Abstract

Background

Mechanical unloading of the failing human heart induces profound cardiac changes resulting in the reversal of a distorted structure and function. In this process, cardiomyocytes break down unneeded proteins and replace those with new ones. The specificity of protein degradation via the ubiquitin proteasome system is regulated by ubiquitin ligases. Over-expressing the ubiquitin ligase MAFbx/Atrogin-1 in the heart inhibits the development of cardiac hypertrophy, but the role of MAFbx/Atrogin-1 in the unloaded heart is not known.

Methods and Results

Mechanical unloading, by heterotopic transplantation, decreased heart weight and cardiomyocyte cross-sectional area in wild type mouse hearts. Unexpectedly, MAFbx/Atrogin-1−/− hearts hypertrophied after transplantation (n=8–10). Proteasome activity and markers of autophagy were increased to the same extent in WT and MAFbx/Atrogin-1−/− hearts after transplantation (unloading). Calcineurin, a regulator of cardiac hypertrophy, was only upregulated in MAFbx/Atrogin-1−/− transplanted hearts, while the mTOR pathway was similarly activated in unloaded WT and MAFbx/Atrogin-1−/− hearts. MAFbx/Atrogin-1−/− cardiomyocytes exhibited increased calcineurin protein expression, NFAT transcriptional activity, and protein synthesis rates, while inhibition of calcineurin normalized NFAT activity and protein synthesis. Lastly, mechanical unloading of failing human hearts with a left ventricular assist device (n=18) also increased MAFbx/Atrogin-1 protein levels and expression of NFAT regulated genes.

Conclusions

MAFbx/Atrogin-1 is required for atrophic remodeling of the heart. During unloading, MAFbx/Atrogin-1 represses calcineurin-induced cardiac hypertrophy. Therefore, MAFbx/Atrogin-1 not only regulates protein degradation, but also reduces protein synthesis, exerting a dual role in regulating cardiac mass.

Keywords: MAFbx/Atrogin-1, atrophic remodeling, heterotopic heart transplantation, protein turnover, heart assist device

1. Introduction

Mechanical unloading of the failing human heart induces profound cardiac changes resulting in the reversal of a distorted structure and function [1–3]. In heart failure patients fitted with a left ventricular assist device (LVAD), and in hemodynamically unloaded rodent hearts, pathways of protein synthesis and degradation are activated simultaneously [4, 5]. A more complete understanding of this self-renewal of heart muscle cells should therefore be of clinical importance.

Protein turnover is the net result of protein synthesis and protein degradation, and ultimately controls cardiomyocyte size. Signaling pathways regulating protein synthesis have been studied in detail, particularly during conditions that lead to cardiac hypertrophy [6]. Surprisingly, activation of protein synthesis is also a feature of cardiac atrophy [4]. While pathways of protein degradation in the heart are the focus of several recent investigations [7, 8], it is not known to what extent these pathways regulate atrophic remodeling of the unloaded heart. More importantly, it is not known why atrophic remodeling in the failing heart can result in improved function.

The importance of protein degradation in the heart has been recognized for some time [9], but only lately specific proteolytic systems have been investigated in detail. Much of what is known about protein degradation in the heart originates from studies in skeletal muscle. The two main pathways regulating protein degradation in muscle are the ubiquitin proteasome system (UPS) and autophagy [10–12], and both pathways are precisely controlled. The UPS is regulated at several different steps, the most critical being the ubiquitination of target proteins by ubiquitin ligases [13].

Ubiquitin ligases are essential in regulating protein degradation in muscle. The muscle-specific ligases atrophy F-box protein (MAFbx) [14], also known as Atrogin-1 [15], and Muscle RING finger protein 1 (MuRF1) were originally identified by their transient upregulation during skeletal muscle atrophy. Mice lacking MAFbx/Atrogin-1 and MuRF1 are resistant to denervation-induced skeletal muscle atrophy while overexpression of MAFbx/Atrogin-1 in myotubes induces atrophy [14]. MAFbx/Atrogin-1 and MuRF1 are transcriptionally upregulated in various models of skeletal muscle atrophy including hindlimb suspension, immobilization, denervation, cancer, diabetes, fasting, and renal failure [14, 15]. Many investigations have focused on the transcriptional regulation of the ligases in muscle, and the pathways that are involved in this process. Main pathways include PI3kinase-Akt, p38, and p300, all of which converge on Foxo transcription factors [16].

As in skeletal muscle, Foxo transcription factors, which are activated during atrophic remodeling of the heart [17], regulate cardiac expression of MAFbx/Atrogin-1 and MuRF1 [18]. Although much less attention has been given to the ligases in the heart, the following is already known. Overexpression of MAFbx/Atrogin-1 in the heart reduces physiologic and pathologic cardiac hypertrophy in vivo [19, 20]. MuRF1 overexpression in cardiomyocytes prevents hypertrophy in vitro [21], and mice deficient in MuRF1 develop enhanced cardiac hypertrophy in response to pressure overload [22]. Additionally, MuRF1 is required for the reversal of cardiac hypertrophy [23]. These studies establish the importance of ubiquitin ligases in regulating cardiac hypertrophy; however, the role of MAFbx/Atrogin-1 and MuRF1 in regulating atrophic remodeling of the heart has not yet been investigated.

In the current study, we examine the role of MAFbx/Atrogin-1 and MuRF1 in mechanical unloading of the heterotopically transplanted heart. We demonstrate that MuRF1 is dispensable for mechanical unloading-induced cardiac atrophy. Unexpectedly, MAFbx/Atrogin-1−/− hearts are not only resistant to mechanical unloading-induced atrophy, but they also hypertrophy in response to a decreased load. Protein degradation was not significantly altered in transplanted (unloaded) MAFbx/Atrogin-1−/− hearts, however protein synthesis rates were drastically elevated in MAFbx/Atrogin-1−/− cardiomyocytes. Further investigation into the mechanism behind this phenomenon revealed that calcineurin protein levels and NFAT activity were significantly increased in MAFbx/Atrogin-1−/− cardiomyocytes. Enhanced protein synthesis in MAFbx/Atrogin-1−/− cardiomyocytes resulted in hypertrophy, while inhibition of calcineurin restored protein synthesis rates to normal. The MAFbx/Atrogin-1- calcineurin axis is also regulated in failing hearts unloaded with a left ventricular assist device. The results of our animal studies are replicated in the failing human heart. We show that MAFbx/Atrogin-1 is required for atrophic remodeling of the unloaded heart by keeping protein synthesis in check, and suggest that MAFbx/Atrogin-1 expression aids in the process of reverse remodeling of the failing heart induced by mechanical unloading.

2. Methods

An expanded Methods section is available in the Data Supplement.

2.1. Experimental Animals

MAFbx/Atrogin-1−/−, MuRF1−/−, and respective WT littermate male mice (8–10 weeks old), were used for in vivo unloading experiments (heterotopic transplantation of the heart) and for the isolation of adult cardiomyocytes. Experiments involving the use of animals were approved by the IACUC of The University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston.

2.2. Heterotopic Transplantation of the Mouse Heart

Unloading of the heart was induced by isogenic heterotopic transplantation of mouse hearts as described previously and in further detail in the Data Supplement [24].

