Abstract

We employ computer simulations and thermodynamic integration to analyze the effects of bending rigidity and slit confinement on the free energy cost of tying knots, ΔFknotting, on polymer chains under tension. A tension-dependent, nonzero optimal stiffness κmin exists, for which ΔFknotting is minimal. For a polymer chain with several stiffness domains, each containing a large amount of monomers, the domain with stiffness κmin will be preferred by the knot. A local analysis of the bending in the interior of the knot reveals that local stretching of chains at the braid region is responsible for the fact that the tension-dependent optimal stiffness has a nonzero value. The reduction in ΔFknotting for a chain with optimal stiffness relative to the flexible chain can be enhanced by tuning the slit width of the 2D confinement and increasing the knot complexity. The optimal stiffness itself is independent of the knot types we considered, while confinement shifts it toward lower values.

1. Introduction

While in the macroscopic world it is clear that the effort needed to tie a knot in wire or string will always increase if it is made more rigid, for equivalent microscopic objects, polymers, the same does not hold. Instead, it is found that the free energy cost of knotting a polymer, ΔFknotting, has a minimum at a nonzero stiffness.1 This finding is particularly interesting in the context of biological macromolecules, such as DNA or RNA, where on the one hand knotting is known to occur2,3 and has significant effects on key processes,4−6 while on the other rigidity may depend sensitively on the base sequence,7−9 leading to varying flexibility along the polymer. Furthermore, there is evidence of correlations between DNA stiffness and sites preferred by type II topoisomerases,1 enzymes that regulate knotting.10

It is expected that the rigidity dependence of ΔFknotting will affect the behavior of knots in DNA with nonuniform flexibility, for example by localizing them in regions with favorable stiffness. However, previous work1 neglected a key qualitative feature of biological DNA, namely that it is typically highly confined.11−13 Confinement of a knotted polymer in a good solvent may significantly affect its properties. For example, in contrast to three dimensions where they are weakly localized, knots in polymers adsorbed on a surface are strongly localized.14,15 Considering the properties of polymers confined in a slit, simulations of DNA found a nonmonotonic dependence of the knotting probability on the slit width,16 and for flexible polymers evidence was found that the particular topology is important.17 While previous work on knotting in confinement has focused on polymers that have one specific stiffness, here we apply a simple model for a polymer chain under tension to investigate the dependence of ΔFknotting on rigidity for various widths of the geometrical confinement. We find that a local stretching of the chains at the braiding region of the knots is responsible for the fact that the optimal bending rigidity for knot formation, κmin, differs from zero. Geometric confinement, however, pushes this optimal rigidity toward smaller values. The effect of confinement on κmin as well as the amount by which ΔFknotting is reduced for the optimal rigidity κmin depends sensitively on the tension applied to the polymer chain.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows: We first present our model and details about the simulation in section 2. In section 3 we define and explain the observables that have been measured in our simulations. In particular, we define our notion of bending of the polymer chain and establish its connection to ΔFknotting. Section 4 introduces the analysis of the local bending in the interior of the knot, which is carried out to investigate which part of the knot is responsible for the reduction of ΔFknotting for polymers with nonzero bending stiffness κmin relative to a fully flexible chain. We present our results in section 5, whereas in section 6 we summarize and draw our conclusions.

2. Model and Simulation Details

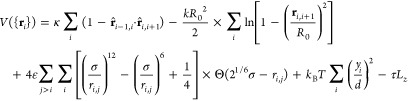

For the polymer chain (linear or knotted), we employ a standard, self-avoiding bead–spring model with rigidity κ, confined parallel to the (x,z)-plane and under tension τ. The interaction part of the Hamiltonian thus reads as

|

1 |

In eq 1, ri,j = rj – ri is the vector from bead i to bead j, located at position vectors ri and rj, respectively, with the unit vector r̂i,j = ri,j/|ri,j|. The first term represents the bending energy of the chain, where κ is the bending rigidity. The second and third terms are the connectivity and steric terms, respectively, whereas Θ(ω) is the Heaviside step function of ω, which renders the Lennard-Jones potential purely repulsive. We choose ε = kBT, k = 30kBT/σ2, and R0 = 1.5σ, preventing the chain from crossing itself and thus conserving its topology. The chain is confined in a slit parallel to the (x, z) plane, which is realized via a harmonic external potential acting on the y-component of the coordinate of each monomer, expressed by the fourth term in eq 1. The last term applies a tension τ on the chain along the z-direction of the setup, with Lz denoting the extension of the chain along this direction.

