Abstract

Purpose

Reverse shoulder prostheses have been gaining popularity in recent years. A short metaphyseal stem design will allow bone stock preservation and minimize stem related complications. We examined the clinical and radiographic short-term outcome of a short metaphyseal stem reverse shoulder arthroplasty.

Methods

Thirty-one patients, with a mean follow-up of 36 months (24–52), were evaluated clinically with the Constant-Murley score, patient satisfaction and pain relief scores. The fixation of the glenoid and humeral components, subsidence and notching were evaluated on radiographs. The indications were cuff tear arthropathy (22), fracture sequelae (five) and rheumatoid arthritis (four).

Results

The average Constant score improved from 12.7 (range two to 31) pre-operatively to 56.2 (range 17–86) postoperatively. It rose from 13.5 to 58.3 in patients with Cuff arthropathy, from 15.8 to 62.0 in revision arthroplasty, from 10.2 to 47.4 in those with fracture sequelae, and from 11.5 to 55.3 in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. The overall mean patient satisfaction score improved from 2.4/10 to 8.5/10 and mean pain score improved from 0.8/15 to 12.5/15. We found an overall improvement in active forward flexion from 46.8 to 128.5° and from 41.6 to 116.5° in abduction. No humeral loosening or subsidence was observed. Two cases of grade 1–2 glenoid notching were reported. Overall there were three intra-operative fractures that did not affect the operation and healed without affecting the good results. There were five late traumatic periprosthetic fractures, only one of them required a revision surgery to a stemmed implant and the rest healed without surgery. There were two early dislocations that had to be revised.

Conclusions

The clinical and radiographic evaluation of a bone preserving metaphyseal humeral component in reverse shoulder arthroplasty is promising, with good clinical results, no signs of loosening or subsidence.

Introduction

Reverse shoulder arthroplasty (RSA) has been gaining popularity in recent years since Paul Grammont [1] introduced the modern RSA design in the 1980s, consisting of a hemispherical glenoid component that generates a medialized and inferior glenohumeral center of rotation which reduces the torque on the glenoid component, increases the moment arm and tensions the deltoid [2, 3]. Currently RSA is indicated for a wide variety of shoulder pathologies such as cuff tear arthropathy, irreparable rotator cuff tear, proximal humeral fracture, fracture sequela, revision of a failed arthroplasty, etc.

Despite promising clinical results with the modern reverse design, significant complication and reoperation rates have been reported [3–8]. A significant part of the reported intraoperative, postoperative and difficulty during revision surgery is related to the diaphyseal humeral component [9–13].

We report on the short-term clinical and radiographic results of patients that underwent RSA with a metaphyseal stem humeral component. Our hypothesis was that the short-stem prosthesis would avoid the complications that are related to the diaphyseal stemmed design without compromising on the clinical and radiographic results.

Patients and methods

We treated 34 consecutive patients with a metaphyseal short stem, reverse shoulder prosthesis (Verso, Biomet, Swindon UK) between 2005 and 2007. Of the 34 patients, 31 were available for analysis at a minimum of 24 months. Two patients were lost to follow-up due to unrelated medical and social reasons, and one died six months after surgery from unrelated cancer. There were 21 females and ten males; the average age at surgery was 73.5 years (58–93) with a mean follow up of 36 months (24–52). The indications for surgery were cuff tear arthropathy (22), fracture sequelae (five) and rheumatoid arthritis (four).

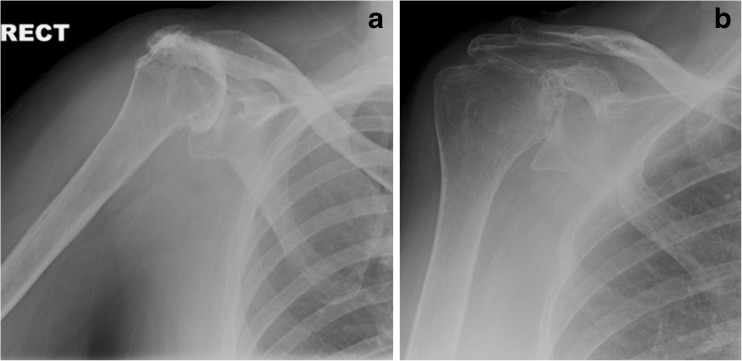

The procedure was performed through the Naviaser-MacKenzie, antero-superior approach to the shoulder [14, 15]. Only minimal proximal humeral bone resection was performed and the resected bone was used for bone graft impaction. The humeral component has three thin fins that give immediate metaphyseal press fit fixation of the humeral prosthesis to the humerus (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Pre-operative X-rays of two patients with cuff arthropathy (a) and rheumatoid arthritis (b)