2.3. Cell Culture

Adult mouse cardiomyocytes isolated from hearts of MAFbx/Atrogin-1−/− mice and their WT littermates were used for the pulse chase experiments and immunocytochemistry, explained in detail in the Data Supplement.

2.4. Human subjects

Paired cardiac tissue samples were obtained from 18 patients (ranging in age from 43–67 years) with idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy (16 males, 2 females) referred to the Texas Heart Institute for heart transplantation and placed on left ventricular assist device (LVAD) support for a mean duration of 123±20 days. Tissue from the left ventricular apex was obtained during LVAD implantation and again during LVAD explantation or at the time of death. Tissue samples were immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C for molecular analyses. Human subjects gave informed consent and the study protocol was approved by the Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects of St. Luke’s Episcopal Hospital in Houston, Texas, and by The University of Texas Medical School at Houston.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Results are expressed as means ± SEM. Analysis was performed using two-tailed, unpaired Student’s t-test or one-way ANOVA with Tukey post hoc test. A value of P<0.05 was considered significant.

3. Results

3.1. MAFbx/Atrogin-1, not MuRF1, is required for atrophic remodeling of the heart

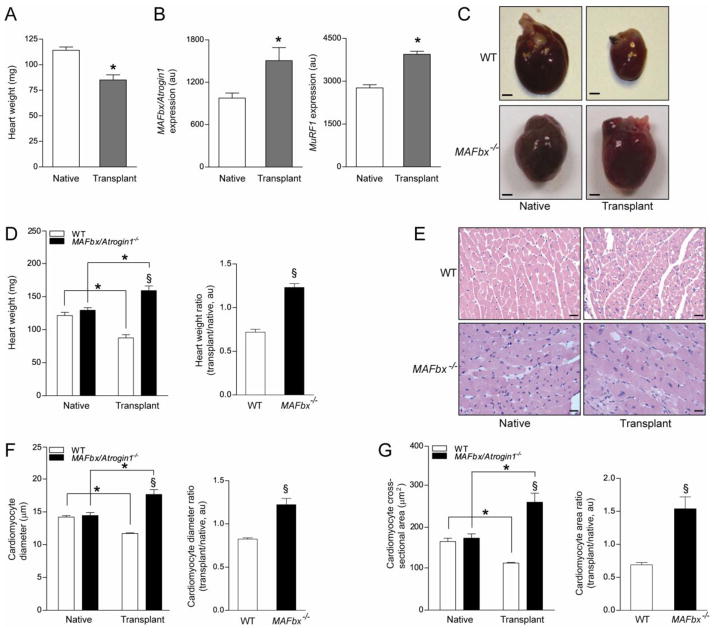

The ubiquitin ligases MAFbx/Atrogin-1 and MuRF1 are critical regulators of skeletal muscle size and mass [14, 15]. Expression of both ligases increases with muscle unloading and the absence of either ligase suppresses unloading-induced skeletal muscle atrophy [14]. Although protein degradation pathways in skeletal muscle and in the heart are thought to be the same, it is not clear if they are similarly regulated. Therefore we first determined whether unloading of the mouse heart increased MAFbx/Atrogin-1 and MuRF1 expression. Heterotopic transplantation in isogenic animals causes mechanical unloading of the heart and is a model of cardiac atrophy [25, 26]. In wild type (WT) mice, mechanical unloading of the heart induces cardiac atrophy after seven days, as demonstrated by a significant decrease in heart weight (Figure 1A). The expression of MAFbx/Atrogin-1 and MuRF1 was increased in the transplanted heart after mechanical unloading (Figure 1B). These results suggest that, as in skeletal muscle, the ubiquitin ligases MAFbx/Atrogin-1 and MuRF1 may also be important regulators of protein degradation during atrophic remodeling of the heart.

Figure 1.

MAFbx/Atrogin-1 is required for atrophy during unloading of the heart by heterotopic transplantation. (A–B) Male wild type (WT) mice, ages 8–10 weeks, were subjected to heterotopic transplantation of the heart for 7 days (n = 5 per condition). (A) Heart weights of native and transplanted (unloaded) WT hearts. (B) MAFbx/Atrogin-1 and MuRF1 gene expression in native and transplanted (unloaded) WT hearts. (C–F) Male WT and MAFbx/Atrogin-1−/− littermate mice, ages 8–10 weeks, were subjected to isogenic heterotopic transplantation of the heart for 7 days (n = 8–10 per genotype and condition). (C) Representative native and transplanted (unloaded) hearts from WT and MAFbx/Atrogin-1−/− littermate mice. Scale bar: 1mm. (D) Heart weights and ratio of transplanted (unloaded) to native hearts. (E) Representative H&E staining of native and transplanted (unloaded) hearts from WT and MAFbx/Atrogin-1−/− littermate mice. Note the dense, small nuclei in the transplanted (unloaded), atrophied WT heart and the more sparsely distributed, large nuclei in the transplanted (unloaded) MAFbx/Atrogin-1−/− heart which is hypertrophied. Scale bar: 25μm. (F) Myocyte diameter and ratio, and (G) myocyte cross-sectional area and ratio of transplanted (unloaded) to native hearts. Data are mean ± SEM of 5–10 mice per condition. *P < 0.01 versus respective native. § P < 0.01 versus WT or WT transplanted (unloaded).

To test the hypothesis that MAFbx/Atrogin-1 and MuRF1 are required for atrophic remodeling of the mechanically unloaded heart we subjected WT, MAFbx/Atrogin-1−/−, and MuRF1−/− littermate mice to isogenic heterotopic transplantation [25, 26]. Surprisingly, MuRF1−/− hearts atrophied to the same extent as WT hearts after seven days of transplantation (unloading) (Supplemental Figure 1). The heart weight, myocyte diameter, and myocyte cross sectional area of MuRF1−/− transplanted (unloaded) hearts did not significantly differ from WT transplanted (unloaded) hearts (Supplemental Figure 1B–D). These data demonstrate that MuRF1 is not required for mechanical unloading-induced cardiac atrophy. Even more surprising was the response of MAFbx/Atrogin-1−/− hearts to heterotopic transplantation (unloading): MAFbx/Atrogin-1 deficient hearts hypertrophied seven days after transplantation (unloading) (Figure 1C). Heart weight (Figure 1D) and cardiomyocyte diameter as well as cross sectional area (Figure 1E–G) of MAFbx/Atrogin-1−/− transplanted (unloaded) hearts were significantly greater than WT transplanted (unloaded) hearts. These experiments reveal that MAFbx/Atrogin-1 is not only required for mechanical unloading-induced atrophy, but also that MAFbx/Atrogin-1 prevents cardiac hypertrophy, even under conditions of reduced load.

