Abstract

Purpose

Primary malignant bone tumours and soft tissue sarcomas of the chest wall are exceedingly rare entities. The aim of this study was a retrospective two-institutional analysis of surgical therapy with respect to the kind and amount of the resection performed, the type of reconstruction and the oncological outcome.

Methods

Between September 1999 and August 2010 31 patients (seven women and 24 men) were treated due to a primary malignant bone tumour or soft tissue sarcoma of the chest wall in two centres. Eight low-grade sarcomas were noted as well as 23 highly malignant sarcomas. The tumours originated from the sternum in six cases, from the ribs in 12 cases, from the soft tissues of the thoracic wall in 11 cases and from a vertebral body and the clavicle in one case each.

Results

In 26 cases wide resection margins were achieved, while four were intralesional and one was marginal. In all 31 cases the defect of the chest wall was reconstructed using mesh grafts. At a mean follow-up of 51 months 20 patients were without evidence of disease, three were alive with disease, seven patients had died and one patient was lost to follow-up. One recurrence was detected after wide resection of a malignant triton tumour.

Conclusions

Primary malignant bone tumour or soft tissue sarcoma of the chest wall should be treated according to the same surgical oncological principles as established for the extremities. Reconstruction with mesh grafts and musculocutaneous flaps is associated with a low morbidity.

Keywords: Sarcoma, Thoracic wall, Mesh graft, Surgical margin

Introduction

Wide resection with tumour-free margins is necessary in cases of malignant soft tissue and bone tumours to minimise local recurrence rates and to contribute to long-term survival. Further, small tumour size increases the possibility of curative treatment [1]. Sarcomas of the chest wall (soft tissue or bone) with involvement of ribs or sternum, or the overlying soft tissues, are rare entities, with chondrosarcomas as the most frequent ones [1–12]. Compared to osteosarcomas or Ewing’s sarcomas, an effective chemotherapy for chondrosarcomas does not exist. Furthermore, this entity is also relatively radio insensitive [8–10]. Therefore, the main treatment modality of choice is early wide resection.

Plain radiographs of the chest and computed tomography (CT) with contrast medium are the gold standard for diagnosis and operative planning for bony thoracic expansions. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is standard for the diagnosis of soft tissue tumours and to determine the extension of the neoplasm. In most cases, especially soft tissue tumours, an open biopsy or CT-guided biopsy is required for planning further surgical treatment as well as the pre- and post-operative treatment [11].

In most cases of malignant thoracic tumours, full-thickness chest wall resection (CWR) is needed with skeletal reconstruction and soft tissue coverage depending on the size of the defect. Depending on the entity, (neo-) adjuvant chemotherapy has to be given additionally.

Overall, information about treatment and oncological outcome of sarcomas of the chest wall is limited [2, 8–12]. Recently, Widhe and Bauer [5] showed that patients with delayed diagnosis of chondrosarcomas of the chest had significantly higher risk of tumour-related deaths. On the other hand, King et al. [7] showed a significantly better prognosis for chondrosarcomas of the chest wall compared to malignant fibrous histiocytomas, and Burt et al. [6, 9] reported a significantly longer survival rate for chondrosarcomas compared to osteosarcomas. Nevertheless, synchronous or metachronous diagnosis of metastases in lung, liver and/or bone is further associated with a significantly worse prognosis [6, 8–10, 12].

The aim of this study was a retrospective two-institutional analysis of the surgical therapy of primary malignant bone tumours and soft tissue sarcomas of the chest wall with respect to the kind and amount of the resection performed, the type of reconstruction and the oncological outcome.

Patients and methods

This retrospective study was performed using the database of patients treated surgically in a multidisciplinary approach for malignant bone tumours and malignant soft tissue sarcomas of the chest wall between September 1999 and August 2010. Overall, 31 patients were identified. There were seven female and 24 male patients with a mean age of 45 years (range 14–78, Table 1).

Table 1.