We used the LAMMPS simulation package18 to carry out constant-NτT molecular dynamics (MD) simulations. The polymers consist of N = 256 monomers for the chains simulated at tensions τ = 0.8 kBT/σ and τ = 0.4 kBT/σ and of N = 512 monomers for the simulations at tensions τ = 0.2 kBT/σ and τ = 0.1 kBT/σ. The longer polymer chains at the two smaller tensions are necessary due to the larger knot size for these tension values. The chains are placed in a simulation box with volume V = 100σ × 150σ × Lz at the two higher tensions and V = 200σ × 300σ × Lz for the lower tensions. The tension τ is realized via a barostat coupled to the fluctuating z-length of the simulation box, while the box lengths in the x- and y-directions are fixed to 100σ and 150σ for the higher tensions 200σ and 300σ for the lower tensions, respectively. The polymer is connected across the periodic boundary conditions in the z-direction to guarantee that the knot is preserved. We also use periodic boundary conditions in the x-direction, while for the y-direction confinement prevents the polymer chain from getting outside the simulation box. For both the thermostat and the barostat, we used a Nosé–Hoover chain with 3 degrees of freedom.19 With m denoting the monomer mass and β = (kBT)−1, t0 = (mσ2β)1/2 sets the unit of time. We integrated the equations of motion with a time step Δt = 10–3t0. The equilibration time was 2 × 107 time steps, and data were collected during a total of 3 × 108 time steps.

3. Definition and Interpretation of Observables

Definition and Physical Interpretation of ΔFknotting(κ)

Let Flin,knot(κ) be the free energies of an unknotted and a knotted chain, respectively, for given κ, τ, and chain length. We define ΔFknotting(κ) ≡ Fknot(κ) – Flin(κ), a quantity that gives a measure for the effort to tie a knot into the chain of N monomers. In our simulations, we do not calculate the absolute value for ΔFknotting(κ) but its value relative to ΔFknotting(κ = 0) of a flexible chain, a procedure that removes the N-dependence for a linear and a knotted chain of the same degree of polymerization N. Thus, we calculate Ψ(κ) ≡ ΔFknotting(κ) – ΔFknotting(0), which has a direct physical interpretation: Let us consider a long polymer chain with various domains, which differ by their respective bending stiffness κi and the number of monomers they contain Ni. Then, the quantity Ψ(κ) allows us to predict the probability for the knot to be found in the ith domain relative to the probability for it being in the jth domain as

| 2 |

An implicit assumption entering eq 2 is that the length of chain segments, Ni, is much longer than the knot size NK, so that for most configurations the part of the polymer chain that is affected by the knot is localized in only one of the domains. Because of the applied tension τ, the knotted part of the chain will always remain finite. In ref (1) it was shown that at fixed κ the size of the knot does not scale with N, the number of monomers on the chain, but rather as NK ∼ (kBT/τ)α with some exponent α. The reason for this is that the stretched polymer forms a series of tension blobs,20 whose size scales with the tension τ but not with N. The knot can only be in one of those blobs; therefore, NK will be finite for any nonzero tension τ. Therefore, for sufficiently large Ni, eq 2 indeed provides a good prediction for Pi. In ref (1) the prediction of eq 2 was tested for a simulation of a polymer chain with two stiffness domains.

Definition and Interpretation of the Chain’s Bending B̂

With r̂j,j+1 denoting the unit vector between monomers j and j + 1, we define the quantity

| 3 |

for any configuration of its monomers and call it the bending of the chain; evidently it holds that B̂ ≥ 0. One can check that this definition of the bending is sensible for various special cases. For instance, for a configuration with a straight polymer chain this definition gives the minimum value for B̂, namely B̂ = 0. The contribution to V({ri}) defined in (1) due to the bending stiffness is κB̂. Moreover BT(κ) ≡ ⟨B̂⟩ is the thermodynamic expectation value of the same for a chain of topology T ∈ {knot, linear}.