3.2. Protein degradation is not inhibited in MAFbx/Atrogin-1 deficient hearts

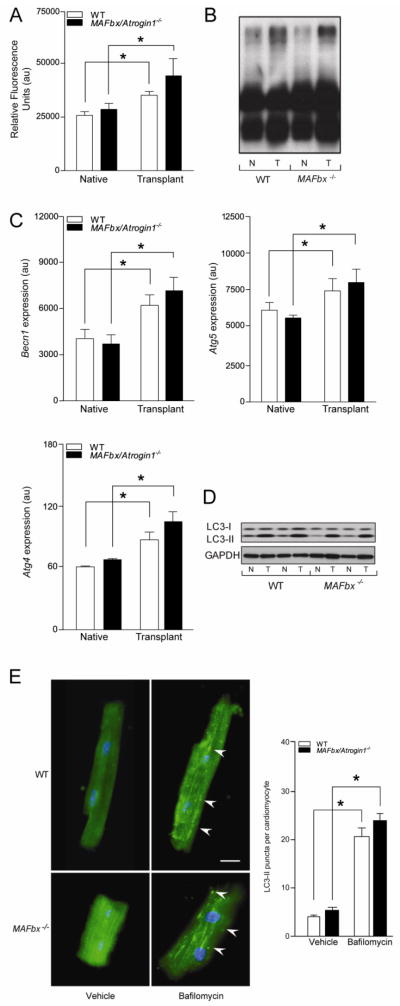

The concept that cardiac hypertrophy could occur in the absence of a load seems counterintuitive. However, it is conceivable that MAFbx/Atrogin-1 is required for protein degradation in the heart during unloading. Consequently, the absence of MAFbx/Atrogin-1 could lead to decreased protein degradation and enlarged cardiomyocytes. To examine this possibility we quantified proteasome activity in WT and MAFbx/Atrogin-1−/− native and transplanted (unloaded) hearts. Cardiac proteasome activity, specifically chymotryptic activity, was increased to the same degree in WT and MAFbx/Atrogin-1−/− hearts after transplantation (unloading) (Figure 2A). Furthermore, the amount of ubiquitinated proteins was similar in WT and MAFbx/Atrogin-1−/− hearts (Figure 2B). These data suggest that altered UPS-mediated protein degradation is not the cause of hypertrophy in mechanically unloaded MAFbx/Atrogin-1−/− hearts.

Figure 2.

Proteasome activity and autophagy markers are increased in the transplanted (unloaded) heart. (A–D) Native and transplanted (unloaded) hearts from the WT and MAFbx/Atrogin-1−/− male mice described in Figure 1. (A) Proteasome (chymotryptic) activity and (B) polyubiquitinated proteins in native and transplanted (unloaded) WT and MAFbx/Atrogin-1−/− hearts. (C) mRNA expression of Becn1, Atg5, and Atg4, and (D) LC3-I and LC3-II protein levels in native and transplanted (unloaded) hearts. (E) Immunocytochemistry was performed on cardiomyocytes isolated from male WT and MAFbx/Atrogin-1−/− hearts (mice ages 8–10 weeks old) treated with Bafilomycin A. Arrowheads indicate examples of LC3-II puncta, representing autophagic vacuoles. Scale bar: 25μm. Quantification of LC3-II puncta is shown in the graph. Data are mean ± SEM. n = 8–10 per group (A–D) and n = 150–200 cells per condition (E). *P < 0.01 versus respective native or vehicle. N = native, T = transplanted (unloaded).

We next examined markers of autophagy to determine whether autophagy-mediated protein degradation was differentially affected by mechanical unloading. As demonstrated in skeletal muscle atrophy [27], markers of the entire process of autophagy were upregulated at the mRNA level after transplantation (unloading) of the heart (Figure 2C). Beclin-1 (Becn1), also known as autophagy-related gene (Atg) 6, is one of the proteins involved in the induction of autophagy [28], and was significantly increased in both WT and MAFbx/Atrogin-1−/− transplanted (unloaded) hearts (Figure 2C). Atg5 forms a complex with Atg12 to expand the autophagic membrane, and is often called a rate-limiting step in autophagy [8]. Atg5 was also increased in both WT and MAFbx/Atrogin-1−/− transplanted (unloaded) hearts (Figure 2C). The expression of Atg4, the cysteine protease that cleaves LC3 to LC3-I [28], was also increased in WT and MAFbx/Atrogin-1−/− transplanted (unloaded) hearts (Figure 2C). Furthermore, LC3-II, the lipidated form of LC3-I, and an indicator of autophagosome abundance [8], was significantly increased in both WT and MAFbx/Atrogin-1−/− transplanted (unloaded) hearts (Figure 2D). These data demonstrate that autophagy is similarly regulated in WT and MAFbx/Atrogin-1−/− unloaded hearts.

To determine whether the absence of MAFbx/Atrogin-1−/− changes the dynamics of autophagy, we performed autophagic flux assays. Cardiomyocytes isolated from WT and MAFbx/Atrogin-1−/− hearts were treated with Bafilomycin A. Bafilomycin A inhibits the vacuolar ATPase, blocking fusion of autophagosomes with lysosomes, leading to an accumulation of autophagosomal structures [29]. Like the expression of autophagy markers and the protein levels of LC3-I and LC3-II in the transplanted heart, there was no significant difference in autophagic puncta in isolated cardiomyocytes from WT and MAFbx/Atrogin-1−/− mice (Figure 2E). These data demonstrate that the capacity of proteasome- and autophagy-mediated protein degradation is not decreased, but it is rather increased when the heart is mechanically unloaded. Furthermore, the absence of MAFbx/Atrogin-1 in the heart does not affect protein degradation during mechanical unloading of the heart.

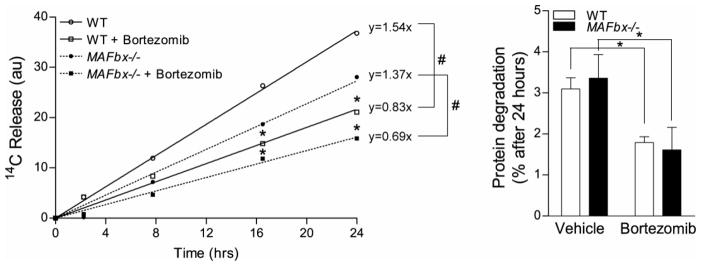

To further investigate the role of protein degradation in MAFbx/Atrogin-1−/− hearts in real time, we next measured protein degradation in isolated adult mouse cardiomyocytes. Although we already demonstrated that proteasome activity and markers of autophagy are increased in both WT and MAFbx/Atrogin-1−/− transplanted (unloaded) hearts (Figures 2), we assessed rates of protein degradation as an accurate measurement of flux in cardiomyocytes [30]. Pulse-chase experiments allow for the calculation of protein degradation rates, designated by the amount of 14C released over time, and the values are given next to each regression line. These experiments demonstrate that WT and MAFbx/Atrogin-1−/− cardiomyocytes degrade proteins at similar rates, and linear regression analysis revealed that this was not statistically significant (P=0.095) (Figure 3, line graph). Furthermore, the percentage of protein degradation was not significantly changed in MAFbx/Atrogin-1−/− after 24 hours (Figure 3, bar graph). Additionally, WT and MAFbx/Atrogin-1−/− cardiomyocytes were responsive to the proteasome inhibitor Bortezomib to a similar extent (Figure 3). Thus, in agreement with proteasome and autophagy data (Figure 2), there was no significant difference in protein degradation in WT and MAFbx/Atrogin-1−/− cardiomyocytes. Therefore, MAFbx/Atrogin-1−/− hearts do not hypertrophy in response to transplantation (unloading) due to decreased protein degradation.

Figure 3.

