaac L. J Urology. 2004;172:S6–S12. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000142058.99614.ff. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.De Marzo AM, DeWeese TL, Platz EA, Meeker AK, Nakayama M, Epstein JI, Isaacs WB, Nelson WG. J Cell Biochem. 2004;91:459–477. doi: 10.1002/jcb.10747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Li D, Jiao L. Int J Gastrointest Cancer. 2003;33:3–14. doi: 10.1385/IJGC:33:1:3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dedon PC, Tannenbaum SR. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2004;423:12–22. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2003.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shafirovich V, Dourandin A, Huang W, Geacintov NE. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:24621–24626. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M101131200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Joffe A, Geacintov NE, Shafirovich V. Chem Res Toxicol. 2003;16:1528–1538. doi: 10.1021/tx034142t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Crean C, Uvaydov Y, Geacintov NG, Shafirovich V. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:742–755. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm1092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Augusto O, Cavalieri EL, Rogan EG, RamaKrishna NV, Kolar C. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:22093–22096. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rogers KJ, Pegg AE. Cancer Res. 1977;37:4082–4087. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Herron DC, Shank RC. Cancer Res. 1981;41:3967–3972. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Netto LE, RamaKrishna NV, Kolar C, Cavalieri EL, Rogan EG, Lawson TA, Augusto O. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:21524–21527. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hix S, Kadiiska MB, Mason RP, Augusto O. Chem Res Toxicol. 2000;13:1056–1064. doi: 10.1021/tx000130l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Perrier S, Hau J, Gasparutto D, Cadet J, Favier A, Ravanat JL. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:5703–5710. doi: 10.1021/ja057656i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.