With FT(κ) denoting the free energy of the polymer, it holds that ∂FT(κ)/∂κ = BT(κ). This allows us to calculate how the cost of knotting changes with bending stiffness κ: Introducing ΔB(κ) ≡ Bknot(κ) – Blinear(κ), it follows that ∂ΔFknotting(κ)/∂κ = ΔB(κ). The free energy cost of knotting is therefore

and thus

| 4 |

The existence of a minimum of Ψ(κ) for κ ≠ 0 will depend on the sign of the slope of Ψ(κ) at κ = 0, ΔB(0). If ΔB(0) < 0, we expect an optimal knotting rigidity κmin ≠ 0, whereas we anticipate a monotonically increasing function Ψ(κ) in the opposite case, ΔB(0) ≥ 0. This is a reasonable expectation, since we will always obtain ΔB(κ) > 0 for sufficiently stiff chains. Indeed, for βκ ≫ 1, a linear polymer will adopt an almost straight configuration with B̂ ≈ 0, as configurations with nonzero B̂ are penalized by a high bending energy. B̂ = 0 is unique for the straight configuration, which is of course not knotted. Therefore, ΔB(κ) > 0 will hold for all knots in the βκ ≫ 1 regime.

To illustrate this further, let us for example consider a stiff polymer chain with a trefoil knot. Its minimal energy is obtained for a straight polymer chain with an approximately circular domain at the location of the knot. The circle is tangent to the braid point and contains NK(κ) ≅ [2π2κ/(τl)]1/2 monomers, where l ≅ σ is the bond length.21 Accordingly, ΔB(κ) ≅ (2π2τl)1/2/κ > 0 in this limit.

4. Analysis of the Local Bending in the Knotted Domain

Having in mind the goal of localizing which part of the polymer in the vicinity of the knot is contributing to an increased or decreased average bending and therefore to a nonvanishing ΔB(κ), we need to determine the knotted domain on the polymer chain. We define the knotted state of open subsections by introducing a topologically neutral closure scheme, which transforms an open string into a ring polymer that has a mathematically well-defined topological state.22−24 We used a scheme where the end points of the open polymer are connected to a sphere at infinity in the direction of the vector from the centroid to the respective end point. The knotted part of the polymer chain is then the smallest domain for which the closure yields a ring polymer that has the correct Alexander polynomial.

Once the ends of the knot have been identified, we introduce a new enumeration scheme for the monomers, denoted by the Greek integer index α, which can have positive as well as negative values. The two monomers in the interior of the knot that lie n bonds away from the end points obtain the index α = −n, whereas the two monomers to be found n bonds away at the exterior of the knot are assigned the index α = n; accordingly, α = 0 for the two end points of the knot. There exist, thus, for every value of α two position vectors rαj, j = L, R, where L/R denotes whether the monomer is at separation α from the left/right end point of the knot. Accordingly, we define the local bending contribution from the two monomers carrying the index α as

| 5 |

For α < 0, b̂α measures the local bending of angles in the interior of the knot, while for α > 0, b̂α measures the local bending outside of the domain that was identified as knotted. The domain limits for α ∈ [αmin, αmax] depend on the instantaneous configuration, as the number of monomers on the knot NK determines how negative α can become. The range of α is constant, αmax – αmin + 1 = N/2.

We introduce a characteristic function χ̂α = 1 or 0 depending on whether the index α occurs for a given conformation or not and define the local bending difference between a knotted and a linear chain as

| 6 |

In eq 6, blinear(κ) ≡ 2Blinear(κ)/N is the thermodynamic average of the bending of two angles on a linear chain. It follows that

| 7 |

where M = N/2 is the smallest value guaranteeing [αmin, αmax] ⊂ [−M, M] for all polymer configurations.