Patients’ demographics presenting sex, age, entity, location, primary vs secondary referral, metastases at the time of diagnosis, pre- and post-operative adjuvant therapy, surgical margin, mesh graft, time of follow-up, status of disease and local recurrence at latest follow-up

| No. | Sex & age | Diagnosis & grading | Localisation | Previous surgery | Mets | CTx/RTx | Margin | Meshes | Follow-up (months) | Status | Relapse |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | M, 49 | Chondrosarcoma G1 | Sternum | N | N | N | Wide | Prolene | 3 | NED | 0 |

| 2 | M, 78 | Chondrosarcoma G1 | Costa VI | N | N | N | Wide | Vicryl | 93 | NED | 0 |

| 3 | F, 40 | Chondrosarcoma G1 | Thoracic spine | N | N | N | Wide | Vicryl | 94 | NED | 0 |

| 4 | M, 23 | Chondrosarcoma G1 | Sternum | N | N | N | Wide | Prolene | 136 | NED | 0 |

| 5 | M, 72 | Chondrosarcoma G3 | Costa VII | N | N | Post-op. | Wide | Prolene | 7 | DOD | 0 |

| 6 | M, 28 | Ewing’s sarcoma | Costa X | N | N | Pre- & post-op. | Wide | Prolene | 9 | NED | 0 |

| 7 | M, 49 | Fibromyxosarcoma G1 | Thoracic wall | Y | N | N | Wide | Prolene | 59 | NED | 0 |

| 8 | M, 62 | Leiomyosarcoma G3 | Costa X | N | Y | Post-op. | Wide | Prolene | 25 | DOD | 0 |

| 9 | M, 69 | MFH G3 | Costa X+XI | Y | Y | Post-op. | Wide | Vicryl | – | LOST | 0 |

| 10 | M, 64 | Myxofibrosarcoma G3 | Thoracic wall | Y | N | Post-op. | Wide | Prolene | 7 | NED | 0 |

| 11 | M, 24 | Osteosarcoma G3 | Sternum | N | N | Pre- & post-op. | Wide | Prolene | 85 | NED | 0 |

| 12 | F, 70 | Synovial sarcoma G3 | Costa XI | N | N | Post-op. | Wide | Prolene | 83 | NED | 0 |

| 13 | F, 20 | Ewing’s sarcoma | Costa XI | N | N | Pre- & post-op. | Wide | Prolene | 8 | NED | 0 |

| 14 | M, 46 | MPNST G3 | Thoracic wall | N | Y | Post-op. | Intralesional | Gore-Tex | 4 | DOD | 0 |

| 15 | M, 25 | Ewing’s sarcoma | Costa IX | N | N | Pre- & post-op. | Wide | Gore-Tex | 141 | NED | 0 |

| 16 | F, 23 | Malignant triton tumour | Thoracic wall | Y | N | N | Wide | Vicryl | 20 | DOD | 1 |

| 17 | M, 43 | Chondrosarcoma G1 | Manubrium | N | N | N | Wide | Vicryl | 125 | DOD | 0 |

| 18 | M, 58 | Malignant fibrous tumour G1 | Thoracic wall | N | N | N | Wide | Gore-Tex | 99 | NED | 0 |

| 19 | M, 26 | Rhabdomyosarcoma G3 | Thoracic wall | N | Y | Pre- & post-op. | Intralesional | Gore-Tex | 100 | NED | 0 |

| 20 | F, 60 | Pleomorphic sarcoma G3 | Thoracic wall | N | N | N | Wide | Gore-Tex | 99 | NED | 0 |

| 21 | M, 27 | Osteosarcoma G3 | Costa VIII | Y | N | Pre- & post-op. | Wide | Parietene | 57 | NED | 0 |

| 22 | M, 14 | Ewing’s sarcoma | Costa XI | N | Y | Pre- & post-op. | Wide | Surgisis | 38 | NED | 0 |

| 23 | M, 29 | Mesenchymal chondrosarcoma | Costa III | N | N | N | Wide | Gore-Tex | 43 | NED | 0 |