Protein degradation rates are not changed in MAFbx/Atrogin-1−/− cardiomyocytes. Cardiomyocytes were isolated from male WT and MAFbx/Atrogin-1−/− hearts (mice ages 8–10 weeks old) by Langendorff perfusion of enzyme-containing buffer. For protein degradation measurements, isolated myocytes were incubated for 24 hours with [14C]-phenylalanine (pulse), media was changed to contain unlabeled phenylalanine (chase), and release of [14C]-phenylalanine into the media was determined over time. Data are mean ± SEM. n = 3 independent experiments, 4–6 replicates per condition. *P < 0.01 versus respective control at the respective time points. # P<0.001linear regression of protein degradation rates.

3.3. Pathways of protein synthesis are activated in MAFbx/Atrogin-1 deficient hearts

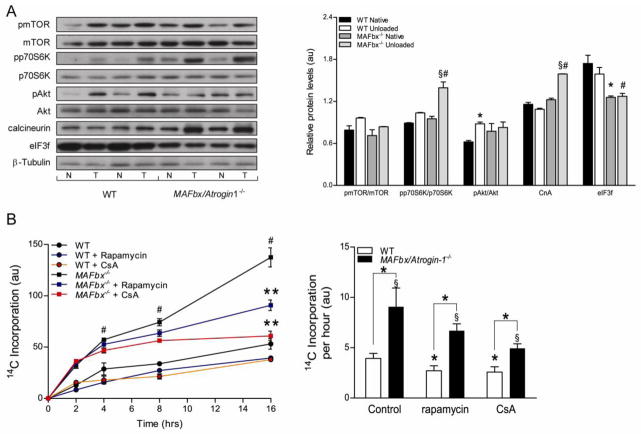

Cardiac hypertrophy is accompanied by an increase in protein synthesis via upregulation of many different pathways [6, 31]. We determined whether these pathways were activated in the absence of MAFbx/Atrogin-1 in the transplanted (unloaded) heart. Mammalian Target of Rapamycin (mTOR) and Akt are known regulators of protein synthesis, but neither protein was significantly activated in MAFbx/Atrogin-1−/− hearts after transplantation. Interestingly, phosphorylation of p70S6K (Thr389), was increased to the same extent after transplantation (unloading) in both WT and MAFbx/Atrogin-1−/− hearts (Figure 4A). Hormones and growth factors lead to phosphorylation of p70S6K at this sight independent of mTOR and Akt, supporting our previous findings that growth factors signaling through the PI3K pathway regulate metabolic changes in the unloaded heart [32]. Protein levels of calcineurin A (CnA), a known target of MAFbx/Atrogin-1 and a mediator of cardiac hypertrophy, were significantly increased in MAFbx/Atrogin-1−/− hearts after transplantation (Figure 4A). These data suggest that calcineurin-mediated protein synthesis contributes to increased cardiomyocyte size observed with mechanical unloading in the absence of MAFbx/Atrogin-1.

Figure 4.

Protein synthesis is increased in MAFbx/Atrogin-1 deficient cardiomyocytes, and is regulated by calcineurin. (A) Signaling pathways of protein synthesis are increased in the transplanted (unloaded) heart. Representative western blot analysis for mTOR, p70S6K, Akt and their respective phosphorylation status, in addition to eukaryotic initiation factor 3f (eIF3f) and calcineurin in native and transplanted (unloaded) WT and MAFbx/Atrogin-1−/− hearts. Data are mean ± SEM. n = 8–10 per group. *P < 0.05 versus WT Native. § P < 0.05 versus MAFbx/Atrogin-1−/− Native. #P < 0.05 versus WT transplanted (unloaded). CnA = calcineurin A, N = native, T = transplanted (unloaded). (B) Protein synthesis in WT and MAFbx/Atrogin-1−/− cardiomyocytes in control conditions and with inhibition of calcineurin or mTOR. For protein synthesis measurements, isolated myocytes were incubated with [14C]-phenylalanine and the incorporation of [14C]-phenylalanine into proteins was determined over time. Data are mean ± SEM. n = 3 independent experiments, 4–6 replicates per condition. # P < 0.01 versus all respective WT conditions at the respective time points. **P < 0.01 versus MAFbx/Atrogin-1−/− vehicle or treated at 16 hours. *P < 0.01 versus respective control or WT. § P < 0.05 versus MAFbx/Atrogin-1−/− Native. CsA = cyclosporine A.

Several studies in skeletal muscle have demonstrated that the eukaryotic initiation factor 3f (eIF3f) is regulated by MAFbx/Atrogin-1, and overexpression of MAFbx/Atrogin-1 decreases muscle cell size in part through degrading eIF3f [33]. Although it is not known whether MAFbx/Atrogin-1 regulates eIF3f in the heart, protein levels of eIF3f were significantly lower at baseline in MAFbx/Atrogin-1−/− native hearts, and did not significantly change in the transplanted heart (Figure 3). These data suggest that MAFbx/Atrogin-1 may not regulate eIF3f in the heart. Taken together, the results imply that protein synthesis is increased in the transplanted heart, and provide further support to our earlier findings in rat heart [4].

3.4. Calcineurin regulates protein synthesis in MAFbx/Atrogin-1−/− cardiomyocytes

To directly investigate protein synthesis in MAFbx/Atrogin-1−/− hearts, we measured [14C]-phenylalanine incorporation in isolated adult mouse cardiomyocytes. Rates of protein synthesis were more than two-fold higher in MAFbx/Atrogin-1−/− cardiomyocytes compared to WT cardiomyocytes (Figure 4B). These data show that after transplantation (unloading), in the absence of MAFbx/Atrogin-1, enhanced protein synthesis contributes to cardiomyocyte hypertrophy.

To determine the mechanism whereby protein synthesis was increased in the absence of MAFbx/Atrogin-1, we measured rates of protein synthesis in the presence of several inhibitors. Because the mTOR pathway and calcineurin were activated in the MAFbx/Atrogin-1 deficient hearts with mechanical unloading (Figure 4A), we reasoned that inhibition of mTOR or calcineurin would decrease protein synthesis in MAFbx/Atrogin-1−/− cardiomyocytes. We quantified protein synthesis in WT and MAFbx/Atrogin-1−/− cardiomyocytes in the presence of rapamycin, an inhibitor of mTOR, or cyclosporine A (CsA), a calcineurin inhibitor. Rates of protein synthesis were decreased to the same extent with cyclosporine A or rapamycin treatment in WT cardiomyocytes (Figure 4B). Rates of protein synthesis were also decreased with rapamycin treatment in MAFbx/Atrogin-1−/− cardiomyocytes, but further decreased with cyclosporine A treatment (Figure 4B). More importantly, cyclosporin A restored rates of protein synthesis in MAFbx/Atrogin-1−/− cardiomyocytes nearly to rates observed in WT cardiomyocytes. Thus, while mTOR contributes to protein synthesis, calcineurin is the main regulator of protein synthesis in MAFbx/Atrogin-1−/− cardiomyocytes.