5. Results

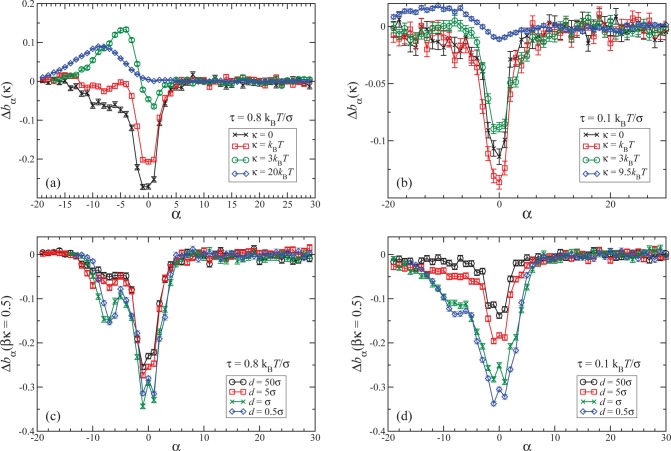

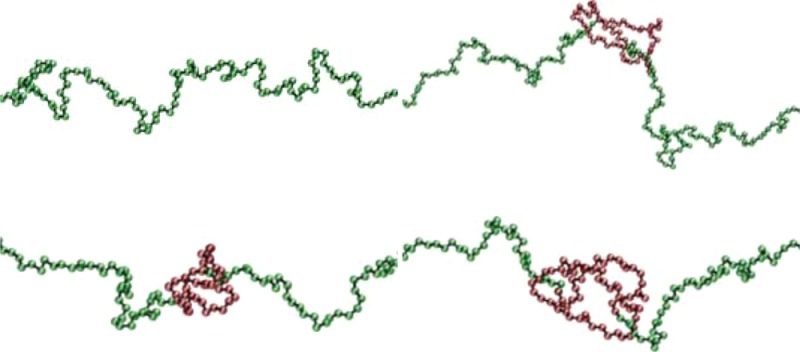

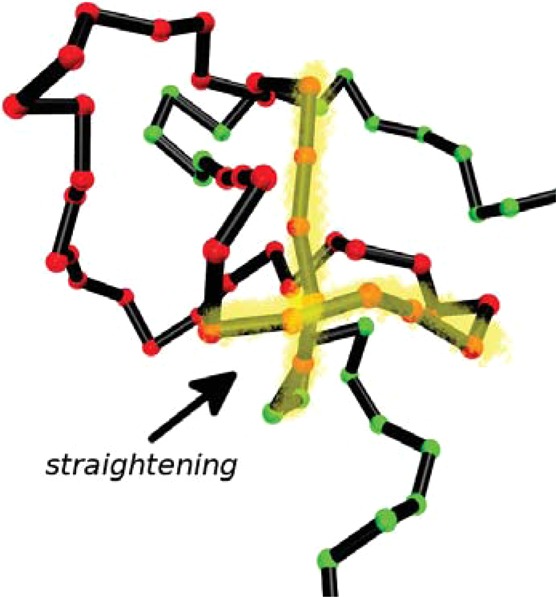

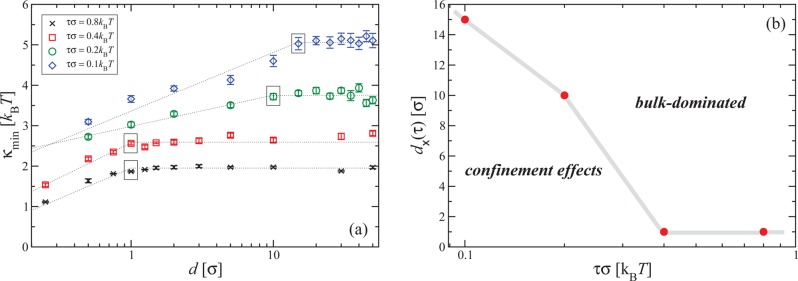

Results for the local bending of unconfined polymers are shown in Figures 1a,b for two different values of the applied tension. As can be seen, the quantity Δbα(κ) vanishes within less than 10 beads outside the knot; outside this region, a knotted chain hardly differs in its bending from an unknotted one. According to eqs 4 and 7, the area under the curves in Figures 1a,b determines the slope or Ψ(κ) at any κ value. The major negative contribution to ΔB(κ) for κ = 0 comes from a small number of monomers close to the knot ends, i.e., in the braiding region of the knot, in which monomers start getting into the knotted domain. The bending suppression is therefore related to the interaction of the different strands at the crossings, which effectively confines the strands and hence reduces their random bending. Thus, the negative slope of ΔFknotting(κ) at κ = 0 arises from this additional straightening of the knotted chain with respect to its flexible, unknotted counterpart. As ΔB(κ = 0), which is equal to the area under the respective curves in Figures 1a,b, is negative, a flexible knotted chain is, on average, less bent than its unknotted counterpart, contrary to the intuitive expectation that knotting inevitably increases the total bending of a polymer. In Figure 2 we show a simulation snapshot of the knotted domain of a flexible chain, in which the parts of the molecule that get “straightened out” due to the knot are highlighted. As κ grows, we eventually reach the intuitively expected regime in which knotting increases bending; see, e.g., the curve for κ = 20 kBT in Figure 1a, for which ΔB(κ) > 0.