| 24 | M, 62 | Sarcoma NOS G3 | Thoracic wall | N | N | Preop. | Intralesional | Parietex | 29 | DOD | 0 |

| 25 | M, 56 | Chondrosarcoma G2 | Sternum | N | Y | N | Wide | Gore-Tex | 35 | DOOC | 0 |

| 26 | F, 56 | MPNST G2 | Thoracic wall | N | N | N | Wide | Gore-Tex | 32 | AWD | 0 |

| 27 | M, 21 | Ewing’s sarcoma | Thoracic wall | N | N | Pre- & post-op. | Intralesional | Gore-Tex | 20 | NED | 0 |

| 28 | M, 36 | Osteosarcoma G3 | Clavicle | Y | Y | Pre- & post-op. | Wide | Vicryl | 18 | AWD | 0 |

| 29 | M, 43 | Osteosarcoma G3 | Costa VIII | N | N | Pre- & post-op. | Wide | Gore-Tex | 11 | NED | 0 |

| 30 | F, 53 | Sarcoma NOS G1 | Thoracic wall | N | N | N | Marginal | Gore-Tex | 6 | NED | 0 |

| 31 | M, 62 | Chondrosarcoma G2 | Manubrium | N | N | N | Wide | Gore-Tex | 81 | AWD | 0 |

Mets metastases, CTx chemotherapy, RTx radiotherapy, NED no evidence of disease, DOD died of disease, MFH malignant fibrous histiocytomaLOST lost to follow-up, MPNST malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumour, NOS not otherwise specified, DOOC died of other causes, AWD alive with disease

Of the patients, 13 were treated at the first centre (Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Medical University of Graz, Austria), while 18 were included from the second centre (Department of Orthopaedic Oncology, Sarkomzentrum Berlin-Brandenburg, Germany).

Definite histological analysis revealed eight low-grade sarcomas (grade 1, G1; 5 bone, 3 soft tissue) and 23 highly malignant sarcomas (grades 2 and 3, G2/3) including five Ewing’s sarcomas and four osteosarcomas. Seven patients with high-grade sarcomas had metastases at the time of diagnosis and five patients were admitted after previous inadequate excision.

The tumours originated from the sternum in six cases, from the ribs in 12 cases, from the soft tissues of the thoracic wall in 11 cases and from a vertebral body and the clavicle in one case each.

In ten cases chemotherapy was given pre- and post-operatively, in two only post-operatively and in one case only preoperatively. Two patients received local radiation therapy preoperatively and seven post-operatively. Patients’ demographics, pathology records, data on surgical procedure, (neo-) adjuvant treatment and follow-up data are shown in Table 1.

Statistical analysis

The main endpoint of this study was the overall survival, and univariate analysis was performed using the Kaplan-Meier method and the log-rank test, respectively. One patient who was lost to follow-up post-operatively was excluded from statistical analysis; therefore, 30 cases were included. Factors analysed for prognostic significance included the following: type of referral (initial vs secondary), age (dichotomised into patients <50 years vs those >50 years), sex, entity (low-grade bone vs high-grade bone vs soft tissue sarcomas), metastases at the time of diagnosis, margins (negative vs positive) and the use of adjuvant therapies including chemotherapy, radiation therapy or both. A p value of <0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. For statistical analysis the PASW Statistics 16.0 program (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used.

Informed consent

This study conforms to the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the local Ethics Committee. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients.

Results

Overall, in 26 of 31 patients wide resection margins were achieved. In one patient a marginal and in four patients an intralesional resection was noted. Several surgeries were performed in a multidisciplinary setting of orthopaedic surgeons, cardiothoracic surgeons or plastic surgeons.