Patient evaluation was performed by independent observers pre-operatively and at three, six, nine, 12 and 24 months post-operatively and yearly thereafter. Shoulder functionality was assessed using the Constant score. Patient satisfaction and pain relief were assessed on a 0–10 and a 0–15 visual analogue scale accordingly. Radiographic analysis was performed utilising a true AP and axillary views of the shoulder.

Improvement, or gain, in both functionality and patient satisfaction were calculated for each case by comparing the latest observed post-operative value to the corresponding pre-operative value, and the significance of the difference was tested using the paired t-test. Improvement over time (pre-op, immediate post-op, last follow up) in Constant score was assessed using all clinical data. Statistical analyses were carried out using SAS (Release 8.2, SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Results

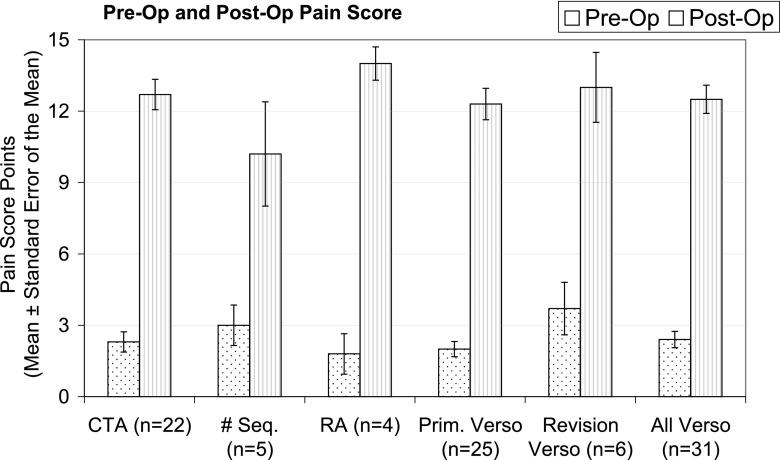

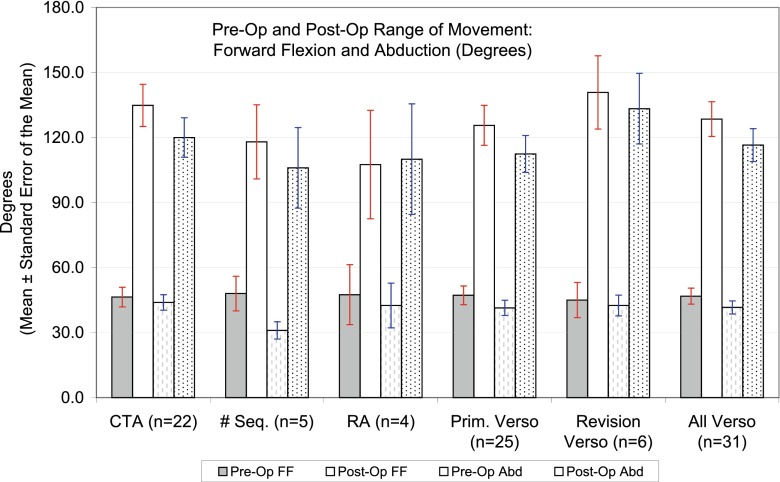

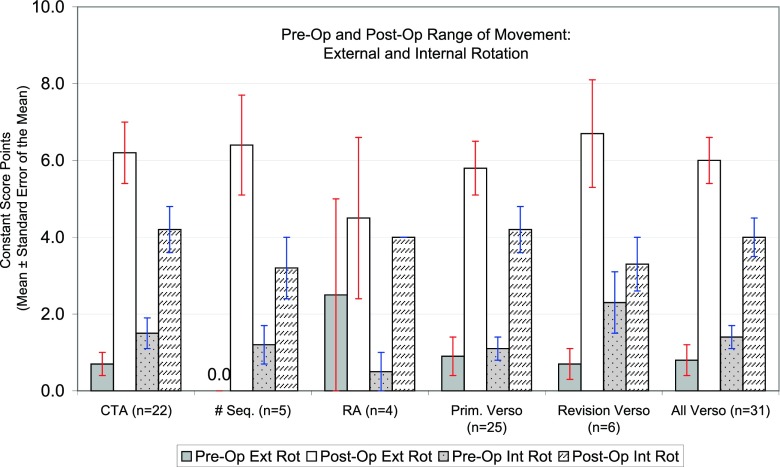

The average Constant score improved from 12.7 (2–31) to 56.2 (17–86). Age/sex adjusted CS improved from 17.8 to 80.2; it rose from 13.5 to 58.3 in patients with Cuff arthropathy, from 15.8 to 62.0 in revision arthroplasty, from 10.2 to 47.4 in those with fracture sequelae, and from 11.5 to 55.3 in patients with rheumatoid arthritis (Fig. 2). All these gains were statistically significant (P < 0.0001). The overall mean patient satisfaction score improved from 2.4/10 to 8.5/10 (Fig. 3), and mean pain score improved from 0.8 to 12.5/15 (Fig. 4). We also found an overall improvement in active forward flexion from 46.8 to 128.5° and abduction from 41.6 to 116.5° (Fig. 5). A mean of 50.8° external rotation and 64.6° internal rotation were documented in the last follow up (Fig. 6).

Fig. 2.

Changes in constant score for various indications

Fig. 3.

Changes in patient satisfaction for various indications

Fig. 4.

Changes in pain score for various indications

Fig. 5.

Changes in forward flexion and abduction for various indications

Fig. 6.

Changes in external and internal rotation score for various indications

The radiographic analysis showed no lucencies around the implants or subsidence (Fig. 7). There were two cases of glenoid notching (grade 1–2) that did not seem to affect the outcome. There were two early dislocations early in the series. Both were re-operated; in the first case the linear was re-oriented and in the second an inferior glenoid osteophyte was resected. Both did well and did not re-dislocate.

Fig. 7.

X-rays of the metaphyseal reverse prosthesis