Figure 1.

(a, b) Average local bending difference Δbα(κ) (see text) between knotted and linear unconfined polymers of different rigidities, as indicated in the legend. (c, d) The same quantity at fixed bending rigidity κ = 0.5 kBT for different degrees of slit confinement, as indicated in the legend. In panels a and c data for the tension τ = 0.8 kBT/σ are shown, while in panels b and d for τ = 0.1 kBT/σ.

Figure 2.

Simulation snapshot of the knotted domain of an unconfined, fully flexible polymer chain with a trefoil knot under the tension τ = 0.8 kBT/σ. The straightened-out segments in the vicinity of the strand crossings are highlighted.

Comparing the curves of Figures 1a,b, one sees that ΔB(κ) for κ = 0 is more negative for τ = 0.8 kBT/σ than for τ = 0.1 kBT/σ. This is due to the fact that at smaller τ the braid region is looser and the bending suppression due to the different strands at the crossings is reduced. On the contrary, if we increase κ, we arrive at a regime where ΔB(κ) is more negative for smaller tensions τ. At βκ = 3.0, ΔB is already positive for τ = 0.8 kBT/σ, due to the positive contribution of Δbα(κ) in the interior of the knot, which arises as the knot enforces the polymer to form a loop. The bending throughout a loop is larger if the loop is smaller. For τ = 0.1 kBT/σ the knot size is increased, which is the reason why the positive Δbα(κ) contribution in the interior of the knot is significantly smaller than for τ = 0.8 kBT/σ. Accordingly, for lower tensions the negative net result for ∂Ψ(κ)/∂κ persists for higher κ-values than for higher tensions. As can be seen in Figure 1b, we see a reversal of ∂Ψ(κ)/∂κ from negative to positive values only at a rigidity as high as βκ ≅ 9.

We now turn our attention to the confined case. It turns out that the effects of confinement are most transparent at a small, but nonzero, value of the bending rigidity; thus we show in Figures 1c,d results for Δbα(κ) for βκ = 0.5, which is characteristic for all values of κ ≤ κmin, the latter being the value of the rigidity for which Ψ(κ) attains its minimum value Ψmin. Here, striking differences between the tensions τ = 0.8 kBT/σ and τ = 0.1 kBT/σ show up. While for τ = 0.8 kBT/σ there is hardly any difference between the confined and unconfined polymers for slit widths as small as d = 5σ, for τ = 0.1 kBT/σ, confinement enhances Δbα at the beginning of the knot by almost a factor 2. For both tensions, the suppression of bending through knotting becomes even stronger as a result of the geometric constraints, and thus ΔB(κ) is more negative for the polymer in the slit than it is for the free polymer. This is consistent with the interpretation given above for the case of the unconfined polymer, since the slit confinement forces the strands at the braid region to come closer which further reduces the random bending in the braid region. This effect, however, is more pronounced for smaller tensions, where the braiding region without confinement is looser than for polymer chains under higher tensions.