In 27 patients a mean of three ribs had to be resected (range one to five); in two of those cases a hemivertebrectomy and a dorsal spinal fusion had to be performed additionally (Figs. 1a–g and 2a, b). In six cases the whole or at least parts of the sternum had to be resected. There were no peri- or post-operative deaths observed. In all 31 cases the defect of the chest wall was reconstructed using artificial mesh grafts; six resorbable Vicryl meshes (Ethicon Inc., Somerville, NJ, USA) and 25 non-resorbable ones were used [ten Prolene meshes (Ethicon), 12 Gore-Tex soft tissue patches (W. L. Gore & Associates Inc., Flagstaff, AZ, USA), one Parietex Dual mesh (Covidien, Norwalk, CT, USA), one Parietene mesh (Covidien) and one Surgisis patch (Cook Biotech, Bloomington, IN, USA)]. The artificial mesh grafts were chosen according to the surgeon’s preference.

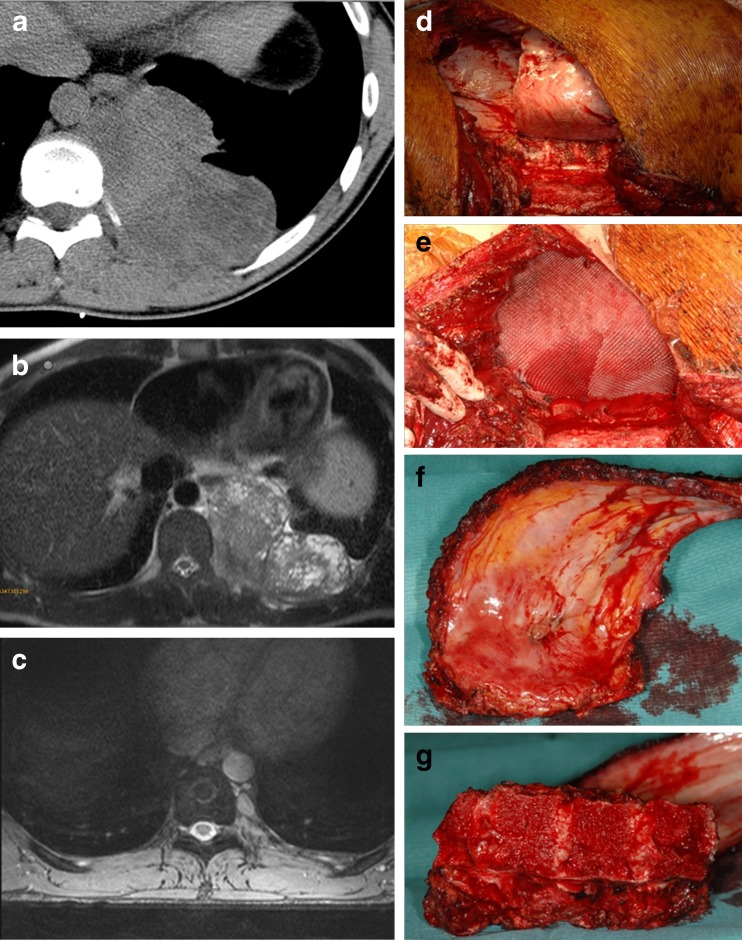

Fig. 1.

a, b CT and MRI of the posterior thoracic wall showing an intrathoracic Ewing’s sarcoma in a 20-year-old male patient. c MRI 8 months following neoadjuvant chemotherapy. d, e Photographs of the intraoperative situs following wide resection of a Ewing’s sarcoma of the posterior thoracic wall and reconstruction using an artificial mesh graft. f, g Photographs of the resected ribs and the thoracic spine following hemicorporectomy