Two cases had an intra-operative crack of the humeral metaphysis during bone graft impaction, and in one case (3.2 %) the glenoid rim was cracked during preparation. All these healed completely around the implants at three months with conservative treatment. These were part of the learning curve of the new implant.

One patient developed stress fracture of acromion three months after surgery. The patient had a temporary episode of pain and limitation of movement, however, regained full range of motion and function with no pain without any treatment.

Five patients (16 %) that were doing very well after the arthroplasty, unfortunately, sustained late traumatic periprosthetic fractures after falls. One sustained glenoid fracture following a fall, and the patient refused further surgery. Three sustained metaphyseal fractures following a fall. They were treated conservatively and all healed with good function (Fig. 8). One patient sustained a fully displaced proximal metaphyseal fracture and had revision to a stem reverse prosthesis.

Fig. 8.

a–f X-rays of an acute late traumatic periprosthetic fracture (a) after a couple of falls of the patient, the healing of the periprosthetic fractures (b, c), and the final clinical results (d–f)

Overall, only three patients had to undergo revision surgery, two for instability and one for the late traumatic fully displaced periprosthetic fracture for revision to stemmed prosthesis.

Discussion

The preliminary short-term clinical and radiographic results with metaphyseal short stem reversed shoulder prosthesis are promising. The average Constant score improved by 43.5 points from 12.7 to 56.2. The improvement was statistically significant (p < 0.0001) for all subgroups of the Constant score: pain, activity of daily living, range of motion and power. In addition, we found a marked improvement in patient satisfaction of their shoulders from 2.4 to 8.5/10.

In their systemic review of the complications related to reverse shoulder arthroplasty, Zumstein et al. [9] found a 4.2 % prevalence of complications related to the humeral component, representing 20 % of all postoperative complications including periprosthetic fracture, disassembly, and loosening. In revision cases they found that the humeral component had to be removed in more than 70 % of the cases.

Matsen warned of the potential for an increase in the risk of fracture and loosening with reverse-geometry designs, stating that, because the prosthesis is a fixed-fulcrum device, “forces applied to the humerus . . . may cause humeral or scapular fracture and prosthesis failure by fatigue” [16].

The periprosthetic fractures problem is even greater with reverse shoulder replacement; most of them required reoperation for the fracture.