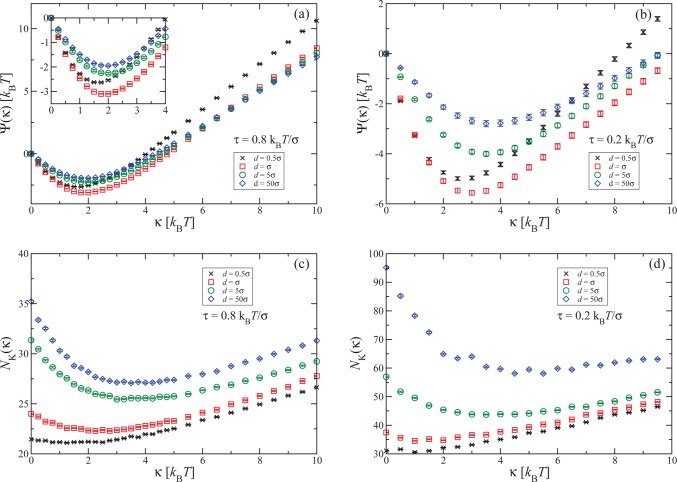

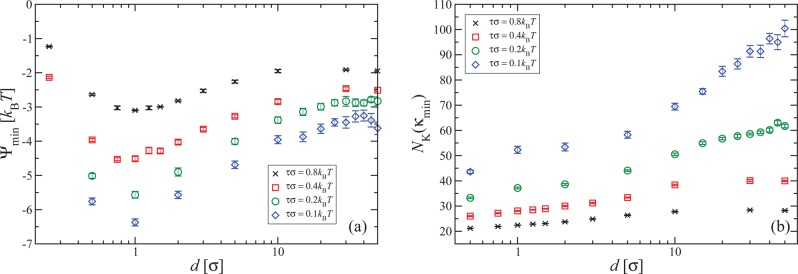

There exists a correlation between the slopes of Ψ(κ) and NK(κ) shown in Figure 3. In the high-κ domain,Ψ(κ) ∼ NK(κ) ∼ √κ, as is evident from the discussion following eq 4. For κ = 0, the knot is swollen due to the presence of steric interactions, maximizing in this way its entropy. However, for nonzero κ ∼ kBT, the fluctuations of the monomers are restricted in the first place, enabling thus a tighter braided region and a concomitant reduction of knot size. Thus, also for small κ the slopes of Ψ(κ) and NK(κ) are expected to have the same sign. Note, however, that the value κ̃ that minimizes NK(κ) does not coincide with κmin, e.g., for very strong confinements κmin ≠ 0, whereas κ̃ is, within simulation resolution, vanishingly small.

Figure 3.

(a, b) The quantity Ψ(κ) for different confinements, as indicated in the legend. The inset in (a) shows a zoom of the main panel in the region of the minimum of Ψ(κ). (c, d) Dependence of the number of monomers in the knot, NK(κ), on chain rigidity. In panels a and c results for the tension τ = 0.8 kBT/σ are shown, whereas in panels b and d the tension is τ = 0.2 kBT/σ.

The dependence of the rigidity κmin for which Ψ(κ) has its minimum on the degree of confinement for different applied tensions is summarized in Figure 4a. We find that for a tension of τσ = 0.8kBT κmin is only affected by confinement for slit widths lying at the monomer scale. In this regime of ultrastrong confinement, the energy cost that chain segments would have to pay to go one above the other in a gradual fashion at the braiding regions are too high. This is caused by the external potential, which assigns an increasingly high energetic cost for every monomer that deviates strongly from the y = 0-plane. Accordingly, it is preferable for the system to form localized “kinks” of one or two monomers in the braiding region, which expose a minimal number of monomers to the regions of high external potential, while at the same time creating strong bending there.

Figure 4.

(a) Dependence of the optimal value for the rigidity, κmin, on confinement for several applied tensions. The dotted lines are guides to the eye, delineating the two regimes where κmin is influenced by confinement, where κmin is d-dependent, and the bulk-dominated regime, where it is not. The crossover data points d×(τ) between the two regimes are marked with boxes. (b) Dependence of d×(τ) on the applied tension τ. The data points (red circles) are connected with thick gray segments, separating the bulk-dominated regime above the line by the confinement-affected regime below it.

The situation is quite different, however, for lower tensions. In this case, also a moderate confinement of the order of 10 bond lengths can significantly affect the value of κmin. To better quantify the effects of confinement, we employ a simple, rough-and-ready separation of the data points shown in Figure 4a into two groups: for high values of d, the points form plateaus at the bulk values of κmin, which we connect by horizontal lines. Through the other groups of points straight lines are drawn by hand, which intersect the horizontal ones at tension-dependent crossover confinement widths d×(τ). These values denote, by construction, the crossover of the behavior of κmin from bulk-dominated, for d > d×(τ), to confinement-affected, for d < d×(τ). The results are summarized in Figure 4b, where it can be seen that d×(τ) is significantly increased for lower tensions. As we discuss below, the reason the situation is strikingly different for lower tensions seems to be related to the fact that the knot size is then significantly increased with respect to higher tensions.