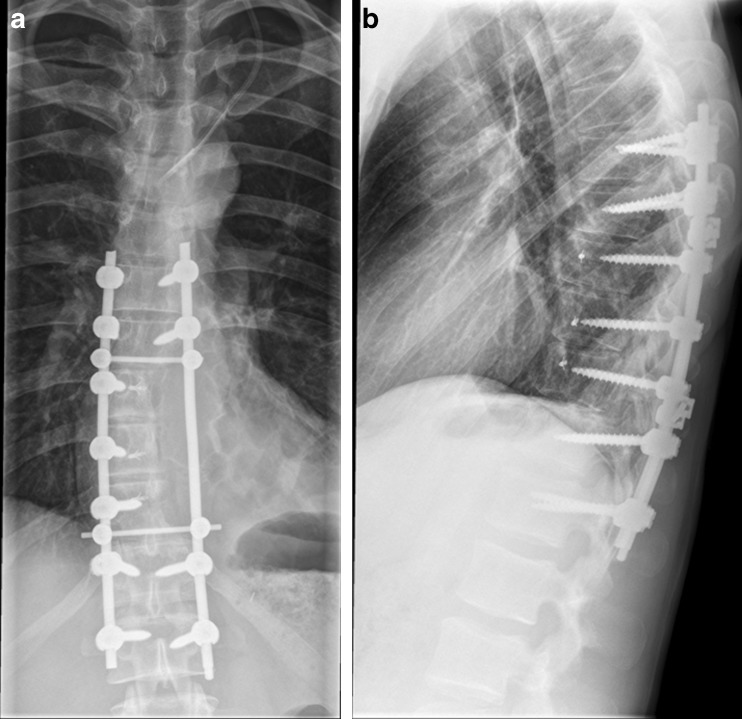

Fig. 2.

a, b Anteroposterior and lateral plain radiographs of the thoracic spine 3 months following wide resection of a Ewing’s sarcoma with hemicorporectomy and spinal fusion

At a mean follow-up of 52 months (range three to 141) 20 patients were observed without evidence of disease, three were alive with disease, six died of their disease, one died of another cause and one was lost to follow-up. One recurrence was detected after wide resection of a malignant triton tumour.

The calculated overall survival for soft tissue and bone tumours revealed 74.2 % survival at both five and ten years of follow-up (Fig. 3a). The calculated overall survival stratified by grading showed 100 % survival for grade 1 and 64.5 % for grade 2 and 3 tumours at five and ten years, respectively (Fig. 3b). Furthermore, survival for low-grade bone tumours was 100 %, whereas the survival for high-grade bone malignancies was 79.1 % at five and ten years. The overall survival was 61.1 % at five years for soft tissue sarcomas (Fig. 3c). The results of factors which have been analysed for prognostic significance are shown in Table 2.

Fig. 3.

Kaplan-Meier curves showing patients’ overall survival (a) as well as patients’ survival stratified by grading (b) and entity (c)

Table 2.

Prognostic factors for overall recurrence-free 5-year survival

| Variable | Overall 5-year survival (n = 30) | p value |

|---|---|---|

| Total population | 74.2 % | |

| Type of referral (initial vs secondary) | Initial (n = 25) 74.9 % | 0.821 |

| Secondary (n = 5) 66.7 % | ||

| Age (<50 vs >50 years) | <50 (n = 18) 86.3 % | 0.220 |

| >50 (n = 12) 58.3 % | ||

| Sex | Male (n = 23) 72.5 % | 0.745 |

| Female (n = 7) 80.0 % | ||

| Entity | Low-grade bone (n = 5) 100 % | 0.282 |

| High-grade bone (n = 13) 79.1 % | ||

| STS (n = 12) 61.1 % | ||

| Metastases at the time of diagnosis | No metastases (n = 24) 83.7 % | 0.056 |

| Metastases (n = 6) 41.7 % | ||

| Margins (negative vs positive) | Negative (n = 26) 79.4 | 0.086 |

| Positive (n = 4) 37.5 % | ||

| Adjuvant therapy (CTx and/or RTx) | Yes (n = 16) 65.3 % | 0.457 |

| No (n = 14) 82.5 % |

One patient who was lost to follow-up immediately following surgery was excluded from statistical analysis

CTx chemotherapy, RTx radiotherapy, STS soft tissue sarcoma

Discussion

The aim of this study was a retrospective two-institutional analysis of the surgical therapy of primary malignant bone tumours and soft tissue sarcomas of the chest wall with respect to the kind and amount of resection performed, the type of reconstruction and the oncological outcome.