In a recent paper by Anderson et al. [13], there were 36 periprosthetic fractures treated surgically by either ORIF or revision arthroplasty. They concluded that: “Periprosthetic fracture around a humeral stem implant is a difficult clinical problem involving complex decision-making.... Complications were frequent, and a reoperation was required in 19 % of the patients. More than half of the patients in our study had a loose humeral component that required revision.”

Boileau et al. [3] claimed that fixation of a reversed prosthesis may be more problematic on the humeral side than on the glenoid side. Some of the potential reasons for these complications such as humeral subsidence, unscrewing or loosening may be related to the fact that the humeral stem is round and offers very little resistance to rotational torque. We did not observe any lucent lines, loosening or subsidence of the metaphyseal stem reversed humeral component. A possible explanation is the triple tapered humeral component design that provides a good immediate press fit metaphyseal fixation with resistance to rotational torque.

Melis et al. [17] found radiological signs of stress shielding in 5.9 % of cemented and 47 % in uncemented implants, as well as partial or complete resorption of the greater and lesser tuberosities (greater tuberosity resorption in 69 % of cemented and 100 % in uncemented implants and lesser tuberosity resorption in 45 % of cemented and 76 % of uncemented implants). The fixation of the prosthesis used in our series is metaphyseal rather than in the diaphysis as with diaphyseal stem prostheses. We haven’t seen any lucencies around the humeral component, nor resorption of bone around the humeral component, suggestive of stress shielding in our short term.

Fractures of the proximal humerus due to falls in older age are well known. Proximal humerus fractures account for nearly 5 % of all fractures [18] and incidence increases secondary to an aging population and associated osteoporosis [19–21]. Nearly three fourths of all proximal humerus fractures occur in patients older than 60 years, and they generally occur as a result of low-energy trauma such as a fall from standing height [22]. The risk of late periprosthetic fractures is higher due to the presence of the metal implant as stress riser [13, 23, 24]. While late traumatic (after a fall) periprosthetic humeral fracture in diaphyseal stem prostheses has to be revised in the majority of the cases and has a negative effect on the results [9, 13], in our series most of these fractures were metaphyseal and were treated conservatively with excellent outcome.

The mean age of our patients was 73.5 years (range 58–93 years), and people in this age group are prone to falls and fractures [18–22]. The late traumatic periprosthetic fractures are not complications of the prosthesis. Furthermore, the patients that suffered the late traumatic periprosthetic fractures were not regarded as failures, as they recovered reasonably good function and no pain after healing of the fracture with conservative treatment. Only one patient had to undergo further surgery for periprosthetic fracture. The reason for that difference might be that if a diaphyseal stem prosthesis is used, the periprosthetic fractures tends to occur at the humeral shaft where the metal–bone interface stress riser exists, while in the metaphyseal prosthesis the stress riser is in the metaphysis that has a better potential to heal.

The risk of periprosthetic fractures due to falls exists with any type of prosthesis. We think that with a short metaphyseal stem prosthesis the stress riser remains in the metaphysis and the fracture will be metapyseal and therefore applicable for conservative treatment.

Conclusions

The metaphyseal short-stem reverse shoulder replacement shows encouraging preliminary clinical and radiological results. No humeral component fixation related complications were encountered. We had a low rate of complications and the most frequent complication, late traumatic periprosthetic fractures, were mainly metaphyseal and treated conservatively without compromising the final outcome. Nevertheless, our study is not without limits, this is a short-term (24–52 months) follow-up study on a rather small and heterogenic group of patients. Studies are needed to assess longer follow up.