The increased effects of confinement as τ decreases are also manifested on the value of Ψmin as well as on the knot size NK(κmin). The former quantity is shown in Figure 5a and the latter in Figure 5b. As can be seen in Figure 5a, and in contrast to the values κmin itself, even in the case of higher tension the corresponding depth of the minimum Ψmin is influenced by a confining slit width of the order of 10 bond lengths. However, for lower tensions, the effect on Ψmin is felt at even larger slit widths. Furthermore, the difference between the value Ψmin in the bulk (d/σ ≫ 1) and the one for the optimal slit width is enhanced. The fact that the effect of the confinement on the knot size is more pronounced for smaller tensions, as shown in Figure 5b, correlates well with the finding that confinement shifts κmin to lower values for sufficiently small tensions. As we have seen in Figures 1a,b one of the contributions that eventually render ∂Ψ(κ)/∂κ positive is the bending in the interior of the knot, which arises as the knot enforces the polymer to form a loop. This contribution is larger for smaller knot sizes, and it is therefore consistent that κmin will be shifted by confinement if the latter is able to significantly reduce the knot size.

Figure 5.

(a) Dependence of Ψmin, the value of Ψ(κ) at the optimal rigidity κmin, on d, the slit-with of the confinement. (b) Knot size at the optimal rigidity as a function of d. Applied tensions as indicated in the legends.

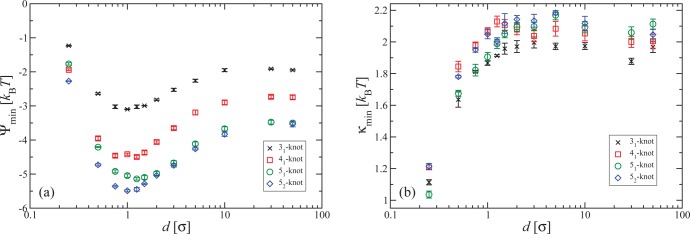

Up to now, all results have been derived for the simplest, trefoil knot; real polymers can, however, display a large variety of increasingly complex knots.25,26 Considering other knots allows us on the one hand to put the general character of our results to the test and also to corroborate our assertion that the crossings at the braiding region are responsible for the reduction of Ψ(κ) at finite κ-values. Indeed, more complex knots have more crossing points, where the strands of the polymer chain interact with each other. Thus, according to our analysis above, one should expect that a more complex knot will lead to lower values of ΔB(κ) and Ψmin for small but finite κ. Our findings for different knot topologies (denoted in the Alexander–Briggs notation27) are summarized in Figures 6a,b. The data in Figure 6a confirm that the main effect of the increased knot complexity is the addition of crossing points which all result in a similar bending suppression as the crossing points of the trefoil knot. Accordingly, for the knot topologies investigated, Ψmin is approximately proportional to the number of minimal crossings of the respective knot diagram, at least for confinements with d ≥ σ. It is also striking that for the unconfined case Ψmin is, within error bars, identical for the 51 and 52 topologies. A test of whether Ψmin is in good approximation proportional to the minimal number of crossings of arbitrarily complex knots is beyond the scope of this work. However, the number of strand crossings will increase with knot complexity. Accordingly, the free energy penalty for putting a knot on a stiff polymer (κ ≠ 0) can be much lower than the one for putting it on a fully flexible polymer (κ = 0), by amounts that grow with the knot complexity. Whereas Ψmin is sensitive to the knot type, κmin is not, as can be ascertained from the results shown in Figure 6b. All data fall within a narrow band of width Δκmin ≅ 0.2kBT irrespective of the knot topology.

Figure 6.

(a) Dependence of Ψmin on confinement for tension τ = 0.8 kBT/σ and different knot types, as indicated in the legend. (b) The corresponding optimal value of the rigidity κmin for different slit widths and knot types.

The tensions considered in our work are of the order of kBT/σ. At room temperature and a monomer length scale of 1 nm this corresponds to the pN scale. These tensions result in values of κmin ≈ 5 kBT. As it was found in previous work,1 without confinement κmin scales approximately as ∼τ–1/2. A reduction of the tension down to the fN scale, which is typical of double-stranded DNA molecules,28 will bring κmin at the order of 100 kBT. Our results imply that at these lower tensions the effect of confinement on κmin can be expected to be even more pronounced.