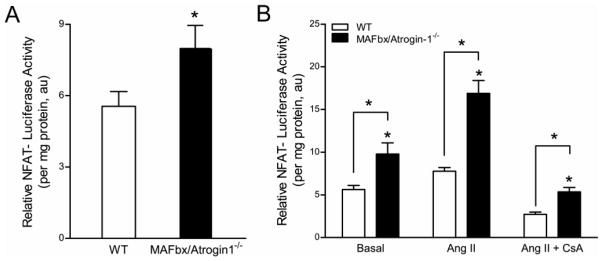

We further validated the role of calcineurin in MAFbx/Atrogin-1−/− cardiomyocytes. Calcineurin directly activates nuclear factor of activated T-cells (NFAT) transcriptional activity [34]. Thus, we utilized an NFAT-luciferase reporter assay [35] as a readout for calcineurin activity in WT and MAFbx/Atrogin-1−/− cardiomyocytes at baseline and in response to stress. NFAT transcriptional activity, indicative of calcineurin activity, was increased in MAFbx/Atrogin-1−/− cardiomyocytes (Figure 5). Furthermore, NFAT activity was increased in MAFbx/Atrogin-1 deficient cardiomyocytes in response to angiotensin (AngII) treatment, and was normalized with calcineurin inhibition (Figure 5). The results provide additional evidence that calcineurin indeed plays a role in enhanced protein synthesis in MAFbx/Atrogin-1−/− cardiomyocytes, which ultimately leads to cardiac hypertrophy in response to transplantation (unloading).

Figure 5.

Calcineurin activity is increased in MAFbx/Atrogin-1 deficient cardiomyocytes. (A–B) Cardiomyocytes were isolated from male WT and MAFbx/Atrogin-1−/− hearts (mice ages 8–10 weeks old) and infected with NFAT-luciferase reporter adenovirus. In separate experiments infected myocytes were treated with angiotensin II and cyclosporine A. (A) NFAT-luciferase activity in isolated adult cardiomyocytes from WT and MAFbx/Atrogin-1−/− mice. (B) NFAT-luciferase activity in cardiomyocytes in response to stimulation. Data are mean ± SEM. n = 3 independent experiments, 7–9 replicates per condition. *P < 0.05 versus respective WT. AngII = angiotensin II; CsA = cyclosporin A.

MAFbx/Atrogin-1 inactivation does not provoke a phenotype under basal conditions. Thus, we sought to determine why mechanical unloading is required to elicit a hypertrophic response in MAFbx/Atrogin-1−/− mice. Our data suggests that not only is the expression of calcineurin higher in the unloaded hearts, but its activity is increased as well (Figure 5). We have previously shown that MAFbx/Atrogin-1 is upregulated in the hypoxic heart [36]. Similarly, calcineurin is known to be activated under hypoxic conditions [37–39]. It is possible that the unloaded heart is hypoxic due to low-flow ischemia. Indeed, we found that hypoxia inducible factor-1α (Hif1α) and its known target glucose transporter 1 (GLUT1) were upregulated in the MAFbx/Atrogin-1−/− transplanted hearts (Supplemental Figure 2A). These results provide further evidence that MAFbx/Atrogin-1 is an important regulator of calcineurin in the unloaded heart. We speculate that the activation of calcineurin in a hypoxic environment and in the absence of Atrogin-1 contributes to enhanced protein synthesis, ultimately resulting in cardiac hypertrophy.

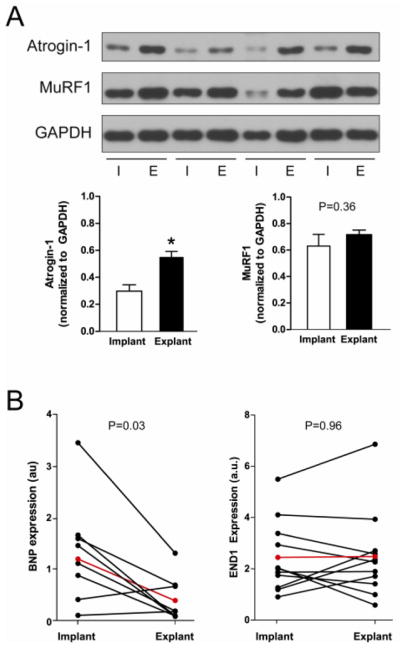

3.5. The MAFbx/Atrogin-1−/−- calcineurin axis is regulated in the mechanically unloaded failing human heart

To determine the clinical relevance of our findings we investigated the role of ubiquitin ligases, and specifically MAFbx/Atrogin-1- calcineurin, in the mechanically unloaded human heart. Heart biopsies were obtained from human patients diagnosed with idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy of unknown genetic cause, both at time of left ventricular assist device placement (implantation; I), and removal (explantation; E). We discovered that MAFbx/Atrogin-1 protein levels were increased in the mechanically unloaded human heart, while MuRF1 protein levels didn’t significantly change (Figure 6A). The human data supports our mouse model data in that hearts in MuRF1−/− mice were not affected by unloading (Supplemental Figure 1). Furthermore, the expression of brain natriuretic peptide (BNP), an NFAT regulated gene, was decreased after unloading, (Figure 6B), indicating that calcineurin-mediated hypertrophic signaling through NFAT is decreased in the unloaded human heart. Another NFAT regulated gene, endothelin-1 (END1), trended to decrease after unloading; however, END1 expression was rather variable within the paired human samples. This is not surprising, given that END1 is regulated by many other transcription factors in addition to NFAT, such as NF-κB, Smad, and FOXO [40]. Similar to the transplanted mouse hearts, we found that Hif1α and its downstream target GLUT1 also trended to increase in the unloaded hearts, although this was not significant (Supplemental Figure 2B). These data suggest that the same signaling axes in the mouse and human heart regulate protein turnover in response to mechanical unloading, and collectively, our results indicate that MAFbx/Atrogin-1 is necessary for mechanical unloading-induced cardiac atrophy.

Figure 6.

MAFbx/Atrogin-1 is increased in mechanically unloaded human hearts. (A) Protein expression and quantification at time of left ventricular assist device (LVAD) implantation (I) and explantation (E) in human patients diagnosed with idiopathic cardiomyopathy. Data are representative of n=11–13 paired human heart samples. (B) NFAT-regulated gene expression in human patients before and after LVAD placement. The red line indicates the average gene expression of implant and explant samples. BNP = brain natriuretic peptide. END1 = endothelin1.

4. Discussion

We used heterotopic transplantation of the mouse heart as a model of mechanical unloading to investigate the role of MAFbx/Atrogin-1 in atrophic remodeling of the unloaded heart. Using this model we have previously demonstrated that energy substrate metabolism [24, 32] as well as protein synthesis and degradation [4, 6, 41] are altered in the heart in response to transplantation (unloading). We now provide strong evidence showing that MAFbx/Atrogin-1 is required for atrophic remodeling of the mechanically unloaded heart. The absence of MAFbx/Atrogin-1 in cardiomyocytes paradoxically increased rates of protein synthesis, resulting in hypertrophy in response to mechanical unloading. We demonstrate that calcineurin is responsible for enhanced protein synthesis and that inhibition of calcineurin restores protein synthesis rates in MAFbx/Atrogin-1−/− cardiomyocytes to normal. Further, we propose that calcineurin is activated by hypoxia in the unloaded heart. For this reason, MAFbx/Atrogin-1−/− hearts do not hypertrophy under basal conditions.