References

- 1.Grammont TP, Laffay J, Deries X. Concept study and realization of a new total shoulder prosthesis. Rhumatologie. 1987;39:407–418. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Terrier A, Reist A, Merlini F, Farron A. Simulated joint and muscle forces in reversed and anatomic shoulder prostheses. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2008;90:751–756. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.90B6.19708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boileau P, Watkinson DJ, Hatzidakis AM, Balg F. Grammont reverse prosthesis: design, rationale, and biomechanics. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2005;14:147S–161S. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2004.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Farshad M, Gerber C. Reverse total shoulder arthroplasty-from the most to the least common complication. Int Orthop. 2010;34:1075–1082. doi: 10.1007/s00264-010-1125-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Werner CM, Steinmann PA, Gilbart M, Gerber C. Treatment of painful pseudoparesis due to irreparable rotator cuff dysfunction with the Delta III reverse-ball-and-socket total shoulder prosthesis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87:1476–1486. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.D.02342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sirveaux F, Favard L, Oudet D, Huquet D, Walch G, Mole D. Grammont inverted total shoulder arthroplasty in the treatment of glenohumeral osteoarthritis with massive rupture of the cuff. Results of a multicentre study of 80 shoulders. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2004;86:388–395. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.86B3.14024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Levy JC, Virani N, Pupello D, Frankle M. Use of the reverse shoulder prosthesis for the treatment of failed hemiarthroplasty in patients with glenohumeral arthritis and rotator cuff deficiency. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2007;89:189–195. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.89B2.18161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stechel A, Fuhrmann U, Irlenbusch L, Rott O, Irlenbusch U. Reversed shoulder arthroplasty in cuff tear arthritis, fracture sequelae, and revision arthroplasty. Acta Orthop. 2010;81:367–372. doi: 10.3109/17453674.2010.487242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zumstein MA, Pinedo M, Old J, Boileau P. Problems, complications, reoperations, and revisions in reverse total shoulder arthroplasty: a systematic review. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2011;20:146–157. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2010.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Levy O, Copeland SA. Cementless surface replacement arthroplasty (Copeland CSRA) for osteoarthritis of the shoulder. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2004;13:266–271. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2004.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wirth MA, Rockwood CA., Jr Complications of total shoulder-replacement arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1996;78:603–616. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199604000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wall B, Nove-Josserand L, O’Connor DP, Edwards TB, Walch G. Reverse total shoulder arthroplasty: a review of results according to etiology. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89:1476–1485. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.F.00666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Andersen JR, Williams CD, Cain R, Mighell M, Frankle M. Surgically treated humeral shaft fractures following shoulder arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013;95:9–18. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.K.00863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Levy O, Copeland SA. Cementless surface replacement arthroplasty of the shoulder. 5- to 10-year results with the Copeland mark-2 prosthesis. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2001;83:213–221. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.83B2.11238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mackenzie D. The antero-superior exposure of a total shoulder replacement. Orthop Traumatol. 1993;2:71–77. doi: 10.1007/BF02620461. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Matsen F. Commentary and perspective on “The reverse shoulder prosthesis for glenohumeral arthritis associated with severe rotator cuff deficiency. A minimum two-year follow-up study of sixty patients”. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87:1697. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.D.02813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Melis B, DeFranco M, Ladermann A, Mole D, Favard L, Nerot C, Maynou C, Walch G. An evaluation of the radiological changes around the Grammont reverse geometry shoulder arthroplasty after eight to 12 years. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2011;93:1240–1246. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.93B9.25926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bohsali KI, Wirth MA. Fractures of the Proximal Humerus. In: Rockwood CA, Matsen FA III, Wirth MA, Lippitt SB, editors. The shoulder. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kannus P, Palvanen M, Niemi S, Parkkari J, Jarvinen M, Vuori I. Osteoporotic fractures of the proximal humerus in elderly Finnish persons: sharp increase in 1970–1998 and alarming projections for the new millennium. Acta Orthop Scand. 2000;71:465–470. doi: 10.1080/000164700317381144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Palvanen M, Kannus P, Parkkari J, Pitkajarvi T, Pasanen M, Vuori I, Jarvinen M. The injury mechanisms of osteoporotic upper extremity fractures among older adults: a controlled study of 287 consecutive patients and their 108 controls. Osteoporos Int. 2000;11:822–831. doi: 10.1007/s001980070040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Court-Brown CM, Caesar B. Epidemiology of adult fractures: A review. Injury. 2006;37:691–697. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2006.04.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Court-Brown CM, Garg A, McQueen MM. The epidemiology of proximal humeral fractures. Acta Orthop Scand. 2001;72:365–371. doi: 10.1080/000164701753542023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bohsali KI, Wirth MA, Rockwood CA., Jr Complications of total shoulder arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88:2279–2292. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.F.00125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cameron B, Iannotti JP. Periprosthetic fractures of the humerus and scapula: management and prevention. Orthop Clin North Am. 1999;30:305–318. doi: 10.1016/S0030-5898(05)70085-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]