6. Conclusions

In summary, we have demonstrated that the local stretching at the braiding region and close to the crossing points is the physical mechanism responsible for the minimization of the free energy penalty of knotting of a linear polymer for nonvanishing values of the bending rigidity. Confinement can affect the location of the optimal rigidity for sufficiently low tensions, when it is at the same time significantly affecting the knot size. We therefore expect the geometrical reduction of dimensionality to become relevant for the location of the knots of chains with variable rigidity if the latter are under sufficiently small tensions. For tensions at the fN scale, which are typical of double-stranded DNA molecules,28 we therefore expect that confinement to strongly influence the value of the optimal rigidity. On the other hand, the amount of reduction of the knotting of free energy by rigidity strongly depends on the topology of the knot, and it increases with the knot complexity, scaling roughly with the number of minimal crossings of the knot. Accordingly, we anticipate that more complex knots will localize more strongly in the optimal regions of a chain than simpler ones. Recent advances in tying knots on polymers by optical tweezers29,30 and adsorbing them on mica surfaces15 should allow for experimental testing of our predictions.

Acknowledgments

This work has been supported by the Austrian Science Fund (FWF), Grant 23400-N16.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- Matthews R.; Louis A. A.; Likos C. N. ACS Macro Lett. 2012, 1, 1352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sogo J. M.; Stasiak A.; Martínobles M. L.; Krimer D. B.; Hernández P.; Schvartzman J. B. J. Mol. Biol. 1999, 286, 637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arsuaga J.; Vázquez M.; Trigueros S.; Sumners D. W.; Roca J. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2002, 99, 5373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Portugal J.; Rodrguez-Campos A. Nucleic Acids Res. 1996, 24, 4890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deibler R. W.; Mann J. K.; Sumners De Witt L.; Zechiedrich L. BMC Mol. Biol. 2007, 8, 44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z.; Deibler R. W.; Chan H. S.; Zechiedrich L. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009, 37, 661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogan M.; LeGrange J.; Austin B. Nature 1983, 304, 752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geggier S.; Vologodskii A. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2010, 107, 15421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson S.; Chen Y.-J.; Phillips R. PLoS One 2013, 8, e75799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rybenkov V. V. Science 1997, 277, 690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emanuel M.; Hamedani Radja N.; Henriksson A.; Schiessel H. Phys. Biol. 2009, 6, 025008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jun S.; Mulder B. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2006, 103, 12388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purohit P. K.; Inamdar M. M.; Grayson P. D.; Squires T. M.; Kondev J.; Phillips R. Biophys. J. 2005, 88, 851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orlandini E.; Stella A. L.; Vanderzande C. Phys. Biol. 2009, 6, 025012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ercolini E.; Valle F.; Adamcik J.; Witz G.; Metzler R.; de los Rios P.; Roca J.; Dietler G. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2007, 98, 058102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Micheletti C.; Orlandini E. Macromolecules 2012, 45, 2113. [Google Scholar]

- Matthews R.; Louis A. A.; Yeomans J. M. Mol. Phys. 2011, 109, 1289. [Google Scholar]

- Plimpton S. J. Comput. Phys. 1995, 117, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Tuckerman M. E.; Liu Y.; Ciccotti G.; Martyna G. J. J. Chem. Phys. 2001, 115, 1678. [Google Scholar]

- Rubinstein M.; Colby R.. Polymer Physics; Oxford University Press: Oxford, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Gallotti R.; Pierre-Louis O. Phys. Rev. E 2007, 75, 031801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tubiana L.; Orlandini E.; Micheletti C. Prog. Theor. Phys. Suppl. 2011, 191, 192. [Google Scholar]

- Marcone B.; Orlandini E.; Stella A. L.; Zonta F. Phys. Rev. E 2007, 75, 041105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcone B.; Orlandini E.; Stella A. L.; Zonta F. J. Phys. A: Math. Gen. 2005, 38, L15. [Google Scholar]

- Koniaris K.; Muthukumar M. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1991, 66, 2211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rawdon E.; Dobay A.; Kern J. C.; Millett K. C.; Piatek M.; Plunkett P.; Stasiak A. Macromolecules 2008, 41, 4444. [Google Scholar]

- Livingston C.Knot Theory; Carus Monographs; Mathematical Association of America: Washington, DC, 1993; Vol. 24. [Google Scholar]

- Gutjahr P.; Lipowsky R.; Kierfeld J. Europhys. Lett. 2006, 76, 994. [Google Scholar]

- Arai Y.; Yasuda R.; Akashi K.; Harada Y.; Miyata H.; Kinoshita K. Jr.; Itoh H. Nature 1999, 399, 446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bao X. R.; Lee H. J.; Quake S. R. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2003, 91, 265506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]