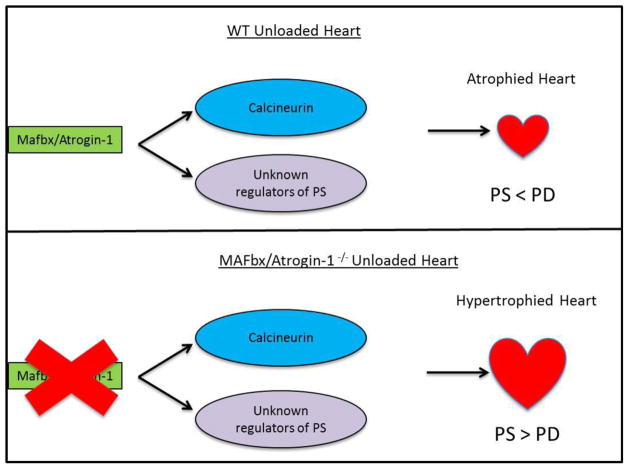

We also provide evidence that MAFbx/Atrogin-1 plays a role in mechanical unloading of the failing human heart. After LVAD placement, MAFbx/Atrogin-1 protein levels are significantly increased in the human heart. Consequently, calcineurin-mediated NFAT activity is decreased. These data support our previous findings that protein turnover is enhanced in the unloaded human heart [3, 36]. Thus, MAFbx/Atrogin-1 regulates protein homeostasis in the transplanted (unloaded) heart, as summarized in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

MAFbx/Atrogin-1 regulates protein synthesis in the transplanted (unloaded) heart. Under conditions of cardiac atrophy, such as heterotopic transplantation, MAFbx/Atrogin-1 keeps protein synthesis (PS) proportional to the rate of protein degradation (PD) by degrading calcineurin and other unidentified regulators of protein synthesis. Consequently, the heart atrophies (top panel). Heterotopic transplantation of the heart in the absence of MAFbx/Atrogin-1 leads to uncontrolled protein synthesis through calcineurin and perhaps other regulators of protein synthesis (bottom panel).

The main pathways that catalyze protein degradation in the heart are the UPS and autophagy [12, 42, 43]. MAFbx/Atrogin-1, a muscle specific ubiquitin ligase, is an enzyme of UPS-mediated protein degradation. Although it is already known that MAFbx/Atrogin-1 is required for skeletal muscle atrophy [14, 15], the role of MAFbx/Atrogin-1 in atrophy of the mechanically unloaded heart has not been investigated. Mechanical unloading of the heart by heterotopic transplantation (including denervation) enhances both protein synthesis and degradation. The relative rates of protein synthesis and degradation determine the extent of atrophy (or hypertrophy) in response to a change in workload. We propose that in the transplanted heart MAFbx/Atrogin-1 puts a brake on protein synthesis, in part by keeping calcineurin levels in check. The absence of such a break results in the (unexpected) development of hypertrophy in the presence of a decreased workload on the unloaded heart.

MAFbx/Atrogin-1−/− mice exhibit normal cardiac function and cardiac parameters at baseline [14, 20]. While, on the one hand, MAFbx/Atrogin-1 transgenic mice are resistant to pressure overload induced hypertrophy [20], on the other hand, it has recently been demonstrated that the absence of MAFbx/Atrogin-1 in the heart also attenuates pressure overload induced hypertrophy [44]. Although the reasons for this discrepancy are not clear, each study identified independent degradation targets of MAFbx/Atrogin-1: calcineurin [20] and IκB-α[44].

The role of calcineurin in cardiac hypertrophy has been extensively studied in cardiac hypertrophy [6], but until now, the role of calcineurin in atrophic remodeling of the heart was not known. We now provide evidence that MAFbx/Atrogin-1 regulates calcineurin in the transplanted (unloaded) heart and therefore is required for atrophic remodeling of the unloaded heart. We have also previously demonstrated that, like in hypertrophy [45], the NF-κB pathway is activated in the transplanted (unloaded) heart [26]. Usui et.al. have recently shown that the NF-κB pathway, which is activated with pressure overload, was attenuated with pressure overload in the absence of MAFbx/Atrogin-1 [44]. Decreased activation of the NF-κB pathway in the absence of MAFbx/Atrogin-1 during hypertrophy was attributed to decreased degradation of IκBα, an inhibitor of NF-κB [44]. Whether the same is the case with mechanical unloading has not yet been determined. Together, these studies provide support for our long-standing hypothesis that, although multiple pathways are similarly regulated in the heart with hypertrophy and atrophy, the determinant of the trophic response is largely regulated by the relative rates of protein synthesis and degradation [46].

While much attention has been given to how MAFbx/Atrogin-1 itself is regulated, relatively few degradation targets of MAFbx/Atrogin-1 have been identified [7, 47]. In skeletal muscle cells undergoing atrophy, MAFbx/Atrogin-1 is significantly increased and is localized to the nucleus [48] leading to enhanced degradation of the transcription factor MyoD [49]. As MyoD is not normally expressed in the heart, it may be the case that MAFbx/Atrogin-1 degrades a different set of proteins in the heart than in skeletal muscle. This might explain why we do not observe enhanced eIF3f protein levels in the absence of MAFbx/Atrogin-1 in the unloaded heart. In further support of this hypothesis, calcineurin A, a bone fide target of MAFbx/Atrogin-1 in the heart [19], is not degraded by MAFbx/Atrogin-1 in skeletal muscle [48]. Recent evidence suggests that MAFbx/Atrogin-1 might interact with other proteins involved in protein synthesis, such as ribosomal proteins (Rpl14, Rpl22, and Rpl7), at least in skeletal muscle [50]. Although it is not yet known whether these proteins are degraded as a consequence of ubiquitination by MAFbx/Atrogin-1, it is possible that additional factors involved in the homeostasis of protein synthesis in the heart are regulated by MAFbx/Atrogin-1.

Many changes that occur during hypertrophy also occur during atrophy [24], including alterations in calcium handling. Calcium transients are increase in cardiomyocytes from unloaded hearts, [51] and unloaded cardiomyocytes exhibit a prolonged action potential [52]. Cardiomyocytes isolated from hearts subjected to pressure overload also display a prolonged action potential, which is decreased with calcineurin inhibition [32]. Calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (CaMKII), an inhibitor of calcineurin [53], is also decreased in the unloaded heart [52]. Although not the focus of this study, it is tempting to speculate that calcium handling in the MAFbx/Atrogin-1−/− heart may also be affected by transplantation (unloading), thus contributing to increased calcineurin activity.

The characteristics of mechanical unloading in the heart, including changes in ultrastructure of the cardiomyocyte, calcium handling, and protein turnover, have recently been reviewed [1, 2, 46]. Cardiac atrophy induced by mechanical unloading, and cardiac hypertrophy induced by pressure overload demonstrate the plasticity of the heart. Many of the molecular changes that occur during atrophy and hypertrophy, and the reversibility of unloading and loading of the heart, are the same. The underlying difference between the two loading models, however, is denervation, which occurs with heterotopic transplantation of the heart. It is known that isovolumic loading of the heterotopically transplanted heart prevents atrophy [54], suggesting that atrophic remodeling is independent of innervation. This raises an interesting question: why do skeletal and heart muscle respond differently to denervation in MAFbx/Atrogin-1−/− mice? As suggested above, it may be that MAFbx/Atrogin-1 degrades distinct sets of proteins in skeletal muscle and in heart, but further investigation is warranted.