The majority of tumours of the thoracic wall present as enlarging, painful masses at the anterior chest wall, while less commonly posterior tumours present from the paravertebral region [8, 9]. On the other hand, patients sometimes present with painless lumps, which might be due to the fact that the ribs and the sternum are non-weight-bearing bones [5]. Nevertheless, reaction or destruction of the periosteum might cause pain. McAfee et al. [1] and Berquist et al. [13] recommended the radical excision of all structures attached to the tumour such as lung, pericardium or thymus. In the study of King et al. [7], the involvement of the viscera was additionally associated with worse oncological outcome with reduced survival.

Chest wall defects which are protected by the scapula and posterior muscle groups do not require reconstruction, while lateral chest wall and sternal defects have to be stabilised to protect the underlying viscera, to improve the respiratory mechanics and at least to improve the cosmetic result [1, 3, 8]. Nevertheless, wide margins are inevitable, and therefore resection has to be done without any compromise and reconstruction should be performed by a separate team of plastic surgeons if necessary. Mesh grafts and musculocutaneous flaps are the most common ways of reconstruction and wound closure with low morbidity rates. Coonar et al. [14] reported the use of a novel titanium rib bridge system, which seems to be a very expensive method.

Chondrosarcomas are the most common entity in cases of malignant tumours of the thoracic wall [1, 2, 4–6, 8–12, 15–17]. These are mainly low-grade, and therefore they have a comparatively good prognosis like in the current series [2, 9]. Nevertheless, the tumour grade is a well-accepted prognostic factor in sarcoma surgery, and it has been found that sarcomas of the thoracic wall have the same prognosis as extremity sarcomas [2, 3, 9]. Furthermore, the recurrence rate is highly dependent on the surgical margin [1, 4–8, 11, 12]. Widhe and Bauer [5] reported inadequate diagnosis and treatment of bone sarcomas of the thoracic wall in up to 74 % outside a sarcoma centre. Like in other series, patients with secondary referral had a worse prognosis compared to those with primary referral [3]. Nevertheless, in the current series the difference in survival of these patients was not statistically significant (p = 0.086), which might be due to the fact that a relatively small number of patients was included in the study.

van Geel et al. [2] described CWR as a safe surgical procedure with low morbidity and mortality. In this series compared to others, patients with radiation-induced soft tissue sarcomas had a significantly worse prognosis [2–4]. Nevertheless, delayed diagnosis as well as metastases at the time of diagnosis worsens the oncological outcome significantly as observed in the our series [5].

The reported overall survival at ten years for sarcomas of the chest wall ranges from 33 to 96 % [1–10, 12, 17, 18]. In the our series the overall survival was 74.2 % at ten years for soft tissue and bone sarcomas, which is within the reported limits in the literature [1–10, 17, 18].

One limitation of the study is the heterogeneous patient group with soft tissue and bone sarcomas included. Further, there was a small number of patients enrolled in the our study. Therefore, some prognostic factors did not reach statistically significant differences such as surgical margins or metastases at the time of diagnosis, while in several other studies they did [3].

Conclusion

Primary malignant bone and soft tissue tumours of the chest wall have to be treated according to the same surgical oncological principles as established for extremity sarcomas. Furthermore, an interdisciplinary approach is sometimes inevitable, and reconstruction with artificial meshes and musculocutaneous flaps is associated with a low morbidity.

Acknowledgments

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

Andreas Leithner, Email: andreas.leithner@medunigraz.at.

Patrick Sadoghi, Phone: +43-316-38580971, FAX: +43-316-38514806, Email: patrick.sadoghi@medunigraz.at.