In conclusion, MAFbx/Atrogin-1 is required for atrophy induced by mechanical unloading of the heart. MAFbx/Atrogin-1 degrades calcineurin, a key regulator of cardiac hypertrophy (Figure 7). In the absence of MAFbx/Atrogin-1, calcineurin levels are unrestrained in response to transplantation (unloading) of the heart. Subsequently, rates of protein synthesis are significantly increased in unloaded MAFbx/Atrogin-1−/− cardiomyocytes, resulting in hypertrophy. The inhibition of calcineurin restores rates of protein synthesis in MAFbx/Atrogin-1−/− cardiomyocytes to rates similar to WT cardiomyocytes. Thus, MAFbx/Atrogin-1 is not only a positive regulator of protein degradation in the heart, but also a negative regulator of protein synthesis. The dynamics of the different pathways regulating atrophic remodeling of the heart offer new insights into the clinical phenomenon of “reverse remodeling” which still awaits its complete elucidation.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

MAFbx/Atrogin-1 is required for atrophic remodeling of the heart

MAFbx/Atrogin-1 regulates protein synthesis in mechanically unloaded mouse hearts

Mechanical unloading of failing human hearts increases MAFbx/Atrogin-1 protein levels

MAFbx/Atrogin-1 controls cardiac mass by regulating protein synthesis and degradation

Acknowledgments

We thank Roxy A. Tate for help with the manuscript preparation. These studies were supported in part, by a grant from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (5R01HL061483) of the US Public Health Service. K.K.B. received a predoctoral fellowship from the American Heart Association, National Center (11PRE5200006). M.R.R. was supported by an award from the Center for Clinical and Translational Science TL1 program funded by the NIH.

Funding Source

These studies were supported in part, by a grant from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (5R01HL061483-10) of the US Public Health Service. K.K.B. received a predoctoral fellowship from the American Heart Association, National Center (11PRE5200006).

Non-standard Abbreviations and Acronyms

- AMCM

adult mouse cardiomyoctyes

- Atg

autophagy-related gene

- CnA

calcineurin A

- CsA

cyclosporine A

- eIF3f

eukaryotic initiation factor 3f

Footnotes

None of the authors has any financial conflicts of interest to disclose.