References

- 1.McAfee MK, Pairolero PC, Bergstralh EJ, Piehler JM, Unni KK, McLeod RA, Bernatz PE, Payne WS. Chondrosarcoma of the chest wall: factors affecting survival. Ann Thorac Surg. 1985;40(6):535–541. doi: 10.1016/S0003-4975(10)60344-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van Geel AN, Wouters MW, Lans TE, Schmitz PI, Verhoef C. Chest wall resection for adult soft tissue sarcomas and chondrosarcomas: analysis of prognostic factors. World J Surg. 2011;35(1):63–69. doi: 10.1007/s00268-010-0804-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Walsh GL, Davis BM, Swisher SG, Vaporciyan AA, Smythe WR, Willis-Merriman K, Roth JA, Putnam JB., Jr A single-institutional, multidisciplinary approach to primary sarcomas involving the chest wall requiring full-thickness resections. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2001;121(1):48–60. doi: 10.1067/mtc.2001.111381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Widhe B, Bauer HC, Scandinavian Sarcoma Group Surgical treatment is decisive for outcome in chondrosarcoma of the chest wall: a population-based Scandinavian Sarcoma Group study of 106 patients. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2009;137(3):610–614. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2008.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Widhe B, Bauer HC. Diagnostic difficulties and delays with chest wall chondrosarcoma: a Swedish population based Scandinavian Sarcoma Group study of 106 patients. Acta Oncol. 2011;50(3):435–440. doi: 10.3109/0284186X.2010.486797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burt M, Fulton M, Wessner-Dunlap S, Karpeh M, Huvos AG, Bains MS, Martini N, McCormack PM, Rusch VW, Ginsberg RJ. Primary bony and cartilaginous sarcomas of chest wall: results of therapy. Ann Thorac Surg. 1992;54(2):226–232. doi: 10.1016/0003-4975(92)91374-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.King RM, Pairolero PC, Trastek VF, Piehler JM, Payne WS, Bernatz PE. Primary chest wall tumors: factors affecting survival. Ann Thorac Surg. 1986;41(6):597–601. doi: 10.1016/S0003-4975(10)63067-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rascoe PA, Reznik SI, Smythe WR. Chondrosarcoma of the thorax. Sarcoma. 2011;2011:342879. doi: 10.1155/2011/342879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Burt M. Primary malignant tumors of the chest wall. The Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center experience. Chest Surg Clin N Am. 1994;4(1):137–154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Graeber GM, Snyder RJ, Fleming AW, Head HD, Lough FC, Parker JS, Zajtchuk R, Brott WH. Initial and long-term results in the management of primary chest wall neoplasms. Ann Thorac Surg. 1982;34(6):664–673. doi: 10.1016/S0003-4975(10)60906-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smith SE, Keshavjee S. Primary chest wall tumors. Thorac Surg Clin. 2010;20(4):495–507. doi: 10.1016/j.thorsurg.2010.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kucharczuk JC. Chest wall sarcomas and induction therapy. Thorac Surg Clin. 2012;22(1):77–81. doi: 10.1016/j.thorsurg.2011.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Berquist TH, Sheedy PF, 2nd, Stanson AW, Brown LR, Payne WS. Systemic artery-to-pulmonary vein fistula in osteogenic sarcoma of the chest wall. Cardiovasc Radiol. 1978;1(4):261–263. doi: 10.1007/BF02552053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Coonar AS, Qureshi N, Smith I, Wells FC, Reisberg E, Wihlm JM. A novel titanium rib bridge system for chest wall reconstruction. Ann Thorac Surg. 2009;87(5):e46–e48. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2009.01.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Briccoli A, De Paolis M, Campanacci L, Mercuri M, Bertoni F, Lari S, Balladelli A, Rocca M. Chondrosarcoma of the chest wall: a clinical analysis. Surg Today. 2002;32(4):291–296. doi: 10.1007/s005950200040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fong YC, Pairolero PC, Sim FH, Cha SS, Blanchard CL, Scully SP. Chondrosarcoma of the chest wall: a retrospective clinical analysis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2004;427:184–189. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000136834.02449.e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sabanathan S, Shah R, Mearns AJ. Surgical treatment of primary malignant chest wall tumours. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 1997;11(6):1011–1016. doi: 10.1016/S1010-7940(97)00090-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yang JC, Chang AE, Baker AR, Sindelar WF, Danforth DN, Topalian SL, DeLaney T, Glatstein E, Steinberg SM, Merino MJ, et al. Randomized prospective study of the benefit of adjuvant radiation therapy in the treatment of soft tissue sarcomas of the extremity. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16(1):197–203. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.1.197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]