Disclosures

There are no financial conflicts of interest to report on behalf of the authors.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Birks EJ. Molecular changes after left ventricular assist device support for heart failure. Circulation research. 2013;113:777–91. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.113.301413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hellawell JL, Margulies KB. Myocardial reverse remodeling. Cardiovascular therapeutics. 2012;30:172–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-5922.2010.00247.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Razeghi P, Myers TJ, Frazier OH, Taegtmeyer H. Reverse remodeling of the failing human heart with mechanical unloading. Emerging concepts and unanswered questions. Cardiology. 2002;98:167–74. doi: 10.1159/000067313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Razeghi P, Sharma S, Ying J, Li YP, Stepkowski S, Reid MB, et al. Atrophic remodeling of the heart in vivo simultaneously activates pathways of protein synthesis and degradation. Circulation. 2003;108:2536–41. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000096481.45105.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Razeghi P, Buksinska-Lisik M, Palanichamy N, Stepkowski S, Frazier OH, Taegtmeyer H. Transcriptional regulators of ribosomal biogenesis are increased in the unloaded heart. FASEB J. 2006;20:1090–6. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-5718com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Heineke J, Molkentin JD. Regulation of cardiac hypertrophy by intracellular signalling pathways. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2006;7:589–600. doi: 10.1038/nrm1983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Portbury AL, Ronnebaum SM, Zungu M, Patterson C, Willis MS. Back to your heart: ubiquitin proteasome system-regulated signal transduction. Journal of molecular and cellular cardiology. 2012;52:526–37. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2011.10.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nemchenko A, Chiong M, Turer A, Lavandero S, Hill JA. Autophagy as a therapeutic target in cardiovascular disease. Journal of molecular and cellular cardiology. 2011;51:584–93. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2011.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morgan HE, Rannels DE, Kao RL. Factors controlling protein turnover in heart muscle. Circulation research. 1974;35 (Suppl 3):22–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lecker SH, Solomon V, Mitch WE, Goldberg AL. Muscle protein breakdown and the critical role of the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway in normal and disease states. J Nutr. 1999;129:227S–37S. doi: 10.1093/jn/129.1.227S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schiaffino S, Dyar KA, Ciciliot S, Blaauw B, Sandri M. Mechanisms regulating skeletal muscle growth and atrophy. The FEBS journal. 2013;280:4294–314. doi: 10.1111/febs.12253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang XJ, Yu J, Wong SH, Cheng AS, Chan FK, Ng SS, et al. A novel crosstalk between two major protein degradation systems: Regulation of proteasomal activity by autophagy. Autophagy. 2013:9. doi: 10.4161/auto.25573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mearini G, Schlossarek S, Willis MS, Carrier L. The ubiquitin-proteasome system in cardiac dysfunction. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 2008;1782:749–63. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2008.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bodine SC, Latres E, Baumhueter S, Lai VK, Nunez L, Clarke BA, et al. Identification of ubiquitin ligases required for skeletal muscle atrophy. Science. 2001;294:1704–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1065874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gomes MD, Lecker SH, Jagoe RT, Navon A, Goldberg AL. Atrogin-1, a muscle-specific F-box protein highly expressed during muscle atrophy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:14440–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.251541198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sandri M, Sandri C, Gilbert A, Skurk C, Calabria E, Picard A, et al. Foxo transcription factors induce the atrophy-related ubiquitin ligase atrogin-1 and cause skeletal muscle atrophy. Cell. 2004;117:399–412. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00400-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cao DJ, Jiang N, Blagg A, Johnstone JL, Gondalia R, Oh M, et al. Mechanical unloading activates FoxO3 to trigger Bnip3-dependent cardiomyocyte atrophy. Journal of the American Heart Association. 2013;2:e000016. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.113.000016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Skurk C, Izumiya Y, Maatz H, Razeghi P, Shiojima I, Sandri M, et al. The FOXO3a transcription factor regulates cardiac myocyte size downstream of AKT signaling. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:20814–23. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M500528200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li HH, Kedar V, Zhang C, McDonough H, Arya R, Wang DZ, et al. Atrogin-1/muscle atrophy F-box inhibits calcineurin-dependent cardiac hypertrophy by participating in an SCF ubiquitin ligase complex. J Clin Invest. 2004;114:1058–71. doi: 10.1172/JCI22220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li HH, Willis MS, Lockyer P, Miller N, McDonough H, Glass DJ, et al. Atrogin-1 inhibits Akt-dependent cardiac hypertrophy in mice via ubiquitin-dependent coactivation of Forkhead proteins. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:3211–23. doi: 10.1172/JCI31757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Arya R, Kedar V, Hwang JR, McDonough H, Li HH, Taylor J, et al. Muscle ring finger protein-1 inhibits PKC{epsilon} activation and prevents cardiomyocyte hypertrophy. J Cell Biol. 2004;167:1147–59. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200402033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Willis MS, Ike C, Li L, Wang DZ, Glass DJ, Patterson C. Muscle ring finger 1, but not muscle ring finger 2, regulates cardiac hypertrophy in vivo. Circulation research. 2007;100:456–9. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000259559.48597.32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Willis MS, Rojas M, Li L, Selzman CH, Tang RH, Stansfield WE, et al. Muscle ring finger 1 mediates cardiac atrophy in vivo. American journal of physiology Heart and circulatory physiology. 2009;296:H997–h1006. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00660.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Depre C, Shipley GL, Chen W, Han Q, Doenst T, Moore ML, et al. Unloaded heart in vivo replicates fetal gene expression of cardiac hypertrophy. Nat Med. 1998;4:1269–75. doi: 10.1038/3253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Corry RJ, Winn HJ, Russell PS. Heart transplantation in congenic strains of mice. Transplant Proc. 1973;5:733–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Razeghi P, Wang ME, Youker KA, Golfman L, Stepkowski S, Taegtmeyer H. Lack of NF-kappaB1 (p105/p50) attenuates unloading-induced downregulation of PPARalpha and PPARalpha-regulated gene expression in rodent heart. Cardiovasc Res. 2007;74:133–9. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2006.12.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhao J, Brault JJ, Schild A, Cao P, Sandri M, Schiaffino S, et al. FoxO3 coordinately activates protein degradation by the autophagic/lysosomal and proteasomal pathways in atrophying muscle cells. Cell metabolism. 2007;6:472–83. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2007.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gustafsson AB, Gottlieb RA. Autophagy in ischemic heart disease. Circulation research. 2009;104:150–8. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.187427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Klionsky DJ, Abdalla FC, Abeliovich H, Abraham RT, Acevedo-Arozena A, Adeli K, et al. Guidelines for the use and interpretation of assays for monitoring autophagy. Autophagy. 2012;8:445–544. doi: 10.4161/auto.19496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sugden PH, Fuller SJ. Regulation of protein turnover in skeletal and cardiac muscle. The Biochemical journal. 1991;273(Pt 1):21–37. doi: 10.1042/bj2730021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dorn GW, 2nd, Force T. Protein kinase cascades in the regulation of cardiac hypertrophy. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:527–37. doi: 10.1172/JCI24178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Doenst T, Goodwin GW, Cedars AM, Wang M, Stepkowski S, Taegtmeyer H. Load-induced changes in vivo alter substrate fluxes and insulin responsiveness of rat heart in vitro. Metabolism. 2001;50:1083–90. doi: 10.1053/meta.2001.25605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lagirand-Cantaloube J, Offner N, Csibi A, Leibovitch MP, Batonnet-Pichon S, Tintignac LA, et al. The initiation factor eIF3-f is a major target for atrogin1/MAFbx function in skeletal muscle atrophy. The EMBO journal. 2008;27:1266–76. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2008.52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Molkentin JD. Calcineurin and beyond: cardiac hypertrophic signaling. Circulation research. 2000;87:731–8. doi: 10.1161/01.res.87.9.731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wilkins BJ, Dai YS, Bueno OF, Parsons SA, Xu J, Plank DM, et al. Calcineurin/NFAT coupling participates in pathological, but not physiological, cardiac hypertrophy. Circulation research. 2004;94:110–8. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000109415.17511.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Razeghi P, Baskin KK, Sharma S, Young ME, Stepkowski S, Essop MF, et al. Atrophy, hypertrophy, and hypoxemia induce transcriptional regulators of the ubiquitin proteasome system in the rat heart. Biochemical and biophysical research communications. 2006;342:361–4. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.01.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Eschricht S, Jarr KU, Kuhn C, Katus H, Frey N, Chorianopoulos E. Calcineurin A stabilizes hypoxia-inducible factor-1 alpha via a heat shock protein (HSP) 90 dependent mechanism in myocardial hypertrophy. European Heart Journal. 2013:34. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liu YV, Hubbi ME, Pan F, McDonald KR, Mansharamani M, Cole RN, et al. Calcineurin promotes hypoxia-inducible factor 1alpha expression by dephosphorylating RACK1 and blocking RACK1 dimerization. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:37064–73. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M705015200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Singh S, Manda SM, Sikder D, Birrer MJ, Rothermel BA, Garry DJ, et al. Calcineurin activates cytoglobin transcription in hypoxic myocytes. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:10409–21. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M809572200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stow LR, Jacobs ME, Wingo CS, Cain BD. Endothelin-1 gene regulation. FASEB J. 2011;25:16–28. doi: 10.1096/fj.10-161612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sharma S, Ying J, Razeghi P, Stepkowski S, Taegtmeyer H. Atrophic remodeling of the transplanted rat heart. Cardiology. 2006;105:128–36. doi: 10.1159/000090550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Willis MS, Townley-Tilson WH, Kang EY, Homeister JW, Patterson C. Sent to destroy: the ubiquitin proteasome system regulates cell signaling and protein quality control in cardiovascular development and disease. Circulation research. 2010;106:463–78. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.208801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cao DJ, Gillette TG, Hill JA. Cardiomyocyte autophagy: remodeling, repairing, and reconstructing the heart. Current hypertension reports. 2009;11:406–11. doi: 10.1007/s11906-009-0070-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Usui S, Maejima Y, Pain J, Hong C, Cho J, Park JY, et al. Endogenous muscle atrophy F-box mediates pressure overload-induced cardiac hypertrophy through regulation of nuclear factor-kappaB. Circulation research. 2011;109:161–71. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.238717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gordon JW, Shaw JA, Kirshenbaum LA. Multiple facets of NF-kappaB in the heart: to be or not to NF-kappaB. Circulation research. 2011;108:1122–32. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.226928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Baskin KK, Taegtmeyer H. Taking pressure off the heart: the ins and outs of atrophic remodelling. Cardiovasc Res. 2011;90:243–50. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvr060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schisler JC, Willis MS, Patterson C. You spin me round: MaFBx/Atrogin-1 feeds forward on FOXO transcription factors (like a record) Cell cycle (Georgetown, Tex) 2008;7:440–3. doi: 10.4161/cc.7.4.5451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lagirand-Cantaloube J, Cornille K, Csibi A, Batonnet-Pichon S, Leibovitch MP, Leibovitch SA. Inhibition of atrogin-1/MAFbx mediated MyoD proteolysis prevents skeletal muscle atrophy in vivo. PloS one. 2009;4:e4973. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tintignac LA, Lagirand J, Batonnet S, Sirri V, Leibovitch MP, Leibovitch SA. Degradation of MyoD mediated by the SCF (MAFbx) ubiquitin ligase. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:2847–56. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M411346200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lokireddy S, Wijesoma IW, Sze SK, McFarlane C, Kambadur R, Sharma M. Identification of atrogin-1-targeted proteins during the myostatin-induced skeletal muscle wasting. American journal of physiology Cell physiology. 2012;303:C512–29. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00402.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ritter M, Su Z, Xu S, Shelby J, Barry WH. Cardiac unloading alters contractility and calcium homeostasis in ventricular myocytes. Journal of molecular and cellular cardiology. 2000;32:577–84. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.2000.1101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Schwoerer AP, Melnychenko I, Goltz D, Hedinger N, Broichhausen I, El-Armouche A, et al. Unloaded rat hearts in vivo express a hypertrophic phenotype of cardiac repolarization. Journal of molecular and cellular cardiology. 2008;45:633–41. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2008.02.271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.MacDonnell SM, Weisser-Thomas J, Kubo H, Hanscome M, Liu Q, Jaleel N, et al. CaMKII negatively regulates calcineurin-NFAT signaling in cardiac myocytes. Circulation research. 2009;105:316–25. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.194035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Klein I, Hong C, Schreiber SS. Isovolumic loading prevents atrophy of the heterotopically transplanted rat heart. Circulation research. 1991;69:1421–5. doi: 10.1161/01.res.69.5.1421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.